Tokyo Gas: Japan's Energy Infrastructure Giant and the Battle for Shareholder Value

I. Introduction: A 140-Year-Old Monopoly Meets Wall Street

Picture the scene: November 19, 2024. Trading desks across Tokyo suddenly snap to attention as Tokyo Gas shares jump more than 12% in a single session—the biggest intraday move since 1987. Not because of a new LNG contract. Not because of a breakthrough project. The spark is a plain-looking regulatory filing: Elliott Investment Management has quietly built a roughly 5% stake in Japan’s largest gas utility.

Elliott’s disclosure—5.03%—instantly puts Tokyo Gas on the same list as a growing number of Japanese blue chips being pressed by activists to “unlock value.” In other words: sell things, simplify, raise returns, and stop treating shareholders like an afterthought.

And it raises a deliciously odd question: how does a 140-year-old company that started with gas lamps end up looking, to an American hedge fund, like a $9 billion real estate story hiding inside an energy utility?

Tokyo Gas is enormous in the ways that matter. As of March 2025, it served about 8.8 million city gas customers and 4.2 million electricity customers—roughly 13 million customer accounts—largely across greater Tokyo. It distributes gas throughout the Kanto region, Japan’s largest economic engine, responsible for around 40% of the country’s GDP. This isn’t a sleepy local utility. It’s critical infrastructure for the nation’s economic core.

It’s also a modern public company: listed on the Tokyo Stock Exchange since May 1949 under stock code 9531, and operating today as a multinational focused on natural gas, LNG, electricity, and “sustainable energy solutions.” In fiscal year 2024, net sales were JPY 2,636.8 billion, with trailing twelve-month revenue of about USD 17.3 billion. By December 2025, its market cap sat around $13.79 billion.

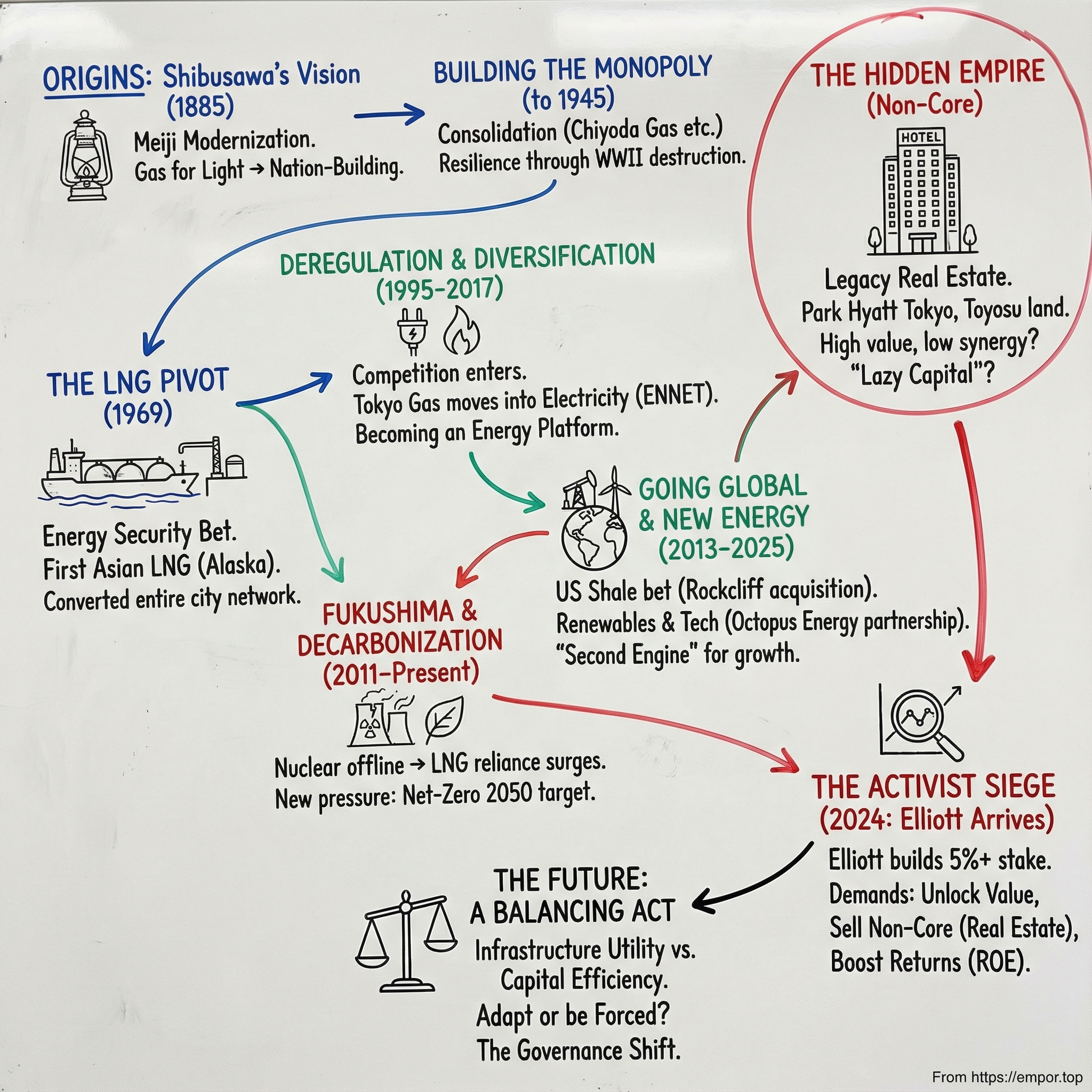

But numbers don’t capture why this story has everyone leaning in. Tokyo Gas’s arc runs through three centuries of Japanese history: from the Meiji era’s obsession with modernization, to LNG supertankers bridging Japan’s resource gap, to wartime devastation, to the post-Fukushima reshuffling of the entire energy system—and now, a boardroom confrontation with one of Wall Street’s most relentless activists.

Along the way, Tokyo Gas built something that doesn’t fit the stereotype of a utility at all: a sizable urban development and real estate portfolio that includes the Park Hyatt Tokyo—the Shinjuku landmark made famous by “Lost in Translation.”

So why does a gas company own one of Tokyo’s most iconic luxury hotels? What is Elliott seeing in those “non-core” assets that management and the market have supposedly missed? And what does this fight reveal about a corporate governance shift that’s sweeping through Japan Inc.?

To answer that, we have to go back to the beginning—before LNG, before deregulation, before activists—when lighting a city was the cutting edge of national power.

