APA Group: The Invisible Giant Powering Australia's Energy Future

I. Introduction & Episode Roadmap

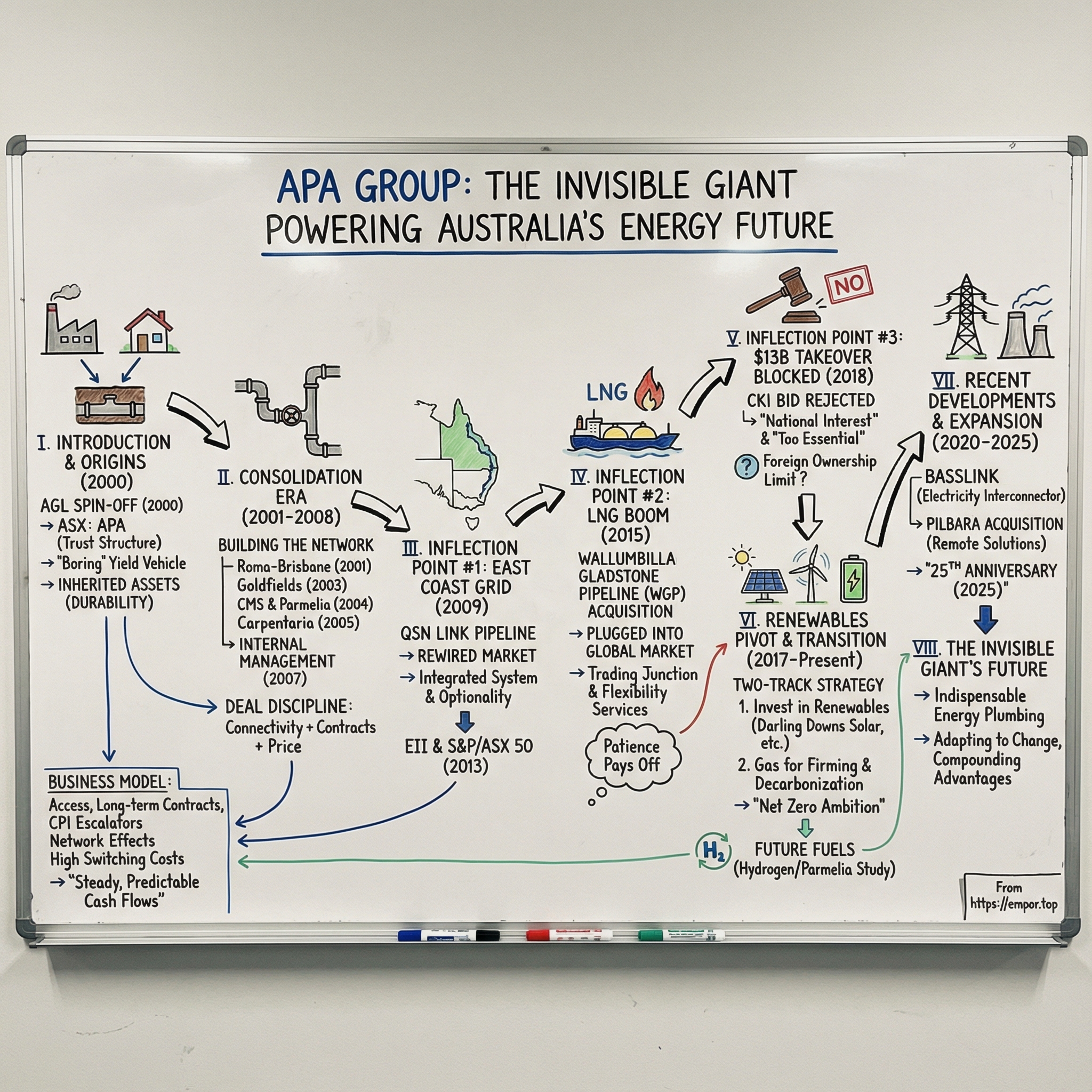

Picture this: every time a factory in Brisbane fires up its furnaces, every time a family in Adelaide turns on the stove, and every time an LNG tanker leaves Gladstone bound for Asia, there’s a company pushing molecules through a steel network buried beneath Australia—and most Australians have never heard its name.

That company is APA Group. It transports around half of Australia’s domestic gas supply. And in an era when energy security and the climate transition dominate the headlines, APA sits one layer upstream from the political noise: out of sight, out of mind, but absolutely in the loop of what makes the country function. Take its network away and power stations don’t get fuel, industrial users can’t run, and the energy system starts failing in very real, very expensive ways.

APA oversees a portfolio of energy infrastructure assets valued at roughly $27 billion. This isn’t just “some pipelines.” It’s gas transmission, gas distribution, electricity transmission, power generation, and a growing set of renewables like solar and wind. If you’re looking for the connective tissue of Australia’s energy economy, you’re looking at APA.

The scale is hard to overstate. APA’s network spans about 15,000 kilometres of gas transmission pipelines—effectively a continent-wide circulatory system. It connects gas basins to cities and heavy industry, links Queensland’s coal seam gas fields to export terminals at Gladstone, and moves supply from places like the Cooper Basin to demand centres like Melbourne and Sydney. Once those links exist, they don’t just move gas. They reshape markets.

So here’s the question that drives the whole story: how did a plain-sounding trust, spun out of a utility in 2000, turn into Australia’s largest energy infrastructure company—and a linchpin of national energy security?

The answer is a mix of disciplined dealmaking, compounding network effects, and a regulatory framework that, for better and worse, can function like a moat. It’s also a story that culminates in a very modern kind of plot twist: the moment a major foreign buyer tried to acquire APA, and Australia’s government said no—not because APA was flashy, but because it had become too essential.

Along the way, a few themes keep showing up: the “tollbooth” model where customers often pay whether or not they use the capacity; regulation as both protector and constraint; the tightrope walk of staying indispensable to the current system while positioning for the next one; and the meaning of being “too important to be foreign-owned.”

