CapitaLand Ascendas REIT: Singapore's First Industrial REIT Goes Global

I. Introduction: A Thirty-Fold Transformation

Picture Singapore in late 2002. The city-state was still shaking off the Asian Financial Crisis. Across the region, property markets felt bruised. For big, institutional investors, real estate had a reputation problem: hard to value, hard to trade, and full of unpleasant surprises.

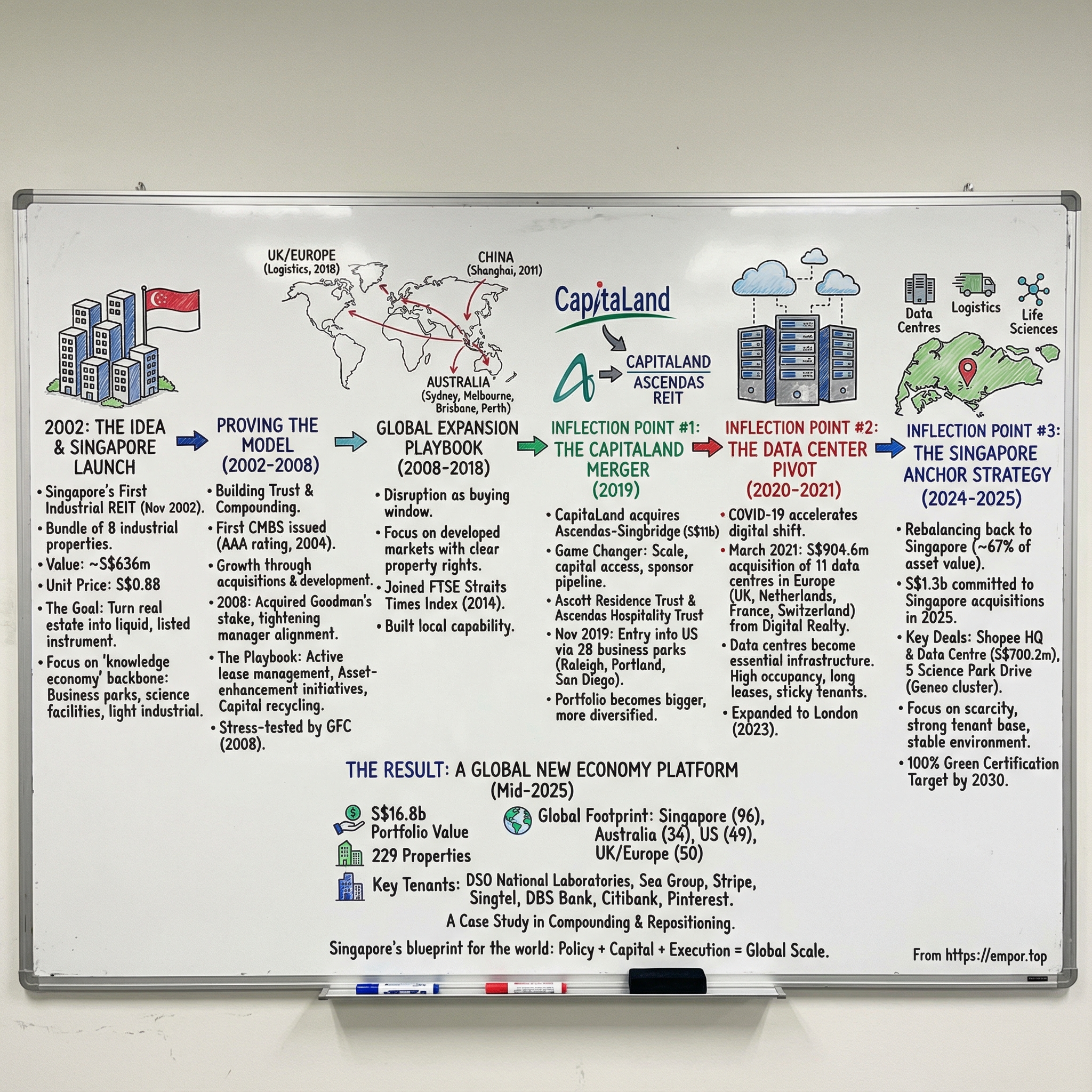

Then, on 19 November 2002, the Singapore Exchange hosted something quietly radical. CapitaLand Ascendas REIT listed on SGX-ST—Singapore’s first listed business space and industrial REIT. Not a flashy tech IPO. Not a consumer brand. Just a bundle of buildings, packaged with a promise: you could own institutional-quality industrial real estate the way you owned shares of a company—liquid, transparent, and built for scale.

At launch, it was small. Eight properties, priced at S$0.88 per unit, with a portfolio worth roughly S$636 million. And the assets weren’t glamorous. They were the physical backbone of Singapore’s next chapter: business parks, science facilities, and light industrial buildings where engineers built products, researchers ran experiments, and manufacturers refined processes. The places where “knowledge economy” stopped being a policy slogan and became square footage.

Now jump to mid-2025, and the before-and-after picture is almost absurd. As at 30 June 2025, investment properties under management stood at S$16.8 billion. The portfolio had grown to 229 properties across three segments: Business Space & Life Sciences; Industrial & Data Centres; and Logistics. And it wasn’t just bigger—it was global. The footprint stretched across four continents, with 96 properties in Singapore, 34 in Australia, 49 in the United States, and 50 in the United Kingdom and Europe.

So here’s the question that drives this story: how did an eight-property REIT worth under S$600 million turn into a roughly S$17 billion platform for technology and logistics?

The answer sits at the intersection of Singapore’s capital-markets innovation, patient deployment of capital, and a manager that kept repositioning the portfolio as the world changed—from traditional manufacturing, to tech ecosystems, to the data-center boom now powering cloud computing and AI.

