Nippon Yusen KK (NYK Line): Japan's 140-Year Maritime Empire & The ONE Gamble

I. Introduction & Episode Roadmap

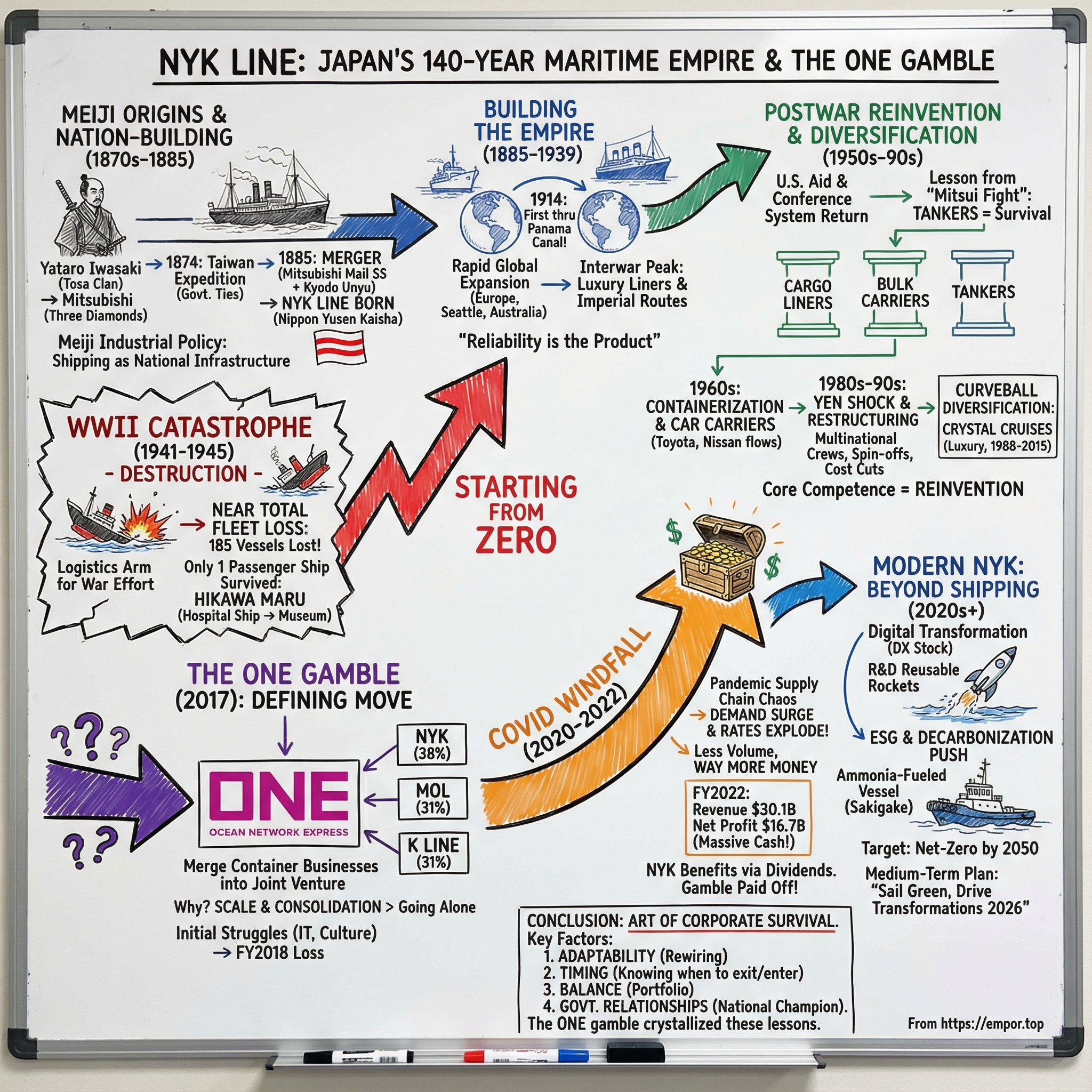

On any given day, in the world’s busiest shipping lanes, you can spot the NYK signature: two bold red stripes on a white funnel, slipping past the horizon on the way to the next port. They belong to Nippon Yusen Kabushiki Kaisha—NYK Line—a company that has quietly assembled one of the largest transportation fleets on Earth.

NYK runs more than 820 ships across just about every major category of ocean transport: container ships, tankers, bulk and woodchip carriers, roll-on/roll-off car carriers, reefer vessels, LNG carriers, even cruise ships. It’s enormous, essential, and—outside Japan—strangely anonymous.

NYK’s timeline reads like a stress test for any business. It traces its roots back to Japan’s samurai era, grew alongside the modern Japanese state, absorbed the shocks of war and economic upheaval, and pushed through the brutal boom-and-bust cycles that define shipping. By the 21st century, it wasn’t just a shipping line anymore—it was a global transportation and logistics empire.

But the most compelling twist comes in 2016, when NYK made a decision that looked almost unthinkable at the time: it agreed to hand over full control of its container shipping operations—long seen as a crown jewel—into a brand-new joint venture with rivals.

That sets up the central question of this story: how did a company founded to carry mail in the Meiji era survive near-total destruction, currency crises, and commodity cycles—only to make its most transformative modern bet by surrendering control of containers in exchange for scale?