If you want the simplest mental model, think of APA like Australia’s biggest toll road operator—except the traffic is invisible, the road is underground, and the tolls are written into contracts that run for decades. It’s infrastructure investing at its purest: quiet, steady, and enormously valuable. Now let’s trace how it got built.

II. The Origins: AGL's Spin-Off & Birth of a Pipeline Giant

It was 2000. The dot-com bubble was in full bloom, but in the far less glamorous world of utilities, a different kind of change was underway. Around the world, vertically integrated energy companies were being pulled apart—generation here, retail there, networks somewhere else—because investors and regulators increasingly wanted to see exactly where risk lived.

In Australia, that shift set up a pivotal decision by the Australian Gas Light Company, AGL. In June 2000, AGL floated its gas transmission assets into a new vehicle called Australian Pipeline Trust and listed it on the Australian Securities Exchange. The ASX code for the securities was APA. That ticker would become the name.

The logic was straightforward and powerful. Pipeline networks—especially the regulated ones—tend to behave like financial utilities: steady, contract-backed cash flows with far less volatility than retail energy. Split the pipes away from the retail business and you give each side a cleaner story. AGL could crystallize value for shareholders, and the new pipeline entity could raise capital without competing internally against the priorities of the parent.

But the structure mattered as much as the strategy. AGL didn’t spin these assets into a conventional company. It created a trust. That choice wasn’t cosmetic; it was the foundation for how APA would be valued and who would own it. Listed on the ASX, the trust’s ownership spread across public investors—and because of the trust structure’s tax efficiency, cash distributions could flow through without the same double-layer taxation typical of a standard corporation.

That feature helped cement APA’s identity early: not a flashy growth stock, but a yield vehicle. The pitch was basically, “This is essential infrastructure. It throws off predictable cash. We’ll give most of it back to you.” And that kind of promise attracts a specific audience—income-focused investors who like their returns boring and dependable.

At birth, APA wasn’t starting from scratch. It came into the world with a serious set of transmission assets—pipes built over decades, with routes, easements, compressor stations, and the hard-won approvals that come with them. In infrastructure, that history is the advantage. Replicating those assets later isn’t just expensive; it’s often politically and practically impossible.

That’s the deeper point behind why this spin-off worked. Infrastructure value isn’t only about growth. It’s about durability—assets that keep doing their job year after year, backed by contracts and regulation, with replacement costs that quietly rise out of reach for would-be competitors. These were pipelines laid in an earlier era, before today’s inflation, permitting complexity, and organized community opposition made new builds slower and harder.

So yes, APA’s formal history begins in June 2000, on the day it listed. But its real roots run much deeper—into Australia’s industrial build-out, when connecting gas basins to cities was national development, not just capital expenditure.

From day one, APA was positioned as an income story: maintain the assets, honor the contracts, distribute the cash. What nobody could fully see yet was how quickly that “boring” foundation would turn into a platform—one that could consolidate the country’s gas arteries into something far bigger, far more connected, and far more important than a simple trust had any right to become.

III. The Consolidation Era: Building the Network (2001–2008)

After listing, APA didn’t try to reinvent itself. It did something far more effective: it started assembling a system.

Management understood a core truth about pipeline economics: a pipeline on its own is an asset. A pipeline that plugs into other pipelines is a network. And networks don’t just earn money—they create leverage. Every new connection increases routing options for customers, improves reliability, and makes the whole grid more valuable than the individual pieces.

So APA went to work, deal by deal.

In 2001, it acquired the remaining interest in the Roma to Brisbane Pipeline, taking full ownership of a key Queensland artery. Two years later, in 2003, it increased its stake in the Goldfields Gas Transmission Pipeline—an important line in Western Australia, feeding energy into a mining economy that was powering up fast.

Full ownership of Roma to Brisbane mattered for a simple reason: shared control slows everything down. With one owner making the calls, expansion decisions, investment timing, and operational priorities all got cleaner. Goldfields, meanwhile, wasn’t just another asset—it was a foothold in a region where energy demand rose with every new mine and processing facility.

Then came a bigger step west.

In 2004, APA expanded its Western Australian presence by purchasing CMS Energy Corporation’s interest in the Goldfields Gas Transmission and Parmelia natural gas pipeline assets. It was a classic infrastructure moment: a seller with problems elsewhere, and a buyer with patient capital and a single-minded focus. CMS, an American investor in Australian gas infrastructure through the 1990s, was under pressure from challenges in the rest of its portfolio. APA was built for exactly this kind of opportunity—when good assets come available for reasons that have little to do with the assets themselves.

In 2005, APA kept tightening the network. It acquired the remaining 30% interest in the Carpentaria Gas Pipeline in Queensland, strengthening its position in the state and continuing the quiet march toward control and coherence.

By now, the pattern was clear. APA wasn’t buying pipelines for the sake of owning more steel in the ground. It was buying connectivity. Each purchase made the existing footprint more useful to shippers and harder to replicate for competitors.

The real identity shift arrived in late 2006 and 2007.

Over that period, APA acquired the Allgas Energy distribution business and GasNet Australia, expanding its presence in gas distribution and transmission. It also acquired the Directlink electricity interconnector—an early sign that APA was willing to widen the aperture beyond gas when the asset fit the broader “essential infrastructure” model. And crucially, APA transitioned to an internal management and operations model, taking direct control of how the business was run.

That internalisation move was more than a governance tweak. When APA was spun out from AGL, it used an external management model—common for infrastructure trusts, but often a ceiling on performance. External managers can be paid on assets under management, which can skew incentives toward growing the portfolio rather than optimising it. Bringing management in-house aligned accountability with owners, tightened cost control, and built the operational capability to run complex projects, not just collect cash flows.

With that capability in place, APA pushed into development and expansion too. It commenced construction of the Bonaparte Gas Pipeline in the Northern Territory and expanded capacity across several existing pipelines from late 2007. Then in 2008, it kept building breadth: acquiring a stake in the SEA Gas Pipeline and an investment in Envestra Limited, along with the associated asset management business.

The Envestra investment, in particular, set up something bigger down the line. Envestra operated gas distribution networks serving millions of consumers across South Australia, Victoria, Queensland, and parts of New South Wales. APA started with a minority stake, but it was the kind of toehold that could compound—an entrée into regulated distribution, long-dated customers, and a platform that would become increasingly important over the following decade.

