GPT Group: Australia's First Property Trust—From Lendlease Spin-off to $34 Billion REIT Empire

I. Introduction & Episode Roadmap

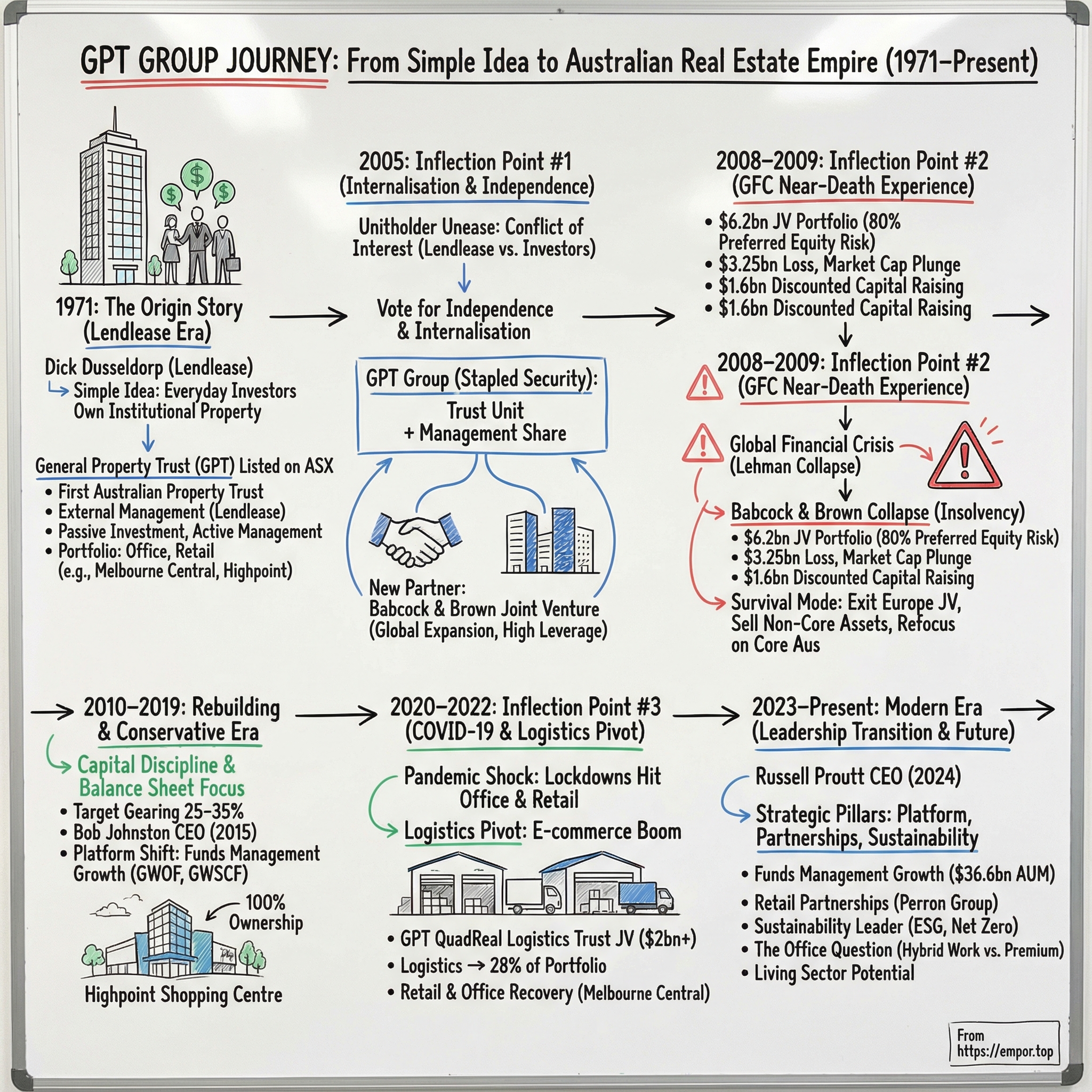

Picture Melbourne, April 1971. The Vietnam War dominates the headlines, decimal currency is still new in Australian pockets, and the Sydney Opera House is still a construction site. Into that moment, a Dutch immigrant’s construction empire—Lendlease—launches something Australia hasn’t seen before: a way for everyday people to buy into big-city commercial property through the sharemarket.

When The General Property Trust listed on the Australian Securities Exchange in 1971, it became Australia’s first property trust. This wasn’t just a new product with a clever wrapper. It was the start of a new asset class in Australian finance. For the first time, “mum and dad” investors could own an interest in a professionally managed portfolio of investment-grade office and retail property—assets that would otherwise be locked behind institutional gates.

Fast forward more than five decades and that simple idea has grown up into The GPT Group: a major real estate investment manager and diversified property owner. By 2025, GPT managed $36.6 billion across retail, office, logistics, and student accommodation—an institutional platform built on the same core promise: steady, tangible assets, packaged for public investors.

But GPT’s story isn’t a straight line of compounding success. It’s a survival story. It includes the Global Financial Crisis, when a joint venture with Babcock & Brown—then one of Australia’s most aggressive dealmakers—became a threat to GPT’s stability as Babcock & Brown collapsed. It includes COVID-19, which didn’t just dent earnings; it rewired assumptions about how Australians shop, how they work, and how goods move through cities. And it brings us right up to the present, where GPT is repositioning for a world that wants more warehouses and fewer five-days-a-week desks.

