TEPCO: The Fall and Restructuring of Japan's Energy Giant

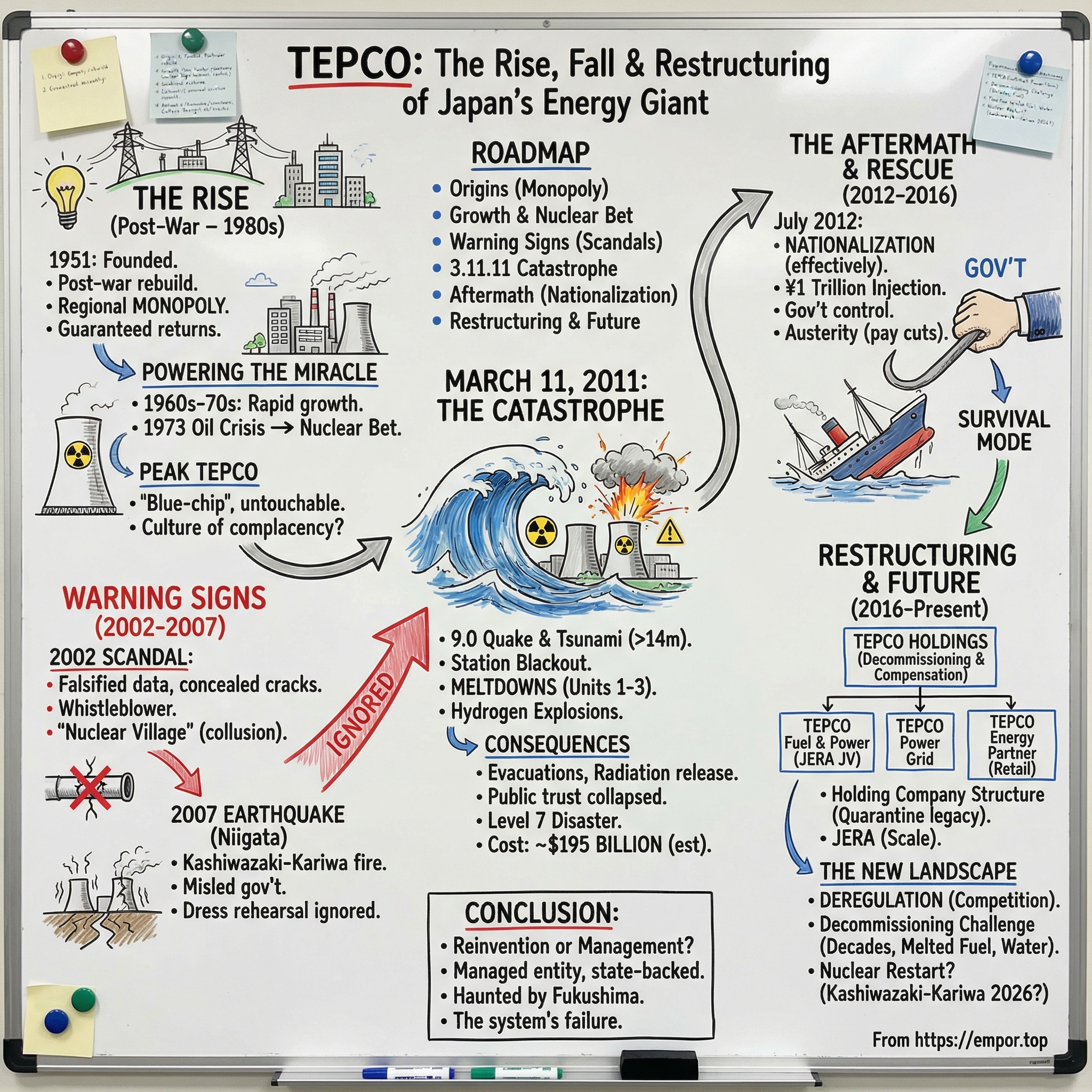

Introduction & Episode Roadmap

Picture this: it’s March 2011. In the gleaming corporate towers of Tokyo, executives at the world’s largest privately owned utility watch their screens with a kind of disbelief that quickly turns to dread. The Kanto Plain—one of the most densely populated regions on Earth—runs on the steady pulse of electricity TEPCO has delivered for generations. But about 250 kilometers to the north, in Fukushima Prefecture, the ocean is rising. A tsunami is racing toward a nuclear power station with six reactors—and toward a company that is about to become a global synonym for crisis.

This is the story of Tokyo Electric Power Company, TEPCO. For decades, it was a model blue-chip: the backbone of Japan’s post-war industrial miracle, the quiet machine that made modern Tokyo possible. And then, in the span of days, it became the operator of the worst nuclear disaster since Chernobyl—triggering a cascade that pulled the company from prestige to effective nationalization, and into a multi-decade cleanup that still defines its present.

TEPCO was founded in 1951, as Japan rebuilt its economy and infrastructure after World War II and the electricity industry returned to private ownership. By March 2010, it supplied power and light to 28.6 million customers and employed around 38,200 people. This wasn’t just another big company. TEPCO was the institution that kept the capital running—the power behind Japan’s political center, its financial markets, its commuter trains, its factories, and its neon skyline.

The central paradox is as stark as it is unsettling: how does the utility that powered Tokyo’s rise become the operator of history’s second-worst nuclear accident?

And the scale of the aftermath is hard to even hold in your head. The cost of decommissioning and decontamination at Fukushima Daiichi has been estimated at $195 billion, including compensation to those affected. One industrial accident—nearing a sum that would stand among the largest corporate losses ever recorded.

Along the way, we’ll run into themes that show up again and again in business history: what monopoly power does to an organization over time; how regulatory capture and cozy oversight can turn risk into routine; what decision-making looks like when the stakes are existential; why governments step in when failure isn’t an option; and whether a company can rebuild credibility when its name becomes inseparable from catastrophe.

We’ll trace TEPCO’s full arc: origins, rise, early warning signs, the day everything changed, the struggle to survive, and the hard reality of competing in a newly deregulated market while carrying the weight of Fukushima.

So let’s start where all utility stories start—with a simple promise: light in the darkness.

