Auckland International Airport: New Zealand's Gateway to the World

I. Introduction: The Monopoly at the Edge of the World

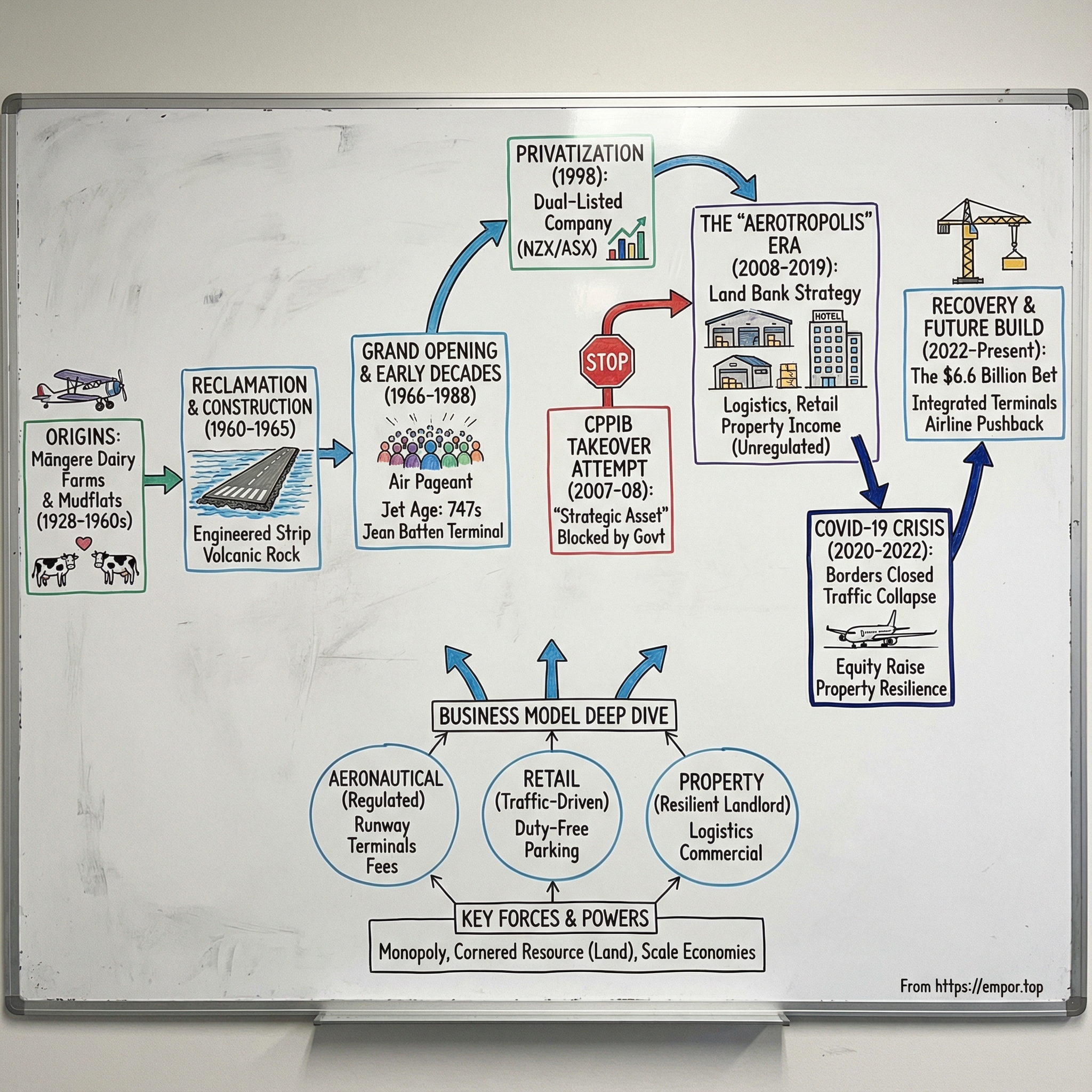

Arrive in Auckland after twelve hours from Los Angeles, or eleven from Singapore, and the last few minutes of the flight feel like a reveal. The plane drops beneath the clouds and there it is: the Manukau Harbour, green hills beyond it, and a runway that seems to sit right on the water. That’s because, in a very real sense, it does. Auckland’s main runway was built on land reclaimed from what had been tidal mudflats—an engineered strip of certainty at the edge of a very large ocean.

This is Auckland Airport: the country’s biggest and busiest, serving more than 18.7 million passengers in the year ended December 2024. It also handles about three-quarters of New Zealand’s international arrivals and departures. And when you control that kind of flow in a nation this isolated, you’re not just operating an airport. You’re running one of the most important choke points in the entire economy.

In markets, that importance shows up in the share register. Auckland International Airport is dual-listed on the NZX and ASX, and it has often sat among the largest companies on the NZX, with a market capitalisation above $10 billion. To infrastructure investors, it’s catnip: a natural monopoly in a stable democracy, regulated returns, a sprawling land bank, and customers—airlines, retailers, travelers—who don’t have a realistic substitute if they want to get in and out of the country’s largest city.

So here’s the question that makes Auckland Airport more than “just” an airport. How did a government-built facility on reclaimed land turn into a $10+ billion infrastructure juggernaut—one that fended off a high-profile takeover attempt, survived a global pandemic that crushed international travel, and still managed to come out the other side as a case study in monopoly economics done the right way?

