CapitaLand Integrated Commercial Trust: Singapore's Crown Jewel of Commercial Real Estate

I. Introduction: A Pioneer's Journey

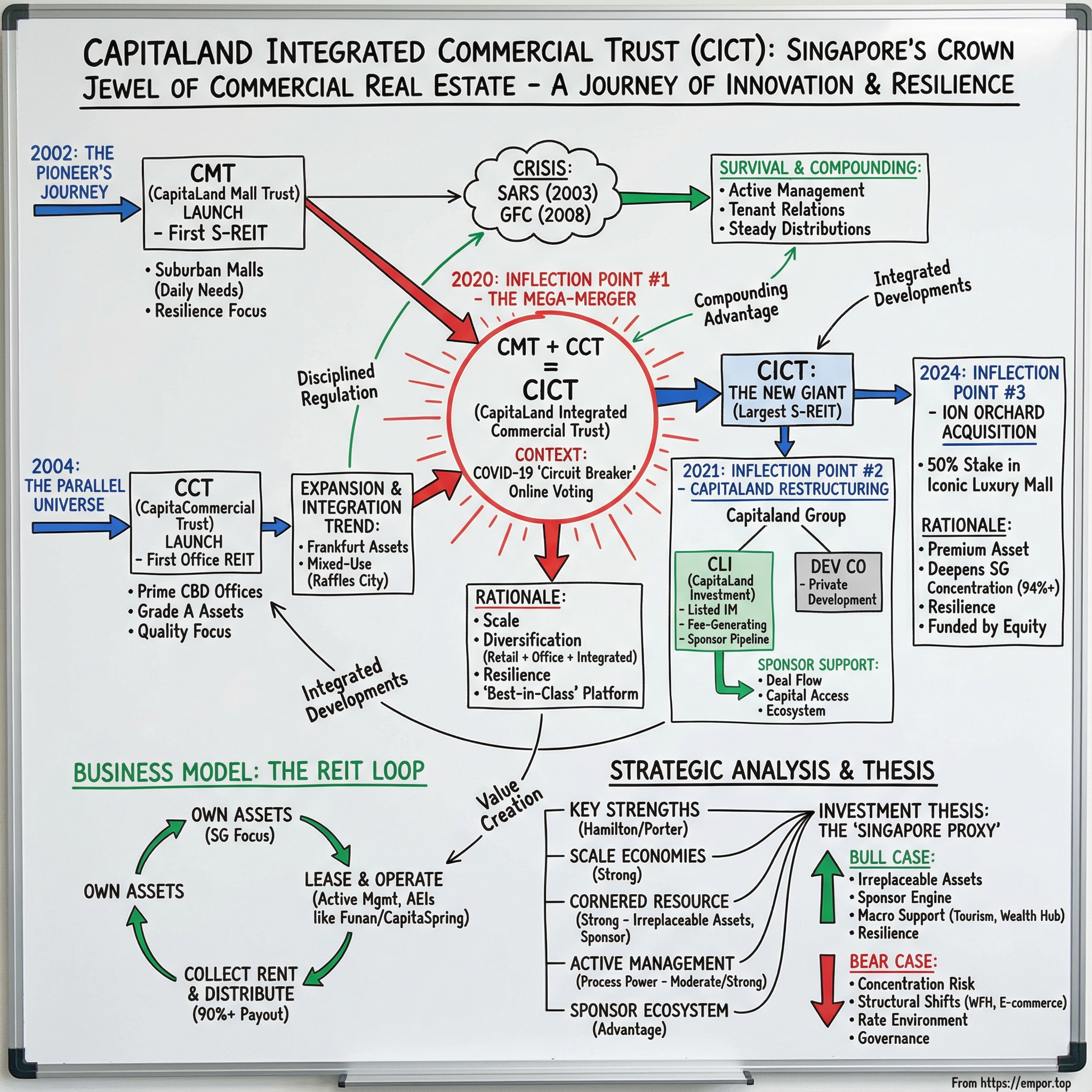

In the summer of 2002, something quietly historic happened in Singapore. Not on Orchard Road itself, amid the crowds and storefronts, but a few steps removed—on the screens of the Singapore Exchange. On July 17, a financial product most local investors had never owned before began trading: Singapore’s first real estate investment trust. CapitaLand Mall Trust hit the market, carrying a portfolio of shopping centres—and, more importantly, a new idea for how the country could turn bricks-and-mortar into a liquid, investor-friendly asset class.

Two decades later, that early experiment has grown into something far bigger. CapitaLand Integrated Commercial Trust, or CICT, is now the first and largest REIT listed on Singapore Exchange Securities Trading Limited, with a market capitalisation of S$15.9 billion as at 30 June 2025.

But the scale isn’t the point. The story is. Because the path from “mall trust” to one of the Asia-Pacific region’s most significant commercial real estate platforms is a case study in Singapore’s brand of financial innovation: disciplined regulation, sponsor-backed access to prime assets, and constant reinvention through crisis.

As at 31 December 2024, CICT owned 26 properties: 21 in Singapore, two in Frankfurt, and three in Sydney. Together, they were valued at S$26.0 billion. The mix spans offices concentrated in and around the CBD, major retail malls across downtown and the suburbs, and integrated developments that blend multiple uses into one address.

And then there’s the machine behind the assets. CICT is externally managed by CapitaLand Integrated Commercial Trust Management, with CapitaLand retaining a 24% stake in the REIT—an arrangement that brings both a powerful pipeline and the kind of sponsor relationship that can shape everything from strategy to timing.

