Toho Co., Ltd.: From Kabuki Theaters to Kaiju Global Empire

I. Introduction & Episode Roadmap

March 10, 2024. The Dolby Theatre in Los Angeles.

A small team from Japan hears their film called for Best Visual Effects—and they don’t just stand up. They spring into motion, hustling toward the stage with tiny Godzilla figurines in hand, like they can’t quite believe this is real.

Because what they’ve just pulled off is absurd on paper. They’ve beaten four Hollywood behemoths, including Marvel’s Guardians of the Galaxy Vol. 3, a movie that reportedly cost hundreds of millions to make. And the winner is a Japanese monster film made for about $15 million, with a VFX team of roughly 35 artists back in Tokyo.

Godzilla didn’t just return. Godzilla won an Oscar.

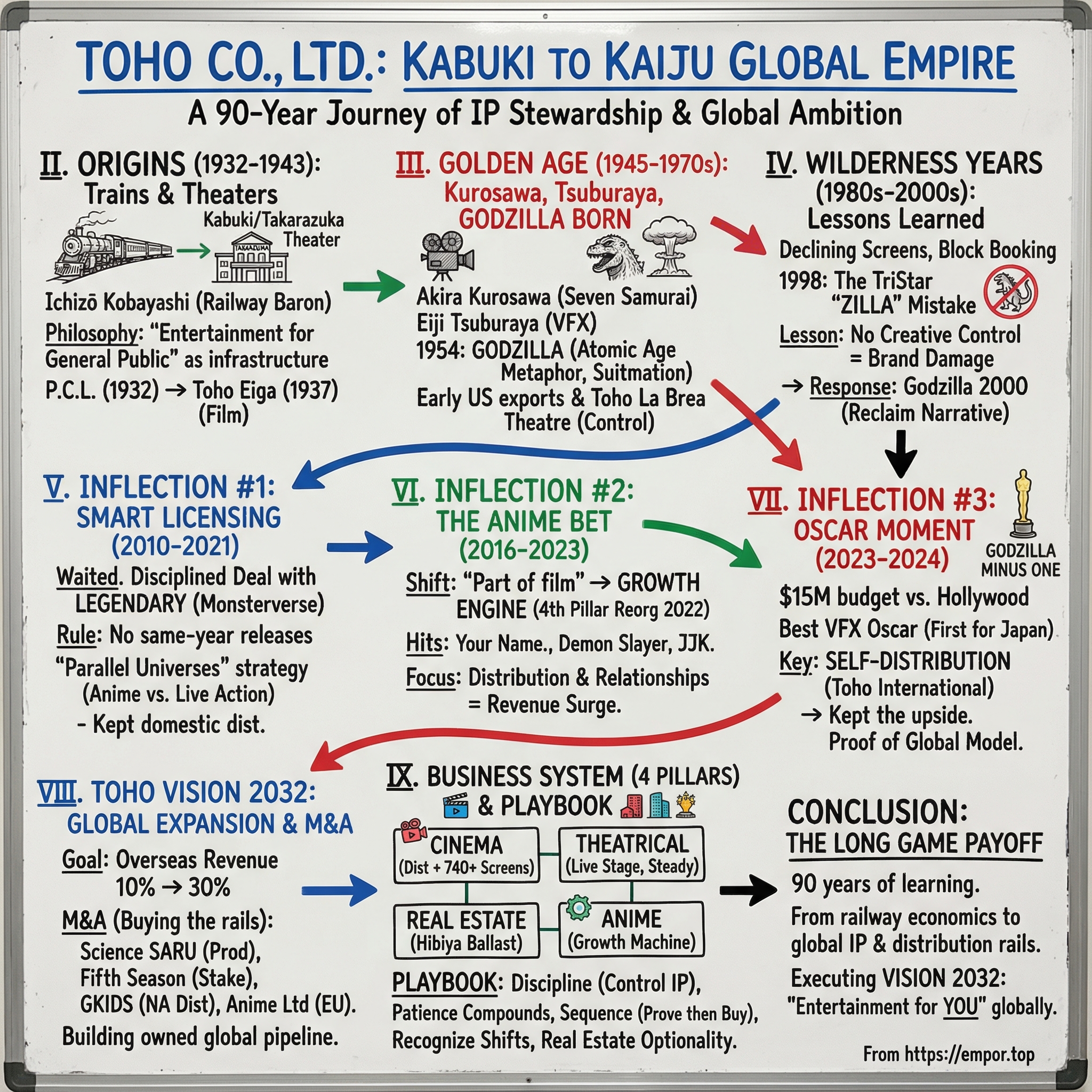

So how did a company that started in 1932—built around theaters, backed by a railway baron—end up here, outmaneuvering the biggest entertainment machine on Earth?

Toho Co., Ltd. is, technically, a Japanese entertainment company headquartered in Chiyoda, Tokyo. It produces and distributes films, runs cinemas, and stages live theater. It’s also a core company in the Hankyu Hanshin Toho Group. All true. None of that captures what Toho really is: one of the most quietly dominant, best-run IP companies in modern entertainment.

This is the studio that gave the world Ishirō Honda and Eiji Tsuburaya’s kaiju and tokusatsu films. The studio that backed Akira Kurosawa. The studio that became a crucial distributor for animated films produced by Studio Ghibli, Shin-Ei Animation, TMS Entertainment, CoMix Wave Films, and OLM, Inc. In Japan, Toho has released the majority of the country’s highest-grossing films. And through its subsidiaries, it’s also the largest film importer in Japan.

