Hankyu Hanshin Holdings: The Railroad Tycoon Who Invented Modern Japan

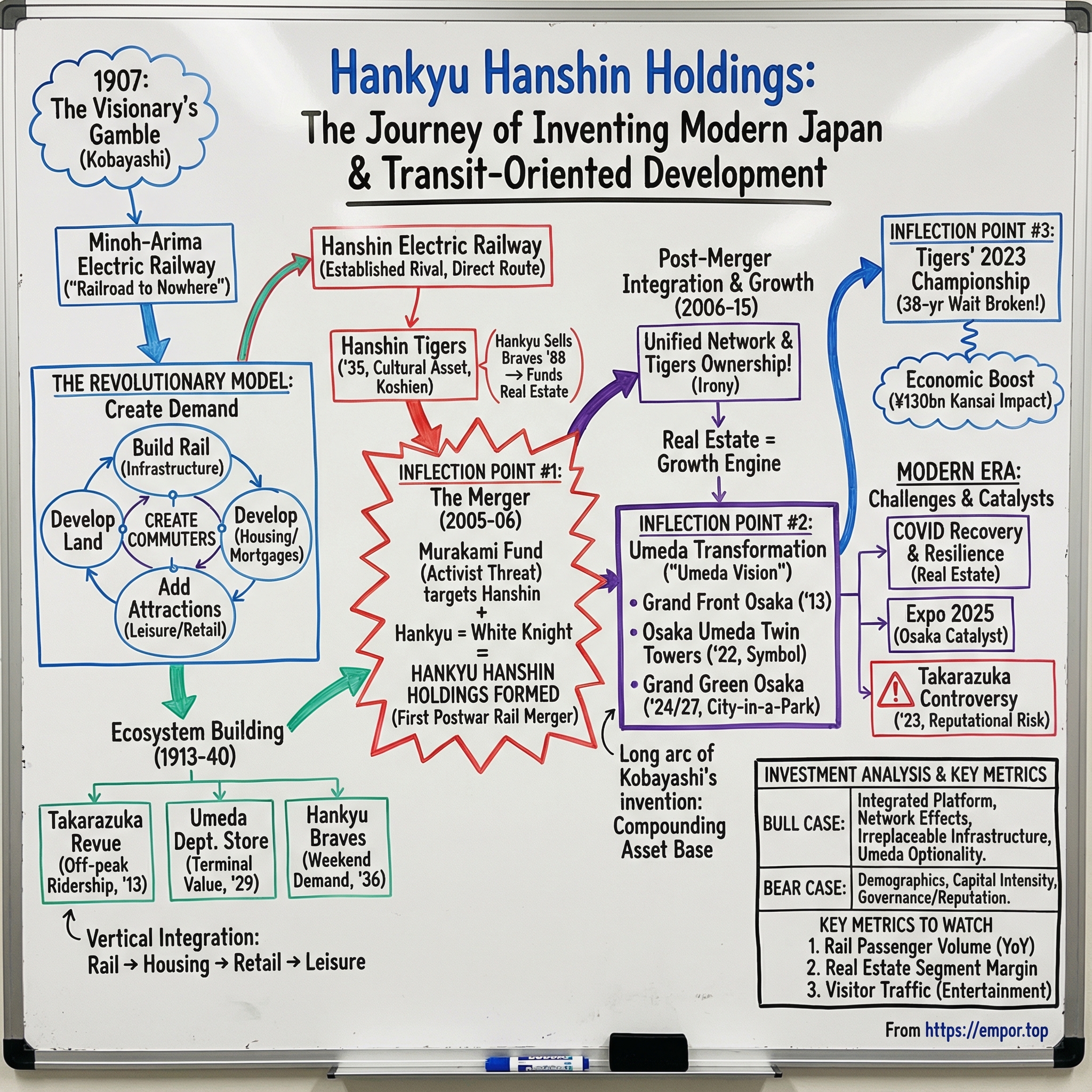

I. Introduction: A Blueprint for Cities Before "Transit-Oriented Development" Had a Name

Picture Osaka in 1907. Japan had just come out of the Russo-Japanese War. The Meiji era was in full swing, and a once-feudal country was sprinting into modern industry. And in the middle of all that momentum, a 34-year-old former banker decided to do something that, on paper, looked absurd: build an electric railway out through empty farmland.

Ichizō Kobayashi wasn’t trying to win a race to connect two obvious population centers. He was trying to manufacture a new one.

Because Kobayashi didn’t just want track. He wanted a world attached to it: neighborhoods that would fill the cars every morning, leisure destinations that would fill them on weekends, shops that would capture the spending once passengers arrived. Houses, department stores, amusement, and, yes, an all-female theater troupe. To rivals like the already-established Hanshin Electric Railway—running the more sensible, high-demand corridor between Osaka and Kobe—this looked like fantasy. Who, exactly, was going to ride a train to nowhere?

That question is the hook. The answer is the company we’re talking about today.

Over the next century, Kobayashi’s “railroad to nowhere” grew into Hankyu Hanshin Holdings: a sprawling Japanese holding company with major businesses in urban transportation, real estate, entertainment, information and communication technology, travel, and international transportation. Under its umbrella sit household names in Kansai life—Hankyu Railway, Hanshin Electric Railway, and entertainment assets like Toho, alongside a web of affiliates that turn stations into city centers.

And here’s the twist that makes Hankyu Hanshin different from how most people think about railroads: the trains may be the heartbeat, but they aren’t the whole body. The transportation segment—Hankyu and Hanshin—still anchors the group’s cash generation. Yet by fiscal 2024, the majority of revenue was coming from everything built around the rails. That isn’t diversification that happened later. It’s the point.

Kobayashi’s playbook was simple and radical: don’t just serve demand—create it. Build the railroad. Develop the land around the stations. Give people reasons to ride: places to live, things to do, and destinations worth traveling for. Capture value across the entire ecosystem, not just the fare box. In the early 20th century, as Japan’s private railways began pairing track with town-building, this approach became the model. Today, planners and academics study it under the name “transit-oriented development.” Kobayashi was doing it decades before the phrase existed.

So this isn’t just a corporate biography. It’s the story of a company that helped write the rulebook for how private enterprise can shape a city—then spent a century proving the rulebook works. Along the way, it survives wartime reorganization, rebuilds in the postwar boom, and later gets pulled into a hostile takeover drama that becomes a turning point in modern Japanese corporate governance. It ends up owning one of Japan’s most culturally loaded assets, the Hanshin Tigers—whose championship run in 2023 didn’t just make fans cry in the streets, it moved real economic activity across Kansai. And it places itself at the center of one of Japan’s biggest urban redevelopment bets as Osaka heads toward Expo 2025.

