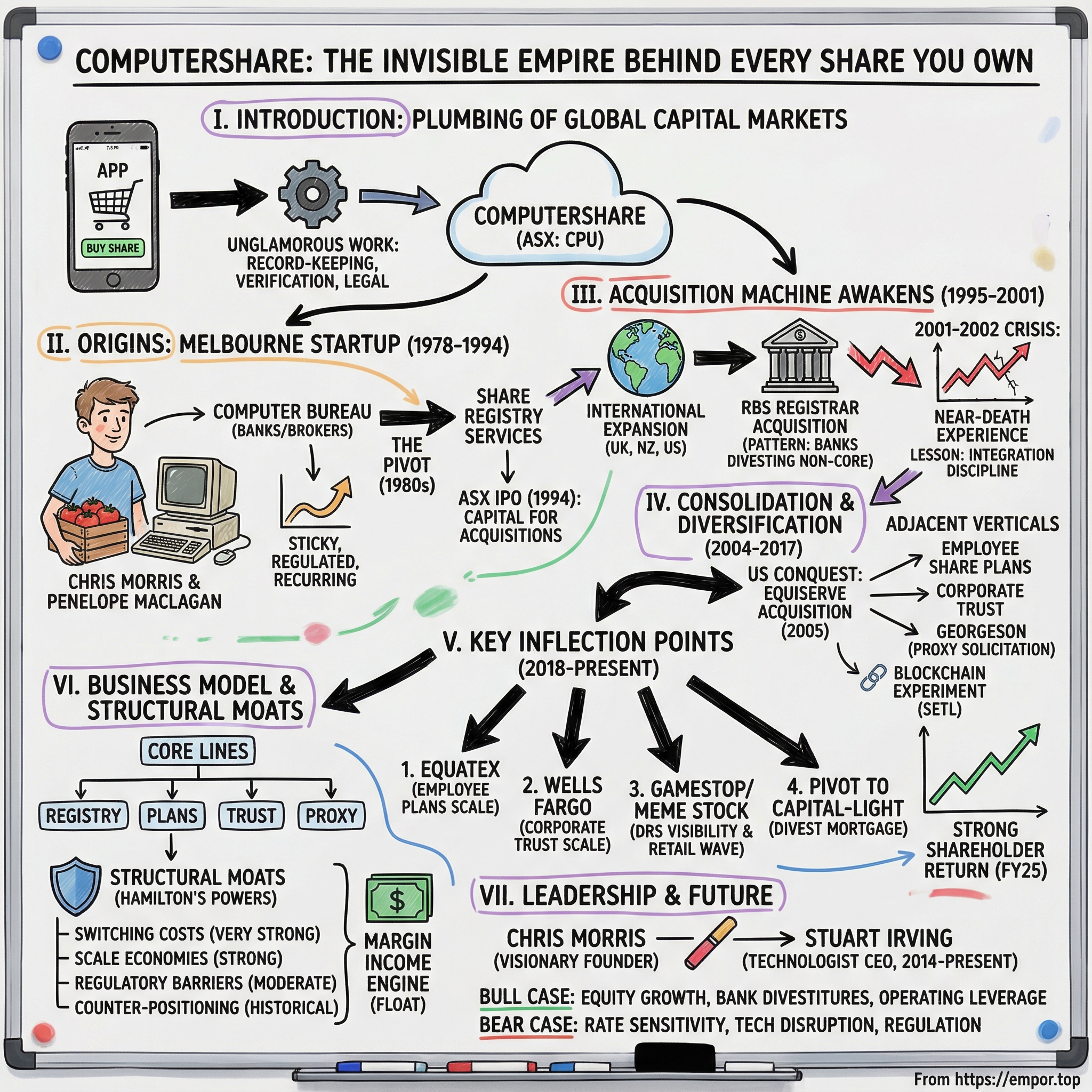

Computershare: The Invisible Empire Behind Every Share You Own

I. Introduction: The Company Running the Plumbing of Global Capital Markets

Picture this. You open your brokerage app, tap a few buttons, and suddenly you own a piece of Apple, Microsoft, or GameStop. It feels instantaneous, almost magical.

But the trade isn’t the end of the story. Behind that clean interface is a lot of unglamorous work: record-keeping, verification, and legal documentation. Somewhere, a system has to update to reflect that you, specifically you, now own those shares. Someone has to make sure dividends get paid correctly, proxy voting materials get delivered, and that when a company does a stock split, the paperwork and math come out right.

That “someone” is, more often than not, a company you’ve probably never thought about: Computershare Limited.

Computershare is based in Australia and is the largest transfer agent in the world by market share. It works with some of the biggest names in corporate America, including Apple, Amazon, Microsoft, Disney, and GameStop. And despite sitting in the critical path of global equity ownership, it has historically operated in the background—until the meme-stock era dragged it into the public conversation.

The hook is simple: every time you buy a share, someone has to record that you own it. And there’s a very real chance that “someone” traces back to a Melbourne startup from the era before “startup” was even a word people used.

When Computershare listed on the Australian and New Zealand stock exchanges in 1994, it was tiny—about A$36 million in market value, managing roughly 6 million shareholder accounts, with around 50 staff. Today, it’s a global operation with offices in 20 countries across five continents and more than 18,000 employees. At its core, it runs the systems that maintain shareholder records, process dividends, and handle proxy voting, serving more than 16,000 private and public issuers worldwide.

This is one of the great compounding stories in Australian business: a company that grew by systematically acquiring competitors, expanding into adjacent services, and building what might be one of the stickiest models in financial services. It’s the story of how a programmer from Melbourne built an invisible empire worth billions, how that empire survived near-death moments, pushed into international markets, and then—almost unbelievably—became a rallying point for retail investors during the GameStop saga.

