BlueScope Steel: The Reinvention of Australia's Steel Giant

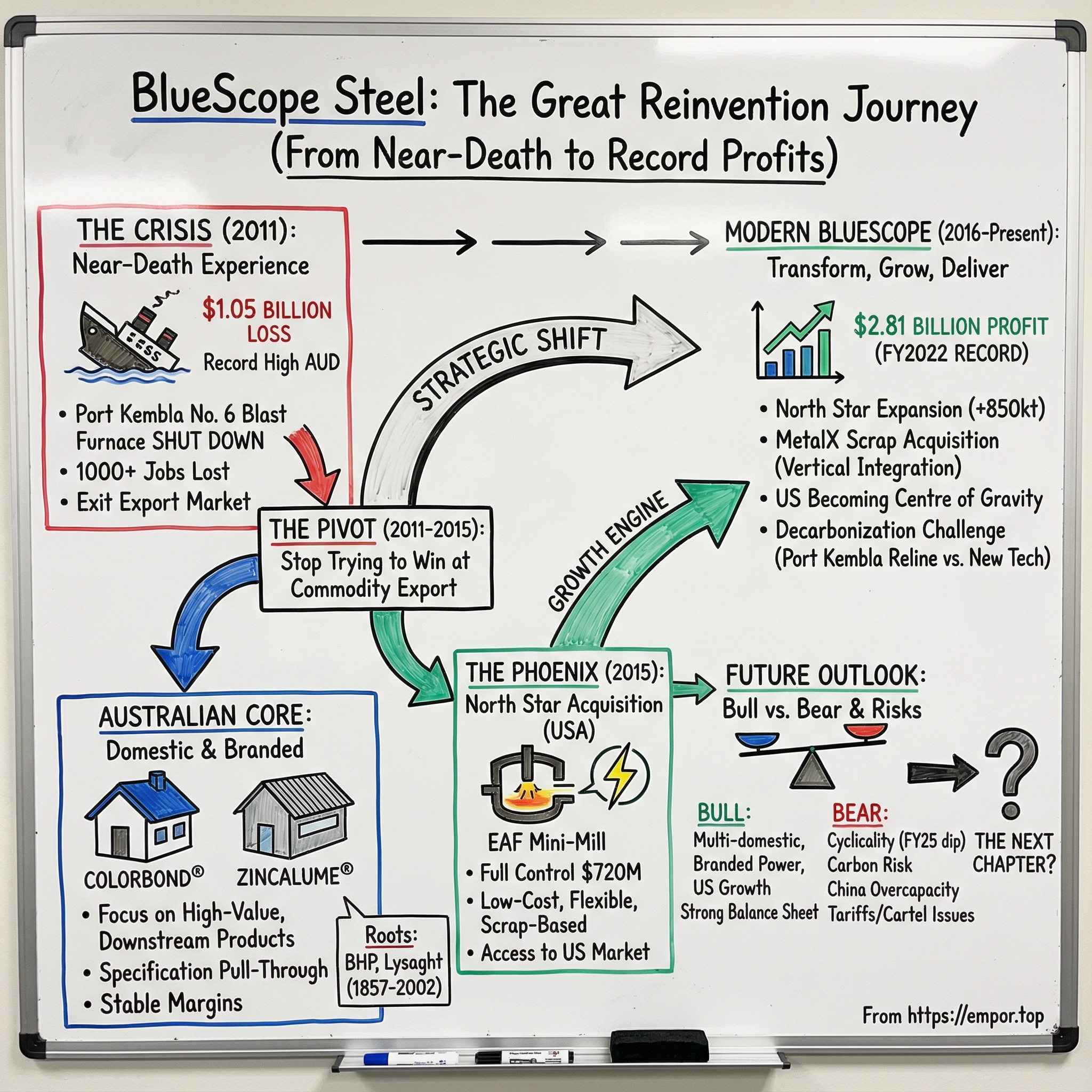

I. Introduction: From Near-Death to Record Profits

In the winter of 2011, something happened in Wollongong that would’ve sounded impossible to three generations of Australian steelworkers. At Port Kembla, inside the hulking silhouette of No. 6 Blast Furnace—a furnace that had been relined just two years earlier at enormous cost—the fires were going out. Not for a scheduled shutdown. Not for an upgrade. For good.

Outside the gates, workers who’d spent decades in the orange glow of molten steel stood there trying to make the math work in their heads: how do you go home and explain that the job you thought you’d retire from—the job your dad had, and his dad before him—was disappearing?

The human toll landed immediately. The closure wiped out 300 contractor roles and 800 permanent jobs. Port Kembla’s workforce fell to about 2,300 positions, and the damage rippled outward. Many more people across the region lost work through flow-on effects, and University of Wollongong modelling predicted that 200 businesses would be directly hit.

And this is the twist: that moment—the one that felt like the end—was the beginning of BlueScope’s reinvention.

