Nippon Building Fund: The Pioneer of Japanese Real Estate's Modern Era

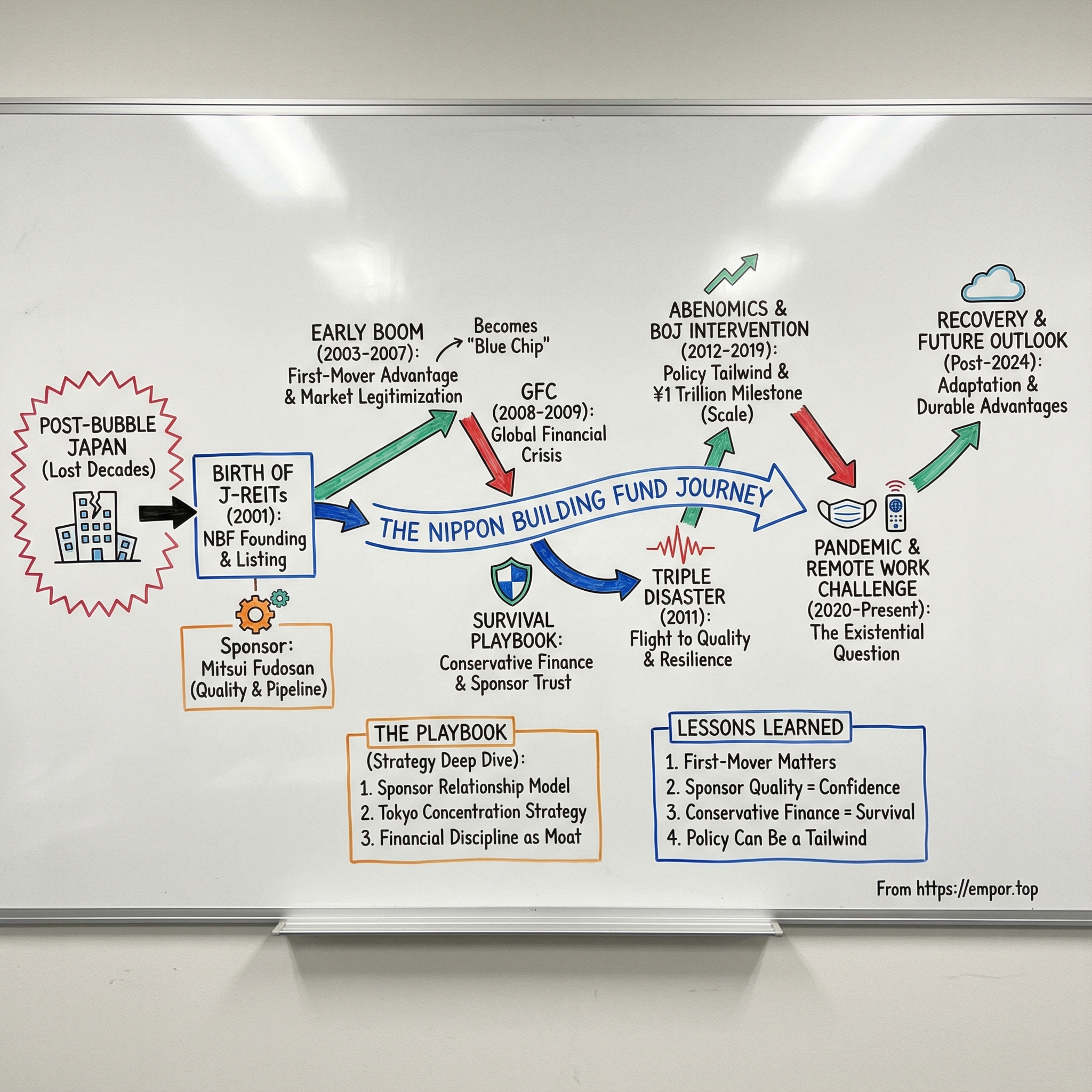

I. Introduction & Episode Roadmap

Picture the collision point between two forces that don’t usually share the same room: centuries-old Japanese corporate tradition and a brand-new piece of Wall Street-style financial engineering.

It’s September 2001. In Tokyo, two newly created real estate investment vehicles list on the Tokyo Stock Exchange, quietly launching what would become Japan’s REIT market. One of them is Nippon Building Fund. The timing is almost surreal: it happens right as global confidence is about to be rattled, and with Japan still trying to crawl out from the wreckage of its own property bubble.

NBF, short for Nippon Building Fund Inc., would go on to become Japan’s largest office-focused J-REIT, backed primarily by Mitsui Fudosan. What started as an unproven structure—asking investors to trust real estate again, but in a more transparent, tradable wrapper—eventually scaled into a trillion-yen giant. By 2024, it held more than 70 properties, with total acquisition cost over ¥1.2 trillion.

So here’s the real question: how did a financial product that originated in America’s tax code end up as one of the most important tools for rehabilitating Japan’s frozen, post-bubble real estate market? And what does NBF’s rise reveal about how durable advantages get built in a country famous for slow growth, risk aversion, and institutional inertia?

We’ll walk through five moments when the ground shifted under everyone’s feet: the birth of J-REITs in the aftermath of the Lost Decade; the global financial crisis that nearly broke the young market; the March 2011 triple disaster; the Abenomics era of radical monetary policy; and the pandemic shock that forced the world to ask whether offices were still necessary at all.

Through each of those chapters, NBF didn’t just make it through. It tightened its grip—benefiting from being early, being sponsor-backed, and being disciplined about financial risk when others couldn’t afford to be.

And if you’re a long-term investor, that’s the deeper promise of this story: a case study in how conservative leverage turns into offense during crises, how sponsor relationships shape destiny, and how—over decades—structural edges compound into something that looks inevitable in hindsight.

II. Setting the Stage: Japan's Lost Decade & The Birth of J-REITs

The Bubble and its Aftermath

To understand Nippon Building Fund, you have to start with the catastrophe that made it necessary.

Japan’s asset-price bubble didn’t just pop. It rewired the country’s relationship with property for a generation. At the peak, the numbers sounded like satire: land in central Tokyo traded at prices so extreme that the Imperial Palace grounds were famously estimated to be worth more than all the real estate in California. By 1990, Japan’s property market was valued at more than ¥2,000 trillion—roughly four times the total real estate value of the United States. Public companies were sometimes treated less like operating businesses and more like shells for land.