By 2008—eight years after the spin-off—APA had changed shape. It was no longer just a passive owner of inherited pipes. It was building what it explicitly described as an “integrated gas transmission network”: a connected system with a strategic logic, operational muscle, and a growing presence across regions and asset types.

And underneath all the deal headlines was a consistent discipline. The questions stayed the same: Does this asset connect to what we already own? Are the contracts long-term and backed by credible counterparties? Does the price make sense relative to the asset base and the likely returns? That kind of filter is what kept APA from drifting into expensive empire-building—and it set the stage for the next leap, when the company wouldn’t just own pieces of the map. It would start knitting Australia’s gas markets together.

IV. Inflection Point #1: Creating the East Coast Gas Grid (2009)

On May 11, 2009, APA cut the ribbon on a project that did something rare in infrastructure: it didn’t just add capacity, it rewired a market. In a ceremony attended by South Australian Minister for Transport, Infrastructure and Energy Patrick Conlon, APA officially opened the QSN Link Pipeline—tying Queensland into the gas transmission networks of New South Wales and South Australia, and effectively creating an integrated eastern Australian gas market for the first time.

To appreciate why this mattered, you have to remember what “the market” looked like before the link existed. The east coast wasn’t one system. It was a handful of regional systems sitting side by side.

Queensland gas from the Surat and Bowen Basins mostly served Queensland. Cooper Basin gas flowed south toward Adelaide or east toward Sydney. Victoria’s Gippsland supply largely stayed in Victoria. Price gaps could linger for long stretches, not because anyone was playing games, but because there simply wasn’t a physical route to move gas from where it was cheap to where it was expensive.

The QSN Link—about 283 kilometres of steel and compressor-driven reality—changed that. It gave the eastern states a new set of routing options and a new kind of flexibility. Supply could shift. Demand centres could tap more than one basin. And suddenly, “energy security” wasn’t just a policy term; it was a function of plumbing.

The commercial consequences followed the physics. Producers in Queensland gained a pathway to customers further south. Buyers in Adelaide could look at different sources and choose the best option available, rather than being boxed into whatever their local system could deliver. Physical integration enabled commercial integration, and commercial integration made the system more resilient.

For APA, it was even bigger than that. This is the moment its portfolio started behaving like a true network.

Before, pipelines were largely point-to-point businesses: a shipper contracted for a specific route on a specific asset. After QSN Link, each additional connection made the entire grid more valuable. More supply points and more demand points meant more combinations, more optionality, and more reasons for customers to keep coming back to the same operator. The story shifted from “owning a pipe” to “owning access.”

That same year, APA also created Energy Infrastructure Investments (EII), an unlisted investment vehicle to hold some assets. It was a strategic financial move that did a few things at once: it kept the listed entity focused on core infrastructure, it freed up capital for the next phase of growth, and it opened the door for outside institutional money to take minority positions in mature assets—without APA having to give up strategic control.

Then the compounding continued.

In 2011, APA added the Amadeus Gas Pipeline in the Northern Territory and stepped into renewables with the Emu Downs Wind Farm in Western Australia. And in 2013, APA joined the S&P/ASX 50 Index—an inflection point of a different kind. It meant passive funds now had to own the stock. More importantly, it was a public signal that the pipeline trust born in 2000 had graduated into Australia’s corporate top tier.

The company’s ambition was becoming clearer too: not just an east coast grid, but interconnected systems that could scale toward something national. APA later announced the Northern Goldfields Interconnect—eventually planned to span 580 kilometres—linking the Perth Basin with the Goldfields region and pushing Western Australia in the direction of the same connected-grid logic that had worked on the east coast.

This is what “network effects” look like in pipeline land. Not viral growth, not social graphs—just a brutal, elegant reality: the more nodes you connect, the more valuable the whole system becomes to everyone using it. And unlike software platforms, this kind of network is protected by an even stronger moat than code or brand.

You can’t stream molecules through the ether.

V. Inflection Point #2: The LNG Boom & Wallumbilla Gladstone (2015)

If QSN Link stitched the east coast together, the LNG boom plugged that system into the world.

In the 2010s, Queensland’s coal seam gas fields went from a local supply story to a global export machine. Three massive projects—Queensland Curtis LNG, Australia Pacific LNG, and Gladstone LNG—poured more than $60 billion into taking gas out of the ground, supercooling it into liquid, and shipping it to Asia.

For APA, this was the kind of moment infrastructure companies live for. Demand was exploding, and moving gas from inland Queensland to the coast meant pipelines.

But it was also the kind of moment infrastructure companies fear. The LNG developers weren’t sleepy utilities. They were oil-and-gas heavyweights—BG Group, ConocoPhillips, Santos, Origin—who could fund, permit, and build their own pipes if they didn’t like the terms on offer. If APA missed the window, the east coast could end up with parallel, competing systems—and in pipeline economics, duplication is how returns get crushed.

APA’s play was simple, and in hindsight, brutal: don’t fight the majors while they’re building. Wait for the moment when the asset is finished, de-risked, and the owner wants to recycle capital.

That moment arrived with the pipeline that would become one of APA’s defining assets: the Wallumbilla Gladstone Pipeline, or WGP. It was originally built for Queensland Curtis LNG and was known as the Queensland Curtis LNG Pipeline. Construction finished in 2014. It was owned by QGC, and then in 2015 it was sold to APA Group. (Formally, it’s a non-scheme pipeline under Part 23 of the National Gas Rules.)

On 3 June 2015, APA announced it had completed the acquisition from BG Group of the QCLNG Pipeline—its largest ever pipeline acquisition at the time.

“We are very pleased to have completed this acquisition which extends the footprint of our east coast gas grid to over 7,500 km across eastern Australia and represents APA’s largest ever pipeline acquisition,” APA Managing Director Mick McCormack said.

Physically, WGP is big: a 543-kilometre line running from Wallumbilla down to Gladstone, connecting gas fields in Queensland’s Surat Basin—and APA’s broader East Coast Grid—to the Queensland Curtis LNG export facility on Curtis Island.

