ALS Limited: From Soap to Science — The Making of a Global Testing Empire

I. Introduction & Episode Roadmap

Picture Brisbane in 1863. It’s still more frontier town than city—humid, fast-growing, and full of people arriving with big plans. Scottish immigrants are stepping off ships looking for opportunity in colonial Queensland. Some chase wool. Some chase gold.

Peter Morrison Campbell brings something much less romantic, and much more useful: he knows how to make soap.

That modest start became Campbell Brothers, a soap manufacturer based at Kangaroo Point. And over the next 160 years, that soap business would pull off a transformation that, in hindsight, feels almost impossible: it would become ALS—one of the world’s most important, and least flashy, scientific testing empires.

Today, ALS provides testing, inspection, certification, and verification services from more than 370 sites across 65 countries. It employs around 22,000 people and generates over $3 billion in annual revenue. In minerals testing, it’s a global reference point—the lab network mining companies rely on to validate what’s in the ground, whether that’s in Vancouver, Peru, or Western Australia. And over the last decade-plus, ALS has deliberately built a second engine: life sciences testing across environmental monitoring, food safety, and pharmaceuticals.

So here’s the question that makes the whole story click: what does it take to pivot a 160-year-old company not once, but twice—and come out the other side as a global leader in a fragmented, brutally competitive industry?

The answer is part vision and part timing. It’s disciplined capital allocation. It’s a willingness to buy rather than build when speed matters. And it’s something harder to measure: the courage to shed an identity that once defined you, because the world moved on.

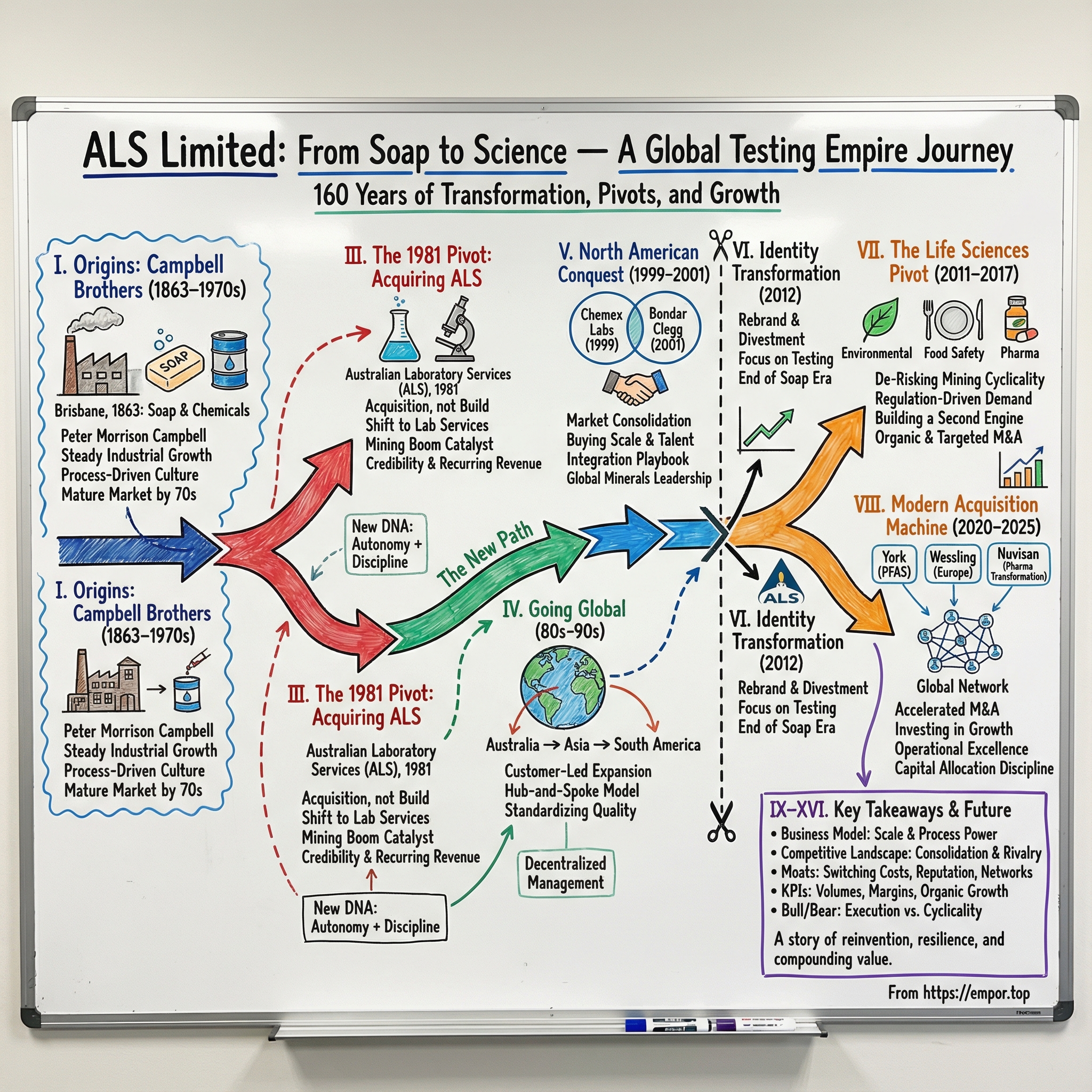

We’re going to tell this in three acts. Act one is a century of soap and steady industrial operations—important not because it’s glamorous, but because it explains the company’s cultural roots. Act two begins in 1981, with a single acquisition that flips the business from manufacturing into laboratory services. Act three is the modern era: ALS diversifies away from the boom-and-bust cycle of mining into the regulation-driven stability of life sciences. Along the way, there are audacious North American deals, a name change that signals a clean break, and the building of real moats in a business that, at first glance, can look like a commodity.

If you’re evaluating ALS today, the last four decades are the key. But if you want to understand how ALS became ALS—why it could reinvent itself when so many old companies can’t—you have to start with a bar of soap in 1863 Brisbane.

II. Origins: Campbell Brothers & the Soap Era (1863–1970s)

Colonial Queensland in the 1860s was a place being built in real time. Brisbane had only just become a municipality. The wool industry was pushing inland. Mining discoveries were creating sudden fortunes. And as more free settlers arrived, the frontier started demanding the everyday basics of “civilized” life.

One of those basics was soap.

