JR West: Japan's Western Rail Giant and the Soul of an Obsession with Safety

I. Introduction & Episode Roadmap

Picture a Monday morning in late April 2005. It’s just after rush hour in Amagasaki, a commuter city west of Osaka. Kids have been dropped off. Offices are already humming. And at 9:19 a.m., the rhythm of an ordinary day snaps.

A seven-car commuter train on JR West’s Fukuchiyama Line hits a curve at 116 kilometers per hour—on a bend posted for 70. The train derails. The front cars slam into an apartment building. The first car slides into the building’s ground-floor parking area and takes days to remove. The second car crumples into an L-shape against the corner. Out of roughly 700 passengers, 106 people and the driver are killed. Hundreds more are injured.

That tragedy is the doorway into this story. Because JR West—West Japan Railway Company—isn’t just a train operator. It’s one of the core companies of the Japan Railways Group, serving western Honshu from its headquarters in Kita-ku, Osaka. It’s publicly listed on the Tokyo Stock Exchange, included in the TOPIX Large70, and one of only three JR companies in the Nikkei 225, alongside JR East and JR Central.

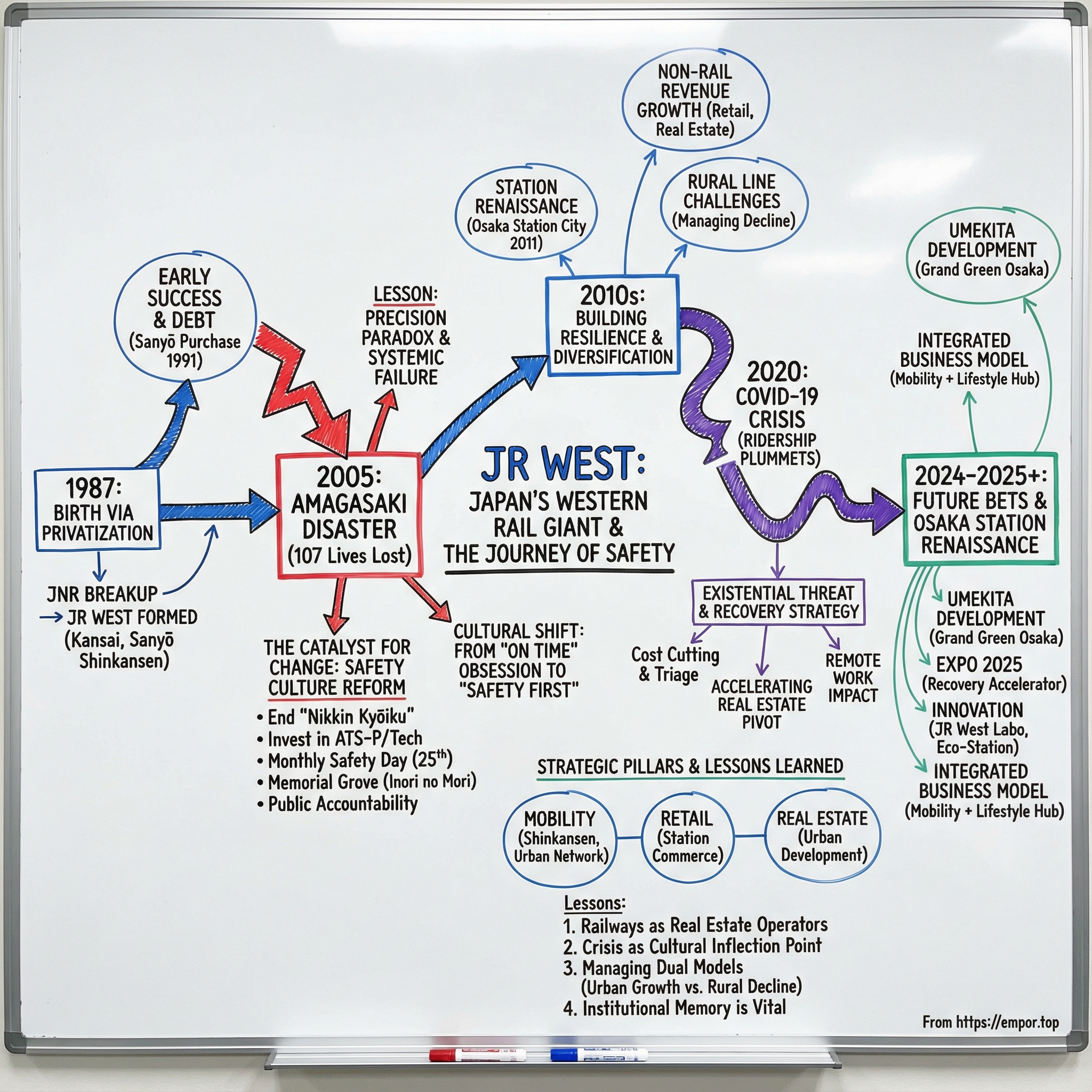

The question we’re answering is deceptively simple: how did a railway company born from the breakup of one of Japan’s most infamous public-sector failures go on to face a defining catastrophe, rebuild its identity around safety, survive a pandemic that emptied trains overnight, and then stake its future on what sits above and around the tracks—station real estate?

