Nitori Holdings: Japan's Furniture Empire and the "IKEA of Japan"

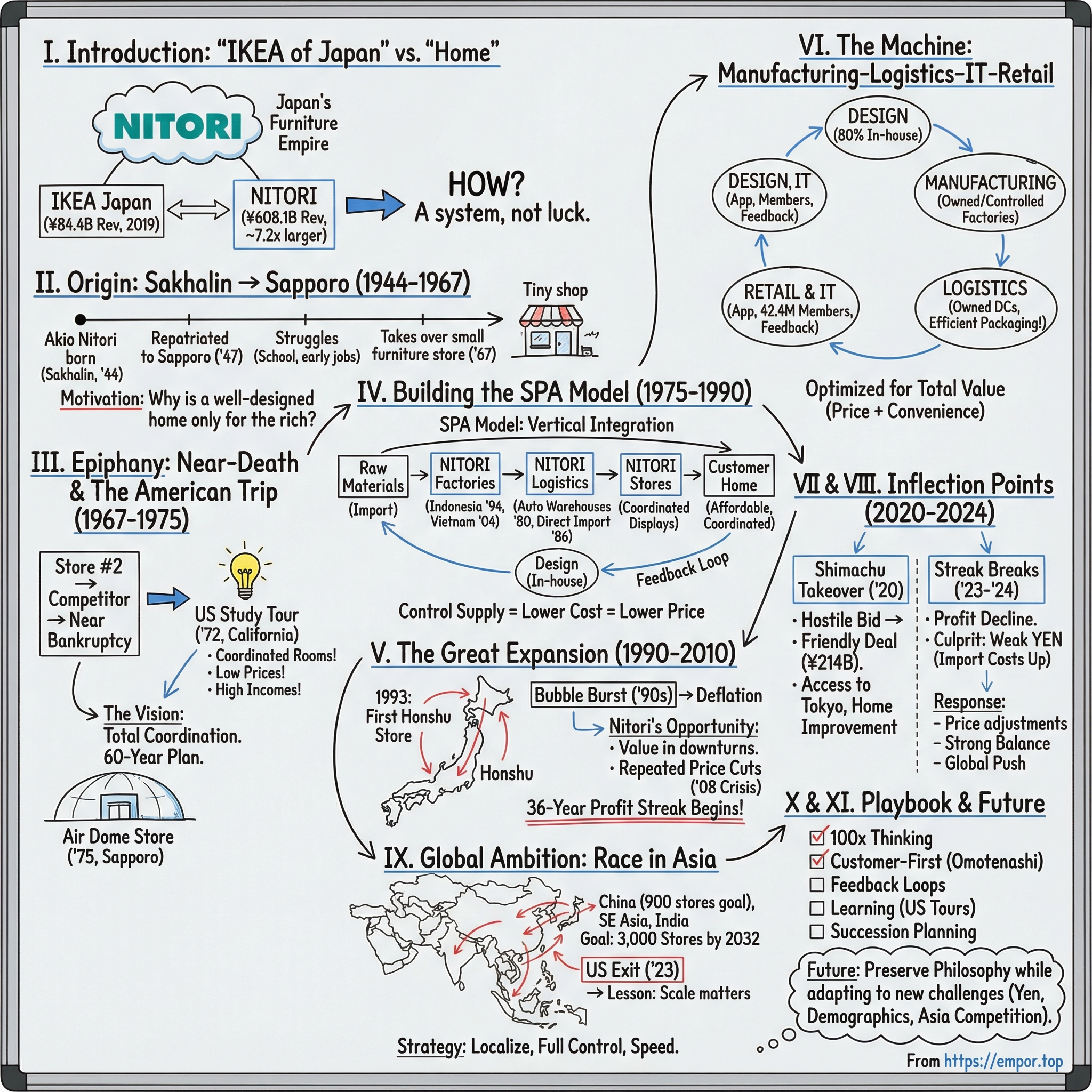

I. Introduction and Episode Roadmap

On a December morning in 1975, a giant air dome rose over a bare, snowy lot on the outskirts of Sapporo. Step inside and it didn’t feel like a furniture store. It felt like a home.

Living room sets were staged as complete rooms, not a scatter of unrelated pieces. Sofas didn’t just sit next to curtains; they matched them. Rugs harmonized with shelving. And then came the real surprise: the prices were within reach of ordinary Japanese families.

The person orchestrating this was Akio Nitori, a former advertising agency employee with no formal retail training and a stubborn obsession with one question: why should a well-designed home be something only rich people can afford?

Fast forward fifty years and that obsession has become a machine. Nitori operates more than 1,000 stores across Japan, China, Taiwan, Southeast Asia, and the United States, generating over $6 billion in annual revenue. In many Japanese households, “go to Nitori” isn’t a suggestion. It’s the default setting for furnishing an apartment.

But the most revealing comparison is the one people love to make: “the IKEA of Japan.” In 2019, IKEA Japan brought in 84.4 billion yen in revenue. Nitori did 608.1 billion yen—about 7.2 times larger. That gap forces the real question to the surface: how did a small, struggling furniture shop on Japan’s northern frontier—run by a man who later admitted he “constantly thought about running away or committing suicide” during the early years—end up building the country’s dominant home-furnishings empire?

For decades, Nitori’s story looked like a straight line up: revenue and profit increased for 36 consecutive periods, fueled by a philosophy of investing aggressively and improving relentlessly. Through recessions, currency swings, and global shocks, the streak held. Not because the company got lucky, but because it engineered an operating system.

That operating system is what this story is really about: vertical integration as a moat, the ability to learn from foreign models and adapt them to Japanese reality, a founder’s vision sustained over six decades—and, more recently, the challenge of keeping momentum when the streak finally breaks.