The tenant list tells you what the buildings have become. Around 1,790 companies across more than 20 industries: data centres, IT, engineering, logistics and supply chain management, biomedical sciences, and financial services. Major tenants include DSO National Laboratories, Sea Group, Stripe, Entserve UK, Singtel, DBS Bank, Seagate Singapore, Citibank, and Pinterest. When your rent roll reads like a map of the modern economy, you’re not just collecting leases—you’re underwriting the infrastructure behind it.

And that’s why this matters beyond one ticker on the SGX. It’s a case study in how a government-linked ecosystem can create a new asset class, how compounding beats theatrics, and why “industrial real estate”—so often dismissed as warehouses and office parks—has quietly become some of the most strategic property on earth.

II. Setting the Stage: Singapore's REIT Revolution

CapitaLand Ascendas REIT didn’t succeed in a vacuum. It was the product of an ecosystem Singapore built on purpose.

In 1999, Singapore moved early. It was among the first jurisdictions to put in place rules that allowed REITs to exist. The Monetary Authority of Singapore wasn’t simply photocopying the American REIT model from 1960. It was trying to solve a very Singaporean problem: how to turn piles of high-quality, rent-producing real estate into something liquid, investable, and scalable.

Because by the late 1990s, the government—through agencies like JTC Corporation—was sitting on enormous portfolios of industrial land and buildings. These were productive assets, but they were stuck on balance sheets: steady income, little flexibility, and no clean way for private capital to participate. At the same time, Singapore wanted to become Asia’s premier financial hub. But compared to markets like London or New York, its capital markets still needed more depth—and more instruments that global investors actually wanted to own.

That’s what the REIT framework was meant to unlock. MAS issued guidelines on property funds in 1999, but the structure didn’t truly become viable until 2001, when the Inland Revenue Authority of Singapore began granting tax transparency to S-REITs on a case-by-case basis. In plain English: the plumbing finally worked well enough for a real listing to happen.

Even then, it wasn’t a smooth debut. In November 2001, CapitaLand tried to launch what would have been Singapore’s first REIT, SingMall Property Trust. The IPO failed. Market conditions were weak, tax incentives were still evolving, and investors weren’t yet trained to think of real estate as a listed, income-focused product. The lesson was simple: a legal framework isn’t a market. You still need the right timing, the right incentives, and the right assets.

The breakthrough came from a different direction: industrial real estate.

In January 2001, Ascendas Pte Ltd was formed through the merger of JTC International’s Business Parks and Facilities Group and Arcasia Land. This was a pivotal step. It combined JTC’s deep industrial-landlord experience—JTC had been developing and managing Singapore’s industrial estates since 1968—with private-sector management capability. The result was an organization that could take industrial assets and package them in a form that institutional investors could evaluate, price, and trust.

And the choice of industrial assets wasn’t accidental. Singapore had spent decades building itself into a manufacturing and logistics hub for Asia. Its industrial infrastructure wasn’t made up of generic sheds. It included business parks with multinational R&D centers, logistics facilities tied into global trade flows, and specialized buildings for precision manufacturing—real estate with sophisticated tenants and predictable income.

Once the first REITs proved the model, momentum followed. Since 2002, REITs grew in popularity as tax transparency improved and regulations were refined. The Singapore government didn’t just regulate from the sidelines; it also participated as an investor through Temasek Holdings and statutory boards such as JTC. That combination mattered: government-linked entities could seed the market with credible assets, while regulatory improvements pulled in private and institutional capital.

Singapore’s first listed REIT, CapitaLand Mall Trust, debuted in 2002, building on the regulatory regime established in 1999. By 31 May 2019, Singapore had grown to 44 REITs and property trusts with a total market capitalisation of over US$73 billion (S$100 billion), with an average dividend yield of 6.5%.

This wasn’t just financial innovation for its own sake. It was capital-markets nation-building: unlock the value trapped in real estate, broaden ownership, and create a funding engine for the next wave of development. In that environment, an industrial REIT like Ascendas didn’t look like an odd experiment. It looked like the obvious next step.

III. The IPO & Early Years: Proving the Model (2002-2008)

When Ascendas REIT came to market in November 2002, it didn’t try to be flashy. The SingMall REIT attempt the year before had shown that Singapore wasn’t going to buy a big story on faith. This time, the pitch was simpler: here are real buildings, with real tenants, throwing off real rent.

On 19 November 2002, Ascendas REIT (as it was then known) listed on SGX-ST as Singapore’s first business space and industrial REIT. The starting line was modest: a portfolio of eight properties worth about S$636 million, offered at S$0.88 per unit.

And those eight properties made a very intentional point about what kind of country Singapore was becoming. These weren’t malls and they weren’t skyline trophies. They were the places where work happened: business parks and science facilities for R&D teams, light industrial buildings for precision manufacturing, and the kinds of functional spaces that plug directly into Singapore’s role as an Asian logistics and production hub. The “unglamorous” label was almost a feature. In exchange for less spectacle, you got stickier tenants and steadier income.

Then the manager started proving it could operate like a grown-up institution, not a newly listed experiment.

In July 2004—less than two years after listing—the REIT issued its first commercial mortgage-backed securities (CMBS), with a AAA rating, for the equivalent of S$300 million in Euros. For a young REIT, this was a statement. It showed the team could tap deep international pools of capital, structure sophisticated financing, and think beyond the local bank market.

That AAA rating mattered even more. In the shadow of the 1997 Asian Financial Crisis, top-tier global credit validation helped reframe the story: this wasn’t risky property paper. It was institutional-grade real estate with credible governance and conservative-enough leverage to earn the market’s trust.

By 2008, the compounding was hard to miss. The portfolio had expanded sharply from the original eight properties, growing through acquisitions, development completions, and the steady lift of built-in rent escalations.