The Birth of a Monopoly: Post-War Japan and TEPCO's Origins (1880s–1960s)

On a November evening in 1885, forty incandescent lamps flickered to life inside the Bank of Tokyo. The light came from a Japanese-made portable generator, brought in by a young company called Tokyo Electric Lighting. It was a small demonstration, but it marked a turning point: Japan had entered the electric age.

TEPCO didn’t exist yet—at least not in the corporate form we recognize today. But TEPCO traces its roots back to this moment and this company. And that’s the first important idea to keep in mind with TEPCO: it’s less a single invention than the product of a century of industrial growth, war, state control, and then a carefully designed return to private ownership.

Even in the early days, electricity in Japan was tied to national ambition. In the 1880s, as cities like London and New York built public power stations, Japan’s Meiji government was racing to modernize. It formed an Institute of Technology and invited foreign experts to Tokyo to train Japanese engineers. After the Bank of Tokyo demonstration, regular service began the following year when Tokyo Electric Lighting—capitalized at ¥200,000—was granted a charter to generate and distribute electricity and to sell lighting accessories.

From there, growth came fast. After the Russo-Japanese War of 1904–1905, the government pushed heavy industry, and electricity expanded right alongside it. Utilities multiplied across the country: from just 11 generating and distribution companies in 1892 to 1,752 by 1915. Tokyo Electric Lighting stayed on top, strengthened by access to hydroelectric power from outside the city.

By 1920, Japan had roughly 3,000 power companies riding the wave of an economic boom. The period from 1926 to 1937 became known as the era of the “Big Five” electric power firms. But that competitive landscape wasn’t destined to last—because the country was sliding toward total war, and electricity was too strategic to leave to the market.

In 1939, Japan nationalized the electricity sector as part of its wartime mobilization for the Pacific War. Then, after defeat, the pendulum swung back. In 1951—under the influence of U.S. and Allied occupation authorities—Japan privatized the industry again, reorganizing it around a U.S.-style model: privately owned utilities, but tightly regulated, each granted a regional monopoly.

This is the structure that defined modern Japanese electricity for more than sixty years: nine utilities, each with exclusive rights to generate, transmit, and distribute power within its territory. TEPCO was incorporated in 1951 as the utility for the Kanto region—home to Tokyo and the surrounding prefectures that would become the core of Japan’s post-war economic engine.

The deal—the post-war compact—was simple and incredibly powerful: provide stable supply, charge regulated rates, and earn predictable returns. In exchange, the utility would operate like a quasi-public institution, essential to national rebuilding and trusted to make long-term investments.

In the 1950s, TEPCO’s mission was straightforward: rebuild. Tokyo had been devastated by American firebombing, and the grid was damaged and unreliable. TEPCO restored infrastructure, then pushed into expansion—building fossil-fuel power plants and improving the transmission network to keep pace with Japan’s surging growth.

And here’s the key takeaway for everything that comes later: TEPCO wasn’t built as a normal competitive company. It was built as a nation-building institution—protected by a government-granted monopoly and sustained by guaranteed returns. In the 1950s, that looked like stability and progress. But it also planted incentives that, over time, could make complacency feel rational.

For the moment, though, the story still reads like triumph: a country rebuilding, a metropolis electrifying, and a utility at the center of it all—keeping the lights on, and earning the right to grow bigger bets.

Powering the Japanese Miracle: Growth and the Nuclear Bet (1960s–1980s)

When Kazutaka Kikawada took the helm of TEPCO in 1961, Japan was standing at the starting line of one of the most extraordinary economic expansions in modern history.

Kikawada wasn’t a flashy outsider. He’d joined the predecessor Tokyo Electric Lighting Company back in 1926, studied economics at Tokyo Imperial University, and carried a longstanding interest in issues like unemployment and social welfare. Now he found himself leading TEPCO at the exact moment Prime Minister Hayato Ikeda launched his plan to double national income within a decade—fueling growth through public spending, tax cuts, and lower interest rates.

For TEPCO, it meant one thing: demand. The 1960s in Japan were an era of double-digit economic growth, and electricity consumption surged year after year across the country. Factories ran around the clock making cars and electronics; households bought their first refrigerators and televisions; Tokyo sprawled outward in every direction. TEPCO was no longer just a regional provider. It was becoming a machine that powered the Japanese miracle.

Then the era delivered two problems that would define the company’s strategy for decades.

The first was pollution. Tokyo’s air thickened with smog; waterways darkened with industrial waste. TEPCO started responding by expanding its network of LNG-fueled power plants—an early move toward a cleaner-burning fossil fuel compared to coal or oil.

The second challenge hit harder: oil.

Japan was slammed by the 1973 oil crisis. The country imported about 90% of its oil from the Middle East, and suddenly it faced the unthinkable: a stockpile good for only 55 days, with another supply ship that hadn’t arrived yet. The government moved quickly, ordering cuts in industrial oil and electricity consumption, then escalating to deeper reductions for major industries and even restrictions on leisure driving. It was widely seen as Japan’s most serious crisis since 1945.

The shock forced a strategic re-think. Before the crisis, oil accounted for more than 80% of Japan’s total energy consumption. When prices spiked and supply risk became painfully real, Japan responded by diversifying suppliers beyond the Middle East, pushing conservation, funding relationships in the Arab world—and, most importantly, making a national bet on nuclear power.

For a resource-poor island nation, nuclear looked like the closest thing to an energy cheat code: global uranium supplies, huge output from small fuel volumes, and less exposure to geopolitics.

Japan’s first nuclear reactor was commissioned in 1966. Over the decades that followed, dozens more came online. Nuclear’s share of total electricity production rose from about 2% in 1973 to roughly 30% by March 2011.

TEPCO became the face of that ambition. In March 1971, the first unit at Fukushima Daiichi began operating. The site ultimately comprised six boiling-water reactors built between 1971 and 1979—designed, constructed, and operated in collaboration with General Electric, with Toshiba and Hitachi also supplying equipment. With a combined output of 4.7 GWe, Fukushima Daiichi ranked among the world’s largest nuclear power stations.