Then the Bank of Japan moved to cool speculation by raising interest rates, and the unwind was brutal. The Nikkei, which had screamed up to around 39,000 at the end of the 1980s, plunged to roughly 14,000 by 1991 and later fell to about 8,000 a little over a decade after that. Real estate followed the same arc. In a span of about 30 months in the early 1990s, Japanese investors and landowners saw about $2.5 trillion in asset value evaporate.

What people call the Lost Decade began in the 1990s—but the more accurate term became the Lost Decades, because the stagnation dragged into the 2000s and the 2010s as well.

And the pain didn’t stop just because prices had fallen. Even with the collapse visible by early 1992, the broader decline lingered for more than a decade. A huge pileup of non-performing loans followed, putting financial institutions under strain. Banks were stuck with mountains of toxic real estate exposure. Lending tightened, investment stalled, deflation set in, and what had once been Japan’s most trusted store of value became the thing dragging the entire system down.

The Intellectual and Policy Problem

This was the policy riddle: how do you restart liquidity in a frozen property market when banks can’t lend, corporations won’t invest, and consumers won’t spend? Traditional monetary policy was basically tapped out—rates were already close to zero. Fiscal stimulus could buy time, but it couldn’t fix the plumbing.

The solution Japan eventually embraced wasn’t invented in Tokyo. It was imported.

In the United States, Real Estate Investment Trusts had existed since 1960, when Congress created a pass-through structure that let everyday investors own pieces of large-scale commercial real estate. The bargain was straightforward: REITs would distribute at least 90% of taxable income to shareholders, and in return they’d avoid corporate-level taxation—so long as they operated with high transparency and a rules-based governance structure.

The obvious question is why Japan, with one of the largest property markets in the world, waited roughly four decades to adopt the model. A big part of the answer was cultural and structural: relationship banking, cross-shareholdings, and an historically opaque private market. But after the bubble, modernization stopped being an academic debate. It became a survival requirement.

The legal gate finally opened in November 2000, when Japan revised the Act on Investment Trusts and Investment Corporations to newly add real estate as an eligible investment asset class for mutual funds. Until then, negotiable securities had been the primary focus. That change effectively removed the ban on creating a Japanese version of a REIT—a J-REIT. The Tokyo Stock Exchange moved quickly, building a listing and delisting framework and establishing a dedicated J-REIT market in March 2001.

And that’s the new world NBF was born into: one where real estate could become liquid again—not through backroom refinancing and relationship deals, but through publicly traded securities.

The Sponsor Behind the Pioneer: Mitsui Fudosan

Now comes the twist. Nippon Building Fund didn’t emerge from a startup team or a government lab. It came with a sponsor that, in Japan, carries the kind of institutional gravity that’s hard to overstate: Mitsui Fudosan.

The lineage starts in 1673, when the Mitsui family opened the Echigo-ya kimono shop in Tokyo. Over centuries, that merchant business expanded into a sprawling conglomerate, and in 1941 its real estate arm became Mitsui Fudosan Co. The Mitsui name endured through the Tokugawa shogunate, the Meiji Restoration, World War II, and the Allied occupation’s breakup of the zaibatsu—then re-emerged as a cornerstone of modern Japanese business.

Mitsui Fudosan also had a track record of being early. Over the years, it sponsored Japan’s first REIT in 2001, developed Japan’s first factory outlet in 1995, helped bring Tokyo Disneyland in 1983, built Japan’s first regional shopping mall in 1981, and delivered what’s often described as Japan’s first office skyscraper in 1968.

That 1968 project—the Kasumigaseki Building—is worth pausing on, because it tells you what kind of sponsor Mitsui was. Completed in 1968, it’s widely regarded as the first modern office skyscraper in Japan: 147 meters tall and 36 stories. It only became possible after legal and regulatory changes, including revisions to the Building Standards Act, relaxed prior constraints—until then, building height had effectively been capped around 31 meters. Mitsui didn’t just take advantage of that shift; it proved it could execute institutional-grade projects that signaled a new era.

So by the time the J-REIT framework arrived, Mitsui Fudosan saw it as both an opportunity and a necessity. It held substantial real estate that needed capital recycling. A REIT would let Mitsui monetize completed assets, redeploy capital into new development, and still stay close to the buildings through the asset management structure.

For Japanese real estate, this was a genuine paradigm shift: away from opaque, relationship-based ownership and toward transparent, publicly listed securities.

And for investors, it sets up a key theme that will repeat throughout this story: in J-REITs, sponsor quality isn’t a branding detail. The sponsor influences the asset pipeline, the operating capability, and—when markets seize up—the odds of survival. Mitsui’s multi-century lineage wasn’t just a nice origin story. It became one of NBF’s most enduring strategic advantages.

III. The Founding: First to Market (2001)

The September 2001 Launch

Before there was a listed REIT, there was the machinery to run it.

Nippon Building Fund Management Ltd. (NBFM) was established in September 2000 to manage the assets of what would become Nippon Building Fund Inc. That sequencing mattered. It signaled that this wasn’t a rushed financial product slapped together to chase a headline—it was a purpose-built platform, designed to look and act like an institution from day one.

Nippon Building Fund Inc. itself was established on March 16, 2001. After months of preparation, it reached the moment that would effectively inaugurate the entire asset class: in September 2001, NBF became the first Japanese real estate investment corporation to list on the Tokyo Stock Exchange’s J-REIT section. From the start, it positioned itself around a simple promise—own high-quality buildings, run them professionally, and return profits to unitholders through stable distributions as the market matured.

And then, almost immediately, the world lurched.

The first two J-REITs listed—NBF and Japan Real Estate Investment Corporation—and the day after, the 9/11 terrorist attacks hit the United States. Markets globally went risk-off. Confidence vanished. For a brand-new product asking investors to believe in real estate again, the timing was punishing. But the listings held. The vehicles stayed in the market. And in doing so, they laid the first stones of what would become a modern, liquid real estate capital market in Japan.