Then there’s Doraemon—distributed by Toho since 1980—now the highest-grossing film series in Japan, animated or otherwise, and one of the most successful non-English-language franchises ever.

But Toho isn’t just a great studio. It’s a masterclass in three things: patient stewardship of IP over decades, the discipline to say “no” to Hollywood when the terms are wrong, and the ambition to evolve from a domestic theater operator into a global entertainment powerhouse. Along the way, it built the most enduring movie monster in history, helped define what “cinema” means in Japan, and positioned itself as a key piece of anime’s global expansion.

Today, Toho operates across four core areas: Cinema, Theatrical, Real Estate, and Anime. The mission is simple and surprisingly consistent across generations: “to widely provide inspiring entertainment to the general public.” As it gears up for its 100th anniversary in 2032, it’s also rallied around a new corporate slogan: “Entertainment for YOU.”

This is the story of how an enterprise born from the intersection of trains and kabuki theaters created Godzilla, survived changing tastes and collapsing movie screens, and then—nearly a century later—walked into Hollywood and won with a $15 million bet. And it’s also the story of what Toho’s TOHO VISION 2032 strategy signals about the future of global entertainment.

II. Origins: The Railway Baron's Theater Empire (1932-1943)

Toho’s story doesn’t start with a camera. It starts with a train.

In the Kansai region, a businessman named Ichizō Kobayashi was busy reinventing what a railway company could be. Yes, he built rail lines. But he also understood something more important: trains don’t just move people. They can create demand. If you give riders a reason to go somewhere—shopping, sports, theater—they’ll fill your cars on purpose.

Kobayashi was an industrialist and politician, sometimes referred to by his pseudonym Itsuō. He founded Hankyu Railway, created the Takarazuka Revue, and would go on to found Toho. He even served as Japan’s Minister of Commerce and Industry from 1940 to 1941.

His early life was turbulent. Born on January 3, 1873, in Kawarabe village in Yamanashi Prefecture, he came from a wealthy merchant family, but his mother died immediately after his birth and his father left soon after. He was raised by relatives. The name “Ichizō,” meaning “one-three,” came directly from his birthday: January 3. He graduated from Keio Gijuku in 1892, spent 14 years at the Mitsui Bank, and then, in 1907, founded the Mino-o Arima Electric Railway Company.

Then the real playbook emerged.

Kobayashi didn’t just lay tracks—he built destinations at the end of them. He established the Takarazuka Revue. He created the Hankyu professional baseball team. The strategy was simple: give people entertainment, and they’ll ride your trains to get it. Build department stores next to the platforms, and those passengers become shoppers. Over time, he developed towns along the line in the Hanshin area, turning the railway into the spine of a broader lifestyle business. Other railway companies in Japan would copy the model.

By 1932, Kobayashi aimed that model at the biggest stage in the country: Tokyo.

That year, he created what would become Toho as the Tokyo-Takarazuka Theatre Company, centered on the Tokyo Takarazuka Theatre. Toho’s own company history, published in 2010, points to this as the beginning—an extension of the Takarazuka Revue, the all-female musical theater troupe Kobayashi had established back in 1914 in Kansai.

But this wasn’t just about bringing a successful show to a new city. Kobayashi wanted to shape an entire district. He set his sights on Hibiya, developing it into a premier entertainment zone—deliberately positioned away from the seedier associations of existing theater areas like Asakusa.

Even the name captured the strategy. “Toho” is an acronym combining the kanji “to” (東) from Tokyo and “ho,” an alternate reading of the kanji for “takara” (宝) in Takarazuka.

In its early years, Toho was primarily a theater company. It managed major venues like the Tokyo Takarazuka Theatre and the Imperial Garden Theater, and it oversaw much of the kabuki scene in Tokyo. For years, Toho and Shochiku effectively held a duopoly over Tokyo theaters—a rivalry that would go on to shape Japanese entertainment for decades. Shochiku, founded in 1895, was the older and more established company, with deep roots in kabuki promotion. Toho was the upstart with a new kind of muscle: modern facilities, ambitious leadership, and railway-backed resources.

Film came next—and it came fast.

A key piece was Photo Chemical Laboratory, or P.C.L., founded in 1932. It handled processing and early sound-film experimentation, and it became the technical beachhead for Kobayashi’s move into movies. Kobayashi acquired P.C.L. in 1936, and in 1937 it merged with other studios to form Toho Eiga Co., Ltd., formalizing Toho’s motion picture operations.

Underneath all of this was a philosophy Kobayashi set early, and that Toho would carry for nearly a century: “to widely provide inspiring entertainment to the general public.” It wasn’t a slogan so much as a business thesis. Entertainment shouldn’t be reserved for elites. It should be built for scale.

The timing couldn’t have been better. Japan was entering the age of talkies, and a wave of ambitious businessmen and young technicians—people who hadn’t been part of the old film world—poured into the industry. Toho, still young, well-funded, and less constrained by tradition, was perfectly positioned to ride that technological shift.

III. The Golden Age: Kurosawa, Tsuburaya, and the Birth of Godzilla (1945-1970s)

World War II left Japan’s institutions shaken, and Toho wasn’t spared. But out of the rubble—and the turmoil—came the creative engine that would define the studio for generations.

The first big postwar chapter was labor. Under the Occupation government, unions were encouraged, and Toho’s workforce organized aggressively. In October 1946, a general strike swept the film industry. At Toho, the conflict escalated into a split: ten of the studio’s top stars, led by Denjirō Ōkōchi, broke away from the main union along with 445 employees. When the strike finally resolved, a closed-shop provision with the main union helped push the breakaway faction into forming its own company: Shintoho. A competitor, created from inside Toho’s own walls.

