CAR Group: From Melbourne Garage to Global Marketplace Empire

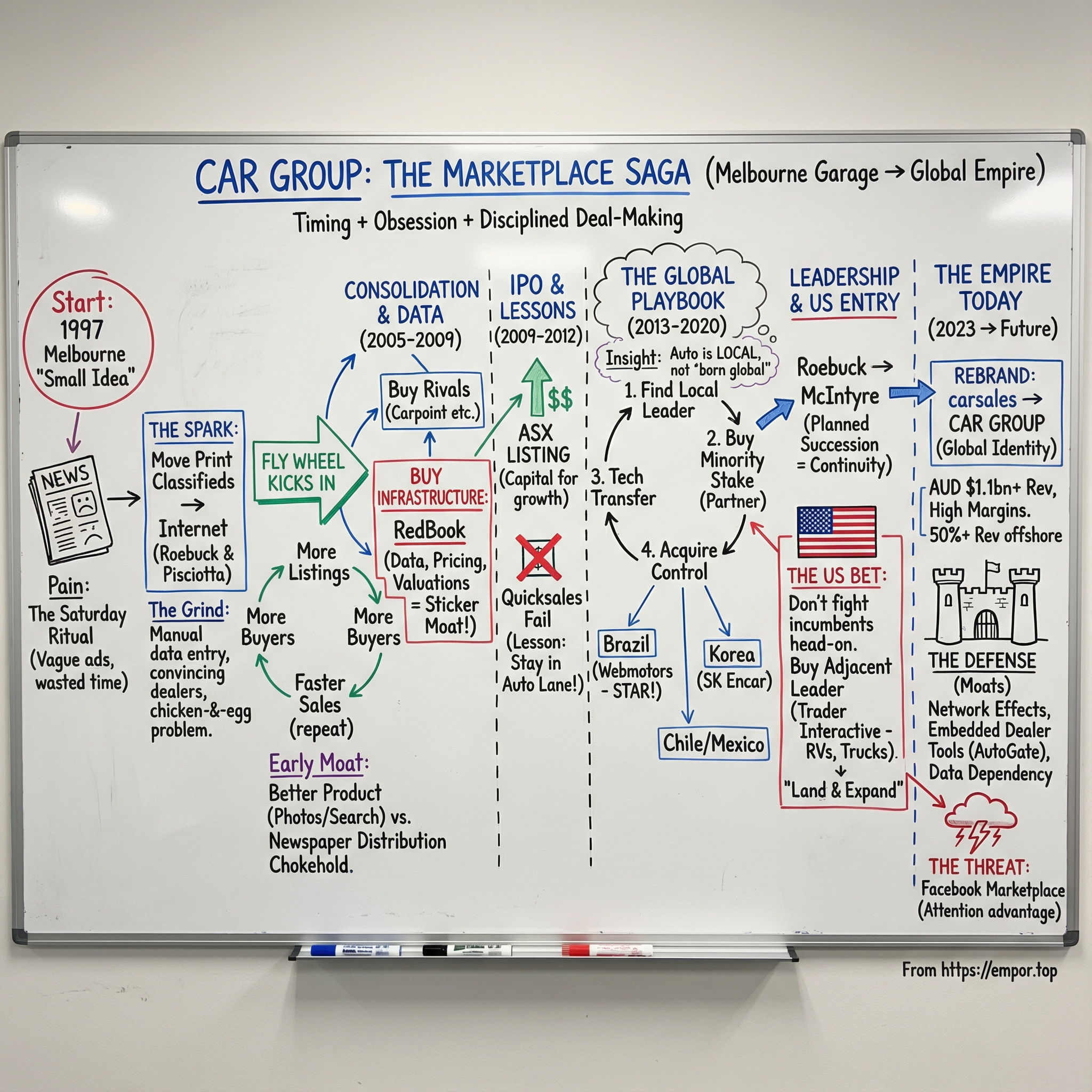

I. Introduction & Episode Roadmap

In the autumn of 1997, somewhere in Melbourne’s inner suburbs, Greg Roebuck was stuck in a ritual every Australian car buyer knew too well. Saturday’s newspapers were spread across the kitchen table, classifieds circled and re-circled. He’d call dealers, get vague answers, then burn half a day driving across town to inspect a car that—surprise—didn’t quite match the ad. It was expensive in time, annoying in effort, and somehow always felt like you were the one doing the work in a market built to take your money.

Most people would grit their teeth, buy the car, and move on. Roebuck didn’t. He’d spent years in automotive technology—first as a software developer, then rising to a senior executive role at Pentana Solutions, which built dealer management systems. He understood how dealers worked, how listings were managed, how information flowed, and more importantly, how badly the whole process served ordinary buyers. As one summary of his story puts it: he recognised a need—and decided to build the better version.

That frustration at the kitchen table became the spark for what would eventually turn into CAR Group: a global vehicle marketplace business that started with a simple premise—move motor vehicle classifieds from print to the internet—back when “the internet” still sounded like a fad you had to explain.

Today, CAR Group Limited is an ASX-listed digital marketplace company operating across Oceania, Asia, and the Americas. In the 12 months to June 2025, it recorded double-digit growth across most of the business, with revenue up 12% year-on-year to AUD1.1 billion and EBITDA also up 12% to AUD641 million.

But those numbers are just the scoreboard. The real story is what sits underneath: a company that began as an Australian classifieds site and now owns and operates marketplaces in Australia, South Korea, the United States, and Chile—plus a majority stake in Webmotors in Brazil. In that same period, Latin America was the standout region, with revenue growth driven by what the company called “outstanding growth” at Webmotors. More than half of CAR Group’s revenue now comes from outside Australia—an astonishing outcome for a business that once lived and died by the Saturday paper.

So here’s the question that frames this episode: how did two Australians—at a time when you practically had to spell “internet” for people—build a marketplace engine that went from dial-up obscurity to a portfolio spanning five continents?

The answer isn’t magic. It’s network effects that harden into near-unstoppable positions once they tip. It’s a patient acquisition playbook, refined over decades, that consistently targeted leadership positions in local markets. And it’s a contrarian insight that marketplaces like this don’t naturally go global the way Silicon Valley loves to imagine—they’re often geographically bound, which means expansion is less about cloning the product everywhere and more about buying your way into the next country’s winner.

We’ll follow the arc from founding through IPO, break down the inflection points that turned a local champion into a global consolidator, and then ask the uncomfortable, modern question: can the moat that protected CAR Group for nearly three decades hold up against Facebook Marketplace—and the next wave of digital disruptors still forming on the horizon?

II. Founding Context: Australia in the Dial-Up Era (1996-1999)

To understand why carsales was such a big bet, you have to rewind to Australia in the mid-1990s.

The country was shaking off recession, Paul Keating had just lost the prime ministership to John Howard, and the Sydney Olympics were still years away. The internet technically existed… but only just. If you were online at all, you were doing it through a dial-up modem, waiting for pages to load on Netscape Navigator, and hunting around Yahoo!, Excite, or Lycos. For most people, the idea of typing a web address into a browser wasn’t yet muscle memory—it was trivia.

