Capcom Co., Ltd.: The Story of Gaming's Great Comeback

I. Introduction: From Cotton Candy to Global Gaming Empire

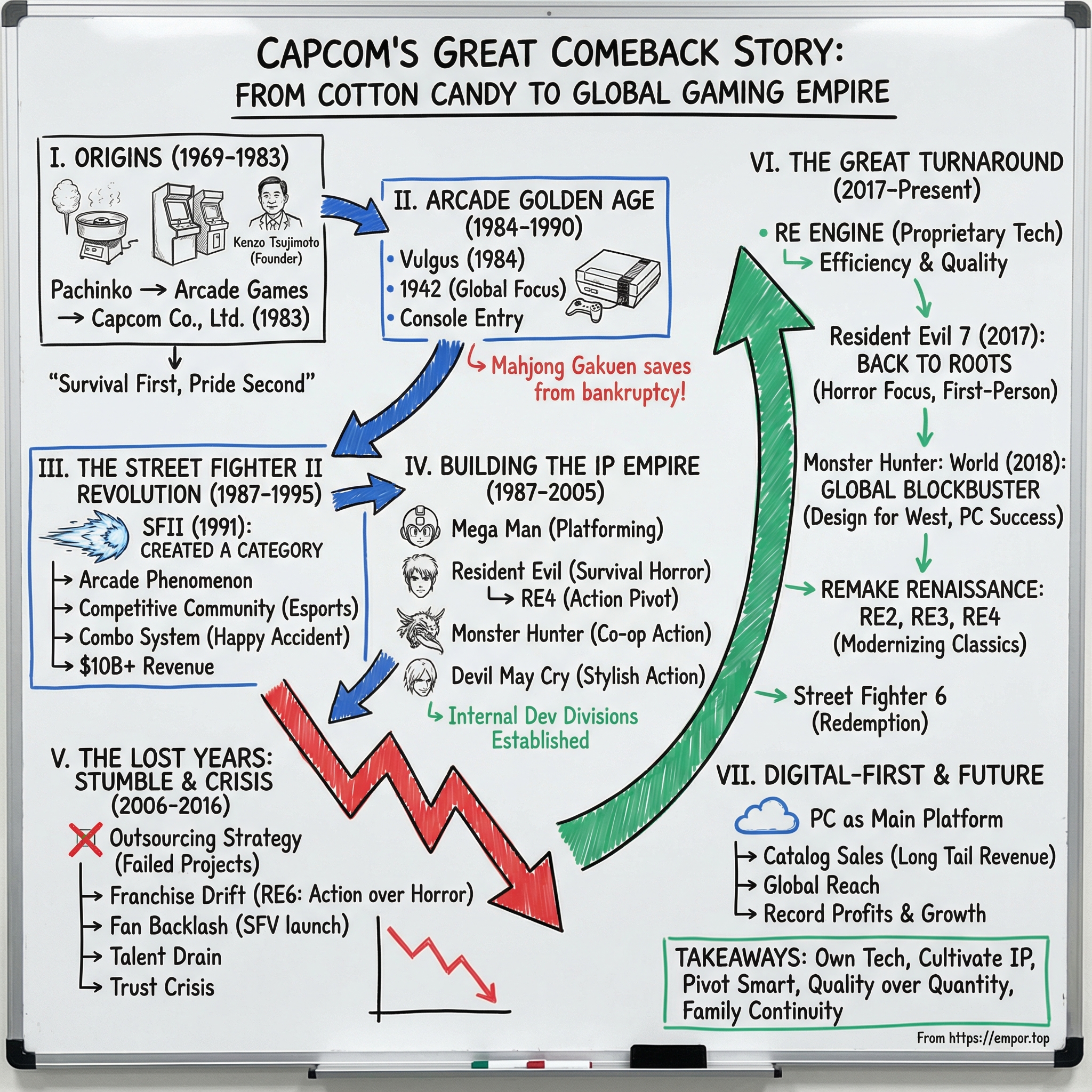

How did a cotton candy machine salesman from Osaka build one of gaming’s most iconic companies—nearly lose it all—and then engineer one of the greatest turnarounds in entertainment history?

Capcom’s story isn’t just about pixels and processors. It’s a multigenerational saga of sharp pivots, creative gambles, and the rare discipline to admit when yesterday’s winning formula has gone stale. Yes, the headlines are staggering: as of 2025, Resident Evil has sold more than 170 million units, making it Capcom’s best-selling franchise and the best-selling horror game series ever. But the real story lives in what those numbers hide—brushes with bankruptcy, years of fan backlash, and a company learning humility the hard way.

Capcom’s roster reads like a greatest-hits album: Resident Evil, Monster Hunter, Street Fighter, Mega Man, Devil May Cry, Dragon’s Dogma, and more. And it didn’t just ship popular games—it helped define entire genres. Survival horror, as the world came to know it, traces straight back to a 1996 trip through a creaky mansion full of the undead. Competitive fighting games—local showdowns that eventually grew into global scenes—owe an enormous debt to a 1991 arcade cabinet that took over arcades and printed money.

But between those peaks is the stretch Capcom would rather not replay. In the early 2010s, the company stumbled. Outsourced projects underperformed. Franchises that had clear identities got smoothed into generic action. The relationship with core fans frayed. Resident Evil 6 became a symbol of the drift: critics gave it credit for production values and controls, but hammered it for tangled campaigns and for moving even further away from the series’ survival horror roots in favor of blockbuster action.

Then came the comeback—one of the most dramatic in modern gaming. By the fiscal year ending March 31, 2025, Capcom reported net sales of 169,604 million yen and operating income of 65,777 million yen, both up double digits year over year. More importantly, it marked 12 consecutive years of operating income growth, culminating in record consolidated sales and profit.