Along the way, a few themes keep resurfacing. Privatization as transformation: what happens when you turn a national bureaucracy into a business with real accountability. Safety culture as corporate identity: how an organization responds when human error becomes fatal on a massive scale. The paradox of punctuality: the thin line between precision as a competitive advantage and precision as a dangerous obsession. And the hidden engine of Japanese rail: the idea that the “railway company” is often, at heart, a real estate and retail ecosystem anchored by stations.

We’ll spend most of our time in the last two decades, where two shocks—Amagasaki in 2005 and COVID—reshaped what JR West is and what it’s trying to become. By fiscal year 2024, the company’s operating revenues had climbed to roughly 1.64 trillion yen. But that recovery wasn’t automatic. It came after the darkest chapter in its history, and a hard, ongoing redefinition of what a railway company owes the public.

II. The Birth of JR West: Japan's Railway Privatization Story

To understand JR West, you have to start with the spectacular failure that came before it.

By the mid-1980s, Japanese National Railways—JNR—wasn’t just struggling. It was structurally broken. By 1987, JNR’s debt had climbed past ¥27 trillion, and on a day-to-day basis the math didn’t work: the company was spending about ¥147 for every ¥100 it took in.

Sit with that for a second. Even if every train ran full, even if every employee worked flawlessly, it was still losing money by design. The only thing keeping it alive was the government’s willingness to keep writing checks.

And the debt only got worse. When privatization finally happened in 1987, JNR’s total debt sat at more than ¥37 trillion. Under the 1987 Railway Reform Law, that burden was split: 60% went to the newly created JNR Settlement Corporation, and the remaining 40% was assigned to three of the new passenger rail companies—JR East, JR Central, and JR West.

So how did a national railway in a rich, train-loving country end up here?

Part of it was competition. In the 1970s and onward, cars and highways pulled riders away, and airlines became a real alternative on big intercity routes. But the deeper damage came from governance. Politicians treated the railways like a tool of regional policy—pushing construction of money-losing lines into remote areas, often for the political payoff. Management got pulled in conflicting directions, while the debt kept snowballing.

Then there was labor. Unions held enormous power, and rigid work rules made it hard to change staffing or operations. JNR was trapped in a cost structure built for a different era, even as its customers and economics shifted beneath it.

The fix Japan chose was audacious. Instead of trying to “turn around” the monopoly, the government broke it apart.

In April 1987, JNR was privatized and reorganized into seven companies: six regional passenger railways and a nationwide freight operator. On Honshu, the main island, three new giants emerged: JR East around Tokyo and the northeast; JR Central along the Tokyo–Nagoya–Osaka corridor, including the original Shinkansen; and JR West, anchored in the Osaka–Kobe–Kyoto region and stretching west toward Fukuoka. The other three passenger companies—JR Hokkaido, JR Shikoku, and JR Kyushu—served Japan’s smaller islands. JR Freight handled cargo nationwide.

JR-West was incorporated as a business corporation (kabushiki kaisha) on April 1, 1987. From day one, it inherited a hugely valuable advantage: Kansai’s dense urban corridor, centered on Osaka, Kobe, and Kyoto. But it also inherited a complicated question that would define its early economics: the Sanyō Shinkansen, the high-speed spine from Osaka to Fukuoka.

Here’s the twist. JR West didn’t immediately own that crown jewel. For its first four years, the company leased the Sanyō Shinkansen from a separate entity, the Shinkansen Holding Corporation. Then, in October 1991, JR West bought the line—taking on 974.1 billion yen (about US$7.2 billion) in long-term debt to do it.

It was a massive, nerve-wracking bet, and it was existential. Without ownership, JR West would always be paying rent on its best asset. With ownership, it could run the high-speed network as a true core business—integrated with conventional lines, optimized for operations, and finally capturing the full upside. Over time, that decision proved foundational: the Sanyō Shinkansen would go on to generate roughly 40% of JR West’s passenger revenue.

But JR West wasn’t fully “private” overnight. The government’s exit took years. In October 1996, the JNR Settlement Corporation sold 68.3% of JR West in an IPO on the Tokyo Stock Exchange. When the settlement corporation was dissolved in 1998, the remaining shares moved through government hands until 2004, when JRTT offered all of its JR West shares to the public in an international IPO—closing the chapter on government ownership.

By then, JR West had already pulled off something few countries have managed: turning the wreckage of a state-run rail monopoly into a profitable, publicly traded company moving millions of people.

And yet, even as the ownership story finally settled in 2004, the company was heading toward the moment that would redefine it far more than any balance sheet ever could.

III. The Core Business: Understanding the Revenue Engine

Before we can understand what went wrong in 2005, we need to understand what JR West is, economically. Yes, it runs trains. But the company is really built on three pillars that reinforce each other: mobility, retail, and real estate.

Start with the crown jewel: the Sanyō Shinkansen, the high-speed line running between Osaka and Fukuoka. It generates about 40% of JR West’s passenger revenue all by itself. One corridor, one product, doing the kind of heavy lifting that most regional railways could only dream of.

And JR West doesn’t operate it in isolation. At Shin-Osaka, the Sanyō Shinkansen links seamlessly with JR Central’s Tokaidō Shinkansen, enabling through-service between Tokyo and western Japan. In practice, that means JR West gets to tap into demand that starts on JR Central’s turf, while JR Central benefits from passengers continuing beyond Osaka. The result is a single, continuous high-speed artery across the country—operated by two companies, but experienced by riders as one system.

