Fisher & Paykel Healthcare: From Preserving Jars to Saving Lives

I. Introduction & Episode Roadmap

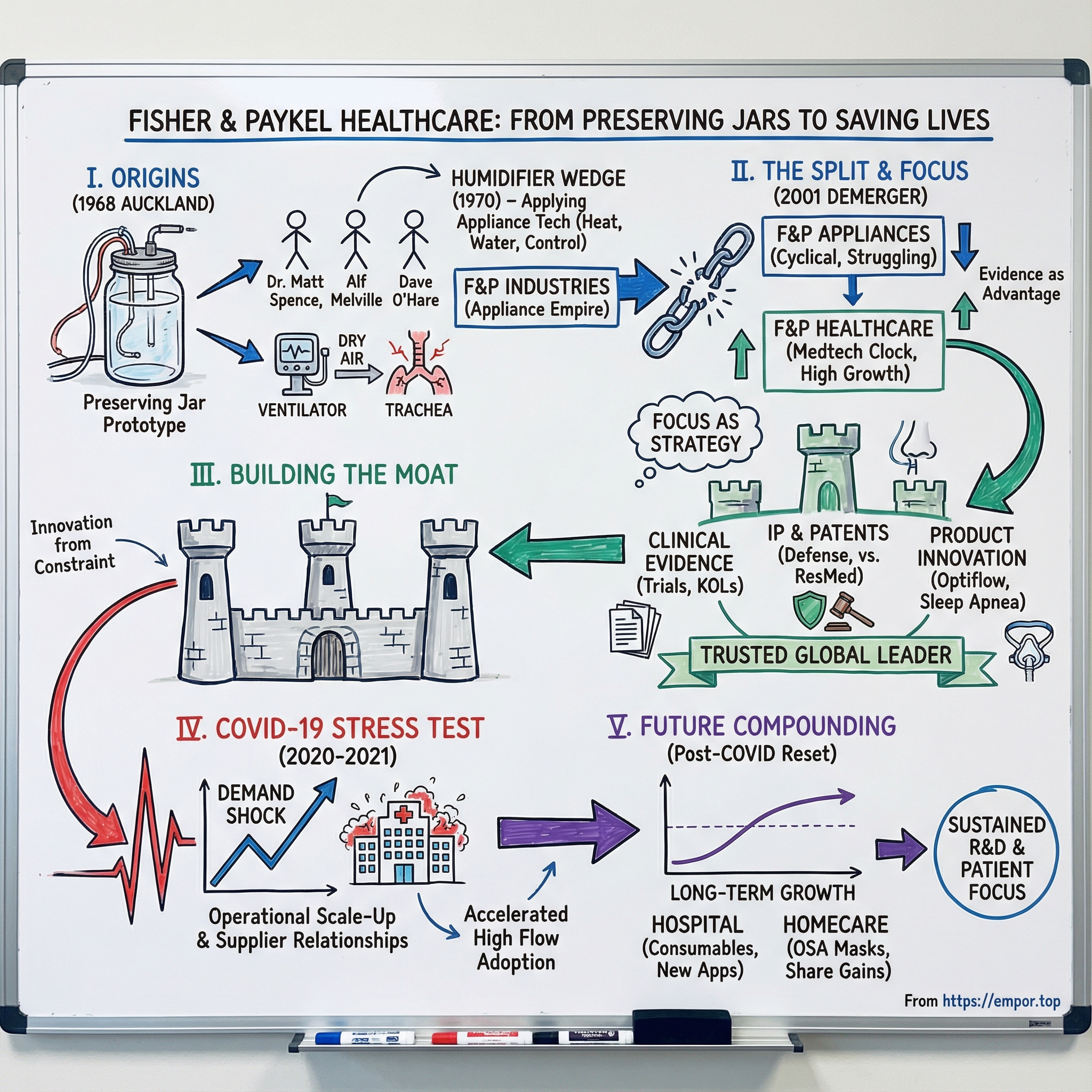

Picture this: 1968 in Auckland, New Zealand. Inside the Acute Respiratory Unit at Auckland Hospital, Dr. Matt Spence is watching something unsettling unfold. His patients are alive because they’re connected to mechanical ventilators, but the treatment is creating a new problem. The air being pushed into their bodies is cold and dry. Their tracheas are drying out, cracking, and becoming infected. The machine is keeping them breathing, but it’s also doing damage.

Spence doesn’t call a medical device company—because in New Zealand at the time, there isn’t really one to call. Instead, he pulls together an unlikely trio: Alf Melville, a government electrical engineer at the Department of Scientific and Industrial Research, and Dave O’Hare, a senior engineer at Fisher & Paykel Industries—best known for refrigerators and washing machines.

Together, they chase a deceptively simple idea: what if ventilated air could be warmed and humidified, the way the human body naturally does it? Their early prototype wasn’t built in a gleaming lab. It was built from what they had: an Agee fruit preserving jar, an aluminium scroll, and blotting paper. Three engineers, a jam jar, and a clinical problem that desperately needed solving.

That “proof of concept” moment is the seed of everything that follows. It’s clinical insight meeting practical engineering. It’s innovation born from constraint. And it’s a company, originally built to make appliances, discovering that its real edge might be in keeping people alive.

Fast forward, and Fisher & Paykel Healthcare becomes one of the three largest respiratory care device companies in the world. It leads in hospital humidifiers, masks, and consumables, and it’s the number three player in at-home sleep apnea treatment. What started as a side project inside an appliance company grows into one of New Zealand’s most valuable public businesses, selling systems in roughly 120 countries and earning the vast majority of its revenue offshore.

Which raises the question worth building an entire story around: how did a New Zealand appliance company’s experiment—literally built from a preserving jar—turn into a global healthcare leader? And what made it durable enough to fight through years of patent disputes, ride the COVID-19 demand shock, and still come out positioned for long-term growth?

That’s the journey we’re going to take: from refrigerators to respirators; through the 2001 demerger that set the healthcare business free; into the COVID-era stress test that validated decades of product and clinical investment; and, finally, into the moat Fisher & Paykel Healthcare built in a market defined by high stakes, high switching costs, and intense competition. Along the way, a few themes keep showing up: focus as strategy, evidence as an advantage, and the discipline to keep building through the cycle—not just at the peak.

II. Origins: The Appliance Empire That Spawned a Healthcare Giant

To understand Fisher & Paykel Healthcare, you have to start with the company it came from. Not a medtech lab. An appliance business, built in a small, remote country that kept forcing its best companies to get good at doing more with less.