Operationally, NBF started in May 2001 with 22 properties and a total acquisition price of ¥192.1 billion. This wasn’t a “let’s see what we can scrape together” portfolio. It was seeded with assets drawn from Mitsui’s holdings—properties that carried the sponsor’s stamp and gave investors a reason to take the structure seriously. From there, NBF began the slow, steady work that would define its early era: continuous acquisitions, portfolio expansion, and proving—distribution by distribution—that the model could work.

The Strategic Bet: Office-Focused, Tokyo-Centric

Plenty of new REITs diversify to reduce perceived risk. NBF went the other way. It pursued unitholder value by building a highly competitive portfolio primarily in Tokyo’s 23 wards.

On the surface, that looked like a bold call in a country still scarred by a real estate collapse. Why concentrate in Tokyo offices when “Japanese property” had become shorthand for pain? Because the bet wasn’t on Japan’s broad macro story. It was on Tokyo’s structural role. Tokyo wasn’t just another city—it was the corporate control room. Multinationals still needed a Tokyo footprint. Domestic companies still needed headquarters space. Even in a sluggish economy, the best buildings in the best locations tended to keep tenants.

There was also a pragmatic edge to the strategy: Mitsui’s deepest expertise was in Tokyo office development and management. Spreading into other property types would have meant competing in sectors where other sponsors had sharper tools. NBF chose to be exceptional in one arena rather than average in many.

And it wasn’t doing it alone. Asset management was carried out by drawing on the know-how of NBFM’s shareholders, including Mitsui Fudosan, Sumitomo Life Insurance, Sumitomo Mitsui Trust Bank, and Sumitomo Mitsui Banking Corporation. That cap table wasn’t just window dressing. Bringing major financial institutions into the circle strengthened credibility and, just as importantly, helped create financing relationships that would matter when markets eventually tightened.

Early Portfolio Construction

Of course, a sponsor relationship is a double-edged sword.

Mitsui could provide a powerful pipeline of institutional-quality assets, often at moments that made sense for capital recycling. But that same dynamic raises the question every sponsor-backed vehicle has to answer: who is this really for—the unitholders, or the sponsor?

NBF’s response was governance. It worked to build credibility through transparent processes and checks on related-party transactions. Mitsui remained a key source of assets, but pricing and timing still had to withstand scrutiny. Independent directors reviewed transactions, and the structure aimed to make the relationship feel like an advantage without letting it become a liability.

That mattered because the early 2000s were not a time of easy belief. Japanese investors still had fresh memories of the crash. Foreign investors had long memories of reform promises that fizzled out. NBF didn’t get trust for free—it had to earn it through consistent execution.

And it would have to earn it fast, because the market cycles ahead weren’t going to be gentle.

IV. The Early J-REIT Boom & Market Legitimization (2003-2007)

The J-REIT Market Takes Shape

After NBF’s debut, something rare happened in Japan’s post-bubble real estate world: momentum built. Slowly at first, then all at once. New J-REITs came to market, borrowing the basic template NBF helped prove out. Trading picked up. A sector that had felt like an experiment started to feel like an investable market.

Two markers signaled that this wasn’t just a niche product anymore. In May 2004, J-REITs were included in the MSCI Japan Index for the first time—an important step because index inclusion effectively turns a product into a default allocation for a huge pool of global capital. Then, by February 2005, the J-REIT market’s total value reached ¥1 trillion. In other words: this was no longer a curiosity. It had reached critical mass.

Foreign institutional investors, in particular, leaned in. For decades, “buying Japanese real estate” often meant navigating opaque information, relationship-driven dealmaking, and the friction of owning buildings directly. J-REITs flipped that. Now you could get exposure through a listed vehicle with regular disclosure and daily liquidity—Japanese property, finally packaged in a form global capital understood.

The Virtuous Cycle

This is where being first really started to pay.

As one of the earliest—and quickly one of the largest—J-REITs, NBF became a natural home for institutional money. More attention meant more analyst coverage. More coverage meant more trading. More trading meant better liquidity. And better liquidity made it even easier for large investors to choose NBF as their entry point into the category.

That flywheel mattered because REITs don’t grow like operating companies. Their core product is a portfolio, and the main engine is external growth: raise capital, buy properties, repeat. When a REIT’s units trade at a premium valuation, it can issue new units and buy buildings in a way that is accretive for existing unitholders. During the mid-2000s upswing, NBF’s standing as the sector’s “blue chip” made that playbook easier to run—and harder for smaller, thinner-traded peers to match.

Mitsui’s role got more valuable as the market heated up. A sponsor with deep inventory and development capability isn’t just a logo on the prospectus; it’s a pipeline. Mitsui could keep supplying institutional-quality assets, and NBF’s team—drawing heavily on Mitsui’s experience—made acquisition decisions with the kind of street-level understanding that only comes from living inside Tokyo’s office market.

By 2007, NBF had earned a clear identity: the flight-to-quality choice in Japanese listed real estate. If you wanted J-REIT exposure with scale, liquidity, and a sponsor name that carried real weight, you bought NBF. And the premium investors were willing to pay reflected a simple belief: in a young market, structure and credibility can be advantages every bit as real as location.

V. Inflection Point: The Global Financial Crisis (2008-2009)

The Lehman Shock Hits Japan

Then came the moment that separated “a promising new market” from “a real market”: a real panic.

The global financial crisis hit Japan’s young J-REIT sector with brutal speed. In October 2008, New City Residence Investment Corporation, a residential J-REIT, failed—becoming the first J-REIT bankruptcy. It wasn’t just one fund going down. It was proof that this shiny new structure could break.

The Tokyo Stock Exchange REIT Index plunged, eventually hitting 704.46—its lowest level since the index began. Confidence evaporated. Funding dried up. And suddenly the question hanging over every listed real estate vehicle was painfully simple: can you refinance when nobody wants to lend?

That’s the hidden fragility of a REIT. To keep their tax-advantaged status, REITs distribute almost all taxable income. They aren’t built to hoard cash. So when debt comes due, you refinance. When you want to grow, you issue equity. If credit markets seize and unit prices collapse at the same time, the whole model gets squeezed at both ends.

The Funding Crisis

Japanese authorities quickly saw the danger. If J-REITs started failing in a chain reaction, the damage wouldn’t stay contained inside the stock market—it could spill back into the underlying property market and into the broader economy. So the government created the Real Estate Market Stabilization Fund, designed to provide emergency liquidity and prevent a downward spiral.