If you want to understand CICT, you’re really trying to understand Singapore: how a small, land-scarce city-state repeatedly turned constraints into advantage—by engineering markets, attracting capital, and obsessing over the quality of location.

II. Singapore's REIT Revolution: Setting the Stage

To appreciate what CapitaLand built, you have to rewind to what investing in real estate looked like in Singapore before 2002. If you wanted exposure, you basically had three choices. You could buy a physical property—capital intensive, illiquid, and a headache to manage. You could buy shares in property developers—often a bet on the next project cycle, with all the volatility that comes with it. Or you could try your luck overseas. None of those options offered a simple way to own stabilized, income-producing buildings the way public-market investors in the US had been doing for decades.

Singapore decided to change that.

The regulatory groundwork for S-REITs was put in place in 1999. CapitaLand Mall Trust became the first to list in 2002. That three-year gap wasn’t dead air; it was the “figure out how to do this properly” phase—where regulators, sponsors, and advisors hammered out a structure robust enough to attract global capital and simple enough for local investors to understand. KPMG’s REIT track record in Singapore traces back to that moment: they were involved in pioneering the first REIT listing in the market.

What emerged was a framework with a few key features that made S-REITs instantly legible—and investable. The headline rule was the payout requirement: S-REITs had to distribute at least 90% of their taxable income each year to qualify for tax transparency. In plain English, that meant the REIT itself generally wasn’t taxed on that income; instead, taxes were borne at the investor level.

That single design choice did a lot of heavy lifting. It helped turn REITs into a clean income product. And it mattered even more in a region where demographics were shifting and demand for steady, yield-like investments was rising.

Zoom out, and Singapore’s ambition becomes obvious: this wasn’t just about creating a new local investment wrapper. Singapore positioned itself as Asia’s REIT hub by leaning into what it could offer that other financial centres struggled to replicate in combination—stable governance, strong rule of law, English as a working language, credible regulatory oversight, and a strategic location in the flow of Asian commerce. If you were a global investor looking for a place to own Asian real estate through public markets, Singapore was making a strong case to be your default.

But the most distinctive ingredient in Singapore’s REIT system wasn’t a regulation. It was a relationship: the sponsor model—often powered by government-linked companies.

In 2000, Pidemco Land and DBS Land merged to form CapitaLand Group Pte. Ltd. That merger didn’t just create a bigger property company. It created a sponsor with the balance sheet, development engine, and asset base to seed multiple listed vehicles over time. CapitaLand is a typical government-linked company, with about 40% of its shares held by Temasek. In practice, that meant CapitaLand had both the incentive and the capability to support sponsored REITs with quality assets and financial backing.

This sponsor structure became a kind of compounding advantage for Singapore’s REIT ecosystem. Where REITs elsewhere might fight to source great buildings, sponsored S-REITs could rely on a built-in pipeline: the sponsor develops or acquires assets, stabilizes them, and then sells them into the REIT at the right point in the asset’s life. Research has also found government-linked REITs tend to show higher firm value and profitability than non-government-linked peers—for example, with Tobin’s Q reported as meaningfully higher.

By August 2024, Singapore had grown into the largest REIT market in Asia excluding Japan, with around 40 traded S-REITs and property trusts valued at roughly S$100 billion. S-REITs had become a core part of the local market—accounting for more than 12% of SGX’s total market capitalisation.

So when CapitaLand Mall Trust rang the bell in 2002, it wasn’t just launching a new vehicle. It was kicking off a playbook—one that would scale from “a portfolio of malls” into a national asset class, and eventually into the diversified giant that CICT would become.

III. The Pioneer Years: CapitaLand Mall Trust (2002–2010)

CapitaLand Mall Trust’s early years read like a startup origin story—except the “product” wasn’t an app, it was a brand-new way for everyday investors to own income-producing real estate.

When CMT launched in July 2002, it didn’t come out swinging with glitzy, tourist-heavy malls. It started with something far more practical: suburban shopping centres. The kinds of places built around daily routines—groceries, quick meals, errands, and after-school classes. Not glamorous, but resilient. And for a first-of-its-kind REIT trying to earn trust, resilient was the whole point.

That resilience got tested almost immediately.

In 2003, SARS hit. Singapore was declared free of the virus by the World Health Organization on 30 May 2003, after recording 238 cases and 33 deaths. Globally, SARS infected 8,096 people and killed 774. The numbers were scary—but the behavior shift was the real shock to the system. People stayed home. They avoided crowds. Travel plans evaporated. For a retail REIT that depended on foot traffic, it wasn’t just “a downturn.” It was a gut check.

CMT’s response shaped its DNA. The malls stayed open. Management focused on communication, tenant relationships, and operational flexibility. Support was extended to tenants under pressure. And when the outbreak came under control, the recovery snapped back stronger than many economists expected—especially for a city that had just watched tourism and retail take a direct hit.

With the crisis behind it, CMT went back to the playbook—and started executing with discipline. Acquire well-located assets. Improve them through active management. Build credibility through steady distributions. Over time, it added major names to the portfolio: Clarke Quay, the riverside lifestyle and entertainment hub; then later Bugis+ and Westgate. Each deal wasn’t just “more space.” It was broader reach across Singapore and a deeper grip on the country’s retail map.

