Coles Group: Australia's Grocery Giant and the Duopoly That Shapes a Nation

I. Introduction: The Weight of Two Giants

Walk into almost any Australian town and you’ll see the same pair of signs, often within a few minutes of each other: Coles and Woolworths. From Sydney’s polished suburbs to remote Northern Territory outposts, these two brands set the tempo of everyday life, shaping how millions of people shop, what ends up in the trolley, and what’s left in the weekly budget.

Australia’s supermarket business is, for all practical purposes, an oligopoly. Coles and Woolworths together account for roughly two-thirds of supermarket sales nationwide. That level of concentration isn’t just an interesting statistic. It’s a structural feature of the country’s economy, with ripple effects for consumers, farmers, suppliers, and anyone trying to build a competing chain.

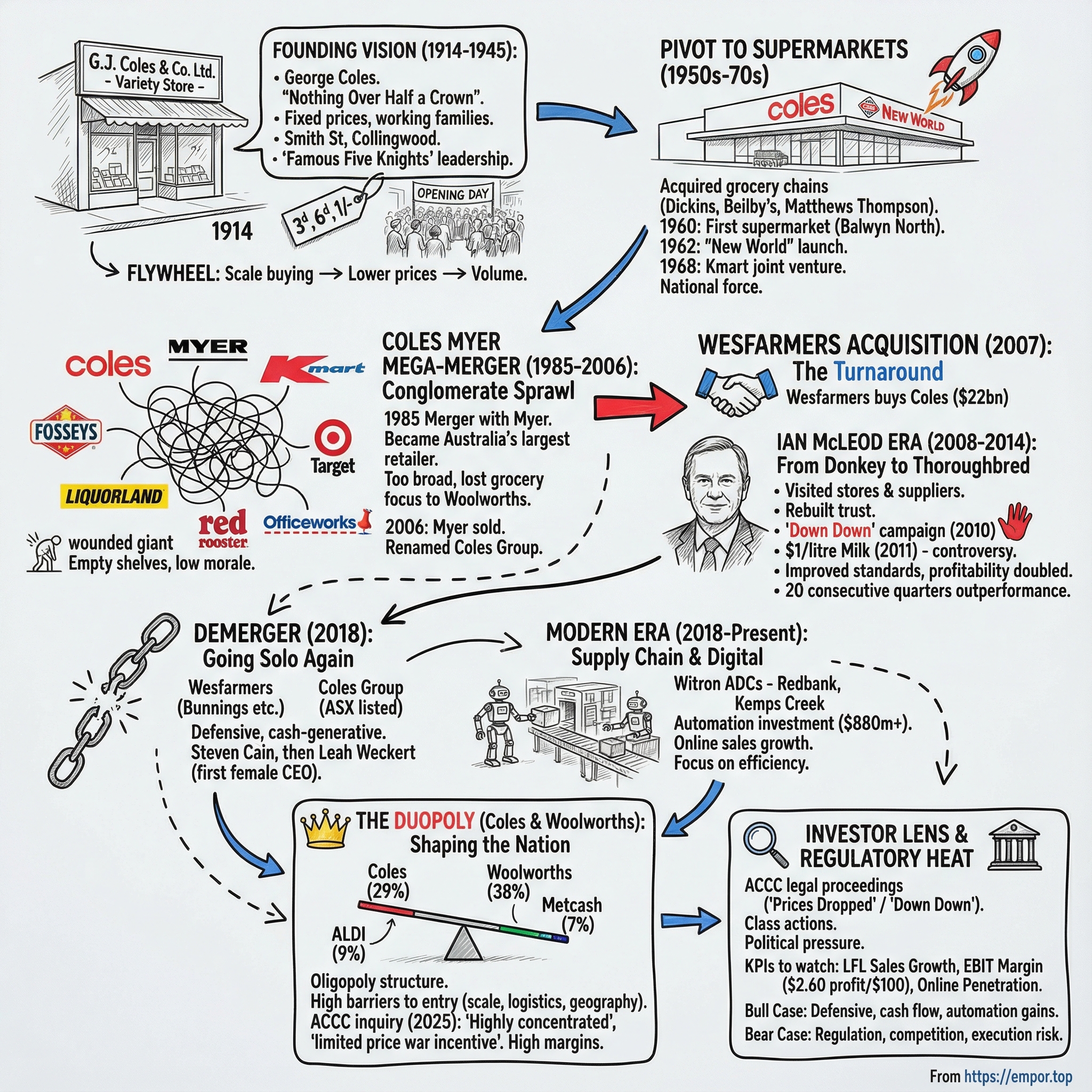

Coles began in 1914 as a variety store in Collingwood, a working-class suburb of Melbourne. Today it’s the second-largest retailer in Australia by revenue, sitting directly across the table from its principal rival, Woolworths. Which raises the deceptively simple question at the heart of this story: how did a small, fixed-price shop become one half of what may be the most entrenched grocery duopoly in the developed world?

To answer it, we have to follow more than a century of Australian retail history: a family dynasty that professionalized chain retailing early, an aggressive pivot into supermarkets, decades of conglomerate sprawl and internal complexity, and then one of the most widely admired corporate turnarounds in modern Australia. And all the while, there’s the dance partner that never leaves the floor: the duopoly itself, shaping pricing, service levels, supplier relationships, and the competitive landscape.