By the end of March 2024, the NYK Group operated 824 major ocean vessels, plus fleets of planes and trucks. And nowhere is its scale more visible than in cars. NYK’s roll-on/roll-off fleet alone can carry about 660,000 vehicles—just over 17% of global capacity—with more than 123 ships moving cars built in Japan, the U.S., and Europe to destinations across Asia, the Middle East, the Americas, Oceania, and Africa. In plain terms, NYK runs the world’s largest ocean car carrier fleet.

The journey from 1885 to 2025 spans nation-building, empire, catastrophic loss, postwar resurrection, diversification as a survival strategy, and then a radical restructuring that looked like retreat—until a pandemic turned it into a windfall. It’s a story about knowing what to fight for, what to walk away from, and how to stay standing for 140 years in one of the most unforgiving industries on the planet.

II. The Mitsubishi Origins: Meiji Japan & Nation-Building

The story starts in 1870, just after the Meiji Restoration, when Japan was ripping itself out of centuries of feudal isolation and sprinting to modernize before the Western powers could swallow it whole. In Kochi, on the island of Shikoku, a young merchant named Yataro Iwasaki saw the lever that could move the country: ships.

Iwasaki came from the Tosa domain, home of the powerful Tosa clan. His family had once held samurai status, then lost it to debt—social mobility, in other words, was not supposed to be part of his story. But he was sharp, ambitious, and pragmatic. He worked for the clan and distinguished himself managing its Osaka trading operations. Then he made his move: in 1870, with three steamships chartered from the clan, he launched Tsukumo Shokai. It was the seed that would become Mitsubishi.

His path there wasn’t neat. As a teenager, Iwasaki left for Edo for schooling, only to be pulled back when his father was badly injured in a dispute with the village headman. When Iwasaki accused the local magistrate of corruption for refusing to hear the case, he paid for it—kicked out of his village and sent to prison for seven months.

That brush with power, and the consequences of challenging it, shaped him. After his release, he found his way back into Tosa service, worked as a clerk through Yoshida, and eventually bought back his family’s samurai status. He rose to the top job at the clan’s trading office in Nagasaki, where he handled commodities like camphor oil and paper—and used the proceeds to buy what mattered most in a changing Japan: ships, weapons, and ammunition.

Even the brand was a signal. Iwasaki chose an emblem that fused the three oak leaves of the Tosa crest with the three stacked diamonds of his family crest. From that came the name Mitsubishi—literally, “three diamonds.”

Then came the moment that tied the company to the state. In 1874, Iwasaki provided ships to carry Japanese troops to Taiwan. The government rewarded him with vessels—thirty of them—and in 1875 his company took over the people and facilities of a government-disbanded mail service. With that, the name became Mitsubishi Mail Steamship.

This wasn’t just a commercial relationship; it was a bargain. The government needed a national champion to build maritime power. Mitsubishi needed ships, routes, and legitimacy. In return for patronage, Mitsubishi supported the new state, including transporting troops during the Satsuma Rebellion in 1877. As Japan consolidated politically, Mitsubishi consolidated economically—and the two projects started to look inseparable.

But dominance creates enemies, and Mitsubishi’s success eventually made the government nervous. Mitsubishi Mail Steamship expanded into overseas routes, including service to China and Russia, and came to enjoy what was effectively a monopoly. In the early 1880s, political support shifted. The government sponsored a rival, hoping competition would curb Mitsubishi’s power.

Instead, the fight nearly wrecked everyone. A temporary truce arrived through government intervention, but the rivalry flared again after Iwasaki died in 1885 and his brother Yanosuke took over. The only clean solution was the one the government preferred all along: a merger.

So, in 1885, Mitsubishi Mail Steamship Company and Kyodo Unyu Kaisha were merged into a new company: Nippon Yusen Kaisha—NYK Line. It began life with 58 steamships.

This was Meiji industrial policy in its purest form. By consolidating more than three-quarters of Japan’s steamships into a single joint-stock company, Japan stabilized domestic shipping and created a platform to expand overseas routes—laying early foundations for the country’s emergence as a maritime trading power.

And NYK carried the merger in its flag. The nibiki—two thick red lines on white—symbolized the union of the two predecessors. Over time, those stripes would become familiar in ports around the world.

NYK’s origin also reveals a pattern that would echo across its history: in Japan, shipping was never just business. It was national infrastructure—economic sovereignty and security in steel and steam. That context helps explain why NYK kept getting rebuilt, reshaped, and protected when the industry turned brutal.

III. Building Japan's Maritime Empire (1885-1939)

NYK was born out of Meiji-era industrial policy, but it didn’t behave like a cautious government project. It moved like a company in a hurry.

Within a year of its founding, it launched its first international liner service, connecting Nagasaki to Tianjin. And then it kept pushing outward. By 1896, NYK’s liner network had expanded onto European, Seattle, and Australian routes. In just over a decade, a company that had started as a domestically focused merger was running scheduled services across oceans.

The expansion was deliberate and wide-ranging: regular sailings linked Kobe and Yokohama with South America, Batavia, Melbourne, and Cape Town, alongside frequent crossings to San Francisco and Seattle. On its fastest services, NYK could get from Yokohama to Seattle in about ten days, and to Europe in roughly a month. That’s not just scale—it’s reliability. And in shipping, reliability is the product.

