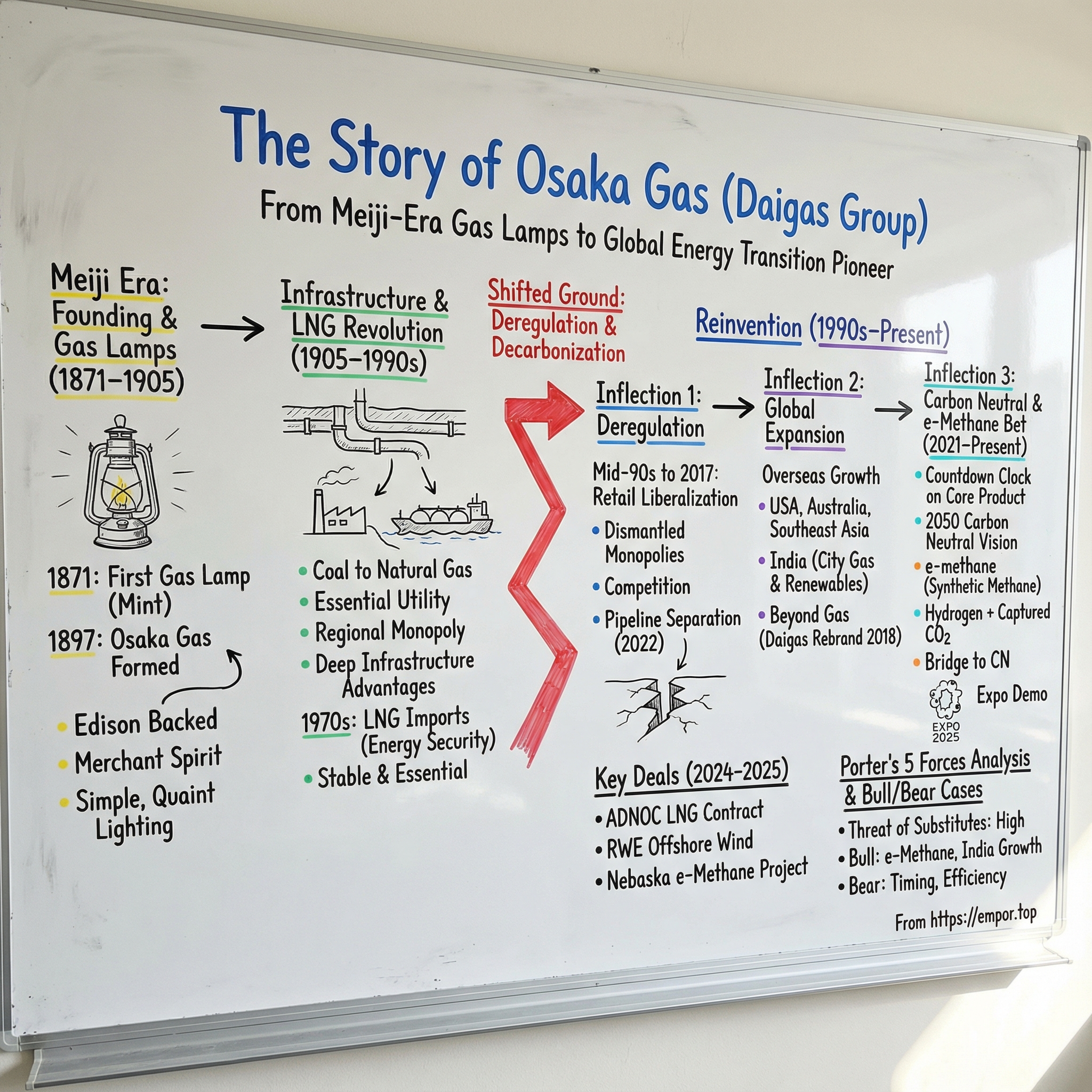

Osaka Gas (Daigas Group): From Meiji-Era Gas Lamps to Global Energy Transition Pioneer

I. Introduction & Episode Roadmap

Picture Osaka in 2025. The city is hosting a World Expo for the second time in its modern history. And amid the national showcases and futuristic prototypes, there’s a pavilion with an intentionally strange name: “Obake Wonderland.” It’s part theme-park, part classroom. Cute ghost characters guide visitors through an idea that sounds like science fiction but is being pitched as infrastructure-compatible reality: e-methane.

That’s the hook. Because behind the whimsy is a very serious corporate thesis. Osaka Gas, a 128-year-old utility, is betting that synthetic methane—made from hydrogen and captured CO2—can keep its gas network relevant in a world that still wants heat and reliability, but not fossil carbon. Supporters call it a pragmatic bridge to carbon neutrality. Critics call it a costly detour from more direct decarbonization.

Osaka Gas Co., Ltd. is based in Osaka and supplies city gas to Japan’s Kansai region, especially the Keihanshin area around Osaka, Kyoto, and Kobe. But it’s no longer just a regional pipeline business. Over the years, it has expanded across the energy value chain—upstream, midstream, and downstream—with projects around the world, including LNG terminals, pipelines, and independent power generation, particularly in Southeast Asia, Australia, and North America.

This story matters because Osaka Gas is a clean case study in a problem hitting regulated utilities everywhere: what happens when your moat is legislated away at the exact moment your core product is put on a climate timer? Japan began deregulating energy in the mid-1990s, then fully liberalized retail electricity in 2016 and retail city gas in 2017—ending the old era of regional monopolies and regulated pricing for small customers. At the same time, geopolitical shocks—from Russia’s invasion of Ukraine to rising tensions in the Middle East—have reminded everyone that decarbonization doesn’t get to ignore supply security. If anything, it has to deliver both.