Then came 2008, and the Global Financial Crisis—a very different kind of panic. Credit tightened, confidence collapsed, and property markets everywhere looked suddenly fragile. CMT leaned on the lessons it had already earned the hard way: protect relationships with tenants, stay disciplined on costs, and ride out the volatility rather than react to it.

By the end of this pioneer era, CMT had proven the most important thing a REIT can prove: it could take hits, keep operating, and keep compounding. It wasn’t simply holding malls. It was running a platform—one that could actively enhance assets, manage through crisis, and build the foundation for a much bigger future.

IV. The Parallel Universe: CapitaLand Commercial Trust

While CMT was quietly proving that suburban malls could be a durable cash machine, CapitaLand was also building a second vehicle—one aimed at a completely different heartbeat of the city: the Central Business District.

On 11 May 2004, CapitaCommercial Trust (CCT) began trading on the Singapore Exchange as Singapore’s first commercial REIT. It was a clean, deliberate expansion of the REIT experiment—from everyday shopping to the towers where Singapore’s finance and multinational economy actually ran. By the end of its first day, about 3.17 million units had changed hands.

From the start, CCT was designed to own prime office real estate in the CBD. It launched with a portfolio of seven commercial properties, each located adjacent or close to MRT stations. As at 31 December 2003, that starting portfolio was valued at about S$2.018 billion.

Keeping CCT separate from CMT made a lot of sense in that era. Retail and office behave differently. Office leases tend to be longer, which can mean steadier, more predictable income—but also slower resets when rents rise. Retail leases are typically shorter, which gives a landlord more frequent chances to reprice space, but also exposes the portfolio more quickly when conditions soften. Even the investor pitch was different: some wanted the visibility of office cash flows; others wanted the churn and upside of retail.

Over time, CCT built its portfolio the way Singapore tends to build things: methodically, and with a bias toward quality. It focused on premium Grade A buildings in the financial district—names that felt less like properties and more like pieces of the skyline: Capital Tower, Six Battery Road, Asia Square Tower 2. These were the kinds of addresses multinationals chose when they wanted to plant a flag in Asia.

But by the late 2010s, the tidy logic of “one trust per asset class” was starting to look dated. Cities were moving toward integrated developments—places that blend office, retail, and other uses into one dense destination. Raffles City Singapore, which both trusts owned stakes in, was a preview of that future.

CCT also began pushing beyond Singapore, acquiring office properties in Frankfurt, Germany. It added another geography, another currency, and another layer of complexity—while also offering a partial release valve from pure Singapore concentration.

Without anyone saying it out loud yet, the question was forming: if these two trusts shared a sponsor, shared a manager, and increasingly shared a view of what modern “commercial” real estate looked like… how long would they really stay separate?

V. INFLECTION POINT #1: The Mega-Merger (2020)

22 January 2020. On the surface, it was just another day in a long bull market. COVID-19 was still a distant headline out of Wuhan, not yet the event that would reorder daily life and global finance. But in Singapore real estate, that date became a before-and-after moment.

That morning, CapitaLand Mall Trust and CapitaLand Commercial Trust announced they would merge to form a new vehicle: CapitaLand Integrated Commercial Trust. The combined platform would be positioned as the largest REIT in Singapore and one of the largest in Asia Pacific, with an asset base of about S$22.4 billion.

The pitch was straightforward: CMT and CCT were, in their words, “best-in-class” in retail and office, and they weren’t combining out of weakness. They were combining because the single-asset-class model was running out of runway. A bigger, more diversified trust—retail, office, and integrated developments under one roof—could pursue a “higher and more sustainable growth trajectory” than either could alone.

The mechanics were clean. CCT unitholders would receive 0.720 new CMT units plus S$0.2590 in cash for every CCT unit they held. Structurally, CMT would acquire CCT via a trust scheme of arrangement—giving CCT unitholders clarity on the offer, while letting CMT consolidate the portfolio in one move.

On paper, the result was a heavyweight: a new CICT with 24 properties valued at S$22.9 billion, about 10.4 million square feet of net lettable area, and occupancy around 99%. It was meant to be balanced by design—retail cash flows, office stability, and integrated assets that reflected how Singapore’s prime real estate was increasingly being built.

Then the world changed.

Within weeks, COVID-19 was everywhere. Singapore entered its “circuit breaker.” Malls shuttered. Footfall collapsed. Offices emptied. The very assets these two REITs owned—shopping centres and CBD towers—suddenly looked like the epicenter of a once-in-a-century economic shock.

Even the merger process itself had to adapt. Because of the COVID-19 situation, unitholders couldn’t attend the EGMs or the Trust Scheme Meeting in person. Participation shifted online: live audio-visual webcast or live audio-only stream. The deal that was supposed to create the future of Singapore commercial real estate would be decided through laptop speakers and shaky internet connections.

In that context, the merger vote stopped being a routine corporate exercise. It became something closer to a referendum: do you believe in the long-term future of retail and office real estate after a pandemic?

Unitholders, overwhelmingly, said yes. At CCT’s Trust Scheme Meeting, the resolution passed with approximately 90.31% approval by headcount, representing about 98.23% in value of the CCT units voted.

On 21 October 2020, the merger became effective. CMT—first listed back in July 2002—would soon trade under its new name, CapitaLand Integrated Commercial Trust, from November 2020.

The timing looked almost absurd: merging a mall REIT and an office REIT in the depths of a crisis that had emptied both. To skeptics, it was reckless optimism. To believers, it was contrarian discipline. In hindsight, the market would come to see it as the latter.

