Keppel Ltd.: Singapore's Shape-Shifting Conglomerate

I. Introduction & Episode Roadmap

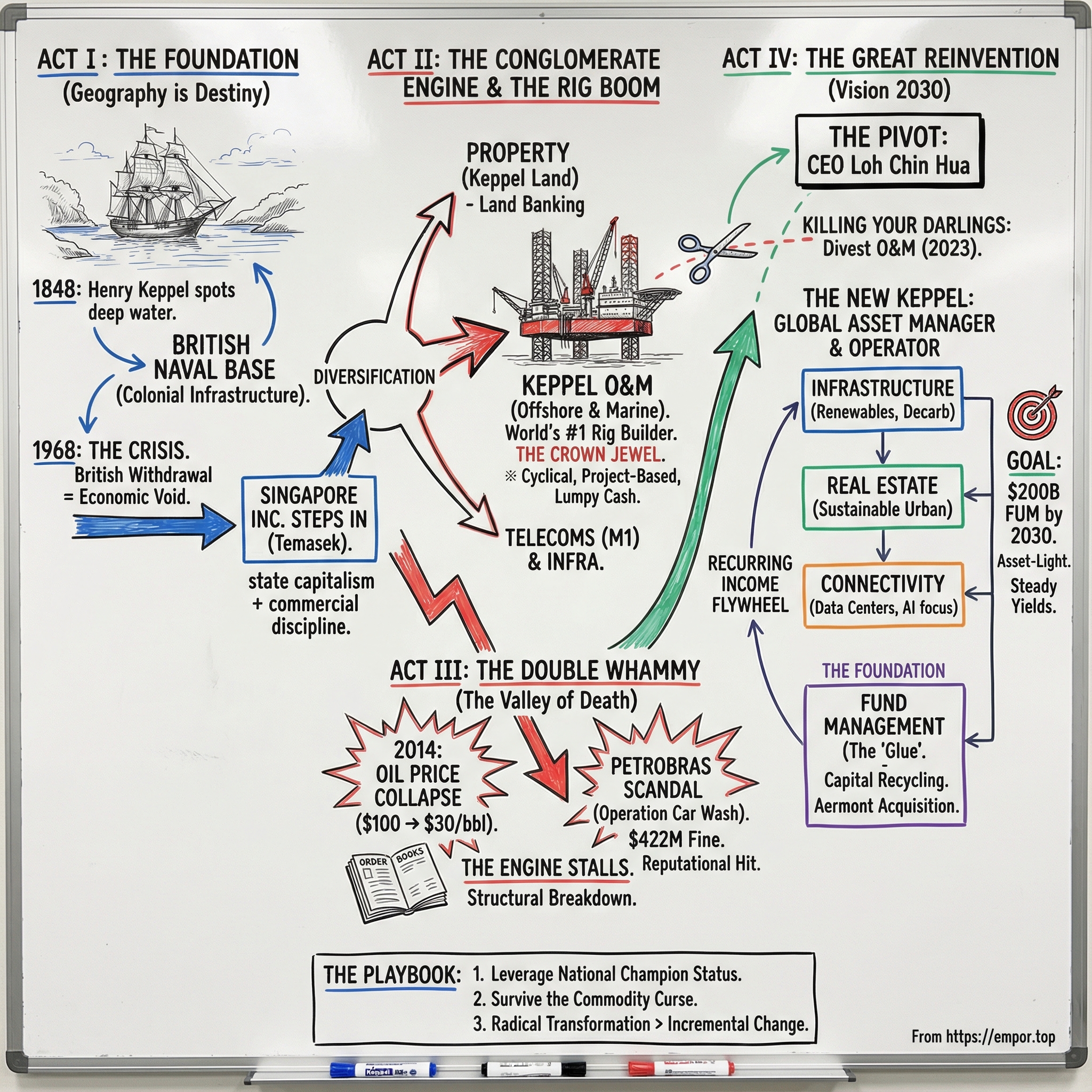

Picture this: it’s 1968, and the British Royal Navy is packing up its last ships from Singapore’s Keppel Harbour—the same deepwater anchorage first identified more than a century earlier by a young British captain named Henry Keppel while chasing pirates through the Strait of Malacca. The Union Jack comes down. A newly independent Singapore looks at the dry docks, the workers, the cranes, the whole waterfront economy the British are leaving behind—and faces an existential question: what happens next?

The answer set off one of the most dramatic corporate evolutions in modern Asia. It’s a story that runs through an oil rig empire and a global bribery scandal; through a commodity collapse that broke the old business model; and into a 2020s reinvention so complete it effectively changed what “Keppel” even means.

Today, Keppel Ltd. is a Singapore-headquartered global asset manager and operator with a footprint in more than 20 countries, focused on the real assets that keep modern life running: renewables and clean energy, decarbonisation, sustainable urban renewal, and digital connectivity. But that description would have sounded like science fiction to anyone who knew Keppel not long ago. For years, Keppel was best known as the world’s largest builder of oil rigs—an industrial powerhouse whose fortunes rose and fell with the price of crude.

So here’s the question that makes this whole story click: how did a colonial-era harbour repair operation become one of Singapore’s flagship conglomerates, survive both an oil-price freefall and a bruising corruption scandal, and then reinvent itself into something its founders couldn’t possibly have planned for?