Strategically, it was even bigger. WGP wasn’t just another line on the map. It was the spine that connected Australia’s domestic gas network to the global LNG market. Queensland gas now had a direct highway to an export terminal. And once export capacity exists, it changes everything: domestic buyers aren’t only competing with the factory down the road anymore—they’re competing with global demand, mediated through the economics of liquefaction, shipping, and netbacks.

Zoom out, and you can see the market re-forming around this new reality. The east coast gas market became a more interconnected grid linking multiple basins to major demand centres, offering shippers far more supply options. But those once-in-a-generation LNG investments, combined with the rise of coal seam gas in Queensland, also changed how shippers wanted to use the pipes. The old patterns didn’t hold. That shift, in turn, drove a new round of transmission investment to meet the market where it was going.

And at the center of that web sat Wallumbilla.

What had been a rural Queensland town became, in effect, a physical trading junction—multiple major pipelines converging in one place, including the Roma Brisbane Pipeline, the South West Queensland Pipeline, and now WGP. With that concentration came a new kind of behavior: shippers could swap molecules, reroute volumes, and optimize portfolios in ways that just weren’t possible when the system was fragmented.

APA leaned into it. It wasn’t enough anymore to simply transport gas from A to B. The value was increasingly in enabling flexibility. APA developed services that helped make trading work in practice: mechanisms for in-pipe trades, using virtual delivery and receipt points, and capacity trading services that allowed firm operational pipeline capacity to be traded between parties.

In other words, APA started to look less like a pure transporter, and more like the operator of the marketplace’s plumbing—still earning infrastructure-style returns, but now sitting at the control points where optionality lived.

The financial impact mattered, too. APA said it expected WGP to contribute around $355 million in EBITDA in its first full year. For a business that had been generating EBITDA not that far below a billion dollars, one transaction moved the needle in a way few infrastructure deals ever do.

But the real takeaway wasn’t the size. It was what the deal proved about APA’s model.

It showed patience—letting the majors take construction risk and waiting for the right entry point. It showed capital discipline—buying when a motivated seller wanted out, not when everyone was breathless at peak optimism. And it showed integration advantage—because once APA owned the pipe, it could immediately fold it into an existing grid, making the whole network more valuable than the standalone asset ever was.

That combination—network, regulation, contracts, and timing—is what made APA so hard to dislodge. And it’s why, a few years later, when an outsider tried to buy the whole company, it wouldn’t be treated like just another takeover.

VI. Inflection Point #3: The $13 Billion Takeover That Wasn't (2018)

Every so often, you learn what a company really is—not from its annual report, but from who tries to buy it, and what the government does about it.

In 2018, APA got that kind of clarity delivered to its doorstep. Cheung Kong Infrastructure, the infrastructure arm of Hong Kong’s Li Ka-shing empire, launched a roughly $13 billion bid for the company.

On its face, it looked like a familiar play: a global infrastructure buyer going after long-lived, contract-backed assets in a stable country. And CKI wasn’t some first-time tourist in Australia. The Li family’s investment vehicles already held big positions across Australian electricity networks, gas distribution, and other essential infrastructure. CKI had won approval for its $7.4 billion takeover of DUET in 2017. Earlier, in 2014, it had cleared the acquisition of gas distributor Envestra—now Australian Gas Networks.

But APA was different. Buying APA wouldn’t just expand a portfolio. It would effectively put one foreign group in control of a huge share of Australia’s gas transmission backbone.

The process played out like a lesson in how Australian dealmaking really works. First, competition law.

In September 2018, the ACCC gave competition clearance after accepting an enforceable undertaking from CKI to divest certain pipelines and a gas storage facility in Western Australia if the transaction went ahead. In other words: from the ACCC’s perspective, with a bit of asset surgery, the deal could pass the “does this substantially lessen competition?” test.

Then came the harder gate: foreign investment approval.

The Foreign Investment Review Board, which advises the Treasurer on whether a deal is in the national interest, did not reach a unanimous view. It raised concerns that the acquisition could place a majority of Australian pipelines under the control of a single foreign company.

And ultimately, Treasurer Josh Frydenberg said no.

His stated reason was blunt: the transaction would result in “a single foreign company group having sole ownership and control over Australia’s most significant gas transmission business.”

That kind of intervention is exceedingly rare. Rejections of foreign takeover bids hardly ever happen; this was only the sixth in nearly two decades. Australia generally welcomes foreign capital—especially in sectors like resources and infrastructure—because it often depends on it. Blocking a bid from a commercially oriented, experienced infrastructure investor sent a message that went beyond this one transaction.

It also forced everyone to say the quiet part out loud about APA’s scale. APA was the largest oil and gas transmission business in Australia, controlling about 56% of the country’s pipelines—and its system included roughly three-quarters of the pipes in New South Wales and Victoria.

In that light, the decision seemed to have less to do with CKI being Hong Kong-based and more to do with a simple reality: APA had become too central to how Australia moves energy around. The takeover attempt turned APA from “a toll road for gas” into something closer to “a piece of national plumbing you don’t let go of.”

There was politics in it too. Forces within the Liberal Party that had opposed Malcolm Turnbull’s leadership were deeply hostile to the sale. By 2018, energy had become one of Australia’s most combustible political topics—prices, reliability, export debates, the whole lot. Approving foreign ownership of the dominant pipeline operator would have been an easy target.

For APA shareholders, the aftermath was awkward. The stock had risen on the bid premium, then fell back when the deal was blocked. But the underlying business hadn’t deteriorated. If anything, the episode publicly confirmed what APA’s strategy had been building toward for nearly two decades: a position so embedded in Australia’s energy system that it had become, quite literally, a national interest question.

VII. The Renewables Pivot & Energy Transition (2017–Present)

Long-dated infrastructure has a particular kind of risk: not that the assets stop working, but that the world stops needing them. For a pipeline company, that risk has a name: the energy transition. As electricity gets cleaner and the economy electrifies, you can’t just assume gas demand will look the same in 10, 20, or 30 years.