Fisher & Paykel Industries Ltd was founded in 1934 by two young friends: Woolf Fisher and Maurice Paykel. Fisher was the salesman with sharp business instincts. Paykel brought family importing connections. And they picked the right moment. New Zealand in the 1930s was hungry for modern conveniences, and refrigeration was beginning to change everyday life.

At first, Fisher & Paykel was an importer, bringing in brands like Crosley, Maytag, and Pilot. But in 1938 the rules of the game changed. The First Labour Government introduced tariffs and restrictions designed to protect local jobs, and importing got a lot harder. Most companies faced with that kind of policy shock either shrink or disappear.

Fisher and Paykel did something else: they pivoted. The business moved from importing to manufacturing, beginning with Kelvinator washing machines produced under license. What started as a defensive move became the foundation of an advantage. They were forced to build real engineering muscle—tooling, production lines, quality control, and, crucially, the kind of temperature and mechanical control you need when you’re trying to make machines that behave predictably in real homes.

In 1956, the company moved manufacturing into a purpose-built factory in Mount Wellington, Auckland. It wasn’t just bigger. It was set up for flexible production, with machinery techniques developed alongside raw material suppliers, and it allowed Fisher & Paykel Industries to scale output dramatically.

Along the way, they consolidated the local market too. In 1955, Fisher and Paykel acquired Dunedin electric oven manufacturer H. E. Shacklock Ltd, a dominant name in New Zealand appliances during the protectionist era. Over time, the Shacklock brand was phased out and absorbed into the Fisher & Paykel line.

By the 1960s, Fisher & Paykel had become a major force in Australasian appliances. And more importantly, it had accumulated a very specific kind of expertise: heating elements, thermostats, precision manufacturing, and the electronics needed to control them. These weren’t abstract skills. They were practical, hard-won capabilities—how to move heat, manage water, and make complex electromechanical products reliable at scale.

Around 1968, the company began exporting within Australasia and East Asia. And right around that same period, it collided with the problem Dr. Matt Spence was seeing in Auckland Hospital.

Because if you step back, the link is almost obvious. Medical humidification isn’t magic. It’s precise temperature control. Reliable water management. Safe, repeatable performance. The exact things you need to master to build great appliances.

So when Fisher & Paykel’s engineers looked at a ventilator drying out a patient’s airway, they didn’t see an alien medical problem. They saw a familiar engineering challenge—heat and moisture, controlled carefully, delivered reliably.

That appliance heritage would echo through everything that came next: the manufacturing discipline, the obsession with reliability, the ability to produce complex systems in volume. Inside this appliance conglomerate, a new kind of business was about to take shape—one that would eventually outgrow the parent that made it possible.

III. The Healthcare Division Is Born: A Preserving Jar That Changed Everything

To really grasp what happened in Auckland in the late 1960s, you have to remember what respiratory care looked like back then. Mechanical ventilation was already a life-saving miracle of intensive care. But it came with a brutal flaw: the air delivered to patients was cold and bone-dry, nothing like the warm, humid air our bodies condition naturally.

The result was predictable and awful. Airways dried out. Tissue cracked. Infections took hold. The machine that kept you alive could also leave you weaker, sicker, and harder to wean off support.

Dr. Matt Spence saw that tradeoff up close in Auckland Hospital’s Acute Respiratory Unit. And instead of accepting it as the cost of doing business, he went looking for help in a place that sounds almost ridiculous on paper: the appliance industry.

Spence teamed up with Alf Melville, a government electrical engineer, and Dave O’Hare, a senior engineer at Fisher & Paykel Industries. The collaboration produced a prototype humidifier built from the materials they had on hand, including a humble fruit preserving jar. But the jar wasn’t the point. The point was the leap: treat a medical problem like an engineering system—heat, water, control, reliability—and make it work in the most unforgiving environment imaginable.

From there, Fisher & Paykel did what it knew how to do. A small team took the prototype and pushed it across the hard line that separates “clever idea” from “real product.” The challenge sounds simple: warm water to body temperature, saturate the airflow, and deliver it through a breathing circuit.

In practice, it demanded everything Fisher & Paykel had learned building appliances at scale. The device had to be safe, with no risk of overheating. It had to be dependable, because failure in ICU isn’t an inconvenience—it’s catastrophic. And it had to be affordable enough that hospitals could actually adopt it.

In 1970, the first respiratory humidifier was sold, and it wasn’t treated as a local novelty. It was marketed internationally.

That’s the foundational insight that launched the whole business: what Fisher & Paykel had mastered in kitchens and laundries—heating elements, thermostats, precision manufacturing, quality control—mapped shockingly well onto medical humidification. They weren’t medical device specialists who happened to learn manufacturing. They were manufacturers who learned, quickly, that their craft could translate into better medicine.

The humidifier became more than a product. It became a wedge. It pulled Fisher & Paykel deeper into healthcare, eventually forming a dedicated health-care division—one that would later become a standalone company in 2001.

And once that door opened, it didn’t close. Over the next two decades, the medical division broadened its range, found new clinical uses, and built the early foundations of what would become Fisher & Paykel Healthcare.

By 1990, the medical division had been renamed Fisher & Paykel Healthcare, with annual sales reaching NZ$29 million—meaningful growth for something that started as a side project and a preserving jar.

In 2006, the company launched Optiflow nasal high flow therapy, delivering heated, humidified oxygen at high flow rates. It quickly gained adoption for managing acute respiratory distress.

Optiflow matters because it shows Fisher & Paykel doing something rarer than making a better version of an existing product: it helped push a new therapy approach into mainstream use. Traditional oxygen delivery could only go so far before it became uncomfortable or ineffective. High-flow nasal therapy changed the equation by delivering higher flows in a way patients could actually tolerate—often without face masks, and sometimes helping avoid more invasive escalation.

Through the 2000s, Fisher & Paykel Healthcare also expanded into obstructive sleep apnea with humidified CPAP systems, and into surgical settings with humidification solutions for procedures like laparoscopy, aimed at reducing issues such as hypothermia and tissue drying.

The pattern is clear. Rather than staying a one-hit wonder tied to invasive ventilation, the company kept expanding into adjacent applications—different settings, different patients, same core competency. All roads led back to a single obsession: getting humidification and respiratory support right, then building a product portfolio around it.

IV. The Hidden Gem Within: Growing Pains and the Case for Separation

By the mid-1990s, Fisher & Paykel Industries had a good problem that was starting to look like a dangerous one. Inside the same corporate wrapper sat two businesses with totally different rhythms—and they were pulling the company in opposite directions.

On one side: appliances. Capital-intensive, cyclical, and increasingly squeezed by low-cost Asian competition. Margins were under pressure, and growth meant continually pouring money back into factories and production capacity. It was still largely a domestic story, with some regional exports, but the center of gravity was New Zealand and Australia.

