Cochlear Ltd: The Bionic Ear That Changed Humanity

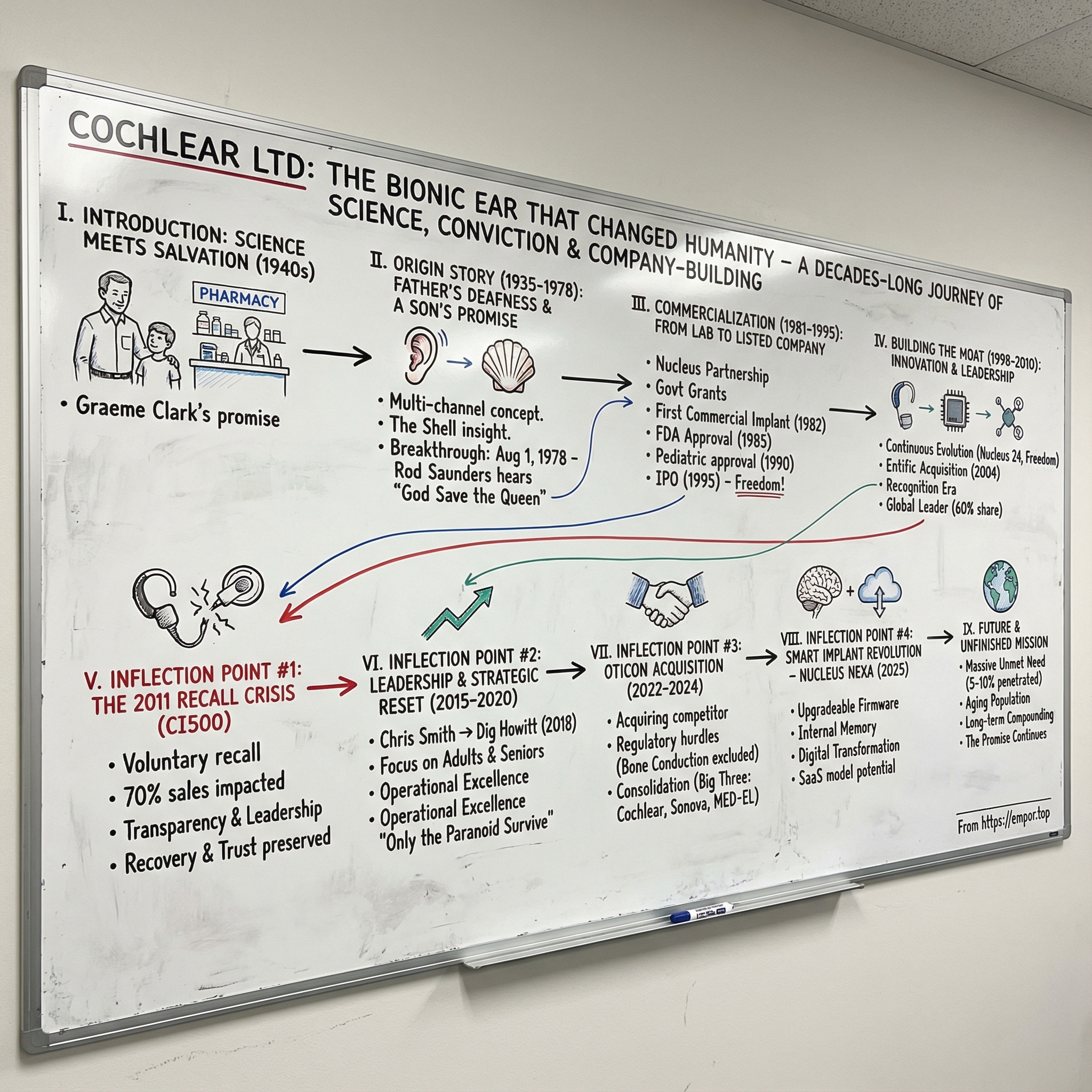

I. Introduction: Where Science Meets Salvation

Picture a father behind the counter of a modest pharmacy in Camden, a small town southwest of Sydney. It’s the 1940s. Customers lean in and speak softly, and Colin Clark leans forward in return, squinting, guessing, asking them to repeat themselves. His hearing aids help, but they don’t close the distance. Every missed word widens the gap between him and everyone on the other side of that counter.

Off to the side, his young son Graeme watches. Not just the mechanics of a transaction, but the human cost of silence: the frustration, the embarrassment, the isolation. He sees how badly his father wants to stay connected, and he makes a quiet promise that will end up consuming the next half-century of his life.

That promise becomes Cochlear Limited.

Cochlear started in 1981 as a subsidiary of Nucleus Limited, created to commercialize the multi-channel cochlear implant pioneered by Professor Graeme Clark at the University of Melbourne. What began as a university research effort grew into a global medtech leader, and its devices have enabled more than 700,000 people worldwide to hear.

On paper, it’s an extraordinary business: the leading cochlear implant manufacturer with around 60% global market share, with developed markets contributing about 80% of revenue—places where implants became the standard of care for children with severe to profound hearing loss. But the spreadsheet version misses the point. This company exists in moments that don’t fit neatly into metrics: a toddler turning toward a parent’s voice, or a grandparent catching a grandchild’s name clearly for the first time in years.

This story lives at the intersection of science and commerce. It’s about moats that take decades to build, crises that nearly end everything, and the ethical tension that comes with a technology that can “fix” something some communities don’t believe is broken.