At the time of the 2011 accident, only reactors 1 through 3 were operating. But the more important detail, for understanding what comes later, is hidden in the design lineage: these were GE boiling water reactors of an early 1960s design, using what’s known as Mark I containment. Reactors 1 through 3 entered commercial operation between 1971 and 1975. In other words, even when they were new, they reflected the engineering assumptions of a prior decade.

And TEPCO’s ambition in this period wasn’t limited to generation. In 1986, as Japan began liberalizing telecommunications, TEPCO leveraged its experience running sophisticated grid communications to form Tokyo Telecommunications Network Company, Inc. (TTNet) and build an optical fiber digital network. That led into mobile communications and, by 1989, a TEPCO cable television system. It was a glimpse of TEPCO imagining itself as more than a utility—an infrastructure conglomerate, with networks as its core competency.

By the late 1980s, TEPCO looked untouchable: a protected regional monopoly with guaranteed returns, nuclear plants that promised energy security, and a foothold in the hottest new communications markets. Its stock was as blue-chip as they come, owned by banks, insurance companies, and even the Tokyo Metropolitan Government.

But underneath that stability, the incentives were quietly bending the culture in a dangerous direction. A monopoly insulated from competition. Cost-plus pricing that softened the pain of inefficiency. And a regulator-operator relationship so close that “compliance” could become something you managed, not something you lived.

The warning signs were there. Soon, they would become impossible to ignore.

The Culture of Concealment: 2002 Safety Data Scandal

In the summer of 2002, Japan’s nuclear establishment got the kind of shock that, on paper, should have reset the entire system. It didn’t. And nine years later, that failure would matter in the most brutal way imaginable.

The scandal broke in August 2002, when the Japanese government disclosed that TEPCO had been falsifying routine nuclear inspection records and concealing safety incidents. TEPCO initially acknowledged 29 cases. Then the number kept climbing. Ultimately, the company admitted it had submitted false technical data roughly 200 times over a span of more than two decades, from 1977 to 2002.

What it was hiding wasn’t cosmetic. According to the Nuclear and Industrial Safety Agency (NISA), TEPCO had tried to cover up cracks in reactor vessel shrouds in 13 units—spanning all six reactors at Fukushima Daiichi, all four at Fukushima Daini, and all seven at Kashiwazaki-Kariwa. In September 2002, TEPCO also admitted it had concealed data on cracks in critical circulation piping. These are the recirculation pipes that help move heat out of the reactor. If they fracture, you’re suddenly looking at a serious accident scenario: coolant leakage, compromised cooling, and the kind of chain reaction every operator trains to prevent.

Then came the detail that made the whole episode feel even more damning: the information didn’t surface because the system caught it. It surfaced because an outsider did. The whistleblower was at GE—the very company that helped build the plants and had worked with TEPCO for decades.

And here’s where the story gets darker.

In 2000, whistleblowers had already alerted NISA that TEPCO was faking inspections and even editing documents and video footage. But instead of functioning like a wall between the public and the company, the oversight process behaved like a conduit. NISA disclosed the whistleblowers’ identities to the licensee—TEPCO.

That’s not just a bureaucratic mistake. It’s a signal to everyone watching: don’t do this again.

The immediate consequences looked dramatic. All seventeen of TEPCO’s boiling-water reactors were shut down for inspection. The chairman, president, vice-president, and two advisers resigned. A new president promised sweeping reforms and vowed to restore public trust.

And then, as so often happens in corporate scandals, the system inhaled… and went back to work. By the end of 2005, with government approval, generation restarted at all the suspended plants.

If this were truly a turning point, the story would end there. It didn’t.

In March 2007—just a little over a year later—TEPCO announced that an internal investigation had uncovered a large number of additional unreported incidents that hadn’t surfaced in 2002. They included an unexpected unit criticality in 1978 and more systematic false reporting. Once again, the company apologized. “We apologise from the bottom of our heart for causing anxiety to the public and local residents,” TEPCO vice president Katsutoshi Chikudate said.

So why did nothing fundamentally change?

To answer that, you have to understand Japan’s “nuclear village” (原子力ムラ). The term became famous after Fukushima, but it described a long-standing reality: a tight network of utilities, regulators, politicians, and vendors that collectively benefited from nuclear expansion—and treated nuclear safety as something to be managed inside the club.

NISA, the agency charged with oversight, sat within the Ministry of Trade, Economy and Industry—the same bureaucracy responsible for promoting nuclear power. Over the course of careers, officials rotated through both promotion and oversight roles, blurring the difference between championing the industry and policing it. And in the background was amakudari—“descent from heaven”—the practice of senior bureaucrats leaving government for high-ranking positions in the industries they once regulated.

Amakudari wasn’t an abstract concept here. According to data compiled by the Communist Party, senior officials from the ministry repeatedly landed positions at Japan’s utilities. At TEPCO, between 1959 and 2010, four former top-ranking ministry officials served successively as vice presidents. When one retired, another former colleague from the ministry took over what was effectively treated as a “reserved seat.”

This wasn’t just a revolving door. It was a system of incentives that quietly trained everyone—regulators and executives alike—to avoid confrontations that could disrupt the industry’s momentum. Later investigations into Fukushima would describe a “network of corruption, collusion, and nepotism,” and point to these cozy ties as a central reason robust safety oversight failed.

For anyone studying corporate governance, the 2002 scandal reads like a case study in how disasters incubate: monopoly protection, guaranteed returns, low competitive pressure, and a regulator structurally aligned with the industry’s success. TEPCO didn’t face a market discipline that would punish corner-cutting. The oversight body didn’t behave like an adversary. And the broader political ecosystem wasn’t built to force a hard reckoning.

The 2002 scandal should have been the wake-up call. It wasn’t.

But another warning was coming—one delivered not in memos or inspection reports, but in seismic waves.

The 2007 Earthquake: A Dress Rehearsal Ignored

On July 16, 2007, a magnitude 6.8 earthquake struck offshore from Niigata Prefecture and rattled the world’s largest nuclear power complex: TEPCO’s Kashiwazaki-Kariwa plant. For anyone paying attention, this should have been the moment the system finally took the hint. Instead, it became another warning filed away—right up until the day the filing cabinet caught fire.