And it starts where it has to start: with Akio Nitori himself, a man who struggled in school and stumbled early in business, then turned those failures into the raw material for one of Japan’s most unlikely retail victories.

II. The Founder's Origin: From Sakhalin to Sapporo

Akio Nitori’s story doesn’t start in Tokyo, or even on Japan’s main island. It starts on Sakhalin—an icy, contested stretch of the North Pacific that, in the 20th century, bounced between Japanese and Russian control. Nitori was born there on March 5, 1944. A year later, the war ended, the Soviet Union invaded, and his family became part of the great postwar uprooting.

By the time he was three, they had been repatriated to Sapporo, in Hokkaido. The family lived a frugal life. His father, Yoshio Nitori, ran a concrete manufacturing business that kept them afloat, but just barely. For Akio, childhood wasn’t nostalgic. It was formative.

In his own words: “I was repatriated to Sapporo when I was three years old. My childhood was a hand-to-mouth life, living in a unit house for repatriates and helping with the housework. I always struggled with academia, from elementary school to university.”

That wasn’t some polished founder mythology. It was his baseline. He graduated from Hokkai-Gakuen University with a degree in economics in 1966, but his early working life didn’t look like the resume of a future retail titan. He landed a job at an advertising agency, failed to bring in clients, and was fired after six months. He then drifted back into his father’s construction company—until a construction site burned down and work dried up there too.

Furniture wasn’t a calling. It was the option left on the table.

In 1967, he took over a small furniture store that was already flirting with bankruptcy. That struggling shop would eventually become Nitori Holdings—Japan’s largest furniture and home-furnishings chain—but at the time, there was nothing inevitable about it. Nitori wasn’t trained for retail. He didn’t have a playbook. What he did have was a particular kind of pressure: the need to make something work, fast.

And he had an obsession that started to harden into a philosophy—an obsession with why things cost what they cost, how they moved, and why most furniture stores didn’t seem to help people build a coherent home.

The first shop was tiny, roughly 1,000 square feet, serving local customers in Sapporo—Japan’s fourth-largest city, but still far from the country’s economic center. To see why that mattered, you have to understand Hokkaido. It’s geographically separated from the mainland, brutal in winter, and historically treated as the edge of the map. Building a national retail business from Sapporo instead of Tokyo or Osaka was like trying to create America’s biggest furniture chain out of Alaska. Everything is farther. Shipping is harder. Scale is less forgiving.

But that isolation also did something important: it forced a certain kind of thinking. If you can’t depend on being close to suppliers, you start dreaming about controlling supply. If your local market isn’t big enough to save you, you start planning for scale before you deserve it. What looked like a disadvantage became a crucible.

Years later, in 2018, Nitori publicly disclosed that he had been diagnosed with ADHD. In retrospect, it fit the pattern: restless energy, unconventional instincts, and a refusal to accept the industry’s assumptions as fixed laws.

His personality would become inseparable from the company’s. Scarcity drove him. Geography shaped him. And he couldn’t shake the belief that Japanese consumers shouldn’t have to settle for less than what he’d seen promised in the West.

But before any of that turned into an empire, he first had to survive. And to survive, he was going to need a breakthrough—one that would come after the business nearly broke him.

III. Near-Death Experience and The American Epiphany (1967-1975)

Nitori’s earliest years fell into a rhythm that would define Akio’s entire career: a burst of progress, a near-catastrophe, then a reinvention that changed the trajectory.

After the first small shop found a little traction, Akio and his wife, Momoyo, did what ambitious retailers do. They expanded. Store #2 was roughly eight times the size of the original—big enough to feel like a statement, and big enough to strain everything behind the scenes.

Then the market punched back. A competitor opened nearby with a store about five times the size of Nitori’s new location. Sales collapsed. Banks stopped extending credit. The business slid back to the edge of bankruptcy. Looking back, Akio would say he “constantly thought about running away or committing suicide.”

It wasn’t entrepreneurial melodrama. In Japan, business failure didn’t just mean a closed storefront; it could mean shame that stuck to your name and your family. The pressure wasn’t only financial. It was personal, social, and suffocating.

And then, right at the low point, a door opened.

A furniture industry consultant contacted Akio about attending a seminar in the United States. He found a way to borrow still more money to go. On paper, it was insane: take on more debt when creditors were already watching. In reality, it was the most important bet of his life.

In 1972, Akio was 27 years old, running two furniture stores on Hokkaido, and he joined a weeklong study tour in California organized by an industry association. What he saw didn’t just surprise him. It rewired him.

California homes were spacious in a way Japan’s weren’t—multiple bathrooms, separate rooms for guests and family, even backyard swimming pools. But the bigger shock was inside the stores. Americans didn’t buy furniture as isolated objects. They bought a living space. Curtains, carpets, bedding, and interior goods sat alongside sofas, beds, and dining tables, all coordinated in color and style, displayed like real rooms you could imagine yourself living in.

And the pricing made no sense—at least, not through the lens of Japanese retail. American incomes were about three times higher than Japan’s at the time, yet furniture prices were roughly one-third of what Japanese customers paid.

That paradox—richer customers, cheaper products—blew up the industry’s excuses back home. Akio realized the difference wasn’t taste or geography. It was structure. In the U.S., massive chain retailers had scale. They ran modern merchandising. They moved volume. They weren’t trapped in Japan’s fragmented system of wholesalers and one-off assortments.

He visited major retailers like Sears and JCPenney and came back fixated on one idea: total coordination. Don’t just sell a sofa. Sell the room.

Later, Nitori would describe this as the true starting point of the company we know today: the moment Akio understood that products that genuinely improved everyday life could be sold for a fraction of Japan’s prices—and that making that possible for ordinary families could be the cornerstone of an entire business model.