VI. INFLECTION POINT #2: The CapitaLand Restructuring (2021)

The CICT merger had barely settled when the ground shifted again—this time above it, at the sponsor level.

On 22 March 2021, CapitaLand Group announced a proposed restructuring of its business. Then, on 20 September 2021, CapitaLand Investment Limited, or CLI, debuted on the Singapore Stock Exchange under the trading name CapitaLandInvest and stock code 9CI.

This wasn’t a branding exercise. It was a rewrite of CapitaLand’s identity.

For decades, CapitaLand had largely looked like a classic property company: acquire land, develop buildings, then either sell them or hold them for rent. The restructuring split that model in two. CapitaLand’s investment management platforms, along with its lodging business, were consolidated into CLI, which was listed by introduction on the Singapore Exchange. Meanwhile, CapitaLand’s real estate development business moved into private ownership.

The strategic point was clear: lean into the capital-efficient side of the house—the fee-generating investment management business—rather than the capital-intensive, cycle-exposed development engine.

For CICT, this mattered immediately. CICT is managed by CapitaLand Integrated Commercial Trust Management Limited, a wholly owned subsidiary of CLI, a leading global real asset manager with a strong Asia foothold.

And that changed what “sponsor support” really meant. The sponsor wasn’t just a developer with assets to sell into the REIT. It was now a fund manager whose job was to grow assets under management—by working with global institutional capital, building products, and scaling platforms. Upon listing on SGX-ST, CLI was expected to become a leading listed real estate investment manager globally, with pro forma total real estate assets under management of approximately S$115 billion as at 31 December 2020. It also had approximately S$78 billion of real estate funds under management held via its managed Listed Funds and Unlisted Funds.

In practical terms, the benefits for CICT were straightforward. CLI remained committed to the long-term growth of its listed funds by providing a pipeline of attractive assets with stable yields. This proposed divestment was positioned as a testament to CLI’s strong sponsor support for CICT.

Zoom out, and the restructuring reframed CICT’s role. It wasn’t just a large Singapore REIT anymore. It was a flagship inside a broader ecosystem—listed and unlisted funds, across multiple property types and geographies—where the sponsor’s incentives were designed to keep feeding scale, capital access, and assets into the platform.

VII. INFLECTION POINT #3: The ION Orchard Acquisition (2024)

By September 2024, CICT had already become a category-defining REIT in Singapore. Then it went after the address that, for many people, defines Singapore retail.

On 3 September 2024, CapitaLand Integrated Commercial Trust entered into an agreement with its sponsor, CapitaLand Investment Limited, to acquire a 50.0% interest in ION Orchard at an agreed property value of S$1,848.5 million, negotiated on a willing-buyer and willing-seller basis. The logic was simple: bring an iconic, premium destination mall into the portfolio and strengthen the resilience of CICT’s high-quality, diversified platform.

ION Orchard isn’t just “a mall on Orchard Road.” It’s the landmark. A defining piece of the boulevard’s modern identity, with an architectural façade that’s instantly recognizable and a location that’s built for volume—locals, tourists, and everyone in between. In a city that prizes accessibility, ION sits right where the foot traffic naturally concentrates.

Strategically, it fit CICT’s center of gravity. CICT is predominantly Singapore-focused, and this proposed divestment would further enhance the overall quality of its portfolio. And while the announcement was big news, it also felt inevitable. ION Orchard had long been viewed as one of the crown jewels of CapitaLand’s portfolio, and market watchers had expected it would eventually make its way into the REIT.

What made it truly notable was the timing. Singapore REITs hadn’t been doing many large acquisitions. With interest rates elevated, buying big assets and making the numbers work for unitholders had become harder. CICT’s ability to pursue a nearly S$2 billion transaction in that environment was a reminder of what scale and credibility can unlock.

The asset itself is substantial: an eight-storey mall with net lettable area of around 623,600 square feet, anchored by a luxury-heavy tenant mix—names like Louis Vuitton, Dior, and Cartier—exactly the kind of lineup that commands premium rents and pulls in high-spending shoppers.

ION Orchard was, and remains, held through a joint venture structure. CICT acquired 50.0%, while Sun Hung Kai Properties holds the remaining 50.0%—a partnership with a leading developer and operator in Greater China known for premium large scale integrated developments.

To fund the acquisition, CICT’s manager planned to raise $1.1 billion entirely through equity, via a combination of a placement and a preferential offer to unitholders. The private placement comprised 171,737,000 new units at an issue price of between $2.038 and $2.091 per unit, to raise $350.0 million. The preferential offer comprised 377.3 million new units at an issue price of $2.007 per unit.

Unitholders approved the deal at an extraordinary general meeting on 29 October, and the acquisition is now complete—bringing ION Orchard formally into CICT’s portfolio.

Beyond the headline, the acquisition subtly improved portfolio composition. It added quality and diversification to CICT’s retail tenant profile, reducing the top 10 tenants’ contribution to the overall portfolio’s Gross Rental Income to 18.0%, from 19.2%.

And it doubled down on the Singapore thesis. After the purchase, Singapore’s contribution to CICT’s AUM increased to 94.2%, up from 93.7% pre-acquisition.

VIII. The Business Model: How CICT Works

To understand CICT, you don’t need an MBA. You just need the core REIT loop: own income-producing buildings, lease them out, collect rent, and pass most of that rent back to unitholders.

