Evolution Mining: The Story of Australia's M&A-Driven Gold Champion

I. Introduction & Episode Roadmap

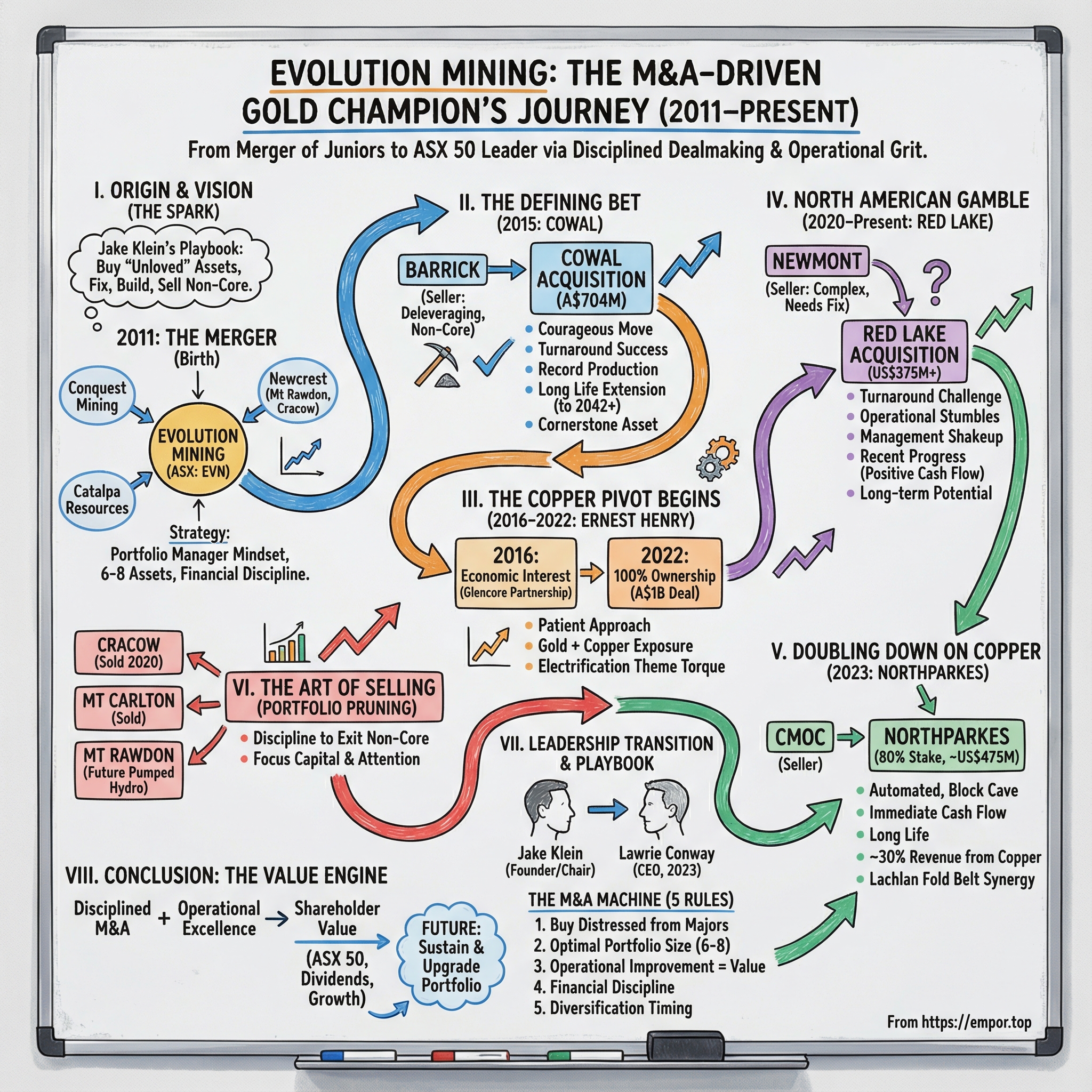

On a crisp June morning in 2025, Evolution Mining cracked the top table of Australian markets. It was added to the S&P/ASX 50, taking the spot of Pilbara Minerals, a lithium darling that had slid with the cycle. The change took effect on June 23, 2025—and for a company that began as a merger of two junior miners just fourteen years earlier, it felt like a kind of corporate alchemy.

By June 2025, Evolution’s market capitalization sat at around $18 billion. In that same span, it had climbed from “promising mid-tier” to Australia’s second-largest gold producer, behind only Newcrest Mining. This wasn’t a story of one lucky drill hole. It was a story of construction—built through a sequence of big, opinionated decisions.

So the driving question of this narrative is simple: how did a merger of two juniors become Australia’s second-largest gold miner in just over a decade?

The answer is a repeatable playbook. Serial M&A, yes—but with a very specific flavor: buying assets that global majors no longer had the patience, balance sheet, or strategic focus to nurture. Then doing the unglamorous work—investing, optimizing, extending mine life, and constantly upgrading the portfolio. And behind it all was the vision of one South African-born accountant who never studied geology, yet became one of Australia’s most effective mining dealmakers: Jake Klein.

Evolution was formed in 2011 via the merger of Conquest Mining and Catalpa Resources, alongside the purchase of Newcrest Mining’s Mt Rawdon and Cracow mines. From the beginning, the company behaved less like a single-mine operator and more like a portfolio manager: add quality, cut what doesn’t earn its keep.

The milestones came fast. Cowal and Mungari arrived in 2015. An initial interest in Glencore’s Ernest Henry followed in 2016. Then Red Lake in Canada in 2020. The rest of Ernest Henry in 2022. And an 80% stake in Northparkes in December 2023. Each deal carried the same signature: disciplined timing, deep due diligence, and the confidence to move when a seller had other priorities. By the end of December 2024, Evolution had roughly 15 years of gold reserves.

What makes Evolution such a useful case study is that it runs against the stereotype of gold mining as a graveyard of shareholder value—where acquisitions are mistimed, costs blow out, and reserves quietly evaporate. Evolution’s version has been steadier: grow through assets with expansion potential, keep a close grip on costs, and return cash to shareholders, including 25 consecutive dividends.

But it hasn’t been frictionless. The Red Lake acquisition tested whether the company could actually execute a turnaround, not just buy one. The pivot toward copper—now roughly 30% of revenue—raises a deeper question about what Evolution wants to be. And the leadership handoff from founder Jake Klein to CEO Lawrie Conway marks a new chapter: the moment a founder-led culture either becomes a durable institution, or starts to drift.

