Japan Real Estate Investment Corporation: Tokyo's Premier Office REIT Pioneer

I. Introduction and Episode Roadmap

Picture the gleaming glass towers of Tokyo’s Marunouchi district in early September 2001. On September 10, two brand-new investment vehicles began trading on the Tokyo Stock Exchange, effectively kicking off Japan’s REIT market. They were backed by two of the country’s biggest real estate companies. One of them was Japan Real Estate Investment Corporation, ticker 8952.T—a name that would go on to matter a lot more than anyone could have known that morning.

The timing, on paper, looked almost absurd. Japan was deep in the “Lost Decades.” Property values had been falling for years. Confidence in real estate as a safe store of value had been badly shaken. And yet Japan’s policymakers and industry leaders were doing something bold: creating a liquid, publicly traded structure designed to pull capital back into a market that had gone cold.

What happened next is why this story is worth telling.

Since its IPO, the company’s assets (by total acquisition price) grew from 92.8 billion yen to 1,167.7 billion yen as of March 31, 2025—about twelvefold. Over that same stretch, the portfolio expanded from 20 properties to 77.

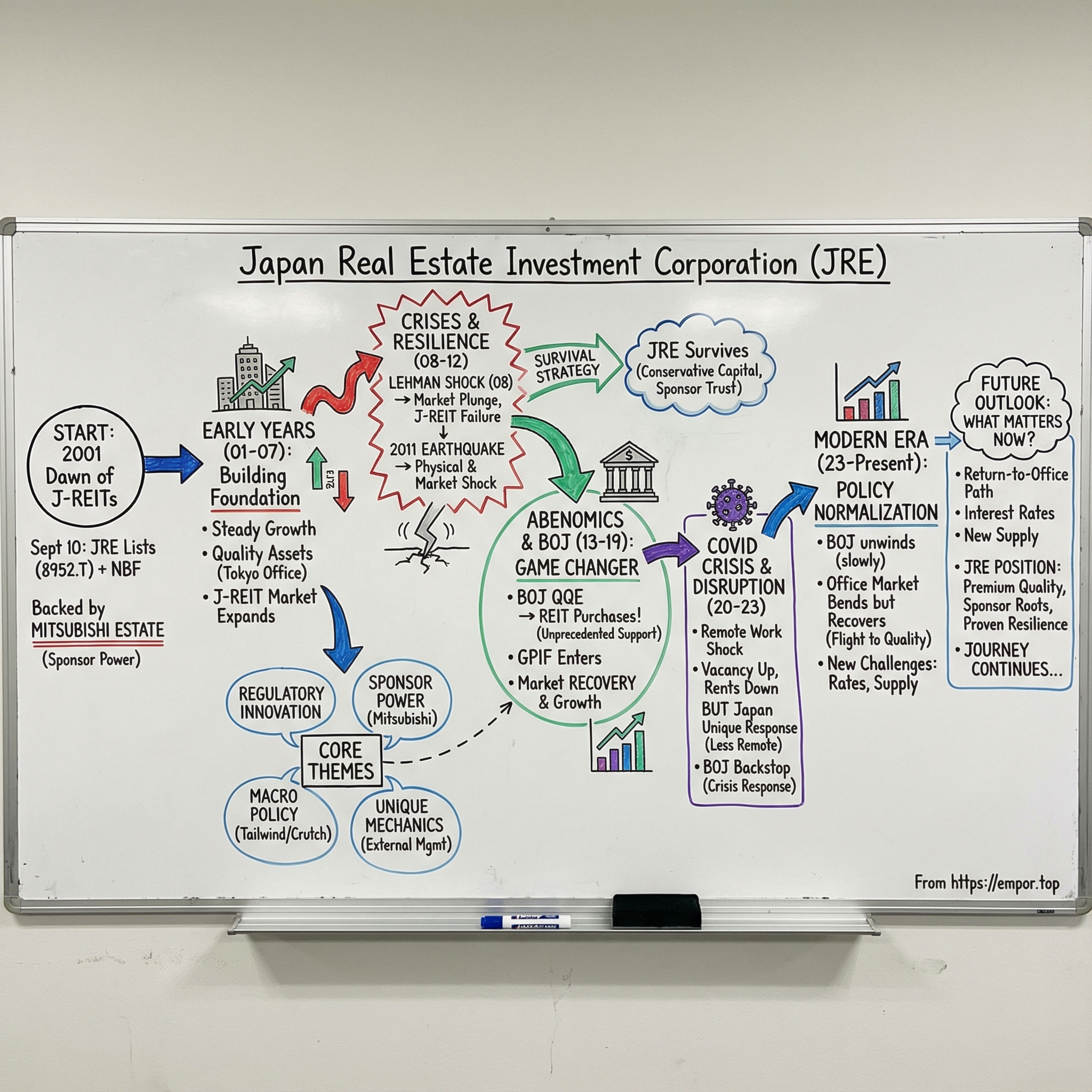

This episode is about how a vehicle created at the dawn of Japan’s REIT era became a defining owner of Tokyo office real estate—through the global financial crisis, the Great East Japan Earthquake, unprecedented Bank of Japan intervention, and then a pandemic that suddenly made the world question whether offices were necessary at all. Along the way, we’ll keep coming back to four themes: regulatory innovation, the power of the sponsor relationship, macro policy as a tailwind (and sometimes a crutch), and the unusually “Japanese” mechanics of how this market functions.

Japan Real Estate Investment Corporation is a J-REIT: a Japanese real estate investment trust that invests in, owns, and leases office properties. The vast majority of its portfolio sits in Tokyo’s 23 wards and the greater Tokyo metropolitan area by value, with a heavy concentration in the central business districts.

For investors, the big question is simple: can a premium Tokyo office REIT keep compounding in a world of remote work, rising rates, and central bank policy normalization? To answer it, we have to start where JRE started—inside the wreckage of Japan’s property bubble, and the policy response that tried to rebuild trust in real estate from the ground up.

II. Setting the Stage: Japan's Real Estate Context

The Bubble and the Lost Decades

To understand why Japan Real Estate Investment Corporation exists, you have to start with the shock that made it necessary.