That line also lives in a constant knife fight with domestic airlines, especially on popular city pairs like Osaka–Hiroshima and Osaka–Fukuoka. The Shinkansen wins on the things that matter most to humans: it departs from downtown, arrives downtown, and does it with near-absurd reliability—delays measured in seconds, not minutes. Airlines, meanwhile, fight back with pricing power for early bookings and the raw advantage of flight time on the longest routes, if you ignore the airports.

Then there’s the other engine: the Urban Network, JR West’s dense web of commuter lines threading the Osaka–Kobe–Kyoto metro area. It spans hundreds of kilometers of track, includes hundreds of stations, and brings in roughly the same share of passenger revenue as the Shinkansen—just over 40%. These are the lines where ICOCA cards tap in and out in a blur, where train control is heavily automated, and where peak-hour frequency gets almost hard to believe.

Because during rush hour, trains can arrive as often as every two minutes.

That sounds like a brag—and it is—but it also comes with a cost. A system that tight doesn’t leave much room for the real world. When you’re running trains like clockwork, a small delay doesn’t stay small for long. It cascades. It spills into other lines. It misses connections. And it hands your riders a reason to try the competitor tomorrow.

Which matters in Kansai, because JR West isn’t the only game in town. It competes head-to-head with Osaka’s major private railways—Hankyu and Hanshin, Keihan, Kintetsu, and Nankai. Collectively, those “Big 4” are formidable. And yet JR West’s market share is roughly equal to all of them combined, largely because it has two advantages that commuters feel in their bones: it goes more places, and it goes fast. Some of its Special Rapid Service trains reach about 130 km/h—quick enough that, on many commutes, JR West isn’t just convenient. It’s the fastest option.

Speed, frequency, punctuality. In a competitive commuter market, those are moats.

They’re also temptations.

And finally, there’s the part of the business that most outsiders miss: everything above and around the tracks. JR West has spent decades building stations into commercial ecosystems—retail, restaurants, department stores, hotels, office buildings—designed to capture value from the foot traffic its trains create. In Japan, the station isn’t merely infrastructure. It’s a marketplace. And that marketplace throws off rent and retail income in a way ticket sales alone often can’t, especially on less profitable rural lines.

This station-centered diversification would prove invaluable later, when COVID-19 emptied trains and the mobility business cratered while the rest of the ecosystem held up far better.

But long before the pandemic, long before JR West started openly talking about itself as more than transportation, this precision machine had a darker edge. Because when your brand promise is “on time,” and your competition is always one platform away, the pressure to keep the clock perfect can turn into something else entirely.

IV. The Amagasaki Disaster: A Defining Tragedy

April 25, 2005. The morning rush has just ended. Train number 5418M, a seven-car Rapid service running from Takarazuka toward Dōshisha-mae, is behind—about a minute and a half late. At the controls is 23-year-old Ryūjirō Takami. He has barely more than a year of experience. And this morning, he’s already made two mistakes.

Roughly 25 minutes earlier, Takami passed a red signal and triggered the automatic train stop system. He had to reverse the train back into position. Time lost.

Then, just four minutes before the derailment, he overshot Itami Station by more than three carriages and had to reverse again to align with the platform. More time lost.

Together, those errors put him about 90 seconds behind schedule. By the time he reached Tsukaguchi—the stop just before Amagasaki—he’d managed to claw that down to about 60 seconds.

That push to win back a single minute would end up costing 107 lives.

To understand why Takami drove the way he did, you have to understand the environment JR West had built around its drivers. In Kansai, punctuality isn’t a nice-to-have. It’s the product. Commuters time their lives to it, and the system is engineered to depend on it: at many stations, trains arrive on both sides of the same platform to enable fast transfers between rapid and local services on the same line. When one train slips, it doesn’t just inconvenience a few riders. It can knock the whole day’s timetable off balance.

So JR West kept tightening the screws. Over the three years leading up to the crash, the schedule margin on the fifteen-minute run between Takarazuka and Amagasaki was cut from 71 seconds to 28.

Less than half a minute of slack. On a real-world railway. With humans driving.

And if you fell behind, JR West didn’t just ask what happened. It punished you. Drivers faced financial penalties for lateness, and worse, they could be sent to a harsh, humiliating “retraining” program called nikkin kyōiku—“dayshift education.” It could include menial chores like weeding and grass-cutting, and it often involved being made to write lengthy reports of repentance under intense verbal reprimand. Many experts described it as punishment—psychological torture dressed up as training. The official report later concluded that this system was a probable cause of the crash.

Takami knew it firsthand. Ten months earlier, after overshooting a platform by around 100 meters, he’d been sent to nikkin kyōiku. It came with a loss of pay and tasks clearly designed to shame: cutting grass, cleaning toilets, sitting in a shared shift room copying the company rulebook by hand, or standing on a platform for days greeting other drivers.

Across his JR West career, he had already endured 13 days of it.

That context matters for what happened next. As he approached Amagasaki, Takami didn’t use the emergency brake. In the investigation, his fear was plain: emergency braking would be automatically recorded. A record meant scrutiny. And scrutiny could mean blame—and another round of “dayshift education.” His desire to avoid being punished again was identified as a major contributing factor.

Over time, in that kind of system, unsafe behavior stops feeling like a deviation and starts feeling like the job. Speeding to make up time—even when it increased risk—became normalized. In the months before the derailment, the same curve near Amagasaki had logged at least eleven “overspeed” incidents.

Eleven warnings. Same bend. Same story. No systemic change.