APA’s answer has been a two-track strategy. First, start building real exposure to renewables. Second, make the case that gas—far from disappearing overnight—still plays a critical role in keeping the system stable.

From 2017, APA accelerated its investment in renewable energy, acquiring the Darling Downs Solar Farm, developing the Badgingarra Wind Farm, and opening the Emu Downs Solar Farm.

One of the clearest signals was Darling Downs. Queensland Premier Annastacia Palaszczuk officially opened APA Group’s Darling Downs Solar Farm, one of Australia’s largest at the time. The project cost $200 million, was supported by a $20 million grant from ARENA, and spread more than 423,000 solar panels across 250 hectares—enough generation, APA said, to power around 36,000 homes.

But the important nuance is what these projects were and weren’t. They were meaningful, visible, and directionally important. They were not a wholesale reinvention of the company. Even a large solar farm was still only a slice of APA’s broader asset base. The message was essentially: we’re participating in the transition, and we’re learning by doing—but we’re not wagering the entire enterprise on a single, sudden pivot.

The bigger move was strategic positioning: APA leaned hard into the idea of gas as a transition enabler, not a transition casualty. The company emphasized the importance of gas for firming capacity.

The “firming” argument is simple and increasingly hard to ignore. Wind and solar are cheaper and cleaner, but they are intermittent. When the sun sets or the weather doesn’t cooperate, the grid still needs supply that can be dispatched quickly. Batteries help, especially over short durations, but long gaps and extended weather events demand something else. Gas-fired generation can start fast and ramp up and down flexibly, which makes it a natural partner for renewables.

In that framing, the transition doesn’t eliminate the need for pipelines. It can pull on them in new ways. Gas demand for firming capacity has been forecast to increase, and gas has been credited with preventing outages during a recent heatwave in Victoria.

That’s the counterintuitive part: as coal-fired power stations retire—pushed out by age, economics, and policy—the grid often leans more heavily on gas to cover the gaps. And more gas-fired generation still needs gas delivered reliably, at scale, on demand. That’s APA’s home turf.

APA has been unusually direct about the trade-off this creates, acknowledging that supporting the system can increase the company’s own emissions footprint even while it enables broader decarbonization:

"We recognise that this necessary investment will likely result in emissions growth for APA, however, the economy-wide emissions reduction this is expected to deliver must be prioritised."

It’s a candid line, and it gets to the tension at the heart of APA’s story in this era. Building gas infrastructure and supporting gas-powered generation can look like moving in the wrong direction—especially to ESG-focused investors—yet APA’s argument is that it’s part of how Australia actually gets from coal to renewables without sacrificing reliability.

At the same time, APA has been looking for the next set of assets that can sit alongside pipelines in a decarbonizing economy. The company has targeted opportunities in remote grid power generation, electricity transmission, and future fuels like hydrogen.

Hydrogen is the most speculative of the lot, but it’s also the one with the most upside if it works—because it has the potential to turn “gas infrastructure” from a stranded-asset worry into a zero-carbon advantage. APA and Wesfarmers Chemicals Energy and Fertilisers (WesCEF) published key results from the Parmelia Green Hydrogen Project Feasibility Study, looking at producing and transporting renewable hydrogen to WesCEF’s ammonia production facilities at the Kwinana Industrial Area south of Perth, using APA’s existing Parmelia Gas Pipeline.

In 2023, the Parmelia Gas Pipeline Hydrogen Conversion Technical Feasibility Study went a step further, testing the pipeline material in a gaseous hydrogen environment. The testing indicated it was technically feasible, safe, and efficient to operate the southern section of the pipeline at current operating pressure using 100 per cent hydrogen.

If that holds up at scale, the implication is enormous: the pipes don’t have to become relics. They can become routes for “zero-carbon molecules,” helping decarbonize industrial processes where electrification is difficult—things like ammonia production and other heavy industry.

All of this sits under a longer-dated commitment that signals direction without locking APA into a single path. The company has stated:

At APA, we're taking on Australia's energy transition and pursuing our pathway to achieve net zero operational (Scope 1 and Scope 2) emissions by 2050. As part of our role in the energy transition, we are working towards a Scope 3 net zero ambition.

It’s a target calibrated to the reality of infrastructure: long lives, long contracts, and long investment cycles. It gives APA room to keep doing what the system needs today—moving gas and supporting reliability—while building options for what the system might need tomorrow.

VIII. Recent Developments & Expansion (2020–2025)

From 2020 onward, APA stayed true to the playbook that built the company—buy and build assets that are hard to replicate, then plug them into a wider system—but with a noticeable shift in emphasis. The next decade wasn’t just about moving more gas. It was about widening the definition of “energy infrastructure” without losing the steady, contract-and-regulation-backed economics that made APA what it is.

In 2020, APA announced the Northern Goldfields Interconnect: a 580-kilometre pipeline intended to link the Perth Basin with the Goldfields region and help form an interconnected Western Australian gas grid.

Conceptually, it was QSN Link’s western cousin. The same integration logic—more connection points, more routing options, more resilience—applied on the other side of the country. Once built, gas from the Perth Basin’s emerging production could flow to the Goldfields’ mining load, pulling Western Australia toward a more unified, flexible gas market.

Then came a move that made the company’s “beyond pipelines” ambitions impossible to miss.

On 20 October 2022, APA announced it had completed the acquisition of Basslink for A$773 million.

Basslink was APA’s biggest step into electricity transmission: a 370-kilometre interconnector running from George Town in Tasmania, across Bass Strait, to Gippsland, where it connects into Victoria’s grid at Loy Yang.

The strategic appeal wasn’t just the asset itself, but what it enabled. Tasmania, with its hydro resources, has long pushed the idea of becoming the “Battery of the Nation”—using hydro reservoirs (including pumped hydro) to store energy and send dispatchable renewable power to the mainland. But that vision only works if you have the cord that connects the island to the rest of the system. Basslink is that cord.

