Mitsui O.S.K. Lines: From Coal Steamers to Blue Ocean Social Infrastructure

I. Introduction & Episode Roadmap

Picture the Tokyo waterfront. Out beyond the skyline and the container yards, one of the world’s biggest commercial fleets is out there doing its work—mostly invisible to everyone who isn’t directly in the business.

Mitsui O.S.K. Lines doesn’t sell a gadget you can hold or an app you can tap. It moves the physical world. Dry cargo across oceans. Cars in purpose-built carriers. Energy in tankers and, most importantly today, liquefied natural gas carriers. And it has been stretching beyond “just shipping” into what it describes as social infrastructure businesses: logistics, terminal operations, ferry service, real estate, even offshore wind power.

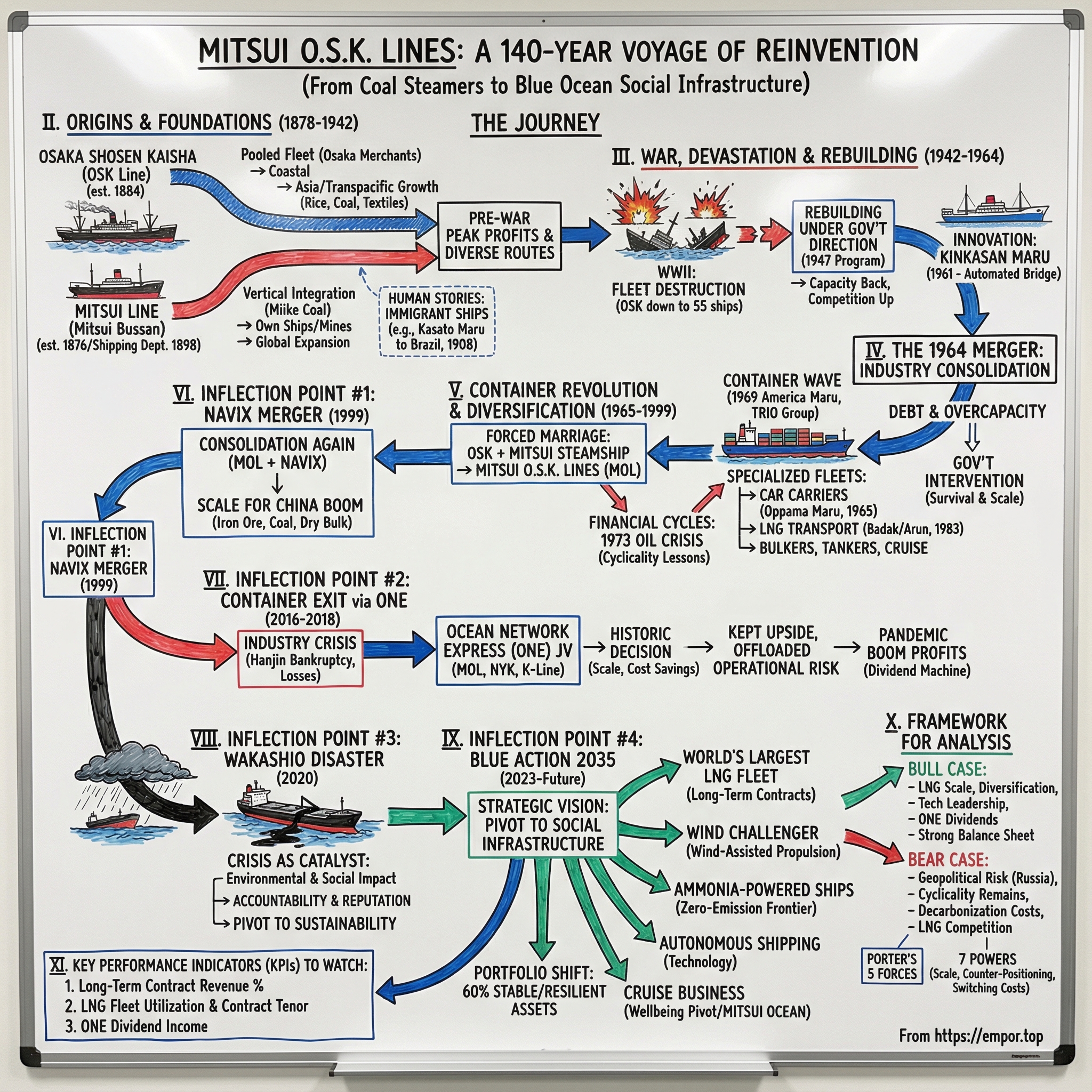

That breadth raises the central question of this story: how does a company survive for 140 years in one of the most cyclical, capital-intensive, unforgiving industries on earth? Not by being the biggest. Not by winning every boom. But by repeatedly making the hard strategic call at the right moment—when to consolidate, when to exit, and when to commit early to what’s next.

In 2024, one of MOL’s roots—Osaka Shosen Kaisha (OSK Line)—hit its 140th anniversary, dating back to May 1884. Over that arc, MOL’s lineage runs from coal-hauling steamers serving a Meiji-era Japan racing to industrialize, to operating the world’s largest fleet of LNG carriers today. In a lot of ways, MOL’s evolution tracks Japan’s: from an island nation building modern industry, to a global trading power, to a country now navigating energy security and decarbonization at the same time.