So here’s the central question that drives everything that follows: How does a 127-year-old regional utility reinvent itself when deregulation destroys its monopoly and decarbonization threatens its core product?

Along the way, we’ll trace themes that stretch far beyond one Japanese company: Japan’s unique vulnerability as a resource-poor island nation; the decades-long rise of LNG as a strategic fuel; the constant tug-of-war between energy security and climate goals; and the audacious e-methane bet—synthetic natural gas created from hydrogen and captured carbon dioxide—as a path to carbon neutrality by 2050 without forcing customers to replace their equipment or rebuild cities.

Founded in 1897 and beginning operations in 1905, Osaka Gas grew into the essential utility for Kansai. Today, it serves roughly 7 million natural gas customers across central Japan. The Osaka Gas Group includes about 140 affiliated companies and employs more than 20,000 people.

And the timing makes this moment feel unusually crisp. Expo 2025 puts Osaka Gas’s e-methane narrative on a global stage, including a demonstration facility producing e-methane from food waste and captured CO2. The company has also signed a long-term LNG supply agreement with ADNOC, reinforcing the other side of its strategy: keep energy stable and affordable while the transition plays out. Meanwhile, the “mature phase” of deregulation means competition is no longer theoretical. Osaka Gas has to win customers, not inherit them.

For anyone watching the business, two signposts loom over the rest of this story: how well Osaka Gas can sustain its LNG handling business even as domestic demand softens, and how quickly e-methane moves from Expo demo to real molecules in the gas grid—with a goal of getting to meaningful injection by 2030, even if only at the first, symbolic scale.

II. The Founding Story: Fire, Edison, and Osaka's Merchant Spirit (1871–1905)

Osaka’s gas story begins in 1871, when Japan’s first gas-powered lamp was switched on to light the city mint. The country had only recently been forced open to the outside world by the arrival of the United States Navy under Admiral Perry. Japan was abruptly confronting a new reality: modernize fast, or be modernized by someone else.

The timing couldn’t have been more consequential. The Meiji Restoration had only just begun. After centuries of isolation, Japan was racing to import technology, build industry, and prove it could stand as a peer to the Western powers. In that context, gas lighting wasn’t just a nicer way to see at night. It was a public symbol of national urgency and industrial ambition.

But early on, gas didn’t have the field to itself. Kerosene lamps also arrived from the West, and for a while they won on convenience. Then reality intervened. In cities built largely of wood and paper, kerosene’s downside showed up the hard way: fires. Lots of them. Safety became the deciding factor, and authorities increasingly saw gas as the better answer for urban lighting.

It’s an early glimpse of a pattern that will keep showing up in Osaka Gas’s history: disruption and crisis don’t just threaten the business. They can widen the lane for it.

Osaka Gas was formed in 1897, backed by municipal capital and overseas investors. And here’s where the origin story turns unexpectedly global. Its foreign patron was the Edison Power Company in the United States. An Osaka businessman, Taro Asano, met Edison’s president, Anthony Brady, in New York. The relationship stuck. Brady was impressed enough to send an Edison representative, Alexander Chizon, to Osaka to help arrange financing and provide technical support.

By 1902, Edison had become a major shareholder—holding 50% of Osaka Gas, a stake it later sold to Japanese investors. That level of foreign ownership, at that moment in history, was extraordinary. And it says something important about Osaka. This wasn’t the political capital’s world of ministries and hierarchy. This was Japan’s merchant city: practical, deal-oriented, and willing to take outside capital if it accelerated progress.

Masagi Kataoka was chosen as the company’s first president. His mandate was straightforward and enormous: build the system. In the 19th century, “city gas” meant coal gas. Natural gas extraction and transport weren’t yet on the table. So Osaka Gas built a factory in the Iwazaki area equipped with eight gas-producing retorts imported from the United States. Using coal as feedstock, the plant could produce about 4,000 cubic meters of gas per day.

Then came the hard part: distribution. Underground piping had to be laid across the city. In just two years, from 1902 to 1904, workers—using manual labor and animal power—installed roughly 80 kilometers of pipe.

That’s the foundational image of Osaka Gas: not a flashy invention, but a gritty, physical build-out. Street by street, it created the kind of infrastructure that—once buried—becomes incredibly hard for anyone else to duplicate. That “moat” would protect Osaka Gas for decades, until deregulation and decarbonization found ways to go around it.

Osaka Gas began operations in Nishi-ku, Osaka, on a site now occupied by the Dome City Gas Building near the Kyocera Dome. From there, it expanded outward, reaching Wakayama in 1911.

And all of it was shaped by the company’s hometown. Tokyo was the political center, defined by government and bureaucracy. Osaka was commercial—fast, pragmatic, and proud of its trading culture. That merchant DNA didn’t just influence the early financing story. It would later show up in how Osaka Gas diversified, how it went overseas, and how it fought to stay relevant once the rules of the game stopped guaranteeing it customers.

III. Building the Infrastructure: Coal Gas to Natural Gas (1905–1970s)

In the early 1900s, Japan was moving fast. Victories in the Sino-Japanese War and the Russo-Japanese War announced the country as an emerging power, and the next two decades brought intense industrial growth—and intense inflation to match.