The path to “infrastructure-style” returns, though, wasn’t instantaneous. APA expected Basslink to operate as a regulated asset from July 2026. In the lead-up, APA planned to trade Basslink on the electricity spot market from 1 July 2025, after the Basslink–Hydro Tasmania contract expired on 30 June 2025.

That regulatory conversion process captured both the risk and the opportunity in APA’s model. APA bought Basslink after its previous owners had driven it into administration—distressed infrastructure, but strategically vital. APA committed to pursuing regulated status as part of the transaction. After an initially unfavorable draft decision, the Australian Energy Regulator ultimately approved the conversion, validating the thesis and setting Basslink up for more predictable, regulated returns.

While Basslink signaled the electric future, APA also made one of its largest-ever bets on remote, industrial Australia.

APA entered into a Share Sale Agreement with Alinta Power Cat Pty Ltd and Alinta Energy Development Pty Ltd to acquire 100% of Alinta Energy Pilbara Holdings Pty Ltd and Alinta Energy (Newman Storage) Pty Ltd (Alinta Energy Pilbara) for an Enterprise Value of A$1,722 million.

Completed in late 2023, the Alinta Energy Pilbara acquisition was APA’s biggest deal since the Wallumbilla Gladstone Pipeline. APA expected it to be free cash flow per security accretive in its first full financial year of ownership and value accretive. It came with long-term Power Purchase Agreements with some of Australia’s most significant resources companies, plus a pipeline of projects aimed at bringing new renewable energy solutions to market—explicitly aligned with APA’s Climate Transition Plan.

The portfolio included 543 MW of operating generation and storage assets and more than 82 MW of solar and battery projects under construction. Key assets included the 60 MW Chichester Solar Farm, the 178 MW gas- and diesel-fired Newman Power Station with an associated 35 MW battery, and the 210 MW gas-fired Port Hedland power station.

As APA put it: “We believe this acquisition gives us the scale and capability to be the leading provider of bundled energy infrastructure solutions for the remote regions of Australia. We estimate the total market opportunity and investment in electricity generation infrastructure required to decarbonise the Pilbara to be about $15 billion.”

By June 13, 2025, APA had enough history—and enough transformation behind it—to mark a milestone: its 25th anniversary as a listed entity on the Australian Securities Exchange.

A quarter-century after the spin-off, APA had evolved from a collection of inherited pipeline assets into Australia’s largest energy infrastructure company—spanning gas transmission, electricity interconnection, power generation (gas, solar, and wind), and battery storage. The diversification helped answer the stranded-asset question investors naturally ask about gas, while keeping the underlying engine intact: essential networks, hard-to-replicate assets, and cash flows shaped by contracts and regulation.

IX. The Business Model Deep Dive: Why Pipelines Print Cash

To understand APA, you have to understand a specific kind of business: one where the product is access, the customers sign up for years, and the cash shows up with almost metronomic consistency.

In APA’s Energy Infrastructure segment, most revenue doesn’t depend on whether gas volumes are booming or slumping. In the first half, about 87% of revenue came from either take-or-pay contracts or regulated revenue. Only a small slice came from shorter-term, more flexible services and other volume-linked items.

Take-or-pay is the core mechanic. Under these contracts, customers—gas producers, LNG exporters, power generators, big industrial users—reserve pipeline capacity and commit to paying for it whether they use it or not. Ship less than you reserved? You still pay. That structure pushes volume risk onto the customer and gives the pipeline owner something close to the holy grail in business: predictable revenue.

Layer in how the pricing works, and the picture gets even better. The majority of APA’s revenue is either regulated or contracted with CPI-linked escalators and take-or-pay terms. Translation: high visibility, low volume exposure, and built-in inflation protection.

Those CPI escalators matter more than most people appreciate. When consumer prices rise, APA’s tariffs typically rise with them. In an inflationary environment, that means a business that already looks stable can also look like it’s growing—without needing to sell more capacity or build anything new.

There’s also a subtle distinction between regulated assets and unregulated contracted capacity. Pipeline capacity sold on long-term take-or-pay contracts can earn a return about one to two percentage points higher than regulated contracts, to compensate for demand risk once those contracts roll off. The risk is that, when a contract expires, the owner needs to re-contract the capacity. The premium exists because recontracting isn’t guaranteed. For APA, with its scale, network reach, and deep shipper relationships, the risk of losing demand is typically lower than it would be for a standalone pipeline—so that premium can feel like mostly upside.

This is why APA can talk about revenue certainty in a way most companies simply can’t. Over FY20–21e, APA said it had certainty over more than 90% of group revenue because term capacity reservation contracts and regulated revenue caps protected it from volume risk. The breakdown was heavily skewed toward long-term take-or-pay capacity contracts, with additional support from regulated revenue caps and fixed revenue contracts. The punchline: only a small minority of revenue was meaningfully exposed to volume swings.

Structurally, APA is also designed to appeal to investors who like steady distributions. It operates with a stapled security structure, is internally managed, and has direct operational control over its assets—an important detail in infrastructure, because owning the asset is one thing, but running it well for decades is where value compounds.

The market’s view of APA reflects all of this. A five-year monthly beta of around 0.35 is exceptionally low. In plain English, APA tends to trade more like a bond proxy than a typical equity: it usually falls less in market sell-offs, and it often lags in euphoric rallies. It’s not built for adrenaline; it’s built for durability.

That same story shows up in the yield. A forward dividend yield around 6% signals what investors are really buying: contract-backed, inflation-linked cash flows that management has historically been willing to return to shareholders.

And the recent numbers show the machine doing what it’s supposed to do. For the half-year ending 31 December 2024 (1H25), APA reported higher earnings versus 1H24, driven by strong contributions from the Pilbara Energy System business, higher variable revenue, inflation-linked tariff escalations, and cost growth below inflation. Underlying EBITDA rose to $1,015 million, supported by new assets, stronger seasonal demand for gas transmission capacity, tariff increases linked to inflation, and tighter cost control.

This is the model, fully visible: inflation escalators lift revenue, acquisitions add cash, and disciplined operations protect margins. It’s not flashy. It’s effective. And it’s why, for a quarter-century, APA has been able to keep turning buried steel and long-term contracts into real, bankable cash.

