Charter Hall Group: Australia's Property Powerhouse

I. Introduction: The Quiet Giant of Australasian Real Estate

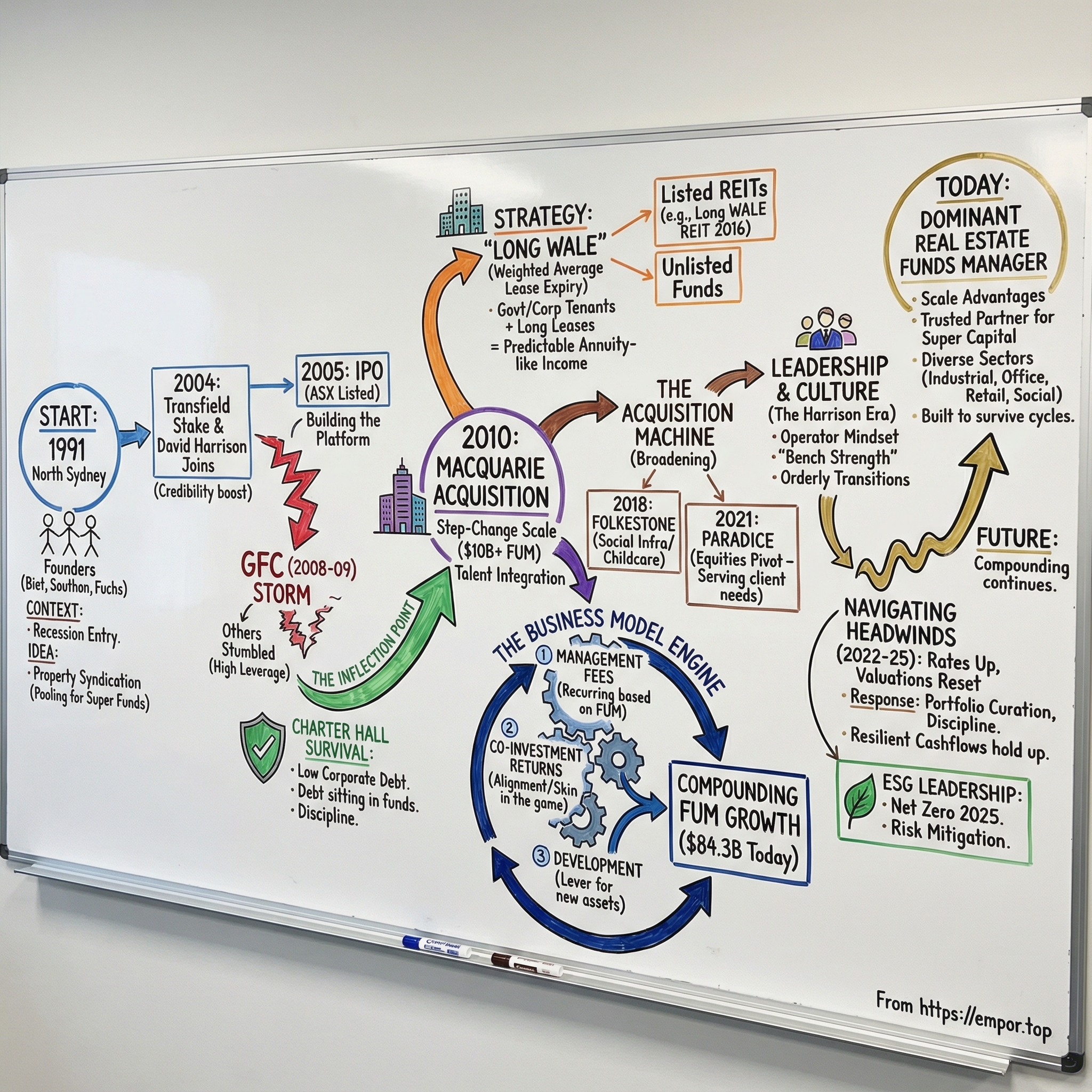

Walk through almost any major CBD in Sydney, Melbourne, or Brisbane and you’ll see the same cast of characters: towers of glass, government departments, big banks, blue-chip corporates. But behind a surprising number of those lobbies and lease agreements sits a company most Australians couldn’t pick out of a lineup: Charter Hall.

Westfield became famous by putting its name on shopping centres. Charter Hall did the opposite. It built influence without visibility—quietly assembling an empire of long-term tenants, institutional capital, and recurring fee income. Today, that platform stretches across more than 1,600 properties in Australia and New Zealand.

Charter Hall is Australia’s leading diversified property investment and funds management group, with $84.3 billion of funds under management. It uses that scale to find deals, structure investment vehicles, and manage assets across the core sectors that underpin the economy: Industrial & Logistics, Office, Retail, and Social Infrastructure. The pitch to investors is straightforward: steady income, disciplined risk, and portfolios built to hold up across cycles.

By 2022, IREI ranked Charter Hall as the largest real estate investment manager in Australasia by assets under management. That’s a serious achievement in a market where heavyweights like Goodman, Lendlease, and Dexus have been competing for decades. And it makes the origin story even more interesting: three entrepreneurs launching a property funds business in North Sydney in 1991, at a time when the market was bruised and confidence was scarce.