In 1863, Peter Morrison Campbell established a soap-making business in Queensland. The operation set up at Kangaroo Point, a working bend of the Brisbane River already filling up with small industrial enterprises. Soap was a practical bet. In a pastoral economy you had plenty of animal fats. Add caustic soda and manufacturing know-how, and you could produce something every household and business needed. Demand was rising, local supply was limited, and the market wasn’t going away.

By 1881, the business moved to Bowen Hills—bigger premises for a bigger operation—and it would stay there for the next century. Campbell Brothers produced soaps and cleaning chemicals year after year, growing steadily alongside Queensland’s economy. This wasn’t a company built on hype or sudden breakthroughs. It was the kind of business you ran by getting the basics right, every day, for decades.

In 1952, Campbell Brothers was publicly floated and listed on the local stock exchange as Campbell Brothers Limited. Post-war Australia was industrializing fast, and public capital gave manufacturers room to expand. But even as it became a listed company, Campbell Brothers was still, at heart, what it had always been: a domestic cleaning-products manufacturer.

The real importance of this era isn’t the product line. It’s what the work demanded. Soap and chemical manufacturing is unforgiving: formulations need to be exact, batches need to be consistent, and quality control can’t be optional. Over time, that builds a certain operating temperament—process-driven, detail-oriented, and allergic to sloppiness. Long before anyone at Campbell Brothers imagined ore assays or environmental sampling, the company was already learning how to run a precision business.

By the 1970s, though, the limits were starting to show. The Australian soap and cleaning chemicals market wasn’t a great growth story. Competition was rising, the category was mature, and the business—while steady—wasn’t pointing toward the kind of future that excites public markets.

Campbell Brothers didn’t have a crisis yet. But it did have a problem: a solid industrial company with nowhere particularly interesting to go next. And that’s exactly the moment, in many long-lived corporate stories, when the pivot either happens—or never does.

III. The 1981 Pivot: Campbell Brothers Acquires Australian Laboratory Services

In 1981, Campbell Brothers stopped being a soap company with a respectable past and started becoming something else entirely. Not overnight, and not with a flashy rebrand—but with a single, very deliberate move: buying into a small Brisbane laboratory with a plain name and a very modern kind of customer.

Australian Laboratory Services Pty Ltd had only been founded a few years earlier. ALS commenced laboratory testing operations in Brisbane as “Australian Laboratory Services” in 1976 as a privately owned company. It initially provided analytical services to the oil shale and mineral exploration industries and, in its first decade, grew steadily—because the market around it was exploding.

The 1970s were a surge era for Australian mineral exploration, driven by global commodity demand and new discoveries. And after the 1973 OPEC oil embargo, oil shale drew real investment interest too. Whether you were hunting for minerals or trying to make unconventional energy pencil out, you had the same problem: you needed independent, credible analysis of what was actually in your samples. Australian Laboratory Services existed to answer that question—accurately, repeatedly, and fast.

In 1981, Campbell Brothers acquired a controlling stake in Australian Laboratory Services, then purchased the remaining shares by the mid-1980s. That pacing mattered. It wasn’t just a financial structure; it was a way to get close to a business that looked nothing like a factory line—learn it, understand the economics and the culture, and only then commit to full ownership.

Because this wasn’t simply diversification. It was a bet on a different kind of company.

So why would a soap manufacturer do this at all? The answer starts with what laboratory testing really is.

It sits downstream of powerful, long-running industries. If mining and energy activity expands, testing expands with it. And unlike mature consumer categories—where growth is incremental and competition is relentless—testing demand is pulled by project pipelines, exploration programs, and development work that can scale quickly.

It also behaves like recurring revenue in disguise. Mining companies don’t run a single test and walk away. They test through exploration, feasibility, development, and production. Once a lab has proven itself—on accuracy, turnaround time, and trust—relationships tend to stick across sites and across years.

And then there’s the moat: credibility. In theory, anyone can buy instruments and hire technicians. In practice, laboratories live and die by accreditation, validated methodologies, and track record. When a client is making decisions that can swing enormous capital commitments, “good enough” isn’t good enough.

This is why ALS often describes 1981 as the start of its modern era. After listing on the Australian Stock exchange in 1952, the modern era of the company began in 1981 with the acquisition of Australian Laboratory Services Pty Ltd and a shift to becoming a highly regarded international testing, inspection and certification company.

Irrespective of our size, we have always retained a uniqueness that has allowed us to truly understand the industry, encouraging innovation and an entrepreneurial spirit that creates strong links between our global business operations.

That line reads like corporate messaging—until you see why it mattered. Laboratory services win on technical excellence, speed, and client relationships. And those are built locally, close to customers, by teams that can make decisions without waiting for headquarters. The management approach Campbell Brothers developed through this transition—leaning into autonomy, while protecting quality—became the template for everything that came next.

Because once you’ve successfully pulled off a pivot this big, you unlock a new capability: the confidence to keep moving. The global expansion, the North American deals, and the later shift into Life Sciences all trace back to this moment—when a century-old soap maker proved it could buy, learn, and integrate a business built on science, trust, and execution.

IV. Going Global: The Australia-Asia-Americas Expansion (1980s–1990s)

Once Campbell Brothers had fully absorbed Australian Laboratory Services, the next question was unavoidable: was this going to be a good Australian lab business… or the start of something global?

They chose global. Not in a single leap, but in a methodical march that matched how the mining industry itself moves.

The pattern is clear in hindsight. After rapid growth and diversification across Australia in the 1980s, ALS expanded into Asia and South America in the 1990s. Then came North America, Africa, and Europe in the early 2000s, and finally the Middle East in 2011.

This wasn’t expansion for expansion’s sake. It was customer-led geography. Mineral exploration doesn’t spread evenly across a map; it clusters where geology, regulation, and capital line up. In the ’80s and ’90s, that meant places like Indonesia and Southeast Asia, and the Andean mining belt in South America—regions where new projects were being funded and every serious operator needed trustworthy assays. ALS followed the exploration money, because that’s where the samples—and the long-term relationships—would be.

To do it without burning capital, ALS leaned into a hub-and-spoke model. The company built full-service “hub” laboratories in major mining regions, then supported them with smaller satellite sites focused on collection and sample preparation. Remote sites could move material into the hubs efficiently; the hubs could run sophisticated analysis at scale. It was a practical way to be close to customers without duplicating expensive capability everywhere.