We’ll follow three threads the whole way. First: “Singapore Inc.” and the government-linked company model—why Singapore’s particular brand of state capitalism can be a superpower, and also a set of guardrails. Second: the curse of commodity dependence—what it does to strategy, culture, and risk when your biggest business is tied to oil. And third: reinvention—what it really takes for a decades-old institution to tear down its own identity and build a new one without collapsing in the process.

And because this is Singapore, the story begins where it always does: with geography, ships, and the sea.

II. The Harbor That Built a Nation: Origins & Colonial Legacy

In May 1848, a British naval officer named Henry Keppel scribbled something into his diary that, in hindsight, reads like the opening line of Singapore’s modern economic history:

"In pulling about in my gig among the numerous prettily wooded islands on the westward entrance to the Singapore river, was astonished to find deep water close to the shore, with a safe passage through for ships larger than the Maeander. Now that steam is likely to come into use, this ready-made harbour as a depot for coal would be invaluable."

Keppel wasn’t a wide-eyed tourist. He was back in Singapore as captain of the Royal Navy frigate Meander, part of the colonial push to clear pirates from the Straits. And he immediately understood what he was looking at: a naturally deep, sheltered harbour—exactly the kind of infrastructure advantage that doesn’t need to be invented, just exploited. His survey of the waters around what we now call Keppel Bay later became a foundation for plans for a new harbour, completed in 1886.

Zoom out, and the strategic logic becomes even clearer. Singapore sits by the Strait of Malacca, the tight choke point connecting the Indian Ocean to the Pacific—and one of the busiest shipping lanes on Earth. In that context, Keppel Harbour wasn’t just a nice place to anchor. It was a natural service station for global trade: a place to stop, refuel, repair, and resupply. Its deep water and protection from the open sea fit perfectly with what British colonists needed to build a serious maritime outpost in the Far East—an advantage that would echo into Singapore’s eventual success as an independent state.

And the buildout came fast. Within Keppel Bay sit some of Singapore’s oldest docks. The first graving dock, Dock No. 1, was built in 1859. Dock No. 2 followed eight years later. These weren’t glamorous projects, but they were destiny: early proof that Singapore’s competitive edge would be physical infrastructure, heavy engineering, and the relentless, practical business of keeping ships moving.

For decades the area went by a plain, functional name: New Harbour. That changed on 19 April 1900, when Acting Governor Sir James Alexander Swettenham renamed it Keppel Harbour, honouring Keppel—by then a 91-year-old admiral of the fleet—who had returned on what amounted to a final tour of the places where he’d made his name.

As the docks grew, so did the state’s role. The Port of Singapore Authority was formed as a statutory board in 1964. Then in 1968, the Singapore Drydocks and Engineering Company was set up to take over the PSA’s Dockyard Department—one of the direct institutional bridges between colonial harbour infrastructure and the modern company that would eventually become Keppel.

And that’s why this origin story matters. Keppel’s DNA was forged here: in strategic geography, in industrial know-how, and in the pull of global trade. Those forces would become its rocket fuel—and, later, the source of some of its biggest risks.

The stage was set for the next chapter: when the British finally left, and Singapore had to decide what to do with the harbour that could build a nation.

III. Birth of a Nation-Builder: The Temasek Era Begins (1968–1980)

When the British announced their military withdrawal from Singapore in 1968, it wasn’t just a geopolitical headline. It was a looming economic shock. Keppel Harbour wasn’t a scenic waterfront; it was a working ecosystem—docks, cranes, workshops, and thousands of jobs tied directly to the Royal Navy’s presence. For Lee Kuan Yew’s newly independent government, the choice was stark: let the capabilities and livelihoods evaporate, or turn a military asset into a civilian engine of growth.

Singapore chose the second path.

In 1968, as Keppel Harbour was taken over from the British Royal Navy, Temasek Holdings founded Keppel Shipyard. This was industrial policy in its purest form: the state wasn’t simply setting the rules of the game. It was putting a team on the field.

To understand why that mattered, you have to understand Temasek. Incorporated on 25 June 1974 under the Singapore Companies Act, Temasek was created to hold and manage the Singapore government’s investments in government-linked companies—separating the government’s role as policymaker from its role as owner. The idea wasn’t day-to-day micromanagement. It was strategic stewardship: keep national champions competitive, well-capitalised, and aligned with the country’s long-term needs.

In those early years, Temasek’s portfolio read like a blueprint for building a nation from scratch. It held controlling interests in 35 original investments across Singapore’s economic “commanding heights,” including Neptune Orient Lines, Keppel Shipyard, Sembawang Holdings, the Development Bank of Singapore, Jurong Bird Park, Singapore National Printers, and Singapore Airlines. Not because Singapore wanted to collect logos—but because a small island with no hinterland couldn’t afford to be fragile in the sectors that kept it connected, financed, and employable.

Inside Keppel, the shift from dockyard to growth company happened quickly and deliberately. The company carried the name of Captain Henry Keppel, the British naval officer who first arrived in Singapore in 1848 and recognised the deepwater harbour at Tanjong Pagar for what it was: a natural advantage that could be turned into economic power.