For investors, Coles is also a case study in defensive retail economics: the power of scale in a large, geographically isolated market, and the constant tension between stable cashflows and intense regulatory scrutiny. In the 2024 financial year, Coles reported sales revenue of nearly A$44 billion, up modestly from the year prior—evidence of just how enormous, and how steady, the engine has become.

We’ll tell this journey in five eras: the founding vision under the Coles family; the pivot from variety retailing to supermarkets; the conglomerate chaos of the Coles Myer years; the transformative Wesfarmers turnaround; and finally, Coles as an independent listed company, betting big on automation and digital transformation while facing a new wave of public and regulatory pressure.

II. The Founding Vision: George Coles and the "Nothing Over Half a Crown" Promise (1914–1945)

Picture Melbourne in April 1914. Europe was sliding toward war, but in Smith Street, Collingwood, a 28-year-old shopkeeper named George James Coles was fixated on a quieter upheaval: making everyday goods cheaper, simpler, and predictable.

On 9 April 1914, George and his brother Jim opened their first 3d, 6d, and 1/- variety store under the name G.J. Coles & Co. Ltd. It was a fixed-price shop aimed squarely at working families: drapery, crockery, kitchenware, hardware, stationery, haberdashery—useful things, sold at prices you didn’t need to negotiate.

George hadn’t dreamed this up in isolation. He’d learned retail at his father’s small general store in the Victorian country town of St James. But he wanted scale. After running the family store, he travelled to the United States and watched the rise of the 5-and-10-cent chains. The formula was powerful: standardize the assortment, buy in bulk, set the price, move volume. George came home convinced Australia was ready for the same idea.

He adapted it to local conditions and made the promise explicit. Coles would lower the cost of living for Australian families by keeping prices capped—first with “nothing over 1 shilling,” and soon after with the now-famous “nothing over 2s 6d” pledge.

And it worked immediately. On opening day, the store sold out. George later recalled the chaos with pride. “The opening day was a riot,” he wrote, with customers surging for the “Star Bargain”: a deep enamel mixing bowl priced at 1/-.

Then, almost as quickly as the shop found its footing, the world changed. War arrived. Jim enlisted and was killed in action. For many small businesses that would have been the end of the story. For Coles, it became the moment the venture hardened into a mission. George pressed on, bringing in another brother, Arthur, and laying the tracks for what became a family-run empire.

For the next six decades, Coles would be steered by the family. The leadership passed through what became known inside the business as the “famous five knights”: Sir George, Sir Arthur, Sir Edgar, Sir Kenneth, and Sir Norman—often referred to simply by their initials: GJ, AW, EB, KF, NC.

The model stayed strikingly consistent: a standard range of everyday goods, sold at fixed low prices, enabled by volume buying. Coles bought big, negotiated hard, and passed discounts on to customers. That flywheel—scale purchasing to lower prices to drive more volume—would remain the conceptual heart of Coles long after the merchandise and the stores themselves evolved.

The 1920s brought momentum and ambition. Coles expanded across Victoria, and in 1924 it opened a flagship in Bourke Street in the heart of Melbourne’s CBD. This wasn’t just another shopfront; it was theatre. The Bourke Street store also introduced Australia’s first self-service cafeteria, and it became, by reputation, the best place to eat in Melbourne at the time.

Then came the Great Depression—exactly the period you’d expect a retailer built on discretionary spending to pull back. Coles didn’t. Even in the toughest years, the company stuck with a commitment first made in 1922: donating a large share of profits to charities, including hospitals, nursing homes, and relief funds for the unemployed. This wasn’t merely a corporate policy. George Coles himself gave away so much personal wealth that, despite building one of Australia’s great retail fortunes, he never became a millionaire.

By the early 1930s, Arthur had taken the wheel operationally. Appointed Managing Director in 1931, A.W. Coles led what the company later described as its first major expansion. By 1933, Coles had a presence in every Australian state through a network of 30 stores. Arthur’s view of retail sounded simple, almost obvious, but it was discipline disguised as common sense: “A store has no right to success just because it is open for business and has a bright display,” he said. “Our goods must reflect the wishes of the community in which the store is located.”

And tucked into the origin story is a piece of Australian retail poetry. The building that once housed the original Coles Variety Store is now a Woolworths. The rival didn’t just beat Coles to a customer’s wallet; in this one spot, it literally took over Coles’ ground floor. The duopoly, in a sense, moved in on the birthplace.

By the mid-century, Coles was no longer a scrappy variety-store experiment. It was a scaled, disciplined retail machine with a philosophy that would endure: buy big, keep it simple, price it fairly, and make the customer feel the savings. The only question was what, exactly, that machine would become once Australia’s biggest retail category—food—came into view.

III. From Variety to Supermarkets: The Pivot That Defined Australian Retail (1950s–1970s)

Post-war Australia was getting richer, more suburban, and more car-based. For Coles, that meant prosperity, but it also meant a problem. The variety-store model that had worked so well for decades was running into a new force in global retail: the supermarket. Self-service, big baskets, wide aisles, and the kind of operating efficiency that made traditional counter-service grocery look slow and expensive.

Coles’ answer wasn’t to dabble. It went shopping.

Inside the company, the 1950s and 1960s later became known as “The Takeover Era,” and it earned the name. Rather than build a grocery business from scratch, Coles bought one—then kept buying. In 1958 it acquired the John Connell Dickins group of 54 grocery stores. Next came Beilby’s in South Australia in 1959, and then 265 Matthews Thompson grocery stores in New South Wales in 1960. These weren’t just bolt-ons. They were Coles placing a bet that the next great retail category wasn’t haberdashery or kitchenware. It was food.