On the other side: the medical division. It looked nothing like an appliance business. By the first half of 1997–98, it contributed 50% of the company’s profit and exported more than 95% of what it made. This was a high-margin, high-growth global operation sitting inside a conglomerate whose public identity—and investor expectations—were built around whitegoods.

And that mismatch wasn’t just academic. It showed up in the hardest place: capital allocation. Appliances demanded constant reinvestment to stay competitive on cost and features. Healthcare demanded sustained R&D and the slow, expensive work of building clinical evidence and long-term relationships with hospitals. One business won by moving fast and competing on price. The other won by being patient, methodical, and trusted.

Even the shareholder logic diverged. Appliance investors tended to want dividends and discipline. A healthcare investor looked at the same income statement and wanted the company to reinvest aggressively—because in medical devices, the payoff often comes years after the spending.

The export profile made the contrast unavoidable. Fisher & Paykel Healthcare’s international sales were more than 90% of its turnover. Appliances, by comparison, remained predominantly domestic. These weren’t complementary engines. They were two different enterprises that just happened to share a name, a board, and a balance sheet.

So the argument for separation started to harden: if the healthcare division were set free, it could attract investors who understood medtech timelines and would underwrite long-term R&D. And if appliances stood on its own, it could pursue its own strategy without constantly competing for attention and funding against a faster-growing sibling.

That idea didn’t become reality overnight. Preparations began for a major restructuring to split Fisher & Paykel Healthcare from Appliances—a process that would take years of planning, approvals, and careful stakeholder management. But the strategic logic was getting harder to ignore: two businesses, two playbooks, two futures. The only question was when the company would finally let each one run on its own.

V. The Demerger: Liberation Day

By 2001, the logic for a split had gone from “interesting idea” to “we can’t keep pretending these are the same company.” So in November of that year, Fisher & Paykel Industries broke in two: Fisher & Paykel Appliances Holdings Ltd on one side, and Fisher & Paykel Healthcare Corporation Ltd on the other.

This wasn’t a quiet internal reshuffle. Fisher & Paykel Healthcare became its own public company, with securities listed in New Zealand and Australia. It also took a swing at a U.S. listing, but that Nasdaq chapter didn’t last; the listing was terminated in February 2003 as the company focused on its core Australia–New Zealand investor base.

For Healthcare, the separation did exactly what the architects of the demerger hoped it would: it removed the gravitational pull of appliance cycles and let the business run on a medical-device clock. Long development timelines. Heavy R&D. Clinical relationships that take years to earn. Capital allocation built around compounding, not quarterly margin firefights.

The years that followed turned the split into a case study. The two businesses didn’t just perform differently—they revealed how different they really were.

Fisher & Paykel Appliances, facing brutal competition and the economics of large-scale manufacturing, ended up under real strain. In 2009, Haier Group acquired 20% of its shares. By 2012, with the appliances business struggling under nearly NZ$500 million of debt, relocating manufacturing to lower-cost countries, and dealing with weaker demand after the global financial crisis, Haier increased its stake to more than 90%. The transaction closed in early November. Haier then used compulsory acquisition provisions to buy out the remaining shareholders, and Fisher & Paykel Appliances was delisted from the NZX later that month.

Meanwhile, the healthcare company—now fully focused, and no longer competing internally for attention and investment—kept building. The end result is the cleanest validation of the original thesis: the healthcare division, once the hidden gem inside a conglomerate, grew into New Zealand’s most valuable company, with a market capitalization now above NZ$21 billion.

If there’s a single strategic lesson embedded in the demerger, it’s this: focus isn’t just a management slogan. In the right business, with the right tailwinds, it can be a value-creation machine.

VI. Building the Moat: Product Innovation and Clinical Evidence

Independence didn’t just give Fisher & Paykel Healthcare freedom. It gave the company permission to do what medical-device businesses have to do to win: pick a few arenas, invest for the long term, and keep stacking advantages that are hard to copy.

The strategy crystallized into two major product groups. First: hospital respiratory care—humidifiers, single-use and reusable chambers, breathing circuits, and accessories designed to humidify and deliver gases across mechanical ventilation, non-invasive ventilation, oxygen therapy, and even laparoscopic surgery. Second: homecare—primarily masks and devices for treating obstructive sleep apnea.

That focus mattered. In hospitals, Fisher & Paykel’s active humidification technology became a go-to approach for maintaining airway conditions during ventilation. And as global adoption grew, the financials followed. By 2010, operating revenue had reached NZ$503 million, powered largely by international sales.

But the product story that best captures how Fisher & Paykel built its moat is Optiflow nasal high flow therapy—because Optiflow wasn’t just “a better widget.” It helped define a new way to treat patients.

Before high flow, clinicians were boxed in by tradeoffs. Face masks could be uncomfortable. Low-flow nasal cannulas could only deliver so much support. And mechanical ventilation—often requiring intubation—was invasive and came with serious risks. There was an obvious gap in the middle: patients who needed more respiratory support than conventional oxygen therapy could provide, but who weren’t yet at the point of intubation.

Fisher & Paykel’s engineers and clinical researchers went after that gap. They developed a system that could deliver heated, humidified oxygen at very high flow rates through a nasal interface patients could actually tolerate. The leap wasn’t just higher flow. It was making high flow usable: warm, humidified gas delivered comfortably enough to be sustained, not endured.

The result is that nasal high flow has grown into a large and fast-expanding therapy category. The broader high-flow nasal cannula market was estimated at about USD 8.07 billion in 2025 and projected to reach USD 13.30 billion by 2030, driven by widening adoption of heated, humidified high-flow oxygen therapy and its clinical benefits.

Underneath that kind of category creation is a very specific R&D philosophy: long-horizon, high conviction, and persistent. In the 2025 financial year, Fisher & Paykel Healthcare invested 11% of revenue—$226.9 million—into R&D. More broadly, the company has kept R&D spending around the 9–11% range, building a pipeline that compounds over time and is difficult for competitors to match consistently.

But spending is only the starting line. What made Fisher & Paykel especially formidable was how it treated clinical evidence like a strategic asset. The company sponsored clinical trials, built relationships with key opinion leaders in respiratory medicine, and used the accumulating body of evidence to shift clinical practice. That isn’t marketing in the usual sense. It’s the slow work of making a therapy standard of care—so adoption becomes about outcomes and protocol, not persuasion.

Over decades, that approach also produced a deep intellectual property position. Fisher & Paykel conducts its own R&D and has thousands of patents and pending applications, alongside manufacturing operations in New Zealand and Mexico and a multichannel distribution model. The point of that portfolio isn’t just bragging rights. It’s defense: a dense thicket of protections across components and designs that makes “just copy it” far harder than it sounds.