A few themes keep showing up again and again in MOL’s history, and they’re surprisingly modern. Consolidation, twice, each time reshaping the company. The willingness to step away from commoditized, brutal businesses—most notably the 2016 decision to fold its container shipping operations into the Ocean Network Express joint venture. A crisis that forced a reckoning, the 2020 Wakashio oil spill off Mauritius. And then the forward-looking pivot: “Blue Action 2035,” management’s plan to transform MOL into what it calls a “social infrastructure company.”

Today, MOL is headquartered in Toranomon, Minato, Tokyo. It’s one of the world’s largest shipping companies, and the largest tanker owning and operating company in the world. But the most interesting part isn’t its size—it’s how it’s tried to change the nature of its business. In an industry defined by volatile spot rates and brutal downcycles, MOL has been shifting toward steadier, longer-term contracted operations: LNG transport, car carriers under multi-year agreements, and offshore infrastructure. The goal is simple: less “ride the cycle,” more predictable earnings and resilience when the cycle turns.

II. Origins: The Mitsui Zaibatsu & Osaka's Merchant Mariners (1878–1942)

The Osaka Shosen Kaisha Story

Spring, 1884. In Osaka, 55 small shipowners came to the same conclusion at the same time: alone, they were going to get picked off.

Japan was industrializing fast. Trade was booming. But the shipping business was already leaning toward scale, and the biggest, best-connected players were starting to dominate. So these merchants did what Osaka merchants have done for centuries—they formed a coalition strong enough to survive the next wave.

That coalition became Osaka Shosen Kaisha, or OSK. The group’s leading figure was Hirose Saihei, a senior manager of the Sumitomo zaibatsu and a heavyweight in Osaka finance. OSK launched with ¥1.2 million in capital and a pooled fleet of 93 vessels totaling 15,400 gross registered tons. More important than the numbers was the structure: a cooperative model where lots of small owners effectively acted as one.

OSK started close to home, running coastal services through the Seto Inland Sea—practical routes linking the Hanshin area and Kyushu. But the company didn’t stay local for long. As commerce surged in rice, coal, and textiles, OSK kept recapitalizing to fund bigger ambitions, reaching ¥10 million by 1898. New routes followed: Korea in 1890, China in 1893, and eventually services on the Yangtze River.

By the Taisho era, OSK wasn’t just a coastal operator anymore. It had expanded into tramp and liner services across the Asia-Pacific, with routes like Hong Kong to Tacoma in 1908, Kobe to Bombay in 1911, and transpacific services reaching San Francisco and New York by 1920. What began as a defensive merger of small operators had turned into an international shipping enterprise.

The Mitsui Line Origins: Vertical Integration as Strategy

OSK’s origin story is about cooperation. Mitsui’s is about control.

What became “Mitsui Line” began inside Mitsui Bussan Kaisha, the trading company founded in 1876. Mitsui Bussan secured exclusive rights to export and market coal from the state-run Miike mine—then did the obvious next thing: it started moving that coal itself. It chartered vessels, and by 1878 it had bought its own steamship. In 1888, it bought the mines.

That’s vertical integration in its purest form: own the source, own the transport, and protect the margin all the way to the customer.

Mitsui Bussan formalized this push into shipping over time. The shipping section was established in 1898, later expanded into a full Shipping Department, and moved to Kobe in 1904. Route expansion followed. Mitsui opened a Bangkok route in 1928, a Philippines route in 1931, a Dalien-to-New York route in 1932, and a Persian Gulf route in 1935.

Mitsui also built an ecosystem around the core shipping business. The shipbuilding department was spun off as the Mitsui Tama Shipyard in 1937. Then, in 1942, the Shipping Department itself became an independent company: Mitsui Steamship Co., Ltd., capitalized at ¥50 million, with Takaharu Mitsui elected chairman.

Pre-War Expansion and Peak Profits

By the early 1940s, OSK had reached a pre-war peak. Profits topped out in 1941, when OSK was capitalized at ¥87 million and operated 112 vessels totaling 557,126 GRT. In a few decades, it had grown from a pooled fleet of small coastal ships into a serious ocean-going operator—scaled, capitalized, and deeply tied to the industrial economy Japan was building.

Human Stories: The Immigrant Ships

But the story of these companies isn’t just balance sheets and routes. It’s people.

On 18 June 1908, the Kasato Maru arrived in Santos, Brazil. On board were 781 Japanese passengers who had left Kobe nearly two months earlier, headed for agricultural work—many bound for coffee plantations in São Paulo.

Over time, more than 180 thousand Japanese immigrants made that crossing aboard a MOL vessel. The company wasn’t only moving commodities; it was moving lives, building a bridge between Japan and a diaspora that would reshape families and communities across an ocean.

By the time the world slid toward war, the stage was set. Two very different traditions had matured in parallel: Osaka’s merchant culture of pooling strength and adapting quickly, and the Mitsui zaibatsu’s instinct for industrial strategy and vertical integration. Those two currents would eventually collide—and fuse—into what became MOL.