In March 2008, Ascendas acquired Goodman Group’s stake in the REIT and its 40 per cent equity stake in the REIT’s manager, Ascendas-MGM Funds Management Limited. Strategically, this did two things at once. It tightened alignment—more control and clearer accountability at the manager level—and it simplified the shareholder picture by buying out a sophisticated industrial real estate player that could otherwise have remained an awkward partner.

Underneath all of this was the operating system that would define Ascendas REIT’s first decade—and largely still defines it today. Since IPO, the manager expanded assets under management and distributions per unit through three levers: active lease management, asset-enhancement initiatives, and capital recycling. In practice, that meant staying close to tenants and renewals, upgrading buildings to keep them relevant, and selling mature assets to fund the next set of opportunities.

And then came 2008. The Global Financial Crisis was about to stress-test every assumption in global finance. But for a REIT with access to capital, a disciplined playbook, and a willingness to move when others froze, it also set the table for the next phase of growth.

IV. The Global Expansion Playbook: Australia, China, and Beyond (2008-2018)

In the years after the Global Financial Crisis, Ascendas REIT did something that separates great capital allocators from average ones: it treated disruption as a buying window, not a reason to hide. The crisis shook loose assets, reset pricing expectations, and created motivated sellers. But Ascendas didn’t chase everything. It expanded with a clear thesis and a familiar playbook.

The first big step outside Singapore came in China. On 11 February 2011, Ascendas Real Estate Investment Trust agreed to acquire Shanghai (JQ) Investment Holdings Pte. Ltd. from Hyday Holding Ltd. for approximately S$120 million. This was the REIT’s first investment in China, and it entered through a business park property under development in Jinqiao, Shanghai.

What’s striking is what it didn’t do. It didn’t jump into speculative residential, nor did it go hunting for a skyline trophy. Instead, it exported what it already knew how to operate: the business park model—purpose-built space for corporate and industrial tenants—placed in an established industrial zone with access to multinational demand. It was expansion, but on home-field terms.

Australia followed, and the logic there was just as deliberate. Rather than one headline-making acquisition, the REIT built a presence methodically across Sydney, Melbourne, Brisbane, and Perth. The targets were practical, cash-generating properties—logistics and suburban office—chosen for market depth, stability, and a legal environment investors could underwrite with confidence. This wasn’t a shopping spree. It was a system.

By 2014, the market recognized the scale the platform had reached. In June that year, Ascendas REIT became one of the 30 constituent stocks of the FTSE Straits Times Index. That milestone wasn’t just symbolic. Index inclusion tends to bring more liquidity, greater visibility, and automatic demand from passive funds—small mechanics that can meaningfully lower a REIT’s cost of capital over time.

Then came the United Kingdom. In August 2018, the REIT completed its first UK acquisition: a portfolio of 12 logistics properties, and it added further UK logistics assets that year. The timing mattered. E-commerce was pushing logistics demand higher, and modern warehouse supply near major population centers was tight. At the same time, Brexit uncertainty made some owners eager to sell and some buyers hesitant to commit. Ascendas stepped into that uncertainty with a long-term owner’s mindset: if the fundamentals are strong, short-term politics become noise.

Across China, Australia, and the UK, the through-line stayed consistent: focus on developed markets. Singapore, Australia, the UK, and later the US offered clearer property rights, established commercial law, transparent taxation, and deeper capital markets. Over time, the REIT grew into a global platform anchored in Singapore, with a portfolio organized around three segments: Business Space and Life Sciences; Logistics; and Industrial and Data Centres, across developed markets including Singapore, Australia, the United States and the United Kingdom/Europe.

That “developed markets only” lens was a conscious trade-off. It meant giving up the temptation of higher headline yields in more volatile markets in exchange for more predictable cash flows and less exposure to political and currency shocks. Even its China entry, while important, remained comparatively measured.

Of course, buying abroad is the easy part. Operating abroad is the hard part. As the footprint expanded, the manager built local capability rather than trying to run everything from Singapore. Properties in Australia were held through wholly owned subsidiaries and managed by Ascendas Funds Management (Australia) Pty Ltd together with CapitaLand Australia Pty Ltd and third-party managing agents. Properties in the UK/Europe were held through wholly owned subsidiaries and managed by CapitaLand International Management (UK) Ltd together with third-party managing agents. Properties in the US were held through wholly owned subsidiaries and managed by CapitaLand International (USA) LLC together with third-party managing agents.

By 2018, Ascendas REIT had shown that Singapore’s industrial REIT model could travel—and win—outside Singapore. The next major shift wouldn’t come from another new flag on the map. It would come from a change at the top: a corporate transformation that reshaped the sponsor, the pipeline, and the scale of what the platform could become.

V. Inflection Point #1: The CapitaLand-Ascendas Merger (2019)

In January 2019, the center of gravity in Singapore real estate shifted. On 14 January 2019, CapitaLand announced it would acquire Ascendas-Singbridge from Temasek Holdings in an S$11 billion deal. By 30 June 2019, it was done.

To see why this mattered, look at what each side actually owned. CapitaLand was the country’s biggest real estate name by market value, with muscle in retail malls, integrated developments, and residential projects across Asia. Ascendas-Singbridge, meanwhile, held something different: Singapore’s industrial crown jewels. It wasn’t just the REIT. It was the know-how behind business parks, the capability to develop and manage industrial estates, and the deep relationships with the government agencies that shape how industrial land gets planned and allocated.

Put together, the combination was almost too neat. CapitaLand gained exposure to the parts of real estate that were becoming structurally more important—industrial and logistics, and soon, data centres—areas that had been underrepresented in its mix. Ascendas-Singbridge gained the scale, capital access, and geographic reach of one of Asia’s largest real estate platforms. The sponsor behind Ascendas REIT suddenly became much bigger, with a broader pipeline and more ways to finance growth.