When he returned in 1972, he did something that sounds impossible given how close he’d been to collapse: he started thinking in decades. He calculated that it took America around 120 years to develop its retail industry, and guessed it might take him 60 to catch up. So he sketched a plan with a six-decade horizon—one he would keep refining for the rest of his career.

Most founders staring at bankruptcy are trying to survive the next month. Akio was trying to compress a century of retail evolution into a single lifetime.

The learning didn’t stop with that first trip. In 1978, he joined the Pegasus Club, a chain store study group sponsored by Shunichi Atsumi. Pegasus gave him language, frameworks, and a peer network to study modern retail management—tools he would adapt, test, and turn into Nitori’s own operating discipline.

But the first physical proof that the company was changing showed up before that, back in Sapporo. In December 1975, Nitori opened the Nango Store, Japan’s first furniture store built with an air dome structure. It wasn’t just a quirky building choice. It was a practical expression of Akio’s new worldview: keep overhead low, build fast, and create enough open space to display coordinated room sets the way he’d seen in America.

By then the vision was clear, and it would never really change. Customers didn’t want furniture. They wanted a home that felt intentional—coordinated, harmonious, and easy to imagine living in. And they wanted it at prices that didn’t make good design feel like a luxury.

Everything that came next—imports, private brands, warehouses, factories, software—would be in service of that single insight.

IV. Building the SPA Model: The "Total Coordination" Vision (1975-1990)

In the 1960s and 70s, Japan’s furniture business wasn’t really a “retail industry” in the modern sense. It was a chain of middlemen selling one-off pieces. Prices were high, styles rarely matched, and the in-store experience didn’t help you imagine a finished home. After the U.S. trip, Nitori started attacking that mess one variable at a time.

To see why it required such a rewrite, look at how a table or sofa typically made its way to a Japanese customer. Raw materials were imported by a trading company. A manufacturer bought those materials and produced finished goods. A distributor bought the goods. A retailer bought from the distributor. Only then did the customer finally get a chance to buy it.

Every handoff added cost. And none of those extra margins made the furniture more coordinated, more functional, or more affordable. The system was designed to preserve relationships, not to delight the end buyer.

Akio Nitori’s counterpunch was simple to describe and hard to execute: total coordination. Don’t sell a sofa as a standalone object. Sell a room that feels intentional. He began designing sets that matched in form and tone—sofas that complemented curtains, rugs that fit the palette, shelving that looked like it belonged.

Then he expanded the definition of what “a furniture store” even was. Starting in 1979, Nitori added curtains, rugs, bedding, tableware, and other interior goods, helping pioneer Japan’s home-furnishings category. The strategy wasn’t just aesthetic. It was commercial. People don’t buy a couch every year. But they do buy towels, storage, curtains, and small home upgrades far more often. Expand into those categories, and you give customers a reason to come back—again and again.

All of it tied back to the company’s stated aim: “Present Japan and the whole world with abundant home decoration as splendid as that of Europe and the USA.” Japan hadn’t historically emphasized coordinating interiors by color, design, and material. Nitori made coordination the product, proposing not just what to buy, but how to put it together—at prices mass consumers could actually afford.

But a vision like that can’t survive on merchandising alone. To keep prices low while improving quality and consistency, Nitori had to rebuild the plumbing underneath the business: how it sourced, moved, and controlled product.

A major step came in May 1986, when Nitori began direct imports. Cutting out wholesalers and trading-company layers meant the company could control procurement and logistics, remove markup, and push savings into shelf prices. In plain terms: fewer middlemen, lower costs, more pricing power.

Even earlier, in 1980, Nitori had already made a bet that signaled it was thinking like a much larger enterprise: it built an automated multi-tier warehouse—an industry first in Japanese distribution. For a company that was still proving itself, that was an unusually aggressive move. But it reflected Akio’s belief that scale isn’t just store count. Scale is infrastructure. Systems built for a handful of shops collapse when you try to run dozens, let alone hundreds.

Out of these decisions, a distinct model emerged—what Japan would later call “SPA,” short for Specialty store retailer of Private label Apparel, though in practice it came to mean something broader: design, sourcing, manufacturing, distribution, inventory management, and retail under one roof. Nitori wasn’t just selling furniture. It was assembling a vertically integrated machine that could keep improving, keep cutting costs, and keep tightening the feedback loop between what customers wanted and what factories made.

That’s why, over time, Nitori could operate at a profit margin far above the typical Japanese furniture retailer. And that gap mattered. When you earn meaningfully more per yen of sales than your competitors, you can reinvest more—into warehouses, imports, product development, and price reductions. It becomes a flywheel: better systems enable higher volume, higher volume drives costs down, lower costs win customers, and the whole cycle funds the next upgrade.

The corporate identity evolved in parallel with the strategy. The company became NITORI Furniture Co., Ltd. in June 1978, then NITORI Co., Ltd. in July 1986. Stores were rebranded as Home Furnishing NITORI, a public signal that this was no longer just a place to buy a bedframe—it was a place to furnish a life.

In September 1989, Nitori listed on the Sapporo Stock Exchange, opening access to public capital.

By the end of the 1980s, the model had been proven in Hokkaido: total coordination on the surface, vertical integration underneath. Now came the real test. Could a regional upstart built in Japan’s north take its playbook to Honshu—into the very different retail battlegrounds of Tokyo, Osaka, and beyond?

V. The Great Expansion: Conquering Japan (1990-2010)

If Nitori had been born in Tokyo, its national expansion might have looked like the natural next chapter. But Nitori wasn’t born in Tokyo. It was built on Hokkaido, and it chose to go national at the exact moment Japan stopped feeling like a growth country.

