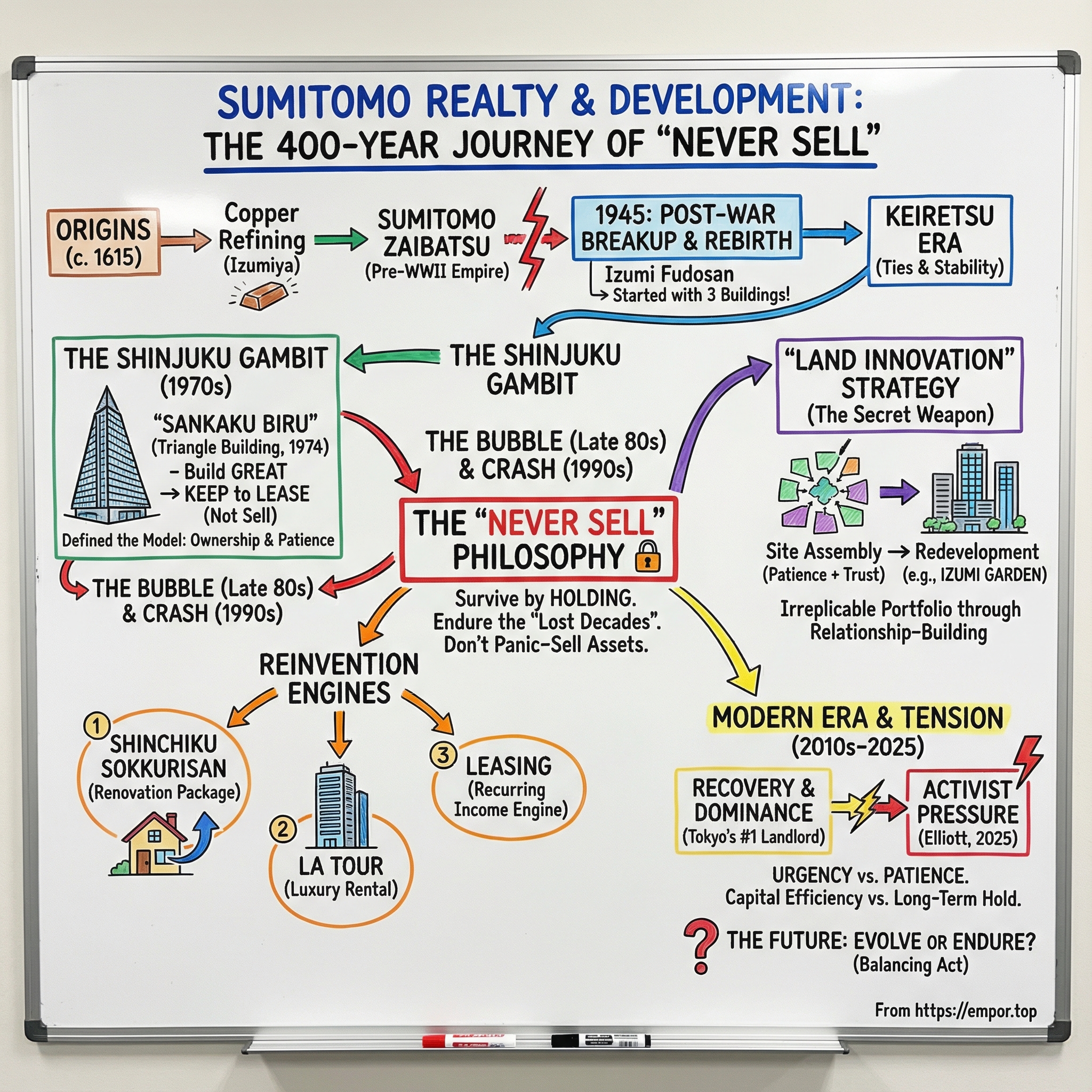

Sumitomo Realty & Development: The 400-Year-Old Developer That Never Sells

I. Introduction & Episode Roadmap

In the heart of Tokyo’s Shinjuku district, a 52-story triangular tower rises like a dare. Locals have called it “Sankaku Biru,” the Triangle Building, for nearly half a century. When it opened in 1974, it was briefly the tallest building in Tokyo, and its elevators were the fastest in the world.

But the detail that really matters isn’t the height, or the speed. It’s ownership.

Sumitomo Realty & Development built the Shinjuku Sumitomo Building — and it still owns it. No grand exit. No celebratory sale. Just a simple, stubborn idea that would go on to define the entire company: develop great buildings, then keep them.

“Historically, Sumitomo has followed a policy of never selling the properties that it develops.” In most real estate markets, that reads like a slogan. For Sumitomo, it’s the operating system. While other developers build to sell, Sumitomo builds to lease. While competitors optimize for the next deal, Sumitomo optimizes for the next generation.

The result is an empire built in plain sight. By 2018, Sumitomo Realty held Japan’s second-largest real estate portfolio, behind only Mitsubishi, valued at 5.7 trillion yen. It owned around 220 office buildings in Tokyo, with most concentrated in the city’s seven central wards. This wasn’t dominance by accident. It was dominance by accumulation.

Then, in March 2025, the story took a hard turn into the present. Elliott Investment Management built a stake in Sumitomo Realty & Development, and the company’s shares jumped to an all-time high. Suddenly, one of Japan’s most tradition-bound property owners was staring down one of America’s most relentless activist investors.

That’s the tension at the center of this story: a centuries-long philosophy of patience and control colliding with a market that’s increasingly demanding speed, returns, and change.

This is the tale of how a business with roots in the Sumitomo group’s 400-year lineage became a defining landlord of modern Tokyo; how it made it through the bursting of Japan’s bubble and the long stagnation that followed without selling off the buildings it owned; and why, today, outside pressure is building for it to reconsider the very strategy that made it what it is.

Along the way, we’ll hit the big themes: the shift from zaibatsu to keiretsu, the discipline and weird genius of “never sell,” the “Land Innovation” playbook that let Sumitomo assemble prime Tokyo sites one parcel at a time, and the activist awakening now reshaping Japanese corporate governance.

II. The Sumitomo Empire: 400 Years of Merchant Philosophy

To understand Sumitomo Realty, you first have to understand the organism it came from. The Sumitomo Group traces its origin to a small bookshop in Kyoto, founded around 1615 by Masatomo Sumitomo, a former Buddhist monk. A bookshop is an improbable starting point for one of Japan’s great industrial empires. But the next chapter wasn’t about books. It was about metals.