And once consolidation started at the top, it didn’t stay there. On 3 July 2019, CapitaLand announced another major combination: Ascott Residence Trust and Ascendas Hospitality Trust would merge, creating Asia’s largest hospitality trust with S$7.6 billion in assets. The message across the market was clear: in REITs, scale isn’t vanity. It’s a weapon—lower unit costs, better financing, and a wider investable universe for institutional capital.

Then came the first visible proof of what a larger sponsor could enable.

On 1 November 2019, Ascendas Funds Management (S) Limited, the manager of Ascendas REIT, announced proposed acquisitions totaling S$1.66 billion: a portfolio of 28 business park properties in the United States, plus two business park properties in Singapore.

For Ascendas REIT, this was a step-change. It wasn’t another bolt-on in a familiar market. It was an entry into the US—via 28 business parks in Raleigh, Portland, and San Diego. The bet was that these weren’t just cities with office space; they were durable innovation ecosystems, anchored by research institutions and dense clusters of established companies, fast-growing challengers, and start-ups.

Just as important was how the deal happened. It showcased the sponsor pipeline in action. Ascendas-Singbridge had bought the US portfolio in September 2018 from Starwood Capital for $871.5 million—months before the CapitaLand acquisition closed. After Ascendas-Singbridge became part of CapitaLand, those assets could be transferred into the REIT.

That’s the flywheel: the sponsor acquires or develops, then sells stabilized assets into the REIT at appropriate valuations. The sponsor recycles capital and crystallizes gains. The REIT gets growth without taking development risk. And unitholders get a repeatable, credible source of acquisitions rather than one-off deal-making.

The portfolio itself was built to make the thesis obvious. The properties were freehold, about 94% occupied on average, and had a weighted average lease expiry of 4.2 years. Tenants included Google, Amazon, and IBM, alongside research universities. In Oregon—home to a surprising concentration of sports footwear R&D—the assets included Nike’s global headquarters and design centres for Adidas and Under Armour.

This wasn’t “industrial” in the old sense of the word. It was business space designed for knowledge work and R&D—exactly the kind of tenant base that tends to stick around, invest in the space, and keep paying through cycles.

By the end of 2019, the platform that started as eight Singapore buildings had a new identity taking shape. The REIT was now tied to a far larger sponsor, with a clearer path to global scale—and with the United States added to its map. The name that would soon follow captured the shift: CapitaLand Ascendas REIT, emerging from the merger era bigger, more diversified, and built for the next wave of industrial real estate.

VI. Inflection Point #2: The Data Center Pivot (2020-2021)

If the CapitaLand deal was about scale, the next move was about relevance.

COVID-19 hit commercial real estate like a stress test. But for the parts of the economy moving online—work, shopping, entertainment, banking—it also pulled the future forward. Data wasn’t just growing; it was exploding. And suddenly, the most important “industrial” buildings weren’t factories or warehouses. They were the facilities that kept the internet running.

In March 2021, Ascendas Funds Management (S) Limited, as manager of Ascendas REIT, announced a proposed acquisition that made the shift unmistakable: a S$904.6 million portfolio of 11 data centres across Europe, bought from subsidiaries of Digital Realty Trust. The assets were spread across four countries—four in the UK, three in the Netherlands, three in France, and one in Switzerland.

The manager’s CEO, William Tay, framed it plainly: “This acquisition gives us a unique opportunity to own a portfolio of well-occupied data centres located across key markets in Europe. It complements our existing data centre portfolio in Singapore and will increase the sector’s contribution to S$1.5 billion or 10% of investment properties under management.”

That quote reads like strategy in one sentence: this wasn’t dipping a toe in. It was building a pillar.

The Digital Realty transaction mattered for three reasons. First, it made the REIT a real participant in data centres, a sector riding structural demand from cloud computing, e-commerce, and increasingly, AI workloads. Second, it delivered instant scale in Europe—something that would have taken years to stitch together one building at a time. Third, the seller itself mattered. Digital Realty is one of the world’s largest data centre operators. Buying from them signaled that these weren’t fringe assets; they were institutional-grade.

Operationally, the portfolio came with the kind of “infrastructure real estate” characteristics investors like. Across the 11 sites, the net lettable area was about 663,000 square feet. The mix included eight triple-net powered shell facilities and three colocation assets. Occupancy was high—97.9%—with 14 customers spanning financial services, telecommunications, IT, retail (including supermarkets), and education.

And the manager didn’t hide the playbook. The point wasn’t just to own these buildings; it was to keep building the category. As Tay put it: “We see good potential in the data centre business and will continue to source and make further acquisitions when the opportunities arise.”

The timing was not subtle. The pandemic had clarified what had previously been a trend: digital infrastructure had become essential infrastructure. The drivers were stacking up fast—cloud adoption, more devices per person, heavier storage needs, and new waves of compute demand from big data analytics, IoT, Industry 4.0, 5G, e-commerce, and streaming.

With the European portfolio included, Ascendas REIT’s footprint rose to 212 properties valued at about S$15.0 billion, spread across Singapore, Australia, the UK/Europe, and the US.

And it didn’t stop in 2021. In 2023, CapitaLand Ascendas REIT expanded further in London, bringing its data centre footprint there to five with the purchase of the 31MW Chess Building data centre from Digital Realty for £125.1 million. The follow-on deal mattered because it confirmed what the 2021 acquisition implied: this was a sustained commitment, not a one-off.

Data centres also changed the nature of the REIT’s “industrial” exposure. These weren’t generic buildings you could swap out at the end of a lease. Data centres come with extreme switching costs—moving critical computing infrastructure is expensive, operationally risky, and disruptive. Leases tend to be longer, escalation clauses are common, and tenants are often enterprise-grade.

