Konami: From Jukeboxes to Joysticks to the Great Betrayal

Introduction: The Company That Had Everything—and Walked Away

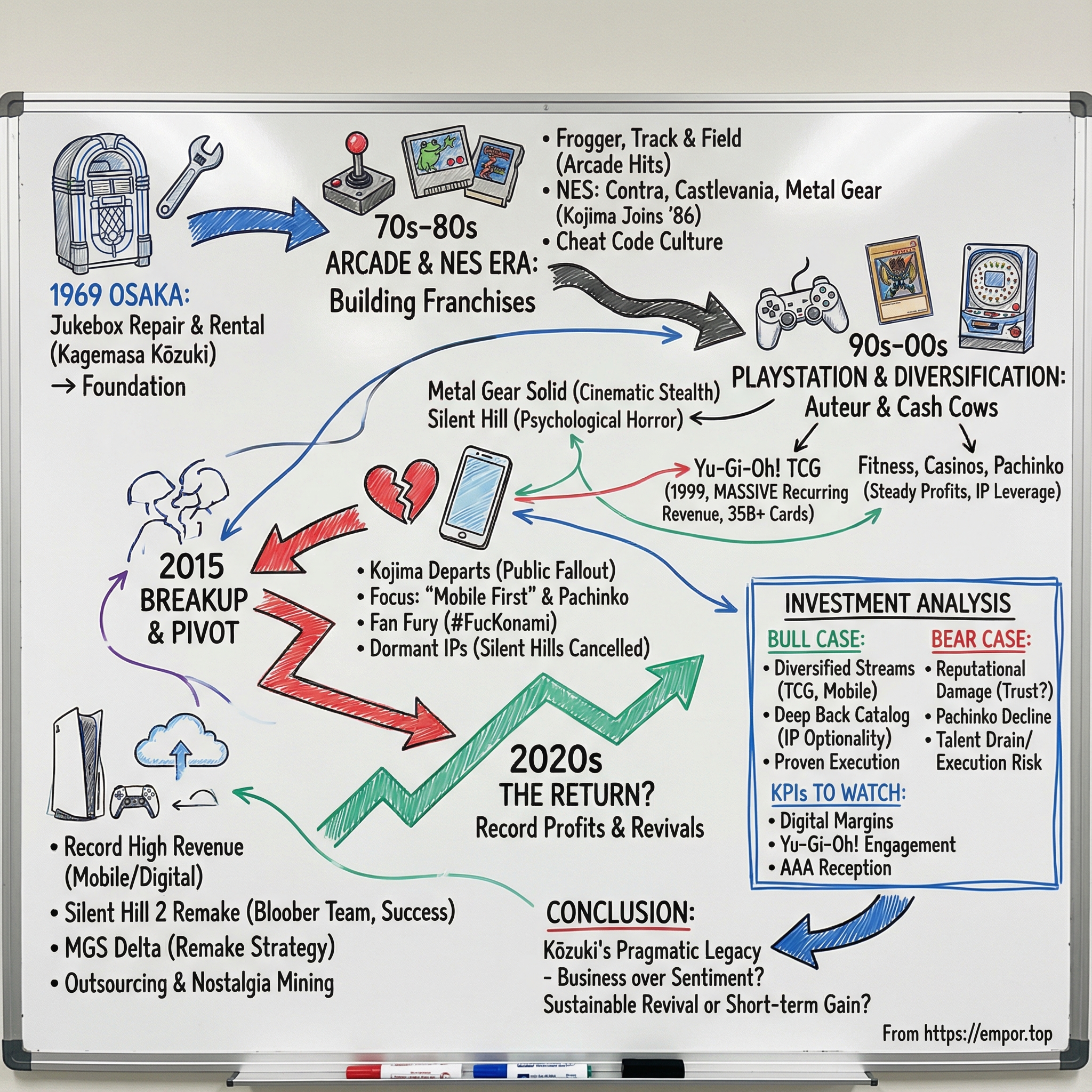

Picture Konami at its peak. The company that, almost by accident, invented stealth action with Metal Gear. The company that turned arcades into dance floors with Dance Dance Revolution. The publisher behind Yu-Gi-Oh!, the best-selling trading card game on the planet, with more than 35 billion cards sold. The same Konami that gave the world a cheat code so famous it escaped gaming entirely—the Konami Code, now a pop-culture shorthand that shows up everywhere from Fortnite to Google Assistant.

Now picture that exact company choosing to step away from the big-budget console games that made it legendary. Choosing to push out its most celebrated creator in a breakup so public and so bitter it became industry lore. And choosing, instead, to lean into mobile games and pachinko.

That’s the story of Konami Group Corporation.

For the fiscal year ended March 31, 2025, Konami recorded total revenue of ¥421.6 billion, with business profit of ¥109.1 billion, up 23.7% year-on-year. In other words: whatever fans may think, the business has rarely looked healthier. Headquartered in Tokyo, Konami today is a Japanese multinational entertainment company whose empire spans digital games, trading cards, anime, pachinko and slot machines, arcade cabinets—the whole spectrum of modern, monetizable entertainment.