And none of this was easy in the pre-internet era. It’s hard to overstate how operationally intense “global labs” were before modern connectivity and logistics. Quality control meant standardizing methodologies across teams working in wildly different conditions. Chain-of-custody had to hold up across borders and customs regimes. And clients didn’t just want results—they wanted confidence that an assay in one country would mean the same thing as an assay in another. ALS invested in systems and training so that the work stayed consistent, regardless of where it was performed.

With over 75 laboratories and offices, and employing 6500 staff in key mining provinces and trade ports on six continents, ALS Minerals provides unparalleled global coverage for a dynamic industry that seeks consistency, reliability, quality, mobility, versatility and technical leadership from service providers.

What made that possible culturally was how ALS managed the expansion. Instead of running everything from a distant headquarters, the company empowered local managers to win clients, adapt to local conditions, and move quickly. That decentralization created real speed and flexibility—but it only worked because ALS paired it with an uncompromising focus on standards and discipline. In testing, your reputation is the product.

By the late 1990s, Campbell Brothers no longer looked anything like a domestic soap manufacturer with a side business in labs. It had built a real international footprint in minerals testing—and it had set the stage for the deals that would turn “meaningful participant” into global heavyweight.

V. The North American Conquest: Chemex Labs & Bondar Clegg (1999–2001)

By the late 1990s, ALS had done the hard part: it had proven an Australian lab network could follow mining customers across borders and keep quality consistent. Now came the part that would define the company’s global standing for the next two decades—North America.

The acquisitions of Chemex Labs in 1999 and Bondar Clegg in 2001 were the second major inflection point in ALS’s corporate history. Together, they turned ALS from a fast-growing international operator into one of the world’s largest providers of laboratory analysis services to the minerals industry.

ALS reached that scale by buying two North American mineral laboratory groups in quick succession: Chemex Labs in December 1999, and Bondar Clegg in December 2001.

To understand why that mattered, you have to understand what was happening in the market. Global mining companies were consolidating, bulking up, and operating across more countries than ever. As they did, they started demanding the same thing from service providers: consistent quality, consistent turnaround times, and the ability to support multi-country operations without reinventing the wheel in every jurisdiction. Meanwhile, minerals testing was still largely a patchwork of strong regional labs. It was an industry practically begging to be rolled up. The only open question was who would do the rolling—and who would be left behind.

Chemex Labs had real heft. Founded in North Vancouver, British Columbia in 1966 by Bruce Brown, it grew into a significant North American testing provider with operations across Canada, the United States, and Mexico. Campbell Brothers acquired Chemex in 1999 and folded it into ALS—instantly giving the group deeper credibility and density in North America.

Then came Bondar Clegg.

William Bondar and Malcolm Clegg started their business in 1962 under the name “Exploration Services,” running a mobile geochemical laboratory in New Brunswick. Three years later they opened geochemical and assay laboratories in Ottawa, under the name Bondar-Clegg and Company Ltd. It’s the kind of origin story that fits the industry: practical, field-driven, built around going where the rocks are.

By the time ALS acquired it, Bondar Clegg had become a major international operation—with laboratories across the Americas, including Canada, the USA, Mexico, Ecuador, Peru, Brazil, Bolivia, Chile, and Argentina. That footprint was strategic gold. It covered the key mining corridors in the Western Hemisphere and brought with it decades of expertise and customer relationships.

ALS’s approach to integration was telling. It wasn’t about gutting the acquired businesses; it was about combining scale with continuity. Overlapping facilities, such as those in Vancouver, were slated to be merged. And according to a Chemex statement, the majority of the management and client service staff from both Bondar Clegg and ALS Chemex would retain their jobs. In a reputation business, that’s not soft-heartedness—it’s strategy. You don’t buy a lab network just for equipment; you buy technical credibility and trust, person by person, client by client.

This integration playbook—consolidate where there’s duplication, keep the expertise and customer-facing teams, standardize quality and methods—became a template ALS would reuse for years. The combined organization could spread fixed costs over more volume and invest in technology and methodologies that smaller labs struggled to afford.

The significance of these deals went well beyond the immediate expansion of sites. Almost overnight, ALS gained access to North American mining customers, a major operating presence in Latin America, and world-class technical talent that had been built over decades. From that point on, ALS could credibly claim global leadership in minerals testing—and, just as importantly, it could defend that claim.

And it didn’t come out of nowhere. The company’s growth trajectory had already been compounding for years: it began geochemical services in Queensland, Australia in 1974, and by the end of 1995 the minerals division had 14 laboratories across Australia, New Zealand, and South East Asia. The 1996 acquisition of Geolab SA added another six laboratories in Chile, Argentina, and Peru. Chemex and Bondar Clegg weren’t a detour—they were the culmination of a decade-long march toward scale.

For anyone looking at ALS today, this is the moment that built its modern minerals moat. Not just because the company got bigger, but because it proved it could do the hardest thing in services M&A: buy great businesses, integrate operations without breaking quality, retain the people clients actually trust, and come out stronger on the other side.

VI. The Name Change & Identity Transformation (2012)

In August 2012, Campbell Brothers Limited officially became ALS Limited. On paper, it looked like a tidy piece of corporate housekeeping. In reality, it was the company making a public, irreversible statement: the soap era was over, and the laboratory era wasn’t a side business anymore—it was the business.

In 2012, Campbell Brothers Limited was renamed ‘ALS Limited’, and has divested its former manufacturing businesses.

By then, the gap between name and reality had become too wide to ignore. “Campbell Brothers” still sounded like a traditional industrial manufacturer—an echo of nineteenth-century Brisbane. But the company’s center of gravity had long since shifted to testing. “ALS,” derived from Australian Laboratory Services, finally matched what customers and employees experienced day-to-day: a science-and-process organization built around accuracy, turnaround time, and trust.

That same year, the company was inducted into the Queensland Business Leaders Hall of Fame. The timing mattered. The honor wasn’t just for longevity; it was recognition that this was a Queensland company that had managed to reinvent itself, scale internationally, and stay relevant across radically different economic eras.

The divestiture that came with the name change was just as important as the new logo on the letterhead. For decades, the legacy manufacturing operations had sat alongside the fast-growing laboratory services business—steady but distracting, adding complexity, and muddying the story for investors. Exiting them wasn’t about squeezing a little extra profit; it was about focus. It was ALS choosing a lane and committing to it.