In 1990, Japan’s bubble burst. Deflation set in, property values slid, and consumers tightened their belts. For a lot of retailers, it was a multi-year emergency. For Nitori, it was an opening.

In March 1993, the company crossed the water and opened its first store on Honshu: the Katsuta Store in Hitachinaka, Ibaraki Prefecture. This was the real start of the land grab—funded, in part, by the capital the company had raised after listing on the Sapporo Stock Exchange in 1989. Nitori wasn’t just expanding; it was exporting a system that had been stress-tested in the relative isolation of Hokkaido.

The bet was straightforward: when households feel squeezed, the low-cost operator gains share. Nitori leaned into affordable pricing and value, with a growing mix of imported goods suited to post-bubble Japan. While department stores and higher-end furniture retailers fought to defend margins, Nitori’s pitch got sharper: you can still make your home feel put-together, even when you’re cutting back.

Akio had put a stake in the ground years earlier, back when it sounded like fantasy: 100 stores and 100 billion yen in sales by 2002. Nitori missed by a hair. It hit 100 billion yen in sales in February 2003, and by December that year it had opened its 100th store. In an era that broke plenty of Japanese businesses, being “one year late” was less a miss than a signal that the machine was working.

Underneath the store growth, the supply chain kept getting more serious. In the 1990s, Nitori began operating out of its own factory in Indonesia (starting in 1994), and later in Vietnam (2004), both managed by Nitori Furniture. Over time, this broadened into something more than outsourcing. The company brought struggling OEM partners into the group and turned them into profitable, expanding operations, including factories in Vietnam and Thailand. It was vertical integration with an opportunistic edge: buy weakness, fix it, and make it part of the system.

That system thinking showed up in the details, too. Nitori pointed to manufacturing efficiency as a competitive advantage—for example, claiming it could use about 95% of a piece of lumber, compared with roughly 50–60% for competitors. Whether you’re talking about materials, labor, or shipping, the philosophy was the same: waste is cost, and cost becomes price.

Then came the next stress test. In 2008, the global financial crisis hit—and Nitori responded in the most Nitori way possible: it cut prices. Not once or twice, but a dozen times during the crisis, including four separate cuts in 2009. For most retailers, repeated price cuts in a downturn would look like panic. For Nitori, they were a weapon—possible only because its cost structure could take the hit.

Observers started to describe companies like Nitori as a new face of Japanese retail: relentless about cost control, obsessive about profitability, but still attentive to design and everyday usability. In Japan, where shoppers are famously particular, holding the line on quality while pushing prices down was the real trick—and analysts credited Akio’s single-minded focus for making it work.

By 2010, the transformation was complete. Nitori was no longer a Hokkaido success story. It was Japan’s dominant furniture retailer, with the Tokyo Stock Exchange listing in 2006 adding fuel for even faster expansion.

And maybe the most impressive part wasn’t the store count. It was the fact that Nitori scaled nationally without losing the operational discipline that made it dangerous in the first place. Plenty of regional champions go big and get sloppy. Nitori went big and got sharper—using each downturn as cover, each expansion wave as practice, and each new store as another node in a machine designed to keep getting cheaper, better, and harder to catch.

VI. The Manufacturing-Logistics-IT-Retail Machine

To understand why Nitori keeps winning on price without collapsing on quality, you have to look behind the showroom. The real product isn’t just a sofa or a cabinet. It’s the system that makes those products reliably cheap, consistently good, and easy to get into a customer’s home.

Inside Nitori, that system has a name: the “Manufacturing-Logistics-IT-Retail” model. It’s vertical integration, end to end. Not as a buzzword, but as an operating discipline.

It starts with design. Nitori doesn’t just slap a label on whatever suppliers happen to offer. More than 80% of its items are developed in-house, with teams making the decisions on design, materials, and functionality. And unlike retailers that lean on outside designers, Nitori keeps that work internal, aiming to reflect what everyday customers actually want—and what they’ll notice when they live with the product.

From there, Nitori pushes control downstream into manufacturing. It produces furniture in its own facilities in places like Indonesia and Vietnam, including items such as dressers, kitchen cabinets, and sideboards, and it keeps expanding capacity to stay ahead of future demand.

Even when production happens in factories Nitori doesn’t own, it doesn’t simply hand off responsibility. Nitori staff monitor manufacturing processes on the ground through regional offices, supervising how products are made in addition to inspecting the finished quality. The point is simple: don’t outsource accountability.

That same control shows up in procurement. Nitori negotiates directly with overseas manufacturers and sources from around the world. The company began sourcing overseas in Singapore in 1989, and over time reorganized its footprint into procurement centers in China, Malaysia, and Thailand. Raw materials procured globally are shipped straight to factories that meet Nitori’s standards, and today more than 80% of products are procured overseas.

Then comes the part most retailers treat like a black box: logistics. Nitori doesn’t. It owns and operates its own distribution centers to ship quickly to stores across Japan while reducing storage costs. Its Kanto and Kansai distribution centers are among the largest in the country, and the “systems” here aren’t just buildings. Nitori has developed the full chain, from overseas collection and transport, all the way to small-lot delivery tuned to how Japanese stores actually operate.

One of the best examples is surprisingly unglamorous: packaging. Three years ago, Nitori redesigned packaging and cut its volume by roughly 60%. Manufacturing costs rose a bit—but the trade was worth it. Smaller boxes meant about 2.5 times more product could fit into a container or truck. That lowered logistics costs, reduced CO₂ emissions, and made everything downstream easier: warehousing, store stocking, and even customer carry-out.

It also produced a very Nitori outcome: by shrinking boxes, the company said it was able to avoid building an additional distribution center that would have cost around ¥50 billion. This is what vertical integration buys you. When you control the whole chain, you can optimize across it—and solve expensive problems with changes that look small on the surface.