Then came 1914, and a new piece of global infrastructure that rewired trade routes overnight: the Panama Canal. NYK didn’t watch from the sidelines. That same year, Tokushima Maru became the first Japanese ship to pass through the newly opened canal. Two years later, NYK began a liner service to New York via Panama. For Japan, this was a flex—proof that its flag could run the same global circuits as the Western giants.

NYK also grew the old-fashioned way: by buying its way into important routes. In 1926, it acquired the Pacific operations of Toyo Kisen Kaisha, a passenger line known for its San Francisco service. The deal expanded NYK’s reach across the Pacific and deepened its position as Japan’s premier international carrier.

At the same time, NYK stayed on the front edge of maritime technology. Starting in 1924, every new cargo ship it built was a motor ship. That shift—from steam to motor—wasn’t cosmetic; it was a bet on efficiency and operating economics. And it set a pattern that would define NYK’s best moments: when the industry changes, adopt early and build capability before everyone else is forced to.

The interwar period also became a kind of showcase era for NYK’s passenger business. The company built world-class ships for its Pacific routes, and they weren’t just transportation—they were floating hotels. Think polished wood interiors, stained-glass skylights, formal dining rooms, lounges, a library, a gift shop, a hair salon, comfortable cabins, and even a swimming pool on deck. They carried a strong Japanese atmosphere, and their first-class accommodations drew famous passengers including Albert Einstein, Charlie Chaplin and Paulette Goddard, Helen Keller, and Efrem Zimbalist.

But there was a darker side to the same story. By the late 1930s, NYK wasn’t simply thriving alongside Japan’s rise—it was intertwined with it. The company ran services connecting the home islands to Japan’s imperial holdings, including Korea, Karafuto (Sakhalin), Kwantung, Formosa (Taiwan), and the South Seas Mandate. In this period, a huge share of Japan’s merchant shipping capacity—liners, tankers, and more—moved under the NYK banner.

And that set up the tragedy at the heart of NYK’s pre-war peak: the very national importance that helped it grow also tied it tightly to the path Japan was about to take. The golden age was real. So was what came next.

IV. Catastrophe: World War II & Starting from Zero

In October 1941, the motor ship Hikawa Maru made a final, almost cinematic run into an American port—becoming the last NYK vessel to call in the United States before Japan and the U.S. went to war. She carried American refugees to Seattle. On the return voyage, she repatriated 400 Japanese nationals. Then the door slammed shut.

What followed was destruction on a scale that’s hard to hold in your head.

During World War II, NYK served as a logistics arm of the Japanese war effort, providing military transport and hospital ships for the Imperial Japanese Army and Navy. And when the U.S. submarine campaign went after Japan’s merchant fleet, it was devastatingly effective. NYK’s ships were right in the crosshairs.

By the time the war ended, only 37 NYK vessels remained, totaling 155,469 gross tons. The company had lost 185 vessels—more than 1.1 million gross tons—during the conflict. And the passenger fleet was almost completely wiped out: before the war, NYK operated 36 passenger ships; by Japan’s surrender in August 1945, only one survived. Hikawa Maru.

The company wasn’t just damaged. It was hollowed out.

And the losses didn’t stop when the shooting did. NYK’s surviving vessels and equipment were confiscated by Allied authorities as reparations, or taken by newly liberated Asian states in 1945 and 1946. Hikawa Maru herself was requisitioned by the Shipping Control Authority for the Japanese Merchant Marine and put to work repatriating Japanese soldiers and civilians from territories liberated from Japanese occupation.

Hikawa Maru had been converted into a hospital ship during the war—likely a key reason she made it through. The irony was sharp: the vessel refitted to save lives became the only passenger liner left to carry the company’s memory.

NYK had lost what mattered most in shipping: crews and vessels. It was, in the company’s own words, almost in a state of collapse. Offices and port facilities had been destroyed. Records were lost. And the accumulated human expertise of decades—captains, engineers, dispatchers—had been shattered along with the fleet.

But something else survived, too: a ruthless pragmatism. In the aftermath, NYK used whatever it had, however it could. The war had burned away the luxury of specialization, and that lesson lingered. In 1953, NYK refitted Hikawa Maru as an ocean liner and returned her to her pre-war Yokohama–Seattle route—an act that was part business decision, part statement: we’re still here.

Today, Hikawa Maru is permanently berthed at Yokohama’s Yamashita Park as a museum ship. She’s a physical reminder of what was lost—and of the thin thread that kept NYK from disappearing entirely.

V. The Postwar Reconstruction & Diversification Strategy

The occupation years were a period of humiliation for Japan—and a strange kind of second chance for its shipping industry. The same Americans who had helped wipe out Japan’s merchant fleet now needed ships to supply the occupation. And after 1950, as the Korean War ramped up, they needed even more capacity moving across the Pacific.

As the occupation neared its end, the United States reintroduced subsidization through aid programs. And with wartime demand accelerating recovery, occupation authorities helped Japanese shipping companies re-enter overseas routes and the international conference system that governed liner trade.

NYK, starting from the wreckage of just 37 surviving ships and nearly 200 lost, clawed its way back into international service by the early 1950s. Routes reopened. Schedules returned. The company was “back”—at least on paper.