If you’re an investor, Hankyu Hanshin is a rare case study in what patient infrastructure ownership can become when it’s paired with imagination: you own the platform, you own the land, you own the destinations—and you can make the whole system compound over generations.

This is the blueprint. And it starts with a banker, a stretch of farmland, and a train that supposedly had nowhere to go.

II. The Visionary: Ichizō Kobayashi & The Birth of an Empire (1907-1920)

A Banker's Frustrated Vision

Ichizō Kobayashi (January 3, 1873 – January 25, 1957), sometimes writing under the pseudonym Itsuō, would eventually become one of Japan’s defining industrialists and politicians. He founded Hankyu Railway, the Takarazuka Revue, and Toho.

But he didn’t start as a tycoon. He started as an employee—inside the machine.

Kobayashi was born in Nirasaki, Yamanashi Prefecture, in 1873, and graduated from Keio Gijuku before joining Mitsui Bank in 1893. He was part of the cohort of Keio graduates recruited by Hikojiro Nakamigawa into the Mitsui orbit, rising as one of prewar Japan’s leading salaried managers.

He grew up within sight of Mount Fuji, and—according to Mukōyama Tateo, a visiting professor at the University of Yamanashi who researched Kobayashi’s life—came from a wealthy merchant family. He also developed an early love of drama, a detail that feels quaint now but will end up mattering far more than anyone could have guessed.

At Mitsui, Kobayashi spent fourteen years watching how money and people moved. He saw land values lift around stations. He saw commuting become a daily ritual. And he noticed a mismatch that others treated as “just the way things are”: cities were swelling, but private housing remained cramped and rental-heavy. Beyond the dense core, the “suburbs” were still basically farmland.

In 1907, he left Mitsui Bank. And instead of taking the safe path—another prestigious post in finance—he stepped into a new venture near Osaka: the establishment of the Minoh-Arima Electric Railway, the company that would later become Hankyu Railway.

The "Railroad to Nowhere" Gamble

The Minoh-Arima Electric Railway, with Kobayashi as managing director, became the first case in Japan of an electric railway company running real estate as part of its business. It was founded in October 1907 and later changed its name to Hanshin Express Electric Railway (Hankyu Railway) in February 1918.

From the beginning, it looked like a tough sell. The company had rights to build a line connecting Osaka (Umeda) toward places like Minoh, Arima, Takarazuka, and Nishinomiya—but the timing was brutal. A post–Russo-Japanese War recession made financing difficult, and the projected passenger numbers were low because, well, hardly anyone lived along the route.

And this is where the story sharpens into a choice.

Hanshin Electric Railway—the already-established rival—had opened a line linking Osaka and Kobe in 1905. That was the obvious corridor: two major cities, guaranteed demand, steady ridership. Hanshin’s model was traditional: connect what already exists and monetize the flow.

Kobayashi’s model asked for faith. He wasn’t connecting two strong magnets. He was trying to manufacture one.

In 1907, the Minoo Arima Electric Tramway Company—one of the forerunners of today’s Hankyu Hanshin Holdings—was established under Kobayashi. On March 10, 1910, it opened the lines from Umeda to Takarazuka (the Takarazuka Main Line) and from Ishibashi to Minoo (the Minoo Line).

Today, an express train from Osaka’s Umeda Station reaches Takarazuka in around half an hour, and fans flock there because it’s synonymous with the Takarazuka Revue. But in 1910, Takarazuka wasn’t a destination. It was a village, with a so-so hot springs resort on one bank of the Muko River. On the other bank—where the Takarazuka Grand Theater would later stand—there were only scattered farmhouses and a quiet pine forest stretching along the water.

A railway to nowhere, indeed.

The Revolutionary Business Model: Creating Demand

Kobayashi’s response to the “nobody lives there” problem wasn’t to abandon the line. It was to treat that emptiness as the opportunity.

To make the railway work, he concluded the company had to pair transportation with housing development along the route. This wasn’t a side hustle. It was the strategy: build one large commercial sphere by capturing passengers not just through timetables, but through town-building. He began buying up land and shaping the area around stations into places people would actually choose to live.

In practical terms, Kobayashi pioneered an integrated model—railway development combined with real estate and urban planning—that accelerated suburban growth in the Kansai region. He pushed the railway into underdeveloped areas north of Osaka and Kobe, then made those areas develop by offering affordable residential communities along the tracks.

The real masterstroke was financial: he expanded the business beyond transporting riders and introduced Japan’s first mortgage system. He wasn’t merely selling houses; he was creating homeowners—people with both the incentive and the ability to commute.

And once you see the loop, you can’t unsee it. The company could own the land, develop the housing, provide the financing, and then capture recurring fare revenue for decades. A house wasn’t just a real estate transaction—it was a long-lived stream of riders.

Kobayashi then layered in attractions that gave people reasons to ride even when they weren’t commuting, building out leisure and entertainment along the line. Later, the model would extend to the department store at the terminal. Today it can sound obvious, but at the time it was a new kind of thinking: not a railway company with some extra businesses, but a system designed to generate its own demand.

The expansion continued. On July 16, 1920, the Kobe Main Line opened from Jūsō to Kobe (later renamed Kamitsutsui), along with the Itami Line from Tsukaguchi to Itami. Hankyu now wasn’t just pulling Osaka outward into the suburbs—it was stitching together a major corridor between Osaka and Kobe, a route that would generate passenger revenue for generations.

By 1920, Kobayashi had done the hard part: he proved the mechanism worked. The “railroad to nowhere” created its own destinations. And those destinations created the riders the railroad needed.

III. Building an Ecosystem: Entertainment, Department Stores & Baseball (1913-1940)

The Takarazuka Revue: Customer Acquisition as Art Form

Once Kobayashi proved he could create commuters, he went after the next problem: trains are busiest twice a day. Mornings and evenings. The rest of the time, your expensive infrastructure is sitting there, underused.

His solution was wonderfully direct. Give people a reason to ride for fun.

In 1913, Kobayashi founded the Takarazuka Revue in Takarazuka, the terminus of his line from Osaka. Takarazuka already had a hot springs reputation, and Kobayashi saw it as the perfect place to add an attraction that would turn a modest destination into an irresistible one. Western-style song and dance was catching on, and Kobayashi viewed kabuki as old and elitist. So he gambled on something new: an all-female theater troupe aimed at the general public.

The first performance came in 1914. And the origin story has the kind of “you can’t make this up” energy that only real history delivers. Kobayashi’s Takarazuka New Spa was drawing crowds for its baths and impressive facilities, but the attached indoor pool at the “Paradise” leisure center flopped. As Kobayashi later wrote in his autobiography, “As the pool received no direct sunlight, it was too cold to swim in for even five minutes.”

So he repurposed it. If you can’t fill a pool with swimmers, fill it with an audience.