Because this story isn’t only about planes and terminals. It’s about privatization done right, the quiet power of patient real-estate capital, the art of navigating regulatory moats, and what resilience really looks like when your core business can drop off a cliff overnight.

II. Origins: From Dairy Farms to Jet Age

To understand Auckland Airport, you have to start with New Zealand’s geography—and its problem. This is a country of about five million people, sitting more than 2,000 kilometers from its nearest significant neighbor, Australia, and a very long way from its traditional markets in Europe and North America. For New Zealand, air links aren’t a luxury. They’re the connective tissue of the economy.

Long before “Auckland International Airport” was even an idea, the site was just rural Māngere. In 1928, the Auckland Aero Club leased a patch of land from a dairy farmer to fly three De Havilland Gypsy Moths. Even then, the club’s president could see what the map hinted at: this place worked. “It has many advantages of vital importance for an aerodrome and training ground,” he said. “It has good approaches, is well drained and is free from power lines, buildings and fogs.”

That early verdict aged well.

Māngere had something New Zealand doesn’t have in abundance: naturally flat ground. It sat on volcanic terrain at the edge of the Manukau Harbour, where long, modern runways could be built without heroic earthworks. Better still, the local mix of volcanic rock and topsoil made it well-suited to reclamation—an approach that would eventually push the runway out into what had been harbour water.

For a time, Auckland muddled through with Whenuapai. From 1948, RNZAF Base Auckland at Whenuapai served as the city’s civilian airport—cheap for the Auckland City Council because it already existed as a military base, but increasingly awkward as aircraft evolved. The hills nearby limited what newer planes could do. In September 1948, a report by Sir Frederick Tymms recommended moving to a purpose-built airport, with Māngere or Pakuranga as the leading candidates.

That recommendation was the spark. In 1958, the New Zealand Government commissioned Leigh Fisher Associates to survey and design an international airport at Māngere. Two years later, in 1960, construction began. And in a detail that still defines Auckland Airport today: much of the runway was created on land reclaimed from the Manukau Harbour.

It was an audacious project for a small country. Engineers didn’t just build an airport—they manufactured the ground beneath it, using volcanic rock to carve out certainty from tidal flats. The message was clear: if New Zealand was going to be part of the jet age, it would have to build the infrastructure to reach it.

The first departure came in November 1965: an Air New Zealand DC-8 lifting off for Sydney. Within months, Auckland had its new gateway. And from the start, the airport wasn’t laid out like a facility meant to stay small. The site choice and the reclamation weren’t only about solving the problem of the day—they were a commitment to future expansion, baked into the ground itself.

III. The Grand Opening and Early Decades (1966–1988)

On 29 January 1966, Auckland Airport officially opened—and New Zealand treated it like a national event. The celebration was a three-day “Grand Air Pageant” that drew more than 200,000 people. In a country of roughly 2.7 million at the time, that turnout said everything: this wasn’t just a new piece of infrastructure. It was a new connection to the world.

The opening was presided over by the Governor-General, Sir Bernard Fergusson. Visitors wandered the tarmac, toured the new buildings, and packed in to see aircraft lined up from New Zealand and overseas—civilian and military—like a living museum of aviation’s present and future. Above them, the show ran all day: flybys from the New Zealand and United States air forces, aerobatics, and parachute displays. It was part spectacle, part statement. New Zealand had built its gateway, and it intended to use it.

The growth that followed came fast. In its first year, Auckland Airport handled more than 700,000 passenger movements—about what the airport now processes in roughly two weeks over the Christmas and New Year rush. And the upward curve didn’t really let up.

Bigger planes arrived, and the airport stretched to meet them. In 1973, the runway was extended westward to 3,292 metres. Even before that work was finished, a milestone landed: on 8 December 1972, Qantas began the first scheduled Boeing 747 service out of Auckland. The jumbo jet changed the math of flying to and from New Zealand. It could carry far more people than the DC-8s and 707s it followed, and it pushed Auckland further into the era of high-volume, long-haul travel.

Then came a more subtle shift: the airport began to separate domestic and international travel at scale. In 1977, a new international terminal opened, and the old combined terminal became domestic-only. The new international facility was named after Jean Batten, the New Zealand aviator who had set solo flight records between England and New Zealand in the 1930s. It was a symbolic choice—Batten had proven distance could be beaten. Now the airport carrying her name would do it every day, for millions.

By the late 1980s, the pattern was clear: traffic kept rising, aircraft kept getting larger, and the airport kept having to reinvent itself around demand. It was still, at its core, a government-owned utility—built to provide capacity and reliability, not to optimize returns. But one decision from those early decades would matter enormously later: the state accumulated a huge amount of land around the airfield, far more than the airport needed just to land and launch planes. In time, that land would become the quiet engine of Auckland Airport’s value.

IV. Privatization: The Birth of a Listed Company (1998–2000)

By the late 1980s and into the 1990s, New Zealand tore up its old economic playbook. The reform era became known as “Rogernomics,” after Finance Minister Roger Douglas, and later “Ruthanasia,” after Ruth Richardson, who pushed the changes further. State assets were corporatized, subsidies disappeared, whole industries were deregulated, and the public sector was reshaped around a simple idea: if markets could do something better, let them.