Finally, the company kept widening the circle around its core competency. Expanding into pediatric and neonatal applications let Fisher & Paykel take technologies proven in adult respiratory care and adapt them to patients with very different physiological needs. The science changes, the requirements get stricter, but the underlying capability—precise humidification and respiratory support—transfers. It was a disciplined way to grow the addressable market without abandoning what the company was best at.

VII. The Patent Wars: Fighting for Survival Against ResMed

In medical devices, competition doesn’t just play out in hospitals and sales calls. It plays out in court. And for Fisher & Paykel Healthcare in the late 2010s, that meant a drawn-out, high-stakes patent fight with ResMed, the dominant force in sleep apnea.

These weren’t one-off skirmishes. Over several years, the two companies—both making overlapping products across respiratory and acute care—ended up in legal battles across the US, New Zealand, Australia, and parts of Europe. It was expensive, distracting, and strategically destabilizing for both sides.

The stakes were not abstract. ResMed pushed for bans on the import and sale of Fisher & Paykel’s Simplus full face mask, and its Eson and Eson 2 nasal masks in the US. If that had gone the wrong way, it could have materially damaged Fisher & Paykel’s sleep apnea business in its most important market. And because these disputes ran in parallel venues—think the US alongside countries like Germany and the UK—the uncertainty lingered. Even when one case moved, another could flare up.

This is what patent warfare looks like in a mature, regulated category. These companies don’t just compete on features; they compete on the right to sell the product at all. And when you zoom out, you can see why the IP arsenals are so large: ResMed has said it has around 5,000 patents, while Fisher & Paykel estimated it held and had applied for around 2,000. In other words, patents aren’t decoration. They’re a core part of the competitive perimeter.

In February 2019, the perimeter finally stopped shifting. ResMed and Fisher & Paykel Healthcare announced an agreement to settle all outstanding patent infringement disputes between them in all venues worldwide. In a joint statement, they said the confidential settlement involved no payment and no admission of liability by either side. All ongoing infringement proceedings against the named products were dismissed, and each party agreed to cover its own legal fees and costs.

The practical outcome was simple: the lawsuits ended, and so did the threat of further infringement proceedings against the listed products—on both sides. That included ResMed products like AirSense flow generators, AirFit P10, Swift LT and Swift FX masks, and ClimateLine heated tubes; and Fisher & Paykel Healthcare products including Simplus, Eson, and Eson 2.

For Fisher & Paykel Healthcare, it marked the end of a draining period of uncertainty. CEO Lewis Gradon put it plainly: “We are pleased to bring these disputes to a close and we appreciate the support of our customers and shareholders throughout the process. The intellectual property we have generated through our investment in R&D over the past 50 years has enabled us to positively impact the lives of many millions of patients. We have an ongoing commitment to improve patient care and outcomes through inspired and world-leading healthcare solutions and this resolution supports that commitment.”

The broader lesson is the one every medtech company eventually learns. Intellectual property isn’t just a line item in an annual report. When the market is big enough and the switching costs are real, patents become a battlefield. And when that fighting finally ends, the real prize isn’t winning a point in court—it’s getting back to building products, expanding relationships, and focusing on patients.

VIII. COVID-19: The Accidental Stress Test

Nothing in Fisher & Paykel Healthcare’s fifty-year history looked quite like what began in January 2020. COVID-19 didn’t just increase demand for respiratory care—it pulled it forward, all at once, everywhere. As hospitals scrambled for ways to support patients in respiratory distress, Optiflow nasal high flow therapy emerged as one of the leading frontline treatments.

The business was already heading into a strong year before the pandemic hit. Then the curve bent sharply upward. Growth was driven by broader use of Optiflow, surging demand for products used to treat COVID-19 patients, and a wave of hospital hardware sales. CEO Lewis Gradon captured the moment: “The 2020 financial year was already on track to deliver strong growth before the coronavirus impacted sales. Beginning in January, the demand for our respiratory humidifiers accelerated in a way that has been unprecedented.”

By the first four months of the 2021 financial year, through to the end of July 2020, demand for hospital respiratory care products was tracking the global spread of COVID-19. It also reflected something even more important: a shift in clinical practice toward leading with nasal high flow therapy for COVID-19 patients in hospital. Hardware sales climbed rapidly, with revenue growth reported at +390% in constant currency to the end of July compared with the prior comparable period.

Then came the full-year results that put a number on what the world was asking Fisher & Paykel Healthcare to do. For the year ended 31 March 2021, operating revenue reached $1.97 billion, up 56% (61% in constant currency). Net profit after tax rose 82% to $524 million (94% in constant currency). Hospital revenue did the heavy lifting, growing to $1.50 billion, up 87% (94% in constant currency).

But the real story of COVID wasn’t just financial. It was operational. The pandemic turned the company into a live-fire test: could it scale output at speed without compromising quality and safety? Fisher & Paykel Healthcare had to expand manufacturing capacity fast, while the rest of the world was fighting shortages, disrupted logistics, and supply constraints.

That pressure didn’t let up quickly. In the first three months of the 2021 financial year, hospital growth continued to accelerate, with hardware growth of over 300%. Consumables rose too, tracking at more than a one-third increase compared to the same period the year before. And as clinicians gained confidence with Optiflow during COVID-19, the company expected that familiarity would spill into broader use for non-COVID respiratory care.

A big part of the company’s ability to deliver came down to relationships built long before anyone had heard of the virus. When raw materials and components became hard to source globally, Fisher & Paykel Healthcare leaned on long-term supplier partnerships. In a world where everyone was trying to buy the same things at the same time, trust and history mattered—and suppliers prioritized the company as a customer.

The company also tried to reflect, in tangible ways, what the period demanded of its people. Gradon said that to recognise “the incredible contributions of our people,” the board approved a profit-sharing bonus totalling $29 million for the 2021 financial year, to be paid to everyone who had worked for a qualifying period. It also committed $20 million to establish the Fisher & Paykel Healthcare Foundation in the same year, with charitable purposes that include supporting health research and programs to improve access to healthcare, supporting environmental protection initiatives, and promoting awareness of opportunities in science, technology, engineering and mathematics.

From the outside, the company’s performance attracted praise as well. Judge Neil Paviour-Smith, managing director of Forsyth Barr, said, “Fisher & Paykel Healthcare’s ongoing investment in innovation and development of leading products underpins its success. Overlaid with a well-regarded and high performing management team, it is the standout winner this year.”