III. War, Devastation & Rebuilding (1942–1964)

The Destruction of Japan's Merchant Marine

World War II didn’t just disrupt Japanese shipping. It shattered it.

During the war, OSK—like the rest of Japan’s shipping industry—lost control of its own destiny. Vessels were requisitioned for military transport, and Japan’s merchant fleet became a target. Allied submarines and aircraft went after the sea lanes that kept the economy and the war effort moving.

The result was brutal. After years of expansion leading up to the conflict, OSK emerged from the war with its fleet reduced to 55 vessels. To grasp the scale of the catastrophe, consider that NYK, Japan’s largest shipping line, lost 185 ships supporting operations in the Pacific. Shipping wasn’t just cyclical anymore; it was existential.

Rebuilding Under Government Direction

When the war ended, rebuilding didn’t happen organically. It was engineered.

Japan launched a government-sponsored shipbuilding program in 1947—industrial policy aimed at restoring the merchant fleet that would carry the country’s exports back into the world economy. By 1950, OSK returned to global service. And by the end of 1957, it had almost recovered the sailing rights it held before the war through the FEFC, running 18 voyages per month across 13 overseas liner routes.

But there was a catch. The same program that rebuilt the fleet also intensified competition. With financing available, anyone with capital could build ships. Capacity came back fast—and with it, the familiar problem of shipping: too many hulls chasing too little demand.

OSK itself built 38 ships under the program, scaling back up in a hurry. It also restarted the emigration business that had once been central to its identity. In 1953, OSK established an eastbound route to South America to transport emigrants from Japan. Initially it worked. Then the market faded. By 1962, emigrants fell to fewer than 2,000 per year, and in 1963 OSK set up Japan Emigration Ship Co., Ltd. (JES) to separate out what had become a loss-making operation.

That move—hiving off a declining business so the core could keep moving—would become a familiar MOL pattern.

The Innovation Edge: Kinkasan Maru

While OSK was rebuilding routes and tonnage, Mitsui Steamship pushed a different lever: technology.

In 1961, MS took delivery of Kinkasan Maru, described as the first bridge-controlled ship in the world. The goal was practical and strategic at the same time: rationalize crew needs while improving engineers’ working conditions. MS worked with Mitsui Shipbuilding & Engineering Co., the successor to Mitsui Tama Shipyard, to design a new kind of vessel—one where operations that used to require more manual supervision could be handled from the bridge.

MS put Kinkasan Maru, and another bridge-controlled ship, onto the New York route, which had reopened in 1951. Automation wasn’t just a technical flex; it was a signal that Japanese shipping intended to compete on operational sophistication, not only on price.

By the time MS merged with OSK in 1964, it had built 38 vessels since 1950 and had the largest operating tonnage in Japan. And yet, the financial picture told a different story. MS’s performance from 1950 to 1964 was disappointing. At the time of the merger it was capitalized at ¥5.5 billion—but carried debts of ¥26.7 billion.

So even with new ships, new technology, and massive operating scale, the economics still didn’t work. The industry had rebuilt itself into overcapacity. Both legacy companies were under strain.

And Tokyo was paying attention.

IV. The 1964 Merger: Japan's Shipping Industry Consolidation

The Forced Marriage

By 1964, Tokyo stopped watching from the sidelines and stepped onto the bridge.

Under the Law Concerning the Reconstruction and Reorganization of the Shipping Industry, the government pushed through a merger between Osaka Shosen Kaisha (OSK), founded in 1878, and Mitsui Steamship Co., Ltd., founded in 1942 out of what had been Mitsui Line. The result was a new company with a new name: Mitsui O.S.K. Lines.

On paper, it was instantly a heavyweight. MOL became Japan’s largest shipping company at the time, capitalized at ¥13.1 billion and operating 83 vessels totaling about 1.237 million tonnes deadweight.

And it wasn’t just MOL. Across Japan, a wave of forced consolidation reduced the field to six major shipping groups. This wasn’t market-driven dealmaking; it was industrial policy. The government looked at an industry bleeding under the weight of too much tonnage and too little pricing power and decided that fewer, larger players were the only way to build something stable enough to compete globally.

The Financial Reality

But this wasn’t a celebration merger. It was a rescue.

OSK and Mitsui Steamship arrived with plenty of ships—and plenty of debt. In 1964, OSK owned 41 vessels totaling 376,539 GRT. It was capitalized at ¥7.6 billion, but carried approximately ¥34.9 billion in debts. Mitsui Steamship, as we saw, brought its own balance sheet problems into the deal too.

That’s why the merger happened: not to chase growth, but to survive the postwar overbuild and the unforgiving economics of shipping.

There was another problem money couldn’t solve quickly: culture. MOL had to stitch together two very different corporate DNA strands—Osaka’s merchant pragmatism and coalition-building, and the Mitsui world of zaibatsu heritage and hierarchy. Making the numbers work was hard. Making the people work together would take even longer.

Still, the strategic logic held. In shipping, fixed costs are relentless, cycles are brutal, and scale can be the difference between riding out a downturn and being wiped out by it. From the wreckage of an industry-wide crisis, MOL emerged as Japan’s biggest shipping player—positioned to face the next revolution that was already forming on the horizon.

