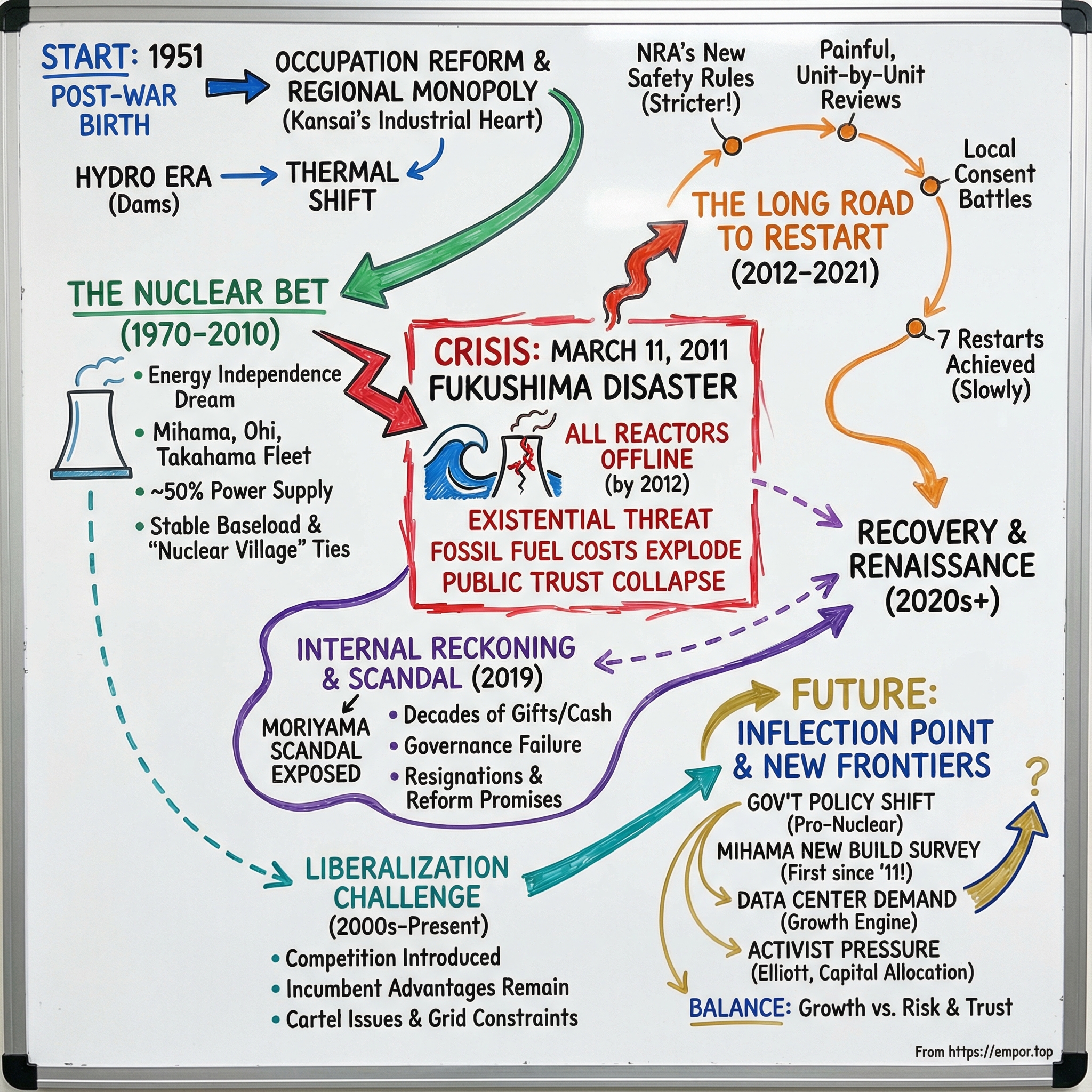

Kansai Electric Power Company: Powering Japan's Industrial Heart Through Crisis and Transformation

I. Introduction & Episode Roadmap

Picture this: a sweltering August afternoon in 2012. Across Japan’s Kansai region—Osaka, Kyoto, Kobe—everyone is watching the same thing: the power reserve number.

Air conditioners are roaring. Factories are deciding whether to slow production before they’re forced to. Inside Kansai Electric Power Company, executives are glued to control-room dashboards as the margin for error narrows.

Sixteen months earlier, eleven nuclear reactors had supplied close to half of Kansai’s electricity. Now every single one was offline. And KEPCO—Japan’s second-largest utility, and for decades its most nuclear-dependent—was staring down an existential question.

This is the story of what happened next.

Because KEPCO didn’t just survive the post-Fukushima shutdown. It fought its way back. In pursuit of Japan’s 2050 decarbonization goal, the Kansai Electric Power Group laid out its “Zero Carbon Vision 2050” and hit its CO2 reduction targets two years early, helped by the restart of seven nuclear reactors. The arc from near-blackout panic to nuclear revival is one of the most dramatic reinventions in modern Japanese industry.

The stakes are huge because Kansai is huge. The region may be compact on a map, but economically it’s a heavyweight—nearly 16% of Japan’s GDP and the country’s second-largest industrial base after greater Tokyo. Osaka is a commercial powerhouse. Kyoto blends old-world cultural gravity with high-end technology. Kobe anchors a major port economy. Keeping all of that running takes reliable, always-on baseload power—exactly what nuclear was built to provide.

So the central tension in this story is as simple as it is brutal: what does a utility do when the technology it built its entire system around gets politically and socially shut down overnight? And even if you manage to restart, how do you do it while navigating scandal, deregulation, and a national push to decarbonize?

Fast-forward to November 2025 and you get a clue to the answer. KEPCO said it had begun a survey to consider building a new nuclear reactor in Mihama, Fukui Prefecture—the first such survey in Japan since the March 2011 Fukushima accident. That’s not just recovery. That’s leadership. It’s KEPCO signaling that it believes the country has turned a page—and that it intends to shape what comes next.

Along the way, we’ll follow a set of threads that keep colliding: technology and politics, local communities and national strategy, corporate governance and old-school patronage. We’ll start with KEPCO’s birth in the American occupation and the scramble to electrify a rebuilding nation. We’ll track its nuclear buildout through the oil shock era, then drop into the crucible of the Fukushima aftermath. We’ll unpack the Moriyama scandal, where decades of bribery and gifts were hiding in plain sight. And we’ll look at what “competition” really meant after Japan deregulated its power markets—why hundreds of new retailers showed up, yet the incumbents still held the high ground.

And yes, there’s an investing angle here too. KEPCO controls one of the most valuable nuclear fleets on the planet, and it’s operating in a Japan that is now leaning back toward nuclear as policy. Activist hedge fund Elliott Investment Management has taken a roughly 4–5% stake and is pushing on non-core assets and shareholder value. But KEPCO also carries deep scars—from scandal, from regulatory risk, from the hard realities of running aging infrastructure in a newly competitive market. If you want to understand where this company can go next, you have to start at the beginning.

So let’s go back—back to post-war Japan, and the moment the country decided how power would be built, priced, and controlled.

