T&D Holdings: Japan's Insurance Survivor — A Story of Quiet Consolidation and Market Specialization

I. Introduction: The Quiet Giants of Japanese Life Insurance

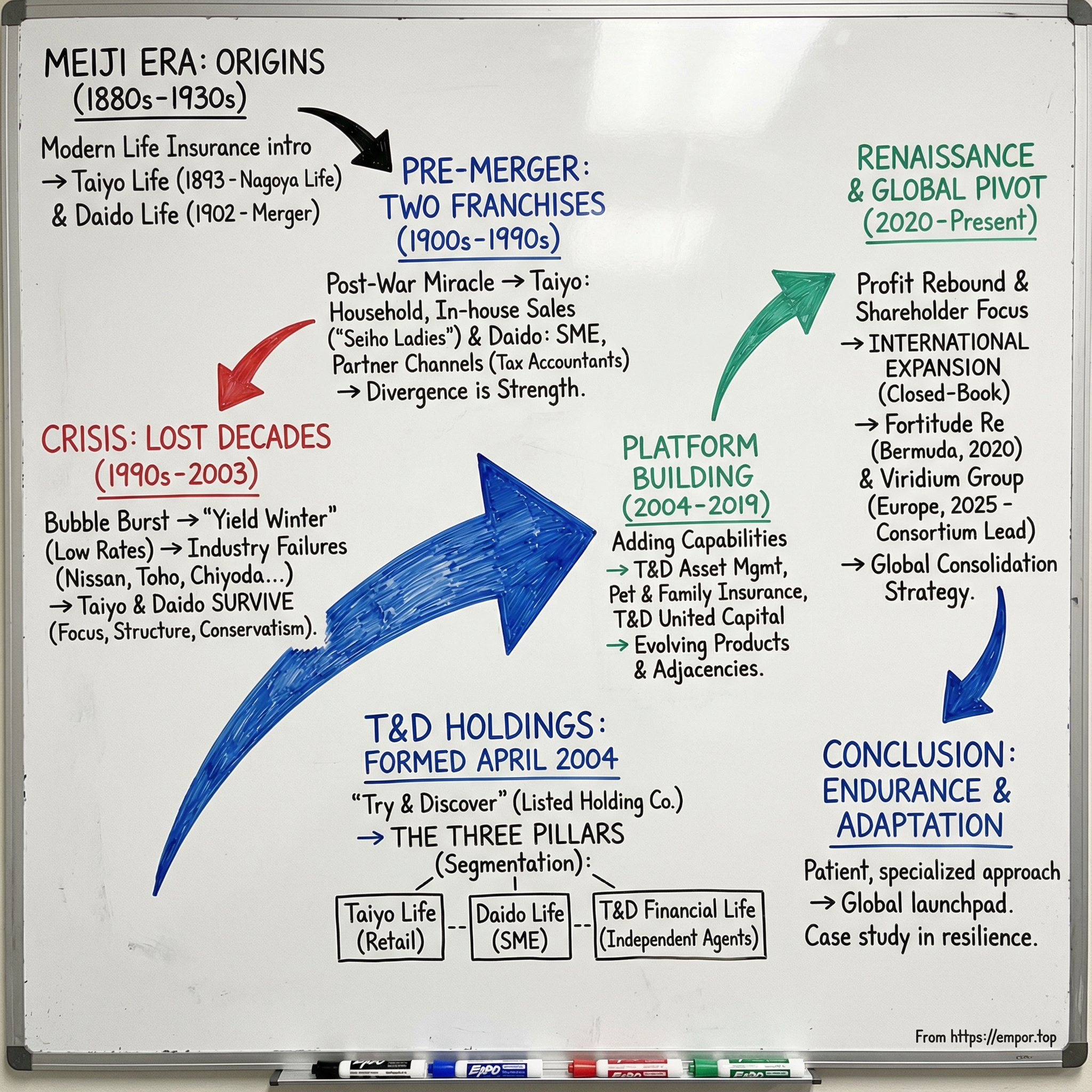

On a crisp April morning in 2004, something quietly historic happened in Japan’s financial world—something that would’ve sounded far-fetched just a decade earlier. Two of the country’s oldest life insurers, Taiyo Life and Daido Life, each with more than a century behind them, joined forces under a single umbrella. The vehicle wasn’t a full merger. It was a holding company—T&D Holdings—established in April 2004 as Japan’s first publicly listed life insurance holding company.

Even the name reads like a mission statement: T&D, short for “Try and Discover.” On the surface, the business looks familiar enough: individual and group life insurance, medical coverage, annuities. But the more interesting story is why this structure, and why then. These were two institutions that had made it through the kind of economic weather that wipes out incumbents—then used the aftermath to reposition for the next era.

Because the late 1990s and early 2000s were brutal for Japanese life insurers. The end of the bubble years, combined with deregulation, strained the whole industry. Bankruptcies—rare in insurance—started arriving anyway. Nissan Life failed in 1997. Toho Life followed in 1998. Then 2000 brought the collapse of three more big names: Chiyoda Life, Tokyo Life, and Kyoei Life. While household brands were crumbling, Taiyo and Daido held on—and more than that, they set themselves up to do something opportunistic and modern in a very Japanese way: consolidate, but without erasing what made each company work.

Today, T&D sits firmly in the top tier of Japan’s life insurance groups. As of March 2024, it had roughly 17.2 trillion yen in total assets. And by fiscal year 2023, it held about a 5.8% market share based on annualized in-force premiums.

So here’s the question that makes the whole story worth telling: How did two 120-plus-year-old Japanese insurers survive Japan’s Lost Decades, multiple competitor failures, and the longest low-interest-rate environment in modern financial history—and come out not just intact, but strategically sharper?

A big part of the answer is focus. T&D is not one monolithic insurer trying to be everything to everyone. It’s a group built around segmentation. Taiyo Life serves the household retail market. Daido Life specializes in small and medium-sized enterprises. And T&D Financial Life operates through over-the-counter channels like financial institutions and independent agents. Together, they cover a wide span of demand without forcing a single distribution model to do every job.