V. The Containerization Revolution & Diversification (1965–1999)

Riding the Container Wave

In hindsight, MOL’s 1964 merger couldn’t have been better timed. Just as the company finally had real scale, the industry was about to change in a way that made scale even more valuable.

World shipping was moving toward containerization—the biggest shift in cargo transport since steam displaced sail. For decades, ports had run on muscle and chaos: breakbulk cargo, endless paperwork, and ships sitting idle for days while everything got loaded piece by piece. The container replaced all of that with a standardized steel box that could move seamlessly from truck to train to ship. Loading times collapsed. Reliability jumped. Costs fell. And the companies that adapted fastest rewrote the rules.

MOL moved early. Soon after Japan’s 1964 shipping reorganization consolidated the industry into six groups, MOL began container services on the California route through a space-charter consortium of four Japanese operators. Then came a defining moment: in October 1969, MOL’s first container ship, America Maru, sailed from Kobe to San Francisco.

From there, containerization spread route by route. MOL joined container services to Australia in 1970 with NYK and Yamashita-Shinnihon Steamship Co. It entered the North Pacific route in 1971 with five other Japanese companies. And it expanded into Europe that same year as part of the TRIO Group—alongside Nippon Yusen Kaisha, Overseas Container Lines, Ben Line, and Hapag-Lloyd.

Fleet Diversification

Even as containers became the public face of modern shipping, MOL was also doing something that would matter just as much over the long run: building specialized fleets tied to durable, structural demand.

In 1965, Japan’s first specialized car carrier, the Oppama Maru, entered service. It was an early bet on a sector that was about to explode. As Japan’s automakers surged onto global markets, moving finished vehicles efficiently became its own form of infrastructure—and dedicated car carriers became the tool for the job. MOL would go on to operate one of the world’s largest pure car carrier fleets.

Energy was the next frontier. In 1983, as Japan diversified its energy resources and began importing liquefied natural gas under Free on Board conditions, MOL joined a broader Japanese consortium—alongside NYK, Kawasaki Steamship, Chubu Electric Power Company, and other electricity and gas companies—to establish two specialized LNG transport companies, Badak LNG Transport Inc. and Arun. Together, they operated seven LNG ships to carry LNG from Indonesia.

That same year, MOL took delivery of Kohzan Maru, Japan’s first large-sized methanol carrier, transporting methanol from Saudi Arabia to Japan.

Over the following decades, MOL kept widening its toolkit: bulk carriers, crude oil carriers, leisure cruise ships, and ever-larger vessels designed for specific trades. The throughline was consistent—don’t bet the company on one cargo, one route, or one rate cycle.

Financial Cycles and Survival

After the merger, results improved. Losses carried forward were written off in 1966. MOL recapitalized to ¥20 billion in 1968 and ¥30 billion in 1972. By the mid-1970s, the fleet had grown dramatically, both in owned ships and time-chartered tonnage.

But the industry never stopped being the industry. Shipping was still brutally cyclical, and growth could turn into a trap when markets flipped. MOL even canceled tanker orders that were already under construction—an unglamorous but necessary move to curb overcapacity.

Then came the 1973 oil crisis, which slammed costs and demand patterns across global trade. It forced MOL to pull back in tankers, while reinforcing the logic of diversification into other vessel types and business lines.

The takeaway from this era is simple: MOL didn’t “solve” cyclicality. It learned to live with it—by spreading risk across specialized fleets, and by making hard capacity decisions before the cycle made them inevitable.

VI. Inflection Point #1: The Navix Merger & Consolidation (1999)

Building Scale for the Coming China Boom

By the late 1990s, the Asian financial crisis had rolled through the region and reminded everyone what shipping really is: a leverage business with waves that can drown you.

In 1999, MOL chose the same medicine Japan had used before. It merged with Navix Line, creating a new Mitsui O.S.K. Lines, Ltd. Around the same time, Brazil Maru—one of the world’s largest iron ore carriers at the time—entered service. It was a signal of what the combined company was prioritizing: bulk, scale, and staying power.

Why consolidate again? The logic rhymed with 1964. Shipping rewards operators who can spread fixed costs across more ships, run bigger networks, and negotiate from a position of strength. The Navix merger reinforced MOL’s bulk shipping capabilities just as a new demand engine was warming up.

That engine was China. Over the next decade, as China poured concrete at a historic pace—cities, highways, factories—the world needed mountains of iron ore, coal, and other dry bulk commodities. MOL, newly enlarged and more heavily geared toward bulk, was positioned to ride what became the biggest dry bulk boom the industry had ever seen—and it did.

VII. Inflection Point #2: The Container Shipping Exit via Ocean Network Express (2016–2018)

The Industry Crisis

By 2016, container shipping had turned into a value-destroying grind: too many ships, too little demand, and freight rates that couldn’t cover the industry’s cost base. Consolidation wasn’t a strategic trend so much as an industry-wide emergency measure—because the old structure simply couldn’t survive.