And in that world, newspapers felt untouchable. Not just as news, but as the operating system for classifieds. The Saturday paper was where buying and selling happened. In 2002, Australian newspapers still captured 96% of all classified advertising—about $1.6 billion—powered by thick weekend sections in the major metro dailies and staples like The Trading Post. Dealers paid real money for display ads. Private sellers paid by the word and tried to make every character count.

That format created a very particular kind of pain.

Newspapers were limited by physical space, so listings were brutally compressed. “1996 Toyota Camry, white, auto, a/c, vgc, ono” wasn’t a description so much as a riddle. Photos were expensive and rare. And the information gap was massive: buyers did the running around, sellers controlled the details, and everyone wasted time.

Greg Roebuck saw that up close and, eventually, got sick of it. In 1997, after becoming disillusioned with how classifieds worked, he decided there had to be a better way to buy and sell cars. Alongside co-founder Wal Pisciotta, he helped establish carsales in Melbourne—what would eventually become CAR Group—built on what sounded like a simple idea at the time: take the motor vehicle classifieds from print and put them on the internet.

Roebuck wasn’t just annoyed; he was unusually equipped to act. He’d studied Computer Science at RMIT and spent years in software, including starting his own business before joining Pentana Solutions as a developer back in 1983. In the early 1990s, he built a network solution that linked hundreds of automotive dealerships so they could trade spare parts in real time.

That dealer network—and those relationships—became a quiet superpower. Roebuck understood how dealers actually managed inventory, what their systems could and couldn’t do, and what would make them consider a new channel. The leap from “dealers sharing parts in real time” to “dealers publishing inventory online” wasn’t obvious to the market, but it was obvious to him.

Still, the execution was anything but smooth.

This was an era when most Australians had never made an online transaction, and plenty of businesses still treated the internet like a curiosity. Getting dealers to list cars on a website took persistence bordering on evangelism. The founding team went dealership to dealership in person, taking photos themselves, collecting details, and manually entering vehicle data. Often, they had to explain the internet before they could explain why it mattered.

And like every marketplace, carsales ran headfirst into the classic chicken-and-egg problem: buyers won’t show up without listings, and sellers won’t list without buyers. Carsales worked around it the way the best early marketplaces do—by leaning on Roebuck’s existing dealer relationships and making it as easy as possible for early adopters to participate, essentially buying time to reach critical mass.

They were betting that if they could get enough inventory in one place—fast—network effects would take over.

What happened next proved that bet wasn’t just reasonable. It was inevitable.

III. Building the Australian Moat (1997-2005)

In its early years, the strategic genius of carsales was understanding that “online classifieds” weren’t just newspaper ads on a screen. They were a different product entirely—and one newspapers were structurally built to lose to.

For most of the 20th century, newspapers didn’t win because their content was impossible to copy. They won because distribution was impossible to compete with. Owning printing presses and delivery networks meant you controlled access to local readers. A rival paper couldn’t just pop up next door; the fixed costs were too high, and most cities couldn’t support two players at scale. The moat wasn’t the journalism. It was the chokehold on distribution.

Then the internet showed up and made distribution effectively free. Suddenly, anyone could reach anyone. The old advantage collapsed—and the new game became aggregation. If supply was now infinite, the winners would be the platforms that gathered demand in one place.

Carsales grasped that instinctively. The internet didn’t just make classifieds cheaper. It made them bigger, deeper, and more useful. A newspaper might run a few hundred car listings on a Saturday, cramped into tiny text boxes. Carsales could hold tens of thousands, each with photos, specs, and contact details. The improvement wasn’t incremental. It was categorical.

And once that inventory started to build, the flywheel kicked in.

More listings brought more buyers. More buyers meant cars sold faster. Faster sales brought more sellers. The loop fed itself, and with every turn, it got harder for anyone else to break in. That’s the marketplace dynamic in its purest form: the platform gets better because people use it, and people use it because it’s better.

But carsales didn’t sit back and wait for network effects to do all the work. It made an early choice that shaped everything that followed: keep spending heavily on sales and marketing even as the flywheel gathered speed. The company devoted a meaningful share of revenue to those efforts—high by marketplace standards, even compared to modern consumer giants.

At first glance, that can look unnecessary. If network effects are doing their job, shouldn’t customer acquisition get cheaper over time?

Not in cars. Car buying is infrequent and high-consideration. Most people aren’t shopping every week; they might buy once every several years. So carsales didn’t just need to be good. It needed to be remembered. When the moment came—when someone’s old car finally died, when a new baby arrived, when a job changed—it had to be the first place they thought to look. That takes relentless brand building.

Just as important, carsales sold outcomes, not ad space.

Newspaper classifieds charged by the word or by the day. Carsales reframed the entire relationship around what sellers actually cared about: selling the car. That meant investing in the things that reduced time-to-sale, improved lead quality, and gave both dealers and private sellers confidence they were reaching real buyers—not just paying for exposure and hoping for the best.

That outcome obsession became a defining habit. Win the audience, deliver results for sellers, and the economics follow.

By the early 2000s, the direction of travel was obvious: newspapers were losing the classifieds war, and they couldn’t outmaneuver it without destroying themselves. Classifieds had been their “rivers of gold,” the profit engine that subsidized everything else. As those rivers rerouted to online specialists, the old model cracked. You can see it in the modern internet’s everyday rituals: listing a bike on Gumtree, browsing homes on Domain, searching cars on carsales—each one is a slice of value that used to live in newsprint.

The shift didn’t happen overnight, but it became undeniable. Over time, the classifieds market kept growing, while the newspaper share kept shrinking, with the balance flowing to category-specific online leaders like carsales, Seek, and the property portals.

For long-term investors, this era is where the template gets locked in. Carsales built leadership through network effects and sustained marketing, then used that dominance to earn the kind of profits that could fund the next chapter. The moat wasn’t an accident.

It was being dug—deliberately.

IV. Inflection Point #1: The Consolidation Play (2005-2009)

By 2005, carsales had proved the internet could beat ink. It had real momentum in Australia, real dealer relationships, and a flywheel that was starting to feel inevitable.

But it was still a relatively small, privately held company in a market where the incumbents—big publishers with big balance sheets—didn’t like losing. This is the moment where a lot of early marketplace winners either get dragged into years of expensive trench warfare… or they change the battlefield.

Roebuck chose the second option.

In October 2005, carsales acquired ACP Magazines’ online classified businesses: Carpoint.com.au, Boatpoint.com.au, Bikepoint.com.au, Ihub.com.au, and the data-focused Equipment Research Group. In exchange, ACP’s parent company, Publishing & Broadcasting Limited, took a 41% stake in carsales.

This was the deal that turned carsales from “the fast-growing category site” into “the consolidator”—and it basically wrote the playbook the company would use for the next two decades.

