SECOM Co., Ltd.: The Company That Created Japan's Security Industry

I. Introduction & Episode Roadmap

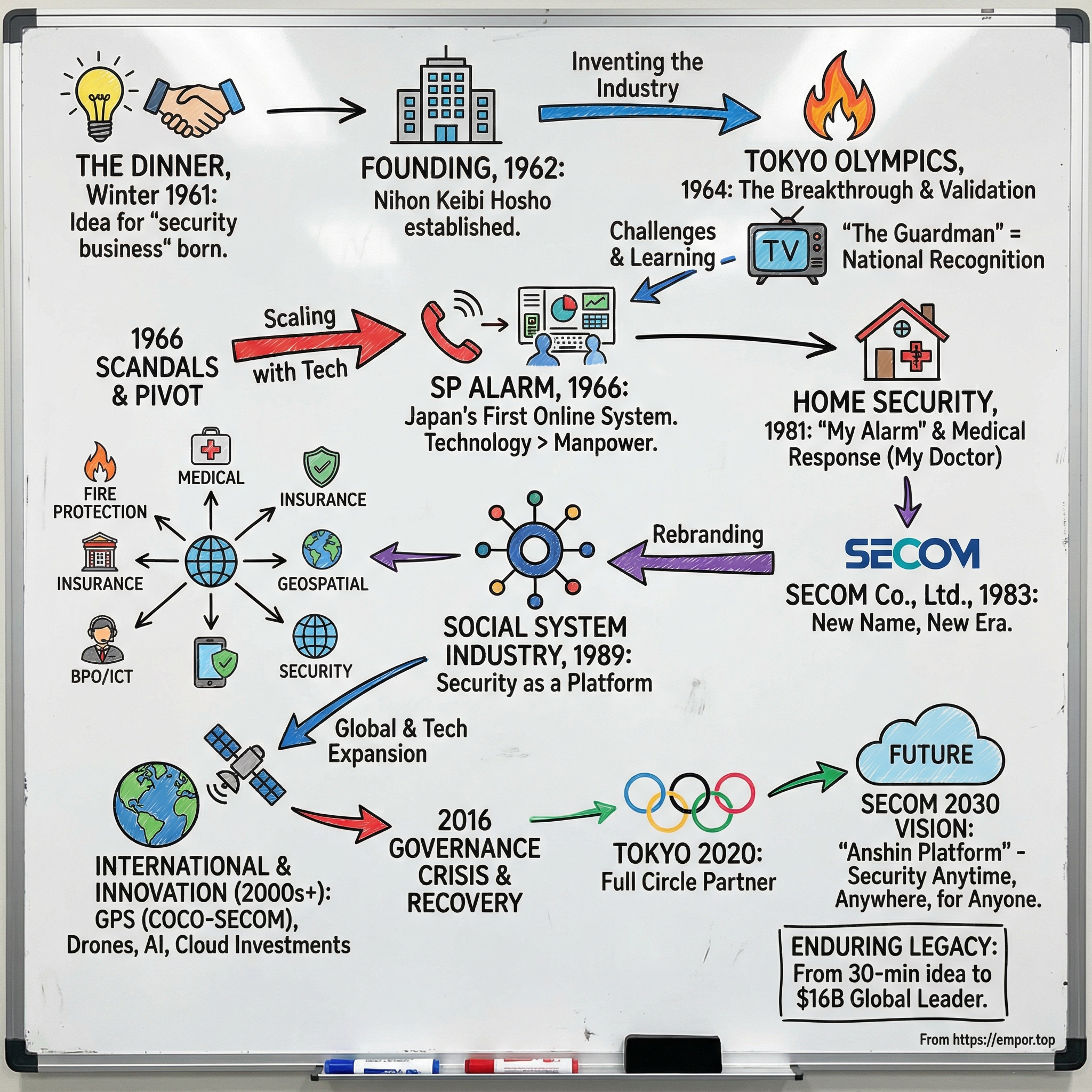

Picture Tokyo in late 2025: a city of millions where office towers, condo lobbies, clinics, and convenience stores share a small, familiar signal—a blue-and-white sticker that says one simple thing: SECOM is watching.

In Japan, SECOM isn’t just a leading security company. It’s the word people reach for when they mean “home security” or “alarm service,” the way some brands become shorthand for the whole category. And it’s not only a Japan story anymore. SECOM provides its online security systems and emergency response services across 12 countries and territories, spanning Asia, Europe, and Oceania.

That dominance is the outcome of a long build. Founded in 1962 as Japan’s first security services provider, SECOM has grown into a global operation serving roughly 3.8 million subscribers. It employs more than 71,000 people across 19 countries and territories, and its market capitalization sits around $16 billion—placing it among the world’s most valuable security companies.

And yet the origin is almost absurdly small.

This giant started with a dinner conversation that took less than thirty minutes.

To understand how SECOM got from that table to becoming embedded in daily life, you have to understand what it chose to become. Today the company operates across six major segments: security services, fire protection, medical services, insurance services, geospatial information services, and BPO/ICT services. That spread isn’t a random conglomerate grab-bag. It’s the deliberate rollout of a concept SECOM calls the “Social System Industry”—the idea that “security” isn’t a single product, but an integrated network that delivers safety, peace of mind, comfort, and convenience.

