Singapore Airlines: The Tiny Island's Global Airline Empire

I. Introduction & Episode Roadmap

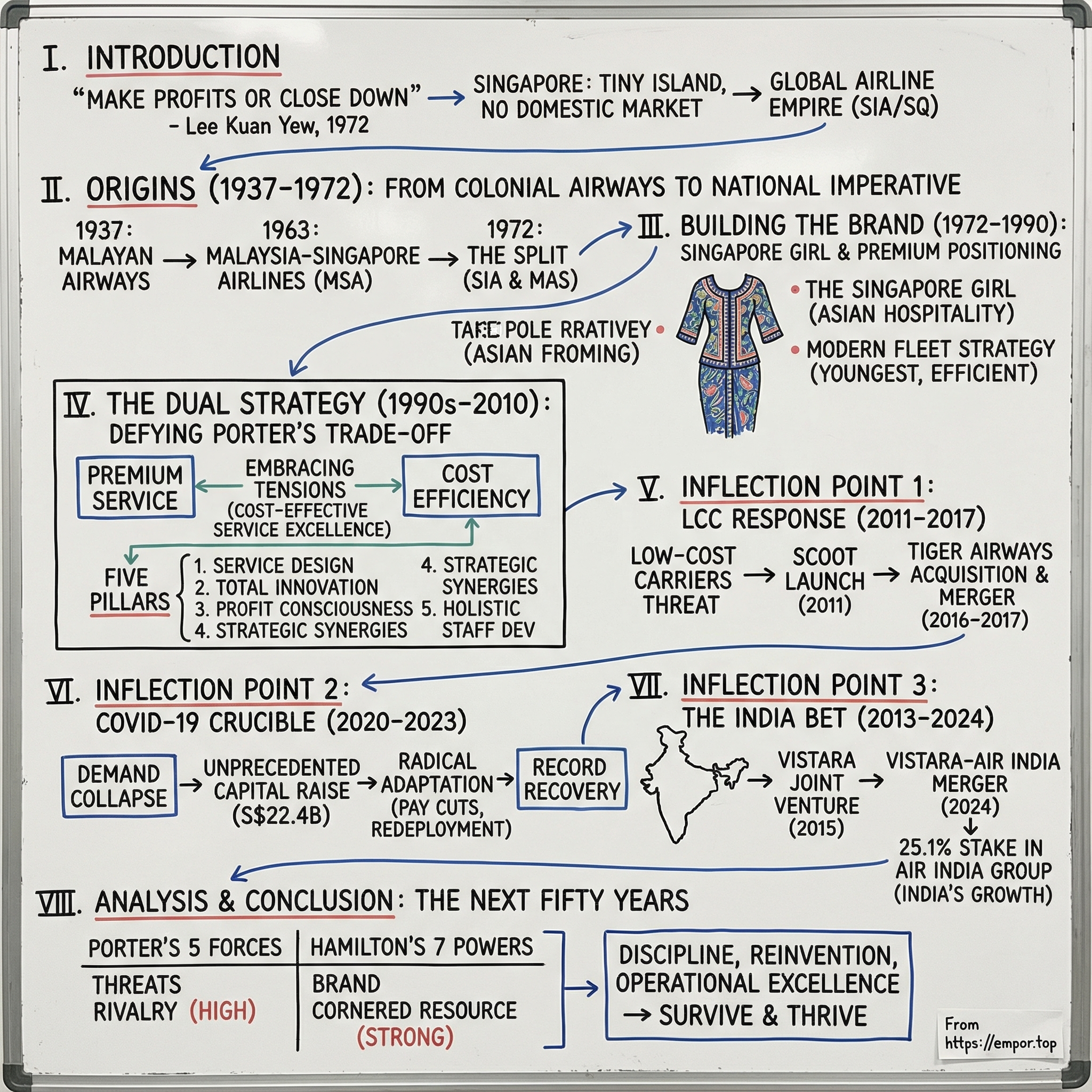

On a humid October afternoon in 1972, Prime Minister Lee Kuan Yew called in the leaders of a brand-new airline and set the tone in a single sentence. “I set up Singapore Airlines to make profits,” he said, flatly. “If you don’t make a profit, I am going to close down the airline.”

It wasn’t a metaphor. Singapore had just split from Malaysia, and the new country was tiny—barely 700 square kilometers, no natural resources, and no margin for error. Its survival plan was to become a global hub for trade, finance, and talent. And the airline wasn’t just transportation; it was the nation’s flying proof point. A visible signal to the world that this place could run world-class operations—and could be trusted by multinationals deciding where to put their factories, offices, and capital.

Fast forward to today. Singapore Airlines—SIA, or SQ—flies from its home base at Changi Airport and has spent decades near the top of global airline rankings. Skytrax has rated it a 5-star airline for years, and it’s been named World’s Best Airline five times. On May 15, 2025, the Singapore Airlines Group reported the highest annual profit in its 53-year history under the SIA name: net profit of US$2.78 billion, up 3.9% from the year before.

And yet the part that makes SIA so unusual isn’t the awards or the financials. It’s the starting position.

Most major airlines have a home market they can fall back on: American Airlines can fill planes on domestic routes; Lufthansa has Europe; Qantas has Australia’s huge internal network. Singapore Airlines had none of that. No domestic routes. No natural “base load” of passengers. No easy way to grow by simply adding more flights between cities inside the same country.

There were no quick trips from Singapore to Singapore. The only way forward was up—literally and figuratively.

That constraint made SIA unusually dependent on international demand, and unusually exposed whenever borders tightened and cross-border travel slowed. If the world stopped moving, Singapore Airlines didn’t just feel it. It could be starved.