Quality control is run the same way: as a system. Nitori created its Quality Improvement Division in 2006, brought in quality-control approaches from automotive manufacturing, and built improvement into the workflow. The company doesn’t treat quality as something you “check” at the end; it targets improvements across five stages: development, manufacturing, logistics, retail, and customer service.

Over all of this sits the digital layer. Nitori has been investing heavily in IT and DX to improve efficiency and customer engagement, and in April 2022 it launched Nitori Digital Base CO., LTD. to accelerate those efforts. The company has also said it plans to expand its IT workforce to 1,000 people.

A big piece of that digital push is membership and omnichannel management. By 2023, Nitori reported 42.4 million members, including about 16 million through its app, plus 26.39 million using membership cards. That membership base isn’t just marketing reach—it’s feedback, frequency, and a way to keep improving the machine.

And for customers, all this backstage complexity collapses into something that feels effortless: clean showrooms, low prices, and a delivery network built for convenience. Nitori will even set up the furniture for you.

That last point draws a sharp contrast with IKEA. While typical retailers outsource much of logistics, Nitori stays involved from overseas production to the Japanese end market, using its own delivery network in specified areas to deliver completed furniture free of charge. IKEA, by design, expects customers to assemble many products themselves.

It’s the difference in value proposition. IKEA optimizes for the absolute lowest price. Nitori optimizes for total value—price plus convenience. In a country where homes are smaller and time is scarce, that trade often wins.

Nitori’s model is similar to IKEA’s, but the differences matter. The company says some of its products end up around 30% cheaper than IKEA’s—despite offering more service. If that’s true, it’s not magic. It’s what happens when vertical integration isn’t a slogan, but the core of how you operate.

VII. Key Inflection Point #1: The Shimachu Takeover Battle (2020)

By 2020, Nitori had built its empire the “classic” way: open stores, tighten the machine, repeat. Then it did something that, in Japan, still counts as a little shocking. It tried to buy a major competitor out from under someone else.

The target was Shimachu, a home improvement and home-furnishings retailer with a strong footprint in the Tokyo metropolitan area—exactly where Nitori wanted to deepen its presence, and fast. Shimachu wasn’t sitting idle. It had already agreed to be acquired by DCM Holdings, a major home improvement center operator, via a tender offer to make Shimachu a wholly owned subsidiary.

That’s when Nitori jumped in.

Instead of politely waiting for the deal to close, Nitori announced it was considering its own bid. And it didn’t come in gently. Nitori said it would pay ¥5,500 per share—well above DCM’s ¥4,200—valuing the deal at roughly ¥214 billion (about $2 billion at the time). The message was clear: this wasn’t a partnership conversation. This was a contest.

In corporate Japan, hostile takeovers are still uncommon. Deals are typically negotiated with management first, with an emphasis on long relationships and face-saving outcomes. But the environment was shifting. A government push for stronger corporate governance was putting more pressure on management teams to justify decisions in terms shareholders could defend—especially when a higher-priced offer shows up at the door.

Shimachu initially backed DCM’s offer. Then it reversed course. On November 13, 2020, Shimachu’s board approved a management integration agreement with Nitori, agreed with Nitori’s tender offer, and recommended that shareholders tender their shares. It also withdrew its previous support for DCM’s bid. The day before, Shimachu’s special committee had received a fairness opinion from Plutus stating that ¥5,500 per share was fair to minority shareholders from a financial standpoint.

With that, the “hostile takeover” became something closer to a negotiated surrender—and Nitori didn’t have to force the issue. On December 28, 2020, Nitori completed the acquisition, ultimately taking a 99.99% stake in Shimachu.

Strategically, this wasn’t just about buying stores. The pandemic had pulled demand forward in home categories as people spent more time at home, and it pushed retailers to rethink growth in a Japan facing a shrinking, aging consumer base. Shimachu gave Nitori a bigger platform in home improvement and DIY—an adjacency that expanded the product universe beyond furniture and interior goods.

Shimachu itself had been aiming to become a generalist “home and living” destination, centered on home improvement centers alongside furniture and interiors. Under the Nitori Group, the pitch became: more categories, more reasons to visit, and more ways to “enrich customers’ lifestyles,” as the company framed it.

The Shimachu battle revealed a new Nitori. First, it showed the company was willing to deploy major capital for a single, transformative move. Second, it signaled management’s recognition that organic expansion alone might not move fast enough to hit long-term ambitions. And third, it proved Nitori could fight—and win—in M&A, even in a market where that kind of aggression is still rare.

For investors, it also underlined something simple: decades of steady profitability had built a balance sheet strong enough to outbid a determined rival and make the check clear.

VIII. Key Inflection Point #2: Breaking the Streak and Yen Headwinds (2023-2024)

For 36 consecutive years, Nitori had done something that almost never happens in retail: it kept growing revenue and profit, year after year, through booms, busts, and crises. Then fiscal 2023 arrived, and the streak finally snapped.

For the year ended March, Nitori reported consolidated net profit of 95.1 billion yen, its first decline in 24 years. The culprit wasn’t a single bad quarter or a one-off mistake. It was something more uncomfortable for a company built on “everyday low prices”: the economics of low price were getting harder to defend.

The early warning sign showed up in the traffic numbers. Same-store sales were up 1.2%—but customer traffic fell 5.6%. In other words, Nitori could still keep revenue afloat, but only by pushing prices higher and relying on the customers who did show up to spend more. For a business that wins by being the default choice for ordinary households, fewer visits is the kind of problem that can compound quickly.

The pressure continued. Annual net income fell again in fiscal 2024, declining to $0.597 billion from $0.704 billion in fiscal 2023, after fiscal 2023 had already declined from fiscal 2022.