II. Founder's Vision: Shibusawa Eiichi and the Birth of Modern Japan

Before Tokyo Gas, there was darkness—literally. In the 1870s, Japan was sprinting through the Meiji Restoration, trying to modernize fast enough to stand shoulder-to-shoulder with Western powers. And nothing said “we’ve arrived” like gaslight.

City gas made its Japanese debut in 1871, when a gas-powered street lamp lit up Osaka. Tokyo followed three years later: 85 gas lamps appeared near the Diet building, bathing the nation’s political center in a new kind of light powered by imported technology and new industrial know-how.

Into this moment stepped Shibusawa Eiichi, a figure so central to modern Japanese capitalism that his face now appears on the 10,000-yen note. Born in 1840, Shibusawa became known as the “Father of Japanese capitalism” for helping transplant Western-style finance and corporate organization into a country that was rebuilding itself from the ground up.

He pushed reforms that sound mundane until you realize how revolutionary they were at the time: double-entry bookkeeping, modern banking, joint-stock companies. He helped establish Japan’s first modern bank built around joint-stock ownership. And he wasn’t a one-company founder. The list of institutions he touched—founding, backing, or guiding—runs into the hundreds, and includes names that still define Japan’s economy: the Tokyo Stock Exchange, Tokio Marine, the Imperial Hotel, major banks and railways, and, yes, Tokyo Gas.

What made Shibusawa’s path even more unusual was how it began. He wasn’t born a tycoon; he emerged from the world of samurai-era government service. In 1867, he traveled to Europe as part of the delegation to the Paris International Exposition with Akitake Tokugawa. There, he encountered European industry up close—its systems, its scale, and its infrastructure. It’s easy to imagine the impression: a young Japanese official walking streets lit by gas lamps, watching a city function after dark as if daylight never ended.

When he returned home and resigned from government service in 1873, he carried a clear thesis: Japan would industrialize not through permanent state monopolies, but through private enterprise organized as joint-stock companies.

That thesis became concrete on October 1, 1885. Shibusawa and Asano Sōichirō founded Tokyo Gas by acquiring the business of the Tokyo Prefecture Gas Bureau. The move shifted gas supply from government hands into a private company—perfectly aligned with the Meiji state’s broader push to modernize infrastructure while building a new capitalist system.

Shibusawa became the first president, and he held the role for 35 years. For him, city gas wasn’t just a product; it was nation-building.

At the start, the operation was modest: 343 customers, 61 employees. The company’s early mission was simple and urgent—keep the lamps lit, reliably, for public streets and for a growing city learning to live and work after sunset. But the execution was hard. Tokyo Gas had to import manufacturing techniques and equipment from the West, then make them work under local conditions with limited domestic expertise. This was infrastructure before the playbook existed.

Still, it scaled. In 1890, Tokyo Gas introduced gas meters, enabling accurate measurement and fair billing—small detail, big unlock. Three years later, in 1893, the company adopted the name Tokyo Gas Co., Ltd. following the enactment of the Commercial Code, a sign that Japan’s corporate framework was maturing alongside its industrial base.

And Shibusawa himself remained a study in contrasts. Despite being involved with hundreds of companies, he refused to build a family-controlled conglomerate. He deliberately avoided maintaining controlling stakes, preventing himself from forming a zaibatsu at a time when others were consolidating industrial empires. His goal was to expand Japan’s productive capacity, not to amass personal control.

He also insisted that ethics and business belonged together. In his famous work, The Analects and the Abacus, he argued that Confucian morality and commercial success weren’t enemies—they were meant to reinforce each other.

That idea would become part of Tokyo Gas’s DNA: long-term stewardship, public responsibility, and stability. But it also planted a tension that would only grow louder over the next century—between stakeholder-minded continuity and the modern demand for hard-edged shareholder returns.

The foundation was laid. But turning a gaslight business into a dominant utility would take something Shibusawa understood as well as anyone: patient consolidation, one competitor at a time.

III. Building the Monopoly: From Gas Lamps to Regional Dominance (1885–1945)

By the turn of the twentieth century, Tokyo Gas was no longer a scrappy experiment in modern lighting. It was becoming an industrial machine. By 1908, it was supplying roughly 100,000 homes through about 825 kilometers of pipeline, producing around 1.2 billion cubic feet of gas a year—most of it going straight into kitchens and living rooms.

And as always in infrastructure, success doesn’t stay lonely for long.

That same year, a new rival appeared in Tokyo: Chiyoda Gas. The market was growing fast, the economics looked attractive, and Chiyoda wanted in. What followed was the classic utility nightmare—a price war. Great for customers in the moment, terrible for everyone trying to maintain pipes, plants, and profitability. Management at both companies could see the math wasn’t going to work. In 1911, they signed a pricing agreement just to stop the bleeding.

But the damage was done. Chiyoda was weakened, and Tokyo Gas moved the story to its preferred ending: consolidation.

In 1912, Tokyo Gas merged with Chiyoda Gas, extending its reach beyond central Tokyo and folding in additional production and distribution. A year later, it merged with Kawasaki Gas in 1913, widening its footprint into Yokohama and the growing suburban belt around the capital. Tokyo Gas wasn’t just expanding—it was building a regional system that would be incredibly hard to dislodge.

This cycle—competition, pressure, consolidation—would show up again and again in Tokyo Gas’s history. And by 1944, with Japan mobilizing for total war, Tokyo Gas absorbed the Yokohama City Gas Bureau, effectively locking in its role as the primary gas supplier across the Kanto region.

Then came the part no consolidation strategy can protect you from: war.

In 1945, Tokyo Gas’s infrastructure was nearly destroyed. The same bombings that devastated Tokyo also wiped out gas facilities and crippled the network. In the aftermath, the company entered a strange intermission—run under American occupation authorities while Japan rebuilt itself from the rubble.

By 1949, gas rationing finally ended, and Tokyo Gas was again free to operate as an independent company. The following years were defined by reconstruction: restoring supply, rebuilding pipelines, and reestablishing the basic reliability a city depends on.

But even as it rebuilt, management could see another problem coming. The coal-gas era—dirty, inefficient, increasingly uneconomic—wasn’t going to last forever. Tokyo Gas needed a new feedstock, a new technological foundation, and a new long-term bet.

The answer would arrive two decades later from across the Pacific. In 1969, Tokyo Gas began procuring liquefied natural gas, starting with Alaska—and in doing so, it set up the next great transformation in both the company’s history and Japan’s energy system.

IV. The LNG Revolution: Japan's Energy Security Bet (1969–1988)

Japan’s postwar economic miracle came with a dangerous dependency: the island nation had virtually no domestic oil, gas, or coal. By 1970, Tokyo Gas and the Japanese government were looking for ways to cut Japan’s reliance on Middle Eastern oil, which had grown to nearly 70% of the country’s energy needs. This wasn’t just a cost problem. It was a national vulnerability. If supply routes were disrupted, Japan’s factories, homes, and cities could seize up.