This is the arc we’re going to follow: an entrepreneur who zig-zagged from confectionery to pachinko to arcade machines; the lightning-in-a-bottle success of Street Fighter II; the birth, reinvention, and near-collapse of Resident Evil; the proprietary tech foundation that powered Capcom’s return to form; and a digital-first strategy that turned decades-old games into evergreen assets.

The big takeaways—how to cultivate IP, when to pivot, and why owning your internal technology can change your destiny—go way beyond games. This is corporate adaptation, in its most visceral form.

II. Origins: The Cotton Candy Entrepreneur & The Arcade Gold Rush (1969–1983)

Late-1960s Japan was in motion. The postwar rebuild had hardened into an economic boom, and a new class of entrepreneurs was scanning the country for the next wave of consumer demand.

Kenzo Tsujimoto didn’t come from comfort. Born in Kashihara, Nara, he was the third son of a blacksmith. After his father died, he went to work in 1956 right after junior high, while attending Nara Prefectural Unebi Senior High School part-time. From the beginning, his life was a balancing act: work, school, and survival.

After graduating in 1960, Tsujimoto joined an uncle’s food wholesale business. A few years later, in March 1963, he was moved into his uncle’s confectionery wholesale operation—then struck out on his own. The company was renamed Tsujimoto Shoten. It didn’t go well. He failed as a manager and ended up with debts in the millions of yen.

That early miss mattered. It forged what became his defining reflex: don’t romanticize the plan—follow the opportunity. Pivot quickly. Stay alive. Years later he would sum up his journey simply: “I founded Capcom after spending some time selling cotton candy machines and arcade games. At the age of 42, I started this next business venture and am grateful to have had the opportunity to experience the spectacular growth of the company.”

The leap from sweets to games wasn’t as random as it sounds. Tsujimoto noticed where people were actually gathering—and spending. Pachinko was taking off, and he watched the halls fill with customers. To him, it was a signal: the appetite wasn’t just for candy or trinkets. It was for machines that could hold attention.

In July 1974, he founded IPM—International Playing Machine—later associated with Irem, and became its president. The business was straightforward and opportunistic: build and install entertainment machines for Japanese stores. Then, in 1978, Space Invaders hit and arcades turned into a national obsession. Tsujimoto’s operation moved with the wave, ready to meet demand with lookalike hardware.

He doubled down in 1979 by establishing I.R.M. Corporation, which later changed its name to Sambi in 1981. And in 1983, he created the piece that would become the brand the world remembers: Capcom.

On June 11, 1983, Tsujimoto established Capcom Co., Ltd. to take over Sambi’s internal sales department. Even the name carried a worldview. “Capcom” came from “Capsule Computers,” Capcom’s term for its arcade machines—meant to clearly separate these purpose-built entertainment boxes from the personal computers starting to spread into homes and offices.

From the start, Capcom was also a family story. Tsujimoto’s older son, Haruhiro, would eventually become President and COO in 2007. His younger son, Ryozo, became a producer on Monster Hunter. That continuity—leadership that stayed close to the business across decades—would later matter during both the painful years and the comeback.

Tsujimoto wasn’t a programmer, and he didn’t pretend to be. What he brought was something else: timing, conviction, and the financial seriousness of someone who’d already stared down failure. Capcom’s DNA—pragmatic, opportunistic, and relentlessly adaptable—was set long before the company shipped its first hit game.

III. The Arcade Golden Age: Finding the Formula (1984–1990)

By the early 1980s, Japan’s arcade scene was starting to look like a league table. Namco had Pac-Man. Taito had Space Invaders. Nintendo was already eyeing the living room. For a young company like Capcom, the question wasn’t “Can you make a game?” It was “Can you make a game anyone will care about—again and again?”

Capcom’s first shot was Vulgus, released in May 1984. It was a vertical scrolling shooter: solid, serviceable, and not exactly destiny-changing. But it marked something far more important than reviews. Capcom could now build the whole stack—design the game, manufacture the cabinet, and get it out into the world.

Then they found their footing. With 1942 in 1984, Capcom began aiming beyond Japan, designing arcade games with international players in mind. It paid off quickly. Commando and Ghosts ’n Goblins followed in 1985, and those hits have been credited as the games “that shot [Capcom] to 8-bit silicon stardom” in the mid-1980s.

That global instinct was unusually early—and unusually smart. Many Japanese developers built for domestic tastes first and worried about the West later. Capcom started acting like the world was the market. It’s a small strategic choice that echoes forward, all the way to the moment decades later when Monster Hunter finally needed to break out of its home-country comfort zone.

Capcom also made another move that would reshape its future: it followed its arcade success into the home. Starting with a Nintendo Entertainment System port of 1942 in December 1985, the company stepped into console games—what would eventually become the center of gravity for the entire business. The NES was racing toward global dominance, and Capcom’s arcade craftsmanship mapped cleanly onto the living room.

But even during the wins, the company wasn’t as stable as it looked from the outside. In the late 1980s, Capcom came frighteningly close to going under. And what pulled it back wasn’t a heroic franchise or a landmark blockbuster—it was a strip mahjong game called Mahjong Gakuen. It outsold Ghouls ’n Ghosts, the eighth highest-grossing arcade game of 1989 in Japan, and it’s credited with saving Capcom from a financial crisis.

The story is almost painfully on-brand for Tsujimoto’s Capcom: survival first, pride second. There was internal resistance. “When I was trying to create a Mahjong Academy before the past Street Fighter 2, Tsujimoto shouted NO, saying, ‘Capcom doesn’t make this’ even when the company may be struggling.” But when the alternative was bankruptcy, Tsujimoto relented. Capcom shipped the game it needed to ship, not the game it wanted to be known for.

That’s the survival instinct at the heart of the company. Sometimes you don’t get to choose the clean, artistic option. Sometimes you take the ugly revenue, keep the lights on, and live to fight for your identity later.