So this is the story we’re going to tell: how a city-state with no domestic market built one of the world’s most admired airlines through relentless innovation, operational excellence, and constant reinvention. Along the way, we’ll see how SIA pulled off what strategy professors love to call impossible, how it survived a once-in-a-century shutdown during COVID, and how it made a huge, complicated bet on India—via a merger that only wrapped up last month.

II. Origins: From Colonial Airways to National Imperative (1937-1972)

Singapore Airlines’ story doesn’t begin with a national flag on a tailfin. It starts in colonial Singapore, in the orbit of shipping and empire, when British business interests saw aviation as the next way to stitch together far-flung trading posts.

In 1937, the Straits Steamship Company of Singapore teamed up with two British firms—the Ocean Steamship Company and Imperial Airways—to form Malayan Airways. The idea was straightforward: build a regional airline linking Singapore with British Malaya. Malayan Airways Limited was incorporated on 21 October 1937, but the early years were more paperwork than airplanes. Management quickly realized it would be difficult to compete with Wearne’s Air Service, which already dominated local routes, and the venture largely stalled.

Then World War II arrived and froze commercial aviation entirely. It took a full decade for the ambition to thaw. On 1 May 1947, Malayan Airways finally began operations. Its first flight was a charter from Singapore to Kuala Lumpur on 2 April 1947, and it wasn’t long before the airline was running weekly scheduled services to places like Ipoh and Penang. Demand snapped back hard after the war. Early Singapore–Kuala Lumpur services were fully booked, the fleet grew to include three DC-3s by the end of 1947, and within a year the airline was carrying 5,000 passengers a month.

The Geopolitical Split

If the early challenge was commercial, the defining challenge of the 1960s was political—and it would reshape the airline far more than any competitor ever could.

When Malaya, Singapore, Sabah, and Sarawak formed the Federation of Malaysia in 1963, the airline was renamed from Malayan Airways to Malaysian Airways. Two years later came the rupture: in 1965, Singapore was expelled from the federation after two years of political tensions.

By 1972, the joint airline structure could no longer hold. Malaysia-Singapore Airlines (MSA) ceased operations, replaced by two new carriers: Singapore Airlines and Malaysian Airline System. The logic was strategic and irreconcilable. Singapore wanted to push outward—more international routes, more global connectivity. Malaysia wanted to build up domestic aviation first, then expand abroad.

The breakup was anything but gentle. Assets were carved up. Malaysia’s new carrier received the Friendship Fleet, Britten-Norman aircraft, equipment based in Malaysia, and the domestic routes within Malaysia. Singapore received the Boeing aircraft, the corporate headquarters building, hangars and maintenance facilities at Paya Lebar Airport, the computer reservation system, and most of the overseas offices. It also took over MSA’s international network—22 cities across 18 countries.

So Singapore Airlines began life with a real foundation: MSA’s Boeing 707s and 737s, international routes out of Singapore, and the existing headquarters in the city. Leading it was J.Y. Pillay, MSA’s former joint chief, appointed as Singapore Airlines’ first chairperson.

Pillay didn’t look like aviation glamour. He was wiry, slight, soft-spoken—more intellectual than instinctive, more comfortable with policy than with showmanship. But that was exactly what this moment required. Pillay had a talent for stripping problems down to their essence, breaking them into parts, and building specific solutions for each one. In an industry where small mistakes compound into huge failures, that kind of clarity is a superpower.

Even with planes, routes, and a leader, the new airline had a credibility problem. Singapore was tiny. To many in the West, it was barely a dot. Singapore Airlines was dismissed as an upstart—called a maverick, even a pirate. And established players didn’t just sneer; they pushed back. In 1981, West Germany campaigned against SIA for selling discounted tickets. German tax officials reportedly visited SIA offices in Frankfurt and Düsseldorf five times, and checks on SIA flights became more frequent—causing delays, and embarrassing passengers in public.

The biggest prize, though, was London. When Britain refused to grant landing rights there, Singapore turned it into a matter of principle. The British high commissioner went to Prime Minister Lee Kuan Yew, and Lee responded with blunt reciprocity: a British airline could land in Singapore, so why was a Singapore airline denied London?

Within weeks, SIA secured landing rights in London, opening up one of the world’s main trunk routes: London–Singapore–Sydney. As Lim later put it, “Once we did that, all the European countries got in line. So, we got London, we got Paris.”

Lee Kuan Yew’s hard-edged diplomacy and Pillay’s operational precision fused into an institutional personality—commercially aggressive, relentlessly meticulous—that would shape Singapore Airlines for decades.

III. Building the Brand: The Singapore Girl & Premium Positioning (1972-1990)

In the summer of 1972, a young British advertising executive named Ian Batey walked into a problem that would define his career. Singapore Airlines had just been born, and it needed an identity—immediately. The airline world was dominated by incumbents like British Airways and Qantas, carriers with decades of reputation behind them. SIA was a newcomer from a tiny country that much of the world barely understood. If it was going to win, it couldn’t just announce routes and fares. It needed to mean something.

When Malaysia and Singapore terminated their joint operating agreement for Malaysia-Singapore Airlines and Singapore moved to set up its own carrier, Batey pitched for the account, won it, and opened shop to handle SIA’s advertising. What he built became aviation’s rarest thing: a brand platform that lasted. He is credited with creating the “Singapore Girl” campaign—often described as the most successful airline advertising campaign ever—because it was never just advertising. It was the airline’s positioning made human. The Singapore Girl wasn’t a character on a poster; she was the promise of superior in-flight service, turned into an instantly recognizable symbol.