And then there’s the part that makes T&D especially interesting now: the shift from domestic survival to international ambition. In 2020, T&D made a major investment in Fortitude Re, a Bermuda-based insurance consolidator. It invested $1.2 billion through its initial stake and a follow-on capital raise in March 2022, and today holds a 26.4% stake in the business.

In March 2025, it went bigger. A consortium including Allianz, BlackRock, and T&D Holdings acquired Viridium Group, a leading European life insurance consolidation platform, from Cinven. The transaction was valued at approximately EUR 3.5 billion, with ownership split among the consortium and other financial investors—and T&D Holdings taking the largest share.

This, ultimately, is the story: how a patient, specialized approach to life insurance—refined over more than a century—became the launchpad for a global consolidation strategy. It’s a case study in endurance, adaptation, and the underappreciated power of knowing exactly who you’re built to serve.

II. The Meiji Era: When Japan Discovered Life Insurance (1880s-1930s)

To understand T&D Holdings, you have to go back to the moment Japan first learned what life insurance even was. This was the Meiji era: a country modernizing at full speed, sending bright young operators overseas to study Western institutions, then coming home to rebuild Japan’s economy with imported ideas.

Modern insurance arrived in the late 19th century. Tokio Marine, widely regarded as Japan’s first modern insurer, was founded in 1879. But that was marine insurance—ships, cargo, trade. Life insurance was different. It asked people to put a price on mortality, to plan financially for death, and to trust an institution to still be standing decades later. That wasn’t yet a native concept.

Enter Abe Taizo. He was one of the many Japanese businessmen sent to the West in the 1870s and 1880s at government expense, tasked with learning what made modern economies work. When he returned, he didn’t just bring back theories. In July 1881, he founded Japan’s first life insurance company and named it Meiji, after the emperor.

Abe’s biography reads like Japan’s own transition into modernity. Born in 1849—just four years before Commodore Matthew Perry forced Japan to open to the world—he started on a traditional path. His father was a physician and teacher, and Abe apprenticed in medicine at 12. He pivoted to Confucianism, then to Tokyo in the 1860s, where the Meiji Restoration was reshaping the country. There, he immersed himself in “Dutch learning,” Japan’s catch-all term for Western science and technology.

By 1881, Abe—who had studied under Yukichi Fukuzawa, one of the era’s most influential champions of Western modernization and the face on Japan’s 10,000-yen note—was ready to build. He established Meiji Life Insurance Limited Company alongside Heigoro Shoda and other early figures tied to what would become the Mitsubishi conglomerate.

Founding a life insurer in 1881 Japan wasn’t a simple matter of registering a company and hiring agents. Abe had to teach the public why life insurance mattered in the first place, and he did it while facing a government that, at the time, was largely indifferent to the concept. He served as president from the company’s founding until 1917, and through persistence, Meiji Life became firmly established within a decade—cementing Abe as the central pioneer of life insurance in Japan.

That’s the backdrop for the companies that would, much later, become T&D.

Taiyo Life’s roots go back to May 1893, when it was founded as Nagoya Life Insurance Co., Ltd. Then, in July 1902, Daido Life Insurance Company was created through the merger of three insurers: Asahi Life, Gokoku Life, and Hokkai Life.

The timing mattered. By 1902, Japan was industrializing rapidly and demand was growing—among households who wanted protection, and among business owners trying to build stability in a volatile new economy. And Daido’s origin story is worth underlining: it was born from consolidation. Three regional companies combined to compete in a market that was already getting crowded. A century later, that instinct—combine without losing purpose—would look less like coincidence and more like inheritance.

Structurally, many early Japanese life insurers were set up as mutual companies, owned by their policyholders. This model remained common in Japan and elsewhere for more than a century. One prominent example was Dai-ichi Mutual Life Insurance Company, founded in 1902 by Tsuneta Yano. Yano believed the mutual form could both return ample profits and protect an ideal: a customer-oriented business, not one designed primarily for outside shareholders.

That mutual structure shaped behavior. A mutual insurer isn’t answering to investors chasing near-term results; it’s accountable to policyholders who may be paying premiums for decades. That reality encourages conservatism, patience, and durability. When your owners are also your customers, “long term” isn’t a strategy—it’s built into the DNA.

Japan’s early 1900s were anything but smooth, economically. And yet life insurance held. By 1929, there were 40 private, non-government-operated life insurers, and they had issued 4.9 million policies. New life policies in Japan reached ¥1.2 billion a year by 1929, up from ¥278 million in 1914.

And the industry didn’t just grow through products. It grew through distribution—through something that would become distinctively Japanese: the door-to-door sales force, the “seiho ladies,” who built deep personal relationships with families. This wasn’t merely a channel; it was an infrastructure of trust. It created feedback loops, familiarity, and a sense that insurance wasn’t a transaction but a long-running relationship. Taiyo Life, in particular, would later become known for the strength and reach of its in-house sales force aimed squarely at households.

By the time the Meiji era’s innovations matured into a full industry, the key patterns were already visible. Japan’s life insurance market started fragmented, with many players competing for trust. Mutual ownership biased the system toward stability over flash. And distribution was built on relationships, not price-shopping. Those traits would quietly determine who survived the brutal decades to come—and set the stage for why Taiyo and Daido became such enduring franchises in the first place.

III. Building Two Distinct Franchises: The Pre-Merger Century (1900s-1990s)

Taiyo Life and Daido Life grew up in the same Japanese insurance ecosystem, but over the decades they evolved into almost opposite animals. And that divergence—slow, organic, unplanned—ended up being one of the smartest “strategies” they never formally wrote down.

Over nearly a century, each company found a customer, then built an entire operating system around serving that customer better than anyone else. Different products. Different distribution. Different relationships. By the time the industry started to shake, they weren’t competing head-to-head. They were defending two separate fortresses.