Then came the moment that made the danger impossible to ignore. On August 31, 2016, South Korea’s Hanjin Shipping—at the time one of the world’s largest container carriers—declared bankruptcy. While the world was watching U.S. politics, Brexit, and the Rio Olympics, supply chains quietly seized up. Container ships were left hovering offshore, unsure whether ports would even let them berth. Cargo owners scrambled. The message to every other operator was unmistakable: if a top-six carrier could collapse, anyone could.

Against that backdrop, the three big Japanese lines felt the pain directly. Collectively, NYK, MOL, and K Line posted a half-year operating loss of $484 million. Containers weren’t just volatile; they were threatening to drag down the rest of the enterprise.

The Historic Decision

So, on Monday, October 31, 2016, Kawasaki Kisen Kaisha (K Line), Mitsui O.S.K. Lines, and Nippon Yusen Kaisha (NYK) made a decision that would reshape Japanese shipping: they agreed to combine their container businesses into a brand-new joint venture.

The motivation was painfully straightforward. The three carriers’ annual container sales had fallen sharply from their 2014 peak, and from early 2015 through early 2017 they collectively racked up around $1 billion in operating losses in their container operations. The math wasn’t working, and the industry was telling them it wasn’t going to get easier.

The new company would be called Ocean Network Express—ONE. NYK held 38% of the venture, with MOL and K Line at 31% each. On launch, it was the world’s sixth-largest container shipping company.

After beginning corporate and sales activities in October 2017, ONE started operations in April 2018. Its headquarters were in Japan, with an operations headquarters in Singapore, regional headquarters in the United Kingdom, the United States, Hong Kong, and Brazil, and local offices across 90 countries.

The Strategic Logic

From the outside, this looked like a retreat. In reality, it was one of those rare shipping moves that was both defensive and elegantly offensive at the same time.

First, scale. ONE combined fleets and networks into a single operator with more than 1.4 million TEUs of capacity, service coverage across 90 countries, and roughly a 7% global share. In a business where unit costs and network density matter, that kind of heft wasn’t optional anymore.

Second, cost savings. The joint venture was designed to squeeze duplication out of the system: consolidating bases, streamlining payroll, and—crucially—combining port contracts and other supplier agreements so ONE could negotiate using the best terms any of the three carriers previously had.

Third, and most strategically important for MOL: it kept upside exposure without the operational burden. MOL didn’t have to run a brutally cyclical, margin-thin container network anymore. It could own 31% of the results and redeploy management attention and capital toward higher-margin, more stable businesses.

ONE's Performance Vindication

The bet didn’t just work—it worked at exactly the moment the world broke in a way that rewarded container capacity.

During the pandemic-era shipping boom, ONE’s profits surged, and those gains flowed back to its parent companies. Years later, the scale of the business was still evident in its reported performance: for FY2024 (April 2024 to March 2025), ONE reported revenue of US$19,233 million, up 32% year over year, with net profit of US$4,244 million.

In other words, what looked like a forced move in 2016 became a structural advantage. MOL effectively stepped away from the operational complexity and day-to-day risk of container shipping—while keeping a meaningful share of the upside when the cycle finally swung back.

VIII. Inflection Point #3: The Wakashio Disaster—Crisis as Catalyst (2020)

The Incident

On July 25, 2020, while the world’s attention was locked on COVID-19, a different kind of crisis unfolded in the Indian Ocean—one that would hit MOL in the most public, visceral way possible.

That afternoon, the Wakashio, a Japanese-controlled bulk carrier operated by MOL, ran aground on a coral reef off Mauritius. In the weeks that followed, the ship began leaking fuel oil. Then, in mid-August, it broke apart. Although much of the fuel on board was pumped out before the hull split, an estimated 1,000 tonnes still spilled into the sea—an event some scientists described as the worst environmental disaster Mauritius had ever faced.

The Impact

For Mauritius, the spill was more than an environmental tragedy. It threatened the country’s economic lifeblood.

Tourism was a major pillar of the Mauritian economy, with spending of about ₨ 63 billion (around US$1.51 billion) in 2019—an industry built on the very marine scenery and wildlife now at risk. Greenpeace warned that thousands of species could be affected, with knock-on consequences for the country’s economy, food security, and public health.

The damage landed directly on communities along the coast. One finding was that the spill affected around 48,000 people across 17 coastal villages along a 30-kilometer stretch of shoreline.

Prime Minister Pravind Kumar Jugnauth declared a state of environmental emergency and called for international help.

MOL's Response

MOL, as the ship’s operator and charterer, moved quickly into response mode—but there was no way to “out-operate” the underlying reality. A MOL-operated vessel had caused a national disaster.

The company pledged ¥1 billion (about US$9.37 million) to support recovery efforts through the Mauritius Natural Environment Recovery Fund, intended to fund environmental projects and support the local fishing community. MOL’s president framed the pledge as a matter of social responsibility and apologized for the damage.

After the disaster, MOL’s Mr. Ikeda traveled to apologize in person and pledged that a Wakashio incident must never be allowed to happen again.