Tokyo Gas’s answer was bold for the era: liquefied natural gas—LNG. The physics were straightforward and the infrastructure was not. You cool natural gas to about -162°C, shrink it to roughly 1/600th of its volume, load it into specialized cryogenic tankers, and ship it across oceans. In the 1960s, that was still closer to science project than standard operating procedure. The bet was whether it could work reliably, economically, and at national scale.

Tokyo Gas’s LNG story begins with Alaska. On March 6, 1967, Tokyo Electric Power (75%) and Tokyo Gas (25%), with Mitsubishi acting as the buyer’s agent, signed what is described as the first Asian LNG sales and purchase agreement. The suppliers were Phillips and Marathon Oil in Alaska. Two years later, in November 1969, the first cargo arrived—marking the first time the United States had exported LNG.

That first shipment came aboard a ship with an appropriately polar name: Polar Alaska. It docked at Negishi in Yokohama, where Tokyo Gas had built an LNG receiving terminal. Soon after, the company expanded capacity across Tokyo Bay: the Sodegaura works began operating as an LNG terminal four years later.

It’s hard to overstate how unfamiliar this was in Japan at the time. LNG terminals weren’t just another plant—you were handling supercooled liquid, storing it safely, regasifying it, and then pushing it into an urban network built for a different kind of gas. Even the chemistry of the product created downstream problems. Natural gas had a lower energy value than the manufactured gas Tokyo customers were used to, so Tokyo Gas had to convert and inspect its network and customers’ appliances to ensure everything could run safely on the new fuel.

And they didn’t convert a neighborhood. They converted a city.

Over roughly two decades, Tokyo Gas systematically transitioned its entire system. By 1988, conversion to a 100 percent natural gas supply was complete—an infrastructure and logistics accomplishment that meant touching essentially everything: pipelines, pressure regulation, safety systems, and millions of end-user appliances.

The strategic logic aged well. Tokyo Gas went on to build a diversified LNG sourcing portfolio, importing from Alaska, Australia, Brunei, Indonesia, Malaysia, and Qatar. It received those volumes at three major terminals—Negishi, Sodegaura, and Ohgishima—giving Japan’s biggest gas utility both scale and optionality. When the 1973 oil crisis rippled through global energy markets, Japan’s growing LNG capability wasn’t a luxury; it was a stabilizer.

In Tokyo Gas’s own long arc, 1969 sits alongside its founding as an inflection point. LNG was new to Japan, but it was a practical way to meet surging postwar demand. It was also cleaner and more efficient than the coal-based gas it replaced, and later came to be seen as more environmentally friendly than other fossil fuels.

Just as importantly, LNG created a moat. LNG infrastructure demands massive capital, long regulatory timelines, and operating know-how you don’t learn from a textbook. Once Tokyo Gas had terminals, ships, and a converted city network, a would-be challenger couldn’t simply “compete harder.” The barriers were physical.

Tokyo Gas even operates its own LNG shipping capacity, owning and operating 10 LNG carriers. And decades later, as the company expanded upstream through moves like the Rockcliff acquisition, the logic of LNG would start to look like something bigger than import security—more like vertical integration. Depending on its agreement with Mitsubishi, that Rockcliff deal could enable Tokyo Gas to source feedgas from the wellhead to produce LNG at the Cameron facility.

But in this era, the core achievement was simpler—and enormous: Tokyo Gas helped turn LNG from a risky experiment into foundational national infrastructure. It wasn’t just a new fuel. It was a new operating system for Japan’s energy economy—one that would prove surprisingly resilient when the next wave hit: deregulation, and real competition.

V. Deregulation Strikes: From Protected Monopoly to Competitive Markets (1995–2017)

For nearly a century, Tokyo Gas operated inside a regulatory cocoon. Regional monopolies owned their territories. Prices were set by formula. Competition wasn’t just unlikely—it was structurally discouraged. It was stable and predictable. And as Japan slid into the stagnation of the “Lost Decade,” it started to look less like stability and more like inertia.

Beginning in the mid-1990s, Japan started prying open that system—slowly, carefully, and in stages—across both electricity and city gas. This wasn’t a single Big Bang deregulation. It was a sequence of rule changes that, year by year, made the old model harder to defend.

For city gas, an early crack appeared in 1995, when non-incumbent gas companies were allowed to supply the biggest customers—those buying more than 2 million cubic meters per year. That meant large industrial users could finally shop around. The local monopoly remained intact for households and small businesses, but the most lucrative, high-volume demand was no longer automatically “yours.”

Electricity followed a similar path. Starting in 1995, Japan partially liberalized the power sector, allowing independent power producers to sell electricity to the regional utilities. Then, in March 2000, those producers were allowed to market directly to customers, opening the door to both domestic and foreign competition in retail power.

For Tokyo Gas, deregulation cut both ways. On one hand, it threatened the comfortable logic of a protected utility. On the other, it loosened the old constraints on what a gas company was even allowed to do with its profits. The company could now think in terms of expansion and diversification—not simply lowering regulated gas rates.

So Tokyo Gas did the obvious thing an incumbent does when the walls start coming down: it refused to stay in one lane.

In 2001, it entered electricity retailing by partnering with NTT Facilities and Osaka Gas to launch ENNET Corporation. To supply ENNET, Tokyo Gas created a subsidiary—Tokyo Gas Bay Power—to build a power plant and generate electricity for sale. The message was clear: if electric utilities were going to come after gas customers, Tokyo Gas would go after theirs.

This wasn’t just a side hustle. It was a strategic pivot—from a gas utility into an integrated energy company, with real generation capacity and a plan to compete as markets opened further.

The watershed arrived in 2016 and 2017. After years of phased reforms, Japan fully liberalized retail electricity in April 2016, then fully liberalized retail city gas in April 2017. From that point on, in both markets, consumers could choose their energy provider based on price and product. The pipeline network remained the shared backbone used by all retail operators—but the customer relationship was now up for grabs.

Overnight, the old rivals became direct competitors. Tokyo Electric Power (TEPCO) could sell gas on Tokyo Gas’s home turf. Tokyo Gas could sell electricity in TEPCO’s. And the first response looked like what you’d expect in a newly competitive commodity market: land grabs and consolidation. In May 2016, Tokyo Gas merged with Chiba Gas, Tsukuba Gakuen Gas Corporation, and Miho Gas, tightening its regional position just as switching became possible.

But here’s the twist: the old order proved surprisingly durable.