II. The Jake Klein Origin Story: From South Africa to Sino Gold

Before there was Evolution Mining, there was Jake Klein: a young South African-trained accountant who arrived in Australia with $1,000 in his pocket—and no obvious reason to end up running one of the country’s most formidable gold companies.

He started in Cape Town, taking the sensible route: accounting, the reliable ladder into finance and professional life. But as South Africa’s economic and political environment shifted in the early 1990s, Klein made the decision that set everything else in motion. He left for Australia.

In Sydney, he landed in the world of corporate finance. Prior to joining Sino Gold (and its predecessor) in 1995, Mr Klein was employed at Macquarie Bank and PwC. Macquarie, in particular, was a finishing school for ambitious dealmakers—fast-moving, opportunistic, and comfortable operating where the map still had blank spots.

One of those blank spots, at least for Australian investors at the time, was China.

Klein later described his entry into mining as a case of being in the right place at the right time—what he called “the intersection of good luck and good fortune.” While working at Macquarie in 1993, a strange opportunity surfaced: a “look see” trip to China.

“An opportunity came up to go off to China on a look see visit and at that time China wasn't the order of the day,” Klein said. “It was a byline rather than a headline, but we went to China and I guess that changed my life.”

To most young bankers, it would’ve sounded like a career detour. To Klein, it sounded like a door.

“We were crazy enough to think that a couple of Macquarie bankers, who knew nothing about China or mining, could actually build mines in remote parts of China,” he recalled.

That sentence contains the seed of the Evolution story. Not technical expertise. Not a lifelong obsession with geology. Something more useful in business: the willingness to step into unfamiliar territory and learn faster than everyone else.

In 1995, Klein moved from banking into the industry itself, joining what would become Sino Gold Mining. The premise was ambitious: build and operate gold mines in China as a foreign-backed group, in a sector that was politically sensitive and operationally complex—where language, culture, and local relationships weren’t “nice-to-haves,” they were survival.

Klein ultimately became President and CEO of Sino Gold, and under his leadership it grew into the largest foreign participant in the Chinese gold industry. Sino Gold listed on the ASX in 2002 with a market capitalisation of A$100 million. By late 2009 it was acquired by Eldorado Gold Corporation for more than A$2 billion. Along the way, it became an ASX/S&P 100 company, operating two award-winning gold mines and engaging more than 2,000 employees and contractors in China.

It’s tempting to treat that arc as a clean “100 million to 2 billion” victory lap. But the more important takeaway wasn’t the exit multiple—it was the education. Sino Gold was a real-world apprenticeship in how to build a mining company: how to earn trust in unfamiliar jurisdictions, how to scale operations, how to use acquisitions intelligently, and how to recognize the moment when selling is the best move.

Klein, characteristically, credited timing as much as skill.

“We were lucky,” he said. “China obviously emerged as being front and centre of global business, so we used to get meetings with investors more because they were interested in learning about China than they wanted to know about a relatively small gold company in China. So our exposure was amplified… China obviously became the headline act and also the largest gold producer.”

Sure. China became the headline. But Klein had already positioned himself, and his company, to be part of the story—when most people still thought it was footnotes.

By late 2009, Sino Gold had been sold. Klein had capital, a reputation, and a familiar entrepreneur’s question in front of him: what do you build next?

The answer, soon enough, would start with a small Australian gold company called Conquest Mining—and a plan to apply everything he’d learned, this time in his adopted home market.

III. The 2011 Merger of Equals: Birth of Evolution Mining

In 2010 and 2011, Australian gold was a crowded middle. There were plenty of small miners, many of them effectively single-asset businesses—too small to ride out commodity cycles comfortably, and too underpowered to fund serious, sustained exploration. At the top sat the majors—Newcrest, Barrick’s Australian operations, Newmont—focused on bigger, cleaner priorities. In between was a gap: good assets that weren’t getting the attention they deserved. Jake Klein recognized that gap as opportunity.

Evolution was created to fill it.

In late 2011, Catalpa Resources and Conquest Mining merged, and at the same time the new company bought Newcrest Mining’s interests in the Cracow and Mt Rawdon gold mines in Queensland. Overnight, the combined group had real operating weight. Catalpa contributed the Edna May mine in Western Australia’s Goldfields. Conquest brought the Mt Carlton project and the Panjingo gold mine in Queensland. And the Newcrest package added established production at Cracow and Mt Rawdon—exactly the kind of cash-generating base a new portfolio company needs.

Klein stepped in as Executive Chairman in October 2011, coming over from his role as Executive Chairman of Conquest. Just as important as the title was what he represented: a leader who’d already built a gold company to scale and sold it for a major outcome. That track record brought credibility to a deal that, on paper, could have looked like just another junior merger.

A month later, in November 2011, the rebrand made the strategy explicit. Catalpa Resources changed its name to Evolution Mining Limited. The company itself had been incorporated in 1998 and was based in Sydney, but the new name carried a different message: this wasn’t meant to be a static collection of mines. It was meant to change, upgrade, and grow.

The first moves supported that promise. As part of the formation, Evolution secured a full stake in Mt Rawdon and a 70% interest in Cracow, adding meaningful production right out of the gate and pushing the company quickly into the ranks of Australia’s larger gold producers.

Klein also laid out a simple operating doctrine that would become Evolution’s signature. In his view, the sweet spot for a mid-tier miner was a portfolio of six to seven assets—enough to diversify risk and fund growth internally, without becoming so sprawling that management attention gets diluted. The point wasn’t size for its own sake. It was self-sufficiency: the ability to reinvest and do deals without constantly going back to shareholders for capital.

The early execution came quickly. In 2012, Evolution entered the ASX 200. In 2013, Mt Carlton produced its first concentrate. And through those formative years, the company focused on proving it could run what it bought—tightening operations, improving performance, and building the credibility that would matter when the next, much larger opportunities appeared.

Around Klein, a core team began to take shape—most notably Lawrie Conway, who joined as a non-executive director in November 2011 and later became CFO. As Evolution would later put it, “Lawrie has played a key role in Evolution's growth and development since its formation, initially as a non-executive director from November 2011 and later as the chief financial officer and finance director since August 2014.” Conway’s financial discipline paired naturally with Klein’s deal instincts: one pushing for opportunity, the other ensuring the balance sheet stayed strong enough to keep playing.