A few themes will keep showing up as we go: disciplined acquisitions that compound over decades; switching costs so high that clients rarely leave; regulatory moats that keep newcomers out; and a deceptively powerful profit engine called margin income—earning interest on client cash balances in the course of doing all that “plumbing.”

So let’s start where this kind of story always starts: with the founder who noticed a problem hiding in plain sight.

II. Origins: A Melbourne Startup Before Startups Were Cool (1978-1994)

The Founder's Journey

Chris Morris wasn’t an obvious future CEO. By his own account, his teenage years were shaky—he struggled at school and wasn’t sure where he was headed. The turning point came when he found something he actually wanted to do: programming.

“I was passionate about programming, so I actually loved going to work,” Morris later said. “I think that’s the key to life. If you don’t really want to go to work, you’re probably not going to be good at it.”

That mix of obsession and work ethic showed up early. While he was starting out as a computer programmer, he ran a side hustle growing tomatoes—packing them after work, then getting up before dawn to sell them at Melbourne’s Queen Victoria Market. It’s an unusually vivid origin story for a company that would one day sit in the middle of global capital markets: a future financial infrastructure founder, hauling produce crates at sunrise.

And Morris had the kind of confidence that, in hindsight, sounds like a prerequisite for building something this ambitious. “The other thing I’ve always believed is that if you don’t believe in yourself, nobody ever will… I always believed I was the best computer programmer in the world.”

In 1978, in suburban Melbourne, Morris and his sister Penelope Maclagan founded Computershare—one of the city’s earliest technology start-ups. This was well before venture capital felt mainstream, before “disruption” became a business cliché, and long before the internet. The Apple II had only just appeared, the IBM PC was still years away, and plenty of businesses were still running on paper ledgers and typewriters.

The Pivot That Made Everything

Computershare didn’t start as a share registry. At first, it was a computer services business: a “computer bureau” that helped organizations automate data-heavy processes at a time when owning serious computing power in-house wasn’t a given. The early focus was on banks and stockbrokers—customers who had mountains of transactions and an urgent need to process them accurately.

Then, in the 1980s, the company found the wedge that would define its future: share registry services. Australia’s financial deregulation opened up banking and capital markets, stock market participation grew, and suddenly the back-office machinery of ownership needed to scale. The problem was that much of it still looked like it belonged to another era—paper certificates, manual ledgers, handwritten updates.

Computershare saw the opportunity to do what it had been doing all along: take a process everyone accepted as slow and messy, and make it computerized, reliable, and repeatable. That shift helped it win early clients, including smaller listed companies that needed shareholder record management as markets modernized.

Even then, the appeal of this niche was obvious. It had built-in defenses. It was highly regulated, so newcomers couldn’t just show up and wing it. It came with natural switching costs, because once a company’s shareholder records lived on your system, moving them was risky and painful. And it was recurring—issuers needed the work done every year, not just once.

Building the Australian Beachhead

For the next sixteen years, from 1978 to 1994, Computershare quietly built its Australian base—deepening its expertise, refining its systems, and earning trust with issuers. Along the way, it landed major professional-services clients in Australia and New Zealand, including KPMG, Coopers & Lybrand, and Ernst & Young.

Morris became Managing Director in 1990. By then, he wasn’t just a technologist with a service business—he had years of accumulated understanding of how the securities industry actually worked and what its users needed.

The decision to go public in 1994 wasn’t about ringing a bell for prestige. It was strategic. Morris and the team could see that the real prize was bigger than Australia. Globally, the securities services world was fragmented—often run inside banks or trust companies, market by market. A company with proven systems and access to public-market capital could start consolidating that landscape.

So Computershare listed on the Australian Securities Exchange as ASX: CPU. The IPO gave it the currency and firepower to pursue the acquisition strategy that would define the next several decades. Investors weren’t just buying an Australian registry business. They were buying the early version of a platform with international ambitions—whether they realized it or not.

Those early years also set the DNA that never really changed: use technology to make regulated, high-stakes workflows run better; grow steadily; and then accelerate by buying capabilities and scale. That combination would take Computershare from suburban Melbourne into the center of global equity ownership.

III. The Acquisition Machine Awakens (1995-2001)

International Expansion Begins

With the IPO behind it, Computershare wasted no time doing what public-market capital is great for: buying its way into new markets.

The company had always been a technology-and-process business at heart, but now it started applying that capability overseas. In 1997, it expanded its registry operations into New Zealand and the United Kingdom—and, crucially, acquired the Royal Bank of Scotland’s registrar department.

That RBS deal mattered far beyond the immediate revenue. It revealed a structural opening in the market that Computershare would exploit for decades: banks had long run share registry operations as a side business, but as the work became more regulated, more tech-heavy, and more operationally fragile, it started to feel like a distraction. For a bank, a registry unit could be useful—until it became a compliance headache that demanded constant investment and delivered little strategic upside.

Computershare’s pitch was simple and compelling: sell us the registry operation, and we’ll specialize in it. We’ll modernize the systems, take on the regulatory burden, and run it as a core business—not an afterthought.

The RBS acquisition also brought in people, not just clients. One of them was Stuart Irving, a young IT professional who joined through that transaction and would eventually rise to become CEO.

From there, the pace picked up. Computershare opened a London office and began winning UK-based work, including servicing Australian-listed companies that also traded in London. It moved into South Africa by acquiring Consolidated Share Registrars and Optimum Registrars. By 2000, it had established operations in the United States and Canada, putting it on the map across the major English-speaking capital markets.

The Growth Machine

This is the phase where Computershare stopped looking like a fast-growing Australian specialist and started looking like a global consolidator.