Today, GPT owns, manages, and develops a portfolio concentrated in Sydney and Melbourne, spanning retail, office, and logistics. Retail and office—helped along by GPT’s funds management contributions—each generate roughly two fifths of the group’s funds from operations, while logistics has become the strategic counterweight as demand shifts.

So this is the story we’re telling: how a passive investment vehicle created by a construction company became one of Australia’s most influential real estate groups—and how it survived a near-death experience to keep evolving. Along the way, we’ll hit the big themes: first-mover advantage, the hidden conflicts of external management, the asymmetric danger of leverage, and the question now hanging over every premium CBD tower—what happens when the old rhythm of office life doesn’t fully come back?

II. The Lendlease Innovation: Creating a New Asset Class (1971)

To understand how Australia’s first property trust came to be, you have to start with the person who built the machine that created it: Dick Dusseldorp.

Gerardus Jozef Dusseldorp AO was born in Utrecht in December 1918. As a child he was known as “Dik”—an anglicised nickname that followed him for life. He trained as a water engineer, but his early adulthood was shaped less by engineering than by survival. During World War II, he was deported to Berlin as forced labour. After returning to the Netherlands, he found work with a Danish firm building a railway between Copenhagen and Hamburg, only to be transported again in late 1943—this time to Kraków, as forced labour for the Siemens Organisation.

In 1951, after the war, Dusseldorp emigrated to Australia. Over the next decade he built the foundations of what became one of the country’s most important property and construction groups. He founded Civil & Civic, then in 1958 established Lendlease Corporation to finance building contracts being undertaken by Civil & Civic. In 1961, Lendlease acquired Civil & Civic from Bredero’s Bouwbedrijf. It was an integrated setup: finance, construction, and development connected inside one ecosystem.

That integration is what made GPT possible.

In April 1971, Lendlease launched The General Property Trust—Australia’s first property trust—then managed it on behalf of public investors. The pitch was simple and radical for its time: ordinary sharemarket investors could buy into a professionally managed portfolio of high-quality commercial property. Until then, owning slices of Sydney office towers or Melbourne retail precincts was mostly the domain of institutions and wealthy families. GPT turned that world inside out.

For Lendlease, the trust structure wasn’t just a gift to retail investors. It was also a new way to fund growth without leaning too hard on debt. Public equity could be raised into a vehicle that owned buildings and paid distributions, while Lendlease sat in the manager’s chair—sourcing assets, developing, and running them.

Dusseldorp’s edge was what he called “undivided responsibility”: the idea that financing and delivery shouldn’t be separated. If you could build the building, arrange the capital, and then have a long-term owner ready to hold it, you created a self-reinforcing loop. A listed trust could acquire and hold the assets that the construction and development arm created—tying the outcomes together and, at its best, compounding value through the cycle.

By the time Dusseldorp retired from Lendlease in 1988, that symbiosis between the parent company and the trust had already created enormous value for both shareholders and unitholders.

And the founding principle that launched it all was still the same: a passive investment in a diversified pool of prime commercial assets—liquid, professionally managed, and accessible. For “mum and dad” investors, it was a new doorway into institutional real estate. For Australia’s capital markets, it was the birth of an industry.

III. Three Decades Under Lendlease: The Quiet Growth Years (1971–2005)

For the next three decades, GPT lived inside a structure that was normal for the era, but strange by today’s standards. GPT owned the buildings. But Lendlease—separate from the trust—ran everything.

This was the externally managed model. Investors bought units in the trust and collected distributions. Meanwhile, the manager made the calls: what to buy, what to sell, how hard to gear the portfolio, and when to raise capital. In return, the manager earned fees.

From day one, Lendlease sat in the driver’s seat. GPT was established as a unit trust, with Lendlease acting as Responsible Entity and manager. The unitholders owned the assets, but the power lived with the manager. A long-running management deed locked in how that relationship worked—fees, control, decision rights—and it stayed the backbone of GPT’s governance for decades.

And to Lendlease’s credit, those decades delivered what the trust was designed to do: steadily accumulate high-quality Australian commercial real estate. GPT built out a portfolio anchored in office and retail, then broadened around the edges. In 2001, it even stepped into leisure, buying P&O’s Australian resorts portfolio—an example of the trust looking beyond its traditional lanes while keeping its core intact.

Over time, GPT’s holdings came to read like a guided tour of prime Australian property: major Sydney CBD assets like Darling Park, 2 Park Street, and Australia Square; Melbourne Central and Highpoint Shopping Centre in Melbourne; and One Eagle Street in Brisbane. These were the kinds of assets that didn’t just throw off rent—they shaped precincts and anchored cities.

Melbourne Central, in particular, became a defining GPT property. It wasn’t just a shopping centre or an office tower. It was integrated into the fabric of Melbourne’s CBD, tied directly into public transport and the daily flow of commuters. That mix—retail, office, and infrastructure in one connected hub—was exactly the kind of transit-oriented real estate that would only grow more valuable as cities densified.

Highpoint was a different kind of crown jewel: a super-regional retail destination in Melbourne’s north-west growth corridor. It served an enormous catchment and, year after year, proved why scale and location can make a shopping centre more like a piece of infrastructure than a discretionary asset.

But there was a trade-off embedded in this whole setup. External management works—until the incentives stop lining up.

Because here’s the problem: when the manager gets paid for running the vehicle, the manager is naturally incentivised to grow the vehicle. More assets under management often means more fees, even if the incremental deals aren’t the best risk-adjusted returns for the unitholders. And when the manager is also a major property company with its own pipeline of projects and interests, questions about related-party transactions and who benefits first are never far away.