So here’s the question that matters: how did Charter Hall go from a relatively small fund manager when it listed on the ASX in 2005 to becoming the country’s largest diversified property funds manager? The pattern that emerges is consistent—disciplined strategy, big swings taken at exactly the right moments, and an unusually strong emphasis on alignment between Charter Hall, its investors, and its tenants.

The machine it built is also worth understanding. Charter Hall sits at the centre of a network: over 30 unlisted retail and institutional funds, plus three listed REITs—Charter Hall Long WALE REIT, Charter Hall Retail REIT, and Charter Hall Social Infrastructure REIT. The group primarily makes money by charging investment management and property services fees across those vehicles. It also co-invests alongside its capital partners, meaning some earnings come from rent and fund distributions, with development income playing a smaller role.

What follows is a walk through three decades of property cycles, opportunistic acquisitions, leadership transitions, and strategic pivots. And running underneath all of it is a distinctly Australian advantage: a superannuation system that steadily produces enormous pools of capital looking for a home—and a firm that learned, early, how to become the trusted manager of that money.

II. Founding and Early Vision: Three Entrepreneurs Bet on Australian Property (1991-2004)

On 10 May 1991, three founders unlocked the door to a small office in North Sydney and started Charter Hall. It was a gutsy moment to enter property. Australia was climbing out of recession, commercial values had been hammered, and the banks that had fuelled the excesses of the late 1980s were left nursing big losses.

Charter Hall was founded by André Biet, David Southon and Cedric Fuchs. They weren’t trying to build a flashy developer. They were building a platform. Biet served as Founder, Managing Director and CEO from the beginning through to the company’s listing in 2005, after which he retired.

If the timing looked awful, it also offered something every property investor eventually learns to respect: a cycle reset. Property runs in long arcs. Starting near the bottom can be the best place to build—if you can survive long enough to see the upswing.

The founders’ early focus was commercial property syndication, particularly for Australia’s growing superannuation funds. The idea was simple and powerful: create pooled vehicles that gave big institutions efficient access to high-quality assets they couldn’t, or didn’t want to, assemble one-by-one.

That’s where the uniquely Australian tailwind kicks in. Superannuation—“super”—is the country’s mandatory retirement savings system. Employers are required to contribute a portion of wages into investment funds that are preserved for retirement. Over time, that policy decision created a compounding pool of professional capital managers with a constant problem to solve: where to put ever-increasing inflows.

By now, Australia’s superannuation pool has grown to around AUD 4.2 trillion—an enormous figure relative to the size of the economy. A large share sits in APRA-regulated funds, bringing both scale and institutional discipline to how that money is deployed.

For Charter Hall, this mattered because commercial real estate fits what retirement capital tends to want: long leases, predictable income, and rent structures that can move with inflation. The founders recognised early that if they could become trusted stewards of that capital—reliably sourcing assets, structuring deals, and managing properties—they could ride a structural wave for decades.

A major milestone arrived in 2004, when Transfield Holdings acquired a 50% stake in Charter Hall. Transfield was a well-regarded Australian infrastructure and construction group, and the partnership gave Charter Hall a new level of institutional credibility—exactly the kind of endorsement that helps a young manager win bigger mandates.

That same year, David Harrison joined the business. At the time, Charter Hall was still a relatively small but profitable syndication shop, focused on development and opportunistic funds for Australian super funds. But with Transfield on the cap table and Harrison in the building, the ingredients were coming together for the shift from boutique operator to something much larger.

III. The IPO and Building the Platform: Going Public and Surviving the Storm (2005-2009)

In June 2005, Charter Hall went public on the Australian Securities Exchange. The speed was the tell. In a matter of months, the team had pulled together a property portfolio, stapled it to the funds management business, and taken the whole thing to market. For a young platform, it was a high-wire act: assemble real assets, package them with a fee-generating manager, and convince public investors it all belonged together.

The logic was straightforward. A listed vehicle would give Charter Hall something private managers never have enough of: permanent capital and public-market currency. It would make raising money easier, pursuing acquisitions more realistic, and—crucially—put Charter Hall on the radar of bigger institutional investors who like governance, transparency, and scale.

But going public also marked the beginning of a handover. André Biet left in 2005 when the company listed. David Southon would remain involved for another decade before leaving in 2016, and Cedric Fuchs retired in 2018. Founder exits like this aren’t unusual: entrepreneurs get the company to a natural inflection point, then step back as the job shifts from invention to execution.

That execution increasingly had David Harrison’s fingerprints on it. He would go on to oversee Charter Hall’s expansion from a relatively small manager at listing to the country’s largest diversified property funds manager.

The years right after the IPO were about building the machinery—systems, processes, and investor relationships that could support compounding growth. And then came the moment that separated the platforms built for fair weather from the ones built to survive: the Global Financial Crisis.

The GFC didn’t just bruise property markets. It exposed business models. Across Australia, plenty of real estate players had leaned on leverage and short-duration funding. When credit tightened, that combination turned fatal. Charter Hall, by contrast, came through in far better shape—and it wasn’t luck.

A core principle was to keep the parent company itself effectively ungeared, with negligible debt at the head stock company. If there was going to be gearing, Charter Hall preferred it to sit inside the individual funds it managed and co-invested in, where the risk could be sized and structured to match each vehicle.