By the end of 2011, Evolution wasn’t just a new name on the board. It was a company designed for a specific game: assemble a portfolio, improve it relentlessly, and keep enough flexibility to move when someone else—usually a bigger, distracted seller—decided an asset was no longer worth their time.

IV. The Cowal Acquisition: Evolution's Defining Bet (2015)

If the 2011 merger was Evolution Mining’s birth, the 2015 acquisition of Cowal was its coming-of-age. It was the moment Evolution stopped looking like a promising mid-tier and started behaving like a company that could take on the incumbents. And it happened because, in 2015, the world’s biggest miners were in no mood to hold onto anything that wasn’t central to their next plan.

Barrick Gold—then the world’s largest gold producer—was coming off the boom years with a balance sheet problem. Debt was high, investors wanted it lower, and Barrick’s Australian footprint sat well outside its preferred focus in the Americas. So Cowal, a quality New South Wales mine, suddenly became “non-core.” Barrick agreed to sell 100 percent of the operation to Evolution for US$550 million in cash at closing. Co-President Kelvin Dushnisky framed it plainly: the sale would help hit Barrick’s debt reduction targets and tighten its geographic footprint.

For Evolution, that seller mindset was the opening.

On 25 May 2015, Evolution announced it had successfully acquired Cowal for A$704 million. The mine sits about 40 kilometres north-east of West Wyalong, in central New South Wales, and at the time was producing roughly 230,000 to 260,000 ounces of gold a year, supported by 1.6 million ounces of Proven and Probable Reserves.

The financing was designed to keep the company moving, not wobbling. Evolution raised A$248 million through a fully underwritten pro-rata entitlement offer and lined up around A$700 million in debt facilities to help fund the purchase. Management believed Cowal could be run at more than 250,000 ounces a year, and they were just as excited about what surrounded the mine: a vast tenement package—around 6,000 square kilometres—that hadn’t been pushed as hard as it could be.

And Evolution didn’t stop at Cowal.

A month earlier, in April 2015, it had completed the buyout of La Mancha Resources’ Australian operations, valued at A$300 million. That deal brought in the Frog’s Leg and White Foil mines and, critically, the nearby processing plant at Mungari. Two major acquisitions, back-to-back, wasn’t just ambition—it was a proof point. Evolution could execute and it could fund.

As Evolution later put it: “Our first significant transaction was to buy the Cowal operation from Barrick in 2015. Cowal was a high-quality asset in the Barrick portfolio but they had made a strategic decision to exit Australia and it was a courageous acquisition for us.”

“Courageous” is doing real work in that sentence. Cowal was huge relative to Evolution’s existing base. It would quickly become the company’s largest asset and a dominant contributor to production. If something went wrong—if costs blew out, if reserves disappointed, if operations stumbled—the whole company would feel it.

But Klein believed Barrick’s priorities had created a mispricing. He saw an asset that wasn’t broken, just underloved: a mine with real exploration upside that a global major, distracted by bigger problems, wasn’t going to patiently develop.

Over time, Evolution said it achieved organic growth at Cowal of 6.2 million ounces in Mineral Resources and 3.0 million ounces in Ore Reserves since acquisition (net of mining depletion of 1.7 million ounces). In other words, Cowal didn’t just keep producing—it kept getting bigger under Evolution’s stewardship.

The numbers that mattered most were the ones that proved the thesis. Since 2015, Cowal contributed more than A$1.62 billion in net cash flow to Evolution. The mine paid for itself and then some—and the life of the asset stretched far beyond what Cowal looked like on Barrick’s sell sheet.

By 2025, Cowal had a permitted life out to 2042, after approvals to continue open pit mining and develop additional open pits. The operation also remained a serious, scaled industrial site: a large tenement footprint and a workforce of around 1,200 people, including about 480 employees.

That year, Evolution secured board approval to extend Cowal to 2042. The company said the extension would generate a 71% rate of return at the current spot gold price, or 34% at A$3,300 per ounce. The plan included developing the existing E42 pit and three new satellite pits, adding about two million ounces of production over the next decade.

In FY25, Cowal delivered record annual gold production, cementing its status as Evolution’s premier asset. What Barrick had labeled non-core became Evolution’s cornerstone—proof of what this company does better than most: buy a good asset when the seller can’t—or won’t—give it the attention it deserves, then do the work to make it great.

V. Ernest Henry: The Copper Pivot Begins (2016-2022)

Cowal proved Evolution could buy a big, high-quality asset and make it better. The next big swing did something else: it changed what Evolution was. Ernest Henry didn’t just add another mine to the portfolio—it introduced copper, and with it a second engine for the business.

What’s striking is how Evolution got there. The Ernest Henry story played out in two acts over roughly six years, and it showed a different kind of advantage: patience, creativity in deal structure, and the ability to turn a partnership into a full takeover when the timing was right.

Evolution’s first step came in 2016, when it struck an A$880 million deal with Glencore. Instead of buying the mine outright, Evolution bought an economic interest in the production stream: 100% of the gold, and 30% of the copper (and silver), over an agreed reserve life of around 11 years, plus 49% of production from new exploration from 2027 onwards.

In practical terms, the structure meant Evolution wasn’t running Ernest Henry—but it was meaningfully exposed to its output. The interest was held through joint ventures that delivered 100% of future gold and 30% of future copper and silver produced within an agreed life-of-mine area, with Evolution paying 30% of the operating costs and capital.

That unusual structure made sense when you looked at the seller. In 2016, Glencore was dealing with balance sheet pressure and needed cash, but didn’t want to permanently part with a core, long-life copper asset. Ernest Henry became a compromise: Glencore kept operational control and most of the copper exposure, while Evolution wrote the check and took the gold-heavy slice of the upside.

Just as importantly, the deal created something Evolution values enormously: time inside the tent. Over the next five years, Evolution worked alongside Glencore at Ernest Henry. That partnership gave Evolution’s team detailed knowledge of the operation—how it ran, what it could become, where the risks were, and where the mine still had room to grow.

Then, in late 2021, the door opened.

Evolution announced it would acquire full ownership of Ernest Henry Mining in Queensland from Glencore in a A$1 billion deal. Glencore would receive A$800 million on closing, with a further A$200 million payable 12 months later. When the transaction completed in January 2022, Evolution moved from “economic participant” to outright owner and operator.