II. Birth from Occupation: Post-War Japan's Electric Revolution (1945–1970)

The MacArthur Reorganization

May 1, 1951. Japan was still under occupation, and General Douglas MacArthur’s headquarters signed off on a decision that would quietly define the country’s energy system for the next seventy-plus years.

The plan was simple and sweeping: reorganize the electric power industry, divide the country into nine geographic blocks, and create nine privately owned utilities to serve them. Kansai Electric Power Company was born out of that map—responsible for western Japan’s industrial core.

This wasn’t just an infrastructure project. It was policy by demolition. The reorganization was carried out under the Law for the Elimination of Excessive Concentration of Economic Power—American-style trust-busting aimed at dismantling the wartime industrial structure. Before and during the war, Japan’s electricity system had been consolidated and aligned with state priorities. Occupation authorities wanted the opposite: dispersed control, fewer concentrated power centers, and an economy less capable of snapping back into militarized production.

KEPCO’s origin under that framework matters because it inherited more than power plants and wires. It inherited a protected service territory. In Japan, each regional utility effectively owned its geography—exclusive rights to serve its block, a natural monopoly that would remain intact for decades. Even later, when “deregulation” arrived, those borders and incumbency advantages didn’t vanish. They just became the playing field.

And the timing could not have been more unforgiving. Japan’s reconstruction was accelerating fast. Industrial output was racing back, cities were rebuilding, and electricity demand surged ahead of supply. In Kansai—dense, factory-heavy, intensely urban—shortages were especially painful. Rolling blackouts hit production lines and daily life. The brand-new KEPCO faced the oldest utility problem in the book: build capacity, quickly, or watch the region stall out.

The Hydroelectric Era

Japan’s terrain practically begs you to think “hydro.” Mountains cover most of the country, rainfall is plentiful, and steep elevation changes make ideal conditions for dams. In the early 1950s, hydroelectricity was the most realistic way to add meaningful generation capacity at scale.

But KEPCO ran into a classic post-war bind: politics wanted cheap power, while engineering demanded capital. National pricing policies kept electricity rates low to support reconstruction, squeezing utilities so tightly they struggled to cover costs, let alone fund new projects. Only after rate reviews improved KEPCO’s finances could it start building in earnest.

The first big statement was Maruyama: a 125-megawatt hydro plant that, when completed in 1954, was the largest in Japan. It helped stabilize Kansai’s supply situation and proved KEPCO could execute major projects—on time, on budget, at national scale.

Then came the project that turned into legend. In 1956, KEPCO launched the Kurobegawa No. 4 hydroelectric project, deep in the Japanese Alps. It wasn’t just large; it was brutal. Access required tunneling through unstable mountains. Crews fought underground springs, avalanches, and punishing cold. Over the seven-year build, 171 workers died. When it was finally completed in 1963, Kurobegawa No. 4 didn’t just produce electricity—it became a symbol of post-war Japanese resolve, later immortalized in a best-selling novel and film.

For KEPCO, the takeaway was institutional. The company learned how to run multi-year, high-risk, technically complex infrastructure builds—skills it would lean on heavily when it moved from dams to reactors.

The Shift to Thermal and LNG

Even while hydro was delivering wins, the limits were obvious. Good dam sites were finite. New ones were farther away, harder to reach, and slower to develop. Meanwhile, Kansai’s demand curve didn’t care about geography. It just kept climbing.

So by the mid-1950s, the center of gravity shifted toward thermal power. Thermal plants could be built closer to where electricity was actually consumed, with shorter timelines and more predictable output.

Fuel choices, too, became a moving target. Utilities started with domestic coal, then shifted to heavy oil as imports became cheaper and easier than extracting limited, expensive reserves at home. As pollution concerns grew—especially sulfur emissions—fuel sourcing shifted again, from heavy oil to crude oil. And then, with an eye toward both cleaner air and less reliance on oil, the industry began introducing LNG-fired plants.

The broader lesson was uncomfortable, and it never really went away: Japan has almost no domestic fossil fuel resources. Coal, oil, LNG—nearly all of it arrives by ship. That dependence made energy feel less like a commodity and more like a strategic vulnerability. And it set the stage for the next, much bigger bet.

The Nuclear Bet Begins

In December 1966, KEPCO started construction on its first nuclear power plant: Mihama Unit No. 1, in Fukui Prefecture. It was a 340-megawatt pressurized water reactor imported from the United States—technology licensed from Westinghouse. This wasn’t just a plant; it was Japan aligning its civilian nuclear future with American reactor design and expertise.

And KEPCO couldn’t have picked a more symbolic moment to flip the switch. In August 1970, Mihama Unit No. 1 sent its first nuclear-generated electricity to Osaka’s EXPO ’70—the World’s Fair that showcased Japan’s reemergence as a modern industrial power. Nuclear energy arrived wrapped in national ambition and technological prestige.

By the end of this era, the shape of KEPCO was set. A company created by occupation-era policy, operating a protected territory, trained by massive infrastructure projects, and increasingly tied to national energy strategy. The implicit bargain was already forming: the government would support the scale of investment required to power Kansai, and KEPCO would deliver reliability—and align with the country’s strategic priorities.

Next, those priorities would collide with global geopolitics, oil shocks, and the promise of nuclear independence.

III. The Nuclear Gambit: Japan's Energy Independence Dream (1970–2010)

Why Nuclear Made Sense for Japan

To understand KEPCO’s four-decade sprint into nuclear, you have to start with Japan’s core energy fact: the country imports almost everything it burns. Roughly 90% of its energy comes from overseas. That’s not an abstract statistic—it’s a strategic vulnerability. And it turned into a national trauma in 1973, when the oil shock hit and the idea of Japan’s “economic miracle” suddenly looked frighteningly fragile.

So Japan pivoted. If it couldn’t become energy-independent, it could at least stop being oil-dependent. Nuclear power offered something no other option could: concentrated, predictable energy from a fuel supply you could stockpile. Enriched uranium is compact, dense, and doesn’t arrive in an endless procession of tankers that can be cut off by geopolitics.

For KEPCO, the logic was even more compelling. Kansai’s customers weren’t just households; they were factories, railways, and the heavy industry that made the region Japan’s industrial heart. They needed electricity that didn’t blink—steady, round-the-clock baseload. Nuclear was built for that. Once online, a reactor could run continuously for long stretches, producing stable output that didn’t depend on rainfall, seasonal hydro conditions, or daily swings in fuel prices.

Then came the second oil shock in 1979, triggered by the Iranian Revolution. Any lingering doubts evaporated. Japan accelerated nuclear build schedules, and KEPCO leaned in hard. Through the 1980s and beyond, the company expanded its nuclear program with a cadence that’s hard to imagine today: new units coming online regularly, each one locking in another chunk of stable, non-oil generation for the Kansai grid.

Building the Nuclear Fleet

KEPCO built its nuclear identity in Fukui Prefecture, on the Sea of Japan side, just north of Kyoto. Three sites—Mihama, Ohi, and Takahama—became the backbone of the company’s power system. Over time, those sites housed eleven commercial reactors. At its height, KEPCO was getting about half of its electricity from nuclear—an extraordinary level of concentration that delivered massive benefits, and baked in massive risk.