And yet, while the business was fighting itself, the creative side was quietly stacking talent.

Director Kajirō Yamamoto helped solidify Toho’s production system. Mikio Naruse made films that would become classics, including Floating Clouds. And under Yamamoto’s guidance, a young recruit was being trained—still raw, still learning, but already unmistakable.

Akira Kurosawa.

It’s one of those “only in Toho” facts: this same company that would unleash Godzilla also made Seven Samurai (1954) and later HOUSE (1977), Nobuhiko Obayashi’s wildly inventive, genre-bending horror film. Toho wasn’t one thing. It was a factory for whatever Japanese cinema could become.

Kurosawa’s run at Toho produced some of the most influential films ever made. Rashomon cracked open the West’s awareness of Japanese cinema and won the Golden Lion at Venice in 1951. Seven Samurai became a foundational text—its structure and character archetypes echoing through everything from The Magnificent Seven to Star Wars. Toho’s relationship with Kurosawa across the 1940s through the 1960s was long, and often difficult, but historically productive in a way that’s hard to overstate.

But 1954 wasn’t just Kurosawa’s year. It was also the year Toho created a different kind of icon—one that would come to define the studio’s global identity more than any samurai ever could.

Godzilla began, almost accidentally, as the replacement for a failed international project. Producer Tomoyuki Tanaka had been working on a Japanese-Indonesian co-production called In the Shadow of Glory. Then the Indonesian government denied visas to Toho’s crew, citing anti-Japanese sentiment and political pressure, and the film collapsed. Tanaka boarded a plane back to Japan after a last attempt to salvage the deal failed—and somewhere over the clouds, he reached for a new idea: a giant monster movie.

The concept landed because Toho already knew the market was ready. The 1952 re-release of King Kong had done great business. The Beast from 20,000 Fathoms (1953) had proven there was an audience for atomic-age terror, with a giant creature awakened by nuclear testing. Tanaka pitched his monster as the new project, and he convinced executive producer Iwao Mori to swap it in.

Commercial logic met national trauma. Hiroshima and Nagasaki were not distant memories. Neither was the Lucky Dragon No. 5 incident, when a Japanese fishing boat was contaminated by fallout from U.S. hydrogen bomb tests. Godzilla wasn’t just a monster. He was the embodiment of the atomic age: a walking consequence, a force no one could negotiate with.

Director Ishirō Honda and special effects pioneer Eiji Tsuburaya turned that idea into something physical. Toho couldn’t afford stop-motion on the scale of Hollywood’s creature features, so Tsuburaya leaned into a constraint and made it a signature: suitmation—an actor in a monster suit tearing through detailed miniature sets. What began as necessity became an entire visual language, and it would define kaiju cinema for decades.

Godzilla premiered on November 3, 1954, and it hit like an alarm bell. Dark, mournful, and unmistakably shaped by nuclear imagery, it was elevated by Akira Ifukube’s score and by the film’s willingness to treat destruction as tragedy, not spectacle. Over time, the series would earn a Guinness World Records distinction as the longest continuously running film franchise—ongoing since 1954, with hiatuses of varying lengths.

In total, there are 38 Godzilla films: 33 Japanese films produced and distributed by Toho, and five American films—one by TriStar Pictures and four as part of Legendary’s Monsterverse.

Godzilla’s success also pushed Toho to think beyond Japan. After several film exports to the United States in the 1950s, facilitated through Henry G. Saperstein, Toho took over the La Brea Theatre in Los Angeles so it could exhibit its own films without handing everything to a distributor. From the late 1960s into the 1970s, it was even known as the Toho Theatre. Toho also operated a theater in San Francisco and opened one in New York City in 1963.

This wasn’t just expansion. It was an early glimpse of a principle Toho would keep rediscovering across the next century: if you can control distribution, you control your destiny.

IV. The Wilderness Years: Declining Screens, Changing Tastes (1980s-2000s)

The golden era couldn’t last forever. As Japan’s economy boomed and daily life modernized, the way people consumed entertainment changed—and Toho ran into a problem that hits a studio right where it hurts: the audience stopped showing up in the same places.

Across the country, movie screens steadily disappeared. From 1960 to 1990, the number of screens in Japan shrank dramatically. By 1991, there were only about 2,000 screens left nationwide. Roughly 600 were reserved exclusively for Japanese films—most of them produced and/or distributed by the same three giants that had long dominated the business: Toho, Shochiku, and Toei.

Fewer screens meant fiercer competition for every slot. Toho held its ground with a system that was effective—and widely disliked: block booking. Instead of letting theater owners pick and choose individual films, Toho could require them to take a package deal. Critics argued it squeezed out smaller producers and dulled innovation. And even as the market started to shift in the late 1990s, Toho wasn’t in a hurry to change. By mid-1999, it had no plans to abolish block booking, even as pressure built heading into the 21st century.

Then came the twist: right as the domestic market was tightening, Godzilla was about to get what should’ve been the ultimate global upgrade—his first major Western adaptation.

The deal dated back to 1992, when TriStar signed with Toho to produce a trilogy of American-made Godzilla films. But the fact that the first entry didn’t arrive until six years later tells you everything about how hard it was to get to the finish line.