Taiyo Life became a household insurer in the most literal sense. Its strength was the retail market, especially older customers, and its offering covered the full arc of family needs: death protection, medical insurance, and nursing care coverage. If you were a Japanese family thinking about what could go wrong—and how to stay financially stable when it did—Taiyo wanted to be the default answer.

Its distribution model matched that ambition. Taiyo leaned on a dedicated, in-house sales force making household visits and building relationships over long stretches of time. These reps didn’t just drop in once to sell a policy and disappear. They came back. They learned the family’s situation. They adjusted coverage as life changed. The result was loyalty and stickiness: once a household became a Taiyo customer, it often stayed that way.

Daido Life built something just as durable, but aimed at a completely different center of gravity: Japan’s small and medium-sized enterprises. The country’s economy ran on millions of owner-operators—companies where the boundary between the business and the family is thin, and where a founder’s death or disability can threaten everything. Daido’s product set reflected that reality: term life, disability benefits, and other coverage designed to protect business owners and their employees against the kinds of risks that don’t show up in glossy corporate annual reports.

And Daido’s distribution strategy was the real differentiator. Instead of trying to reach every SME owner with a huge direct sales machine, Daido partnered with the people and institutions that already sat at the center of the SME universe: tax accountants, industry groups, and other tie-up organizations. Those relationships made the sales process feel less like cold outreach and more like a trusted introduction. When an accountant helped an owner think through financial risks, Daido was positioned to be the natural recommendation.

Over time, that turned into an ecosystem that benefited everyone involved—SMEs, tie-up groups, the tax accountants and CPAs acting as sales agents, and Daido itself. And because it was built on long-standing relationships, it was hard for competitors to copy quickly, no matter how much money they threw at it.

The backdrop for all of this was Japan’s post-war economic miracle. From the 1950s through the 1980s, Japan rebuilt into an industrial powerhouse. Living standards rose, incomes increased, and demand for financial protection grew right alongside the middle class. By the end of the 20th century, Japan ranked number one in the world in life insurance in force. It accounted for about a quarter of all insurance premiums collected globally, second only to the United States.

Even as growth slowed in the 1980s and 1990s, the industry kept swelling. Total life insurance policies in force in Japan rose to almost ¥2,100 trillion by 1994. There was simply an enormous amount of money—and promises—embedded in the system.

The 1980s, in particular, were euphoric. Japanese asset prices, from real estate to equities, seemed to rise without gravity. Life insurers earned strong returns on massive portfolios and used those returns to support generous guarantees. Many of the products sold in that era assumed the good times would last. They wouldn’t.

And here’s where Daido’s temperament starts to matter. After the bubble period, Daido moved quickly, faster than many peers, to tighten up its investment posture. It reduced risk assets and shifted its asset allocation away from domestic equities toward domestic bonds. For Daido’s core customers—SMEs whose livelihoods depended on the insurer being there when it counted—soundness wasn’t a slogan. It was the product.

This pre-merger history is what makes the later T&D structure so interesting. These were not two similar insurers waiting to be “rationalized” into one. Taiyo’s household-centric sales force couldn’t simply be redirected toward SMEs. Daido’s accountant-and-association network didn’t translate to retail families. The separation wasn’t inefficiency—it was real diversification, across customers, channels, and the risks each business naturally carried.

IV. The Crisis Years: Bubble Burst, Bankruptcies, and Industry Carnage (1990-2003)

On the last trading day of 1989, the Nikkei closed at 38,915.87. It was a number that felt like destiny at the time—and then, almost immediately, it became a monument. By the end of August 1992, the index had fallen to roughly 14,309. This wasn’t a normal bear market. It was the start of a long, grinding reset that rewired Japan’s economy and punished any financial institution built on the assumption that yesterday’s returns would last forever.

This era became known as the Lost Decade—Japan’s long stretch of stagnation after the bubble burst in 1990. And because the malaise didn’t stop with the 1990s, the label expanded too: the Lost 20 Years, the Lost 30 Years. The point wasn’t the branding. The point was duration. Japan didn’t bounce back; it settled into a new reality.

For life insurers, that new reality was existential.

Life insurance is a spread business. Insurers invest premiums and, over time, pay out benefits based on long-term promises. During the bubble years, many companies sold policies with generous implied returns—terms that made sense when interest rates were high and markets were booming. When the bubble popped and rates collapsed, the math turned vicious: insurers still owed policyholders the old guarantees, but could no longer earn anything close to them on safe assets.

Japan’s “yield winter” set in at the beginning of the 1990s and kept getting colder. Ten-year Japanese government bond yields slid from a peak of 8.3% in September 1990 to just 0.8% by September 1998. And they never truly recovered—staying below 2% for years, and hovering around zero in the late 2010s and early 2020s.

Put yourself in the shoes of a life insurer that wrote a policy in 1989 with an implied return of 5% or 6% for decades. When government bonds yield under 1%, where does the difference come from? Either you reach for risk—loading up on equities or credit at the worst possible time—or you accept a slow bleed, watching the negative spread compound year after year.

The broader recession made everything worse. Asset values fell. Stock prices stayed weak. Policyholders, under pressure, surrendered policies at higher rates. Insurers’ balance sheets deteriorated under a toxic mix of low rates, low markets, and rising withdrawals.

And then the failures began.

Bankruptcies in life insurance are supposed to be unthinkable—this is an industry that sells security itself. But Japan got them anyway. Nissan Life failed in 1997. Toho Life followed in 1998. Then came 2000, when three more major insurers collapsed: Chiyoda Life, Tokyo Life, and Kyoei Life. Some of the wreckage was bought by foreign firms like AIG and Prudential, which saw an opening to build a foothold in Japan amid the turmoil.

Nissan Mutual Life’s bankruptcy in April 1997 was the first post-war insurer failure in Japan, and it broke the psychological barrier. After that, the count kept climbing: since 1997, ten insurance companies in Japan declared bankruptcy. In a market with fewer than 100 insurers, that’s not a footnote—it’s an industry-wide trauma.