By the fiscal year ending March 31, 2025, Nitori was still growing the top line—consolidated net sales reached ¥929.0 billion, up 3.7% year-on-year—but profit moved the other direction. Operating profit fell 5.3% to ¥117.67 billion, and profit attributable to owners of the parent fell 8.4% to ¥82.55 billion. Net profit margin slid to 8.3% in FY2025 from 9.7% in FY2024.

If you want the cleanest explanation, it’s the yen.

As the yen weakened sharply against the dollar—moving from around ¥110 in 2021 to about ¥150 by 2024—Nitori’s cost base got hit at the source. This is the dark side of being an import-driven, vertically integrated retailer. When roughly 90% of what you sell is made overseas, currency moves don’t just sting; they reshape your entire P&L.

Management was boxed into a classic retail no-win choice: raise prices and watch traffic drop, or hold prices and watch margins shrink. Either path breaks the kind of profit consistency that had become part of Nitori’s identity.

And yet, the story wasn’t “collapse.” In the six months ended September 30, 2024, Nitori posted stronger results: net sales rose 6.9% year-on-year to ¥445,768 million, and operating profit increased 5.1% to ¥57,974 million. Not a full comeback, but a sign the machine could still adjust.

The balance sheet helped, too. Total assets stood at ¥1,225,826 million, with a capital adequacy ratio of 76.6%. That matters because when the environment turns against you, financial strength buys time—and options—while weaker competitors are forced into panic.

For long-term investors, the end of the streak raised the obvious question: was the 36-year run a once-in-a-generation set of circumstances, or is Nitori’s model still fundamentally sound?

The case for “still sound” is straightforward. The advantages that built the empire—scale, vertical integration, brand trust—didn’t disappear. Currency doesn’t move in one direction forever. And unlike earlier chapters of Nitori’s history, growth is no longer constrained to Japan alone.

Looking ahead to FY2026, Nitori set a target of ¥988.0 billion in net sales, up 6.8% from FY2025. The tone from management stayed ambitious. But the subtext had changed: the era of automatic profit growth was over. From here, it would be earned—through sharper execution, smarter pricing, and a supply chain that had to be resilient not just to competitors, but to macroeconomics.

IX. The Global Ambition: Racing Against IKEA in Asia

Akio Nitori has never been shy about naming the real rival. “Whoever controls Asia, controls the world. Our competitor is IKEA,” he told Nikkei. And then he did what he always does: he turned a big, emotional statement into a very specific strategy.

Nitori’s read on the matchup is blunt. Outside Japan, it says it has more than twice as many stores in Asia as IKEA. But IKEA spans more markets—ten compared to Nitori’s six—and has the kind of global brand recognition money can’t quickly buy. So Nitori isn’t trying to beat IKEA by copying IKEA. “We can’t directly compete with them,” Akio said. Instead, the plan is to fill the gaps IKEA leaves behind, market by market. And he framed the next five years as pivotal.

That urgency shows up in the targets. Nitori has made global expansion the center of its next act: 3,000 stores worldwide by 2032, including 900 in China. Starting in 2025, it planned to open an average of 300 overseas stores per year—an eye-popping pace that works out to roughly one new international store every business day.

China is still the biggest prize, and the hardest one. Nitori opened its 106th outlet in China in Shanghai last month, and it has said all stores there, including those still to come, will be directly operated by the Sapporo-based parent. The format is different, too. Where Japan leaned heavily on large suburban boxes, China is built around smaller and mid-sized stores closer to residential communities.

The assortments shift as well. In China, 60% of inventory is designed in collaboration with local teams—an explicit bet that preferences across Asian markets aren’t interchangeable, and that a more localized approach can outperform IKEA’s more standardized global playbook.

By the fiscal year ending March 2024, Nitori’s push to accelerate global openings was no longer just talk. It expanded store networks in Mainland China, Taiwan, Malaysia, and Singapore, and entered Thailand, Hong Kong, South Korea, and Vietnam. It opened its first store in the Philippines in mid-April 2024 and its first store in Indonesia in late July 2024. That brought Nitori’s reach to customers in ten countries and regions in Asia outside Japan, with India and additional markets under consideration.

Nitori planned to open its first store in India in December 2024, becoming its 11th Asian market.

The reason for the broader map is as much defensive as it is ambitious. By the end of March, Nitori expected to more than double its store count across Southeast Asia and India, in part to avoid being overly exposed to a prolonged consumption slump in China. With China’s property downturn dampening furniture demand, Southeast Asia and India look less like “nice to have” markets and more like necessary second engines.

The operating model stays consistent: full control. “We operate independently in every country,” Nitori has said—China, Vietnam, India, Indonesia, Malaysia, Thailand, the Philippines, Singapore, South Korea—no local partners, no joint ventures. The argument is speed and consistency: full ownership lets Nitori respond quickly to customers and manage the supply chain end to end.

Then there’s the U.S.—the market that tests every furniture retailer’s ego, because it’s also where IKEA is strongest. Nitori entered in 2013 under the Aki-Home banner, using smaller-format stores focused on compact, clean-lined furniture. It even hired veterans from Disney to train staff on customer flow and the in-store experience. Sales grew modestly, and the approach was intentionally patient. Nitori didn’t need instant scale; it needed to learn.

But the experiment was tougher than anticipated. Nitori exited the U.S. on 4/20/2023. The retreat from physical stores underscored a hard truth: competing head-on in IKEA’s home turf, without Nitori’s usual scale advantages, is a different game.

Put together, the global strategy shows a company trying to win where its edge is strongest: deep familiarity with Asian consumers, manufacturing and logistics capabilities throughout the region, and a brand that starts from dominance in Japan. Be flexible on format, localize what matters, own the operations—and, when the advantage isn’t there, be willing to pull back.