After 2012, the company that emerged was far easier to understand: a focused global testing leader, no longer a mixed portfolio of old manufacturing and modern services, but a pure-play participant in the testing, inspection, and certification industry. That clarity mattered in capital markets, where ALS could be evaluated against the right peers—and internally, where strategy and resource allocation could stop being a compromise.

For anyone looking at ALS today, 2012 is the moment the company stopped carrying its past around in its name. It didn’t just act like ALS. It finally became ALS.

VII. The Life Sciences Pivot (2011–2017): De-Risking the Mining Dependency

By the time the ALS name was on the door, the company had earned something close to “default choice” status in minerals testing. But success brought a new kind of risk—one that every mining-adjacent business eventually runs into.

ALS was heavily tied to mining exploration activity. And commodity cycles are brutally volatile. When prices drop, miners don’t ease off exploration spending—they slam the brakes. For a lab network built around exploration samples, that volatility can hit fast and hard.

So ALS did what disciplined operators do when they see a structural weakness: it started building an escape hatch.

Between 2011 and 2017, ALS accelerated its expansion into life sciences—adding services in pharmaceuticals and health care, along with food safety and quality testing.

The logic was simple, and it was powerful. Environmental, food, and pharmaceutical testing are driven less by commodity prices and more by regulation and compliance. Companies still need environmental monitoring whether copper is booming or crashing. Food safety testing doesn’t take a holiday in a downturn. Pharmaceutical quality control is mandatory, full stop.

But the strategy that reads cleanly in an annual report is messy in real life. ALS had spent decades serving mining clients with mining timelines, mining vocabulary, and mining expectations. Life sciences meant new customers, new regulatory regimes, and a different kind of reputation to build. The question wasn’t whether the market was attractive. It was whether ALS could actually win in it.

ALS didn’t try to brute-force the transition by building everything from scratch. Instead, it used a familiar playbook: invest organically where it made sense, and make targeted acquisitions where speed and capability mattered. It expanded environmental testing, added food safety labs, and then pushed into pharmaceutical testing—each move stacking on the last.

The Life Sciences segment offers analytical testing and sampling, and remote monitoring services for the environmental, food, pharmaceutical, and consumer products markets; and microbiological, physical, and chemical testing services.

That diversification came with real cultural and operational strain. Minerals testing is its own world. Life sciences is another. ALS had to build new expertise and credibility without letting its core minerals franchise slip—because the worst-case scenario wasn’t just failing in life sciences; it was distracting itself into losing what it already dominated.

The good news was that the bridge into Life Sciences had a natural starting point. Environmental testing shared important DNA with minerals: rigorous sample handling, standardized methods, strict accreditations, and technically demanding clients. That overlap made Environmental the early standout inside the new portfolio—and a proof point that ALS could transfer its process discipline into adjacent markets.

From an investor’s perspective, this whole pivot was less about chasing growth for its own sake and more about engineering resilience. By building a meaningful second engine, ALS reduced its dependence on the mining cycle. The company that came out the other side wasn’t just bigger—it was structurally tougher than the minerals-heavy ALS that went in.

VIII. The Modern Acquisition Machine (2020–2025)

From 2020 through 2025, ALS hit the accelerator on acquisitions—especially in Life Sciences, where it was still building share and credibility rather than defending an entrenched lead.

In March 2024, ALS announced two deals that made the strategy feel very concrete: the acquisition of Northeast USA-based York Analytical Laboratories and Western Europe-based Wessling Holding GmbH & Co. KG. Together, they were designed to push deeper into Life Sciences—particularly Environmental testing—at exactly the moment regulation, public scrutiny, and client demand were making that category bigger and more urgent.

The combined purchase price was about A$225 million, funded from existing bank debt facilities, and ALS expected the two businesses together to add roughly A$195 million of annual revenue on a full-year basis.

York was the sharper “why now” move. The acquisition targeted PFAS testing—one of the fastest-growing subsegments in environmental analysis as regulators and communities focus on “forever chemicals” in water supplies. ALS noted that York “entered the PFAS market early with the first PFAS lab in New York City and have built an impressive operation.” York brought more than 200 staff, four laboratories, and four service centers across New York, New Jersey, and Connecticut—density in one of the world’s biggest environmental testing markets.

Wessling was a different kind of asset: scale, footprint, and a rare profile in a consolidating industry. Founded in 1983, it was one of the last large independent, family-owned providers of laboratory testing and engineering services in Europe—still family-owned and managed when ALS bought it. The acquisition was completed effective May 31, 2024, giving ALS an immediate platform across Western Europe rather than years of incremental build-out.

And then there was pharmaceuticals—where ALS made its boldest move with Nuvisan. ALS acquired an initial 49% interest in NUVISAN, a pharmaceutical testing business operating in Germany and France. Founded in 1979, Nuvisan was privately owned and had over 1,000 employees. In March 2024, ALS acquired the remaining 51% stake at no additional cost.

But Nuvisan also came with the kind of risk that doesn’t show up in the press release headline. The business was set to go through a two-year transformation program aimed at driving sales growth in key markets and implementing cost reduction measures to improve profitability. This wasn’t the clean “buy a great business and plug it in” version of M&A. It required operational work—restructuring—to earn acceptable returns.

Importantly, ALS wasn’t relying on acquisitions alone. Alongside the deals, it committed significant capital to organic growth through a multi-year expansion program—about $230 million earmarked for upgrading key hub laboratories in Peru, Australia, Thailand, and the Czech Republic. ALS has four key hub laboratories globally, and it said they were reaching capacity. In other words: the constraint wasn’t demand, it was throughput.

To fund the next leg of the plan, in May 2025 ALS announced a fully underwritten A$350 million institutional placement, plus a non-underwritten share purchase plan to raise up to A$40 million. The message to the market was clear: ALS was choosing to keep investing for growth, not simply harvest what it had built.

For investors, this era matters because it shows how ALS sees itself. M&A isn’t occasional opportunism—it’s a practiced muscle. The company aims to identify the right targets, execute quickly, and integrate without breaking quality or client relationships. The record earns credibility, but Nuvisan is the reminder baked into every acquisition story: sometimes value isn’t bought—it has to be rebuilt.