Japan’s asset price bubble ran from the mid-1980s into the early 1990s, inflating both stocks and real estate into something that barely resembled reality. At the peak, central Tokyo valuations became legend: the Tokyo Imperial Palace grounds were famously said to be worth more than all the real estate in California. Whether or not the comparison was perfectly precise, it captured the mood. Japan wasn’t just booming. It looked unstoppable.

One key accelerant was the Plaza Accord in 1985—an agreement between Japan, the U.K., France, West Germany, and the U.S. to address global trade imbalances. In practice, it helped drive a sharp yen appreciation. The exchange rate moved dramatically, from 238 yen per dollar in 1985 to 165 in 1986. A stronger yen made overseas assets feel “cheap,” and Japanese companies went shopping—particularly for U.S. real estate. Money flowed out, speculation flowed in, and domestic property prices surged right along with it.

The era had its symbols. In 1989, Mitsubishi Estate bought Rockefeller Center in New York. In the West, it was portrayed as proof of the looming “Japan Threat.” Back home, it played as national triumph—another data point in the story that Japan was winning.

Then the story flipped.

The Nikkei hit 38,916 on December 29, 1989. Soon after, the Bank of Japan began raising lending rates to cool speculation and inflation. The air came out fast. In the early 1990s the bubble burst, and by early 1992 the economic damage was unmistakable. Over-confidence, easy credit, and a swelling money supply had fed the boom; tightening and reversal exposed how fragile it really was.

From 1991 onward, interest rate increases helped trigger a broader real estate collapse. Government countermeasures followed—raising tax burdens and accelerating foreclosures—which only worsened sentiment and reinforced the downward spiral. Tokyo housing prices at one point fell to less than half their peak, and the market stayed sluggish for roughly 22 years.

This is the backdrop for the “Lost Decade,” often dated from 1991 to 2001. GDP growth averaged just 1.14% a year. Real estate prices fell by roughly 70% over a similar period. By the mid-2000s, the hangover still felt extreme: prime “A” properties in Tokyo’s financial districts were described as having slumped to less than 1% of their peak, and Tokyo homes to less than a tenth.

However you slice the statistics, the takeaway is the same. Real estate in Japan didn’t just fall out of favor—it became something investors wanted to forget. And that’s the world J-REITs were born into.

The Birth of J-REITs as a Policy Solution

Into that wasteland came a policy idea imported from the U.S.: the real estate investment trust.

REITs started in America in 1960 as a way for everyday investors to access large-scale, income-producing real estate. Japan adapted that framework as part of broader reforms aimed at internationalizing its financial markets. In November 2000, Japan amended the Act on Investment Trusts and Investment Corporations, clearing the legal path for investment vehicles that could hold real estate.

The government’s hope was that J-REITs could do several things at once. They could bring liquidity back to a market that had seized up. They could open a new asset class to investors. And they could help address the overhang of troubled real estate holdings that had been weighing on banks since the crash.

With the legal foundation in place, the Tokyo Stock Exchange developed the rules for a dedicated J-REIT market. On paper, the model looked familiar: conduit tax treatment, rental income as the core engine, and a structure designed to distribute most earnings to investors.

But Japan made one major structural choice: unlike U.S. REITs, which can be internally or externally managed, J-REITs could only be externally managed. The REIT itself wouldn’t run the day-to-day business; it would outsource investment and management to an asset management company.

That external management model would become one of the most defining—and debated—features of J-REITs. But in 2001, the immediate question was more basic: after a decade of collapse and disillusionment, would anyone invest in Japanese real estate again?

The answer would arrive on September 10, 2001.

III. The Founding: Day One of Japanese REITs

May-September 2001: Creating History

Japan Real Estate Investment Corporation was established on May 11, 2001 under Japan’s Act on Investment Trusts and Investment Corporations. And then it moved fast. In a market still scarred by the burst bubble, it went from incorporation to listing in roughly four months—less a leisurely rollout than a deliberate sprint to prove that this new structure could work.

On September 10, 2001, JRE listed on the Tokyo Stock Exchange’s brand-new REIT market alongside its fellow pioneer, Nippon Building Fund. The symbolism was huge: this wasn’t just another IPO. It was Japan attempting to reboot institutional trust in real estate through a transparent, liquid public vehicle.

And then, the world changed overnight. The September 11 terrorist attacks occurred the day after the first two J-REITs began trading, injecting global fear and uncertainty into what was already a fragile experiment.

That JRE didn’t just survive that start, but went on to become a flagship, had a lot to do with what it brought to market on day one. The initial portfolio was 20 properties with total assets of 92.8 billion yen—positioned as premium Tokyo office buildings. The message was clear: if you were going to ask investors to believe in Japanese real estate again, you started with the best, in the best locations, run by the most credible operator you could put behind it.

Being first also meant carrying the weight of the category. JRE and Nippon Building Fund weren’t only selling units; they were establishing norms. Disclosure expectations, governance practices, and relationships with regulators and lenders were all being set in real time. If these first vehicles failed, it wouldn’t just be their investors who got burned—it would have threatened the legitimacy of the entire J-REIT idea.

The Mitsubishi Estate Pedigree

Behind JRE stood Mitsubishi Estate—one of the most influential names in Japanese real estate, and one with a very literal connection to the geography JRE would come to represent.

Mitsubishi Estate traces its origins back to 1890, when the Mitsubishi group acquired roughly 353,000 square meters of land in Marunouchi, near Tokyo Station. The Meiji government wanted the site sold to a single buyer, which made the price prohibitive for most. Mitsubishi could do it. The purchase price was ¥1.28 million, and the ambition was even bigger: to create a modern business center in Tokyo that could stand alongside London and New York.

The buildout followed. In 1892, Mitsubishi began constructing Western-style red-brick offices—an early signal of what Marunouchi was meant to become. When the government later agreed to locate Tokyo’s central railroad there, the district’s future snapped into focus. Mitsubishi wasn’t simply participating in the growth of Tokyo’s commercial core; it was helping define it.

Mitsubishi Estate was formally incorporated in 1937, but by then the engine was already running. By the mid-1970s, Marunouchi had grown into one of the world’s largest business centers. And the redevelopment never really stopped. Since 1998, Mitsubishi Estate has driven the “Reconstruction of Marunouchi,” an initiative aimed at creating new urban functions under the concept of “the city with the most active interaction in the world.” Beginning with the completion of the Marunouchi Building in 2002, building after building was rebuilt and modernized.