II. The Origin Story: A Father's Deafness and a Son's Promise (1935-1978)

The Personal Catalyst

Graeme Clark was born on August 16, 1935, and grew up in Camden, a small town near Sydney. His father worked as a pharmacist, and he lived with sensorineural hearing loss. Day after day, young Graeme watched the same scene play out across the counter: customers spoke, his father leaned in, misheard, asked them to repeat themselves, and tried to stitch meaning together from partial sounds.

It wasn’t one dramatic moment. It was the accumulation of small ones. The awkward pauses. The strained smiles. The way conversations at social gatherings drifted on without his father, even when he was sitting right there. Clark learned early what hearing loss really costs: not just volume, but connection.

By the time he was 10, he told his local minister he wanted to become an ear doctor. He earned his medical degrees at the University of Sydney in 1957, trained as an ear, nose, and throat surgeon in Australia and the UK, and by 1967 returned to the University of Sydney. What could have been a career in medicine became something sharper: a personal mission with a target.

The Scientific Quest Against All Odds

In the mid-1960s, working as an ear surgeon in Melbourne, Clark came across a paper by Blair Simmons in the United States. The paper described something tantalizing: a profoundly deaf person could experience hearing sensations through electrical stimulation, but could not understand speech. That distinction mattered. It meant the nervous system could still be reached. The question was whether it could be reached with enough precision to turn sensation into language.

In 1967, Clark began researching an electronic, implantable hearing device: a cochlear implant. He did it into a wall of opposition. The prevailing view in the 1960s, captured by U.S. hearing physiologist Merle Lawrence, was blunt: “Direct stimulation of the auditory nerve fibres with resultant perception of speech was not feasible.”

And the criticism wasn’t polite. Clark later recalled being dismissed as “that clown Clark.” One colleague reportedly warned he would kill a patient. But he kept going, because the problem wasn’t theoretical to him. He’d watched what silence did to a person.

The science was brutal, too. The cochlea is tiny—snail-shell-shaped, buried deep in the ear—and inside it are roughly 15,000 delicate hair cells that convert vibration into electrical signals. Those signals pass along tens of thousands of nerve fibres to the brain. Replicating that with the electronics of the era sounded like science fiction.

Clark’s early work at the University of Sydney focused on electrical stimulation of the auditory nerve fibres. Over time, his experiments pushed him toward a defining conclusion: a single electrode wouldn’t be enough. To manage severe-to-profound hearing loss and get beyond “sound” to “speech,” the device would need multiple channels—multiple electrodes—stimulating different parts of the cochlea to represent different frequencies. It was more complex, harder to build, and harder to implant. It was also the only approach with a real chance of working.

The Shell on the Beach

One problem kept haunting the project: even if you could build a multi-channel device, how do you place an electrode array into the cochlea’s spiral without destroying the fragile structures you’re trying to stimulate?

The clue arrived away from the lab. Walking on a beach, Clark picked up a seashell with a spiral shape that reminded him of the cochlea. He noticed something simple and profound: when a blade of grass was inserted, it naturally followed the shell’s curves. It didn’t fight the spiral; it flowed with it.

That image became the design principle—an electrode array that was tapered and flexible, able to thread through the spiral gently instead of forcing its way in like a rigid probe.

The insight didn’t magically solve the rest. Funding was thin, institutional support was limited, and skeptics were still loud. Clark and his team pushed forward with what they could gather, and crucial early support came from public telethons run by philanthropically minded television proprietors—an unconventional funding source for a medical breakthrough, but a vital one.

The Breakthrough: August 1, 1978

On 1 August 1978, at the Royal Victorian Eye and Ear Hospital in Melbourne, Clark implanted a prototype multi-channel cochlear implant into Rod Saunders.

Saunders was 46, a hardware store manager who had lost his hearing in a car accident two years earlier. He lived with relentless tinnitus, a constant hissing that filled the space where the world used to be. Clark’s goal wasn’t a miracle. It was proof: proof that a multi-channel implant could deliver useful information to the brain.

The atmosphere around the surgery, Clark later said, was “a bit of bedlam.” Engineers and staff scrambled through last-minute checks and tests. The operation itself took nine hours. When Saunders woke up, the implant was in place—but still silent. The external electronics that would activate it wouldn’t be tested until later.

When the day came, the first two tests failed because of equipment problems. On the third attempt, the team found the issue: a loose connection in the speech processor. They fixed it, turned the electrical current up, and Saunders heard something emerge from beneath the tinnitus.

To see whether he could distinguish different tones and stimulation rates, the team played “God Save the Queen.” Saunders recognized it immediately, stood to attention—and in the motion, pulled out his leads. After he sat down and reconnected, they tried again with “Waltzing Matilda.” Saunders sang along.

That Christmas-time test was the confirmation: they had crossed the line from theory to functioning technology. Saunders could regain at least some ability to comprehend speech.

Clark later admitted what he did next wasn’t “very Australian.” He walked into the next room and burst into tears of joy.

And this is why the origin story isn’t just inspirational—it’s strategic. In choosing the multi-channel path early, Clark didn’t just build a better device. He set the direction of the entire category. Competitors would eventually have to converge on the same architecture, because speech understanding demanded it. The technological foundation laid in 1978 became the platform the industry would build on for decades.

III. Commercialization: From Lab to Listed Company (1981-1995)

Government Backing and the Nucleus Partnership

A successful surgery is not a product. Turning Clark’s breakthrough into something you could manufacture, sell, support, and improve would take industrial muscle and real money—two things a university lab simply didn’t have.

That’s where Paul Murray Trainor enters the story, a builder of Australian medtech businesses and, quietly, one of the key catalysts behind the bionic ear becoming real. Trainor had founded Nucleus Limited in Sydney in 1965 after acquiring the X-ray sales and service company Scientific & General. Over time, Nucleus became a kind of incubator for high-stakes medical technology: pacemaker maker Telectronics, cardiac monitor and defibrillator manufacturer Medtel, and eventually the cochlear implant venture that would become Cochlear.