At 9:18 a.m., the rapid commuter train entered a 304-meter-radius curve near Amagasaki at 116 kilometers per hour, far above the 70 kilometer per hour limit. All seven cars derailed. The front cars slammed into an apartment building, collapsing part of its wall. 106 passengers and the driver were killed. Hundreds more were injured.

It was Japan’s worst rail disaster since the Tsurumi accident in 1963.

The backlash was immediate, and leadership accountability followed. Masataka Ide, a JR West adviser known for driving punctuality across the company, said he would resign in June 2005. JR West’s chairman and president resigned in August. And on December 26, 2005, President Takeshi Kakiuchi resigned to take responsibility. His successor, Masao Yamazaki, had previously served as vice president in Osaka.

But leadership changes couldn’t solve what the accident revealed. The real question for JR West was deeper and more painful: how do you rebuild an organization whose operating culture had optimized so relentlessly for “on time” that it had, in the most literal way, become unsafe?

V. The Safety Transformation: Rebuilding Corporate Culture

Amagasaki forced JR West to face an ugly reality: this wasn’t just one young driver making a catastrophic mistake. It was a system that had been built—intentionally or not—to push people toward dangerous behavior, and then punish them for leaving any evidence behind.

The first fixes were mechanical and immediate. Around the crash site, JR West lowered speed limits: from 120 to 95 km/h on the straight section, and from 70 to 60 km/h on the curve. Necessary, yes. But it was also obvious that new numbers on a sign wouldn’t heal what had broken inside the organization.

What had to change was the question the company asked itself. Not “Who do we blame?” but “Where did our processes, incentives, and training make this outcome more likely?” In that spirit, JR West moved quickly to expand ATS-P—an automatic train stop system—across the Fukuchiyama Line. And it overhauled nikkin kyōiku, stripping out the public-shaming rituals that had turned “retraining” into fear management.

Then came the long-term commitment: JR West allocated 610 billion yen for safety improvements through 2028. In a business where margins and timetables usually dominate the conversation, it was an unmistakable statement of priorities. Railways around the world drew lessons from Amagasaki, too—proof that a single disaster can reset what an industry believes is “affordable” when it comes to protecting passengers.

A major focus was building real safety nets against human error. JR West expanded automatic train protection systems that can intervene when a train exceeds limits—applying brakes automatically instead of relying on a driver to choose, in the heat of a mistake, between a “service” brake and an “emergency” brake that would be logged and scrutinized.

But technology, by itself, doesn’t rewrite a culture. JR West tried to solve that with something rarer in corporate life: memory, made deliberate.

We have designated the 25th day of every month "safety day." In addition to having study sessions and cross-departmental discussions on safety at each workplace, we hold "think-and-act" safety training at the Railway Safety Education Center and Memorial Grove (Inori no Mori) at the accident site for the purpose of acknowledging the lessons and points of reflection from the accident.

Every month, on the 25th—the date of the crash—employees return to the same point in time and ask what it demands of their work now. JR West even adapted that ritual during the coronavirus pandemic, connecting to the Memorial Grove remotely rather than letting the habit fade. The intent is explicit: don’t let distance, turnover, or time dull the seriousness of what happened.

And JR West didn’t stop at ritual. It built a place where the story can’t be abstracted away.

We incorporated input from victims and moved forward with a plan to construct a Memorial Grove (Inori no Mori) at the site of the Fukuchiyama Line accident in September 2018. The Memorial Grove includes a cenotaph, a Memorial Corner with letters to the deceased from their loved ones as well as various items donated in their memory, and an Accident Information Corner with panels giving details about the accident.

Alongside remembrance, there was care. In April 2009, JR West established the JR-West Relief Foundation (active as a public interest incorporated foundation since January 2010), which provides physical and mental support such as grief counseling for people affected by accidents and disasters, and also supports projects aimed at building safer local communities.

And then there’s the choice JR West keeps making, year after year, in public. As of 2025, the incident report still sits prominently on JR West’s Japanese homepage. The accompanying message is direct: “We will never forget the Fukuchiyama Line train accident that we caused on April 25, 2005. We will continue to put safety first and build a railway that is safe and reliable.”

Most companies, when they can, move past their disasters. JR West keeps its greatest failure near the front door. It’s not marketing. It’s a guardrail—an insistence that the organization never again gets to pretend this was someone else’s problem.

On April 25, 2025—twenty years to the day—about 340 people attended the anniversary ceremony, including JR West executives who renewed their pledge to prioritize safety and prevent a recurrence through continued cultural reform.

The impact didn’t stay in Japan. European and American railways adopted safety approaches inspired by lessons from Amagasaki—expanding automatic train protection, strengthening psychological support for drivers, and treating organizational culture as a safety system in its own right.

There’s a final challenge JR West has to manage: time. More than 70 percent of its current employees joined after the accident. They didn’t live through the old culture. They didn’t feel the incentives that warped behavior. So JR West is trying to transmit the lesson anyway—through mandatory training at the memorial site, through monthly safety day observances, through repeated exposure to the same hard truth.

For investors and operators, it raises an uncomfortable question: is institutionalized memory a competitive advantage, or an expensive form of corporate therapy? JR West is betting it’s an advantage. Since 2005, it hasn’t suffered a comparable accident. Trust, though badly damaged, has recovered. And many of the safety investments improved operations in ways that go beyond preventing a single worst day—by making the whole system less dependent on fear, and less vulnerable to one human mistake.