The visual anchor was the uniform. Singapore Girl was coined in 1972 as Pierre Balmain, the French haute couture designer, was brought in to construct and update the sarong kebaya worn by cabin crew. The outfit itself wasn’t invented from scratch. Malaysia-Singapore Airlines had introduced an earlier traditional version in 1968. But Batey and Balmain refined it into something sharper: a distinctive, elegant shorthand for Asian hospitality that could register in a single glance, whether you were in Tokyo, London, or Sydney. From 1972 onward, the image of the Singapore Girl appeared in SIA advertising around the world, and the uniform became one of the most recognized in aviation.

What made it work was how it cut through a commoditized category. Most airlines at the time sold geography: exotic destinations, new cities, more frequencies. Batey told SIA that a destination campaign wouldn’t be enough. Instead, the agency built the story around two pillars. First: best-in-class service, embodied by the Singapore Girl. Second: a young, modern fleet—an operational choice that would later be tied to on-board upgrades and entertainment innovations as the years went on.

The Singapore Girl came to represent “Asian values and hospitality,” and was described as “caring, warm, gentle, elegant and serene.” The icon eventually took on a life of its own: in 1994, a wax figure of the Singapore Girl was displayed at Madame Tussaud’s in London, the first figure there to represent a commercial undertaking.

And the campaign did what it was designed to do. Batey’s ads—featuring sarong-clad SIA flight attendants and the line, “Singapore Girl, you’re a great way to fly”—helped establish Singapore Airlines as the No. 6 international carrier by 1987.

Fleet Modernization as Strategy

The Singapore Girl made the promise. The fleet strategy made it believable.

From the start, Singapore Airlines made a decision that would become a hallmark: operate one of the youngest, most modern fleets in the industry. It wasn’t glamour for its own sake. New planes are more reliable, more fuel-efficient, and easier to keep consistent—exactly what you want when your brand is built on trust, punctuality, and a premium experience that can’t afford “off days.”

After the split from MSA in 1972, SIA expanded quickly, adding cities across Asia and the Indian subcontinent and bringing in new aircraft, including Boeing 747s. The first two 747s arrived in the summer of 1973 and went straight onto a high-profile route: Singapore–Hong Kong–Taipei–Tokyo. By 1976, SIA operated an all-Boeing fleet of 21 aircraft—737-100s, 707-300s, and 747-200s—and its passenger network spanned 28 cities in 23 countries, from London in the northwest to Auckland in the southeast.

In 1989, SIA became the first airline to fly the Boeing 747-400 across the Pacific. That wasn’t just bragging rights. It was the young-fleet philosophy in action: newer aircraft lowered fuel and maintenance costs, improved schedule reliability, and made the product feel consistently modern—especially important when you’re selling “premium” to people who can choose anyone.

Service innovations reinforced the same story. In the early 1970s, SIA became the first airline to offer complimentary headsets, drinks, and meal choices to economy passengers—things that sound ordinary now, but were a clear signal then: this airline was going to treat economy like a product worth designing, not a cabin to be tolerated.

Internally, the logic was simple and concrete: keep the fleet young, and you can deliver quality more cost-effectively. SIA would later describe its average fleet age as around six years, compared with an industry average closer to fifteen. That gap—roughly a decade of difference—became one of the most durable advantages the airline built in its early years.

IV. The Dual Strategy: Defying Porter's Trade-off (1990s-2010)

In 1985, Harvard Business School professor Michael Porter published Competitive Advantage, the strategy book that helped define how executives talked about competition for the next generation. Its big idea was clean and comforting: you pick a lane. Either you differentiate—charge more by offering something meaningfully better—or you lead on cost—be the low-price, high-efficiency machine. Try to do both, Porter argued, and you end up “stuck in the middle,” not great at anything.

Singapore Airlines, apparently, never got the memo.

For years, SIA delivered a premium experience and a premium reputation, while also running with an efficiency that showed up in the numbers and in how the company operated day to day. Many management experts argued that a “dual strategy” like this can’t last, because the investments and behaviors required for each approach tend to collide. SIA’s answer was to treat those contradictions not as a trap, but as a system to be managed.

Researchers Loizos Heracleous and Jochen Wirtz described SIA’s model as “cost-effective service excellence.” In plain language: service so good people notice, delivered in a way the company can afford—over and over, at scale. They argued SIA pulled it off by embracing four tensions at once: delivering service excellence without letting costs spiral, balancing centralized control with decentralized innovation, knowing when to lead on technology and when to follow, and using standardization to enable personalization.

Underneath those paradoxes sat an organizational blueprint built on five pillars.

The Five Pillars

First, rigorous service design and development. SIA didn’t treat service as something you either “have” or “don’t have,” depending on which crew shows up that day. It treated service like an engineered product. Key moments in the journey were designed deliberately, tested, refined, and rolled out with discipline—so the experience could be consistent across routes, aircraft, and years.

Second, total innovation. At SIA, innovation wasn’t just about shiny passenger-facing upgrades. It also meant process changes, training improvements, and tighter supplier relationships—anything that improved the experience or made operations run better. The point wasn’t innovation for its own sake; it was that many improvements could do double duty. The young-fleet philosophy is a perfect example: newer aircraft feel better to fly on, but they also burn less fuel, break less often, and cost less to maintain.

Third, profit consciousness ingrained in all employees. In many airlines, cost control arrives as an emergency measure from headquarters when times get tough. SIA pushed the opposite idea: efficiency is everyone’s job, all the time. The result was a culture where frontline teams looked for ways to reduce waste and improve flow, while leadership maintained tight strategic control over big cost drivers.

Fourth, strategic synergies across the group. SIA built capabilities that could serve more than one purpose. SIA Engineering, for example, supported the airline’s own fleet and did work for third-party carriers—turning what could have been a pure cost burden into a business. Training infrastructure served the parent airline and subsidiaries. Shared resources helped spread fixed costs across a broader base.