Godzilla hit theaters on May 20, 1998. Reviews were brutal, but the box office looked big: $379 million worldwide. The problem was that the movie was also enormously expensive, with a reported production budget in the $130–150 million range plus major marketing spend. Even with a profit on paper, it was widely viewed as a disappointment—and Sony, TriStar’s parent company, had expected more.

But the deeper damage wasn’t financial. It was brand damage.

Roland Emmerich’s film didn’t just reinterpret Godzilla—it rebuilt him. This Godzilla was faster, leaner, more iguana-like, and only a fraction of the size fans associated with the character. For longtime audiences, that wasn’t a creative choice. It was a betrayal of what Godzilla meant.

Toho, which distributed the movie in Japan, publicly supported it during marketing. But over time, studio representatives made it clear they hated what it did to Godzilla’s image. Fans were even louder. And that backlash landed at exactly the wrong moment: Toho hadn’t made a Godzilla movie since 1995, when the previous series ended with Godzilla’s death in Godzilla vs. Destoroyah.

So Toho did what it does when the market throws a punch: it reclaimed the narrative.

The studio returned to the character with Godzilla 2000, launching what became known as the “Millennium” series. Internally and externally, the message was simple: if the American version made people miss the “real” Godzilla, Toho would remind them who owned “real.”

And then came the sharpest signal of all—Toho’s verdict on TriStar’s creature. The studio began referring to it as “Zilla,” framing the name as a satirical label for a counterfeit Godzilla product. In other words, strip out the “God,” and you’re left with a thing that looks like Godzilla, but isn’t.

Toho didn’t just dislike the film. It quarantined it.

Even with a huge global gross, two planned sequels were canceled. An animated TV series was produced instead. TriStar ultimately let the license expire in 2003.

For Toho, the takeaway was painfully clear, and it would shape everything that came next: when you license your franchise without creative control, you’re not monetizing your IP. You’re gambling it.

The TriStar episode became a scar—and a playbook. For more than a decade afterward, Toho treated Hollywood conversations with extreme caution, determined not to hand over its crown jewel again without protections.

V. Inflection Point #1: The Legendary Deal & IP Licensing Masterclass (2010-2021)

After the TriStar mess, Toho did something most entertainment companies struggle to do: it waited.

No frantic “relaunch.” No desperate Hollywood reset. Toho kept making its own movies, kept the character alive at home, and treated Godzilla like what he actually was: a long-term asset, not a quick payday. And when Hollywood finally came knocking again, Toho didn’t just sign a deal. It wrote a rulebook.

In 2010, Legendary acquired the rights to produce an American Godzilla film after producer Brian Rogers approached the company while trying to secure funding for Yoshimitsu Banno’s Godzilla 3-D project during Toho’s Godzilla hiatus. Legendary looked at the opportunity and made a different call: instead of backing a short IMAX concept, it wanted to build a full feature—and a franchise. So it negotiated directly with Toho for the rights.

The timing mattered. TriStar had considered making a GODZILLA 2, but eventually walked away and let its rights revert to Toho in 2003. That reset the board and made the 2010 Legendary deal possible.

But here’s the key: this time, Toho wasn’t going to relive 1998.

The contract Toho struck with Legendary included a simple, powerful guardrail: Toho was prohibited from releasing a Toho-produced Godzilla film in the same year that Legendary released one of its own. It’s easy to read that as Toho giving something up. In reality, it was Toho protecting the entire ecosystem.

Legendary got breathing room to build momentum without competing against the original creator in the same theatrical window. Toho kept the right to make its own Godzilla films—on its own terms—without surrendering creative identity. It was a compromise engineered to prevent cannibalization while preserving independence.

Distribution was another scar Toho wasn’t interested in reopening. Every Monsterverse film has been distributed by Warner Bros. (outside Japan), even as Legendary’s distribution partners changed over time. In Japan, Toho distributed the Godzilla films itself. After the brand damage from the TriStar era, keeping control of the home market wasn’t optional—it was essential.

And the deal didn’t stop at Godzilla. Legendary expanded into Toho’s broader kaiju bench. At San Diego Comic-Con in 2014, Legendary confirmed it had acquired the licensing rights to Mothra, Rodan, and King Ghidorah.

By 2020, Legendary’s license to Godzilla expired—but it didn’t end. The relationship continued, and Toho announced in July 2022 that Godzilla would appear in a sequel to Godzilla vs. Kong. Legendary also announced in January 2022 that it was developing a live-action TV series centered on Godzilla and other Titans.

This is where Toho’s real sophistication shows up: the “parallel universes” strategy.

The contract restrictions were about theatrical releases. They did not extend to television. So in 2021, Toho released the anime series Godzilla Singular Point just weeks after Legendary released Godzilla vs. Kong. And in 2023, Toho released Godzilla Minus One in the same month that Legendary’s Monarch: Legacy of Monsters arrived.

That wasn’t Toho “finding loopholes.” That was Toho maximizing the same IP across formats while keeping each project out of the other’s way.

Toho stayed involved, too. Hiro Matsuoka and Takemasa Arita served as executive producers on behalf of Toho for the Apple TV+ Monsterverse series, with Godzilla licensed to Legendary as part of the long-running film relationship.

The result was night-and-day from TriStar. Legendary treated the property with respect, the Monsterverse became a global franchise, and Toho proved a point that would define its next era: licensing can be powerful, but the real leverage comes when you can pair licensing with your own production—and, eventually, your own distribution.

VI. Inflection Point #2: The Anime Bet & Demon Slayer Effect (2016-2023)

While the Legendary partnership helped rehabilitate Godzilla internationally, Toho was quietly making an even bigger swing in a different corner of Japanese entertainment: anime.