Start with the obvious win: Carpoint was the most credible online rival, backed by serious media muscle. Rather than bleed cash trying to outspend each other for dealers and traffic, carsales took the clean route—buy the competitor, fold the inventory together, and let the network effects compound in one place.

Then there’s the less obvious win: the deal didn’t just remove a threat, it widened the playing field. Boatpoint and Bikepoint dropped carsales into adjacent categories where the mechanics were familiar—listings, leads, dealers, repeatable sales motion—but the revenue was incremental. Same marketplace logic, more surfaces to apply it.

And the sleeper asset in the bundle was Equipment Research Group. Carsales wasn’t just buying listings and brands; it was buying information. That matters, because in vehicle markets, data isn’t a nice-to-have. It’s the plumbing.

The structure of the deal mattered too. Carsales didn’t have to show up with a suitcase of cash it didn’t have. It used equity—bringing Publishing & Broadcasting Limited (later Nine Entertainment) onto the register as a major shareholder. For a capital-light business in the mid-2000s, that was a very pragmatic way to buy scale without overextending the balance sheet.

Two years later, carsales doubled down on the “own the infrastructure” idea. In August 2007, it bought RedBook.

RedBook was already a foundational name in vehicle identification and pricing information—operating in Australia since the 1940s and recognised as a leading supplier of independent new and used vehicle values in Australia. It provided pricing adjusted for things like condition, kilometres, and factory options, and its footprint extended beyond Australia into markets including New Zealand and parts of Asia and the Middle East.

If carsales was where cars got marketed, RedBook was how cars got priced.

That combination is powerful. Dealers relied on RedBook valuations to price inventory and assess trade-ins. Banks and insurers used it to underwrite loans and value vehicles. By owning RedBook, carsales didn’t just add another product line; it plugged itself deeper into the daily workflows of the entire automotive ecosystem—and picked up a stream of high-value, repeatable revenue along the way.

Over time, RedBook also became a switching-cost machine. When dealers build valuation tools into their process—inventory decisions, appraisals, negotiations—it’s not something you swap out on a whim. The dependency deepens, and the data advantage compounds. After more than 70 years in the business, RedBook positioned itself as a technology leader too, applying machine learning and AI across specification data, pricing analysis, valuations, and forecasting.

Zoom out, and the pattern is clear. Roebuck wasn’t just trying to make carsales a better website. He was reshaping the industry structure around it—consolidating rivals, expanding into adjacencies, and locking in data assets that made the platform harder to replace.

That “buy the leader, integrate the data, expand outward” playbook worked in Australia. And soon, carsales would start testing it on the rest of the world.

For investors, the takeaway is straightforward: the real durability in marketplaces often comes from everything built around the transaction—data, workflow tools, and relationships that make leaving feel like ripping out a core system, not just changing where you post an ad.

V. Inflection Point #2: The IPO and Post-Listing Growth (2009-2012)

By 2009, carsales had done the hard part: it had built a real moat in Australia. But the next phase of the strategy—consolidating, buying data assets, and expanding into new verticals—had a very unglamorous requirement: capital. Organic growth was strong, but it wasn’t going to bankroll the ambitions Roebuck was building toward.

So carsales went public.

On 10 September 2009, carsales.com Ltd listed on the Australian Securities Exchange. It raised $248.7 million in the nation’s biggest IPO that year and debuted with a market value of about $812 million at the offer price of $1.70 per share.

And the timing made it even more remarkable. This was 2009—right after the Global Financial Crisis had ripped through markets. Lehman had collapsed the year before, risk appetite was thin, and IPOs were hardly in vogue. That carsales could still pull off the largest Australian float of the year said something important: investors weren’t just buying a website. They were buying a marketplace with real network effects and a category leadership position that already looked hard to dislodge.

For Roebuck personally, it was also a public validation. In the same year, he won the 2009 Ernst & Young Entrepreneur of the Year award, and also took out the Technology & Emerging Industries title. It capped a banner stretch for the business: the IPO, the launch of homesales.com.au, and a mobile version of carsales.com.au—an early signal that the company intended to follow consumers as their behavior shifted.

Then came the reality of life as a public company: more capital, more scrutiny, and more pressure to keep finding growth.

One of the first swings with the new balance sheet was in 2010, when carsales acquired Quicksales, a general classifieds and auctions site. It’s easy to see the logic: if you’ve mastered a marketplace in vehicles, why not apply the playbook to everything else?

But this is where carsales learned a lesson the hard way. General classifieds aren’t just “cars, but broader.” The dynamics are different, the competitive set is different, and the edge carsales had built—deep dealer relationships, vehicle-specific data, and high-intent automotive buyers—didn’t transfer cleanly. After years of underperformance, Quicksales was shut down in 2018.

It was a rare misstep, but an important one. It taught carsales to stay in its lane: focus on categories where its specific advantages were real, and where it could win decisively. That discipline would matter a lot when the company started looking offshore.

Another key moment in this post-IPO chapter came in March 2011, when Nine Entertainment—previously Publishing & Broadcasting Limited—sold its 49% shareholding in carsales.

On paper, losing a major shareholder can look like instability. In practice, this one was freeing. Having a large media conglomerate on the register could create conflicts and limit strategic flexibility. Nine’s exit helped carsales’ ownership base settle into a more typical mix of institutional investors—stakeholders with fewer entanglements, longer time horizons, and clearer incentives to back the next phase of growth.

In hindsight, the IPO era did exactly what it needed to do. It provided the currency and credibility for bigger moves, while also clarifying the company’s strategy through a very public mistake.

And it set the stage for what came next: the most transformative phase of carsales’ evolution—when the playbook that worked in Australia started getting exported, market by market, across the globe.

VI. Inflection Point #3: The Global Expansion Strategy (2013-2020)

Up to this point, the carsales playbook had been elegantly simple: win Australia, deepen the moat with data and workflow tools, and let network effects do their compounding work.

The obvious next question was: why not just take that same site and roll it out country by country?

Because carsales came to a conclusion that cut against the grain of the 2010s tech narrative. While Silicon Valley was obsessed with “born global” platforms, carsales learned that vehicle marketplaces don’t tend to globalise. They localise. And in practice, that means one or two winners per country or region.

The interesting structural characteristic—just judging by how carsales evolved—was that digital vehicle sales seemed geographically bound. Unlike Airbnb, which scaled a marketplace for accommodation across borders, vehicle classifieds repeatedly produced local champions. And whatever the underlying reasons, the implication for strategy was clear: you had to think about the market through the lens of geography, mainly by country.

There are real-world reasons this category behaves that way. Cars are physical goods, and most transactions happen locally. Cross-border deals are rare, weighed down by logistics, regulation, and market quirks like right-hand versus left-hand drive. Dealer relationships are built street by street. Trust is built through local brands and local marketing. And everything from language to payments to consumer expectations varies country to country.

So international expansion wasn’t going to look like “launch carsales.com in Brazil.” It was going to look like: find the winner in Brazil, and partner with them—or buy them.