In the span of just a few years, it grew from a relatively small operator into a company with meaningful scale across multiple continents. Revenue surged, EBITDA climbed, headcount exploded, and by 2001 the market was valuing Computershare in the billions, with thousands of employees spread across Australia, New Zealand, the UK, South Africa, North America, and Hong Kong.

And it wasn’t random growth. A repeatable playbook was forming:

Find registry businesses sitting inside larger institutions where they’re non-core—often banks. Buy them. Move clients onto Computershare’s platforms and processes. Consolidate operations. Then cross-sell adjacent services.

Done well, this kind of roll-up becomes self-reinforcing. Each acquisition adds scale and expertise, which makes the next acquisition easier to integrate, which improves the economics of the whole machine.

But “done well” is carrying a lot of weight there.

The 2001-2002 Crisis: A Near-Death Experience

Then came the moment where the market forced Computershare to prove it could do more than just buy companies.

By late 2001, the share price had fallen sharply from its earlier highs as investors started to worry about near-term earnings. The broader environment was ugly—the dot-com bubble had burst, markets were rattled—and Computershare had expanded so aggressively that it was starting to show.

On January 20, 2002, the company issued a profit warning. The reaction was immediate and brutal: the stock dropped more than a third in a single day, erasing about A$1 billion in market value. Analysts downgraded the company and told investors to step back.

The underlying problem wasn’t mysterious. Computershare had been moving so fast that integration discipline slipped. Costs came in higher than expected. Synergies took longer than promised. The business had become more complex than the organization was prepared to manage.

It was a painful lesson, but an important one: M&A skill isn’t just about finding deals. It’s about making them work after the ink dries.

Computershare survived, and the experience hardened the company. In the years that followed, it developed a more rigorous approach to due diligence, more realistic assumptions on timing and synergies, and a more systematic post-merger integration process—exactly the kind of operational muscle you need if acquisitions are going to be your main engine.

And that mattered, because Computershare wasn’t done buying. Not even close.

IV. The Consolidation Years: Building the Global Registry Empire (2004-2017)

Conquering North America

If Computershare wanted to become the default back-office for global equity ownership, there was one market it had to win: the United States.

The US had the deepest public markets on earth—more listed companies, more shareholders, more corporate actions, more of everything. It was also the hardest turf: big incumbents, long relationships, and a lot of issuers that didn’t love the idea of trusting a critical function to a foreign company they’d barely heard of.

Computershare started by stacking up smaller footholds. In 2004, it acquired the stock transfer operations of Harris Bank and Montreal Trust, and it also bought Germany-based Pepper Technologies AG. Those moves added capability and reach. But the real step-change came the next year.

In June 2005, Computershare announced it had completed the acquisition of EquiServe from DST Systems. Chris Morris didn’t mince words: “This is the most momentous acquisition in Computershare’s history, both in size and strategic importance… Growing our business in the US has always been a critical part of our global strategy and this deal positions us as a leader in the US in both share registry and employee plans.”

EquiServe was the largest transfer agent in the United States. By buying it, Computershare didn’t just gain scale—it bought credibility overnight, plus a roster of major American corporate clients that would have taken years to win one by one. The deal, valued at roughly $307 million, effectively moved Computershare from “international entrant” to “top-tier player.”

And it compounded. Coming soon after the acquisition of Pacific Corporate Trust Company in Vancouver, EquiServe helped cement Computershare as the largest transfer agent in North America. As Steven Rothbloom, President and CEO of Computershare North America, put it: “Our growing critical mass in North America gives Computershare the capacity and scale we need to service the largest companies in the US.”

This was the acquisition machine, upgraded: not just expanding into markets, but taking commanding positions inside them.

Diversification Into Adjacent Verticals

With registry scale building, Computershare didn’t stop at the core. It broadened deliberately—into businesses with the same attractive properties that made share registry such a fortress in the first place: regulation, operational complexity, recurring workflows, and punishing switching costs.

In 2006, it bought shareholder management services from National Bank of Canada. In 2007, it acquired Datacare Software Group and its products GCM and Boardworks.

Then it kept pushing outward. In early 2008, Computershare announced a cash takeover offer for Australian mailhouse group QM Technologies Limited. Later that year, it bought the Lichfield-based Childcare Voucher Services business called Busy Bees and rebranded it as Computershare Voucher Services.

In 2010, it acquired HBOS Employee Equity Solutions from Lloyds Banking Group for around £40 million.

And in 2012, it made another major statement in the US by acquiring Shareowner Services from Bank of New York Mellon for approximately $550 million—yet another example of a bank deciding this “plumbing” was too operationally heavy to keep in-house, and a specialist like Computershare was better suited to run it.

The Employee Share Plans Strategy

One adjacency, in particular, started to look like a second core.

In 2013, Computershare completed the acquisition of the EMEA-based portion of Morgan Stanley’s Global Stock Plan Services business. The direction was clear: employee equity was becoming a big, global, permanent feature of corporate compensation—and it needed an administrator that could operate across borders.

Employee share plans aren’t just “send people stock.” They require handling regulatory rules in multiple jurisdictions, tax and withholding calculations, trading restrictions, and constant participant communications. It’s intricate, it runs year after year, and once a company’s plan is wired into an administrator’s systems, ripping it out and moving it is disruptive and risky.

For Computershare, the appeal was even bigger: many issuers that needed a transfer agent also needed someone to run their employee equity programs. Offer both, and you can win accounts with an integrated pitch, cross-sell into an existing base, and become even harder to replace.

Technology & Innovation Bets

By the mid-2010s, the industry conversation shifted to a looming question: what happens if the underlying infrastructure of ownership changes?