What had once been “part of the film business” started turning into a growth engine with its own gravity. Toho’s anime operating revenue climbed fast—from ¥24.2 billion in fiscal 2023 (9.9% of consolidated operating revenue), to ¥46.5 billion in fiscal 2024 (16.4%), and then to ¥55.4 billion in fiscal 2025 (17.7%). In just two years, it more than doubled, and it was taking up nearly a fifth of the company’s operating revenue.

The growth wasn’t subtle inside the division, either. In the fiscal year ending February 2024, Toho Animation revenue rose 91% to ¥46.3 billion (about US$299 million). Overseas sales climbed nearly 78% to ¥15.8 billion (about US$102 million)—nearly triple what it was two years earlier—and overseas was now roughly one-third of Toho Animation’s sales.

What drove it wasn’t Toho suddenly becoming an animation factory. The bet was distribution and relationships: becoming the go-to theatrical distributor for anime and then riding the flywheel into streaming, merchandise, and international expansion. Titles like Spy × Family, Jujutsu Kaisen, My Hero Academia, and Haikyu!! pushed revenue across all of those channels.

And Toho was explicit about where it wanted to win. President Hiroyasu Matsuoka said, “North America is superior in terms of profits and revenue,” pointing to Makoto Shinkai’s Suzume as an example—where Toho negotiated 50% of box office revenue. That kind of split is meaningfully better than what distributors typically get, and Toho leaned into its bargaining power to capture more of the upside from the anime theatrical boom.

The Shinkai relationship had already shown what was possible. Your Name (2016) didn’t just become a hit—it became proof that anime could behave like a true global theatrical event, including in Western markets. For Toho, it was a pivot point: anime wasn’t a niche category you “also” distributed. It could be a pillar.

So Toho made it one.

In 2022, the company formally reorganized its operations into four pillars: film, theater, real estate—and anime. Carving anime out into its own segment, rather than leaving it buried under film, was a statement of intent. This wasn’t a side hustle anymore. It had its own scorecard, its own leadership, and its own mandate to grow, especially overseas.

And the results made the strategic move look inevitable: from ¥24.2 billion in fiscal 2023 to ¥55.4 billion in fiscal 2025, anime went from “important” to “indispensable” in the Toho story.

VII. Inflection Point #3: Godzilla Minus One & The Oscar Moment (2023-2024)

Everything Toho had learned—from the TriStar era’s hard lesson about creative control, to the Legendary partnership’s disciplined licensing, to anime’s reminder that distribution is where the leverage lives—collided in one film.

Godzilla Minus One.

At the 2024 Academy Awards, Toho’s Japanese monster movie, made for about $15 million, won Best Visual Effects. In the same category were four Hollywood tentpoles, including Marvel’s Guardians of the Galaxy Vol. 3, a film with a budget reported at $250 million.

That’s not just an upset. It’s an industry-level statement.

It was also historic. Godzilla Minus One became the first Japanese film ever nominated for Best Visual Effects, and the first film in the franchise’s 70-year history to earn an Oscar nomination at all. Then it went one step further: the VFX team became Japan’s first-ever winner of the Best Visual Effects Oscar. It was the first time in decades that a non-U.S. studio film had won the category.

And the production math made the win feel almost impossible. Yamazaki’s team—about 35 artists—delivered 610 VFX shots on a budget under $15 million. Hollywood does that kind of work with massive vendor networks and huge crews. Toho did it with a small, tightly coordinated team, and it held up on the biggest screen in the world.

Along the way, director Takashi Yamazaki also entered rare company: he became the first director to be nominated for a visual effects Oscar since Stanley Kubrick.

The box office backed up the moment. Godzilla Minus One grossed $116 million worldwide, finishing as the third-highest-grossing Japanese film of 2023 and surpassing Shin Godzilla as the most successful Japanese Godzilla film. On December 29, 2023, it officially dethroned Shin Godzilla (2016) as the highest-grossing Japanese-made Godzilla film. In January 2024, Toho CEO Hiroyasu Matsuoka said the global performance had exceeded expectations—and helped push Toho’s yearly theatrical income past ¥100 billion for the first time.

In North America, the film reached another milestone: it became the highest-grossing Japanese-language movie released there, and the fifth highest-grossing foreign-language film in the market.

But the most important part of the story wasn’t the trophy or even the box office. It was how Toho got paid.

On December 1, Toho’s subsidiary Toho International distributed the subtitled release in the U.S.—the company’s first wide theatrical self-distribution in North America. Instead of handing the film to an American distributor and taking a smaller slice, Toho kept control. When the movie overperformed, the upside didn’t leak out to intermediaries. It landed back at the studio.

On Oscar night, Yamazaki framed the win as something larger than one movie:

"I do believe that perhaps the success of GODZILLA MINUS ONE will open up a new opportunity for a lot of Japanese filmmakers. I think it's important because Japan is such a small country that we need international box office and revenue to be able to sustain the industry. So this should be the start of something — something bigger I hope for the industry as a whole."

For Toho, it was proof of the full strategy: world-class filmmaking on disciplined budgets, global demand for Japanese stories, and—finally—the capability to distribute directly overseas.

A sequel, Godzilla Minus Zero, is set to be released in 2026.

VIII. The Global Expansion: TOHO VISION 2032 & M&A Spree (2022-Present)

Godzilla Minus One didn’t just bring Toho an Oscar and a global box office surge. It gave the company something even more valuable: proof that Toho could compete internationally on its own terms—and keep the upside when it did.