This is the sponsor DNA JRE inherited. Mitsubishi Estate wasn’t just lending a logo. It brought three practical advantages. First, pipeline access: when Mitsubishi developed or acquired prime assets, JRE could be a natural buyer. Second, operating expertise: leasing, asset management, and long-cycle redevelopment were what Mitsubishi had been doing for more than a century. Third, brand trust: in a country where real estate had become synonymous with painful losses, Mitsubishi signaled stability.

The Unique J-REIT Structure

JRE also launched into a structure that was distinctly Japanese. In the U.S., REITs can be internally managed or externally managed. In Japan, the Investment Trust Act effectively made the choice for everyone: J-REITs must be externally managed.

That means the REIT itself can’t hire employees or conduct substantive business activities. It has to outsource asset management to a separate company. For JRE, that manager is Japan Real Estate Asset Management (JRE-AM), which is wholly owned by Mitsubishi Estate.

This setup has always come with a debate attached. Critics point to potential conflicts: if the manager’s compensation is fee-driven, incentives may not perfectly align with unitholders. Supporters argue the trade is worth it because the model plugs the REIT directly into sponsor capabilities and deal flow that would be hard to replicate in-house—so long as governance and oversight are strong.

The economic heart of the REIT model, though, is tax. In Japan, as in other REIT regimes, distributions can be deductible from taxable income at the REIT level—often described as “tax conduit treatment”—as long as the vehicle meets certain requirements for the relevant fiscal period.

Two of those requirements are especially central. J-REITs must distribute at least 90% of taxable income to unitholders. And they must avoid becoming a captive vehicle: no single unitholder can own 50% or more of the units. The result is a structure designed to behave like an income-distributing investment product, not an operating company hoarding cash or a tax shelter controlled by one dominant owner.

Sponsor backing, tax efficiency, and forced high payout ratios became the template for the entire J-REIT market. JRE’s edge was that it helped establish that template—then got to operate with first-mover credibility inside it.

IV. The Early Years: Building the Foundation (2001-2007)

Steady Growth in a Skeptical Market

In the years after the September 2001 listing, JRE did the unglamorous work that makes a REIT last: it bought buildings, leased them well, and didn’t get cute.

It started with 20 properties and expanded methodically, sticking to premium, Grade A office assets in Tokyo’s central business districts. The bet was simple and stubborn: in a market still haunted by the bubble, the safest way to earn back investor trust was to own the kind of buildings tenants fight to be in, even when the economy gets weird.

That “quality over quantity” mindset became the brand. Each acquisition was framed as an upgrade to the portfolio, not just more square meters. Over time, it positioned JRE as a reference point for what “top-tier” meant in Tokyo offices.

The business model was equally straightforward. Nearly all income came from rental revenue. And while the tenant roster spanned a wide mix of industries, the largest chunks of leased space came from service companies, information services, electric device firms, and financial services.

That mix wasn’t accidental. Diversification was part of the risk strategy: if one sector pulled back, the idea was that another could keep the rent roll steady. It was a portfolio designed to survive cycles—not one built to chase the hottest theme of the moment.

The J-REIT Market Comes of Age

As JRE was building its portfolio, the whole J-REIT category was quietly turning into a real market.

In February 2005, total J-REIT market capitalization reached 1 trillion yen. Just two years later, in January 2007, it hit 5 trillion yen, and by May 2007 the market peaked around 6.7 trillion yen, with 41 listed J-REITs. The Tokyo Stock Exchange REIT Index rode the wave too, reaching a record high of 2612.98 on May 31.

The expansion had a familiar pre-crisis feel. Japan was finally showing signs of recovery. Global money was abundant. And the J-REIT format had passed its early test: transparent vehicles, steady distributions, and liquid exposure to an asset class that had historically been anything but liquid.

Prices rose, and yields fell. When the market launched, annual distribution yields were relatively high. By mid-2007, they had compressed to below 3% as unit prices climbed. Even then, J-REIT yields still sat about a point above 10-year Japanese government bonds, which were just under 2%—a spread that helped make the asset class feel like a rare combination of income and safety.

But yield compression is a double-edged signal. It tells you investors have embraced the story. It also tells you optimism is being priced in.

And by 2007, optimism was everywhere.

V. Crisis and Resilience: The Global Financial Crisis (2008-2012)

INFLECTION POINT #1: The Lehman Shock

September 2008 brought devastation to global financial markets—and the J-REIT sector was no exception.

Lehman Brothers collapsed, the global financial crisis spread, and suddenly the story around listed real estate flipped from “steady income” to “who can refinance next month?” The Tokyo Stock Exchange REIT Index plunged, eventually hitting 704.46—its lowest level since the index began.

The fall wasn’t just brutal. It was fast. By February 2009, the J-REIT market’s total value had shrunk to around 2.1 trillion yen. Just eighteen months earlier, it had been roughly 6.7 trillion. In other words: about two-thirds of the market evaporated in a blink.

And then came the moment that shattered the comforting idea that “REITs don’t go bankrupt.”

In October 2008, the first J-REIT failure hit: New City Residence Investment Corporation. On October 9, it filed for civil rehabilitation proceedings and was delisted. Importantly, the trigger wasn’t a collapse in its underlying leasing business. It was cash management—specifically, the inability to line up money for property purchase settlements and to repay loans in a market where financing had suddenly stopped existing.

New City Residence taught the market an uncomfortable lesson: a REIT could die even if its buildings were fine, simply by mismatching commitments and capital. The company had entered into “forward commitments,” agreeing to acquire properties before securing the funding. When credit froze, it couldn’t close those purchases and couldn’t refinance debt at the same time. In the aftermath, the industry responded by tightening practices and establishing guidelines that called for much more careful handling of these forward purchase agreements.

JRE's Survival Strategy

This is where JRE’s personality mattered.

JRE’s conservative capital structure—less exciting in the boom—became a life jacket in the bust. Compared with more aggressive peers, it had more breathing room in its debt terms and more diversified funding sources. When lenders pulled back and markets locked up, JRE had runway. It could focus on staying liquid and staying calm.