By the early 2000s, unitholders were no longer willing to treat that as background noise. They started asking the obvious question: were Lendlease’s management fees and strategic decisions truly aligned with long-term unitholder value?

The era of quiet acceptance was ending.

IV. Inflection Point #1: The 2005 Internalisation—Breaking Free from Lendlease

By 2005, the unease that had been building for years finally turned into action. After more than three decades as Lendlease’s managed investment vehicle, GPT’s unitholders voted to take control of their own destiny: internalise management and create an independent GPT.

It didn’t happen on the first try.

In 2004, GPT security holders rejected Lend Lease’s internalisation proposal of $3.56 per unit—helped along by Westfield voting against the scheme. At the time, Lyons said the “commercial terms [did] not adequately compensate GPT’s investors.” It was a public signal that unitholders were no longer willing to accept a structure where the biggest decisions were made by an external manager whose incentives didn’t always match theirs.

That “no” forced a reset. In 2005, investors approved a stapling proposal that removed Lend Lease as manager of the Trust and replaced it with a new management company that was stapled to the Trust. And crucially, this wasn’t some accounting-driven move. The purpose wasn’t tax. It was alignment—creating an independent property group where the people running the business were directly tied to the same value creation as the people funding it.

That vote is the moment GPT, as we know it today, was born. It separated from Lendlease and evolved into the independent stapled entity called The GPT Group—an internalisation that gave it its own strategic direction and real operational autonomy.

To understand why this mattered, you have to understand the “stapled security” structure—one of those very Australian capital markets inventions. A stapled security combines a unit in a Trust and a share in a Company, linked so they can’t be traded separately. On the ASX they quote together as one security. For GPT investors, that meant holding one General Property Trust unit and one GPT Management Holdings Limited share, stapled together and traded under the ticker “GPT”.

Independence, though, came with a twist that would shape the next chapter—and nearly break the company.

Because GPT didn’t just internalise and walk off into the sunset. In the same period, it linked up with Babcock & Brown.

At the time, the partnership looked like perfect timing. Babcock & Brown was one of Australia’s most aggressive investment banks in the pre-GFC property boom—famous for structured deals and financial engineering. For a newly independent GPT, the pitch was compelling: plug into Babcock & Brown’s deal-making machine and use it as a launchpad for international growth.

The joint venture took shape quickly. In mid-2005, BGP Investment was established as the European holding vehicle for the major joint venture between Babcock & Brown and GPT, with BGP Holdings as the ultimate parent. Ownership was 50:50. By 2007, the fund’s total committed equity capital of $2.2 billion had been fully invested.

And it wasn’t timid. The joint venture invested across Europe, North America, and Australasia—spanning Australia, New Zealand, and the UK, across to the Czech Republic, Denmark, France, Germany, Lithuania, the Netherlands, Poland, Spain, Sweden, and into North America. By 31 December 2007, it had contracted and completed European investments with a carrying value of €3.2 billion. By 2007, the portfolio had grown to nearly €4 billion in gross assets, before deteriorating global conditions forced a partial sell-down.

In the moment, it looked like a breakout move: GPT, newly free from Lendlease, going global with an elite partner.

In hindsight, it was the setup for a near-death experience. The joint venture’s structure—where GPT provided the majority of capital as preferred equity—embedded an asymmetry that wouldn’t be fully understood until the cycle turned. Within three years, that risk would stop being theoretical and become brutally real.

V. Inflection Point #2: Near-Death Experience in the GFC (2008–2009)

The Global Financial Crisis didn’t just shake GPT. It put the whole institution on the edge.

What started as a downturn in the US housing market spread fast—through banks, funding markets, and investment vehicles that were all more interconnected than anyone wanted to admit. And when Lehman Brothers failed in September 2008, the panic went global. Credit tightened, lenders disappeared, and investors stopped asking “what’s the return?” and started asking “will you be here next month?”

For GPT, the timing couldn’t have been worse, because its chosen partner for global expansion—Babcock & Brown—was built on a model that needed constant refinancing. It financed long-term real assets with short-term borrowing, then rolled that borrowing again and again. When interbank lending seized up and capital markets froze, that machine simply couldn’t keep running.

Confidence collapsed with it. Babcock & Brown’s share price fell from a mid-2007 peak of A$35 to A$2.70. In March 2009, the firm went into voluntary administration after unsecured bondholders rejected a debt restructuring plan that would have valued their claims at 0.1 cents in the dollar. Without that deal, Babcock & Brown LP couldn’t meet interest payments. It was insolvent.

And suddenly, GPT wasn’t just watching a partner fail. It was staring down the blast radius.

The joint venture between GPT and Babcock & Brown had a portfolio of assets valued at $6.2 billion. GPT’s investment included $1.2 billion of preferred capital—effectively a preferred loan that made up about 80% of the JV’s financing. As European real estate valuations fell and the JV’s gearing bit harder, investors realised GPT had far more at stake than a simple 50:50 partnership headline suggested.

The market’s verdict was brutal. In October 2008, CEO David Lyons resigned after GPT was forced into a deeply discounted $1.6 billion capital raising. The pain kept coming. GPT later reported a $3.25 billion loss for the year, driven largely by write-downs on the European joint venture. Its market capitalisation shrank to about $1.56 billion—down from more than $9 billion in April 2007.