So Toho moved from “careful, selective expansion” to an actual blueprint for becoming a global entertainment company. That blueprint has a name: TOHO VISION 2032.

The headline goals are straightforward. By its 100th anniversary in 2032, the Toho Group plans to use a growth strategy powered by M&A to reach operating profits of more than ¥75.0 billion and ROE of more than 10%. And, just as important, Toho wants to increase its overseas net operating revenue ratio from about 10% to 30%.

That’s a big statement for a company that, for most of its history, dominated Japan first and treated the rest of the world as opportunistic upside. Tripling the overseas share means building a real international business—distribution, marketing, relationships, and on-the-ground capability. And Toho’s path to get there has been unusually direct: buy the missing pieces.

Science SARU Acquisition:

Toho announced that its board approved the acquisition of all shares of anime studio Science SARU, effective June 19, making it a consolidated subsidiary.

Science SARU was co-founded on February 4, 2013 by director Masaaki Yuasa and animator Eunyoung Choi. The studio built a reputation for distinctive, high-craft work, including Yuasa’s 2017 film Lu over the wall, which won the Animation Grand Prize at the Japan Media Arts Festival Awards and the Cristal for a Feature Film at the Annecy International Film Festival, and his Golden Globe-nominated 2022 film INU-OH. Its other projects include Ping Pong, Devilman Crybaby, Keep Your Hands Off Eizouken!, and Scott Pilgrim Takes Off.

For Toho, the point is clear: strengthen its ability to produce high-quality anime in-house and accelerate the anime business that’s already been compounding so quickly. This also fits the direction Toho had been moving in. In 2022, it acquired a controlling stake in TIA (TOHO Interactive Animation) and made it a subsidiary under the new name TOHO animation STUDIO.

Fifth Season Investment:

Then there’s live-action.

Fifth Season, the production and distribution company previously known as Endeavor Content, secured a $225 million strategic investment from Toho International. In return, Toho received a 25% equity stake.

Fifth Season’s slate includes Apple TV+’s Severance, as well as Max’s Tokyo Vice, Hulu’s Nine Perfect Strangers, and Hulu’s Life & Beth. After the deal, Fifth Season was valued at $900 million.

Toho president Hiro Matsuoka framed it as a deliberate widening of the aperture: “We believe that this collaboration will be a significant step towards challenging the global market, not only in the field of animation where Toho has excelled, but also in the realm of live-action content.”

GKIDS Acquisition:

If Science SARU builds more supply, and Fifth Season expands formats, GKIDS is about the part Toho has learned to obsess over: distribution.

Toho announced it reached an agreement to acquire a 100% equity share of GKIDS, Inc., the Academy Award-winning North American animation producer and distributor.

Founder Eric Beckman and Dave Jesteadt have run GKIDS together since the company released the Academy Award-nominated The Secret of Kells as a two-person operation in 2009. Since then, GKIDS has grown into a major force in U.S. animation, earning thirteen Best Animated Feature nominations at the Academy Awards, including a win for Hayao Miyazaki’s The Boy and the Heron.

In context, the move makes Toho’s logic even more obvious. Toho had already acquired Science SARU and made an equity investment in Los Angeles-based Fifth Season. With GKIDS, it adds a proven North American theatrical and home entertainment distribution, marketing, and sales operation.

Toho also noted that the Toho Group already holds a 45% share of the Japanese distribution market. The message: the company knows how to win through distribution at home—and now it’s buying the infrastructure to do it abroad.

European Expansion:

Toho didn’t stop with North America.

In late 2024, alongside the GKIDS acquisition and the launch of Toho Entertainment Asia in Singapore, Toho expanded its regional footprint so it could operate across North America and Asia with real local presence. Europe was the next step.

Toho Global announced plans to establish European operations in London before the end of the year. As part of that strategy, Toho Global will acquire 100% of Anime Limited from Plaion Pictures, bringing the U.K.-based distributor into its European structure, and it will enter into a strategic alliance with Germany’s Plaion Pictures.

Toho’s pitch is that this is about meeting demand by pairing direct distribution capability—especially in markets like the U.K. and France—with established partners across the region.

And zooming out, the through-line across all of this is consistent: Toho is building an owned global pipeline for Japanese entertainment. Instead of licensing IP to third parties that control marketing, release strategy, and customer relationships—and keep much of the margin—Toho is buying the rails.

That’s what TOHO VISION 2032 really is. Not just “more overseas.” A plan to connect Toho’s Japanese productions, creators, and studios more directly with audiences worldwide, with Toho controlling more of the value chain along the way.

IX. The Business Model Deep Dive: Four Pillars

To understand Toho, you have to stop thinking of it as “a movie studio” and start thinking of it as a system. A diversified, vertically integrated entertainment company that can make hits, sell tickets, monetize IP, and still stay steady when the cycle turns.

Toho’s business is organized around four key areas: Cinema, Theatrical, Real Estate, and Anime.

Cinema Operations:

The Film segment covers theatrical distribution, domestic distribution of films, cinema management, the use of anime content, home video package sales, and art production for video works. Toho also operates Japan’s largest theater chain—around 740 screens—with roughly a 30% share of the exhibition market.

On top of that, the Toho Group holds about 45% of Japan’s distribution market.

That combination is the engine. When Toho backs a film, it can earn not just as a producer or distributor, but also at the box office through its own theaters. In other words: it doesn’t just participate in demand. It owns a meaningful chunk of the pipe.