But gas prices didn’t move like everything else. Between 1905 and 1925, the price of gas rose only about 50 percent, even as staples like coal and rice soared far more. That gap wasn’t an accident. It was the early shape of Japan’s utility bargain: gas companies were treated as essential infrastructure, expected to keep prices stable, and in return they operated under heavy regulation and enjoyed protected territory.

Osaka Gas was already scaling into that role. In 1905, it supplied gas to about 3,350 homes. By 1933, it served 300,000 households. In less than thirty years, gas went from a novelty for lighting to a mainstream household service, pulled along by urbanization and by gas steadily finding new jobs—cooking, heating, hot water—inside everyday life.

Then came the shock of World War I and the depression that followed. Here, Osaka Gas did something that looks almost backwards on paper. Management under Kataoka leaned into a strategy of lowering gas prices over the long run. The logic was simple: if customers were being squeezed, don’t give them a reason to quit. Make gas feel less like a luxury and more like a utility you can’t live without. It also helped that alternatives like firewood were becoming scarcer and more expensive. Keeping gas affordable didn’t just retain customers; it expanded the market.

World War II, though, forced the industry into a different kind of logic: consolidation. In October 1945, right after the war ended, Osaka Gas merged with 14 other gas companies across Kansai. Part of it was wartime industrial policy lingering into the aftermath—coordination, standardization, and control. Fifteen separate operators in overlapping areas simply didn’t fit the moment.

But the postwar occupation reversed that direction. In 1949, under the Allies’ Law for the Elimination of Excessive Concentration of Economic Power, the merged group was broken apart. Osaka Gas became a standalone company again. That same year, Kataoka—who had led the business since its earliest days—died, closing the chapter on more than half a century of continuity. His successor was Jiro Iiguchi, a former vice-president.

The 1950s became a stress test of a different kind: rebuilding. As Japan entered its reconstruction surge from 1950 to 1955, Osaka Gas began a full-scale restoration of its Yujima facility, using manual labor when necessary. By 1952, production had returned to prewar levels. That year, the company also opened a gas appliance research center—because in utilities, demand isn’t just pipes and molecules. It’s what customers can actually do with the fuel once it arrives.

In 1953, Yujima produced its first oil-based gas. German high-pressure storage and transport technology was added, another example of Osaka Gas looking outward for technical advantage, just as it had in the Edison era.

And by the 1970s, an even bigger shift was approaching—one that would change not just Osaka Gas, but Japan’s energy posture itself. The company was about to move from manufactured gas to natural gas, and specifically to LNG shipped from overseas. The infrastructure mindset stayed the same. The feedstock—and the geopolitical stakes—were about to become something entirely new.

IV. The LNG Revolution: Japan's Energy Security Imperative (1970s–1990s)

The 1973 Arab oil embargo landed in Japan like a cold splash of water. The country imported virtually all of its oil, much of it from the Middle East. When supply tightened, the vulnerability stopped being an abstract policy concern and became daily life: rationing, disruption, and a recession that made the dependency impossible to ignore.

From that point on, Japan’s energy playbook had a new first principle: diversify, or risk being held hostage.

Liquefied natural gas fit the bill. By chilling natural gas to around -162°C, it could be shipped long distances in specialized tankers, opening the door to supply from places like Indonesia, Malaysia, Brunei, Australia, and eventually the Middle East. Compared to oil, LNG offered something Japan desperately wanted: optionality.

Osaka Gas moved early. It began importing LNG from Brunei in 1972, then added Indonesia in 1977. And in 1979, it did something that captured the company’s mindset in a single stroke: it put the world’s first cryogenic power plant into operation.

The idea was almost offensively practical. When LNG is warmed back into gas at a terminal, all that cold gets thrown away unless you use it. A cryogenic power plant captures that temperature difference and turns it into electricity—literally making power from what used to be waste.

And Osaka Gas didn’t stop there. At the time, it was importing roughly three million tons of LNG—about a tenth of Japan’s total—and its engineers started treating the LNG “cold chain” like a platform. Working with the food industry, the company helped form Kinki Cryogenics, supplying frozen foods by leveraging LNG’s low temperatures. That same subsidiary became the first in the world to use LNG to produce liquid carbon dioxide. None of this looked like a traditional utility business. That was the point. Osaka Gas was learning to squeeze value out of every step of the system, not just the molecules flowing through a pipe.

Over time, the company also pushed upstream. It built positions in oil and gas assets in places like Norway and Australia, including major Australian LNG projects such as Gorgon, Sunrise, and Crux, and it held interests connected to Qalhat LNG in Oman. The strategic benefit was clear: rather than being only a buyer—exposed to supplier pricing power and market tightness—Osaka Gas could secure supply and share in production economics.

On the ground in Japan, the strategy crystallized in steel and concrete at the Senboku LNG terminal in southern Osaka: tankers arriving from across the region, cryogenic tanks holding the fuel, regasification units warming it back into gas, and the distribution network pushing it out to homes and factories across Kansai. This wasn’t just an import facility. It was the anchor point for Osaka Gas’s modern era—built around LNG.

That diversification extended to suppliers, too. Osaka Gas purchased LNG from Brunei, Australia, Indonesia, Malaysia, and others, deliberately avoiding dependence on any single country. And even as Japan initially tried to limit Middle East exposure, long-term relationships formed there as well. ADNOC, for example, became a reliable LNG supplier to Japan for nearly half a century—one of those quiet, durable partnerships that matters most when global LNG suddenly gets scarce.

V. Diversification Era: Beyond Gas (1980s–2000s)

Before Osaka Gas became known for overseas LNG stakes or carbon-neutral ambitions, it lived through a trauma that rewired the company.