VI. The COVID-19 Crisis: Existential Threat & Recovery

If the Amagasaki disaster tested JR West’s soul, COVID-19 tested its balance sheet. For a company built to move people—millions of them, every day—a pandemic that made staying home a civic duty wasn’t a downturn. It was a threat to the whole machine.

The numbers tell the story in one gut punch. Revenue hit its low point in fiscal year 2020 at 1,849.4 billion yen—about a 40% drop from pre-pandemic levels. In other words: nearly four out of every ten yen disappeared. And unlike a software company that can shrink its cloud bill, a railway can’t mothball its core. Tracks still need maintenance. Stations still need staff. Trains still need to run, even if they’re carrying far more air than people.

What made it worse is that the shock wasn’t just temporary. Teleworking changed commuter patterns in a way that didn’t neatly snap back. Commuter pass revenue—those monthly and quarterly passes that form the bedrock of an urban rail business—recovered more slowly than other categories, reflecting a lasting shift toward hybrid work. And on the intercity side, the Shinkansen took a different kind of hit: business users discovered that a lot of “must be in person” meetings weren’t. Non-face-to-face meetings didn’t just dent demand; they rewired it.

JR West wasn’t alone. Across the big three on Honshu, the industry only clawed its way back to black operating income in fiscal year 2022, the first time since fiscal 2019. On an individual basis, JR East and JR West returned to positive operating income for the first time since fiscal 2019, while JR Central stayed in the black for a second consecutive year.

JR West’s response was a blend of triage and repositioning. It moved to reduce financial burden by curbing investment, advancing cost structure reforms, and even liquidating real estate it held. At the same time, it leaned into what Japanese railways have always quietly been: station-centered property and commerce businesses that can keep producing cash even when trains are emptier than planned. That showed up in how it talked about the future, too—accelerating its pivot toward non-railway businesses and doubling down on redevelopment around its most important hub: Osaka Station.

By fiscal year 2024, JR West’s operating revenues had climbed back to roughly 1.64 trillion yen, up from the year before. The company was growing again—but with a different center of gravity than the one it had relied on pre-COVID, with real estate and retail playing an even bigger role in stabilizing the enterprise.

And then came the next demand shock—this time, the kind JR West actually wanted: Expo 2025.

VII. The Osaka Station Renaissance & Future Bets

If you want to see JR West’s future in physical form, go to Osaka Station, walk to the concourse, and look north. What you’re watching rise there isn’t just another station upgrade. It’s one of Japan’s biggest urban redevelopment efforts—JR West’s wager that the next era of rail is built as much in offices, parks, hotels, and shopping streets as it is on steel rails.

The modern transformation started inside the station itself. In 2011, JR West added a massive roof and surrounding buildings that turned Osaka Station from a place people endured into a place people actually wanted to be. New open spaces made the flow of foot traffic feel less like a daily crush and more like a designed system. The station’s character changed.

Then the company pushed the center of gravity north. In 2013, the first phase of a huge redevelopment project opened on the former rail yard just beyond the tracks. The district is called Umekita—short for Umeda Kita, or “Umeda North”—and it’s being remade into a dense new neighborhood: residences, offices, shops, restaurants, and parks, stitched directly into the station.

The backstory goes all the way to privatization. The Umekita 2nd Project area used to be Umeda Freight Station, once the largest distribution base in Kansai. When JNR was broken up in 1987, the decision was made to relocate that freight operation. The land was held back, deliberately, for a future that didn’t yet have a blueprint.

That future took decades to arrive. In February 2023, JR completed the underground relocation of feeder lines for the Tokaido Line. The following month, it opened the new Osaka Station (Umekita Area). Around it, public and private partners also established a hub intended to link Kansai’s R&D facilities with industry—an explicit attempt to make the district not just a place people pass through, but a place where work gets done.

And there may be no better location in western Japan to attempt it. Osaka Station is the region’s busiest terminal, serving over 845,000 passengers and handling roughly 1,500 arriving and departing trains every day. That’s an enormous captive audience—one that turns a “transportation node” into prime commercial real estate.

JR West is treating the new underground station as more than a platform and a timetable. It’s positioned as a station of the future, designed to embody a technological vision the company drew up in 2018. One of the most visible expressions of that ambition is “JR West Labo,” an innovation experiment that uses digital technology to create interactive spaces inside the station itself.

Some of the tech is purely practical, and that’s the point. The Umekita Underground Station will trial full platform screen doors that adjust automatically—sliding to match different train door positions across multiple train types. Traditional platform doors are fixed, which essentially forces standardization. JR West’s approach is meant to solve the real operational problem: how to run varied rolling stock through the same platform while still getting the safety benefits of full-height barriers.

The station is also a testbed for sustainability. JR West’s goal is to make Osaka Station (Umekita Area) the first electricity-based “eco-station” with practically zero carbon dioxide emissions. As Mr. Kawabata explained, the plan includes adopting film-type perovskite solar cells—planned as the first use of this technology in public facilities worldwide. Because the film is lightweight and flexible, it can be installed across a wider range of surfaces, including curved areas, with the aboveground station plaza slated as an installation site.

All of this has been timed with a deadline JR West can’t miss: Expo 2025. The broader Umekita Phase 2 development is branded as Grand Green Osaka, and its opening sequence has been carefully staged. Private-sector work began in December 2020. Part of the area opened on September 6, 2024, including Umekita Park (South Park), directly connected to the station, along with commercial and business facilities. Next comes a major milestone: the Grand Green Osaka South Building opened on March 21, 2025. MICE facilities—an international conference center, hotels, offices, and the plaza in front of the station—are scheduled to come online just before the Osaka/Kansai Expo. The full buildout, including the remaining North Park and two condominium towers, is planned for FY2027.