As of March 31 in the relevant reporting year, about 4 million customer accounts nationwide had switched from traditional city gas retailers to new entrants—just 16.8% of total city gas users, according to Japan’s trade and industry ministry METI. The market had opened, but customer behavior—and the practical advantages of incumbency—changed more slowly.

And structurally, the incumbents still had gravity. While roughly 200 city gas companies exist across Japan, three giants—Tokyo Gas, Osaka Gas, and Toho Gas—account for about 80% of total gas sales volume. The infrastructure moat remained real. Unlike the U.S. or much of Europe, Japan doesn’t have a single nationwide pipeline network; each city gas company operates the pipes in its own service area. You can compete on retail, but you can’t easily replicate the system underneath it.

Tokyo Gas came out of deregulation not as a fallen monopoly, but as a more complete energy player: selling gas, selling electricity, consolidating its base, and defending its core franchise. And that broader footprint—gas plus power, infrastructure plus customer relationships—would matter a lot when the next disruption arrived from outside the rulebook entirely.

VI. Fukushima's Shadow: How a Nuclear Disaster Reshaped Tokyo Gas's Future (2011–Present)

At 2:46 PM on March 11, 2011, a magnitude 9.0 earthquake hit off Japan’s northeastern coast. The tsunami that followed overwhelmed the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear power plant, setting off the worst nuclear disaster since Chernobyl. As the world watched hydrogen explosions rip through reactor buildings, Japan’s energy system was being rewritten in real time.

In the months that followed, Japan moved to suspend operations across its nuclear fleet. By 2013, all of the country’s remaining 48 reactors had been taken offline, and the nation leaned heavily on imported fuels—especially natural gas—to replace the missing generation.

The knock-on effects were immediate. From 1987 through 2011, nuclear power had provided about 30% of Japan’s electricity on average. With nuclear gone, fossil-fueled generation surged and, in 2012, rose to about 90% of total electricity output.

That meant LNG—already central to Tokyo Gas’s identity—suddenly became a national lifeline. Natural gas consumption for power generation jumped 15% in 2012 versus 2011. Japan’s LNG use set a record in January 2012, nearing 9 billion cubic feet per day—roughly 2 billion cubic feet per day higher than early 2011 levels.

Tokyo Gas found itself essential in a way that would have sounded implausible just a year earlier. Even before the disaster, Japan was already the world’s largest LNG importer, bringing in 69.2 million tonnes a year—about one-third of global LNG supply. After Fukushima, that dependence intensified.

The generation mix tells the story. In 2010, nuclear power plants produced 25.3% of Japan’s electricity. By 2014, that share had fallen to zero. Over the same period, the share produced by gas-fired combined heat and power plants rose from 28.2% to 42.4%. LNG imports increased as well, up 26% during those years.

The bill was enormous. In April 2013, the Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry said Japanese power companies had spent an additional ¥9.2 trillion (about $93 billion) on imported fossil fuels since the Fukushima accident. By the end of 2013, Keidanren warned that keeping nuclear plants shut meant about ¥3.6 trillion (about $34.9 billion) per year in national wealth was flowing overseas through higher fuel imports.

And this is the structural trap Japan fell into: it has limited domestic fossil-fuel resources and imports virtually everything it burns. That’s why it sits as the world’s second-largest LNG importer after China, and the third-largest importer of coal. Fukushima didn’t create Japan’s energy insecurity—but it made it impossible to ignore.

For Tokyo Gas, this era brought both opportunity and responsibility. Its LNG terminals and its growing electricity business made it critical to keeping homes heated and the grid supplied. But it also put a spotlight on the vulnerability baked into the model: an advanced economy running on fuels priced in global markets, exposed to volatility and geopolitics.

Then came the next shift, layered on top of the last one: decarbonization. With climate change accelerating, Tokyo Gas declared in 2019 that it aimed to reach net-zero CO2 emissions by 2050. In 2024, it followed with a detailed roadmap toward that goal.

The company’s challenge became a three-way balancing act: keep energy reliable, drive emissions down, and manage the economic burden of imported fuels. Tokyo Gas’s response was to run multiple tracks at once—expanding renewable energy investments, exploring hydrogen technology, and building out overseas gas production to reduce supply risk.

Meanwhile, Japan’s national policy began to tilt—carefully—back toward nuclear. Under Japan’s sixth long-term energy plan, last updated in October 2021, the government called for nuclear to provide 20%–22% of electricity generation by 2030. A draft of the seventh plan, released December 17, 2024, pointed to nuclear accounting for 20% of energy supply in 2040. The policy intent is to maximize existing reactors: restart as many as possible, and extend licensed operating lives beyond the current 60-year limit.

As reactors have restarted, LNG demand has started to ease at the margin. After five reactors came back online in 2018, Japan’s LNG imports fell 7% in 2019, and dropped another 7% between 2019 and 2022.

Which creates the strategic dilemma at the heart of Tokyo Gas’s modern story: it invested heavily in LNG infrastructure when Japan needed it most—but if nuclear returns meaningfully, some of that demand may prove temporary. If the home market won’t absorb all that capability forever, the obvious place to look is beyond Japan’s shores.

VII. Going Global: The U.S. Shale Bet and Overseas Expansion (2013–2025)

The math was starting to look uncomfortable. Japan’s population was shrinking. Efficiency kept improving. And every nuclear restart threatened to shave demand off the top. Tokyo Gas could defend its home franchise, but it couldn’t count on Japan alone to deliver the kind of growth a modern public company is expected to produce. If the domestic pie wasn’t going to expand, Tokyo Gas needed a second engine—outside Japan.

Then the American shale boom handed them one.

In the 2010s, hydraulic fracturing and horizontal drilling unleashed an ocean of cheap natural gas in Texas and Louisiana. Prices collapsed. Production surged. And the U.S. suddenly had the opposite problem Japan always had: too much gas, not enough outlets. For Tokyo Gas—accustomed to importing LNG at premium prices—the strategic question almost asked itself: why stay a buyer forever, when you could own the molecules?

Tokyo Gas started building its U.S. foothold through Tokyo Gas America. In May 2017, it invested in Castleton Resources LLC, a predecessor to what would become its U.S. upstream arm, TGNR. By August 2020, it had made Castleton a subsidiary. This wasn’t a financial punt. It was a beachhead in the Haynesville shale, the prolific gas basin stretching across East Texas and northern Louisiana—close to Gulf Coast LNG export infrastructure and priced off the most important gas benchmark in the world.

The move that changed the scale of the bet came in December 2023. Tokyo Gas announced that Tokyo Gas America would acquire Rockcliff Energy II LLC for about $2.7 billion.