It sounds conservative. It was. But it was also strategic. Keeping debt away from the corporate balance sheet meant the manager could stay standing even if a particular fund hit trouble. Investors could choose the leverage profile they wanted, while the fee engine—the part of the business that made Charter Hall durable—remained insulated from a liquidity spiral.

That discipline—low corporate leverage, long leases, and quality tenants—did more than get Charter Hall through the GFC. It set the template for how the platform would invest, partner, and grow in the years that followed.

IV. The Macquarie Acquisition: Turning Crisis Into Empire (2010)

If there’s one inflection point that reshaped Charter Hall’s trajectory, it’s what happened in 2010: the acquisition of Macquarie Group’s Australian real estate management platform. This wasn’t a bolt-on. It was a step-change that pushed Charter Hall from a credible, growing manager into the front rank of the industry.

Macquarie Group Limited agreed to sell the majority of its Australian real estate management platform to Charter Hall Group. Charter Hall would acquire the management business tied to two listed and three unlisted real estate funds, plus a portion of Macquarie’s holdings in three of those funds. And Macquarie didn’t just walk away: as part of the consideration, it agreed to a placement of CHC securities that would leave Macquarie holding 10% of Charter Hall’s securities on issue after the transaction.

Once completed, the deal took Charter Hall to more than A$10 billion in funds under management and made it one of the largest specialist real estate fund managers in Australia.

The context matters. Macquarie’s reputation in property and infrastructure investing was formidable, and its decision to exit most of its Australian real estate platform wasn’t a vote of no confidence in the assets. It was a strategic reset in the post-GFC world, with Macquarie repositioning capital and attention toward global infrastructure opportunities.

For Charter Hall, the timing was perfect. It had come through the GFC with its balance sheet intact, it had the institutional credibility to be taken seriously as a buyer, and it had the operational discipline to integrate something much larger than itself. And the prize wasn’t just the mandates and the fee base. It was people.

Adrian Taylor joined Charter Hall with the acquisition of the Macquarie Real Estate Platform in 2010. He went on to lead and support the growth of the Office investment management, asset management, development, and property management teams. Following Charter Hall’s 2016 organisational restructure and the creation of Sector Heads, that effort helped drive Office funds under management to $19 billion.

Just as important, the integration worked. Charter Hall absorbed the platform, kept key talent, and maintained performance—quiet proof that this wasn’t a one-off lucky deal, but the start of an integration playbook it could run again.

Macquarie’s Managing Director and CEO, Nicholas Moore, framed the decision like this: “Consistent with our strategy regarding the listed specialist funds business, Macquarie has undertaken a process to explore alternatives in relation to the future of Macquarie’s Australian real estate platform and maximise value for investors. As a result of this process, Macquarie has identified Charter Hall as a partner with a specialised real estate capability which Macquarie believes will be attractive for Fund stakeholders.”

In other words: Macquarie had looked around, and it chose Charter Hall. For institutional investors watching from the sidelines, that endorsement carried real weight. If Macquarie trusted Charter Hall with these assets and stakeholders, it made it a lot easier for the next wave of capital to do the same.

V. The Long WALE Strategy: Building Competitive Advantage (2010-2018)

With Macquarie’s platform absorbed and running, Charter Hall did something that great platforms eventually have to do: it put a name to what it was already becoming. That name was “Long WALE.”

WALE stands for Weighted Average Lease Expiry. In plain English, it’s the portfolio’s average lease length, weighted by how much rent each lease contributes. The longer the WALE, the more the income looks like an annuity instead of a rollercoaster. And for superannuation funds—investors with decades-long obligations—that kind of predictability is exactly the point.

Charter Hall leaned hard into owning and managing long WALE assets, predominantly leased to corporate and government tenants on long-term leases. The formula was consistent: quality assets, good locations, long leases, and a clear emphasis on resilience.

Just as important as the strategy was how they sourced the assets. A key competitive advantage was Charter Hall’s access to off-market deals, completing approximately 50% of all transactions in the last five years off-market. They also used their relationships to become a go-to partner for sale and leaseback transactions, completing more than A$11 billion of them over the past decade and cementing their leadership in the long WALE triple net lease sector.

Sale and leaseback is one of those structures that sounds boring until you realize why it’s so powerful. A corporate or government agency sells a building to Charter Hall (or one of its funds) and signs a long lease to stay put. The seller frees up capital without disrupting operations. Charter Hall gets a committed tenant for years. And the real payoff shows up for investors: steady, contract-backed income that doesn’t depend on constantly re-leasing space.

This strategy eventually got its own flagship vehicle. Charter Hall Long WALE REIT is an Australian Real Estate Investment Trust investing in high quality real estate assets that are predominantly leased to corporate and government tenants on long term leases.

In November 2016, Charter Hall Long WALE REIT listed on the Australian Securities Exchange, which at the time was the largest ever initial public offering for a diversified property trust in the Australian market.

The listing was a product strategy win: Charter Hall packaged a very specific promise—long leases, high-quality tenants, predictable cashflows—into a listed format that investors could buy with a click. The size of the IPO was the market’s way of saying: yes, we want exactly that.