In 1913 he hired 16 girls in their mid-teens. The next year, they staged three performances as the Takarazuka Girls’ Revue—free of charge—inside a theater converted from that failed pool in a building attached to the resort.

Kobayashi even had a marketing comp in mind. He’d watched Mitsukoshi Department Store in Tokyo use a youth ensemble—teenage boy musicians in Western-style outfits and feathered hats—to draw attention and customers. It worked. Kobayashi later wrote that for Takarazuka New Spa, “we imitated this group, and with guidance from Mitsukoshi set up a girls’ musical theater group.”

What started as a ridership hack became a cultural institution. Within a decade, the troupe was popular enough to get its own dedicated theater in Takarazuka, the Dai Gekijō—literally, the “Grand Theater.” In 1934 it expanded to Tokyo with the Tokyo Takarazuka Theater, which later underwent a renewal in 2001.

Long after Kobayashi’s death, the engine kept running. Hit productions like the 1974 premiere of The Rose of Versailles drew massive audiences over their runs, still sending people onto Hankyu trains and into the surrounding hotels and shops.

Today, the Takarazuka Revue Company operates as a subsidiary within Hankyu Hanshin Holdings, with the parent providing financial oversight, budgeting, and strategic direction. In other words: it’s still doing what Kobayashi designed it to do—fitting neatly into a broader entertainment portfolio and continuing to justify the trip.

The World's First Railway Terminal Department Store

If Takarazuka was about creating reasons to ride to the end of the line, Kobayashi’s next move was about capturing value at the beginning of it.

In 1925, Hankyu Market—what would become the predecessor to Hankyu Department Store—opened in Umeda as a directly managed market division of Hankyu Corporation. Then, in April 1929, Kobayashi made the leap: Hankyu Department Store, the world’s first railway terminal department store.

The idea sounds inevitable now, but it wasn’t then. Many Japanese department stores had grown out of kimono shops, and elsewhere in the world, department stores weren’t directly run by railway companies. Hankyu flipped that logic. With two floors underground and eight above ground, the Umeda store didn’t just attract shoppers—it helped define Umeda as a destination in its own right.

Kobayashi understood something almost embarrassingly obvious once you say it out loud: a railway terminal isn’t just where trains stop. It’s where people concentrate. Tens of thousands of commuters pass through, every day, on a schedule. That foot traffic is an asset. Why let independent merchants capture it when you can build the retail right into the flow?

And he was intentional about who the store was for. The Hankyū Department Store at Umeda included an affordable café on the top floor, serving popular dishes like curry rice. That pricing was strategy, not generosity. Kobayashi wanted middle-class commuters to feel welcomed, to treat the store as part of their routine—and to associate Hankyu with modern life that was both aspirational and accessible.

Professional Baseball: Entertainment as Infrastructure

Kobayashi didn’t stop at theater and shopping. In 1936, Hankyu established a professional baseball team, and in 1937 it completed Nishinomiya Stadium as the team’s home field, located near Nishinomiya-Kitaguchi Station.

Same playbook, different kind of crowd. Baseball was still young as a professional sport in Japan in the 1930s, and it was perfect weekend programming: families, groups of friends, day trips. Put the stadium on your line, and the ride to the game becomes part of the product.

The team later became known as the Hankyu Braves (named in 1947). They played through the 1988 season and became predecessors of today’s Orix Buffaloes. Their eventual sale would become important to Hankyu’s later development—but we’ll come back to that.

By 1940, Kobayashi had effectively built a vertically integrated lifestyle system. Transportation fed housing. Housing fed commuters. Commuters fed retail. Retail and attractions fed off-peak ridership. Families rode Hankyu trains into Umeda, shopped at Hankyu, went to games at a Hankyu stadium, and took trips to see a Hankyu-created revue.

This was the real invention: not a railway with side businesses, but an ecosystem where each part existed to strengthen the rest. Hankyu didn’t just move people. It designed the reasons they moved in the first place.

IV. War, Rebuilding & The Kobayashi Legacy (1940-1970)

Wartime: The Forced Merger Era

Japan’s slide into World War II didn’t just reshape borders and battlefields. It reorganized entire industries from the top down—and the private railways weren’t exempt.

On October 1, 1943, under government order, Hanshin Kyūkō and Keihan Electric Railway were merged and renamed Keihanshin Kyūkō Railway Company. The combined network bundled together a wide set of lines, including the Keihan Main Line, the Uji Line, the Shinkeihan Line (today’s Kyoto Main Line), the Senriyama Line (today’s Senri Line), the Jūsō Line (now part of the Kyoto Main Line), the Arashiyama Line, the Keishin Line, and the Ishiyama Sakamoto Line.

Then, after the war, the structure partially unwound. On December 1, 1949, the Keihan Main Line, the Katano Line, the Uji Line, the Keishin Line, and the Ishiyama-Sakamoto Line were split off into the newly established Keihan Electric Railway Co., Ltd. Keihan was back—but not fully. It returned smaller than it had been before the 1943 merger, because Keihanshin retained the Shinkeihan Line and its branches.

And while the company’s lines were being rearranged by decree, Kobayashi himself was being pulled into a very different kind of service.

In 1939, Emperor Hirohito appointed Ichizō Kobayashi to the House of Peers through imperial nomination—a route reserved for nationally prominent figures in business, academia, and culture. It was a recognition of what he’d built: a major private enterprise, and a new template for city-making through rail, housing, and entertainment.

But the war years quickly turned that prominence into state utility. In 1940, Kobayashi was commissioned by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs to lead a diplomatic mission to the Dutch East Indies. The negotiations were about oil. On September 12, 1940, a Japanese delegation of 24—led by Kobayashi in his capacity as Minister of Commerce and Industry—arrived in Batavia to renegotiate political and economic relations between Japan and the Dutch East Indies.

It’s one of those historical jolts: the man who built a railway ecosystem around leisure and culture was now in the machinery of wartime diplomacy, trying to secure the fuel that powered Japan’s military ambitions. Corporate leadership in that era didn’t sit at arm’s length from the state. It was often absorbed by it.

The Founder's Death and Second Generation

Postwar Japan brought another kind of forced change—less about consolidation, more about reorganization. In April 1947, Hankyu Department Store separated from Hankyu Corporation to become Hankyu Department Stores, Inc. The occupation-era restructuring rippled through Japanese industry, but the core idea Kobayashi pioneered—rail plus real estate plus destinations—didn’t disappear. It adapted.

Kobayashi died in January 1957, closing the book on a fifty-year run that helped define how modern Japanese cities would grow. That same year, in October, the Itsuō Art Museum opened in Ikeda, Osaka, to house his art collection—an echo of the personal love of culture that had always been intertwined with his business instincts.