Then came a move that, in hindsight, set the trajectory for decades. In 1971, Keppel entered shipbuilding and ship repair—and began moving toward rig-building—through the acquisition of a 40 percent stake in Far East Levingston Shipbuilding Ltd. It was a small stake with an enormous consequence: the early seed of what would later become Keppel Offshore & Marine, and eventually the world’s largest oil rig builder.

Keppel also did something Singapore’s government-linked firms often did when they needed to scale: it tapped public markets without giving up the state’s strategic grip. In 1975, Keppel went public to fund growth, while the Singapore government maintained majority ownership. In 1980, Keppel was listed on the Singapore Stock Exchange, cementing its arrival as a major public company—built with state intent, but operating with the demands of the market.

And even in the 1970s, you can see the beginnings of the conglomerate impulse. In 1978, Keppel ventured into finance by providing financial services to marine contractors under Shin Loong Credit (later renamed Shin Loong Finance), expanding what it could offer beyond engineering and into the money that kept the industrial machine running.

The strategic logic of this whole era is pretty straightforward. Singapore had limited land and virtually no natural resources. But it did have access to global trade routes, a relentless focus on execution, and the ability to marshal capital. Government-linked companies were the mechanism: build capabilities quickly, diversify thoughtfully, and reduce the risk that any single shock could take the country—and its champions—down with it.

Keppel’s foundation was set. Now it was ready to start building an empire.

IV. The Conglomerate Years: Diversification & Empire Building (1980s–2000)

If the 1970s were about proving Keppel could stand on its own, the 1980s and 1990s were about turning that proof into an empire. Keppel expanded fast and wide, and in a place like Singapore, that wasn’t corporate wandering—it was strategy. In a small, open economy with limited domestic demand, diversification wasn’t just a growth lever. It was insurance.

The most consequential early move came in 1983, when Keppel pushed into property by acquiring Straits Steamship Company. On paper, Straits Steamship was a shipping name. In reality, it was something even more valuable in a land-scarce city: a quiet vault of prime real estate accumulated over decades. Keppel didn’t need to spend years assembling a land bank plot by plot. It bought one in a single deal.

By 1989, the company was renamed Straits Steamship Land to reflect what it had really become. Eventually it would take on the name Keppel Land—one of the Group’s most enduring pillars, and a far cry from the dry docks where the story began.

Then came finance. In 1990, Keppel acquired Asia Commercial Bank, establishing banking and financial services as a serious growth pillar. The business was renamed Keppel Bank, and the success of the acquisition led to a listing in 1993. A few years later, in 1997, Keppel Bank acquired Tat Lee Bank, creating the enlarged Keppel TatLee Bank. It was classic conglomerate logic: if you’re building heavy industry and big projects, controlling a financing engine can make the whole machine run smoother.

That same year, Keppel placed another bet—this time on connectivity. Steamers, later known as Keppel Telecommunications & Transportation, spearheaded the Group’s participation in M1 in 1997. It was a move that looked like diversification in the moment, but decades later would read more like early positioning. M1 would go on to become the first operator in Singapore to offer nationwide 4G service, and later secured a licence to operate a 5G network—exactly the kind of strategic infrastructure asset that fits the “new Keppel” story we’ll get to.

Still, for all the new pillars, the crown jewel was taking shape offshore.

In 1999, Keppel Shipyard moved its operations from Keppel Harbour to Jurong. This wasn’t just a change of address. Jurong—and the surrounding yards in places like Tuas, Gul, and Benoi—gave Keppel room to scale its offshore and marine operations, with facilities clustered close together for efficiency. And it also freed up the original Keppel Harbour site for a very different future: redevelopment into a waterfront residential area.

At the turn of the century, Keppel made a pair of decisions that showed real discipline beneath the sprawl. In 2001, it divested its banking and financial services business—an admission, effectively, that it didn’t have the scale to win in a region full of banking giants. In the same period, it privatised and integrated its offshore and marine business. Then in 2002, Keppel Shipyard, Keppel FELS, and Keppel Singmarine were brought together under one banner: the Keppel Offshore & Marine group.

It was a pivot from “conglomerate everywhere” to “conglomerate, but with a true engine.” A focused, scaled global competitor in rig-building and marine engineering—built on Singapore’s industrial strengths, now packaged to dominate.

By the early 2000s, Keppel looked like the textbook Asian conglomerate: shipbuilding and rigs, property, telecoms, and more—diversified enough to weather shocks like the Asian Financial Crisis, where having multiple legs mattered.

But the structure also hid a growing vulnerability. Investors struggled to value a company that did so many different things. And more importantly, Keppel’s biggest profit machine was increasingly tied to a single external variable it couldn’t control: the oil cycle.

That variable was about to turn.

V. The First Inflection Point: Oil Price Collapse (2014–2016)

In June 2014, Loh Chin Hua had been CEO of Keppel for exactly six months. He wasn’t a shipyard lifer who’d come up through the yards; he was an investment professional—trained in capital markets, a CFA charterholder, and a former Singapore sovereign wealth fund (GIC) executive. He’d joined Keppel in 2002, built its private fund management arm, and later served as CFO before taking the top job.