Theatrical Operations:

The Theater segment is the company’s original DNA: producing and staging live performances, selling tickets, and managing venues. The Imperial Theatre, the Nissay Theatre, and other properties remain core assets.

And it’s not just legacy—it still performs. Productions like Moulin Rouge! The Musical and MOZART! at the Imperial Theatre sold out, and The Bones and Scorn at Theatre Creation played to a full house.

This segment ties directly back to Ichizō Kobayashi’s original thesis: entertainment as infrastructure. It helps generate steady cash flow, and it keeps Toho culturally central in Japanese show business—not just on screens, but on stage.

Real Estate:

The Real Estate segment handles leasing, maintenance, and property management. Toho’s Hibiya district holdings—prime real estate in the heart of Tokyo—are the quiet stabilizer in a business that can otherwise swing wildly from hit to miss.

The advantage is simple. When entertainment revenue dips—during downturns, shocks, or disruptions like COVID—rental income doesn’t vanish. And when entertainment demand surges, those same properties benefit as the district becomes more valuable as a destination.

Anime:

In addition to Toho’s three long-standing pillars—film, theater, and real estate—anime has become the fourth.

Toho has said it will move IP business and the Anime business into their own segment starting in fiscal year 2026, separated from the Film business segment. The company’s highlighted subsidiaries and affiliates now include Science SARU, TOHO animation STUDIO, and North American distributor GKIDS. It also lists partial equity stakes in companies including CoMix Wave Films, Bandai Namco Holdings, and Orange.

In practice, this is Toho formalizing what the numbers have already been saying: anime isn’t “part of film” anymore. It’s a standalone growth machine—and increasingly, the most global part of the company.

Ownership Structure:

Toho’s controlling shareholders sit within the Hankyu Hanshin Toho Group: Hankyu Hanshin Holdings (12.81%), Hankyu Hanshin Properties (8.51%), and H2O Retailing (7.67%).

It’s a straight line back to Toho’s origins in Kobayashi’s railway-and-real-estate empire—and it matters. This structure tends to create patient capital and long-term thinking, plus strategic ties to real estate and retail that reinforce Toho’s broader model.

Distribution Subsidiaries:

Toho’s distribution reach is amplified through a set of specialized subsidiaries. Toho-Towa is the exclusive theatrical distributor for Universal Pictures in Japan. Towa Pictures handles exclusive theatrical distribution in Japan for Paramount Pictures and Warner Bros. The broader group includes Toho Pictures Incorporated, Toho International Inc., Toho Music Corporation, and Toho Costume Company Limited.

Through these businesses, Toho is also the largest film importer in Japan.

That makes Toho a two-way gatekeeper: exporting Japanese content outward while importing Hollywood and global content into Japan. Few companies get to sit on both sides of that flow.

Financial Performance:

The operating momentum behind this model has been showing up in Toho’s results.

For the six months ended August 31, 2024, Toho reported operating revenue of ¥163,681 million (up 17.2% year on year), operating profit of ¥40,915 million (up 33.0%), ordinary profit of ¥39,781 million (up 21.0%), and profit attributable to owners of parent of ¥26,485 million (up 21.8%).

For the nine months ending November 30, 2024, Toho reported another year-on-year rise: operating revenue increased 15.3%, and profit attributable to owners of parent increased 20.2%. The company also reported an equity ratio of 76.2%, underscoring just how strong the balance sheet is.

And for fiscal year 2024, Toho reported profit of about ¥45.28 billion—up from roughly ¥33.43 billion the prior year.

X. Playbook: Business & Strategic Lessons

Toho’s nine-decade journey isn’t just a great entertainment story. It’s a surprisingly durable playbook for how to build and protect value in a hit-driven, hype-prone industry.

Lesson 1: IP Management Requires Discipline

The 1998 TriStar episode burned a lesson into Toho’s leadership: if you license a franchise without real creative control, you’re not “expanding” the brand—you’re risking it.

Toho openly criticized the TriStar film for damaging Godzilla’s image, going so far as to insist that the 1998 creature be referred to as “Zilla,” as if the “God” had been stripped out. And they didn’t just complain. They responded with Godzilla 2000: Millennium, a deliberate move to put the traditional Japanese Godzilla back on screen and reassert what the character was supposed to mean.

When Legendary came along, Toho didn’t repeat the mistake. The deal structure protected the brand while still capturing the upside: Toho maintained meaningful input and kept the ability to produce its own Godzilla projects on a parallel track. The result was the opposite of 1998—Godzilla’s global equity strengthened instead of eroding, and Toho earned licensing revenue without giving up the future.

Lesson 2: Patience Compounds

Toho waited. More than a decade separated TriStar’s 1998 film and the 2010 Legendary agreement.

In between, Toho kept Godzilla alive in Japan, rebuilt trust with fans through its own releases, and refused to rush back into Hollywood just because Hollywood wanted the logo. That patience changed the negotiating dynamic. When Toho finally re-entered the U.S. market, it did so with a partner positioned to build a franchise—and on terms that preserved Toho’s independence.

Lesson 3: Vertical Integration Timing Matters

One of the cleanest patterns in Toho’s recent strategy is sequencing: prove you can do something, then buy the infrastructure to scale it.

Toho’s moves to acquire GKIDS, Science SARU, and Anime Limited came after it demonstrated international self-distribution capability with Godzilla Minus One. That order matters. Buying distribution before proving you can actually execute overseas would have been a bet on theory. Toho made it a bet on evidence.

This also matches what the company has outlined as its intent: reinforce its IP and anime organizational framework, expand its talent base, strengthen studio capabilities, and develop and distribute high-quality content and IP worldwide. The plan targets major operating profit growth by pushing harder into overseas business and games as key growth areas.