Because financially, the 1950s were brutal. Like much of Japan’s shipping industry, NYK spent the decade bleeding. From 1956 through 1965, it ran at trading losses—a long stretch for any company, let alone one trying to rebuild a global fleet.

Then came the turning point: what the industry later called the “Mitsui Fight.” In the mid-1950s, NYK and OSK—working alongside European partners—waged an unsuccessful three-year campaign to keep Mitsui Senpaku KK out of the Far Eastern Freight Conference. Everyone took damage. But Mitsui survived, and NYK noticed why: tankers. Mitsui’s tanker business threw off enough strength to keep it afloat through a brutal competitive slugfest.

NYK took that lesson to heart. If one segment could carry you through a downturn in another, then the only rational strategy was diversification. NYK reorganized its business around three pillars—cargo liners, bulk carriers, and tankers—so the company would never again be hostage to a single market.

At the same time, Japan’s government was steering the entire industry toward consolidation, tying merger policy to increased subsidization. In that environment, NYK merged with Mitsubishi Kaiun KK, a division within Mitsubishi Corporation. Rival lines followed their own path: OSK and Mitsui Senpaku combined to form Mitsui O.S.K. Lines, Ltd.

And even as the industry consolidated, another, bigger shift was gathering force: containerization. The government promoted it by supporting companies that formed container groupings, and NYK moved early—working with Matson Navigation of San Francisco to introduce containers on Pacific routes. Alongside containers, NYK pushed its broader diversification agenda too, building tankers, ore carriers, and growing a specialized fleet for automobiles.

Containerization was the kind of technological reset that only happens once in a generation. Suddenly, ships could be loaded and unloaded in hours instead of days. Damage and theft dropped. Port work was transformed. As passenger demand faded in the 1960s, NYK leaned hard into cargo—and in 1968 it ran Japan’s first container ship, Hakone Maru, on a California route, then expanded container services to more ports soon after.

The move into car carriers was just as well-timed. As Japan’s auto industry surged through the 1960s and 1970s, NYK built roll-on/roll-off vessels designed to move vehicles efficiently at scale—carrying Toyota, Nissan, and Honda exports to markets around the world. Over time, that bet would grow into a defining advantage: NYK became the world’s largest car carrier by fleet capacity.

The postwar era is where modern NYK really takes shape. The company didn’t just rebuild what it had lost—it rewired itself for survival: learn from competitors, spread risk across businesses, and embrace the technologies that rewrote the economics of shipping. And in the background, Japan Inc. played its part—not as a side note, but as a critical force. For NYK, alignment between government policy and corporate strategy wasn’t window dressing. It was the difference between surviving the postwar decades and disappearing into them.

VI. The 1980s-90s: Yen Shock, Restructuring & Crystal Cruises

In 1985, the Plaza Accord landed like a torpedo in the middle of Japan’s export machine. The yen surged against the dollar, and for shipping that wasn’t an abstract macro story—it hit right where it hurts: costs. Crews and overhead were paid in yen. Revenues were often earned in dollars. Overnight, Japanese operators looked expensive next to competitors staffing ships with lower-cost international labor.

NYK didn’t try to tough it out with minor tweaks. It pushed to multinationalize its crews and began remaking itself into something broader than a shipping line: a comprehensive logistics group built on top of its international shipping footprint.

It also cut deep to stay competitive. One of the most consequential moves was spinning off internal functions that had traditionally lived inside the company. Between 1987 and 1991, NYK carved out areas like accounting and information systems into new subsidiaries. The result was stark: the company reduced its employee count by about 30 percent while keeping the business running. It was painful—but it bought NYK time, flexibility, and cost structure in a world that had abruptly changed.

Just as important was what NYK didn’t do. Years earlier, in 1975, it had already started reducing exposure to the tanker business—even though tankers were still throwing off profits. That kind of decision is exceptionally hard: walking away from what’s working because you can see the cycle turning. In the 1980s, when several Japanese companies that stayed aggressive in oil tankers went bankrupt, NYK’s earlier pullback looked less like caution and more like survival instinct. It kept diversifying instead, including ordering LNG tankers and expanding its car carrier fleet to serve the growing flow of vehicles to North America.

Through all of this, NYK still had a profitable base in container shipping. That steady foundation—combined with cost restructuring and a broader portfolio—helped it remain Japan’s largest shipping company and generally its most profitable into the early 1990s. Then, in 1998, NYK merged with Showa Line Ltd., leaving Japan with four major shipping companies: NYK, Mitsui O.S.K. Lines, Kawasaki Kisen Kaisha, and Navix.

And then came the curveball diversification move that almost nobody would have predicted from a hard-nosed cargo carrier: luxury cruises.

In 1988, NYK founded Crystal Cruises, a premium cruise line headquartered in Los Angeles and aimed squarely at affluent travelers from North America and Europe. The idea was to deliver an experience comparable to high-end hotels—think Four Seasons or Ritz-Carlton standards, but at sea. The first ship, Crystal Harmony, entered service in July 1990 and made her maiden voyage from San Francisco to Alaska.

A year later, Crystal Harmony arrived in New York for the first time, in August 1991. Delivered at Nagasaki and christened in Los Angeles on July 20, 1990, she carried an extra layer of meaning beyond the champagne and ceremony: she was the first Japanese luxury liner to visit New York in forty years, since the early 1950s. For a company whose passenger fleet had been almost completely erased in the war, the moment was more than marketing. It was proof that NYK could re-enter a business it had once lost entirely—and do it at the very top of the market.