But it all started much smaller. In 1969, in Toyonaka, Osaka, Kagemasa Kōzuki founded Konami as a jukebox rental and repair business—work so unglamorous it almost feels like a fake origin story. Kōzuki still serves as chairman, and over the last five-plus decades the company he started has reinvented itself again and again: from servicing machines, to building them, to defining what “video game” could even mean, to becoming a lightning rod for one of gaming’s most controversial pivots.

What makes Konami so fascinating isn’t just the rise, or even the “fall.” It’s the tradeoff. The tension between art and commerce, between auteur-driven creation and spreadsheet certainty. It’s what happens when a company decides that reliable cash flows are more important than the cultural legacy that made the cash possible in the first place.

And the twist is: this story might not be finished. After years of fan fury and franchise dormancy, Konami has been signaling something that once seemed impossible—a return.

Origins: The Jukebox Repairman of Osaka (1969–1978)

Post-war Japan in the 1960s was a country rediscovering leisure. The economic boom was real, American pop culture was pouring in, and people had a little extra money to spend on fun. Bowling alleys multiplied. Pachinko parlors rang with the constant clatter of steel balls. And jukeboxes—bright, loud, unapologetically American—started showing up in cafés, bars, and entertainment venues across the country.

That’s the world Kagemasa Kōzuki stepped into.

On March 21, 1969, Kōzuki founded a jukebox rental and repair business in Toyonaka, Osaka. He was 28 years old, a Kansai University economics graduate, and he picked a business that was almost boringly practical: jukeboxes broke down, needed maintenance, needed new records, and venue owners would happily pay someone reliable to keep the music playing.

Kōzuki himself had been born on November 12, 1940. He attended local schools, graduated from Kansai University in March 1966, and then did what great operators do: he went where the demand was. What made him distinctive wasn’t some romantic creative spark. It was market instinct—an ability to look at the entertainment business and see where the next profit pool was forming.

Even the company’s name hints at that early, scrappy reality. “Konami” comes from the names of three founding members: Kagemasa Kōzuki, Yoshinobu Nakama, and Tatsuo Miyasako. The legend today tends to center on Kōzuki alone, but from the start, this was a small team building something together.

By March 19, 1973, the business leveled up: it was incorporated as Konami Industry Co., Ltd. And with that formality came a bigger ambition. Konami began moving beyond servicing machines and into manufacturing “amusement machines” for arcades. Kōzuki had spent the previous few years learning the entertainment equipment ecosystem—how operators bought, how venues made money, how distribution worked. Now he wanted to be on the higher-margin side of the transaction.

The shift wasn’t a single leap so much as a series of steps. Konami spent the mid-1970s learning electronic entertainment from the inside out. In later recollections, including a 2003 interview, the early picture that emerges is a company doing whatever it could to build competence—manufacturing circuit boards for coin-operated roulette and slot machines, then gradually widening its scope as the industry evolved. These were still the frontier days; everyone did a bit of everything.

By 1978, Konami released its first coin-operated video game. And in 1979, it began exporting to the United States—correctly betting that America’s appetite for arcade games was enormous.

This first chapter matters because it sets Konami’s pattern for the next half-century. Kōzuki wasn’t building a cathedral. He was building a business—one designed to move from low-margin service work to scalable products, from maintaining someone else’s machines to owning the machine itself. That pragmatic DNA powered Konami’s rise, and it also explains the decisions that would later enrage its fans.

The Arcade Empire: Frogger and the Golden Age (1980–1985)

The early 1980s were arcades at full blast. Space Invaders had kicked the doors open. Pac-Man proved games could become a true pop-culture phenomenon. And in the middle of that gold rush, a company that had started by fixing jukeboxes in Osaka began turning into a hit factory.

Konami’s breakout run started fast: Scramble in 1981, then a barrage of games that seemed to land one after another—Frogger and Super Cobra in 1981, Time Pilot in 1982, Roc'n Rope and Track & Field in 1983, and Yie Ar Kung-Fu in 1985. This was the stretch where Konami stopped being “that upstart arcade manufacturer” and started looking like one of the world’s premier arcade developers.

Frogger deserves its own spotlight, because it also shows how Konami operated. The game was simple, instantly readable, and unbelievably sticky. It became one of the highest-grossing arcade games in North America in 1981. But Konami didn’t even publish it in the U.S. Instead, it did what it often did in those early years: it licensed its games to local partners with the distribution muscle already in place. Centuri, Stern Electronics, Sega, Gremlin Industries—Konami’s cabinets could show up under different banners. For Frogger, Sega handled distribution.

That wasn’t indecision. It was discipline. Konami was expanding internationally without pretending it already understood every market, every route, every operator relationship. Licensing meant giving up some margin, sure—but it also meant dramatically lowering risk and moving faster.

Then came the next step: building the American beachhead for real. In November 1982, Konami established its U.S. subsidiary, Konami Inc., in Torrance, California. Two years later, after acquiring arcade distributor Interlogic, Inc., it moved to Buffalo Grove, Illinois—bringing distribution in-house and reducing its reliance on partners.

And the hits themselves weren’t just good—they were tactile. Track & Field became iconic partly because it asked players to physically fight the machine, hammering buttons to run faster. Konami wasn’t only designing games; it was designing how people interacted with games. That instinct would echo for decades, later reappearing in Dance Dance Revolution, beatmania, and eventually the entire Bemani rhythm-game ecosystem.