Even the signal mattered. The announcement effect was meaningful because it told investors there was a backstop. The message wasn’t “everything is fine.” It was “we’re not going to let this new market die in its crib.”

At the same time, the industry began reorganizing itself. In January 2009, progress was made toward establishing a system that enabled mergers among J-REITs. The first merger closed in February 2010, and more followed—seven mergers closed in 2010 alone. By the end of November 2011, the number of listed J-REITs had fallen to 34.

The pattern was predictable: the most stretched vehicles—too much leverage, weaker assets, or thin sponsor support—were forced into consolidation or failure. The ones that made it through came out with more share, more credibility, and a far clearer sense of what “survivable” actually meant in this business.

NBF's Survival Playbook

For Nippon Building Fund, the crisis turned conservative finance from a nice-to-have into the whole game.

NBF’s approach had been deliberately cautious: moderate leverage, a heavy tilt toward long-term fixed-rate borrowing, and relationships across multiple banks. That preparation didn’t make the crisis pleasant—but it made it navigable. While other J-REITs scrambled to refinance in a market that suddenly had no appetite for risk, NBF’s lending relationships held.

And once panic set in, “flight to quality” stopped being a cliché and started being the organizing principle of the market. Investors drew a hard line between vehicles backed by prime assets and stable sponsorship, and everyone else. Tenants did something similar. In uncertain times, corporate decision-makers care more about landlord stability, building quality, and long-term reliability. NBF’s prime Tokyo office portfolio benefited from that shift.

The Mitsui relationship mattered here too—not as a direct rescue mechanism, but as credibility. NBF’s structure didn’t allow Mitsui to simply step in and bail it out. Still, the market understood what a flagship, sponsor-backed vehicle represents: a long-term commitment, operational depth, and a sponsor with every incentive to protect its reputation.

The crisis also punished a specific kind of behavior from the boom years. REITs that had chased growth by overpaying for assets in 2006 and 2007 walked into the downturn with inflated values and fewer options. NBF’s more selective approach—prioritizing quality over sheer expansion—meant it held up better than many peers.

The takeaway from 2008 and 2009 is blunt. For REITs, conservative leverage isn’t just prudence; it’s survival. Sponsor quality isn’t marketing; it’s confidence at the exact moment confidence disappears. And the advantages of being early—scale, liquidity, institutional trust—become most valuable when the rest of the market is forced into retreat.

VI. Inflection Point: The Great East Japan Earthquake (2011)

March 11, 2011: The Triple Disaster

On March 11, 2011, a magnitude 9.0 earthquake struck off the coast near Sendai and triggered a national trauma Japan hadn’t faced since World War II. The quake itself caused widespread destruction. Then came the tsunami that tore through coastal towns. And finally, the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear accident—an unfolding crisis that would alter Japan’s energy policy for years.

The timing couldn’t have been worse for listed real estate. The J-REIT market had only just started to regain its footing after the global financial crisis when this second shock hit. Risk appetite vanished again. Foreign investors, already cautious about Japan exposure, rushed for the exits, and the Tokyo Stock Exchange REIT Index dropped sharply in the immediate aftermath.

But in the middle of the panic, the earthquake changed the conversation in a way that mattered enormously for Tokyo office REITs. Overnight, “building quality” stopped being a brochure claim and became a board-level requirement. Japanese companies started asking different questions: How resilient is the structure? What does business continuity look like? Can our people work here safely after a major event?

The Tokyo Office Narrative

That shift played directly into Nippon Building Fund’s hand.

NBF’s portfolio was concentrated in central Tokyo and skewed toward newer, institutionally managed buildings built to Japan’s stringent seismic standards. In a market suddenly obsessed with resilience, tenants became less focused on shaving rent and more focused on specifications. The premium for modern, well-located, seismically sound Grade A space widened—because in that moment, “quality” had a measurable meaning.

The disaster also reinforced a broader pattern: the gravitational pull of corporate headquarters toward central Tokyo. When crisis response demands clear command and coordination, the logic of scattered regional footprints weakens. Some companies that had decentralized during the Lost Decade’s cost-cutting years began rethinking whether dispersion really made them safer—or simply harder to manage when it mattered.

Investor behavior during this period is also telling. During both the 2008 crisis and the 2011 earthquake, foreign investors accounted for more than half of trading volume. That kind of dominance can push prices away from fundamentals in the short run, amplifying volatility. It also creates openings for domestic investors with longer time horizons—and better instincts for what actually happens to occupancy and rents in Tokyo.

For NBF, the operational proof point was simple: its buildings held up. There was no significant structural damage across the portfolio. And as tenants watched which landlords were prepared and competent under stress, relationships deepened. The “quality premium” that had always been implied in NBF’s positioning became much easier for the market to justify in real time.

The earthquake’s lesson is one that travels well beyond real estate: stress reveals what’s real. Assets that perform when conditions are extreme, and institutions that keep operating when others freeze, earn trust in a way no boom period can manufacture.

VII. Inflection Point: Abenomics & BOJ Intervention (2012-2019)

The Abenomics Revolution

After the earthquake, Japan didn’t just need repairs. It needed a reset.

When Shinzo Abe returned to the prime minister’s office in December 2012, the country was staring down the prospect of yet another lost decade unless something broke the cycle of weak growth and stubborn deflation. What followed became known as Abenomics: the Liberal Democratic Party’s policy program after the 2012 general election, named for Abe (1954–2022), who served as prime minister from 2012 to 2020 and became the longest-serving prime minister in Japanese history.

Abenomics was framed as “three arrows”: monetary easing from the Bank of Japan, fiscal stimulus through government spending, and structural reforms aimed at lifting long-term growth and encouraging private investment. The program included a 2% inflation target, measures aimed at reversing excessive yen appreciation, negative interest rates, aggressive quantitative easing, expanded public investment, and even changes to the Bank of Japan Act.

But if you’re telling the story of J-REITs, one arrow matters more than the others. Monetary policy.

In April 2013, the Bank of Japan made its most dramatic move yet, launching its “quantitative and qualitative monetary easing” framework with the explicit goal of hitting 2% inflation in a stable manner within about two years. For real estate—and especially listed real estate—this was the start of a very different era.