SECOM formally announced that vision in 1989. From there, security became the hub, and everything else—fire protection, healthcare, insurance, mapping and information services, business process and IT support—grew outward from the same core capabilities: monitoring, dispatch, reliability, and trust.

This is a story about creating a category where none existed, then using technology to scale what would otherwise be a labor-only business. It’s about turning security into a subscription, building a recurring-revenue machine long before that phrase became fashionable. And it’s about seeing Japan’s aging population not just as a social problem, but as a call for new kinds of services—new kinds of “security”—that millions of people would come to depend on.

Now, back to that dinner.

II. The Founding Vision: Creating an Industry from Nothing (1961-1964)

The Dinner That Changed Everything

It was winter 1961. Makoto Iida and Juichi Toda were having dinner with a friend who’d just returned from Europe. Over a chicken hot pot, the friend mentioned something that, in Japan, almost sounded like science fiction: in Europe, there were companies that made a business out of “security.”

Iida and Toda didn’t debate it. They didn’t run spreadsheets. They didn’t workshop names.

They looked at each other and said: that’s it. That’s the business we’ve been looking for.

Less than 30 minutes later, the idea for Japan’s first private security company was born.

To see why that was so audacious, you have to remember what Japan felt like in the early 1960s. The country was in the middle of its economic miracle—wealth rising fast, businesses expanding, cities modernizing. And yet “private security” wasn’t really a thing. It wasn’t a category customers shopped for. Security, in people’s minds, belonged to the state—to police and public institutions, not entrepreneurs.

At the same time, the need was starting to become visible. High-profile incidents like the 300 million yen robbery and a wave of company bombing attacks had jolted corporate Japan into realizing something uncomfortable: maybe security wasn’t “free,” like water. Maybe it had to be designed, paid for, and managed.

Iida and Toda were about to try to sell that idea—before the market even had language for it.

The Founders' Story

Makoto Iida graduated from Gakushuin University in 1956 and went to work in his family business, Okanaga Shoten (now Okanaga), a liquor distributor in Nihonbashi, Tokyo. Juichi Toda was a close friend—someone Iida would drink with, talk with, and repeatedly return to the same question with: if we were going to build something of our own, what should it be?

In post-war Japan, the two would later be remembered as the founding fathers of the private security industry. But at the time, they were simply two ambitious friends searching for the right wedge into a changing society.

That dinner in 1961 handed them the wedge.

In 1962, they founded what would become SECOM—the first Japanese company to provide security services to private and commercial properties.

Establishing Japan's First Security Company

After deciding to start Japan’s first security company, they moved quickly. They opened a small office in Tokyo at Chiyoda Kaikan in Kudan Minami—across from Yasukuni Shrine, near the Indian Embassy. It wasn’t a glamorous launchpad. It was a planning room: gather information, sketch the business, and wrestle with all the friction that comes with trying to invent a market.

The founders later recalled looking out the window in spring 1962 and seeing the cherry blossoms at nearby Chidorigafuchi. It’s a small detail, but it captures the mood: Japan was blooming into something new—and they were trying to build a company that fit the moment.

On July 7, 1962, they incorporated: “Nihon Keibi Hosho,” the company that would later take the name SECOM. The office was on the second floor of the SKF Building at 7-1 Shiba Koen, Minato-ku, Tokyo. They started with 4 million yen in capital, a mix of their own money and bank financing.

Even the name was intentional. “Keibi” meant security. Since they were first, they put “Nihon”—Japan—at the front. And “Hosho” could be written using characters that conveyed either “compensate” or “secure.” In other words: we protect you, and we stand behind that protection.

For a tiny startup, it was a huge statement. They weren’t naming a local guard shop. They were naming a national category.

They also chose a symbol: an owl and a key. The owl for intelligence and vigilance at night; the key for protection. And above it they placed a Latin motto: “VIGILAMUS DUM DORMITIS”—“We defend when the public rests.”

Then came the hard part: selling.

In the early days, Iida did sales himself, visiting company after company. Prospects were curious—often polite, sometimes even excited by the novelty—but almost nobody signed. Two policies made it even harder. First, the founders refused to lean on personal connections. Second, Iida insisted on three months of advance payment.

That demand wasn’t just stubbornness. It was an early blueprint for how SECOM would one day scale: a service that people didn’t purchase once, but subscribed to—protection delivered continuously, paid for upfront, and renewed as a matter of routine.

Still, principles don’t pay the bills. For nearly four months after incorporation, they had no customers.

The first order finally arrived on October 24, 1962: a travel agent hired them for manned patrol services. Iida kept repeating proverbs to himself—“A rolling stone gathers no moss,” and “Sales need patience”—then went right back out, knocking on doors again and again, often without appointments.

It’s worth sitting with the contrast. This company that would one day define Japanese security spent its first months as a ghost—trying to convince the market that the problem was real, and that paying for a solution made sense. That’s what category creation looks like up close: not hockey-stick growth, but persistence in the face of polite disbelief.

III. The Tokyo Olympics Breakthrough & Early Challenges (1964-1966)

The Olympic Village Contract

At the end of 1963, an inquiry landed from the Organizing Committee of the Tokyo Olympic Games: could Nihon Keibi Hosho handle security for the Olympic Village, still under construction?