In 1989, Sambi merged with Capcom, and the surviving company took the Capcom name. The business was steadier. The pipes were built. And as the 1990s approached, Capcom was finally in position for the breakthrough that would define it around the world.

IV. The Street Fighter II Revolution: Creating a Category (1987–1995)

In the annals of gaming history, few releases have landed like Street Fighter II. It didn’t just sell—it changed what an arcade game could be. It turned play into competition, competition into community, and community into a blueprint for what we’d later call esports.

The seeds were planted in 1987 with the original Street Fighter, designed by Takashi Nishiyama and Hiroshi Matsumoto. Players controlled martial artist Ryu through a globe-trotting tournament across five countries and 10 opponents. It was a modest success, remembered as much for its odd, oversized pressure-sensitive buttons—harder hits if you physically hit the buttons harder—as for the game itself.

Then came the twist: the creators moved on. Nishiyama left Capcom for rival SNK, where he went on to create Fatal Fury—lighting the fuse on a decade of fighting-game rivalry between the two companies.

Capcom still had the name, but the sequel had to be reinvented by a new group. Street Fighter II was designed by Yoshiki Okamoto and Akira Yasuda, who had previously worked on Final Fight. Okamoto had joined Capcom from Konami in the late 1980s, arriving with hard-won instincts from another powerhouse studio. The sequel also became the fourteenth game built on Capcom’s CP System arcade board—important not because anyone in an arcade cared about the chipset, but because Capcom was building a repeatable machine for making hits.

When Street Fighter II hit arcades in 1991, it was seismic. Capcom sold tens of thousands of cabinets worldwide, and demand was strong enough that it kept producing units to satisfy repeat orders. In the United Kingdom, Your Commodore reported that spectators in London’s West End arcades were betting on matches. That’s not a cute anecdote—it’s the moment you realize the product isn’t just “a game.” It’s a sport people want to watch.

And it took over. Between early 1991 and early 1993, Street Fighter II captured roughly 60% of the global coin-op market. Arcades that had been limping along suddenly had lines out the door, clustered around one cabinet.

The money followed the crowds. Across all versions, Street Fighter II went on to generate more than $10 billion in gross revenue, much of it from arcades. At its peak, it was reportedly pulling in $1.5 billion a year in 1993—enough to be cited as that year’s highest-grossing entertainment product, even ahead of Jurassic Park. Zoom out further and the scale stays absurd: as of 2017, Street Fighter II ranked among the top three highest-grossing Japan-made arcade blockbusters ever, alongside Space Invaders and Pac-Man.

So why did this one hit like nothing else? Because Capcom didn’t just polish Street Fighter—it cracked the genre open.

Street Fighter II tightened and expanded the core ideas from the first game: special command-based moves, a six-button layout, and a much larger roster of fighters, each with a distinct style. That roster mattered more than it sounds. Players didn’t just play Street Fighter II—they became a character. Ryu. Guile. Chun-Li. And once players started identifying that way, the game naturally turned social: rivalries, mains, local legends, crowds forming behind their favorite fighter.

And then there was the most famous “feature” of all: the combo system. It wasn’t a grand design. Players discovered that certain attacks could chain together in rapid succession—a quirk in the programming that Capcom didn’t plan. But instead of patching it out, the game—and the genre—embraced it. Mastery suddenly had layers. Execution mattered. Practice mattered. The skill ceiling went vertical.

By 1994, Street Fighter II had been played by an estimated 25 million people in the United States alone. It wasn’t just a hit; it was the hit that restarted arcades.

It also spawned an industry almost immediately. Fighting games flooded the market in its wake: Midway’s Mortal Kombat, SNK’s Fatal Fury and The King of Fighters, Sega’s Virtua Fighter, Namco’s Tekken. Everyone wanted a piece of the category Capcom had just defined.

And Street Fighter didn’t stop being valuable. It remains one of Capcom’s flagship franchises, with total sales reaching 56 million units worldwide as of March 2025.

For the business story, this is the first time Capcom demonstrates a superpower it will return to again and again: genre creation. Street Fighter II didn’t merely win inside an existing market—it rewrote the rules of the market itself. And once you’ve done that once, you start to believe you can do it again.

V. Building the IP Empire: Mega Man, Resident Evil, and the Console Era (1987–2005)

With Street Fighter II turning arcades into cash machines, Capcom did the obvious next thing—and, in hindsight, the only thing that could make the success durable. It started building an empire of characters and worlds it actually owned. Not one miracle cabinet, but a portfolio of franchises that could travel from arcades to consoles, from one generation of hardware to the next.

The foundation was already forming in 1987 with Mega Man. On paper, it was a simple pitch: a blue robot runs, jumps, and shoots. In practice, it was a brilliantly repeatable formula—tight platforming, punishing boss fights, and the hook that made it feel different from everything else on the shelf: beat a boss, steal its power, and reshape your strategy. Decades later, Mega Man has sold over 40 million copies across the series. That’s the long tail of a clean idea executed well and kept alive.

But the franchise that would most define Capcom’s creative identity didn’t wear a helmet. It shuffled.

In 1996, Capcom released Resident Evil on the PlayStation. Created by Shinji Mikami and Tokuro Fujiwara, it took cues from Capcom’s own 1989 horror game Sweet Home and from Western horror cinema—especially George Romero’s zombie films. The result wasn’t just scary; it was structural. Limited resources, claustrophobic spaces, constant dread, and the feeling that survival was never guaranteed. Resident Evil didn’t merely sell—it helped define survival horror as a genre.