In 1960, the first supermarket in this new push opened in Balwyn North, in Melbourne, trading under the Dickins name—at the corner of Burke and Doncaster Roads, where a modernised version still operates. It’s easy to miss how big a moment this was: Coles had found the format that would eventually define it.

Then Coles wrapped the strategy in a story the public could instantly feel. In 1962 it launched New World supermarkets, complete with Space Age rocket models and the promise of a “New World of Shopping”—food and variety goods together under one roof, in the modern self-service style that was spreading across the world.

And the American influence didn’t stop at groceries. In 1968, Coles entered a joint venture with U.S. retailer S.S. Kresge (later Kmart Corporation) to bring the discount department store concept to Australia. The first Kmart store opened in 1969 in the Melbourne suburb of Burwood, introducing Australians to the big-box, discount-led format—and giving Coles another powerful engine to sit alongside supermarkets.

By 1973, Coles had stores in every Australian capital city. The chain that began on Smith Street in Collingwood had become a national retail force.

But the 1970s also marked the end of something. In 1975, Coles appointed Sir Thomas North as its first Managing Director who was not a member of the Coles family—closing the long chapter of dynastic control and opening the door to a more modern, corporate Coles. That shift mattered, because it set up the next act: an era of empire-building so ambitious it would culminate in the biggest merger in Australian corporate history—and a retail conglomerate that would be both formidable and, eventually, unwieldy.

IV. The Coles Myer Mega-Merger: Empire Building and Its Discontents (1985–2006)

The mid-1980s were the age of the blockbuster deal in Australian business. Retail joined the party in the biggest way possible: in August 1985, Myer Emporium Ltd and GJ Coles & Coy Ltd agreed to merge, creating what was then the largest Australian corporation. The combined group adopted the name Coles Myer Limited in January 1986.

What made it so consequential wasn’t just the headline. It was the collision of two retail dynasties with different strengths. Myer was Melbourne’s storied department store powerhouse—Australia’s number one department store chain and the country’s third-largest retailer at the time. Coles, already a national force, bought Myer through an agreed bid valued at A$918 million.

The merger instantly turned Coles into an everything-retailer. It brought with it 56 department stores, 68 Target discount stores, 122 Fosseys discount variety stores, and the Red Rooster fast-food chain. It also included the Country Road chain of 45 stores, which Coles later sold for a profit of A$33.27 million.

For a while, the sprawl looked like strength. Coles Myer became Australia’s leading retailer by store count—more than 1,800 locations—and by selling area. Its footprint covered almost every corner of Australian and New Zealand retail: supermarkets (Coles, Bi-Lo), discount department stores (Kmart, Target, Fosseys), department stores (Myer, Grace Bros.), women’s fashion (Katies), toys (World 4 Kids), liquor (Liquorland, Vintage Cellars), fast food (Red Rooster), and office supplies (Officeworks). It was also Australia’s largest private employer, and it held the exclusive rights to the Kmart and Target names in Australia and New Zealand.

The shopping spree didn’t stop with the merger. In 1987, Coles Myer acquired Bi-Lo and ran it alongside Coles Supermarkets. It pushed across the Tasman, buying Progressive Enterprises in New Zealand, and by 1988 it was ambitious enough to list on the New York Stock Exchange.

Some bets paid off. Officeworks, inspired by the US “category killer” model of Office Depot, was established in 1993, with its first store opening in Richmond, Melbourne in June 1994—and it worked. Others didn’t. Around the same time, Coles tried to counter the arrival of Toys "R" Us with its own toy chain, World 4 Kids. It didn’t last.

By the early 2000s, the problem with the conglomerate strategy was becoming hard to ignore: it was simply too broad to be great everywhere. In 2001, Coles Myer appointed John Fletcher, formerly of Brambles, as chief executive. He did manage to lift performance for a period and made a genuinely strategic move by acquiring Shell Australia’s retail fuel operations and rebranding them as Coles Express—an important counterpunch to Woolworths’ discount petrol push.

But the underlying issue remained. While Coles Myer tried to manage a portfolio that looked like a shopping centre directory, Woolworths was sharpening its focus—especially in food and liquor—and steadily gaining ground.

Then came the unwind. In 2005, the company flagged that Myer could be demerged, divested, or retained. In 2006, it finally sold Myer to a consortium for A$1.4 billion. Coles kept Target, but the message was clear: the mega-conglomerate era was ending. Later that year, the company renamed itself Coles Group Limited, returning—at least in identity—to a tighter core.

What was left was a retailer with enormous scale and heritage, but a business that had lost momentum where it mattered most: in supermarkets. And that made it a prime candidate for the next, decisive chapter—new ownership, a hard reset, and a turnaround that would redefine Coles for a generation.

V. The Wesfarmers Acquisition: Australia's Biggest Corporate Takeover (2007)

By 2007, Coles Group was a wounded giant. For years, Woolworths had been steadily taking share while Coles’ day-to-day execution slipped. Shoppers complained about empty shelves. Stores felt tired. Team morale was low. Coles still had enormous scale, but it was no longer operating like a market leader.

That’s what made the next twist so surprising. The rescuer wasn’t another retailer, or a private equity consortium. It was Wesfarmers: a Perth-based conglomerate with roots in rural Western Australia, better known for businesses like Bunnings than for groceries.