CICT’s version of that loop is heavily Singapore-weighted by design. Most of its properties sit in Singapore, with Australia and Germany together making up less than 10% of the portfolio. That concentration isn’t an accident—it’s the product. CICT has effectively positioned itself as a proxy for Singapore commercial real estate. Buying units isn’t just a view on “property”; it’s a view on Singapore continuing to do what it has spent decades optimizing for: being a tourism magnet, a wealth management hub, and a preferred regional headquarters for multinationals.

The distribution engine is also baked into regulation. To qualify for tax transparency, Singapore REITs must distribute at least 90% of taxable income—and in practice, most pay out close to everything they can. For FY 2024, CICT delivered a distribution per unit of 10.88 cents, up 1.2% year-on-year. Based on the closing price of S$1.93 per unit on 31 December 2024, that worked out to a FY 2024 distribution yield of 5.6%.

Under the hood, FY 2024 showed steady operational momentum: gross revenue rose 1.7% and net property income increased 3.4%. Portfolio committed occupancy stayed high at 96.7%, and the underlying leasing story was healthy too—Singapore retail and office portfolios achieved positive rent reversions of 8.8% and 11.1%, respectively.

But the most important thing to remember is this: the best REITs don’t act like passive landlords. They behave like operators. A meaningful share of value creation comes from asset enhancement initiatives—renovations, upgrades, and repositionings that make a building more relevant, more productive, and ultimately more rentable.

CapitaSpring is a perfect example of what “integrated” looks like in modern Singapore. Completed in November 2021, the 280-metre-tall development is an award-winning tower that stacks premium Grade A offices, ancillary retail, and a serviced residence into a single, vertically connected address in the heart of Raffles Place.

And then there’s Funan—CICT’s more visible proof that reinvention can be an investment strategy. Unveiled and revitalised in June 2019, Funan reopened as an integrated development with a retail hub, two office blocks, and lyf Funan Singapore, an apartment hotel concept designed for the millennial generation. After redevelopment, Funan’s property value more than doubled to S$751 million.

Finally, there’s the sponsor relationship—the quiet superpower, and the perpetual governance challenge, of the S-REIT model.

On the upside, CLI can provide deal flow: potential acquisitions seeded from its development activities or sourced from the market. CLI has positioned itself as committed to the long-term growth of its listed funds by providing a pipeline of attractive assets with stable yields, framing divestments into the REIT as part of that sponsor support.

On the other hand, buying from your sponsor is inherently sensitive. Related-party transactions need to be tightly governed—valuations must be independent, approvals must come from non-conflicted directors, and large transactions often go to unitholders. The ION Orchard acquisition was a textbook example: it required an extraordinary general meeting, and the sponsor abstained from voting.

For investors, that’s the trade: CICT offers liquid exposure to prime Singapore commercial real estate without the capital outlay and illiquidity of owning buildings directly—backed by a portfolio that, as at 31 December 2024, remained highly occupied. Overall committed occupancy was 96.7%, with retail at 99.3%, office at 94.8%, and integrated developments at 98.9%.

IX. Porter's Five Forces Analysis

If you strip away the tickers and the quarterly slides, CICT is still playing a very old game: owning the right buildings, in the right places, and keeping them full at the right rents. Porter’s Five Forces is a useful way to pressure-test how hard that game is—and where CICT has structural advantages.

Threat of New Entrants: LOW

In Singapore, the most important barrier to entry is also the simplest: there isn’t much Singapore to go around.

With limited land and tightly managed urban planning, new commercial supply doesn’t appear quickly—and it certainly doesn’t appear cheaply. A would-be entrant has two options, neither of them easy: buy existing assets at market-clearing prices, or bid for government land tenders against incumbents with deep pockets and long track records.

On Orchard Road specifically, the near-term story is even clearer. There isn’t meaningful new retail supply coming online any time soon. For landlords who already own prime space, that’s the best kind of competition: none. It supports occupancy and gives rents room to move.

And on top of the physical constraint, there’s a structural one. Running a REIT at scale in Singapore isn’t a casual undertaking. The bar for credible sponsorship, management expertise, and institutional-grade assets is high—another layer of friction that keeps “new entrants” from showing up overnight.

Bargaining Power of Suppliers (Property Developers/Sellers): MODERATE

On sourcing assets, CICT starts with an advantage that most landlords can’t manufacture: the sponsor pipeline.

When CLI develops or acquires a property that fits long-term, income-producing ownership, CICT is naturally at the front of the line—often supported by rights like a right of first refusal, or at minimum the sponsor’s strong preference to seed assets into its listed platform.

But that advantage fades the moment CICT steps into the open market. For third-party deals, it’s competing with other well-capitalised S-REITs and private capital. And in a land-scarce market like Singapore, sellers know what they have. That scarcity gives suppliers leverage, which keeps this force in the “moderate” zone rather than “low.”

Bargaining Power of Buyers (Tenants): MODERATE

CICT’s tenant base is deliberately diversified, and the ION Orchard acquisition nudged that further: the top 10 tenants’ contribution to overall gross rental income fell to 18.0% from 19.2%. That’s not a rounding error—it’s risk management. The goal is simple: no single tenant should have enough weight to dictate terms.

At the same time, tenants do have options, which is why their bargaining power isn’t “low.” But in the segments CICT plays in, options are limited in the ways that matter. Prime CBD office space is a small club. Orchard Road luxury frontage is an even smaller one. If a tenant wants the right address, the list of genuine substitutes gets short fast.