TEPCO was forced to shut Kashiwazaki-Kariwa after the Niigata-Chuetsu-Oki earthquake. That year, it posted its first loss in 28 years. The losses continued until the plant returned to operation in 2009.

The earthquake did real, visible damage. The main structure subsided, water pipes ruptured, and a fire broke out that took five hours to put out. There were also small releases of radioactive material into the air and the sea. Most importantly, the quake exceeded the plant’s design basis—it was stronger than what the facility had been built to endure.

And then came the familiar part: the messaging.

The Australian reported on July 25, 2007 that, about 12 hours after the quake triggered a chain of problems at the plant, a senior government official summoned TEPCO’s president for what it called a “rare and humiliating verbal caning.” The official was “furious,” the paper wrote, because TEPCO management had “initially misled his officials — and not for the first time, either — about the extent of breakdowns at Kashiwazaki-Kariwa.”

It was the 2002 scandal playing on repeat, but now in the middle of a live event: the instinct to minimize, to deflect, and to delay.

The business impact was brutal. Kashiwazaki-Kariwa had seven reactors—an enormous chunk of TEPCO’s generating capacity. With it offline, TEPCO had to buy pricier electricity and restart idle thermal plants burning expensive oil and gas. The company didn’t claw its way back until the gradual reopening in 2009.

But the bigger question isn’t what the earthquake did to earnings. It’s what it failed to do to behavior.

Why didn’t 2007 trigger a sweeping, adversarial review of TEPCO’s other nuclear sites? Why didn’t it force a hard look at Fukushima Daiichi—especially its tsunami exposure?

Internally, the risk was not some unknowable black swan. A simulation in 2006 concluded that a 13.5-meter wave could cause a complete loss of all power and make it impossible to inject water into reactor No. 5. The estimated cost to protect the plant against such an event was about $25 million. In 2008, TEPCO calculated the effects of a 10-meter tsunami as well. In both cases, TEPCO failed to act on what it learned. The sessions were treated as training for junior employees, and the company did not truly expect tsunamis that large.

That is the heart of the story: they had the numbers, but not the belief.

In the years before the accident, NISA—at least in theory—could have pushed TEPCO to significantly strengthen Fukushima Daiichi. The agency was already scrutinizing Unit 1 as part of TEPCO’s request to extend its operating life. Just weeks before the disaster, NISA approved Unit 1 to run for an additional ten years.

So the lesson of 2007—the proof that reality can exceed the blueprint—never got translated into action where it mattered most. Kashiwazaki-Kariwa was supposed to be the wake-up call. Instead, it was the dress rehearsal.

March 11, 2011: The Day Everything Changed

At 2:46 p.m. on Friday, March 11, 2011, Japan was hit by a magnitude 9.0 earthquake—one of the most powerful ever recorded. The epicenter was about 70 kilometers east of the Oshika Peninsula, beneath the Pacific. The ground shook for roughly six minutes.

At Fukushima Daiichi, the three operating reactors—Units 1, 2, and 3—did what they were designed to do. They automatically shut down. Control rods inserted, fission stopped, and for a brief moment it looked like TEPCO had dodged the worst.

But the earthquake also knocked out the plant’s connection to the power grid. That mattered because a nuclear reactor doesn’t stop being hot when it stops fissioning. The fuel keeps generating intense decay heat, and that heat has to be removed continuously. With external power gone, the backup diesel generators kicked in to run the cooling systems.

Then the ocean arrived.

The first tsunami wave reached Fukushima Daiichi about 41 minutes after the quake. A second, larger wave followed roughly 9 to 10 minutes later.

The tsunami that struck the site exceeded 14 meters. Fukushima Daiichi’s seawall had been designed for waves around 5.7 meters. Water poured over the barrier, flooded the grounds, and surged into buildings. The diesel generators—placed in low, vulnerable locations—were inundated. Within minutes, the plant entered a “station blackout”: a total loss of AC power.

From there, the accident became a countdown.

With cooling systems crippled, water levels in the reactor pressure vessels began to fall as water boiled into steam. Fuel rods became exposed. Temperatures soared—high enough to damage the zirconium cladding around the fuel. And when superheated zirconium reacts with steam, it produces hydrogen gas.

The plant was now trapped in the nightmare scenario engineers fear: reactors that are shut down, but not cooled.

All core cooling systems were lost after the tsunami. Units 1 to 3 suffered core melts. Hydrogen accumulated, and multiple hydrogen explosions tore through the site. Massive amounts of radioactive material were released into the air, soil, and sea. Unit 4’s reactor building was also destroyed by a hydrogen explosion—especially alarming because Unit 4 was shut down for maintenance, and its spent fuel pool held 1,535 fuel assemblies.

About 16 hours after the earthquake and SCRAM, Unit 1’s fuel had “mostly melted and fallen into a lump at the bottom of the pressure vessel”—a condition TEPCO officials described as a meltdown.

And in the middle of this, TEPCO’s decision-making broke down in a way that would become its defining indictment.

The company considered using seawater to cool a reactor as early as Saturday morning. But it didn’t move ahead until that evening, after the prime minister ordered it in the wake of an explosion. TEPCO hesitated because seawater can permanently ruin a reactor—turning a multi-billion-dollar asset into scrap. Seawater is corrosive; it’s the option of last resort. But by the time this choice was on the table, “saving the reactor” was already a fantasy. The real objective was preventing further catastrophe.

The explosions made the crisis visible to the world. On March 12, Unit 1’s reactor building blew apart after hydrogen vented into the upper portion of the building and ignited. On March 14, Unit 3 suffered a similar hydrogen explosion. On March 15, Unit 4 was damaged as well.

The human consequences spread fast. Around Fukushima, roughly 50,000 households were displaced from the evacuation zone. Radiation releases from Units 1 to 4 forced the evacuation of 83,000 residents from nearby towns. And the evacuation itself—happening amid the chaos of an earthquake and tsunami—produced additional casualties, particularly among elderly hospital patients and nursing home residents.

In those early weeks, public trust collapsed alongside the plant. Many in Japan felt that TEPCO and the government provided limited information about what was happening and what it meant. Layperson-friendly expert explanation often came not from official channels, but from Masashi Gotō, a retired Toshiba reactor vessel designer. TEPCO’s instinct for opacity—hardened over decades of minimizing and concealing smaller incidents—became toxic when people needed clear guidance about radiation risk.