And that’s exactly what they did. In market after market, the company’s best results came from acquiring the leading car marketplace, then using that dominant position as a base to expand into other vehicle categories.

Starting in 2013, carsales began assembling an international portfolio with a rhythm that became almost clockwork: stakes—sometimes minority, sometimes majority—in category leaders across new geographies. Over the decade that followed, it took positions in iCar Asia, Webmotors in Brazil, SK Encar in South Korea, Soloautos in Mexico, chileautos in Chile, and later Trader Interactive in the United States.

The first moves came in quick succession. In March 2013, carsales bought a 20% stake in iCar Asia. The next month, it bought a 30% shareholding in Webmotors in Brazil from Banco Santander.

South Korea followed soon after, and it showed how seriously carsales took the “buy the leader” doctrine. In March 2014, it purchased 49% of SK Encar from SK C&C, positioning itself alongside what it expected to be the clear number one marketplace in the country based on inventory and traffic. The company framed the deal as a meaningful step in its long-term internationalisation—adding Korea to a growing set of interests that already spanned multiple Asian markets, Brazil, and New Zealand.

Then it did what it often preferred to do next: move from partner to owner. The remaining 51% of SK Encar was acquired in 2016.

This was the broader pattern. Carsales often started with a significant but non-controlling stake—typically something like 30–50%—worked closely with the local team, and then stepped up to control once the partnership proved out. It was a pragmatic way to reduce risk, learn market specifics, and avoid paying full price before it had real operating confidence.

South Korea is the cleanest example. Carsales bought an initial 49.9% stake in SK Encar for $126 million in 2014. Later, SK Holdings sold its remaining 50.1% stake for 205 billion won (approximately $187 million), taking carsales to full ownership of the platform. In total, that put carsales’ investment at roughly $313 million to own South Korea’s dominant used-car marketplace outright—and it went on to become one of the group’s strongest performers.

In 2016, the Latin American footprint widened further with the purchases of Soloautos in Mexico and chileautos in Chile. The logic stayed consistent: identify the leader, buy in, bring technology and operating know-how, and build from a position of strength.

For investors looking back on this era, what stands out isn’t one blockbuster deal. It’s the discipline. Carsales didn’t try to force organic expansion into unfamiliar markets, and it didn’t swing at mega-acquisitions that could have strained the balance sheet. It methodically assembled leadership positions—one geography at a time—and by 2020, those international operations had become a meaningful and growing part of the group.

VII. Leadership Transition: From Founder to Professional Management (2017)

In technology companies, the handoff from founder to professional CEO is one of the highest-risk moments there is. Done badly, it can wipe out years of momentum: founders hang on too long, successors arrive without credibility, and the culture fractures right when execution matters most.

Carsales is a case study in the opposite.

In March 2017, Greg Roebuck stepped down as CEO and handed the reins to Cameron McIntyre, who had been the company’s COO. But this wasn’t a sudden baton pass. It was the culmination of a succession plan that had been running in plain sight for a decade.

To see why it worked, you have to go back to 2007. Carsales was scaling quickly, the stakes were rising, and Roebuck needed a CFO who could bring structure without slowing the business down. On paper, McIntyre didn’t look like the classic “tech CFO” hire. His experience came from established, legacy-heavy organisations—manufacturing and publishing—rather than startups.

What carsales got, though, was exactly what it needed: financial discipline and operating maturity, bolted onto a business that already had product-market fit.

McIntyre joined carsales (as it was then known) in 2007 as CFO. Before that, he’d been Finance Director at Sensis, and earlier, Group Financial Controller APAC at Assa Abloy. Over time, he moved deeper into the engine room: becoming COO in 2014, then Managing Director and CEO in 2017. Along the way, he built the kind of internal trust that can’t be rushed—first with the numbers, then with operations, and finally with leadership.

His background was atypical for a tech CEO, but not lightweight. He held a Degree in Economics from La Trobe University, was a Certified Practicing Accountant, and was a graduate of Harvard Business School’s General Management Program.

The sequence mattered. McIntyre had ten years inside the business before taking the top job—time to understand the marketplace dynamics, learn the dealer ecosystem, work through acquisitions, and earn legitimacy with the team and the board. Founder transitions tend to fail when they’re treated like a single event. Carsales treated it like a long project.

And under McIntyre, the strategy didn’t change—it scaled.

The international playbook Roebuck had established stayed intact: buy into leading positions, contribute technology and expertise, then move toward control when the partnership worked. What McIntyre added was an extra layer of operational rigour and capital discipline—traits that become more important as a company shifts from “winning one country” to managing a portfolio across continents.

Over his tenure as CEO, the group became more than five times larger, climbed into the ASX top 50, and joined the MSCI index. It also became meaningfully global, with almost 60% of the business based offshore.

By the time McIntyre announced his departure in 2025, carsales had gone from being primarily an Australian classifieds leader with international options into a global automotive marketplace specialist—one that had executed major acquisitions in the world’s two largest vehicle markets, the United States and Brazil. And in a nice twist of symmetry, he wasn’t just the steward of the global phase; he’d also been one of the key architects of the company’s 2009 IPO.

VIII. Inflection Point #4: The US Market Entry via Trader Interactive (2021-2022)

Every globally ambitious Australian company eventually runs into the same, intimidating question: how do you crack America?

The United States is the world’s largest vehicle market. It’s also brutally competitive, saturated with well-funded incumbents, and littered with the cautionary tales of foreign companies that assumed “big market” automatically meant “easy growth.”

CAR Group did enter the U.S.—but it didn’t do it the way it had everywhere else.

In Brazil, Korea, and Chile, the pattern was consistent: find the leading vehicle marketplace, buy in, then deepen ownership over time. In America, that playbook ran into a wall. The car classifieds battlefield was already spoken for. AutoTrader, owned by Cox Automotive, was a powerhouse in new and used listings. Cars.com was public and scaled. CarGurus, founded by the TripAdvisor team, had already proven it could disrupt its way into relevance. Charging straight into that lane would have meant a long, expensive fight on incumbents’ home turf—a classic recipe for destroying shareholder value.

So carsales (as it was still known then) took an adjacent door instead.

In August 2021, it acquired 49% of Trader Interactive, a U.S. marketplace operator that doesn’t primarily sell cars. Then, on September 30, 2022, it completed the acquisition of the remaining 51% stake from Eurazeo SE.

Trader Interactive connects buyers and sellers across powersports, recreational vehicles, commercial vehicles, and heavy equipment. It reaches about 13 million unique monthly visitors and works with more than 9,500 dealers. Its portfolio sits under a family of “Trader” brands that had been around for decades, including Cycle Trader, RV Trader, ATV Trader, PWC Trader, Snowmobile Trader, Aero Trader, Trade-A-Plane, Commercial Truck Trader, Equipment Trader, NextTruck, Rock & Dirt, and Tradequip.