The agreements between the two companies didn’t end there. Evolution also entered into an offtake agreement under which Glencore would purchase 100% of the copper concentrate produced at the mine—another example of how Evolution was comfortable keeping counterparties close, even after taking control.

Jake Klein summed up the arc in a way that sounded casual, but wasn’t: “We have long coveted to own Ernest Henry. It is a world-class asset, in Australia, and one which we know extremely well due to our successful investment in the asset in 2016 and we are proud that it will once again be 100%-Australian owned. The acquisition is consistent with our strategy, materially improves the quality of our portfolio, and delivers both strong cash flow and mine life extension opportunities.”

On the ground, Ernest Henry is a large-scale copper-gold mine about 38 kilometres north-east of Cloncurry. It started life as an open pit in 1998, then transitioned to underground mining in 2011. The current underground operation uses sub-level caving, a low-cost and highly efficient extraction method well-suited to the deposit.

Strategically, Ernest Henry did for Evolution what Cowal couldn’t. It added meaningful copper exposure just as the broader market was waking up to copper’s role in electrification—electric vehicles, grid upgrades, renewables, the whole energy transition buildout. Gold gave Evolution defensiveness; copper gave it torque to a long-term demand story.

By 2022, Evolution wasn’t just assembling a better gold portfolio. It was deliberately becoming a gold-copper producer—with a more resilient mix, and a bigger set of options for what to buy next.

VI. The Red Lake Gamble: Expanding to North America (2020-Present)

Every great acquisition story eventually meets its stress test. For Evolution, that test was Red Lake: a legendary Canadian gold camp with world-class geology—and an operation that refused to cooperate on schedule. It was Evolution’s first major step outside Australia, and for a while it looked like the kind of deal that can humble even the best capital allocators.

Evolution telegraphed the move in November 2019, when it announced a bid for Newmont’s Campbell Red Lake Mine. The pitch was straightforward: Red Lake didn’t need a miracle, it needed attention. Evolution promised a “Turnaround Plan,” arguing it had “identified a range of improvement opportunities to reinvigorate the Red Lake Gold Complex with the objective of reducing costs, increasing production and extending mine life,” as Jake Klein put it.

On paper, the logic was hard to ignore. Red Lake sits in one of North America’s highest-grade gold districts, with a century-long history and a deep geological inventory. Evolution paid US$375 million upfront, with another US$100 million contingent on discovering additional resources. Then, in 2021, it doubled down by buying the adjacent Battle North Gold property holdings for CAD$343 million, tightening its grip on the broader camp.

Klein framed it the way Evolution always framed these moves: not as a trophy purchase, but as a fix-and-build opportunity. “Evolution Mining is looking for great turnaround opportunities like in Red Lake, which fits firmly in this category,” he told the Denver Gold Forum in September 2021. He also emphasized the setting: Canada’s stability, skills, and rule of law fit Evolution’s preference for Tier 1 jurisdictions.

But Red Lake reminded everyone that “turnaround” is a verb, not a slogan. After taking over from Newmont in 2020, Evolution struggled to get the complex producing consistently. Operating in remote northwestern Ontario brought its own constraints, and the mine faced ongoing challenges, including seismic-related issues that made reliable execution difficult.

The biggest near-term bet was development of the Upper Campbell Mine, the next major high-grade ore body. That development ran slower than expected, and Evolution responded the way operators do when a plan is slipping: it changed the people and the rhythm. A management shakeup followed, and COO Bob Fulker spent five months on site to stabilize the operation.

By April 2023, CEO Lawrie Conway was openly signaling that Red Lake would not be rewarded until it proved it could perform. “Red Lake’s gotta earn the right to get the upgrade,” he told analysts.

That line captured the new posture: less grand ambition, more fundamentals. Conway laid out a phased path—first make the mine reliable, then grow it. “The first step will be to reach 150,000 oz/y, with 2024 guidance placed at 125,000 oz/y to 145,000 oz/y,” he said. “Once we achieve consistency and reliability in the operation, we will then consider options to increase production and lower overall unit operating costs.”

Internally, that meant narrowing the mission. The priority became simple: generate positive cash flow, with margin on every ounce, and rebuild confidence in the operating system. Evolution argued that taking the pressure off the workforce—focusing on repeatability before expansion—helped unlock efficiency and created a platform for improvement.

By 2024, the effort started to show. The first half of the year brought major operational changes, and by Q4 2024 the site notched its second consecutive quarter of positive cash flow.

And then the story began to turn. In the quarter ending June 2025, Red Lake delivered its highest quarterly ore mined under Evolution ownership, at 254,000 tonnes. By Q3 2025, the mine—once viewed as a cash drain—was generating meaningful cash, with cash flow up 127% to $90 million.

Evolution’s longer-term ambition for Red Lake stayed intact: a comprehensive operational transformation designed to restore the complex to a premier Canadian gold mine, targeting annual production of more than 200,000 ounces and pushing mine life out to 2040, with room to extend further.

Conway also pointed to something Evolution was quietly learning in real time: how to operate, credibly, as a foreign owner in a tight-knit mining community. “We are now four and a half years into our ownership of Red Lake, and we have found working with the local community and various governmental organizations to be smooth and reliable,” he said. “We have learned a lot about how to operate in the region, and similarly, people have learned how Evolution Mining operates, especially from a safety and environmental standpoint.”

Red Lake is the clearest illustration of both sides of Evolution’s strategy. Buying complex assets from majors can create enormous value—but only if you can do the hard part after the announcement: stabilize the operation, earn back reliability, and rebuild the mine into what the geology always promised. For years, the jury was out. By 2025, the early signs suggested Evolution may yet get the verdict it wanted.

VII. Northparkes: Doubling Down on Copper (2023)

If Ernest Henry was Evolution’s first real step into copper, Northparkes was the moment the company stopped dabbling and started committing. Announced in December 2023, it was Evolution’s biggest deal since taking full ownership of Ernest Henry—and it pushed copper to roughly 30% of revenue.

Evolution entered a binding agreement to buy an 80% interest in the Northparkes copper-gold mine in New South Wales from CMOC Group for total cash consideration of up to US$475 million. The remaining 20% stayed with long-time partner Sumitomo Metal Mining and Sumitomo Corporation, who retained their stake in the joint venture.