On the evening of 8 April 1970, in downtown Osaka at Tenjimbashisuji Rokuchōme Station, a gas leak occurred during construction work. What followed became known as the Tenroku gas explosion—one of the worst gas disasters in Japanese history. The blast and fire killed 79 people, injured 420, and damaged 495 buildings.

The sequence of events reads like a checklist of how quickly a routine incident can turn catastrophic. The fire department and police responded first, cordoning off the area and evacuating people while waiting for the repair team. When the maintenance crew arrived in two service vehicles, one vehicle parked on top of a cover plate and its engine was turned off—possibly after stalling. At 5:39 pm, as the team assessed the leak, the driver restarted the engine. Gas had been seeping up through cracks in the cover plates, and the restart produced a spark that ignited it, setting the vehicle on fire.

Eight minutes later, at 5:47 pm, the main explosion erupted from the subway tunnel. The street above ruptured. Around 30 buildings were completely destroyed. Concrete slabs covering the tunnel were thrown into the air and came down on victims.

For Osaka Gas, the aftermath wasn’t just grief and compensation; it was a turning point in how the entire system would be governed. The Gas Business Act of 1954 was amended to strengthen leak prevention and ensure that safety measures applied not only to gas companies, but also to any entity working around gas infrastructure. And internally, Osaka Gas institutionalized emergency readiness. In 1979, it installed an emergency response command system in command centers at its Kyoto, Osaka, and Kobe branches. Safety, which had always mattered, became something closer to doctrine.

And here’s the pivot: as the core gas business became increasingly regulated and safety-focused, Osaka Gas started looking for other places to apply what it was best at—engineering, process know-how, and the industrial chemistry that sat behind “city gas.”

In the 1980s, that search turned into a deliberate diversification program. It began with something almost hidden in plain sight: coal-related byproducts the company had handled since the beginning, like coke, benzene, and coal-tar products. Then it moved into businesses that looked nothing like a utility. In 1987, Osaka Gas formed a subsidiary, Donac Company, to produce Donacarbo carbon fibers—materials that ended up in products like golf clubs sold around the world. Another subsidiary, Harman Company, developed and manufactured gas-run appliances.

The carbon fiber move captured Osaka Gas’s playbook: take a capability forged inside the core business, then commercialize it in adjacent markets. Expertise in coal chemistry, built for making gas, turned out to be surprisingly useful for advanced materials.

Over time, the company that had once been “just” a distributor of gas for lighting, heating, and power evolved into a broader corporate group. The Osaka Gas Group—Osaka Gas as the nucleus—grew to more than 60 companies spanning engineering services, information processing, and other businesses built around its technical base.

That evolution eventually became legible as a three-part structure: Domestic Energy Business, International Energy Business, and Life & Business Solutions Business. It was an organizational admission of a strategic truth: the comfortable old world of the domestic gas monopoly wasn’t permanent. Osaka Gas needed new engines—before it was forced to find them.

VI. Inflection Point #1: Deregulation Destroys the Moat (1995–2022)

For nearly a century, Osaka Gas lived in a world built for utilities: regulated pricing, exclusive territories, and an implicit deal with the state that if you kept the lights on and the gas flowing, you’d be allowed to earn steady returns.

Then Japan started pulling that world apart.

The push began in the mid-1990s, driven by a straightforward problem: energy in Japan was expensive, and policymakers wanted competition to force costs down. Both electricity and city gas were put on the same path—slow at first, then faster, and eventually unavoidable.

In 1995, Japan liberalized electricity wholesale generation, allowing new, non-utility players to generate power and sell it into the system. City gas followed a similar opening that same year: non-traditional gas suppliers were allowed to sell to the biggest customers—industrial users buying more than 2 million cubic meters a year. The logic was classic deregulation. Start where customers are sophisticated and volumes are large, then work your way down.

That’s exactly what happened. Over the next decade, the thresholds kept dropping. In electricity, the market opened further in 2004 and 2005, when new suppliers were allowed to serve high-voltage customers with large contract sizes, with prices set freely between buyer and seller. City gas expanded, too: in 2004, deregulation broadened to customers using more than 0.5 million cubic meters per year, and in 2007 the bar fell again to 0.1 million cubic meters.

Eventually, the reform reached the moment that mattered most politically—and most viscerally: households.

After full liberalization of retail electricity in April 2016, full liberalization of retail city gas took effect in April 2017. From that point on, consumers could choose their energy provider and shop among competing rate plans. Regional monopolies and regulated pricing for small-scale gas retail were abolished. For Osaka Gas, this wasn’t a tweak. It was the end of “customers by default.”

But Japan didn’t stop at retail choice. The final step was structural: unbundling the pipes.

The long-running system reform culminated in the requirement that the three major city gas incumbents—Tokyo Gas, Osaka Gas, and Toho Gas—separate pipeline operations into new, independent, pipeline-dedicated subsidiaries. That requirement took effect on 1 April 2022. The message was clear: the network is essential infrastructure, and it shouldn’t be bundled with competitive retail in a way that can tilt the playing field.

In theory, this is what finally “destroys the moat.” In practice, it was messier.

Even after liberalization, customer switching moved slowly. As of 31 March in the referenced period, about 4 million accounts had switched—only 16.8% of total city gas users nationwide. Part of the reason was structural. Unlike electricity, city gas didn’t have a wholesale exchange like Jepx where newcomers could buy supply transparently. Instead, new entrants generally had to procure gas directly from existing gas retailers or from city gas producers—companies capable of blending LNG and LPG to meet METI’s standard specifications. There were 26 registered city gas producers, including gas retailers, power utilities, refiners, and LNG importers.