In under two years, more than 80% of GPT’s market value was wiped out. For Australia’s oldest property trust, it raised the unthinkable question: could it actually fail?

By mid-2009, the strategy snapped back to survival mode. Under pressure from analysts and shareholders, GPT moved to exit its European exposure and refocus on its core geographies and sectors. That meant unwinding more than assets—it meant dismantling the platform built to manage them. GPT sold its European asset management business, GPT Halverton, to Internos Real Investors in December 2009.

And on 31 July 2009, GPT took the decisive step: it announced its exit from the European component of the joint venture by distributing shares in BGP Holdings to GPT securityholders as a dividend in specie. Europe represented about 80% of the JV, so this move effectively removed the bulk of the JV from GPT.

The company’s 2009 Annual Report reads like a triage checklist—less about growth, more about keeping the patient alive. It pointed to a strengthened balance sheet, covenant risk removed, near-term financing risk reduced, a better credit rating, a renewed board and senior management team, an exit from the Babcock & Brown JV, a refined strategy, $1.1 billion of announced non-core asset sales, revised capital management policies, and operating earnings guidance exceeded.

But the cost showed up everywhere else. Distributions fell sharply from the prior year’s 17.7 cents per security. Net Tangible Assets per security dropped to $0.69 from $1.43 at December 2008—hit by broad valuation falls, and diluted further by the flood of new securities issued in the capital raising.

In 2010, GPT consolidated its stapled securities, effectively merging every five stapled securities into one. It didn’t change anyone’s economic interest in the group, but it reflected a company rebuilding its capital base after being forced to massively expand the register just to survive.

This was the moment the pre-GFC playbook died inside GPT. Aggressive leverage and international expansion had looked like sophistication in the boom. In the bust, they revealed themselves as existential risk. And the joint venture structure that was supposed to boost returns didn’t just disappoint—it magnified the downside when the cycle turned.

VI. The Rebuilding Years: Conservative Capital Management (2010–2019)

The decade after the GFC was where GPT rebuilt its reputation—and, more importantly, rewired its instincts. The lesson it took from the Babcock & Brown era wasn’t “never take risk.” It was that in real estate, the wrong kind of risk can kill you. So under new leadership, GPT made capital discipline its defining feature, not a footnote.

On paper, some analysts would later describe GPT’s strategy as “not particularly differentiated” from peers—except for two things: relatively conservative gearing, and a modest emphasis on development. But what sounds like faint praise was actually the point. After watching leverage turn a market downturn into a near-existential crisis, GPT decided its edge would be staying inside its comfort zone on debt and avoiding the temptation to swing for growth at any cost.

A strong balance sheet became the centrepiece. GPT focused on keeping gearing within its target range of 25–35%—enough debt to be efficient, but not so much that a valuation shock or refinancing crunch could force a fire sale. The industry had learned the same lesson the hard way: during the GFC, high leverage didn’t just amplify losses, it fuelled bad acquisitions and propped up distributions that weren’t sustainable. In the years that followed, that urge to load up on cheap debt mostly stayed in check.

At the same time, GPT leaned harder into something that looked a lot more like a modern platform business: funds management. Instead of being only a landlord collecting rent, GPT expanded its role as a manager of capital for institutions. The GPT Wholesale Office Fund (GWOF) and GPT Wholesale Shopping Centre Fund (GWSCF) gave big investors—especially Australian superannuation funds—a way to co-invest in prime property alongside GPT, while GPT earned recurring fees for managing the assets.

GWSCF, for example, was established in March 2007 with a portfolio of interests in eight retail assets in New South Wales and Victoria. By 30 June 2025, it held ownership interests in five high-quality retail assets valued at $3.4 billion. It’s an open-ended fund with 30 investors—around 80% large Australian super funds, with the remainder global institutions—and it returned 13.5% in the 12 months to 30 June.

Then, in September 2015, Bob Johnston took over as CEO. He arrived with deep industry mileage: CEO of Frasers Property Australia from 2014 to 2015, and before that senior roles at Lendlease. Stockland would later point to his more than 30 years across investment, development, project management, and construction in Australia and overseas—exactly the kind of operator you want after a decade spent prioritising stability and execution.

Under Johnston, GPT also doubled down on its crown jewels. One of Australia’s largest wholesale real estate funds managed by GPT acquired a 25% stake in Highpoint Shopping Centre for AUD 680 million—a move that ultimately took GPT to 100% ownership of the centre in Melbourne’s inner-west suburb of Maribyrnong.

And Highpoint wasn’t just another mall. It’s one of the country’s leading super-regional shopping centres—often counted among the top tier—with around 470 stores, including Myer and David Jones, plus major international names like Apple, Zara, and Samsung. It’s the kind of asset that, in GPT’s post-GFC worldview, is worth paying up for: dominant, hard to replicate, and resilient through cycles.

VII. Inflection Point #3: COVID-19 and the Logistics Pivot (2020–2022)

COVID-19 forced GPT to confront the kind of question real estate owners hate most: what if the old world doesn’t come back?

Lockdowns didn’t just dent earnings. They attacked the basic assumptions under two of GPT’s biggest pillars. Shopping centres went quiet. Office towers emptied out. And suddenly, “prime” didn’t feel quite as permanent as it used to.

In 2020, GPT reported a net loss after tax of $213.1 million, compared to $880 million the year before, as the pandemic hit valuations across the portfolio. Moody’s vice president Saranga Ranasinghe called the result credit negative, pointing to a sharp decline in retail asset values and a smaller, but still meaningful, valuation hit in office.