Leadership passed to the next generation, and the mission stayed familiar: develop around the stations. Only now the backdrop was Japan’s postwar economic surge, when housing demand exploded and retail modernized at speed. The company didn’t need to invent the suburbs anymore. It needed to scale them.

V. The Parallel Story: Hanshin Electric Railway (1899-2005)

The Other Kansai Railway Giant

To understand the 2006 merger that created Hankyu Hanshin Holdings, you have to understand the other giant in the story: Hanshin Electric Railway. This was the company Kobayashi deliberately positioned against—and, decades later, the one Hankyu would ultimately absorb.

Hanshin came first in the corridor that mattered most. In 1905, it opened a line linking Osaka and Kobe, a route that was instantly more intuitive, and far more heavily traveled, than Hankyu’s early bet from Osaka out toward Takarazuka. If Kobayashi’s line was a leap of faith into farmland, Hanshin’s was the classic railway play: connect two established population centers and let demand do the work.

Both approaches succeeded. But they produced very different corporate DNA.

Hankyu was built around creating demand—real estate, attractions, retail, then riders. Hanshin’s position was simpler and, in its own way, just as powerful: sit on one of Japan’s densest urban arteries and focus on moving huge numbers of people reliably between two major cities. Over time, Hanshin did build out businesses around that core, including development around Umeda and assets like the Hanshin Department Store and leisure ventures. But at heart, it was anchored by the corridor.

And that corridor came with something else: a captive public audience. Which brings us to the asset that made Hanshin more than a railway company.

The Hanshin Tigers: Japan's Most Beloved Baseball Team

If Hankyu had the Braves, Hanshin had something far more culturally charged: the Tigers.

Founded in 1935, the Hanshin Tigers emerged in the earliest days of professional baseball in Japan. And they weren’t just any franchise playing in a generic venue. The team played at Koshien Stadium—built in 1924, the oldest stadium in Nippon Professional Baseball. In 1934, even Babe Ruth visited Koshien during a tour of Major League stars. That kind of history can’t be replicated with money. It has to be lived into.

Over time, Tigers fans became famous for the same qualities the team represented: intensity, loyalty, and identity. They’re often described as among the most dedicated fan bases in Japanese baseball, known to show up in overwhelming numbers even at away games.

And then there’s the rivalry that turns all of that emotion into a national story: Tigers versus Giants. In Japan, that matchup is the marquee rivalry—often compared to the biggest blood-feud pairings in American sports. Historically, the Giants held the edge in wins, but the deeper meaning for many fans ran beyond the standings. For working-class residents of Osaka and Kobe, the Tigers weren’t just a team. They were a statement: Kansai pride, and a perpetual chip on the shoulder directed at Tokyo and the establishment aura of the Giants.

For Hanshin, the Tigers became a crown jewel—an emotional asset with gravity that pulled attention, spending, and loyalty into the broader enterprise.

Selling the Hankyu Braves: Strategic Trade-Off

Meanwhile, Hankyu made a very different call about baseball.

Hankyu once owned a professional team known as the Hankyu Braves. In 1988, Hankyu sold the team to Orient Leasing Co., which later changed its name to Orix. The franchise became the Orix BlueWave and later the Orix Buffaloes. The sale was driven by capital allocation: then-president Kohei Kobayashi chose to fund redevelopment at Umeda Station and Nishinomiya-Kitaguchi Station instead of continuing to operate a baseball club.

From a purely financial perspective, the logic was straightforward. Hankyu was, at its core, a city-making machine, and real estate development around its flagship terminal was exactly the kind of investment that could compound for decades.

But the trade-off was real. In selling the Braves, Hankyu gave up something that doesn’t show up neatly on an income statement: a direct emotional tether to a mass audience. After 1988, the fans didn’t cheer for Hankyu anymore. They cheered for Orix.

And here’s the irony that makes the next chapter feel like fate: when Hankyu acquired Hanshin in 2006, it effectively re-entered baseball ownership—but not by rebuilding the old Braves. It did it by ending up with the far more culturally valuable franchise in Kansai: the Hanshin Tigers.

VI. INFLECTION POINT #1: The Murakami Fund Hostile Takeover Drama (2005-2006)

Enter Yoshiaki Murakami: Japan's First Activist Investor

This is the story of how an attempted hostile takeover of a regional railway company turned into a national scandal, triggered the first postwar merger between major private railways in Japan, and helped send the country’s most famous activist investor to jail.

Yoshiaki Murakami (born August 11, 1959) grew up in Osaka, went to the University of Tokyo, and joined the Ministry of International Trade and Industry—MITI, the forerunner of today’s METI. But he didn’t stay. Murakami decided he didn’t want to be a regulator. He wanted to be a player.

In 1999, he founded what became known as the Murakami Fund. The premise was simple: Japanese public companies, in his view, were mismanaged from the perspective of shareholders. They hoarded cash, sat on underused assets, earned weak returns, and were protected by comfortable corporate relationships that discouraged accountability. Murakami’s strategy was to buy meaningful stakes in companies he believed were undervalued relative to their cash and assets, then force the issue—loudly—through shareholder proposals and public pressure.

By 2006, the Murakami Fund had grown into a major force, managing about $5 billion.

Murakami cultivated a persona to match. He called himself the “professional of all professional players in the stock market,” and told a story about how early the obsession began. As a child, he was given money by his father—an executive in the trading business—to invest as a lesson. Murakami’s first pick was reportedly Sapporo Breweries, the maker of his father’s favorite beer. As a teenager, he devoured the Japan Company Handbook. The point wasn’t just that he invested young. It was that he grew up reading balance sheets the way other kids read comics.

That became his edge. Murakami would show up to meetings having studied the numbers, then bristle when executives seemed unfamiliar with their own financial statements. To him, that wasn’t a minor flaw. It was the whole problem. He later described leaving government service out of frustration, believing he could force change faster as an investor than as a bureaucrat.

His method was consistent: buy large stakes, demand reforms, and if management resisted, use publicity and leverage until they either yielded or the stock price moved enough for a profitable exit.

The Raid on Hanshin Electric Railway

By mid-2005, Murakami had picked his next target: Hanshin Electric Railway.

Hanshin’s leadership had watched its stock price rise and largely let it happen. Inside the company, the story was that the Hanshin Tigers’ performance was lifting the shares. But the real driver was Murakami steadily buying. By September 2005, the Murakami Fund had accumulated 26.67% of Hanshin’s stock and became a major shareholder.

Then it kept going. Over time, reporting put the fund’s position at around 40%, and by May 2006, it had reached 46.82%. Hanshin’s stock price climbed to around 1,200 yen per share—making it even harder for the Hanshin group to mount a financial defense against a hostile bid.

But the truly incendiary move wasn’t just buying the stake. It was what Murakami talked about doing with it.