Copper refining is what made Sumitomo. Masatomo’s brother-in-law, Riemon Soga, learned Western methods of copper refining and, in 1590, established a smelting business called Izumiya — literally “spring shop.” His breakthrough was technical and commercial at the same time: he perfected a process that could extract silver from copper ore, something Japanese technology hadn’t previously achieved.

That move — pulling hidden value out of something everyone else treated as ordinary — became a kind of founding metaphor for the Sumitomo way: patience, craft, and an instinct for value that doesn’t show up on first glance. Soga’s eldest son, Tomomochi, who became Sumitomo’s son-in-law, built a copper refinery in Osaka that effectively merged the families’ operations and turned the business into a center of Japan’s copper industry. Then, in 1690–91, Sumitomo discovered and began working a massive copper deposit on Shikoku. The mine that followed would become the base layer of everything that came next.

That deposit was the Besshi Copper Mine, and it would operate for nearly three centuries — one of the longest-running industrial operations in the world. In the Edo era, copper mattered not just as a commodity but as an export that helped power the broader economy, and Sumitomo became a key supplier. From the start of the Meiji era, as Japan industrialized at speed, Sumitomo’s copper became even more strategic. As Japan’s only private mining company, it supplied a resource the country needed — and used that platform to widen into other businesses.

By the early twentieth century, that widening had a name: zaibatsu. Sumitomo had grown into one of the family-controlled industrial conglomerates that dominated Japan’s pre-war economy. In 1921, a family-controlled holding company, Sumitomo, Ltd. (Sumitomo Gōshi Kaisha), was set up to coordinate the growing combine. By the 1930s, Sumitomo was one of the largest zaibatsu in the country, and by the end of World War II it controlled roughly 135 companies.

Sumitomo was one of the “Big Four” zaibatsu — alongside Mitsui, Mitsubishi, and Yasuda. Two, Sumitomo and Mitsui, traced their roots back to the Edo period; Mitsubishi and Yasuda were born in the Meiji Restoration era. Across Meiji through Shōwa, the government leaned on these groups for their financial muscle and execution ability — from tax collection to military procurement.

The zaibatsu model was, in its own way, a machine for long-term thinking. A holding company sat at the top. A bank provided financing. Industrial subsidiaries dominated specific sectors. Because capital and control were coordinated inside the group, the companies could share expertise, support each other through downturns, and take a longer view than public markets typically allow.

And real estate was never an afterthought in that system. Sumitomo Realty & Development’s operations date back to 1933, when the Sumitomo Goshi Company erected the Tokyo Sumitomo Building. Planted in Marunouchi, it wasn’t just a building; it was a statement — a physical anchor in the nation’s capital, built to signal presence, permanence, and staying power.

That staying power wasn’t only architectural. Even today, Sumitomo says it operates by “Founder's Precepts” written in the 17th century. To modern investors trained on quarterly guidance and the latest management vocabulary, that can sound quaint. But in Sumitomo’s case, those old ideas — about integrity, discipline, and continuity — became something more practical: a culture that could survive shocks that wiped out less patient competitors.

III. Birth from the Zaibatsu Ashes (1945–1970)

The American occupation of Japan after World War II didn’t just change policy. It rewired the country’s economy — and it put a target on the back of the zaibatsu, the industrial conglomerates that had dominated prewar Japan.

To the occupation administration, the zaibatsu weren’t merely big businesses. They were seen as part of the machinery that had supported the wartime state. Breaking them up became a centerpiece of rebuilding Japan into a more decentralized, market-driven system.

The dismantling was sweeping. After Japan’s surrender in 1945, the occupation moved to seize the controlling families’ assets, eliminate holding companies, and outlaw interlocking directorships. Shares owned by the parent companies were pushed into the open market, and the operating businesses were forced to stand alone.

For Sumitomo, it was an existential moment. The group took concrete steps in line with occupation policy, even notifying its companies that they could no longer use the Sumitomo trade name or trademark. In November 1945, the occupation administration ordered the breakup of the four biggest zaibatsu.

Out of that wreckage came the direct ancestor of today’s Sumitomo Realty & Development. In 1949, the company was founded as Izumi Real Estate Co., Ltd. after the dissolution of the Sumitomo conglomerate. In 1957, it adopted its current name. The choice of “Izumi” wasn’t random — it echoed Izumiya, the original “spring shop” copper refinery from 1590. If the Sumitomo name was off-limits, the heritage could still be carried in code.

Functionally, Izumi Fudosan picked up where the old organization had left off. Established in December 1949 in Tokyo as the successor to the real estate division of the former Sumitomo Honsha (the group’s holding company), its first job was straightforward: serve the Sumitomo ecosystem. It leased and administered office buildings used by Sumitomo group companies, continuing the prewar work of Sumitomo’s real estate division — just without the old structure above it.

But the scale was radically different. The company began with almost nothing. In 1949, after the breakup, it had only three buildings. Three. That was the starting line for what would eventually become one of Tokyo’s great landlord empires.

What it lacked in assets, it still had in capabilities: know-how, credibility, and relationships built over decades. And as the postwar cleanup continued, some of the old pieces came back into view. In 1963, the company merged with the holding company of the former Sumitomo zaibatsu during its liquidation — a step that brought it closer to the remnants of its prewar origins.

At the same time, Japan’s corporate world was quietly reorganizing itself. As occupation restrictions loosened through the 1950s, the former zaibatsu companies began to reassociate — but not as family-run empires with a single command center. The new form was keiretsu: independent companies linked by relationships, informal coordination among presidents, and a web of financial interdependence rather than a controlling holding company.

Japan came to have six major keiretsu — Mitsui, Mitsubishi, Sumitomo, Fuyo, Sanwa, and the Dai-Ichi Kangyō Bank Group — the so-called “Big Six.” For a real estate business trying to rebuild from three buildings, that kind of network mattered. It meant access to patient capital and, just as importantly, a base of stable tenants — the sort of stability public-market logic doesn’t always reward, but long-term landlords depend on.

By the 1960s, the company was no longer just a group caretaker. From the early part of the decade, Sumitomo moved into developing and selling condominium properties. And in 1970, Sumitomo Realty went public on the Tokyo and Osaka stock exchanges. The IPO marked a shift: this wasn’t simply an internal service arm anymore. It was becoming a standalone developer with outside shareholders — and the need to grow.