BlueScope Steel Limited is an Australian flat product steel producer that was spun off from BHP Billiton in 2002. Today it operates across fifteen countries and employs around 16,000 people. But the reason this story is worth your time is the question at its center: how did a company that posted a billion-dollar loss in 2011—after slashing production capacity and shedding thousands of jobs—turn into a record-profit global player with one of the most profitable steel mills in North America?

The answer isn’t a miracle recovery or a lucky cycle. It was a pivot built on an unusually clear-eyed admission: BlueScope wasn’t going to win as an Australian-based exporter of commodity steel, especially in a world flooded with lower-cost production. So it did something most legacy industrial companies struggle to do. It stopped trying.

What followed was a reinvention anchored in branded, value-added products like COLORBOND and ZINCALUME, and a single, decisive move that changed the company’s trajectory: taking full control of its North Star mini-mill in the United States. All of it played out under a new reality the steel industry can’t ignore—decarbonization—where blast furnaces and the future don’t naturally go together.

This isn’t just an Australian industrial saga. It’s a case study in what it looks like when a heavy manufacturer survives global overcapacity, a punishing cost base, and structural change by cutting back to what it can be great at—and then placing one big bet in the right geography, with the right technology.

Because the decisions BlueScope made between 2011 and 2015, the ones that looked catastrophic in the moment, became the foundation for what would be, by 2022, the most profitable year in its history as an independent public company.

II. The Deep Roots: BHP, Lysaght, and Australian Steel (1857-2002)

BlueScope’s story starts in a place you wouldn’t expect for an Australian steel giant: Victorian-era Bristol, with corrugated iron and an Irish entrepreneur who could smell demand from half a world away.

In 1857, John Lysaght & Co. set up at St Vincent’s Works and began manufacturing corrugated iron. It didn’t take long for Lysaght’s sheets to travel. The company exported to markets including Australia and South America—anywhere growing fast enough to need building materials yesterday.

Australia, in particular, was a perfect storm of timing and necessity. The gold rushes of the 1850s didn’t just bring people; they brought an urgent need for shelter, stores, sheds, churches—whole towns, built quickly, often in places with little local manufacturing. Corrugated iron was ideal: light enough to ship, tough enough for harsh conditions, and versatile enough to become everything from miners’ shacks to wide, shaded verandas.

By 1880, Lysaght was shipping so much product that it set up a central selling agency in Melbourne. And by 1913, the scale was enormous for the era: about 85,000 tonnes of Lysaght’s ORB-branded corrugated iron were arriving in Australia each year—around seventy percent of the company’s total output, and roughly the same share of the Australian market.

Then World War I snapped the supply chain. Britain redirected industrial capacity to the war effort, exports collapsed, and Australia got a blunt lesson in the risk of relying on imports for basic industrial materials. In response, John Lysaght (Australia) Pty Ltd was incorporated in 1918, and the business shifted from selling imported iron to making it locally. In 1921, a sheet rolling and galvanising works opened in Newcastle—right next door to BHP.

That decision mattered. It turned Lysaght into a permanent industrial player in Australia, not just a brand stamped on imported sheets.

The second strand of BlueScope’s DNA runs through the Hoskins brothers—and through a classic industrial origin story: a struggling asset, a bold buy, and a relentless push to scale. In 1907, G and C Hoskins took over the Lithgow steelworks after the previous owner ran into financial trouble. The deal included not just the works, but the whole ecosystem: a blast furnace, colliery, iron leaseholds, raw materials, and a valuable seven-year government contract. George stayed focused on the Sydney side of the business. Charles moved to Lithgow in 1908 and set about building an iron and steel operation that could endure.

Charles Hoskins was tough and uncompromising—no friend to unions, committed to freedom of contract, and a leader in the Iron Trades Employers’ Association. But he was also pragmatic. Lithgow had a problem you couldn’t negotiate away: location. Inland transport was expensive, and access to raw materials was a constant drag on competitiveness. World War I kept the works going longer than it otherwise might have, but by the early 1920s the Hoskins family had decided to move. They formed Australian Iron & Steel and planned a relocation to a site that could actually win on economics.

That site was Port Kembla—chosen for a reason that would echo through the next century of Australian steel: it was the nearest deep-water port to Sydney. On 29 August 1928, the first blast furnace at Port Kembla was blown in. It worked. And once it did, the old era ended quickly. By mid-November 1928, both Lithgow blast furnaces were shut down, destined to be demolished for scrap as production shifted to the coast.

The third strand is BHP itself. BHP’s steelmaking began in Newcastle in 1915, part of a broader ambition to use Australia’s resources to build a strong domestic industry. Newcastle gave BHP what steel needs to thrive: access to coal, proximity to infrastructure, and the ability to scale.

Over time, these three streams—Lysaght’s coated products and distribution, the Hoskins-built Port Kembla steelmaking base, and BHP’s industrial muscle—were pulled into one corporate body. BHP acquired Australian Iron & Steel in 1935. Decades later, it gained full ownership of Lysaght in 1979. By the late twentieth century, BHP’s steel division spanned the whole value chain, from steelmaking to finished coated products.