Trainor’s playbook was straightforward and unusually effective: use proven, cash-generating medtech—especially pacemakers—to fund ambitious new bets. Telectronics itself started with almost mythic startup energy, making pacemakers in a room above a spaghetti shop in suburban Sydney in 1964. By the 1980s, under Nucleus ownership, it had grown to about 17% of the global pacemaker market. That cash flow became oxygen for the cochlear implant effort.

Then came the push that moved the bionic ear from “promising science” to “commercial program.” In 1981, Trainor and the Nucleus group received an AU$4 million Federal Government grant to begin commercial development of the multi-channel cochlear implant—support from the Fraser government that helped Australia bet on its own research. The grants were staged with milestone conditions, designed to bridge the riskiest part of the journey: the gap between “it works in a hospital once” and “it can be made reliably, at scale.”

The early device made the bet Clark had made years earlier: more channels, more information, more potential for speech understanding. It combined an implant and an external speech processor, with 22 electrodes sheathed in silicone—an order of magnitude more than some early competing approaches, like 3M’s two-electrode design. But hardware wasn’t the whole story. The other advantage was the signal processing: turning sound captured by a microphone into patterns of electrical stimulation, then helping early recipients learn how to interpret those patterns as speech. This wasn’t just a device you installed; it was a system you taught the brain to use.

The First Commercial Implant

In 1982, the project crossed a new threshold: not simply “an implant,” but a commercial cochlear implant. That milestone is credited to a tight collaboration among the University of Melbourne, the Royal Victorian Eye and Ear Hospital, and Nucleus, the biomedical company that would become Cochlear Limited.

That year, 37-year-old Melbourne man Graham Carrick became the first commercial recipient of a Cochlear Nucleus implant. When it was switched on, he waited through what he described as 15 nerve-wracking minutes of nothing. And then—sound.

“But then it hit me,” Carrick said. “I heard a ‘ding dong’… ‘bloody hell!’ To get this sound was fascinating and mind boggling.”

It’s easy to read that as a nice anecdote. For Cochlear, it was something more: proof that this could leave the lab and enter the world.

FDA Approval: The Gateway to Scale

If Cochlear was going to become a global leader, it would have to win in the United States. The American market would decide whether the bionic ear became the standard—or stayed an impressive Australian experiment.

Worldwide trials followed. In October 1985, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration approved the device for general use in adult patients. It was a defining moment: not just validation, but the opening of the biggest and most influential healthcare market on earth.

The next leap was even bigger. In 1985 and 1986, Clark performed cochlear implant surgeries on the first children—one aged 10 and another aged five. Those early pediatric cases helped pave the way for FDA approval for children 17 and under in 1990.

Over time, the implications became impossible to ignore. Adult implantation could restore access to sound and speech. But children implanted early could develop speech and language alongside their hearing peers. By 2007, it had become clear that deaf children could develop speech and language at normal rates if they received a cochlear implant early in life. That difference in outcome is what turned pediatric implantation into standard of care for severe-to-profound hearing loss in developed markets—and it became a durable engine for adoption.

The IPO: From Pacific Dunlop's Wreckage

The ownership structure behind the technology now became the next plot twist. In 1988, on Trainor’s retirement, the Nucleus business was sold to the Pacific Dunlop group. Cochlear—born as part of Nucleus—came along for the ride.

Pacific Dunlop’s story became a cautionary tale in conglomerate ambition. The company moved Telectronics pacemaker manufacturing to the United States, where inherited Cordis pacemaker leads caused catastrophic failures. Patients were harmed, reputations were destroyed, and the medical business imploded.

But in the wreckage, Cochlear survived. When Pacific Dunlop was split up, Cochlear emerged as its own company and listed on the ASX in 1995—essentially rescued, then set free.

That IPO was both liberation and opportunity. No longer tied to a struggling conglomerate, Cochlear could invest on its own terms: in manufacturing, clinical evidence, surgeon training, and the next generation of technology. Over the long arc, public markets rewarded that focus: from around $2 AUD in the late 1990s to over $260 AUD today, an extraordinary example of long-term compounding.

And importantly, it marked the end of Cochlear’s origin phase. The invention had become a business. Now it needed to become a machine.

IV. Building the Moat: Product Innovation and Market Leadership (1998-2010)

Continuous Product Evolution

The cochlear implant business has a peculiar characteristic that makes it unusually powerful: the implant is designed to stay in the body for life, but the external technology keeps getting better. That means a recipient might get implanted once, then upgrade sound processors and accessories over the years as the software and hardware improve. As Cochlear’s installed base grew, so did that recurring stream of upgrades and support.

The product cadence mattered, too. In 1998, the FDA approved Cochlear’s first Nucleus 24 family implant, the CI24M. It introduced a practical breakthrough: a removable magnet. That sounds minor until you remember what it unlocked—MRI scans without needing surgical magnet removal. For recipients, it was a huge quality-of-life improvement. For Cochlear, it was another example of how small, thoughtful engineering choices could widen the gap versus competitors.

Then in 2005 came FDA approval for the CI24RE “Freedom” implant. It brought improved power efficiency and better sound processing—exactly the kind of step-change that keeps users engaged with the platform and keeps clinicians confident they’re recommending the best available system.

And the CI24RE line didn’t just improve performance in the moment; it was designed to age well. It introduced a new integrated circuit that increased capability and future-readiness, including features like AutoNRT, multiple stimulation modes, and native compatibility with the Nucleus 5 Sound Processor. In a category where outcomes and trust compound over decades, this kind of forward compatibility isn’t a nice-to-have. It’s part of the moat.