But even in the middle of this arcade boom, the limits of the business were obvious. Arcade success still meant physical cabinets, floor space, operators, maintenance, and a revenue share. It was great, but it wasn’t infinitely scalable. Meanwhile, the center of gravity was starting to shift to the living room—where you could sell one cartridge once, at mass-market scale, with no operator cut.

Konami could see where this was heading. And it was about to follow the audience home.

Console Dominance: The NES Era and Franchise Building (1985–1993)

By the mid-1980s, Konami could see what every great arcade operator eventually had to admit: the future wasn’t just on the arcade floor. It was in the living room.

They’d already experimented with home releases—a brief run of Atari 2600 titles in the U.S. in 1982, then games for the MSX home computer standard starting in 1983. But the real shift came in 1985, when Konami began publishing for Nintendo’s new phenomenon: the Nintendo Entertainment System.

This was the era that built Konami’s franchise portfolio—the intellectual property that would sustain the company for decades, and later become the emotional center of its biggest controversies. Today, Konami also owns the Bemani rhythm-game brand, and it has absorbed Hudson Soft’s library, including series like Bomberman, Adventure Island, Bonk, Bloody Roar, and Star Soldier. But the crown jewels—the series people still argue about—were born here, on the NES.

Gradius. Castlevania. TwinBee. Ganbare Goemon. Contra. Metal Gear.

These weren’t just successful releases. They were the beginning of a back catalog that would keep paying rent for forty years.

And no franchise from this period is more tightly fused to a single name than Metal Gear is to Hideo Kojima.

Kojima joined Konami in 1986, inspired by Super Mario Bros. and convinced games were going to be his life’s work. He applied partly because Konami stood out in a very practical way: it was the only game company listed on the Japanese stock exchange. But the dream job didn’t start with the dream assignment. Kojima wanted to make games for the Famicom. Instead, he landed in Konami’s MSX division—and he hated the hardware constraints, especially the limited color palette.

His first project as a designer, a plot-heavy platformer called Lost Warld, was cancelled early in production. And that cancellation pushed him toward the idea that changed everything.

The MSX couldn’t handle crowded action scenes; it could only display a small number of enemies at once. So Kojima designed around the limitation. He shifted the core fantasy from fighting to avoiding. Stealth, not combat. Out of necessity, he built a new kind of game—and Metal Gear was the result. It worked. Kojima followed with a sequel, and then the narrative-heavy adventure games Snatcher and Policenauts, establishing a creative voice that Konami would benefit from enormously, right up until it couldn’t—or wouldn’t—anymore.

Commercially, Konami was catching a wave at exactly the right moment. Fueled by the combination of arcade hits and NES success, the company’s earnings jumped from about $10 million in 1987 to around $300 million by 1991. Not gradual growth—escape velocity.

But Nintendo controlled the gates. The NES was a gold mine, and Nintendo enforced strict licensing rules, including a limit of five games per year per third-party publisher. Konami’s response was pure Konami: don’t fight the rule—route around it. They created a wholly-owned subsidiary, Ultra Games, which could publish under its own license and effectively expand Konami’s output.

Ultra Games published the first Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles title for the NES, a massive hit. And in the arcades, Konami’s four-player TMNT beat ’em up became their new top-grossing cabinet—proof that Konami wasn’t just good at original IP. It was also elite at turning licensed properties into money machines.

And then, almost as a footnote, Konami accidentally created one of the most enduring memes in gaming history.

While porting the 1985 arcade game Gradius to the NES, developer Kazuhisa Hashimoto found the game so difficult he couldn’t reliably test it. So he added a cheat sequence that instantly granted a full loadout of power-ups. The plan was to remove it before release. It was overlooked, discovered only as the game was being prepped for mass production, and ultimately left in place because ripping it out risked introducing new bugs.

That little workaround became the Konami Code—arguably the most famous cheat code ever. What started as a developer trying to get through his own playtest turned into a cultural artifact: a secret handshake passed between kids on playgrounds, then later embedded as an easter egg across pop culture.

By the early ’90s, the real achievement of the NES era wasn’t just revenue. It was that Konami had proven something fundamental: it could create franchises with long shelf lives. These games weren’t one-time paydays. They were assets—built to be sequelized, remade, licensed, revived, and, in time, fought over.

The PlayStation Revolution: Metal Gear Solid and the Auteur Era (1994–2004)

The move from cartridges to CDs wasn’t just a hardware upgrade. It was a creative unlock. Suddenly, games could afford voice acting. They could stage cutscenes like movies. They could tell stories with pacing, mood, and spectacle. And if anyone was built for that moment, it was Hideo Kojima.

Konami, to its credit, reorganized to match the new era. After the Sega Saturn and PlayStation launched in 1994, the company shifted into a divisional structure built around semi-autonomous studios. In April 1995, it formed Konami Computer Entertainment (KCE) Tokyo and KCE Osaka. In April 1996, it added KCE Japan—later known as Kojima Productions. Each unit became a little creative engine of its own, with its own identity and, crucially, its own output. KCE Tokyo would go on to create Silent Hill. KCE Japan would define Metal Gear Solid.

This mattered because it formalized something gaming was just starting to embrace: the idea of the auteur. Not “a team made a hit,” but “this person’s voice is the product.” Kojima wasn’t just shipping games anymore. He was becoming Konami’s most visible creative brand.