And inside that BHP era were two innovations that would later become BlueScope’s lifelines. In 1966, the first coil of COLORBOND® steel came off the Number 1 coil painting line at Port Kembla. It wasn’t a quick win—getting the process right took sustained effort—but it created something far more valuable than another steel grade: a product people would ask for by name.

Then in 1976 came ZINCALUME® steel, launched after extensive research and development. It set new standards for corrosion resistance and longevity, designed specifically to handle punishing climatic conditions.

Over time, these weren’t just materials. They became part of Australia’s built environment: the COLORBOND fence, the ZINCALUME roof. But the strategic significance ran deeper. They represented something commodity steel can’t easily deliver—brand recognition, specification pull-through, and the ability to earn a premium.

That distinction mattered because the corporate owner of these assets—BHP—was changing. After the 2001 BHP-Billiton merger, the new global mining company wanted to be exactly that: a mining company. Steel was capital-intensive, cyclical, and increasingly out of step with the portfolio. So BHP spun off its steel assets on 15 July 2002 as BHP Steel. On 17 November 2003, it took the name BlueScope.

The newly independent company inherited more than a century of industrial history. It also inherited a structural challenge that would soon become unavoidable: Australia was becoming a high-cost place to make export commodity steel. BlueScope still ran two blast furnaces at Port Kembla and sold into global markets. And just over the horizon, cheap steel from China was about to flood the system.

The crisis of 2011 didn’t come out of nowhere. The ingredients were already on the bench.

III. Independence & Early Ambition: The Global Buildout (2002-2008)

When BlueScope arrived on the Australian Stock Exchange in July 2002, it didn’t present itself as a doomed legacy manufacturer clinging to the past. It came out with a crisp ambition: become an international “steel solutions” company. Translation: less dependence on raw, undifferentiated steel, and more money made downstream—through coating, building products, and customers who bought outcomes, not tonnage.

The first big step came fast. In early 2004, BlueScope merged with Butler Manufacturing in the United States. On paper, it was clean and logical: two companies with similar cultures, operating in different markets, suddenly able to offer each other reach. Butler, based in Kansas City, Missouri, had been around since 1901 and focused on non-residential buildings and building components. It operated across sixteen countries, with around a dozen production facilities spread through the U.S., China, and Mexico. For BlueScope, it wasn’t just an acquisition—it was a landing pad.

And it mattered that Butler wasn’t simply “more steel.” It was steel applied to a job: pre-engineered buildings for industrial and commercial customers. That fit BlueScope’s instinct to move away from being judged on global steel prices and toward being chosen for reliability, service, and finished solutions.

In 2007, BlueScope pushed further into North America by acquiring four businesses from the Argentinian firm Ternium: Steelscape, ASC Profiles, Varco Pruden Buildings, and Metl-Span. These assets had previously been part of Grupo IMSA before Ternium bought them. And one of them—Steelscape—came with a quiet bit of symmetry: it began in 1996 as BHP Coated Steel and had originally been owned by BlueScope. Now, only a few years after independence, BlueScope was buying it back. Not nostalgia—strategy. These were the kinds of downstream, coated, building-adjacent businesses BlueScope wanted to own.

The expansion story didn’t stop in the West, either. In March 2012, a new coated steel manufacturing plant was inaugurated in Jamshedpur, India, through a joint venture with Tata. And the NS BlueScope joint venture with Nippon Steel strengthened the company’s footprint across ASEAN. The map was getting bigger. The portfolio was getting more value-added.

But while BlueScope was building these newer, more resilient legs, the old core back home was becoming harder to ignore. Australia—especially the two blast furnaces at Port Kembla—was still geared toward export volumes that were getting less and less economic. The Australian dollar was strengthening as the commodities boom rolled on. Low-cost steel, especially from China, was washing through Asian markets. And domestic demand couldn’t absorb everything Port Kembla could produce.

So the company carried a contradiction: a future being assembled through coated products and building solutions, and a legacy export steel machine that was drifting out of competitiveness. Then the global financial crisis hit in 2008, and the world got less forgiving.

The question BlueScope had managed to postpone during the expansion years was about to become unavoidable: could Australia compete as a commodity steel exporter? And if the answer was no, what do you do with half a steelworks?

IV. The 2011 Crisis: Near-Death Experience & The Pivot

By 2011, the storm BlueScope had been sailing toward finally hit—hard. Management described an “unprecedented combination” of pressures all landing at once: a record-high Australian dollar, steel prices that refused to cooperate, raw material costs that wouldn’t come down, and weak demand at home. Chairman Graham Kraehe put it plainly: “We are experiencing significant economic challenges and structural change in the global steel industry.”