As devastating as it was, Wakashio became a turning point. It forced a sharper, more modern kind of accountability: the idea that a shipping company’s license to operate isn’t just granted by regulators or customers, but by society—by whether communities believe the company can be trusted to operate responsibly. That lesson would echo through MOL’s next act, and into the “Blue Action 2035” strategy it unveiled three years later.

IX. Inflection Point #4: Blue Action 2035—The Pivot to Social Infrastructure

The Strategic Vision

In March 2023, MOL unveiled its most ambitious plan yet: a new long-term management plan called “BLUE ACTION 2035,” starting in FY2023.

This was a real shift in how the company managed itself. Since FY2017, MOL had operated on a rolling plan—revisiting strategy every year. Now, backed by a markedly stronger financial position, it committed to a 13-year arc: a stated vision of what the group wanted to be in 2035, based on the Group Vision revised in April 2021.

The strategic move underneath the branding was simple, and profound for shipping: remodel the portfolio so the company could stay profitable even when the cycle turned ugly. MOL set a target to lift the asset ratio of stable, market-resilient revenue businesses to 60%. It framed the plan around three core strategies—portfolio, regional, and environmental—and elevated five “highest priority items” as core initiatives to address sustainability issues.

And it described the end state in striking language: the MOL Group would “take the leap” to becoming a global social infrastructure company.

Investment at Scale

This wasn’t a vision deck without a checkbook behind it.

As part of “BLUE ACTION 2035,” MOL planned major investment in marine and global environmental conservation, including an investment program of $4.5 billion (JPY650 billion) from FY2023 to FY2025. The company’s bonds tied to this effort received the highest rating from the Japan Credit Rating Agency.

Phase 1 of the plan—the initial three years beginning in April 2023—hit its midpoint in October, and MOL reported it had built equity capital to over 2.6 trillion yen on the back of strong performance, while also making “good progress” on investing for future growth.

For the first three years alone, MOL set an investment plan of 1.2 trillion yen. In practice, that meant leaning into energy and environmental investments, plus more stable, non-shipping earnings streams like real property. The company continued ordering new LNG carriers, acquired chemical tanker company Fairfield Chemical Carriers, invested in MODEC, Inc., and formed a capital alliance with wind power maintenance company Hokutaku Co., Ltd.

The pattern is consistent: reduce dependence on the most volatile parts of shipping, and keep building “infrastructure-like” profit streams that can hold up in a downturn.

The World's Largest LNG Fleet

At the center of the transformation sits LNG.

MOL’s LNG fleet expanded to 107 vessels as of the end of March. Company materials also showed 33 LNG carriers on order, with a total LNG fleet of 127 vessels—making it the world’s largest LNG carrier fleet by number of ships.

The reason LNG is so strategically important to MOL isn’t just scale—it’s the contract structure. MOL said its LNG carrier business had “secured stable profits” thanks to existing long-term charter contracts and the delivery of newbuildings. And it projected that stability would continue, supported by those contracts and by additional LNG vessels scheduled for delivery in the current fiscal year.

This is the portfolio logic of “BLUE ACTION 2035” in its purest form: long-duration, contracted infrastructure revenue that can buffer the volatility of spot shipping markets. As more countries shift away from coal and toward natural gas as a transition fuel, MOL’s LNG fleet functions less like a set of ships and more like a critical piece of energy infrastructure.

Environmental Transformation: Wind Challenger

If LNG is MOL’s stability play, Wind Challenger is its statement that “decarbonization” doesn’t have to be theoretical.

Wind Challenger is MOL’s modern reimagining of sail propulsion for commercial vessels—designed to cut greenhouse gas emissions by using wind as a clean, unlimited source of energy. The system uses proprietary technology to sense wind direction and speed in real time and automatically control sail extension, contraction, and rotation.

In October 2022, MOL completed construction of the 100,000-DWT coal carrier SHOFU MARU equipped with Wind Challenger. Over roughly 18 months through April 2024, the ship completed seven round-trip voyages to Japan, mainly from Australia, Indonesia, and North America. MOL reported fuel consumption reductions of up to 17% per day, equivalent to about 5% to 8% per voyage on average.

MOL also planned to bring the technology to LNG carriers. The company said the first Wind Challenger-equipped LNG carrier—described as the world’s first LNG carrier with a wind-assisted ship propulsion system—was under construction at Hanwha Ocean’s Geoje Shipyard and scheduled for delivery in 2026.

The rollout ambition is large: MOL Group planned to launch 25 vessels equipped with Wind Challenger by 2030, and 80 vessels by 2035.

Ammonia-Powered Ships: The Zero-Emission Frontier

Wind assistance cuts fuel burn. Ammonia is about changing the fuel entirely.

MOL has been working on ammonia propulsion as a pathway toward zero-emission ocean shipping. Three Capesize bulk carriers—ammonia-fitted, with capacity of 210,000 dwt—were set to be co-owned by CMB.TECH and MOL and chartered to MOL for 12 years each, with delivery scheduled for 2026 and 2027. MOL announced in 2023 that these vessels would be fitted with WinGD’s ammonia-powered X72DF engines.

More broadly, between 2026 and 2029, Mitsui O.S.K. Lines planned to add three ammonia-powered Capesize bulkers and six chemical tankers to its fleet.