X. Porter's Five Forces & Hamilton's 7 Powers Analysis

Frameworks won’t tell you everything, but they do force you to be honest about what’s doing the real work in a business. In APA’s case, Porter's Five Forces explain why the industry stays calm and profitable. Hamilton's 7 Powers explain why APA, specifically, has been able to compound inside that industry for so long.

Porter's Five Forces

Threat of New Entrants: Very Low

If you want to compete with APA, you don’t start by writing software. You start by raising billions of dollars, then spending years in approvals, environmental assessments, and landholder negotiations—before you lay a single metre of pipe. And even if you do all that, you’re competing against infrastructure that was built decades ago, often at dramatically lower costs.

APA is also already the dominant player: it’s the largest oil and gas transmission business in Australia, controlling about 56 per cent of Australia’s pipelines. And pipelines have a brutal kind of first-mover advantage. Once a corridor exists and shippers are connected, building a parallel route is usually uneconomic and politically painful. The bar for “new entrant” isn’t just high. It’s close to vertical.

Bargaining Power of Suppliers: Low

APA owns and operates its infrastructure, and most of what it buys is available from multiple global suppliers: steel pipe, compressors, valves, and construction services. None of those vendors have the kind of unique leverage you see in industries with proprietary inputs. Labour is specialised, but it still doesn’t dictate terms to the owner of essential, long-lived assets.

Bargaining Power of Buyers: Low to Moderate

APA’s customers are big and sophisticated: LNG exporters, miners, power generators, and industrial users. On paper, that sounds like buyer power.

But the contract structure flips the equation. In the first half, about 87% of revenue in the Energy Infrastructure segment came from take-or-pay contracts or regulated revenue. Take-or-pay means customers commit to paying for reserved capacity whether they use it or not, which reduces APA’s volume risk and limits buyer leverage during the contract term.

The “moderate” part shows up at renewal time. Large LNG and mining counterparties can negotiate hard when contracts roll over. Still, their ultimate leverage is constrained by physics: there’s usually only one practical pipeline route connecting a facility to supply basins and markets, and switching is often not a real option.

Threat of Substitutes: Moderate and Evolving

The long-term substitute threat is electrification. If industrial heat, manufacturing processes, and firming capacity move away from gas, pipeline throughput can decline.

But the transition is not a straight line. Gas demand for firming capacity has been forecast to increase, and gas has been credited with helping prevent outages during a recent heatwave in Victoria. In the medium term, substitution pressure is partially offset by gas’s role as the flexible backup for intermittent renewables—especially as coal retires faster than replacement firming capacity arrives.

Industry Rivalry: Low

Australian pipeline markets are mostly regional monopolies or duopolies. There aren’t many players, the assets are immovable, and regulated returns remove much of the incentive to start price wars. Competitors tend to operate in their lanes, focusing on long-term contracts, reliability, and incremental expansions rather than aggressive poaching.

Hamilton's 7 Powers Framework

1. Scale Economies: Strong

Pipelines have massive fixed costs and tiny marginal costs. Once the steel is in the ground, moving extra gas through it costs very little. APA’s network spans about 15,000 kilometres across Australia, which lets it spread operating expertise, systems, and overhead across an asset base smaller operators simply can’t match.

2. Network Effects: Strong

APA’s advantage isn’t just that it owns pipelines. It’s that many of those pipelines connect to each other.

The east coast gas market is now served by a grid of interconnected pipelines linking numerous basins to demand centres, which creates multiple supply options and routing choices. Every new connection increases the value of the whole system: more receipt points, more delivery points, more flexibility, and more reasons for shippers to prefer the network that gives them options.

3. Counter-Positioning: Moderate

APA has been able to take a stance that’s difficult for many traditional utilities: stay essential to today’s energy system, while investing into tomorrow’s.

Because the core gas business throws off durable, contract-backed cash flows, APA can fund investments in solar, wind, batteries, electricity transmission, and hydrogen without having to bet the company on an all-at-once reinvention. That positioning doesn’t remove transition risk, but it does soften it—and it’s a strategic posture that not every incumbent can credibly adopt.

4. Switching Costs: Very Strong

With pipelines, switching costs aren’t a loyalty program. They’re concrete and steel.

Customer facilities are physically connected into specific infrastructure, and the engineering work to connect somewhere else is expensive and slow. Layer on 15- to 20-year contracts, plus the operational complexity of interconnection, and “switching” becomes a theoretical option more than a practical one—even when contracts expire.

5. Branding: Weak

APA doesn’t need consumer mindshare. This is business-to-business infrastructure. What matters is trust with regulators, government, and large counterparties—reputation and relationships, not branding in the classic sense.

6. Cornered Resource: Moderate to Strong

Pipeline corridors and easements are finite, and increasingly difficult to secure. APA controls about 56 per cent of Australia’s pipelines, which isn’t just market share—it’s control of routes that are hard to replicate. As right-of-way approvals become more challenging amid community opposition and environmental constraints, the value of existing corridors compounds.

7. Process Power: Moderate

APA’s shift to internal management and operations wasn’t just a corporate structure change; it built capability. Over roughly twenty-five years, APA has accumulated institutional knowledge about gas flows, customer operations, technical integrity, and regulatory navigation. That learning curve is long, and it doesn’t transfer easily to a newcomer.

XI. Risks & Bear Case vs. Bull Case

Bear Case

The bear case for APA starts with the simplest threat to any pipeline operator: a world that needs fewer molecules.

If electrification accelerates faster than expected—helped along by cheaper batteries, better heat pumps, and falling renewable costs—then parts of industrial gas demand could shrink structurally. In that world, pipelines that look indispensable today risk becoming overbuilt tomorrow. And “overbuilt” is just a polite way of saying stranded.

APA itself has been unusually candid about the tension at the heart of its strategy:

"We recognise that this necessary investment will likely result in emissions growth for APA, however, the economy-wide emissions reduction this is expected to deliver must be prioritised."