Fifth, holistic staff development. SIA invested heavily in training—more than most competitors—but paired that with compensation structures that included meaningful variable components tied to company performance. The intent was alignment: great service isn’t just a slogan; it’s something employees have a stake in delivering, because the airline’s performance feeds back into theirs.

Put differently, it’s not hard to buy great service by spending freely. And it’s not hard to run cheaply if you don’t care much about the product. What’s rare is the combination: a premium airline that stays efficient, year after year, in an industry that punishes even small mistakes.

That’s what made SIA so confounding—and so admired. For decades, it stacked service awards and financial outperformance in one of the most brutal competitive environments in the world. And it did it without the safety net most airlines rely on. No domestic market. No captive base load. Just organizational design that made the “either/or” trade-off look, at least in Singapore, more like a false choice.

V. First Inflection Point: The Low-Cost Carrier Response (2011-2017)

In January 2011, Goh Choon Phong sat down in the CEO’s chair at Singapore Airlines’ Airline House headquarters and stared straight at an uncomfortable truth: the premium playbook that had carried SIA for decades was no longer enough on its own.

Goh wasn’t a classic “airline lifer” in the way the industry often produces. Born in Singapore in July 1963, he studied at Hwa Chong Junior College before heading to MIT, where he trained in Electrical Engineering and Computer Science, with a focus spanning computer science, management science, and cognitive science. He earned a Master of Science in the same field, then joined Singapore Airlines as a cadet administrative officer—fulfilling a sponsorship the airline had offered him.

Inside SIA, he moved through roles that were less about flight ops and more about the systems that make a global airline work: Senior Vice President of Commercial Technology, Senior Vice President of Information Technology, then Executive Vice President of Marketing. He also served as Chairman of SilkAir, SIA’s former regional subsidiary. On 1 January 2011, he took over as CEO from Chew Choon Seng, who retired.

That technology-and-systems lens turned out to be exactly what the moment demanded. Goh saw the threat wasn’t just “more competition.” It was a structural shift in what customers expected, what they were willing to pay, and how fast low-cost carriers could scale. Airlines like AirAsia and Jetstar weren’t merely undercutting fares; they were re-teaching the market to think of flying as a commodity.

SIA’s response would be unusually direct: if the market was moving toward low cost, SIA would compete there too—even if it meant undercutting itself.

The Scoot Launch

In May 2011, Singapore Airlines announced it would create a low-cost subsidiary for medium and long-haul routes. Two months later, it named Campbell Wilson as the founding CEO.

The new airline was called Scoot—deliberately playful, and intentionally distant from the formal, polished Singapore Airlines brand. Where the Singapore Girl projected grace and serenity, Scoot leaned into cheeky, irreverent marketing that would have been unthinkable in the parent company’s voice.

Operationally, though, Scoot was born out of SIA’s machinery. Its initial fleet was six Boeing 777-200ERs transferred from Singapore Airlines. Scoot was founded on 25 May 2011, and its first flight departed Singapore on 4 June 2012 for Sydney. By 2015, the airline began transitioning its long-haul fleet to the Boeing 787 Dreamliner, with the 777s set to give way to a new order of 787s.

Wilson brought outsider energy, but with one important constraint: Scoot could be informal on the surface, but it still had to run with SIA discipline underneath.

The Tiger Airways Acquisition

Scoot alone didn’t solve the problem, because the low-cost battlefield in Southeast Asia wasn’t just long-haul. Short-haul routes were getting crowded too, and one of the loudest competitors was Tiger Airways—an airline that, in a twist of history, SIA had once owned 49% of before reducing its stake.

Tiger Airways was founded as an independent airline in 2003 and listed on the Singapore Stock Exchange in 2010 under Tiger Airways Holdings. In October 2014, Tiger Airways Holdings became a subsidiary of the SIA Group, with SIA taking a 56% stake. The direction of travel was clear: SIA wasn’t going to watch the budget segment consolidate without it.

On 18 May 2016, Singapore Airlines created Budget Aviation Holdings, a holding company designed to own and manage its budget businesses—Scoot and Tiger—following Tiger’s delisting from the Singapore Stock Exchange as SIA moved toward full control.

The Merger

Then came the cleanup. Running multiple low-cost brands with overlapping routes is how you end up competing with yourself—and SIA was doing exactly that. There were overlaps across Singapore Airlines, Scoot, and Tiger on destinations like Guangzhou, Hong Kong, and Taipei. And while Singapore Airlines and SilkAir had largely served complementary networks, the overlaps between Scoot and Tiger were significant enough to cannibalize revenue.

In November 2016, Singapore Airlines announced that Tigerair would merge into Scoot. After the merger, the combined carriers flew to 65 destinations across 18 countries.

The strategic point wasn’t subtle. This was SIA accepting that, in a region flooded with low-cost carriers, “premium-only” was a vulnerability—especially for a hub airline with no domestic market to fall back on. The consolidation left a cleaner structure: Singapore Airlines as the premium long-haul flagship, and Scoot as the budget short-to-long-haul platform, each aimed at distinct customer segments.

It also strengthened the group’s feeder engine. With a broader low-cost network across Asia Pacific, Scoot could pull travelers from regional cities into Singapore, then hand them off to Singapore Airlines for long-haul flights into the Middle East, Europe, and the United States.

And the Scoot bet didn’t just become defensible—it became award-winning. On 24 June 2024, Scoot was voted 2024 Best Long Haul Low-Cost Airline in the World by Skytrax.

The deeper signal to investors and competitors was even more important: SIA was willing to cannibalize its own business rather than let someone else do it for them. That’s what companies do when they intend to survive disruption.