He understood cycles. He understood risk.

But nothing really prepares you for the cycle that wipes out your flagship industry.

Oil had been a gift for Keppel for years. In 2012, crude traded above US$125 a barrel. It stayed above $100 into September 2014. Then it fell off a cliff—entering a steep downward spiral and dropping below $30 by January 2016.

Between mid-2014 and early 2016, the global economy went through one of the sharpest oil price declines in modern history. A roughly 70 percent drop—among the biggest since World War II, and the most prolonged since the supply-driven collapse of 1986.

For Keppel, this wasn’t a headline. It was the floor disappearing.

Keppel Offshore & Marine was the world’s largest oil rig builder. That meant its order book lived and died on one thing: how much oil companies were willing to spend exploring and drilling. When crude collapsed, exploration budgets got cut. And when exploration budgets got cut, the pipeline of new rig orders didn’t just slow—it froze.

And the oil collapse wasn’t a normal dip. The dynamics of the market had changed. As Loh later described it, by mid-2014 the emergence of shale oil had altered the balance, and OPEC was no longer acting as the swing producer. Keppel watched the oil price slide accelerate, and the pressure build fast.

The drivers looked structural, not merely cyclical: oversupply as unconventional US and Canadian tight oil reached meaningful scale; geopolitical rivalries among oil-producing nations; weakening demand as China’s economy decelerated; and the beginnings of longer-term demand restraint as environmental policy pushed fuel efficiency.

For offshore rig builders, the consequences were brutal. New orders dried up almost overnight. But it got worse: rigs already being built became stranded. They were completed or nearly completed, with no buyers—sitting in yards, tying up cash, and turning what had been a beautiful project business into a capital trap.

Keppel’s diversification had helped it for decades. But the oil engine was so large that when it sputtered, the whole conglomerate felt it. Loh later put it bluntly: “We’d been very successful as a conglomerate for many decades, but the market was changing. Our recurring income was low, and we were not attracting the kind of growth multiples that we wanted to see. To add insult to injury, the market was further penalising us through a conglomerate discount.”

The downturn exposed what the boom had disguised: Keppel’s earnings were too dependent on high-margin, lumpy project work. In good times, that model looked like genius. In bad times, profits could evaporate immediately—because there wasn’t enough recurring revenue to cushion the fall.

Financially, the direction told the story. Revenue slid from highs above S$13 billion in fiscal year 2014 to a lower, steadier band in later years, around S$6–7 billion annually. The offshore and marine segment—once the company’s pride—had become its heaviest drag.

And psychologically, it forced a question that would have been almost unthinkable during Keppel’s rise. As Loh reflected later: “If you look back at the source of Keppel, we started from the shipyard. This is the business that built up all our other businesses, so to spin it off or divest was a pretty tough decision.” Keppel concluded early that the 2015 downturn was structural, not a quick rebound. That meant painful actions: cutting costs, right-sizing operations, and divesting underperforming yards.

But before Keppel could fully digest what the oil collapse meant—and what it might have to become without rigs as its core—another crisis hit.

This one wouldn’t just challenge the business model. It would challenge the company’s integrity.

VI. The Second Inflection Point: The Petrobras Bribery Scandal (2015–2017)

In 2014, Brazilian police launched what they thought was a routine money-laundering probe tied to car washes and petrol stations. The early targets were small-time criminals. But the trail didn’t climb one rung at a time—it shot straight up into the country’s political and corporate elite, and into Petrobras, Brazil’s state-owned oil giant.

The investigation got a name that sounded almost absurd for what it uncovered: “Operation Car Wash.”

And in the middle of that expanding web sat Keppel’s crown jewel: Keppel Offshore & Marine.

According to admissions and court documents, beginning by at least 2001 and continuing until at least 2014, Keppel Offshore & Marine conspired to violate the FCPA by paying approximately $55 million in bribes to officials at Petrobras and to the then-governing political party in Brazil. The goal was simple: win business. The result, according to those same documents, was 13 contracts with Petrobras and another Brazilian entity.

The method was just as straightforward. KOM routed money through an intermediary, paying outsized “commissions” dressed up as consulting agreements. The intermediary then directed payments for the benefit of Petrobras officials and Brazilian politicians. On the outside, it looked like normal commercial paperwork. Underneath, it was a long-running system.

In 2017, the story detonated in public. Keppel Offshore & Marine—Keppel’s rig-building unit—agreed to pay around US$422 million in fines as part of a global resolution with criminal authorities in the US, Brazil, and Singapore. It was widely described as a record settlement for a cross-border corruption probe involving a Singapore-listed entity.

US authorities said Keppel Offshore & Marine Ltd. and its wholly owned US subsidiary, Keppel Offshore & Marine USA Inc., agreed to pay a combined penalty of more than $422 million. KOM USA pleaded guilty as part of the resolution. Court filings also revealed a guilty plea by a former senior member of KOM’s legal department, who admitted he had drafted contracts with a Keppel agent in Brazil while realising the agent was being overpaid by millions of dollars.

In Singapore, the Corrupt Practices Investigation Bureau took its own actions. It said the culpability of six individuals, the available evidence, and “what is appropriate in the circumstances” were taken into account in deciding not to prosecute those individuals and instead issue stern warnings.