The buildout stretched from the early Mihama units to later additions like Ohi Units 3 and 4 in the early 1990s. The technology was consistent: American-derived pressurized water reactors. That standardization was a strategic choice. Unlike TEPCO, which operated a mix of reactor types, KEPCO largely stuck with one. That meant simpler training, shared maintenance practices, and a more unified supply chain for parts and expertise. It also meant a different kind of systemic exposure: a problem affecting that reactor class could ripple across the entire fleet.

And none of this happened in a vacuum. Nuclear plants don’t just generate electricity; they generate local economies. Construction brought waves of jobs, and operations meant hundreds of stable positions for decades. On top of that, national and prefectural governments directed subsidies and public works spending into host communities—roads, schools, community facilities, local services. Over time, many towns became financially dependent on their plants, and local politics adjusted accordingly. KEPCO wasn’t just buying land and building reactors—it was embedding itself into the economic survival of entire municipalities.

The Mihama Accident of 2004

Then, in August 2004, the first major crack in the story became impossible to ignore.

At Mihama Unit 3, a steam pipe burst and killed five KEPCO workers, injuring six others. This wasn’t a radiation event, and it wasn’t a dramatic reactor failure. It was something more unsettling precisely because it was so mundane: a carbon steel pipe had never been inspected since the unit began operating in 1976. Over decades, the flow of steam had gradually eroded the metal until the wall became so thin it failed catastrophically.

The implications were brutal. The accident wasn’t about one missed inspection—it exposed an inspection and maintenance regime that had holes big enough to hide in. Investigators found large numbers of components that hadn’t been checked, and record-keeping so weak the company struggled to even identify what needed examination.

For KEPCO, it was a reputational gut punch. For anyone thinking about incentives, it was a warning flare: the industry was entering an era of tighter margins and rising scrutiny, and the tension between cost discipline and safety culture was becoming harder to manage. KEPCO promised reforms, but the deeper question lingered: had the system gotten too comfortable?

Seven years later, after Fukushima, that question would stop being theoretical.

The "Nuclear Village" and Its Critics

By this point, Japan had a name for the ecosystem that kept nuclear expansion moving: the “nuclear village,” genshiryoku mura. The phrase captured a tight network of utilities, regulators, politicians, and academics who—critics argued—reinforced one another’s assumptions, prioritized growth, and minimized dissent. In that framing, the industry wasn’t simply regulated; it was socially and politically insulated.

KEPCO sat near the center of that world. Executives moved through industry bodies and government committees. Relationships with politicians in nuclear-hosting districts were close and constant. The company funded research, ran public campaigns emphasizing safety, and brought former regulators into advisory roles—practices that, in aggregate, made outsiders question where oversight ended and alignment began.

And beneath that respectable surface, something darker had already started. As early as 1987, a local fixer in Takahama—Eiji Moriyama, a former deputy mayor—began passing cash and gifts to KEPCO officials, tied to steering construction and related contracts to connected firms. It wasn’t a one-off. It became a pattern—quiet, normalized, and hidden from shareholders and the public for decades.

By the eve of Fukushima, the picture was clear. KEPCO had become Japan’s nuclear champion: deeply experienced, heavily invested, and structurally dependent on a fleet that was aging in place. That nuclear scale would later help it fight for restarts. But the same entanglements—political, financial, cultural—would also make its reckoning far messier than a simple engineering problem.

IV. March 11, 2011: The Day Everything Changed

Fukushima and the Nuclear Shutdown

At 2:46 p.m. on March 11, 2011, Japan lurched.

A magnitude 9.0 earthquake—one of the strongest ever recorded—hit off the Pacific coast of northeastern Japan. Across eastern Japan, nuclear plants did what they were designed to do in a quake: reactors automatically shut down. For a brief moment, it looked like the system had worked.

Then the ocean arrived.

The earthquake had triggered a massive tsunami, with waves topping forty feet in some places. At TEPCO’s Fukushima Daiichi station, water poured over seawalls built for a different world. Seawater flooded the site, knocked out backup diesel generators and batteries, and stripped the reactors of the power they needed to keep cooling. Over the following days, three reactors melted down. Hydrogen explosions ripped through buildings. Japan had its worst nuclear accident since Chernobyl—and a national crisis that wasn’t going to stay contained to Fukushima.

KEPCO’s nuclear plants sat on the Sea of Japan coast, not the Pacific. They weren’t hit by the tsunami. But they didn’t need to be. The political shockwave was enough.

Public opinion pivoted hard. Anti-nuclear protests swelled into the tens of thousands. Local leaders who’d once championed nuclear plants started demanding shutdowns, “stress tests,” and new safety reviews. The assumption that reactors were a normal part of Japan’s energy mix collapsed almost overnight.

By late March 2012, only one of Japan’s 54 reactors was operating: Tomari-3. When it went offline for maintenance on May 5, 2012, Japan produced no nuclear-generated electricity for the first time since 1970.

For KEPCO, the timeline was just as stark. By January 2012, only one of its eleven reactors was still running. By March, its last one went dark. In the span of a year, a company built around nuclear baseload lost roughly half its generating capacity.

KEPCO's Existential Crisis

Once the reactors stopped, the math turned vicious.

Nuclear plants have low variable costs—on the order of about a yen per kilowatt-hour, largely fuel. To replace that missing power, KEPCO had to burn imported fossil fuels, especially LNG, at something like ten to twelve yen per kilowatt-hour. Same electricity. Completely different cost structure.

Industry-wide, Japan’s utilities were suddenly spending an additional ¥3.8 to ¥4.0 trillion a year on fuel imports. KEPCO’s generation cost surged—up 56% in fiscal 2012, from ¥8.6 per kilowatt-hour to ¥13.5. Across the sector, annual losses were nearing ¥1 trillion.

And it wasn’t just expensive. It was chaotic.

Asia already paid some of the highest LNG prices in the world because the region imports so much of its fuel. After Fukushima, Japanese utilities were forced into the spot market, chasing cargoes and outbidding each other just to keep plants running. KEPCO’s procurement teams scrambled through emergency contracts at premium prices. The company that had spent decades trying to escape fuel dependency was suddenly right back in the grip of global commodity markets.

Soon, the pain hit customers. KEPCO sought, and received, approval to raise industrial tariffs in 2012 and residential tariffs in 2013—its first hikes in decades. Big power users were livid. In a weak economy, higher electricity costs weren’t a nuisance; they were a strategic threat. Some customers shifted production elsewhere. Others invested in their own generation. Everyone demanded to know how a utility that had promised stable, affordable power ended up here.

The Community Pressure

The most uncomfortable pressure wasn’t coming from Tokyo. It was coming from home.

In 2012, KEPCO officials went door to door in towns hosting its nuclear plants, polling residents and answering questions about safety. That kind of personal, ground-level outreach was a break from the old model—utilities built, communities benefited, and the relationship ran mostly one way.

The national picture showed just how deep the rupture was. Before 2011, Japan’s 54 reactors supplied roughly 30% of the country’s electricity. More than a decade later, only 13 had restarted with local approval.