That approach was consistent with how the company positioned itself: long-term growth and stability through strategic real estate investment, guided by a conservative management philosophy and a deliberate approach to risk.

And then there was the sponsor effect. Mitsubishi Estate’s backing didn’t mean JRE was automatically “rescued,” but it mattered in a crisis defined by confidence. Lenders and investors could look at JRE and see a vehicle managed by an asset manager wholly owned by one of Japan’s strongest real estate developers. In a panic, that kind of credibility can be the difference between access and no access.

For investors, the dislocation showed up in the simplest possible way: yields. As unit prices collapsed across the sector, J-REIT distribution yields briefly spiked above 8%. For anyone able to hold through the chaos—or brave enough to buy into it—that was a rare, cycle-defining entry point.

The Great East Japan Earthquake (2011)

Just as the market began to find its footing, Japan was hit by another shock—this time, not financial.

On March 11, 2011, the Great East Japan Earthquake struck with a magnitude of 9.0, triggering a tsunami that devastated coastal areas along the eastern oceanfront, particularly in the Tohoku region. The human tragedy was immense, and the economic impact rippled through the country—including real estate.

For the J-REIT market, it meant that the recovery from 2008 didn’t get to be a clean, upward line. The sector’s initial growth phase through 2007 gave way to a long, uneven contraction through the 2010–2012 period, battered by both the global financial crisis and the earthquake.

JRE’s concentration in Tokyo mattered here. While the tsunami caused catastrophic destruction elsewhere, Tokyo’s infrastructure remained largely intact. And premium office buildings in the capital, built to strict seismic standards, generally avoided significant physical damage.

Even so, the market’s confidence took another hit. The J-REIT sector, having absorbed shocks in both 2008 and 2011, lagged other major REIT markets like the U.S., Singapore, and Hong Kong over the period. It was the only one that had to fight through two major crises so close together.

By the end of 2011, the J-REIT universe had shrunk to 34 listed vehicles, down from 41 at the 2007 peak. Survival increasingly meant scale, and the system began to adapt. A framework to enable mergers among J-REITs was put in place in January 2009, the first merger closed in February 2010, and seven mergers were completed in 2010 alone—an early wave of consolidation that helped reorganize the market around stronger hands.

JRE came through this stretch as one of those stronger hands. But the next phase wouldn’t just be about surviving. It would be about an entirely new kind of support—one that would change the J-REIT market’s relationship with capital itself.

VI. Abenomics and the Bank of Japan Revolution (2013-2019)

INFLECTION POINT #2: A Central Bank Becomes Your Investor

Nothing in modern central banking really prepared anyone for what Japan was about to try.

In late 2012, markets began to move on anticipation alone. The yen weakened. Stock prices jumped. Investors weren’t reacting to earnings or demographics; they were pricing in a regime change. Shinzo Abe, then the opposition leader, had been openly pressuring the Bank of Japan to do more to break deflation. When he won a landslide and returned as Prime Minister in December 2012, that pressure became policy.

What followed became known as Abenomics—three “arrows” aimed at restarting growth: unconventional monetary easing built around a 2% price stability target, fiscal stimulus, and structural reforms.

In April 2013, Abe installed Haruhiko Kuroda as BOJ governor with a clear mandate: make the monetary arrow real. Kuroda rolled out Quantitative and Qualitative Monetary Easing, or QQE, replacing the prior framework and pushing the BOJ into territory that would have sounded impossible a few years earlier.

On April 4, 2013, Kuroda laid out the plan: reach 2% inflation in roughly two years by dramatically expanding the monetary base, ramping up Japanese government bond purchases, extending the maturity profile of the BOJ’s JGB holdings, and—most notably—buying risk assets. Not just ETFs, but J-REITs too.

That last piece is the inflection point. The Bank of Japan wasn’t just influencing real estate through interest rates anymore. It was stepping into the market as a direct buyer of REIT units.

The Unprecedented REIT Purchase Program

Technically, the BOJ’s move into these assets had started earlier. In October 2010, it began purchasing equity ETFs and J-REITs as part of a large-scale asset purchase program meant to reinforce its zero-interest-rate policy. But QQE put that activity on a much bigger—and more explicit—track.

Under QQE from 2013, the BOJ set an annual J-REIT purchase amount of 30 billion yen. In October 2014, under what’s often referred to as QQE2, it tripled that pace to 90 billion yen a year.

Over time, the BOJ became a meaningful owner of the category. After about a decade of buying, by 2019 its J-REIT holdings amounted to roughly 3.5% of a REIT market with about 16 trillion yen of market capitalization. In parallel, it accumulated equity ETFs equivalent to about 5% of the total market cap of the Tokyo Stock Exchange. In other words, Japan’s central bank wasn’t just the marginal buyer of bonds—it had become a structural holder of public risk assets.

The design was intentionally countercyclical. When the BOJ is in the market as a buyer, it supports prices and compresses risk premiums, especially during periods of stress. And when a REIT sees more consistent demand for its units, it’s more likely to raise equity and recycle that capital into real assets—purchases, development, and broader investment activity that can spill into the real economy.

The BOJ’s purchases were also selective. It bought J-REITs with AA or higher credit ratings. That mattered. It effectively tilted the support toward the highest-quality vehicles, and it made premium names—JRE included—natural beneficiaries of the program.

Impact on JRE and the Real Estate Market

The effects spread quickly through the system, and the sector entered another long upswing. From 2012 through 2018, the J-REIT market experienced a sustained recovery—this time with two enormous institutions as visible backstops.

Abenomics and QQE helped turn loan growth positive again, with year-on-year loan growth hovering around the low single digits. Corporate lending expanded too, and a significant portion of that growth flowed into real estate. In tandem, land and property prices began to rise moderately.

Then came another symbolic signal. In April 2014, the Government Pension Investment Fund—GPIF—began investing in J-REITs. With the central bank and the world’s largest pension fund both participating, the J-REIT market had something it never had before: explicit, durable institutional sponsorship.

By July 2019, the TSE REIT Index climbed back above the 2,000 level—its first close there in more than a decade, since late 2007. The market had finally clawed its way back to its pre-crisis neighborhood.