For Singapore Inc., this wasn’t just a corporate scandal. It was a national reputational wound. Temasek—the state investment company and Keppel’s largest shareholder—was listed as owning a 20.43 percent stake. That made the questions unavoidable: oversight, governance, and what it really meant when a flagship government-linked company got caught up in a global bribery scheme.

The damage didn’t stop at Keppel. Singapore had built its international brand on transparency, rule of law, and clean administration. A corruption case involving one of its most prominent companies threatened that image precisely because it was so out of character.

At the same time, the resolution also signaled something else: Singapore’s willingness to cooperate across borders and impose significant penalties on its own corporate champions. The fine was enormous. But the alternative—being perceived as soft on corruption—would have been far more corrosive to the country’s long-term standing.

For CEO Loh Chin Hua, the timing could not have been worse. Keppel was already reeling from the oil-price collapse. Now its most important division wasn’t just economically exposed—it was under a cloud that struck at trust. The scandal didn’t merely add stress to the offshore and marine business; it strengthened the emerging conclusion that this legacy engine was becoming an existential liability.

Keppel now had a narrowing window to prove it could be something else—before the old Keppel pulled the entire organisation under with it.

VII. Vision 2030: The Great Reinvention (2020–Present)

If the oil crash forced Keppel to question its business model, and the Petrobras scandal forced it to question trust, the next chapter was about identity. And it starts with the person who had been quietly preparing for a different kind of Keppel all along.

Loh Chin Hua was appointed Chief Executive Officer in January 2014, after serving two years as Chief Financial Officer. But he wasn’t a shipyard lifer who’d spent his career around dry docks and welding torches. Loh joined Keppel in 2002 and founded Keppel Fund Management, the Group’s private fund management arm, and ran it for a decade. Before Keppel, he was Managing Director at Prudential Investment Inc, leading its Asian real estate fund management business. And he began his career at the Government of Singapore Investment Corporation (GIC), with roles across its Singapore, San Francisco, and London offices.

That background mattered, because it shaped the diagnosis. Loh didn’t see Keppel’s problem as “we need better rigs.” He saw it as: this company had world-class operating capabilities, but too much of its fate was chained to a volatile project cycle. The way out wasn’t just operational excellence. It was a different economic engine—one built on managing capital, recycling assets, and earning recurring fees.

So Loh initiated a strategic review with the board and a bench of future leaders. Three options emerged: keep the status quo, become a pure engineering firm, or pivot toward asset management. Keppel chose the pivot—but with a twist. It wouldn’t abandon its DNA as a builder and operator. It would use that operating credibility as an advantage in becoming an asset manager.

That became Vision 2030.

Keppel announced Vision 2030 as the roadmap for its long-term strategy and transformation. The pitch was straightforward but radical for an old-school conglomerate: refocus the portfolio into an integrated business that could provide end-to-end solutions for sustainable urbanisation, with an asset management arm to fund growth and create a platform for capital recycling. The Group would build on its strengths in engineering, developing and operating specialised assets, and capital and asset management—then concentrate around four areas: energy and environment, urban development, connectivity, and asset management.

The work started before the announcement. In the first half of 2019, about 30 younger leaders from across business units were tasked with imagining what Keppel could become, factoring in both emerging trends and what the Group could credibly execute. Their ideas were distilled into a multi-year plan—less a rebrand, more a rewrite of the company’s operating system.

But one move mattered more than any slide deck: Keppel had to let go of the business that had made it famous.

On 28 February 2023, Sembcorp Marine completed its acquisition of Keppel Corporation’s Offshore & Marine division for $3.34 billion. Two months later, on 27 April 2023, Sembcorp Marine’s shareholders approved a name change to Seatrium.

For Keppel, this wasn’t just a divestment. It was a break from decades of commodity exposure. The world’s largest rig builder—the unit that had powered Keppel’s rise, then amplified its vulnerability—was now someone else’s story. And Keppel could finally commit, fully, to the new one.

On 1 January 2024, Keppel Corporation was renamed Keppel Ltd., following the completion of its restructuring into a global asset manager and operator, organised under four business platforms: Infrastructure, Real Estate, Connectivity, and Fund Management & Investment.

Then Keppel pushed the next phase of Vision 2030: a further transformation from conglomerate into a global alternative real asset manager, with deep operating capabilities. The ambition was explicit—scale assets under management to S$200 billion by 2030, with an interim target of S$100 billion by end-2026.

And this wasn’t only organic growth. Keppel used acquisitions to accelerate the shift. On 29 April 2024, it completed the acquisition of an initial 50% stake in Aermont Capital, a European real estate firm ranked top by PERE. The logic was clear: Aermont gave Keppel a foothold in Europe, expanding beyond its Asia-Pacific base—and it immediately showed up in the scale of the platform, with funds under management rising to about S$80 billion from S$55 billion at end-December 2023.

Financially, the new Keppel started to look less like a cyclical contractor and more like a capital platform. Keppel reported net profit of $1.06 billion from continuing operations, a 5% increase from the prior year, and generated a free cash inflow of $901 million. Asset management fees jumped 54% to $436 million, while funds under management expanded from $55 billion to $88 billion.