Rockcliff was one of the standout operators in East Texas Haynesville: headquartered in Longview, with a footprint spanning five Texas counties, more than 200,000 net acres, and more than 1.3 Bcf/d of gross operated natural gas production. With Rockcliff folded in, Tokyo Gas’ output in the region jumped dramatically—roughly quadrupling from its prior level of about 330 MMcf/d. The combined TGNR position expanded to about 594.6 square miles, an area described as roughly 70% the size of Tokyo itself.

Scale wasn’t the only point. Control was.

By owning upstream production, Tokyo Gas wasn’t just chasing profits from U.S. gas—it was trying to reshape the risk profile of its entire fuel supply chain. The Rockcliff acquisition gave Tokyo Gas a larger upstream stake connected to the value chain behind its LNG imports from Cameron LNG. That creates a natural hedge: when U.S. gas prices rise and LNG gets more expensive, upstream revenues can help offset the pain. When prices fall, Tokyo Gas benefits as an LNG buyer. In a world of volatile commodity markets, that kind of portfolio balance is a strategic asset.

This was also explicitly tied to Tokyo Gas’s long-range plan. Under its Management Vision, Compass 2030, the company set out to triple overseas profits, with around half of future profits targeted to come from international operations by 2030.

And the expansion wasn’t stopping at the wellhead. Tokyo Gas Natural Resources has also been in talks with Woodside Energy about taking a stake in a major Louisiana LNG export project. Woodside, the Australian producer, closed a $1.2 billion acquisition of developer Tellurian Inc. after Tellurian put itself up for sale amid cash strain while trying to build a U.S. Gulf Coast LNG facility. The project has been described as capable of converting U.S. shale gas into up to 27.7 million tons per annum of LNG. Woodside has been talking not just to producers, but also to traditional LNG buyers willing to take equity stakes alongside long-term LNG supply rights—exactly the kind of structure that fits Tokyo Gas’s new playbook.

Crucially, “going global” didn’t mean “going gas-only.”

Tokyo Gas also pushed into renewables outside Japan, including an August 2024 investment: the acquisition of a 21.2% stake in the WindFloat Atlantic offshore wind project in Portugal. It was another signal that the company saw its future not as a single-fuel utility, but as an energy platform spanning molecules and electrons.

But the most distinctive partnership in the portfolio might be in the UK—not in drilling rigs or turbines, but in software.

In December 2020, Octopus Energy Group announced a strategic partnership with Tokyo Gas in a deal that valued Octopus at more than $2 billion. The companies launched the Octopus Energy brand in Japan through TG Octopus Energy, a 30:70 joint venture backed by working capital and growth funding from Tokyo Gas. As part of the agreement, Tokyo Gas also took a 9.7% equity stake for $200 million.

The relationship deepened. In November 2023, Octopus Energy’s generation arm launched its first offshore wind fund with a £190 million (€220 million) cornerstone investment from Tokyo Gas, with plans to invest £3 billion (€3.5 billion) in offshore wind globally by 2030. And in October 2023, Octopus’s Kraken platform signed with Tokyo Gas to support a large-scale digital and operational transformation—initially managing about 3 million electricity customers, with the potential for another 10 million gas accounts to migrate later.

Put it all together and you get a very different picture than the traditional “Japanese gas utility.” Tokyo Gas was becoming a company with upstream production in Texas, LNG-linked optionality on the Gulf Coast, renewable investments in Europe, and a high-profile technology partnership aimed at modernizing how energy is sold and serviced back home.

And yet, even as Tokyo Gas built this outward-facing growth machine, it carried something that looked increasingly out of place inside an energy story: a sprawling urban development and real estate portfolio. It was exactly the kind of asset base that can sit quietly for decades—until an activist investor shows up and asks why it’s there at all.

VIII. The Hidden Empire: Real Estate, Hotels, and Non-Core Assets

How does a gas company come to own one of Tokyo’s most famous luxury hotels?

The answer sits at the intersection of history and geography. To run a city-gas system, you need land—big parcels for plants, storage, and logistics—close to the customers you serve. Over a century, Tokyo Gas accumulated exactly that kind of land in and around Tokyo. And then the city changed around it. What began as industrial necessity slowly turned into some of the most valuable urban real estate in Japan.

Toyosu is a perfect example. Tokyo Gas once operated a plant there. Today, the area includes Tokyo’s main fish market and is now being developed into a zero-carbon town. Another example is far more recognizable to global audiences: Shinjuku Park Tower, the landmark complex that houses the Park Hyatt Tokyo—made famous by the 2003 film “Lost in Translation.” It, too, sits on top of Tokyo Gas history: the building was constructed on the site of a decommissioned gas storage facility.

Shinjuku Park Tower is owned and managed by Tokyo Gas Urban Development, a Tokyo Gas subsidiary. And the connection isn’t just historical trivia. Tokyo Gas still operates a regional cooling center on-site, providing heating and cooling to the Nishi-Shinjuku high-rise district, and it supplies electricity to the adjacent Tokyo Metropolitan Government Building.

As a building, Shinjuku Park Tower is a statement. It’s the second-tallest building in Shinjuku, designed by Kenzo Tange and completed in 1994. Structurally, it’s one complex composed of three connected block-shaped elements, anchored by the 235-meter S Tower. The lower floors hold retail, the middle is office space, and the top levels are the Park Hyatt Tokyo—complete with a swimming pool overlooking the city.

In Japan, Tokyo Gas isn’t even unusual for owning a lot of urban property. Utilities ended up with major real estate footprints because they needed infrastructure close to dense population centers. Peers like Osaka Gas and Kansai Electric Power have substantial portfolios too. The difference is that Tokyo Gas is the giant—especially in Tokyo—and its holdings sit in some of the most prime locations in the country. In a world where investors are increasingly focused on capital efficiency, that makes it an obvious target.

The scale is what turns this from “nice side business” into “hidden empire.” A Goldman Sachs note published in September estimated Tokyo Gas had unrealized real estate gains of 447 billion yen—reported as the highest among its peer group, and equal to just over a quarter of its market capitalization at the time.

This is where Elliott sees opportunity. The fund believes Tokyo Gas could free up capital for shareholder returns and for growth by selling non-core assets—specifically calling out property tied to the Park Hyatt Tokyo and land in Toyosu where the city’s biggest fish market is located. Tokyo Gas’s own securities report values its real estate assets at 580 billion yen, far below Elliott’s estimate of more than 1 trillion yen.

As market expert Travis Lundy put it: “Tokyo Gas is effectively running a long/short fund—short its own stock to finance long positions in real estate, securities holdings—worth 600 billion yen to one trillion yen. It is an inefficient use of capital.”