He floated the idea of listing shares in the Hanshin Tigers—Hanshin’s treasured baseball team and one of the most emotionally important brands in Kansai. This wasn’t an argument about operating margins. It was a threat, at least in the public imagination, to break apart something communal and historic for the sake of financial engineering.

The backlash was immediate. To millions of Tigers fans, it felt like an outsider trying to monetize the soul of the region.

And that’s what made Hanshin such a unique target. Plenty of companies have undervalued assets. Not many have one that doubles as a cultural institution.

Hankyu's White Knight Response

With Murakami nearing control of half the company, Hanshin’s management faced a brutal choice: accept activist demands that could reshape—or even carve up—the group, or find a friendly acquirer.

Hankyu stepped in.

Under president Kazuo Sumi, Hankyu Holdings began buying Hanshin shares and moved toward a tender offer. It was not a cozy, pre-negotiated deal; Hankyu proceeded even without reaching an agreement on price with Hanshin’s largest shareholder—the Murakami Fund. Hankyu announced it would offer 930 yen per share.

At the press conference, Sumi was unusually direct about what was at stake.

“We strongly want Mr. Yoshiaki Murakami to apply for our tender offer, as it will lead to the first postwar reconfiguration of capital ties of private railway companies,” Sumi said.

Read between the lines, and it’s a remarkable admission: Murakami had forced a strategic consolidation that might otherwise have remained politically, culturally, and institutionally impossible for years. Whatever you thought of him, he had created a moment where a decades-old rivalry could suddenly be reframed as a merger.

The Resolution: Murakami's Downfall

The whole saga peaked in June 2006 with one of the strangest corporate press conferences Japan had seen.

Murakami called reporters to the Tokyo Stock Exchange on Monday, June 5, 2006, at 11:00 a.m. The expectation was straightforward: he would discuss Hankyu’s tender offer for Hanshin. And he did say he would go along with it.

Then he did something nobody expected. He acknowledged illegal insider trading—connected not to Hanshin, but to a separate deal: Livedoor’s 2005 acquisition of a large block of shares in Nippon Broadcasting.

What should have been a clean exit—tender your shares, book the profit, move on—turned into an on-the-record confession. The scandal that had been swirling around Japanese markets suddenly had a central character admitting his part in it.

Murakami was later convicted of insider trading, sentenced to two years in jail, and fined 1.2 billion yen. His fund, which was effectively dismantled, was also fined 300 million yen.

And while Murakami’s personal story collapsed, the corporate dominoes he set in motion kept falling.

On October 1, 2006, Hankyu Holdings changed its name to Hankyu Hanshin Holdings following the merger with Hanshin Electric Railway. The corporate group names were also reorganized accordingly, creating what was described as the first business integration between major private railway firms in Japan’s postwar era. Sumi became the first president of the new holding company and later served as chairman.

The legacy of the Murakami affair is messy, and that’s part of why it matters. In the years immediately after, activist investing in Japan largely went quiet. The reputational risk looked radioactive, and the broader shock of the 2008 global financial crisis only reinforced the retreat. Murakami himself left Japan for Singapore in 2009 to focus on real estate investments.

But the deeper lesson didn’t disappear: Japanese corporate structures could be vulnerable to determined shareholders, and the old web of relationships and cross-shareholdings couldn’t guarantee protection forever. That idea helped push corporate governance debates forward—even if the country wasn’t ready to say so at the time. By 2025, Japan saw a record 146 activist campaigns in a single year, a sign that Murakami wasn’t the end of the story. He was an early, volatile preview.

VII. The Merger Integration Era (2006-2015)

Creating a Unified Conglomerate

The 2006 merger between Hankyu Holdings and Hanshin Electric Railway created a group with its center of gravity in Kansai—and with a footprint that now spanned transportation, retail, real estate, entertainment, and media. The trains remained the core cash generator, anchored by the two operating railways: Hankyu Railway and the newly acquired Hanshin Electric Railway.

On paper, the logic was obvious. Both companies ran dense urban networks in the same region. Both had spent decades accumulating and developing real estate around their stations. Both operated department stores and entertainment assets designed to turn foot traffic into revenue. Put them together, and you could cut duplicated costs, coordinate development, and run the whole machine more efficiently.

But the merger also delivered something you can’t engineer with synergies: emotion.

By acquiring Hanshin, Hankyu Hanshin Holdings became the owner of the Hanshin Tigers. And that’s the perfect irony of the entire Murakami saga. Hankyu had sold its own team, the Braves, back in 1988. Now, through a merger triggered by an activist threat, it found itself owning the most culturally significant sports franchise in Kansai—by far.

Another Activist Challenge

The Murakami affair didn’t end activist interest. If anything, it confirmed that these old, asset-heavy conglomerates could be pressured.

In 2006, Fund Privee Zurich Turnaround Group—run by Kenzo Matsumara—took a major stake in Hankyu Holdings, aiming to push efficiency improvements across the sprawling Hankyu-Toho group. But the timing couldn’t have been more complicated. Hankyu was in the middle of absorbing Hanshin, management had put anti-takeover measures in place, and then the 2008 global financial crisis hit. By 2008, Privee had reduced its stake.

In practical terms, the crisis shut the window. Markets were collapsing, financing conditions tightened, and management suddenly had room to focus on integration without sustained outside pressure.

Real Estate Becomes the Growth Engine

With transportation throwing off steady cash, the next chapter was about turning that stability into growth—and the clearest lever was real estate.

The group’s priority became its most important base of operations: central Umeda. The Umeda Hankyu Building and the GRAND FRONT OSAKA development projects were completed in 2012 and 2013, aiming to make the district more compelling—and, in the process, lift value across the group’s railway lines. The early signal management pointed to was exactly what Kobayashi would’ve cared about: rising ridership.

The headline project was in Umekita, the north side of Umeda. Grand Front Osaka opened in April 2013, built on the former site of a Japan Railways freight yard, just north of JR Osaka Station. In one move, dead industrial land became a dense, modern mixed-use district—buildings, public space, and a commercial gravity that pulled people through the area.

And this wasn’t just a Hankyu-only bet. Grand Front Osaka was a consortium development, directly connected to JR Osaka Station, and designed to position Umeda as something bigger than a busy terminal: a world-class urban center.

VIII. INFLECTION POINT #2: The Umeda Transformation & Grand Front Osaka

The Umeda Vision: Reimagining Japan's Second-Largest Business District

By the 2010s, Hankyu Hanshin had already proven it could turn underused land into a new center of gravity. The question became: what do you do when your “center” is already one of Japan’s biggest?

In May 2022, the group put a name to the next chapter. It formulated the “Umeda Vision,” a plan to make the Osaka-Umeda area a hub of international exchange—a place where people from around the world would want to work, build, and visit.