Could new nearby retail supply pressure rents and occupancy? Yes, in theory. In practice, Singapore’s planning controls make that a slower-moving risk than in many other global cities.

Threat of Substitutes: MODERATE-HIGH

This is the most persistent long-term challenge—and it isn’t coming from the REIT next door.

For offices, the substitute is behavioural: work-from-home and hybrid work reduce the baseline demand for space. That concern spiked during COVID-19 and, while it has softened in many places, it hasn’t disappeared.

For retail, the substitute is digital. E-commerce continues to siphon off categories where convenience wins. Singapore’s dense, mall-centric culture has held up better than many Western markets, but the direction of travel is still real.

CICT’s best defence here is portfolio design. Integrated developments—where office and retail reinforce each other, and the property functions as a true destination—are harder to displace. You can buy something online, but you can’t replicate a prime, mixed-use node of city life in a shopping cart.

Competitive Rivalry: MODERATE

Singapore is one of the most competitive REIT markets in Asia. By August 2024, it had about 40 traded S-REITs and property trusts with a combined market value of roughly S$100 billion. There’s no shortage of capable operators.

But rivalry is tempered by two things. First, CICT’s scale matters: it can access capital more efficiently, negotiate from a position of strength, and execute large asset enhancement projects that smaller peers struggle to fund. Second, the very best properties—prime CBD towers, dominant malls, trophy integrated developments—don’t trade often. If you own them, you’re not just competing on price. You’re competing on who already controls the corner.

Competitors like Frasers and Mapletree are formidable, and sponsor-backed platforms create real, ongoing competition for assets. Still, the market is large enough to support multiple winners—and CICT’s concentration in irreplaceable locations is what keeps rivalry from becoming a race to the bottom.

X. Hamilton's Seven Powers Analysis

If Porter tells you how competitive the arena is, Hamilton Helmer’s “7 Powers” tells you who has the right to keep winning in it. For CICT, the answer comes down to a handful of durable advantages—some obvious, some subtle—that make it harder to dislodge than a typical landlord.

1. Scale Economies: STRONG

CICT is the first and largest REIT listed on SGX-ST, with a market capitalisation of US$10.3 billion, or S$14.1 billion, as at 31 December 2024.

In REIT land, size isn’t vanity—it’s an operating advantage. Bigger platforms typically borrow more cheaply because lenders and bond investors view them as more stable, and competition for their business is higher. Scale also lowers the cost of running the machine. A team that can operate a couple dozen major properties spreads expertise and overhead across a much wider base than a smaller peer can.

There’s also a market-structure edge: index inclusion. Being large enough to sit in major indices helps keep trading liquidity healthy and can create a steady baseline of demand from passive funds.

2. Network Effects: WEAK

REITs don’t really get classic network effects. One tenant in one building doesn’t inherently make every other building more valuable.

But in retail, there’s a close cousin: tenant mix. A mall becomes more attractive when the right anchors and brands pull in shoppers, which then lifts sales for everyone else. CICT’s flagship assets can benefit from this “spillover” effect—strong tenants attract footfall, footfall attracts more strong tenants, and the cycle reinforces itself at the property level.

3. Counter-Positioning: MODERATE

The CMT–CCT merger created something many competitors didn’t have: a diversified commercial REIT built to own integrated developments, not just pure retail or pure office.

That matters because the direction of prime Singapore real estate has been “work-live-play” for years. As the merger rationale put it: “Our complementary skill sets will strengthen the ability of the merged entity to capitalise on future growth opportunities as commercial development trends towards mixed-use integrating work-live-play offerings.” Even at the time of the deal, about 29% of the combined portfolio value already had integrated retail and office components.

In other words, CICT didn’t just get bigger—it got structurally better aligned with where the market was heading.

4. Switching Costs: MODERATE

Tenants don’t move on a whim, especially in premium space.

Office occupiers face real friction: long leases, disruption risk, and high fit-out costs, particularly where specialized interiors and infrastructure are involved. Retailers face a different kind of cost—losing a proven location and having to rebuild customer habits elsewhere. And in the places that matter most—prime CBD and Orchard Road—credible alternatives are limited, which further strengthens tenant stickiness.

5. Branding: MODERATE

CapitaLand is one of the most recognizable names in Singapore real estate, and that reputation carries into leasing, partnerships, and investor confidence. On top of the corporate brand, individual properties like ION Orchard and Raffles City Singapore are consumer brands in their own right.

As CapitaLand itself has said, “The remarkable success of ION Orchard is a testimony to collaborative efforts in developing and managing this pre-eminent destination mall.” In a category where “location” is the headline, brand is the supporting force that helps keep that location full.

6. Cornered Resource: STRONG

This may be CICT’s most enduring power: it owns things you can’t reproduce.

ION Orchard is the cleanest example. It’s sited in a prime location with excellent accessibility, and its architectural façade and presence make it instantly recognizable. More importantly, it sits on land that simply cannot be recreated. Trophy sites in Orchard Road, Raffles Place, and the Singapore CBD aren’t just scarce—they’re effectively finite.

The sponsor relationship also functions like a cornered resource. CapitaLand is one of Asia’s largest listed real estate companies, and that scale supports a pipeline of assets and financial capacity that smaller, private sponsors struggle to match. As a government-linked company, it also has deeper pockets and longer time horizons than many purely commercial players.