Autonomous Shipping

Alongside new fuels and wind assistance, MOL has been pushing on a different frontier: autonomy.

MOL, together with two group companies and consortium partners, concluded what it described as the world’s first sea trial of unmanned ship operation from port to port—departing Tsuruga Port in Fukui Prefecture and arriving at Sakai Port in Tottori Prefecture on January 24 and 25—as part of the MEGURI2040 unmanned ship project led by The Nippon Foundation.

In August 2022, MOL’s MV Mikage sailed 161 nautical miles over two days from Tsuruga to Sakai and successfully completed a crewless sea voyage that included docking of an autonomous coastal container ship.

Cruise Business: The Wellbeing Pivot

“BLUE ACTION 2035” isn’t only about changing how ships move. It’s also about building earnings that don’t depend on freight rates at all.

In the plan, MOL positioned the cruise business as one of its non-shipping, stable-profit businesses—something that could help cover the volatility of the shipping market during recessions. MOL Cruises planned to add new ships in addition to the MITSUI OCEAN FUJI, with the stated goal of enhancing MOL Group’s corporate value and advancing the 2035 vision.

MOL announced the December 1 launch of the MITSUI OCEAN FUJI, owned by group company MOL Cruises. Described as the first cruise ship in Japan with all suite cabins, it offered five “Debut Cruise” packages and a New Year’s cruise through January 2025.

“We launched MITSUI OCEAN FUJI in December 2024, and are very pleased with the guest reaction to the ship and onboard product,” said Tsunemichi Mukai, President of MITSUI OCEAN CRUISES.

X. The Bull and Bear Case: A Framework for Analysis

The Bull Case

- World's Largest LNG Fleet in a Structural Growth Market

MOL’s biggest edge is also its clearest bet: LNG. As more countries try to replace coal with natural gas—and, over time, move toward next-generation fuels—MOL’s scale and know-how in gas transport matter more, not less. Just as important, LNG shipping is built around long-term charter contracts, often lasting 15 to 25 years for major projects. That’s the closest thing shipping has to revenue predictability.

- Strategic Diversification into Stable Businesses

“BLUE ACTION 2035” isn’t subtle about what it wants: a portfolio where stable businesses carry more of the weight, with a goal of getting 60% of assets into market-resilient revenue streams. In practice, that means more long-term contracted shipping and more non-shipping earnings—cruise operations, real estate via Daibiru, and ferry services—so MOL isn’t living and dying by spot markets.

- Technology Leadership

MOL isn’t treating decarbonization as a distant problem. Wind Challenger, autonomous navigation trials, and ammonia-powered ships all push the company toward a future where emissions rules get stricter and customers demand cleaner transport. As policies tighten—including the EU’s emissions trading scheme now covering shipping—operators that can deliver lower-carbon service may be able to win cargo, protect margins, and secure better contracts.

- ONE as a Dividend Machine

The Ocean Network Express structure is a rare strategic sweet spot: MOL kept a 31% stake in container shipping upside without having to run the day-to-day business. In strong markets, ONE can throw off meaningful dividends. In weak markets, MOL’s exposure is contained within the joint venture rather than dragging the entire company into the container cycle.

- Strong Balance Sheet

With equity capital above ¥2.6 trillion, MOL has room to maneuver. That matters in shipping, where downturns punish weak balance sheets and where the next fleet upgrade cycle—new fuels, new designs, new compliance requirements—won’t be cheap. Financial flexibility is its own competitive advantage.

The Bear Case

- Geopolitical Risk: Russia Exposure

MOL’s involvement in Russian energy projects creates a real overhang. Even after international sanctions were imposed following Russia’s 2022 invasion of Ukraine, MOL maintained ties through long-term charter contracts with Russian operators, including the Sakhalin-2 liquefied natural gas project, now under Russian state control. If sanctions tighten further, the company faces reputational risk and potential financial impacts, including write-downs.

- Shipping Remains Cyclical

Even a smarter portfolio doesn’t repeal gravity. Dry bulk, car carriers, and tankers still swing through boom-and-bust cycles, and correlations rise fast in a global slowdown. A synchronized recession would pressure multiple MOL segments at once—exactly the scenario diversification is meant to soften, but can’t fully eliminate.

- Decarbonization Costs

MOL’s net-zero-by-2050 ambition implies heavy capital spending: fleet renewal, new propulsion systems, and fuel transitions that are still expensive and operationally complex. Green ammonia and green methanol remain costly, and infrastructure is uneven. If the cost curve doesn’t come down quickly, early movers can end up wearing higher costs before the market fully rewards them.

- Competition in LNG

Being the largest LNG operator by vessel count doesn’t guarantee lasting pricing power. Major players are expanding, including Qatar Energy’s fleet build-out, and competitors like NYK and other Asian national carriers are also scaling up. Long-term contract economics depend on disciplined supply and rational ordering—two things shipping has historically struggled to maintain.

Porter's Five Forces Analysis

Supplier Power: Moderate

Shipbuilders can gain leverage during ordering booms, though shipyard overcapacity in other periods tends to favor owners. Fuel supply is fragmented, but the availability of compliant fuels and bunkering infrastructure can still become a constraint.