Jake Klein’s pitch was as direct as it gets in mining M&A: this was an asset that paid you from day one, with a long runway. “Northparkes is a day one cashflow producing asset with a 30-year mine life, considerable upside and a well-established team that has a great track record and technical experience at the operation,” he said. Northparkes sits about 27 kilometres from Parkes in central-west New South Wales. It has been operating since the mid-1990s, and it made Australian mining history as the first local operation to use block cave mining.

The deal terms also showed the Evolution style: disciplined pricing, and a willingness to share the cycle. Evolution agreed to pay US$400 million in cash plus a copper price-linked contingent amount of up to US$75 million. If copper prices strengthened, CMOC shared in the upside. If they didn’t, Evolution wasn’t overpaying on day one.

Operationally, Northparkes was exactly the kind of modern, scalable mine Evolution wanted more of. The underground is highly automated, with the E48 block cave reaching 100% mining automation back in 2015. The transaction was funded through a newly announced A$525 million fully underwritten institutional placement, alongside a new A$200 million, five-year term debt facility.

Lawrie Conway anchored the strategic case in geology and track record. “Positioned in the Lachlan Fold Belt, one of Australia’s most prospective Copper-Gold belts, Northparkes has a long history of Ore Reserve replenishment and growth,” he said. Since 1994, reserves had grown materially, and by the time of the deal the operation had an ore reserve of 101 million tonnes.

In many ways, Northparkes felt like a familiar Evolution move—just in copper. It’s a long-established mine with a low-cost profile, built around highly mechanized bulk caving methods underground. The broader asset has a long history too: discovered in 1976, operated by Rio Tinto from 2000 to 2013, then acquired by CMOC in December 2013, with Sumitomo holding the other 20%.

And then there’s the simplest synergy of all: proximity. Northparkes is in the same mineral-rich Lachlan Fold Belt as Cowal, Evolution’s flagship gold mine. That closeness creates obvious potential for shared services, sharper management focus, and logistical efficiencies—without needing to force an integration story across states or countries.

Evolution also pointed to organic growth. Northparkes had meaningful expansion potential, including a possible mine life extension out to 2054. Following completion of the E48 Level 2 Sublevel Cave pre-feasibility study, the project moved into execution, with production targeted for the first half of FY26.

Zooming out, Northparkes also fit a broader market reality Evolution clearly liked. Copper demand is pulled forward by electrification—grids, renewables, electric vehicles—while supply stays constrained by long permitting timelines and declining grades. At the same time, there are fewer pure-play copper options for investors, especially after Oz Minerals was acquired by BHP for about $10 billion. For Evolution shareholders, more copper exposure meant participation in that structural theme—without giving up the gold foundation the company was built on.

VIII. Portfolio Management: The Art of Knowing When to Sell

Evolution’s story isn’t just a highlight reel of acquisitions. The other half of the playbook—the quieter half—is knowing when to let go.

Klein and Conway get plenty of credit for buying well. But one of Evolution’s real advantages has been its willingness to sell mines that no longer deserve a place in the portfolio. In mining, that’s rarer than it sounds. Assets have a way of sticking around long after their best years, defended for sentimental reasons, sunk costs, or the hope that the next quarter will look better.

From the beginning, Evolution was built to act more like a portfolio manager than a single-mine operator. After forming in 2011 through the Conquest–Catalpa merger and the purchase of Newcrest Mining’s Mt Rawdon and Cracow mines, Evolution kept adding operations—and then steadily pruning the ones that were higher-cost, shorter-life, or simply less strategic. Cracow, for example, was sold in 2020.

The guiding idea is consistent: prioritize assets that can generate superior returns across the commodity price cycle. If a mine can’t clear Evolution’s return hurdles, or if it lacks the exploration upside to extend its life in a meaningful way, it shouldn’t consume management time or capital—no matter how familiar it is.

That’s how Evolution approached Mt Carlton, a mine from the original portfolio, which it divested to Navarre Minerals for around $90 million. The Kundana gold operations were sold in a separate transaction. Different assets, same conclusion: someone else could run them better, or value them more, than Evolution could within its own system.

Mt Rawdon shows what this mindset looks like when a mine reaches the end of its natural life. The open pit operation in Queensland is approaching closure, and Evolution hasn’t tried to force a heroic final chapter. Instead, it commenced a feasibility study to transform the site from a gold mine nearing the end of its mine life into a large-scale, long-life renewable energy generation and storage asset—a pumped hydro power station. The plan is to close Mt Rawdon in 2028 and then build a renewable energy storage system.

All of this ladders up to Klein’s portfolio philosophy: keep the company at a size where it’s diversified, self-funding, and focused. Evolution’s target is a portfolio of up to eight assets in Tier 1 mining jurisdictions, with six to eight operations seen as the sweet spot. Too few mines creates concentration risk. Too many spreads leadership attention and corporate overhead thin, turning the company into a loose federation of subscale problems.

So Evolution keeps doing what it has always done: doubling down on the best assets, and exiting the ones that don’t make the cut, as it works toward its stated goal of owning six to eight top-quality mines.

That willingness to sell—even when it’s uncomfortable, even when an asset is still producing—helps explain why Evolution’s portfolio has improved over time. The company treats its mines as a living system that needs constant upgrading, not a permanent collection that must be defended at all costs.

IX. Leadership Transition: From Jake Klein to Lawrie Conway

Every founder-led company eventually runs into the same question: what happens when the person who built it stops running it?

At Evolution, that handoff started in September 2022 and became official on 1 January 2023, when Lawrie Conway was appointed Chief Executive Officer and Managing Director—the first time Evolution had ever created that role. Up to that point, the company had been led in a more founder-centric structure, with Jake Klein as Executive Chair.

The announcement was straightforward: Evolution’s Finance Director and Chief Financial Officer, Lawrie Conway, would step up as CEO and Managing Director, effective 1 January 2023.

Klein didn’t step away overnight. He remained Executive Chair and signed a contract extension through at least the end of 2024. To shareholders, he framed the change as a natural evolution of an organization that had outgrown its original operating model.

“Evolution has transformed its portfolio of operations over the past few years and given the structure and scale of the business, now is the right time to appoint a CEO and Conway is the ideal candidate,” Klein said. “The creation of this role will allow us to continue to deliver on both Evolution’s strategic ambitions and operational performance and establishes the organisational structure for the next chapter of growth and development. Conway will bring a necessary whole-of-business focus as we progress the implementation of our vision of building Evolution into a premier, global gold company.”