In July 2007, Wesfarmers agreed to buy Coles Group for about $22 billion, in what was framed as the biggest takeover in Australian corporate history. The deal was executed via a scheme of arrangement: Coles shares were suspended from trading on the ASX on 9 November 2007, and Wesfarmers acquired Coles on 23 November 2007. The transaction was completed in early 2008.

Wesfarmers didn’t pretend it was acquiring a polished asset. It openly acknowledged the supermarkets were performing “poorly,” and it set expectations bluntly: this would take years, not months. The logic was clear. Wesfarmers believed it could bring the kind of disciplined, operator-first approach that had made Bunnings so formidable—and apply it to the country’s second-largest grocer.

Then came the crucial hire. In 2008, Ian McLeod, a former Asda executive with deep turnaround experience, arrived at Coles just months after the acquisition. And with him, the bet stopped being theoretical. Wesfarmers had bought a problem. Now it was time to rebuild it.

What followed would become one of the most celebrated corporate turnarounds in modern Australia.

VI. The Ian McLeod Turnaround: From Donkey to Thoroughbred (2008–2014)

To understand what Ian McLeod walked into when he took over Coles in 2008, start with a single scene. On his first day at the Hawthorn East headquarters, he was confronted with a wheelbarrow piled with old fruit—mouldy, sour-smelling, headed for the skip. It was almost too perfect as a metaphor: this was a business that had been allowed to go stale in plain sight.

McLeod would go on to become best known for his six-year run running Coles from 2008 to 2014, a period in which the company’s profitability surged and its standing in the market was fundamentally reset.

Wesfarmers hadn’t hired a caretaker. They’d hired a specialist. McLeod, a Scotsman with a career built on transformation, had worked across the globe. He’d played a key role in Asda’s recovery in the UK ahead of its sale to Walmart, served as chief merchandise officer and a board member at Walmart Germany, and led a turnaround at Halfords before its float. Coles was the next challenge, and it was a big one.

His method was simple, and relentless: go and look. McLeod made it a routine to turn up at stores unannounced. He wanted to see what customers saw, not what head office said was happening. What he found was a chain that felt frozen in time—layouts that hadn’t meaningfully changed in decades, a look and feel stuck in the 1970s, and stores that were cold and uninviting. The team members reflected the environment: tired, worn down, and demoralised.

Fixing that kind of decline isn’t a campaign. It’s surgery—and it starts with leadership. Wesfarmers gave McLeod the authority to rebuild the top team, sweeping out layers of management tied to the old bureaucracy and the years of underperformance. But he also understood that Coles couldn’t rebuild on the inside while remaining at war with the outside. Supplier relationships, in particular, had been badly damaged.

So he went to them. McLeod visited key suppliers and, in a moment that became legend inside the company, was the first Coles boss seen at Coca-Cola’s head office in 40 years. He didn’t arrive to demand concessions; he arrived to explain what he was trying to build—and why a healthier Coles could be better for both sides. That shift mattered. Stronger supply chain management helped improve availability and reduce costs, which supported lower shelf prices. And it showed up in how suppliers viewed Coles: in 2008, suppliers ranked the chain near the bottom. Over time, Coles moved into the top tier.

The plan itself was disciplined. McLeod described it as a five-year program delivered in phases: build a solid foundation, deliver consistently well, then create “the Coles difference.” The point wasn’t to do everything at once, but to move with pace while sequencing the work so the basics stopped breaking every day.

For shoppers, the turnaround became visible through a single, unforgettable piece of marketing. In 2010, Coles launched “Down Down,” with its red pointing hand and the slogan “Down Down, Prices Are Down.” The jingle was everywhere. More importantly, it was designed to do something Coles desperately needed: reset consumer perception and make value feel like a permanent position, not a temporary promotion.

Then came the move that made the strategy impossible to ignore. On Australia Day in 2011, Coles cut its own-brand milk to $1 a litre—an aggressive, round-number price that rival Woolworths matched immediately. By then, Coles had already pushed thousands of grocery items down in price under the “Down Down” banner, sometimes funding the reductions itself. Milk took that logic and turned it into a national headline.

It was brilliant marketing—and deeply controversial. Dairy industry leaders argued the price point would permanently cheapen milk in consumers’ minds and place long-term pressure on farmers. Australian Dairy Farmers president Fiona Simson put it bluntly: “There can be no doubt that the introduction of $1 milk in 2011 has had a demoralising and negative impact on the Australian dairy industry. It is time for the unrealistic price regime to end, for good.” The debate would linger for years.

But for Coles, momentum had finally returned. McLeod later said the business outperformed the market for roughly five years straight after the changes took hold, and that the early gains created a window to keep pressing the advantage before competitors fully responded. Under his watch, Coles improved store standards, product quality, and service, while leaning hard into value. The results were hard to argue with: profits roughly doubled, and the company outperformed for 20 consecutive quarters.

McLeod himself framed the achievement in simple retail terms. Transforming Coles, he said, meant transforming the value Australians felt they were getting. In mass-market retail, value isn’t a feature. It’s the job.

When McLeod left in 2014, Coles wasn’t just healthier. It was recognisably different: sharper execution, stronger supplier ties, and a brand that had clawed its way back into the fight. Wesfarmers had bought a problem. McLeod had helped turn it back into a competitor.