Strategic Diversification: The Entific Acquisition

In 2004, Cochlear expanded beyond cochlear implants by acquiring Entific Medical Systems, a Swedish company best known for bone-anchored hearing aids for conductive hearing loss.

Strategically, it was clean. Bone-anchored systems serve a different type of hearing loss than cochlear implants, but they live in the same clinical world—ENT surgeons, audiologists, familiar reimbursement and regulatory pathways. Cochlear wasn’t starting from scratch; it was extending its reach through channels it already knew how to serve, with products it already knew how to support.

The Recognition Era

Cochlear was named Australia’s most innovative company by the Intellectual Property Research Institute of Australia in 2002 and 2003, and later was recognized by Forbes as one of the world’s most innovative companies in 2011.

By 2010, the result was clear: Cochlear had become the global leader in cochlear implants. Clark’s multi-channel bet wasn’t just validated—it had become the standard architecture for the category. Competition was real, but Cochlear’s edge was multi-layered: deep clinical evidence, long-built surgeon relationships, manufacturing know-how, and a steady drumbeat of product improvement that made switching away feel risky for clinicians and unnecessary for patients.

V. Inflection Point #1: The 2011 Recall Crisis

The Most Critical Moment in Company History

On September 12, 2011, Cochlear hit the kind of moment that separates great medtech companies from footnotes.

That day, Cochlear announced a voluntary recall of all Nucleus CI500 implants after reports that some devices were shutting down. CEO Chris Roberts said the company would stop manufacturing the CI500 line entirely—despite the fact that it represented roughly 70% of Cochlear’s implant unit sales for fiscal 2011.

Just sit with that for a second. Cochlear wasn’t pulling a niche product. It was yanking its flagship platform off the market.

In an industry built on surgeon confidence and patient trust—and where “failure” can mean another surgery—this wasn’t a bad quarter. It was an existential threat.

Complicating things, the company said that while less than 1% of CI512 implants had failed since the CI512 launched in 2009, Cochlear had identified a recent uptick in failures. Even a small change in reliability trends can trigger panic when the product lives inside someone’s head.

The Technical Failure

At the center of the recall was a manufacturing problem that produced tiny cracks—small enough to be invisible, big enough to matter. Those microcracks compromised the implant’s seal, allowing moisture to enter over time and eventually short out electronic components.

This kind of breakdown is especially cruel because it doesn’t announce itself dramatically. The implant can work fine, day after day, until one day it doesn’t. For the recipient, the system just stops—and the fix isn’t a software update or a replacement part. It’s surgical reimplantation.

The failure mode was a hermeticity failure: the titanium case is supposed to be perfectly sealed. If the seal is even slightly compromised, moisture can seep in over months or years and slowly kill the electronics.

The numbers that surfaced were alarming. In one reported set, 122 implants in the Nucleus N5 CI500 series translated into a 9.8% cumulative failure percentage—far above Cochlear’s historical norms, and far beyond what surgeons or patients considered acceptable.

Leadership Through Crisis

What Cochlear did next mattered as much as what went wrong.

Instead of downplaying the issue or dragging the investigation behind closed doors, Roberts went public and went direct. “In an abundance of caution and with our recipients in mind,” Cochlear issued a voluntary recall of the Nucleus CI500 range while it investigated further.

At the time, the company said the exact cause of the malfunction—and the full scope—was still unknown. It also noted that no patients had suffered injuries from the failures. But Cochlear made the decision that the real risk wasn’t only the devices already failing. It was allowing more failures to accumulate and permanently damage the brand.

Manufacturing of the CI500 line stopped while the company evaluated the cause. And operationally, Cochlear did something that feels obvious only in hindsight: it stepped back to the prior-generation CI24RE implant as a bridge, buying time until a replacement platform could be launched in 2013.

In retrospect, the CI500 line ended up with a cumulative survival percentage of 88.70%—the lowest of any Cochlear product line. That’s not just a data point. It’s a scar.

Recovery and Lessons Learned

Recovering meant fixing the technical root cause and repairing relationships at the same time.

Cochlear poured effort into understanding what had gone wrong in the manufacturing process—particularly around the brazing process tied to the hermetic seal—and then tightened manufacturing protocols, strengthened quality systems, and increased scrutiny across production.

But the more delicate task was preserving belief. In medtech, your product doesn’t compete on marketing; it competes on outcomes, and on whether clinicians trust you with their patients.

Cochlear’s transparency helped it hold that trust. Competitors had gone through similar crises with worse outcomes—Advanced Bionics’ 2010 recall left lasting reputational damage—but Cochlear largely kept its market leadership intact.

The market still punished the company immediately. Cochlear’s stock dropped 27% on the recall announcement. But the episode also showed the other side of the medical device business: when a company protects its credibility with surgeons and recipients, it preserves the only asset that really compounds.

VI. Inflection Point #2: Leadership Transition and Strategic Reset (2015-2020)

The Chris Smith Era Begins (Briefly)

After steering Cochlear through the recall and the recovery, Chris Roberts handed over the reins.

Chairman Rich Holliday-Smith announced that Chris Smith would become Chief Executive Officer and President effective September 1, 2015. Roberts, who had been CEO and President since February 1, 2004, stepped down at the end of August.

Roberts brought more than 40 years of experience in international medical devices, and his 11-year run at Cochlear was a compounding machine: revenue grew from AUD$285 million to $820 million, and the share price quadrupled.