Government tenants, in particular, became a bigger and bigger part of the story. Government covenants are about as strong as it gets in Australian property: extremely low default risk, and leases that often run long. Over time, federal and state government departments became some of Charter Hall’s most valuable tenant relationships.

Not everyone loved the idea at first. Some competitors saw long-lease property as “safe but slow,” and preferred higher-return opportunistic strategies. Charter Hall stuck with it anyway, betting that in a low-rate world the premium investors would pay for stability would only grow.

VI. The Acquisition Machine: Folkestone, Paradice and Beyond (2018-2022)

By the late 2010s, Charter Hall had its strategy, its scale, and a repeatable operating model. The next question was how to grow without drifting from what made the platform work. The answer was M&A—but with a very specific filter. Each acquisition needed to either widen the set of assets Charter Hall could credibly own for investors, or deepen the capabilities that kept its funds performing.

In August 2018, Charter Hall acquired rival Folkestone in a $205 million cash deal.

The immediate impact was scale: the deal added $1.6 billion to funds under management and contributed fund management and development investment earnings, making it earnings accretive for the group. But the more strategic prize was category expansion. Folkestone pulled Charter Hall further into social infrastructure and early learning—sectors that fit neatly with Long WALE logic.

Social infrastructure—childcare centres, healthcare facilities, government buildings—tends to have exactly what Charter Hall likes: essential services, regulated or government-linked tenants, and long leases. In other words, more income you can underwrite with confidence.

Charter Hall’s Managing Director and Group CEO, David Harrison, put it plainly: “We see the Folkestone business model as consistent with our existing strategy. We are attracted to their leading position in the social infrastructure sector and the suite of listed and unlisted funds adds to our diversity of sources of equity, whilst their origination capability is expected to generate property investments for the expanded list of managed funds. Importantly, the Folkestone culture shares many similarities to Charter Hall's own culture and we see the two organisations as a close fit.”

That last line about culture mattered. This wasn’t property development where you buy land and pour concrete. Funds management is a people-and-relationships business. When you buy a manager, you’re buying trust, distribution, and the teams who keep performance on track. If those people don’t stay and thrive, the deal doesn’t compound—it unravels.

Then Charter Hall did something that, for a property specialist, looked almost like a genre switch.

In 2021, the group announced a strategic partnership and a 50% investment in Paradice Investment Management (PIM), a listed equities manager with $18.2 billion in funds under management and a 20-year performance track record, operating from Sydney, Denver, and San Francisco. Charter Hall paid $207 million for its half, an investment it described as a strategic expansion of its broader funds management platform.

Harrison framed the rationale like this: “This partnership represents a rare opportunity to invest in a large scale, high-quality listed equities fund manager with $18.2 billion of FUM and a 20-year track record, building upon and significantly expanding our existing listed real estate equities business. It diversifies Charter Hall's FUM and earnings streams, introduces new client relationships to both businesses across wholesale and retail equity source segments.”

The move raised eyebrows for a reason. Why would a firm built on buildings step into equities? Because Charter Hall’s real asset wasn’t just its property portfolio—it was its client base. Many of its capital partners allocate across multiple asset classes. Offering listed equities alongside real estate wasn’t about abandoning the core; it was about becoming more useful to the same institutions, more often.

It was also a signal of what Charter Hall believed it had become: not merely a property manager, but a broader funds management platform—one that could keep widening its footprint without losing the discipline that got it there in the first place.

VII. The Business Model Deep Dive: How Charter Hall Actually Makes Money

If you want to understand why Charter Hall has been so durable across cycles, don’t start with the buildings. Start with the cashflows. Charter Hall earns money through three distinct but tightly linked channels—and together they turn a property business into a compounding fee machine.

Funds Management Fees: The biggest engine is simply getting paid to manage other people’s money. Charter Hall runs a lineup of listed and unlisted vehicles and charges investment management fees and property services fees across them. In most cases, those fees are tied to funds under management. So as FUM grows, the revenue line tends to rise with it. More importantly, these fees are recurring. Once an investor commits capital to a fund, Charter Hall keeps earning as long as that capital stays in the vehicle.

Co-Investment Returns: Charter Hall also invests its own capital alongside its investors, so part of its earnings come directly from rent and fund distributions. This does two things at once. First, it aligns incentives: Charter Hall’s capital goes up and down with the same performance its investors experience. Second, it adds an additional layer of return on the company’s balance sheet. The company’s balance sheet capital is primarily invested alongside its investors, and it has more than A$2.7 billion co-invested in its funds and partnerships.

Development Returns: The third channel is development. Charter Hall earns revenue from projects it manages, but this stream is smaller than the fee base. Think of development less as the core product and more as a lever: it can generate fees during construction and create newer, better assets that can ultimately be held inside Charter Hall-managed funds.

Put together, the model is designed for stability with some upside. Fees tend to be predictable because FUM usually doesn’t swing overnight and fee arrangements are set by contract. Co-investment returns move with markets, but they’re tied to the same long-lease, high-quality assets that define Charter Hall’s strategy. And development adds optionality without turning the whole company into a high-risk developer.