This early rebuilding era also set the pattern for what came next. Sumitomo wasn’t going to out-Marunouchi Mitsubishi Estate or out-scale Mitsui Fudosan. It would have to find its own path to prime land and great projects — a different way to assemble sites, build, and hold. That search would eventually become the company’s signature advantage.

IV. The Shinjuku Gambit & Global Expansion (1970s–1980s)

In the early 1970s, Sumitomo Realty made a bet that would define its identity for the next half-century. While other major developers stayed anchored in Tokyo’s traditional business districts like Marunouchi, Sumitomo leaned into a place still in the middle of becoming something new: Shinjuku, a district transforming from a patchwork of low-rise land uses into Tokyo’s next great “subcenter.”

The first flag it planted there was unforgettable. The Shinjuku Sumitomo Building, completed in 1974, was the company’s first true high-rise project and, for a time, its headquarters. In Nishi-Shinjuku, it rose 212 meters — Japan’s first building to break the 200-meter mark. Its form did as much branding as its height: a three-sided, triangular tower with a dramatic atrium running the full height of the building. The geometry made it instantly recognizable, even if the atrium gave up some rentable floor area. It was architecture as a statement: distinctive, modern, and confident.

Construction began in November 1971 and finished on March 6, 1974. For six months, from March to September, it was the tallest building in Japan and all of Asia — until the nearby Shinjuku Mitsui Building edged it out. But the point wasn’t the duration of the record. The point was that Sumitomo, a company that had been left with just three buildings after the war, was now building at the very top of the skyline.

Even the elevators were part of the message. At completion, they were the fastest in the world, running at 540 meters per minute. It wasn’t just engineering prowess. It was a developer announcing, in steel and speed, that it intended to matter.

Tokyo took to it. For nearly half a century, people have called it “Sankaku Biru,” the Triangle Building. Its silhouette became part of the city’s modern visual vocabulary, showing up in photos, films, and the mental map of Shinjuku itself.

As the skyline grew, so did Sumitomo’s business model. In the late 1970s, the company moved into real estate leasing and brokerage. Over time, commercial and residential leasing would become the core of its income — a natural fit for a developer increasingly designed around owning and operating what it built. In 1982, Sumitomo shifted its headquarters to the 30-story Shinjuku NS Building, another property it developed. It was a subtle but telling move: it wasn’t just building icons. It was building a portfolio.

This era also marked Sumitomo Realty’s first serious push overseas — and it came with the early hints of both opportunity and risk. During the 1970s, the company invested actively in real estate in California and Hawaii. In May 1972, it established La Solana Corporation (now Sumitomo Realty & Development CA., Inc.), giving it a foothold in the U.S. market. That same year, La Solana paid $3.6 million for 46 acres in Huntington, California. Over the next decade and a half, it developed and marketed housing across prime parts of Los Angeles County — single-family houses and townhouses in places like Huntington, West Covina, Anaheim, Palos Verdes, and Dana Point. By 1989, more than 1,100 homes had been completed.

Then came the splashier, late-1980s deals — the kind that looked smart at the top of the cycle and painful in the rearview mirror. In 1987, Sumitomo acquired the Tishman Building at 666 Fifth Avenue in New York City. In 1989, it bought the JW Marriott hotel in Century City, Los Angeles for $85 million. The Fifth Avenue building, bought at the peak of Japanese enthusiasm for U.S. trophy assets, would later be sold at a loss in 1998 — a lasting reminder that global prestige can be an expensive substitute for durable economics.

And even before the bubble years hit full stride, the financials were already flashing yellow. By 1977, sales had climbed past ¥45 billion, yet the company was still losing money — about ¥2 billion — as expansion outpaced profitability. Under Chairman Seigoro Seyama and President Taro Ando, management responded by shifting toward more affordable housing, trying to widen the customer base and steady the business.

But the real test was still ahead. The late-1980s bubble economy would push Japanese asset prices into territory that didn’t resemble history. When that bubble burst, it would decide which companies could endure — and which would be forced into retreat.

V. The Bubble, The Crash, and the "Never Sell" Philosophy

To understand why Sumitomo Realty’s “never sell” philosophy mattered, you have to start with how unreal Japan’s bubble economy became — and how brutal the hangover was.

From 1986 to 1991, Japan lived through an asset-price fever dream. Real estate and stocks didn’t just go up; they levitated. And for a while, the country convinced itself this was the new normal.

The comparisons from the period read like tall tales, but they were repeated with a straight face at the time. By 1990, Japan’s real estate market was valued at roughly four times the United States’, despite Japan being vastly smaller in land area and population. In 1988, headlines claimed Japan’s theoretical land value exceeded that of all land in the U.S. by a factor of four. One widely circulated claim held that a single central Tokyo ward, Chiyoda-ku, could buy all of Canada. In Ginza, land reportedly traded at around $250,000 per square meter.

Underneath those anecdotes was a simple engine: credit. Banks, swollen with deposits, lent aggressively. Rising land values became collateral for bigger loans, which funded more buying, which pushed prices even higher. Between 1985 and 1991, commercial land prices in Tokyo tripled. Residential prices nearly doubled. Corporations and developers borrowed against inflated appraisals to scoop up more assets, and the banking system grew increasingly exposed to the assumption that land would always bail everyone out.

Then, around 1990, it stopped working.

As borrowing costs rose and Tokyo land prices began to cool, the stock market cracked. The Nikkei fell hard through 1990 and kept sliding into the early 1990s. The broader unwind was worse. Japan’s equity and real estate bubbles began bursting in late 1989. Equity values dropped about 60% by August 1992. Land values kept bleeding for years, ultimately falling roughly 70% by 2001.

For real estate companies, this wasn’t a bad year. It was an existential math problem: your assets were suddenly worth a fraction of what you paid, but the debt you took on to buy them didn’t shrink. Developers faced a stark choice. Sell properties at distressed prices to meet obligations — or hold on and hope you could outlast the downturn.

Most sold. They didn’t have a choice. Banks wanted repayment. Markets wanted reassurance. And if you did sell, buyers typically wanted the best assets — the very properties you’d most want to keep.

Sumitomo Realty made a different choice. It held.

Sumitomo Realty made its full−scale entry into the office building leasing business in the latter half of the 1970s. Ever since, we have continued to develop excellent office buildings focusing on redevelopment projects in central Tokyo. We weathered the bursting of Japan's economic bubble in the 1990s and The Global Financial Crisis in the 2000s without selling off buildings we own and steadily increased the number of buildings. As a result, Sumitomo Realty has become the No.1 owner of office buildings in Tokyo with more than 230 building in the central Tokyo.