Aviation didn’t get a carve-out. Air New Zealand was privatized in 1989, and before long the spotlight swung to airports. The logic was compelling, and slightly counterintuitive. Airports are natural monopolies, yes. But that didn’t automatically mean the government had to own them. If you could design the right rules, private ownership could bring sharper commercial discipline, better operational execution, and—crucially—access to capital markets for the steady, expensive work of building and upgrading infrastructure.

Globally, Auckland was early to this trend. Listed airports had already started appearing in Europe, and more would follow over the next two decades. Auckland Airport joined the first wave in 1998, part of the moment when airports began to shift from being purely civic utilities to being investable, scalable infrastructure businesses.

The privatization itself was straightforward but deliberate. In July 1998, the New Zealand government sold down its controlling stake in a public float, with shares priced at $1.80. Later, Auckland City Council sold half of its 25.6% stake to private investors. Wellington took a similar “for-profit operator with local government as a minority owner” path, but Auckland’s share register became especially distinctive.

That’s because central government fully exited, yet local councils remained meaningful owners—particularly Auckland Council and the former Manukau City Council. The result was an unusual hybrid: a listed company with tens of thousands of shareholders, but with large blocks still held by public bodies that cared about more than just maximizing short-term returns. They cared about jobs, noise, transport links, regional development, and the airport’s role as the front door to the country. In practice, that meant Auckland Airport would always be operating with multiple audiences in mind.

Regulation, too, was very New Zealand. Unlike some overseas privatizations that came with explicit price caps or formal rate-of-return frameworks, New Zealand initially didn’t introduce a formal regime of price regulation for privatized airports. Instead, it leaned on “light-handed regulation”: information disclosure, transparency, and the ever-present threat that if airports pushed their luck, heavier intervention could follow. It was governance by incentive and reputation—an approach built on the idea that essential infrastructure should act responsibly even when it has market power.

For investors, the pitch wrote itself. Airports offered long-lived assets, demand tied to economic growth and tourism, and pricing that could move with inflation—plus the comforting reality that there is only one primary international gateway to New Zealand’s biggest city. Auckland Airport had all of that, and it also had something harder to replicate: a vast land bank that could support retail, car parking, hotels, logistics, and property development alongside the core aeronautical business.

And that $1.80 IPO price? In hindsight, it was a remarkable entry point for anyone willing to hold through the cycles that were coming—booms, political battles, and shocks that would test whether a listed airport could really behave like “steady” infrastructure when the world stopped flying.

V. The Canada Pension Plan Takeover Battle (2007–2008)

If you want to understand what Auckland Airport means to New Zealand—not just economically, but politically—go back to the takeover battle of 2007 and 2008. This was the moment when a listed company collided head-on with the reality that, in New Zealand, the airport isn’t just another asset. It’s critical infrastructure. And critical infrastructure comes with a national-interest test that shareholders don’t control.

One detail tends to surprise people later: CPPIB didn’t come knocking first. According to CPPIB, the approach started from the airport’s side.

"In late 2007, the Board of AIAL approached us asking us to make a full takeover offer for the airport, which we declined because of our belief that it is appropriate for us to have only a non-controlling interest. We have always been clear that our desire is to hold a minority stake in the airport, not a controlling one."

So instead of a full takeover, CPPIB put forward a proposal to buy a large minority position—up to 39.53% of the company. The price was NZ$3.6555 per share, pitched at a substantial premium to where the stock had been trading before takeover speculation took hold. For shareholders, it was a clean chance to lock in big gains. For CPPIB—an infrastructure investor managing retirement money for millions of Canadians—it looked like exactly the sort of long-life, defensive asset you’d want to own for decades.

Inside Auckland Airport, though, the offer created an awkward split-screen. Publicly, the board agreed the price was attractive. Privately, there was a real unease about what it meant for the company’s future and for the country.

The directors unanimously recommended that shareholders accept the offer. But they weren’t aligned on whether shareholders should vote to let CPPIB actually acquire up to 40% of the company. A majority thought the shares would likely be worth more over the long run without CPPIB involved. Two directors took the opposite view: the price was so compelling that shareholders might not see it again anytime soon.

In other words, the board’s message was almost paradoxical: take the money… but think carefully about whether you want this to happen.

Local government didn’t hesitate. Manukau City Council, which held 10.05% of the airport’s shares, rejected the offer outright. It preferred to stay a long-term stakeholder—an early signal that this wasn’t going to be decided on financial metrics alone.

But in the market, momentum built. By the close of the offer period, acceptances had piled up, and the shareholder vote cleared the necessary threshold. On the deal’s own terms, it had effectively worked. The remaining gate was the one that ultimately mattered: regulatory approval under New Zealand’s Overseas Investment Act.

That’s where it stopped.

The New Zealand government blocked CPPIB’s bid, saying it didn’t meet the “benefit to New Zealand” test required under the Act. It wasn’t a rejection based on price, or on CPPIB’s reputation, or even on an accusation of bad faith. The government simply wasn’t satisfied that the criteria were met.

The decision landed hard because CPPIB wasn’t a speculative raider. It was the kind of institution countries usually hope will invest: long-term, conservative, and widely seen as responsible. If an investor like that couldn’t get approval to buy a large stake in the country’s main gateway, it clarified something that had always been true but rarely stated so bluntly.