But inside the crisis, GPT also saw the clearest signal it had been given in years about where demand was going next.

While people stopped commuting and wandered malls less often, they ordered everything. E-commerce didn’t just rise; it became infrastructure. Goods still had to move, be stored, picked, packed, and delivered—fast. And that pulled the spotlight onto logistics: warehouses, last-mile distribution, and the kind of industrial real estate that suddenly looked like the most essential property in the country.

GPT leaned into that shift.

In February 2021, GPT announced a strategic partnership with Canada’s QuadReal Property Group, creating the GPT QuadReal Logistics Trust. It was a 50:50 joint venture aimed at acquiring and developing a portfolio of prime Australian logistics assets, with an initial targeted investment of $800 million.

Bob Johnston, GPT’s Managing Director and CEO, framed the move plainly: growth in logistics was now a core focus, supported by structural tailwinds like e-commerce, along with distribution demand across categories like food and pharmaceuticals.

And the strategy wasn’t a leap into the unknown. GPT had already been building the exposure. Matthew Faddy, GPT’s Head of Office and Logistics, noted that the value of GPT’s logistics portfolio had doubled since 2017 to $3.0 billion, driven by developments and targeted acquisitions. That doubling reflected a longer-term plan to lift logistics to at least 20% of the total portfolio—because even before COVID, GPT could see where the cycle was heading.

The QuadReal partnership quickly scaled. The two groups later doubled the size of their logistics joint venture to A$2 billion. And the expansion continued again with a second vehicle, GPT QuadReal Logistics Trust 2, seeded with about $460 million of stabilised east coast logistics assets in urban infill and middle-ring locations, with a further $500 million targeted for deployment.

By the most recent update in this period, logistics had risen to around 28% of GPT’s portfolio. Retail and office, roughly evenly split, made up most of what remained.

What’s striking is that this wasn’t a story of running away from retail. It was more like rebalancing the engine mid-flight.

Because retail, once restrictions eased, came back faster than many expected. For the six months to 30 June 2021, total centre sales were up 5.0%, and total specialties sales were up 6.5%, compared to the same period in 2019. When the doors reopened, consumers returned—helped by stronger economic conditions.

And at the flagship level, Melbourne Central delivered a symbolic win: it regained its number one position after the pandemic’s heavy blow to CBD retail. Even with office workers not fully back in the city, GPT pointed to an “exceptional” recovery—and a clear sign that shoppers still valued a vibrant city centre.

Offices would remain the harder question. But in 2020–2022, GPT made its bet: keep the crown jewels, ride the recovery where it shows up, and build the logistics platform that the new economy can’t function without.

VIII. The Modern Era: Leadership Transition and Strategic Positioning (2023–Present)

By 2023, GPT had done something hard: it had steered through the pandemic shock, rebalanced toward logistics without abandoning its flagship retail assets, and rebuilt momentum. Then it faced the next inevitable test for any long-lived institution: succession.

In September 2023, GPT announced that CEO Bob Johnston would retire, setting up a transition to Russell Proutt. Proutt officially took the top job in March 2024, stepping in as Chief Executive Officer and Managing Director.

On paper, it was a classic “safe hands” appointment—but with the kind of resume that matters in real estate, where cycles and capital markets can change the story overnight. Proutt brought more than 30 years of global leadership experience across commercial property, funds management, M&A, and finance. Most recently, he’d been CFO at Charter Hall since 2017. Before that, he spent 12 years at Brookfield Asset Management as a Managing Partner, based first in Canada and later in Australia, working across property and infrastructure throughout the Asia region. Earlier still, he spent 15 years in investment banking and financial services in North America.

In other words: a leader built for a world where owning buildings is only half the job, and managing capital—through funds, partnerships, and development pipelines—is the other half.

GPT’s own message on Johnston’s tenure was clear. He’d led the group through a period of significant growth and reshaped its strategy, structure, and portfolio mix in ways that positioned GPT for the next phase. That next phase, under Proutt, has kept leaning into the platform: sharpening the portfolio, building partnerships, and recycling capital into projects where GPT believes it can add value.

On the retail side, GPT continued expanding its footprint and management platform. It established a retail partnership with the Perron Group and acquired a 50% interest in Cockburn Gateway and Belmont Forum in Perth for approximately $482 million—adding scale in Western Australia and reinforcing that GPT’s post-COVID strategy wasn’t “retail is dead,” but “retail has to be dominant and well-located to win.”

At the same time, GPT kept pushing value-accretive development where it already had advantages, including a $200 million redevelopment of Rouse Hill Town Centre.

Operationally, the business carried that momentum into 2025. In the first half of 2025, GPT reported funds from operations growth of 4.4%. Assets under management rose by $2.2 billion to $36.6 billion. Like-for-like net property income grew across both major legacy pillars—5.6% in Retail and 6.5% in Office—while the investment portfolio delivered headline growth of 4.2%. Occupancy sat at 98.5% across the investment portfolio, a signal of both demand and disciplined asset management.

And then there’s the part of the story GPT wants to be known for globally: sustainability.

GPT has positioned itself as a long-term leader rather than a late adopter. It’s listed in the Dow Jones Sustainability World Index, and has ranked in the top 5% of real estate companies in S&P Global’s Corporate Sustainability Assessment since 2009. In the GRESB Real Estate Benchmark, GPT and each of its wholesale funds have been recognised in the top quintile every year since the benchmark began in 2011—including Green Star (top quintile) status for ten consecutive years. It has also been a signatory to the United Nations Global Compact since 2012.