The board’s parting message made the subtext clear: this was a leader leaving at the top of his game. “Dr Roberts leaves Cochlear with the Board's best wishes and thanks. He has done a remarkable job in the more than 11 years as CEO. His commitment to innovation has helped maintain Cochlear as global market leader.”

Smith’s tenure, however, didn’t last. By January 2018, he was replaced by Dig Howitt. But even in that short window, the company’s strategic center of gravity was shifting—and it would define Cochlear’s next leg of growth.

Focus on Adults and Seniors: A New Growth Vector

For decades, the cochlear implant story had been anchored in pediatrics: children born deaf, or who lost hearing early, getting implanted and gaining access to spoken language. That remained mission-critical. But as a growth strategy, Cochlear could see the limits.

The numbers told a simple story. Adult and senior recipients were growing strongly—up around 10% for the half—while the children segment declined modestly, as expected.

The pivot was driven by demographics more than competition. The World Health Organization estimated more than 430 million people globally had disabling hearing loss, projected to reach 700 million by 2050. Most of that growth sits with adults, as hearing declines with age.

And yet the market was dramatically underpenetrated: fewer than 5% of people with severe or higher hearing loss were treated with an implantable solution. Cochlear implants were long established as standard of care for children in developed markets, but qualifying adults adopted them at far lower rates.

That gap was simultaneously Cochlear’s biggest opportunity and its hardest problem. Adults have to acknowledge a decline they may be in denial about. They have to navigate stigma. They have to work through healthcare bureaucracy and reimbursement. And they have to say yes to an irreversible surgery. Every one of those steps adds friction, and friction is what keeps markets small.

Dig Howitt Takes the Helm

In January 2018, Dig Howitt was appointed Chief Executive Officer and President of Cochlear Limited.

Howitt had joined Cochlear back in 2000 and rose through roles spanning Manufacturing and Logistics and the Asia Pacific region. Before Cochlear, he worked as a consultant at the Boston Consulting Group and held general management roles in Boral and Sunstate Cement.

In other words: he was built for the job Cochlear needed at that moment. Engineering and operations instincts, global perspective, and nearly two decades inside the business before taking the top seat. Under Howitt, the emphasis was clear—operational excellence, continued investment in R&D, and disciplined market expansion, especially into that massive adult and seniors segment.

Howitt summed up the mindset with a line that could’ve been written for medtech: “The thing that comes into my head is the Andy Grove book from Andy Grove, the CEO of Intel—‘Only the Paranoid Survive’—always got to be using most of your time looking forward and saying, what is it that we're out to achieve?”

VII. Inflection Point #3: The Oticon Acquisition and Consolidation (2022-2024)

Acquiring a Struggling Competitor

In April 2022, Cochlear announced it would acquire Danish competitor Oticon Medical for A$170 million, after Oticon’s parent company, Demant, decided to exit the hearing implant business.

Demant’s statement was unusually candid. After a strategic review, it said it had agreed in principle to divest Oticon Medical to Cochlear for DKK 850 million (about $120 million USD). And then came the real point: Demant had been building this business since 2007 and investing heavily in implantable hearing solutions. But it concluded that becoming a global leader in hearing implants wasn’t achievable within a reasonable timeframe without “disproportionate” additional investment.

That’s the moat, explained in plain language. In cochlear implants, you don’t win with a decent product and good marketing. You win with scale, long-term reliability, clinical evidence that stacks up year after year, and surgeon and audiology relationships that take decades to earn. Demant had the resources and the brand in hearing aids. It still couldn’t make the leap.

Regulatory Complexity

The deal then ran into a very specific kind of regulatory buzzsaw: bone conduction.

On 22 June 2023, the UK’s Competition and Markets Authority found the merger could substantially lessen competition in the supply of bone conduction solutions in the UK. The result was a partial block: Cochlear could not acquire Oticon Medical’s bone conduction solutions business.

Australia’s regulators landed in the same place. As ACCC Commissioner Stephen Ridgeway put it, “The transaction has now been changed to remove the bone conduction solutions business, which addresses the significant concerns the ACCC had in relation to bone conduction solutions.”

So the compromise was clean and surgical. Cochlear would take the cochlear implant business, but the bone-anchored hearing systems would stay out of the deal. Competition concerns addressed, core asset preserved.

Integration and Strategic Implications

On May 21, 2024, the transaction closed, completing the divestment of Oticon Medical’s cochlear implant business from Demant to Cochlear.

Oticon Medical, founded in 2009, was estimated to have around 20,000 cochlear implant users and about 55,000 acoustic implant users.

By this point, the economics of the situation were undeniable. The transaction ultimately completed at a zero headline purchase price, with Cochlear saying, “We welcome Oticon Medical's cochlear implant customers to Cochlear and remain committed to supporting the long-term hearing outcomes of these 20,000 patients.”

Cochlear expected integration costs in FY24 of around $30 million pre-tax, primarily related to restructuring.

That “zero” headline price is doing a lot of work. It signals a business that wasn’t just subscale—it was losing money. Cochlear wasn’t paying for a high-growth asset; it was stepping in to take on the obligation that matters most in medtech: supporting implanted patients for the long haul. But in exchange, Cochlear gained an installed base that will need service, support, and future processor upgrades over decades.

Strategically, it also tightened an already concentrated market. Cochlear implants effectively remained a three-player arena: Cochlear, Sonova’s Advanced Bionics, and MED-EL. With Cochlear at roughly 60% share, competition stayed focused where it always has in this category—on outcomes, reliability, and platform longevity—not on price tags.

VIII. Inflection Point #4: The Smart Implant Revolution – Nucleus Nexa (2025)

The Paradigm Shift

On July 8, 2025, Cochlear announced U.S. Food and Drug Administration approval for the Cochlear Nucleus Nexa System, which the company described as the world’s first smart cochlear implant system.