And this wasn’t just a “nice foothold” market. CAR pointed out that the U.S. non-automotive market it was stepping into was far larger than the equivalent category set in Australia, and even bigger than Australia’s automotive market.

Of course, entering the U.S. this way didn’t come cheap. Trader Interactive was valued on a 100% enterprise value basis at US$1.625 billion (around A$2.074 billion at the time), implying a CY20 EV to adjusted EBITDA multiple of 26.5x. The deal was staged: first 49%, then the remaining 51% the following year for US$809 million (A$1.17 billion), up from the US$624 million (A$797 million) paid for the first half.

Carsales framed it as a continuation of what it believed it did best: build partnerships, then scale them into something bigger.

"We have demonstrated the ability to build valuable international partnerships over many years in our automotive business and see this acquisition as an important milestone in Carsales' international growth and vertical marketplace expansion."

Underneath that message sat a multi-layered strategic rationale.

First: Trader Interactive was already a proven, profitable business. In CY20 it generated US$123 million in revenue and US$61 million in EBITDA, and it had delivered earnings growth, with EBITDA rising at a 13% compound annual rate over the prior five years.

Second: it offered a “land and expand” path into the U.S. Instead of trying to win cars immediately, carsales could build a serious operating base—brands, dealer relationships, and infrastructure—in adjacent vehicle categories. In theory, that could later become a platform for automotive expansion.

Third—and this was the real bet—it was a test of whether carsales’ core competency travelled. If the company could create value in RVs, commercial trucks, and equipment across a massive, fragmented U.S. market, it would validate the idea that what it had built wasn’t just an Australia-specific advantage. It was marketplace know-how.

Trader Interactive’s CEO Lori Stacy was explicit about the cultural fit and what she believed carsales would unlock:

"I've worked with the carsales leadership team over the last 12 months and I have been extremely impressed. We can see how compatible we are from a culture and strategy perspective. The backing of carsales, along with their domain expertise from their worldwide marketplace portfolio, will enable us to accelerate innovation across all of our verticals."

The early read-through in CAR Group’s reporting was encouraging: North American revenue grew 10% to AUD308 million, despite softer macroeconomic conditions.

But for investors, the U.S. question didn’t disappear—it just changed shape. Is Trader Interactive primarily a high-quality standalone franchise that justifies the price on its own merits? Or is it a beachhead for something bigger in U.S. automotive?

The eventual answer to that will determine whether this becomes one of CAR Group’s most valuable strategic moves—or simply an expensive way to buy “presence” in the world’s biggest market.

IX. Inflection Point #5: Becoming CAR Group (2023)

By 2023, the company still called carsales had outgrown its name. It now held majority ownership of Webmotors in Brazil, full ownership of Encar in South Korea, Trader Interactive in the United States, and chileautos in Chile. The Australian carsales brand was no longer the whole story—it was just the biggest chapter in a much bigger book.

So in 2023, carsales.com Limited renamed itself CAR Group Limited. The distinction matters: the Australian marketplace and consumer brand remained carsales, but the ASX-listed parent—owning and controlling the portfolio across Australia, Brazil, Chile, South Korea, and the U.S.—became CAR Group.

This wasn’t a marketing refresh. It was a declaration of identity. The business was no longer “Australia first, international second.” It was a global marketplace operator that happened to be headquartered in Melbourne.

And it backed that declaration with substance.

In April 2023, carsales acquired a further 40% stake in Webmotors.

ONLINE automotive platform Carsales.com.au aimed to increase its presence in the world’s fifth biggest auto market by raising $500 million to buy a further 40 per cent of Brazilian automotive digital marketplace Webmotors. The purchase would see Carsales become Webmotors’ 70 per cent majority owner. The seller, Banco Santander, would dilute its interest in Webmotors to 30 per cent from its current 70 per cent share.

Strategically, this step-up in ownership mattered because Brazil mattered. It’s the world’s fifth-largest automotive market, with long-term tailwinds as income levels rise and vehicle ownership expands. Webmotors also had a strong track record of performance, with revenue up 23 per cent to $100.5m in calendar 2022, and EBITDA in 2022 of $40.7m—contributing to 28 per cent EBITDA compound annual growth since 2017.

Just as important: this wasn’t CAR Group going it alone. The partnership structure with Banco Santander created another layer of value. Santander retained commercial exclusivity for finance products sold through the Webmotors platform, giving the marketplace a built-in channel for monetisation while CAR Group focused on running and growing the core marketplace.

McIntyre described CAR Group’s first year as majority owner of Webmotors as “outstanding.” “Aside from delivering exceptional performance outcomes, our partnership with Santander is stronger than ever,” he said. CAR Group lifted its stake in Webmotors to 70 per cent last year, leaving global consumer bank Santander with the remaining 30 per cent.

The market liked the clarity too. Shareholders endorsed the corporate rebrand overwhelmingly: “Shareholders at its recent annual general meeting voted overwhelmingly – 99.49 per cent in favour – to adopt the name Car Group Ltd.”

For investors, the name change crystallised what the last decade of deals had already made true: CAR Group’s future growth is increasingly international. Australia remains the foundation—a dominant, highly profitable franchise that throws off the cash to fund expansion. But the next leg of the story is offshore. To understand CAR Group now, you have to follow a portfolio across multiple countries, each with its own competitive dynamics, regulations, and growth curve.

X. The Business Today: A Global Portfolio

By late 2025, CAR Group isn’t just an Australian success story with a few offshore options. It’s a genuinely global marketplace portfolio—bringing in more than a billion Australian dollars in annual revenue, and doing it with the kind of profitability that makes you stop and double-check the math.

In the 12 months to June 2025, the group delivered double-digit growth across most of the business. Revenue rose 12% year-on-year to AUD1.1 billion. EBITDA increased 12% to AUD641 million. Net profit after tax grew 10% to AUD275 million.

The more interesting part is where it’s coming from—and what that mix says about the company now.

Australia is still the foundation. The flagship marketplace, carsales, extended its leadership with revenue up 8% to AUD485 million, driven by a 10% lift in dealer revenue and a 5% increase in private listing revenue.

And this isn’t “leading” in the way brands sometimes spin it. According to independent Ipsos research, carsales holds 78% share of time against category competitors—about 8.6x the nearest rivals, Drive and CarsGuide.

That dominance shows up where it matters most: in margins. CAR Group posted a 53% EBITDA margin, slightly higher than the prior period. In almost any industry, that’s remarkable. In marketplaces—where scale should turn into operating leverage—it’s what “near fully built” looks like.

North America, the newest major pillar, held up well despite softer macroeconomic conditions. Revenue grew 10% to AUD308 million. Trader Interactive has proven resilient, riding on Americans’ sustained appetite for RVs, motorcycles, and commercial and outdoor equipment—categories that can keep moving even when new car demand gets choppy.

Latin America was the standout. Revenue grew 26% to AUD205 million, driven by what the company called “outstanding growth” at Webmotors in Brazil. The long-term attraction here is straightforward: Brazil is a huge automotive market, and it’s still earlier in the shift toward digital marketplaces than mature economies—meaning the runway is long if Webmotors keeps executing.