For JRE, the environment was about as favorable as it gets. It was office-focused, concentrated in prime Tokyo, and carried the kind of AA-level credit profile the BOJ targeted. That translated into steady liquidity support during weak periods, lower financing costs, and a persistent signal that policymakers were willing to stand behind the asset class.

But even a central bank can’t buy its way around the next shock.

VII. The COVID Crisis and Office Market Disruption (2020-2023)

INFLECTION POINT #3: Remote Work Comes to Japan

The COVID-19 pandemic hit Japan in early 2020 and posed the scariest possible question for an office-focused REIT: if people stopped commuting, what happens to the value of office space?

What made the shock so disorienting is that Tokyo’s office market went into the pandemic in near-perfect shape. In the first quarter of 2020, the average vacancy rate had fallen to a record low of 0.6%. Premium buildings in the central wards were, for all practical purposes, full.

Then the World Health Organization declared COVID-19 a pandemic in March 2020. Japan declared a state of emergency in April. And suddenly, the biggest variable wasn’t interest rates or new supply. It was whether “the office” was still going to be a daily habit.

Telework spread quickly, even in a country known for slow adoption of new work styles. One measure of telework participation jumped from 6% in January 2020 to 17% by June. Over the longer arc of the pandemic era, broader surveys showed the same direction: the share of employees using telework rose from 13.3% in 2016 to 27.3% in 2021. Tokyo moved even faster—from 16.9% in 2016 to 42.1% by 2021. Among large firms with more than 1,000 employees, telework participation rose to 40.1% in 2021, up from 19.2% in 2016.

The office market responded the way you’d expect. Vacancy rose as companies reassessed space needs. Rents, which had been climbing for years, peaked and began to fall. By October 2023, vacancy in Tokyo’s five central business districts reached 6.1%, up from the very tight levels of early 2020. And rents told the same story: after peaking around July 2020, the average monthly rent per tsubo in Tokyo’s central business districts was lower by September 2024.

Japan's Unique Response to Remote Work

But Japan didn’t follow the exact path of the U.S. or Europe—and that matters for understanding why Tokyo offices didn’t unravel the way many feared.

Even during the pandemic, Japan stood out among developed countries for relatively low telework adoption. Cultural norms played a role, but so did practicality: research highlighted that working from home often came with a real productivity penalty. One study found average work-from-home productivity was about 30% lower than working from the office.

That gap shaped corporate behavior. Work-from-home surged as an emergency response—peaking in early May, right in the middle of the state of emergency—but began to fall once restrictions eased at the end of May. Many companies had shifted employees home because they felt they had to, then pulled them back once concerns about productivity and coordination outweighed the health emergency.

The pandemic even produced a new term—“workation,” working remotely from tourist destinations. But as the acute phase passed, the direction became clearer: telework was no longer simply “the future arriving early.” It was becoming a negotiated compromise, with a visible trend back toward office-based work. One cloud-based accounting software company that adopted full remote work in 2020 later phased back to in-office work and ultimately required employees to come in five days a week.

The result was a Tokyo office market that took a hit—vacancy up, rents down—but also one where return-to-office pressures reasserted themselves earlier and more forcefully than many Western observers expected.

BOJ's Crisis Response

And then there was the backstop.

During the pandemic’s acute phase, the Bank of Japan doubled the limit of its J-REIT purchases to 180 billion yen. Research also found that the flow effect of the BOJ’s purchases increased during COVID—consistent with the idea that these interventions matter more when markets are stressed. Repeated countercyclical buying also coincided with lower stock market volatility.

For J-REITs, the practical impact was simple: when investors panicked, there was still a buyer in the market. That didn’t eliminate the fundamental questions hanging over offices, but it did reduce the risk of a self-reinforcing collapse in pricing and liquidity—the kind of spiral that can turn a temporary shock into a permanent impairment.

VIII. The Modern Era and Policy Normalization (2023-Present)

INFLECTION POINT #4: The End of an Era

As of December 2025, the long unwind is underway. After more than a decade in which extraordinary monetary policy sat quietly underneath asset prices, Japan is now watching that support get dialed back—carefully, and in full view of the market.

The pivotal turn came in March 2024, when the Bank of Japan ended new purchases of ETFs, a clear signal that the era of ever-expanding risk-asset buying was over. Then, on September 19, 2025, the BOJ’s policy board unanimously decided to begin selling its existing ETF and Japan Real Estate Investment Trust holdings.

Importantly, this wasn’t a sudden slam on the brakes. The BOJ laid out a phased approach designed to avoid shocking markets: selling ETFs at about 330 billion yen per year and J-REITs at about five billion yen per year—even as policy rates remained unchanged. The message was subtle but unmistakable: the BOJ was starting to step back, and it wanted to do so without setting off a chain reaction.

The governor also acknowledged the sheer scale of the problem. Unwinding could take more than a century at that pace, but moving faster could risk triggering a broader sell-off. That’s the trade-off when a central bank owns roughly 7% of the Japanese stock market through ETFs and about 5% of the J-REIT market.

As of mid-September 2025, the BOJ held around 80 trillion yen worth of ETFs and J-REITs. At current prices, those holdings carried an unrealized profit of roughly 44 trillion yen—an enviable position compared with other central banks whose post-crisis bond portfolios have often sat underwater. Even so, people familiar with the matter suggested BOJ officials were preparing to start selling ETFs as early as the following month, beginning a process expected to take decades.

Recovery and New Challenges

And yet—despite policy normalization—Tokyo’s office market didn’t crack. It bent, recovered, and in some pockets snapped right back into strength.

Japan’s economy rebounded after the acute phase of COVID, and Tokyo real estate followed. Companies that had given up space during the pandemic found themselves needing it again as employees returned and business conditions improved. Demand wasn’t just about “getting back to normal,” either. It was also expansion, relocation, and a push toward better buildings in better locations.

By late 2024, that strength started to show up in the data. Grade A rents recorded their largest quarter-on-quarter jump in a decade, while vacancy tightened meaningfully, with all-grade vacancy dropping into the mid-3% range and Grade A vacancy around the low-2% range in Tokyo’s five central wards. Leasing momentum was especially strong in the very heart of the market—Marunouchi and Otemachi—where rents rose fastest on the back of an extremely tight supply-demand balance.