And it wasn’t happening in a stable rulebook. While balance sheets were cracking, the regulatory environment was being rewritten.

Japan launched its financial “Big Bang” reforms in the 1990s, pushing liberalization across financial services. In insurance, regulation shifted away from rigid controls toward greater flexibility and competition. The Insurance Business Act of 1995 captured the new spirit, and it helped usher in more foreign participation. By 1998, even fixed insurance rates were relaxed, letting companies compete more directly on price and service.

One consequence was a change in how insurance got sold. Independent agencies—shops and intermediaries not tied to a single carrier—grew in importance. In other words, distribution started to tilt away from purely captive channels and toward something more broker-like. Competition intensified. The market churned.

The headcount tells part of the story. In the 1970s, around 20 life insurers operated in Japan. By the end of the bubble economy, it was about 30. Through the 1990s, with foreign entrants arriving and weak players exiting, the industry went through a roller-coaster reshuffle. Today, more than 40 life insurers offer services in Japan.

So why did Taiyo Life and Daido Life survive when Nissan Life, Toho Life, Chiyoda Life, and others didn’t?

It wasn’t one magic trick. It was a stack of advantages—some chosen, some structural.

First, investment posture. Both firms were comparatively conservative, and Daido, in particular, moved quickly after the bubble to reduce risk assets and shift away from domestic equities toward domestic bonds. While some insurers were still sitting on equity portfolios purchased at bubble valuations, Daido was de-risking.

Second, focus. Their niche positioning wasn’t a marketing line—it was a stabilizer. Taiyo’s household customers tended to hold onto policies even in hard times; life coverage for a family isn’t an easy thing to cancel. Daido’s SME customers, meanwhile, needed protection precisely because the economy was unstable. When uncertainty rises, the risks to a business owner become more visible, not less.

Third, structure. Much of Japan’s life industry had mutual DNA, and that mattered in a crisis. Mutual-style governance reduced the pressure to swing for returns to satisfy equity investors. That made it easier to play defense, preserve solvency, and wait out the storm.

Fourth, scale—though not in the way people usually mean it. Taiyo and Daido weren’t the very largest players. That meant they didn’t carry the same degree of negative-spread baggage that the giants had accumulated during the boom. They were large enough to be credible and stable, but not so large that the mistakes of the bubble era became fatal.

By the early 2000s, conditions began to stabilize. The survivors modernized sales channels, adjusted products to the new rate environment, and started looking abroad as Japan’s domestic market matured and the demographic headwinds became impossible to ignore.

But the crisis years left permanent scars—and permanent lessons. Discipline during the good years matters more than brilliance during the bad ones. Specialization is not a limitation; it’s protection. And when an industry built on trust goes through visible failure, the winners are the ones that can prove—quietly, repeatedly, and over time—that they’ll still be standing when the promises come due.

V. The Strategic Alliance and Birth of T&D Holdings (1999-2004)

By the late 1990s, Japan’s life insurance industry had been through the fire—and the companies still standing could see what came next. Consolidation wasn’t a possibility; it was the direction of travel. The real question was how to consolidate without breaking what worked.

Taiyo Life and Daido Life chose partnership. But they did it in a way that was unusually deliberate, and unusually Japanese: not a full merger, but a structure designed to keep both companies’ strengths intact.

In January 1999, the two announced a broad business alliance. This wasn’t a rescue deal. Both were survivors in reasonable shape. It was a recognition that the next era would reward groups that could gain scale and resilience without turning their best businesses into one-size-fits-all mush.

Their timing also lined up with a global trend reshaping insurance: demutualization. Across the industry, mutual insurers were converting into stock companies, tapping public markets, raising capital through IPOs, and using that capital to buy and build. In the United States, Prudential, MetLife, and John Hancock all demutualized during this period. The playbook was clear: public equity gave insurers a war chest, an acquisition currency, and more flexibility to move fast.

Taiyo and Daido took the lesson—but not the template. Instead of merging into a single operating company, they built something that preserved the identity of each franchise: a holding company.

In April 2004, T&D Holdings, Inc. was established, and Taiyo Life, Daido Life, and T&D Financial Life became wholly-owned subsidiaries under it. It was the first publicly listed life insurance holding company in Japan, and it mattered because it offered a third way between “stay small and independent” and “merge and homogenize.”

Why a holding company, specifically? Because the leadership understood where the value was actually coming from.

Their business would be integrated among strong niche players with unique business models which allow each unit to maintain independent businesses. Such business models would enable the Group to grow steadily through business risk diversification. They decided to adopt the best option of establishing a holding company because integration through merger would reduce each company's unique strength.

A merger would have forced the standard ugly questions: whose culture wins, whose systems become the standard, whose distribution model gets prioritized, whose products get killed. Those integration battles can destroy the very capabilities that made the deal attractive. The holding company structure didn’t eliminate the need for coordination—but it avoided turning coordination into a zero-sum fight.

The second objective was to increase management maneuverability. The holding company would dedicate itself to group management while each life insurance company promotes sales. Such a management structure enables the Group to flexibly allocate its management resources to profitable and promising areas. In addition, the Group can make investments in M&A and new business areas aggressively, while keeping each company's independence and without risking existing businesses.

In other words: keep the operating companies focused on what they do best, while giving the group a brain and a balance sheet that could move capital where it mattered most. That separation—operators operating, the holding company allocating—was the real innovation.

Under T&D, the three main life insurance companies were Daido Life Insurance Company (est. 1902), Taiyo Life Insurance Company (est. 1893), and T&D Financial Life Insurance Company (formed in 2001 when Daido Life and Taiyo Life acquired Tokyo Life).

That third pillar is important, because it shows how the alliance was already evolving before the holding company even existed. In October 2001, Taiyo Life and Daido Life jointly completed the acquisition of the former Tokyo Life Insurance Company, and renamed it T&D Financial Life Insurance Company. Tokyo Life had struggled during the crisis years, and bringing it into the orbit gave the emerging group something neither Taiyo nor Daido had built organically: a channel built around independent insurance agents and financial institutions.