The trend continued into 2025. Keppel Ltd. reported net profit of $431 million for the first half of 2025, up 25% from $345 million in 1H 2024, excluding the Non-Core Portfolio for Divestment. Annualised return on equity reached 15.4% in 1H 2025, up from 13.2% a year earlier. Funds under management grew to $91 billion at end-June 2025.

The transformation also changed what “shareholder returns” looked like. Keppel declared an interim cash dividend of 15.0 cents per share and announced a $500 million Share Buyback Programme.

Internally, the shift was cultural as much as strategic. “We started to work together across divisions, which was not natural for Keppel, being so siloed,” Loh said. “Then we privatized our subsidiaries to bring everything under one roof. It allowed us to deploy capital more strategically and manage our talent across the group. Finally, in 2023, we completed the integration.” By January 2024, Keppel was operating as one integrated firm.

VIII. Understanding the New Keppel: Business Model Deep Dive

The “New Keppel” is built to do what the old conglomerate struggled to do: produce steady, repeatable earnings. Instead of relying on huge, lumpy project wins, Keppel now runs three integrated platforms designed around recurring income.

Infrastructure Platform

This is where Keppel’s engineering DNA shows up—just not in the old way. The segment has moved from being primarily an EPC player in waste and water infrastructure to offering technology solutions plus operating and maintenance services that keep revenue flowing long after the build is done.

What used to be a relatively small, mostly Singapore-focused infrastructure business has expanded into markets including China, India, Thailand, and Vietnam. The pitch is decarbonisation and sustainability at scale, increasingly powered by tools like AI and machine learning. By end-2024, the segment had around $6 billion in long-term, non-power-related contracts, expected to generate more than $100 million in annual EBITDA from 2025.

Connectivity Platform

Here’s a perfect example of Keppel’s new playbook: recycle capital, keep the strategic capability. Keppel expected to receive close to S$1.0 billion in cash proceeds for its 83.9% effective stake in M1, while retaining M1’s fast-growing ICT business. That ICT arm fits neatly with Keppel’s broader connectivity stack—data centres and subsea cables—without tying up as much capital in the traditional telco business. The divestment was positioned as part of Keppel’s shift toward being an asset-light global asset manager and operator, sharpening the Connectivity segment around digital infrastructure.

And digital infrastructure, for Keppel, increasingly means data centres. Demand has been accelerating with the rise of artificial intelligence and generative AI, pushing the market toward bigger, more power-hungry, and more energy-efficient facilities. Keppel has been in this business for two decades, designing, developing, and operating data centres. With a portfolio of 35 data centres across Asia Pacific and Europe, and gross power capacity of 650 MW, Keppel has been scaling up to capture what it sees as a major real asset growth opportunity.

Real Estate Platform

Keppel Land remains a cornerstone—positioned as the world’s second most sustainable diversified real estate developer. Its portfolio spans residential developments, investment-grade commercial properties, and integrated townships, with a focus on China, Singapore, and Vietnam.

One flagship example is the Sino-Singapore Tianjin Eco-City, a planned city jointly developed by the governments of Singapore and China. It’s also a reminder that even in the “New Keppel,” the company still likes problems that are big enough to require long timelines, deep partnerships, and real operating execution.

Fund Management & Investment

This is the glue—and the economic engine that turns Keppel from an operator into a platform. The Aermont acquisition expanded Keppel’s funds under management by S$24 billion post-acquisition, with additional upside from co-creating new fund products. It also broadened Keppel’s network of blue-chip limited partners through Aermont’s longstanding relationships with more than 50 global clients.

From there, the plan was twofold: keep Aermont’s real estate platform performing, and work jointly to build new products and initiatives—drawing on Keppel’s experience in alternative assets like private credit funds and data centres. With Keppel’s support, Aermont was described as having the potential to grow its FUM by up to 2.5x to around S$60 billion by 2030.

You can see the shift showing up directly in the numbers. Recurring income—profits from asset management and operations—made up more than 80% of Keppel’s 1Q 2025 net profit, excluding the legacy O&M assets.

IX. Strategic Analysis: Porter's 5 Forces & Hamilton's 7 Powers

Porter's Five Forces Analysis

Threat of New Entrants (MODERATE-LOW): Keppel plays in businesses where the entry ticket is expensive. Data centres, infrastructure projects, and real estate development all require massive upfront capital, long timelines, and the ability to execute without blowing up budgets. In Singapore, regulatory constraints add another layer of protection. And Temasek’s presence as a major shareholder creates a kind of institutional credibility and access that’s hard to match. The caveat: global private equity giants like Blackstone and Brookfield are increasingly targeting the same alternative real assets across Asia, and they bring fundraising scale Keppel has to contend with.

Bargaining Power of Suppliers (LOW-MODERATE): Keppel isn’t hostage to a single critical supplier. It sources construction, engineering, and equipment globally, and it can shift as pricing and availability change. On the technology side, partnerships help reduce dependence—like its strategic framework agreement with Amazon Web Services for subsea cables—so the stack isn’t built around one vendor’s choke point.