What makes Nexa different isn’t a sleeker external processor or a modest bump in sound quality. It’s the idea that the implant itself is no longer frozen in time.

Historically, the implant has been static hardware. The innovation lived outside the body, delivered through new sound processors that recipients could upgrade every few years. Nexa changes the rules: the implant runs its own firmware, and that firmware can be upgraded. In practical terms, it means future improvements can come not just through whatever you wear on your ear, but through the implant under the skin too.

Cochlear framed it in terms anyone can understand: like a smartphone, the implant can be updated to enable new features and access future innovations. For a technology that’s designed to be implanted for life, that’s a major shift in what “future-proof” can actually mean.

From Hardware to Software-as-a-Service

Nexa also introduces another important capability: internal memory. That allows a recipient’s unique hearing settings—often called MAPs—to be securely stored in the implant and transferred to another Nucleus Nexa sound processor if needed.

On the surface, this solves a painfully real problem. External processors get lost, damaged, or broken, and that disruption can be especially common in children. Built-in memory makes getting back to hearing faster and simpler.

But zoom out and you can see the strategic implication. Once the implant has upgradeable firmware and onboard memory, it starts to look less like a one-time medical device and more like a long-lived platform—something Cochlear can keep improving over time.

The system pairs with the new Nucleus 8 Nexa Sound Processor, which Cochlear described as the world’s smallest and lightest, with all-day battery life and algorithms that adapt power use to individual needs. Along with a connected digital ecosystem, it’s designed to keep users connected to sound even when the real world happens—like a processor being lost and replaced.

For investors, the direction is obvious. If Cochlear can attach value to firmware updates and digital features—through subscriptions, service plans, or premium unlocks—it nudges the business model away from episodic hardware cycles and toward recurring digital revenue, layered on top of an already sticky installed base.

Digital Transformation Investment

Behind the scenes, this kind of connected platform takes more than great industrial design. It takes infrastructure.

Cochlear said it expected to invest around $250 million overall—about $100 million more than its previous estimate—driven by an expanded program scope. The final phase, the company said, would focus on its core ERP, underlying data, and manufacturing systems.

That’s not just a back-office refresh. It’s the plumbing for a connected care ecosystem: data moving reliably, systems talking to each other, and the operational backbone required for remote support, monitoring, and continual improvement. It’s the kind of investment you make when you’re preparing to ship not just devices, but a long-running digital experience.

As Xinyu Li, General Manager for Greater China at Cochlear, put it: “There are more than 10 years of research and development advancements built into the new Nucleus Nexa System.”

IX. Competitive Landscape and Market Dynamics

The "Big Three"

Cochlear implants aren’t a sprawling, chaotic market. They’re a tight, high-stakes arena dominated by three companies: Cochlear (Australia), Sonova (Switzerland, through Advanced Bionics), and MED-EL (Austria). Together, they account for about 85% of global share—an unusually concentrated structure for a medical device category.

That concentration makes sense. This isn’t a gadget you can try for a week and return. It’s a surgical platform decision, made by surgeons and audiologists, paid for by healthcare systems, and then lived with for decades by the recipient. That kind of market naturally rewards trust, track record, and scale.

Cochlear sits out front at around 60% share. It benefits from first-mover advantage, the largest installed base, and the deepest stack of clinical evidence. It also operates globally across the Americas, EMEA, and Asia Pacific, with products available in over 180 countries. And it continues to invest heavily in staying ahead: in the fiscal year ending June 30, 2024, it allocated more than USD 270 million—about 12% of revenue—to research and development.

Sonova’s Advanced Bionics is the second force at roughly 25% share. Sonova is a serious technology investor too: in 2023–2024 it allocated USD 263.32 million, around 6.5% of total revenue, toward advancing new technologies. It has also strengthened its competitive posture through recent regulatory approvals, including FDA approval expanding the Marvel CI product line and features.

MED-EL rounds out the big three at about 15% share. The privately held Austrian company operates in 137 countries and has a network of more than 30 regional offices. Its brand is closely associated with electrode innovation, including a reputation for particularly flexible arrays.

Market Size and Trajectory

The global cochlear implants market was valued at about $2.58 billion in 2023, grew to $2.80 billion in 2024, and is projected to reach $4.73 billion by 2030—about a 9.2% compound annual growth rate.

The drivers here are structural, not cyclical. Technology keeps improving, and the underlying need keeps expanding. The World Health Organization estimates that more than 430 million people worldwide live with disabling hearing loss.

And yet, penetration remains low. It’s estimated that only about 5–10% of people who could benefit from a cochlear implant actually have one—largely because of cost and access. That’s the paradox at the heart of the category: huge medical need, proven clinical impact, and still millions of potential candidates living without treatment because the upfront path is too hard to reach.

The Business Model: Why After-Market Matters

Most of the company’s income comes after the surgery, not at it—through processor upgrades, accessories, batteries, and related services.

That’s the business model in a sentence. The implant itself is, economically, the beginning of the relationship. The external technology evolves, and recipients typically upgrade processors over time. Over the life of a recipient, the value of that relationship can far exceed the initial implant sale.

Cochlear has captured the reality—and the responsibility—of that model plainly: customers depend on their implant for hearing for life, and Cochlear can only support them long-term if it remains a successful business for their lifetime.

This creates one of the strongest retention dynamics in healthcare. Once someone is implanted with a Cochlear device, they are effectively a Cochlear customer for life—switching brands would require reimplantation surgery. The installed base compounds: each new implant isn’t just a unit sold, it’s another decades-long customer relationship added to the platform.