7. Process Power: MODERATE

CICT has shown it can do more than collect rent—it can manufacture better rent.

Asset enhancement and repositioning require accumulated know-how: how to redesign space, re-tenant intelligently, manage disruption, and come out the other side with a stronger asset. Funan is the poster child. Upon completion in June 2019, its property value more than doubled to S$751 million.

That kind of outcome isn’t luck. It’s process—repeatable, hard-earned capability that’s difficult for competitors to copy quickly.

XI. The Singapore Thesis: Why Geography Matters

Owning CICT is, in the simplest sense, owning a view on Singapore.

The ION Orchard deal made that explicit. By buying 50% of the mall, CICT pushed Singapore’s share of its assets under management to 94.2%, up from 93.7% before the acquisition. That level of concentration isn’t accidental. It’s the strategy. CICT is built to be a proxy for the city-state’s commercial heartbeat—its offices, its shopping streets, and the integrated developments where those worlds collide.

But that also means the investment demands conviction in the Singapore story continuing to work.

Singapore’s bull case is familiar, but it’s also real. Political stability in a region that doesn’t always offer it. Rule of law that global companies can price into long-term decisions. Infrastructure that makes the city not just livable, but frictionless. And a geographic position that has kept it relevant to Asian trade flows for centuries.

For CICT, that macro story shows up most visibly in tourism—and tourism shows up most directly in retail rents.

In 2023, roughly 13.6 million visitors came to Singapore, and about 4.5 million of them passed through the Orchard Road belt. Tourism receipts reached S$27.2 billion, nearly back to the S$27.7 billion recorded in 2019 before the pandemic. For 2024, Singapore expected around 15 million to 16.5 million visitors. When those numbers move, they don’t just affect hotels and airlines. They flow straight into footfall, sales, and tenant demand at dominant downtown malls.

That’s why ION Orchard matters. It’s not merely well-located; it’s positioned at the premium end of demand. With more than 300 tenants spanning watches and jewellery, fashion, beauty and wellness, and lifestyle, it gives CICT direct exposure to the luxury and destination retail spend that tends to recover fastest when travel returns.

Still, geography cuts both ways. A portfolio anchored this heavily in one country is, by definition, more exposed to that country’s economic and demographic cycles.

Singapore is diversified, but it is also deeply plugged into global trade and financial services. A sharp downturn in either can hit both sides of CICT’s house at once: office demand softens as firms cut headcount or shrink footprints, while retail sales slow as consumers and tourists pull back. And longer term, an aging population raises questions about how domestic consumption evolves over time.

There’s also execution risk that comes with staying at the top of the market. Premium acquisitions and ongoing property enhancements require capital, and that can pressure returns if office demand weakens under hybrid work trends or if rental growth slows.

The counterweight to all of this is Singapore’s density—one of the most underrated drivers of retail resilience anywhere in the world. Singapore isn’t built like the American suburbs, where e-commerce could hollow out drive-to strip centers. Here, malls are stitched into daily life. MRT stations often connect straight into mall basements. Housing nodes feed directly into retail nodes. For the best-located assets, convenience isn’t a tenant strategy; it’s urban design.

So yes: investing in CICT is a bet on Singapore. If you believe the city will keep winning as a hub for capital, talent, and tourism, CICT offers one of the cleanest expressions of that thesis—prime properties, active management, and a sponsor ecosystem designed to keep the platform compounding.

XII. Key Metrics and What to Watch

CICT can feel complex—26 properties, multiple asset classes, a sponsor ecosystem, and a steady drumbeat of acquisitions and enhancements. But if you want a simple dashboard for how the story is going, it comes down to three signals.

1. Distribution Per Unit (DPU) Growth

DPU is the REIT version of earnings per share: the clearest, most investor-relevant scoreboard for whether the platform is actually creating value. For FY 2024, CICT reported DPU of 10.88 cents, up 1.2% year-on-year.

What to watch: steady DPU growth over time usually means the fundamentals are doing their job—positive rent reversions, disciplined cost control, and acquisitions that add more income than they dilute. If DPU stalls or drops, the next question is simple: is it a temporary dip (for example, disruption from a renovation) or something more structural, like softer tenant demand?

2. Occupancy Rate and Rent Reversions

In FY 2024, CICT’s portfolio remained highly occupied, with committed occupancy of 96.7%. And in Singapore, it achieved positive rent reversions in both core segments: 8.8% for retail and 11.1% for office.

These two metrics tell you, in plain terms, whether tenants still want what CICT owns—and whether they’re willing to pay more for it. High occupancy says the buildings are still the addresses people choose. Positive rent reversions say CICT isn’t just filling space; it has pricing power. Over the long run, that’s the oxygen for DPU growth.

3. Aggregate Leverage and Cost of Debt

REITs live and die by their balance sheets, because debt is part of the business model—not a side note. For FY 2024, CICT’s aggregate leverage was 38.5%. Its average cost of debt was 3.5%, with 76% of total borrowings on fixed interest rates. Its debt maturities were well spread out, with an average term-to-maturity of 3.5 years.

What to watch: the key here is flexibility. Singapore’s MAS caps REIT leverage at 45% (or 50% if the interest coverage ratio is above 2.5x). At 38.5%, CICT kept meaningful headroom—useful for acquisitions and asset enhancement projects—without pushing the balance sheet into a corner if rates stay higher for longer or capital markets tighten.