In other words, the data centre pivot didn’t just add a new property type. It positioned the platform right at the intersection of real estate and the digital economy—an intersection that barely existed when the REIT listed in 2002, but now sits at the heart of where commercial real estate growth has been heading.

VII. Inflection Point #3: The Singapore Anchor Strategy (2024-2025)

After years of pushing outward—into Australia, Europe, and the US—2024 and 2025 brought a deliberate rebalancing back toward Singapore. This wasn’t a retreat from being global. It was a recognition that, even with a tougher macro backdrop, the home market was offering the kind of risk-adjusted returns worth leaning into.

Singapore became the portfolio’s anchor, representing about 67% of asset value. And the way CLAR anchored wasn’t by buying “safe” for the sake of it. The focus was on the same new-economy engine rooms the REIT had been building globally: business space, logistics, and especially data centres.

In 2025, CLAR accelerated that push. It announced DPU-accretive acquisitions of three fully occupied industrial and logistics assets for S$565.8 million, and in total committed about S$1.3 billion to Singapore acquisitions that year—the largest annual home-market investment since the REIT’s early days.

The headline deals captured the strategy in one shot. CapitaLand Ascendas REIT agreed to buy the headquarters building of e-commerce player Shopee and a co-location data centre for a combined S$700.2 million, acquiring both from private trusts held by Temasek-owned CapitaLand Group. The Shopee head office at 5 Science Park Drive in Queenstown was valued at S$245 million, while the data centre at 9 Tai Seng Drive in Hougang was valued at S$455.2 million.

By the third quarter, the REIT had completed acquisitions including a premium business space at 5 Science Park Drive and a Tier III colocation data centre at 9 Tai Seng Drive. Both were fully occupied, and the manager highlighted their attractive income profiles, with NPI yields of 6.1% and 7.2% respectively.

But the Science Park angle ran deeper than a single building. CLAR and joint venture partner CapitaLand Development completed the redevelopment of 1 Science Park Drive in the first half of 2025, at a total development cost of about S$883 million. Located within the Geneo life sciences and innovation cluster near Kent Ridge MRT station, the premium business space and life sciences property drew strong leasing demand: about 95% of its net lettable area of 103,200 square metres (1.1 million square feet) was either committed or in advanced negotiations.

Geneo matters because it reflects where “industrial” real estate has been heading for years. It’s not just square footage. It’s infrastructure for specific kinds of work—wet-lab ready space for life sciences, high-quality offices for innovation and tech tenants, and the amenities that make these campuses function like ecosystems. Owning multiple assets in the same cluster gives CLAR a compounding advantage as the area attracts more high-value tenants.

On the data centre side, the thesis was also clear: scarcity. CLAR’s group CEO, Natarajan, pointed to “good upside potential” in these assets, noting that in-place rental was about 30% below market. He also cited a tight vacancy rate of around 2% and a limited supply pipeline as reasons rent growth could continue.

That supply constraint wasn’t accidental—it was regulatory. Since 2019, Singapore has limited the development of new data centres through a moratorium, driven by concerns including environmental sustainability and energy consumption. Data centres accounted for about 7% of Singapore’s total electricity consumption in 2020. The result was a rare dynamic: demand kept rising, while new supply was administratively capped. For owners of existing, well-located facilities, that imbalance translated into pricing power.

As William Tay, CEO and executive director of the REIT’s manager, put it: “CLAR continues to strengthen its presence in Singapore with a total investment of approximately S$1.3 billion in 2025.”

Stepping back, the Singapore anchor strategy was really a return to first principles. Keep global diversification—but concentrate new capital where the rule of law is strong, the tenant base is sophisticated, the currency is stable, and barriers to new supply are real. In a world where “industrial” increasingly means life sciences and digital infrastructure, Singapore wasn’t just home. It was, once again, a competitive edge.

VIII. The Tenant Roster: A Who's Who of the New Economy

If you want to understand what CLAR has actually become, don’t start with the property count. Start with the names on the doors.

Major tenants include DSO National Laboratories, Sea Group, Stripe, Entserve UK, Singtel, DBS Bank, Seagate Singapore, Citibank, and Pinterest. That list is a kind of shorthand for the portfolio’s positioning: a blend of government and critical infrastructure, global finance, and the companies building the digital economy.

The range is the point. DSO National Laboratories is Singapore’s defence research agency, the sort of tenant that doesn’t just pay rent—it signals stability. Sea Group, the parent of Shopee and Garena, is a homegrown tech champion with real headcount and real operating needs. Stripe brings the world of private-market fintech. Pinterest represents global consumer internet. Then you’ve got anchors like DBS and Citibank, and essential connectivity via Singtel. This isn’t one industry riding one cycle. It’s a cross-section of the modern economy.

Zoom out, and the underlying structure shows up in the stats. The portfolio’s weighted average lease expiry is 3.7 years, and the customer base runs to about 1,790 tenants across more than 20 industries. That scale matters because it changes the risk profile. Many office portfolios live and die by a few large leases. CLAR’s industrial and business space footprint, by design, spreads exposure across hundreds of tenants. Any single move-out hurts, but it doesn’t define the story.

Yes, managing that many relationships is more complex. But it also creates the kind of income resilience investors pay for, especially when the economy turns. Diversification isn’t just geographic for CLAR; it’s built into the rent roll.

And the mix of sectors isn’t accidental. Technology, life sciences, logistics, and financial services are where secular growth has been strongest—and where physical space is still non-negotiable. You can shrink an office footprint. You can’t “remote work” a data centre. You can’t run a biotech lab out of a generic unit. The more specialised the facility, the higher the switching costs, and the stickier the tenant.