The BOJ Becomes a J-REIT Buyer

What made the BOJ’s shift so important for J-REITs wasn’t just lower rates. It was what the central bank was willing to buy.

Back in October 2010, the BOJ kicked off a “comprehensive easing policy,” placing more emphasis on credit easing than in its earlier quantitative easing efforts. Crucially, it broadened the menu beyond government bonds to include risk assets like lower-rated private bonds, ETFs, and J-REITs.

That meant the Bank of Japan began purchasing ETF and REIT shares in October 2010 as part of its Large-Scale Asset Purchase program. Under the later QQE regime, it expanded those purchases substantially—eventually holding equity ETFs corresponding to about 5% of total Tokyo Stock Exchange market capitalization and around 3% of all REIT shares.

By global standards, this is almost unheard of. The BOJ wasn’t just setting the price of money and buying government bonds. It was stepping into public markets and purchasing equity-like securities backed by income-producing real estate.

And that had a very real, very practical consequence: it changed the psychology of the market. When J-REIT prices dropped sharply, the BOJ could show up and buy. In periods of stress, that acted like a floor under prices—effectively a backstop that reduced perceived downside risk and made the sector feel more survivable.

Against a backdrop of low and stable long-term yields, solid domestic real estate conditions, and broader global monetary easing, J-REIT valuations found support that wasn’t only about fundamentals. It was also about policy.

NBF's Trillion-Yen Milestone

For Nippon Building Fund, this was the era where “blue chip” stopped being a label and started being scale.

In January 2014, NBF executed a 2-for-1 unit split, improving liquidity and making the units more accessible to a broader investor base. But the bigger moment was symbolic and structural: NBF became the first J-REIT to surpass ¥1 trillion in assets, cementing its role as the category’s flagship.

Then came the ultimate stamp of legitimacy. In April 2014, the Government Pension Investment Fund—Japan’s enormous, famously conservative national pension manager—began investing in J-REITs. For NBF, GPIF’s participation wasn’t just new demand. It was institutional validation: the country’s most cautious long-term allocator was now willing to own listed real estate.

By November 2014, the entire J-REIT market reached roughly ¥10 trillion in market capitalization. In a little over a decade, Japan had gone from two tentative listings to one of the world’s largest REIT markets, second only to the United States.

The Abenomics period is the cleanest illustration in this story of how policy tailwinds can reshape an asset class. BOJ purchases helped damp volatility, compress yields, and support valuations—but they also raised a question that never really goes away once a central bank enters your market: is the price still purely the market’s judgment, or partly the consequence of an outsized buyer with non-financial goals?

That question only grew louder years later. After purchasing J-REIT investment units since October 2010, the BOJ announced in March 2024 that it would stop making new purchases.

VIII. Inflection Point: The COVID-19 Pandemic & Remote Work Challenge (2020-Present)

The Existential Question for Office REITs

Then, in 2020, the shock wasn’t financial or physical. It was behavioral.

COVID forced the world into a live-fire experiment: what happens if millions of people simply stop commuting? For office REITs everywhere, the fear was existential. If remote work became permanent, the core assumption behind office real estate—that companies need centralized space—would weaken, maybe even break.

Japan did move. Remote work rose sharply over the pandemic period, climbing from 13.3% in 2016 to 27% in 2021, and staying elevated at 30.7% in 2023.

Markets reacted instantly. In the pandemic’s early days, J-REIT prices fell hard. The TSE REIT Index dropped from 2,250.65 on February 20, 2020 to 1,145.53 on March 19—nearly cutting in half in less than a month. The message from investors was clear: if offices are optional, office REITs are vulnerable.

Japan's Unique Response

But Japan didn’t follow the Western script.

According to a survey by the Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, Transport and Tourism, the share of teleworkers nationwide slipped from 27% in 2021 to 24.8% in 2023. The Tokyo area stayed higher—over 30%—but the broader trend was a slow retreat from peak remote work.

Why? Part of it was structural, and part of it was cultural. In the same survey, many people pointed to company policy (38.3%) and jobs requiring face time (50.0%) as key reasons for not teleworking. Japanese organizations still rely heavily on in-person communication: consensus-building, hierarchical decision-making, and the kind of informal coordination that doesn’t translate cleanly to video calls. Even paperwork played a role—the hanko seal system, only recently reformed, long made physical presence a practical necessity for routine approvals.

And even where remote work existed, companies began tightening it. A Tokyo Metropolitan Government survey found that by December 2024, 43.7% of companies with 30 or more employees had remote work policies, down from 52.4% in 2022 and 46.1% in 2023.

The Recovery and Current Positioning

By late 2024, the Tokyo office market looked far healthier than many people expected back in March 2020.

In Q4 2024, the All-Grade vacancy rate fell 0.5 percentage points quarter-on-quarter to 3.5%, dropping below 4% for the first time in three years. Net absorption came in strong at about 50,000 tsubo—roughly 20% above the prior quarterly average.

Pricing followed occupancy. Grade A rents rose 2.0% quarter-on-quarter, the biggest single-quarter increase since Q2 2015. Leasing momentum was especially strong in Marunouchi and Otemachi, where rents climbed 3.3% quarter-on-quarter amid an extremely tight supply-demand balance.

COVID also accelerated a familiar theme in this story: flight to quality. Companies became more intentional about what the office was for. Many put renewed emphasis on headquarters as a hub for collaboration, internal communication, and employee engagement—and as a command center in an emergency. As a result, demand was expected to grow for properties with both hard features and soft features that support corporate growth.

Nippon Building Fund kept executing through the turbulence. On October 1, 2024, NBF implemented a five-for-one split of its investment units. The forecasts for distributions for the 47th and 48th fiscal periods were presented on a post-split basis. NBF framed the move as a way to improve accessibility and liquidity, aligning with the new Nippon Individual Savings Account scheme and Tokyo Stock Exchange recommendations. The split increased outstanding units from 1,700,991 to 8,504,955 and raised the total number of issuable units to 20 million.

More than anything, the split read as a signal: management was planning for a broader investor base and a long runway, not a retreat. In REIT land, you don’t make your units easier to buy if you think the core product is headed for obsolescence.