VII. The Demerger: Coles Goes Solo Again (2018)

By 2018, the turnaround was essentially done—and that created a new kind of problem. Coles was now a well-run, cash-generative machine. But in Wesfarmers’ portfolio, it also looked like a mature, lower-growth asset sitting next to businesses with much longer runways.

Wesfarmers chairman Michael Chaney put the logic on the record when the company announced its intention to demerge Coles: “Demerging Coles enhances Wesfarmers' prospects of delivering satisfactory returns to shareholders by shifting our investment weighting and focus towards businesses with higher future earnings growth prospects.”

He also made clear that this wasn’t an indictment of Coles. Quite the opposite: “Following a successful turnaround since it was acquired by Wesfarmers in 2007, Coles is once again a leading Australian retailer, well positioned to grow as a defensive business with strong investment characteristics.”

The rationale was simple. Grocery and liquor are enormous categories, but they’re not endless. Australians can only consume so much each week. Wesfarmers concluded it would be better off allocating capital toward areas with greater growth potential, while Coles—stable, defensive, and highly cash generative—could stand on its own.

There was also a portfolio math problem behind the story. Coles represented a large share of Wesfarmers’ capital employed, but a much smaller share of earnings. The business had grown significantly under Wesfarmers’ ownership—its earnings nearly tripled—but the returns profile still pulled down the group’s overall mix.

The process moved quickly once the decision was made. On Thursday 15 November 2018, Wesfarmers shareholders approved the demerger of Coles Group Limited. Court approval for the scheme of arrangement followed on Monday 19 November. And on Wednesday 28 November, it was done: Coles was demerged, and shares were transferred to eligible shareholders.

Under the demerger, 85% of Coles shares were distributed to Wesfarmers shareholders on the basis of one Coles share for each Wesfarmers share held at the record date. Wesfarmers retained the remaining 15% stake. Coles was expected to land as a top 30 ASX-listed company.

Independence also meant a leadership moment. Steven Cain took the helm as CEO, tasked with carrying the operational discipline of the Wesfarmers era into a company that now had to set its own strategy, fund its own transformation, and answer to the market directly. In 2018, Cain was appointed CEO of the Coles Supermarkets brand as part of the demerger.

For investors, the pitch was clean: a stake in a defensive retailer with strong cash flows, an entrenched market position, and dividend-friendly capital allocation. The real question was what came next—whether a newly independent Coles could keep standards high while spending what it needed to spend to stay competitive for the long haul.

VIII. The Modern Era: Supply Chain Revolution, Digital Transformation & Regulatory Heat (2018–Present)

The independent Coles that stepped out from under Wesfarmers in 2018 entered a different battlefield than the demoralised chain of 2007. It was bigger, steadier, and operationally sharper—but now it had to fund its own future while facing a market that expected constant improvement. Coles operated 846 supermarkets across Australia, including a number of former Bi-Lo locations that had since been rebranded, employed more than 120,000 people, and held about 27 per cent of the Australian market.

The biggest swing was behind the scenes: the supply chain. Coles embarked on what CEO Steven Cain described as one of the most significant investments in the company’s history—building automated distribution centres powered by German logistics specialist Witron.

The first Australian Automated Distribution Centre (ADC) using global leading Witron technology became the largest of its kind in the Southern Hemisphere. The Redbank facility in Queensland—at Goodman’s Redbank Motorway Estate—was officially opened with Prime Minister Anthony Albanese, Queensland Premier Annastacia Palaszczuk, Coles Group Chairman James Graham, and Cain on hand. It was also the first of two Witron facilities in the rollout, part of what Coles described as the biggest technology investment in its 109-year history.

A second major site at Kemps Creek in New South Wales was built on a vast footprint. The site spans 187,000 square metres—roughly 25 rugby league fields—with a building size of 66,000 square metres. At full capacity, it was designed to service about 229 stores across New South Wales and the ACT.

Cain framed the promise in plain operational terms: the new ADCs would process roughly twice the cases and hold roughly twice the pallets in about half the footprint of Coles’ existing distribution centres. He also argued the automation would materially improve safety for team members—shifting the work away from heavy manual handling. In his words, more than 90 per cent of cases processed in these centres would be handled by automation or ergonomic systems, eliminating almost 18 million kilograms of manual handling each week across the supply chain.

And Coles claimed it wasn’t just theoretical. The first ADC opened in Redbank, Queensland in May the prior year and had since processed more than 140 million cartons. Coles said customers in Queensland and Northern New South Wales were seeing a 20 per cent improvement in availability compared to other stores.

The automation push kept going. On 31 October 2024, Coles announced it would invest $880 million to build a new ambient ADC in Truganina, Victoria, in partnership with WITRON Australia Pty Ltd. Together with the New South Wales and Queensland facilities, Coles said this would deliver full automation of its ambient distribution centre network across Australia’s eastern seaboard.

While the infrastructure was being rebuilt, leadership was changing too. On 1 May 2023, Leah Weckert became CEO and Managing Director of Coles Group—the first female CEO in the company’s history. Weckert had joined Coles in 2011 and held a string of senior roles across the group. Immediately prior, she was Chief Executive, Commercial and Express, leading the supermarkets business units and the Coles Express business. Earlier, she served as CFO and played a leadership role in the 2018 demerger. Her resume inside Coles also included Strategy, People & Culture, Victoria Operations, and Merchandise, Strategy and Innovation. Before Coles, she worked at McKinsey & Company and at Fosters Group in Strategy and Business Development.