And once it worked, it didn’t stay contained inside games. Resident Evil’s influence spilled into pop culture: the specific blend of corporate malfeasance and biological nightmare, ordinary people trapped in extraordinary horror, and a grounded, “scientific” twist on zombies that pushed the genre away from the supernatural. The movie adaptations were critically panned, but commercially successful, grossing over $1.2 billion at the box office. Across games, films, television, pachinko, and merchandise, the franchise has generated an estimated $11 billion in gross revenue as of 2025—making it the highest-grossing horror franchise across all media.

Capcom didn’t just have a hit. It had an engine for hits.

Then, in 2005, Capcom made a move that would reverberate across the entire industry. Resident Evil 4 abandoned the series’ fixed camera angles and tank controls and introduced an over-the-shoulder perspective that became the modern standard for action games. It was a creative triumph and a strategic pivot: the franchise, and much of the industry, shifted toward faster, more kinetic combat.

Not every pivot would age gracefully. In 2009, Resident Evil 5 launched on PlayStation 3, Windows, and Xbox 360 and became the best-selling entry in the franchise, even as fan response was mixed. The center of gravity was moving—more action, less survival horror—and some longtime players could feel the series’ identity stretching.

At the same time, Capcom was getting frighteningly good at turning “mistakes” into new pillars. Devil May Cry famously began as a Resident Evil project for PlayStation 2. But as development progressed, the team realized they’d drifted too far from horror. Instead of forcing it back into the Resident Evil mold, Capcom spun it out into its own franchise: a stylish action series that would go on to sell over 10 million copies.

Internally, the company scaled to support all of this. Capcom organized its major series across two internal Consumer Games Development divisions: Division 1, headed by Jun Takeuchi, developing franchises including Resident Evil, Devil May Cry, Dead Rising, Dragon's Dogma, Ghosts 'n Goblins and Ōkami; and Division 2, headed by Ryozo Tsujimoto, developing Monster Hunter, Mega Man, Ace Attorney, Onimusha and more.

By the mid-2000s, Capcom’s lineup looked almost unfair: Street Fighter for fighting games, Resident Evil for horror, Mega Man for platforming, Monster Hunter for cooperative action, and Devil May Cry for stylish combat. It had genre-defining franchises, proven teams, and a catalogue that could fund the next bet.

From the outside, it looked like permanent success.

It wasn’t.

VI. The Lost Years: From Industry Leader to Crisis (2006–2016)

The decade after Resident Evil 4 should have been a victory lap. Instead, it became Capcom’s most uncomfortable era: a stretch where the company kept shipping big titles, but the creative center didn’t hold. Commercial wins started masking franchise drift. Short-term decisions piled up. And the gap between what Capcom made and what fans wanted got wider every year.

Some of the roots went back further. Capcom was long known as the last major publisher still heavily committed to 2D games—and not entirely by choice. Its earlier commitment to the Super Nintendo Entertainment System as a preferred platform had already caused it to lag behind other publishers in building 3D-capable arcade boards. What had once looked like focus began to look like hesitation as the industry sprinted toward new hardware eras.

Then high-definition consoles arrived and raised the cost of everything. HD development demanded bigger teams, bigger budgets, and a different production muscle. Capcom’s answer, in part, was to lean harder on outsourcing—particularly to Western studios—so it could keep output high without rebuilding every capability internally.

Capcom did this deliberately: it commissioned outside studios to maintain a steady flow of releases. But after poor sales from titles like Dark Void and Bionic Commando, management moved to limit outsourcing to sequels and updated versions within existing franchises, while keeping original titles in-house.

The problem was, by the time that lesson landed, the damage had already been done. The outsourced slate produced too many projects that didn’t click. Worse than the sales was the message it sent: that Capcom was handing off parts of its heritage to teams that didn’t have the same feel for why those games mattered in the first place.

And outsourcing was only part of the story. The deeper issue was identity—especially in Resident Evil.

As the series leaned further into spectacle, even Capcom’s own positioning started to sound like a negotiation. One entry was dubbed “dramatic horror,” but critics increasingly described it as something else entirely: an action shooter wearing a familiar name. The guiding assumption inside Capcom became simple: people didn’t care about horror anymore.

In 2012, series producer Masachika Kawata told Gamasutra that he felt the series needed to move in an action-oriented direction, particularly with the North American market in mind. On paper, the logic wasn’t crazy. Call of Duty was doing enormous numbers. If Resident Evil could even borrow a slice of that audience by going bigger, louder, and more action-driven, the upside looked huge. Producer Hiroyuki Kobayashi later admitted the team included zombies because “they’re popular” and the developers “tried to respond to the [fan] requests and put them in this game.”

That mindset produced Resident Evil 6—a game built to be everything at once: horror, action, co-op spectacle, cinematic blockbuster. And in trying to satisfy everyone, it struggled to satisfy almost anyone.

Capcom’s expectations told you how much it was counting on the strategy. In May 2012, the company said it expected the game to sell 7 million copies by the end of the fiscal year, then revised that forecast down to 6 million after the mixed reception. Capcom also announced that it had shipped 4.5 million copies worldwide, a new record for the company.

But the gap between shipping and selling—and between ambition and reality—became harder to ignore. Despite early momentum, Resident Evil 6 didn’t meet Capcom’s original sales expectations. In February 2013, Capcom issued a statement explaining why the game had sold five million copies worldwide so far.

The quote is revealing, not just for what it says, but for what it admits: “We are currently analyzing the causes, which involve our internal development operations and sales operations. We have not yet reached a clear conclusion…However, we believe that the new challenges we tackled at the development stage were unable to sufficiently appeal to users.”

Resident Evil wasn’t alone. Street Fighter hit its own trust crisis. Street Fighter V launched in 2016 with what fans saw as shockingly sparse features—most infamously, no arcade mode. For a franchise that was born in arcades, it felt like an unforced error. Add in the free-to-play-leaning monetization emphasis on purchasable DLC characters and costumes, and the backlash came fast. The series’ reputation took a hit that no balance patch could immediately fix.