Crystal Cruises went on to become one of the most awarded luxury cruise lines in the world, consistently earning “World’s Best” recognition from travel publications.

NYK eventually exited the business at the right time. On March 3, 2015, it announced the sale of Crystal Cruises to Genting Hong Kong for US$550 million in cash, subject to certain adjustments—closing the loop on a diversification bet that had delivered decades of profitable operations and serious brand cachet.

The 1980s and 1990s were another NYK stress test: currency shock, labor cost inflation, and industry pressure that could have sunk a less adaptable operator. Instead, NYK came out leaner and more diversified—having proved, again, that its real core competence wasn’t any single category of ship. It was reinvention.

VII. Key Inflection Point: The Ocean Network Express (ONE) Merger (2016-2018)

This was the defining strategic decision of NYK’s modern era: a move that looked, at first glance, like surrender. In reality, it was a bid to stay alive in the part of shipping that was becoming hardest to survive.

The Context: Container Shipping’s Crisis

By the mid-2010s, container shipping was in a full-blown crisis. Too many ships were chasing too little demand across the major trade lanes. Prices collapsed. Margins went from thin to nonexistent, and even the biggest names were bleeding cash.

At the same time, the industry was consolidating fast. Over the prior decade and a half, the top 10 global shipping lines expanded their share from roughly half the market in 2010 to the vast majority by the mid-2020s. Container shipping had become a scale business: bigger fleets, denser networks, better utilization, lower unit costs. If you couldn’t keep up, you didn’t just underperform—you got squeezed out.

That was the trap for Japan’s three major container players: NYK, Mitsui O.S.K. Lines (MOL), and Kawasaki Kisen (K Line). Each was strong at home, respected globally, and too small to go toe-to-toe with the mega-carriers or with fast-consolidating, state-backed Chinese competition. In containers, they were being forced into a losing game.

The Bold Decision

So they did something radical. On Monday, October 31, 2016, NYK, MOL, and K Line agreed to merge their container shipping businesses by creating an entirely new joint venture—one that would also integrate their overseas terminal operations.

This wasn’t a conventional merger where one company absorbs another. It was closer to a clean carve-out. The three parents would keep their separate identities and keep running their other businesses—bulk, tankers, car carriers, logistics—but they would pool containers: ships, terminals, commercial teams, and operations.

The new company would be called Ocean Network Express—ONE. It would have its company headquarters in Tokyo, with a global business operations headquarters in Singapore, plus regional headquarters in the United Kingdom (London), the United States (Richmond, Virginia), Hong Kong, and Brazil (São Paulo). ONE began operations on April 1, 2018.

The ownership split reflected NYK’s larger footprint: NYK held 38%, while MOL and K Line each held 31%.

From the start, ONE was built to be a serious global player: more than 240 vessels, and container capacity on the order of roughly two million TEUs, serving customers across more than 120 countries.

Why Give Away Your Container Business?

Because containers had stopped rewarding mid-sized independence. Alone, each Japanese line was getting crushed between the mega-carriers with unmatched scale and newer fleets, and state-backed competitors willing to play a longer game. Together, they could create a carrier big enough to matter—ultimately forming the world’s sixth-largest container shipping company at launch—large enough to compete on major routes and negotiate from strength.

The Singapore operations headquarters was a deliberate choice. It put day-to-day decision-making closer to the center of gravity of global container trade, and it created a degree of operational separation from the three Japanese parents. To run it, they brought in CEO Jeremy Nixon, a British executive with deep industry experience, to lead the combined operation.

Early Struggles and Turnaround

On paper, the logic was airtight. In practice, the first year was rough.

ONE was established in 2017, and when it launched service in April 2018 it immediately ran into the classic integration landmines: three different IT systems, three different operating cultures, three different ways of handling customers and documentation. The result was real operational disruption—exactly the kind of thing shippers hate in a business where “reliable” is the whole product.

In fiscal year 2018, ONE posted a loss of $585 million.

But the recovery came quickly. By fiscal year 2019, ONE reported a profit of $105 million. The basic merger math started to show up: costs came down, utilization improved, the network got more efficient, and the unified commercial organization could win business from customers who cared less about the last dollar of price and more about consistency.

The key lesson of the ONE move is simple and uncomfortable: sometimes the best strategic play is knowing when to stop trying to win alone. NYK’s management saw that container shipping had turned into a scale game they couldn’t sustainably compete in as a standalone Japanese champion. So they gave up control to preserve relevance—and bought themselves a future.

VIII. The COVID Windfall: ONE Becomes a Cash Machine (2020-2023)

Nobody could have predicted what came next. COVID-19 initially looked like it would crush global trade. Instead, it triggered the biggest profit boom container shipping had ever seen—and NYK’s ONE structure put it in exactly the right place to catch it.

The Pandemic Supply Chain Chaos Creates a Bonanza

When the pandemic hit in early 2020, carriers prepared for a demand cliff. What arrived instead was a bizarre, lucrative mismatch: demand for physical goods surged just as the supply chain’s ability to move those goods seized up.