Absorption across Tokyo’s 23 wards in 2024 exceeded one million square meters for the second year in a row, and vacancy fell sharply versus the end of 2023. Unless the economy takes a major turn for the worse, expectations going into 2025 were for demand to stay solid and vacancy to keep edging down. In a December 2024 survey focused on office demand in Tokyo’s core cities, a majority of respondents said they intended to lease more space, citing better locations, new departments, and headcount growth.

Current Market Position

Against that backdrop, the company focused on execution: attracting new tenants through targeted leasing efforts, and increasing satisfaction among existing tenants by adding value to its properties.

On the acquisitions side, the world has gotten more competitive, not less. Even with the BOJ normalizing policy, property acquisition appetite remained firm among both domestic and foreign investors—helped by the interest rate differential versus overseas markets. That demand kept competition intense for high-quality office buildings, pushing expected yields lower and making it harder to buy well.

The overall investment tape reinforced the point: investment in Japanese real estate rose sharply in the first nine months of 2024 versus the prior year, with estimates pointing to about 5 trillion yen for the full year.

Operationally, JRE continued to manage the portfolio actively—acquiring assets that met its standards and selectively disposing of properties that no longer fit. It also reported a dividend per unit of JPY 2,511 for the period, with payment scheduled for December 16, 2025, and noted that the acquisition of The Link Sapporo had been completed.

The big picture, though, is the new tension defining the post-Abenomics era: Tokyo offices are recovering, but the capital markets safety net is being rolled back—slowly, deliberately, and for the first time in years, in reverse.

IX. The Business Model Deep Dive

How JRE Makes Money

JRE’s business model is almost disarmingly simple: own great office buildings, collect rent, and send most of the cash back to unitholders. The sophistication is in how relentlessly it sticks to that plan.

Nearly all of JRE’s income comes from rental revenue generated by leasing its office properties. That focus matters. This isn’t a vehicle built to trade in and out of buildings or try to “call” the property cycle. The job is to build a portfolio that stays leased, stays relevant, and can grow cash flow steadily through tenant demand, smart renewals, and careful building management.

The tenant base is also built to avoid single-point failure. JRE’s tenants come from a wide range of industries, but the largest chunks of leased space come from service companies, information services, electric devices, and financial services firms. The diversification helps smooth out the bumps: if one sector hits a rough patch, the rent roll isn’t hostage to it. In practice, JRE’s performance ends up tied to the broader health of Japan’s white-collar economy—exactly where premium Tokyo offices tend to be most resilient.

Portfolio Strategy

If there’s one word that explains JRE’s portfolio strategy, it’s quality.

The emphasis on Grade A office buildings in Tokyo’s central business districts isn’t marketing. It’s a decision to compete where tenant demand is deepest, where buildings stay occupied longer, and where top assets tend to hold value better through downturns.

The Tokyo concentration can look like a risk from far away, but for JRE it’s the point. Tokyo is Japan’s commercial center. Companies that need proximity to financial markets, government institutions, and corporate headquarters still cluster there. That structural pull is why JRE has been willing to be geographically narrow while trying to be exceptionally selective inside that footprint.

And then there’s the sponsor advantage. With Mitsubishi Estate as the ultimate parent of JRE-AM, JRE benefits from a relationship that can be hard for competitors to match. When Mitsubishi develops or controls a premium office asset, JRE can be a natural acquirer in a way that an unaffiliated buyer often can’t replicate.

None of this makes buying easy. Competition for high-quality office buildings remains fierce, and acquisition conditions stay tough because expected yields are low. In that environment, JRE’s approach has been to keep making investments that fit its policy—aiming for sustainable growth in dividends to unitholders, even when the market makes that discipline harder.

The Asset Management Relationship

JRE also operates with a defining structural feature of the J-REIT system: external management.

The REIT outsources day-to-day investment and management to JRE-AM. The upside is obvious. JRE gets access to Mitsubishi Estate’s experience, relationships, and operating capabilities—expertise that would be difficult and expensive to replicate inside the REIT itself.

But the trade-off is just as real. External management can create misalignment if the manager’s incentives drift away from what unitholders want. In JRE’s case, those risks are meant to be constrained through governance and disclosure. The Tokyo Stock Exchange requires detailed reporting of related-party transactions, and investors can scrutinize whether the manager is acting in unitholders’ interests.

Ultimately, the question for any investor is whether sponsor access and operating strength outweigh the costs and potential conflicts of the structure. JRE’s long track record of steady growth and distributions suggests the balance has worked—so far. But it’s also a setup that only stays healthy if unitholders keep paying attention.

X. Investment Framework: Forces and Powers Analysis

Competitive Position Analysis

Threat of New Entrants: LOW

Building a true peer to JRE is hard—structurally, financially, and culturally.

Start with the rules. Unlike U.S. REITs, which can be internally or externally managed, J-REITs must be externally managed. That means any would-be competitor needs a licensed asset management company, real operating expertise, and the regulatory relationships to function inside a tightly governed framework.

Then there’s the capital reality. Premium Tokyo office towers cost billions of yen. Getting to meaningful scale isn’t just a matter of raising money—it’s getting access to the kind of assets that rarely show up in a clean, open auction.

And that leads to the biggest barrier of all: relationships. Japanese real estate runs on networks built over decades. Many of the best transactions happen through trust, history, and repeated partnerships. New entrants don’t just lack a portfolio; they lack a seat at the table.

None of this means the playing field is quiet. Competition for high-quality office buildings is fierce, and acquisition conditions remain tough because expected yields are low. But that’s different from saying new entrants can realistically appear and take share at the top end of the market.

In that environment, Mitsubishi Estate’s sponsorship is a moat. It gives JRE credibility, operational depth, and access that would take a newcomer years—more likely decades—to replicate.

Bargaining Power of Suppliers (Property Sellers): MODERATE-HIGH

The supply of truly premium Tokyo office buildings is limited, and the owners of those assets usually have options.

Many of these buildings sit on corporate balance sheets, or are held by institutions that don’t need to sell on anyone else’s timetable. If they do decide to transact, they can choose among other J-REITs, domestic institutions, private equity, and sovereign wealth funds. That optionality gives sellers leverage—especially when multiple well-capitalized buyers are chasing a narrow slice of the market.