The Australian dollar was the dagger. Supercharged by the mining boom, it surged to parity with the U.S. dollar—and even above it—at exactly the moment BlueScope needed every advantage it could get as an exporter. In a business where global prices are set in global markets, the currency move didn’t just shave margins; it rewrote the economics of making commodity steel in Australia.

And the financial statements didn’t leave room for denial. For the year ended 30 June 2011, BlueScope reported a AU$1.05 billion net loss, a violent reversal from a AU$126 million profit the year before. A swing like that doesn’t get fixed with a few efficiency projects. It forces a decision about what kind of company you actually are.

BlueScope made that decision in late August 2011, in an announcement that landed like an earthquake in the Illawarra. The company said it would shut two major production facilities and cut around a thousand jobs as part of a restructure aimed at stopping the bleeding. The headline moves were stark: shut down No. 6 Blast Furnace at Port Kembla in New South Wales, and close the Western Port hot strip mill in Hastings, Victoria. The job losses were just as stark—about 800 at Port Kembla and another 200 at Western Port.

A few weeks later, the plan became reality. In October 2011, No. 6 Blast Furnace—one of two at Port Kembla—was shut down, cutting the site’s production capacity in half after BlueScope decided to exit the export market.

Sit with what that means. This wasn’t a minor retrenchment. It was a company publicly admitting that an entire leg of its model—Australian-made export steel—was no longer viable. It was choosing to be smaller in order to survive.

Kraehe framed it as alignment: the closures would better match production with Australian domestic demand, and BlueScope would stop exporting its products. “The restructure announced today will produce a more viable and sustainable Australian steel business and allow us to focus clearly on domestic markets,” he said. Managing director Paul O’Malley argued the same logic in operating terms: the changes would materially improve earnings and cash flow, reduce export losses, and reduce volatility. “It’s the right decision for the long-term viability of our business,” he said.

But “alignment” is a bloodless word when you’re living inside the consequence.

Wollongong wasn’t just near the steelworks; it was built around it. Port Kembla had been the centrepiece of the local economy and employment prospects since it was established in 1928 and acquired by BHP in 1935. By the 1970s, the sprawling operation employed nearly 30,000 workers and contractors. Now the region was being told that the modern version of that story would be measured in a few thousand jobs—if that.

The stories that circulated at the time were exactly what you’d expect in a single-industry town when the core industry contracts overnight. One worker spoke about his brother—45 years old, at the steelworks since he was 16, working on No. 6—who would “definitely” lose his job. “It will change their lives,” he said. “He is foreman over there and he has to tell his workers that they are all in the same boat. It is a disaster for Wollongong.”

And still: the strategic logic held. This wasn’t cost-cutting for its own sake. It was BlueScope drawing a hard line around what it could be great at. Not exporting commodity steel from a high-cost country, but serving the domestic market with higher-value products—and leaning into the downstream businesses where brand, specification, and service mattered.

Cutting fifty percent of production capacity is the kind of move most companies avoid until they’re forced. Many would have tried to ride it out, praying for the currency to fall or the cycle to turn, bleeding cash quarter after quarter. BlueScope chose the uglier path: accept reality, take the pain, and build something survivable on the other side.

What almost nobody standing outside Port Kembla’s gates in 2011 could have known was that this was the first half of a two-part reinvention. The exit from export steel would stabilize the Australian business around domestic demand and branded products like COLORBOND and ZINCALUME. And the capital and flexibility created by that retreat would soon be redeployed into a move that would shift BlueScope’s centre of gravity—away from blast furnaces, and toward a very different kind of steelmaking asset in the United States.

V. The Phoenix: The North Star Acquisition (2015)

If the 2011 restructuring was BlueScope’s near-death experience, then 2015 was the moment it stopped merely surviving and started building a new centre of gravity.

For years, BlueScope had quietly owned half of a very different kind of steel asset in the United States: North Star BlueScope Steel, a mini-mill in Delta, Ohio that began operating in 1997. It produced roughly 2 million tonnes of hot rolled coil a year. And unlike Port Kembla, it wasn’t tied to the economics of blast furnaces, iron ore, and coking coal.

North Star ran on electric arc furnace technology. Instead of smelting iron ore, it melted scrap steel. That single technology choice changed almost everything: lower capital intensity, faster cycles, more flexibility to match output to demand, and—crucially in a world marching toward decarbonization—lower carbon intensity than traditional blast furnace operations.

It also happened to be extraordinarily profitable. Bloomberg News described the Ohio plant as North America’s most profitable steel mill.

Then the opportunity arrived. Cargill, which owned the other half, decided to exit steel production entirely. BlueScope didn’t need to search for a deal; it needed to decide whether to take one. It exercised its right of last refusal, matching an offer from an unnamed third party, and in October 2015 agreed to buy Cargill’s remaining 50 percent stake for $720 million—taking full ownership of the mill.