IX. Business Model Deep Dive: How ALS Actually Makes Money

To really understand ALS, you have to zoom in from the headline—“global testing company”—to the factory floor version of a laboratory. Because yes, the workflow sounds simple: samples come in, tests happen, results go out. But the economics are anything but simple. This is a logistics business, a quality system, and a technical production line—wrapped into one.

ALS runs through three segments: Life Sciences, Commodities, and Industrial. For most of its modern history, the economic engine has been Commodities: assaying and analytical testing, plus metallurgical services for mining and mineral exploration companies.

In Commodities, the model is volume-based and capital-heavy. Labs carry meaningful fixed costs—equipment, facilities, and, most importantly, skilled technical staff. Once that base is in place, every additional sample pushed through the system tends to carry attractive incremental economics. That’s the magic and the danger of operating leverage: when exploration activity is strong, margins can expand quickly; when volumes fall, the fixed-cost base doesn’t shrink nearly as fast.

Even with that cyclicality, the Minerals segment maintained a resilient margin of 31.1%. In this business, margins above 30% aren’t an accident. They signal scale, efficiency, and—crucially—the ability to compete on quality and turnaround time, not just price.

One of ALS’s highest-value offerings sits a layer above routine exploration assays: metallurgy. ALS Metallurgy is the market leader in bankable metallurgical testwork for mineral process flowsheet development and optimisation. “Bankable” isn’t marketing language—it’s a standard. This is testwork reliable enough that project financiers and equity investors will base funding decisions on it. That level of confidence commands premium pricing and deepens client trust.

ALS also benefits from being present across the full resource life cycle. Commodities testing and consulting can show up at exploration, feasibility, optimization, production, design, development, trade, and even rehabilitation. That breadth matters. A single mining project can generate many different kinds of testing work over many years, and the relationship tends to compound as the project moves from “maybe” to “real.”

Life Sciences works on a different demand curve. It includes analytical testing and sampling, remote monitoring, and microbiological, physical, and chemical testing across environmental, food, pharmaceutical, and consumer products markets.

Here, demand is often regulation-led rather than commodity-led. Environmental testing is supported by permitting requirements and ongoing monitoring obligations—air, water, soil. Food safety testing grows with tighter standards and rising consumer expectations. Pharmaceutical testing is tied to quality systems that are mandatory, not optional. The result is a segment that, in theory, should behave more steadily through economic cycles.

Underneath both segments is the same core production system. Physical samples arrive at a facility, are prepared under strict protocols, run through specialized instrumentation, and then reported back to clients in a format they can act on. Doing this well—accurately, consistently, and fast—is the competitive game. Operational excellence isn’t a nice-to-have; it’s the product.

And that’s why testing services are so sticky. Switching labs isn’t like switching office suppliers. Clients worry about accreditation, chain-of-custody, method consistency, and whether results will be comparable to prior datasets. ALS reinforces those switching costs with process discipline: quality is embedded in day-to-day work and monitored across the organization. It’s also enabled by a truly integrated global laboratory information management system (LIMS), which manages quality requirements and supports real-time management oversight.

Put it together, and you get a business with some very attractive traits—recurring client relationships, operational leverage when volumes rise, and meaningful switching costs that protect hard-won positions. The tradeoff is that you have to watch the right indicators: sample volumes (especially in minerals exploration), segment margins, and whether Life Sciences is delivering real organic growth rather than just acquisition-fueled expansion.

X. Competitive Landscape & Industry Dynamics

ALS operates inside the global testing, inspection, and certification industry—usually shortened to “TIC.” It’s a huge market, but it doesn’t behave like one unified arena. It’s more like a patchwork: a handful of global giants, and then thousands of regional and specialist players running local labs, niche certifications, and industry-specific inspection businesses.

That fragmentation is why TIC has remained such a fertile hunting ground for consolidators. Even though the overall market is expected to grow from about $239 billion in 2025 to roughly $283 billion by 2030—steady, not explosive—some pockets are growing far faster. Environmental categories like PFAS testing are one example. The big takeaway is that TIC isn’t a “one growth rate” market; it’s a portfolio of sub-markets, each moving at its own speed.

At the top end, the names you’d expect show up: SGS (Switzerland), Bureau Veritas (France), Intertek (UK), TÜV SÜD (Germany), and TÜV Rheinland (Germany). These companies have breadth—many service lines, many geographies, and deep relationships with multinational customers.

But here’s the twist: despite those giants, the market is still only moderately concentrated. The five biggest players collectively hold around 10–15% of total market share. That’s enough to establish real scale advantages, but nowhere near enough to “own” the space. Most of the industry remains in the long tail, which keeps M&A on the table year after year.

ALS sits in an interesting position relative to that landscape. It’s directly in the ring with the giants in certain categories, and in one notable framing, ALS is Bureau Veritas’s number three competitor. That’s a useful signal: ALS isn’t just a local specialist anymore—it’s a credible global peer in meaningful parts of the market.

Where ALS truly stands out is minerals. In geochemistry and metallurgy, it isn’t playing challenger—it’s defending leadership. As the company puts it: “ALS is the global leader in metallurgical testing and consulting services for mineral process flowsheet development and optimisation.” That position is the product of decades of accumulated capability: global lab density, standardized methods, and the kind of reputation that mining clients rarely hand over to a newcomer.

Life Sciences is different. Here, ALS is still building, not defending. Environmental testing has plenty of capable competitors, and pharmaceutical testing is full of entrenched players with long-standing customer relationships. That’s why ALS’s Life Sciences strategy has leaned so heavily on acquisitions—buying footholds, density, and capability—and then applying the same operating discipline that made the minerals network work.

This is also the direction the whole industry is moving. To expand coverage and add higher-growth offerings, the TIC leaders have been using acquisitions and partnerships to pick up niche expertise—whether that’s in cybersecurity, environmental testing, or digital compliance. The logic is consistent: buy specialists, then scale them.

The competitive dynamics make consolidation feel almost inevitable. Larger players can spread lab fixed costs over more samples, invest more in methods and technology, and offer multinational clients consistent service across regions. Smaller players can still thrive in niches—but competing on technology, turnaround time, and geographic coverage gets harder every year, and that creates a steady stream of potential acquisition targets for companies like ALS.

Even at the very top, the consolidation pressure shows through. In January 2025, Bureau Veritas and SGS were reportedly in merger talks—an attempt to create a testing and certification giant valued at more than $30 billion. The talks ended without an agreement, which is its own lesson: everyone feels the pressure to combine, but megamergers are hard to execute.