Consumers stuck at home shifted spending from travel and entertainment to stuff. Factories restarted unevenly. Ports ran short on labor. Containers piled up in the wrong places. Ships waited offshore for berths. Capacity existed in theory, but in practice it was tied in knots.

Freight rates did what they always do when supply is constrained and demand won’t quit: they exploded. Lanes that used to price containers in the hundreds of dollars jumped into the thousands, and then far beyond that.

ONE, like its peers, rode that wave hard in 2021 and 2022. And here’s the mind-bender: even though ONE carried about 20 percent less freight between 2019 and 2022, its revenue rose by almost 154 percent.

Less volume. Vastly more money. That’s what happens when pricing power shows up in an industry that usually has none.

For fiscal year 2022 (ending March 2022), ONE’s numbers were staggering. Revenue hit $30.1 billion, up from $14.4 billion the year before. EBITDA jumped to $18.2 billion, compared with $4.8 billion in FY2020. Net profit reached $16.7 billion, up from $3.4 billion the prior year.

These weren’t incremental improvements. They were the kind of results that permanently change what a company can fund, buy, and survive.

What This Meant for NYK

For NYK, this was the punchline to a strategy that had looked like retreat back in 2016. As ONE’s largest shareholder at 38%, NYK participated directly in the windfall through dividends.

And strategically, it validated the logic of the joint venture. By pooling container operations with rivals, NYK had a carrier with enough scale to monetize the boom—while the operational headaches and capital intensity of running a global liner network weren’t sitting entirely on NYK’s own balance sheet.

The move that critics framed as “giving up containers” suddenly looked like building the perfect vehicle for a once-in-a-generation payoff.

The Normalization

Of course, shipping cycles don’t end; they swing.

As congestion eased, consumers rotated spending back toward services, and a wave of new vessel deliveries hit the water, rates fell fast. ONE’s results came back to Earth. For FY2023, revenue dropped sharply to $14,536 million and net profit fell to $974 million, as cargo softened and excess capacity returned.

The boom had been real, but it wasn’t permanent.

Still, the temporary nature of the windfall doesn’t reduce its significance. The cash generated during the peak gave NYK breathing room and optionality—strengthening the company for the next downturn and funding what comes next.

And it reframes the big debate in the ONE story: luck versus skill. Did NYK engineer brilliance, or stumble into perfect timing? The most honest answer is both. The structure was smart: it created scale, lowered costs, and shared risk in a brutally cyclical business. The pandemic was luck: an external shock that happened to reward exactly what ONE was built to provide. But that’s the point—luck matters most when you’ve built something capable of taking advantage of it.

IX. The Modern NYK: Beyond Shipping (2020s & Future)

Today’s NYK is no longer just a shipping line riding the cycles of global trade. It has been turning itself into a broader logistics enterprise—one that wants to be relevant not only to how goods move, but to how the next era of energy and technology gets built.

Digital Transformation

On April 11, NYK was selected as a 2025 Digital Transformation Stock, or “DX Stock,” by Japan’s Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry, the Tokyo Stock Exchange, and Japan’s Information-Technology Promotion Agency. It was the third year in a row NYK received the designation—an unusually public signal that the company isn’t treating digital as a side project, but as a core capability.

NYK stood out among the 31 companies selected in 2025 for how directly it’s using technology to reshape its operating model. One example is HULL NUMBER ZERO, an integrated technology solution brand meant to commercialize NYK’s know-how in ship operations—especially the practical rollout of autonomous vessel technology.

The work is concrete and operational, not just buzzwords: using 3D models and digital drawings to streamline ship design and approvals; deploying SIMS3 ship information management systems to transmit IoT operating data from vessels to shore every minute; and adopting Starlink satellite communications to move more data, more reliably, at sea.

And then there’s the most NYK version of “adjacent innovation” imaginable: research and development for recovering reusable rockets at sea. It’s far from container lanes and car carriers, but it fits the company’s core competency—operating complex, safety-critical missions on the ocean.

ESG & Decarbonization Push

If digital is about how NYK runs, decarbonization is about whether shipping can keep running at all under the next wave of regulation and customer pressure. The International Maritime Organization is tightening standards, and major shippers increasingly want low-carbon transportation they can actually claim in their own emissions reporting. NYK has chosen to push forward rather than wait.

On August 23, NYK and IHI Power Systems Co., Ltd., in cooperation with Nippon Kaiji Kyokai (ClassNK), completed the ammonia-fueled tugboat Sakigake—the world’s first ammonia-fueled vessel for commercial use. In August 2024, that tugboat entered service in Tokyo Bay. The project was developed as part of a Green Innovation (GI) Fund Project of the New Energy and Industrial Technology Development Organization (NEDO).

Ammonia matters because, when burned, it produces no carbon dioxide. If it can be scaled from tugboats to large oceangoing ships, it offers a credible pathway to truly zero-carbon shipping. NYK is trying to be early to that learning curve.

The company has set targets to reduce scope 1 emissions intensity by 30% by 2030, and to reach scope 1 net-zero by 2050 for its shipping operations. Alongside that, NYK is pursuing renewable energy projects as future core businesses—building hydrogen and ammonia supply chains and positioning itself as an “infrastructure carrier” across Japan’s offshore wind power value chain.