The rationale wasn’t subtle. BlueScope pointed to what makes a mini-mill win: North Star was “centrally located within a large scrap pool,” close to its core markets, with low conversion costs and a “highly motivated and focused workforce.” CEO Paul O’Malley framed the bigger strategic point: full ownership would enhance portfolio value and optionality, improve flexibility, and deliver on BlueScope’s strategy of being cost competitive in steelmaking with a best-in-class asset.

The brilliance here is that BlueScope wasn’t abandoning steelmaking. It was relocating its most competitive steelmaking exposure to the geography and technology where it could actually win. Low-cost steelmaking—yes. But in America, not Australia.

That contrast would only sharpen with time. Australia’s energy costs made large-scale commodity steelmaking increasingly hard to justify. The U.S. looked different. And by 2019, with lower energy prices in the United States than at home, BlueScope decided to expand its investment there by $1 billion.

The North Star deal also didn’t happen in a vacuum. It landed while BlueScope was still tightening the belt in Australia—cutting labour costs by $60 million, eliminating 500 jobs (about 10 percent of its Australian workforce), and freezing wages. A tax agreement with the New South Wales state government was described as crucial to keeping Port Kembla open.

This wasn’t an either/or bet. It was a deliberate split-screen strategy: right-size Australia around domestic demand and higher-value branded products, while building a growth engine in the U.S. around a world-class mini-mill.

And once North Star’s earnings were fully consolidated, the turnaround started to look less like hope and more like a plan working.

VI. Transform, Grow, Deliver: The Modern BlueScope (2016-Present)

With North Star fully in the fold and the Australian business reshaped around domestic demand, BlueScope moved into a new era. Management put the plan into three words: “Transform, Grow, Deliver.” And if you want to see what “Grow” looked like in practice, you look to Delta, Ohio.

BlueScope set about expanding North Star with what it called its biggest single capital project: adding roughly 850,000 tonnes a year of new capacity at the mini-mill. The first coil from the expansion was produced in June 2022, and the business began the long, practical work of ramping up over the following 18 months. At full run rate, BlueScope expected North Star to represent around five percent of total annual U.S. flat steelmaking production.

This expansion built on a major step-change at the site: a third electric arc furnace coming online in 2022 as part of a US$735 million investment. The point wasn’t just “more steel.” It was more of the right kind of steelmaking, in the right market, supplying U.S. domestic demand in sectors like automotive, agriculture, and construction.

But an electric arc furnace mill lives and dies by one input: scrap. So BlueScope made another move that looks obvious in hindsight and feels quietly brilliant in the moment. In 2021, to help secure scrap feed for the growing North Star operation, it invested US$325 million to acquire three nearby scrap recycling facilities. Those assets now operate under the banner of BlueScope Recycling and Materials.

MetalX, BlueScope noted at the time, was North Star’s largest scrap supplier, providing around 20 percent of the mill’s scrap. Bringing that capability in-house gave BlueScope more than supply security. It brought processing expertise, improved access to both prime and post-consumer (obsolete) scrap, and the ability to lift the quality and quantity of obsolete scrap used at North Star—reducing reliance on prime scrap.

The operational logic was tight: control the critical input, reduce vulnerability, and give the mill more options when markets get choppy. And the sustainability tailwind was real, too. An EAF operation using scrap starts from a fundamentally lower-emissions position than traditional blast-furnace steelmaking.

All of that set the stage for a watershed year. Fiscal 2022 became the most profitable year in BlueScope’s history as an independent listed company. The company reported net profit after tax of $2.81 billion. Managing Director and CEO Mark Vassella called it “a record performance in BlueScope’s 20-year history as a listed company,” with underlying EBIT of $3.79 billion.

That headline number matters, but the contrast matters more. In just over a decade, BlueScope went from a billion-dollar loss in 2011 to a $2.8 billion profit in 2022—one of the sharper reinventions in Australian industrial history. North Star was the standout contributor, with earnings (EBIT) rising 181 percent to $1.9 billion. The Australian steel division also surged, lifting EBIT by 92 percent to $1.29 billion, helped by strong construction and manufacturing demand for painted steel products, including the flagship COLORBOND roofing line.

At the same time, BlueScope leaned harder into the other unavoidable project of modern steelmaking: proving the business can exist in a lower-carbon future. Port Kembla Steelworks achieved ResponsibleSteel™ site certification—making BlueScope the fourth steelmaker globally to be certified under the ResponsibleSteel™ Standard, and Port Kembla the first certified site in the Asia-Pacific region.

BlueScope also launched major decarbonisation collaborations. In the first half of FY2022, it signed memoranda of understanding with Rio Tinto to explore technology and process options for low-emissions steelmaking, and with Shell Energy Operations to explore renewable hydrogen projects at Port Kembla. The focus was practical: piloting an industrial-scale 10MW hydrogen electrolyser, along with hydrogen direct iron reduction and an iron melter, all powered by renewable electricity.

And then came the reminder that no strategy, no matter how well executed, can repeal the cycle.