GPT has more carbon neutral building certified floor space than any other Australian property owner, and it has been ranked first out of 864 real estate companies in the S&P Global Corporate Sustainability Assessment—another way of saying: in a sector where capital is increasingly values-driven, GPT has made ESG a core part of its identity, not a marketing overlay.

The modern GPT, then, is the product of everything that came before: the first-mover trust structure, the hard lessons of leverage, the platform shift into funds management, and the COVID-era logistics pivot. Under new leadership, the strategy now is less about dramatic reinvention—and more about compounding: selectively expanding, developing where it can win, and keeping the balance sheet and the brand strong enough to ride whatever the next cycle brings.

IX. Playbook: Business Lessons & Strategic Framework

GPT’s 54-year journey isn’t just a chronology of deals and buildings. It’s a case study in how a real estate business survives multiple eras, learns the hard lessons, and keeps compounding anyway. Here’s the playbook it wrote along the way.

First-Mover Advantage in New Asset Classes: Being Australia’s first property trust didn’t just make GPT a novelty in 1971. It gave the group a head start in reputation and relationships that has lasted for more than half a century. The structure Dick Dusseldorp and Lendlease brought to market became the template the rest of the industry followed.

The Internalization Imperative: External management can work, right up until it doesn’t—because the incentives are never perfectly aligned. The 2005 internalisation was GPT choosing alignment over convenience. It was disruptive and expensive in the short term, but it set GPT up to make decisions for unitholders, not for an external manager’s fee stream.

Conservative Capital Structure as Competitive Advantage: The Babcock & Brown chapter left a scar—and in real estate, scars can be strategy. GPT came out of the GFC with a cultural bias toward moderation on debt. Its target gearing range of 25–35% reflects a simple, hard-earned truth: leverage is asymmetric. It can juice returns on the way up, but on the way down it can end the story.

Platform Business Model: Over time GPT evolved from “a trust that owns buildings” into a platform that also manages other people’s capital. By June 2025, GPT managed third-party assets and mandates of AUD 24 billion. That fee income diversifies earnings beyond rent and valuations, and it deepens GPT’s institutional relationships in a sector where access to capital is a weapon.

Adaptability in Crisis: COVID didn’t just test resilience; it forced a rewrite of assumptions. GPT treated the disruption as a portfolio signal, not just a temporary shock—leaning further into logistics as e-commerce and last-mile delivery became essential infrastructure. The companies that win long term in property aren’t the ones that predict every crisis. They’re the ones that rebalance fast when the world changes.

Sustainability as Strategy: GPT’s sustainability positioning isn’t framed as compliance; it’s positioned as competitive advantage. Consistent recognition among the world’s most sustainable real estate companies helps attract ESG-focused capital, appeals to premium tenants, and supports long-term asset values. In a capital-intensive industry, that can translate into a lower cost of capital, stronger tenant demand, and more durable assets through the cycle.

X. Porter's Five Forces Analysis

Threat of New Entrants: LOW-MODERATE

In prime commercial property, the first barrier is simple: you need an enormous amount of capital just to get a seat at the table. The second barrier is harder to see, but just as real: relationships. GPT has spent decades building ties with institutional investors and blue-chip tenants, and those networks don’t materialise overnight.

And then there’s the ultimate constraint. The best locations are already owned. Nobody is making more Sydney CBD waterfront land.

Still, “low” doesn’t mean “none.” Deep-pocketed global pension funds and sovereign wealth funds can—and do—buy their way in, using acquisitions as the fast track into Australian real estate.

Bargaining Power of Suppliers: LOW

For a group like GPT, suppliers are mostly builders, consultants, and sources of capital. On construction, it’s a competitive market: many contractors chase major projects, and much of the work is interchangeable.

On capital, GPT isn’t reliant on a single gatekeeper. Debt and equity come from multiple channels, which keeps pricing disciplined. In that setup, the REIT is typically the buyer with leverage, not the supplier setting the terms.

Bargaining Power of Buyers (Tenants): MODERATE-HIGH

This is where the post-COVID world really shows up.

In offices, tenants have gained bargaining power as vacancy rises and hybrid work reduces the amount of space many companies actually need. Even with more return-to-office pressure, the overall negotiating dynamic has shifted: landlords have to work harder to win, keep, and expand tenants.

Retail is more nuanced. The very best centres remain scarce and highly productive, but tenants now have more alternatives than they used to—especially online—which gives them more confidence at the negotiating table.

And in logistics, the power balance has recently tilted the other way. E-commerce fulfilment and faster delivery expectations have kept demand strong, which tends to give landlords more pricing power—at least for well-located, functional assets.

Threat of Substitutes: MODERATE-HIGH (and Rising)

Office has a substitute now that didn’t exist at scale in 2019: work-from-home. Hybrid work, in particular, is the quiet pressure that can shrink demand without any single dramatic collapse. Return-to-office mandates may pull more people back in person, but the key change is permanent—companies have proved they can operate with less space.

Retail’s substitute is also obvious: e-commerce. The counterpoint is that physical retail still wins when it’s experiential, convenient, and located where people already are.

Logistics is the rare case where the “substitute” trend actually strengthens the category. More online shopping doesn’t reduce the need for warehouses—it increases it.

Industry Rivalry: HIGH

Australian REITs compete in a crowded, sophisticated arena, and GPT’s rivals are serious operators: groups like Dexus, Charter Hall, Mirvac, and Goodman.