But the modern era came with a darker companion: escalating scrutiny. On 23 September 2024, the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission announced it had initiated separate legal proceedings against Woolworths and Coles in the Federal Court of Australia. The ACCC alleged both companies misled customers about discount pricing—through Woolworths’ “Prices Dropped” and Coles’ “Down Down” promotions—in breach of the Australian Consumer Law.

The allegation was specific: that prices on certain products were increased by at least 15 per cent for short periods, then promoted as if they’d been reduced—often to a level that was the same as, or higher than, the regular price before the temporary spike. The ACCC alleged the conduct involved 266 products for Woolworths across 20 months, and 245 products for Coles across 15 months.

In November 2024, Coles was also notified that a class action had been filed in the Federal Court alleging misleading conduct relating to the same products at issue in the ACCC matter. Coles said it was defending both the ACCC and class action proceedings. With both cases still at an early stage, Coles noted the outcome—and the total costs—remained uncertain.

Even with that legal cloud forming overhead, the underlying machine kept turning. In its results for the first half of 2025, Coles reported group sales revenue up 3.7 per cent to $23.035 billion, driven by a 4.3 per cent rise in supermarkets sales revenue to $20.629 billion. Earnings also increased: EBITDA from continuing operations (excluding significant items) rose 10.3 per cent to $2.045 billion, underlying EBITDA was up 12.5 per cent to $2.137 billion, and EBIT from continuing operations (excluding significant items) increased 5.0 per cent to $1.117 billion, with underlying EBIT up 8.9 per cent to $1.209 billion.

IX. The Duopoly Deep-Dive: Understanding Australia's Grocery Market Structure

Coles can’t be understood on its own. Its strategy, its economics, even its public controversies all make more sense when you zoom out and see the structure it operates inside: a duopoly that has come to define Australian grocery retail.

At the highest level, supermarket retailing in Australia functions like an oligopoly. Woolworths and Coles together account for about two-thirds of supermarket sales nationwide. ALDI sits well behind them at roughly 9 per cent, and Metcash—supplying many independent supermarkets—accounts for about 7 per cent.

Australian government officials have been blunt about what that means: “Australia has one of the most concentrated supermarket sectors in the world, with Coles and Woolworths together holding 65 per cent share of the market.” They also noted concentration isn’t unique to groceries—it has been rising across much of the economy, including banking, airlines, energy, and telecommunications.

The sharpest diagnosis came from the ACCC’s year-long inquiry into the supermarket sector, concluded in early 2025. It described the industry as “highly concentrated,” estimating Woolworths at about 38 per cent of supermarket grocery sales and Coles at about 29 per cent. And then it drew the key economic conclusion: this kind of market structure gives the two leaders limited reason to go to war on price.

The ACCC explained the logic in plain terms. In an oligopoly, firms tend to set prices based on how they expect rivals to react. If one major player cuts prices and expects the other to match, both may end up with lower margins and roughly the same market shares—so neither has much incentive to initiate broad-based discounting. In Australia, the ACCC said, that effect is reinforced by a second reality: the threat of meaningful new entry or rapid expansion is low.

That’s where the barriers come in—and they’re enormous. The ACCC pointed to ALDI as proof of just how hard it is to break in at scale: it took more than 20 years to reach its current share. That’s not a story of a slow-moving competitor. It’s a story of what it costs—in capital, time, and a differentiated offer—to build a national supermarket footprint in Australia.

Geography makes it tougher still. Australia is a continent-sized country with major distances between population centres, which makes logistics and distribution a core competitive advantage, not a back-office detail. Seasonal and climatic conditions vary dramatically between states, so transport and storage infrastructure directly affect availability and freshness. And disruption is part of normal operations—extreme weather events, bushfires, and rail outages are recurring challenges for any national chain. Layer on top the reality that Australia’s population may not be large enough to comfortably support a third national player at true scale, and the structure naturally tilts toward the two incumbents: Coles and Woolworths.

The ACCC also found evidence that this structure shows up in profitability. Its final report said Australian supermarkets appear highly profitable compared with international peers, with ALDI’s, Coles’ and Woolworths’ average EBIT margins “among the highest of supermarket businesses in relevant comparator countries.”

And while the ACCC acknowledged grocery prices have risen sharply over the past five financial years largely due to broad-based increases in the cost of doing business, it also said ALDI, Coles and Woolworths increased their product and EBIT margins over the same period. In other words: not all price increases simply passed through costs—some translated into additional profit.

That’s the tension at the heart of modern Australian grocery. Coles and Woolworths have what the ACCC called an “entrenched position in an oligopolistic market.” Together they account for about two-thirds of national grocery sales—making Australia’s supermarket sector more concentrated than many other developed countries, and ensuring that every debate about prices, suppliers, and fairness inevitably circles back to the same two names.

X. Porter's Five Forces and the Helmer Framework: Analyzing Coles' Competitive Moat

If you step back from the headlines and look at Coles like an investor would, the striking thing isn’t just its size. It’s how hard it is to attack. Two classic strategy lenses—Michael Porter’s Five Forces and Hamilton Helmer’s 7 Powers—help explain why Coles and Woolworths have held the field for so long, and why even well-funded challengers struggle to make a dent.