At scale, this structure becomes powerful. Charter Hall specialises in managing and investing in property on behalf of institutional and retail investors. It oversees investment funds encompassing over 1,500 properties and about $83 billion in value, plus a development pipeline projected to create around $13.3 billion in new assets. Investors can get exposure in different ways: they can buy shares in Charter Hall itself, or invest in one of its listed REITs.

That menu matters. Some investors want direct exposure to specific property portfolios through the REITs. Others want exposure to the manager—the platform that earns fees, makes acquisitions, and grows FUM—which can be more volatile, but can also compound faster when things go right. Charter Hall is built to offer both.

VIII. Leadership and Culture: The David Harrison Era

To understand how Charter Hall became what it is, you have to understand David Harrison—the executive who’s been at the centre of the platform for more than two decades.

Harrison didn’t arrive as a spreadsheet-first corporate climber. He came up through the physical reality of property: turning up to open homes, walking sites, and doing deals early enough that “after school” sometimes meant “at the sales office.” As a teenager, he even flipped a burnt-out house with his dad. For him, real estate wasn’t a career choice so much as the family trade.

He grew up in what he calls a “real estate family.” His parents were developers and auctioneers in Nabiac on the North Coast of New South Wales, and it wasn’t unusual for Harrison to be learning how to call an auction or working the sales sites. “Dad gave me the chance to do some small property deals when I was a teen,” he’s said. “I got a taste for real estate early.” He later formalised that grounding with a degree in Land Economics from the former Hawkesbury University, now part of the University of Western Sydney.

That background shows up in Charter Hall’s culture. Harrison tends to talk like an operator because he is one. He understands what makes a building work, why tenant relationships matter, and how painfully slow property cycles can be. It’s a style that pushes the firm toward durable, repeatable execution rather than clever financial engineering.

The leadership story at Charter Hall is also unusually clean for a founder-led business. André Biet left in 2005 when the company listed, David Southon departed in 2016, and Cedric Fuchs retired in 2018. Each transition happened without drama—orderly handovers, clear accountability, and a company that kept compounding through the changeovers.

That didn’t happen by accident. Charter Hall Chair David Clarke said the board and the Joint Managing Directors had spent nine months working toward a move to a single CEO/Managing Director structure as part of succession planning and the deliberate building of a stronger leadership team. With the group’s scale increasing, the view was that the business was ready for a simpler, clearer leadership model.

Inside the company, Harrison has been equally focused on what he calls “bench strength”—the idea that the platform should never be hostage to one person. That means developing leaders internally, but also being willing to hire proven executives from the outside when the moment calls for it.

One high-profile example was Carmel Hourigan, recruited from AMP Capital to lead the office business. Hourigan joined Charter Hall’s Executive Committee as Office CEO after resigning as AMP Capital’s Global Head of Real Estate, where she led a $29 billion property investment and management business.

It’s a consistent pattern: build a deep team, recruit experienced operators, and make the organisation strong enough that no single executive—Harrison included—becomes the whole story. For long-term investors, that’s not a soft cultural point. It’s a structural advantage.

IX. Recent Performance and Navigating Headwinds (2022-2025)

From 2022 to 2025, Charter Hall ran straight into the kind of environment that exposes every weakness in a real estate platform. Interest rates rose quickly, property values reset, institutional investors got cautious, and the office sector—once the backbone of commercial real estate—was forced into an uncomfortable public debate about demand in a post-pandemic world.

Management’s response was not dramatic. It was methodical.

Charter Hall’s Managing Director and Group CEO David Harrison said, “FY24 has seen us focus on the ongoing curation of the portfolios we manage, selective development, partnering with our tenant and investor customers to meet their needs and closely managing our cost base. This has seen us deliver a good result set against a tough real estate environment.”

The numbers reflected the reality of the market. Group funds under management fell by $6.5 billion to $80.9 billion, driven primarily by $6.1 billion in devaluations. With cap rates expanding as interest rates climbed, asset values came down—and because Charter Hall’s core revenue engine is management fees tied to FUM, that repricing flowed straight into earnings pressure.

What mattered was how the platform behaved under stress. Charter Hall kept its footing: disciplined portfolio management, selective deployment of capital, and a continued focus on balance-sheet conservatism. It wasn’t trying to “win the year.” It was trying to make sure the machine was still compounding when conditions improved.

By FY25, that improvement started to show. For the year ending 30 June 2025, Charter Hall reported operating earnings of $385.0 million. Operating earnings per security post-tax were 81.4 cents, up 7.3%.

Harrison described the shift as an inflection point: “In line with our comments at the start of FY25, we have seen an inflection year play out with stabilising asset values, falling interest rates and accelerating demand from all of our equity flow segments.”

And the capital flows backed that up. During FY25, Charter Hall completed the $1.3 billion privatisation of the ASX-listed HPI for a managed partnership between its listed REIT CQR and long-term wholesale investment partner Hostplus. It also completed one of the largest unlisted follow-on equity raisings in Australia, with its wholesale pooled fund CPIF securing $1.3 billion in gross equity inflows.

Investor momentum broadened too. Since the start of FY25, Charter Hall onboarded 14 new wholesale investor clients from Australia and multiple countries across Europe and Asia, while 41 existing wholesale investors increased their allocations over the same period.