On paper, that looks almost irrational. Why cling to assets while their book value implodes? Why not take the hit, reset, and move on?

Because for Sumitomo, the real risk wasn’t temporary decline. The real risk was permanent loss. Central Tokyo land is finite, and truly prime buildings are even rarer. If you sell them in a panic, you don’t just crystallize a loss — you give up your seat at the table. The company’s bet was that Tokyo would recover eventually, and that the only unforgivable mistake would be letting go of assets that could not be bought back at any sane price.

The collapse also had consequences far beyond spreadsheets. In 1993, the Sumitomo group — particularly Sumitomo Bank — became a target in a wave of intimidation and violence. Over just a few months, there were incidents of shootings, blackmail, arson, and harassment. Molotov cocktails were thrown at the homes of senior executives, including the chairman of Sumitomo Real Estate and the chairman of Sumitomo Corp. The attacks were widely seen as part of the ugly process of Japan’s corporate world trying to unwind bad loans and sever relationships that had been tolerated during the boom.

The real estate industry was especially exposed. During the bubble, “jiageya” — specialists who pressured small landholders to sell so larger projects could be assembled — played a notorious role in development. Organized crime had ties into these practices, and as the bubble burst and money tightened, the incentives flipped from expansion to extraction. Disputes over distressed assets, bad debts, and who would eat the losses became combustible.

Against that backdrop, Sumitomo’s model offered an unusual kind of insulation. If you aren’t dumping buildings, you aren’t creating fire-sale opportunities. If your core business is collecting rent from properties you intend to keep, you can focus on survival rather than triage. You wait. You endure. You keep the portfolio intact.

The bursting of the bubble kicked off what became known as the Lost Decade — which then stretched into two, and then three, as Japan’s economy stagnated and land prices kept sliding. But when the dust finally began to settle, Sumitomo Realty was still standing with its best assets still in hand.

And that set up the next reinvention: if building new in a depressed market was hard, what else could a developer do to keep growing?

VI. The Reinvention: Shinchiku Sokkurisan & The Mid-1990s Pivot

With new development frozen by the post-bubble slump, Sumitomo Realty needed a new engine. Not another skyline-defining tower. Something that could grow even when land prices were falling and buyers were cautious.

The answer was hiding in plain sight: the homes people already lived in.

In the mid-1990s, Sumitomo began a home renovation and remodeling business called Shinchiku Sokkurisan. Launched in 1996 for detached houses, it wasn’t “a little refresh.” The concept was closer to rebuilding — except cheaper and faster. Sumitomo would keep the core structure, using the existing framework like pillars and other barebones elements, and then remake everything else around it.

The timing mattered. The business took off in the wake of the Great Hanshin-Awaji Earthquake. The 1995 Kobe quake killed more than 6,000 people and destroyed huge numbers of homes, putting seismic safety front and center across Japan. Homeowners wanted reinforcement. Many couldn’t afford to tear down and start over.

Shinchiku Sokkurisan was Sumitomo’s packaged answer: a full remodeling option positioned as an alternative to rebuilding, with fixed pricing, built-in seismic reinforcement, and a headline promise of coming in at roughly half to two-thirds of the cost of a rebuild.

That “package” idea was the real innovation. Japan’s renovation market had long been fragmented — lots of contractors, lots of variability, lots of uncertainty. Sumitomo turned it into a standardized product, and then scaled it nationwide step by step. Over time, it became the leading brand in the category, surpassing 130,000 cumulative contracts, and later reaching 150,000.

The model also fit the era. It generated construction revenue without requiring Sumitomo to buy land. It served a country with an aging housing stock and homeowners more inclined to improve what they had than to move. And it aligned with the company’s instinct for durability: extend the life of what’s already there, strengthen it, and keep it productive.

Alongside renovation, Sumitomo pushed further into high-end rentals with the La Tour series. With La Tour Shibakoen in Minato Ward, Tokyo, the company launched a luxury rental apartment brand aimed at affluent professionals and expatriates who wanted premium living without buying. For a company wired for recurring income, this was a natural complement: another stream of high-quality rent, another asset to operate for the long haul.

Around this same period, Sumitomo continued building out its real estate distribution business — brokerage and sales agency services — rounding out a model that could make money in multiple ways at once: rent from owned buildings, construction profits from renovation, fees from brokerage, and selective sales where it made sense.

By the early 2000s, even with Japan still mired in stagnation, Sumitomo Realty had quietly assembled something rare: a business designed not just to survive a down cycle, but to keep compounding through it. The “never sell” portfolio anchored the whole thing. Shinchiku Sokkurisan provided growth without land risk. La Tour added premium recurring revenue. Brokerage earned fees whether markets were booming or not.

And with that foundation in place, Sumitomo was ready to lean into the capability that would become its signature advantage: “Land Innovation.”

VII. The "Land Innovation" Strategy: Sumitomo's Secret Weapon

So what’s the unfair advantage for a developer that doesn’t have the most land, didn’t start with the biggest balance sheet, and refuses to play the game of flipping properties?

Sumitomo Realty’s answer is what it calls “Land Innovation.” It’s not a construction technique. It’s a way of acquiring development opportunities in the one place everyone wants to build and no one can easily break into: central Tokyo.

Remember the company’s starting point. After the postwar breakup, it began with just three buildings. And it didn’t fully enter the business of developing office buildings in central Tokyo until the 1970s. That meant it couldn’t rely on an easy playbook like rebuilding what it already owned, or winning prime sites through competitive bidding against bigger, better-established rivals. Instead, Sumitomo leaned into a slower, more durable method: integrate many small parcels into one large site through persistent, relationship-driven effort—then redevelop it at a scale no single landowner could achieve alone.

That’s the heart of Land Innovation: site assembly in a city where ownership is famously fragmented. In the densest parts of Tokyo, blocks can be a patchwork of tiny plots held by families, small businesses, and long-established owners who often have little interest in selling. Turning that patchwork into a buildable, financeable, modern development can take years of negotiation, endless coordination, and a developer with the credibility to keep everyone at the table.

Sumitomo got a powerful tailwind for this approach in 1969, when Japan enacted the Urban Renewal Act. The idea was to make better use of land in densely populated areas, not just by rebuilding individual structures, but by improving entire neighborhoods in an integrated way—reconfiguring parcels, adding public facilities like roads and parks, and enabling low-rise blocks to become high-rise districts.