For investors, this landscape cuts both ways. ALS benefits from the same consolidation trend shaping the entire industry, and it has real strength where it matters most in minerals. But it’s also competing against extremely well-capitalized rivals with broader portfolios—and in some Life Sciences categories, stronger incumbency. In TIC, scale helps, reputation matters, and the fight is constant.

XI. Porter's Five Forces Analysis

Zooming out and looking at ALS through Porter’s Five Forces helps explain something that can feel counterintuitive at first: even if a lot of day-to-day testing work looks “commodity-like,” the industry structure can still be pretty attractive—especially for scaled, accredited players with reputations to protect.

Threat of New Entrants: LOW-MEDIUM

Starting a credible laboratory business isn’t like renting a space and hanging a sign. You need expensive facilities and instruments, accreditation and regulatory compliance, and—most importantly—client trust that’s earned over years, not weeks. Those hurdles protect incumbents from casual competition.

But the threat isn’t zero. New entrants can still carve out niches, especially in specific geographies or fast-growing categories like regional environmental testing or specialist PFAS work. The barriers also vary by segment: minerals testing tends to be harder to break into than some parts of environmental testing.

Bargaining Power of Suppliers: LOW

Most lab equipment is available from multiple manufacturers, and switching suppliers usually doesn’t create existential risk for operations. The real “input” that matters is skilled people—scientists and technicians with the right experience. Talent isn’t unlimited, but the labor market is competitive enough that no single supplier holds the lab hostage.

Scale helps here, too. ALS can buy equipment and consumables on better terms than smaller competitors, which keeps supplier power in check.

Bargaining Power of Buyers: MEDIUM

Some buyers are big and sophisticated. Large mining companies, in particular, can negotiate hard because they generate huge volumes and can allocate work across multiple providers. But they can’t switch labs as easily as they can switch, say, freight vendors. Accreditation requirements, chain-of-custody, method consistency, and data comparability all create friction. And in a business where a bad result can lead to very expensive decisions, trust and turnaround time often beat the cheapest quote.

In Life Sciences, the customer base is typically more fragmented, which reduces the influence any single buyer can exert.

Threat of Substitutes: LOW

In many contexts, third-party testing isn’t optional—it’s required. Mining companies can’t self-certify resource estimates. Pharmaceutical manufacturers can’t credibly validate their own quality systems in isolation. In-house testing can exist at the margins, but without independent accreditation and credibility, it usually can’t replace an external lab for compliance-grade work.

If anything, the broader trend has moved in the opposite direction: more industries are outsourcing TIC services to specialist providers, reinforcing demand for independent testing rather than substituting away from it.

Industry Rivalry: HIGH

This is where the fight is. Competition in TIC is intense, especially in high-volume, routine categories where differentiation is harder and pricing pressure is constant. That pressure is one reason consolidation keeps happening: scale can lower unit costs and fund the investments needed to stay competitive.

The winners are the labs that can differentiate on what actually matters to customers: technology and methods, turnaround time, quality and reputation, and geographic coverage.

Put together, the picture is mixed—but generally favorable for a player like ALS. Supplier power and substitution risk are low, and barriers to entry are real. The ongoing battles are buyer negotiations and fierce rivalry—but those are exactly the arenas where scale, systems, and reputation tend to compound over time.

XII. Hamilton's 7 Powers Analysis

If Porter tells you why the industry is attractive, Hamilton Helmer’s 7 Powers tells you something more specific: why a particular company can keep winning inside that industry. For ALS, it’s the difference between being a lab network and being the lab network clients trust, regulators accept, and competitors struggle to match.

Scale Economies: STRONG

ALS has the kind of footprint that turns a fixed-cost business into a compounding machine. With more than 19,000 staff, it operates from over 350 locations across 70-plus countries. In laboratories, the big costs aren’t optional: specialized equipment, facilities, and quality systems. At smaller scale, those costs crush you. At ALS scale, they get spread across huge sample volumes.

This is where the hub laboratory model shines. Once the hubs are built and staffed, pushing more samples through them tends to drop disproportionately to the bottom line. That operational leverage is one of the most important “quiet moats” in the entire business.

Network Effects: WEAK-MODERATE

Testing doesn’t have a classic network effect. One client doesn’t get more value because another client shows up. But ALS does get something adjacent to it.

Global customers benefit from being able to use the same provider across geographies and still get consistent service, methods, and reporting. And inside the company, there’s real benefit from shared data, shared methodologies, and shared systems across the network. ALS’s global Laboratory Information Management System (LIMS) is the backbone here: it supports standardization and quality control in a way that a collection of disconnected local labs can’t easily replicate.

Counter-Positioning: STRONG (Historically)

ALS’s defining moves have often been the ones competitors weren’t structurally set up to make.

The 1981 pivot—away from legacy manufacturing and into laboratory services—was counter-positioning in its purest form. The later diversification into Life Sciences was another: reducing dependence on mining cycles at a time when many peers stayed heavily tied to commodities. ALS has framed this explicitly in its acquisition messaging: “This is an important and highly strategic acquisition for us. We have demonstrated our capacity of acquiring new businesses into our existing Life Sciences network.”

Counter-positioning isn’t about being contrarian. It’s about moving early into a strategy that looks unattractive or risky to incumbents—until it’s too late.

Switching Costs: MODERATE-STRONG

In this business, switching isn’t just annoying—it can be dangerous.

Accreditation and approval processes create real friction. Clients also build workflows around their labs: data formats, reporting requirements, turnaround-time expectations, and escalation paths when something looks off. And when results can influence enormous investment decisions, track record matters. Labs earn trust slowly and lose it quickly.

That creates meaningful continuity bias. ALS doesn’t become untouchable, but it does become harder to replace once embedded—especially for clients who value comparability with historical datasets.

Branding: MODERATE

In minerals testing, the ALS name carries weight because reputation is earned one accurate result at a time, over decades. ALS emphasizes that “the cornerstone of our business is providing exceptional quality assays,” and in minerals, that promise is part of why the brand is sticky.

In Life Sciences, the branding power is more uneven. ALS is still building recognition across environmental, food, and pharma testing, and it often competes with incumbents that have longer track records in those specific niches.