By the end of FY25, group FUM had climbed $3.4 billion to $84.3 billion. That consisted of $66.8 billion in Property FUM, while listed equities FUM at Paradice Investment Management grew to $17.5 billion. Within Property FUM, the drivers told a story of active portfolio rotation: acquisitions of $2.9 billion and capex and development investment of $1.7 billion, partly offset by divestments of $3.2 billion, with net valuation movements broadly neutral.

Then there was the ESG milestone—one that’s easy to market, but hard to operationalise at platform scale. From 1 July 2025, Charter Hall said its whole platform would operate as Net Zero through existing onsite solar and renewable electricity contracts, as well as secured nature-based offsets.

In FY25, Charter Hall achieved a 77% reduction in absolute Scope 1 and Scope 2 emissions from its FY17 baseline. Across the platform, it had 86MW of solar installed, with 80% of the onsite solar across the group supplying tenants with clean energy.

For a property owner and manager, this isn’t just a “values” story. It’s a risk story. Assets that can’t meet sustainability expectations face a narrowing buyer pool, tougher regulation, and increasingly tenant resistance. By pushing early, Charter Hall positioned itself to keep its buildings investable—and leased—through the next decade.

Looking ahead, management’s guidance reflected confidence that the recovery had momentum. Assuming no material change in market conditions, Charter Hall guided to FY26 post-tax operating earnings per security of 90.0 cents, implying 10.6% growth over FY25.

X. Competitive Positioning: Porter's Five Forces Analysis

To see where Charter Hall really sits in the industry, zoom out from the individual deals and look at the forces that shape the whole game: who can enter, who has leverage, and where profits get competed away.

Threat of New Entrants: LOW

Starting a property funds management business is easy. Building one with real scale is brutally hard.

To compete with Charter Hall, a new manager needs far more than a good first fund. It needs billions in assets under management so the economics work, and it needs a reputation that convinces cautious institutional investors to write large cheques and stick around through cycles. Those relationships are built over years, sometimes decades, and they compound. Charter Hall has spent that time proving it can curate resilient portfolios and deliver through different market conditions—exactly the track record super funds and other institutions pay for.

Then there’s regulation. Australia’s financial services licensing and compliance burden isn’t impossible, but it’s heavy. And once you add listed REITs, the bar rises again: reporting, governance, disclosure. New entrants can clear these hurdles—but clearing them at scale, while also competing for deals and talent, is what keeps the threat low.

Bargaining Power of Suppliers (Property Vendors): MODERATE

In this context, “suppliers” are the people selling the assets: developers, corporations doing sale-and-leasebacks, other funds recycling capital.

Vendors do have power, especially when assets are scarce and auctions run hot. Charter Hall’s answer has been to avoid playing every game on the public field. About half of its transactions over the last five years have been off-market, where pricing tends to be less about who gets into a bidding war and more about who has the relationship and the certainty of execution.

The other release valve is development. When existing assets are expensive or hard to source, Charter Hall can build. That doesn’t eliminate vendor power, but it reduces dependence on it—because supply isn’t only something Charter Hall has to buy. It can also create it.

Bargaining Power of Buyers (Investors): MODERATE to HIGH

On the other side of the table are the buyers of Charter Hall’s product: institutional investors like superannuation funds and sovereign wealth funds. They’re sophisticated, they know what fees should look like, and they can always take a meeting with a competitor. Fee pressure is permanent.

But negotiating power isn’t the same as easy switching. Once an institution has done the due diligence, committed capital, and embedded a manager into its portfolio, changing course is costly—legally, operationally, and in relationship terms. Charter Hall’s scale and track record increase those switching costs.

There’s also stickiness on the tenant side that reinforces the platform. More than 71% of Charter Hall’s tenant customers lease multiple tenancies from the group. That kind of multi-asset relationship doesn’t just help leasing outcomes; it strengthens the overall ecosystem that institutional investors are buying into.

Threat of Substitutes: MODERATE

If an investor wants “property exposure,” Charter Hall isn’t the only option. They can buy listed REITs, use property ETFs, own buildings directly, or allocate to residential real estate. Each substitute comes with its own trade-offs—liquidity versus control, volatility versus stability, simplicity versus access.

Charter Hall’s structure helps it here. Investors can buy the manager itself, invest through one of its listed REITs, or go into unlisted funds. So instead of losing capital when investor preferences shift between listed and unlisted formats, Charter Hall can often capture the allocation either way.

And unlisted property funds still offer something hard to replicate elsewhere: less day-to-day volatility and more targeted exposure to specific strategies—features that tend to matter a lot to long-term, liability-driven pools of capital.

Competitive Rivalry: HIGH

This is a crowded, highly competitive market. Charter Hall regularly competes with well-capitalised peers: Goodman in logistics, Dexus in office, and diversified players like Mirvac, Stockland, and Lendlease. Each has deep relationships and real capabilities, and in the best assets, competition is intense.

Even so, Charter Hall isn’t trying to win every category with the same playbook. Its differentiation has been the combination: Long WALE discipline, multi-sector diversification, and a platform that can originate, manage, and scale across office, industrial, retail, and social infrastructure. In a market where plenty of firms are strong in one lane, Charter Hall’s advantage has been building a machine that can run across several—without losing the stability that institutions came for in the first place.