And it isn’t only the north side. Major development has also advanced west of the station, anchored by two large projects that both opened on July 31, 2024—and both connect directly into Osaka Station. JP Tower Osaka rose on the site of the former Osaka Central Post Office and was jointly developed by Japan Post Group, JR West Group (Osaka Terminal Building Co., Ltd.), and JTB. Nearby, Innogate Osaka was constructed directly above JR Osaka Station as a new station building within Osaka Station City, built primarily by JR West.

Taken together, these projects show the Japanese railway playbook at its purest: the station as the city’s anchor point, and the rail operator as the developer that captures the value created by all the people the trains deliver. Fares matter—but the real long game is everything that happens once passengers step off the platform.

VIII. Expo 2025: The Recovery Accelerator

From JR West’s perspective, Expo 2025 arrived like a perfectly timed tailwind. Just as the company was finishing the biggest pieces of its Osaka Station-area buildout, the Kansai region hosted one of the world’s largest events—and the crowds followed. Roughly 29 million visitors came through.

The spillover showed up quickly across western Japan’s rail operators. Osaka Metro and JR West both moved to pay special bonuses to employees. And across the Kansai “major six” railroads, four raised their net profit forecasts for the fiscal year ending the following March.

JR West’s own results reflected that surge. Interim performance was strong enough that, in an earnings forecast announced on August 5, the company revised guidance upward. Management pointed to a clear mix of drivers: more riders thanks to the Osaka–Kansai Expo, and rising inbound tourism demand. The bump wasn’t limited to daily commuting, either. JR West said the Expo lifted revenue on its marquee long-distance services, including the Sanyō Shinkansen and the Hokuriku Shinkansen.

In retail, the Expo turned into its own kind of engine. Myaku-Myaku—the Expo’s red-and-blue mascot that looked odd on day one and somehow became beloved by day ten—sparked a merchandising wave that extended into JR West’s stores. The company explicitly tied robust sales of official Expo goods to the decision to pay bonuses of up to 120,000 yen.

Meanwhile, the bigger backdrop was that Expo 2025 wasn’t just a transit event. A private-sector survey estimated the Expo’s overall economic impact at about ¥3.05 trillion (around $19.6 billion). JR West didn’t capture that entire wave, of course—but it benefited from being the connective tissue of the region at the exact moment the world’s attention, and travel budgets, converged on Osaka.

There was a final, less obvious effect too: the Expo helped validate JR West’s long game. It put the Osaka Station redevelopment strategy under real-world load—millions of visitors, heavy foot traffic, packed trains, busy concourses, full hotels, and high retail demand—and proved that rail still matters in a digital-first era. More than a one-time boost, it was a showcase to international tourists whose spending, JR West hoped, would continue well after the gates closed.

IX. The Rural Line Challenge: Managing Decline

Not everything in JR West’s empire is a comeback story. Away from Osaka, Kobe, and Kyoto—away from the Shinkansen corridors—there’s a quieter, harder problem that hits railway operators around the world: what do you do with rural lines that lose money, but still function as essential lifelines?

These local routes were under pressure long before COVID-19. Depopulation has steadily thinned out the countryside. Car ownership rose. Roads improved. Ridership drifted away, year after year. Then the pandemic arrived and accelerated the decline, pushing many already-fragile lines into a new, harsher reality.

The Geibi Line, which JR West operates through the mountainous Chūgoku region, makes the challenge painfully concrete. Some segments are served by a single-car train running just three times a day, essentially to carry a small number of high-school students. On the busiest train, JR West says it sees 13 passengers. And on one section, the economics are almost surreal: the company estimates it spends about 27,000 yen in costs to earn 100 yen in fare revenue.

Read that again. This isn’t “low margin.” It’s a line where the costs and revenues aren’t even in the same universe.

Replacing trains with buses isn’t a clean fix, either. Japan faces driver and vehicle shortages, and bus substitution can mean less punctual service and more traffic congestion. Meanwhile, policymakers and the rail sector have increasingly acknowledged the obvious: the environment local railways operate in is nothing like it was at privatization in 1987. Rural depopulation and aging are real, and the private car has become the default outside the big cities.

And yet, there’s a countervailing principle that still holds moral and political weight:

JR Group companies should endeavour to maintain their existing networks of passenger services. There should be no decisions to close a railway simply because it is unprofitable, or because the average number of passengers per day is lower than any pre-determined figure.

That’s the contradiction JR West has to live inside. It can’t simply abandon communities that depend on rail. But it also can’t subsidize lines forever when costs exceed revenues by orders of magnitude.

This is where the JR model gets exposed. The whole system is built on cross-subsidization: profitable Shinkansen and urban networks quietly carry the weight of rural routes. It works—until it doesn’t. COVID-19 proved how fragile that bargain can be when the surplus from the cities suddenly evaporates.

For investors, the rural line question is both risk and, potentially, an opportunity. The risk is straightforward: as ridership continues to decline, rural losses can become a persistent drag on margins. The opportunity is more subtle: as rural populations shrink, they also consolidate. The people who remain increasingly cluster in towns and small cities—often the very places these local lines connect. In that world, the network might get smaller, but ridership on what remains could become denser.