X. Strategic Analysis: Understanding Cochlear's Competitive Position

Porter's Five Forces Analysis

Threat of New Entrants: LOW

Cochlear makes the barrier to entry visible in its own income statement. Year after year, it spends roughly 12% of revenue on R&D, pushing improvements in outcomes, lifestyle features, reliability, and connectivity.

Since listing, Cochlear has invested more than $3 billion in R&D and built a portfolio of more than 2,300 patents and patent applications worldwide. But the real wall isn’t just patents or spend. It’s the combination: decades of clinical evidence, regulatory timelines that can stretch five to ten years or more, and surgeon relationships earned through thousands of training sessions and long-running collaborations.

The practical implication is brutal for any would-be challenger: you’d need to spend billions over a decade with no guarantee you end up with a product that surgeons trust. Demant’s experience with Oticon Medical made that point the hard way.

Bargaining Power of Suppliers: MODERATE

Cochlear relies on specialized, medical-grade components—titanium cases, platinum-iridium electrodes, and biocompatible polymers—often sourced from a limited supplier base. That concentration creates leverage for suppliers and risk for Cochlear, especially around launches and demand spikes.

Cochlear’s response has been to carry more inventory ahead of new product cycles, hold higher safety stock for critical components, and diversify manufacturing across Sydney, Kuala Lumpur, and other facilities. It reduces the risk, but it can’t eliminate the fundamental reality: these are not commodity parts, and there aren’t endless qualified vendors.

Bargaining Power of Buyers: MODERATE-HIGH

Cochlear’s revenue is heavily weighted to developed markets, which contribute about 80% of group revenue, and where cochlear implants are standard of care for children with severe to profound hearing loss.

But in those markets, the buyers with real power are often not individual patients. They’re government health systems and insurers. Reimbursement policy can open a market—or quietly close it. If coverage isn’t there, adoption doesn’t happen at scale.

That said, the clinical evidence behind cochlear implantation is strong enough that in developed markets, major coverage disputes tend to be the exception rather than the rule.

Threat of Substitutes: LOW-MODERATE

For many people with mild-to-moderate hearing loss, hearing aids are the substitute. And modern hearing aids keep getting better, even pushing further into severe hearing loss.

But they’re still solving a different problem. Hearing aids amplify sound. They can’t replace the cochlea’s hair cells when those cells are no longer functional, which is exactly where cochlear implants come in.

Looking further out, regenerative medicine is the theoretical disruptor: stem cell and gene therapy approaches that aim to regenerate cochlear hair cells and restore natural hearing. The catch is that these efforts remain early and preclinical, with commercialization likely more than a decade away and a low probability of success from that stage.

Competitive Rivalry: MODERATE

Competition in cochlear implants is intense, but it’s not a race to the bottom on price. Providers care most about clinical performance, long-term reliability, and the quality of post-surgical support.

So differentiation tends to show up in things like remote programming, MRI-compatible magnets, and service models built around outcomes. With three major players competing primarily on technology and results, market share moves slowly, and the industry avoids the kind of destructive pricing cycles that crush profitability.

Hamilton's Seven Powers Framework

1. Scale Economies: STRONG

Cochlear operates globally across the Americas, EMEA, and Asia Pacific, with products available in over 180 countries.

With roughly 60% global market share, Cochlear can spread R&D and fixed operating costs across far more unit volume than its nearest competitor. That scale advantage compounds: more volume supports more investment, which supports better products, which supports more volume.

2. Network Effects: MODERATE

Cochlear’s network effects are subtle, but meaningful. Surgeons trained on Cochlear systems tend to keep using what they know. Audiologists build deep familiarity with Cochlear’s fitting software. Meanwhile, clinical evidence accumulates with the installed base, giving Cochlear a larger pool of outcomes data than competitors.

None of this is a consumer-style network effect. But in a clinical workflow business, professional familiarity and evidence density create real gravitational pull.

3. Counter-Positioning: STRONG (historically)

From the beginning, Cochlear’s bet on multi-channel implants while others pursued simpler single-channel designs was classic counter-positioning: harder, riskier, more expensive, and ultimately the architecture that speech understanding demanded.

Today, Nexa’s firmware-upgradeable implant architecture hints at a similar dynamic. If competitors want to match that capability, they may need to redesign their implants from the ground up, not just iterate their external processors.

4. Switching Costs: VERY STRONG

This is the core moat. Once someone is implanted, switching brands isn’t like changing phones. It requires major surgery.

In normal circumstances, that means a Cochlear recipient remains a Cochlear customer for life. The implant is designed to last decades, and the relationship continues through ongoing support, accessories, and processor upgrades.

5. Branding: STRONG

For surgeons, audiologists, and patients researching their options, Cochlear has become synonymous with cochlear implantation. The company effectively shares its name with the category, which is an unusually powerful position in medtech.

6. Cornered Resource: MODERATE

Cochlear’s portfolio of more than 2,300 patents and patent applications helps protect specific innovations, even though the foundational multi-channel concept is now off-patent.

Just as important is what you can’t file as IP: decades of clinical relationships, collaborations with leading academic centers, and credibility with surgeon key opinion leaders. In this category, those relationships act like a scarce resource.

7. Process Power: STRONG

The last moat is one people outside medtech often underestimate: manufacturing.

Cochlear implants are still assembled under a microscope at the company’s factory on the campus of Macquarie University in Sydney. Implants are then sent into a small, sealed room for a critical step: a laser welder runs around the outside of the titanium implant case to create a hermetic seal that protects the electronics inside.

That kind of precision isn’t just craftsmanship. It’s accumulated know-how, quality control discipline, and process refinement built over more than 40 years. When your product has to perform inside the human body for decades, process power isn’t a nice-to-have. It’s the business.