Then, in 1998, Konami released Metal Gear Solid for the PlayStation. It didn’t just modernize the stealth gameplay Kojima had been forced to invent back on the MSX. It turned stealth into cinema. The long, stylized codec calls. The meticulous military detail. The political paranoia and labyrinthine plotting. The playful fourth-wall tricks. It felt like a game that knew it was a game—and used that as a weapon.

Kojima’s obsession with film and literature, rooted in his childhood, suddenly had the technology to fully express itself. He’d joined Konami in 1986 and directed, designed, and wrote Metal Gear for the MSX2, laying the foundation for both the franchise and the stealth genre. On PlayStation, he scaled that foundation into something that looked and sounded like the future, and he would continue to lead the series all the way through Metal Gear Solid V in 2015.

While Kojima was turning espionage into spectacle, KCE Tokyo took Konami in the opposite direction—and struck gold. Silent Hill wasn’t about action-forward scares. It was about dread. About atmosphere. About guilt, grief, and the sense that the horror wasn’t just in the monsters, but inside the protagonist. In a market where Resident Evil dominated with combat and shock, Silent Hill carved out a colder, stranger lane: psychological terror. It became a franchise, and it cemented Konami as a true heavyweight in horror.

And Konami didn’t stop there. In 1997, the company launched Bemani, its rhythm-game brand for arcades, and it also branched into collectible cards with the Yu-Gi-Oh! Trading Card Game. This wasn’t random experimentation. It was classic Konami behavior—the same pragmatic instinct that had once moved Kōzuki from repairing jukeboxes to manufacturing machines. Entertainment was never “just games.” It was whatever people would pay for, at scale, with the right margins.

By the early 2000s, that created a weird internal contradiction. Konami was winning cultural prestige and global attention through auteur-driven, big-budget console development—especially Kojima’s work. But it was also building businesses where the economics looked cleaner: products that could generate huge revenue without the same time, cost, and creative risk.

That split—between expensive, hit-driven prestige and steadier, lower-risk profit pools—didn’t break Konami immediately. But it set the fault line. And eventually, it would crack wide open.

Yu-Gi-Oh! and the Trading Card Gold Mine (1999–Present)

If there’s one product that explains why modern Konami looks the way it does—and why some of its most controversial decisions start to make cold, financial sense—it’s Yu-Gi-Oh!

Konami launched the Yu-Gi-Oh! Trading Card Game in Japan in 1999, based on Kazuki Takahashi’s manga. The game quickly became a global monster. On July 7, 2009, Guinness World Records named it the top-selling trading card game in the world, at the time citing more than 22 billion cards sold. By March 31, 2011, Konami Digital Entertainment Co., Ltd. Japan reported 25.2 billion cards sold globally since 1999. And by January 2021, the figure was estimated at about 35 billion cards worldwide.

It’s hard to overstate what that means inside the building. Yu-Gi-Oh! has generated more revenue for Konami than any single video game franchise, and the economics are fundamentally different from blockbuster console development. Cards don’t require a three-to-five-year production cycle. They don’t need a new engine. They don’t need Hollywood talent. Once a set is designed and printed, the machine is built to run: booster packs, new releases, tournaments, and a community that keeps showing up year after year.

And Konami didn’t just ride this wave—it fought to control it.

From March 2002 to December 2008, Yu-Gi-Oh! cards in territories outside Asia were distributed by The Upper Deck Company. Then the relationship blew up. In December 2008, Konami sued Upper Deck, alleging it had distributed inauthentic Yu-Gi-Oh! cards made without Konami’s authorization. Upper Deck fired back with its own lawsuit, claiming breach of contract and slander. A few months later, a federal court in Los Angeles issued an injunction that prevented Upper Deck from acting as the authorized distributor. By December 2009, the court found Upper Deck liable for counterfeiting Yu-Gi-Oh! Trading Card Game cards.

Konami’s key point was brutally specific: it proved that unauthorized cards were being produced, allegedly involving employees who took printing plates to a different printer.

The details were even wilder. In depositions, Upper Deck admitted to printing and importing into the U.S. roughly 611,000 unauthentic cards—activity Konami said violated trademark, copyright, and unfair competition laws. The counterfeit cards were printed in China in 2007 and imported without Konami’s authorization. Discovery in the case also revealed that employees, including Upper Deck’s chairman, attended a meeting where they discussed that the unauthorized cards didn’t look authentic enough.

At one point, the chairman shredded counterfeit samples in his own office. It’s the kind of detail that sounds like satire—except it was part of a real lawsuit over one of the most valuable trading card franchises on Earth. And the end result was simple: Konami walked away with full control over its crown jewel.

Then came the next evolution: turning the physical phenomenon into a digital platform. Yu-Gi-Oh! Master Duel launched in January 2022 as a free-to-play digital version of the game, and it became a major success. Released on Steam in January 2022, it has since surpassed 30 million players.

This is the context that makes Konami’s strategy legible. Yu-Gi-Oh! is reliable, high-margin, and repeatable. New sets and digital updates don’t demand the same time, expense, and risk as a AAA console game. So when Konami’s leadership looked across the portfolio and asked what was actually delivering dependable results, Yu-Gi-Oh! didn’t just show up as an answer.

It was the answer.

Diversification Beyond Gaming: Fitness, Casinos, and Pachinko (2000–2015)

By the early 2000s, Konami was doing what it had always done when it sensed a new profit pool forming: it diversified.