VI. Second Inflection Point: The COVID-19 Crucible (2020-2023)

In February 2020, Goh Choon Phong watched the numbers slide—first ten percent, then twenty, then a figure that barely made sense: ninety-seven percent.

Singapore Airlines didn’t just see demand soften. It saw demand disappear. Monthly passenger volume collapsed from millions to barely a rounding error. By April 2020, the airline was operating at roughly 3% of its pre-COVID capacity.

For most airlines, a crisis like this is brutal. For SIA, it was uniquely dangerous. Qantas could still fly Australians around Australia. Delta could still crisscross the United States. Singapore Airlines had no domestic market to fall back on. If borders were closed, the engine stopped.

And this wasn’t a company with practice losing money. Since the airline’s founding in 1972, it had never posted an annual loss. Now it was staring at something worse than a bad year. It was staring at an existential threat.

Inside Airline House, the conclusion was immediate: they couldn’t wait this out. They needed time, and time meant liquidity. But raising money for an airline when the entire world had stopped flying was a hard sell—especially when the business was reportedly burning through up to S$400 million a month.

Lee Lik Hsin, executive vice president of commercial operations, put it bluntly. The key was persuading stakeholders to fund the airline through the storm. “Stakeholders came in to support us very strongly,” he said later. “They recognized the importance of Singapore Airlines to the Singapore hub and then to the Singapore economy as a whole.”

The Unprecedented Capital Raise

On March 26, 2020, Singapore Airlines announced a shareholder lifeline: an offer of S$8.8 billion in new shares (rights shares) and mandatory convertible bonds (rights MCBs), structured so they would be reflected as equity on the balance sheet.

It was only the beginning. From April 2020 onward, SIA reached for funding from more places than it ever had before. By the time the effort was done, the airline had raised about S$22.4 billion in liquidity, including roughly S$15 billion from shareholders through shares and convertible bonds.

“We have never had a need to reach out to so many different sources of funding,” Goh said during a May briefing. The scramble taught the organization, in real time, how to finance survival.

A huge reason the raise worked was confidence—specifically, Temasek’s confidence. At the time of the rights issue, Temasek owned about 55% of SIA. As Singapore’s state-owned investment company, Temasek framed itself as a long-term, “generational” investor. Its backing mattered not only because it brought capital, but because it signaled to everyone else that Singapore would not let its flagship airline fail.

The Singapore government reinforced that message, recognizing SIA as a strategic asset and announcing a S$750 million aid package for the aviation sector.

Radical Adaptation

Funding bought SIA time. But management still had to redesign the business for a world where planes were grounded.

Cost reductions were unavoidable. Pilots took pay cuts ranging from 10% to 60% through March 2022. Cabin crew were redeployed to hospitals and nursing homes—an extraordinary pivot that kept people employed while putting trained, service-oriented staff where Singapore needed them most.

Then came the part that reminded everyone what kind of company SIA was: even in a shutdown, it refused to go silent.

In October 2020, with A380s sitting idle, the airline turned several of them into “Restaurant A380,” letting Singapore residents book a meal onboard the world’s largest passenger jet. It also delivered signature meals to homes. None of it was meant to replace flying revenue. The point was to stay connected to customers, keep the brand alive, and prove—internally and externally—that the company could still execute.

Goh described the priority as emerging stronger, with two goals: stay ready, and be fast. The airline wanted to be “first off the block” when borders reopened—to deploy capacity immediately rather than spend months rebuilding.

That readiness mattered because Singapore began reopening earlier than many places in the region, first allowing quarantine-free entry for fully vaccinated travelers from selected countries, then rolling back most remaining restrictions. And because SIA had retained much of its workforce—pilots through pay cuts, crew through redeployment—it could ramp up faster than competitors that had shed staff and then struggled to rehire and retrain.

The Record Recovery

The damage, though, was real. Group revenue fell sharply in the 2020/21 financial year, and SIA reported a loss of S$4.27 billion. The company survived, but at a price: issuing new capital diluted existing shareholders.

Then the rebound arrived—and it arrived hard.

In May 2023, the Singapore Airlines group reported a record annual profit of S$2.16 billion, reversing three straight years of losses. The decision to protect operational capability—to keep staff, preserve fleet readiness, and prepare to scale quickly—had done exactly what it was supposed to do.

A month later, on 20 June 2023, Skytrax named Singapore Airlines the World’s Best Airline for the fifth time. Accepting the award in Paris, Goh said, “This award is a testament to the indomitable spirit of our people, who worked tirelessly and made many sacrifices to ensure that SIA was ready for the recovery in air travel.”

For most airlines, COVID was a reset. For Singapore Airlines, it was a crucible: proof that the thing it had been optimizing for all along—discipline, adaptability, and operational excellence—wasn’t just how you win in good times. It’s how you survive the worst ones.

VII. Third Inflection Point: The India Bet & Vistara-Air India Merger (2013-2024)

Singapore Airlines’ India strategy goes back to 2013, and it came from the same constraint that had shaped the airline from day one: Singapore is a hub, not a hinterland. SIA could optimize Changi, expand its network, and run one of the best operations in aviation—but it couldn’t manufacture a domestic market. If SIA wanted the next leg of growth, it had to plug itself into a much larger population and travel engine. No market offered more upside than India.

That’s where Vistara came in.

Tata SIA Airlines Limited, operating as Vistara, was a full-service airline based in Gurgaon with its hub at Indira Gandhi International Airport. It was set up as a joint venture between Tata Sons, with 51 percent, and Singapore Airlines, with 49 percent. Vistara began operations on 9 January 2015 with an inaugural flight between Delhi and Mumbai. By September 2024, it had about a 10 percent share of India’s domestic market, making it the third-largest domestic carrier behind IndiGo and Air India.