And perhaps the most enduring impact of the COVID-19 period wasn’t the spike—it was what the spike left behind. Hospitals worldwide gained hands-on experience with nasal high flow therapy. Staff were trained on Fisher & Paykel systems. Hardware was installed across wards and units that previously didn’t have it. That pandemic-driven familiarity, and the throughout-hospital acquisition of hardware devices, substantially reduced the barriers to using nasal high flow therapy more broadly—well beyond COVID-19.

IX. The Post-COVID Hangover and Reset

What goes up must come down—or at least come back to earth. After COVID pulled years of demand forward, the next chapter was always going to be a reset. And for Fisher & Paykel Healthcare, it was a painful one: not because the business broke, but because the comparisons were brutal and the world stopped buying emergency volumes of hardware.

Even so, the company didn’t snap back to “pre-COVID.” Coming off the extraordinary 2021 financial year, performance in 2022 was still meaningfully higher than the old baseline, with operating revenue about a third above the pre-pandemic 2020 level. But the direction had changed. Total operating revenue in the 2022 financial year was $1.68 billion, down 15% (14% in constant currency). Net profit after tax fell to $376.9 million, down 28% (30% in constant currency).

The normalization continued into 2023. Total operating revenue for the 2023 financial year was $1.58 billion, down 6% (9% in constant currency) from 2022. Net profit after tax was $250.3 million, down 34%. And the clearest sign of the “hardware hangover” was in hospitals: hardware sales were down 53% in constant currency, largely because 2022 had still been heavily shaped by global COVID surges.

Importantly, management kept drawing a line between what was temporary and what was structural. Pandemic demand was always going to fade. But the underlying trend that mattered most to Fisher & Paykel Healthcare—the steady expansion of nasal high flow therapy into broader respiratory support—was still intact. In the company’s own longer-term view, the pre-COVID trend toward increased use of nasal high flow therapy was expected to continue.

And the pandemic, paradoxically, strengthened that trend. Extensive practitioner familiarity, plus the fact that hospitals had purchased and deployed hardware throughout their systems, substantially reduced the friction to using nasal high flow therapy in more situations—not just COVID wards.

By 2024, you could see the business finding its footing again. For the 2024 financial year, operating revenue grew 10% to $1.74 billion (8% in constant currency). Underlying net profit after tax rose 6% to $264.4 million (5% in constant currency). Hospital revenue grew 6% to $1.1 billion, while Homecare operating revenue grew 18% to $652.3 million, including strong growth in obstructive sleep apnea masks.

Zoom out, and the through-line becomes clearer than any single year. From $503 million in operating revenue in 2010 to $1.74 billion in 2024, the company more than tripled over 14 years—even with the pandemic spike and the inevitable comedown.

Then, in the 2025 financial year, Fisher & Paykel Healthcare hit a psychological—and operational—milestone. Reporting results for the year ended 31 March 2025, Managing Director and CEO Lewis Gradon said: “During the 2025 financial year, we stayed focused on the fundamentals of our business and we achieved strong results, with annual revenue of more than $2 billion for the first time in our history.”

Total operating revenue rose 16% to $2.02 billion (14% in constant currency). Underlying net profit after tax increased to $377.2 million. Growth came from both sides of the house: Hospital operating revenue rose to $1.28 billion, and Homecare reached $739.9 million, with obstructive sleep apnea masks continuing to grow. The company also kept its long-term posture intact, investing 11% of revenue—$226.9 million—into R&D.

The headline takeaway is simple: the boom ended, the hangover hurt, and then the compounding resumed. By 2025, the post-COVID reset looked largely complete—back to growth, still investing heavily in the pipeline, and now operating at a scale that would have seemed impossible back when the whole thing started with a jam jar in an Auckland ICU.

X. The Playbook: Business & Strategy Lessons

Step back from the products and the financial swings, and Fisher & Paykel Healthcare starts to look like a repeatable playbook. Not a one-time lucky break with a preserving jar, but a set of choices—made again and again—that compound over decades.

Innovation from constraint: New Zealand forced Fisher & Paykel Industries to become a manufacturer, not just an importer. That constraint built deep expertise in making reliable, temperature-controlled electromechanical products at scale—exactly the kind of know-how that later translated into respiratory humidification. The first humidifier prototype, built from a fruit preserving jar, is the perfect symbol of the pattern: not abundance, but ingenuity under limitations. It’s also a reminder that the company’s roots are in adapting when circumstances change.

Focus as strategy: The 2001 demerger didn’t just “unlock value” in a spreadsheet sense. It gave each business the right operating system. Healthcare got to run on a medtech clock—long R&D cycles, clinical relationships, evidence-building. Appliances stayed in the brutal world of cost, capital intensity, and constant price pressure—and eventually ended up absorbed by Haier after years of strain. The contrast is the point: when fundamentally different businesses share a balance sheet, something usually gets starved. Focus lets the right strategy win.

Clinical evidence as moat: Fisher & Paykel Healthcare doesn’t treat research as a sales aid. It treats it as infrastructure. Clinical studies validate outcomes, influence guidelines, and build credibility with the clinicians who actually decide what gets used. Over time, that evidence becomes a compounding advantage: more usage leads to more data, more studies, and more clinical comfort. The adoption of Optiflow is a case in point—decades of clinical groundwork created a foundation a new entrant can’t simply buy or rush.

Long-term thinking: Medical devices don’t reward impatience. They take years to develop, prove, manufacture, and scale—especially when you’re trying to change clinical practice. During COVID, the company still kept its pipeline moving, rather than letting the urgency of the moment hijack the long view. That only works when management and shareholders are aligned around multi-year payoffs, and the company’s leadership stability suggests that alignment has held.

Supplier relationships: The pandemic revealed a quiet strength: resilience built through relationships. When components and raw materials got scarce, Fisher & Paykel Healthcare benefited from supplier partnerships built over many years, with suppliers often prioritizing them as a customer. It’s not a “moat” you can point to on the balance sheet, but in a crisis, it can be the difference between shipping and not shipping.

Culture of patient focus: The company says it plainly: “We believe in doing what is best for the patient. We believe people are our strength. We believe the commitment to doing the right thing is what our customers will find compelling.” In a business like this, that isn’t just language. It shows up in what gets funded, what gets studied, and which problems the company chooses to solve. And over decades, that kind of orientation can be a competitive advantage—because trust, in healthcare, is hard-won and easily lost.

XI. Porter's Five Forces & Hamilton's Seven Powers Analysis

Porter's Five Forces

Threat of New Entrants: LOW

If you’re thinking about “a startup taking on Fisher & Paykel,” respiratory care is one of the worst categories to try it in. The regulatory path alone—FDA clearances in the U.S., CE marking in Europe, TGA approvals in Australia—demands deep documentation, testing, and time. Then comes the real grind: clinical evidence. Hospitals and clinicians don’t switch serious respiratory therapies on vibes; they switch on outcomes, protocols, and trust built over years.