As the company transitioned into developing games for the sixth-generation consoles, it branched out into health and fitness by acquiring People Co., Ltd. and Daiei Olympic Sports Club, Inc., which became Konami subsidiaries.

On paper, fitness clubs looked like an odd move for a video game company. Inside Konami, it fit the same pragmatic playbook that had taken Kōzuki from repairing jukeboxes to manufacturing machines. Japan’s aging population and growing health consciousness were creating steady demand, and “steady demand” is catnip if you’re trying to smooth out the highs and lows of hit-driven entertainment. Those fitness operations would later be organized under Konami Sports Co., Ltd., and they remain a meaningful part of the business today.

Konami was also quietly stockpiling something else: intellectual property.

In August 2001, it invested in Hudson Soft, and by 2012 it fully absorbed the company—bringing series like Bomberman, Adventure Island, and Bonk into Konami’s orbit. This wasn’t about making Konami “bigger” in the way fans think of growth. It was about consolidation: owning more recognizable characters and franchises that could be repackaged, licensed, and monetized over time.

And then there was the business that would become, for many fans, the point of no return: pachinko.

Konami wasn’t only a games-and-cards company. It moved into pachinko as well, an enormous pillar of Japan’s entertainment economy—part arcade, part gambling, and culturally as common as slot machines are in the West. Pachinko parlors are everywhere in Japan, and the industry has been staggeringly large. By 1994, the pachinko market in Japan was valued at ¥30 trillion—nearly US$300 billion. Even as the market declined in later years, it remained massive, and Konami saw a clear angle: use its own gaming IP to sell machines.

That’s how you ended up with pachinko and pachislot machines themed around Konami franchises—names like Metal Gear Solid, Silent Hill, and Castlevania showing up not as new games, but as branding on gambling-style hardware.

Operationally, this sat in a dedicated part of the company. Konami Amusement Co., Ltd. handled the production, manufacturing, and sales of pachinko and pachislot machines. And the amusement side kept evolving: in May 2025, Konami announced it would transfer a portion of its amusement machine development business from Konami Amusement to a new company called Konami Arcade Games.

In parallel, Konami built out casino gaming, especially outside Japan. In the United States, it has managed that business from Paradise, Nevada. Konami Gaming Technology Co., Ltd. handles the production, manufacture, and distribution of gaming machines and casino management systems, with a footprint that also extends into Australia.

The casino push even earned Kagemasa Kōzuki personal recognition: he was inducted into the Mississippi Gaming Hall of Fame in May 2022. The citation tied it directly to his long-running leadership of Konami and, since 2000, his involvement in the region through Konami’s U.S.-based casino gaming subsidiary, Konami Gaming, Inc.

Step back, and the business logic is easy to see. Traditional AAA game development is volatile and capital-intensive. A single big release can take years, cost a fortune, and still flop. Fitness clubs, casino systems, pachinko machines, and trading cards are, by comparison, steadier and more predictable. If you’re optimizing for risk-adjusted returns, diversification doesn’t look like betrayal. It looks like responsible management.

But that’s not how it felt to players.

From the outside, it looked like Konami was taking the worlds fans loved, shrinking them down into branding, and feeding them into machines—while the sequels people actually wanted were getting delayed, cancelled, or simply never greenlit at all.

The 2015 Crisis: The Kojima Breakup and Strategic Pivot

March 2015 was the moment Konami’s relationship with its fans didn’t just strain—it snapped.

That month, Konami announced a corporate restructuring: away from a studio-led model where individual teams owned projects, and toward a “headquarters-controlled system,” where decisions flowed from the top. The next day, it unveiled a new executive board. And hanging over both announcements was the loudest silence of all—Hideo Kojima wasn’t mentioned.

During the shuffle, Kojima lost his Executive Content Officer title. Kojima Productions, the internal studio that had effectively been built around him, was suddenly framed as just another unit inside the machine.

Almost immediately, reports surfaced that Kojima would leave Konami after Metal Gear Solid V: The Phantom Pain shipped. Konami later said it was auditioning staff for future Metal Gear titles. And then it did the thing that made the situation feel not just strategic, but personal: it started scrubbing him out of the franchise he’d defined.

Marketing for The Phantom Pain was altered to remove “A Hideo Kojima Game.” The Kojima Productions logo disappeared from official pages. It wasn’t subtle. It was erasure.

At the same time, a new internal logic was taking over. Hideki Hayakawa—known for Dragon Collection, a financially successful Konami mobile game—was rising quickly. The argument, as it was understood outside the company, was blunt: why sink enormous budgets into AAA games when a cheaper mobile title could throw off massive profit? Hayakawa publicly positioned mobile as “the future of gaming,” and dismissed the traditional AAA market as declining. On April 1, 2015, he became president of Konami Digital Entertainment.

The philosophy that followed was clear: mobile and pachinko were the future; expensive, auteur-driven console development was the past.

Silent Hills was cancelled. P.T., its playable teaser, was pulled from the PlayStation Store. And reports described the final stretch of The Phantom Pain’s development as increasingly hostile—production pushed to finish as quickly as possible, with restrictions that made day-to-day work far harder than it needed to be, including cutting off internet access. The Konami-owned version of Kojima Productions was closed on July 10, 2015, ten years after the studio’s creation.