In mid-December 2011, TEPCO declared a “cold shutdown condition,” with radioactive releases reduced to minimal levels. Nine months after the disaster began, the immediate emergency was finally stabilized. But nothing was solved. The hardest work—decommissioning, decontamination, and compensation—was only beginning.

Multiple investigations later concluded that Fukushima was not simply a natural disaster. It was a man-made catastrophe rooted in regulatory capture—what critics described as a “network of corruption, collusion, and nepotism.” Reporting would highlight amakudari, “descent from heaven,” in which senior regulators took lucrative jobs at the very companies they had overseen, reinforcing a system that consistently sided with the industry it was supposed to police.

The accident was rated Level 7—the maximum—on the International Nuclear Event Scale, the same rating as Chernobyl.

And perhaps the most damning comparison came from nearby. The Onagawa Nuclear Power Plant, closer to the earthquake’s epicenter, had a 14-meter seawall and successfully withstood the tsunami, avoiding serious damage and radioactive release. The contrast didn’t prove Fukushima was preventable in every detail—but it did underscore the central truth TEPCO could never escape: this wasn’t inevitable. It was the consequence of decisions made, deferred, and defended over decades.

The Aftermath: Nationalization and Survival

By the summer of 2012, TEPCO was still standing—but barely. In less than eighteen months, the world’s largest privately owned utility had gone from blue-chip stability to a balance sheet buckling under compensation claims, cleanup obligations, and the loss of the nuclear fleet that had once anchored its economics.

The question facing Japan wasn’t whether TEPCO deserved saving. It was what would happen if it wasn’t.

In July 2012, the Japanese government provided TEPCO with ¥1 trillion (about US$12 billion) to keep the company from collapsing—so it could continue supplying electricity to Tokyo and surrounding municipalities, and so it could fund the decommissioning of Fukushima Daiichi.

On July 31, 2012, the bailout effectively became nationalization. TEPCO received a ¥1 trillion capital injection from the Nuclear Damage Liability Facilitation Fund (now the Nuclear Damage Compensation and Decommissioning Facilitation Corporation), a government-backed entity created for exactly this kind of crisis. In return, the Fund became TEPCO’s controlling shareholder, holding 50.11% of voting rights, with the option to raise that stake as high as 88.69% by converting preferred shares into common stock.

Trade minister Yukio Edano was blunt about the logic: “Without state funds, Tepco cannot provide a stable supply of electricity and pay for compensation and decommissioning costs.” At the same time, he signaled the government’s intent wasn’t permanent ownership. Even under “so-called state control,” he said, he wanted TEPCO to “step out of this situation soon,” once it had met its obligations and returned to profitability.

But the obligations were staggering. In May 2012, the total cost of the disaster was estimated at $100 billion—an early figure that would grow substantially. The cost of decommissioning and decontamination has since been estimated at $195 billion. That total includes an estimated $71 billion to decommission the Fukushima Daiichi reactors. TEPCO was expected to shoulder $143 billion of the decommissioning and decontamination, while Japan’s Ministry of Finance would provide $17 billion.

Even without comparisons, those numbers land like a blunt object. This was a single-event liability so large it threatened to overwhelm the company that caused it—and to spill into the national economy if the state didn’t contain it.

The rescue also came with austerity. In July 2012, TEPCO announced that managers’ annual salaries would be cut by at least 30%, and workers’ pay cuts would remain at 20%. On average, employee pay would fall by 23.68%. TEPCO also reduced the portion of employee health insurance it covered, from 60% to 50%.

And for shareholders, the story was even harsher. TEPCO stock, once treated as one of Japan’s safest holdings—a regulated monopoly with predictable returns—was gutted. Life insurers that had held the shares as conservative, long-duration assets saw their investment thesis collapse along with the price. Investors who had trusted TEPCO as a bedrock holding watched its value evaporate.

The government support didn’t stop with that first injection. By the end of February 2016, TEPCO had received at least 5.7609 trillion yen in state support since the tsunami.

Why not just let TEPCO fail?

Because failure wasn’t a clean option. Someone still had to deliver reliable power to the Tokyo region. And someone had to run a decommissioning and compensation effort measured not in quarters, but in decades. A chaotic bankruptcy would have risked destabilizing electricity supply and throwing Fukushima’s cleanup into legal and operational limbo at the very moment Japan needed clarity and coordination.

Nationalization kept TEPCO alive as an operating entity. It also made the new reality unmistakable: TEPCO would now have to run a utility business under public scrutiny and state control, while simultaneously carrying out what would become the most complex nuclear decommissioning project ever attempted.

Restructuring: The Holding Company Era (2016–Present)

By 2016, TEPCO had a problem that was as much organizational as it was financial: one company was trying to be two things at once. It had to run a day-to-day utility that kept Tokyo humming, while also carrying an open-ended national responsibility—compensation, cleanup, and the decommissioning of Fukushima Daiichi—that would last decades.

So on April 1, 2016, TEPCO reorganized itself into a holding company structure designed to separate those realities.

Under the new setup, the nuclear and decommissioning mission stayed at the center, inside Tokyo Electric Power Company Holdings. Everything else—the parts that had to compete, cut costs, and win customers—was pushed into operating subsidiaries. Fuel and thermal generation became TEPCO Fuel and Power Incorporated. Transmission and distribution became TEPCO Power Grid Incorporated. Retail electricity became TEPCO Energy Partner Incorporated.

TEPCO was explicit about what this structure was meant to do. The holding company, it said, would take responsibility for “compensation, decommissioning and revitalization related to the Fukushima nuclear accident,” while the wider group would “establish a sustainable revenue base for corporate revival” and fulfill its responsibilities stemming from the accident.

In plain terms: quarantine the toxic legacy, and give the functioning businesses room to breathe.

This wasn’t the first step in that direction. In 2014, TEPCO had already split itself into two major tracks: a power generation business and a dedicated decommissioning division focused on Fukushima Daiichi. The government’s goal was clear—reduce its direct involvement over time, get the revenue-generating side back on stable footing, and eventually sell down its stake in a restructured TEPCO.