That line is both defensible and uncomfortable. APA’s near-term growth case leans on investing in gas infrastructure and gas-powered generation to keep the system reliable. But those same investments can expand its operational emissions footprint. For ESG-focused investors, that can be disqualifying—regardless of whether gas enables broader decarbonisation by replacing coal and firming renewables.

Then there’s the risk that sits beneath every “regulated moat” story: regulation can giveth, and regulation can taketh away. Access pricing reviews could compress returns. Governments focused on affordability could intervene to limit tariff increases. And the more essential APA becomes, the more political attention it attracts—especially when energy prices are already a national obsession.

Balance sheet risk matters too. Infrastructure businesses typically run with more leverage than “normal” companies because their cash flows are contract-backed and long-lived. But leverage cuts both ways. If interest rates stay high for longer, higher funding costs can tighten credit metrics and squeeze interest coverage. In that kind of environment, an equity raise—dilutive and painful—moves from “unthinkable” to “possible.”

Finally, there’s the very specific recontracting risk embedded in APA’s biggest single profit engine. The Wallumbilla Gladstone Pipeline’s long-term contract runs for 20 years, and from 2035 onward that contract will be finished. At that point, the economics depend on what happens next: whether the customer still needs the capacity, whether the pipeline is still strategically critical in a changing market, and what the new terms look like if the parties renew.

More broadly, contract roll-offs come in waves. When major agreements expire, big shippers can seek better pricing, shift volumes, or restructure their portfolios in ways that reduce what they reserve. For APA, the recontracting cycle—especially around Wallumbilla Gladstone—will be one of the clearest real-world tests of just how durable its network advantage is.

Bull Case

The bull case begins where APA has always been strongest: energy security.

As coal plants retire and renewable penetration grows, the grid needs firming—supply that can respond quickly when the sun sets or the wind drops. Gas has been credited with helping prevent outages during a recent heatwave in Victoria, and demand for gas-powered firming capacity has been forecast to increase. If that plays out, APA’s pipes stay central, because you can’t run gas peakers without reliable delivery.

Then there’s industry. For many industrial processes, gas isn’t a preference—it’s a requirement. High-temperature process heat remains difficult and expensive to electrify at scale. For those customers, demand is more structural than cyclical, and that underpins long-term throughput on the transmission network.

The upside wildcard is future fuels—especially hydrogen. APA and Wesfarmers Chemicals Energy and Fertilisers (WesCEF) have been exploring the Parmelia Green Hydrogen Project, where green hydrogen would be produced from water using renewable energy and electrolysis, and then transported to help decarbonise WesCEF’s ammonia facility.

If hydrogen economics work—and if pipelines can be converted as feasibility work suggests—APA’s network could shift from “gas legacy infrastructure” to “zero-carbon molecule highway.” That’s a very different narrative, and it carries asymmetric payoff potential: limited downside if hydrogen stays niche, and substantial upside if hydrogen scales and existing corridors become the easiest path to market.

And then there’s the Pilbara. APA has planted a flag in one of the most energy-hungry, infrastructure-intensive regions of the country, and it’s been explicit about the size of the opportunity:

"We estimate the total market opportunity and investment in electricity generation infrastructure required to decarbonise the Pilbara to be about $15 billion."

Mining companies are making decarbonisation commitments and need practical partners to deliver generation, storage, and transmission in remote environments. With its Pilbara platform, APA is positioned to become that partner—and to grow in electricity infrastructure even as the long-term shape of gas demand evolves.

Key Performance Indicators to Monitor

For investors tracking APA’s trajectory, three indicators are especially telling:

-

Take-or-Pay and Regulated Revenue as Percentage of Total Revenue: This is the heartbeat of earnings quality. The higher the share, the more predictable cash flows tend to be. If it declines, APA is taking on more volume exposure and more competitive risk.

-

Weighted Average Contract Tenor: This measures how far into the future APA can “see” its revenue base. Longer tenors mean higher visibility. Shortening tenors can be an early warning sign that recontracting risk is approaching.

-

EBITDA Margin: APA is operationally leveraged, so margins should stay stable or improve with disciplined cost control and inflation-linked tariffs. Margin compression can signal cost inflation outpacing escalation, tougher contract negotiations, or operational inefficiency.

XII. Conclusion: The Invisible Giant's Future

Twenty-five years after AGL spun it out, APA Group had become something that’s hard to overstate: a critical piece of Australia’s energy plumbing. What began as a trust holding a set of pipeline assets turned, through patient acquisitions and a steady hand on capital allocation, into a roughly $27 billion portfolio that now stretches beyond gas into electricity interconnection, power generation, and renewables.

The deeper lesson is that APA’s advantages weren’t built in a single deal. They compounded.

The more APA connected, the more valuable the network became. Customers didn’t just buy a pipe; they bought access—options, routing flexibility, and reliability. Once a major customer is physically tied into a network and locked into long contracts, switching is expensive, slow, and often impractical. And because pipelines are high fixed-cost assets, scale matters: the operator with the biggest footprint can spread expertise and overhead the widest, and run the system with a kind of efficiency smaller players can’t easily replicate. Over all of it sits regulation—sometimes a constraint, often a shield—setting predictable returns and raising the barrier for new competition to enter.

But the future isn’t a straight-line extrapolation from the past. APA’s core uncertainty is the same one facing every long-life infrastructure owner: what if the world changes faster than your assets can?

The energy transition will happen; the question is timing. Gas could remain essential for decades as the fast-start partner to wind and solar, or demand could fall faster than expected as electrification accelerates. Hydrogen could turn parts of APA’s network into a genuine zero-carbon corridor, or it could stay technically feasible but economically niche. And industrial demand could prove stubbornly durable—or finally crack as alternatives scale.

What isn’t ambiguous is APA’s importance right now. When households cook dinner, when industry needs high-heat energy, and when LNG leaves Gladstone for Asia, APA’s infrastructure is in the chain—quietly doing the job, earning contract-backed revenue, and sitting at the junction between energy policy and energy reality.

In a country obsessed with electricity prices and reliability, APA has spent a quarter-century becoming indispensable without becoming famous. The invisible giant may not ever be a household name. But it’s already part of the household’s energy system—and that’s the point.

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music