Then came the business practices that turned irritation into anger. “On-disc DLC” in games like Street Fighter X Tekken generated intense backlash when players realized content sold as downloadable was already on the disc—they were being charged to unlock content they technically already owned.

By the late 2000s and early 2010s, Capcom was dealing with a grim combination: key creators leaving, games feeling less complete at launch, and public frustration over excessive DLC. Criticism increasingly landed at the top, with Kenzo Tsujimoto becoming a target of user outrage.

The talent losses were real, and they mattered. Major figures who had helped define Capcom’s modern identity moved on, including Shinji Mikami, Keiji Inafune, and Hideki Kamiya. Each departure wasn’t just a name in the credits—it was experience walking out the door, the kind of institutional memory that tells you when a franchise is about to drift off course.

There’s also an uncomfortable counterpoint that surfaced in hindsight: many former Capcom creators struggled to replicate their Capcom-era success after leaving. That perspective can sound self-serving, but it points to something important. Capcom’s best work wasn’t only about individual genius. It was also about the system around that genius—the production discipline, the internal standards, and the infrastructure that turned talent into consistent hits.

By 2016, Capcom was staring at an existential question: could it rebuild its identity—and regain fan trust—without the people who had originally built so much of it?

VII. The Great Turnaround, Part 1: RE Engine & Resident Evil 7 (2017)

The turnaround began with technology—and with a very unglamorous realization inside Capcom: if they kept making games the same way, they were going to keep getting the same results.

So in 2014, as Resident Evil 7 entered development, Capcom started building a new engine alongside it. The RE Engine was conceived for efficiency—modern tools, faster iteration—and it was designed around the kind of game Resident Evil 7 was going to be: tighter, more focused, and built to deliver dread, not spectacle.

Just as important was what Capcom didn’t do. They didn’t license a third-party engine. The team believed “a highly generic engine developed by another company would not be appropriate” for a game like Resident Evil 7. And they didn’t stick with their existing tech, either—MT Framework was left behind because its tools had become too slow for what HD development demanded.

Jun Takeuchi, head of Capcom’s Division 1, put it plainly: “We had to rethink the way we make games. In order to carry out asset-based (graphic and 3D model elements) development, which is globally the mainstream, we began developing our new RE Engine.”

Even the name was doing double duty. Officially, “RE” stood for “Reach for the Moon.” But no one missed the other meaning. This was also Resident Evil’s lifeline—an engine built to give Capcom a clean break from the habits that had dragged the franchise off course.

Then came the creative reset.

Taking inspiration from the 1981 film The Evil Dead, the developers deliberately scaled the game down to one location. They also made the most radical change of all: first-person perspective. The point wasn’t novelty. It was immersion—and, just as crucially, distance. Third-person had become tangled up with the franchise’s action-heavy era, and with the disappointment of Resident Evil 6. First-person signaled that this was not that.

It was still a risk. Resident Evil had always been third-person, and some fans worried the shift would turn it into a generic shooter. But Capcom’s internal thinking had flipped: stop chasing what’s popular, and start rebuilding trust by making the Resident Evil game people actually wanted.

That shift had been telegraphed years earlier. In 2013, producer Masachika Kawata said the franchise would return its focus to horror and suspense over action, arguing that “survival horror as a genre is never going to be on the same level, financially, as shooters and much more popular, mainstream games. At the same time, I think we need to have the confidence to put money behind these projects.”

That was the new philosophy in one sentence: accept the tradeoff, commit anyway, and win back the audience you’d alienated.

When Resident Evil 7: Biohazard arrived in 2017, critics largely treated it as a return to form. The atmosphere, story, and sense of terror landed; the use of virtual reality stood out; the boss battles and final chapter drew some criticism. But the larger verdict was clear: the series had found itself again. As of June 30, 2025, the game has sold 15.4 million units, making it the second best-selling game in the franchise.

And the content matched the intent. The faceless Umbrella Corporation faded into the background, replaced by something closer, nastier, and more personal: a family of mutated killers who toy with the protagonist. Resident Evil 7 starred Ethan Winters—a regular person, not an elite operative—driven forward by fear and by the desperate need to save someone he loved. Capcom didn’t try to outgun the shooter market. It made an unnerving survival horror game again, and the pieces finally clicked.

But Resident Evil 7 wasn’t just a creative U-turn. It was the foundation for everything that followed.

The RE Engine, built for Resident Evil 7: Biohazard (2017), later powered Resident Evil Village (2021) and Resident Evil Requiem (2026), plus the remakes of Resident Evil 2 (2019), Resident Evil 3 (2020), and Resident Evil 4 (2023). It also became the backbone for Capcom’s broader modern lineup on console and PC, including Devil May Cry 5 (2019), Monster Hunter Rise (2021), Street Fighter 6 (2023), Dragon's Dogma 2 and Kunitsu-Gami: Path of the Goddess (both 2024), and Monster Hunter Wilds (2025), among others.

And it didn’t become “the Resident Evil engine.” According to Monster Hunter producer Ryozo Tsujimoto, no single game or franchise drives its direction; instead, teams across Capcom contribute improvements back into the same shared platform.

That’s where the compounding returns kicked in. Every project that pushed the engine forward made the next one easier, faster, and better. RE Engine wasn’t just a tool—it became Capcom’s most valuable internal asset, and a competitive moat that’s brutally hard to copy.

VIII. The Great Turnaround, Part 2: Monster Hunter World Goes Global (2018)

If Resident Evil 7 proved Capcom could win back critics and core fans, Monster Hunter: World proved something even bigger: Capcom could take a franchise that had been culturally massive at home and turn it into a worldwide blockbuster.