Then Kansai’s biggest cities stepped in. On February 27, 2012, Kyoto, Osaka, and Kobe jointly asked KEPCO to break its dependence on nuclear power—an extraordinary demand from the region’s economic core. And Osaka wasn’t just a customer; it was KEPCO’s largest shareholder, owning about 9% of the company. The city announced it would push at the June 2012 shareholders’ meeting to split KEPCO—separating power generation from transmission.

The resistance wasn’t only political. It was legal.

In Shiga Prefecture, on the shores of Lake Biwa—Japan’s largest freshwater lake and a drinking-water source for millions—citizens filed a lawsuit seeking a court order to block reactor restarts. Their fear was simple: an accident at KEPCO’s coastal plants could contaminate the lake and cripple the region’s water supply. It was a new kind of fight: residents trying to stop nuclear operations not with protests or petitions, but through the courts.

For investors, the post-Fukushima lesson was harsh and clarifying. KEPCO’s reactors hadn’t been destroyed. Technically, many were still usable. What vanished was the social and political permission to run them. And in a heavily regulated industry, that permission is the asset.

Winning it back would take years—new rules, new oversight, expensive upgrades, and endless negotiation with regulators and local communities. And even then, nothing guaranteed the lights would ever come back on.

V. The Long Road to Restart (2012–2021)

The First Glimmers of Hope

The first real break came in mid-April 2012—barely thirteen months after Fukushima. After a series of high-level meetings that ran straight through the Prime Minister’s office, the Japanese government approved the restart of KEPCO’s Ohi Units 3 and 4. They were the first reactors in Japan cleared to operate after the disaster.

The driver wasn’t confidence. It was necessity. Summer was coming, and the government feared that shortages in Kansai wouldn’t just be inconvenient—they could force factories to shut down and leave vulnerable people at risk in the heat.

Even so, getting to “yes” was painful. Prime Minister Yoshihiko Noda personally pressed Fukui’s governor and the mayor of Ohi to sign on. Fukui, with communities that had long relied on nuclear jobs and subsidies, was far more open to the idea than Kansai’s big cities, where public pressure was turning toxic.

In July 2012, Ohi 3 and 4 finally went back online. For KEPCO, it was a badly needed moment of relief—financially, operationally, psychologically.

It didn’t last. The units ran through September 2013, then came down for routine maintenance. And this time, there was no straightforward path back. Between them and the grid stood an entirely new regulatory regime.

New Safety Regime

Fukushima didn’t just melt down reactors. It discredited the system that was supposed to prevent exactly that.

Before the accident, nuclear oversight sat with the Nuclear and Industrial Safety Agency—an organization housed inside the Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry. That meant the same ministry responsible for promoting nuclear power was also responsible for regulating it. In the aftermath, that conflict of interest was impossible to defend.

In September 2012, Japan created the Nuclear Regulation Authority (NRA), designed to be independent and modeled on the U.S. Nuclear Regulatory Commission. Structurally, it was moved away from METI and placed under the Ministry of the Environment—an explicit attempt to sever the old ties between promotion and oversight.

Then the NRA rewrote the rules. The new requirements went far beyond what the pre-Fukushima system demanded. Plants had to prove they could withstand not just earthquakes and tsunamis, but a broader menu of risks: volcanic activity, tornadoes, forest fires, and more. They needed stronger emergency response capabilities to survive a complete station blackout. They needed filtered containment venting systems to reduce the risk of hydrogen explosions. And they needed site-specific assessments that forced utilities to defend their assumptions, in public, against worst-case scenarios.

The New Regulatory Requirements incorporate enhanced design to prevent severe accidents from happening again, based on the lessons learned from the Fukushima accident, and cover a wide range of natural phenomena including volcanic activity, tornados, and forest fires.

The government also tightened the rules around plant age. Forty years became the default operating limit. Extensions were still possible, but only in ten-year increments, and with the regulator reviewing and approving each reactor’s aging management plan.

In other words: restarting wasn’t a switch you flipped. It was a multi-year campaign you fought—reactor by reactor.

KEPCO's Reactor-by-Reactor Battle

For KEPCO, compliance turned into a grind measured in years. Each reactor faced its own review, its own engineering modifications, its own hearings, its own approvals. A win at one unit didn’t automatically translate into momentum elsewhere.

Takahama became the proving ground. In June 2014, KEPCO sought approval for Takahama 4. In January 2015, the NRA agreed to handle key safety issues in tandem with the engineering work required to meet the new standards across both units. By November 2015, the NRA approved ten-year license extensions for Takahama 3 and 4.

But the hardest question wasn’t how to restart newer units. It was what to do with the old ones.

Mihama Unit 3 had been operating since December 1976. After Fukushima, it sat idle for a decade beginning in May 2011. KEPCO pursued a restart under the new regime, arguing that the long shutdown period shouldn’t be treated as “operating” time for the purpose of the 40-year limit.

And the precedent-setting decisions kept coming. In October 2024, the NRA approved KEPCO’s plans to continue operating Takahama Nuclear Power Station in Fukui Prefecture, Japan’s oldest nuclear plant, which reached 50 years of operation in November 2024. It was the first time for a plant more than 50 years old to receive approval to operate under the present system.

That decision mattered far beyond Fukui. It sent a message to the entire industry: with the right maintenance and regulatory oversight, Japan was willing to keep aging reactors in service. For a country short on domestic energy—and for a utility trying to rebuild its balance sheet—those extra years could be the difference between decline and recovery.

The Financial Hemorrhage

While regulators rewrote the rulebook, the money kept bleeding out.

In April 2013, the Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry estimated that Japan’s power companies had spent an additional ¥9.2 trillion ($93 billion) on imported fossil fuels since the Fukushima accident. That was the cost of keeping the lights on without nuclear—an enormous outflow to overseas suppliers.

For KEPCO, the prolonged shutdown was a direct hit to creditworthiness. Reserves were drawn down. Borrowing increased. Rates rose, landing on customers already frustrated by a weak economy and the sense that the system had failed them. Bonuses disappeared. Investment programs were cut back. A company that once represented technological confidence now looked, to many observers, like a stressed institution trapped by its own dependencies.

And yet KEPCO kept spending—pouring money into safety upgrades without any guarantee of restart approvals. Management was effectively wagering that nuclear would return, and that when it did, KEPCO’s fleet would be positioned to benefit.

The payoff took longer than anyone wanted. But the direction became clearer after the fuel-price shocks of FY2022: in FY2023 (year ended March 2024), higher nuclear output and lower LNG prices helped drive a recovery, with meaningful improvements in operating profit and free cash flow.

That’s the brutal reality of KEPCO’s post-Fukushima decade. Surviving required patience, persistence, and the stomach to invest through uncertainty. The company bet itself on nuclear’s eventual comeback—and then spent years proving, one reactor at a time, that it deserved permission to operate again.

VI. The Moriyama Scandal: Decades of Corruption Exposed (2019–2020)

The Bombshell Revelation

Just as KEPCO was trying to claw its way back to legitimacy—one restart approval at a time—it got hit from a completely different direction.