Cornered Resource: MODERATE

ALS’s most defensible “resource” isn’t a patent. It’s people, know-how, and the accumulated craft of running large-scale labs well.

Access to specialized technical talent matters, and so does institutional memory: methodologies refined over time, hard-won operational best practices, and the muscle memory of integrating laboratories without breaking quality. Leadership continuity contributes too. Malcolm Deane, appointed CEO and Managing Director in May 2023, had already spent the prior decade in senior roles across the company, including leadership positions in Life Sciences and as Chief Strategy Officer.

And there’s a physical component: strategic lab locations in mining regions and major metropolitan centers—sites that take time, approvals, and credibility to build.

Process Power: STRONG

If ALS has a superpower, this is it.

The company’s edge isn’t just owning labs—it’s running them with consistent, replicable excellence across a global footprint. ALS has continued investing in technological advancement and digitalization, and it pairs that with standardized processes designed to deliver consistent quality regardless of which facility touches the sample.

That discipline is reinforced through a global quality program: internal and external inter-laboratory test programs, plus regularly scheduled internal audits aligned with ISO/IEC 17025:2017 and ISO 9001:2015. Process Power is hard to see from the outside, but it’s brutally hard to copy quickly—and in testing, it’s exactly what clients pay for.

Taken together, the 7 Powers lens suggests ALS’s durability comes from scale economies, switching costs, and process power—supported by counter-positioning and a strong minerals reputation. In an industry that can look commoditized from a distance, those are the forces that let ALS keep earning strong returns while it expands into new categories and geographies.

XIII. Playbook: Strategic & Business Lessons

ALS’s 160-year journey is a reminder that “strategy” isn’t just what you say in a deck. It’s what you do when the world changes—and when your existing business, however respectable, stops being the best use of your time and capital.

The Art of the Strategic Pivot

Campbell Brothers’ transformation from soap manufacturer to global testing leader is proof that corporate identity doesn’t have to be permanent. When a legacy business faces structural decline, the winning move isn’t to optimize it forever—it’s to recognize reality and move.

That’s what the 1981 acquisition of Australian Laboratory Services represented: management willing to bet on an unfamiliar business, with unfamiliar customers, rather than squeezing incremental gains out of a category that had already matured. And the 2012 rebrand to ALS completed what the underlying business had become decades earlier—turning a historical name into a modern, focused identity.

Acquisition as a Core Competency

Over four decades, ALS executed dozens of acquisitions and, in the process, built something many companies never manage: a repeatable M&A system. Not just dealmaking, but target selection, due diligence, execution, and the hard part—post-merger integration without damaging quality or client trust.

Chemex and Bondar Clegg built the minerals footprint. The Life Sciences push expanded the end markets. York and Wessling added density and capability in Environmental. The pattern across all of them is the point: ALS didn’t just buy businesses—it learned how to keep buying them, with increasing confidence that the next deal benefits from the last one.

Geographic Expansion Following the Customer

ALS didn’t expand internationally just to paint a bigger map. It expanded because its customers did.

When exploration activity surged in South America, ALS built labs there. As mining activity increased in Africa, ALS followed. This customer-led approach meant new sites weren’t speculative; they had demand from the start, instead of needing years of brand-building and market education to justify the investment.

Diversification Without Distraction

The Life Sciences pivot worked because it wasn’t diversification for diversification’s sake. ALS stayed within its core competency—laboratory testing—while diversifying the markets it served.

That’s very different from the classic conglomerate mistake of buying unrelated businesses and hoping management skill alone will carry the day. ALS moved into adjacent categories where its operational strengths—process discipline, accreditation, chain-of-custody, and throughput management—still mattered. The result was lower exposure to mining cycles without needing to become a fundamentally different kind of company.

Patience in Cyclical Industries

Mining exploration spending is volatile, and ALS has lived through multiple boom-and-bust cycles. The lesson isn’t just resilience—it’s capacity management and discipline.

Companies that slash too deeply in downturns can’t respond when volumes come back. ALS’s ability to weather softer periods without abandoning long-term investment positioned it to capture the recovery when the cycle turned—often while weaker competitors were still rebuilding.

The Power of Boring Businesses

Laboratory testing will never have the glamour of consumer brands or software. But it has some of the best business qualities hiding in plain sight: repeat work from long-running client relationships, baseline demand supported by regulation, and meaningful switching costs once a lab is trusted and embedded.

“Boring” can be beautiful—especially when the economics reward consistency, credibility, and scale.

Capital Allocation Discipline

Growth only creates value if returns hold up. ALS has emphasized capital allocation discipline, including minimum ROCE thresholds, across both acquisitions and organic investment. That focus matters because acquisitive companies often fall into a familiar trap: getting bigger while getting worse.

ALS’s story suggests a different approach—grow, but don’t abandon the return bar. That mindset is a big part of why the company could pivot, scale globally, and keep compounding rather than simply expanding.

XIV. Bear Case vs. Bull Case

Bear Case:

The bear case for ALS is straightforward: the business has done an impressive job diversifying, but several of its biggest risks still rhyme with its history.

Mining cyclicality remains the headline concern. Even after the push into Life Sciences, Commodities still makes up a meaningful share of revenue—and an even larger share of profits, given the higher margins. When exploration budgets fall, they don’t decline gently; they can fall off a cliff, like they did in the 2014–2016 commodity downturn. And even when volumes recover, pricing can bite. ALS has warned that the price pressures seen in Minerals in FY25 are expected to largely offset the full operating leverage benefit in FY26.

Pharmaceutical challenges are the second pressure point. Nuvisan was never positioned as a “plug-and-play” acquisition; it came with restructuring baked in. The pharmaceutical testing market has faced broader headwinds, and ALS has felt it: Pharmaceutical business organic revenue declined by 3.4%, with mixed performance across operations. The transformation program is moving forward, but it’s still a turnaround, and execution risk is real.

Then there’s integration risk. ALS has been buying aggressively, and every deal—no matter how strategic—demands management attention and operational focus to integrate systems, methods, and culture without damaging quality or client trust. That integration capacity is not unlimited. If execution slips, the math can flip: the value created by acquisitions can be offset by the value lost in integration missteps.

Competition is another structural issue. TIC has giants, and ALS often competes directly with players like SGS and Bureau Veritas—companies with deeper pockets, broader portfolios, and the ability to invest heavily in technology, pursue larger acquisitions, or underprice selectively to win share in certain segments.