To be fair, Tokyo Gas doesn’t present itself as a pure-play utility. It operates across five business segments: Gas, Electric Power, Overseas, Energy Related, and Real Estate. In other words, the company is explicitly structured to be more than pipelines and molecules.

And management has a ready defense. A Tokyo Gas spokesperson noted that the urban business segment, which accounted for about a tenth of the company’s profit last year, has steadily improved and helps stabilize the energy business.

That’s the classic conglomerate argument: diversification smooths earnings and reduces risk. But in an era of activist investors—and Tokyo Stock Exchange reforms explicitly pushing companies to raise returns and improve capital efficiency—it’s a harder case to make. Stability is nice. The question Elliott is asking is sharper: at what cost to shareholder value?

IX. Elliott Arrives: The Activist Siege of 2024

The filing hit on November 19, 2024 like a thunderclap. Elliott Investment Management disclosed that it had built a 5.03% stake in Tokyo Gas—enough to trigger a public report to Japan’s finance ministry, and enough to signal something more than passive interest. In the filing, Elliott said it may make “important proposals” to the company.

It was also a telling milestone for Elliott itself. It was the fund’s fourth Japanese investment that year, and the first time since 2019 it had crossed the 5% line—the threshold that turns a quiet position into a very loud message.

The disclosure immediately put Elliott among Tokyo Gas’s largest shareholders. As of March 31, the top holders included The Master Trust Bank of Japan, with nearly 16%, and Nippon Life Insurance, with 7.8%. Elliott, at just over 5%, was suddenly in the room—whether management wanted it there or not.

The market’s reaction made the point for them. The next day, Tokyo Gas shares surged more than 12%, to around 4,284 yen. Investors weren’t pricing in a new pipeline or a new LNG contract. They were pricing in the possibility of change.

And Elliott’s agenda was exactly what you’d expect from an activist that has made a career out of squeezing value out of complex balance sheets. The Financial Times reported that Elliott planned to pressure Tokyo Gas to sell non-core assets, with a particular focus on its sprawling property portfolio. The fund reportedly argued that the unrealized value of Tokyo Gas’s real estate could be as high as 1.5 trillion yen—about $9.7 billion.

More specifically, Elliott’s view was that Tokyo Gas could materially improve capital efficiency by selling down real estate that doesn’t belong inside a utility. The fund believed the company should consider selling more than 75 properties and projects, including assets tied to the Park Hyatt Tokyo, with the combined value potentially reaching that same 1.5 trillion yen range.

This was not an isolated crusade. Elliott, which manages about $70 billion, had been ramping up its Japan campaign, building stakes in companies like Sumitomo and SoftBank Group. Tokyo Gas was the latest—and in some ways the most symbolically potent—because it combined critical national infrastructure with a balance sheet full of “stuff” that looked, to outsiders, like a legacy collection.

The broader backdrop matters. Japanese companies across sectors were facing sharper shareholder scrutiny, and the Tokyo Stock Exchange had been pushing reforms aimed at improving capital efficiency, accountability, and returns. The result has been a slow but real shift in behavior: conglomerates selling subsidiaries, trimming cross-holdings, and divesting businesses that don’t clear a higher bar.

Real estate is a particularly tempting lever in Japan, where book values often lag market reality. By one estimate, there’s a gap of 22 trillion yen between the values companies carry for real estate on their balance sheets and what those assets could fetch if sold. That mismatch is basically an invitation to activists: point at the gap, demand a sale, and force the market to recognize the difference.

Tokyo Gas’s first response was careful—measured, but not dismissive. President Shinichi Sasayama said the company regularly reviews assets to improve capital efficiency, and had already identified assets to sell in order to fund growth investments. “We’ve identified assets that should be sold to fund necessary growth investments, not limited to real estate, to enhance corporate value,” he told Reuters. Depending on the outcome, proceeds could go toward growth spending or shareholder returns.

Tokyo Gas also signaled that it understood the scoreboard had changed. It targeted an ROE of 8.1% in fiscal 2025, with a longer-term ambition of exceeding 10% by 2030. It had already taken a shareholder-friendly step with a 40 billion yen buyback program that concluded in January 2025.

In other words: Tokyo Gas wasn’t pretending it was still 1995.

But it also wasn’t promising Elliott what Elliott came for.

So the story now turns from disclosure to pressure—and to a question that sits at the center of modern Japan’s corporate shift: will Tokyo Gas make the kind of structural moves activists are demanding, or will Elliott decide it needs to force the issue?

X. Playbook: Business and Strategic Lessons

Tokyo Gas’s 140-year journey is a masterclass in infrastructure capitalism—both what it rewards, and what it punishes.

What Tokyo Gas Got Right

First: first-mover advantage in infrastructure is real, and it compounds. When Tokyo Gas built an LNG receiving terminal at Negishi in 1969, it wasn’t just adding a facility. It was laying down a moat made of concrete, steel, permits, and operating know-how—something competitors can’t simply copy without enormous capital and years of lead time. That advantage is still visible in the system today.

Second: consolidation is how you turn a local utility into a regional fortress. From absorbing Chiyoda Gas in 1912 to merging with Chiba Gas in 2016, Tokyo Gas kept making the same wager: density wins. The tighter the footprint, the more efficient the network, the stronger the incumbent advantage.

Third: when the rules changed, Tokyo Gas didn’t just defend—it attacked. As deregulation opened the door to competition, it moved into electricity instead of waiting to be boxed in. Today, it serves more than 4 million electricity customers, built on the same strengths that made it dominant in gas: trusted billing relationships, operational scale, and infrastructure competence.

Fourth: going upstream wasn’t only about chasing growth—it was about changing the risk profile of the entire enterprise. The Rockcliff acquisition added production, yes. But more importantly, it created a hedge against LNG price swings. When gas prices rise and imported fuel gets painful, upstream revenues can help offset the hit. When prices fall, Tokyo Gas benefits on the purchasing side. That’s not luck; it’s portfolio design.

Fifth: patience is an underrated competitive advantage in industries with decades-long payback cycles. LNG terminals, pipelines, and power plants don’t reward quarterly thinking. Tokyo Gas could make those investments because stable cash flows and a long-term orientation made “wait 20 years” a viable strategy, not a career risk.

What’s Being Questioned

Elliott’s critique lands on one theme: capital allocation. Is the Park Hyatt Tokyo really core to a gas utility? Probably not—and the fact that it’s even a serious question captures the widening gap between traditional Japanese corporate portfolio-building and what modern public-market investors want to fund.