South Korea kept compounding too. Revenue rose 16% to AUD136 million, supported by strong growth in Encar’s Guarantee inspection product. It’s a reminder that the best vehicle marketplaces aren’t just listing sites; they win by building trust in used-car transactions, and inspections and certification are a powerful way to do that.

Across all of this, CAR Group benefits from a structural tailwind in its positioning: it’s heavily geared to used vehicles, which tend to be less cyclical than new car sales. When budgets tighten, many consumers trade down from new to used. When confidence returns, transaction volume rises across the board. Either way, the used market stays active—and the marketplace that owns the starting line tends to keep winning.

And then there’s the glue that’s easy to miss if you only look at consumer traffic: dealer software.

Designed to help dealers develop and grow online sales, AutoGate is used by over 5,000 dealers across eight different industries and comes standard with every carsales Network subscription.

That matters because it turns carsales from “a place you advertise” into part of how a dealer operates. When a dealership runs inventory management, prospect tracking, and sales workflows through tools tied into the carsales ecosystem, switching isn’t just changing where you post listings. It means ripping out critical infrastructure. And that kind of integration doesn’t just defend the marketplace—it reinforces it.

XI. Competitive Dynamics: Porter's Five Forces Analysis

To understand how defensible CAR Group really is, it helps to stop looking at the company and start looking at the game it’s playing. One of the cleanest ways to do that is Porter's Five Forces—basically: who can enter, who has leverage, what can replace you, and how brutal the fight is inside the arena.

Threat of New Entrants: LOW to MODERATE

On paper, this should be easy. Anyone can build a website. Anyone can let people post car ads. There’s no factory to build and no fleet to buy.

In reality, the barrier isn’t technology. It’s liquidity.

Marketplaces tip. When the leading platform has enough listings to make it the obvious place to shop, buyers start there by default. And when buyers start there by default, sellers can’t afford not to list there. That self-reinforcing loop—network effects—is what turns “a site with ads” into “the market.”

Once you hit that tipping point, a new entrant isn’t competing against a product. They’re competing against habit. They have to convince sellers to accept fewer leads and longer time-to-sell, and convince buyers to accept less selection. That’s a tough sell even before you factor in what it would cost to build a brand that’s been reinforced for decades.

Carsales’ long-term marketing and brand investment matters here. It’s not just known; it’s remembered at the exact moment someone decides, “I need a car.” Replicating that kind of mental availability takes years and a lot of money—usually more than a challenger can justify when the leader already owns the majority of attention.

Bargaining Power of Suppliers (Sellers/Dealers): LOW to MEDIUM

In this marketplace, the “suppliers” are dealers and private sellers—the people providing the inventory.

Dealers are CAR Group’s biggest commercial customers, but their leverage is capped by one simple fact: the audience is concentrated. Carsales is dominant with 78% 'share of time against category competitors', around 8.6x more than the nearest competitors Drive and CarsGuide. When one platform has that much buyer attention, participation stops being a marketing choice and becomes a cost of doing business.

A dealership can try to negotiate, threaten to shift spend, or diversify. But they still need leads—and the fastest path to leads is the platform buyers already use.

Private sellers have a bit more flexibility. If you’re not in a hurry, you can list in multiple places and see what happens. But for most people, the dominant marketplace wins on the thing that matters most: getting the car sold quickly, with less friction.

Bargaining Power of Buyers: LOW

Buyers don’t pay the listing fee, so their “power” is really just where they choose to search.

But this force collapses back into the inventory advantage. Buyers want selection. The platform with the most listings becomes the default starting point, because searching anywhere else first is usually wasted effort. In other words: buyers have choice, but they don’t have much incentive to use it.

Threat of Substitutes: MEDIUM

The biggest substitute threat to carsales isn’t another purpose-built automotive marketplace. It’s Facebook Marketplace.

It’s free for private sellers, it has massive reach, and it sits inside an app people already open every day. That’s a serious advantage—especially at the low end of the market, where a paid listing fee feels more meaningful and sellers are happy to trade convenience for “free.”

Carsales, meanwhile, has remained the leading provider of online automotive classified advertising in Australia, and it continues to constrain other players like Gumtree and Cox Media. Facebook Marketplace is also a growing competitor to those platforms in the supply of automotive classifieds services.

Where carsales has held up best is where its business is strongest: higher-value vehicles and higher-consideration purchases. If you’re selling something worth $20,000, a $50–$100 listing fee is small relative to the outcome—especially if it helps you sell faster or with fewer time-wasters. And carsales can justify that fee with a more specialized experience: deeper search filters, purpose-built automotive features, and a product designed for serious intent rather than casual scrolling.

Competitive Rivalry: HIGH but Dominated

Competition is real. Gumtree, CarsGuide, Drive, and Facebook Marketplace all fight for listings and traffic, and regulators have noted that Carsales and Facebook Marketplace are likely to continue to provide significant competition in online automotive classifieds.

But the important nuance is this: the fight is intense around the edges, while the center is still owned.

Carsales’ share of time is so far ahead that rivalry doesn’t currently threaten the core model. Challengers compete for the leftover demand—specific segments, certain geographies, lower-priced vehicles, or sellers chasing “free.” Carsales, meanwhile, captures most of the value because it still captures most of the attention.

XII. Hamilton's Seven Powers Framework Analysis

Porter helps you understand the industry. Hamilton Helmer’s Seven Powers helps you understand the specific company—what’s actually durable, and why. On that score, CAR Group shows up surprisingly well across most of the framework.

1. Network Effects: STRONG

The simplest way to describe CAR Group’s core advantage is the oldest marketplace truth: liquidity creates more liquidity.

As more sellers list vehicles, buyers get better selection and show up more often. As more buyers show up, sellers get more leads and sell faster. That loop is self-reinforcing, and once a marketplace crosses a critical mass, it becomes the default starting point.

That’s why network effects are CAR Group’s primary moat. In its core markets, its platforms have reached the point where a competitor would need to win both sides at once—buyers and sellers—at meaningful scale. And the bigger the incumbent gets, the more expensive that proposition becomes.

2. Scale Economies: MODERATE

CAR Group’s product looks digital, but the cost structure behaves like a scaled infrastructure business.

Technology development, marketing, sales teams, and data assets come with high fixed costs. Once you’ve built them, every incremental listing, lead, and transaction becomes cheaper to serve. That operating leverage is visible in the group’s results: in the 12 months to 30 June 2024, reported revenue rose 41% to $1.099bn, and EBITDA rose 42% year-on-year to $568 million.

The strategic implication is more important than the numbers. High profitability funds more investment in product, marketing, and acquisitions—which then reinforces scale, which then reinforces profitability. It’s a flywheel built on leverage.

3. Switching Costs: STRONG

For dealers, carsales isn’t just an advertising channel. Over time, it’s become embedded infrastructure.