IX. The Playbook: Business Model & Strategy Deep Dive

The Sponsor Relationship Model

By the time Nippon Building Fund Inc. listed in September 2001, the headline was “first J-REIT.” The real story was the machinery behind it: a sponsor relationship designed to keep the vehicle fed with assets, expertise, and credibility through cycles.

NBF, founded in March 2001, has Mitsui Fudosan Co., Ltd. as its main sponsor. That relationship shows up in three practical ways.

First is the asset pipeline. Mitsui develops and owns buildings that can later be sold into NBF. For the REIT, that can mean a more reliable stream of acquisition opportunities—often in the exact locations and quality tier NBF wants—than a standalone buyer would typically see.

Second is operating and management know-how. Through Nippon Building Fund Management (NBFM), the Fund’s asset management is carried out with an explicit focus on proper management and collaboration with stakeholders, with the goal of improving mid-to-long-term investment returns for unitholders. In a business where small operational decisions compound—leasing, tenant relationships, capex timing—experience matters.

Third is reputational gravity. Mitsui can’t guarantee NBF’s obligations. But markets aren’t naive: they understand that Mitsui’s brand is tied to NBF’s performance. A sponsor that lets its flagship REIT stumble doesn’t just hurt one vehicle; it damages its own credibility and future access to capital.

Of course, sponsor-backed structures come with a built-in conflict: the sponsor wants to recycle capital and sell assets; unitholders want disciplined pricing and strong returns. NBF addresses that tension with guardrails. Related-party transactions are reviewed by independent directors. Acquisition pricing is checked against third-party appraisals. And disclosure requirements force transparency—making it harder for the relationship to drift into self-dealing.

The Tokyo Concentration Strategy

If the sponsor relationship is the plumbing, Tokyo is the bet.

NBF’s stated aim is steady asset growth and stable earnings over the mid-to-long term. In practice, that has meant a portfolio centered on office buildings and building sites in central Tokyo, with additional exposure to other parts of Tokyo and regional cities.

The logic is that Tokyo isn’t just big—it’s concentrated. Looking ahead, Tokyo’s five central wards—Chiyoda, Chuo, Minato, Shinjuku, and Shibuya—are expected to account for the vast majority of new supply from 2025 to 2029, broadly in line with the share they represented over the decade leading up to 2024. In other words, even new construction keeps reinforcing where the market’s center of gravity already is.

And that center of gravity remains stubbornly durable. Predictions of decentralization come and go, but corporate headquarters continue to cluster in central Tokyo. The reasons are old-fashioned and structural: deep talent pools, dense supplier and customer networks, and the prestige that still comes with a top-tier Tokyo address. For multinationals, a credible Tokyo presence often isn’t optional—it’s table stakes.

The trade-off is obvious, and management accepts it: limited diversification. If the Tokyo office market weakens, there’s no easy offset elsewhere in the portfolio—no meaningful geographic hedge and no property-type mix designed to zig when offices zag. NBF is effectively saying, “We’d rather be best-in-class in the core market than average everywhere.”

Financial Discipline as Competitive Moat

The third leg of the playbook is less glamorous, but it’s the reason NBF has been able to stay aggressive when others get defensive: conservative finance.

NBF targets a loan-to-value ratio of 36–46%, leaving meaningful equity cushion if property values fall. It also targets long-term fixed-rate borrowings of 80% or higher, prioritizing predictability over optimization.

That discipline comes with real costs. More leverage can juice distributions in calm markets, but it also turns refinancing into a life-or-death event during downturns. Fixed-rate, long-term debt can be more expensive than floating-rate options in the moment, but it reduces the risk of being forced into higher costs at exactly the wrong time.

Across the crises in this story, the payoff has been consistent: resilience becomes flexibility. When funding conditions tightened in 2008 and 2009, NBF’s relationships with banks were steadier than those of more stretched peers. And as interest rates eventually normalize, having borrowing costs locked in for longer can turn from “slightly conservative” into a genuine competitive edge.

X. Porter's Five Forces & Hamilton's Seven Powers Analysis

Porter's Five Forces

Threat of New Entrants: LOW

Starting a listed J-REIT isn’t like launching a new fund in a week. You need a regulatory framework you can comply with, meaningful upfront capital, and—most importantly—a sponsor setup that can reliably supply assets and operating capability.

What’s interesting is where new entrants have chosen to go instead. From 2020 to 2025, only two new J-REITs listed, while nearly 30 private REITs began operating. In 2024 and 2025 alone, seven private REITs started up, while only one new J-REIT had listed by the end of September 2025. In other words: most newcomers are avoiding public markets entirely, which lowers direct competitive pressure on incumbents like NBF.

And even if someone did want to challenge NBF head-on, NBF’s head start compounds. Decades of institutional investor relationships, analyst coverage, index inclusion, and the credibility that comes with allocations like GPIF’s are not things a new entrant can replicate quickly.

Bargaining Power of Suppliers (Property Sellers): MODERATE

NBF’s Mitsui relationship is a real advantage here. It can create a steadier pipeline of high-quality assets and reduce reliance on whatever happens to be for sale in the open market.

But “moderate” is the right label because the best Tokyo office buildings are always fought over. Other J-REITs, private funds, and deep-pocketed institutional capital all compete for the same small set of premium assets. And because the supply of Grade A office space in central Tokyo is limited, sellers tend to have leverage when a truly top-tier property comes to market.

Bargaining Power of Buyers (Tenants): MODERATE-HIGH

Large corporate tenants can negotiate—especially when markets soften. Since the pandemic, that negotiating posture has also shifted toward flexibility: shorter lease terms, options to expand or shrink, and buildings that offer more than just square meters.

NBF’s portfolio helps counterbalance that. High-quality, well-located buildings can still command premium rents and tend to attract more stable tenant demand, which limits how far tenant leverage can go. But the direction of travel is clear: tenants are more demanding than they used to be.

Threat of Substitutes: INCREASING

Remote and hybrid work are a partial substitute for office demand, and co-working and flexible space can substitute for traditional long leases.

Japan’s office market, though, has a buffer that many Western markets don’t: remote work adoption has faced cultural resistance, and Tokyo remains a magnet for talent and corporate headquarters. The workforce in Tokyo has been increasing, which implies that many companies may still need more high-quality space over time, not less. And with labor competition intense in Tokyo, moving into a premium office—with better facilities and a better location—can be one of the more straightforward ways to attract and retain employees.