Then there’s the return bar. An 8% ROE target is hard to defend in global markets, where large regulated utilities often target something closer to the low double digits. You can debate the reasons—conservatism, accounting, the structure of Japan’s market—but the headline still invites pressure: why should shareholders accept less?

Real estate diversification also looks different in hindsight. It made sense when monopolies threw off predictable cash and there weren’t many obvious places to reinvest. In a more competitive era, that same capital starts to look like trapped value—money that could be deployed into core energy, decarbonization, overseas growth, or simply returned to shareholders.

And finally, the structure itself is on trial. Vertical integration—owning pieces from upstream supply to end-customer delivery—has an intuitive logic in energy. But horizontal sprawl into hotels and office buildings creates complexity without clear operational synergies. It might stabilize profits, but it can also dilute focus and depress valuation.

The Japanese Corporate Governance Evolution

Tokyo Gas is also a case study in Japan’s governance shift finally getting teeth. Abenomics-era reforms, Tokyo Stock Exchange pressure on companies trading below book value to explain how they’ll improve, and the steady rise of activist involvement are changing the terms of engagement between management teams and shareholders.

And this isn’t just “America versus Japan.” The pressure is increasingly coming from inside the house. Japanese institutional investors—pension funds, insurers, asset managers—are asking for the same discipline around returns and capital efficiency that global markets have normalized.

What happens next at Tokyo Gas will echo beyond this one company. If it meaningfully improves capital allocation and shareholder returns, it becomes proof that activism can unlock change in Japan. If it resists while still compounding value, it becomes evidence that the old model can adapt without being dismantled. Either way, the era of politely ignoring shareholders is ending.

XI. Competitive Position: Porter's Five Forces and Hamilton's Seven Powers

To see where Tokyo Gas is truly strong—and where Elliott thinks it’s complacent—you have to look past the headlines and into the competitive physics of the business. Some of those forces are structural and almost impossible to change. Others are self-inflicted, and therefore fair game.

Threat of New Entrants: LOW to MEDIUM

If you want to start a new “Tokyo Gas,” you run into a basic problem: you’d need to rebuild Tokyo.

Gas distribution is a pipes business, and duplicating a citywide network is economically unrealistic. In practice, the network is the choke point. New retailers can compete for customers, but they do it by riding on Tokyo Gas’s infrastructure—and paying regulated fees to use it. Japan also doesn’t have a single nationwide pipeline system like the U.S. or much of Europe. Each city gas company maintains the pipes in its own service area, which keeps the underlying distribution network a local natural monopoly even after retail liberalization.

Then there’s LNG. Importing LNG at scale isn’t just “buy gas and ship it.” Receiving terminals take enormous capital, heavy permitting, and hard-earned operational know-how. Tokyo Gas operates three major terminals; a would-be entrant would have to replicate that capability—or depend on incumbents for supply.

Still, deregulation did create a real, if bounded, entry point: the customer relationship. Electricity companies can bundle gas sales. New brands can compete on pricing and service. Some have taken share. The threat exists, but the infrastructure realities keep it contained.

Supplier Power: MEDIUM

Tokyo Gas has spent decades doing the obvious thing you do when your country has no domestic fuel: diversify the source of supply. It imports LNG from multiple countries, including Australia, Malaysia, Qatar, Russia, and the United States, rather than relying on a single counterparty. It also receives LNG at its major terminals, and that physical capability matters—because in tight markets, being able to take delivery is as important as having a contract.

The company’s move into upstream production, including the Rockcliff acquisition, also changes the balance. Owning production brings part of the supply chain in-house and reduces dependence on external suppliers.

But supplier power never goes to zero in LNG. It’s a globally traded commodity, and the price risk is real. Long-term contracts and hedging can smooth the ride, but they don’t eliminate exposure to global markets.

Buyer Power: LOW to MEDIUM

Most residential and small business customers don’t negotiate like industrial buyers. They also face practical switching friction—new plans, new billing, sometimes different service bundles—even if the physical gas service still runs through the same pipes.

Large industrial customers have more leverage, especially in deregulated segments where volume and flexibility matter. Even so, the fact that the top three gas companies account for about 80% of total sales volume tells you buyer power is limited by market structure. Customers can shop, but they’re shopping inside an oligopoly.

Threat of Substitutes: MEDIUM to HIGH

The long-term threat to any gas utility is simple: electrify everything, and decarbonize the grid.

Heat pumps, electric heating, and future fuels like hydrogen all compete—directly or indirectly—with natural gas demand. Japan’s carbon-neutrality ambition puts structural pressure on fossil fuels over time.

Tokyo Gas’s counter is the role natural gas plays today: cleaner than coal, dispatchable and reliable compared with intermittent renewables, and deeply embedded in existing infrastructure. That “transition fuel” positioning offers protection in the intermediate term, even if the long-term direction of travel is clear.

Industry Rivalry: MEDIUM

Post-deregulation, competition got louder—more discounting, more bundling, more marketing. But the underlying structure didn’t flip. Tokyo Gas, Osaka Gas, and Toho Gas still dominate their home regions, and cross-regional rivalry hasn’t meaningfully broken those positions. This is competition at the margins, not a winner-take-all battlefield.

Hamilton's Seven Powers Analysis

If you apply Hamilton Helmer’s framework, Tokyo Gas looks less like a typical competitive business and more like a bundle of durable advantages built out of concrete, land, and operating experience:

Scale Economies: The network is classic scale. The big fixed-cost assets—pipelines, terminals, control systems—get amortized across millions of accounts. Add customers, and returns can improve without costs rising in lockstep.

Network Effects: There aren’t strong “social network” effects here, but density creates a cousin of it: operational efficiency. Serving a tight, urban footprint is cheaper per customer than serving a scattered one.

Switching Costs: Connections to the network, long-standing billing relationships, and compatibility with household and commercial equipment all create friction. Customers can switch providers on paper, but the system is still built around the incumbent’s infrastructure.

Counter-Positioning: Tokyo Gas’s integrated model—import capability, infrastructure, and retail presence—gives it strategic options that pure retailers or single-segment players don’t have.

Cornered Resource: The hard-to-replicate assets are the point: the pipeline network, LNG terminals, and massive installed customer base. And separately, its prime Tokyo land positions—valuable, scarce, and impossible to recreate.

Process Power: Decades of LNG handling, safety discipline, and operational expertise are a real advantage. These aren’t capabilities a newcomer can buy off the shelf.

Branding: Tokyo Gas is a trusted name in its territory. Branding matters less in utilities than in consumer products, but trust still counts when the service is essential and safety-sensitive.

XII. Key Performance Indicators for Investors

If you’re trying to understand where Tokyo Gas goes from here—and whether the company is actually responding to the new era of shareholder pressure—there are three metrics that tell you the most, the fastest.