Auckland Airport might be listed. It might be commercial. But it’s also a strategic national asset. And that means any would-be buyer needs two separate victories: one in the share register, and one in the political system.

After the block, CPPIB abandoned its year-long effort. The episode didn’t just end a deal—it set a precedent. From that point on, Auckland Airport came with an extra layer of reality that every investor had to underwrite: political risk isn’t a footnote here. It’s part of the business model.

VI. Building the "Aerotropolis" (2008–2019)

With the CPPIB bid dead, Auckland Airport moved into a different kind of decade. No takeover drama, no existential shock—just the slow, compounding work of turning a regulated airport into something more resilient and more valuable. And management’s focus narrowed onto the asset that most airports would kill for: the land.

The primary asset was still the airport itself, but wrapped around it sat roughly 1,500 hectares of freehold land. Not leased. Not temporary. Owned outright—giving the company enormous freedom to decide what got built, when, and for whom. Alongside that, Auckland Airport also held investments in Cairns Airport and Mackay Airport in Queensland, Queenstown Airport, and the Tainui Auckland Airport Hotel Partnership.

That land bank changed the business model. Airports everywhere make money from airlines and passengers, but Auckland could also build an ecosystem of “unregulated” revenue—retail and duty-free, car parking, hotels, warehouses, offices, and logistics facilities. It also owned a 25% stake in fast-growing Queenstown Airport on the South Island, giving it a foothold in one of the country’s most tourism-driven markets.

The vision had a name: the “aerotropolis.” The idea—popularized by urban theorist John Kasarda—was that a major airport isn’t just a transport node. Done right, it becomes the center of gravity for a whole cluster of economic activity: freight forwarders, distribution hubs, hospitality, business services, even light industry. Plan it well enough, and the airport becomes the anchor tenant for a new kind of city.

The clearest expression of that strategy was The Landing: more than 100 hectares of planned development land that Auckland Airport turned into a logistics and distribution hub. Over time, it attracted many of the world’s biggest 3PL and logistics players, including Hellmann World Wide Logistics, Toll, DHL, Fonterra, Coca Cola Amatil, Fuji Xerox, Agility Logistics, DSV, Bunnings, and Foodstuffs North Island.

For those tenants, being close to the runway mattered. If you’re moving high-value parts, perishable exports, or time-sensitive freight, minutes and kilometers turn into money. For Auckland Airport, it was something even better: a growing stream of property and commercial income that didn’t rise and fall in lockstep with passenger volumes. It was diversification with a strategic logic—and it monetized the one thing the airport had in abundance that competitors couldn’t replicate.

By this point, the airport precinct had become a real employment and economic center in its own right. More than 20,000 people worked across the broader 1,500-hectare area, spanning aeronautical operations, logistics, commercial services, retail, and hospitality. The airport’s planning also started to widen beyond just “more capacity,” looking ahead to how it would manage climate and environmental pressures, sustainability, digital technology and innovation, the energy transition, and future transport connections.

Meanwhile, the core airport kept modernizing. In 2009, Auckland extended the international terminal with Pier B—about 5,500 square metres, designed to expand further as needed. It opened with two gates capable of handling the Airbus A380. And in May 2009, Emirates became the first airline to fly the A380 to Auckland.

That first A380 arrival was more than an aircraft upgrade. It was a signal. Auckland wasn’t just a remote outpost at the bottom of the map—it was important enough in global airline networks to justify the flagship plane.

By the end of the 2010s, Auckland Airport had quietly evolved into a hybrid: aviation at the core, but surrounded by a growing engine of logistics, retail, hospitality, and property. The airport still lived and died by aircraft movements and passenger flows—but it was building a second set of cash flows that could carry it through the inevitable cycles of travel. That hedge would matter more than anyone realized.

VII. COVID-19: The Existential Crisis (2020–2022)

Nothing in Auckland Airport’s history prepared it for what arrived in early 2020. When chairman Patrick Strange called the preceding six months “the most challenging of Auckland Airport’s 54-year history,” it wasn’t spin. It was a plain description of what it feels like when your business model—moving people across borders—gets switched off by government order.

In the 2021 financial year, Auckland Airport recorded its first loss since it became a public company. Revenue fell 50% as traffic collapsed, and the airport posted an underlying loss of NZ$41.8 million.

The demand shock wasn’t subtle. Total domestic and international travel fell 58% year on year to 6.4 million passengers. International travel was hit hardest: for the 12 months to 30 June 2021, Auckland handled just 0.6 million international passengers including transits, down 93% from the prior year.

New Zealand’s COVID-19 response was among the strictest in the world. The borders were effectively closed and a highly controlled quarantine system was put in place. From a public health perspective, it delivered far fewer COVID deaths per capita than many comparable countries. For Auckland Airport, it was devastating.

International passenger numbers didn’t just decline. They nearly vanished. The international terminal, built for the daily rhythm of tens of thousands arriving and departing, was suddenly serving a trickle—mostly returning New Zealanders entering mandatory quarantine.

With passenger numbers collapsing and the airport scaling back its infrastructure development programme, management made the painful decision to shrink the workforce. By 30 June 2020, Auckland Airport had reduced staff and contractors by about 25%.