Conway wasn’t an outsider parachuted in. He’d been part of the engine room since the beginning—serving as Finance Director and CFO since 2011—and brought more than 30 years of mining and metals experience, including senior roles at Newcrest Mining. In other words, the board wasn’t choosing “new leadership.” It was choosing continuity, with a different center of gravity.

“It is a real privilege to be appointed to the role of Chief Executive Officer and Managing Director as Evolution moves into the next phase of our journey to be a premier, global gold company,” Conway said. “Evolution has a highly talented workforce committed to safely delivering our plans from a high-quality portfolio of assets.”

The bigger symbolic step came later. Effective 1 July 2025, Klein transitioned to Non-Executive Chair. That shift—Executive Chair to Non-Executive Chair—was the clearest signal yet that Evolution was becoming an institution rather than a founder-led project. Klein remained involved at the strategic level, but the operating cadence and day-to-day decisions sat with Conway and the leadership team. As of 1 July 2025, Klein also became Executive Chair of Federation Mining.

Founder-to-professional-CEO transitions are inherently risky. Founders carry relationships, instincts, and historical context that are hard to document, let alone replace. Evolution’s approach tried to reduce that risk by choosing a successor who already had deep internal credibility—and by keeping Klein close enough to provide continuity without shadow-running the company.

That broader bench matters too. Evolution’s COO, Mr O’Neill, previously served as Australian Regional Lead/COO for Glencore’s Copper and Zinc businesses, with accountability for Ernest Henry from the time Evolution acquired its economic interest in 2016 through to Evolution’s move to 100% ownership in January 2022. He joined Xstrata/Glencore in 2004, and after leaving Glencore in 2023 he ran his own consulting business, including work supporting Evolution on the integration of Northparkes.

Evolution also emphasized alignment: meaningful equity ownership, performance-based incentives, and a track record of capital allocation that investors have come to trust.

And by the numbers—at least so far—the transition hasn’t slowed the machine. Evolution’s FY2025 results under Conway delivered record production, record profits, and record cash flows. Northparkes was integrated, portfolio optimization continued, and the strategy still read like Evolution: buy well, operate better, and keep upgrading the collection of assets.

Klein built the dealmaking culture. Conway is running the operating system. For a company like Evolution—no longer a scrappy consolidator, but not yet a lumbering major—that pairing is exactly what the next chapter demands.

X. Playbook: The Evolution Mining M&A Machine

Fourteen years in—and after a long string of deals big enough to break most mid-tiers—Evolution’s acquisition playbook is no longer implicit. It’s repeatable. And it helps explain why this company has managed to create value in a sector where M&A often destroys it.

Five principles show up again and again.

Lesson 1: Buy Distressed Assets from Majors Under Pressure

The pattern is almost too clean. Cowal came from Barrick when Barrick was deleveraging. Evolution’s first bite of Ernest Henry came from Glencore when Glencore’s balance sheet was under strain. Red Lake came from Newmont in the wake of the Goldcorp merger, when the combined business needed to simplify an unwieldy portfolio. Northparkes came from CMOC as it pursued other priorities.

In every case, Evolution wasn’t buying “bad mines.” It was buying mines that had become inconvenient. The seller’s motivation wasn’t geology or long-term potential—it was debt, strategy, geography, or focus. That’s where pricing gets interesting.

But you only get those moments if you’re ready for them. This approach takes patience, constant awareness of what the majors are doing, and the ability to move fast when a window opens. Evolution also plays the long game in relationship-building. The five-year Ernest Henry partnership before the full acquisition is the clearest example: get close, learn the asset, and be the obvious buyer when the opportunity finally arrives.

Lesson 2: The Optimal Portfolio Size Philosophy

Klein has long argued that the sweet spot for a globally competitive mid-tier is a portfolio of six to eight assets. That number is small enough to stay focused, and large enough to diversify risk and fund growth internally.

This idea quietly governs everything Evolution does. It shapes how aggressive the company is on acquisitions, and it creates the internal permission structure to divest. Too few mines and you’re hostage to one operation. Too many and you’re a distracted conglomerate of problems. Six to eight keeps the machine self-funding without constantly going back to shareholders.

Lesson 3: Operational Improvement as Value Creation

Evolution’s edge isn’t just buying. It’s what happens after closing.

The company’s operating model is built around continuous improvement: tightening mining and processing methods, bringing in new technology where it matters, and pushing exploration hard enough to extend mine life. Evolution doesn’t buy an asset and run it as-is. It tries to make the mine bigger, longer-life, and more efficient than it was under the previous owner.

Cowal is the clearest illustration: a mine that Barrick was willing to walk away from became Evolution’s cornerstone because Evolution kept investing, kept exploring, and kept upgrading what the asset could be.

Lesson 4: Maintain Financial Discipline During Deals

Evolution’s financial discipline is less exciting to talk about than the deals themselves, but it’s what makes the deals possible.

The company has built a reputation for funding acquisitions in a way that keeps the balance sheet intact—using a mix of debt, equity, and operating cash flow rather than betting the company on leverage. That discipline supports the dividend, helps protect the business in down cycles, and—most importantly—keeps Evolution in position to act when distressed opportunities emerge.

This is the part many acquisitive miners get wrong. Evolution has been determined not to.

Lesson 5: Diversification Timing Matters

The copper pivot worked not just because copper is attractive, but because the timing lined up.

Ernest Henry and Northparkes increased Evolution’s copper exposure as the electrification narrative accelerated—grids, renewables, electric vehicles—all pulling forward long-term demand. Copper brought a growth tailwind to complement gold’s defensive, safe-haven role. Plenty of miners talk about diversification. Evolution’s advantage was moving when those assets were available, and when the strategic case was strengthening, not fading.

XI. Porter's Five Forces & Hamilton's 7 Powers Analysis

To see why Evolution has been able to keep compounding through a brutal, cyclical industry, it helps to zoom out and look at the structure of the game it’s playing—and the advantages it’s built inside that structure.

Porter's Five Forces

Threat of New Entrants: LOW

Gold mining is one of the least forgiving businesses to “just enter.” Building a mine takes enormous upfront capital. Permitting and approvals can drag on for years. And even if you can clear those hurdles, the hardest part is the thing you can’t manufacture: a high-quality deposit in a top-tier jurisdiction.