The mechanism matters. Under this framework, landowners don’t have to be bought out. Instead, they contribute their land into the redevelopment and receive floor space in the new building commensurate with the value of what they owned before. The developer—here, Sumitomo—covers the project funding, including construction costs, and receives the remaining floor space created by the new, higher-density building.

In practice, this solves the core problem of central Tokyo development: holdouts and capital. Rather than paying massive sums upfront to buy every last plot, Sumitomo can structure a deal where existing owners become stakeholders in the new building. And because redevelopment often replaces three-story buildings with towers, the incremental floor area created by increased density is what funds the project and makes everyone whole.

On paper, it’s elegant. In real life, it’s grueling.

One redevelopment project illustrates the human side of the process: about 100 landowners held discussions with Minato Ward and the Tokyo Metropolitan Government to shape a community around the concept of “open community development,” alongside goals like improving disaster prevention by communalizing buildings. That’s not a typical developer timeline. That’s coalition-building.

Coordinating a hundred stakeholders—each with their own priorities, timelines, and fears—while also navigating approvals and then executing complex construction is a capability, not a transaction. It demands patience and institutional trust. And that’s exactly what makes it so hard to copy.

The Izumi Garden development is the cleanest example of Land Innovation working at full scale. Above Roppongi-itchome Station, Sumitomo completed two large mixed-use redevelopment zones that together form IZUMI GARDEN—an urban block of roughly six hectares with offices, residences, retail, and more.

Sumitomo Realty manages IZUMI GARDEN as a district made up of two redeveloped areas: Izumi Garden Tower and Sumitomo Fudosan Roppongi Grand Tower. Together they combine office towers, residences, retail, a hotel, event halls, and conference centers—exactly the kind of dense, diversified complex that throws off recurring income for decades.

The tradeoff is time. The Roppongi project took about 14 years from initial participation to completion. Most developers can’t—or won’t—run a project on that clock. But that timeline is the point: it’s long enough to align landowners, government, and the community, and to earn the right to build something transformative rather than incremental.

For Sumitomo, Land Innovation created a different kind of moat. First, it generated development opportunities you can’t win in an auction, because you can’t outbid someone for years of relationship-building and hard-won consensus. Second, it reduced the need for massive upfront land purchases by using the redevelopment framework to align incentives and fund projects at the construction stage. Third, it compounded reputational advantages—each successful project made the next negotiation easier.

In other words, the barrier isn’t money. It’s institutional capability: relationships, credibility, regulatory fluency, and the patience to stay in the room until everyone can say yes.

And with that weapon, Sumitomo could keep doing what its strategy required—accumulating prime Tokyo assets it had no intention of selling—until, eventually, the market turned and the long wait started to pay off.

VIII. The 2010s Renaissance: From Survival to Dominance

After two decades of grinding through the Lost Decades, Japan’s property market finally started to thaw in the 2010s. For Sumitomo Realty, that wasn’t just good news. It was the payoff for a strategy that had looked stubborn, even irrational, during the long slump.

By the mid-2020s, the recovery had become visible in the data that matters most in real estate: land prices. A government survey showed that Japan’s average nationwide land prices rose 2.7% as of January 1, 2025 — the fourth straight year of gains, and the fastest pace since 1991, before the post-bubble decline set in. The momentum wasn’t confined to Tokyo either; it was spreading out to regional areas as the broader economy stabilized.

For a company that had refused to sell through decades of stagnation, the message was simple: the “never sell” philosophy hadn’t just preserved the portfolio. It had kept Sumitomo positioned to benefit the moment the tide turned. Buildings developed or acquired in the 1970s and 1980s — assets that could have been dumped at painful losses in the 1990s — were appreciating again.

But what’s interesting is what Sumitomo did next. It didn’t treat the recovery as a victory lap. It treated it as a reason to reinvest.

The clearest example was its most iconic property. Sumitomo Realty carried out an extensive renovation of the Shinjuku Sumitomo Building — the triangular tower that helped define the company in the first place — over the period from September 2017 to June 2020. Then, on July 1, 2020, it opened a new public events space inside the building: “Sankaku Hiroba,” the triangular plaza.

Sankaku Hiroba is an all-weather atrium of about 3,250 square meters, created by placing a massive glass roof over an open space that had been part of the building’s original design. It wasn’t just a design upgrade. The space was intended to add liveliness to Shinjuku and, importantly, to serve a disaster preparedness role as an emergency shelter in the event of a large-scale disaster.

And the renovation embodied the company’s ethos in physical form. Rather than tearing down a landmark to chase a short-term redevelopment win, Sumitomo remodeled at a depth that made the interior feel as fresh as a new building while keeping the triangular exterior intact. By choosing renovation over demolition and reconstruction, the company reduced industrial waste and used resources more effectively. It also introduced energy-saving functions comparable to standards for new buildings, lowering environmental impact.

In other words: this is what it looks like when a developer thinks like a permanent owner. You don’t just build. You maintain, upgrade, and extend the life of the asset — because you plan to be the one collecting rent from it for decades.

Sumitomo wasn’t only polishing its legacy towers, either. It was still building at scale. In June 2020, it opened Ariake Garden, a large mixed-use complex developed on a 10.7-hectare site in the Ariake area along Tokyo Bay. Designed as an integrated district, Ariake Garden aimed to revitalize the area by making it more convenient for residents and visitors — and by giving the waterfront something it had lacked: a true everyday destination.

At its core is a major shopping mall, surrounded by a theater-style hall, a hotel, a spa, a dedicated theater for the Shiki Theatre Company, triple-tower condominiums with seismic isolation, and a plaza. It was a different expression of the same long-term instinct: build places people return to, not assets you flip.

By fiscal year 2019, the compounding was showing up in results. Sumitomo described itself as having expanded its platform by focusing on prime office buildings in central Tokyo, growing into Tokyo’s No. 1 office-building owner with 230 buildings. In the fiscal year ended March 2019, it posted record-high financial results, with revenue from operations exceeding 1 trillion yen and operating income and ordinary profit exceeding 200 billion yen.

The leasing business was the engine, and that theme continued into the mid-2020s. Sales rose from about ¥940 billion in FY2023 to over ¥1,014 billion by FY2025, with central Tokyo office rents and the La Tour luxury rental apartment series supporting growth.