They cut costs hard and hit pause on projects where they could. But there’s a brutal asymmetry in aviation: airlines can ground planes and shrink quickly; airports can’t. Runways still need maintenance. Terminals still need to be secured and kept operational. Critical systems still need to run for the limited flights that continued.

As one leader put it: “It was just a cascade of issues. Within a few weeks… the door was shut… we’re raising a billion-plus dollars of equity and our world had completely changed.” In early April 2020, Auckland Airport locked in a NZ$1.2 billion equity raise and extended $700 million in bank commitments.

The capital raise landed in the middle of global market chaos, when the entire aviation sector was staring into the unknown. That Auckland Airport was able to raise that much equity, that quickly, was a vote of confidence in the asset’s long-term reality: the country would not stay sealed off forever, and when New Zealand reopened, the gateway would still be the gateway.

And while the aeronautical side of the business was getting hammered, one part of the portfolio did exactly what it had been built to do. Auckland Airport’s investment property business performed strongly through the 2020 financial year, with the annual rent roll rising 4% to $104 million and the portfolio value increasing 17% to $2.04 billion.

Management pointed to that resilience again in the first half of the 2021 financial year: property revenue rose 2.4% to $47 million, helped by rental growth and a part-year contribution from the new Foodstuffs distribution centre. The airport also noted multiple commercial developments under construction, expected to be valued at more than $223 million on completion with an annualised rent roll of $116 million, and said the commercial property portfolio was valued at around $2.4 billion.

This was the land bank strategy paying out in real time. Logistics tenants kept moving essential goods. Warehousing demand held up. And the value of scarce, well-located industrial land proved far less fragile than passenger volumes.

For investors, COVID validated a core thesis about Auckland Airport: it isn’t only a terminal-and-runway business. It’s also a diversified infrastructure landlord with multiple revenue streams. The crisis still came with real pain—dilution from the capital raise and two years without dividends—but the company made it through with its competitive position intact.

VIII. Recovery and the $6.6 Billion Bet (2022–Present)

The recovery, when it came, didn’t arrive politely. It snapped back.

As New Zealand reopened its borders in 2022, pent-up demand surged through the system. Families who hadn’t seen each other in years booked the first flights they could get. Tourists resurrected long-delayed New Zealand plans. Airlines, short on aircraft and crew, scrambled to rebuild schedules.

The financials reflected the whiplash. Aeronautical revenue more than doubled to $219.5 million. Commercial property revenue climbed 27% to $142.9 million. Retail revenue jumped to $130.9 million, up from $22.7 million the prior year. For the six months ended December, the airport reported an interim underlying profit of $68 million.

But the comeback also exposed how much strain the system had been under. On 27 January 2023, record-breaking rainfall flooded both terminals. Auckland Airport shut down for almost 24 hours, with flights cancelled or diverted and hundreds of travellers stranded. In the wider Auckland region, the flooding killed four people. For the airport, it was a brutal stress test—one that highlighted vulnerabilities in aging infrastructure and brought “resilience” forward from a planning buzzword to an urgent operating reality.

A few weeks later, in March 2023, Auckland Airport announced plans to replace the existing domestic terminal, a project estimated to cost $3.9 billion. The reaction was immediate: airlines raised alarms about the price tag and what it would mean for landing charges and passenger fees.

And the domestic terminal wasn’t a one-off. It sat inside something much bigger: a NZ$6.6 billion aeronautical capital investment programme to reshape the precinct, upgrade core facilities, improve resilience, and add capacity for future growth. The domestic jet terminal was framed as a key piece of the airport’s broader integration programme, spanning the PSE4 and PSE5 periods through to 2032.

Big plans require big funding. So Auckland Airport went back to the equity markets, announcing a NZ$1.4 billion raise: an underwritten NZ$1.2 billion placement, plus a retail offer of up to NZ$200 million. It became the largest follow-on equity offering in New Zealand’s history, with strong participation from both new and existing investors.

Chief Executive Carrie Hurihanganui put the ambition plainly: “As the primary border of Aotearoa New Zealand and gateway to its largest city, Auckland Airport is making a once-in-a-generation investment to be resilient and fit for the future.”

Airlines heard something else: a once-in-a-generation bill.

Both Air New Zealand and Qantas pushed back hard, urging the airport to slow down and redesign the programme around affordability and efficiency. Air New Zealand CEO Greg Foran captured the core critique: “We all agree that some investment in Auckland Airport is necessary. However, this is an enormous spend over a short period of time that adds almost no additional capacity. All it is expected to result in is more costs for everyone who uses, relies on, or passes through the airport.”

Qantas CEO Alan Joyce echoed the same concern, arguing the first phase could be delivered for materially less than the NZ$3.9 billion estimate.

This fight is basically baked into aviation. Airlines live on thin margins in a brutally competitive business, so they treat every additional dollar of airport charges like a direct threat to demand. Airports, by contrast, are monopoly infrastructure operators with long-lived assets and regulated pathways to recover capital over time. When an airport wants to build, airlines want the cheapest possible version of “good enough.” The airport wants something durable, resilient, and future-proof.

For investors, the debate collapses to two questions. Will a NZ$6.6 billion build actually earn an adequate return? And will New Zealand’s regulatory framework ultimately let Auckland Airport recover that investment through higher charges?