In 2016, Computershare began collaborating with SETL on a blockchain project. The share registry business didn’t get disrupted overnight, but the experiment mattered. It showed Computershare understood that even a seemingly “locked up” market can be threatened by technology shifts—and that staying comfortable is the fastest way to become irrelevant.

Computershare also strengthened a different kind of capability: influence and communication between companies and their shareholders. In 2003, it acquired Georgeson Shareholder Communications and renamed it Georgeson Inc.

Georgeson, founded in 1935 as Georgeson & Company Inc., was a pioneer in proxy solicitation and unclaimed property services, and over decades built a reputation as a global leader in strategic shareholder communications and consulting. Proxy solicitation—helping companies gather votes for annual meetings or in contested situations—fit perfectly with Computershare’s broader mission: not just recording ownership, but managing the ongoing relationship between issuers and their shareholders.

Step by step, deal by deal, the pattern stayed consistent. Computershare wasn’t collecting random businesses. It was assembling an integrated platform around a single job: helping public companies handle the messy, regulated, mission-critical reality of having shareholders.

And the more it added, the stickier the platform became.

V. The Key Inflection Points (2018-Present)

Inflection #1: The Equatex Acquisition (2018)

By 2018, Computershare’s employee share plans business was already on a clear trajectory. But it wanted something specific: more scale in Europe, and a modern platform it could standardize around globally.

On 12 November 2018, Computershare completed its acquisition of Equatex Group Holding AG, a European employee share plan administration business headquartered in Zurich, after receiving regulatory approvals. Equatex itself had a familiar origin story in this industry: it was formerly the European share plans business of UBS Wealth Management.

The numbers told you why it mattered. Equatex served more than 160 clients and over a million share plan participants. And it came with a key asset that wasn’t just a client list: the EquatePlus technology platform, which would become central to Computershare’s employee plans strategy.

Computershare described the deal as part of a disciplined, selective acquisition approach, and the logic was straightforward. Employee equity administration is recurring, complex, and deeply embedded in how large companies pay and retain talent. If you can run it well across jurisdictions, you become very hard to replace.

That showed up later in results. During FY2025, the Employee Share Plans business performed strongly, with revenue up 9% and management EBIT up over 15%. By then, Computershare had completed the global roll-out of EquatePlus across its major markets and was delivering the synergies it had promised.

Equatex was important for another reason too: it was proof that Computershare could still do what it had learned the hard way in the early 2000s—integrate a significant acquisition and absorb a complex technology platform without losing control of the machine.

Inflection #2: The Wells Fargo Corporate Trust Deal (2021)

Then came the biggest swing in the company’s history.

Wells Fargo entered into a definitive agreement to sell its Corporate Trust Services business to Computershare for $750 million. The acquisition was announced on March 23, 2021, and it closed on November 1, 2021.

This wasn’t a small tuck-in. Around 2,000 employees transferred to Computershare, and with them came most of the existing systems, technology, and offices that ran the business. Overnight, Computershare didn’t just expand—it planted a flag in a major adjacent category.

Corporate trust is the debt-market cousin of share registry. Instead of maintaining shareholder records, you act as trustee or agent for bond issuances: calculating and distributing payments, handling documentation and compliance, and serving as a fiduciary intermediary for issuers and investors. It’s regulated, high-volume, operationally unforgiving work. And once a deal is set up, switching providers is painful.

In other words: it rhymed perfectly with Computershare’s core model.

The business—now known as Computershare Corporate Trust—operates as a standalone line within the group and is ranked among top service providers in league tables by deal count and dollars serviced. Following the Wells Fargo acquisition, Computershare Corporate Trust ranked among the top providers in the U.S., including ranking #1 in CMBS.

The rationale was elegant. Corporate trust shared the same structural advantages as registry: recurring workflows, high switching costs, and scale benefits. And, once again, it was an area long dominated by banks that increasingly viewed it as non-core.

The leadership thread tied back to Computershare’s long-running consolidation playbook. Frank Madonna, who joined in 2012 through the acquisition of BNY Mellon Shareowner Services, was responsible for the corporate trust business. From July 2023, he also took responsibility for corporate trust in Canada, where Computershare has long-standing market leadership with product expertise that traces back to predecessor companies founded in 1889.

Inflection #3: The GameStop/Meme Stock Phenomenon (2021-Present)

Then came the most unexpected chapter in Computershare’s history: it became famous.

In January 2021, GameStop shares surged from around $20 to nearly $500 in days, fueled by retail investors coordinating on Reddit’s WallStreetBets. The spectacle set off a broader debate about market structure, short selling, and just how many intermediaries sit between an investor and a share.

And that’s where Computershare—usually invisible—suddenly stepped into the spotlight.

The direct registration system, or DRS, had been around since the 1990s. But GameStop’s retail investor base seized on it as a strategy: move shares out of brokerages and register them directly with Computershare, GameStop’s transfer agent, so the shares were held in the investor’s own name rather than in “street name” through a broker.

As of the last quarter, approximately 75.4 million shares of GameStop’s Class A common stock were held with Computershare—about a quarter of the company’s outstanding shares. Among publicly traded U.S. companies, GameStop became one of the most extreme examples of mass direct registration by individuals.

The cultural impact was real. “DRS your shares” became a rallying cry. And “Computershare” became, improbably, a verb in meme-stock communities.

Underneath the memes was a clear shift in awareness. Transfer agents keep the official records of registered shareholders and handle services like share transfers, dividend payments, and shareholder communications. Many retail investors had never thought about that layer. Suddenly, millions did.

For Computershare, the phenomenon brought both visibility and volume: an influx of DRS requests that created processing fees and a wave of new account relationships. It was not the sort of marketing campaign you can buy—because it wasn’t marketing at all. It was a grassroots movement that happened to run straight through Computershare’s systems.