T&D Financial Life covered savings-type products (foreign-currency linked type, etc.) and protection-type products (income protection insurance, etc.) to the independent insurance agent market.

With that, the “three pillars” weren’t just a corporate slide—they were a real segmentation strategy with different customers, different products, and different distribution systems. Taiyo served households. Daido served SMEs. T&D Financial Life served the agency and financial-institution channel. When one segment softened, another could hold up the group.

The move into a listed holding company was also a significant financial transition. Shareholders of both Taiyo Life and Daido Life became shareholders of T&D Holdings. 55 shares of T&D Holdings were allotted in exchange for each share of Taiyo Life and 100 shares of T&D Holdings were allotted in exchange for each share of Daido Life.

And then there was the name—simple, but telling. In the belief that the T&D Insurance Group would be a going concern which will continue to "try and discover" something new in order to maximize the Group's corporate value, they named the "T&D Insurance Group" by taking the initial letters of "Try" and "Discover."

“Try and Discover” reads almost like a counterpunch to the Lost Decades: we’re not just here to survive; we’re here to keep moving.

In hindsight, the 2004 formation of T&D Holdings was the key inflection point in the entire story. It turned two strong but bounded insurers into a public platform—one that could access capital markets, pursue acquisitions, and place new bets without putting the core franchises at risk. The later moves—the platform buildout, the adjacent businesses, and eventually the overseas consolidation strategy—were all made possible by the structural choice they made right here.

VI. Building the Group: Strategic Additions and Platform Evolution (2004-2019)

Once the holding company was in place, T&D started doing what holding companies are designed to do: quietly build infrastructure around the operating insurers, add a few carefully chosen adjacencies, and make the whole machine more capable—without forcing Taiyo Life and Daido Life to become something they weren’t.

A lot of that work happened behind the scenes, starting with the unglamorous but essential stuff: managing money and managing operations. In July 2002, T&D Asset Management Co., Ltd. was launched through the merger of T&D Taiyo Daido Asset Management Co., Ltd. and Daido Life Investment Trust Management Co., Ltd., bringing investment management under one roof. A month later, in August 2002, the group did something similar on the operational side, launching T&D Taiyo Daido Lease Co., Ltd. through the merger of the group’s leasing businesses.

From there, T&D began widening its footprint—carefully.

In January 2007, T&D Holdings made Japan Family Insurance Planning, Ltd. a subsidiary. It was later renamed Pet & Family Small-amount Short-term Insurance Company. Then, in March 2007, T&D Holdings made T&D Asset Management Co., Ltd. a direct subsidiary, tightening up the group structure around a capability that mattered more and more in a low-rate world.

The pet insurance move can sound odd at first—why would a life insurance group care about cats and dogs? But it actually fit the reality Japan was heading into. The country’s declining birthrate and aging population meant fewer “classic” life insurance customers over time. Meanwhile, pet ownership was rising, and pet owners—often seniors or couples without children—were willing to spend real money on healthcare for animals that were, functionally, family. Pet insurance wasn’t a distraction; it was a demographic hedge.

In April 2019, that business took another step forward. Pet & Family Small-amount Short-term Insurance Company converted to a nonlife insurance company and was renamed Pet & Family Insurance Co., Ltd. It was a signal that this wasn’t an experiment anymore—it was a market the group intended to compete in for real.

That same year, T&D also laid important groundwork for what would later become a more international posture. In July 2019, T&D United Capital Co., Ltd. began operations. It was an investment subsidiary, and over time it would become a key vehicle for strategic investments outside the core domestic insurance operations.

While the group structure expanded, the core insurers kept evolving their products—because segmentation only works if you keep earning the right to win your segment.

Taiyo Life had a standout hit with Hoken Kumikyoku Best, a customizable product that let customers mix and match coverage modules based on their needs. By March 2017, it had attracted over 2.3 million subscribers. The product was a reminder that “traditional” didn’t have to mean static—Taiyo could innovate without abandoning its relationship-driven, in-house sales model.

Daido Life, true to form, used product strategy to stay tightly aligned with SMEs. In 2015, it introduced products aimed at SME owners and sole proprietors, including income protection and nursing care solutions. As business-owner demographics shifted—more aging founders, more succession anxiety—Daido adapted to the risks its customers were actually facing.

By this point, T&D’s “three pillars” weren’t just a concept. They were the organizing principle for the whole group: Taiyo Life centered on the household retail market, Daido Life on small and medium-sized enterprises, and T&D Financial Life on the independent insurance agent market, including financial institutions and insurance shop agents. The goal was straightforward: maximize the operating strength of each company by letting each one stay excellent at its own job.

Japan’s demographics shaped almost every decision in this era. The aging population and shrinking workforce were real headwinds, especially for traditional policies aimed at young families. But they also created clear pockets of demand: medical coverage, nursing care insurance, and annuity products. Over time, product development tilted more and more toward those needs.

By the end of this period, the organization chart had filled out. T&D Insurance Group was comprised of Taiyo Life, Daido Life, T&D Financial Life, T&D United Capital, T&D Asset Management, Pet & Family Insurance, All Right, and T&D Information System as direct subsidiaries. T&D Holdings had turned from a simple umbrella over two insurers into a broader platform—still centered on life insurance, but with real capabilities in non-life insurance (pet), asset management, and strategic investing.

And the way it got there is the point. This wasn’t an era of flashy, transformative deals. It was steady, disciplined platform-building—adding capabilities that reduced risk, expanded optionality, and prepared the group for the next chapter, when “surviving Japan” would no longer be the whole mission.

VII. Japan's Insurance Industry Renaissance and Recent Strategic Pivots (2020-Present)

After three decades in the yield wilderness, Japan’s life insurance industry started to look… healthy again. Profits had been stuck in the mud through the 1990s and 2000s, battered by wave after wave of macro shocks—the Asian crisis, the dotcom bust, the global financial crisis. But in the 2010s, the industry’s profit picture improved sharply, rising to levels that even edged past the go-go 1980s.