Competitive Rivalry: MODERATE

There are multiple office-focused J-REITs competing for similar assets and similar tenants, and the battleground is predictable: building quality, location, and sponsor strength.

As the Japanese REIT market has matured into one of the world’s largest by market capitalization, competition has naturally become more professional and more intense. Even so, NBF’s scale and brand give it durable advantages: it can finance efficiently, it can transact in size, and it can stay top-of-mind as the “default” exposure for investors who want blue-chip Tokyo office real estate.

Hamilton's Seven Powers

Scale Economies: STRONG

At over a trillion yen in assets, NBF gets to play a different game. Scale can translate into a lower cost of capital through stronger credit positioning and more favorable financing terms. It also means fixed management costs get spread across a larger portfolio, and liquidity and analyst coverage tend to follow size—advantages that reinforce each other over time.

Network Effects: LIMITED

Office real estate doesn’t have classic network effects. Tenants pick buildings for location, quality, and suitability—not because a particular “network” of other tenants is there (even if some industries do value proximity to peers). So this isn’t a major driver of NBF’s advantage.

Counter-Positioning: MODERATE (Historical)

In 2001, the J-REIT structure itself was counter-positioned against Japan’s traditional real estate market: opaque ownership, relationship-driven transactions, and limited liquidity. J-REITs offered transparency, tradability, and institutional governance—features that appealed to investors who wanted a cleaner way to own Japanese property.

That edge has faded as J-REITs became mainstream. But being the pioneer still matters: NBF helped set expectations for what “institutional-grade” looked like in this market, and that heritage continues to support its positioning.

Switching Costs: MODERATE

For tenants, switching is painful: lease penalties, fit-out costs, and business disruption make relocation a serious decision. That creates real stickiness and gives landlords an advantage in retention.

For unitholders, there’s basically no switching cost—investors can rotate between J-REITs instantly. That limits how “locked in” NBF’s investor base can ever be.

Branding: STRONG

The NBF name, combined with the Mitsui brand, signals stability. Being first, staying large, and performing through multiple crises builds a reputation that shows up as investor trust—and often, valuation. In a sector where downside risk is dominated by confidence and financing, that kind of brand equity is hard to manufacture quickly.

Cornered Resource: MODERATE

The sponsor pipeline is the core “cornered resource” here. Mitsui’s ability to originate and own development assets can provide NBF with access that competitors can’t easily match.

And in Tokyo, location itself is a finite resource. Prime sites don’t multiply. Add long-standing tenant relationships and the informational advantages that come with operating at the center of the market, and you get a set of resources that can endure.

Process Power: MODERATE

Day-to-day execution matters in office real estate: tenant service, building operations, and the steady work of keeping properties desirable year after year. NBFM emphasizes customer-oriented asset management, aiming to provide comfortable office environments and build tenant satisfaction and trust.

That’s where Mitsui’s accumulated property management know-how becomes an advantage. You can copy a strategy deck. It’s much harder to replicate operational capability and process discipline that’s been built over decades.

XI. Bear Case vs. Bull Case

The Bear Case

The office bear case starts with a simple, uncomfortable idea: demand might not just be cyclical. It could be structurally lower. Hybrid work has permanently reduced the space many organizations need, and even Japan’s well-known resistance to remote work may soften over time as younger workers bring different expectations into the system.

Then there’s demographics. Japan’s working-age population is shrinking, which ultimately means fewer companies expanding, fewer teams hiring, and fewer tenants needing more space. Over the long arc, the economy has been getting smaller too: from 1995 to 2025, nominal GDP fell from $5.55 trillion to $4.27 trillion. A smaller economy doesn’t automatically mean empty offices, but it does put a ceiling on long-term demand growth.

Rates are the next pressure point. J-REITs have lived in an ultra-low-rate world for more than a decade. If rates normalize, valuations can take a hit: cap rates rise, property values fall, and the premium investors have historically paid for “blue-chip” names like NBF can compress.

Finally, even great landlords can’t ignore the supply cycle. After 2025, new office supply in Tokyo’s 23 wards is expected to total 4.59 million square meters over five years. Big development waves don’t have to break the market, but they do test it—especially if demand slows, or if tenants use new choices as leverage to upgrade into newer buildings and leave older stock behind.

One more signal of skepticism is already visible in the market. J-REITs are trading at an average discount of about 20% to NAV based on appraisal values. That’s a large gap between what public markets are willing to pay and what property appraisals imply—especially since real estate transactions have remained healthy and cap rates have stayed steady even with the prospect of BOJ tightening. In effect, equity investors are pricing in future stress that private-market valuations haven’t fully reflected yet.

The Bull Case

The bull case is that Japan is not the U.S. or Europe—and Tokyo is not a typical office market. Cultural and organizational realities still push many companies toward in-person work, and the “return to office” trend, paired with competition for talent, is encouraging employers to invest in offices that employees actually want to show up to.

The recent data supports that resilience. In 2024, absorption in Tokyo’s 23 wards reached 1.13 million square meters, topping 1 million for the second year in a row. Vacancy fell to 3.7%, down 2.1 percentage points from the end of 2023.

And if the market’s moving toward “less space overall, but better space,” that’s where NBF tends to win. Flight to quality has been the recurring motif of this entire story—2008, 2011, COVID—and it remains the most intuitive path for a premium Tokyo office portfolio. In a December 2024 survey on office demand across Tokyo’s 23 core cities, 58% of responding companies said they intended to lease more office space.

On policy, normalization doesn’t necessarily mean shock. Japanese authorities have strong incentives to move slowly, and a gradual path limits refinancing risk—especially for conservatively managed REITs like NBF.

Finally, Tokyo’s role as an Asia-Pacific business hub still holds. Regional competition from Singapore, Hong Kong, and Shanghai is real, but Tokyo continues to offer scale, infrastructure, and regulatory stability that keep corporate presence anchored.

Key Metrics to Track

For investors monitoring NBF’s performance, three metrics deserve the closest attention:

-

Occupancy rates and rent reversions: These are the fastest read on real demand. Positive rent reversions on renewals signal pricing power; negative reversions suggest tenants are gaining leverage.