Inflection #4: The Strategic Pivot to Capital-Light (2023-Present)

After years of building outward, Computershare also made a telling move in the other direction: it sold a business that didn’t fit.

Rithm Capital announced it had entered into a definitive agreement to acquire Computershare Mortgage Services Inc. and certain affiliated companies, including Specialized Loan Servicing LLC, for approximately $720 million. The transaction included roughly $136 billion in unpaid principal balance of mortgage servicing rights.

This was more than a portfolio cleanup. Mortgage servicing was capital-intensive and cyclical—very different from the company’s core franchises where software, compliance, and process scale do most of the heavy lifting. It had also been a consistent drag on profitability.

The divestiture freed Computershare to lean harder into the businesses that best matched its strengths: share registry, employee share plans, and corporate trust.

As CEO and President Stuart Irving put it, “Rithm has strong mortgage industry credentials and the ability to bring capital to scale the business further. With its track record of successful M&A execution and integration, we expect a smooth transition for the business and our customers.”

Recent Acquisitions & Continued Growth

Computershare kept tightening its focus around its core “plumbing” franchises. In April 2024, it announced it had agreed to acquire BNY Trust Company of Canada from BNY Mellon through its Canadian trust company, Computershare Trust Company of Canada.

The deal valued the business at AU$97.7 million. Based in Toronto, BNY Trust Company of Canada brought a portfolio of around 1,800 corporate trust mandates—exactly the kind of dense, relationship-driven book that fits Computershare’s model.

And the broader story was that the market liked the direction of travel. Total shareholder return in FY2025 was 59%, outperforming the ASX 100’s 14%. Over the past three years, Computershare delivered TSR of 78%, compared to 48% for the ASX 100.

Operationally, Computershare reported FY25 management EPS of 135.1 cents, up 15% year over year. EBIT excluding margin income rose 17.8%, and margins expanded to 17.5%.

The headline was simple: after decades of compounding, the company was still finding ways to sharpen the portfolio, scale the core, and turn “boring” infrastructure into a growth story.

VI. Understanding The Business: What Does Computershare Actually Do?

The Core Business Lines

At its heart, Computershare does something that sounds almost too plain to matter: it keeps the official record of who owns what. But once you’re the system of record for ownership, you’re also on the hook for everything that flows from it—and that’s where the complexity (and the value) lives.

The company’s transfer agency and share registry services are the foundation. Computershare maintains shareholder records, processes dividend payments, and facilitates proxy voting for more than 16,000 private and public issuers worldwide. In practice, that means running high-integrity ownership databases, handling share transfers, and distributing payments securely. It also means being ready for the messy, high-volume moments when stakes are highest—mergers, stock splits, tender offers, and IPOs—when huge numbers of records and transactions have to be processed quickly and correctly.

Because it operates across jurisdictions, Computershare can support cross-border ownership while still complying with local rules. That’s a quiet superpower for global companies with investors scattered around the world.

Beyond registry, Computershare has built out a set of adjacent businesses that look different on the surface but rhyme underneath: employee share plans (administering equity compensation programs), corporate trust (acting as trustee or agent for debt securities), proxy solicitation through Georgeson (helping companies gather shareholder votes), and communications services (the printing, mailing, and electronic delivery of shareholder materials).

Altogether, Computershare operates in 22 countries across five continents, with more than 80 office locations. Its client base spans more than 25,000 organizations, from public companies to governments and financial institutions.

Why This Business is Structural

The transfer agent business is hard to disrupt for one reason: nobody wants to mess with the ownership ledger.

If an issuer switches transfer agents, every shareholder record—potentially millions of them—has to be migrated from one system to another. And the tolerance for mistakes is basically zero. Get it wrong, and shareholders might not receive dividends, might not get proxy voting materials, or could lose access to their holdings. The reputational risk to the issuer is enormous.

It’s also not a standalone database you can forklift from one provider to the next. Transfer agents sit inside the broader securities plumbing. They connect with depositories like DTCC, with brokerage firms, paying banks, tax authorities, and regulators. Switching providers isn’t just a vendor change; it’s rebuilding a web of operational and regulatory connections.

Then there’s compliance. Transfer agents operate under a thick stack of rules across multiple jurisdictions. A new entrant would need years to build the regulatory expertise and institutional relationships that incumbents have accumulated over decades.

And for individual investors, there’s the mechanism that became famous during GameStop: direct registration. People and institutions can hold shares directly in their own name on the company register—a share ledger maintained by the transfer agent. The direct registration system isn’t new; it’s been available since the 1990s, and the SEC has facilitated and supported it as a legitimate method of share ownership.

The Margin Income Component

One of the most misunderstood parts of Computershare’s model is margin income—essentially, the interest it earns on client cash balances.

Computershare is constantly moving money around on behalf of clients. When a company pays dividends, that cash sits briefly in Computershare’s accounts before it’s distributed to shareholders. When employees exercise options, proceeds flow through Computershare. In corporate trust, cash can accumulate as payments are calculated and distributed. Across all of that activity, Computershare earns interest on the “float.”

In FY25, management revenue rose 4.4%. Management EBIT excluding margin income was $412 million, up more than 17%. Margin income was resilient at $759 million, slightly ahead of expectations.

Looking ahead, FY26 guidance targeted 4% EPS growth, driven by 5% growth in EBIT excluding margin income and cost efficiencies, even as margin income was expected to decline about 5%. That’s the trade-off embedded in the model: margin income can be powerful when rates are favorable, but it’s sensitive to rate cycles. Computershare has worked to insulate a substantial portion of client balances from rate fluctuations, but interest rates still matter.