That ambition isn’t marketing fluff. Osaka-Umeda is the largest transportation node in western Japan, and it’s uniquely positioned to function as a true multi-purpose urban core: offices, retail, hotels, culture, and the infrastructure that keeps it all moving.

In many ways, Umeda is Kobayashi’s original idea—scaled up by a century of compounding. What began as a single terminal and a department store has become a dense, connected ecosystem: towers stitched together by underground passages, retail that stretches like a second city beneath street level, hotels above, and public space designed to keep the whole district livable as it grows.

Osaka Umeda Twin Towers: Symbol of the Merger

If the merger between Hankyu and Hanshin needed a physical symbol, it got one in steel and glass.

Osaka Umeda Twin Towers South is a large-scale complex developed by Hanshin Electric Railway and Hankyu Corporation. Construction began in 2014, and the project was completed on February 25, 2022.

It’s a true “city-in-a-building” development: a department store, office space, and conference halls stacked into a single complex, with multiple basement levels and 38 floors above ground, spanning an integrated footprint across city blocks.

The key detail is how it was built. Two separate buildings, owned by the two companies and divided by a public road, were redeveloped as one integrated project after management integration. Around it, the sidewalks, pedestrian bridges, and underpasses were rebuilt too—because in Umeda, circulation is everything.

That integration also enabled a first for Japan: private-sector construction over a road under the law on special measures for urban revitalization. It’s a technical-sounding milestone, but the point is simple. The group wasn’t just rebuilding buildings; it was rewiring how the district connects and flows.

This was part of the broader Umeda 1-1 Project. The former Dai Hanshin Building (home of the Hanshin Department Store’s Umeda Main Store) and the Shin Hankyu Building were replaced by Osaka Umeda Twin Towers South, which opened in spring 2022. Nearby, the Umeda Hankyu Building—housing the Hankyu Department Store’s Umeda Main Store and offices—became known as Osaka Umeda Twin Towers North. Together, they form the Osaka Umeda Twin Towers.

Grand Green Osaka & Future Development

Then came the next leap: taking the old rail yard land north of Osaka Station—already transformed once by Grand Front Osaka—and pushing the concept further.

Grand Green Osaka is the second phase of the redevelopment of the former train yards in Umekita. At a ceremony on September 6, 2024, the project opened its initial area. From here, it rolls out in phases, with a full opening planned for spring 2027.

Grand Green Osaka and Umekita Park reached substantial completion on September 4, 2024, with the overall project aiming for completion in 2027. The development is enormous in scale—planned as a roughly ¥1 trillion project—and it’s designed to be a destination on its own, with expectations of drawing massive annual foot traffic.

At the center is Umekita Park: around 45,000 square meters of green space, directly connected to Osaka Station. It’s meant to do double duty—raising quality of life and strengthening disaster resilience by serving as a wide-area evacuation space. With Expo 2025 approaching, the early opening wasn’t just symbolic; it was strategic.

Grand Green Osaka also introduces a concept it calls “Osaka Midori Life”—midori meaning green—positioning the district as a place where quality of life, sustainability, and new industry formation are supposed to reinforce each other, drawing companies and research institutions into the orbit.

For Hankyu Hanshin, this isn’t only about one park or one project. The company has also initiated the Shibata 1 Development Project to increase the value of the area centered around Hankyu Osaka-umeda Station.

And the asset base underneath all of this is huge. The group owns a wide range of commercial facilities and office buildings across Osaka-Umeda and along the Hankyu and Hanshin lines, including Osaka Umeda Twin Towers, GRAND FRONT OSAKA, HERBIS OSAKA and HERBIS ENT, and Hankyu Nishinomiya Gardens. In total, its leasing property area is about 2.25 million square meters.

That’s the long arc of Kobayashi’s original invention. He started by betting on a train to a hot springs village. A century later, his successors were managing one of Japan’s premier urban real estate portfolios—and still using rail as the engine that keeps it all valuable.

IX. INFLECTION POINT #3: The Hanshin Tigers' 2023 Championship

38 Years of Waiting: The Curse of the Colonel

For nearly four decades, Tigers fans carried around an explanation for the pain—part superstition, part folklore, and completely Kansai.

During the celebrations in Dōtonbori after Hanshin won the Central League pennant in 1985, fans stole a statue of Colonel Sanders from outside a nearby KFC and threw it into the Dōtonbori River. From there came the Curse of the Colonel: the belief that until the Colonel came back, the Tigers would be blocked from winning the Japan Series.

And the drought was real. While Orix had won the previous year’s championship, the Tigers’ last Japan Series title was still that 1985 run—38 years earlier, and at the time the second-longest active championship drought in Nippon Professional Baseball.

The 2023 Championship Run

The 2023 Japan Series was the 74th edition of NPB’s championship: a best-of-seven showdown between the Central League and Pacific League champions. That year, the matchup was as local as it gets: the Hanshin Tigers versus the Orix Buffaloes—both based in Kansai.

It was only the second time two Kansai-based teams faced off in the Japan Series, the first being 1964. With the teams’ close proximity, the media dubbed it “The Great Kansai Derby,” and also the “Namba Line Series.”

The series ran from October 28 to November 5, 2023. Hanshin won in seven games, finally ending the 38-year drought—and, in the popular imagination, breaking the Curse of the Colonel.

Osaka celebrated the way Osaka always celebrates. Fans returned to Dōtonbori, and in a callback to 1985, someone dressed as the Colonel was thrown into the river.

Economic Impact: Entertainment as Economic Engine

The win didn’t just generate memories. It generated commerce.

Economists estimated the Tigers’ championship would produce an economic boost of about 130 billion yen across the Kansai region. The excitement even spilled into the market, with shares of companies tied to the moment—like Hankyu Hanshin Holdings and H2O Retailing—rising as investors anticipated a surge in spending.

Other forecasts went broader, predicting the Tigers’ Central League title—its first in 18 years—could spark economic activity of more than $650 million across Japan. Some economists suggested the impact of the Japan Series could even surpass the bump from Japan’s World Baseball Classic win earlier in 2023.

For Hankyu Hanshin, this is the business model showing its teeth. The Tigers aren’t just ticket sales and merchandise. They’re a demand engine that spills into the rest of the ecosystem: trains, department stores, restaurants, and hotels. Winning turns attention into foot traffic, and foot traffic into revenue.

In the wake of the title, the Hanshin Umeda department store in Osaka rolled out celebrations. Supermarkets under H2O Retailing, Joshin Denki, and even Hanshin Electric Railway joined in with commemorative merchandise and special deals designed to catch the wave.

Kobayashi’s original integration—transportation, retail, entertainment—creates a compounding effect. A standalone baseball team can win a championship. A baseball team inside a railway-and-retail empire can move an entire region’s spending.