If the holding company was about governance and liability, the most consequential strategic move was about scale.

TEPCO and Chubu Electric created a joint venture called JERA to develop new power plants together, consolidate fuel purchasing, and supply power across regions. JERA became fully operational in 2019, combining the fossil-fuel generation and fuel procurement operations of Japan’s two largest utilities. In a country where nuclear restarts remained uncertain after Fukushima, thermal power wasn’t a bridge—it was the core. Pooling that core gave the combined business more leverage in fuel buying and more operational heft than either company could achieve alone.

This is what TEPCO’s post-Fukushima reality looked like: it wasn’t rebuilding the old TEPCO. It was assembling a new structure around the parts that could still win in a market, while keeping the Fukushima obligation anchored at the top.

Financially, TEPCO did manage to get back to something that looked like normal business performance—at least on paper. In fiscal year 2023, TEPCO Holdings reported operating revenue of around 6.9 trillion yen. In fiscal year 2024, net sales fell year-on-year to about 6.81 trillion yen, mainly due to lower fuel-price adjustment amounts as fuel prices declined. It also posted net income attributable to owners of the parent of 161.2 billion yen—modest profitability, but notable given the continuing decommissioning burden.

And then, in late December 2025, came news that would have sounded unthinkable in the years immediately after Fukushima: TEPCO planned to restart nuclear operations.

TEPCO said it aimed to reactivate its long-idled No. 6 reactor at the Kashiwazaki-Kariwa nuclear power plant on January 20, 2026, targeting normal operations by February 26. Japanese authorities had approved the restart of the world’s biggest nuclear power plant, dormant for more than a decade after Fukushima, as Japan looked to shift its energy supply away from fossil fuels. The Niigata prefectural assembly, despite deep unease among many residents, approved a bill clearing the way for TEPCO to restart one of the plant’s seven reactors.

Restarting the two Kashiwazaki-Kariwa units—offline for periodic inspections since August 2011 and March 2012—was expected to lift TEPCO’s earnings by an estimated 100 billion yen per year.

The significance wasn’t just financial. Nearly fifteen years after the disaster, the company that had become synonymous with nuclear failure was being allowed back into nuclear generation. Not because the past had been forgotten, but because Japan’s energy needs—and the economics of running a modern grid—were forcing hard choices.

The Decommissioning Challenge: A Multi-Decade Project

While TEPCO’s operating subsidiaries tried to compete in a newly opened market, the holding company was stuck with a job unlike anything else in corporate history: take apart three melted nuclear reactors—safely—without making the surrounding environment any worse.

Inside Units 1 through 3 sits the problem at the center of everything: about 880 tonnes of highly radioactive melted fuel. Thirteen years after the accident, in 2024, attempts to remove that material were halted. This “fuel debris”—a fused mix of nuclear fuel, cladding, and structural components—didn’t melt into neat, removable blocks. It hardened into unpredictable shapes, in places that are still not fully mapped or understood.

And yet progress, when it comes, arrives in almost absurdly small increments. In November 2024, TEPCO moved a tiny piece of melted fuel from a Fukushima reactor for radiation testing—a key step in the decommissioning process. The sample was only a few grams, but it mattered because it represented the first fuel debris actually removed from the reactor. Scientists would analyze it to learn what they’re dealing with—information that will shape the tools and methods needed to eventually tackle the remaining hundreds of tonnes.

Then there’s the water—an entirely different crisis, running in parallel.

Over the past decade, more than 1.24 million tons of tritium-contaminated water accumulated on site, filling more than 1,000 tanks and consuming nearly every usable corner of the Fukushima Daiichi grounds. In April 2021, the Japanese government approved a plan to discharge treated water—processed to remove radionuclides other than tritium—into the Pacific Ocean over the course of 30 years. The discharge began in 2023, and officials projected the overall effort could stretch across roughly 40 years.

That decision set off protests from neighboring countries and environmental groups. At the same time, international scientific bodies generally concluded that, once diluted, the tritium would pose minimal health risk. Even if the science was on the government’s side, the politics—and the trust deficit—were not.

TEPCO also tried to choke off the problem at its source: the constant inflow of groundwater that becomes contaminated when it mixes with the damaged site. It spent ¥34.5 billion (about US$324 million) on a 1.5-kilometer underground wall of frozen soil built by Kajima Corporation. The concept was dramatic: insert about 1,500 supercooled pipes, each roughly 30 meters long, into the ground and freeze the earth into a barrier. In practice, the wall ultimately failed to significantly reduce the groundwater flowing into the site.

All of this adds up to a simple reality: there is no playbook. Decommissioning Fukushima Daiichi demands capabilities that have to be invented or adapted in real time—robots that can function under extreme radiation, remote systems to handle materials no human can approach, and waste disposal solutions for categories of debris that existing facilities were never designed to accept.

Officially, the cleanup was described in 2013 and 2014 as a decades-long job costing tens of billions of dollars, with a 30-to-40-year timeline. TEPCO and the government continued to describe decommissioning as a 30–40 year project. But independent estimates were far less comforting. In March 2017, JCER estimated that the final cost of disposal after the accident could potentially balloon to nearly 70 trillion yen. In a later recalculation based on limited information from stakeholder hearings, it warned there was a risk the cost could exceed 80 trillion yen, driven in part by the growing contaminated-water burden.

For investors, the cleanup is both risk and certainty at the same time. The risk is obvious: costs can keep rising, and the history of Fukushima suggests they will. The certainty is structural: TEPCO—backed by the Japanese state—will keep operating and generating revenue while the work continues, because Japan cannot allow the company responsible for Fukushima Daiichi to fail while Fukushima Daiichi still requires decades of attention.

The New Competitive Landscape: Deregulation and the Future

The electricity market TEPCO operates in today barely resembles the old, pre-2011 world. Fukushima didn’t just damage reactors and balance sheets; it shattered the political consensus that regional monopolies should run Japan’s power system with minimal competitive pressure.

In the years after the accident, Japan launched a sweeping electricity system reform aimed at preventing supply crunches and reducing dependence on any one utility’s fleet. The headline changes were simple, and seismic: full liberalization of electricity retailing in 2016, followed by legal unbundling of transmission and distribution in 2020.