For fans, Silent Hills was the most painful cut. It wasn’t just another sequel—it was a dream team: Kojima and horror director Guillermo del Toro, with Norman Reedus attached. P.T. had become a phenomenon all on its own, the kind of demo that turned anticipation into obsession. Cancelling the project was bad enough. Removing even the teaser made it feel like punishment.

Then came the public humiliation.

At The Game Awards 2015, Metal Gear Solid V won Best Action Game and Best Score/Soundtrack. But Kojima wasn’t there. He was reportedly barred from attending by Konami’s legal department, and the award was accepted by Kiefer Sutherland on his behalf.

“Mr. Kojima had every intention of being with us tonight,” host Geoff Keighley told the audience, “but unfortunately he was informed by a lawyer representing Konami that he would not be allowed to travel to tonight’s award ceremony.”

That’s the kind of line that brands a company. Konami had prevented the director of its own award-winning game from showing up to accept the award.

Kojima officially left Konami later that year. Confirmation of his departure came via The New Yorker, which reported that his final day was October 9. And on December 16, 2015, in a joint announcement with Sony Computer Entertainment, Kojima announced his next move: an independent studio, also named Kojima Productions, founded alongside Yoji Shinkawa and Kenichiro Imaizumi, building a new franchise for PlayStation 4.

For investors, this was more than fandom drama—it was a case study in human capital. Kojima was arguably Konami’s most valuable individual creative asset. Metal Gear Solid had sold tens of millions of copies, and his departure—especially the way it happened—sent a message to developers, partners, and the market: Konami was willing to burn cultural equity to pursue a different operating model.

And Konami wasn’t coy about what that model would be.

The pivot to mobile was explicit. Konami signaled that it would prioritize mobile games over expensive AAA projects. In September, French site Gameblog reported that Konami was shutting down production on all AAA franchises aside from Metal Gear Online and Pro Evolution Soccer.

The company that once defined generations of console gaming was telling the world, in plain terms: we’re moving on.

The Pachinko Backlash and Fan Fury (2015–2020)

The years after Kojima’s departure were defined by two things moving in opposite directions: fan sentiment collapsing, and Konami’s new strategy hardening into place.

For longtime players, the pattern felt almost designed to provoke. A beloved franchise would go quiet as a video game—sometimes with a cancellation that still stung—and then resurface wearing the same branding on a pachinko or pachislot cabinet. Silent Hills was dead, but Silent Hill lived on in pachinko. Kojima was gone, but Metal Gear still showed up—on a Metal Gear Solid 3 pachinko machine. To fans, it didn’t just read as a pivot. It read as a taunt.

It’s also true that the wider public didn’t fully clock what was happening until the mid-2010s, when the downsizing of big console development became harder to ignore. Konami, despite the backlash, stayed the course and continued putting its game series onto gambling-style machines, even as the list of dormant console franchises grew.

The one major attempt to prove Metal Gear could survive without Kojima arrived in 2018: Metal Gear Survive. It wasn’t a stealth-action espionage thriller. It was a zombie-survival spin-off, and for many fans it looked like the clearest signal yet that the old Konami was gone. Kojima, unsurprisingly, wanted no part of it. He called it “totally unrelated” to him and said zombies didn’t belong in a series built on espionage and political fiction.

And yet, financially, the pivot was doing exactly what it was supposed to do.

Konami’s profits rose as it shifted away from expensive AAA development and toward mobile games and gambling-adjacent products. The business stayed healthy even as its reputation among core console fans cratered.

Here’s the nuance that got buried under the anger: Konami was still making games, and a large majority of its revenue was still coming from video games. It was releasing a steady stream of titles—often spread across mobile, PC, and console—but many of the biggest wins either didn’t make much noise in the West, didn’t release there at all, or lived inside “captive” audiences like Yu-Gi-Oh! players.

So the perception became: Konami doesn’t make games anymore; it’s a pachinko company now. The reality was more complicated. Konami was absolutely still in games. It just wasn’t making the games the loudest part of its global fanbase wanted—while franchises like Silent Hill and Castlevania sat on the shelf, gathering myth.

The Redemption Arc? Konami's Return to AAA Gaming (2020–Present)

For years, it felt like Konami had made its choice: fewer big console bets, more predictable businesses. Then, in October 2022, it did something it hadn’t done in a long time. It showed up and said, out loud, that Silent Hill was coming back.

At the Silent Hill Transmission event that month, Konami announced the Silent Hill 2 remake—along with other projects like Silent Hill f, Silent Hill: Townfall, and Silent Hill: Ascension. The message wasn’t subtle: the company was ready to rebuild mainstream interest in one of its most beloved franchises, and it was starting with the title many fans consider untouchable.

Silent Hill 2 is a 2024 survival horror game developed by Bloober Team and published by Konami Digital Entertainment, remaking the 2001 classic originally developed by Team Silent. And it didn’t return quietly. Konami said the remake sold a combined one million physical and digital copies in less than a week after its October 8 launch on PlayStation 5 and PC—making it the fastest-selling entry in the series.

Critically, it landed too. On Metacritic, it notched an “87” score, built from 50 positive reviews and five mixed ones. Team Silent may be long gone, but Silent Hill 2’s reception made the new reality hard to argue with: Konami could hand these worlds to outside studios and still get something that felt legitimate.