Finally, there’s long-term technology disruption. It’s not an immediate threat to the core business, but the direction is worth watching: in-line sensors, portable testing devices, and AI-driven analysis could, over time, reduce demand for traditional lab-based testing in certain categories.

Add it up, and ALS is navigating a landscape where a few things have to go right at once: keep Life Sciences growing, keep the acquisition machine disciplined, and avoid getting whipsawed by the next commodity downturn.

Bull Case:

The bull case is equally clear: ALS has a repeatable playbook, and it operates in markets that are quietly getting larger and more regulation-driven over time.

At the highest level, the global testing, inspection and certification (TIC) market is expected to grow from USD 272.9 billion in 2025 to USD 430.3 billion in 2034, at a CAGR of 5.2%. That’s not hypergrowth, but it is a long runway—one that tends to hold up better than many cyclical industries.

More importantly, ALS is leaning into the faster-growing parts of that runway. Environmental testing has become a regulatory priority, and PFAS is the clearest example. The PFAS testing market was valued at US$ 406.5 million in 2024 and is expected to reach US$ 661.3 million by 2031, growing at a 14.5% CAGR. ALS’s acquisition of York wasn’t just “more labs”—it was a direct position in a category growing far faster than the market average.

Life Sciences diversification continues to reshape the company into something more resilient. Underlying revenue reached $3 billion, up 16.0%, driven by strong organic and scope growth within Life Sciences. Environmental testing was a standout, reinforcing the idea that ALS isn’t just buying growth—it’s building a steadier demand base than the one it inherited from a mining-heavy past.

And even as Life Sciences grows, Minerals remains a real advantage, not a legacy burden. ALS’s leadership—especially in metallurgy—gives it a defensible position that competitors would struggle to recreate quickly. As ALS says, “ALS is the global leader in metallurgical testing and consulting services for mineral process flowsheet development and optimisation.” In a trust-and-reputation business, “hard to replicate” is the moat.

Operationally, ALS is still finding ways to improve. The Group is targeting continued margin improvement within legacy operations of between 20–40 bps in FY26, which matters because in a fixed-cost, throughput-driven model, small efficiency gains can compound meaningfully over time.

Finally, there’s the simplest bull argument: this team has done it before. ALS has built credibility as an acquirer and integrator, and it remains on track to execute its strategy and meet its FY27 financial targets, including growing revenue to $3.3 billion and growing underlying EBIT to $600 million.

In other words, the bull case isn’t that ALS avoids every risk. It’s that ALS has the scale, systems, and playbook to keep compounding through them.

XV. Key Performance Indicators for Investors

If you’re tracking ALS quarter to quarter, it’s easy to get lost in the noise. The company is global, acquisitive, and exposed to very different end markets. But the story usually shows up first in three places:

Minerals sample volumes and margins

In Minerals, sample volumes are the early-warning system for the commodity cycle. When exploration budgets rise, samples start flowing. When miners cut back, labs feel it fast. Pair that with margins and you get the real signal: not just whether demand is up or down, but whether ALS is holding pricing power and running its network efficiently. The Minerals segment maintained a resilient margin of 31.1%. Watching volumes and margins together is the simplest way to read the health of ALS’s most profitable engine.

Life Sciences organic growth rate

Life Sciences is the diversification bet, so the most important question is: is it growing on its own, or only because ALS keeps buying? Organic growth—stripping out acquisitions—shows whether ALS is actually winning share and earning repeat work in environmental, food, and pharma testing. The Environmental business delivered strong organic revenue growth of 11.8%. Sustained double-digit organic growth is a sign the strategy is working; if growth fades to low single digits or turns negative, it’s a sign to dig deeper.

Acquisition integration progress

ALS’s M&A pace makes integration a core operational competency, not a side project. The fastest way to test that competency is to follow the newest, messiest integration work—especially where ALS has been transparent that a turnaround is required. Nuvisan is the clearest example. Tracking cost reductions and revenue stabilization versus the company’s stated targets shows whether the transformation is delivering. Nuvisan’s transformation is progressing well and cost reductions are slightly ahead of plan.

Taken together—minerals volume and margin trends, Life Sciences organic growth, and integration execution—these KPIs tell you whether ALS is doing the hard thing well: riding out commodity cycles while steadily building a more diversified, more resilient testing business.

XVI. Final Observations

ALS’s story is a case study in corporate reinvention done the hard way: not through hype, not through a single breakthrough product, but through a series of disciplined choices that steadily changed what the company was. A Victorian-era Brisbane soap maker became a global scientific testing leader because it was willing to abandon a perfectly respectable past in order to build a more durable future.

You can trace that transformation through a few decisive moments. The 1981 shift into laboratory services was a bet placed before the old business was broken. The Chemex and Bondar Clegg acquisitions turned that bet into global minerals leadership—bold moves, but grounded in the logic of scale, reputation, and a fragmented market waiting to be consolidated. The Life Sciences push, especially across environmental, food, and pharmaceutical testing, reduced exposure to mining cycles without forcing ALS to learn an entirely new kind of business. And the more recent acquisition cadence shows the same pattern repeating: build density where regulation and demand are expanding, then apply the ALS operating system.

For investors, that creates a rare mix in a single company: leadership in a specialized, trust-heavy niche (minerals testing), increasing exposure to more defensive, regulation-led markets (environmental and food testing), and a track record of using acquisitions as a repeatable capability rather than a one-off event. ALS trades on the Australian Securities Exchange under the ticker ALQ, offering access to those dynamics through one stock.

None of this is risk-free. Commodity cyclicality still matters. The pharmaceutical segment has required real operational work, not just capital. And integration is never “done”—it has to be executed again with every deal, without compromising quality or client trust. But the advantages are real, too: scale economies in a fixed-cost lab network, meaningful switching costs once a lab is embedded, process power built through standardization and systems, and a brand that carries weight where credibility is the product.

Peter Morrison Campbell couldn’t possibly have envisioned what his company would become: analyzing ore samples for gold miners in Peru, testing drinking water for PFAS contamination in the U.S., and supporting pharmaceutical quality control in Europe. But that’s the through-line of the last 160 years. ALS has shown that a company can outgrow its original identity—and that, with the right mix of focus and flexibility, the journey from soap to science doesn’t have to end. It can keep compounding.

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music