XI. Sources of Durable Competitive Advantage: Hamilton's Seven Powers

Porter tells you how tough the arena is. Hamilton Helmer’s Seven Powers tells you whether a company has something that lets it keep winning anyway. For Charter Hall, the answer is: yes—but in a very specific, very “real assets” way.

Scale Economies: STRONG

Charter Hall’s scale is the most obvious power, and it shows up everywhere. With roughly $84 billion in funds under management, the fixed costs of being a top-tier manager—compliance, systems, reporting, research, investment committees—get spread across a very large base. That creates a structural advantage over smaller rivals who have to run much of the same machinery on a fraction of the revenue.

Scale also buys access. When very large assets or platforms come to market, only a short list of groups have the capital base, balance sheet credibility, and operating depth to be taken seriously. Charter Hall’s size keeps it on that list—and makes the kind of step-change deal it did with Macquarie possible.

Network Effects: MODERATE

This isn’t a software business, but there is still a flywheel. The bigger Charter Hall gets, the more tenants it serves across sectors and cities—and that creates better market intelligence: what’s leasing, what’s not, where demand is moving, what tenants are willing to pay, and what they’ll sign for in lease terms.

That information advantage helps them originate and execute better deals, which attracts more tenants. The fact that more than 71% of tenant customers lease multiple tenancies from Charter Hall is a key proof point: these aren’t one-off transactions; they’re ongoing relationships.

The investor side compounds in a similar way. Institutions that have a good experience in one vehicle often allocate again—into another fund, another partnership, another mandate—building a base of repeat customers that funds the next leg of growth.

Counter-Positioning: STRONG (Historically)

Long WALE was counter-positioning in its purest form. Charter Hall leaned into long-lease assets—often with government or blue-chip tenants—at a time when many competitors dismissed that part of the market as too conservative and too low-return.

Because rivals were organised around more opportunistic strategies, they couldn’t easily pivot without admitting their old playbook was wrong and reallocating people and capital to a different style of investing. That hesitation created a window for Charter Hall to build expertise, relationships, and credibility in the segment. By the time others moved in, Charter Hall was already the obvious partner for a lot of the best sale-and-leaseback opportunities.

Switching Costs: MODERATE to HIGH

For large institutions, switching managers is painful. Due diligence can take months. Mandates have to be renegotiated. Structures and tax considerations can be complex. And once capital is committed into long-dated property vehicles, “leaving” often means either waiting for liquidity or selling positions in ways that can be costly.

Charter Hall’s style reinforces that stickiness. The focus on income resilience, long leases, consistent rent reviews, and active portfolio curation creates structures that investors tend to hold for the long term. The more embedded Charter Hall becomes inside an investor’s portfolio—across multiple funds and partnerships—the higher the real-world switching cost becomes.

Branding: MODERATE

In institutional funds management, brand isn’t built through advertising. It’s built through track record, governance, team quality, and how a manager behaves when markets turn.

On that dimension, Charter Hall’s reputation matters. Decades of curating resilient portfolios through multiple cycles has created trust—and trust is the closest thing this industry has to a consumer-style brand advantage. When investors are deciding who gets the next allocation, “we’ve seen them perform under pressure” carries weight.

Cornered Resource: MODERATE

Some advantages can’t be bought quickly, no matter how much money you have. Charter Hall’s web of relationships—with major tenants, institutional investors, and government stakeholders—has been built deal by deal over decades. Its transaction volume and dedicated teams across Australia’s major markets also create a depth of local insight that’s hard to replicate from the outside.

David Harrison’s long-standing relationships with large institutions fit here too. In a relationship-driven industry, access to capital is not just about returns; it’s also about trust built over time.

Process Power: STRONG

Charter Hall’s real long-run strength may be its operating system. Over thirty years, it has refined how it acquires assets, manages tenants, executes development, and runs funds. Those processes aren’t flashy, but they are repeatable—and repetition is where advantages get embedded.

You can see it most clearly in integration. The Macquarie platform in 2010, Folkestone in 2018, and the later HPI transaction all required Charter Hall to absorb complexity without losing momentum. That “integration playbook” is organizational knowledge: it lives in people, routines, and decision-making patterns, and it gets better each time they run it.

XII. Bull Case and Bear Case: The Investment Debate

The Bull Case

Over the past year, Charter Hall’s share price rose 36.35%, outperforming the ASX All Ordinaries Index by 26.54%. That kind of gap usually signals that the market believes two things at once: the worst of the valuation reset is likely behind the sector, and Charter Hall is one of the managers best positioned to benefit from the next leg.

A few forces underpin the optimistic view:

Industrial & Logistics Tailwinds: Demand for logistics space has kept climbing, helped by e-commerce, population growth, and limited supply in the right locations. In markets where vacancy is close to zero, landlords gain pricing power. For a platform with scale in the sector, that can translate into stronger occupancy, rental growth, and improving asset values over time.

Interest Rate Tailwinds: After sharp rate hikes through 2022 to 2024, central banks began easing. Property is highly sensitive to the cost of capital, so falling rates typically support valuations and make steady, income-producing real estate look more compelling relative to cash and bonds.

ESG Leadership: From 1 July 2025, Charter Hall said its whole platform operates as Net Zero through existing onsite solar and renewable electricity contracts. As more institutional mandates bake sustainability requirements into portfolio construction, this becomes less of a branding point and more of an access advantage.