In the nearer term, the company is focused on switching to LNG-fueled RORO vessels, which emit less CO2 than conventional heavy-oil engines, with 20 new LNG-fueled RORO vessels scheduled for delivery by 2028. And the stated endgame is clear: as soon as technology matures, NYK intends to move from LNG to zero-emission vessels powered by low-emission marine fuels such as hydrogen and ammonia.

The Medium-Term Strategy: "Sail Green, Drive Transformations 2026"

NYK has wrapped these moves into a single medium-term management plan: “Sail Green, Drive Transformations 2026 - A Passion for Planetary Wellbeing.” Positioned as a four-year action plan built on a long-term forecast of the business environment, it puts ESG at the center of how the company expects to grow toward its 2030 vision: “We go beyond the scope of a comprehensive global logistics enterprise to co-create value required for the future by advancing our core business and growing new ones.”

Released in March 2023, the plan is structured around two core business strategies—AX (ambidextrous management) and BX (business transformation)—supported by three enabling strategies: CX (human resources, organization, and group-management transformation), DX (digital transformation), and EX (energy transformation). DX is explicitly framed as the engine that makes the other transformations possible.

Financially, NYK plans to invest approximately 1.2 trillion yen through fiscal 2026, while returning capital to shareholders with an emphasis on improving capital efficiency.

NYK President Takaya Soga has said that steady progress under the plan has materially improved the quality of profits, and that—supported by advances in environmental initiatives, digital transformation, and business structure reforms—the company has revised upward its profit forecast for fiscal 2030.

The through-line is resilience by design. NYK argues it has already made itself less vulnerable to shocks by restructuring its liner trade business through the creation of Ocean Network Express (ONE) and by expanding businesses with reliable earning power. The next phase is portfolio management: building a system that can generate profits more steadily through cycles, while also tackling the social and industrial challenges that will define shipping’s next century.

X. Investment Analysis: Bull Case, Bear Case, and What to Watch

NYK is a classic “hard asset, hard cycle” business—except it isn’t just one business anymore. It’s a portfolio: cars, bulk, energy transport, logistics, and a big stake in ONE. That mix is the entire point. It can soften the blows when one market turns, but it also means the company’s results are pulled by several different tides at once.

Bull Case

The upside story for NYK rests on a few big ideas:

-

Diversification that actually matters: NYK isn’t a pure-play container carrier. The car business, dry bulk, energy transport, logistics, and the ONE stake give it multiple earnings engines. When container rates fell in 2023, the automotive and LNG-related businesses helped stabilize the picture.

-

A dominant position in car carriers: NYK’s RORO division is the world’s largest ocean car carrier. Its fleet has just under 600,000 cars of capacity—about 16% of global car transportation capacity. That kind of scale in a specialized niche creates real barriers to entry and tends to attract sticky, long-term customers.

-

ONE as upside without full exposure: NYK’s 38% stake in ONE gives it leverage to a container upswing without having to run the entire container operation alone. If geopolitical disruption—like Red Sea rerouting or broader Suez uncertainty—keeps absorbing capacity, ONE could see an earnings lift.

-

Early positioning for decarbonization: NYK’s work in ammonia-fueled vessels and LNG transport puts it on the front edge of a world that is steadily tightening environmental rules. Its medium-term plan, Sail Green, Drive Transformations 2026 — A Passion for Planetary Wellbeing, is designed to strengthen sustainability management and push forward non-financial targets alongside the business.

-

Digital execution, not just digital talk: Being named a DX Stock three years in a row suggests NYK is building genuine operational capabilities that can translate into efficiency gains and, potentially, new service models.

Bear Case

The downside story is the stuff that never goes away in shipping:

-

Relentless cyclicality: Shipping is still one of the most volatile industries on earth. The pandemic boom showed how high profits can go; the normalization showed how fast they can come back down. New vessel deliveries and weaker demand can compress earnings quickly.

-

Meaningful influence from an asset NYK doesn’t control: The ONE stake cuts both ways. It’s optionality, but it also means NYK’s results can swing with ONE’s performance even though NYK isn’t in the driver’s seat. And when freight rates fall year-on-year, profit at ONE falls with them.

-

Geopolitics and policy shocks: Trade tensions, sanctions, regional conflicts, and canal disruptions are not edge cases in shipping—they’re part of the landscape. NYK has revised its full-year net income forecast downward by JPY30.0bn to JPY210.0bn due to economic trends linked to tariff measures and port fees introduced in the United States and China. External variables to watch include whether the Suez Canal reopens to normal traffic and how future greenhouse gas emissions rules are applied to vessels.

-

The cost of going green: Moving early on decarbonization can create advantage, but it requires capital. Ammonia- and methanol-fueled vessels cost more than conventional ships, and the fueling infrastructure is still being built. Being early can mean paying to learn.

-

Home-market gravity: Japan is a mature, aging economy. While NYK is global, its roots and many relationships are domestic—so growth depends heavily on competing and expanding in tough international markets.

Porter’s Five Forces Analysis

-

Threat of New Entrants: Low to moderate. Shipping demands massive capital and specialized operational expertise. But Chinese, state-backed carriers have shown that motivated entrants can still gain share.

-

Bargaining Power of Suppliers: Moderate. Shipyards, fuel suppliers, and equipment makers can have leverage, especially when capacity is tight. NYK’s scale provides some counterweight.