That structure made entry possible, but not necessarily profitable. If you’re a would-be challenger and your biggest input cost is buying gas from someone who already has scale, terminals, and blending capability, it’s hard to undercut them on price.

So yes—Osaka Gas lost the legal protections of monopoly. But it still owned many of the real-world advantages: LNG terminals, blending facilities, operational know-how, and decades of embedded infrastructure. The moat had been opened. It wasn’t gone.

Osaka Gas’s response was to stop thinking like a single-product utility and start thinking like an energy retailer in a converging market. If power companies could enter gas, then Osaka Gas would enter electricity. Deregulation didn’t just create competition. It changed the game into one where the same customer relationship could be fought over from both directions—and Osaka Gas intended to fight back.

VII. Inflection Point #2: Going Global—The International Expansion (2010s–Present)

By the 2010s, the direction of travel inside Japan was obvious. The domestic market was mature. The population was shrinking. And deregulation meant Osaka Gas could no longer count on being the default choice in Kansai.

So it did what a lot of Japan’s best industrial companies do when the home market stops expanding: it went looking for growth abroad. The logic was clean. Osaka Gas had decades of LNG know-how, hard-earned engineering capability from building and operating infrastructure, and the financial strength that came from years of regulated stability. If the old moat was fading at home, those same capabilities could become an advantage overseas.

North America became one of the pillars. Osaka Gas USA Corporation is a wholly owned subsidiary tasked with developing, acquiring, and managing business across the region. Its focus spans four areas: power generation, shale gas development, natural gas liquefaction at Freeport LNG, and future energy development and innovation.

This wasn’t a single-country push, either. Osaka Gas built a global footprint, with offices in Australia, Singapore, Thailand, the United States, and the United Kingdom—an organizational signal that “international” wasn’t a side project anymore. It was becoming a core lane.

But the most ambitious swing was India.

Osaka Gas designated India as one of its most important target countries for business development, citing the country’s scale and growth potential. On April 8, Osaka Gas announced that its subsidiary OSAKA GAS SINGAPORE PTE. LTD. (OGS) had reached an agreement with Sumitomo Corporation and the Japan Overseas Infrastructure Investment Corporation for Transport & Urban Development (JOIN) to invest in AG&P LNG Marketing Pte. Ltd., aiming to expand city gas distribution (CGD) in India. The investment would be made through a Japanese consortium jointly owned by OGS, Sumitomo, and JOIN. It was OGS’s second major investment in India’s CGD market, following its first in 2021.

The operational plan was sweeping. Since 2021, the business had been developing CGD across twelve geographical areas under the brand name AGP Pratham, mainly in suburbs of southern India. With the new investment, AG&P LNG Marketing would also develop seven additional geographical areas under the THINK Gas brand in urban regions of north and central India.

In total, that’s nineteen geographical areas covering roughly 320,000 square kilometers—about 10% of India’s land area. AG&P LNG Marketing planned to build compressed natural gas (CNG) stations and keep extending distribution networks, targeting growth in transportation, as well as household, commercial, and industrial demand. The stated ambition was striking: to grow gas sales volume in India to more than half of Osaka Gas’s gas sales volume in Japan.

That last point matters. This wasn’t “a foothold.” It was a plan to build an India-scale engine.

Financially, Osaka Gas planned to invest about USD 240 million into the Japanese consortium through OGS. The consortium, jointly owned by Osaka Gas, Sumitomo, and JOIN, planned to invest about USD 370 million into AG&P LNG Marketing.

The timing also matched India’s national posture. In December 2019, the Indian government announced a goal of increasing natural gas’s share in the primary energy mix from 6% in 2019 to 15% by 2030.

And Osaka Gas didn’t stop at gas.

It also moved into Indian renewables. On March 7, the Japan Bank for International Cooperation (JBIC) signed a shareholders’ agreement for a joint investment with Osaka Gas in a portfolio of renewable energy projects implemented by Clean Max Enviro Energy Solutions Private Limited (CleanMax), through Clean Max Osaka Gas Renewable Energy Private Limited (CORE) in India. CleanMax is a leading corporate power purchase agreement provider, supplying electricity from renewable sources including solar, wind, and hybrid power. Under the agreement, JBIC and Osaka Gas would make an equity investment in projects developed and operated by CleanMax based on corporate PPAs, mainly in Karnataka.

Taken together, the strategy is clear: pair city gas distribution with renewables, and you’re not just exporting LNG expertise—you’re building the footprint of an integrated energy provider in one of the world’s fastest-growing energy markets.

VIII. Inflection Point #3: The Carbon Neutral Vision & e-Methane Bet (2021–Present)

In January 2021, Osaka Gas made what may be the most consequential commitment in its history: the Daigas Group would aim to become carbon neutral by 2050.

The vision wasn’t framed as a single moonshot. It was a portfolio strategy. Decarbonize both gas and electricity by introducing methanation—making methane using renewable energy, hydrogen, and captured CO2—while also increasing the share of renewables in its power generation mix. The company put a name on it, too: “Carbon Neutral Vision,” paired with a more detailed set of approaches in its Energy Transition 2030. Since then, Osaka Gas has pushed forward on multiple fronts, from renewable power development to launching e-methane projects and advancing the technologies needed to make them real.