Continued Success: 2025 Central League Championship

The Tigers’ momentum didn’t end with 2023.

In September 2025, the Hanshin Tigers won the 2025 JERA Central League championship, their first pennant in two years. They clinched on September 7—an especially early title win by Central League standards. The run came in Kyuji Fujikawa’s first year as manager, the former Tigers and Major League player returning to lead the club.

The Tigers reached the Japan Series again in 2025, this time facing the Fukuoka SoftBank Hawks. The Hawks won the series in five games.

Hanshin didn’t repeat as Japan Series champions. But the larger point held: sustained contention keeps the Tigers culturally dominant—and that dominance remains a marketing asset with real commercial spillover across the Hankyu Hanshin group.

X. Modern Era: COVID Recovery & World Expo 2025

COVID Impact and Recovery

The pandemic hit Hankyu Hanshin where it always hurts a rail-and-leisure empire most: movement.

Ridership fell. Hotels went quiet. And the Takarazuka Revue—built on the simple magic of a live audience—couldn’t perform in front of one.

But this is also where the century-old design of the group showed its value. When the transportation and hospitality businesses took the shock, real estate leasing kept producing steady cash flow. And with a strong balance sheet, Hankyu Hanshin didn’t face an existential fight. It faced a brutal downcycle—and had the staying power to wait it out.

World Expo 2025: Catalyst for Kansai Revival

Expo 2025 was a World Expo organized and sanctioned by the Bureau International des Expositions (BIE), held in Osaka for six months, from April 13 to October 13, 2025. It was the second time Osaka Prefecture hosted a World Expo, after Expo 1970 in Suita.

By the time the gates closed, the Expo recorded total attendance of 29,017,924 visitors, including 25,578,986 paid admissions.

Hankyu Hanshin was close to the action. Hankyu Hanshin Holdings was a Silver Partner of the Signature Pavilion “Future of Life.” And across Kansai, the event acted like a demand magnet for the group’s core ecosystem—moving people through stations, filling retail corridors, and supporting travel and hospitality.

Kazuo Sumi, the former president who had steered the group through the Hanshin merger, also left a mark here. He became vice chairman of the Kansai Economic Federation in 2011, and he played a major role in efforts to bring the 2025 World Exposition to Osaka.

Recent Financial Performance

In the nine months ending December 31, 2024, Hankyu Hanshin Holdings reported higher operating revenue and profit than the prior year.

Consolidated operating revenue was 598.8 billion yen, up 64.1 billion yen year over year. Profit rose to 84.7 billion yen, up 17.2 billion yen.

The biggest jump came from Real Estate. Operating profit increased to 37.4 billion yen, up from 29.1 billion yen the year before, helped by stronger condominium sales and steady leasing income.

Urban Transportation was next, generating 22.4 billion yen in profit, up from 19.7 billion yen.

Looking ahead, the company forecast operating profit of 127.4 billion yen for FY 2026, expecting improvement versus FY 2025, supported by the hotel business and lower expenses.

Challenges: The Takarazuka Controversy

Not every part of the ecosystem recovered cleanly.

In 2023, the Takarazuka Revue was shaken by a scandal that centered on the suicide of a 25-year-old actress, reportedly tied to overwork and power harassment. The result was intense scrutiny and damaging press—focused not just on the troupe, but on the management practices around one of the group’s most iconic institutions.

The Entertainment segment continued to feel the aftereffects. Revenue and profit fell as performances declined and merchandise sales weakened. The Hanshin Tigers helped offset some of the impact, but there are limits to how much a championship-level team can compensate for trouble elsewhere in the division.

The deeper damage was reputational. Kobayashi had built Takarazuka on a carefully crafted image—“purity, honesty, beauty.” The controversy didn’t just dent results for a year. It called the workplace culture behind the brand into question, and that kind of trust, once broken, is slow to rebuild.

XI. Investment Analysis: Myth vs. Reality

Bull Case: The Integrated Platform Story

The bull case for Hankyu Hanshin is basically the same idea Kobayashi pioneered—just scaled up to modern Kansai. The group has structural advantages that are hard to match, and even harder to copy.

Network Effects and Platform Lock-In: Hankyu Hanshin isn’t just running trains or collecting rent. It captures value across an entire routine. Live in a suburb the group helped develop, and the default options start stacking: commute on their lines, pass through their terminals, shop in their stores, stay in their hotels, attend their events. Each piece pushes traffic to the next.

Irreplaceable Infrastructure: The Osaka-Kobe-Kyoto corridor isn’t a product you can launch; it’s a century-long build. Once a private railway owns the rails, the stations, and the surrounding city fabric, the barriers to entry aren’t “high.” They’re effectively absolute.

Umeda Development Optionality: Umeda is still a compounding machine. Grand Green Osaka and the surrounding redevelopment aren’t one-time catalysts—they’re long-duration bets that can keep expanding the district’s pull for years. If Umeda keeps getting more valuable, the group’s surrounding asset base gets more valuable with it.

Entertainment Assets with Cultural Moats: The Hanshin Tigers and the Takarazuka Revue aren’t interchangeable entertainment properties. They’re institutions with generational loyalty and identity attached. You can spend unlimited money and still not manufacture that kind of cultural gravity from scratch.

Bear Case: Structural Headwinds

The bear case is also real—and it’s mostly about what happens when the ecosystem faces a shrinking pool of people, rising costs, and rising scrutiny.

Demographic Decline: Japan’s population is aging and shrinking. That tends to mean fewer commuters over time, and fewer commuters means lower ridership and less foot traffic through the station retail ecosystem. There’s no shortage of commentary on Japan’s birthrate collapse and labor shortages, and Hankyu Hanshin isn’t immune to those macro forces.

Capital Intensity: Railways and city-scale real estate don’t come with light maintenance mode. Tracks, rolling stock, stations, and safety systems require constant reinvestment. Major redevelopment projects add another layer: the Osaka Umeda Twin Towers required huge capital outlays, and Grand Green Osaka is a ¥1 trillion project. The point isn’t that these investments are irrational—it’s that payback horizons are long, and execution has to stay disciplined.

Post-Expo Uncertainty: Expo 2025 was a demand spike. After the crowds fade, the question is whether Kansai holds onto elevated visitor levels, or whether activity settles back closer to the baseline.

Corporate Governance Questions: The Takarazuka scandal didn’t just create a bad news cycle; it raised questions about oversight and workplace culture. For international investors, ESG isn’t abstract anymore. Reputational issues can translate into operational constraints, recruiting challenges, and long-term brand damage.

Porter's Five Forces Analysis

Threat of New Entrants: Very Low. Urban rail networks require approvals, capital, and time measured in decades. No realistic new entrant is going to build a parallel Kansai railway.