The competition isn’t just for tenants—it’s for capital, for acquisition opportunities, and for the right to own the next generation of irreplaceable sites. Dexus is heavily exposed to offices and industrial property, tying its fortunes to how hybrid work ultimately settles. Charter Hall brings massive scale in funds management and a large development pipeline. Goodman is a global logistics heavyweight with a broad international footprint and a huge customer base.

In other words: GPT may have heritage and prime assets, but it’s playing in a league where everyone is well-capitalised, highly capable, and fighting for the same finite set of great properties.

XI. Hamilton's 7 Powers Analysis

Scale Economies: MODERATE

GPT is one of Australia’s largest property groups, managing tens of billions of dollars of assets across the country.

Scale shows up most clearly in the platform, not the bricks. The larger the funds management business gets, the more it can spread fixed costs across a bigger base of assets under management. And at the operating level, property management and leasing teams can run larger portfolios more efficiently than a smaller competitor can.

What scale doesn’t do, at least not in any magical way, is make an individual building intrinsically better just because it sits inside a bigger portfolio.

Network Effects: LOW

Real estate doesn’t work like software. Owning more properties doesn’t automatically make each existing property more valuable.

The closest thing to a network effect is in retail: bigger, better-curated centres can create a flywheel where more tenants attract more customers, which attracts more tenants. But that dynamic is local to each centre. It doesn’t compound across the broader portfolio in the way a true network effect would.

Counter-Positioning: MODERATE

GPT’s post-GFC conservatism is a strategic stance. By keeping gearing relatively restrained and not leaning heavily into high-risk development, GPT positions itself differently from competitors willing to push the cycle harder.

The key here is credibility. A competitor built around leverage and aggressive development can’t suddenly “be conservative” without giving up the very returns its investors expect. Sustainability also adds a second layer of counter-positioning: ESG leadership can help GPT appeal to pools of capital that increasingly have mandates, not just preferences.

Switching Costs: LOW-MODERATE

Switching costs exist, but they’re uneven by sector.

Office tenants face the pain of moving—fit-outs, downtime, and disruption—which creates some stickiness. Retail tenants in truly dominant centres often have fewer good alternatives, especially when location and foot traffic are the difference between thriving and failing. Logistics tenants can be more mobile, but purpose-built warehouses and distribution facilities can still create real friction to relocate.

On the capital side, investors in GPT’s wholesale funds can face lock-up periods and other structural limits that make switching slower and more costly.

Branding: LOW-MODERATE

GPT has history on its side. It began life as The General Property Trust, Australia’s first property trust—an origin story that still carries weight with institutions.

But in practice, the brand matters most where consumers feel it: flagship retail assets like Melbourne Central and Highpoint. In office and logistics, tenants care far more about location, quality, and economics than the logo on the annual report. Even so, being “Australia’s first” remains a credibility signal in a sector built on trust and long-duration capital.

Cornered Resource: MODERATE

In real estate, the ultimate scarce resource is the right site in the right city.

Prime Sydney and Melbourne CBD locations are finite and effectively irreplaceable. Assets like Melbourne Central—where premium office space sits adjacent to a major retail and transport-connected precinct—are the kind of positioning competitors can’t replicate just by writing a cheque and starting from scratch.

That said, this power has limits. Unlike a patented technology, many individual assets can theoretically be bought if the price is high enough, which caps how “cornered” the resource really is.

Process Power: MODERATE

GPT benefits from the quiet compounding of experience: decades of operating, developing, and managing institutional-grade property. That institutional knowledge—plus relationships with premium tenants—helps execution. Its wholesale funds track record also helps attract and retain institutional capital.

But it’s not a secret recipe. GPT’s processes are strong, yet broadly comparable to other top-tier Australian REITs.

Summary: GPT’s strongest powers are Scale Economies in funds management and Cornered Resources in prime CBD locations. It doesn’t have tech-style moats, but that’s normal in real estate—where the edge comes from capital discipline, asset quality, and execution over cycles.

XII. Bear vs. Bull Case

Bull Case:

GPT is ultimately a bet on Australia’s cities continuing to grow—and on well-located real estate staying essential as they do. Population growth has historically translated into more demand for places to work, shop, and, increasingly, store and move goods. And Australia’s immigration-driven population growth has remained among the highest in the developed world, which matters because people growth tends to show up in floor space demand with a lag.

The other structural tailwind is that GPT has been reshaping its mix toward the parts of property that benefit from the digital economy instead of being disrupted by it. Industrial and logistics is now roughly 28% of the portfolio, giving GPT a larger stake in the “back end” of commerce—warehouses, distribution, and last-mile facilities—where demand has been pulled forward by e-commerce and is likely to keep compounding as online retail penetration rises.

Importantly, GPT also has the balance sheet to play offense when others can’t. With net gearing of 28.7%, it has meaningful headroom relative to its 50% covenant. That conservative posture doesn’t just reduce risk; it creates optionality—dry powder for opportunistic acquisitions or development when pricing dislocates.

Then there’s the platform angle. GPT isn’t only earning rent; it’s earning fees. Its funds management business diversifies earnings away from direct property ownership, and as of June 2025 it managed $24 billion of third-party assets and mandates—capital that can scale without GPT necessarily having to load up its own balance sheet.