Later in 2025, the company even revised its outlook upward. Based on recent business performance, Sumitomo Realty announced an upward revision to its FY2025 forecast, with net profit expected to increase significantly year-on-year by 18.3 billion yen, or 9.6%. Management pointed to what long-term owners love to hear: improving occupancy, tenants accepting rent increases in Tokyo office buildings, and higher rent per unit for La Tour.

And yet, just as the story started to read like vindication, a new tension entered the frame.

After decades of building value patiently — and often quietly — outside investors began asking a sharper question: was Sumitomo’s conservatism protecting the portfolio, or leaving value on the table? In a market newly obsessed with shareholder returns, that question was about to bring Sumitomo face-to-face with a very different kind of long-term strategy: activism.

IX. The Elliott Inflection Point: 2025 and the Activist Awakening

In March 2025, Sumitomo’s four-centuries-deep instinct for patience ran headlong into a very different philosophy: American activist urgency.

Elliott Investment Management had built a stake in Sumitomo Realty & Development. The market’s reaction was immediate. After the news broke, the stock jumped and closed at a record high, up 11% on the day. For a company that prides itself on quiet compounding, this was a loud moment.

Elliott’s arrival wasn’t happening in a vacuum. Japan had become one of the world’s most active battlegrounds for shareholder campaigns, helped along by a regulatory and cultural shift: the government and institutions wanted public companies to explain themselves better, use capital more efficiently, and take stock prices seriously. In March 2023, the Tokyo Stock Exchange put a formal marker down, urging listed firms to take action to implement management that’s conscious of cost of capital and stock price. The subtext was clear: if you’re sitting on assets and the market doesn’t believe you’re using them well, you’re inviting pressure.

As activists gained influence, a playbook started to spread across corporate Japan. Sell noncore assets. Raise dividends. Buy back shares. Unwind cross-shareholdings. Close the gap between what a company is worth on paper and what the market is willing to pay for it.

Sumitomo Realty was a tempting target because it was an outlier on exactly those points. Elliott argued that the company’s stock had persistently underperformed and traded at a valuation discount for structural reasons: a large portfolio of cross-shareholdings, a distinctive reluctance to sell property assets or manage REIT assets, and a board and governance structure that ranked near the bottom of the TOPIX 100 on several metrics. In Elliott’s view, these weren’t quirks. They were the reason the market didn’t reward Sumitomo’s portfolio the way it rewarded peers.

Elliott also painted a straightforward value story: if Sumitomo were valued more like other major developers, the implied upside could be dramatic. It pointed to peer-average PNAV multiples and argued that closing the gap could push the share price to just under ¥8,000 — more than 40% above where the stock was trading at the time.

Then came the asks. Elliott called for a shareholder payout of 50%, cross-shareholdings cut to less than 10% of net assets, and an ROE target of 10% or more. It highlighted that Sumitomo’s dividend payout had been 17% of net income in the previous fiscal year — roughly half the peer average — while larger competitors were moving faster, with one key peer expecting its payout to exceed 80% of net income that fiscal year.

The pressure point underneath all of this was uniquely Japanese: cross-shareholdings. These reciprocal stakes between companies have long reinforced relationships and stability — and, just as importantly, insulated management from outside influence. But regulators had grown increasingly critical. The Financial Services Agency and the Tokyo Stock Exchange, which oversee and update Japan’s Corporate Governance Code, had been pushing for strategic shareholdings to be justified and, increasingly, unwound.

Elliott didn’t just argue about the problem. It tried to change the shareholder base. The firm targeted companies that held small, long-standing cross-shareholding stakes in Sumitomo — often less than 5% — hoping to buy those blocks and, in doing so, loosen the protective web around management. Elliott itself already held more than 3% of Sumitomo.

As 2025 progressed, Elliott’s tone hardened. After one company announcement, Elliott said Sumitomo’s “Policy on Utilizing Fixed Assets and Leveraging Strategic Shareholdings” lacked ambition and urgency, and fell short on capital efficiency, shareholder returns, and reducing cross-shareholdings. It singled out the timelines: an asset-sale target of ¥200 billion that represented only a small slice of the leasing portfolio and might not be completed until the 2030s; and a 10-year plan to divest ¥400 billion of strategic shareholdings, which Elliott argued was simply too slow.

By October, Elliott escalated further. It approached several Japanese companies about buying their Sumitomo stakes, according to people familiar with the matter, and sent letters offering to purchase those holdings in block trades at around market price. The message was unmistakable: if the company wouldn’t move quickly, Elliott would try to reshape the ownership structure so that someone else would make it move.

Sumitomo responded — but cautiously. In December, it announced plans to buy back up to 35.0 billion yen of shares by the end of June, funded by the sale of listed shareholdings. It was a meaningful step in the direction Elliott wanted: shrinking strategic holdings and returning capital to shareholders.

Elliott said it wasn’t enough. Cross-shareholdings, it argued, were an immediate concern and a key reason for low shareholder approval at that year’s AGM. The firm urged Sumitomo to accelerate its plans, framing the prize in familiar activist terms: unlock capital, redeploy it into higher-return growth, and raise shareholder returns.

Then came the most symbolically charged development of all: property sales.

Sumitomo Realty & Development, facing pressure from Elliott, began seeking to sell a group of office properties in Tokyo for at least ¥100 billion. It earmarked 19 midsized office buildings for divestment, asked real estate investment firms and agencies to estimate their value, and also weighed the sale of eight rental apartment buildings in the city.

For most companies, that would be routine portfolio management. For Sumitomo, it touched the company’s core identity. A landlord built on the idea of holding forever was now, even if only at the margins, considering what it would mean to let go.

X. Porter's 5 Forces & Hamilton's 7 Powers Analysis

Porter's Five Forces

Threat of New Entrants: LOW

If you’re looking for the simplest explanation of why Sumitomo is so hard to attack, it’s this: you can’t just show up in central Tokyo and buy what Sumitomo already has.

After the postwar breakup, Sumitomo Realty started with just three buildings. It didn’t make a full-scale move into developing central Tokyo offices until the 1970s. So it couldn’t win by rebuilding an inherited land bank, and it couldn’t reliably win by outbidding bigger rivals. Instead, it built its position the hard way: redevelopment, one stubbornly negotiated parcel at a time, stitching small plots into sites big enough to matter.