In FY2025, BlueScope reported underlying EBIT of $738.2 million, down $601.0 million from FY2024. Net profit after tax fell to $83.8 million, $721.9 million lower than the year before. BlueScope Coated Products delivered a loss, hit by lower volumes and operational inefficiencies, and the company recognised a $438.9 million impairment against the unit’s goodwill and intangible assets as performance lagged and integration took longer than expected.

Vassella captured the uncertainty in the U.S. market with a phrase that stuck: “It is a bit of a maze,” he said, describing tariffs that were sometimes announced but didn’t materialise. “There’s lots of movement, there’s lots of volatility and variability.” The constant flux, he noted, weighed on demand as customers hesitated—waiting to understand the rules before committing to orders or inventory bets.

The takeaway from FY2025 wasn’t that the transformation failed. It was the more sobering lesson every steel executive eventually relearns: transformation can reduce volatility, but it can’t eliminate it. Steel is still capital-intensive, still tied to spreads and demand, and still capable of turning quickly when conditions tighten.

VII. The Product & Brand Story: COLORBOND, ZINCALUME & The Power of Downstream

To understand why BlueScope isn’t just “another steel company,” you have to understand the thing most steelmakers never get to have: products people ask for by name.

In Australia, COLORBOND® is that rare industrial brand that crossed over into everyday language. It’s become almost a generic term for painted steel roofing and cladding—the way people say “Kleenex” for tissues or “Xerox” for photocopying. That kind of recognition isn’t nice-to-have marketing. In a category where most output is indistinguishable, it’s a moat.

And it shows up in behavior. COLORBOND steel provides roofing for nearly half of all new Australian homes, and nine out of ten new homes use products made from COLORBOND steel. The brand started humbly: when it launched in 1966, COLORBOND was available in six colours. Today it comes in twenty—enough range to fit almost any build, and enough familiarity that it often becomes the default choice.

ZINCALUME® is the other half of the downstream story: less about colour and recognition, more about engineering credibility built over decades. Launched in 1976—back when the business was still John Lysaght Australia—ZINCALUME didn’t just add another product to the catalogue. It changed expectations in Australian metal roofing and the broader building market, by pushing coating technology forward.

The origin story matters here. Early experiments with aluminium and zinc alloy coatings were conducted by Bethlehem Steel in the United States. But Australian researchers at BlueScope (then John Lysaght Australia) refined and perfected the process so it could be produced reliably and consistently through continuous metal coating production.

The result was a very specific recipe: a coating made up of 55% aluminium, 43.5% zinc, and 1.5% silicon. It delivered excellent corrosion performance, strong forming capability, and availability in high-strength grades. ZINCALUME was the outcome of extensive research aimed at improving on traditional galvanised steel. By blending aluminium with zinc in an alloy coating, researchers found a way to dramatically improve corrosion resistance. Extensive testing indicated that ZINCALUME’s lifespan could be up to four times that of galvanised steel with a Z275 coating.

That isn’t just a technical spec. It’s an economic argument. A longer-lasting roof or wall system supports premium pricing and, just as importantly, creates switching costs through specification. Once architects and builders specify a product they trust—and customers recognize—it’s hard for an unbranded alternative to dislodge it on price alone.

This is the heart of BlueScope’s “steel solutions” model. Premium brands drive specification pull-through: architects specify COLORBOND because clients recognise it and feel safer choosing it; builders default to it because it simplifies the sales conversation; and homeowners request it by name. Brand investment creates demand, demand reinforces the brand, and the cycle feeds itself.

From there, the downstream logic keeps going. The LYSAGHT® building products division takes coated steel and turns it into finished building solutions—roofing systems, wall cladding, structural decking, and steel framing. In North America, the Butler and Varco Pruden businesses apply a similar playbook, but aimed at pre-engineered commercial and industrial buildings.

For investors, the key point is simple: these branded, downstream businesses don’t behave like commodity steel. They tend to generate stronger margins and more stable earnings than a pure hot-rolled coil producer. When spreads compress in steelmaking, COLORBOND and building products can provide ballast. That split—between “steel” and “steel solutions”—goes a long way toward explaining why BlueScope, even in a cyclical industry, has been able to build more resilience than many commodity-only peers.

VIII. Competitive Analysis & Strategic Position

Porter’s Five Forces is a useful way to pressure-test what BlueScope built: where it still has real exposure, and where it’s created genuine insulation. And the short version is this: BlueScope is still in steel, so it will never be “safe.” But it has made the competitive game a lot less brutal in the places that matter.

Porter's Five Forces Assessment:

Supplier Power: MODERATE

For Port Kembla’s blast-furnace operation, the critical inputs are iron ore and coking coal—and those supply chains are dominated by a small number of global giants, notably BHP, Rio Tinto, and Vale. In theory, that concentration gives suppliers leverage.