At the center of all of it is e-methane: synthetic methane created by reacting hydrogen with captured carbon dioxide. The reason Osaka Gas likes this molecule is almost disarmingly simple. Customers can use it without changing what they already own. Boilers, burners, water heaters, industrial furnaces—if they run on natural gas, they can run on e-methane, too, with no major modifications.

That compatibility is the strategic punchline. Hydrogen often requires new equipment and new handling. Full electrification can mean expensive retrofits and major grid upgrades. E-methane, by contrast, is designed to flow through the system that already exists. It’s a decarbonization pathway that tries to avoid stranded assets: keep the network, keep the appliances, swap the molecules.

And the ambition is national, not just corporate. The Japanese government and the gas industry have aimed for e-methane to make up 1% of the gas grid by 2030 and 90% by 2050. If that happens, e-methane becomes a core carbon-neutral energy source across households, factories, and commercial buildings.

The argument for why this matters is tied to what’s hardest to decarbonize: heat. E-methane is positioned as a way to meet heat demand—especially high-temperature industrial heat—where electricity can be an awkward substitute.

From there, Osaka Gas’s strategy shifts from molecule theory to supply chain reality. It has been working to build e-methane production and logistics across multiple geographies, including feasibility studies that examine whether e-methane produced in North America could be liquefied using existing LNG infrastructure—specifically, the facilities of Cameron LNG and Freeport LNG.

Two U.S. concepts illustrate the approach. One centers on producing e-methane in the Midwest using biomass-based CO2. Another envisions production in Texas and Louisiana, liquefaction at Cameron LNG, and transport to Japan. That second effort lists a familiar roster of Japanese energy incumbents: Osaka Gas, Tokyo Gas, Toho Gas, and Mitsubishi.

In the Midwest, the company has been exploring a particularly concrete feedstock pairing: ethanol and hydrogen. Green Plains Inc., Tallgrass, and Osaka Gas USA announced the start of a joint feasibility study to evaluate producing up to 200,000 tons per year of synthetic methane. The concept is to use low-carbon hydrogen plus biogenic CO2 captured from ethanol biorefineries owned and operated by Green Plains.

Back in Japan, Osaka Gas has been pursuing scale-up at home, too—alongside INPEX.

INPEX and Osaka Gas announced plans to launch what they described as the world’s largest-scale synthetic methanation plant at Nagaoka by the second half of fiscal year 2024–25. The project is supported by a subsidy from NEDO and centers on a CO2 methanation test facility at INPEX’s Minami Nagaoka gas field, designed to produce 400 normal cubic meters of methane per hour—an output the companies said is equivalent to the amount of methane consumed by about 10,000 households in Japan per day.

The entire point of building at that scale is cost-down. The companies have described this step as a jump from a smaller 8 normal cubic meters per hour plant toward a much larger facility, with the aim of reducing production costs along the way. They’ve also signaled the next gates: decisions around even larger plants—10,000 normal cubic meters per hour and 60,000 normal cubic meters per hour—expected around 2025 and 2030, respectively, with the longer-term goal of getting costs down to levels that could compete with current domestic city gas sales prices.

There’s another piece of the puzzle, too: where the hydrogen comes from.

Osaka Gas has made a strategic investment in Koloma, a U.S.-based startup focused on exploring and developing natural hydrogen—hydrogen that occurs underground and could potentially be extracted using conventional drilling techniques. Koloma raised a $50 million Series B extension round with investors including Osaka Gas and Mitsubishi Heavy Industries.

If natural hydrogen proves scalable, it could be a meaningful lever: a potentially lower-cost source of hydrogen for e-methane production that avoids the expense of producing hydrogen through electrolysis.

And this is what makes Inflection Point #3 feel different from the earlier ones. Deregulation forced Osaka Gas to compete. Global expansion gave it new markets. But the carbon-neutral push asks something deeper: can a gas company design a future where “gas” survives—without fossil carbon—by turning its greatest legacy asset, the network, into the backbone of its transition?

IX. The Daigas Rebrand: Identity Transformation

In 2018, Osaka Gas made a move that was more than cosmetic. It launched a new group brand: the Daigas Group. Internally, the message was straightforward: the company wasn’t just a city-gas utility anymore. It was a corporate group, and it wanted to be judged like one—on the total value it could create for customers, partners, employees, and shareholders.

The name change matters because “Osaka Gas” does two things at once: it pins you to a place, and it pins you to a product. Kansai. Gas. “Daigas” loosens both. It keeps a nod to the company’s roots, but drops the geographic label and gives the organization room to be something bigger: an integrated, globally active energy and solutions group that happens to be headquartered in Osaka.

That rebrand also put a cleaner frame around what had already been happening for years. The Daigas Group is built on capabilities forged through repeated disruptions—safety crises, fuel transitions, deregulation, international expansion—and increasingly applies them beyond traditional utility work.

You can see that identity crystallized in the group’s current planning cadence. Its Medium-Term Management Plan for 2024 through 2026, called CAD2026, lays out the posture Daigas wants to take into the next phase: secure stable energy supply today, while building offerings that match what the market is asking for tomorrow—decarbonization, digitalization, and a wider range of customer values than “lowest price per unit.”

In other words, the Daigas rebrand isn’t a slogan. It’s the company publicly committing to a new job description: not just delivering molecules through pipes, but leading the creation of solutions that keep customers’ lives and businesses running through the energy transition.

X. Recent Deals: 2024-2025 Activity

The past two years put Osaka Gas’s strategy on the scoreboard. Not in a single headline deal, but in a pattern: lock down supply, scale renewables, and keep moving e-methane from concept to concrete.

First up: LNG security.