Take Shopee at 5 Science Park Drive. A headquarters is not a month-to-month decision. It’s staff, systems, fit-out, brand presence, and operational coordination. Moving is disruptive and expensive, which is exactly why these leases tend to behave differently from more commoditised space. For CLAR unitholders, that stickiness shows up as more predictable cash flow.

Finally, there’s a quieter advantage in having a portfolio that spans multiple developed markets. When a tenant operates across regions, the manager isn’t just collecting rent on one building—it has the opportunity to become a longer-term partner across locations. That deepens relationships, reduces churn, and turns a set of assets into something closer to a platform.

IX. The Sustainability & ESG Transformation

Sustainability credentials have shifted from a nice-to-have to a gatekeeper. For a REIT that wants deep, global pools of capital—and wants to keep tenants happy—ESG isn’t a side program anymore. It’s becoming part of the operating system.

CLAR’s credentials show how far that shift has gone. About 61% of the portfolio was green-certified, up from 49%. It held a four-star GRESB rating, earned an MSCI ESG rating of ‘AA’ for the third year, and placed second in the Singapore Governance & Transparency Index for REITs/Trusts.

The ambition is even clearer: CLAR targeted 100% green certification by 2030. This wasn’t just a slide-deck pledge. The REIT installed solar panels across 29 Singapore properties, generating 28GWh annually—enough to power over 6,100 households. And it backed the strategy with its balance sheet: green financing made up 44% of total borrowings, aligning how it raised money with how it intended to run the portfolio.

That 2030 target also changed decision-making. Sustainability standards moved from “we’ll upgrade later” to “this is part of the requirement.” Major acquisitions were evaluated with green building expectations in mind, and asset-enhancement initiatives increasingly bundled in improvements that cut energy use while making buildings more attractive to tenants.

The financing angle is where ESG becomes concrete. CLAR raised S$1.0 billion in new funding, including S$700 million of 7-year green notes at a 2.343% coupon and S$300 million of perpetual securities at 3.18%. In a sector where a small difference in funding costs can materially affect returns, access to green capital markets isn’t just reputational—it can be strategic.

That advantage is getting more valuable over time. Green bonds and sustainability-linked loans can come with pricing benefits, because a growing set of lenders and bond investors want, or are mandated, to allocate capital to assets that meet ESG criteria. For CLAR, that can translate into a cost-of-capital edge over peers without comparable credentials.

The external validation continued in 2024. CLAR maintained its four-star rating and achieved a GRESB Public Disclosure Level of ‘A’ for the fifth consecutive year in the 2024 GRESB Real Estate Assessment. It was also included in the FTSE4Good Developed Index and the FTSE4Good ASEAN 5 Index effective December 2024.

That kind of index inclusion matters for a simple reason: it can expand the buyer base. ESG-focused funds that track FTSE4Good indices can only invest in constituents. So inclusion doesn’t just signal “good governance”—it can unlock access to capital that otherwise wouldn’t be available, regardless of how attractive the yield looks.

Stepping back, this ESG push mirrors a broader reordering in institutional investing. Pension funds, sovereign wealth funds, and insurers increasingly require ESG compliance for holdings. CLAR’s approach—greener buildings, measurable upgrades, and financing that matches the narrative—helps ensure it stays investable as those standards tighten.

X. The Industrial REIT Business Model Playbook

To understand how CLAR compounded for more than two decades, you have to understand what an industrial REIT manager actually does. The best ones aren’t passive landlords. They’re operators and capital allocators. And the model tends to run on four interlocking gears.

Active Asset Management: This goes far beyond collecting rent. The manager stays close to tenants, tracks what the market is paying, and keeps upgrading assets so they stay relevant. In 2025, that showed up in a burst of acquisitions in Singapore—about S$1.3 billion into five properties—alongside redevelopment work like 5 Toh Guan Road East, where a S$107.4 million project increased gross floor area by 71%.

That 5 Toh Guan Road East expansion is the simplest way to see the value-creation logic. Instead of buying new land at today’s prices, you extract more value out of what you already own—intensify, modernize, improve specifications, and reposition the building for higher-value demand. Done well, asset enhancement can deliver returns that beat what you’d get by simply acquiring stabilized buildings in the open market.

Capital Recycling: While upgrading and buying, the manager is also selling—because the portfolio is a living thing, not a museum. CLAR executed S$381.5 million of divestments at meaningful premiums, freeing up capital for newer assets with better growth profiles.

The basic idea is straightforward: sell what’s fully priced, redeploy into what offers better income and upside. If you can exit a mature asset at a low yield and move that capital into something higher-yielding, you can lift distributions while keeping the overall portfolio engine running.

Sponsor Pipeline: The CapitaLand relationship adds a structural advantage. The sponsor can develop or acquire assets, stabilize them, then offer them to CLAR at arm’s-length valuations. That’s very different from relying on auctions, where the “winner” is often the bidder who got the most aggressive. A sponsor pipeline doesn’t eliminate discipline, but it can create a steadier, more repeatable path to growth.

Balance Sheet Discipline: None of the above works if financing breaks. CLAR managed its leverage at 39.8%, kept interest coverage at 3.6x, and held a high proportion of fixed-rate debt (77.6%), limiting exposure to rate shocks.

That conservatism is what gives a REIT options. When markets seize up, the players with flexible balance sheets can buy, upgrade, and refinance from a position of strength—while over-levered vehicles are forced into defensive moves.

XI. Porter's Five Forces Analysis

Threat of New Entrants: LOW

Industrial REITs aren’t easy to break into, especially in Singapore. To be taken seriously, a new entrant needs a meaningful starting portfolio—enough assets to spread operating costs, attract institutional capital, and compete for tenants. On top of that, Singapore’s REIT regime isn’t built for amateurs: sponsors and managers are expected to have real track records and capabilities.