That’s the quiet moat around incumbents like Evolution. Over the last decade-plus, it assembled a portfolio that would take a new entrant years—likely decades—to replicate: Cowal and Mungari in 2015, the initial Ernest Henry interest in 2016, Red Lake in 2020, full Ernest Henry ownership in 2022, and Northparkes in late 2023. By the end of December 2024, Evolution also had roughly 15 years of gold reserves—time and optionality that newcomers simply don’t have.

Bargaining Power of Suppliers: MODERATE

A lot of what mines buy—equipment, fuel, explosives—is broadly available, which keeps supplier power in check. The pinch point is people. Specialized roles are hard to staff, and remote sites can turn “labor availability” into a real constraint.

Evolution’s edge here comes from operating at scale across multiple sites in multiple regions. That gives it more leverage in contracting, more flexibility to allocate talent, and less exposure to any single local labor squeeze.

Bargaining Power of Buyers: LOW

For both gold and copper, prices are set by global markets. Evolution doesn’t “negotiate” the gold price; it receives it.

At Ernest Henry, Glencore offtakes 100% of the copper concentrate, but that doesn’t mean Glencore sets the price—this is primarily a commercial and processing relationship, not a monopoly on what the product is worth. And for gold, Evolution can sell into deep, liquid markets through multiple channels.

Threat of Substitutes: LOW (Gold) / MODERATE (Copper)

Gold’s role is unusual: it’s a commodity, but also a monetary asset. Investors, central banks, and individuals use it as a store of value, and there isn’t a true substitute with the same combination of liquidity and long-established trust.

Copper is different. In some applications it can be substituted—aluminum is the classic example—but copper’s conductivity makes it hard to replace in many parts of modern electrification. Substitution risk exists, but it has limits.

Industry Rivalry: HIGH

This is where mining gets intense. There are only so many quality assets, and everyone wants them. Evolution competes directly with other Australian gold players like Northern Star, as well as global majors like Newmont, for acquisitions, talent, and investor attention.

The prize is not volume—it’s quality. Long-life, low-cost, expandable operations in stable jurisdictions. Those rarely come up for sale, and when they do, the process is competitive by default.

Hamilton's 7 Powers Analysis

1. Scale Economies: MODERATE

Evolution isn’t a mega-major, but it’s big enough to benefit from being a multi-asset operator. It runs five wholly owned mines—Cowal in New South Wales; Ernest Henry and Mt Rawdon in Queensland; Mungari in Western Australia; and Red Lake in Ontario, Canada—plus an 80% share of Northparkes in New South Wales. That portfolio allows corporate overhead, technical expertise, and systems to be spread across more production, lowering per-unit costs versus smaller peers.

2. Network Effects: WEAK

There’s no flywheel where each additional ounce makes the next ounce more valuable. Gold mining doesn’t get stronger because other people mine gold.

3. Counter-Positioning: MODERATE

Evolution’s acquisition strategy—buying “unloved” assets from majors under pressure—works partly because the majors often can’t pursue it. Large miners are constrained by scale, portfolio optics, and shareholder expectations. They tend to need bigger deals, clearer narratives, and less operational complexity.

That leaves room for a disciplined mid-tier to win. Not by doing what the majors do, but by doing what they structurally won’t.

4. Switching Costs: WEAK

For customers, an ounce of gold is an ounce of gold. The same is largely true for copper concentrate. Buyers can switch easily.

5. Branding: WEAK

Evolution’s name can help with recruiting and investor trust, but it won’t earn a premium price for its metal. This is a commodity business.

6. Cornered Resource: MODERATE

Where Evolution does have something scarce is in its control of ground—especially the large tenement package around Cowal. Those exploration and mining rights are, by definition, exclusive. They create future options: extensions, satellite pits, and discoveries that competitors simply can’t access.

7. Process Power: MODERATE

If Evolution has a real, repeatable advantage, it’s here. Over 14 years, it built a muscle for doing the hard parts of mining M&A: developing relationships early, moving quickly when sellers are motivated, structuring deals creatively, and then doing the operational work after closing.

That’s not a single “secret.” It’s accumulated organizational learning. And in mining, where integration mistakes are expensive and turnarounds are slow, that kind of process power is difficult to copy fast.

XII. FY2025 Results and Financial Position

When Evolution reported its FY2025 results in August 2025, it wasn’t just a “solid year.” It was the kind of scoreboard that tells you the strategy is working.

Statutory net profit after tax more than doubled to a record $926.2 million for the year ended 30 June 2025, up from $422.3 million the year before. Underlying net profit after tax also hit a new high, rising to $958.2 million from $481.8 million.

Production backed it up. Evolution delivered a record 750,512 ounces of gold, up 5% year-on-year. Cowal, Northparkes, and Red Lake each posted record annual gold output under Evolution’s ownership—a neat summary of the company’s identity: buy it, improve it, and make it outperform what it was.

The cash followed. Group cash flow reached $787.0 million, up 114%, while net mine cash flow rose to $1,035.4 million, up 78% from the prior year.

Pricing did plenty of the heavy lifting too. Total gold sales volumes increased 4%, and Evolution achieved a record realised gold price of $4,300 per ounce, up from $3,190 per ounce in FY2024—driving a sharp step up in revenue.

On costs, the picture was mixed depending on the measure cited. Evolution reported all-in sustaining costs of A$1,320 per ounce in FY25, and elsewhere disclosed AISC of A$1,653 per ounce, reflecting an increase year-on-year. Either way, the big story of FY25 wasn’t margin pressure—it was operating leverage: higher volumes, stronger pricing, and materially higher cash generation.

The balance sheet strengthened as well. Gearing fell to 15% from 25%, liquidity climbed to A$1.29 billion, and the company reaffirmed its investment-grade credit rating in July.

Copper is now a meaningful part of the narrative, not an add-on. Alongside the higher gold output, Evolution reported copper production up 12% to 76,261 tonnes.

And true to form, the company shared the upside. Evolution declared a final, fully franked FY25 dividend of 13.0 cents per share, totaling $260.3 million—its 25th consecutive dividend. The final dividend was also 160% higher than the prior year, lifting the total dividend payout to 160% of FY2024 levels.

For FY2026, Evolution held to its guidance: 710,000 to 780,000 ounces of gold and 70,000 to 80,000 tonnes of copper, with AISC expected in the range of A$1,720 per ounce to A$1,880 per ounce.

XIII. Bull Case vs. Bear Case

The Bull Case

The bull case for Evolution Mining is basically the argument that the flywheel is still spinning: strong commodities, a better portfolio than it had a decade ago, and enough balance-sheet room to keep making good decisions.