BlueScope’s response has been to shrink how much that leverage can hurt it. North Star shifts a meaningful portion of the company’s steelmaking away from ore and coal and toward scrap. And because scrap is the lifeblood of an electric arc furnace mill, BlueScope went one step further by vertically integrating into scrap supply with the MetalX acquisition. Add in long-standing commercial relationships with the mining majors (and BlueScope’s deep historical ties to BHP), and supplier power lands in the middle: real, but not suffocating.

Buyer Power: MODERATE-HIGH

Steel customers tend to be big, professional buyers—construction firms and automotive manufacturers that know the market, know the alternatives, and negotiate hard.

Where BlueScope changes the dynamic is in coated and painted products. COLORBOND and ZINCALUME aren’t just “steel, but branded.” In practice, they create specification lock-in. When a project is designed around COLORBOND, substituting a generic alternative can create compliance issues, raise warranty concerns, and trigger rework. That doesn’t eliminate buyer power, but it meaningfully blunts it in the segments where BlueScope has built brand and trust.

Threat of Substitutes: LOW-MODERATE

In roofing and cladding, you can choose other materials—concrete tiles, timber, composites. But steel keeps winning for practical reasons: strength-to-weight, fire resistance, and being termite-proof, all of which matter in Australian conditions.

The bigger threat isn’t a different material. It’s the same material arriving from somewhere cheaper. For BlueScope, imports are the substitute that really matters.

Threat of New Entrants: LOW

Building an integrated steelworks is the kind of project that scares off almost everyone. The capital requirements are enormous—on the order of billions, with something as basic as a blast-furnace reline costing over A$1 billion. On top of that, you have regulatory complexity, entrenched distribution networks, and decades of accumulated brand equity.

But “low new entrants” doesn’t mean “low new competition.” Imports effectively act like foreign entrants showing up at the border, ready to sell into Australia without having to build anything locally.

Competitive Rivalry: HIGH

Rivalry is high because the global steel industry is chronically oversupplied, with Chinese overcapacity a particularly intense source of pressure. In Australia, imported product competes aggressively on price. In the U.S., North Star fights in a crowded arena against established operators like Nucor, Steel Dynamics, and Cleveland-Cliffs.

BlueScope’s edge is less about outmuscling rivals and more about where it sits on the cost curve and how it earns its margins. North Star’s economics have been designed to win as a low-cost producer. In Australia, the coated and branded portfolio earns a margin premium that pure commodity players struggle to match.

Hamilton's Seven Powers Analysis:

Scale Economies: North Star benefits from scale in electric arc furnace steelmaking. The expansion to around 3 million tonnes a year makes it a meaningful U.S. player with real scale advantages, even if scale looks different here than in traditional, integrated blast-furnace operations.

Network Effects: Steel itself doesn’t have network effects in the classic sense. But COLORBOND has a faint version of them: the more it’s used, the more builders, installers, and designers become familiar with it, and the easier it becomes to specify it again.

Counter-Positioning: BlueScope’s post-2011 split strategy—domestic, branded value-add in Australia while building EAF steelmaking capacity in the U.S.—is a form of counter-positioning. Many commodity-focused competitors, especially large integrated producers, can’t easily pivot into a brand-led downstream model in Australia the way BlueScope has.

Switching Costs: High in coated products. Once COLORBOND or ZINCALUME is specified, switching midstream is expensive and disruptive. Familiarity matters too: installers who know the product, and builders who trust it, create additional friction for alternatives.

Branding: This is BlueScope’s most potent power in Australia. COLORBOND’s recognition and trust translate into pricing power and a durable preference that generic competitors can’t simply undercut away.

Cornered Resource: North Star’s location inside a large scrap catchment is a structural advantage, and the MetalX acquisition strengthens access to supply and processing capability. Port Kembla has its own version of a cornered resource: an integrated coastal industrial footprint refined over decades, along with the operational know-how embedded in the site.

Process Power: BlueScope’s coating technology is not a commodity capability. Decades of development at Port Kembla have created process advantages in producing coated products with consistent quality and strong corrosion performance—exactly the kind of advantage that shows up as reliability, reputation, and margin over time.

IX. Key Performance Indicators & Investment Considerations

If you’re trying to keep score on BlueScope as it exists today—part Australian branded building products, part U.S. electric-arc steelmaking—there are three operating signals that matter more than almost anything else.

1. North Star spreads (U.S. Midwest HRC price minus scrap cost)

North Star’s economics are built on a simple gap: what it sells hot-rolled coil for, versus what it pays for scrap. When that spread widens, North Star prints money. When it tightens, earnings can drop quickly.

That matters because North Star has become a major driver of group performance. CEO Mark Vassella said the mill was “really settling in nicely at that 3-million-metric-tons run rate.” The bigger North Star becomes inside BlueScope, the more this single spread becomes the swing factor for consolidated results.

2. Australian coated/painted steel margins and volumes

The other pillar is the Australian Steel Products division—built around COLORBOND, ZINCALUME, and the building-products ecosystem that turns coated steel into finished solutions.