Threat of New Entrants: Very Low

Australia is an unforgiving place to build a national grocer from scratch. The obvious hurdle is money—stores, leases, staff, technology—but the real wall is logistics. To compete at scale, you need distribution infrastructure that can cover a continent, serve widely spaced cities, and still deliver fresh product reliably. With only about 26 million people spread across huge distances, the economics are brutal. ALDI’s long climb to roughly 9 per cent share is the case study here: it takes years of patient investment just to reach meaningful scale. And even Amazon Fresh, with global ambition and deep pockets, has struggled to gain traction in Australian grocery.

Bargaining Power of Suppliers: Moderate

Coles buys from around 8,000 suppliers, which reduces the leverage any single supplier can exert. But diversification isn’t the same as balance. The ACCC inquiry recorded many supplier complaints about tough terms and limited room to negotiate when the customer across the table controls so much of the route to market. In practice, that asymmetry tends to favour the retailer.

Bargaining Power of Buyers: Low to Moderate

Any one shopper has almost no negotiating power. But shoppers, in aggregate, can still discipline the system. ALDI’s growth and online price visibility put some pressure on pricing, and the cost-of-living backlash shows how quickly consumer frustration can translate into political and reputational consequences. That doesn’t set prices day to day, but it does create constraints that Coles can’t ignore.

Threat of Substitutes: Low

Australians have to eat, and supermarkets remain the default channel. Meal kits, restaurants, and specialty food retailers nibble around the edges, but they don’t replace the weekly shop for most households. They’re alternatives—rarely substitutes.

Competitive Rivalry: Moderate

Coles and Woolworths compete hard on presentation, promotions, and brand positioning. But the ACCC found limited evidence of the kind of sustained, aggressive price competition that would materially erode margins. That’s typical oligopoly behaviour: if you expect your rival to match broad price cuts, you’ve just reduced profitability for both sides without changing the market structure. So competition shows up everywhere—except, often, in all-out price war.

Helmer’s 7 Powers adds another layer—less about the “forces” around Coles, more about what protects it from inside.

Scale Economies: Coles’ purchasing power and operating scale are advantages smaller players can’t simply wish into existence. The automated distribution centre program is a tangible example: big efficiency gains, funded by big balance sheets, that are difficult to replicate without comparable volume.

Network Economies: Flybuys is a quiet giant in Coles’ ecosystem. Launched in 1994 as a joint venture between Shell, Coles Myer and National Australia Bank, it drew huge early interest, with a million Australian households joining within six weeks. By 2013, a consumer study found it was the most popular loyalty program in the country. Loyalty points, personalised offers, and the data loop all reinforce repeat behaviour.

Counter-Positioning: ALDI’s limited-range, private-label model is a real strategic counter-position. It’s not just cheaper; it’s structurally different. And because Coles and Woolworths are built around wide range, branded goods, and promotional cadence, neither has fully mirrored ALDI without undermining its own model—leaving ALDI with a durable niche.

Switching Costs: Grocery shopping looks frictionless—walk across the street and you’re “switched.” But in reality, habits are sticky. Store proximity, familiarity with layouts, saved preferences, and accumulated Flybuys points all create small frictions that add up. Coles Plus pushes that further for engaged members by layering in subscription-style benefits.

Branding: The McLeod-era reset rebuilt Coles’ brand around value, and “Down Down” remains one of the most recognisable slogans in Australian retail. In a duopoly, brand isn’t just about being liked; it’s about staying inside the customer’s default set.

Cornered Resource: Prime sites are scarce. Established shopping centres and high-traffic locations are effectively a finite resource, and the incumbents hold many of them. Coles and Woolworths have also pointed to land being held for long periods—sometimes due to rezoning, development timelines, or planning approvals—which further tightens the real estate bottleneck for any would-be national entrant.

XI. Bull Case and Bear Case for Investors

The Bull Case

The core bull case for Coles is simple: it sits in the middle of a defensive, everyday category, with a market position that’s hard to dislodge. People don’t stop buying groceries when the economy slows. And in Australia, the duopoly structure gives Coles a level of pricing stability that most retailers can only dream of. Add in the sheer capital and logistics required to build a credible third national player, and you get a business with a moat that isn’t flashy—but is very real.

Then there’s the big operational swing: automation. Coles has been pouring money into its automated distribution centres with the promise of structurally lower cost-to-serve. Management’s claim is blunt and compelling: “Our new ADCs can process twice the number of cases and hold twice the number of pallets in half the footprint compared to our current distribution centres.” If that plays out as planned, it should help protect margins even as wages, energy, and transport costs move around.

For income investors, Coles also has a straightforward appeal. It carried over a dividend framework from the Wesfarmers era, targeting an 80–90% payout ratio. In a business where demand is relatively steady, that kind of policy can translate into consistent cash returns—provided earnings remain durable and reinvestment needs don’t climb too far.

Finally, there’s a quiet tailwind: Australia’s population growth, driven in large part by immigration. That expands the total grocery basket over time. In a market with high barriers to entry, Coles is well placed to keep capturing its share of that growth without needing to win a bruising, margin-destroying battle every quarter.

The Bear Case

The big overhang is regulation and politics. Coles is already dealing with ACCC legal proceedings over alleged discounting practices, plus a related class action, all while the broader duopoly remains a live national issue. Opposition Leader Peter Dutton has flagged the idea of giving the ACCC “last resort” powers that could allow it to break up major supermarkets found to be abusing market dominance. A forced divestiture scenario is still a long way from today’s reality, but the direction of travel matters: rising political pressure can limit how aggressively Coles can price, promote, and negotiate—especially during a cost-of-living backlash.