For TEPCO, retail liberalization was the psychological break. In 2016—and then with city gas in 2017—deregulation reached the consumer. For the first time, households and businesses in TEPCO’s traditional territory could shop for their provider. New entrants poured in, from gas companies and telecom players to stand-alone energy retailers offering discounts, bundles, and plans designed to make electricity feel less like a utility bill and more like a subscription.

This was the part TEPCO had never had to practice. For decades, the company’s job was to deliver stable supply inside a protected region and earn regulated returns on a captive base. Now it had to compete—on price, on service, and on trust—while still carrying Fukushima’s costs in the background.

And the competitive landscape sits on top of a grid with quirks that make Japan unusually hard to run as one unified system. The country is split into two incompatible frequency zones: eastern Japan, including TEPCO’s area, runs at 50 Hz, while western Japan runs at 60 Hz. That split dates back to the late 19th century, when different regions imported generation equipment from Germany and the United States—and then built their networks around it. The result is a structurally divided national grid with only limited ability to transfer power across the boundary.

That matters most in a crisis. After Fukushima, when eastern Japan suddenly faced tight supply, western Japan couldn’t simply surge electricity eastward at scale. The frequency divide turned what should have been a national balancing problem into a regional constraint—one more reminder that electricity is local until it isn’t.

Against that backdrop, TEPCO’s strategy has had to evolve along two tracks at once: compete in a deregulated market and reshape its generation profile. TEPCO has said it will maintain and expand its renewable mix by upgrading small and aging hydroelectric generators. And for years after Fukushima, the company had no nuclear power stations in operation—an extraordinary reversal for a utility that once relied heavily on nuclear generation and then had to rebuild around thermal power and renewables.

TEPCO has also been investing in renewables more directly, committing around ¥1 trillion (about $7.5 billion) over the next five years to expand its green energy portfolio, with a goal of reaching a 30% renewable share by 2030. In its 2024 Integrated Report, TEPCO frames the roadmap in the language of a company trying to do three things at once: deliver on Fukushima responsibilities, push toward carbon neutrality, and strengthen the underlying business foundation that has to survive in a market that no longer guarantees anyone a customer.

Strategic Analysis: TEPCO Through the Lens of Competitive Strategy

To understand TEPCO now, you have to hold two truths at once. This used to be the cleanest kind of business: a government-granted regional monopoly with predictable returns. Today it’s something far stranger—a utility competing in a partially deregulated market, while carrying the financial and reputational gravity of the world’s second-worst nuclear accident.

Porter’s Five Forces is a good way to see just how much the ground shifted under its feet.

Porter's Five Forces Analysis:

Threat of New Entrants: Before 2011, this was effectively zero. TEPCO didn’t just have scale—it had the law. Today, after deregulation, the threat is meaningfully higher, especially in retail. New providers can enter without building power plants or stringing wires across Kanto. But the hard parts of the system—generation assets and grid infrastructure—still demand enormous capital, and access to the network runs through regulated transmission operators like TEPCO Power Grid. So entrants can show up, but they can’t easily become a “new TEPCO.”

Supplier Power: TEPCO’s supply chain is, in many ways, Japan’s national constraint: imported fuel. LNG, coal, and uranium are all purchased in global markets, and Japan is heavily dependent on imports for energy. That keeps supplier power moderate to high—especially when prices spike or geopolitics tighten. TEPCO’s answer here was scale: the JERA joint venture was built to consolidate fuel procurement and increase leverage with suppliers. It helps, but it doesn’t change the underlying reality that Japan can’t “domestically source” its way out of exposure.

Buyer Power: In the monopoly era, buyer power didn’t exist. Customers couldn’t negotiate; they could only pay. In the liberalized market, large industrial customers can shop around and do, which gives them meaningful bargaining leverage. Residential customers now have choice in theory, but in practice face switching friction and the usual information gaps. Buyer power is higher across the board—but it’s strongest at the top end of the customer base.

Threat of Substitutes: Rising. Rooftop solar, battery storage, and efficiency improvements let customers reduce how much they need from the grid. And Japan’s carbon-neutral push can accelerate that trend. The substitute isn’t “no electricity.” It’s less dependence on the incumbent utility for each incremental kilowatt-hour.

Competitive Rivalry: For most of TEPCO’s modern history, rivalry was basically a non-concept inside its own region. Now, retail is crowded. TEPCO faces other regional utilities moving into its territory, new entrants bundling power with telecom or gas, and companies positioning themselves as cleaner or cheaper alternatives. The fight isn’t over who can generate electricity. It’s over who owns the customer relationship.

If Porter’s framework explains how the arena changed, Hamilton Helmer’s 7 Powers helps explain what durable advantages TEPCO might still have—or have lost.

Hamilton Helmer's 7 Powers Framework:

TEPCO's competitive position through Helmer's lens reveals a company in transition:

Scale Economies: TEPCO still has scale in the places where scale matters: operating a massive system and coordinating generation and delivery at metropolitan intensity. JERA extends that advantage into fuel procurement and thermal generation.

Network Effects: Traditional utilities don’t get classic network effects. But there’s a modern version lurking here: data. If smart grid investments translate into better forecasting, smoother balancing, and new customer-facing services, TEPCO could build a data-driven advantage. That’s a big “if,” and it’s not automatic.

Counter-Positioning: TEPCO’s Fukushima burden creates a strange kind of moat. No competitor wants its liabilities—but TEPCO also has something competitors don’t: government backing and an implicit guarantee of survival. That doesn’t make TEPCO admirable. It makes it hard to dislodge.

Switching Costs: Lower than they used to be, but not zero. Large industrial customers often have customized arrangements and operational dependencies that can make switching non-trivial. For households, the costs are more psychological and procedural—but they still slow churn.

Branding: A liability. The TEPCO name is inseparable from Fukushima for many consumers, especially the environmentally conscious. In branding terms, this isn’t “weak.” It’s negative.

Cornered Resource: The grid. TEPCO’s transmission and distribution infrastructure is a physical asset competitors can’t realistically replicate. Even in a liberalized market, that network remains foundational—and regulated.