Monster Hunter had been a phenomenon in Japan for years. But outside Japan, it often felt like a game you had to apprentice into. The systems were deep, the onboarding could be unforgiving, and the multiplayer setup—one of the series’ core joys—could be confusing enough to bounce curious newcomers. Add in the series’ handheld roots, built around portable play and short sessions, and you had a franchise that looked like it was destined to remain a regional specialty.

World was the moment Capcom decided that didn’t have to be true.

At Tokyo Game Show 2018, Tsujimoto revealed that the game had passed 10 million shipments worldwide—an all-time high for the series—and, for the first time, shipments outside Japan had overtaken those inside Japan. Overseas accounted for 71%. By the financial year ending March 31, 2019, the game had shipped more than 12 million units, and Capcom described it as a “driving force” behind profitability. Monster Hunter: World had become the best-selling title in Capcom’s history.

That didn’t happen by accident. It happened because the team changed the design philosophy. Earlier Monster Hunter entries had been tuned for Japanese play habits: portable sessions, local meetups, and a structure that assumed you’d learn the game through repetition and community knowledge. World was rebuilt for a different kind of player and a different kind of living-room experience—always-online expectations, smoother matchmaking, and a home console focus built for long hunts on big screens.

The result was a leap in status. After becoming a social phenomenon on handhelds and cementing itself as one of Japan’s most beloved series, Monster Hunter crossed into true global-brand territory in 2018. And it didn’t just spike and fade. Capcom noted that World has continued to sell strongly year after year since release, with total sales now exceeding 25 million units worldwide, repeatedly setting new highs for the company.

The early signals were loud. The NPD Group reported that World was the top-selling game in the United States in both January and February 2018. By April 2018, Capcom said the game’s combined physical shipments and digital sales had surpassed eight million copies—already enough to make it Capcom’s highest-selling game at the time and a major contributor to what it called its most profitable fiscal year in its history.

And then there was PC.

By March 2019, Capcom reported that Windows was the second-highest platform globally for World’s sales. That mattered because Monster Hunter had never been a PC-first franchise. World’s performance on Steam wasn’t just “nice to have”—it was proof of a market Capcom hadn’t fully accessed before, especially in European markets like Germany and Russia. It also foreshadowed where Capcom would go next: a future where PC and digital distribution weren’t side quests, but core strategy.

Today, Monster Hunter has sold more than 120 million units worldwide, making it the best-selling action RPG franchise of all time. Alongside Street Fighter and Resident Evil, it sits in Capcom’s top tier of flagship IP.

But the real impact of Monster Hunter: World was what it unlocked inside the company. Success at that scale didn’t just bring in revenue—it brought breathing room. Capcom now had the resources, and the confidence, to reinvest in its wider portfolio. Devil May Cry 5 arrived in 2019 on the RE Engine, a deliberate return to the franchise’s stylish roots after the poorly received Western-developed reboot. The wave of Resident Evil remakes followed.

And for anyone looking at the business through an investor lens, World delivered the clearest signal yet: Capcom’s library had unrealized value. With the right design choices—and the willingness to rebuild for a global audience—franchises that looked “regional” could become worldwide engines.

IX. The Remake Renaissance & Modern Era (2019–Present)

With the RE Engine proven and the core franchises back on track, Capcom moved into the next phase of its comeback: not just making new hits, but mining its own history—carefully, and with real craft. This was the remake renaissance: taking classics that defined genres and rebuilding them so a modern audience could feel what made them special in the first place.

The inflection point was Resident Evil 2. Released in January 2019 for PlayStation 4, Windows, and Xbox One, it wasn’t framed as a museum piece. Capcom treated it like a major new release—because, in practice, that’s what it was.

And crucially, it wasn’t simply a prettier version of 1998. The remake modernized the way the game played while keeping the core ingredient intact: dread. The tight spaces, the constant pressure, the sense that you’re always one mistake away from disaster—those weren’t sacrificed for spectacle. Built on the RE Engine—the same foundation as Resident Evil 7—it felt both contemporary and unmistakably Resident Evil.

The response was immediate. Resident Evil 2 received acclaim for its presentation, gameplay, and faithfulness to the original. It won the Golden Joystick Award for Game of the Year and was nominated for The Game Award for Game of the Year. Commercially, it became a new pillar: by August 2025, it had sold 15.8 million copies, making it the best-selling Resident Evil game.

Capcom didn’t stop there. The momentum continued with Resident Evil 3 in 2020 and Resident Evil 4 in 2023, turning what could’ve been a one-off nostalgia play into a repeatable machine.

Part of why this worked was that it was strategically efficient. The teams weren’t starting from zero—they had proven designs as a baseline. The RE Engine handled the technical heavy lifting. And marketing didn’t have to invent meaning from scratch; it could lean on nostalgia while still offering something genuinely new.

By the end of 2024, that approach had produced blockbuster results. The recent Resident Evil remake series had sold around 34 million copies in just six years since the first remake released. And Resident Evil 2 alone had become the anchor of the entire effort, with roughly 15 million copies sold since launch.

It also created a fascinating, very modern Capcom scoreboard: the biggest recent entries were now clustered at the top. Resident Evil 2 (2019) led with 15.8 million units sold, followed closely by Resident Evil 7: Biohazard at 15.4 million units.

This era wasn’t only about Resident Evil, either. In 2023, Street Fighter 6 completed the rehabilitation of another cornerstone franchise. It responded directly to the Street Fighter V backlash with a fuller package: robust single-player content, multiple modes, and a new visual style that clearly set it apart. As of March 2025, Street Fighter’s total sales had surpassed 56 million units worldwide.

Then came the next Monster Hunter leap. Monster Hunter Wilds arrived in February 2025 as the successor to World, and Capcom said it sold over eight million units in its first three days—making it the fastest-selling game in Capcom’s history. Capcom credited the launch to marketing aimed at a broad global audience, plus online beta tests ahead of release. By the end of March 2025, Wilds had reached ten million sales.