X. Playbook: Business & Strategic Lessons

JR West’s story isn’t just about trains. It’s a case study in how a mature, capital-heavy business survives shocks, earns trust back, and finds new growth when its core market stops growing.

Lesson 1: Railways as Real Estate Companies That Operate Trains

The Japanese railway model flips the usual script. In many countries, real estate is something a transit operator happens to own. In Japan, stations are the platform for an entire commerce-and-property ecosystem. Privatization made that possible by letting the JR companies operate like full-spectrum businesses, not just utilities.

Across the JR Group, non-transportation revenue has become meaningfully large. JR East gets roughly a third of its revenue outside transport, and JR Kyushu is closer to 60%. JR West sits squarely in that same playbook, and its heavy investment around Osaka Station is the clearest expression of it.

The station isn’t simply where trains stop. It’s the demand generator that makes the surrounding land valuable in the first place. If you own the tracks but not the neighborhood above them, you’re leaving the upside to someone else. If you own and develop the neighborhood, your trains don’t just bring riders. They bring customers.

Lesson 2: Crisis as Cultural Inflection Point

Amagasaki forced a kind of change no incremental program could have delivered. JR West didn’t just add safety systems. It tried to rebuild its identity around safety, and then make that identity hard to dilute over time.

The institutional memory is the strategy: monthly safety days, a permanent memorial at the site, and a very public acknowledgement of responsibility that remains visible on its website. It’s the opposite of reputation management. It’s a choice to keep the failure in view.

That approach isn’t free. Memorial infrastructure, ongoing training, and time spent revisiting the same tragedy carry real cost. But the payback is also real, even if it’s hard to model cleanly: a workforce pushed to internalize safety as non-negotiable, a public that can see accountability rather than hear promises, and a defense against cultural drift—the slow slide back into bad incentives—that helped create the conditions for disaster in the first place.

Lesson 3: Managing Decline and Growth Simultaneously

JR West runs two different businesses at once. In Kansai, it operates dense, competitive urban lines that demand investment, service innovation, and operational sharpness. In rural western Japan, it operates lines facing long-term decline from depopulation and car dependence.

The challenge isn’t picking one. It’s managing both with different tools and different expectations.

Urban lines require offense: capacity, speed, convenience, and relentless execution against private-rail competitors. Rural lines require defense: honest economics, careful community engagement, and workable partnerships with local governments. Few management teams are asked to do both at the same time, and do them well.

Lesson 4: Competition Through Network Effects and Speed

JR West’s position in Kansai looks almost paradoxical: it competes with formidable private railways, yet its market share is roughly comparable to the Big 4 combined. That advantage rests on two things riders can immediately feel.

First, the network goes more places. Second, on many corridors, it gets there faster.

Both advantages are expensive. They require continual capital investment and high operational standards. And neither is easy for competitors to copy, because you can’t quickly replicate decades of rights-of-way, station footprints, and service patterns that have become embedded in how a region moves.

Strategic Framework Analysis

On paper, JR West looks like a company with unusually strong structural protection.

Threat of New Entrants: Extremely low. Building a competing railway network would take enormous capital, scarce urban land, and years of regulatory work. In practice, it’s not a realistic threat.

Bargaining Power of Suppliers: Moderate. JR West relies on specialized manufacturers and infrastructure vendors, but its scale makes it a crucial customer. Long-standing supplier relationships also help.

Bargaining Power of Buyers: Low to moderate. Individual riders have little leverage. Large corporate customers can negotiate at the margins, but their alternatives are constrained by time, convenience, and geography.

Threat of Substitutes: Moderate and rising. In cities, riders can choose private railways or subways. On longer routes, airlines compete on select corridors. But the most disruptive substitute is the one COVID accelerated: remote work, which doesn’t compete with rail on price or speed, but by eliminating the trip entirely.

Industry Rivalry: High in the Osaka–Kobe–Kyoto corridor, lower elsewhere. In the urban core, competition is intense. On many intercity and rural routes, JR West faces less direct rivalry.

Using Hamilton Helmer’s 7 Powers:

Scale Economies: Strong. Railways are dominated by fixed costs. Once the service is running, an extra passenger is close to pure contribution margin.

Network Economies: Strong. A broader, better-connected network increases the usefulness of the entire system, which attracts more riders, which justifies better service.

Counter-Positioning: Limited. The station-centered model is well understood in Japan and not a hidden trick competitors can’t see.

Switching Costs: Moderate for daily commuters who build routines around specific lines and stations; low for occasional travelers.

Branding: Meaningful. In Japan, trust matters in rail. JR West’s post-Amagasaki transformation—and its public accountability—adds weight to the brand.

Cornered Resource: Very strong. Track rights-of-way, station locations, and integrated hubs are assets that would be nearly impossible to reassemble from scratch today.

Process Power: Strong. The ability to run frequent, high-reliability service at scale—while embedding safety into operations—is a capability built over decades, and hard to replicate quickly.

XI. Key Metrics for Tracking JR West

If you’re tracking JR West as a business—not just as a railway—three metrics do an unusually good job of telling you whether the story is getting better, or quietly getting harder.

1. Shinkansen revenue as a percentage of total transportation revenue

The Sanyō Shinkansen contributes roughly 40% of JR West’s passenger revenue. That makes one line the clearest window into the health of the core mobility engine. Watch for how close it gets back to pre-pandemic demand, what happens in the constant tug-of-war with airlines, and how much inbound tourism lifts higher-value seats and long-distance trips.