But the biggest barrier is something no competitor can “fundraise” their way around: land. Singapore is land-scarce by design, and industrial land supply is tightly managed. When supply comes in lower than expected, it supports rental growth for existing portfolios. That scarcity acts like a moat—one that makes it structurally hard for new players to scale into CLAR’s territory.

Bargaining Power of Suppliers: MODERATE

On most inputs, CLAR has options. Construction contractors and property management providers operate in relatively fragmented markets, and the REIT can switch vendors without fundamentally jeopardizing the portfolio.

Land is the exception—and it’s the most important exception. In Singapore, industrial land allocation is controlled by the government, largely through JTC Corporation. That gives a single “supplier” meaningful influence over the critical raw material for future development and expansion.

Bargaining Power of Buyers (Tenants): MODERATE

Tenants aren’t all created equal. Large technology tenants often have sophisticated real estate teams, global footprints, and credible alternatives—so they can negotiate hard. Smaller industrial tenants typically have fewer options, and their bargaining power is more limited.

And then there are the assets that change the dynamics entirely. Data centres, life sciences space, and other highly specialized facilities are not plug-and-play. Once a tenant has invested in fit-outs and operational infrastructure, moving becomes expensive, risky, and disruptive. That “stickiness” shifts leverage back toward the landlord.

Threat of Substitutes: LOW

Industrial real estate has a simple advantage: it’s physical. Warehouses, data centres, and labs do jobs that can’t be replaced by software or remote work policies. The work-from-home wave rattled traditional offices, but it doesn’t eliminate the need to store inventory, run servers, or operate research facilities.

If anything, the digitization of everything has raised demand for the backbone: logistics networks and digital infrastructure that still require real buildings in real locations.

Competitive Rivalry: HIGH

This is a crowded, competitive space, with strong rivals like Mapletree Industrial Trust and Keppel DC REIT, alongside other well-capitalized industrial REITs with serious sponsors. Competition shows up most clearly in acquisitions: more bidders can push prices up and squeeze yields down.

CLAR’s counterweight is scale. Size helps in the places that matter—tenant relationships, operating leverage, and cheaper access to capital. It doesn’t eliminate competition, but it can soften the impact and keep the flywheel turning even when the market gets aggressive.

XII. Hamilton's Seven Powers Analysis

Scale Economies: STRONG

CapitaLand Ascendas REIT (formerly Ascendas REIT) is Singapore’s first and largest listed business space and industrial REIT on SGX-ST. That size is not just a bragging right; it shows up in the mechanics. With 229 properties, the platform can spread property management and operating costs across a wider base, so the “overhead per building” tends to fall as the portfolio grows.

Scale also buys financial advantages. Larger, established REITs generally have an easier time securing cheaper funding, helped by investment-grade credit profiles that smaller competitors often struggle to match. Over time, that difference in financing cost can compound into a real edge in what CLAR can afford to buy, and how resilient it stays through rate cycles.

Network Effects: MODERATE

Real estate doesn’t have network effects in the same way a software platform does, but clustering still matters. Technology and life sciences companies often want to be near other similar tenants because it helps with hiring, partnerships, and staying plugged into an ecosystem.

Singapore Science Park is the clearest example: once an innovation district forms, it can attract more innovation. Still, these effects are meaningful but limited. Industrial and business space wins more on location, specifications, and economics than on pure “user growth.”

Counter-Positioning: STRONG

As Singapore’s first industrial REIT, CLAR helped write the local playbook before most peers had even picked up the pen. More importantly, it repositioned over time toward the “new economy” mix—data centres, life sciences, and technology-oriented business space—rather than staying concentrated in traditional manufacturing and generic industrial stock.

Competitors can pivot, but late pivots are harder. Building the sourcing network, operational know-how, and tenant relationships in specialised segments takes time. CLAR had two decades to refine that muscle while others were still optimizing for an older definition of “industrial.”

Switching Costs: MODERATE-HIGH

Switching costs are where parts of the portfolio behave less like ordinary buildings and more like infrastructure. Data centres are the extreme case: moving computing equipment is expensive, risky, and disruptive, so tenants avoid relocation unless they have to. Science parks and life sciences facilities also come with tenant-specific fit-outs and specialised requirements that don’t transfer neatly to a generic alternative.

Layer on the portfolio’s long lease structure, with a weighted average lease expiry of 3.7 years, and you get a form of built-in stickiness. Those frictions tend to support stable occupancy—and give landlords more leverage when leases roll.

Branding: MODERATE

In REITs, brand isn’t about consumer recognition. It’s about credibility with capital providers. CLAR has an issuer rating of ‘A3’ by Moody’s Investors Service, and it sits in major indices including the FTSE Straits Times Index, MSCI Index, EPRA/NAREIT Global Real Estate Index, the GPR Asia 250 Index, and the FTSE4Good Developed Index.

That “blue-chip” status matters because it broadens the investor base, supports liquidity, and can lower the cost of capital. In a sector where growth often comes through acquisitions, trust and financing access are competitive weapons.

Cornered Resource: STRONG

Singapore’s scarcest input is the one that matters most: land. The city-state can’t expand outward in any meaningful way, and industrial land use is tightly controlled. That makes prime business park and science park locations difficult to reproduce, regardless of how much money a new entrant raises.

CLAR’s existing Singapore holdings therefore aren’t just assets; they’re positions. Once you own scarce, well-located space in a constrained market, it becomes a durable advantage that’s hard to copy.

Process Power: MODERATE

A lot of CLAR’s performance comes from craft: active lease management, asset enhancement, and capital recycling—doing the unglamorous work of keeping buildings relevant, tenants sticky, and capital continually redeployed into higher-potential opportunities.

That operating system is valuable because it’s accumulated knowledge, built across cycles and across geographies. But it’s not magical. A well-resourced competitor can replicate pieces of it over time, which is why this power is real—but not unassailable.