From the start, Vistara was positioned as a premium domestic airline—something closer to the Singapore Airlines experience, adapted for Indian travelers. One signal of that ambition: Vistara became the first airline in India to introduce Premium Economy on domestic routes. On its Airbus A320-200s, that meant a dedicated Premium Economy cabin—24 seats, arranged over four rows in a 3-3 layout—out of 158 total seats.

The Strategic Merger

Then, in early 2022, the ground shifted. The Tata Group acquired Air India from the government after years of state ownership and decline. Overnight, Tata found itself with two full-service airlines—Air India and Vistara—plus two low-cost carriers. In aviation, that kind of overlap doesn’t last long. Consolidation wasn’t a “nice to have.” It was inevitable.

Later in 2022, Tata and Singapore Airlines announced they would merge Vistara into Air India to drive synergies and compete more effectively in a fast-growing market. The operational and legal merger was completed in November 2024, and it left Singapore Airlines with a 25.1 percent stake in the combined Air India Group.

Post-merger, the Air India Group operated a combined fleet of 300 aircraft across 55 domestic and 48 international destinations, flying 312 routes with about 8,300 flights per week. It also offered broader global reach through more than 75 codeshare and interline partners, extending connectivity to more than 800 destinations worldwide.

Goh Choon Phong called the merger “a pivotal moment for Indian aviation,” saying the SIA Group would support the transformation of the enlarged Air India Group with “stewardship and expertise where possible.” He added that SIA was focused on helping restore Air India “to its leading position in the Indian aviation market” and building “an airline group that everyone in India can be proud of.” For SIA, he said, the deal reinforced its long-standing, direct participation in one of the world’s fastest-growing aviation markets.

The consolidation also fit into Tata’s broader plan: the five-year Vihaan.AI transformation programme, aimed at simplifying the Air India Group into one full-service airline and one low-cost airline.

The Financial Impact

For Singapore Airlines, the Vistara-Air India deal wasn’t just strategic—it was financially meaningful. With the merger completed in November 2024, SIA recognized a one-time gain of S$1.1 billion from the transaction. It also shifted from owning 49% of Vistara to owning 25.1% of the larger Air India Group, with Tata holding 74.9%.

The logic of the bet is straightforward. India is already the world’s third-biggest travel market, and it’s expected to keep growing quickly over the next decade. For an airline with no domestic base, exposure to that kind of demand is exactly the point.

This is SIA’s structural workaround in its purest form: if you can’t grow at home, you earn the right to grow by partnering into a market that can. The 25.1% stake in Air India gives Singapore Airlines a seat at the table in India’s aviation future—one with far more runway than Singapore will ever have.

VIII. Porter's 5 Forces & Hamilton's 7 Powers Analysis

To understand why Singapore Airlines has been able to outperform in an industry that usually destroys value, you have to look at two things at once: the structure of the airline business itself, and the specific advantages SIA has built to survive it.

Porter’s Five Forces Analysis

1. Threat of New Entrants: MEDIUM

Starting an airline is hard. Doing it at scale, on international routes, out of a slot-constrained hub airport is even harder. You need enormous upfront capital, regulatory approvals, aircraft, trained crews, gates, and—most scarce of all—takeoff and landing slots at the airports that actually matter.

Singapore’s position helps here. Changi is one of Asia’s most connected hubs, linking Singapore to more than 160 cities through around 100 airlines. In 2024, 13 of Changi’s top 15 routes were within Asia-Pacific, reflecting just how dense and competitive the regional battlefield is.

But “hard” doesn’t mean “impossible.” Low-cost carriers like AirAsia have proven they can grow quickly, and Middle Eastern carriers with state backing can sustain aggressive expansion, even when private competitors would be forced to retreat.

2. Bargaining Power of Suppliers: HIGH

Airlines have two supplier problems they can’t wish away. First, aircraft: Boeing and Airbus form a duopoly, which gives them enormous leverage. Second, fuel: it’s volatile, unavoidable, and can swing profitability faster than management can react.

There’s also a strategic supplier-adjacent risk: technology that changes route economics. Long-range aircraft can bypass hubs entirely. The Boeing 777-200LR, launched in 2005, can fly roughly 17,500 km—enough to enable routes that skip traditional connecting points like Singapore on certain city pairs.

SIA mitigates supplier power with long-term fleet planning, relationships with both manufacturers, and its young-fleet philosophy, which helps with reliability and efficiency—and can strengthen its hand when negotiating future orders.

3. Bargaining Power of Buyers: HIGH

Air travel has become brutally transparent. Customers can compare prices instantly, switching costs are low, and in many markets the product is perceived as interchangeable—especially in economy cabins.

Even when the group’s profitability improved, yields still came under pressure. Passenger yields fell by 5.5% to 10.3 cents per revenue passenger-kilometer, driven in part by capacity growth outpacing the pace of market recovery, while competition from local and international rivals pushed fares down.

SIA’s defenses are real but not absolute: KrisFlyer loyalty, corporate contracts, and brand preference can reduce churn. They don’t eliminate it.

4. Threat of Substitutes: MEDIUM-HIGH

For premium business travel, COVID accelerated a shift that was already underway: video conferencing replacing some in-person trips. On shorter routes, high-speed rail has become a meaningful alternative in parts of Asia—China’s network in particular can compete head-to-head with flying on journeys of a few hours.

On SIA’s long-haul, transoceanic routes, substitutes are limited. But for regional connectivity—the lifeblood of a hub airline—rail is a growing competitive pressure where it exists.

5. Competitive Rivalry: VERY HIGH

This is the force that defines the industry. Singapore Airlines competes not only with other premium carriers like Cathay Pacific, but also with the Gulf giants—Emirates and Qatar Airways—plus a deep bench of low-cost carriers across Asia. Everyone is fighting for the same connecting traffic flows: Asia to Europe, Asia to the Americas, and beyond.