-

Bargaining Power of Buyers: High. Large shippers can negotiate hard and play carriers against each other. Container shipping in particular offers limited differentiation.

-

Threat of Substitutes: Low. For intercontinental freight, there’s no practical substitute to ocean shipping; air freight only serves premium slices of cargo.

-

Industry Rivalry: Intense. Container shipping has a long history of brutal price competition and forced consolidation. ONE itself was largely a defensive response to this dynamic.

Hamilton Helmer’s 7 Powers Framework

-

Scale Economies: Strong in container shipping (hence ONE), and meaningful in the specialized RORO niche where NYK is a leader.

-

Network Effects: Limited direct network effects, but participation in major alliances improves connectivity and reach.

-

Counter-Positioning: NYK’s push into ammonia fuel and autonomous operations could become counter-positioning if competitors move slower.

-

Switching Costs: Low for commodity freight; higher when NYK provides more integrated, specialized logistics.

-

Branding: Limited in bulk shipping; historically more relevant in the luxury cruise business (which NYK has sold).

-

Cornered Resources: Long-standing relationships with Japanese automakers for RORO services function as a quasi-cornered resource.

-

Process Power: Decades of operating discipline, safety culture, and customer relationships create real accumulated advantage.

Key KPIs to Watch

If you’re tracking NYK over time, a few indicators do most of the explaining:

-

ONE profit contribution: ONE is a major driver of NYK’s earnings. Watching ONE’s quarterly performance and dividend distributions is often the clearest read on near-term profit power.

-

RORO utilization and rates: The automotive segment tends to be NYK’s most stable. Vehicle production levels at Japanese automakers and RORO charter rates are key signals.

-

ROIC vs. cost of capital: NYK’s medium-term plan targets ROIC of at least 6.5%. Whether it can consistently earn above its cost of capital is what determines long-run value creation.

Regulatory and Legal Considerations

NYK has been subject to class civil lawsuits in several regions seeking damages and other remedies, tied to allegations of conspiracy to fix shipping prices in marine transportation of assembled automobiles. The company states that it is difficult to reasonably predict outcomes at present.

These are legacy issues, but they remain worth monitoring. NYK indicates there has been no significant change from prior disclosures.

XI. Conclusion: The Art of Corporate Survival

Nippon Yusen Kaisha has now made it through 140 years—longer than many modern institutions have been around to measure it. It lived through the transition from sail to steam to motor, and then into the era of LNG and ammonia. It evolved from carrying mail and passengers to moving the standardized steel boxes that power globalization. It operated through imperial Japan, defeat and occupation, the postwar economic miracle, and the slow grind of a mature economy.

So what explains that kind of longevity in one of the most unforgiving industries on Earth?

First: adaptability. NYK hasn’t just “optimized” at the margins. When the world changed, it repeatedly rewired the company. Postwar diversification into tankers and bulk. The hard pivot into containerization. The unexpected leap into luxury cruising with Crystal. The decision to carve out containers into ONE. These weren’t small adjustments—they were identity-level shifts.

Second: timing. NYK has been unusually good at knowing when to step back while a business still looked attractive. Cutting tanker exposure in 1975 before the damage hit the rest of the industry. Forming ONE before the pandemic turned containers into a profit geyser. Selling Crystal Cruises in 2015, years before Genting’s ownership ended in bankruptcy. In shipping, where cycles punish denial, timing can be the difference between a drawdown and a death spiral.

Third: balance. NYK built a portfolio on purpose—different cargoes, different end markets, different kinds of assets. That diversification doesn’t eliminate cyclicality, but it can blunt it. When containers slump, cars can hold up. When dry bulk softens, energy transport can carry the year. It’s not a guarantee. It’s a design choice.

Fourth: government relationships. From Meiji-era nation-building to postwar reconstruction to today’s decarbonization partnerships, NYK has consistently operated in alignment with Japan’s strategic needs. That’s not a footnote. In a country where maritime transport is economic security, being a reliable national shipping champion has repeatedly mattered.

The ONE decision crystallized all of these lessons. Container shipping had become a scale game the Japanese carriers couldn’t win alone without bleeding out. NYK chose cooperation over pride: pooling assets with rivals, accepting minority ownership, and trading control for competitiveness. It looked like retreat—until it proved to be survival with leverage.

As of December 25, 2025, NYK is at yet another inflection point. Decarbonization will demand massive investment and may reorder the competitive landscape. Digital transformation will create both efficiency gains and new operational risks. Geopolitics will keep rewriting trade lanes that used to feel permanent.

But if there’s one takeaway from 140 years of NYK history, it’s that the company has a track record of meeting discontinuities with reinvention. The operator that lost 185 ships in World War II and still rebuilt into a fleet counted in the hundreds; that moved from mail to containers to integrated logistics; that repeatedly chose survival over nostalgia—has earned a certain credibility when it says it will adapt again.

For long-term investors, NYK is not a smooth story. It’s a cyclical, capital-intensive business exposed to shocks it can’t control. But it’s also something rarer than it looks: a company with real strength in specialized segments like car carriers, upside participation in containers through ONE without bearing the full operational burden, and a serious attempt to lead rather than follow on the next era of shipping technology. It may not suit anyone looking for a quick win. For those willing to hold through the cycle, NYK has been, for 140 years, a case study in how to build a company that lasts.

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music