T&D hit a symbolic milestone right in the middle of this shift: its 20th anniversary in April 2024. Two decades as Japan’s first listed life insurance holding company didn’t just mark longevity—it marked proof that the structure worked.

The financial results in this period reflected that momentum. In fiscal year 2025, ordinary revenues reached ¥3,730.4 billion, up 16.3% year over year. Profit attributable to owners of the parent rose 28% to ¥126.4 billion in fiscal year 2024.

That strength was also visible in the nine months ending December 31, 2024. Ordinary revenues came in at ¥2,529.8 billion, up 7.1% from the prior year. Ordinary profit jumped 63.6% to ¥177.8 billion, supported by higher premium income and tighter execution. Profit attributable to owners of the parent increased 83.8% to ¥119.1 billion.

Importantly, this wasn’t just “earnings went up.” T&D was also signaling a more shareholder-focused posture. In May 2024, it announced a share repurchase plan of up to ¥100.0 billion, positioning it as a capital-efficiency move in a market that had long trained Japanese financial companies to prioritize stability over returns. Group adjusted profit also rose meaningfully in FY2024, increasing 36.7% year over year to ¥141.5 billion.

And then there’s the cleanest headline of all: T&D swung from a substantial net loss in FY2023 to strong net profitability in FY2024 and FY2025.

But the bigger story of this era isn’t just the rebound. It’s where T&D decided to point the machine next.

The most consequential strategic shift has been international expansion—specifically into the global “closed-book” or “legacy” life insurance business, where firms acquire portfolios of existing policies and then manage them efficiently for decades. It’s an unglamorous business. It’s also one where Japan’s insurers—trained by years of low rates, long-duration liabilities, and relentless discipline—can be unusually good.

The first major move was Fortitude Re. In November 2019, American International Group, Inc., The Carlyle Group, and T&D Holdings announced that a newly created Carlyle-managed fund, together with T&D, would acquire from AIG a 76.6% ownership interest in Fortitude Group Holdings, whose group companies operate as Fortitude Re, for approximately $1.8 billion. After closing, ownership interests in Fortitude Re would include Carlyle and its fund investors at 71.5%, T&D at 25%, and AIG at 3.5%.

T&D had already set up the vehicle for this kind of deal. In June 2019, it established its wholly owned investment subsidiary, T&D United Capital Co., Ltd. (TDUC), which acquired the 25% interest directly—explicitly to accelerate T&D’s strategic initiatives beyond its domestic core.

In June 2020, Carlyle and T&D announced they had completed the acquisition of the 76.6% interest in Fortitude Group Holdings from AIG, following regulatory approvals. At closing, AIG received approximately $2.2 billion in sale proceeds. Fortitude Re, in turn, was positioned as the reinsurer of roughly $30 billion of reserves from AIG’s Legacy Life and Retirement Run-Off Lines and approximately $4 billion of reserves from AIG’s Legacy General Insurance Run-Off Lines.

This deal mattered because it gave T&D a front-row seat in the legacy-life playbook: acquire long-duration blocks, run them with operational excellence, and treat the liability management itself as the core competency. That’s not far from what Japanese life insurers have been forced to master at home—just applied in a global arena.

Then came the bolder step: Viridium.

In March 2025, a consortium including Allianz, BlackRock, and T&D Holdings agreed to acquire ownership of Viridium Group, a leading European life insurance consolidation platform, from its private equity owner Cinven. The deal valued Viridium at about €3.5 billion, including debt.

As part of the transaction, TDUC planned to invest approximately JPY 120 billion. Upon closing, TDUC would acquire the largest stake among the consortium investors: a 29.9% ownership interest in Viridium, which would become an equity method affiliate of the group.

Viridium is Germany’s leading life insurance consolidator, with over 3.2 million contracts and about €68 billion in assets under management as of year-end 2024. With a market share of around five percent, it sits among the five largest life insurers in Germany—while also ranking as a top-two life consolidator in continental Europe and a top-ten life consolidator worldwide.

In August 2025, the consortium—Allianz, BlackRock, Generali Financial Holdings, Hannover Re, and T&D Holdings—announced it had completed the acquisition of Viridium from Cinven. The deal had been initially announced on March 19, 2025.

Strategically, Viridium put T&D deeper into the European version of the same theme as Fortitude Re: closed-book consolidation, scaled up, in a different geography. And the consortium structure mattered. Partnering with global leaders reduced execution risk and brought in complementary strengths—from asset management to reinsurance—while still giving T&D meaningful ownership and influence.

This wasn’t happening in a vacuum. Japanese insurers, facing a shrinking and aging domestic population and a saturated home market, have steadily expanded overseas—making acquisitions in the US and London markets, and investing across Southeast Asia and the BRIC countries. Industry observers like AM Best have highlighted the same logic: diversify earnings, find growth where Japan can’t provide it, and use overseas exposure—especially in developed markets—as a durable profit engine. Even as premium income in Japan has been supported since 2021 by sales of single-premium savings-type products, traditional life insurance demand has continued to soften.

Alongside acquisitions, reinsurance has become another tool in the kit. Fortitude Re and its backers, Carlyle and T&D Holdings, launched a new reinsurance sidecar vehicle designed to support business underwritten by Fortitude Re—another signal that T&D is leaning into modern liability management structures, not just buying assets abroad.

For investors, the takeaway is straightforward: this is a real strategic evolution. T&D is no longer just a Japanese life insurance holding company that happens to own three strong domestic franchises. It’s increasingly positioning itself as a global platform for life insurance and closed-book management—exporting the hard-earned discipline of Japan’s low-rate era into markets where that capability can be scaled.

VIII. The Business Model Deep Dive: How T&D Holdings Actually Works

To understand T&D Holdings, zoom out before you zoom in. This isn’t one insurer with one playbook. It’s a holding company built to run three distinct insurance businesses—each with its own customer, its own distribution engine, and its own way of winning—without forcing them into a single “standardized” operating model.