It was exactly the kind of job a young company dreams about—and exactly the kind that can wreck a young company. Iida’s worry wasn’t whether they could do it. It was what came after. The contract would force them to hire quickly and build capacity fast, but once the flame went out and the world went home, would there be enough work to keep all those new people?

That’s the classic startup trap: a marquee contract that demands scale, but doesn’t promise a future.

On December 10, the official agreement was signed. And when SECOM showed up to do the work, they found the reality on the ground was messier than any document. The village site still had roughly 400 houses—former American Armed Forces housing—waiting to be demolished. It attracted all kinds of unauthorized intrusions: thieves, curious kids, even couples sneaking in. The patrol area was so large that bicycles became part of the job.

On October 10, 1964, the Tokyo Olympics opened. The closing ceremony was set for the 24th. For two weeks, Japan was on display—and this tiny, barely two-year-old company was responsible for protecting one of the most visible parts of the entire event. Nihon Keibi Hosho provided security not only for the athletes’ village in Tokyo’s Yoyogi district, but also for related athletic facilities. Its performance during the Games was widely praised.

And that praise mattered. The Olympic contract didn’t just bring revenue. It validated the entire idea of private security in Japan—and made the company’s name credible overnight.

You can see the impact in the most mundane, telling way: office space. On March 1, 1964, the head office moved for the third time in two years, this time to the 7th floor of the Kurosawa Building in Kanda Jinbocho. The reason was simple: the Olympic contract had forced rapid hiring, and the old office no longer worked.

The previous office was only 23 square meters—small enough that the whole move took a single truck. The new location was a short walk from Ochanomizu Station and only minutes from the old place, but it felt enormous by comparison. Around 100 people were now on staff. SECOM had protected the Olympic Village, proved itself under pressure, and the business finally started to bend upward into real growth.

A company that had struggled to win its first customers was suddenly trusted with Japan’s moment on the world stage—and delivered.

Pop Culture and Brand Recognition

In April, the TV drama The Guardman—based on the company’s exploits—hit the airwaves. It became a major success, and with it came something that’s hard to buy at any price: national recognition.

This was Japan in the 1960s. No social media. No performance marketing. A hit TV show could do what months of door-to-door sales never could. The Guardman didn’t just entertain—it helped the public understand what private security even was, and it pulled SECOM’s name into the mainstream.

Early Scandals and Course Correction

But the mid-1960s also delivered a brutal reminder of what business SECOM was truly in: trust.

In 1966, shortly after introducing its SP Alarm system, the company was hit by a series of scandals when employees were caught stealing. For any company it would be damaging. For a security company, it was existential. If the people selling “peace of mind” can’t be trusted, the product collapses.

The experience was painful, but it forced an early reckoning. SECOM tightened internal controls and put far more weight into training and discipline—building habits that would become part of the company’s identity. In security, reputations don’t erode gradually. They crack all at once.

And the episode reinforced another lesson: if the service depends entirely on humans, human failure becomes the limiting factor. The answer, increasingly, would be technology—systems that could scale, standardize performance, and reduce the surface area for misconduct.

IV. The Technology Pivot: SP Alarm and the Birth of Modern Security (1966-1980)

Inventing Online Security

After the scandals of 1966, SECOM faced a hard truth: if the business was nothing but people, then the business would always be limited by people.

That same year, the company made its defining pivot. In June, it developed SP Alarm—Japan’s first on-line security system.

“Online” in 1966 didn’t mean the internet. It meant a direct connection, via telephone lines, between a customer’s building and a SECOM control center. Sensors installed on-site could detect an intrusion or abnormality and automatically send an alert. From there, SECOM would remotely monitor the premises around the clock and, when needed, dispatch responders from nearby emergency depots.

“SP” stood for Security Patrol, but the bigger idea was that patrol didn’t have to be constant and physical. The building could be “present” at the control center 24 hours a day, 365 days a year—and guards would move only when the system told them something was wrong.

This wasn’t just a new product. It was a new operating model.

Before SP Alarm, security scaled the hard way: more customers meant more guards. With SP Alarm, SECOM could scale through technology. A single response team could effectively cover many locations, because most of the time nothing happened—and when something did, SECOM could react immediately.

To make that promise real, SECOM had to build the nervous system behind it. In July, it established a full-scale central Control Center in Harumi, Tokyo, and opened 18 additional control centers across the country to support the rollout of SP Alarm.

For a young company, that was a huge bet—capital intensive, operationally complex, and totally impossible to fake. But it also created a powerful advantage. The more dense SECOM’s network became in a region, the faster the response times got, and the more efficient each center became. And once you’ve built that national footprint, you’ve built something competitors can’t copy overnight.

Building Corporate Culture

Technology wasn’t the only thing SECOM needed to scale. It also needed a culture sturdy enough to carry a trust business.

In 1967, the company formed the “Shasho Wo Mamoru Kai,” created around the idea that everyone in the organization should share the same mission and principles as SECOM grew. The founders and colleagues would gather and argue—sometimes intensely—about what the organization should be.

Over time, those discussions became the seedbed for what later permeated the company as the “SECOM Philosophies,” passed down from generation to generation.

In a business where one mistake can break the brand, SECOM wasn’t just building systems that detected intruders. It was building an internal system meant to prevent failure.