Global Scale

Even though Computershare is listed on the ASX, it’s not really an “Australian-only” business anymore. It operates in more than 20 countries and derives almost 95% of revenue from outside Australia. All Executive KMP are based outside Australia, most Non-executive Directors are based outside Australia, and more than 90% of the workforce is international.

That footprint is both an advantage and a burden. For a multinational issuer with shareholders spread across the globe, a truly global registry provider can simplify operations dramatically. But running this business across 20-plus regulatory regimes takes constant investment—in systems, controls, and people who know how to navigate local rules without breaking the global machine.

VII. Leadership: From Founder Vision to Professional Management

The Founder: Chris Morris

Chris Morris co-founded Computershare in 1978, became chief executive in 1990, and led the company through its most formative growth years until 2006. He then moved into the chairman role, staying there until 2015, when he stepped back to become a non-executive director.

That arc matters because Computershare’s success wasn’t just a function of being early. Morris had an unusually deep understanding of the securities industry and what its users actually needed—both in Australia and internationally. Pair that with a long-term strategic vision, and you get a company that didn’t simply build a product; it built a full suite of services that listed companies and their stakeholders could rely on.

His handover is also a quiet flex. Morris didn’t cling to day-to-day control. He transitioned from founder-CEO to chairman to non-executive director in stages, retaining strategic oversight while professional management took over operations. For a business built on trust, continuity, and low tolerance for mistakes, that kind of succession planning is not just good governance—it’s part of the product.

After stepping back, Morris focused more of his attention on other passions—tourism, hospitality, and the outdoors—through his private Morris Group, which has interests in hospitality and a number of technology companies.

Current Leadership

Stuart Irving was appointed President and CEO of Computershare in July 2014. His path to the top is both unusual and revealing.

Before Computershare, Irving held roles at The Royal Bank of Scotland. He joined Computershare in the UK as an IT Development Manager, then moved through postings in South Africa, Canada, and the United States—an internal tour of the company’s expanding empire. In 2005, he became CIO for North America, and in 2008, he stepped into the role of Group CIO.

That timeline connects back to one of the most important early acquisitions. Irving joined in 1998, shortly after Computershare acquired RBS’s registry business, and he was part of the integration team that took Computershare’s registry software and made it work for Europe. In other words: he didn’t just watch the acquisition machine from the sidelines—he helped make the integrations real.

By the time Irving became CEO in 2014, he had spent years as the person responsible for the thing Computershare ultimately sells: reliable, secure, high-volume systems that don’t break when the stakes are highest.

A CIO becoming CEO says something fundamental about what Computershare actually is. Transfer agency can look like administration from the outside, but in practice it’s a technology business wearing a financial-services name tag. The competitive edge comes from quality, resilience, security, and the ability to operate at scale across regulatory regimes.

As Irving put it: “Having that IT background is very, very good because you’ve already worked with all lines of the business.”

That background shows up in how he describes his approach to leadership: “I do have a different perspective. I will give priorities to certain projects. I will take up more of a technologist’s view that you need to have rapid pilots and know that not everything’s going to work and that’s going to be OK.”

Irving’s tenure has now stretched beyond a decade, and his compensation has been reported at approximately $5.53 million per year. He also directly owns about 0.035% of Computershare’s shares.

VIII. Competitive Analysis: Porter's Five Forces

Threat of New Entrants: LOW

Starting a transfer agent from scratch sounds, on paper, like a straightforward enterprise software problem: build a database, track ownership, send out statements.

In reality, it’s closer to trying to replace the air-traffic control system while planes are still in the sky. The barriers are steep:

Regulatory barriers: Transfer agents operate under a thicket of rules—SEC regulations in the U.S., FCA rules in the U.K., ASIC requirements in Australia, plus local regimes in every other market they serve. You don’t “move fast and break things” in this business. Building the compliance and control infrastructure takes years and serious investment.

Technology investment: The job isn’t just holding records. It’s processing corporate actions, running payments, and interfacing reliably with market infrastructure like depositories. Those systems reflect decades of accumulated development and operational learning. A new entrant would need to build, buy, or inherit that capability.

Switching costs: Even if you had the technology, issuers still have to be willing to move. Migrating shareholder records is expensive, high-risk work, with essentially zero tolerance for errors. That alone makes most companies reluctant to take a chance on an unproven provider.

Trust and reputation: This is a “one mistake can define you” industry. Lost records, missed dividend payments, or compliance breaches aren’t minor bugs—they’re existential events for the client relationship. Public companies generally won’t gamble their shareholder experience on a new name.

Bargaining Power of Suppliers: LOW

Computershare’s main inputs are people and technology infrastructure. Neither is controlled by a small number of suppliers. Cloud and IT vendors are largely interchangeable at the infrastructure layer, and while hiring skilled talent is always competitive, it’s not a market where any one supplier can dictate terms.

Computershare also does substantial technology development in-house, which reduces dependence on outside vendors and gives it more control over its destiny.

Bargaining Power of Buyers: MODERATE

On the front end, big issuers have leverage. If you’re a mega-cap with millions of shareholders and complex global equity programs, you can push hard on pricing and service commitments.

But once you’re live, the balance of power changes. Your shareholder data is embedded in Computershare’s systems, connected to your payment processes, communications workflows, and regulatory reporting. Switching becomes an operational project with real reputational downside. That “lock-in” is why Computershare’s expanded service set—built over years of acquisitions and supported by strong technology—does more than add revenue. It makes the core relationship harder to unwind.

Threat of Substitutes: LOW TO MODERATE

The most talked-about substitute is technology-driven reinvention—especially blockchain. Computershare’s collaboration with SETL in 2016 is a good signal that the company takes this seriously. In theory, a distributed ledger could change how ownership is recorded.