And the Gulf carriers, in particular, combine strong geographic positioning with state backing—an especially punishing mix in a business where price wars can last longer than private balance sheets can tolerate.

Hamilton’s 7 Powers Framework

1. Brand (STRONG)

SIA’s brand is not just well-regarded—it’s one of the few airline brands that reliably signals a premium experience. That reputation has been reinforced through decades of service execution and product upgrades, plus the steady drumbeat of industry accolades, including multiple Skytrax World’s Best Airline wins. In 2024, its cabin crew were also named the World’s Best Cabin Crew.

And the Singapore Girl remains a rare thing in a commoditized industry: an iconic symbol that creates real pricing power and preference, not just recognition.

2. Counter-Positioning (MODERATE)

Heracleous and Wirtz (2009) argue that Singapore Airlines sustained its advantage by executing a dual strategy—differentiation through service excellence and innovation, alongside cost leadership.

That creates counter-positioning. Full-service rivals typically carry higher costs. Low-cost carriers typically deliver a less premium product. SIA’s ability to sit in both worlds makes it hard to attack: competing on price means matching its efficiency, and competing on service means matching its discipline, training, and operational system.

3. Cornered Resource (STRONG)

Singapore’s geography is a built-in advantage: positioned on major East–West flight paths and close to large Asian markets. Changi compounds that advantage with world-class infrastructure and passenger experience. In 2025, Changi won Skytrax’s World’s Best Airport for the 13th time—a record—and is often treated as the benchmark for “smart airports.”

SIA also benefits from its ownership structure. Temasek Holdings, Singapore’s government investment and holding company, holds 56% of voting stock, giving the airline access to patient capital and strategic alignment that most competitors don’t have.

4. Network Effects (MODERATE)

SIA has been a Star Alliance member since April 2000. Alliance membership increases connectivity—customers can reach beyond SIA’s own network via codeshares and partner flights. But because other airlines can access similar benefits through their alliances, the network effect is helpful rather than exclusive.

5. Scale Economies (MODERATE)

SIA’s capabilities extend beyond flying planes. Training infrastructure, engineering, and catering support the parent airline, Scoot, and third-party customers—spreading fixed costs across higher volume and turning internal strengths into repeatable advantages.

6. Switching Costs (LOW-MODERATE)

KrisFlyer creates meaningful stickiness for frequent travelers, especially in corporate and premium segments. But airline loyalty has limits: switching costs are real, yet nowhere near as binding as in industries like enterprise software or industrial equipment.

IX. Financial Performance and Key Metrics

By the end of the 2024/2025 financial year, Singapore Airlines Group looked, on the surface, like it had snapped fully back into form. Net profit came in at $2.8 billion, helped by a 2.8% rise in revenue to $19.5 billion. As of March 31, 2025, the Group reported $8.3 billion in cash and bank balances.

Zoom in a little closer and the picture gets more mixed.

Revenue rose by $527 million from the year before to a record $19,540 million, driven by resilient demand for air travel and stronger cargo uplift in FY2024/25. SIA and Scoot also carried a record 39.4 million passengers, up 8.1%.

But operationally, profitability moved in the other direction. Operating profit fell 37.3%. And the big jump in net profit for FY2024/25 was significantly boosted by a one-time, non-cash accounting benefit tied to the Air India–Vistara merger. In other words: the headline profit number matters, but it’s not the cleanest read on the underlying operating trend.

That underlying trend showed up in the two core airline levers: loads and yields. Passenger load factor slipped 1.4 percentage points to 86.6%, as traffic growth of 6.4% didn’t keep up with capacity expansion of 8.2%. Passenger yields also softened, down 5.5% to 10.3 cents per revenue passenger-kilometre.

Key KPIs to Monitor

For anyone trying to understand whether SIA is strengthening or merely holding steady, two metrics do most of the work:

1. Passenger Yield (Revenue per Revenue Passenger-Kilometer)

Yield is the simplest proxy for pricing power. When it rises, SIA is getting paid for its premium positioning. When it falls, it usually means some combination of tougher competition, too much capacity in the market, or discounting to fill seats.

As Goh put it: “If you compare this year's half year result relative to the previous year, indeed our yield has come down by about 7%. But if you compare the yield of the same half year result that we announced to that of the year pre-pandemic, it is still about 12% higher than pre-pandemic.” That framing matters. In a volatile post-COVID environment, the pre-pandemic baseline can be more informative than a single year-over-year comparison.

2. Passenger Load Factor

Load factor tells you how efficiently capacity is being used: what percentage of available seats are actually sold. An 86.6% load factor is still healthy, but the direction matters. When load factor drops at the same time capacity is growing, it can be an early warning sign that supply is outrunning demand.

Fleet Investment

What’s striking is how SIA responded to this yield pressure: not by pulling back on the product, but by doubling down on it.

In November 2024, SIA announced a $1.1 billion investment to install all-new long-haul cabins across its Airbus A350-900 long-haul and ultra-long-range fleet. The plan included a new First Class cabin on seven A350-900ULRs, aimed at raising the bar on the airline’s longest routes. Then in April 2025, SIA announced a $45 million overhaul of its SilverKris and KrisFlyer Gold lounges at Changi Airport Terminal 2.

It’s a familiar SIA move: keep investing in differentiation even when the market gets noisy. The bet is that, over time, product excellence is not a cost indulgence—it’s the mechanism that protects pricing power.

X. Bull Case and Bear Case

The Bull Case

Singapore Airlines has a handful of advantages that, unlike a fare sale or a lucky fuel hedge, can actually compound over time.