Bargaining Power of Buyers (MODERATE): Keppel’s customers and counterparties often have options. Institutional investors can choose other managers for alternative asset exposure. Property buyers and tenants can compare developers. Governments and utilities can run competitive tenders. But Keppel does have a real differentiator: it can originate, build, and operate assets, not just buy them—and that operator credibility can matter when buyers care about delivery and uptime, not just pitch decks. In infrastructure especially, long-term contracts also reduce churn once Keppel is in.

Threat of Substitutes (MODERATE-HIGH): If you’re an investor allocating capital, substitutes are everywhere: REITs, private equity funds, and other yield vehicles compete for the same dollars. In Singapore and the region, other government-linked companies such as Sembcorp and CapitaLand also overlap in pieces of the playing field. And globally, the biggest asset managers are moving into Asian markets with deep benches and strong fundraising momentum.

Competitive Rivalry (MODERATE): Singapore’s brand of state capitalism often means competition among GLCs is less cutthroat than in fully fragmented markets. But zoom out beyond Singapore and rivalry ramps up quickly—especially in hot sectors like data centres and renewables, where global players are scaling aggressively and the best sites and partners get bid up fast.

Hamilton's 7 Powers Analysis

Scale Economies (Moderate): In fund management, scale matters. A larger FUM base lets a platform spread fixed costs, invest in teams and systems, and win larger mandates. In Keppel’s operating businesses, scale helps, but it’s not the same flywheel—execution still tends to be asset-by-asset and project-by-project.

Network Effects (Limited): There are pockets of network effects—telecom has them by nature, and data centres benefit from ecosystem gravity—but none are so strong that they become a winner-take-most dynamic for Keppel.

Counter-Positioning (Strong): This is the standout. Keppel did something many legacy conglomerates struggle to do: it let go of the business that defined it. Exiting O&M was painful and identity-shaking—which is exactly why it’s hard for others to copy. At the same time, many pure-play asset managers can raise capital, but they don’t have Keppel’s depth in operating and developing assets. Keppel sits in the uncomfortable middle, and that “middle” can be a moat.

Switching Costs (Moderate): Infrastructure concessions and long-term contracts tend to lock in relationships over years. Real estate tenants don’t move lightly. And in fund management, LP relationships are sticky too—allocators are often reluctant to switch away from managers they’ve backed through multiple cycles.

Branding (Strong in Singapore): Keppel’s name carries weight at home. Decades as a flagship company—with the implied expectations of governance, reliability, and delivery—create trust with partners and institutional investors, especially across Asia where reputation and track record can matter as much as returns.

Cornered Resource: Keppel benefits from relationships and position in Singapore, where access—whether to partnerships, talent, or opportunities—can be a real advantage. Temasek’s roughly 20% stake also provides patient capital and institutional backing that most competitors can’t replicate.

Process Power (Emerging): The “New Keppel” is trying to turn integration into an edge: fund management, investment discipline, and operating execution under one roof. If it works, it becomes a repeatable process—raise capital, build or acquire assets, operate them well, recycle capital, and do it again. The key word is emerging: this power strengthens only if Keppel keeps executing as the model matures.

X. Playbook: Business & Investing Lessons

The Singapore Model

Keppel is a clean case study in how government-linked companies try to balance two jobs at once: behave like a hard-nosed commercial operator, while still serving national priorities. The model works when the state provides patient capital and strategic direction without trying to run the business day to day. Done well, it creates real advantages—credibility, access to capital, and a longer time horizon than most public markets allow. But it also comes with constraints, from reduced flexibility to the permanent glare of public perception.

When to Kill Your Darlings

Keppel’s decision to exit offshore and marine is what strategic discipline looks like in real life. For more than 50 years, the shipyard wasn’t just a business line—it was Keppel’s identity, the engine that funded so much of what came after. But once the downturn proved structural, management didn’t pretend it would all bounce back with the next oil cycle. They made the toughest call a legacy industrial champion can make: a clean break.

"Unlike most asset managers, we are also very strong operators," Loh said. "As a result, investors see us as quite a different animal compared with a typical general partner."

Capital Light vs. Capital Heavy

The reinvention from an asset-heavy conglomerate into a fee-generating asset manager goes straight at Keppel’s old weakness. Capital-intensive businesses demand constant reinvestment, and they amplify whatever cycle you’re tied to—especially commodities. Asset-light models aim for the opposite: recurring income from managing and operating assets, with capital recycled rather than trapped.

Scandal Response

The Petrobras settlement was a gut punch—but it also showed how institutional credibility can survive a serious crisis when the response is decisive. Keppel cooperated with authorities, paid the US$422 million penalty, strengthened compliance, and moved forward. It didn’t erase the damage, but it did draw a line under it.

Energy Transition as Business Model

Keppel’s pivot—from building oil rigs to developing renewable and sustainability-linked infrastructure—puts it on the right side of a structural shift. Instead of treating the energy transition as a threat to defend against, it reframed it as the next growth market to build for.

"We'd been very successful as a conglomerate for many decades, but the market was changing," Loh explained. "Our recurring income was low, and we were not attracting the kind of growth multiples that we wanted to see. To add insult to injury, the market was further penalising us through a conglomerate discount."