That’s what makes “Land Innovation” a barrier, not a tactic. It takes years of trust-building with landowners, fluency with regulators, and credibility with local communities. Even a competitor with unlimited capital runs into a non-financial constraint: Sumitomo’s best buildings exist because of long, irreplicable historical processes. The 230-plus office buildings in central Tokyo aren’t a shopping list. They’re the accumulated output of decades, and many of the underlying sites are simply not available to a newcomer at any price.

Bargaining Power of Suppliers: LOW

Construction contractors and materials suppliers are numerous, and for a company of Sumitomo’s scale, that matters. Its volume and repeat business create leverage, and the presence of many competing suppliers limits any single one’s ability to dictate terms. Sumitomo’s in-house design and construction capabilities also reduce dependency and keep negotiating power on its side.

Bargaining Power of Buyers: MODERATE

In prime Tokyo offices, tenants don’t have endless good alternatives, which supports Sumitomo’s ability to raise rents. That’s been visible in business performance: occupancy has improved, and tenants have been accepting rent increases in Tokyo office buildings.

Still, the buyer side isn’t powerless. Large corporate tenants can negotiate, especially on major leases. And while work-from-home hasn’t hollowed out Tokyo the way some feared, it did introduce uncertainty around long-term office demand.

Meanwhile, the condominium sales business is more competitive. Buyers can choose among multiple developers, and differentiation is harder than it is in trophy-grade office locations.

Threat of Substitutes: LOW to MODERATE

For companies that need a central location, prestige, and access to talent, prime Tokyo office space doesn’t have many true substitutes. Remote work is the obvious long-term challenger, but its impact in Japan has been more limited, helped by return-to-office momentum and the gravity of dense urban business culture.

In residential, substitution shows up differently: renters can decide to buy, and buyers can decide to rent. Sumitomo is exposed to that tradeoff, but also partially hedged by participating in both ownership and rental markets.

Competitive Rivalry: MODERATE

Sumitomo competes with giants like Mitsubishi Estate and Mitsui Fudosan, but this is not an industry of constant price wars. Rivalry tends to be disciplined, even “gentlemanly,” in part because each major developer has distinct geographic strongholds—Mitsubishi in Marunouchi, for instance—which limits direct collision.

Where competition heats up is in condominiums, where products can look similar and brand advantage is harder to sustain.

Hamilton Helmer's 7 Powers

Counter-Positioning: Sumitomo’s defining move—build and hold, don’t flip—runs against what public markets typically demand. Competitors optimized around short-term return metrics can’t easily copy a patient, accumulation-first strategy without inviting their own shareholder backlash. Elliott’s campaign highlights the double edge here: the strategy differentiates Sumitomo, but it also creates a target.

Scale Economies: With 230-plus buildings, Sumitomo can run property management, tenant services, and maintenance with meaningful efficiencies. Scale also helps in condominiums through purchasing power and brand presence. That said, scale in real estate is powerful but not as extreme as in software or manufacturing.

Switching Costs: Office tenants face real friction in moving—termination penalties, relocation costs, and business disruption—especially under multi-year leases. But these are largely industry-standard switching costs, not a unique Sumitomo invention.

Network Effects: Traditional real estate doesn’t generate classic network effects. But Sumitomo’s concentration in central Tokyo creates something adjacent: a cluster effect, where tenants benefit from being near other prestigious addresses, transit, services, and business ecosystems.

Process Power: This is the heart of the moat. Land Innovation is process power: specialized redevelopment know-how, regulatory competence, and community engagement skills that can’t be bought off the shelf. Crucially, it’s institutional—embedded in how the organization operates—rather than dependent on a single star executive.

Branding: The Sumitomo name carries 400 years of accumulated trust. For landowners considering a redevelopment partnership, credibility matters as much as price. For tenants, a Sumitomo building signals permanence and reliability.

Cornered Resource: Prime central Tokyo land is finite. A large, high-quality portfolio there is not reproducible. Sumitomo’s control of a substantial slice of well-located office stock functions as a cornered resource: you can compete around it, but you can’t recreate it.

Competitive Comparison

Elliott’s core argument begins with one stubborn fact: Sumitomo trades at a discount to peers.

Sumitomo Realty’s market cap of about ¥1.6 trillion implies a price-to-book ratio around 0.7x, notably below Mitsubishi Estate (about 0.95x) and Mitsui Fudosan (about 1.05x). The market is effectively saying, “We believe the assets exist, but we don’t believe they’ll be managed in a way that maximizes shareholder value.”

That gap isn’t necessarily a referendum on asset quality. Elliott argues it reflects governance and capital allocation: cross-shareholdings that are hard to justify economically, and a strategy that prioritizes long-term accumulation over near-term returns. In other words, the discount is as much about what Sumitomo does with its value as it is about what it owns.

Key KPIs for Investors

To track whether Sumitomo is compounding quietly as it always has—or bending meaningfully under activist pressure—three metrics matter most:

-

Tokyo office occupancy and rental reversion: With leasing at the center of the business, the key operational story is straightforward: can Sumitomo keep buildings full and push rents upward on renewals? Positive rental reversion is the clearest signal of pricing power and portfolio quality.

-

Cross-shareholding reduction progress: Elliott estimated cross-shareholdings at the equivalent of 26% of net assets. The pace of reduction is a direct indicator of governance change. A move toward under 10% of net assets by 2027 would represent meaningful traction.

-

Shareholder payout ratio: With payout around 17% versus peer averages above 50%, changes here will reveal whether management is shifting toward a more shareholder-return-driven posture—or sticking with the traditional, accumulation-first model.

XI. Bull Case, Bear Case, and Risk Factors

The Bull Case

The bull case for Sumitomo Realty is, at its core, a simple idea: it owns the kind of Tokyo real estate you can’t recreate, and it’s positioned to keep compounding cash flow from it.

Start with the assets. Sumitomo’s portfolio sits in central Tokyo, in a market where land is scarce, locations are sticky, and premium office space still commands demand. That demand showed up in late 2024: average mid-market asking rents across Tokyo’s 23 wards rose 6.4% year-on-year in the fourth quarter, while occupancy in rental properties in these central wards reached 97.2%. In landlord language, that’s the dream combination: buildings staying full, and tenants paying more to stay there.

Then there’s the company’s way of making new supply. Land Innovation doesn’t just help Sumitomo win projects; it helps it avoid the standard developer knife fight of paying up in competitive bids. Its redevelopment pipeline is the product of years of negotiations and coordination that competitors can’t fast-follow. Sumitomo has said it plans to invest 2 trillion yen over the next decade into redevelopment in central Tokyo. If it can execute, that’s a long runway of new, high-quality inventory feeding into a rental machine built for the long term.