Geographic Moat: Singapore’s location still does something no marketing budget can replicate. It sits naturally on major East–West flows, and as Asian economies grow and travel within the region expands, Changi’s value as a connector tends to rise. The International Air Transport Association expects Asia-Pacific to be one of the fastest-growing regions for passenger traffic over the next two decades—exactly the macro tailwind a hub airline needs.

India Exposure: The 25.1% stake in Air India is SIA’s most direct answer to its oldest problem: no domestic market. Instead of trying to invent one at home, it has bought a meaningful seat at the table in India—one of the fastest-growing aviation markets in the world—while keeping some distance from day-to-day operating risk.

Brand Premium: Even in a world of constant comparison shopping and post-COVID yield pressure, SIA still sells a product that a meaningful segment of travelers will pay extra for. And the young-fleet philosophy reinforces that premium in a very SIA way: newer aircraft can lower costs and improve reliability, while also making the experience feel modern and worth paying for.

Patient Capital: Temasek’s majority ownership gives SIA something most airlines don’t have: permission to think in cycles, not quarters. When the industry turns down, management can keep investing in fleet and product instead of making the kind of short-term cuts that look good in the next earnings call and haunt you for the next decade.

The Bear Case

The flip side is that airlines don’t get to choose their risk profile. Even the best-run carrier is still flying through a storm system of competition, costs, and geopolitics.

Yield Compression: The numbers are already flashing the warning. Capacity has been growing faster than traffic—capacity up 8.2%, traffic up 6.4%—which is how pricing power erodes. Costs are also climbing: group expenditure rose 9.5% to US$17.83 billion in FY2024/25, with non-fuel costs up 11% on a mix of inflation and higher activity. If supply keeps outrunning demand, margins don’t just soften; they get squeezed.

Hub Bypass Risk: The more range aircraft manufacturers give everyone, the more fragile the hub model becomes. Ultra-long-range aircraft like the Boeing 777-200LR make it possible, on certain city pairs, to skip hubs like Singapore entirely. Every new long-range delivery to a competitor is a reminder that some connecting traffic can simply disappear rather than be competed for.

Gulf Carrier Competition: Emirates, Qatar Airways, and Etihad aren’t just strong brands with good hubs—they also operate with implicit or explicit state backing. That can enable market-share strategies and prolonged fare aggression that would be difficult for a strictly profit-maximizing airline to sustain. For SIA, it’s an asymmetric competitor set on some of the most important long-haul flows.

India Execution Risk: The Air India stake is strategically elegant on paper, but airline integrations are notoriously hard in practice. The Vihaan.AI transformation programme is ambitious, and ambition cuts both ways: if execution stumbles, the upside takes longer to arrive—or arrives in a diminished form.

Fleet Delivery Delays: Fleet planning is only an advantage if the planes actually show up. Delivery of Boeing 777-9s—needed to replace SIA’s ageing Boeing 777-300ERs—has slipped to 2026 at the earliest, and 2027 may be more realistic if certification delays continue. The longer that gap stretches, the more SIA risks higher maintenance costs on older jets and tighter constraints on growth capacity.

XI. Conclusion: The Next Fifty Years

Fifty-three years ago, a tiny nation with no natural resources, no domestic market, and no obvious aviation advantage decided to bet its international reputation on an airline. It wasn’t a prestige project. It was a survival strategy. And it worked—far beyond what anyone could reasonably have expected.

Singapore Airlines didn’t win by finding one clever trick. It won by building a machine. It took what strategy textbooks say you can’t do—run a differentiated, premium product and stay relentlessly cost-conscious—and made it a repeatable system. When the pandemic shut global aviation down, it survived with unprecedented financing and an almost stubborn focus on staying operationally ready. And when its oldest constraint resurfaced—Singapore’s lack of a home market—it didn’t complain about geography. It partnered into a larger engine of demand, buying a meaningful stake in India’s aviation future.

Through that turbulent stretch, Goh Choon Phong led the company through recovery, pushed service and product upgrades, and expanded routes as travel returned. In the 2023–2024 fiscal year, the airline reported a record annual profit of S$2.67 billion.

Along the way, Goh’s leadership drew wide recognition: the 2015 Centre for Aviation’s Asia-Pacific Airline CEO of the Year award, the 2016 Eisenhower Global Innovation Award, the 2017 Outstanding Chief Executive Officer in the Business Times Singapore Business Awards, the 2019 Singapore Corporate Award’s Best Chief Executive Officer (for companies with S$1 billion or more in market capitalization), Tatler’s Asia Most Influential in 2022 and 2023, and, most recently, the 2024 Excellence in Leadership Award at Air Transport World magazine’s annual Airline Industry Achievement Awards.

None of that changes the core truth of airlines: the future is never calm for long. The challenge list is already clear. Yield pressure as capacity returns. Gulf carrier competition with asymmetric state backing. A climate transition that forces expensive fleet renewal. Integration complexity at Air India. Supply chain constraints that can delay aircraft deliveries and distort even the best-laid plans.

But if there’s a throughline in SIA’s story, it’s this: the airline has been here before, in different forms. Landing-rights battles in the 1970s. The low-cost carrier onslaught in the 2010s. The near-total shutdown of 2020. Each time, it responded the same way—not with panic, but with discipline, reinvention, and a willingness to make hard moves early.

For investors, that’s the appeal. You get exposure to long-term Asian aviation growth through a company with real competitive advantages, patient-capital backing, and a decades-long track record of operational excellence. The risks are real—this is the airline industry—but the positioning is unusually strong.

And Lee Kuan Yew’s 1972 mandate still hangs over Airline House: make profits, or close down. More than five decades later, Singapore Airlines is still delivering on that directive—and it looks built to keep doing it for the next fifty years, too.

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music