Then came the bigger test: Metal Gear.

Metal Gear Solid Delta: Snake Eater launched on August 28, 2025, for PlayStation 5, Windows, and Xbox Series X/S. It’s a remake of Metal Gear Solid 3: Snake Eater from 2004—the fifth main entry in the Metal Gear franchise, and the first chronologically. Konami announced that global physical shipments and digital sales passed one million units within the first 24 hours.

Producer Noriaki Okamura framed the rationale in generational terms. “One of the things that really sparked us to do the remake in general is because we realized that a lot of the newer, younger generation of gamers aren't familiar with the Metal Gear series anymore,” he said. “It was basically our mission, our duty, to kind of continue making sure that the series lives on for future generations.”

And Konami wasn’t treating this as a one-off nostalgia lap.

Since 2022, it has pushed the Silent Hill revival beyond remakes, with new entries including The Short Message, the Silent Hill 2 remake, Silent Hill f, and the upcoming Townfall. In June 2025, Konami also announced a remake of the first Silent Hill, to be developed by Bloober Team following the success of Silent Hill 2.

Even Castlevania—maybe the clearest symbol of “Konami used to make the games I love”—started stirring again. After more than a decade, a new mainline Castlevania game was reportedly set to be announced in 2025. The series didn’t appear at Konami’s June 12, 2025 Press Start showcase, but industry reporter Andy Robinson said a new, big-budget entry is “still coming.”

What’s striking is that this return-to-AAA moment isn’t happening because Konami is desperate. It’s happening while the business is already humming.

For the fiscal year ended March 31, 2025, Konami reported total revenue of ¥421,602 million, up 17.0% year-on-year, and business profit of ¥109,117 million, up 23.7%. And for the three months ended December 31, 2024, Konami said total revenue, business profit, operating profit, profit before income taxes, and profit attributable to owners of the parent all reached record highs on a quarterly basis. Over the first three quarters of that fiscal year, revenue reached ¥310.8 billion (about $2 billion), up 22.8% year-on-year for the nine months leading to December 31, 2024, while profit rose 41.8%.

The engine was still Digital Entertainment. For the fiscal year ended March 31, 2025, business profit in that segment came in at ¥98,935 million, up 24.7%.

And crucially, Konami didn’t abandon the mobile-first logic that replaced the old model in the first place. eFootball—the free-to-play successor to Pro Evolution Soccer—became proof that the “future of gaming” thesis could sit alongside a renewed push into premium console releases. eFootball reached $1 billion gross on mobile devices sometime in 2023, and it has surpassed 800 million downloads.

Investment Analysis: The Bull Case

If you want the bull case for owning Konami, it’s surprisingly clean: this is no longer a company that lives or dies on whether the next big console release hits. It’s a portfolio.

Diversified revenue streams are the first pillar. Yu-Gi-Oh! throws off steady money from both the trading card business and its digital games. eFootball keeps cash coming in through mobile. The fitness clubs and casino gaming operations add ballast outside of games entirely. Put together, that mix reduces the boom-and-bust volatility you usually get in entertainment.

The second pillar is IP depth—and it’s hard to overstate how much of it Konami owns. Metal Gear, Castlevania, Silent Hill, Contra, Gradius, Bomberman. Some of these series have been quiet for years, but they’re not dead; they’re optionality. Konami can wake them up through remakes, sequels, collections, or licensing deals, and the recent Silent Hill and Metal Gear remakes show that nostalgia, handled correctly, can still translate into real commercial outcomes.

Third: proven AAA execution, again. The Silent Hill 2 remake wasn’t just a press release and a trailer cycle—it shipped, reviewed well, and sold. It’s evidence that Konami can still produce premium console games, even if the modern version of Konami often looks more like a curator and publisher, partnering with studios like Bloober Team, than the old internal studio system.

And finally, there’s the home-field advantage. More than 70% of earnings came from Japan, where revenue of ¥219.1 billion (about $1.4 billion) was recorded. That domestic strength gives Konami stability while it selectively pushes outward.

If you like Hamilton Helmer’s 7 Powers framework, Konami has a few that actually matter:

- Cornered Resource: Yu-Gi-Oh! is the world’s best-selling trading card game. You can’t just “build another one” and expect the same gravity.

- Brand: Metal Gear and Castlevania are cultural objects, not just product lines.

- Switching Costs: Yu-Gi-Oh! players don’t just buy cards; they buy into a ruleset, a meta, and a collection. Leaving means walking away from sunk time, money, and identity.

Investment Analysis: The Bear Case

The risks are just as real—and in some cases, they’re self-inflicted.

Reputational damage is the obvious one. The Kojima split and years of franchise dormancy didn’t just annoy core gamers; it poisoned trust. You can still find people in forums, social media, and gaming press referencing “FucKonami,” the hashtag that flared up after the 2015 fallout. That kind of lingering negativity matters, because a comeback requires fans to believe the company won’t abandon them again.

Then there’s execution risk. Remakes are, in a way, the easy mode. You’re working from a blueprint that already proved it can land emotionally and commercially. But the real test is what comes after: genuinely new entries in long-dormant franchises. Can Konami ship a new Metal Gear game without Kojima that the audience accepts as legitimate? Metal Gear Survive’s lukewarm reception is a reminder that “the brand” isn’t always enough.