Wilds also underlined the new reality of Capcom’s business: this was now a global, cross-platform machine. In Japan, it set the record for the largest physical sales launch of any PlayStation 5 title, selling 601,179 copies in its first week. And on PC, it hit a staggering peak: over 1.3 million concurrent users on Steam on the day of release, the highest concurrent Steam player count for any Capcom game.

And Capcom wasn’t done. Looking ahead, the ninth mainline entry, Resident Evil Requiem, is scheduled for release on February 27, 2026.

X. The Digital-First Strategy & Platform Evolution

Capcom’s financial transformation in recent years wasn’t driven only by better games. It was also driven by a quieter change that, over time, rewired the entire business: a shift in how those games were sold.

Capcom’s Fiscal Year 2024 report made the direction unmistakable. Digital now dominates the mix, and PC has become the company’s biggest digital storefront. In FY24, Capcom sold about 28.2 million games digitally on PC—roughly 60% of its digital volume—versus about 18.5 million on consoles, around 40%. Total unit sales for the year were just under 52 million, up from roughly 46 million the year before.

That mix matters because it changes the economics. Physical distribution means manufacturing discs, shipping boxes, negotiating retail shelf space, dealing with markups, and eating returns. Digital cuts most of that out. When you combine digital distribution with a growing global PC audience, your margin structure starts looking a lot better.

Haruhiro Tsujimoto, Capcom’s president and COO, described the flywheel they’re building: they sold 51.87 million units in FY24 on the back of a big increase in PC sales, planned to reach 54 million units in FY25, and are targeting a long-term goal of 100 million units annually. The reason they’re even willing to say that out loud comes down to two forces working together: the steady release of major hits, and the compounding effect of catalog sales—older titles that keep selling year after year once digital makes them easy to find and easy to buy globally.

This “catalog” strategy is where digital really becomes a superpower. A physical game naturally disappears when retailers stop stocking it. A digital game can stay available indefinitely, and it can resurface anytime there’s a platform sale, a discount promotion, or a new release that sends players back to the older entries. A game from a decade ago can become “new” again to someone who just discovered the franchise last week.

Capcom has leaned into that reality with flexible pricing across new releases and older titles, and by using new announcements to drive renewed interest in back-catalog games. The reach is global: the company now sells into well over 220 countries and regions, something that would have been economically impossible in the disc-and-box era. In the fiscal year ending March 31, 2025, Capcom said 13 titles cleared one million sales for the year—proof that games like Devil May Cry 5 and Resident Evil 7: Biohazard aren’t just legacy products, they’re ongoing contributors.

PC is central to all of it. In the fiscal year ended March 2025, PC accounted for more than half of total unit sales, and Capcom expects that share to keep rising from FY26 onward. The logic is simple: PC ownership continues to grow worldwide, including in Japan, and catalog-heavy sales tend to skew PC.

This also opens doors that consoles can’t always reach. In regions where dedicated console hardware is expensive or hard to find, PC gaming thrives. Digital distribution lets Capcom sell profitably in markets that physical logistics would never justify.

You can see the impact in the balance sheet too. By the end of FY24, Capcom’s cash reserves had risen to ¥125 billion, up from ¥53 billion at the end of FY19—an indication of how much cash the business is now generating as the digital and catalog flywheel spins faster.

XI. Playbook: Business & Investing Lessons

Capcom’s comeback is entertaining as a gaming story, but it’s even more interesting as a business case study. Under the franchises and fanfare, there’s a very repeatable playbook here—one that applies well beyond this industry.

1. Own Your Technology Stack

The RE Engine changed Capcom’s trajectory because it changed how Capcom builds. By developing proprietary technology optimized for its own games, Capcom gained advantages that are hard for studios using licensed, one-size-fits-most engines to match.

A big part of the edge is simple organizational physics: the RE Engine team is in-house. If a game needs the engine to do something specific, the developers can go straight to the people who maintain it and get it built. Instead of forcing the game to fit the tool, the tool can bend around the game.

2. IP as Annuities

Capcom’s best franchises behave less like one-time products and more like long-lived assets. Resident Evil launched in 1996 and is still the company’s best-selling series. With a digital-first, catalog-heavy strategy, that library doesn’t “age out” the way boxed games used to. It keeps generating revenue, year after year, with the kind of long-tail economics capital allocators love: predictable, compounding returns from proven brands.

3. Know When to Return to Your Roots

The decision behind Resident Evil 7 was almost contrarian. Resident Evil 6 had sold millions, even if critics and longtime fans felt the series had lost its identity. Capcom chose to trade the biggest-possible mainstream ceiling for something more valuable: creative clarity and trust.

They abandoned action-horror excess and leaned back into survival horror fundamentals. That willingness to admit drift—and correct it—ended up being the right call.

4. Global Thinking Requires Global Design

Monster Hunter’s global breakthrough wasn’t primarily a marketing story. It was a product story. Monster Hunter: World wasn’t “localized” for Western audiences after the fact; it was built from the start with Western play expectations in mind. And that required a hard internal admission: what worked brilliantly in Japan wouldn’t automatically translate elsewhere.

5. Quality Over Quantity

We will continue to focus on in-house production for core elements of development as it's difficult to accumulate sufficient experience and expertise through outsourcing alone. Through internal development we aim to further enhance both our development capabilities and our product quality.

Capcom learned this the expensive way in the early 2010s. Outsourcing can keep output high, but it can also dilute the feel of what made a franchise valuable in the first place. Maintaining strong internal development—despite the short-term cost—protects long-term quality, and quality is what keeps IP alive for decades.

6. The Tsujimoto Family Continuity

In 2001, Tsujimoto became chairman and CEO of Capcom. Tsujimoto's older son, Haruhiro, has served as Capcom's President and COO since 2007. His younger son, Ryozo, is a producer of the Monster Hunter series.