Bargaining Power of Suppliers: Moderate. Construction firms and rolling stock manufacturers have leverage, but Hankyu Hanshin’s scale helps it negotiate, standardize, and plan procurement over long cycles.

Bargaining Power of Customers: Low. For daily commuters, alternatives are limited. Where the rail network is the network, most riders take what’s there.

Threat of Substitutes: Moderate and Increasing. Remote work reduced commuting demand during and after COVID. Cars can substitute in some suburban contexts. The trend to watch is whether “less commuting” becomes permanently embedded in behavior.

Competitive Rivalry: Moderate. Transportation competition exists, particularly with JR West and other private railways, but it’s constrained by geography and network shape. In real estate, competition is more direct and more intense.

Hamilton Helmer's 7 Powers Analysis

Scale Economies: The railway business benefits from fixed costs spread across massive ridership, and the real estate side benefits from repeatable development capabilities and an established land footprint.

Network Effects: The loop is the whole thesis: development creates riders, riders justify better stations and retail, better stations and retail support more development. The ecosystem reinforces itself.

Counter-Positioning: Historically, Kobayashi’s integrated model forced a choice. A pure-play railway or a pure-play developer couldn’t easily copy the strategy without undermining its own model.

Switching Costs: High for residents who bought into Hankyu-developed communities and built their routines around the line. Lower for commuters in general, but still meaningful once you factor in convenience, time, and connectivity.

Branding: Strong, and unusually emotional. The Hankyu name, the Tigers, and Takarazuka create loyalty that isn’t purely price-driven.

Cornered Resource: The network itself—rails, stations, and prime terminal real estate—is a resource that can’t be recreated in any reasonable timeframe.

Process Power: This is what the group has been doing for more than a century: shaping cities around rail, then monetizing the entire flow. That institutional muscle memory—planning, development, operations, tenanting, integration—is real, and it compounds.

XII. Key Metrics and What to Watch

If you’re evaluating Hankyu Hanshin as an investment, the trick is to remember what it really is: a railway company that uses rail cash flows to power a much bigger, much stickier urban ecosystem. The metrics that matter are the ones that tell you whether that flywheel is still spinning.

Primary KPI: Rail Passenger Volume, Year-over-Year

This is still the foundational health check.

Rail transportation is the group’s most reliable source of steady cash, and it’s what underwrites everything else: station-area development, retail density, hotels, and the constant reinvestment that keeps the network attractive. If ridership slips for structural reasons, the impact doesn’t stay contained inside “Transportation.” It bleeds into foot traffic, tenant demand, and the overall gravity of the network.

The question to keep asking is simple: does passenger volume keep climbing back toward pre-pandemic norms, or did remote work reset the ceiling? The cleanest way to track it is in the company’s regular disclosures of passenger counts for both Hankyu Railway and Hanshin Electric Railway.

Secondary KPI: Real Estate Segment Operating Margin

If rail is the heartbeat, real estate is the growth engine.

With non-rail businesses now making up roughly 80% of total revenue, Real Estate has become the segment where execution shows up fastest. The operating margin here tells you whether management is converting Umeda-scale ambition into profitable reality—especially in condominium sales and in the durability of leasing income.

Recent performance has been strong. Operating profit rose to 37.4 billion yen in the first half of FY 2026, up from 29.1 billion yen a year earlier, helped by a jump in condominium sales and steady leasing revenue.

Tertiary KPI: Visitor Traffic to Entertainment Venues

This one is less about a single line item and more about the “culture layer” of the whole ecosystem.

Hanshin Tigers attendance, Takarazuka Revue ticket demand, and hotel occupancy rates are all early signals of consumer confidence in Kansai. They also matter for a uniquely Hankyu Hanshin reason: these venues don’t just earn money directly, they generate habits. They give people reasons to ride, to shop, to stay, and to choose the group’s properties and destinations over alternatives.

This is also where reputational risk becomes measurable. The Takarazuka controversy isn’t just a past headline; it’s an ongoing question. Does the audience come back as operations stabilize, or does brand damage linger longer than investors expect?

Shareholder Structure and Governance

Hankyu Hanshin’s shareholder base is broad: the general public, including retail investors, owns about 60% of the shares, while institutions hold around 37%. Insiders own less than 1%, based on available information. BlackRock, Inc. is the largest shareholder, with an 8.7% stake.

Low insider ownership isn’t unusual in Japan, especially for long-established conglomerates. But it does put more weight on governance and capital allocation discipline, because alignment can’t be assumed.

And it keeps one old lesson relevant. The Murakami episode proved that, under the right conditions, an asset-heavy structure with dispersed ownership can attract activist pressure. Hankyu Hanshin adopted defensive measures after that experience, but governance remains something to watch—not as a theoretical risk, but as a factor that can shape strategy when markets get stressed.

XIII. Conclusion: The Railroad Tycoon's Enduring Vision

In 1907, a former banker bet his career on an idea that looked almost backward: build a railroad to nowhere, and trust that the “somewhere” would come later. Over the next 118 years, that wager hardened into an urban machine spanning transportation, real estate, retail, and entertainment—an integrated system that shaped how millions of people live, work, and spend their weekends across Kansai.

Ichizō Kobayashi was practicing what we now call transit-oriented development decades before the phrase existed. His successors carried that blueprint through forced wartime mergers, postwar rebuilding, the boom-and-bust cycles of modern Japan, the Murakami-era shock that rewired corporate governance, and the demand collapse of COVID. What emerged on the other side wasn’t just a railway operator. It was a compounding platform—rails plus land plus destinations—built to generate its own demand.

The future isn’t frictionless. Demographic decline is a real headwind for ridership. The business remains capital-intensive by nature, with projects that take years and pay back over decades. And the Takarazuka scandal exposed governance and culture issues that can’t be waved away by history or brand equity.

But the strengths are just as concrete. The group controls railway infrastructure that simply can’t be replicated. It owns prime real estate in and around Umeda, one of Japan’s most important urban nodes. It has entertainment assets with generational loyalty—especially the Hanshin Tigers—that don’t just earn revenue, they pull people into the broader ecosystem. And it has something that’s harder to measure than tracks or towers: institutional muscle memory, built over a century, for turning stations into city centers.

For investors looking at Japan, Hankyu Hanshin is unusually scarce. It isn’t only exposure to “infrastructure,” and it isn’t only a property story. It’s a company that owns the platform, owns what happens on the platform, and has spent generations learning how to keep developing both. You can’t assemble that set of advantages from scratch today, no matter what you’re willing to pay. It had to be built—one line, one neighborhood, one destination at a time.

Kobayashi’s enduring insight was simple: the ticket is only the beginning. Transportation creates the conditions for modern urban life; the real value is in capturing the ecosystem that forms around the movement. Hankyu Hanshin Holdings is what that idea looks like after a century of compounding.

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music