The Shift to Recurring Revenue

As SECOM expanded SP Alarm across Japan, it kept pushing the model further into software and automation. The company introduced the world’s first computerized security system (CSS). When the system detected an abnormality, it sent a signal to the control center, where relevant information appeared instantly on a monitor—earning high marks for improving both security and operating efficiency.

Just as important, the economics were maturing into something modern investors would instantly recognize: a subscription business. Customers paid ongoing fees for monitoring, dispatch, and service. And once a company wired its building into SECOM’s network and trained its staff around SECOM’s procedures, switching wasn’t just inconvenient—it was disruptive.

By 1974, SECOM was doing more than protecting buildings. It was building specialized, repeatable security “packages” for new use cases. In April, it launched CD Security Pack, Japan’s first security management system for automated cash dispensers.

Then, in June, SECOM was listed on the second section of the Tokyo Stock Exchange.

Twelve years earlier, it had started with a single office and 4 million yen in capital. Now it had a national network of control centers, a technology-driven operating model, and a business structure designed to compound: recurring revenue, high trust, and infrastructure that got stronger the more it spread.

V. From Business to Household: The Home Security Revolution (1981-1989)

Democratizing Security

By the end of the 1970s, SECOM had built a national machine for protecting companies: sensors in buildings, signals flowing to control centers, responders ready to move. The obvious question was: why should that infrastructure stop at the office door?

In 1981, SECOM made the leap and effectively opened Japan’s home security market. It launched My Alarm (now SECOM Home Security), Japan’s first online security system designed specifically for households. The premise was simple and unusually egalitarian for the time: “the security SECOM provides should be available to everyone.”

This wasn’t a minor product extension. It was an expansion of who security was for. Commercial clients were finite. Households were a different universe. If SECOM could make home security feel normal—safe, affordable, easy to use—it could take the operating model it had already proven and scale it into everyday life.

But homes weren’t just smaller offices. Residential customers were more price-sensitive. They didn’t want complicated installations. The system had to be intuitive, reliable, and unobtrusive—something you could live with, not something that made your house feel like a warehouse. The shift forced SECOM to prove it wasn’t only good at engineering and dispatch. It had to be good at consumer product design, service quality, and trust at the family level.

Medical Emergency Integration

Then something unexpected started showing up in the data.

As My Alarm spread, SECOM began receiving more “emergency” calls from elderly customers—many of them not about intruders, but about sudden illness. People were using the security system as a lifeline.

SECOM listened and built for that reality. It developed My Doctor, a pendant-type device that could be squeezed during a medical emergency. The system expanded from guarding homes to watching over the people inside them. Residents could carry a portable emergency button, and sensors in rooms could report long periods of immobility, allowing SECOM to dispatch personnel when necessary.

In hindsight, it was a remarkably early read of Japan’s trajectory. Long before “aging society” became a constant headline, SECOM saw what families were actually anxious about: an elderly parent living alone, a fall, an illness, the terrifying gap between something going wrong and someone noticing.

That insight pushed SECOM into a larger definition of security—one that blended protection with care, and peace of mind with actual response.

The Rebranding

In 1983, the company made its identity match what it was becoming. Nippon Keibi Hosho officially adopted the name SECOM—previously used as a brand—changing the corporate name to “SECOM CO., LTD.”

“SECOM” was coined as a contraction of “security” and “communication,” a concept formulated in 1973: a new kind of security system built on the combination of manpower and technology.

The change did more than modernize the logo. “Nihon Keibi Hosho” anchored the company to Japan and to a specific service. “SECOM” sounded like a platform—short, memorable, easy to say in any language. It signaled that the company wasn’t just a pioneer of Japanese private security anymore. It was preparing to take its model further.

VI. The Social System Industry Vision: Reinventing the Company (1989-2000)

A Bold Corporate Transformation

By the end of the 1980s, SECOM had already proven it could scale security with technology. The question was what to do with that capability once it existed: the nationwide control centers, the communications network, the dispatch operations, the habit of turning anxiety into a service people willingly paid for every month.

In 1989, SECOM answered with a new corporate vision it called the Social System Industry.

On paper, it was a statement about building an integrated framework of services that could deliver safety and peace of mind, while also making daily life more comfortable and convenient—available whenever and wherever needed, for each and every person. Underneath, it was a strategic decision: SECOM would stop thinking of itself as “a security company” and start thinking of itself as a platform.

Security wouldn’t be the end product. It would be the hub.

That framing mattered because it gave SECOM permission to expand—without losing coherence. Instead of diversifying randomly, the company could extend into adjacent domains where trust, monitoring, rapid response, and reliable operations were the core value: physical security, fire protection, healthcare, insurance, and information technology. SECOM also tied the whole thing back to its long-held philosophy of contributing to society through business, positioning the vision as an evolution of what it had always claimed to be—not a reinvention for its own sake.

Founder Iida's Expanding Influence

That same year, Makoto Iida’s ambitions showed up outside SECOM as well. In May, he participated as one of the founders of Daini Denden Kikaku Co., Ltd., which later became KDDI Corporation—now Japan’s second-largest telecommunications carrier. He did it alongside a set of names that signals how serious the effort was: Kyocera founder Kazuo Inamori and Ushio Inc. Chairman Jiro Ushio.