The pachinko market is another structural headwind. Japan’s pachinko and pachislot industry has been shrinking for years—by 2022 it was valued at ¥14.6 trillion, less than half of the ¥35 trillion peak in 2005. The number of pachinko parlors has fallen just as dramatically, down to 7,665 in 2022 from 18,244 in 1997. For Konami’s Amusement business, that’s not just a cycle; it’s a long decline driven by factors like an aging population and tighter regulation.

Talent is the quiet risk that sits underneath everything else. After a very public, very ugly creator breakup, it’s harder to recruit and retain top-tier creative leaders—especially in an industry where the best people have options. If Konami wants to do more than manage legacy IP, it needs teams that can build new worlds, and its reputation as an employer took a hit.

And while mobile has been lucrative, it’s not a free lunch. Competition is brutal and constant. eFootball has to keep fighting for attention as rivals like EA FC pour resources into their ecosystems. Yu-Gi-Oh! Master Duel, even with its massive built-in fanbase, is still operating in a crowded digital card market full of alternatives.

Using Porter’s Five Forces, the picture looks like this:

- Threat of new entrants: high in mobile, where barriers are low; lower in AAA, where budgets and timelines are huge.

- Buyer power: high—players have endless alternatives and are vocal when disappointed.

- Supplier power: moderate—top development talent can command premium pay and favorable terms.

- Substitutes: everywhere—gaming competes with all other entertainment for time.

- Industry rivalry: intense across every segment Konami plays in.

Key Performance Indicators

If you’re watching Konami as a business, the story shows up in a few simple signals. Three KPIs, in particular, tell you whether this is a stable cash machine that occasionally drops a prestige remake—or a company truly rebuilding a long-term AAA future.

-

Digital Entertainment segment profit margin: This is the heart of modern Konami—video games, trading cards, and everything digital. The question isn’t just “did revenue go up?” It’s whether Konami is turning its IP into real profit. Sustained margins north of 30% would imply the engine is working: strong monetization, disciplined costs, and franchises that still carry pricing power.

-

Yu-Gi-Oh! ecosystem engagement: Yu-Gi-Oh! is Konami’s most reliable pillar, and it has two halves that reinforce each other: physical cards and digital. Card sales, Yu-Gi-Oh! Master Duel player activity, and tournament participation are the health indicators. If engagement starts sliding, it’s not just a product wobble—it’s a warning light for the company’s steadiest revenue stream.

-

AAA release reception: This is the reputation rebuild. Critical scores and early sales for major releases—Silent Hill, Metal Gear, and any future Castlevania—show whether Konami’s return to premium console gaming has legs. Strong launches suggest the company can do more than cash in on nostalgia. Weak ones suggest the “comeback” is really just a short-term harvest of the back catalog.

Conclusion: The Jukebox Repairman's Legacy

Kagemasa Kōzuki is now in his mid-eighties, and his personal fortune is estimated at $3.77 billion. He’s lived long enough to watch a jukebox rental-and-repair hustle in Toyonaka turn into a multinational entertainment conglomerate—one that survived multiple industry resets, endured years of fan fury, and still came out the other side financially stronger than ever.

So the real question for Konami now isn’t whether it can make money. It’s whether money is enough.

Konami has already proven it can generate returns without the goodwill of core console fans. It has shown that Yu-Gi-Oh! and mobile can carry the profit engine even while the internet is on fire. What it hasn’t fully proven—yet—is whether it can recapture the creative electricity that made Metal Gear and Silent Hill matter beyond sales charts. Not as brands. As cultural objects.

The Silent Hill 2 remake and Metal Gear Solid Delta are the clearest signs that the company wants the answer to be yes. The current fiscal year brought Metal Gear back to the spotlight with Metal Gear Solid Delta: Snake Eater. And with Kojima gone, the suspense isn’t just “will it sell?” It’s whether the series still has the same gravity without the person whose fingerprints were on every major choice for decades.

One uncomfortable truth runs through all of this: Konami’s story is, at its core, a business story. It was never a single auteur-led studio in the way people talk about Nintendo under Miyamoto, or Blizzard at its peak. Konami was a corporation that employed extraordinary creative people—and then, when the math changed, treated creativity like any other input. When mobile and pachinko looked like better risk-adjusted bets than expensive AAA development, Konami followed the numbers.

What makes this moment so interesting is that the numbers may be pointing back the other way.

Remakes reduce creative risk. Digital distribution lowers marginal costs. The market has been trained—by companies like Capcom with Resident Evil—that high-quality revivals can be both prestige and profit. Konami isn’t inventing a new strategy. It’s running a proven playbook, using one of the deepest back catalogs in the industry.

For investors, that’s the appeal: a profitable, diversified base business with real optionality in dormant IP. The upside is straightforward—revive the right franchises the right way, and you unlock growth without betting the company. The risks are equally straightforward—execution, and the lingering reputational damage that might cap how many people are willing to come back.

Kōzuki built something enduring. Whether the next generation of Konami leadership can keep it enduring while restoring the creative spark is still an open question. The next few years—Silent Hill f, the rumored return of Castlevania, and whatever comes next for Metal Gear—will decide whether this is a genuine redemption arc or simply nostalgia mining with better production values.

Either way, the business will probably be fine.

Kōzuki designed it that way.

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music