In practice, transfer agency sits inside a legal and regulatory framework that moves slowly. Even if the technology is ready, widespread regulatory adoption has lagged.

There’s also the “do it yourself” substitute: banks running internal registry operations. But the long-term trend has cut the other way. Banks have increasingly decided these businesses are non-core and have sold them to specialists like Computershare rather than reinvesting to keep them in-house.

Industry Rivalry: MODERATE

This is a competitive market, but it’s not a commodity market. The major players in transfer agency include Computershare, Equiniti Trust Co/American Stock Transfer & Trust, Continental Stock Transfer & Trust, BNY Mellon, and Broadridge.

Computershare has held the leading position, with 25.7% market share in 2022. In the S&P 500 subset, it was the transfer agent for more than half the index, with a market share of 56.5%.

The competition tends to revolve around service quality, reliability, and technology—especially around digitizing communications and improving investor engagement—more than around pure price-cutting. Firms like Broadridge, with deep strengths in investor communications and platforms, can be particularly sharp competitors on the “experience and technology” dimension.

And importantly, the industry has been consolidating for decades. Fewer large players generally means rivalry remains real, but the dynamics increasingly favor incumbents with scale, proven controls, and the credibility to win the biggest issuers.

IX. Hamilton's 7 Powers Framework Analysis

1. Scale Economies: STRONG

Computershare’s advantages start with scale—because this is a business where the fixed costs are enormous, and the marginal costs fall fast.

The same core technology platform can be deployed across jurisdictions. The compliance and control infrastructure you build to satisfy regulators and serve one issuer can be reused across thousands more. And once you’ve built processing systems that can handle millions of shareholder accounts, adding incremental clients becomes relatively low-cost.

That’s why, since its founding in 1978, Computershare has become known for exactly the work that benefits most from scale: high-integrity data management, high-volume transaction processing and reconciliations, payments, and stakeholder engagement.

2. Network Effects: MODERATE

Transfer agency doesn’t have classic network effects in the way social networks or marketplaces do—one more shareholder doesn’t suddenly make the service meaningfully better for every other shareholder.

But Computershare does benefit from ecosystem effects. Over decades, it has built deep working relationships with brokers, custodians, depositories, and the advisory ecosystem around issuers. Those connections create operational gravity: the more embedded you are in the flow of transactions and communications, the harder it is for a client to unwind you.

There’s also a quieter advantage in the data itself. Working across many issuers and shareholder bases allows Computershare to cross-reference patterns and improve processes in ways that can benefit multiple parties, even if it doesn’t look like a traditional network effect.

3. Counter-Positioning: HISTORICALLY STRONG

For a long time, banks and large financial institutions ran registries as a side business—useful, but not central. Computershare’s counter-positioning was to treat it as the main event: a pure-play specialist willing to invest in the technology, controls, and operational depth that banks often couldn’t justify for something they didn’t consider strategic.

The industry trend has validated that bet. Banks increasingly see registry work as non-core, and that has repeatedly created opportunities for Computershare to buy, integrate, and professionalize these operations. Frank Madonna’s arrival in 2012 through the acquisition of BNY Mellon Shareowner Services is one more example of that long-running pattern.

4. Switching Costs: VERY STRONG

If there’s a single power that best explains Computershare, it’s switching costs.

Moving a company’s shareholder register isn’t like switching email providers. It’s a high-stakes migration of legal ownership records, with no tolerance for errors. Get it wrong, and you’re talking about missed dividends, broken tax reporting, confused proxy voting, and a shareholder relations nightmare.

And in employee share plans, the lock-in runs even deeper. These programs are tied into payroll, HR, finance, and treasury workflows, which creates long-lived dependencies. By FY2025, Computershare’s Employee Share Plans business was showing the results of that embeddedness, with revenue up 9% and management EBIT up more than 15%, alongside completion of the global roll-out of its EquatePlus platform.

5. Branding: MODERATE

Computershare isn’t built like a consumer brand. In a B2B, regulated infrastructure business, brand really means something narrower and more valuable: reputation for reliability, control, and compliance in the eyes of issuers, boards, and advisors.

The GameStop era raised retail awareness dramatically, but it wasn’t the kind of brand lift that directly wins corporate mandates. If anything, it made the name more recognizable. The real “brand” that matters here is still trust: the belief that Computershare will run critical processes correctly, quietly, and at scale.

6. Cornered Resource: MODERATE

Over four decades, Computershare has accumulated a resource that doesn’t show up neatly on a balance sheet: deep regulatory and operational expertise across more than 20 jurisdictions.

This is hard-won institutional knowledge—how to run compliant processes, handle edge cases, and manage market-specific rules without breaking the global machine. Add in decades of proprietary technology development embedded in its platforms, and you get something that’s difficult for competitors to copy quickly, even if they have capital.

7. Process Power: MODERATE

Computershare has spent decades doing something most companies claim they can do, but few can sustain: repeatable acquisition and integration.

The discipline around due diligence, integration planning, and synergy capture is a capability in its own right. It’s not flashy, but it’s compounding. And it’s one of the reasons Computershare could build a global footprint through acquisition without constantly falling apart under the weight of its own complexity.

X. Bull and Bear Cases

The Bull Case

Structural growth in employee equity compensation: Equity has become a default part of how companies attract and keep talent. Stock options, RSUs, and employee share purchase plans aren’t just a Silicon Valley quirk anymore—they’re spreading across industries and across borders. The more companies lean into equity-based pay, the more they need administrators who can handle the complexity, the tax rules, and the participant volume. That’s a long runway for Computershare’s employee share plans business.