Switching away means more than turning off a subscription. It means abandoning integrated systems like AutoGate, losing access to RedBook data, and rebuilding prospect and inventory workflows. AutoGate sits at the center of dealer operations, supporting hundreds of sales transactions every day and helping dealers make smarter inventory decisions and streamline business processes.

The deeper those tools are woven into a dealership’s routine, the more painful switching becomes. CAR Group has leaned into this deliberately: expand the dealer toolset, increase share of wallet, and make “leaving” feel like ripping out a core system.

4. Counter-Positioning: MODERATE (Historical)

Carsales benefited from a classic counter-positioning advantage: incumbents couldn’t fight back without hurting themselves.

Newspapers didn’t win because the content was magical; they won because they controlled distribution through printing presses and delivery networks. Carsales attacked that profit pool directly. To respond effectively, newspapers would have needed to accelerate the shift online—which would have cannibalized their own print classifieds, the very engine funding the business.

That advantage was strongest early. Today, with print classifieds effectively dead, it matters less. But a version of the same dynamic still exists in the broader automotive ecosystem: incumbent players like dealers and OEMs face trade-offs if they try to build marketplace-style products that undermine existing channels.

5. Cornered Resource: MODERATE

RedBook is a genuine cornered resource.

It’s recognised as the leading supplier of independent new and used vehicle values in Australia, with pricing that adjusts for condition, kilometres, and factory options across the vehicles in the Australian market. That depth comes from decades of accumulated data and market intelligence—an asset base competitors can’t quickly replicate.

And it’s not just a consumer feature. That data feeds B2B services used by dealers, financiers, and insurers, embedding CAR Group deeper into the industry’s decision-making.

6. Process Power: MODERATE

A quiet advantage inside CAR Group is how it turns “portfolio” into process.

A meaningful portion of revenue is underpinned by recurring subscription relationships through multi-year dealer and OEM arrangements, which reduces volatility. And as the group operates across regions, it can reuse product and capabilities across markets—lowering R&D per market and speeding up rollout of trust and pricing tools.

In practice, CAR Group has been able to take products built in one geography and deploy them in another. The dynamic pricing engine developed for Australia has been deployed in Brazil and the US. Inspection and certification products built in Korea are being adapted elsewhere. That kind of cross-market transfer is hard for single-country competitors to match.

7. Branding: STRONG

Carsales is a brand that behaves like a moat.

The company has consistently invested in sales and marketing to stay top of mind, generating high engagement and strong advertising ROI for customers. In Australia, that has translated into something close to category ownership: when people think “buy a car,” they think carsales.

After more than two decades of sustained marketing investment, that brand equity does two things at once. It creates preference—so the audience starts there—and it protects pricing power by making paid listings feel like the default path for serious sellers, not an optional upgrade.

XIII. Business & Investing Lessons: The Playbook

CAR Group’s journey—from a Melbourne startup built around a “small idea” to a global portfolio of vehicle marketplaces—leaves behind a surprisingly repeatable playbook. Not just for entrepreneurs building marketplaces, but for investors trying to recognise them early.

Lesson 1: First-mover advantage matters in network-effect businesses

Carsales wasn’t alone in trying to drag car classifieds onto the internet in the late 1990s. But it moved early, it went out and built supply the hard way, and it invested heavily to get to critical mass before others did.

And once that flywheel started turning, the rules changed. The leader didn’t just win customers—it became the default, and the default became the moat. Competition didn’t stop, but it increasingly happened around the edges.

For investors, the implication is simple: in the early innings of a marketplace, the most important signals often aren’t the financial ones. Watch for liquidity, engagement, and the subtle signs of tipping—when buyers stop “checking around” and sellers stop questioning whether it’s worth listing.

Lesson 2: Geographic boundedness creates acquisition opportunities

A key strategic unlock for CAR Group was recognising that vehicle marketplaces are local by nature. That meant international expansion wasn’t going to look like copying carsales.com.au into new countries and hoping it caught on. The smarter move was to partner with—or acquire—the leading local player, keep what worked locally (including brands), and add technology and operational discipline from the group.

That insight travels beyond automotive. For investors, it’s worth asking: is this marketplace truly global, or does the product behave differently once you cross borders—because of regulation, logistics, local trust, language, or buying habits? If it’s bounded, the path to global scale often runs through a roll-up strategy, not a “one product to rule the world” strategy.

Lesson 3: Data can be a real moat—not just a feature

The RedBook acquisition wasn’t just an add-on. It was infrastructure.

By owning a trusted source of vehicle pricing and identification data, CAR Group embedded itself into the workflows of dealers, financiers, and insurers—participants who don’t just show up for a listing, but rely on data to make decisions. That kind of dependency makes the marketplace stickier and harder to replace, even if a competitor copies the front-end experience.

For investors, it’s a reminder to look past the consumer site. The durable marketplaces often own the data layer underneath, and that data layer can become the real switching-cost engine.

Lesson 4: Leadership transition can be done—if you treat it like a project

Founder-to-CEO transitions are where a lot of tech stories wobble. Carsales didn’t, because it didn’t treat succession as a sudden event.

Roebuck and McIntyre had a long runway together, deep internal credibility, and alignment on strategy. The result was continuity without stagnation—founder energy becoming a professionalised operating machine, without breaking what made the business work.

For investors, succession planning isn’t a footnote. It’s a real risk factor. When a company is founder-led, understanding whether the bench exists—and whether there’s time for a handover—matters.

Lesson 5: Stay in your lane (but define your lane broadly)

Quicksales was a useful failure. It showed that “we run a marketplace” isn’t a strategy on its own. Carsales’ edge wasn’t generic marketplace mechanics—it was deep vehicle expertise, dealer relationships, and vehicle-specific tooling and data.

The smart pivot wasn’t to narrow the vision. It was to broaden the lane in a way that still fit the advantage: vehicles and adjacent categories where the same muscles mattered. Cars, yes—but also boats, bikes, RVs, trucks, and equipment.

For entrepreneurs, that’s the balance: don’t confuse focus with smallness. The best version of “stay in your lane” is “expand where your unfair advantage still applies.”

XIV. Key Metrics and Investor Considerations

If you’re following CAR Group as an investment, the story is ultimately going to show up in a few recurring metrics. Not because they’re flashy, but because they tell you whether the moat is deepening—or quietly starting to leak.

1. Average Revenue Per User/Dealer (ARPU/ARPA)

In a marketplace that already dominates, growth increasingly comes from revenue intensity: how much value the platform can earn from each dealer or seller without breaking the experience that made it dominant in the first place.

CAR Group has pushed ARPU upward by layering on tiered products like premium placements and deeper advertising, plus ancillary services such as inspections and finance, and then reinforcing it all with pricing that can adjust dynamically.

The investor lens here is simple. If ARPU keeps rising while dealer and user participation stays stable (or grows), that’s pricing power. If ARPU rises while participation slips, that can be the warning sign of over-monetisation—pushing too hard, too fast, and giving dealers or private sellers a reason to experiment elsewhere.