For Iida, this wasn’t a side quest. Telecommunications was the bloodstream of SECOM’s model. If you believe your future is built on networks—signals, monitoring, coordination, response—then helping shape the country’s communications infrastructure isn’t a detour. It’s leverage.

International Expansion Begins

SECOM had also started pushing beyond Japan. Its first move came in 1978, through a business alliance that led to the establishment of Taiwan Secom Co., Ltd., which became the first company to offer online security systems in Taiwan. That was the beginning of full-scale overseas expansion.

Then came Korea. In 1981, SECOM launched Korea Safety System Inc. (founded in July 1980, now S1 Corporation) as a joint venture with the Samsung Group, and began offering online security systems there as well.

The playbook was consistent: don’t try to parachute in as a Japanese exporter. Partner with powerful local players who understood their own markets, and contribute what SECOM was best at—technology, operating discipline, and the online security model tied to emergency response. The Samsung partnership was the cleanest expression of that strategy.

Over time, several of these ventures became leaders in their own right. Taiwan Secom and S1 both grew into publicly listed, dominant security services companies in their respective markets, extending offerings from home security to large-facility safety management systems.

Diversification into Healthcare

The Social System Industry vision wasn’t just about geography. It was about widening the definition of “security” until it matched what people actually feared.

SECOM expanded into full-scale home medical services, including prescription pharmaceutical delivery and home nursing services. It was a logical extension of what My Alarm and My Doctor had already revealed: in an aging society, the most urgent emergencies often aren’t crimes. They’re health events. And “peace of mind” isn’t a slogan—it’s the time between something going wrong and help arriving.

VII. Modern Era & Key Inflection Points (2000-Present)

Technology Innovation: From GPS to Drones

By the early 2000s, the definition of “security” was shifting again. Japan was grappling with deeply human problems—child abductions, and senior citizens with dementia wandering away from home—and these weren’t problems you could solve by hardening a building.

SECOM’s answer was COCO-SECOM, Japan’s first location information-based system. It didn’t just report where something was; it also included an emergency notification service. And when you combine that with SECOM’s existing strength—24/7 monitoring plus on-site dispatch—you get a subtle but important expansion in what the company could protect.

Traditional security is about immobile objects: offices, factories, homes. COCO-SECOM moved the category into motion—people and vehicles. Conceptually, it was a breakthrough: SECOM wasn’t only guarding places anymore. It was guarding lives that moved through the world.

Then SECOM pushed that same idea—sensors plus immediate response—into the air.

In December 2015, the company commercialized the “SECOM Drone,” described as the world’s first private drone for crime prevention. SECOM had been researching small aircraft for security use since the 1990s, but now it was turning that R&D into a service: autonomous surveillance drones that could monitor suspicious cars or individuals on the grounds of factories, stores, and other worksites.

The promise was speed and certainty. When sensors detected an intrusion, the drone could autonomously launch, take the shortest route to the scene, avoid obstacles, track the target, and transmit video back to SECOM’s control center—often faster, and potentially more cost-effective, than sending people for a first look.

The 2016 Governance Crisis

In May 2016, SECOM faced a very different kind of alarm—one inside its own walls.

The board made the rare decision to dismiss both its chairman, Shuji Maeda, and its president, Hiroshi Ito. The stated issue was deteriorating management transparency and the need to uphold strict corporate standards. Whatever the internal details, the headline was unmistakable: one of Japan’s most trusted protection brands was dealing with a trust-and-governance problem at the top.

For SECOM, that’s not just bad optics. Trust is the product. The company’s response—removing top leadership rather than trying to minimize the situation—was a signal that its integrity culture was supposed to apply all the way up. SECOM weathered the upheaval and moved forward with strengthened governance practices.

The Panama Papers Connection

That same year, another trust-adjacent story surfaced in the public record.

The Panama Papers revelations exposed offshore structures created by SECOM’s founders in the early 1990s. According to the documents, in 1992 Iida and Toda retained Mossack Fonseca to register two companies in the British Virgin Islands—Dartmoor Donors Limited and Exmoor Donors Limited—connected by shareholding to other entities registered in Guernsey and Japan. Those shell companies became the de facto holders of about 12 million SECOM shares, valued at roughly 70 billion yen at the time.

SECOM’s position was clear. “In no way was this done to avoid taxes,” a spokesperson said, adding that the information was disclosed to tax authorities and taxes were paid accordingly.

Even with that explanation, the exposure created reputational headwinds—especially coming so close to the governance shake-up. In a business built on credibility, perception matters.

Tokyo 2020 Olympics: Full Circle

And then, in a way, the story looped back to where SECOM first became SECOM.

The company was founded in 1962. Its breakout moment came at the Tokyo 1964 Olympic Games, where it provided security at the Olympic Village. Decades later, SECOM returned as an official partner for the Tokyo 2020 Olympic and Paralympic Games, coordinating venue security planning in collaboration with government entities to ensure safe operations.

Fifty-six years after that first Olympic contract turned a tiny startup into a credible national name, SECOM was back—no longer trying to prove private security belonged on Japan’s biggest stage, but operating as part of the apparatus that made the stage possible.

The 2030 Vision

In May 2017, SECOM published the “SECOM Group 2030 Vision,” a long-term roadmap intended to accelerate the Social System Industry strategy.