On September 27, 2019, President Shigeki Iwane stood in front of the cameras and confirmed what sounded, at first, like something out of a tabloid: twenty executives, including the chairman and the president, had received cash and gifts from a former local official. And it hadn’t been a one-time lapse. The trail ran back more than thirty years.

KEPCO disclosed that twenty officials, mainly in its nuclear power division, received money and gifts worth more than 300 million yen from Eiji Moriyama, the late former deputy mayor of Takahama Town in Fukui Prefecture—home to KEPCO’s Takahama nuclear power plant.

The regulator didn’t mince words. Nuclear Regulation Authority Chairman Toyoshi Fuketa summed up the mood in Tokyo and across the country: “I was first and foremost taken aback and furious, too. Moreover, I was disappointed.” The scandal landed at the worst possible time: when KEPCO needed the public to believe it had changed.

And then came the details. The “gifts” weren’t subtle: Japanese yen and U.S. dollars, gold coins, and vouchers for tailored suits. There were sumo tickets, expensive clothing, and even boxes of cookies with gold coins hidden inside. It was brazen, almost absurd—and that tackiness made it feel even more damning.

The Scope of the Corruption

A third-party investigation later concluded this wasn’t a handful of bad decisions. Beginning in 1987, Moriyama had distributed a total of ¥360 million in cash and gifts to 75 people over more than three decades.

The money, according to the investigation, originated with Yoshida Kaihatsu, a Takahama-based construction company that had received KEPCO contracts related to the nuclear plant. Yoshida Kaihatsu paid Moriyama as a kind of reward, and Moriyama then funneled the money and gifts to KEPCO personnel.

It was the oldest story in infrastructure: local influence, contract steering, and kickbacks—except here it played out around one of the most sensitive assets in the country’s energy system.

The inquiry found that KEPCO officers and employees across functions—not just those handling construction work orders, but also people in the nuclear power department—had been receiving money and goods for roughly thirty years.

In total, investigators identified more than 380 cases where money or gifts were linked to contracts awarded to businesses connected to Moriyama. This wasn’t confined to one rogue pocket of the company. It reached from mid-level managers up to the board.

The Bizarre Dynamics

What made the whole thing even stranger was KEPCO’s own explanation for how it had allowed this to continue.

Several executives claimed they had tried to return Moriyama’s gifts, but that he “stubbornly refused to take back anything and forced the executives to take his gifts.” In other words: they framed themselves as trapped—aware it was improper, but afraid to refuse.

That defense didn’t land well. The obvious rebuttal was that a company like KEPCO is supposed to have systems precisely to prevent this: reporting lines, audits, escalation procedures. “He wouldn’t take it back” is not a compliance program. And the idea that senior executives could be pressured into accepting millions in cash and valuables for decades strained credulity.

The scandal also drew attention to how tightly intertwined the local power structure around Takahama had become. METI had been seconding officials to the Takahama Town office regularly since 2008, and by the time of the scandal, a fourth METI official was on loan there. That same year—2008—coincided with plans to introduce MOX fuel at Takahama, an initiative that would have required delicate local coordination. Whether or not it was directly connected, it reinforced the sense of a dense, overlapping ecosystem of national policy, local politics, and utility operations—the kind of environment where “normal rules” can quietly stop applying.

The Fallout

The consequences were swift at the top, if not simple. Chairman Makoto Yagi resigned in October 2019. In 2020, President Shigeki Iwane resigned as well, and executive vice president Takashi Morimoto took over as the new president. Other implicated executives followed.

METI issued a business improvement order that went straight at the company’s soft underbelly: clarify responsibility for officers and employees, strengthen legal compliance, promote whistleblowing, and rely on an external human resources department to reduce the risk of internal capture.

For KEPCO, the damage wasn’t just reputational. It was strategic. The company had been trying to present itself as the sober, safety-first leader of Japan’s nuclear restart. The Moriyama revelations blew a hole in that story and replaced it with a far more troubling one: an organization where internal controls could be “non-functioning” for decades in exactly the part of the business where public trust mattered most.

For investors, the implication was unavoidable. If bribery and gifts could persist for thirty years and touch senior management, what else might be hiding in the gaps? The governance overhaul that followed—more independent oversight, tighter auditing, stronger whistleblower protections—was necessary. But it also served as an admission: whatever KEPCO had been before, it hadn’t been built to stop this.

VII. Market Liberalization: From Monopoly to Competition (2000–2025)

The Deregulation Journey

If Fukushima was the shock that questioned whether nuclear could run, deregulation was the slow-burn threat that questioned whether the old utility model could survive at all.

Japan didn’t flip a switch from monopoly to competition. It inched there over two decades, and it did it more cautiously—and later—than Europe and North America. The first crack appeared in March 2000, when the biggest electricity users—large factories, department stores, and office towers on “special high voltage” service—were allowed to choose their provider.

The real turning point came on April 1, 2016. For the first time, households and small businesses could also shop around. Electricity retail was fully liberalized. City gas followed in 2017, completing the retail side of the reforms.

Then came the part that actually makes competition possible: the wires. In April 2020, Japan enforced the legal separation of power generation from transmission and distribution. The goal was straightforward: if new retailers were going to compete, they couldn’t be forced to rely on grid infrastructure effectively controlled by their rivals. So the system was reorganized into legally distinct entities—one side for producing and selling electricity, another for moving it.

The Paradox of Competition

On paper, that should have opened the floodgates. And in one sense, it did: hundreds of new retailers showed up, fighting for customers with flashy pricing plans and bundles.

But the market didn’t remix the way reformers hoped. Even after full retail liberalization, the ten regional incumbents—the old monopoly utilities—still held roughly 80% of the market. More than 700 new retailers battled over the remaining slice.

That concentration wasn’t an accident. The incumbents started with two advantages that are hard to overstate: they owned much of the generation, and they owned the customer relationship. Newcomers often had to buy wholesale power—frequently from the very companies they were trying to take share from—then persuade customers to abandon a provider that had delivered reliable service for decades.

And customers mostly didn’t move. Switching came with paperwork, uncertainty, and only modest savings. In a country where many consumers are cautious and institutions are sticky, “a little cheaper” wasn’t always enough to overcome “it already works.”

The Cartel Problem

Then, in 2023, Japan got an uncomfortable answer to a different question: what happens when you introduce competition, but the incumbents don’t actually want to compete?

The government ordered four major utility groups to improve operations after they were found to have formed electricity sales cartels. Kansai Electric was tangled up in the conduct, too—forming cartels with each of the other three utilities involved. The twist is that KEPCO avoided the fine under a leniency program because it reported the cartel before the watchdog’s probe began.

That probe culminated in March 2023, when the Japan Fair Trade Commission imposed record fines totaling ¥101 billion on four electricity-related companies for cartel behavior—essentially coordinating pricing to blunt the very competition deregulation was meant to create.

Even with KEPCO escaping the headline penalty, the episode was a gut check. METI’s monitoring committee concluded that the cartel behavior hindered liberalization and the development of a healthy electricity sector.