IX. Business Model Deep Dive

To really understand Auckland Airport, you have to stop thinking of it as one business. It’s three businesses sitting on the same piece of land—and each one behaves differently when the world gets messy.

Auckland Airport reports three segments: Aeronautical, Retail, and Property.

Aeronautical is the engine room. It’s everything required to move aircraft, passengers, and cargo: the airfield, the terminal facilities airlines rely on, and supporting utility services. This is where landing charges, per-passenger fees, and terminal leases live. It’s also the most tightly scrutinized part of the business, because it’s essential infrastructure and airlines can’t “shop around.”

Retail is what most travelers actually notice: duty-free, terminal stores, and car parking. The airport makes money by charging concession fees to retailers and operating parking. This segment isn’t regulated the way Aeronautical is, but it’s emotionally—and financially—tied to one thing: foot traffic. When international travel booms, retail booms. When the borders close, retail doesn’t gently decline; it vanishes.

Property is the sleeper. It’s leasing space across airport land: cargo buildings, hangars, and stand-alone investment properties. It’s not regulated. And it doesn’t move in lockstep with passenger volumes. A logistics tenant pays rent whether the terminal is packed or empty.

Aeronautical, at roughly 48% of revenue, is still the core. But what makes Auckland Airport particularly interesting is how that core is governed.

Under Part 4 of the Commerce Act 1986, Auckland Airport’s aeronautical activities sit under an information disclosure regime. The point isn’t to micro-manage the airport day-to-day. It’s to force transparency, so the airport has incentives to behave in a way that benefits consumers over the long term. The Commerce Commission monitors performance and price setting, and it assesses whether the information disclosure approach is working as intended.

In practice, aeronautical pricing runs on a five-year cadence. Auckland Airport consults with its major airline customers, sets aeronautical prices for the next period, and then the Commerce Commission reviews the pricing and investment decisions and publishes a report with its conclusions.

That five-year rhythm is the Price Setting Event framework—PSE. It’s a distinctive kind of regulation: the Commerce Commission can’t directly set prices, but it can publicly call out pricing it believes is excessive. And for a company that needs a long-term license to operate—politically and reputationally—that public verdict matters.

For PSE4, updated charges for airlines’ use of the airfield and other essential services were set around a targeted return of 7.82%, down from 8.73%, and described as being within the range the Commerce Commission considered reasonable.

Then there’s Property—the segment that makes Auckland Airport more than a regulated utility. With an investment and development portfolio that exceeds $2.7 billion, the airport has a built-in incentive to keep building high-quality assets and to keep tenants happy over long time horizons. And because this income stream is unregulated and largely insulated from passenger swings, it can stabilize the whole company when aviation doesn’t.

COVID was the proof. Aeronautical and retail revenues collapsed almost overnight, but property income held up—and even grew—providing the cash flow that helped service debt and keep essential operations running. What started as “land we might need later for aviation expansion” turned into a strategic asset in its own right: a second business model sitting inside the same fence line.

X. Porter's Five Forces and Hamilton's Seven Powers

Porter's Five Forces Analysis:

Threat of New Entrants: Extremely Low

Auckland Airport isn’t just an airport. It’s one of New Zealand’s most important infrastructure assets. And the idea of a second, competing major airport for Auckland is, for all practical purposes, fantasy.

To replicate Auckland Airport, you’d need vast amounts of land close enough to the country’s biggest city to actually be useful, plus billions in capital, plus a political and regulatory path through environmental approvals, noise constraints, and community opposition. Even if someone had the money, the odds of getting it built are vanishingly small.

This is natural monopoly territory, in the purest sense.

Bargaining Power of Suppliers: Low to Moderate

The main suppliers here are construction contractors, utility providers, and labor.

Contractors can have leverage during boom periods—especially when the airport is running major projects and the construction market is tight. But that power is cyclical, and Auckland Airport has shown it can pull levers too: staging work, renegotiating, or pausing projects when pricing becomes unattractive.

Bargaining Power of Buyers: Low to Moderate

The buyers are the airlines—especially Air New Zealand, the dominant user, and Jetstar as a major base operator. If an airline wants to serve New Zealand’s largest city, Auckland Airport is the only real option.

But “no alternative” doesn’t mean “no power.” Airlines can coordinate, lobby, and apply pressure through public channels—exactly what’s happening in the dispute over the NZ$6.6 billion capital programme. And New Zealand’s regulatory setup gives those complaints somewhere to land: the Commerce Commission’s oversight, plus the ever-present threat that “light-handed regulation” could become something heavier if the airport is seen to overreach.

So airlines can’t walk away—but they can make noise, and that noise can matter.

Threat of Substitutes: Low (with caveats)

For international travel, there’s essentially no substitute. New Zealand’s geographic isolation makes flying the only practical way to connect with the rest of the world at scale.

Within New Zealand, Christchurch and Wellington serve their own regions and aren’t true substitutes for most travelers whose trip begins or ends in Auckland. Domestic travel does have some substitution from driving, but only at the margin. The trade-off is stark: Auckland to Wellington by car is an all-day haul; by plane it’s roughly an hour.

One modern substitute does exist: video conferencing. COVID accelerated remote work and cut into some business travel. But leisure travel—still a huge portion of passenger volumes—is much harder to replace with a Zoom call.