In an industry where leadership churn is common, Capcom has had something unusual: continuity. That multigenerational structure helped preserve institutional knowledge—what the company is, what its fans respond to, and what mistakes not to repeat—while still leaving room to evolve when evolution became non-optional.

XII. Analysis: Competitive Position & Investment Considerations

Porter’s Five Forces is a useful way to sanity-check whether Capcom’s comeback is a moment—or a durable position.

Threat of New Entrants: MEDIUM-LOW

Making modern AAA games is brutally expensive, often requiring budgets in the tens or even hundreds of millions of dollars. On top of that, Capcom isn’t starting from scratch each project. Its proprietary RE Engine gives it a meaningful head start versus competitors trying to build comparable tech. And then there’s the part money can’t easily buy: more than 40 years of beloved characters and worlds that players already trust.

Bargaining Power of Suppliers: LOW

Because Capcom develops largely in-house, it’s less dependent on external studios than many peers. Talent is the key “supplier” in games, and that market is competitive—but Capcom has acted like it understands the lesson from the 2010s. From 2022 onward, it implemented measures aimed at recruiting and retention, including raising average annual base salary for full-time employees by 30%, shifting to a more performance-linked bonus structure, and introducing stock-based compensation. By March 31, 2025, Capcom reported 2,846 developers.

Bargaining Power of Buyers: MODERATE

Players have endless choices, and switching to another game is easy. But Capcom’s big franchises come with real loyalty. Digital distribution also shifts leverage away from retailers—there’s no longer a handful of physical gatekeepers controlling shelf space.

Threat of Substitutes: MODERATE

Games compete with everything: streaming, social media, and the rest of the modern attention economy. The counterpoint is that games do something those substitutes can’t: they’re interactive, skill-based, and social in a way passive entertainment isn’t.

Competitive Rivalry: HIGH

This is still one of the most competitive industries on earth. Nintendo, Sony, and Microsoft fight for mindshare and platform positioning, while other major publishers battle for releases, and indies constantly pressure the market with breakout hits. Capcom wins here not by avoiding rivalry, but by shipping consistently great games and compounding its advantages over time.

Hamilton’s Seven Powers helps explain why Capcom’s position has become harder to dislodge.

Scale Economies: The RE Engine is the centerpiece. Once you’ve paid to build it, every additional game spreads that cost out—and every team that improves it makes the next project cheaper and better. Digital distribution adds its own scale benefits as volume grows.

Network Effects: Capcom doesn’t have pure platform-level network effects, but it gets a version of them in multiplayer franchises. Monster Hunter and Street Fighter both become more valuable as more people play.

Counter-Positioning: Capcom’s emphasis on owned IP and in-house development stands apart from publishers that lean on acquisitions or heavily licensed properties.

Switching Costs: For any single title, switching costs are low. But franchise loyalty creates a softer kind of lock-in: fans have history with these worlds, and they’ve built skills and habits that make them more likely to come back.

Branding: This is obvious but enormous. Resident Evil, Monster Hunter, and Street Fighter carry decades of meaning. The name alone can move units—if the game earns it.

Cornered Resource: The RE Engine functions like a cornered resource: proprietary, deeply integrated into how Capcom builds, and not something rivals can quickly copy.

Process Power: Capcom now has repeatable processes around franchise management, remakes, and digital catalog monetization. In games, operational excellence is often invisible—until you see how rare consistent output actually is.

Key Metrics to Monitor

If you’re tracking whether Capcom is sustaining its edge, three signals matter most:

1. Digital Sales Ratio: Now above 90%, this is the clearest window into margin structure and global reach. If it holds or improves, the catalog flywheel is working.

2. RE Engine Title Velocity: How quickly Capcom can ship high-quality RE Engine titles is a real-time measure of productivity gains from its tech platform.

3. Catalog Sales as Percentage of Total: Often cited around 10–15%, this shows how effectively Capcom turns old games into evergreen assets. The higher it goes, the more resilient the business becomes.

Risk Factors

Franchise Fatigue: Capcom’s success is concentrated in a handful of mega-franchises. If fan interest cools, results can swing. The slower-than-expected performance of Monster Hunter Wilds after its strong launch is worth watching.

Technology Transition: New console generations and continued shifts in PC hardware could require major RE Engine investment. The engine was designed for current-generation needs, and staying at the cutting edge is never optional for long.

Talent Retention: Compensation has improved, but games are still a people business. Losing key creative leaders—like what happened in the early 2010s—can have outsized impact.

Currency Exposure: With significant overseas sales, yen fluctuations can meaningfully affect reported results.

The Capcom story, at its core, is adaptation. Cotton candy machines to pachinko. Pachinko to arcade cabinets. Arcade cabinets to console hits. Console hits to a digital, global catalog machine.

As of December 23, 2025, Capcom’s market cap stood at $12.29B.

What began with a blacksmith’s son hustling in 1960s Osaka became one of the deepest IP libraries in all of gaming. The journey from the low point—when Resident Evil 6 and Street Fighter V symbolized a company chasing trends and losing its identity—to today’s era of record profits is proof that corporate rehab is possible. But Capcom’s version wasn’t magic. It required admitting drift, investing in foundational technology, and trusting creative instincts even when they capped the short-term ceiling.

For the industry, Capcom is a template for franchise management in the digital age. For investors, it’s a case study in how moats get built through technology platforms and enduring IP. And for business historians, it’s a reminder that long-term stewardship—especially the Tsujimoto family continuity—can be a competitive advantage in an industry that rarely slows down enough to think past the next release window.

The cotton candy salesman built something that lasted. And the monsters he helped unleash—both the ones in Raccoon City and the ones living on balance sheets as evergreen franchises—are still on the hunt.

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music