T&D Holdings, Inc. sits at the top as the insurance holding company for the T&D Insurance Group. Under it are three life insurance companies: Taiyo Life, Daido Life, and T&D Financial Life.

The job of the holding company is not to sell policies. Its job is to steer. T&D Holdings sets group management strategy and allocates management resources to enhance corporate value while managing profits and risks across the entire group. Meanwhile, each of the three life insurance subsidiaries focuses on maximizing operating revenue as an independent business unit.

That split is the point. Strategy and capital decisions are centralized; customer-facing execution stays decentralized. It means the group can shift resources, pursue M&A, and make strategic investments without disrupting the operating rhythm of the insurers that actually sit across the table from customers.

At the operating level, the segmentation is clean. Taiyo Life serves the household retail market. Daido Life focuses on small and medium-sized enterprises. And T&D Financial Life sells through over-the-counter channels like banks, securities firms, and independent agents. Three pillars, three distribution systems—built for breadth without forcing everyone to compete in the same lane.

Let’s look at each pillar.

Taiyo Life is the household franchise. It offers comprehensive coverage—death protection, medical insurance, and nursing care products—delivered primarily through an in-house sales force that conducts household visits. This is the traditional “seiho lady” approach, modernized, but still rooted in what it has always been rooted in: personal relationships and face-to-face advice.

That channel lines up well with where Japan’s demand has been heading. As the population ages, needs shift toward medical insurance, nursing care, and dementia-related coverage—areas where Taiyo has room to grow. Its products also reach beyond pure “family” positioning, addressing needs like asset formation alongside protection.

Daido Life is the SME specialist. It provides individual term life insurance and group insurance products to small and medium-sized enterprises, but the more important difference is how it gets to the customer. Daido doesn’t rely on the same kind of large in-house household sales machine. Instead, it leans on partnerships with organizations that already sit inside the SME owner’s world.

Tax accountants are the anchor partner. When business owners review finances and risk with their accountants, insurance naturally becomes part of the conversation—succession, disability, key-person risk, employee protection. Daido has worked to become the obvious answer in that moment, effectively embedding itself inside the SME ecosystem.

And it deepens those relationships by co-developing partner-specific products with each group, aiming to increase customer satisfaction and reinforce its competitive edge.

T&D Financial Life is the over-the-counter and independent agent channel. It sells through financial institutions and insurance shops—banks, securities firms, and independent agents—which have become increasingly important across Japan as distribution diversified beyond captive sales forces.

Its product mix spans both sides of the house: savings-type products (including foreign-currency linked types) and protection-type products (including income protection insurance), designed for how these channels prefer to sell and how their customers prefer to buy.

Beyond the three core life insurance companies, the group includes several supporting businesses. T&D Asset Management handles investment trust management and advisory and discretionary investment management. Pet & Family operates in non-life insurance. T&D United Capital conducts investments, manages portfolio companies, and handles related operations—and it’s the vehicle T&D has used for its overseas investments, including Fortitude Re and Viridium.

Step back and you can see the shape of the machine. The majority of revenue comes from Taiyo Life, the household business. But revenue isn’t the same thing as value, and across a holding company, what matters is how capital is allocated—toward the best risk-adjusted returns, not simply toward the biggest top line.

All of this sits on top of the reality that investment management is inseparable from life insurance. Insurers take premiums now and pay claims far in the future; what they earn on that float is a huge part of the economics. Japan’s long low-rate era forced every domestic life insurer to adapt, and T&D was no exception—expanding into foreign securities, managing currency risk, seeking yield in credit markets, and exploring alternative assets. The Fortitude Re partnership, backed by Carlyle, also connects T&D to a more global, institutionally sophisticated asset management toolkit.

Put it together and the business model becomes easier to read: three domestic franchises that diversify customers and distribution, a holding company designed to move capital where it earns the best return, and an international expansion strategy that extends the same long-duration, liability-management skillset into global closed-book opportunities.

IX. Competitive Analysis: Porter's Five Forces and Hamilton's Seven Powers

If you want to understand T&D’s position, you have to separate two things: what the Japanese life insurance industry structurally looks like, and what, specifically, T&D has that’s hard to copy. Porter's Five Forces tells you the first. Hamilton Helmer’s Seven Powers helps you spot the second.

Porter's Five Forces Analysis:

Threat of New Entrants: LOW-MODERATE

Japan’s life insurance market looks crowded on paper. In the 1970s there were around 20 life insurers. By the end of the bubble economy that number was roughly 30. After the churn of the 1990s—foreign entrants coming in, weak incumbents going out—there are now more than 40 life insurers offering services in Japan.

But “lots of logos” doesn’t mean “easy to enter.”

The first barrier is capital and regulation. Life insurers have to hold large reserves against long-dated promises and maintain solvency ratios under the watch of Japan’s Financial Services Agency. Getting licensed is hard; staying compliant is harder.

The second barrier is the real one: distribution. In Japan, the channels that actually move life insurance—in-house sales forces, long-standing partnerships with tax accountants, and bancassurance relationships—take decades to build. A new entrant can show up with money and product, but without a trusted path to customers, it will struggle to acquire policies economically.

Insurtech and digital-first entrants do represent a real threat at the edges. But life insurance is still a trust business. When you’re buying a policy meant to be around in 20 or 30 years, “will this company still be here?” matters. Century-old brands have an advantage that isn’t easily replicated with a slick app.

Bargaining Power of Suppliers: LOW

For a life insurer, the key “suppliers” are capital markets (where it invests premiums) and reinsurers (who help transfer risk). On both fronts, large incumbents generally have leverage.

Japan’s life industry has endured the long yield winter, and while there’s still room for improvement—especially through consolidation—the biggest players control enormous pools of assets. That scale tends to translate into negotiating power with asset managers, investment banks, and service providers.

Reinsurance, meanwhile, is a global market with multiple well-capitalized counterparties competing for business. That keeps pricing competitive and supplier power limited, particularly for large insurers that can bring steady volumes.