Layer on top GPT’s sustainability credentials, which can attract ESG-focused capital and tenants, and a CEO in Russell Proutt with deep capital markets and funds management experience from Charter Hall and Brookfield, and you get a plausible bull case: a high-quality Australian portfolio, an expanding logistics tilt, and the financial flexibility to compound through the next cycle.

Bear Case:

The clearest risk is also the most visible: office. GPT’s office portfolio recorded a 16.8% decline in value over the year, driven by weak income fundamentals and a softening of capitalisation rates. And the concern isn’t just cyclical. Hybrid work has created a structural question about how much space companies will truly need over the long run, and that uncertainty can hang over valuations for years.

That would be manageable if office were a small slice. But it’s not. Retail and office—when you include their related funds management contributions—each generate about two fifths of GPT’s funds from operations. With office around 40% of earnings, persistent weakness doesn’t stay contained; it shows up in group-level performance.

Retail, meanwhile, has its own structural challenger: e-commerce. Even dominant centres can’t coast. They require ongoing capital investment—refurbishments, tenant remixing, experiences—to stay relevant as consumers keep shifting more spend online.

There’s also the macro overlay that hits all REITs. These are long-duration assets, which makes them sensitive to interest rates. Rising rates can compress valuations and lift debt costs at the same time—an unpleasant combination if it persists.

Finally, there’s concentration risk. GPT is fundamentally an Australia-focused story. Compared to global peers with broader geographic diversification, GPT’s outcomes are more tightly linked to Australian property markets and Australian economic conditions—great when the cycle is kind, but a real limitation when it isn’t.

XIII. Key Performance Indicators for Ongoing Monitoring

If you want a clean, ongoing read on whether GPT’s strategy is actually working, there are three numbers worth keeping on your dashboard. Not because they tell you everything—but because they usually tell you first.

1. Like-for-Like Net Property Income Growth by Sector

This is the closest thing you get to a “same store sales” view of a property portfolio. It strips out the noise of acquisitions and disposals and asks a simple question: are the assets GPT already owns producing more income than they did last year?

In the most recent period: Retail delivered 5.6% like-for-like net property income growth. Office delivered 6.5%. Logistics delivered 5%.

The key isn’t just the absolute growth. It’s whether the sectors start to move in different directions. Persistent divergence is often the early warning that the portfolio mix needs to change.

2. Office Portfolio Occupancy and Weighted Average Lease Expiry

If logistics is the tailwind story and retail is the “still resilient if you own the right centres” story, office is still the big uncertainty. That makes two measures especially important: how full the buildings are, and how long tenants are contractually committed.

GPT’s office occupancy sat at 94.4%, with a weighted average lease expiry of 4.8 years.

In a hybrid work world, these are leading indicators. Falling occupancy, or a shortening WALE, is often how the risk shows up before it hits earnings.

3. Funds Management Assets Under Management Growth

This is the platform metric. A growing AUM base expands fee income that isn’t dependent on GPT owning every dollar of property on its balance sheet—and it’s a signal that institutions are still willing to back GPT as a manager and partner.

Assets under management increased by $2.2 billion to $36.6 billion.

In practical terms: if this keeps growing, GPT has more options—more partners, more capital, and more flexibility to execute the next pivot before it’s forced.

XIV. Epilogue: What's Next for GPT?

As GPT approaches its 54th year on the ASX, the story becomes less about where it came from—and more about the choices it makes from here.

The office question is still the big one. GPT’s office portfolio sits at around 5% vacancy, but the bigger challenge is what’s ahead: longer-dated lease expiries that will roll in a market where tenants have more leverage and less certainty about how much space they truly need. GPT’s CBD assets are among the best in the country, but “best” doesn’t make you immune to a structural shift. The open question is whether premium towers can hold their ground in a hybrid world—or whether the next decade forces more aggressive repositioning than the last one did.

On the other side of the ledger is logistics, where the tailwinds haven’t gone away. The QuadReal partnership remains central to that push. The plan for the second vehicle is to keep deploying new capital—targeting another $500 million—into stabilised, core-plus logistics opportunities across the major east coast markets. GQLT2 is positioned as QuadReal’s primary vehicle to scale in Australia, and GPT will operate and manage it. It’s a very modern version of GPT’s old advantage: not just owning assets, but being the trusted manager and partner behind them.

That points to the broader strategic lever GPT now has: funds management. A larger platform can grow earnings without GPT having to buy every building on its own balance sheet. With an established funds management business and about $32 billion of assets under management, GPT’s path to compounding increasingly runs through being a steward of institutional capital, not just a holder of property.

Then there’s the next frontier: the Living sector. Student accommodation is already on the map, and over time, residential exposure could further diversify the portfolio—especially if office demand remains contested and logistics becomes more crowded. Layered over all of it is sustainability, where GPT has spent years building credibility. As ESG mandates increasingly shape how global institutions allocate capital, that edge could become less reputational and more financial—showing up in partner demand, tenant demand, and cost of capital.

Zoom out, and GPT’s arc is a neat mirror of modern Australian capitalism: from Lendlease paternalism and Dick Dusseldorp’s pioneering vision, through the leverage-fuelled ambition and near-death of the Babcock & Brown era, to today’s diversified platform built around discipline, partnerships, and portfolio balance.

For investors, it’s also a reminder that innovation cuts both ways. The same instinct that created Australia’s first property trust also helped justify a joint venture that nearly broke the company. GPT’s lasting takeaway—and its defining advantage today—is that it kept the innovation, but learned the humility. In real estate, that’s not a slogan. It’s survival.

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music