X. The Playbook: Business and Leadership Lessons

What makes Nitori remarkable isn’t any single “killer idea.” It’s the way the company has taken a handful of principles—pricing discipline, operational rigor, customer empathy, and relentless learning—and applied them, year after year, until they hardened into a playbook.

The "100x Thinking" Philosophy

Inside Nitori, goal-setting isn’t incremental. It’s designed to be uncomfortable.

The company talks about “100x thinking”: setting targets so far beyond the current reality that you can’t get there by simply working harder or doing more of the same. You need new systems, new infrastructure, and usually, a new way of seeing the business.

Akio Nitori’s early vision—known internally as the “7-1s”—included ambitions like ¥1 trillion in revenue, ¥10 billion per store, and ¥10 million in average employee salaries. He set those goals back when the company had only a few dozen outlets. Over time, most were met or surpassed.

The logic is simple: doubling or tripling a goal is often just perseverance. Trying to grow by 100 times forces reinvention. And it forces the people running the company to grow with it.

Operational Excellence Through Feedback Loops

Nitori’s machine runs on feedback.

Execution happens at the store level, but it doesn’t stay there. Every store submits weekly reports. Managers review what sold, what didn’t, and what customers complained about. Mid-level teams repeatedly revisit stock movement, customer data, and shelf placement. Long-term direction gets broken down into quarterly priorities, then into weekly actions that stores can actually execute.

That constant calibration—tight loops, repeated often—is part of what powered Nitori’s long run of growth before momentum finally slowed in the mid-2020s.

Customer-First Philosophy

“Think and act like a customer—not a retailer.”

It’s one of Nitori’s simplest maxims, and it’s easy to underestimate. In practice, it becomes a filter for everything: how products are designed, how they’re displayed, how quickly they can be delivered, and whether the experience reduces friction for someone furnishing a home.

There’s a Japanese concept that often comes up here: omotenashi. It’s usually translated as hospitality, but it really means anticipating needs before a customer has to ask. Nitori has operationalized that idea, not through luxury service, but through price clarity, efficient delivery, and store layouts that help customers coordinate an entire room without feeling overwhelmed.

Succession Planning

Founder-led companies often talk about succession. Nitori actually did it.

In 2016, Nitori Holdings said that Vice President Toshiyuki Shirai would replace Akio Nitori, then 71, as president. Shirai became President and Director in 2016. He joined the company in 1979, meaning he spent decades inside the culture before taking the top job.

The structure that emerged is deliberate: Akio Nitori remained as Representative Director, Chairperson, and CEO, while Shirai served as Representative Director, President, and COO, running day-to-day operations.

Governance was built to match the scale of the company. The board has nine directors, including five independent outside directors, and an Audit & Supervisory Committee with four members, three of whom are independent. It’s a way to preserve founder continuity without letting the company become dependent on one individual forever.

Learning From Others

Nitori’s defining breakthrough came from looking outward—and it never stopped.

Every year, Nitori flies about 800 employees to the U.S. to visit stores. Traveling on chartered buses, staff study layouts, sales techniques, and the details that matter in home retail: product design, materials, colors, and prices. As Akio Nitori puts it, “America will always be our teacher.”

It’s a rare kind of institutional humility. The risk of success is complacency. Nitori’s answer has been to make curiosity a process—something the organization does on purpose, at scale, as part of the job.

XI. Strategic Analysis: Competitive Position and Future Trajectory

Frameworks like Porter’s Five Forces and Hamilton Helmer’s 7 Powers are useful here not because they “grade” Nitori, but because they force the question Nitori now has to answer: which advantages are structural, and which ones get weaker as the world changes around them?

Porter's Five Forces Analysis

Threat of New Entrants: LOW-MEDIUM

Nitori’s edge comes from a familiar trio—brand recognition, a wide assortment, and sharp pricing—but the real barrier is what sits underneath: its vertically integrated model and the infrastructure required to run it. Building factories, distribution centers, and a national store network takes enormous capital and operational know-how.

That said, the definition of “new entrant” has expanded. A furniture brand that can win online, market through social platforms, and outsource fulfillment can reach customers without owning a single big-box store. Players like Amazon and Alibaba don’t need to replicate Nitori’s footprint to pressure categories and pricing.

Bargaining Power of Suppliers: LOW

Nitori has largely removed supplier leverage by internalizing the supply chain. Roughly 90% of its products are made outside Japan, and many are produced in owned or controlled facilities. Raw materials are sourced globally and shipped directly to factories that meet Nitori’s standards, with more than 80% of products procured overseas.

The effect is simple: fewer dependency points. Traditional supplier power—price hikes, limited capacity, forced assortment compromises—matters less when you control manufacturing, specifications, and procurement.

Bargaining Power of Buyers: MEDIUM-HIGH

Japanese consumers are famously picky, and furniture is a category where reputation sticks. Nitori has won on low price and dependable value, but it still fights a perception gap: some shoppers assume low price equals low quality.

And switching is easy. If a customer decides today that they want a different look, a different brand story, or simply a different shopping experience, they can defect to IKEA, MUJI, or any number of alternatives with little friction. That forces Nitori to keep proving—over and over—that “affordable” doesn’t mean “disposable.”

Threat of Substitutes: MEDIUM

Substitutes are creeping in from multiple angles: second-hand marketplaces, furniture rental subscriptions, and lifestyle shifts toward owning less. Among younger consumers, “experiences over possessions” isn’t just a slogan; it changes what people buy, how long they keep it, and whether they buy at all.