At the center of it is the “Anshin Platform” concept—anshin meaning “peace of mind” in Japanese—and the ambition is as sweeping as it sounds: to provide “full-scale security anytime, anywhere, for anyone.” In other words, SECOM wasn’t just planning new products. It was positioning itself as foundational infrastructure for safety and security services—something closer to a platform than a vendor.

Recent Strategic Investments

To get there, SECOM wasn’t relying solely on in-house development. It also went shopping for the future.

In 2023, SECOM made major equity investments in two U.S. cloud-based physical security technology providers: Eagle Eye Networks, in cloud video surveillance, and Brivo, in cloud access control. The total investment was $192 million—$100 million into Eagle Eye and $92 million into Brivo. Both companies are owned by Dean Drako, who framed the deal bluntly: “The SECOM investment underscores that cloud and AI are the future of physical security.”

Alongside that platform shift, SECOM also continued pushing the frontier of human-machine service. In January 2021, it launched what it described as the world’s first security system in which AI-powered virtual characters—“virtual security guards”—provide security services. The idea: combine real-time monitoring with AI that can interact with humans while identifying threats.

Passing of an Era

In early 2023, SECOM marked a more emotional inflection point: the passing of its co-founder, Makoto Iida.

He died on January 7 at age 89. About 2,000 people attended a remembrance ceremony in Tokyo, presenting flowers and praying for the departed. In 1962, Iida and the late Juichi Toda had co-founded Nihon Keibi Hosho, Japan’s first private security services company—the company that became SECOM.

By the time of his death, the industry he helped create had grown into something massive: over 10,000 security companies, around 590,000 security guards, and total sales of approximately 3.45 trillion yen across Japan.

That’s the scale of the thing that began, improbably, with thirty minutes over dinner.

VIII. The Competitive Landscape: SECOM vs. ALSOK

Once SECOM proved private security could work at scale, the obvious next chapter was competition. And in Japan, that competitive picture has been unusually stable.

SECOM sits at the top of the market as the country’s largest security services company. ALSOK—short for Sohgo Security Services—holds the number-two position. CENTRAL SECURITY PATROLS (CSP) is typically cited as third. Beyond those three, the landscape fractures into a long tail of small and mid-sized security firms.

In practical terms, the market behaves like a duopoly: SECOM and ALSOK account for the bulk of the business, and everyone else trails far behind. They’re also in rare company financially—only two security companies in Japan have reached net sales above ¥450 billion, and ALSOK is the other one.

ALSOK’s origin story also connects directly to SECOM’s breakout moment. Jun Murai, ALSOK’s founder, was involved in leading operations at the Tokyo 1964 Olympic Games. That experience became the spark for founding his own company the following year, in 1965, guided by a simple management philosophy: to devote the firm to protecting the safety and security of customers and society as a whole.

So while SECOM used the Olympics as its credibility launchpad—securing the Olympic Village contract—ALSOK’s founder used the same event as his reason to start a rival. One historic moment, two companies, and the beginnings of a decades-long two-horse race.

SECOM, for its part, has often been described as the largest security management company in Asia, built on roughly six decades in the industry. The company’s position in Japan has been especially dominant, with sources sometimes citing a market share north of 60%.

Strategic Differences

Where the two leaders really diverge is in what they chose to become.

SECOM, even though it’s known as a security company, has steadily expanded beyond security services. By 2017, it generated a meaningful share of sales outside its core security business. It pursued growth tied to security-adjacent needs—Japan’s aging society, disaster resilience, and the use of data—backed by acquisitions and expansion into related categories. It bought Nohmi Bosai, a major disaster-prevention facilities manufacturer in Japan. It acquired Pasco, a company known for GIS (Geographic Information System) services. And in 1998, SECOM entered general insurance by acquiring Toyo Kasai, which is now called SECOM General Insurance.

ALSOK took a more focused path. In 2017, it earned the vast majority of its sales from core security services—far more concentrated than SECOM.

Both approaches make intuitive sense. SECOM’s diversification fits its Social System Industry vision: build a platform of services around safety, monitoring, and response, then cross-sell across that ecosystem. ALSOK’s tighter focus can mean deeper specialization and a simpler operating model.

Zooming out, the overall Japanese security services market was estimated at about 3.4 trillion yen in 2016, according to the All Japan Security Service Association—big enough to support giants, but still concentrated enough that the top two effectively set the pace for the entire industry.

On the public markets, SECOM, ALSOK, and CSP are all listed on the Tokyo Stock Exchange. SECOM is also accessible to foreign investors via ADRs on the NYSE, making it easier to own for investors who don’t trade directly in Tokyo.

And the most telling metric in the whole category may be how rarely customers leave. Retention rates are consistently high—above 85% for the major players—because switching is painful. Security isn’t like swapping a software tool. It’s sensors installed across facilities, employee protocols, integrations with monitoring centers, and trust built over years. Once a customer is wired into one of these networks, inertia becomes a feature of the business model.

IX. Business Model Deep Dive: The Social System Industry

By now, the pattern is clear: SECOM didn’t diversify by wandering. It expanded outward from a single capability—security as a networked, always-on service—and kept adding businesses that could plug into the same backbone of monitoring, dispatch, and trust.