Layer in Fisher & Paykel’s in-house R&D engine and its large patent portfolio, and the barrier becomes more than money. It’s accumulated know-how, protected designs, and credibility that can’t be bought quickly. Finally, there’s procurement reality: hospital qualification processes are slow, multi-stakeholder, and designed to reduce risk. That structure naturally favors incumbents.

Bargaining Power of Suppliers: MODERATE

Medical-grade components aren’t commodity parts—you need qualified suppliers, consistent quality, and reliable delivery. But Fisher & Paykel Healthcare isn’t dependent on a single source for everything, and its manufacturing footprint in New Zealand and Mexico gives it flexibility. Its multichannel distribution model helps too.

COVID was the stress test here. When supply chains seized up and everyone was chasing the same inputs, long-term supplier relationships mattered. Suppliers prioritized Fisher & Paykel Healthcare during global shortages, which is exactly what “moderate” supplier power looks like: you’re not immune, but you’re not helpless either.

Bargaining Power of Buyers: MODERATE-HIGH

Hospitals buy through increasingly consolidated procurement channels, and in the U.S. that often means Group Purchasing Organizations with real negotiating leverage. On paper, that pushes buyer power up.

But Fisher & Paykel has two counterweights. First, clinician preference and clinical evidence create real inertia—respiratory therapists and physicians want what they trust and what they’ve seen work. Second, the business model itself creates stickiness. Once a hospital has deployed hardware, trained staff, and built routines around a system, switching isn’t just swapping a vendor. It’s retraining, changing workflows, and revalidating performance. The consumables stream reinforces that lock-in.

Threat of Substitutes: MODERATE

In respiratory care, “substitute” doesn’t mean a cheaper competitor—it often means a different clinical pathway. The decision between invasive ventilation, non-invasive therapies, and nasal high flow is driven by patient condition and clinician judgment. Optiflow has helped define nasal high flow as a major therapy category, and meaningful substitution requires more than a similar-looking device; it requires comparable clinical evidence and adoption inside hospitals.

In sleep apnea, the substitutes are broader—oral appliances and surgical interventions exist as alternatives to CPAP—but they come with different tradeoffs and efficacy profiles. So substitution pressure is real, but not uniformly strong.

Competitive Rivalry: HIGH

This is a competitive arena with heavyweight incumbents. In sleep apnea devices, the market is led by ResMed, Philips, and Fisher & Paykel Healthcare, and together they account for a substantial share of global demand. ResMed holds the leading position in market share and is consistently rated highly by providers for CPAP and masks. Fisher & Paykel has been the smaller player in this trio, but it has been growing.

Then Philips changed the competitive landscape. The 2021 recall—covering certain ventilators, CPAP, and BiPAP machines—impacted millions of devices worldwide and triggered a consent decree that one report described as “very punitive,” making a rapid recovery in the U.S. market especially difficult.

That disruption created an opening. Fisher & Paykel has benefited, leveraging its humidification and interface expertise and winning tenders from hospitals looking for safety-certified alternatives. But make no mistake: rivalry remains intense, because the prize is large, the buyers are sophisticated, and switching costs cut both ways.

Hamilton's Seven Powers

Counter-Positioning: Fisher & Paykel’s emphasis on humidification and nasal high flow therapy is a differentiated bet. Larger incumbents like ResMed and Philips have historically been oriented around core CPAP and ventilator businesses, and leaning hard into Fisher & Paykel’s approach can risk cannibalizing their own product and profit centers. That creates space Fisher & Paykel can occupy more aggressively.

Scale Economies: This market includes major players such as Fisher & Paykel Healthcare, Teleflex, Vapotherm, Masimo (TNI medical AG), and ResMed. Fisher & Paykel’s manufacturing scale in Auckland and Mexico supports cost efficiency, purchasing leverage, and repeatable high-quality output—advantages that smaller competitors struggle to match.

Switching Costs: In hospitals, switching costs are very real. Once Optiflow is deployed, staff training, installed hardware, and day-to-day clinical routines start to assume Fisher & Paykel equipment. Consumables are specific to the platform. Changing systems means capital spend and workflow disruption, not just a new purchase order.

Network Effects: There aren’t classic social-network-style effects here. But there is an evidence flywheel: more usage leads to more data, which supports more studies, which influences guidelines and clinician comfort, which drives more usage. Over time, that compounding body of evidence behaves like a network effect.

Cornered Resource: Fisher & Paykel has framed it clearly: “The intellectual property we have generated through our investment in R&D over the past 50 years has enabled us to positively impact the lives of many millions of patients.” That long arc—patents plus clinical relationships—is not something competitors can replicate quickly, even with capital.

Process Power: The company’s appliance heritage shows up as operational capability. During COVID, Fisher & Paykel demonstrated it could scale output dramatically in a matter of months while maintaining quality. That’s not a one-off trick; it’s process power built over decades.

Branding: In hospital respiratory care, brand isn’t consumer marketing—it’s trust. Among respiratory therapists and intensivists, “Fisher & Paykel” carries weight because the products are reliable and the company has stayed close to clinical practice for decades. In a category where failure is unacceptable, that reputation is a competitive asset.

XII. Competitive Dynamics & Market Position

Zoom out, and respiratory care is exactly the kind of market where two things can be true at once: it’s growing fast, and it’s hard to break into. The category isn’t fragmented chaos. It’s moderately concentrated, with real competitive intensity among a handful of global players.

Overall, the global respiratory care devices market is projected to grow from about USD 23.6 billion in 2025 to USD 33.6 billion by 2030. The reasons aren’t mysterious. Populations are aging, chronic respiratory disease is rising, and decades of smoking and air pollution continue to show up in hospital wards and homecare prescriptions.

The competitive roster is familiar: Koninklijke Philips, Medtronic, ResMed, Fisher & Paykel Healthcare, and Dräger. Different histories, different strengths—but they all operate under the same reality: regulation is unforgiving, hospitals are conservative, and credibility is earned one clinical protocol at a time.

Within that landscape, Fisher & Paykel Healthcare sits in an interesting spot. In hospital humidification, it’s the market leader—a position built over decades of product iteration and clinical evidence. In homecare sleep apnea, it’s still the number three player behind ResMed and Philips, but it has been gaining share, especially in the aftermath of Philips’ recall.

That recall didn’t just hurt Philips; it reshuffled supply and trust across the category. ResMed was able to convert manufacturing capacity into share gains. Fisher & Paykel, meanwhile, leaned into product development and commercialization, including newer mask lines such as Nova Micro, while also pushing geographic expansion to broaden its revenue base.