The third pillar of the bull case is that, in 2025, Sumitomo stopped being allowed to compound quietly. Activist pressure may force the company to do what public markets have been begging Japanese firms to do for years: unwind cross-shareholdings faster, return more capital, and close the valuation gap with peers. Elliott’s thesis is essentially, “You already have the assets. Now run the balance sheet like you believe it.” If the market begins valuing Sumitomo closer to peer-average PNAV multiples, Elliott argues the upside could be substantial — implying a share price just under ¥8,000, more than 40% above the level at the time of its analysis.

Finally, the macro backdrop looks more like a recovery than a replay of the 1980s. Recent price increases have been attributed to real-world demand drivers — tourism growth, infrastructure investment, and institutional reforms — rather than runaway leverage. Japan’s land prices rose at their fastest pace in 34 years in 2024, and average nationwide land prices increased 2.7% for the fourth straight year. For a company built to hold through cycles, a steady tailwind beats a speculative boom every time.

The Bear Case

The bear case asks a harder question: what if the very traits that made Sumitomo resilient are now holding it back?

First, Japan’s demographics are not your friend. The population fell by about 550,000 in 2024 to 123.8 million, and the share of residents aged 65 or older is approaching 30%. That’s a long, slow squeeze on household formation and housing demand. Tokyo can outperform the national trend for a long time — it has, and it probably will — but a shrinking country is still a shrinking country.

Second, “never sell” can be a discipline, or it can be dogma. Holding assets indefinitely looks brilliant when values and rents rise. But it also reduces flexibility: some buildings may become less competitive, some neighborhoods may evolve, and sometimes the best move is to recycle capital into higher-return opportunities. Elliott’s critique is that Sumitomo’s stance is outlier behavior — and from a capital allocation perspective, it’s hard to argue the point.

Third, governance and cross-shareholdings aren’t just abstract complaints; they can produce real principal-agent issues. Sumitomo holds a large portfolio of cross-shareholdings, maintains an unusual policy of not selling property assets or managing REIT assets, and its board and governance structure rank near the bottom of TOPIX 100 companies on several metrics. The risk isn’t merely optics. It’s that management optimizes for institutional stability and relationship maintenance — the traditional Japanese corporate priority — instead of shareholder returns.

Fourth, interest rates are no longer a free tailwind. After decades of near-zero or negative rates, the Bank of Japan began gradual normalization. Ten-year fixed mortgage rates were reported around 2.2%, up from 1.5% in September 2024. If the BOJ raises policy rates again between October and February, banks are expected to lift their base rates. Higher rates can hit real estate from both sides: they increase financing costs and put pressure on property values.

Material Risks and Uncertainties

Regulatory and Legal Considerations: Tokyo Stock Exchange governance reforms are no longer gentle suggestions. The pressure to justify — and reduce — cross-shareholdings is rising, and companies that don’t respond risk reputational damage and potentially stronger future enforcement.

Accounting Judgments: Long-held real estate is notoriously hard to value cleanly. Under Japanese accounting standards, book values can diverge meaningfully from market reality in either direction. That gap creates uncertainty around what the portfolio is truly worth — and how quickly value can be realized if needed.

Geographic Concentration: Sumitomo’s strength is also a concentration risk. A severe earthquake, a Japan-specific economic shock, or any major disruption centered on Tokyo would land directly on the company’s core earnings engine.

Activist Campaign Outcomes: Elliott’s campaign introduces a new kind of uncertainty for a company built on stability. Whether this ends in compromise, escalation, a proxy fight, or gradual capitulation will shape capital allocation, dividend policy, and potentially leadership. And in the short run, that uncertainty itself can become a risk factor for shareholders.

XII. Conclusion: The 400-Year Question

Sumitomo Realty & Development has arrived at a moment that would have sounded impossible for most of its history. A company whose lineage runs back to a 17th-century copper refinery is now being challenged by 21st-century activist investors. The same philosophy that built the business — patient accumulation, build-and-hold, “never sell” — is being pushed to evolve into something closer to shareholder-first capital management.

That tension is real. Elliott’s critique lands because it’s aimed at the parts of Sumitomo that markets typically punish: cross-shareholdings that tie up capital, a dividend payout that looks modest against peers, and governance that doesn’t inspire confidence that value will be surfaced quickly. The discount in the share price is, in many ways, the market keeping score.

But the defense is also compelling, because it’s rooted in what actually worked. “Never sell” wasn’t branding — it was survival equipment during the bubble crash, when forced selling destroyed balance sheets and broke competitors. Land Innovation wasn’t a buzzword — it was the only way a postwar company that started with three buildings could assemble irreplaceable sites in central Tokyo. And the relationships embedded in cross-shareholdings have, at least historically, helped enable the kind of long, multi-stakeholder redevelopment that can’t be won by money alone.

So the real question isn’t whether Sumitomo should change. It’s whether it can change without breaking the machinery that made it great. Can it unwind the old protections and return more capital while preserving the capabilities — patience, credibility, and redevelopment craft — that compound value over decades? Or will reform dissolve the very characteristics that created the portfolio in the first place?

Elliott has said its approach is constructive engagement, not a hostile takeover campaign. Sumitomo has acknowledged meeting with Elliott and exchanging views. What happens next will come down to pace and sincerity: whether management responds with reforms that are meaningful enough to satisfy a market that’s no longer willing to wait quietly, or whether it falls back on the stability that once protected it — and now attracts pressure.

Back in Shinjuku, the Sankaku Biru still stands. Its silhouette is the same, but inside it has been renovated and modernized rather than torn down and rebuilt. That’s a fitting metaphor for the company itself: adapt where you must, keep what matters, and don’t give up the asset.

Whether that approach remains viable in an era of activism and governance reform may be the defining question for one of Japan’s largest real estate portfolios — and the one that will determine what the next chapter of this 400-year story looks like.

For anyone watching from the outside, the scorecard is straightforward. Track occupancy and rental growth for the health of the engine. Track cross-shareholding reductions and payout ratios for evidence of governance change. And watch the Elliott engagement for what it reveals about capital allocation, property sales, and the willingness to move faster than Sumitomo has ever needed to before.

The assets are exceptional. The history is rare. And the ending, for now, is unwritten.

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music