Structural Gold Tailwinds: Gold moved to record prices amid central bank buying, inflation anxiety, and geopolitical uncertainty. If prices stay elevated, Evolution benefits disproportionately: the costs of running mines don’t rise and fall in lockstep with the gold price, so higher realised prices can flow through to fatter margins.

Copper Optionality: Copper gives Evolution a second leg. The energy transition points to long-term demand for copper, and Evolution now has real exposure through Ernest Henry and Northparkes. As the company has framed it, “Our 25% revenue contribution from copper provides an effective hedge against gold price volatility, while still allowing shareholders to participate in gold’s upside potential.”

Organic Growth Pipeline: Evolution doesn’t need to “buy growth” every time it wants to get bigger. Cowal’s approved extension to 2042, the ongoing Red Lake transformation, and the Northparkes growth projects create a clear runway for production and cash flow without requiring another headline acquisition. That operating momentum was a major contributor to FY25’s record underlying net profit of $958 million.

Financial Flexibility: Evolution has made balance-sheet strength part of the strategy, keeping net debt-to-EBITDA below 1x even while it expanded. An investment-grade credit rating and substantial liquidity matter in a cyclical business: they let you keep investing through downturns, and they give you the option to act when the next distressed asset shows up.

Proven M&A Capability: Fourteen years of largely value-accretive dealmaking has earned management the benefit of the doubt. In a sector where acquisitions often go wrong, Evolution has built credibility that it can keep allocating capital sensibly.

The Bear Case

The bear case is the reminder that mining is still mining: costs creep, cycles turn, and execution is never guaranteed.

Cost Inflation: Mining has faced global cost inflation—energy, labor, contractors, consumables. Evolution’s all-in sustaining costs rose in FY25 (including AISC of A$1,653 per ounce, up 12%). If costs keep climbing faster than gold and copper prices, margins get squeezed.

Commodity Price Volatility: Today’s prices can make any operator look good. If gold and copper fall meaningfully from elevated levels, Evolution’s earnings power and valuation would come under pressure. And while copper diversification helps, it doesn’t remove the core reality: this is still a commodity-price-driven business.

Operational Execution Risk: Red Lake has already shown the limits of “turnaround” narratives. Evolution ultimately made progress there, but it took time, management attention, and real capital. Future improvement plans—whether at Red Lake or elsewhere—may not land on schedule, or at all.

Geological Risk: Mine life is never a given. It depends on converting resources into reserves and consistently replacing what gets mined through exploration success. Evolution has done this well historically, but geology doesn’t sign contracts.

Leadership Transition Risk: Jake Klein stepping back to Non-Executive Chair removes the founder from day-to-day control. The key question is whether the discipline, culture, and deal instinct he embedded are now institutional—something the company can keep repeating—or whether they were more dependent on one person than investors would like.

XIV. Key Performance Indicators for Investors

If you’re trying to follow Evolution quarter by quarter without getting lost in the noise, there are three indicators that tell you most of what you need to know about whether the machine is still working.

1. All-in Sustaining Cost (AISC) per Ounce

AISC is the closest thing mining has to a “true” cost of production. It rolls up mining and processing costs, sustaining capital, and the overhead required to keep the business running. In a gold company, the spread between AISC and the realised gold price is the engine of margins and cash flow.

For Evolution, watching where AISC lands versus its own guidance—and versus peers—gives you a quick read on operational execution. When costs are controlled, the company stays insulated across the cycle; when they drift, even a strong gold price can stop masking issues.

2. Net Debt to EBITDA

Evolution’s strategy depends on financial flexibility. A strong balance sheet is what lets it buy when others are selling—and keep investing when the cycle turns ugly.

That’s why net debt to EBITDA matters. Evolution has historically kept this below 1x. If leverage starts climbing meaningfully, it usually signals one of two things: a deal that’s stretching the balance sheet, or an operating portfolio that isn’t generating the cash it should.

3. Reserve Replacement Ratio

Mines are wasting assets unless you replace what you extract. Over the long run, a gold miner’s economics come down to one question: can it keep its reserve base healthy without overpaying for it?

Evolution’s record at Cowal is the clearest case study. Since acquiring the mine in 2015, it delivered organic growth of 6.2 million ounces in Mineral Resources and 3.0 million ounces in Ore Reserves (net of mining depletion of 1.7 million ounces). That’s what “extending mine life” looks like in practice.

As a rule of thumb, a reserve replacement ratio below 100% points to eventual decline. Sustained results above 100% suggest the opposite: longer mine lives and the possibility of future production growth.

XV. Conclusion: The Evolution Playbook

Evolution Mining’s fourteen-year run—from a merger of two junior miners to Australia’s second-largest gold producer—offers a lesson that travels well beyond mining. In an industry famous for burning capital, Evolution showed that disciplined M&A, executed patiently through a full commodity cycle, can create real shareholder value.

And the playbook isn’t mysterious. It’s just hard.

Buying “unloved” assets from majors under pressure takes patient capital, relationships built over years, and the internal muscle to do deep due diligence fast—then close when the window is open. Keeping the portfolio in the sweet spot means being as willing to sell as to buy. Operational improvement demands relentless reinvestment: exploration to extend mine life, technology to lift productivity, and people who can actually run complex sites. Financial discipline means walking away from deals that look exciting in the headline but threaten the balance sheet in the downside.

That’s what ultimately pushed Evolution into the ASX 50—the benchmark index for Australia’s largest, most liquid listed companies. It wasn’t one lucky year. It was a portfolio transformation built over multiple years, deal by deal, mine by mine.

Jake Klein arrived in Australia three decades ago with $1,000 in his pocket and no mining background. He stepped back from day-to-day leadership having helped build one of the country’s most successful gold companies—and a template for mid-tier mining M&A that others try to copy. Now the question is whether Evolution can keep doing what made it special under new leadership: stay disciplined when the cycle gets frothy, stay bold when the cycle turns ugly, and keep upgrading the portfolio without losing the culture that powered the first fourteen years.

CEO Lawrie Conway put it simply: “The record financial performance in FY25 was achieved through safely delivering to plan across all operations.”

Gold in the ground is finite. What isn’t finite—if you build it right—is the capability to spot opportunity, buy well, operate better, and repeat. That capability is Evolution’s real moat. The next decade will show whether it endures.

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music