If there’s one segment that best captures why this competitive dynamic matters, it’s high-flow nasal cannula. The high-flow nasal cannula market was estimated at USD 8.07 billion in 2025 and is forecast to reach USD 13.30 billion by 2030, reflecting a roughly 10.6% CAGR. That’s not just growth—it’s a signal that a therapy approach is still expanding into new use cases and settings.

What’s pulling that forward is the steady broadening of the evidence base. High flow is being supported across conditions and contexts like COPD, bronchiolitis, and peri-operative care, which expands adoption beyond ICU into emergency departments and wider hospital use, and potentially into home-care environments over time. The underlying disease burden keeps rising, too: COPD alone was estimated to affect around 200 million people and caused 3.2 million deaths in 2024. On the technology side, continued innovation—like integrated flow monitoring and tele-respiratory platforms—strengthens the value proposition for providers by improving oversight while lowering total cost of care.

Put it together and you get a market structure that tends to reward incumbents: clear leaders, high barriers to entry, and growth driven by durable demographic and clinical trends. Fisher & Paykel Healthcare’s leadership in hospital humidification, plus its growing presence in homecare, leaves it well positioned to keep compounding as the market expands.

XIII. Leadership: The Engineers Who Built an Empire

To understand Fisher & Paykel Healthcare, you have to understand the kind of leaders it tends to produce. This is an engineering-driven company, and the people at the top often look less like dealmakers and more like builders—technical operators who came up through product, manufacturing, and clinical collaboration, then stayed long enough to carry the company’s institutional memory forward.

Lewis Gradon fits that mold almost perfectly. He became Managing Director and Chief Executive Officer in April 2016, but by the time he stepped into the role he was hardly new to the job of steering the business. Before becoming CEO, he spent 15 years as Senior Vice President – Products & Technology, and six years as General Manager – Research and Development.

Across a 41-year tenure at Fisher & Paykel Healthcare, Gradon held a wide range of engineering roles and oversaw not just product development, but the building blocks that make a medtech company scale: manufacturing, quality, intellectual property, supply chain, and clinical research. He earned a Bachelor of Science degree in physics from the University of Auckland.

What that adds up to is a leadership archetype you don’t see as often anymore: the technical expert who rises by understanding the product and the process—how it gets designed, proven, manufactured, and delivered—rather than by financial engineering.

When Gradon was appointed CEO, the company highlighted that he had been with the business for 32 years, had served as Senior Vice President – Products and Technology since 2001, and had led Research and Development as General Manager from 1996. The message was clear: this was someone who already “led a significant part of the business, including R&D, clinical research, manufacturing and supply chain,” and had played a major role in executing the company’s international growth strategy.

That kind of continuity showed up in external recognition, too. Gradon was named The Deloitte Top 200 Chief Executive of the Year, with judges calling out his leadership during the COVID-19 period and the stability of the management team.

And he wasn’t alone. The broader leadership bench has also tended to skew long-tenured. Michael Daniell, who preceded Gradon as CEO, remained on the board, providing continuity and institutional memory. Across the executive team, there are leaders who have been inside the culture long enough to understand what matters here: the clinical details, the manufacturing realities, and the long product timelines.

Take sales leadership. Justin was appointed Vice President – Sales & Marketing in April 2024, but his story is emblematic of the company’s internal pipeline. He joined Fisher & Paykel Healthcare in Australia in 1988, moved through multiple sales management roles, and became President – North America in 1996, delivering significant revenue and earnings growth in the company’s largest market during his tenure.

The same theme shows up on the operations side. As Gradon put it: “We now have multiple manufacturing sites worldwide and a growing number of distribution locations. We want to create a sustainable business structure by establishing a global operations function which includes manufacturing and supply chain.” In that context, he argued that Andy was “well-suited for the Chief Operating Officer role,” citing experience leading large teams and complex projects, plus a deep understanding of the company’s culture, products, and customers.

For investors, this profile comes with a clear tradeoff. The upside is depth: leaders who understand the product, the clinicians, and the operating system of the business because they helped build it. The question it naturally raises is succession. When a company leans so heavily on long-tenured technical leadership, the key risk isn’t whether today’s team can execute—it’s how well the next generation is being prepared to take over when this one eventually steps away.

XIV. Recent Performance and Forward Outlook

The most recent results suggest the post-COVID reset is giving way to something more familiar for Fisher & Paykel Healthcare: steady, broad-based growth.

On 26 November 2025, the company reported its first-half results for the 2026 financial year (the six months ended 30 September 2025). Total operating revenue was $1.09 billion, up 14% on the prior comparable period, or 12% in constant currency. Net profit after tax rose 39% to $213.0 million, or 28% in constant currency. It was the first time the company had generated more than $1 billion of revenue in a first-half period—an important signal that growth wasn’t just a one-off pandemic surge, but something that could reassert itself in a normalized market.

Both product groups contributed. The Hospital product group grew 17% to $692.2 million, supported by strong demand across the portfolio and continued shifts in clinical practice. Homecare grew 10% to $395.9 million.

Management also provided full-year net profit after tax guidance of $410 million to $460 million—an indication of confidence that the momentum wasn’t limited to a single strong half.

Under the hood, the company continued to point investors back to the same long-term operating model. It reiterated its commitment to returning to a 65% gross margin target. In the 2025 financial year, gross margin was 62.9%, with an underlying improvement of 181 basis points, or 129 basis points in constant currency.

And, as always with Fisher & Paykel Healthcare, the story isn’t just results—it’s what’s being built for the next cycle. During the 2025 financial year, the company invested $226.9 million in research and development. It expanded the roll-out of the F&P Airvo 3 device and F&P 950 System in the United States, and increased adoption of its products in anaesthesia, including F&P Optiflow Switch and F&P Optiflow Trace. In Homecare, it added two new OSA masks: the F&P Nova Micro mask, launched in April 2024, and the F&P Nova Nasal mask, launched in March 2025.

Put together, the forward outlook rests on a set of reinforcing tailwinds the company knows well: broader clinical adoption of nasal high flow therapy, expansion into anaesthesia applications, an installed base of hardware that drives recurring consumables demand, and continued product-led share gains in sleep apnea masks.

XV. Key Investment Considerations

Bull Case

The bull case is pretty straightforward: Fisher & Paykel Healthcare has a core franchise that’s hard to dislodge, and it’s attached to therapy trends that are moving in its direction.

Start with hospital humidification. This is the company’s home turf, and it’s defended by decades of product iteration and a long track record of clinical evidence. In a hospital setting, “proven” matters, and once a system is installed and staff are trained, switching isn’t casual.