Growth is another constraint. Same-store sales can only go so far in a mature category. Australians can’t endlessly eat more groceries, so long-run growth leans heavily on population increases and taking share. Population growth is incremental, and share gains tend to be hard-fought—usually meaning more investment, more promotions, or both.

Competitive pressure shows up at the margin, too. ALDI’s continued expansion and the steady march of private label can push the market toward value, where margins are typically thinner. If value-conscious shopping habits from the cost-of-living period persist, Coles may have to keep discounting to defend traffic—compressing profitability even if sales hold up.

And finally, there’s execution risk hiding inside the biggest “bull” initiative. Automation and supply-chain rebuilds are huge capital commitments. They’re meant to reduce cost and improve availability, but they also introduce complexity and operational risk. Meanwhile, the long-term spectre of tech-driven disruption hasn’t gone away. Grocery is slow to change, but Amazon’s ambitions are real, and meal delivery and prepared-food alternatives continue to grow. None of these are immediate existential threats—but they’re the kinds of forces that can quietly chip away at an incumbent’s economics over a decade.

XII. Key Performance Indicators for Investors

For investors trying to keep score as Coles moves through its post-demerger era, there are three numbers that matter more than almost anything else. They’re the closest thing you’ll get to a dashboard for whether the business is strengthening, treading water, or quietly giving ground.

1. Like-for-Like (Comparable Store) Sales Growth

This strips out the noise from opening new stores or shutting old ones and gets to the underlying question: are existing Coles stores selling more this year than last year?

During the McLeod turnaround, comparable sales growth was the proof point—quarter after quarter, Coles outperformed Woolworths. The key watch today is whether Coles can keep growing the core without relying on footprint expansion or one-off boosts.

2. EBIT Margin

Grocery is a game of tiny margins and huge volume. CEO Leah Weckert has framed Coles’ economics in a way that makes the point visceral: Coles makes about $2.60 in profit for every $100 spent in its stores. She has argued that this margin has stayed consistent over the past five years, did not rise with inflation, and is broadly in line with international supermarket margins.

For investors, this is the “everything at once” metric. It captures pricing discipline, cost control, shrink, wages, supply chain performance, and competitive intensity. The question is whether margins hold steady as automation ramps up—and as regulatory and legal costs start to bite.

3. Online Sales Penetration

Online grocery is no longer a side project. It’s become a real channel with very different economics. Online shopping is said to have grown about fourfold from pre-pandemic levels, moving from roughly 1–2% of supermarket retail sales to around 8–12% now.

Coles’ investments in Ocado-powered customer fulfilment centres are designed to make that shift profitable at scale, not just popular with customers. The KPI to watch isn’t simply whether online revenue grows—it’s whether Coles can grow online without diluting the economics of the overall business. Where the company discloses it, online profitability matters just as much as penetration.

XIII. Conclusion: The Eternal Dance

More than a century after George Coles opened a fixed-price variety store in working-class Collingwood, the company that grew out of it still stands as one of the two pillars of Australian grocery. The path from “Nothing over 2s 6d” to automated distribution centres moving mountains of stock isn’t just a corporate timeline. It’s a snapshot of how Australian commerce evolved: from counter service to self-service, from suburban expansion to national scale, from paper-based ordering to software-driven logistics.

If there’s a throughline to the Coles story, it’s that retail is never abstract. It lives or dies in execution.

The Wesfarmers era proved that even a deeply troubled retailer can be rebuilt—if new leadership is given both the mandate and the money to fix the basics, not just rebrand the symptoms. Ian McLeod didn’t “innovate” Coles back to relevance; he restored standards, rebuilt supplier trust, and made value feel real again for customers.

The Coles Myer years offered the opposite lesson. Empire-building can look like strength right up until it becomes distraction. When too many different businesses compete for attention, capital, and cultural oxygen, performance slips where it matters most. In Coles’ case, that was the supermarket floor—availability, freshness, and price perception.

And above it all sits the market structure. Australia’s grocery duopoly has proven stubbornly resilient, even as scrutiny rises. Scale, real estate, logistics, and habit combine to create an arena where disruption is hard, slow, and expensive. The ACCC can investigate, governments can threaten reform, consumers can vent their frustration—but week after week, most households still do the bulk of their shopping with one of the same two giants.

For investors, that’s the uncomfortable appeal. Coles is a defensive business: not a rocket ship, but a steady engine. Growth is naturally constrained, but the competitive position is durable, cash generation is strong, and the business has historically supported meaningful dividends. The legal and regulatory overhang—from ACCC proceedings to related class actions—adds uncertainty. But the underlying economics of selling everyday essentials at scale, in an oligopolistic market, remain intact.

And so the dance continues. Coles and Woolworths circle each other, matching moves on price and promotion, investing in parallel to protect their positions. Customers split baskets and chase specials. Suppliers negotiate hard, knowing the alternatives are limited. Shareholders, meanwhile, benefit from a structure that has endured for decades—criticised often, challenged occasionally, but rarely shaken.

George Coles couldn’t have pictured his Smith Street experiment becoming a modern, national machine serving millions of Australians each week. But he would recognise the idea at the centre of it all: keep the offer simple, run the operation efficiently, and make the savings feel real. In Australian grocery, that philosophy doesn’t end the battle. It’s what keeps you on the floor.

The duopoly that shapes a nation keeps dancing.

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music