Mitsubishi Estate helps here, because relationship-driven deal flow can create opportunities that don’t exist for everyone else. But even Mitsubishi can’t force transactions at prices that make sense for JRE’s unitholders. Pipeline access is an advantage, not a magic wand.

Bargaining Power of Buyers (Tenants): MODERATE

Tenant power in Tokyo offices is a balancing act.

On one side, top-tier tenants are sophisticated. They can shop across buildings, districts, and—at least in theory—other Asian business hubs. They also negotiate hard, especially on large blocks of space.

On the other side, the very best space in Tokyo’s core is finite. In the buildings that define “premium,” availability can be scarce, and the best assets don’t need to discount to stay relevant for long.

JRE’s diversification across industries also matters. No single tenant dominates the rent roll, which limits the leverage any one company can exert. And in the current environment—vacancy easing down and rents moving up—the balance tilts toward landlords.

Threat of Substitutes: ELEVATED

If the global financial crisis was a reminder that financing can disappear overnight, COVID was the reminder that demand can change shape.

Remote work is a real substitute for office space. Japan has moved back toward the office more than many Western markets, but the structural risk hasn’t gone away. Collaboration software keeps improving, and another shock—health-related or otherwise—could accelerate adoption again.

The counterpoint is that not all office space is equally substitutable. Premium space tends to be the last to be cut and the first to be upgraded into. Many companies don’t eliminate the office; they compress the footprint and trade up in quality. That dynamic is uncomfortable for commodity buildings, but it can favor a portfolio like JRE’s.

Competitive Rivalry: HIGH

Even if new entrants are unlikely, the incumbents fight hard.

The J-REIT market includes multiple office-focused vehicles, many backed by major developers, competing for the same rare acquisitions and the same blue-chip tenants. Nippon Building Fund—JRE’s fellow pioneer from 2001—remains a formidable competitor, alongside other well-capitalized sponsored REITs.

You see this rivalry most clearly in pricing. When many disciplined buyers pursue limited supply, yields compress and underwriting gets tight. You also see it in leasing: retaining and upgrading tenants becomes a constant effort, not a set-and-forget exercise.

Strategic Advantages

JRE’s durable advantages come into focus through Hamilton Helmer’s “7 Powers” framework:

Scale Economies: Scale helps—fixed costs spread across a larger portfolio—but it’s not decisive on its own. Several J-REITs are large enough to compete.

Network Effects: Not a major factor in real estate.

Counter-Positioning: JRE’s long-running commitment to premium Tokyo offices—quality over quantity, and selective concentration rather than broad diversification—functions as counter-positioning against strategies that chase growth more aggressively.

Switching Costs: Office moves are painful. Relocation is expensive, disruptive, and slow. That creates real tenant stickiness, especially among large companies that have invested heavily in build-outs and location.

Branding: The Mitsubishi Estate association carries weight in Japan’s relationship-driven corporate ecosystem. For many tenants, occupying a Mitsubishi-connected building is a signal of quality and stability.

Cornered Resource: The sponsor relationship and the resulting access to opportunities are a true differentiator—hard for competitors to replicate quickly, if at all.

Process Power: Two decades of operating a premium office portfolio creates compounding know-how: how to lease through cycles, maintain buildings at a high standard, and allocate capital without losing the thread of the strategy.

Key Performance Indicators for Investors

Instead of drowning in metrics, two indicators do the best job of capturing the core of the business:

1. Occupancy Rate: Occupancy is the engine. If JRE keeps buildings full (historically 97%+ for the portfolio), revenue stays durable. If it starts slipping, something is changing—either the market, the quality of the assets, or competitive position. Watch it quarterly, and watch it relative to peers.

2. Same-Property Rent Growth: This tells you whether the portfolio is getting stronger on its own. It isolates organic rent movement from acquisitions and sales. Positive growth suggests pricing power and healthy demand; negative growth suggests pressure—either from the market or from tenant negotiations.

Together, these answer the two questions that matter most: are the buildings full, and are tenants paying more or less than before? The rest—distribution growth, NAV, and total returns—tends to follow from there.

XI. The Bull and Bear Cases

The Bull Case

Tokyo’s structural advantages are easy to take for granted—until you compare it to markets that don’t have them.

Tokyo is still Japan’s undisputed capital and one of Asia’s most important financial centers. Government functions are there. Corporate headquarters are there. Finance and professional services are there. That clustering creates a kind of built-in demand for premium office space that secondary cities simply can’t replicate.

And unlike many global office markets that are still debating whether the office is optional, Tokyo has shown a more durable return-to-office dynamic. Japanese companies, on average, have been less willing to make remote work the default. The cultural and operational emphasis on face-to-face coordination continues to support office demand.

A second tailwind is what the post-pandemic market has turned into: a flight to quality.

Companies may trim total square meters, but they often reinvest what remains into better space—newer buildings, better amenities, stronger sustainability credentials, and locations that help with recruiting and client-facing work. That’s exactly where JRE lives. A portfolio concentrated in Grade A offices in Tokyo’s central business districts is positioned to benefit when tenants “trade up.”

You can see that recovery showing up in rents. Average office rents in Tokyo’s five central wards were rising again by early 2025, and the strength was most pronounced at the top end: Class A rents in those wards were higher at the end of the first quarter of 2025, up year on year.

Then there’s the fear hanging over the sector: Bank of Japan normalization.

The bull argument is that this is no longer a surprise. The BOJ has been explicit about moving slowly, with selling paced so gradually it’s measured in decades, not quarters. If the market has had years to anticipate that the BOJ will eventually step back, a lot of that anxiety may already be embedded in prices.

In the meantime, the structure of the vehicle itself offers support. J-REITs are designed to distribute the vast majority of earnings, and the 90%+ payout requirement means investors aren’t relying solely on price appreciation. Even in a sideways market, the cash yield is part of the total return.

Finally, there’s the advantage that has been there since day one: the sponsor.

Mitsubishi Estate brings credibility, operating expertise, and potential access to opportunities that are difficult for competitors to match. Over two decades, that relationship has become part of JRE’s identity—and part of why many investors see it as one of the category’s “core” holdings.