Here, you want to watch two things together: margins and volumes. Margins tell you whether the brand-and-specification moat is holding, and whether costs are being managed. Volumes tell you what’s happening in the real economy—because after the 2011 pivot away from exports, Australian production is much more tightly linked to domestic residential and commercial construction cycles.

3. Capital expenditure intensity and return on invested capital

Steel rewards discipline and punishes wishful thinking. So the question isn’t “are they spending?” It’s “are they spending well?”

BlueScope has major capital commitments underway, including the current $1.15 billion blast furnace reline at Port Kembla and ongoing North Star debottlenecking investments. Tracking capex against output and earnings helps you see whether that spend is building productive capacity and resilience—or just keeping the machine running without improving the economics.

Material risks and overhangs:

Tariff and trade policy volatility: Vassella has called U.S. tariff settings “a bit of a maze,” pointing to the way uncertainty can freeze demand as customers wait for clarity before making buying and inventory decisions. BlueScope’s multi-domestic model—producing in-market for in-market consumption—offers some protection, but shifting policy still makes planning harder and results more volatile.

Decarbonization path: The $1.15 billion reline extends Port Kembla’s blast-furnace pathway for roughly two decades. Management has said it wants flexibility to adopt new technologies as they mature, but the hard reality is that the credible route to net-zero steelmaking at scale still depends on technologies that are not yet fully commercial.

Cartel conduct legal matters: In December 2022, the Australian Federal Court found that BlueScope and Ellis had attempted to induce eight steel distributors in Australia and an overseas manufacturer to enter agreements to fix and/or raise prices for flat steel products. BlueScope was ordered to pay a $57.5 million penalty, the highest ever imposed for cartel conduct in Australia. Beyond the financial hit, it’s a reputational overhang—and a reminder that in a market where BlueScope is a dominant player, regulators are watching closely.

X. Bull Case, Bear Case, and Final Observations

The Bull Case:

BlueScope is no longer the company that got cornered as an export-dependent commodity producer. It reshaped itself into something much harder to break: a multi-domestic steelmaker with two advantages that don’t usually coexist in the same portfolio—branded, value-added products in Australia, and a genuinely world-class mini-mill in the United States.

North Star is the centerpiece of that bull case. With the expansion taking it to a run rate above 3 million tonnes a year, BlueScope positioned itself as a meaningful player in U.S. flat steel—roughly five percent of national production—inside a market that has benefited from tariff protection and a broader push to rebuild domestic manufacturing capability. In Australia, the story is different but complementary: while demand is still cyclical, COLORBOND and ZINCALUME help the business earn a premium and smooth the ride versus pure commodity steel.

Add a strong balance sheet and a management team that has shown it can make hard calls—cutting Australian capacity when reality demanded it, then leaning into high-return U.S. steelmaking—and you can see why investors view BlueScope as a steel company that upgraded its odds.

The Bear Case:

For all the reinvention, steel is still steel. Earnings can swing fast, and the FY2025 impairment in the U.S. coated products business is a blunt reminder that not every acquisition or integration delivers the returns you underwrite at the start.

The bigger, longer-dated risk is decarbonization. The Port Kembla blast furnace reline extends a carbon-intensive pathway for roughly two decades. If carbon pricing tightens materially, or if customers move faster than expected toward low-emissions materials, that raises the specter of stranded-asset risk. Meanwhile, Chinese overcapacity continues to cast a long shadow over global pricing. And at home, import competition remains a constant pressure point—one that becomes more acute when local conditions make Australia an attractive destination for offshore steel.

There’s also a non-operating overhang: the cartel conduct finding. Beyond the penalty itself, it increases scrutiny and raises the perceived regulatory risk of being a dominant player in a concentrated market.

Final Observations:

BlueScope’s post-2011 journey is one of the more instructive industrial strategy stories you’ll find: a leadership team recognized what the company was not good at—competing as a high-cost exporter of commodity steel—and acted decisively. That retreat wasn’t the end of growth. It was what preserved the capital and flexibility to fund the next act.

And that next act was North Star. Buying full control of an asset BlueScope already understood, in a market with attractive structural characteristics, showed the value of patience—and the advantage of being ready when a rare opportunity appears.

If you’re looking at BlueScope today as an investment, the debate is less about whether the company improved—because it did—and more about whether that improvement is already fully priced in. The answer turns on two things: where steel spreads go next in both the U.S. and Australia, and whether management keeps allocating capital with the same discipline that defined the turnaround.

What’s not in question is how different the company is. In 2011, BlueScope watched the fires go out in No. 6 Blast Furnace. In 2026, those fires are scheduled to relight after the $1.15 billion reline. Whether that restart proves to be a well-timed extension of a critical asset—or a long commitment to a technology the energy transition ultimately leaves behind—may be the defining strategic choice of BlueScope’s next chapter.

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music