ADNOC signed a long-term Heads of Agreement with Osaka Gas for up to 0.8 million tonnes per year of LNG, primarily sourced from ADNOC’s lower-carbon Ruwais LNG project in Al Ruwais Industrial City, Abu Dhabi. The project was still under development, with commercial operations expected to begin in 2028.

Then, in February 2025, that relationship clicked into a firmer gear. ADNOC and Osaka Gas signed a 15-year Sales and Purchase Agreement for the same volume from Ruwais—converting the earlier Heads of Agreement into a definitive contract and marking the first long-term LNG sales agreement between ADNOC and Osaka Gas.

The backdrop here matters. ADNOC has been a reliable LNG supplier to Japan for nearly half a century, and Osaka Gas framed this contract as a stability play: more dependable supply for customers during an era when “secure energy” is back at the top of the agenda. ADNOC also positioned Ruwais as a lower-carbon source of LNG—describing it as the first LNG export facility in the Middle East and Africa region to operate on clean power, and among the lowest-carbon intensity LNG plants globally.

At the same time, Osaka Gas kept building out its renewable footprint at home.

RWE Offshore Wind Japan Murakami-Tainai K.K. was selected in a consortium with Mitsui & Co., Ltd. and Osaka Gas to deliver a 684 MW commercial-scale fixed-bottom offshore wind project off Japan’s west coast. The site is off Murakami and Tainai in Niigata Prefecture, and the project is expected to use 38 wind turbines. RWE said full commissioning is scheduled for June 2029.

But the most visible proof point in 2025 wasn’t a contract or a megawatt figure. It was a show.

At Expo 2025 Osaka, Kansai, the company’s methanation showcase became a public demonstration of its core transition narrative. At the Carbon Recycle Factory Osaka Gas Methanation Demonstration Facility, visitors can see methane— the main component of city gas—synthesized using CO2 contained in biogas produced by fermenting food waste collected from the Expo site, combined with hydrogen derived from renewable energy.

Osaka Gas also completed construction of Bakeru LABO, its e-methane production demonstration facility inside the Expo venue’s Carbon Recycling Factory. On March 11, 2025, the facility was certified as a “clean gas production facility” under the Clean Gas Certificate Program. By the end of August, the Gas Pavilion had welcomed around 500,000 visitors, making it one of the expo’s most popular exhibits.

And then came the next step: going from demonstration to industrial-scale export planning.

In December 2025, Osaka Gas announced participation in a major e-methane project in Nebraska: TotalEnergies, TES, Osaka Gas, Toho Gas, and ITOCHU partnering to develop the Live Oak Project for e-NG production. The partners began preparing the Front-End Engineering Design (FEED) phase, targeting about 250 MW of electrolysis and 75 ktpa of methanation. The project is subject to a Final Investment Decision in 2027, with commercial operations scheduled for 2030 and plans to export e-NG to Japan. Osaka Gas and Toho Gas are set to be the primary offtakers.

Zoom out, and the logic snaps into focus: this is the supply chain Osaka Gas wants for e-methane—real production, built at scale, with export routes into Japan—aimed at supporting the industry’s target of injecting 1% carbon-neutral gas into the grid by 2030.

XI. Porter's Five Forces Analysis

Threat of New Entrants: MODERATE-HIGH (post-deregulation)

On paper, deregulation opened the door. In practice, getting into Japan’s city gas business is still a tough way to make money.

New entrants generally have to buy city gas from existing gas retailers or from city gas producers that can blend LNG and LPG to meet METI’s standard specifications. That supply setup creates a basic problem: if your biggest cost is purchasing gas from an incumbent-scale producer, it’s hard to offer customers a meaningfully better price and still earn a return.

So while the legal moat has been drained, the structural one remains. LNG terminals, blending facilities, and distribution networks create scale and cost advantages that are extremely difficult to replicate. And the fact that only 16.8% of customers had switched four years after full liberalization suggests many households didn’t see enough upside to bother.

Still, there’s one entrant class that can’t be ignored: electricity companies. They come with capital, brands, and large existing customer bases—and in a converged market, cross-selling is the new battleground.

Bargaining Power of Suppliers: MODERATE

Osaka Gas purchases LNG from a diversified set of countries including Brunei, Australia, Indonesia, and Malaysia, which reduces dependence on any single supplier.

It also has upstream positions in projects such as Gorgon, giving it partial vertical integration. And the 15-year ADNOC agreement strengthens supply security, though it can reduce flexibility compared to relying more heavily on spot markets.

Bargaining Power of Buyers: INCREASING

In both electricity and gas retail, consumers can now choose their provider among competing plans and pricing structures. That increases buyer power by default.

For industrial customers, leverage is even higher. Volumes are large, contracts are negotiated, and price differences matter. Residential customers are stickier—switching remains relatively low—but the key change is that loyalty is no longer guaranteed by regulation.

Threat of Substitutes: HIGH AND RISING

The main substitute for gas is electricity, especially as renewable generation grows. Heat pumps in particular pose a long-term threat to gas demand in residential heating. Electrification in transport also caps potential growth in CNG vehicles.

This is the context for Osaka Gas’s e-methane push. If the market is moving toward “no fossil carbon,” e-methane is the company’s attempt to keep the value of gas—especially for heat—while changing the emissions profile of the molecule itself.

Industry Rivalry: INTENSIFYING

Rivalry is rising from both directions: traditional competition with Tokyo Gas, and new competition from power companies entering gas retail. As electricity and gas become bundled offerings, companies aren’t fighting on one front anymore—they’re fighting for the entire customer relationship.