Continued bank divestitures: The same pattern that powered Computershare’s rise is still playing out. Banks keep deciding that registry and corporate trust are operationally heavy, regulated, and not worth the management attention. Every time a bank exits, a specialist with an integration playbook and a global platform looks like the natural buyer—and Computershare has spent decades becoming that buyer.

Margin income optionality: The “float” is still a meaningful lever. When rates are high, margin income can add a lot of profit without requiring a lot of incremental effort. And even if rates fall, the sheer scale of client cash balances means it remains an important contributor—just with less tailwind.

GameStop effect multiplied: GameStop didn’t just bring Computershare a wave of activity; it taught a mass audience that direct registration exists. If even a small portion of that behavior spreads beyond a single stock and becomes a persistent habit among retail investors, Computershare could see ongoing growth in account activity and processing volume.

Operating leverage: This business has a lot of fixed infrastructure—systems, compliance, processing capacity, and service teams built to handle high-stakes peaks. When revenue grows on top of that base, a meaningful portion can flow through to earnings. If Computershare keeps scaling without a matching increase in complexity, the operating leverage can be powerful.

The Bear Case

Interest rate sensitivity: Margin income cuts both ways. It’s been a major driver of profitability, but it is inherently tied to the interest-rate environment. If rates decline materially, earnings would feel it. Even with only modest rate movements, management expected margin income to fall by about 5% in FY26.

Technology disruption: The share registry business has proven hard to dislodge, but it’s not immune to long-term technological change. Blockchain hasn’t rewritten the system yet, but the core idea—more direct, more automated verification of ownership—still hangs over the industry. If markets ever move to a fundamentally different ownership ledger, incumbents would have to adapt quickly.

Regulatory changes: The rules are the moat, but they’re also the risk. If securities regulations shift in ways that change responsibilities, economics, or operating requirements, the transfer agency model could be pressured. Even changes that are “good for the market,” like shorter settlement cycles, can increase operational load and failure risk.

Integration risk: Computershare has built a reputation on integrating acquisitions reliably—but the risk never goes away. One misstep can mean service issues, unhappy issuers, and reputational damage in a business where trust is the product.

Currency exposure: With almost all revenue earned outside Australia, exchange rates matter. Currency moves can swing reported results and complicate planning, even when underlying performance in local markets is strong.

XI. Key Performance Indicators for Investors

If you’re trying to understand whether Computershare is actually getting stronger—not just getting a tailwind from interest rates—there are three numbers that do most of the work.

1. EBIT Excluding Margin Income (EBIT ex MI): This is the cleanest read on the core operating engine, with interest-rate noise stripped out. In FY25, EBIT ex MI rose 17.4%, and margins expanded to 17.5%—an improvement of 150 basis points. That’s what you want to see from a business built on recurring fees and high-volume transaction processing: more revenue flowing through a largely fixed cost base. Over time, this metric is the scoreboard for whether the franchise is gaining share, integrating well, and getting more efficient.

2. Management EPS Growth: This is the “all-in” measure that rolls up operational performance, margin income, capital allocation, and buybacks. In FY25, management EPS was 135.1 cents, up 15% year over year. For FY26, guidance called for about 4% EPS growth—suggesting a more normal year where execution matters at least as much as macro.

3. Client Balances and Yield: Margin income ultimately comes down to two dials: how much client cash Computershare is holding at any point in time, and what yield it earns on that cash. Average client balances were $30.2 billion, with a yield of 2.6%. Watching those two inputs is the simplest way to sanity-check where margin income is likely heading as rates move.

XII. Conclusion: The Quiet Compounder

Computershare is the kind of company markets often overlook: a quiet compounder that builds value through unglamorous but essential services, disciplined capital allocation, and steady, systematic expansion.

The arc is almost absurdly unlikely. It starts with Chris Morris, a young programmer in 1970s Melbourne hauling crates of tomatoes before sunrise, and runs all the way to a global operation led by Stuart Irving, a technologist-turned-CEO overseeing mission-critical systems across more than 20 countries. The scale has changed dramatically. The job hasn’t. Computershare is still in the business of helping companies manage the realities of having shareholders—keeping records straight, moving money accurately, running corporate actions cleanly, and keeping the whole machine compliant.

If anything, that job has become more important. More people own shares than ever. Markets move faster. The tolerance for operational failure has only shrunk. When you’re responsible for the official ledger of ownership, “good enough” isn’t a standard—you either get it right, or you don’t belong in the room.

That’s why the moat is so durable. Switching costs are punishing, because moving a shareholder register is high-stakes and error-intolerant. Regulation is a barrier to entry, because you can’t brute-force trust in a business built on compliance and control. And scale matters, because the fixed costs of technology, security, and governance get spread across an enormous base.

It’s also why the acquisition playbook keeps working. Banks and institutions continue to decide these operations are non-core and not worth the complexity. For Computershare, that steady drip of divestitures is opportunity—another chance to buy a book of business, integrate it, improve it, and compound the platform.

As Stuart Irving put it: "Today's results really validate our strategy. We made key strategic decisions to build a simpler, higher quality capital light Computershare, a group that can deliver consistent results."

What makes Computershare compelling isn’t any single headline moment—not even GameStop. It’s the accumulation of small advantages over decades: client relationships that deepen, systems that improve, acquisitions that get absorbed without drama, and a reputation that gets reinforced every time nothing goes wrong.

The company that records your share ownership will never be the exciting part of investing. But that’s the point. Excitement is fragile. Enduring infrastructure—run well, at scale, with high switching costs and real regulatory moat—can be one of the most reliable ways to compound value. And Computershare has spent nearly half a century proving it.

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music