2. Audience Metrics (Sessions, Page Views, Time on Site)

Marketplace value starts with attention. If buyers stop showing up, everything downstream gets harder: dealers get fewer leads, private sellers take longer to sell, and the platform’s pricing power weakens.

In its FY25 full-year presentation, CAR Group reported publishing 2.3 million vehicles online, generating 19 billion page views, reaching 49 million unique audience members per month, and serving 49,000 subscribed dealers.

What matters isn’t just the scale—it’s the direction. If engagement trends down, it can be an early indicator of competitive pull (for example, more browsing shifting to Facebook Marketplace) or a product that’s losing its edge. If engagement stays strong, it’s the clearest signal that the network effects remain healthy: the audience is there, so sellers have to be there too.

3. Geographic Revenue Mix

CAR Group is no longer a one-country story, so investors can’t analyze it like one. With more than half of revenue now coming from outside Australia, the regional mix tells you how the portfolio is evolving—and what the risk profile looks like.

Australia is the engine room: stable, high-margin cash flows. International markets are the growth bet. The real question is whether those offshore businesses, bought with serious capital, mature into profitability that looks like Australia over time.

Brazil and the U.S. in particular carry the “prove it” burden. They’ve required billions in deployed capital, so the long-term investment case depends on those assets earning attractive returns—not just growing revenue, but converting that growth into durable, defensible profitability.

XV. Looking Forward: Bulls, Bears, and the Path Ahead

The Bull Case

At a high level, the bull case for CAR Group is simple: it owns leading marketplace positions in multiple big markets, and the industry is still migrating online.

Used cars are a massive global category, and in many places, the buying and selling experience is still more analog than people assume. As more of that activity shifts to digital, the platforms that already sit at the start of the journey—where buyers browse and sellers list—should capture a growing share of the value.

CAR Group also has the kind of financial profile investors love in marketplaces once they’ve reached maturity: strong margins, strong cash generation, and low capital intensity. In theory, that gives the company flexibility—funding acquisitions without constantly leaning on equity markets, while also returning capital to shareholders through dividends.

The biggest upside lever is international. Brazil, in particular, has been positioned as a source of real optionality. In Latin America, pro forma revenue increased 31 per cent, while pro forma EBITDA rose 39 per cent. If Webmotors can deepen its leadership position in a way that starts to resemble what carsales achieved in Australia, the equity value creation could be meaningful.

And there’s a continuity argument too. As the company has noted about Cameron McIntyre’s tenure: "During his time as CEO, the group has become over five times larger, is now an ASX top-50 company and is included in the MSCI index. He has built a high-performing leadership team and globalised the group with almost 60% of the business based offshore."

The Bear Case

The clearest near-term threat is the one we’ve already been circling: Facebook Marketplace.

Carsales built its Australian dominance in a world where purpose-built classifieds sites were the main alternative to newspapers. Facebook changes that equation. It brings enormous distribution, zero listing costs, and built-in messaging. It’s not just a competitor with a different product. It’s a competitor with a different starting advantage: attention.

So far, carsales has defended its position. But if Facebook ever decided to get serious about automotive—adding vehicle-specific search and filters, better trust and verification, and tools designed for dealers—the competitive dynamic could shift quickly.

There’s also execution risk offshore. The U.S. entry through Trader Interactive was a deliberate departure from the historical playbook. Instead of buying the leading car marketplace, CAR Group bought a leader in adjacent verticals like RVs, powersports, and equipment. The strategy makes sense as a “land and expand” move, but the expansion part—especially anything that resembles a major push into U.S. automotive—has uncertain timing and uncertain difficulty.

And the U.S. is where competitive intensity can surprise you. CAR Group might be a great Australian success story, but it could face its biggest test yet in the form of a massive U.S. disruptor called Carvana.

Finally, valuation is its own risk. CAR Group trades on premium multiples because it has premium characteristics. That’s fine—until growth slows or competition bites. If either happens, multiple compression can create real downside even if the underlying business remains healthy.

Leadership Transition Considerations

The other variable investors have to underwrite is leadership.

Longtime CEO Cameron McIntyre is retiring after nearly two decades with the business. CAR Group said William Elliott was selected as CEO as part of a succession planning process implemented by McIntyre and the board, designed to identify internal and external talent and manage “future succession events.”

McIntyre has been appointed Chief Executive Officer of REA Group Ltd, effective 3 November 2025, succeeding Owen Wilson. He served as Managing Director and CEO at CAR Group Limited, owner of carsales, for nine years until 15 August 2025.

This makes Elliott the second major leadership change in CAR Group’s history. The company said Mr Elliott “brings deep financial expertise, strong commercial acumen and a clear strategic vision for the future.” It added: “He has already made a significant impact across the group, and we are confident he will lead Car Group.”

XVI. Conclusion: The Melbourne Marketplace Empire

Twenty-seven years ago, Greg Roebuck sat at his kitchen table, staring down the Saturday classifieds and thinking: there has to be a better way. That “small idea” became carsales. Carsales became CAR Group. And what started as a scrappy attempt to move print listings onto the internet turned into a global vehicle marketplace portfolio, spanning five continents, producing more than a billion Australian dollars in annual revenue, and doing it with profit margins most businesses never touch.

What makes this story so enduring is that it isn’t built on a single breakthrough. It’s built on a sequence of repeatable, hard-to-copy decisions. They went after a real, everyday pain point. They delivered a step-change improvement over newspapers. They solved the chicken-and-egg problem the unglamorous way—one dealer visit at a time—until the flywheel finally tipped. Then they kept investing to stay top of mind, and they deepened the moat with the less visible infrastructure: data, dealer tools, and acquisitions that consolidated leadership positions rather than chasing novelty.

They also showed a rare kind of discipline. Quicksales was a reminder that not every marketplace is the same. The international expansion proved the opposite lesson: if marketplaces are geographically bound, then the fastest path to global scale isn’t “copy and paste,” it’s “buy the local winner and make it stronger.” And the founder-to-professional management handoff—another moment where plenty of tech stories wobble—became a point of continuity instead.

For long-term fundamental investors, CAR Group sits in an uncommon spot: genuine network effects, dominant positions in core markets, exceptional profitability, and real optionality offshore. The risks are equally real—Facebook Marketplace has changed the competitive baseline for classifieds everywhere—and the international portfolio still has to keep proving it can compound returns at scale. But the fortress that’s been built over nearly three decades is not a flimsy one.

As CAR Group moves into its next chapter under new leadership, the real question isn’t whether this is a quality business. It’s whether the price you pay today fairly reflects both the opportunities ahead and the threats that come with them. In a world where true network-effect businesses are rare—and durable marketplace leadership is rarer still—CAR Group is the kind of company that demands to be studied.

The Melbourne startup that helped kill the newspaper classifieds section has come a very long way. Where it goes next—deeper into existing markets, broader into new ones, or further into adjacent vehicle categories—will decide whether the next act can match the first.

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music