2. Real estate operating income margin

JR West is increasingly leaning into the Japanese railway playbook: use stations as anchors, and make serious money from what you build on top of them. The real estate operating margin is the simplest way to see whether that bet is working—whether redevelopment projects are turning into durable earnings, and whether the company can keep occupancy and pricing power in its commercial buildings and hotels.

3. Urban Network ridership density (passengers per kilometer)

This is the “are we back to normal?” metric for Kansai commuting. If ridership density stabilizes, it suggests hybrid work has found its floor and the Urban Network can keep doing what it has always done: throw off steady cash and absorb shocks elsewhere. If it keeps sliding, the implications are bigger than the commuter lines themselves—because it threatens the cross-subsidy that helps keep unprofitable rural routes running.

XII. The Investment Case: Bull and Bear Perspectives

The Bull Case

JR West controls infrastructure you can’t realistically replicate in Japan’s second-largest metropolitan region. The Osaka–Kobe–Kyoto corridor remains an economic engine, and that density puts a natural floor under demand for frequent, high-capacity transportation—even in a country wrestling with demographics.

Its big bet on Osaka Station and the surrounding redevelopment is also hitting the market at a favorable moment. Inbound tourism surged in 2024 and 2025, and Osaka’s strength as a food-and-culture destination—alongside new resort development—creates a plausible path to sustained, tourism-driven ridership and station spending.

Amagasaki, as horrific as it was, forced a transformation that made the company tougher. JR West didn’t just add equipment; it built ritual and accountability into the organization. That visible commitment to safety and institutional memory is a form of trust that’s hard for competitors to copy quickly.

And then there’s the stabilizer: real estate. When train demand swings—whether from pandemics, work patterns, or business cycles—rent, retail, and hotels around major stations can cushion the blow. JR West’s station-centered model, refined over decades, lets it earn in ways a pure railway or a standalone developer can’t match.

Finally, the market’s skepticism often starts and ends with “Japan is shrinking.” But even in a slowly declining population, activity tends to concentrate in the biggest urban cores. That’s exactly where JR West’s most valuable lines, stations, and properties sit.

The Bear Case

The demographic math is still the demographic math. Japan is aging and shrinking, and the pain is most acute in rural areas—where JR West still runs a meaningful amount of network that loses money. The implicit bargain—urban and Shinkansen profits quietly covering rural losses—gets harder to sustain if the mix keeps shifting toward loss-making routes.

Work-from-home is the other structural risk. Even if leisure and tourism rebound, commuter passes were historically the bedrock of predictable rail demand. If hybrid work is permanent, pre-pandemic volumes may not come back, and the company has to adapt a cost structure built for a fuller daily peak.

In Kansai’s urban core, JR West also earns its position every day. The private railways are strong, and keeping a speed-and-network edge requires continual investment. If capital spending slips, the advantage can narrow—and market share can follow.

Real estate, meanwhile, cuts both ways. It diversifies earnings, but it also ties JR West more tightly to property cycles. A downturn—especially in offices and hotels—would land harder than it used to when the company was more purely a transportation story.

And there’s a final, uncomfortable tradeoff: making Amagasaki central to JR West’s identity is ethically powerful, but not free. Memorial upkeep, training, and observances are real ongoing costs that competitors don’t carry.

XIII. Conclusion: The Paradox of Precision

JR West’s story is, at its core, a story about precision—and what happens when precision stops being a craft and becomes an obsession.

The same seconds-level punctuality that made Japanese rail famous also helped create the conditions for catastrophe when it hardened into a culture of fear. The same privatization that freed JR West from political meddling also intensified commercial pressure to hit the timetable at all costs. The same operational discipline that made the network feel effortless to riders also made it easier for unsafe practices to become “normal,” until one ordinary Monday morning exposed what that normalization really meant.

What sets JR West apart isn’t that it failed. Many companies fail, sometimes spectacularly. It’s that JR West treated failure as something to be carried, not erased. Rather than burying the derailment, it built a memorial. Rather than reducing the story to one driver’s mistake, it interrogated incentives, training, and systems. Rather than “moving on,” it turned remembrance into routine.

Two decades after 107 people died on a curve outside Amagasaki, JR West still puts that tragedy where the public can see it—prominently, on its homepage. It’s a deliberate wager that accountability, made visible and permanent, is worth more than reputation management.

For investors, JR West is a bundle of hard-to-replicate assets: the Sanyō Shinkansen, a dominant urban network in Kansai, and a station-centered real estate engine that looks more valuable with every major redevelopment. The headwinds are real—Japan’s demographics, hybrid work, rural lines that don’t pay for themselves—but they’re also widely understood. The less obvious advantage is what the company learned the hard way: how to rebuild culture after a systemic failure, and how to keep that lesson from fading as new employees cycle in.

The trains still run on time. But now, when time pressure builds in the cab, JR West has tried to ensure it doesn’t end the way it did in 2005—through technology that intervenes, through training that supports rather than humiliates, and through an institutional memory designed to make safety the default, not the afterthought.

The Amagasaki memorial stands as proof that tragedy, when faced honestly and studied relentlessly, can prevent future tragedy. Those 107 victims didn’t die in vain. Their legacy protects millions of passengers—most of whom will never realize how close the system once came, and how much had to change to keep them safe.

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music