XI. Bull Case vs. Bear Case

Bull Case

The bull case is that Keppel’s new, asset-light model does what it’s designed to do: lift returns while smoothing out the violent swings that used to come with big, one-off project cycles. The early proof point is profitability quality. Annualised return on equity reached 15.4% in the first half of 2025, up from 13.2% a year earlier—momentum that supports the idea that Vision 2030 isn’t just an aspiration, it’s a trajectory.

Then there’s the tailwind Keppel can’t manufacture but can absolutely surf: digitalisation. Data centres and connectivity infrastructure are becoming the new “ports and pipelines” of the global economy, and demand is being supercharged by AI. As Keppel has put it, cloud players and hyperscalers are now investing in massive data centre campuses, driven by the intensive computing requirements of AI—and that acceleration is pushing energy consumption at data centres sharply higher.

Layer on the Singapore Inc. advantage. Temasek’s presence provides credibility, capital access, and a kind of institutional staying power—especially in Asia, where trust and long-term partnership matter as much as price. Keppel’s home-base positioning in high-growth Asian markets can also create angles that Western competitors can’t replicate easily.

And finally, there’s the scale ambition. Keppel has set the goal of reaching $200 billion in funds under management by 2030, pursuing both organic growth and acquisitions. It’s backing that push with substantial dry powder and a large deal flow pipeline—fuel for the flywheel if it can keep originating, operating, and recycling assets at pace.

Bear Case

The bear case is less about whether the strategy makes sense, and more about whether it can be executed without friction and value leakage.

Keppel has identified a portfolio of non-core assets for divestment, with a carrying value of $14.4 billion as at 30 June 2025. Many of these assets are profitable, but they no longer fit the asset-light, recurring-income model. Turning them into cash—at acceptable prices, on a sensible timeline, without distracting management or weakening the core engine—is a complicated balancing act. Asset monetisation is easy to say and hard to do well.

Competition is another pressure point. Global alternative asset managers like Blackstone and Brookfield are building bigger Asian footprints and will compete directly with Keppel for both LP capital and high-quality deals. Even if Keppel has operating credibility, it’s still fighting in a world where fundraising scale and brand can overwhelm nuance.

Real estate also brings macro risk. Exposure to China creates near-term headwinds as the property market correction weighs on sentiment and valuations. Even if Keppel’s exposure is manageable, the broader environment can still depress outcomes.

And then there’s the slow grind that hits every asset manager eventually: fee compression. As the industry matures, fees come under pressure. That means Keppel has to keep scaling funds under management just to protect the same fee pool—and any stumble shows up quickly.

Key Performance Indicators to Track

For investors following Keppel, two metrics matter most:

-

Funds Under Management growth trajectory — The road from about S$91 billion at end-June 2025 to S$200 billion by 2030 is the clearest scoreboard for the strategy. It captures organic fundraising and inorganic growth from deals like Aermont.

-

Recurring income as percentage of total profit — When this stays high, it confirms Keppel is actually becoming what it says it is: a steadier, higher-quality earnings platform. If the ratio starts slipping, it’s a warning sign that the transformation is losing momentum.

XII. Epilogue: What the Transformation Reveals

Keppel’s story is, at its core, a story about adaptation—about a company that refused to let what it was determine what it could become.

It began with a harbour a British naval captain spotted while hunting pirates. It became a shipyard that had to be repurposed when the British withdrew. It grew into the world’s largest oil rig builder. And then, after the oil cycle broke and scandal scarred the brand, it chose to rebuild itself into a global asset manager and operator. Each reinvention demanded leaders willing to make calls that were emotionally hard and economically risky—and stakeholders willing to tolerate short-term pain for a different long-term future.

That change wasn’t just strategic; it was cultural. “We started to work together across divisions, which was not natural for Keppel, being so siloed,” Loh said. “Then we privatized our subsidiaries to bring everything under one roof. It allowed us to deploy capital more strategically and manage our talent across the group.”

And while this is a very Singapore story—with Temasek, national champions, and the particular logic of Singapore Inc.—the takeaway travels. As climate change, digitalisation, and geopolitics reshape the global economy, more companies are going to face the same fork in the road: defend the model that made you successful, or change it before the world changes it for you.

Keppel chose change, and it wasn’t cosmetic. It exited the business that built the group’s identity, sold down assets, and rewired itself around recurring income and capital recycling—the logic of an asset manager, not a project contractor.

“You just have to believe that if you keep doing the right things and you keep moving the chains, as they say in American football, then eventually you will get there and the market will change,” Loh said.

Of course, the ending isn’t written yet. The S$200 billion FUM target for 2030 is still a big reach. Legacy assets still need to be monetised without value leakage. The European platform built through Aermont still has to prove itself through returns, not rankings. And the data centre bet has to translate AI-driven demand into durable, investable cash flows.

But the direction is clear—and, so far, the execution has matched the narrative. For anyone watching Singapore Inc., or simply trying to understand what modern corporate reinvention actually looks like, Keppel is a case study in transformation as strategy, not just crisis response.

Captain Henry Keppel’s harbour is still there. Only now it’s framed by luxury condominiums instead of shipyards. The name stayed. The purpose changed. And that may be the most Keppel lesson of all: in business, as in harbours, relevance belongs to the organisations that can be rebuilt for whatever the next tide brings.

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music