XI. The Investment Case: Bulls and Bears

The Bull Case

Massive addressable market, tiny penetration. Even now, only about 5–10% of people who could benefit from a cochlear implant actually receive one. That’s an unusually long runway in medtech. If awareness rises, access improves, reimbursement expands, and emerging markets become more reachable over time, the category has room to grow for decades.

Demographics are doing a lot of the work. Hearing loss increases with age, and the world is getting older. Each year, the pool of adults and seniors with severe hearing loss gets larger—exactly where Cochlear has been pushing to expand adoption, and exactly where cochlear implantation has been steadily moving from “extreme measure” toward accepted standard care.

A dominant position in a tight market. Cochlear still sits at roughly 60% global share, in an industry where switching costs are about as high as they get. The installed base keeps compounding, clinician familiarity reinforces preference, and the Oticon Medical transaction only tightened an already concentrated market structure.

A business that keeps earning after the surgery. The implant may be a one-time procedure, but the relationship isn’t. Processor upgrades, accessories, and ongoing services create a durable, recurring stream of revenue from the installed base. And Nexa pushes that model further: if the implant itself can take firmware upgrades, Cochlear can keep delivering new value over time in a way that starts to resemble software economics layered on top of hardware.

A relentless R&D flywheel. Cochlear invests heavily to stay ahead—more than $270 million in R&D in the year ending June 30, 2024, around 12% of revenue. In a market where trust and outcomes compound, that spend isn’t just expense; it’s reinforcement. And with the largest share, Cochlear can spread those investments across more volume than anyone else.

The Bear Case

A premium price tag. Cochlear has often traded like a “best-in-class” compounder, and at roughly 42x earnings, the market is demanding it keep executing. That valuation doesn’t leave much room for stumbles—whether from a product cycle misstep, a slower adoption environment, or margin pressure.

Services can be lumpy. Services growth slowed after the launch of the Nucleus 8 Sound Processor in FY23. Expectations for FY25 shifted from modest growth to a single-digit decline. That’s a reminder of how upgrade cycles work: they’re real and recurring, but not perfectly smooth. When consumer spending tightens or recipients delay upgrading, revenue can wobble.

Reimbursement and regulation are always in the background. Cochlear doesn’t sell into a pure consumer market; it sells into healthcare systems. Government payers and insurers—especially in the U.S. Medicare system—can materially change demand and pricing if policies shift.

The long-dated existential threat. Stem cell and gene therapies remain distant and uncertain, but they sit out on the horizon as the “if this works, everything changes” scenario. A real breakthrough in hair-cell regeneration could, in theory, make implants obsolete.

Concentration cuts both ways. Developed markets still generate about 80% of Cochlear’s revenue. Growth in emerging markets has been slower than hoped, and volume-based pricing initiatives in China create ongoing pricing pressure—meaning expansion outside core markets may not be as profitable or as fast as investors would like.

Key Performance Indicators to Monitor

For investors tracking Cochlear, three metrics tend to matter most:

-

Cochlear implant unit growth: a read on overall category momentum and whether Cochlear is holding or gaining share. The company targets roughly 10% annual unit growth, broadly in line with market expansion.

-

Services revenue growth: the clearest window into installed-base monetization and the health of processor upgrade cycles. Strong services growth usually signals retention, satisfaction, and successful product launches.

-

Gross margin: Cochlear targets around a 75% gross margin. Sustained compression would be a warning sign—either rising manufacturing costs, pricing pressure, or a shift in mix.

XII. Conclusion: The Unfinished Mission

Back in Camden, New South Wales, Colin Clark’s hearing aids could amplify sound—but they couldn’t reliably deliver understanding. His son spent a lifetime trying to close that gap, and the bridge he built has now carried more than 700,000 people back into the world of hearing.

And still, the most important part of this story is what hasn’t happened yet.

A University of Melbourne study found that fewer than 10 per cent of adults who could benefit from cochlear implants ever receive them. Professor Graeme Clark has long argued that the technology can help people of all ages—including those who assume they’re “too old” to be candidates. The limiting factors are rarely the science. They’re access, awareness, cost, and the sheer friction of getting from “I’m struggling” to “I’m implanted.”

The need is staggering. Hundreds of millions of people worldwide live with disabling hearing loss, and most will never receive an implant—often because they don’t know it exists, don’t know they qualify, or can’t reach a system that will fund it.

For Cochlear, that reality is both mission and opportunity. As the world gets older and the hidden costs of hearing loss become harder to ignore, this Australian pioneer is positioned to do what it has always done: take world-class science, wrap it in world-class execution, and scale it to real lives.

Clark, now approaching his tenth decade, still works at the University of Melbourne, still pushing at the edges of what bionic technology can do. Meanwhile, the company he helped inspire has grown from a government grant and borrowed lab space into a $13+ billion enterprise—one that has changed the trajectory of countless families.

The next chapter is already taking shape: smart implants, cloud connectivity, and business models that may start to resemble software platforms as much as medical device sales. The moats are still there—switching costs, clinical evidence, surgeon relationships, manufacturing excellence—and they remain as hard to replicate as ever. The market, too, is still wide open.

Whether Cochlear keeps compounding value for shareholders will come down to execution: launching Nexa successfully, expanding the installed base, growing and smoothing the after-market engine, and holding off competitors who would love nothing more than to take share.

But even if you ignore the stock chart entirely, the core story doesn’t change. A son watched his father strain for connection, and decided that struggle didn’t have to be permanent. That single, stubborn mission—to give people back the sense that reconnects them to the world—still animates Cochlear Limited today.

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music