Industry Rivalry: Non-existent Locally

Auckland Airport handled 71 per cent of New Zealand’s international air passenger arrivals and departures in 2000, and it still dominates international flows. It has no direct local rival. Auckland is effectively a single-airport city for meaningful commercial aviation, and that lack of rivalry is the foundation of the investment case.

Hamilton's Seven Powers Analysis:

Scale Economies

Airports are built on fixed costs: runways, terminals, security systems, airfield infrastructure. Those costs don’t scale down just because demand dips, and they don’t need to double just because volumes grow. The bigger the airport, the more those costs can be spread across millions of passengers—giving large airports a structural advantage that smaller ones can’t easily match.

Network Effects

There aren’t classic “social network” effects here, but there are powerful indirect ones through airline route economics. More passengers make more routes viable. More routes attract more passengers. Auckland’s position as the country’s busiest airport keeps feeding that loop, reinforcing its role as the default hub.

Counter-Positioning

Auckland Airport’s property strategy is a quiet superpower. Airlines can’t replicate it. They don’t own the land surrounding their hubs, and they can’t build a property-and-retail ecosystem that throws off cash independent of flight schedules.

The airport can. That creates a hybrid model—regulated aeronautical revenue at the core, plus unregulated commercial and property income around it—that aviation-only businesses can’t easily counter.

Switching Costs

For airlines, switching costs are effectively infinite because there’s nowhere else to switch to. Route networks, schedules, ground handling, gates, maintenance setups—everything is designed around Auckland. Even in a hypothetical world with a competing airport, moving would be expensive and disruptive. In the real world, it’s not an option.

Branding

Brand power is limited. Passengers don’t choose Auckland Airport the way they choose an airline or a hotel—they choose to go to Auckland, and the airport comes with the decision.

Where branding does matter is at the margin: retail performance, tenant demand, and the willingness of airlines and travelers to view the airport experience as “good enough.” But it’s not the core moat.

Cornered Resource

The most irreplaceable asset is the simplest one: land.

Auckland Airport owns roughly 1,500 hectares of freehold land, including the runway footprint itself. That land bank—assembled over decades when it was cheaper and more available—can’t be recreated in the same location at any realistic price, even if approvals were possible. It’s a cornered resource that underpins both aviation capacity and the entire aerotropolis strategy.

Process Power

Auckland Airport has also built an institutional muscle for operating under scrutiny. On 22 February 2019, after considering the Commerce Commission’s final report on pricing for FY18 to FY22, the airport announced it would reduce prices to airlines by providing discounts for the remainder of the pricing period.

That’s process power in action: knowing how to set prices, how to consult, how to respond to regulators, and how to balance stakeholder pressure—while still protecting the long-term economics of the asset.

XI. Leadership Transition and Strategic Direction

The handover from Adrian Littlewood to Carrie Hurihanganui was more than a routine CEO change. It happened right as Auckland Airport was trying to climb out of COVID, restart growth, and justify the biggest build programme in its history.

Chairman Patrick Strange announced that Hurihanganui would replace Littlewood, who had signaled his departure in May after almost nine years in the role. With the appointment, Auckland Airport got its first female chief executive in its 55-year history—and, just as importantly, a leader who came from the other side of the counter.

Hurihanganui joined Auckland Airport from Air New Zealand, where she had spent 21 years. Most recently she was Chief Operating Officer, responsible for pilots, cabin crew, airports, engineering and maintenance, properties and infrastructure, supply chain, and resourcing. She’d started at the airline in 1999 as an international cabin crew member, then worked her way up through the organisation. US-born, she arrived in the industry on the front line—and rose into the jobs where you learn, in detail, what breaks when the system is under strain.

That background mattered. Her appointment brought deep operational credibility and relationships across the aviation ecosystem. She knew what airlines actually need from airports, what they complain about, and which complaints are real versus tactical. Now she’d be deploying that knowledge on the airport side—still negotiating hard, but with an operator’s instinct for what “good” looks like in day-to-day reality.

Hurihanganui stepped into the role to lead a transformation spanning roughly 400,000 square metres of airfield infrastructure, integrated terminals, and transportation—one of the largest private infrastructure builds in New Zealand.

And she inherited the hardest version of the job: a company still reeling from the pandemic, staring down a once-in-a-generation capital programme, and locked in increasingly public tension with its biggest airline customers. Her airline pedigree may have helped translate across the divide. But it didn’t change the underlying physics of the relationship: airports need to invest for decades; airlines fight for costs they can survive this quarter.

XII. Bull vs. Bear Case

Bull Case:

At its best, Auckland Airport is a way to own the long arc of New Zealand’s connection to the world. Rising Asian middle-class incomes have been a tailwind for tourism for years, global air networks keep expanding, and New Zealand has increasingly positioned itself as a premium, high-value destination. When those forces are working, Auckland is the choke point they all have to pass through.

That’s the core of the bull case: the monopoly is real. There isn’t going to be meaningful competition for Auckland’s international traffic. And while New Zealand’s regulatory framework constrains what the airport can charge, it’s also relatively stable and predictable—often preferable to the kind of ad hoc political interference that can whipsaw airports in other jurisdictions.