And it didn’t stop there. Kansai Electric and Kyushu Electric, along with three other utilities, were hit with separate business improvement orders in April over unauthorized access to customer information belonging to rival retailers. In plain English: incumbents were caught peeking at competitor customer data. It reinforced a growing suspicion that some of the old guard were treating “liberalization” as something to be managed, not embraced.

Japan's Unique Grid Constraints

Even if every utility had behaved perfectly, Japan’s grid makes a truly national electricity market hard to build.

The country’s system has no international interconnections and is divided into four wide-area synchronous grids. Most famously, eastern Japan runs at 50 Hz and western Japan runs at 60 Hz. The two halves can trade power only through HVDC links that convert frequency at the boundary.

There are four of these converter stations, and together they can move only about 1.2 gigawatts between east and west—small relative to the scale of Japan’s demand. The origin story is almost comical in hindsight: in the late 19th century, different regions imported equipment from different countries—Germany’s 50 Hz machines in the east, and U.S. 60 Hz machines in the west. That split never got fixed, because converting an entire nation’s electrical infrastructure would be ruinously expensive. Japan plans to expand the interconnection capacity to 3 gigawatts by 2027, but the underlying division remains.

For KEPCO, this matters every day. Operating in the 60 Hz western grid, it can’t easily send surplus power to Tokyo when its nuclear plants are running hard, and it can’t easily pull large volumes of electricity from TEPCO’s territory when Kansai is tight. The grid structure doesn’t just limit arbitrage. It protects regional dominance.

For investors, deregulation has been a mixed bag. KEPCO faces real pressure where it hurts most—large industrial customers who can shop aggressively—so pricing discipline and service actually matter. But the company still enjoys enormous advantages: deeply entrenched customer relationships, substantial owned generation, and a grid architecture that makes “national competition” far more limited than the reform slogans implied. The cartel and customer-information scandals showed management pushing too far in defending that position. But they also revealed the deeper truth of Japan’s power market: it’s competitive at the edges, yet still built around the incumbents at the core.

VIII. The Nuclear Renaissance & Energy Transition (2020–Present)

KEPCO's Nuclear Leadership

For years after Fukushima, “restart” was a promise. In the 2020s, it finally became reality—and the operational wins started stacking up.

By October 2023, KEPCO had brought Takahama Unit 2 back into full operation. With that, the company reached a milestone that would have sounded implausible a decade earlier: seven reactors successfully resumed operation.

The climate impact was exactly what nuclear advocates had argued all along. As reactors returned, KEPCO’s emissions intensity dropped sharply—from 516 gCO2e/kWh to 330 gCO2e/kWh between 2013 and 2018, with further improvement as more nuclear output came back online.

Just as important, it changed the company’s credibility in the energy transition. KEPCO achieved a 50% CO2 reduction versus its FY2013 targets from domestic power generation projects two years ahead of schedule, driven largely by those seven restarts. That gave management room to set tougher greenhouse gas reduction goals—and to present KEPCO as a serious player in carbon-free power, not just a utility trying to restore the old system.

Nationally, Japan said it still had 33 active nuclear units, with 14 having previously restarted. KEPCO operated seven of those 14—half of the country’s restarted fleet. In practice, that made KEPCO the face of Japan’s nuclear comeback.

Japan's Energy Policy Shift

Then the politics caught up.

On February 18, 2025, the Japanese government approved the 7th Strategic Energy Plan, and the language was a tell: it committed to making the maximum use of nuclear power. That was a major departure from the 2021 plan, which had emphasized reducing dependence on nuclear “as much as possible.”

The numbers reflected the shift. The 7th Basic Energy Plan called for nuclear’s share of electricity generation to rise from 8.5% in fiscal 2023 to around 20% by fiscal 2040.

And the rationale wasn’t just climate. It was load growth—and anxiety about keeping up. With electricity demand expected to rise, including from new data centers powering generative AI services, the government explicitly positioned nuclear as essential: keep existing plants running, use them more, and treat them as a pillar of both decarbonization and energy security.

For KEPCO, this was the policy tailwind it had spent more than a decade trying to earn back. The government wasn’t merely tolerating nuclear again. It was endorsing it.

Building New Reactors — A Historic First

The clearest proof that Japan was moving beyond “restart mode” came in 2025.

On July 22, 2025, Kansai Electric announced plans to move toward building a new nuclear power plant at its Mihama Nuclear Power Station in Fukui Prefecture. The concept: a next-generation advanced light water reactor—still in the pressurized-water family KEPCO knows well, but designed with hardened construction and “core catching” technology intended to improve safety.

These surveys were significant because they marked the first move toward new reactor construction since Fukushima.

KEPCO said it would examine geological and topographical conditions in two areas inside and outside the existing Mihama site through around 2030 to determine whether construction is feasible.

The company also signaled what it viewed as the front-runner technology. “Given overall cost performance, plant operation, and compliance with new regulations, we consider the SRZ-1200 advanced light water reactor the most realistic option,” a KEPCO chief manager said. Mitsubishi Heavy Industries was working with four utilities, including KEPCO and Hokkaido Electric, on the basic design.

This wasn’t just a symbolic milestone. It was a statement that Japan’s nuclear industry—at least in KEPCO’s territory—was prepared to talk about expansion again, not just survival.

Data Centers and the New Demand Drivers

At the same time, a new kind of customer started reshaping the demand curve: hyperscale data centers.

KEPCO formed a joint venture, CyrusOne KEP, which planned to invest at least one trillion yen over the next decade and reach a business scale of 900 MW. Its flagship project, CyrusOne KEP OSK1, was located in the Kansai-area Keihanna Availability Zone—already a major data center hub.

The broader trend is what makes this so consequential. Data center power consumption in Japan could reach 66 TWh by 2034, up from 19 TWh in 2024—tripling in a decade and accounting for a large share of national demand growth.

From KEPCO’s perspective, it’s a near-perfect match. Data centers want electricity that doesn’t blink, 24/7, and they want it low-carbon. That lines up cleanly with what nuclear provides, and it gives KEPCO a growth narrative that isn’t just “bring old plants back,” but “power the next industrial wave.”

Activist Pressure and Shareholder Returns

With nuclear restarting, policy swinging back in its favor, and new load arriving, KEPCO also attracted a different kind of attention: activist capital.

Elliott Investment Management became one of KEPCO’s top three shareholders, taking a stake of between 4% and 5%. Elliott framed its agenda in familiar terms: work with management to strengthen the core business by increasing shareholder returns, unlocking capital from non-core assets, and improving profitability to increase funding flexibility for future growth.

The specifics were blunt. Elliott urged KEPCO to boost dividends and share buybacks by selling ¥150 billion in non-core assets annually. It identified more than ¥2 trillion of non-core assets, including a stake in a construction firm and real estate worth more than ¥1 trillion.

The pressure point was credibility. KEPCO’s dividend history is messy: it was scrapped entirely in 2012, only resumed in 2017, and even after a 20% increase to 60 yen per share, shareholders still weren’t ahead of where they had been before Fukushima.