The Bear Case

The bear case starts with a macro shift Japan hasn’t had to contend with in a long time: rising interest rates.

Higher rates pressure real estate in two ways. They raise financing costs for REITs over time. And they increase the attractiveness of alternatives like government bonds relative to REIT yields. Even if leasing fundamentals stay healthy, valuations can still compress if the discount rate moves against you.

Next is the risk everyone wants to declare “solved,” but can’t: remote work.

Japan has returned to offices more fully than many Western markets, but that doesn’t make the risk disappear. A future crisis, a generational shift in work expectations, or simply better collaboration technology could push adoption higher again. JRE’s heavy concentration in office space makes that exposure meaningful.

There’s also the supply question. In the years after 2025, a sizable wave of new office supply is expected across Tokyo’s 23 wards. Even with strong current absorption, a surge in new buildings—paired with any economic slowdown—can shift negotiating leverage toward tenants, pressuring occupancy and rents.

Structurally, bears will also point to the external management model. Because the asset manager is paid based on assets under management, there’s an inherent incentive to grow. Governance and disclosure can mitigate that conflict, but they can’t erase it.

And then there’s the slowest-moving risk of all: demographics.

Japan’s population is aging and shrinking, which implies fewer workers over time and, potentially, less office demand. Premium Tokyo buildings may feel that pressure last, but “last” isn’t the same as “never.”

Finally, even if the BOJ sells gradually, selling is still selling.

The market spent a decade getting used to a powerful buyer sitting in the background. A visible shift from buyer to seller—even at a slow pace—can weigh on sentiment and valuations, if only because it changes the psychological floor investors thought they had.

XII. Myth Versus Reality

Myth: Japan's "Lost Decades" Mean Real Estate Is a Bad Investment

Reality: The “lost decades” were real—but they weren’t evenly distributed. JRE’s own history is the cleanest rebuttal: since 2001, it grew its assets roughly twelvefold. The lesson isn’t that all Japanese property was a winner. It’s that top-tier real estate, in the right location, with disciplined management, could still compound even when the broader macro story looked bleak.

Myth: Central Bank Support Was the Only Reason for J-REIT Success

Reality: The Bank of Japan’s buying mattered, especially during stress. But it didn’t create JRE from nothing. JRE was already building scale and credibility in the 2000s, well before the QQE era turned the BOJ into a structural holder of J-REIT units. Central bank support boosted liquidity and compressed risk premiums. It didn’t replace the fundamentals of owning desirable buildings and keeping them leased.

Myth: Remote Work Will Make Offices Obsolete

Reality: COVID forced the question, but Tokyo’s answer has been more resilient than the global “death of the office” storyline. Post-pandemic, Japan has seen a stronger return-to-office dynamic than many Western markets. In Tokyo’s prime office submarkets, vacancy began to ease back down and rents started rising again—especially for higher-quality space. The office didn’t disappear. It changed, and the premium end held up best.

Myth: External Management Is Inherently Inferior

Reality: External management can create real conflicts if incentives aren’t aligned, and investors are right to watch it closely. But in Japan, it’s also the standard structure—and in JRE’s case, it’s tied to a practical advantage: access to Mitsubishi Estate’s expertise, relationships, and operating playbook. JRE’s long track record suggests that, with governance and scrutiny, the benefits can outweigh the costs.

Myth: Rising Rates Will Crush REITs

Reality: Higher rates are a headwind—financing costs rise over time, and bond yields become more competitive. But rates don’t move in isolation. They often rise alongside stronger economic activity, which can support occupancy and rent growth. In other words, the relationship isn’t “rates up, REITs down.” For quality portfolios with real pricing power, the story can be more balanced—and the outcome far more nuanced.

XIII. What Matters Now

If you’re looking at JRE today, the story has shifted from “can this new structure work?” to “can the machine keep compounding without the training wheels?” A few things matter more than anything else:

The Return-to-Office Trajectory: Keep an eye on office attendance and, more importantly, what companies do with their leases. Are firms still expanding and upgrading space, or is the post-COVID rebound starting to cool? Recent rent momentum only lasts if demand stays real.

Interest Rate Path: Japan is living through something it hasn’t had to price for in a long time: the possibility of sustained rate increases. The key is how quickly borrowing costs move, and what that does to spreads between cap rates and financing costs.

New Supply Absorption: A meaningful wave of new development is coming. If the economy stays healthy, Tokyo can digest it. If growth slows, new buildings can tip the balance fast. Watch pre-leasing at the major projects and how vacancy behaves in newly delivered towers—that’s where pressure shows up first.

Competitive Dynamics: When deal markets get crowded, prices get stretched. Aggressive buying by peers can be a tell that underwriting is heating up. On the flip side, if financing tightens, distressed sales can appear—and disciplined buyers with liquidity can suddenly find the best opportunities they’ve seen in years.

Mitsubishi Relationship: JRE’s sponsor is a core part of the thesis. If that relationship strengthens, it can mean better access and deeper operational support. If it weakens, JRE loses a quiet advantage that’s been there since day one.

Zoom out, and the record is hard to ignore: more than two decades of operating history, a portfolio that expanded dramatically, steady distributions, and resilience through a global financial crisis, a major earthquake, and a pandemic that directly challenged the value of offices. JRE proved that premium real estate, in the right place, run with discipline, can still compound in an environment that looked like it should have made that impossible.

But the next chapter won’t be a rerun. The central bank bid that supported the asset class for years is now, slowly, being reversed. Interest rates are no longer a one-way bet. Remote work didn’t erase offices in Japan, but it did change the negotiation. All of that puts more weight on management decisions—leasing, capital allocation, and the discipline to not chase growth at the wrong price.

What JRE still has is position: premium assets in Tokyo’s best locations, a sponsor relationship with deep roots, and an operating playbook shaped by multiple cycles. In real estate, position is often destiny. Whether JRE’s position continues to translate into unitholder returns is the question that matters now.

Marunouchi’s buildings will keep standing, the way they have since Mitsubishi began reshaping the district in the 1890s. The real question is simpler—and harder: will they stay full, and will tenants keep paying more for the privilege? For JRE, that’s always been the test. So far, it’s passed.

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music