That’s what SECOM means by the Social System Industry. Security stays at the center, and the surrounding rings become fire protection, healthcare, insurance, geospatial information, and BPO and ICT services.

Segment Analysis

SECOM’s operating segments map neatly to that vision:

Security Services is still the engine. It includes online security for businesses and homes, static guarding, armored car services, and related protection offerings. The power of the segment is the model SECOM pioneered decades ago: ongoing monitoring and response, paid for in monthly fees, across a subscriber base of more than 2.5 million commercial and residential customers.

Fire Protection Services comes largely through Nohmi Bosai. This business covers fire alarms, extinguishing systems, and ongoing maintenance. SECOM’s acquisition of Nohmi Bosai—described as Japan’s largest disaster-prevention facilities manufacturer—gave the group a major position in fire protection, an obvious adjacency when you’re already selling “safety” as a service.

Medical Services extends SECOM’s residential foothold into care: home nursing, pharmaceutical dispensing, delivery services, and preventive support. This is where the Social System Industry concept stops being abstract. Many customers didn’t arrive asking for “healthcare.” They arrived wanting home security, then used the system as a lifeline—especially elderly subscribers—pulling SECOM deeper into services that keep people safe, not just property.

Insurance Services runs through SECOM General Insurance, providing property and casualty coverage. The logic is straightforward: if you’re selling protection, insurance is the financial layer that sits right behind the physical layer.

Geospatial Information Services comes via PASCO Corporation, which collects and analyzes geographic data using aerial photography and satellite imagery for government and commercial uses. SECOM’s acquisition of Pasco added a major GIS player to the group—less “security guard,” more information infrastructure, but still very much aligned with sensing, mapping, and responding to the real world.

BPO and ICT Services rounds out the platform with data center operations, business process outsourcing, and information security solutions—the digital counterpart to SECOM’s physical network.

Financial Performance

SECOM’s fiscal year 2025 results looked like what you’d expect from a mature market leader: steady, incremental growth rather than dramatic leaps. Full-year revenue was JP¥1.20 trillion, up 3.9% from FY 2024. EPS rose to JP¥260 from JP¥241 the prior year.

Both revenue and EPS were in line with analyst expectations. Forecasts call for revenue growth of about 2.7% per year on average over the next three years, compared with a 4.1% forecast for Japan’s broader Commercial Services industry.

This is the tradeoff of dominance and stability. SECOM isn’t built to produce venture-style hypergrowth. It’s built to keep compounding: a large installed base, recurring subscription-like fees, high customer retention, and adjacent services layered onto an infrastructure that already exists.

Looking ahead, SECOM anticipates 4.3% net sales growth for the fiscal year ending March 31, 2026.

The Aging Society Tailwind

If there’s one macro force that consistently expands SECOM’s addressable market, it’s Japan’s demographics.

Japan has the highest proportion of elderly citizens in the world. Estimates from 2014 put roughly 38% of the population over age 60, and 25.9% over age 65. By 2022, the share over 65 had risen to 29.1%. By 2050, around one-third of the population is expected to be 65 or older.

For SECOM, this isn’t just a statistic—it’s demand in plain language. Elderly people living alone need monitoring and rapid response. Adult children living far from aging parents want reassurance. And overstretched healthcare systems need support for home-based care.

SECOM’s advantage is that it began building for this decades ago. The My Doctor pendant from the 1980s wasn’t a side product; it was an early signal that “security” in Japan would increasingly mean medical response and daily-life safety, not just crime prevention.

Key Performance Indicators for Investors

If you want to track whether the SECOM machine is still getting stronger, a few indicators matter more than almost anything else:

-

Subscriber Count Growth: The simplest health check. SECOM serves approximately 3.8 million subscribers as of March 31, 2025. Growth here tells you whether the franchise is still expanding.

-

Customer Retention Rate: With high switching costs, retention should stay around the high-80s to 90% range. Any sustained decline would be a real warning sign—either competition is biting, or service quality is slipping.

-

Overseas Revenue Percentage: SECOM is working to lift overseas security services to more than 10% of consolidated net sales and operating revenue. Progress toward that level is a clear read on whether the company can export its model beyond Japan at meaningful scale.

X. Bull and Bear Cases: Investment Considerations

The Bull Case

If you’re bullish on SECOM, the argument starts with a simple idea: this isn’t just a company with a good product. It’s a company that built an entire category, then spent decades stacking advantages on top of the original breakthrough.

Dominant Market Position with High Barriers: SECOM holds an outsized share of Japan’s security industry—often cited at over 60%. In a business where trust, response times, and infrastructure density matter, that kind of lead compounds. A challenger can copy a sensor or an app. Replicating a nationwide operating network and a brand that people treat as synonymous with “security” is a much longer project.

Structural Demographic Tailwind: Japan’s aging society keeps expanding demand for monitoring, emergency response, and “peace of mind” services—especially for seniors living alone and the families supporting them from a distance. SECOM is already set up for that demand: the monitoring backbone exists, the dispatch capabilities exist, and the company has spent years building credibility in exactly these use cases.

Recurring Revenue Model: At its core, SECOM is a subscription business. Customers pay ongoing fees for monitoring and response, and retention is high. That makes revenue more predictable than project-based services, because the company isn’t re-selling from scratch each year.