XIII. Investment Considerations

CICT is easy to admire: dominant Singapore assets, real scale, and a sponsor that can keep feeding the machine. But like any REIT—especially one this concentrated in one city—there are trade-offs worth looking at head-on.

The Bull Case

Start with the simple advantage that’s hardest to copy: CICT owns a set of addresses that are effectively irreplaceable. These are the malls, offices, and integrated developments that sit on the city’s most valuable land. The ION Orchard acquisition didn’t just add another retail asset. It added the premier luxury mall on the country’s marquee shopping belt, deepening CICT’s grip on the kind of space tenants fight to get into.

Then there’s the sponsor engine. The relationship with CLI matters because it can keep the pipeline stocked and the execution sharp. CLI brings sourcing reach, operating expertise, and the balance sheet and relationships of a major real estate investment manager—support that can be especially valuable when markets turn and capital becomes scarce.

And the macro backdrop, while never guaranteed, has been unusually supportive for premium commercial space. Singapore’s role as a wealth management hub, tourism destination, and regional headquarters location underpins demand for the kinds of offices and retail nodes CICT owns. Add in Singapore’s tightly managed development environment—where meaningful new supply takes time and permission—and you have a market structure that can protect occupancy and support rents.

Finally, CICT’s portfolio construction is designed for resilience. It’s not a single bet on one mall, one district, or one property type. Suburban and downtown retail, Grade A offices, and integrated developments can respond differently across cycles. When one segment softens, another can help carry the platform.

The Bear Case

The same focus that makes CICT a clean “Singapore proxy” is also the concentration risk. If Singapore faces an extended period of economic strain—whether from a global downturn, intensifying regional competition, or domestic policy missteps—there’s no obvious geographic hedge inside the portfolio. The whole platform feels it.

Office demand is the other big structural question. Hybrid work hasn’t played out as severely in Singapore as in some Western markets, but the long-term equilibrium is still uncertain. Even around the merger, unitholders were already raising concerns about what hybrid work models could mean for the office segment, particularly in Singapore.

Retail has its own long-running challenger: e-commerce. Singapore’s density, public transport connectivity, and mall-centric urban design make its best malls more defensive than many global peers, but the shift in consumer behavior is real—and categories that move online can change the economics of physical space over time.

Then there’s the rate environment. Higher interest rates have compressed REIT valuations broadly, and a “higher for longer” scenario can continue to pressure both funding costs and investor sentiment—even if property operations remain steady.

And lastly, the sponsor relationship cuts both ways. Related-party transactions require constant discipline. Governance can mitigate conflicts, but it can’t erase the reality that incentives aren’t perfectly aligned: CLI earns fees around transactions and management, while unitholders ultimately want only deals that are truly value-accretive after financing and integration risk.

The Numbers in Context

On a closing price of S$1.93 per unit on 31 December 2024, CICT’s FY 2024 distribution yield was 5.6%.

That sits above Singapore 10-year government bond yields of roughly 2.5% to 3% at the time—essentially the market offering a risk premium for taking equity and real estate exposure. Whether that spread is “enough” depends on what you believe about future rents, interest rates, and how much uncertainty you’re willing to tolerate.

Another lens investors often use is price-to-book: what the market is paying relative to the REIT’s net asset value. That multiple tends to swing with rates and sentiment. Premium platforms like CICT have historically traded at or above book value when investors believe management can keep creating value through leasing, asset enhancements, and disciplined acquisitions.

XIV. Concluding Observations

CapitaLand Integrated Commercial Trust’s arc—from Singapore’s first mall REIT to one of the region’s flagship commercial real estate platforms—ends up mirroring the Singapore story itself: build the rules carefully, execute methodically, and keep upgrading through every crisis.

Along the way, the portfolio has been stress-tested by SARS, the Global Financial Crisis, and COVID-19. Each shock forced the same question in a new form: do people still shop, work, and gather in the physical places this REIT owns? Each time, CICT and its predecessors adapted—and kept compounding. The 2020 mega-merger folded retail and office into a single vehicle built for integrated developments. The ION Orchard acquisition did something even more symbolic: it pulled one of the country’s most iconic retail landmarks into the platform.

That’s the asset story. The structural story is the machine behind it: a sponsor ecosystem that can source and manage institutional-quality buildings, and a regulatory model that pushes REITs to return cash to unitholders rather than hoard it. For investors, that combination—trophy locations, professional management, and a built-in distribution engine—is the core appeal.

But the trade-off is also clear. CICT’s Singapore concentration is both the advantage and the risk. If you’re bullish on Singapore’s continued role as a global hub for capital, tourism, and regional headquarters, CICT is one of the cleanest, most liquid ways to express that view. If you’re cautious about single-country exposure—or worried that offices and retail face a structurally different future—then the same focus can look less like conviction and more like concentration.

What’s hard to argue with is that the platform has momentum. FY 2024 reflected a portfolio with real pricing power and high occupancy, and the ION Orchard deal further sharpened CICT’s positioning in the downtown core. In other words: more of the best Singapore, not more geography for geography’s sake.

What began with a handful of suburban malls in 2002 has become a defining commercial REIT in Asia. The next chapter—whether it’s further consolidation, selective overseas growth, or deeper investment in integrated, mixed-use “city nodes”—will be written in the same way the last two decades were: against a shifting global economy, and Singapore’s ongoing project of staying indispensable.

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music