Competitive Rivalry: HIGH

In Japan, the mental shortlist for many shoppers is MUJI, Nitori, and IKEA. All three make cost-effective furniture easy to find, but they win in different ways. MUJI sells restraint—minimalism, natural materials, quiet consistency. IKEA sells global design and the lowest sticker prices, often with customer assembly baked in. Nitori sells a blend: value plus coordination plus convenience.

Those differences don’t reduce rivalry; they intensify it. Each competitor has a clear identity, which makes the fight less about “who sells a couch” and more about which worldview customers want to bring home.

Hamilton Helmer's 7 Powers Framework

Scale Economies: Nitori’s scale shows up everywhere—manufacturing, logistics, and purchasing. With more than 1,000 stores, it can spread fixed costs across huge volume and keep pushing unit costs down.

Network Effects: There aren’t strong classic network effects here, but Nitori does benefit from compounding convenience: brand awareness plus store density makes it the default for a lot of households.

Counter-Positioning: Vertical integration was a strategic bet that many incumbents couldn’t copy without blowing up their existing relationships and economics. When Nitori moved toward owning factories and tightening control, traditional retailers faced a choice: follow and disrupt their supplier model, or stay put and get outpriced.

Switching Costs: Moderate. Furniture isn’t software, but coordination creates its own kind of lock-in. Once you’ve furnished multiple rooms with a Nitori look and sizing standards, switching brands introduces aesthetic mismatch and practical friction.

Branding: Very strong in Japan and still building across Asia. Nitori was ranked the #1 most desirable company to work for among new graduates in 2023 and 2024, and that employer brand helps it recruit and retain talent—an underappreciated advantage in a business that depends on execution.

Cornered Resource: The culture Akio Nitori built, and the founder’s long-term involvement, are difficult to replicate. But founder-linked advantages naturally fade over time, even with a formal leadership transition.

Process Power: This is Nitori’s signature. The “Manufacturing-Logistics-IT-Retail” model isn’t a single trick; it’s decades of accumulated operational knowledge. Competitors can see the outline, but reproducing the day-to-day execution is the hard part.

Key Performance Indicators to Monitor

For anyone tracking Nitori from here, three indicators do a lot of the work:

Same-Store Sales Growth: This tells you whether the existing base is healthy, independent of new store openings. Recent traffic declines paired with modest same-store growth suggest higher pricing is doing more of the lifting—useful in the short term, but risky if it becomes the only lever.

Gross Margin: As exchange rates and transport costs swing, margin shows how well Nitori is managing procurement and pricing—how much it can absorb, and how much it has to pass through. The recent compression in profitability is the signal to watch.

International Store Count and Sales per Store: The 3,000-store ambition only matters if stores are productive. Tracking both expansion and sales per store is how you tell whether overseas growth is creating value—or just accumulating footprints.

Bull Case

The optimistic view is built on a few sturdy pillars: Nitori’s domestic advantages are still real—vertical integration, brand trust, and operational discipline don’t disappear overnight. The expansion thesis is plausible too; across Asia, a growing middle class wants affordable, coordinated home furnishings. Nitori also has balance-sheet strength, giving it flexibility to invest, acquire, and ride out currency volatility. And historically, the company has adapted through shocks rather than breaking under them.

Bear Case

The skeptical view is also straightforward. Currency exposure can keep earnings volatile. Japan’s demographics limit the long-term ceiling of the home market. Overseas expansion demands heavy investment, and returns are uncertain—especially given the reminder from the U.S. exit that not every market rewards the Nitori playbook. Finally, even with succession planning, a company so shaped by its founder faces the long arc question: what happens when founder energy is no longer a renewable resource?

XII. Conclusion: The Enduring Lesson

In 1967, a young man with a track record that looked more like a warning label than a résumé took over a small furniture store in Sapporo. He didn’t have retail training. He didn’t have much capital. And in a country filled with tiny family-run shops, there was no obvious reason this one would become anything more than another name on a sign.

What turned that shaky start into Japan’s dominant home-furnishings empire wasn’t a single clever trick. It was the relentless pursuit of one belief Akio Nitori couldn’t let go of: ordinary Japanese families deserved homes that felt as considered and comfortable as the ones he’d seen in America—without paying luxury prices. Once you accept that as the mission, the rest of the company starts to make sense. Vertical integration. Obsessive cost control. Warehouses, factories, IT, and a plan measured in decades. It all flows from the same conviction.

Over time, that conviction hardened into a flywheel: affordability built trust, trust drove volume, volume justified investment, and investment pushed costs down again. Nitori didn’t just sell “lifestyle.” It made home basics feel like infrastructure—reliable, coordinated, and within reach.

That’s also why the company behaves the way it does. Why it leaned into price cuts during downturns. Why it fought for Shimachu to deepen its presence in Tokyo. Why it runs tight feedback loops from stores back to headquarters, week after week. Nitori isn’t really in the furniture business so much as the repeatability business: the steady cadence of making a good home easier to build.

The long streak of profit growth ended, and that matters. But it doesn’t erase what the company built. Akio Nitori, now 81, has remained Chairperson and CEO—still visiting stores, still studying American retail, still refining the long-range plan he sketched in 1972. The question for the next generation isn’t whether they can copy his instincts. It’s whether they can preserve the philosophy while adapting to a harsher backdrop: currency volatility, Japan’s demographics, and a faster, more competitive Asian retail battlefield.

For investors and business students, Nitori remains a rare case study: durable advantage built less on financial engineering and more on operational excellence, systems thinking, and patience. It’s proof that even in mature, crowded categories, a company can still win—if it builds a machine that gets a little better every year.

The air dome that rose over a snowy Sapporo lot in 1975 was a weird solution to a simple problem: build quickly, display big, keep costs down. The furniture inside that dome is long gone. The mindset that inflated it is still working—quietly compounding, one coordinated room at a time.

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music