Portfolio Quality: The underlying portfolio has remained resilient, with occupancy at 97.4%. The weighted average lease expiry is 7.2 years, and the portfolio benefits from a 3.4% weighted average rent review—structures that support more predictable income.

Development Pipeline: Organic growth remains a meaningful lever. Charter Hall’s pipeline continues to be replenished, and the $1.8 billion Chifley South development—its largest single project—signals an ability to deliver trophy-scale assets, not just buy them.

The Bear Case

The skeptical view starts with a simple concern: even great managers can’t fully escape sector-wide gravity. If office and retail remain structurally challenged, or if capital markets turn against real estate again, Charter Hall’s earnings and growth could come under pressure.

Key risks include:

Office Exposure: The office sector sits under a cloud globally as hybrid work resets demand. Charter Hall’s office assets skew toward premium quality, but the bigger question is secular: how much space do tenants really need going forward, and what does that mean for occupancy and rent?

Interest Rate Sensitivity: Even with cuts, rates are still higher than the post-GFC era. If inflation proves stubborn and rates stay “higher for longer,” cap rates could remain pressured, keeping property valuations lower and dampening transaction activity.

Fee Compression: Funds management is a competitive business. Investors constantly push for lower fees, and passive strategies increase pressure across the industry. Over time, that can squeeze margins unless a manager can clearly differentiate on performance, access, or service.

Concentration Risk: Government tenants are a major source of portfolio income. The credit quality is strong, but concentration can still create risk if policies shift, budgets tighten, or leasing decisions change over time.

Global Capital Competition: International capital continues to target Australian real estate. More bidders can mean higher entry prices, which can compress returns and make it harder to find acquisitions that meet the bar.

XIII. Key Metrics for Investors to Track

If you’re trying to keep score on Charter Hall from here, it’s tempting to get lost in property valuations and short-term sentiment. But the business itself tends to telegraph its health through a handful of indicators. Three, in particular, are worth watching:

1. Funds Under Management (FUM) Growth: FUM is the base that the fee engine runs on. It’s not just the headline number that matters, but what’s driving it—new investor inflows, acquisitions, or asset revaluations. The cleanest kind of growth is capital that chooses to come in. Growth that’s mostly valuation uplift can disappear as quickly as it arrived.

2. Weighted Average Lease Expiry (WALE): Charter Hall’s Long WALE positioning lives or dies on lease length. If portfolio WALE starts to drift down in a meaningful way, that can be an early warning sign that the platform is accepting shorter leases to protect occupancy, or that competitive dynamics are forcing a change in the strategy.

3. Operating Earnings Per Security (OEPS) Growth: OEPS is the metric that aims to show the underlying earning power of the manager, stripping out valuation swings and one-off items. It’s also the number management guides to—so consistently hitting it matters for credibility. For FY26, Charter Hall guided to post-tax operating earnings per security of 90.0 cents, implying 10.6% growth over FY25.

XIV. Lessons from Charter Hall: A Playbook for Durable Business Building

The Charter Hall story leaves you with a handful of lessons that travel well beyond Australian real estate.

1. Alignment Creates Trust: Charter Hall’s co-investment model—committing meaningful capital alongside its investors—turns a nice slogan into something enforceable. When the manager wins and loses in the same portfolio, decision-making tends to stay anchored on long-term outcomes, not just short-term fee maximisation.

2. Opportunistic M&A Can Transform: The 2010 Macquarie acquisition worked because Charter Hall was ready for it. The big step-changes usually don’t arrive with much warning, and they rarely come when conditions feel comfortable. Having the financial flexibility and operational confidence to act during dislocations—when others are retrenching—can create the kind of leap in scale that compounds for years.

3. Patience with Strategy Pays: Long WALE wasn’t an overnight hit. Charter Hall backed long leases, government and blue-chip tenants, and predictable income when parts of the market were chasing faster stories. Sticking with the strategy long enough to build relationships and a track record turned “boring” into differentiation—then into a flywheel.

4. People Matter in Asset Management: The recurring theme across Macquarie, Folkestone, and HPI wasn’t just assets and mandates—it was talent retention and integration. In funds management, the real product is judgement and execution, and that walks out the door every evening. Deals only compound when the people who make the platform work actually stay.

5. Scale Begets Scale: Once Charter Hall reached critical mass, growth got easier. Large institutions prefer managers who can take meaningful allocations, execute large transactions with certainty, and run multiple strategies under one roof. That preference creates a reinforcing loop: scale attracts capital, capital enables more scale.

From a small office in North Sydney in 1991 to Australia’s largest diversified property funds manager, Charter Hall’s rise wasn’t built on a single bet. It was built on repeatable discipline: survive downturns, invest alongside clients, keep the balance sheet resilient, and take the big swing when the right one appears.

Whether the next thirty years are as rewarding as the first is unknowable. Property cycles will keep turning. Work patterns will keep shifting. Regulation and climate realities will keep reshaping what “quality assets” even means. But the core of Charter Hall’s advantage—strategic clarity, operating execution, and incentives that line up—has historically been exactly what you want when the environment gets harder, not easier.

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music