Hamilton Helmer's 7 Powers Framework:

Network Effects: Limited. Gas distribution doesn’t compound like a digital network.

Switching Costs: Moderate. Switching providers takes coordination, but the physical infrastructure doesn’t change.

Scale Economies: Strong. Terminals, pipelines, and processing assets favor incumbents.

Counter-Positioning: The e-methane bet is a form of counter-positioning against the “all-electric” future. If it works, gas remains viable as a decarbonized competitor rather than a stranded product.

Cornered Resource: A geographic grip on distribution infrastructure, even if now regulated, plus hard-to-copy engineering expertise in LNG and methanation.

Process Power: Deep operational experience—distribution, safety management, emergency response, and customer service—built over more than a century.

Brand: Strong in Kansai, less so globally.

XII. Investment Considerations: Bull and Bear Cases

The Bull Case

E-methane is Osaka Gas’s “Goldilocks” pathway: a carbon-neutral fuel that can run through the pipes already in the ground and burn in the equipment customers already own. If methanation scales and costs fall to competitive levels, Daigas’s early work—pilots, partnerships, and supply-chain planning—could turn into a real first-mover advantage.

India is the other big upside lever. The bet is that Osaka Gas can transplant what it knows—building distribution networks, growing demand, and operating safely—into a market that’s still expanding. If it works even partway, India could become a major profit center within the next decade.

Meanwhile, the “old” business still matters. Diversified LNG sourcing, upstream investments, and long-term contracts are designed to keep molecules flowing and cash flows steady, even if e-methane takes longer than hoped to materialize.

And then there’s the cultural edge. Osaka Gas has a track record of finding value in adjacent opportunities—turning LNG cold into frozen-food logistics, coal chemistry into carbon fiber, and utility know-how into offshore wind participation. That engineering-and-operators mindset can create options the market isn’t pricing in yet.

The Bear Case

E-methane is still, by any honest definition, early. Even supporters acknowledge that the industry remains in the demonstration and pilot phases. And there’s a broader climate-timeline critique hanging over the entire concept: if the world needs rapid decarbonization, waiting for a new synthetic fuel to scale could be a costly delay.

There’s also an efficiency argument. Critics point out that making e-methane means taking electricity, turning it into hydrogen, then turning that hydrogen into methane—losing energy at each conversion step. Where direct electrification is feasible, it’s usually the more efficient route.

On the business side, Japan’s shrinking population puts structural pressure on long-term domestic demand, regardless of how competition plays out. That makes international expansion less optional—but expansion comes with execution risk, especially in a complex market like India.

Finally, the rules aren’t done changing. Pipeline separation is already reality, but policies like carbon pricing and other regulatory shifts could meaningfully reshape economics—either strengthening Osaka Gas’s position or compressing returns.

Key Metrics to Track:

-

LNG Handling Volume: Management has aimed to maintain around 11.5 million tons through 2030, even as domestic demand declines. The tell will be whether international trading and wholesale growth can offset softness in retail.

-

E-methane Grid Injection Percentage: The industry target is 1% by 2030. Hitting credible milestones toward that goal is the clearest signal that the e-methane strategy is moving from Expo narrative to real supply.

XIII. Conclusion: A 127-Year Bet on Molecular Energy

Osaka Gas traces its roots back to 1897, in Japan’s merchant city of Osaka—an energetic, deal-driven place where new ideas didn’t just get discussed, they got built. The first headquarters went up there, and with it came a company DNA that’s stayed surprisingly consistent: practical engineering, a willingness to borrow the best technology available, and an instinct to keep moving before circumstances force the move.

Look at the arc. It starts with Edison-backed gas lamps. It runs through coal gas retorts and the gritty work of laying pipe street by street. It pivots to LNG when Japan’s energy security becomes a national obsession. It survives deregulation by learning how to compete. It goes abroad when the home market stops growing. And now it’s pushing into the weird frontier of carbon-neutral molecules—methanation at industrial scale and even a venture-style bet on natural hydrogen exploration.

Through all of that reinvention, Osaka Gas has kept coming back to a single thesis: molecules matter. Heat still needs fuel. Many industrial processes still demand high temperatures that are difficult to replace with electricity alone. And modern cities still need energy systems that don’t blink when the weather turns, supply chains break, or geopolitics spikes the price of the marginal molecule.

That’s what makes e-methane so central. It isn’t just a decarbonization project; it’s an attempt to preserve the value of the gas system by changing what flows through it. Instead of conceding the transition entirely to electrons, Osaka Gas is arguing for a world where carbon-neutral molecules remain a first-class citizen—because the infrastructure is already there, and because the use cases for combustion aren’t disappearing overnight.

Whether that turns out to be the most pragmatic bridge to 2050, or an expensive detour around electrification, will shape the company’s next quarter-century.

For investors, the Daigas Group is a rare kind of utility story: not a finished machine, but a managed transformation. A century of regulated stability built deep infrastructure advantages—advantages now tested by competition. A shrinking domestic base pushes capital outward. Fossil LNG cash flows have to coexist with synthetic alternatives that are still climbing the cost curve. The outcome is genuinely uncertain, which is exactly why it’s interesting.

The gaslight that illuminated Osaka’s mint in 1871 has, in a straight line of technological ambition, given way to methane synthesized from food waste and captured CO2 at Expo 2025. The source has changed. The wager hasn’t: that the future of energy won’t be only electrons—and that, even in a carbon-neutral world, the right molecules will still run the city.

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music