XIII. Key Performance Indicators for Investors

If you want a quick, repeatable way to track how CLAR is doing, three indicators do most of the work:

Distribution Per Unit (DPU) Growth: This is the clearest scoreboard for unitholders—what you actually receive. In FY 2024, DPU inched up 0.3% year-on-year to 15.205 Singapore cents, supported by the full-year contribution from properties acquired and completed in FY 2023 and steady operational performance across the portfolio. The important point isn’t any single year’s bump; it’s whether the manager can keep growing distributions through smart acquisitions, disciplined financing, and active asset management.

Rental Reversion Rate: This tells you what happens when leases roll: can the REIT reprice space up, or is it giving back rent to keep tenants? In FY 2024, portfolio occupancy stayed healthy at 92.8%, and renewed leases achieved a positive average rental reversion of 11.6%. When reversions are meaningfully positive, it usually means market rents are running ahead of in-place rents—an early signal of pricing power and portfolio relevance.

Aggregate Leverage: This is the constraint that sits behind everything else. CLAR’s aggregate leverage was 39.8%—high enough to support growth, but still comfortably below MAS’s 50% regulatory limit. That headroom matters because it preserves flexibility: the ability to act on acquisitions without stretching the balance sheet so far that the cost of capital starts doing damage.

XIV. Bull and Bear Cases

The Bull Case

The biggest argument for CLAR is that it sits directly in the slipstream of the modern economy. Data centres, logistics, and life sciences aren’t cyclical fads; they’re long-duration trends. Cloud adoption keeps climbing. E-commerce still has runway across Southeast Asia. AI is turning “more data” into “a lot more data,” and that translates into real, physical demand for computing infrastructure.

Singapore adds a second layer to the bull case: it’s a place where constraints are real. Land is scarce, approvals are tight, and tenant quality is unusually high. CLAR’s Singapore anchor strategy leans into that. The roughly S$1.3 billion committed to Singapore acquisitions in 2025 was designed to bring in immediate income from fully leased assets, while preserving upside as in-place rents reprice closer to market over time.

Then there’s the sponsor flywheel. With CapitaLand behind it, CLAR has better visibility into potential acquisitions than a REIT that has to fight every deal in open auctions. Layer on the 100% green certification target by 2030, and you can see the capital-markets angle too: staying eligible for ESG-focused pools of capital as sustainability screens tighten. Finally, the balance sheet discipline matters in a simple way—when markets get messy, the player with flexibility gets options.

The Bear Case

The most obvious risk is still the blunt one: interest rates. Even with most debt hedged to fixed rates, higher-for-longer rates can raise refinancing costs and push down property valuations. The 2022 to 2024 hiking cycle showed how quickly REIT unit prices can reset when the discount rate moves.

Diversification brings its own trade-offs. Owning assets across the US, UK/Europe, and Australia creates currency exposure, and a stronger Singapore dollar can dilute overseas returns when translated back into the reporting currency. If the Singapore dollar keeps strengthening against the USD, GBP, and AUD, foreign assets can become a drag even if they perform well locally.

Data centres are also getting more competitive globally. New supply—especially in parts of the US—can pressure occupancy and rents. And the risk isn’t theoretical: even strong players in the space have felt it. Mapletree Industrial Trust, for example, faced notable headwinds, and JP Morgan analysts downgraded it from ‘Overweight’ to ‘Underweight’ in February 2025, citing concerns about tenant vacancies in its US data centre portfolio.

Finally, there’s a structural issue shared by all externally managed REITs. The manager earns fees based on assets under management, which can create an incentive to grow for the sake of growth. CLAR has maintained a strong governance reputation, but the underlying tension remains part of the model—and investors have to underwrite that along with the real estate.

XV. Conclusion: Singapore's Blueprint for the World

CapitaLand Ascendas REIT’s journey—from an eight-property portfolio worth S$545 million to a roughly S$17 billion global platform across four continents—is more than a corporate growth story. It’s a case study in what happens when policy, capital, and execution line up over decades.

Singapore’s REIT framework, pioneered in the late 1990s and refined over time, didn’t just create a new listing category. It created a new kind of investor product: real estate that could be owned, traded, financed, and scaled like a public company. Other markets across Asia went on to develop similar structures—Japan, Hong Kong, Malaysia, and Thailand among them—but CLAR was one of the clearest proofs that the model worked, and that industrial real estate could be institutional, liquid, and investable. It also proved something less obvious: scale isn’t just size. In REITs, scale can translate into lower funding costs, better operating leverage, and a deeper ability to keep upgrading the portfolio as the economy changes.

None of this means the road ahead is frictionless. Interest rates have stayed high by historical standards, and that pressure shows up first in refinancing costs and valuations. A global footprint brings real complexity and currency exposure. Competition for high-quality assets remains intense as more institutional capital targets the same themes—logistics, life sciences, and digital infrastructure. And even data centres, despite their structural tailwinds, aren’t immune to cycles in hyperscaler spending or shifts in technology and power constraints.

But the core proposition still holds: CLAR owns essential infrastructure. Not just “industrial buildings,” but the places where the modern economy physically happens—where R&D teams build, where supply chains move, and where servers turn electricity into computation.

That’s why, for investors looking for liquid exposure to long-running trends—Asia’s continued development, the global logistics build-out, and the growth in data and compute demand—CLAR stands out as a diversified vehicle with a multi-decade operating track record. The manager’s playbook has stayed consistent: disciplined acquisitions, active asset management, and a conservative-enough balance sheet to keep options open when cycles turn.

In the end, the story of Singapore’s first industrial REIT is a story about compounding. Not only in distributions, but in capability—sourcing, operating, financing, and continuously repositioning a portfolio for what the world needs next. And that compounding continues, every day, across 229 properties on four continents, housing the enterprises building the future economy.

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music