Technology Leadership: SECOM has repeatedly used technology to change the economics of the industry—from Japan’s first online security system to commercializing what it described as the world’s first private drone for crime prevention. The throughline is consistent: use systems and automation to extend coverage, improve speed, and reduce reliance on pure labor.

Diversification Reducing Risk: The Social System Industry strategy has pulled SECOM into adjacent businesses—fire protection, healthcare, insurance, geospatial information, and BPO/ICT—without straying too far from its core competencies. The bull view is that this doesn’t dilute the story; it lowers dependence on any one line of revenue and creates more opportunities to cross-sell into the same customer base.

Porter’s Five Forces Analysis: - Threat of New Entrants: Low. The hard part isn’t starting a security company. It’s building a dense monitoring-and-dispatch infrastructure and earning trust at scale. - Buyer Power: Moderate. Large corporate customers can negotiate, but switching costs are real once systems and procedures are embedded. - Supplier Power: Low. SECOM manufactures much of its own equipment, reducing reliance on a small set of external suppliers. - Threat of Substitutes: Low for core security; higher around the edges as adjacent services face more alternatives. - Competitive Rivalry: Moderate. The market’s long-running SECOM–ALSOK dynamic tends to be more stable than cutthroat.

Hamilton Helmer’s 7 Powers Framework: - Scale Economies: Meaningful. Monitoring and control center infrastructure gets more efficient as the customer base grows. - Network Effects: Limited, but there’s a practical version through brand recognition and ecosystem presence. - Counter-Positioning: Historically strong. SECOM’s tech-enabled model was hard for traditional guard-heavy operators to match without disrupting their own economics. - Switching Costs: High. Hardware installation, system integration, and employee training create friction that keeps customers in place. - Branding: Strong. In Japan, SECOM functions as shorthand for security. - Cornered Resource: Decades of proprietary technology and operating know-how built into the system. - Process Power: A mature, repeatable operating model refined over more than sixty years.

The Bear Case

The bearish case doesn’t argue SECOM is broken. It argues that even great companies can face a tough math problem: mature markets, slow growth, and new kinds of competition.

Japan’s Declining Population: The same demographic story that supports elder-related services also carries a constraint: Japan’s total population is shrinking. Projections based on the current fertility rate suggest a decline from 128 million in 2010 to 87 million by 2060. Over time, fewer people can mean fewer households and fewer businesses—fewer things to secure, even if the need per person rises.

Limited International Success: SECOM has expanded overseas for decades, but international revenue still represents less than 10% of the total. The company has stated it is working to raise overseas security services to more than 10% of consolidated net sales and operating revenue—an implicit acknowledgement that it remains heavily Japan-centric.

Technology Disruption Risks: Cloud-based security platforms, AI-powered monitoring, and IoT devices could shift value away from traditional security operators toward technology-native providers. SECOM’s investments in Eagle Eye Networks and Brivo—$192 million combined—can be read as forward-looking positioning, but also as confirmation that the competitive battlefield is changing.

Governance History: The 2016 dismissal of the chairman and president, plus the reputational shadow of the Panama Papers disclosures, are reminders that governance matters disproportionately in a business where trust is the product.

Modest Growth Trajectory: SECOM looks like a high-quality compounder, not a rocket ship. Revenue is forecast to grow about 2.7% per year on average over the next three years. For investors who need rapid expansion, that pace can feel limiting.

Currency Considerations: For international investors, returns are exposed to yen movements. Even if the business performs well in Japan, currency volatility can materially change results in dollars or euros.

Regulatory Overhang: Security is regulated by nature. Shifts in data privacy rules, labor regulations, or licensing requirements could raise costs, restrict operations, or force changes in how services are delivered.

XI. Conclusion: An Industry Created, A Legacy Secured

In winter 1961, two friends sat down for dinner and heard about a kind of company that existed in Europe but, in Japan, essentially didn’t. Within thirty minutes, they decided to build it. From that small moment came an entire industry that today spans more than 10,000 security companies, roughly 590,000 security guards, and total sales of about ¥3.45 trillion.

That’s the scale. And SECOM’s own arc is just as striking.

It went from 4 million yen in starting capital to a company worth around $16 billion. From a cramped 23-square-meter office to operations across 19 countries and territories. From four months without a single customer to roughly 3.8 million subscribers. SECOM didn’t just win a category—it drew the category’s borders, then kept expanding what “security” could mean.

The company also kept evolving with the times. In March 2024, SECOM hit its RE100 target, becoming the first company in Japan’s security services industry to use 100% renewable electricity via a virtual PPA.

And the innovation hasn’t slowed. SECOM has been integrating AI into its security systems, deploying drones for autonomous monitoring, and building around cloud-based platforms. The challenges are real: Japan’s shrinking population, limited international traction relative to its size, and the risk that technology shifts value toward software-native competitors. But the advantages are real, too: market dominance, high switching costs, a brand that functions as shorthand, and a product roadmap aligned with the demands of an aging society.

For long-term investors, SECOM offers something increasingly rare: a dominant domestic franchise with predictable cash flows—and a strategy that still feels coherent more than six decades after it began. It may not be built for explosive growth. But it is built to endure.

“We defend when the public rests,” the company declared early on.

Sixty-three years later, the public still rests—and SECOM still defends.

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music