Then there’s the asset inside the asset: roughly 1,500 hectares of freehold land. That land bank gives Auckland Airport decades of optionality in property development, and it has already proven itself as a real hedge when aviation turns ugly. There’s still significant capacity left to develop, and the runway can’t be separated from the real estate that surrounds it.

Finally, the airport’s big bet—the new domestic jet terminal and the wider capital programme—has a clear upside if it works. The terminal plan is expected to deliver materially more domestic seat capacity and processing capacity, and it could make it easier for more competition to show up in a domestic aviation market that has historically been among the least competitive in the world. The price tag is heavy, but the payoff is an airport that’s built for decades, not patched for quarters.

And, importantly, the post-COVID rebound reinforces the long-term thesis. Passenger volumes recovered to near pre-pandemic levels, and despite the financial pain of the pandemic years, Auckland Airport came out the other side still holding the same strategic position it started with: New Zealand’s primary gateway.

Bear Case:

The bear case starts with the same $6.6 billion programme the bulls point to. Projects of that size come with real execution risk: cost overruns, delays, and redesigns can chew through returns fast. If the build ends up materially over budget, or takes longer than expected, the economics can get squeezed.

The second risk is the one playing out in public: airlines pushing back. Air New Zealand and Qantas have argued that the higher airport fees needed to fund the investment would make travel less affordable. If that opposition hardens into regulatory intervention or political backlash, Auckland Airport’s ability to earn back its investment through higher charges could be limited—even if the infrastructure is genuinely needed.

Then there’s operational fragility. Auckland still runs on one main runway, which means disruption events hit harder than they would at a multi-runway hub. The January 2023 flooding made that risk feel very real: when the airport closes, the country’s gateway closes with it.

Climate change adds another layer of uncertainty. There’s physical risk to infrastructure—particularly given the airport’s reclaimed-land foundation—and there’s industry risk as emissions concerns and decarbonisation pressures reshape aviation over the long term. Either could weigh on demand growth, or increase the cost of staying resilient.

And finally, there’s the ceiling imposed by New Zealand itself. It’s a small country. Auckland can be an outstanding origin-and-destination gateway, but it can’t become Sydney or Singapore. Geography works both ways: it makes Auckland essential, but it also limits how large the addressable market can ultimately get.

XIII. Key Performance Indicators for Investors

If you’re trying to take the pulse of Auckland Airport as an investment, most of the noise collapses into two signals.

1. Passenger volumes (especially international)

Passenger throughput is the metronome for the whole precinct. When more people move through the terminals, aeronautical revenue rises with them—and retail follows, because duty-free and terminal spending depends on foot traffic.

International passengers matter disproportionately. They tend to attract higher per-passenger charges, and they generally spend more in duty-free than domestic travellers. That’s why Auckland Airport’s monthly passenger statistics are one of the cleanest, fastest reads on momentum: you see demand turning before it shows up in half-year earnings.

The real story sits in the mix. How close are volumes to pre-COVID levels? Is the growth seasonal or structural? And are those international numbers driven by true origin-and-destination travellers, or by transit passengers who are less likely to spend and stick around?

2. Property revenue and occupancy

Property is the stabilizer. It’s the part of the business that can keep paying rent when planes aren’t full, and it’s what turns Auckland Airport from a pure aviation bet into a diversified infrastructure landlord.

So investors watch property revenue growth, occupancy, and the development pipeline. In a downturn, strong occupancy and rental growth can cushion earnings. In a boom, new development and leasing can add an extra layer of upside—because unlike landing charges, property income isn’t regulated in the same way and isn’t constrained by airline negotiations.

XIV. Conclusion: The Gateway Endures

Auckland Airport’s story is, in a lot of ways, the story of New Zealand: a small country at the edge of the world, forced to build infrastructure that’s outsized for its population because the alternative is isolation.

In just a few decades, this place went from dairy farms in Māngere to a runway carved out of a harbour. It went from a government-built utility to a dual-listed public company. It even went through a moment where, on paper, the market said “yes” to a major foreign investor—only for the country to say “not so fast,” and remind everyone that some assets are commercial, but also strategic.

Now the airport is in its next defining act: a NZ$6.6 billion rebuild and integration programme, pushed forward under regulatory scrutiny and in open conflict with its biggest airline customers. It’s the same balancing act Auckland Airport has always lived with—invest for the next generation while keeping today’s users, politicians, and regulators onside—just with bigger stakes and a bigger bill.

For investors, the appeal is almost as clean as the runway lights on a clear night: a true monopoly asset in a stable democracy; regulation that limits pricing but still allows attractive, long-duration returns; and a land bank that turns an “airport” into a much broader business, with cash flows that don’t fully depend on how many people fly this month.

None of that makes it risk-free. This programme has to be executed well. The Commerce Commission and the political system have to keep accepting the logic of cost recovery. Climate resilience has to move from PowerPoint to concrete and drainage. And aviation demand, as COVID reminded everyone, can disappear faster than any spreadsheet ever assumes.

But if you’re looking for the enduring lesson of Auckland Airport, it’s this: the gateway matters. Planes will change, terminals will be rebuilt, and arguments over charges will never end. Yet as long as New Zealand needs to connect with the world, the country’s front door will keep doing what it has always done—quietly concentrating power, cash flow, and national significance on one reclaimed strip at the edge of the harbour.

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music