-

NAV premium/discount: The spread between unit price and NAV captures market expectations. Persistent discounts can create opportunity—or warn that investors expect weaker fundamentals ahead.

-

Tokyo Grade A office vacancy rates: This is the macro temperature check. In the C5W, Grade A vacancy fell to 2.3%, down 0.8 percentage points quarter-on-quarter and 0.9 year-on-year. Large-scale Grade B rents rose 1.6% quarter-on-quarter and 4.1% year-on-year. When vacancy sits below 3%, landlords typically have the upper hand on pricing.

XII. Lessons for Founders & Investors

Lesson 1: First-Mover Advantage in Market Structure

Nippon Building Fund’s edge wasn’t just that it listed first. It’s that it listed first and then behaved like an institution from day one—building trust, showing up quarter after quarter, and making the new structure feel real.

That first-mover position compounded for nearly 25 years. Early relationships with institutional investors, analysts, and index providers created a default choice in a category that barely existed. The broader takeaway goes well beyond real estate: when a new market structure appears, being early matters—but competent execution is what turns “early” into “enduring.”

Lesson 2: Sponsor Quality as Competitive Moat

The Mitsui relationship is the quiet superpower in this story. Sponsor quality shows up as asset pipeline, operating expertise, and reputational gravity—advantages that don’t always fit neatly into a spreadsheet, but become decisive when conditions get ugly.

For REIT investors, that’s the lesson: sponsor evaluation deserves weight comparable to asset quality. Because in sponsor-backed structures, who stands behind the vehicle shapes what goes into it, how it’s run, and how it’s perceived when the market stops giving the benefit of the doubt.

Lesson 3: Conservative Financial Management Through Cycles

Across the global financial crisis, the 2011 earthquake, and COVID, the same pattern repeated: conservative financing didn’t maximize returns in calm periods, but it expanded the range of outcomes when stress hit.

Low leverage and long-term fixed-rate borrowing are not exciting choices. They’re insurance. Financial engineering tends to optimize for average conditions; conservatism optimizes for the scenarios that can end you. In REITs—where refinancing risk is existential—that trade-off is often the difference between surviving a downturn and becoming a consolidation story.

Lesson 4: Concentration Can Be a Feature, Not a Bug

NBF’s Tokyo office concentration looked like a gamble, especially in a country still traumatized by a property crash. But over time, it proved to be a source of strength: deeper market knowledge, sharper acquisition decisions, tighter tenant relationships, and more consistent operational execution than a scattered strategy would likely deliver.

The lesson isn’t “concentrate.” It’s “know why you’re concentrated.” For investors, the question is whether focus reflects informed conviction and capability—or whether it’s just unexamined concentration risk wearing a confident face.

Lesson 5: Policy as Tailwind

Abenomics and the BOJ’s entry into J-REIT purchases changed the game. It supported valuations, compressed yields, and shifted market psychology—often pushing prices beyond what fundamentals alone would justify.

That tailwind rewarded investors who understood the policy regime they were operating in. But it also contains the warning embedded in every policy-driven trade: support can fade. Policy can create returns, and policy can also remove them. If you’re investing in a market where the central bank is a meaningful buyer, macro literacy isn’t optional—it’s part of the job.

XIII. Epilogue: What the Future Holds

As Japan’s economy moved into 2026, Nippon Building Fund faced a landscape that looked nothing like the one it entered in 2001. The Bank of Japan had stopped making new J-REIT purchases, pulling away a buyer that had quietly shaped market psychology for more than a decade. Interest rates—still low by global standards—were no longer pinned at the floor. And the remote work question remained unresolved: hybrid work looked sticky, but no one could say with confidence what that meant for office demand over a full cycle.

Still, NBF met that uncertainty from a position most peers would envy. Its portfolio—more than ¥1.2 trillion of primarily Tokyo office real estate—sits in locations that can’t be replicated. The Mitsui relationship, now measured in decades, continued to matter in the ways that count: access to assets, operating capability, and a reputational anchor that steadies investor confidence when conditions get choppy. And the same conservative financial posture that helped NBF through 2008, 2011, and 2020 left it better prepared for a world where money has a price again.

In the public market, sentiment had been constructive. Nippon Building Fund units last closed at ¥134,600, up 9.61% over the prior 12 months. Over that same period, it outperformed the Nikkei 225 Index by 15.57%. For income-oriented investors, the trailing twelve-month dividend yield was 3.77%—not the headline-grabbing yield of distressed moments, but still meaningful in a country where “income” has often been synonymous with “scarce.”

Zoom out, and the bigger story is the one NBF helped create. The J-REIT market it pioneered matured into a major asset class, reaching roughly ¥14.6 trillion in market size as of March 2025, with 57 listed J-REITs. NBF remained the category’s benchmark: the largest, most liquid, and most institutionally held name—often the default reference point for “Japanese listed real estate” as an allocation.

The market itself showed signs of life again. The Tokyo Stock Exchange REIT Index rebounded in 2025, rising 16.22% as of the end of September. In August 2025, a new J-REIT listed for the first time in about four years—less a single event than a small signal that investors were willing to underwrite growth again after a long stretch of skepticism.

For long-term investors, what NBF ultimately offers is not a guarantee. It’s a set of advantages that have proved durable: heritage, sponsor backing, operating maturity, and capital discipline that doesn’t disappear when the cycle turns. The arc from those tense September 2001 listings to trillion-yen institutional scale is a reminder that in real estate—maybe more than anywhere else—patient execution compounds.

The question for the next quarter-century is whether those edges keep working in a new regime: shifting work patterns, demographic decline, and a central bank that’s stepping back rather than stepping in. The answer will hinge on adaptation—curating buildings that match evolving tenant expectations, maintaining occupancy through supply waves, and holding the line on financial prudence even when the temptation to reach for yield returns.

What’s clear is that Nippon Building Fund’s story has never really been just about one REIT. It’s a lens on Japan’s real estate rehabilitation: how a market traumatized by the world’s most infamous property bubble learned, slowly and imperfectly, to trust transparent, liquid, professionally managed real estate again. NBF didn’t just participate in that shift. It helped prove it was possible—and then became the institution built on top of it.

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music