Then there’s nasal high flow therapy. Clinical practice has been shifting toward it for years, and COVID didn’t create that shift so much as accelerate it. The pandemic put Optiflow and related systems into far more hands, across far more wards, than would have happened in normal times. That installed base and familiarity can keep turning into broader everyday use.

In Homecare, the Philips recall created a structural opening in sleep apnea. Fisher & Paykel isn’t the category leader there, but it does have a growing mask portfolio and a chance to take share while customers and providers rethink their default options.

The engine behind all of this is sustained R&D. The company continues to invest heavily—around 11% of revenue—keeping the pipeline moving and reinforcing its technology edge in a category where reliability and incremental improvements compound.

Finally, there’s execution capacity. Manufacturing scale across New Zealand and Mexico supports cost competitiveness and the ability to serve global demand. And the revenue base is geographically diversified, with meaningful exposure across the US, Europe, and Asia-Pacific, which helps reduce reliance on any single market.

Bear Case

The bear case is less about whether Fisher & Paykel Healthcare is a “good company” and more about what could go wrong from here—especially at today’s expectations.

First, valuation. The stock trades at elevated multiples, which means the market is already pricing in a lot of continued strong performance. When expectations are high, even a modest stumble can hurt.

Second, competition. ResMed remains a formidable rival in sleep apnea, and if Philips successfully re-enters with force, pricing and share pressure could return quickly. This is not a market where incumbents quietly give up.

Third, category risk in sleep apnea. GLP-1 weight loss drugs such as Ozempic could, over time, reduce sleep apnea prevalence for some patients, which would gradually cap growth in parts of the addressable market.

Then there are macro and policy risks. Currency swings—especially movements in the New Zealand dollar—can create volatility in reported results. And shifts in US tariff policy could increase costs; the company itself has flagged tariffs as a near-term headwind.

Finally, there’s succession. One of Fisher & Paykel Healthcare’s strengths has been a long-tenured, deeply experienced leadership team. The flip side is that the team is aging, and the market will want confidence that the next generation can maintain the same product-driven, clinically grounded operating discipline.

Myth vs. Reality

Myth: Fisher & Paykel Healthcare is a COVID beneficiary that cannot sustain growth.

Reality: The company’s growth story started long before the pandemic. Revenue more than tripled from FY2010 to FY2024, and the underlying shift in clinical practice toward nasal high flow therapy remained intact—if anything, strengthened by COVID-era familiarity. FY2025, with revenue reaching $2.02 billion, showed the business could return to growth in a more normal environment.

Myth: The company is a niche player vulnerable to larger competitors.

Reality: In hospital humidification—its core franchise—Fisher & Paykel Healthcare is a market leader. More broadly, it sits among the top three global respiratory care device companies, and it has built meaningful IP protection through a large portfolio of patents and pending applications.

Myth: New Zealand origin limits global competitiveness.

Reality: This is a global exporter in every sense. Around 99% of revenue comes from outside New Zealand, across approximately 120 countries, and manufacturing in both New Zealand and Mexico adds flexibility and reduces dependence on any single geography.

XVI. Key Performance Indicators for Ongoing Monitoring

If you want a simple way to track whether Fisher & Paykel Healthcare is winning in the places that matter, you can boil it down to two KPIs. One tells you whether hospitals are truly adopting the therapy day to day. The other tells you whether the company is taking ground in a brutally competitive homecare market. Both are best viewed in constant currency to strip out FX noise.

1. Hospital Consumables Revenue Growth (Constant Currency)

Hospital consumables are the compounding engine. Hardware is what gets Fisher & Paykel into a hospital, but consumables are what prove the equipment is being used—patient after patient, ward after ward. When this line grows, it usually means the installed base is getting “worked,” clinical routines are forming, and the relationship is getting stickier.

It’s also a quality-of-revenue signal. Hardware sales can be lumpy and surge-driven. Consumables are recurring and usage-driven, which tends to translate into better visibility. In FY2025, new applications consumables grew 20% (18% in constant currency), pointing to continued expansion in how and where the systems are being used.

2. OSA Masks Revenue Growth (Constant Currency)

In obstructive sleep apnea, masks are the front door. This is where Fisher & Paykel is fighting for share against the category heavyweight, ResMed. Strong growth here typically means two things: the product pipeline is landing, and customers actually like what’s being shipped—comfort, fit, and usability are what drive reorders and recommendations in this category.

In FY2025, OSA masks revenue grew 14% (11% in constant currency), a sign the company continued to gain traction in homecare.

Together, these two metrics—tracked quarter by quarter—are the cleanest read on whether Fisher & Paykel Healthcare is executing its core strategy: deeper clinical adoption in hospitals, and steady share gains in sleep apnea.

XVII. Conclusion: The Preserving Jar Legacy

Fisher & Paykel Healthcare’s story is, at its core, a story about focus. Focus on the patient. Focus on respiratory care. Focus on the long game that medical device innovation demands.

It started in Auckland with a problem no one had solved well—and a prototype built from whatever was available, including a fruit preserving jar. From there, it grew into one of the three largest respiratory care device companies in the world, selling into around 120 countries and building a business that is, in every meaningful sense, global.

Along the way, the company’s journey—from appliance side project to independent healthcare leader—keeps circling back to the same durable ideas. Constraint can be an advantage if it forces you to build real capability. Focus isn’t a slogan; it’s a strategy that unlocks compounding. Clinical evidence, gathered painstakingly over years, becomes its own kind of momentum. And in healthcare, a culture anchored in doing the right thing for patients tends to travel surprisingly well into trust, adoption, and long-term economics.

By the time Fisher & Paykel Healthcare crossed $2 billion in annual revenue, it had leadership in hospital humidification, a powerful position in nasal high flow therapy, and growing momentum in sleep apnea masks. The moat—patents, clinical relationships, manufacturing strength, and brand trust in high-stakes clinical settings—looks hard-won and hard to copy. The leadership bench is deeply experienced, even as succession becomes a real question because so much of that expertise is long-tenured.

So the remaining debate isn’t whether this is a high-quality business. It’s what a high-quality business is worth. For investors, that comes down to price: how you balance a durable competitive position and secular tailwinds against premium valuation, competitive pressure, and the possibility that treatment pathways shift over time.

What doesn’t change is the origin story. Dr. Matt Spence’s 1968 instinct—to emulate the body’s natural humidification—set off a chain reaction. And that chain reaction didn’t just create a company. It helped reshape respiratory care in a way that has reached tens of millions of patients. The preserving jar was never the point. The mindset was. And that legacy—the habit of turning constraints into breakthroughs—still defines Fisher & Paykel Healthcare today.

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music