Lesson 4: Recognize Secular Shifts Early

Toho didn’t just “benefit from anime.” It reorganized around it.

By elevating anime into a fourth pillar, Toho made the shift visible internally, measurable financially, and fundable strategically. And the growth that followed—anime revenue more than doubling in two fiscal years—gets to the core point: if you leave an emerging engine buried inside an older category, you risk underinvesting in the very thing that’s becoming your future.

Lesson 5: Real Estate Provides Optionality

Entertainment is volatile by nature. Hits are unpredictable, tastes change, and external shocks can wreck release calendars overnight.

Toho’s real estate holdings—especially its prime assets—act as ballast. They help steady the business during downturns and participate in upside when entertainment demand returns. That stability gives management room to take creative risks that pure-play studios often can’t afford.

Competitive Position Analysis:

From a Porter’s Five Forces perspective, Toho sits in a strong place:

Threat of New Entrants: Low in Japan because incumbency in distribution and exhibition is a real moat. Internationally it’s more mixed, as streaming platforms can bypass traditional gates.

Supplier Power: Moderate. Great creators always have leverage, but investments like Science SARU and relationships like CoMix Wave reduce reliance on outside production capacity.

Buyer Power: Low to moderate. In Japan, distribution channels and theatrical access are concentrated. Overseas, buyers and platforms have more choices, but Toho’s specialization in anime distribution increases its value.

Threat of Substitutes: Meaningful. Streaming is the obvious substitute. But theatrical remains the premium window for event content, and anime has proven it can still draw audiences when it’s treated like an event.

Competitive Rivalry: Moderate domestically, where Toho is dominant. Intense internationally, where major players like Crunchyroll (Sony), Netflix, and Disney fight over anime distribution and licensing.

Hamilton Helmer’s 7 Powers Analysis:

Scale Economies: Real in distribution and exhibition. A large theater network and distribution infrastructure create cost advantages.

Network Effects: Limited directly, but streaming dynamics create indirect network effects as audiences cluster around platforms with strong catalogs.

Counter-Positioning: Toho’s push to self-distribute internationally—rather than defaulting to licensing—runs against the standard playbook and can create an advantage if executed well.

Switching Costs: Present in long-term relationships with studios, creators, and partners.

Branding: Very strong. Godzilla is one of the most recognizable entertainment brands on Earth, and Toho’s presence in anime distribution has been growing quickly.

Cornered Resource: The Godzilla library and decades of production and distribution relationships are difficult to replicate.

Process Power: Increasingly visible in Toho’s ability to deliver world-class results efficiently—highlighted by Godzilla Minus One achieving Hollywood-level impact at a fraction of typical budgets.

Key KPIs to Track:

If you’re tracking Toho going forward, three metrics tell you the most:

-

Overseas revenue as a percentage of total revenue: It’s around 10% today, with a goal of 30% by 2032. This is the clearest scoreboard for global expansion.

-

Anime segment operating profit growth: This is the core growth pillar Toho has elevated, and it reflects whether the “fourth pillar” strategy is working.

-

Self-distributed international releases and performance: The number of releases Toho distributes directly overseas—and how they perform—shows whether the Godzilla Minus One model is repeatable, not just a one-off.

Risk Factors:

Content Hit Dependency: Even well-run studios are still at the mercy of consumer taste. A weak slate can compress margins quickly.

Anime Market Competition: Crunchyroll and Netflix are aggressive. If Toho loses share or pricing power, the anime growth story softens.

Currency Risk: Expanding overseas increases exposure to exchange rate swings that can impact reported results.

M&A Integration: Rapid acquisitions create execution risk. If integration goes poorly, value can evaporate through culture clashes or operational disruption.

Streaming Disruption: Theatrical remains powerful, but long-term shifts toward streaming could pressure windows, margins, and release strategy.

Conclusion

On that March night in 2024, when Takashi Yamazaki and his team held their Oscars, it wasn’t just a win for visual effects. It was the payoff for ninety years of learning—sometimes the hard way—how to build, protect, and expand entertainment at scale.

You can draw a straight line through Toho’s whole history: Ichizō Kobayashi using railway economics to fund culture, the postwar labor battles that reshaped the studio system, the birth of Godzilla as both metaphor and franchise engine, and the TriStar era as a painful reminder of what happens when you hand over an icon without enough control. Then came the more disciplined second act: structuring the Legendary partnership to grow the brand without surrendering it, and building an anime business that turned distribution, relationships, and global appetite into a compounding growth machine.

Godzilla Minus One put all of it on the same stage. A film made for about $15 million that outperformed Hollywood’s biggest players where it counts: on screen, and on the balance sheet. A self-distributed U.S. release that kept more of the upside inside the company. And an M&A strategy that isn’t about collecting trophies—it’s about owning the rails: production capacity, international distribution, and local market presence.

As Toho heads toward its 100th anniversary in 2032, it’s rallying around a simple promise: “Entertainment for YOU — Inspiring People Around the World.” The ambition underneath that line is anything but simple. The test now isn’t whether Toho has a model worth believing in. It’s whether it can execute TOHO VISION 2032—tripling overseas revenue share and turning a Japan-dominant company into a true global media business.

The pieces are on the board: Godzilla, anime, theaters, real estate, and now international distribution infrastructure. Toho has spent nearly a century proving it can play the long game.

Godzilla finally has his Oscar. The only question left is what Toho builds next.

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music