Elliott’s presence added real tension to KEPCO’s strategy. The fund’s record in Japan—including pushing Tokyo Gas toward buybacks and property sales—suggested it could force meaningful change. But KEPCO wasn’t a typical “return cash” story. Between potential nuclear expansion, data-center investment, and grid modernization, the company also had a credible argument that it needed capital to build the future. The question wasn’t whether KEPCO could create value—it was where that value should go, and how much risk the company should take on to get there.

IX. Myths vs. Reality: Testing the Consensus Narrative

Myth #1: Nuclear Utilities Are Pure Plays on Atomic Energy

Reality: KEPCO may be famous for its reactors, but it doesn’t live on nuclear alone. The group runs a diversified portfolio that includes telecommunications, real estate, and a range of energy services. Management has been explicit about the direction of travel: it’s trying to build a profit mix where non-energy businesses meaningfully share the load, with particular emphasis on expanding areas like Information & Telecommunications and Life/Business Solutions.

That matters because it changes what “a bet on KEPCO” really is. Elliott’s claim that the company holds more than ¥2 trillion in non-core assets is a reminder that a lot of capital sits outside the power plants and fuel contracts. Nuclear may drive the headlines, but the conglomerate structure drives hard questions about capital allocation, management focus, and what valuation multiple the market is willing to pay.

Myth #2: Japan's Deregulated Market Creates Real Competition

Reality: Japan liberalized, but it didn’t fully unseat the incumbents. The ten regional utility groups still control about 80% of the electricity market, while hundreds of new retailers fight over what’s left.

And when the pressure rose, the system showed its true shape. The cartel conduct exposed in 2023 wasn’t a minor footnote; it was evidence that incumbents were willing to coordinate to blunt competitive forces. Layer on top the physical constraints of Japan’s grid—frequency splits and limited interconnection capacity—and the softer constraints, like customer inertia, and you get a market where competition exists, but not evenly.

So yes, KEPCO feels real pressure in pockets of the business, especially where large customers can shop aggressively. But it also operates with structural advantages that deregulation, in practice, has not erased.

Myth #3: Post-Fukushima Governance Reforms Fixed KEPCO

Reality: If Fukushima was the moment Japan demanded change, the Moriyama scandal was the moment it learned how deep the old habits ran. The bribery and gift-giving scheme burst into public view in 2019—eight years after Fukushima—and investigators traced it back more than three decades. That timeline alone undercuts any neat story about “reform completed.”

KEPCO did respond with upgrades that look right on paper: more independent oversight, stronger compliance functions, and improved whistleblower protections. But the core question is cultural, not procedural. A scheme that can persist for thirty years without being truly stopped is, by definition, institutional.

And the reputational damage didn’t end there. The cartel and customer-information incidents that surfaced in 2023 came after the governance overhaul, suggesting that rule-bending behavior still had room to survive even as anti-corruption controls tightened. For investors and observers, the right posture isn’t cynicism—it’s patience and verification. Governance claims only become credible with time and a track record that holds under pressure.

X. Bull Case vs. Bear Case: Strategic Analysis

The Bull Case

Japan is giving nuclear power a second life, and KEPCO is positioned to be one of the biggest beneficiaries.

Nuclear Policy Tailwinds: Japan’s 7th Strategic Energy Plan, approved in February 2025, made something explicit that had been politically difficult to say since 2011: the country intends to increase its use of civilian nuclear power. KEPCO isn’t just along for that ride. It operates seven of the reactors that have restarted nationwide—about half of the total—and it has already begun the first serious, post-Fukushima move toward potential new construction.

Lowest-Cost Generation: Once a nuclear plant is built and its big capital costs are in the rearview mirror, the economics can be compelling. The marginal cost of producing power is typically far below burning LNG or coal. With seven reactors back and precedents forming for life extensions on aging units, KEPCO’s cost position improves as nuclear output rises—and that advantage can persist as long as the fleet stays online.

Data Center Demand: The CyrusOne joint venture, framed as a trillion-yen, decade-long investment plan, gives KEPCO a direct line into one of the most power-hungry growth markets on the planet. Demand growth is expected to concentrate in Tokyo and Kansai, and hyperscalers care about two things KEPCO can increasingly offer: reliable 24/7 supply and lower-carbon electricity. If the data center boom is real, Kansai is one of the places it’s likely to land.

Activist Catalyst: Elliott’s stake adds a financial accelerant. Asset sales, higher dividends, and tighter capital discipline are the standard playbook—and in Japan, that playbook has started to work more often. If KEPCO follows through, the market could re-rate the company as “less legacy utility, more capital allocator,” narrowing the gap with global peers.

Porter's Five Forces Analysis (Bull Interpretation): - Threat of New Entrants: Low. You don’t “enter” nuclear generation casually; it requires licensing, huge capital, and long lead times. KEPCO’s fleet can’t be copied quickly, if at all. - Supplier Power: Moderate. Uranium is globally traded and can be stockpiled, which gives KEPCO more flexibility than utilities that depend on just-in-time LNG cargoes. - Buyer Power: Moderate. Big industrial customers can negotiate hard and have options, but residential switching remains limited. - Threat of Substitutes: Rising as renewables expand, but nuclear still fills a role that intermittent generation can’t fully replace on its own: firm, always-on power. - Competitive Rivalry: Contained. Japan’s market structure and grid constraints still protect regional incumbents more than “full liberalization” implies.

Hamilton Helmer's 7 Powers Framework (Bull Interpretation): - Process Power: There’s a real, hard-to-replicate capability in operating an aging nuclear fleet and getting units through NRA review. KEPCO has accumulated that playbook the hard way. - Switching Costs: For many industrial customers, moving factories or building self-generation isn’t a quick or cheap alternative. - Scale Economies: Nuclear is a fixed-cost machine. The more you run it, the better it looks. Higher utilization creates operating leverage in a way gas-heavy generation often doesn’t.

The Bear Case

The same factors that make the bull case exciting also create the risk: this is a business where the downside often arrives through politics, execution, or a single bad headline.

Execution Risk on New Build: No Japanese utility has built a new reactor in more than a decade. The SRZ-1200 is still a design, not a finished plant, with basic design work aimed at commercialization in the mid-2030s. Globally, nuclear construction has a reputation for cost overruns and schedule slips. Even if KEPCO does everything right, “first new build since Fukushima” is a brutal project to be first on.

Regulatory Uncertainty: Today’s plan supports nuclear, but Japan is a democracy with vivid institutional memory. Public opinion remains divided—one February 2023 survey found a slim majority in favor of restarts, with a large minority opposed. A future government can tighten rules, slow approvals, or change the narrative quickly.

Aging Fleet Challenges: Many of KEPCO’s reactors are past the 40-year mark. Life extension is possible, but it isn’t free. It requires capital spending, ongoing regulatory approvals, and operational excellence. A major technical issue—especially on an older unit—could force early shutdowns and undercut the economic case.

Governance Tail Risk: The Moriyama scandal and later competition issues weren’t small mistakes; they were reminders that misconduct can survive inside large, politically connected institutions. Even after reforms, the risk of another damaging episode can’t be dismissed—and for a nuclear operator, governance failures don’t stay confined to the back page.