1. Return on Equity (ROE)

ROE is the scoreboard for the whole Elliott debate. It’s the simplest way to ask: is management turning a massive asset base into meaningful returns, or just preserving it?

Tokyo Gas has said it’s aiming for ROE of 8.1% in FY2025, and that it wants to exceed 10% by 2030. Hitting that trajectory would be a real improvement. But it also comes with an implied challenge: that long-term target still reads as conservative versus global peers, which is exactly why activists see room to push.

So the real tell isn’t the target—it’s the path. If ROE rises because Tokyo Gas is selling underused real estate, shrinking low-return holdings, buying back shares, and deploying capital into higher-return growth, that’s a genuine shift. If ROE stalls, it’s a sign the company is still operating with an old-world balance sheet in a new-world market.

2. Overseas segment profit contribution

Tokyo Gas has made its ambition explicit: by 2030, it wants around half of profits to come from overseas. This is the “second engine” story—how the company offsets a mature domestic market and the long-term uncertainty around Japan’s energy mix.

That means this KPI becomes a direct test of the U.S. shale and LNG-linked strategy. Deals like the Rockcliff acquisition, continued shale development, and any move into a Louisiana LNG project should show up here over time. If overseas profits scale and remain resilient, it validates the pivot. If they don’t—or if they come with messy write-downs and weak returns—it reinforces the activist critique that Tokyo Gas is wandering outside its circle of competence.

3. Customer retention rate and competitive share

Deregulation turned the customer relationship into contested ground. You can no longer assume the household account is “yours forever” just because the pipe is. Attrition is the early-warning signal.

Nationally, about 4 million accounts have switched from traditional city gas providers to new entrants. Against that backdrop, Tokyo Gas’s job is twofold: defend the core gas base and keep growing in electricity, where it’s already built meaningful scale.

The pattern to watch is simple. A utility that holds onto gas customers while adding electricity accounts is showing that its moat is still working—brand trust, service quality, bundling, and operational scale. If retention weakens or customer acquisition slows, the competitive pressure that deregulation introduced finally starts showing up in the numbers.

XIII. Risk Factors and Regulatory Considerations

Commodity Price Exposure

For all of Tokyo Gas’s long-term contracts, hedging, and newfound upstream production, it still lives in the weather and the tape. LNG is priced in global markets, and swings in commodity prices can move quickly through earnings. As the company pushed further into unregulated businesses—especially U.S. shale—its results became harder to predict. That volatility was a big enough concern that S&P Global Ratings revised its outlook on Tokyo Gas to negative in November 2024. Layer on exchange rates and unusually hot or cold seasons, and the range of possible outcomes widens fast.

Nuclear Restart Trajectory

Japan’s nuclear restart program is the single most direct lever on long-term gas demand. Nuclear accounted for about 6% of Japan’s electricity generation in 2023, but the policy direction is clear. A draft of Japan’s seventh long-term energy plan, released December 17, 2024, said nuclear should account for 20% of Japan’s energy supply in 2040. If restarts accelerate—or if lifetime extensions become routine—LNG demand could fall faster than Tokyo Gas expects, leaving the company with more import capability than the domestic market needs.

Decarbonization Transition Risk

Japan’s commitment to carbon neutrality by 2050 puts an expiration date on unabated fossil fuel growth. Tokyo Gas is trying to stay ahead of that curve—investing in hydrogen, synthetic methane, and renewable energy—but the transition path is still uncertain, and the timing matters. The company declared in 2019 that it aimed to achieve net-zero CO2 emissions by 2050, and in 2024 it announced a detailed roadmap to get there. The risk is less about intent and more about execution: technologies, regulation, and customer adoption all have to move in sync.

Activist and Governance Pressure

Elliott’s stake adds a different kind of risk: not operational, but organizational. Constructive engagement could sharpen capital allocation and accelerate portfolio clean-up. But activist campaigns can also consume management attention, create strategic whiplash, and inject uncertainty into long-term plans. Much of this will come down to whether Tokyo Gas can show credible, measurable progress on capital efficiency—fast enough to satisfy shareholders, without destabilizing the business.

Currency Risk

As Tokyo Gas becomes more international, it inherits currency exposure. LNG purchases are typically priced in dollars, and its growing U.S. shale revenues are also dollar-denominated. In some ways that creates a natural hedge—costs and income moving in the same currency—but it also introduces translation risk. Depending on where the yen trades, the same underlying operating performance can look very different in reported results.

XIV. Concluding Observations

Tokyo Gas is hitting an inflection point that looks a lot like Japan’s own. Over 140 years, it built things you can’t easily replicate: a dense urban pipeline network, LNG receiving terminals, deep operating expertise, and the trust that comes with keeping the Kanto region running day after day. That’s the kind of advantage no activist can conjure up—and no board can replace quickly, even if it wanted to.

But Elliott’s core question still lands: is Tokyo Gas putting its capital to its best use?

A Park Hyatt is a world-class asset. It’s also hard to argue it’s essential to delivering energy. And in Japan, where real estate has often sat on balance sheets at values far below what the market would pay, that gap becomes more than an accounting curiosity. It becomes a pool of trapped capital—capital that could be recycled into higher-return growth, decarbonization investments, or simply returned to shareholders.

Management has responded the way a century-old steward tends to: carefully. It’s acknowledged the need to review assets and improve capital efficiency, while also defending the stabilizing logic of diversification. The share buyback and the push toward higher ROE are signals that Tokyo Gas recognizes the rules have changed. The open question is whether those steps are a starting point—or the full offer.

For long-term investors, Tokyo Gas is still a rare bundle: core Japanese infrastructure plus global optionality. You get exposure to LNG markets, a growing U.S. shale position, and a credible attempt to modernize the customer-facing side of the business through the Octopus Energy partnership. If Elliott’s presence accelerates clearer capital allocation and portfolio discipline, that could be a catalyst for value that the market has been discounting for years.

The risks don’t go away. Earnings will always feel commodity cycles. Nuclear restarts can compress domestic gas demand. And the long-term direction of travel—carbon neutrality—puts pressure on every fossil-fuel incumbent to reinvent itself without breaking reliability along the way.

Still, the company’s moat is physical, its role is essential, and its strategy is already evolving. Shibusawa Eiichi founded Tokyo Gas in an era when gas lamps were the symbol of modern life. Nearly a century and a half later, the symbol has changed. The challenge is the same: build the next layer of infrastructure that makes a society work—this time under the constraints of decarbonization and the expectations of modern capital markets. How Tokyo Gas balances those two forces will define its next chapter.

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music