Buyer Power: Varies by Segment

In LNG, customers like utilities and oil majors have meaningful negotiating leverage, especially on long-term charters. In spot-oriented segments, buyers typically have less contractual power—but pricing can still collapse when capacity is abundant.

Threat of Substitutes: Low

There is no true substitute for ocean shipping in intercontinental trade. Air and rail compete only in narrow use cases.

Threat of New Entrants: Low

The barriers are real: enormous capital requirements, specialized operational expertise, regulatory complexity, and long-standing customer relationships. Still, state-backed expansion—particularly from China—can change the competitive landscape even when pure economics would discourage it.

Competitive Rivalry: High

Shipping is structurally competitive. When capacity outruns demand, rates converge toward cost. Service quality, technology, and relationships matter, but they don’t fully insulate anyone from the cycle.

Hamilton Helmer's 7 Powers Analysis

Scale Economies:

MOL’s fleet size supports cost advantages in ship management, procurement, and customer coverage. In LNG specifically, scale can translate into leverage with shipyards and charterers.

Network Economies:

Limited in most shipping segments, though ONE creates network benefits in container shipping through route breadth and service density.

Counter-Positioning:

Investments in Wind Challenger, autonomous operations, and ammonia propulsion can differentiate MOL against competitors that delay committing to unproven technologies.

Switching Costs:

Long-term charters, especially in LNG, create meaningful switching costs. Customers build operations around specific vessels, performance standards, and reliability—making changes disruptive and expensive.

Branding:

Generally limited in industrial shipping. But in cruising, MITSUI OCEAN CRUISES is explicitly trying to build brand value, where customer perception can translate into pricing.

Cornered Resource:

MOL’s institutional expertise, deep relationships with major energy customers, and long-standing Japanese corporate networks are intangible assets that are difficult to replicate quickly.

Process Power:

Operational know-how in LNG, plus the practical application of technologies like Wind Challenger and autonomous navigation systems, can become embedded advantages that compound over time.

XI. Key Performance Indicators: What to Watch

If you want a quick read on whether MOL’s big pivot is actually working, there are three metrics that tell the story better than any slogan:

1. Long-Term Contract Revenue Percentage

This is the north star. The more of MOL’s revenue is locked in under long-term contracts, the less the company lives and dies by spot-market swings. MOL has put a stake in the ground with its “60% stable, market-resilient assets by 2035” goal. If that ratio keeps moving up, it’s evidence the transformation is real.

2. LNG Fleet Utilization and Contract Tenor

MOL’s LNG business is built on two things: ships staying employed, and contracts staying long. High utilization is table stakes, but the more revealing indicator is the average remaining length of charter contracts. Long-dated charters—think on the order of 15 years—create the kind of earnings visibility shipping almost never gets. If contract lengths shorten or more volume drifts toward spot, volatility creeps back in.

3. ONE Dividend Income

ONE is MOL’s exposure to containers without having to run the container business—and when the container market is strong, that structure can throw off meaningful cash. So the KPI here is simple: what ONE earns, and what it pays out. Watching ONE’s reported results and dividend announcements is the cleanest way to gauge how much this “kept the upside, offloaded the pain” bet is contributing. In FY2024, ONE’s strong performance flowed through in a material way for MOL.

XII. Investment Considerations

MOL is a nuanced investment story. Over the past decade, it hasn’t just tried to get better at shipping—it has tried to change what kind of shipping company it is. The strategy is clear: tilt the portfolio away from the most brutal, commoditized parts of the industry and toward businesses that behave more like infrastructure, with long-term contracts and steadier cash flows.

There are real reasons that thesis resonates. MOL’s scale in LNG, its push into decarbonization technologies like Wind Challenger, and the decision to shift container operations into Ocean Network Express all point to management thinking in decades, not quarters.

But the risks don’t disappear just because the story is compelling. Investors still have to underwrite geopolitical exposure, including ties to Russian energy projects. They still have to accept that shipping is cyclical by nature, even with a more diversified mix. And they have to believe MOL can execute a capital-intensive decarbonization transition without overbuilding, overpaying, or arriving too early to fuels and technologies that take longer than hoped to become economic.

That’s the real question behind Blue Action 2035: is it MOL’s next successful reinvention, or an ambitious plan that proves harder to deliver than to announce?

What started in 1884 as 55 Osaka shipowners pooling vessels for survival has become a global operator with capabilities that look a lot like maritime infrastructure. The coal steamers are long gone. In their place: LNG carriers on long-term charters, wind-assisted bulkers already logging real-world fuel savings, and ammonia-powered ships on the way. Where the company once carried emigrants across the Pacific to Brazil, it now talks about wellbeing and hospitality through cruise ships built for modern leisure.

And yet the core remains stubbornly consistent. MOL still exists for one fundamental reason: to move the world’s goods and energy across the ocean. Whether you call that shipping or “social infrastructure,” it’s the same essential service—one that has stayed vital through wars, mergers, technological upheaval, and public crises. The next decade will bring its own tests. For MOL, it’s simply the next leg of a very long voyage.

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music