Capital Allocation Conflicts: Elliott wants more cash returned to shareholders. Nuclear investment wants the opposite: patience, long horizons, and heavy reinvestment. If management leans too far toward payouts, it risks starving strategic projects. If it leans too far toward building, it risks alienating shareholders who believe KEPCO should first prove it can run cleanly and efficiently.

Porter's Five Forces Analysis (Bear Interpretation): - Threat of Substitutes: Rising. Falling storage costs and improving renewable economics could make renewables-plus-storage more competitive over time, especially for marginal demand growth. - Regulatory/Political Risk: The same tight relationships that historically supported nuclear buildout also created fragility. If politics turns, the pendulum can swing hard.

Hamilton Helmer's 7 Powers Framework (Bear Interpretation): - Counter-Positioning: New models—distributed generation, demand response, and renewables paired with storage—could shift the center of gravity away from large centralized plants over multi-decade horizons, even if that shift is slow and uneven in Japan.

XI. Key Performance Indicators for Ongoing Monitoring

KPI #1: Nuclear Capacity Factor

If you only watched one number to understand KEPCO’s earnings power, it would be this: how much of its nuclear fleet is actually running, and how consistently.

When reactors are online, they’re not just producing electricity. They’re producing margin. Unplanned outages, extended maintenance, or regulatory-driven shutdowns don’t just create operational headaches; they show up immediately in profits.

Watch for: how long scheduled outages last, any unplanned trips, what turns up in NRA inspections, and whether aging equipment starts creating repeat problems at older units.

One near-term signal is already on the table: KEPCO has forecast weaker results for FY 3/2026, citing a lower nuclear capacity factor along with higher corporate and maintenance costs.

KPI #2: Non-Energy Asset Monetization

Elliott’s campaign lives or dies on a simple idea: KEPCO is sitting on a large pool of “non-core” assets, and turning those assets into cash could finance higher shareholder returns.

So the monitoring question becomes: is KEPCO actually selling, how fast, and at what valuations? And once the cash comes in, does it go back to shareholders through buybacks and dividends—or get redirected into new investments and balance-sheet priorities?

Watch for: major real estate sales, divestitures of subsidiaries or strategic stakes, and clear disclosure on where the proceeds are going.

KPI #3: Data Center Revenue/Capacity

KEPCO’s partnership with CyrusOne is the company’s most visible attempt to build a growth engine outside the traditional utility script. It’s also a bet that’s easy to overhype—so it needs to be tracked with the same discipline as a power plant.

The core question: does the joint venture actually translate into built capacity, contracted customers, and durable profits?

Watch for: new facility announcements, progress toward the 900 MW target, utilization rates, customer signings, and whether the venture is profitable once the buildout costs are real.

XII. Material Risks and Overhangs

Regulatory/Legal Risks

KEPCO avoided cartel penalties through a leniency program, but it didn’t avoid the consequences. The episode put the company under a brighter spotlight, and the next violation likely wouldn’t come with an escape hatch.

At the same time, nuclear operations live and die by regulator confidence. KEPCO has to stay in full compliance with the NRA’s post-Fukushima rulebook across every operating unit. A serious safety finding wouldn’t just be a technical problem—it could mean an immediate shutdown and a restart process that drags on for months or years.

Accounting Considerations

Even when a reactor stops generating power, it doesn’t stop costing money.

Nuclear decommissioning obligations sit on the balance sheet as long-dated liabilities, and they can move around materially as assumptions change—discount rates, cost estimates, and regulatory requirements all matter. And for reactors that are no longer operating, impairment risk hangs over the financials. If decommissioning timelines for Mihama Units 1 and 2 and Ohi Units 1 and 2 accelerate, KEPCO could face additional charges.

Nuclear Waste Storage

Spent fuel is the quiet constraint behind the whole nuclear story.

Like other Japanese nuclear operators, KEPCO still faces an unresolved challenge around storage for spent fuel. The company has been seeking a site for interim storage, and the stakes are operational, not theoretical: if interim storage can’t be secured, it can eventually put a ceiling on how long reactors can keep running.

Natural Disaster Exposure

KEPCO’s major nuclear sites sit on the Sea of Japan rather than the Pacific, which helped spare them from Fukushima’s tsunami dynamics. But Japan is still Japan: seismic risk never goes away.

The 2024 Noto Peninsula earthquake was a reminder that this region remains active. In its aftermath, Shika-2 entered in-depth inspections following the January 1, 2024 quake—an example of how quickly a natural event can translate into operational uncertainty for nuclear assets, even beyond KEPCO’s own fleet.

XIII. Conclusion: KEPCO at an Inflection Point

Kansai Electric Power Company is at a true inflection point. This is the utility that, after Fukushima, watched its nuclear fleet go dark and its economics unravel almost overnight. And yet, over the last decade, it fought its way back into position as Japan’s nuclear standard-bearer—bringing seven reactors back online and, in 2025, taking the first concrete step toward a potential new-build since the disaster by launching surveys at Mihama.

A big part of why KEPCO can attempt this comeback is that Japan’s market reforms never fully erased the old advantages. The company still sits atop a powerful home-field position: entrenched customer relationships in one of the country’s most important industrial regions, and a grid structure that remains regionally bounded even in a liberalized era. Add in the country’s renewed focus on energy security and decarbonization, and KEPCO’s restarted nuclear output becomes not just operationally useful, but nationally strategic. The government’s explicit push to make maximum use of nuclear power is the kind of tailwind the company spent years trying to regain.

But the risk profile hasn’t gone away—it’s simply changed shape. The Moriyama scandal showed that KEPCO’s governance failures weren’t theoretical, and not ancient history either; they persisted for decades and reached the top. The cartel and customer-information incidents that surfaced in 2023 showed that even after “reform,” the company could still stumble into behavior that undermines trust. For a nuclear operator, trust isn’t a nice-to-have. It’s permission to operate.

Then there’s execution. New nuclear construction around the world has a habit of slipping schedules and blowing budgets. KEPCO hasn’t built a new reactor in decades, and even its current move is still in the survey-and-feasibility stage, stretching toward 2030. Meanwhile, the existing fleet is aging into an era where life extensions and maintenance excellence become the whole game—and one major technical surprise can swing earnings, politics, and public sentiment at the same time.

Elliott’s stake adds another layer of urgency. Activist pressure could unlock real value through asset sales and higher shareholder returns. But it also creates an unavoidable tension: the more KEPCO tries to fund nuclear upgrades, potential new build, data center growth, and grid investment, the harder it is to run a pure “return capital” playbook. Management has to choose, explain the choice, and then execute without handing critics an opening.

So the right way to approach KEPCO isn’t with a single verdict, but with a framework. This is a company whose outcomes hinge on three things: policy continuity, day-to-day operational performance, and whether governance reforms hold when it matters.

Because Kansai’s industrial heart still beats on KEPCO’s electricity. Whether that power comes from reactors entering their later decades, new advanced designs, or a hybrid future that mixes nuclear with renewables and imported fuels will be decided in regulator hearings, boardrooms, local community halls—and ultimately in the public’s willingness to grant, or withdraw, the social license that nuclear power requires in a country that will never be able to forget what happens when things go wrong.

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music