Process Power: TEPCO has decades of experience operating complex power systems. The open question is whether that operational excellence becomes an edge in a competitive, customer-driven market—or whether it stays trapped in the old utility mindset.

Critical KPIs for Investors:

If you’re watching TEPCO as an ongoing enterprise, three indicators matter more than almost anything else:

-

Nuclear Restart Timeline and Capacity Utilization: Kashiwazaki-Kariwa is the near-term swing factor. TEPCO has said restarting reactors there would materially lift earnings. The timeline—and the ability to actually run at meaningful utilization once restarted—is the difference between incremental recovery and real profitability.

-

Decommissioning Cost Evolution: Fukushima is the long tail that never stops wagging. If official cost estimates rise, or timelines slip further, it signals more capital needs and likely longer government involvement. The spread between government figures and independent estimates like JCER’s is where investor anxiety lives.

-

Retail Customer Retention Rate: Deregulation made the customer base contestable. Retention is the simplest scorecard for whether TEPCO’s relationships still have value—especially against competitors selling trust, price, and “cleaner” power as their differentiators.

The Bull and Bear Case

The Bull Case:

TEPCO is one of the strangest comeback stories in modern business—and in some ways, that’s the opportunity. A company that endured an extinction-level crisis is still operating, still supplying one of the biggest metro economies on Earth, and still has the state standing behind it.

If you believe the next chapter is finally about operational recovery, the catalyst is obvious: Kashiwazaki-Kariwa. A restart there isn’t just symbolic. It’s meaningful earnings power coming back online. Layer on Japan’s renewed push for nuclear—plans that would raise nuclear’s share of the energy mix to around 20% by 2040—and the policy backdrop starts to look more supportive than it has in years.

From this angle, Fukushima is no longer a surprise; it’s a known obligation. The burden is still enormous, but it’s expected, planned for, and ultimately backstopped. Meanwhile, JERA gives TEPCO real scale in thermal generation and fuel procurement, which matters in a country that still imports the bulk of its energy. And as global pressure to cut emissions rises, nuclear power’s return to favor could, over time, move from reputational poison to strategic advantage.

The Bear Case:

The counterargument is that TEPCO isn’t really a turnaround story at all—it’s a managed entity, designed to keep the lights on and keep Fukushima moving forward.

Start with ownership. With the government holding a majority stake, the upside for minority shareholders is constrained by design. Then there’s the long shadow of the cleanup itself. Decommissioning and compensation have repeatedly cost more than expected, and many expect that pattern to continue. Independent analysts have warned that final costs could reach 80 trillion yen or more—far above official projections—because this is the kind of problem that reveals new complexity every time you try to solve the last one.

At the same time, TEPCO is trying to compete in a deregulated retail market where margins are thinner and customer loyalty can no longer be assumed. The brand still carries Fukushima as a permanent scar. Public opposition to nuclear power has faded from its 2011 peak, but it hasn’t disappeared—and it can surge back instantly if anything goes wrong.

And perhaps the most worrying thread is cultural. This is the same organization that spent decades falsifying inspections and managing perception. Critics argue that while structures have changed, habits are harder. Kashiwazaki-Kariwa has had its own run of trouble—security breaches, unfinished safety work, and construction delays—that raises an uncomfortable question: has operational discipline truly caught up to the stakes?

Because if a serious scandal hits any TEPCO facility, it doesn’t just hurt one plant. It can freeze the entire restart agenda again.

Myth vs. Reality:

Myth: TEPCO has fully reformed its safety culture.

Reality: TEPCO has made substantial changes, but recurring issues at Kashiwazaki-Kariwa—including security breaches that delayed restart approvals—suggest old instincts may still surface under pressure.

Myth: Decommissioning costs are known and contained.

Reality: Official estimates have repeatedly proven optimistic. Independent analysis suggests the final bill could be multiples higher than projected.

Myth: TEPCO will return to being a normal utility once decommissioning is complete.

Reality: Decommissioning is still described as a 30-to-40-year project at minimum. For any realistic investment horizon today, TEPCO remains a decommissioning-and-compensation organization that also happens to sell electricity.

Conclusion: Can a Company Truly Reinvent Itself?

TEPCO’s story forces an uncomfortable question about corporate redemption: after a catastrophic failure, can an institution truly change—or does the original sin become the only lens anyone ever uses?

Fourteen years after Fukushima, TEPCO is still here. Not restored, not redeemed, but surviving: part-nationalized, publicly scrutinized, and kept afloat because the alternative is worse. The company that once stood for Japan’s post-war ascent now stands for something else entirely—the costs of regulatory capture, the danger of institutional complacency, and the way a single event can rewrite a century of reputation.

For investors, that makes TEPCO a uniquely strange proposition. On one hand, it’s a company Japan can’t let fail, with government backing and real operating cash flow. On the other, it’s a utility carrying a liability measured in decades, operating under state control, and trying to rebuild trust with a brand that, for many people, still means Fukushima. A nuclear restart offers a clear near-term catalyst. The decommissioning burden, political oversight, and cultural legacy are the hard-to-price risks that never really go away.

That’s why the planned restart at Kashiwazaki-Kariwa in January 2026 matters beyond the earnings math. Symbolically, it’s the company that caused Fukushima returning to nuclear operations. Whether that moment reflects deep reform—or simply the passage of time and a country’s shifting energy needs—will only become clear in what happens after the restart, not on the day it begins.

The deeper takeaway may not be about TEPCO at all, but about the system that shaped it. Regional monopolies insulated from competition. Regulators embedded in the same machinery that promoted the industry. Cost-plus economics that dulled the incentive to be ruthless about efficiency and risk. None of that made failure inevitable, but it made a slow drift toward disaster far more plausible than it should have been.

Japan’s electricity market will keep evolving, and TEPCO will keep being tested in ways it never faced in the monopoly era. Whether it emerges from this multi-decade ordeal stronger—or simply smaller and more supervised—is a question with a timeline as long as the cleanup itself.

Tokyo’s lights still shine, and TEPCO still helps power them. But Fukushima Daiichi—still being decommissioned, still demanding resources and attention—hangs over the company like a permanent second shadow. Some failures don’t end. They get managed, one difficult year at a time.

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music