Bargaining Power of Buyers: MODERATE

Most individual policyholders can shop among products, but they can’t negotiate pricing one-on-one. Corporate buyers have more leverage, especially in group policies—so Daido’s SME customer base naturally carries somewhat higher buyer power than Taiyo’s household base.

The bigger shift has been in distribution. As deregulation progressed, independent agencies—insurance shops and intermediaries that can place business across multiple carriers—became more important. That adds a broker-like layer to the market and increases buyer power at the margin by making comparison easier.

Even so, switching costs in life insurance remain meaningful. Policies can have accumulated cash value, underwriting conditions may have changed since the policy was issued, and relationship-based sales models create inertia. People don’t switch life insurance the way they switch phone plans.

Threat of Substitutes: MODERATE-HIGH

Life insurance competes with a wide set of substitutes. Government social insurance provides baseline protection. Some households self-insure through savings. And other financial products—annuities, investment funds, structured savings—can cover pieces of the same territory.

Japan’s demographic reality makes this more complicated. With a shrinking and aging population, traditional death-protection demand has weakened over time: fewer young breadwinners, fewer “classic” family protection needs. Meanwhile, demand has shifted toward medical, nursing care, and annuity-type products.

Domestic constraints are a big reason Japanese insurers have leaned into overseas expansion and reinsurance transactions to support long-term growth. Premium income has remained elevated since 2021, driven largely by sales of single-premium savings-type products, but the underlying challenge remains: the core market is mature, and in some areas, shrinking.

Industry Rivalry: HIGH

Rivalry in Japanese life insurance is intense, and deregulation only sharpened it—more competition, more distribution channels, and a long phase of consolidation.

The competitive set includes major names like Nippon Life, Dai-ichi Life, Meiji Yasuda Life, Sony Life, and Japan Post Insurance. These companies have scale, brands, broad product portfolios, and increasing focus on digital transformation.

T&D competes in that arena, but it doesn’t try to win by being the most universal carrier. Its defensibility comes from where it’s chosen to be excellent: Taiyo Life in the household segment (particularly seniors) and Daido Life in SMEs. The holding company structure then adds a second layer of strength—shared capabilities in operations and investment management—without forcing the operating companies into the same mold.

Hamilton's Seven Powers Framework:

Porter tells you the weather. Seven Powers tells you whether T&D has shelter that lasts.

Scale Economies: Life insurance rewards scale in investment management, technology, compliance, and back-office operations. T&D’s combined balance sheet—roughly 17.2 trillion yen in total assets as of March 2024—gives it a meaningful cost and capability base that smaller players struggle to match.

Network Effects: Daido Life’s partnership model can behave like a soft network effect. The more tax accountants and SME organizations work with Daido, the more “default” Daido becomes in that ecosystem, which attracts more SME owners, which reinforces the partners’ willingness to keep placing business there. It’s not a pure network effect like social media—but it is self-reinforcing.

Counter-Positioning: The three-pillar structure is a form of counter-positioning against generalists. The biggest insurers compete broadly across segments. T&D, by contrast, has deep specialization in areas where focus matters—SMEs through Daido, households and seniors through Taiyo, and the agency/financial institution channel through T&D Financial Life. A generalist can try to match that depth, but it risks diluting economics and attention across too many fronts.

Switching Costs: Switching costs are baked into life insurance: policy features, cash values, new underwriting, and simple customer inertia. Relationship-based sales adds another layer. These costs help protect in-force books from being easily “stolen” by competitors.

Branding: In life insurance, brand isn’t marketing polish—it’s perceived solvency and reliability. Taiyo Life and Daido Life have spent more than a century building trust in their segments, and that trust matters when the product is a promise that may not be tested for decades.

Process Power: T&D has developed repeatable capabilities that are hard to replicate quickly—especially in Daido’s partnership-driven distribution process, and in the group’s growing exposure to closed-book management know-how through its Fortitude Re and Viridium investments.

Cornered Resource: Some of the most valuable assets here are relational. Daido’s ties with tax accountants and SME organizations, and Taiyo’s long-standing household customer relationships, represent relationship capital accumulated over decades. You can’t buy that off the shelf.

Key Performance Indicators for Investors:

For investors tracking whether this story is getting better or worse, a few metrics tend to matter more than headline revenue:

-

New Business Margin / Value of New Business: Are newly written policies attractive, or is the company “buying” growth with weaker economics? Persistent margin compression can be a warning sign of competitive pressure.

-

Embedded Value / European Embedded Value Growth: Embedded value aims to capture the present value of future profits from the existing book plus adjusted net asset value. It’s often a better lens than accounting earnings alone for long-duration insurers.

-

Policy Persistency Rates: Life insurance profitability depends on policies staying in force long enough to recoup acquisition costs. Strong persistency is a proxy for customer satisfaction and distribution quality.

And because T&D is a holding company by design, there’s one more thing investors should constantly watch: capital allocation. How much capital is going to each of the three domestic pillars versus international investments—and, crucially, whether it’s flowing toward the best risk-adjusted returns rather than simply reinforcing the biggest segment by tradition.

X. Investment Considerations: Bull Case, Bear Case, and What Could Go Wrong

T&D’s story can support more than one investment thesis. The same features that make it look like a steady, defensive compounder can also raise legitimate questions about growth, execution, and the risks that come with going global. Here’s how the case looks from both sides.

Bull Case:

Underappreciated Earnings Power: After living through one of the harshest interest-rate backdrops in modern financial history, T&D has come out with improving profitability. For the nine months ending December 2024, ordinary profit rose sharply and profit attributable to owners of the parent climbed even faster. If Japan truly moves away from ultra-low rates—as recent Bank of Japan policy shifts suggest could happen—T&D could see a real tailwind from higher investment income over time.

Demographic Tailwinds in Core Segments: Japan’s shrinking population is a headwind for “classic” life insurance, but it isn’t a headwind for everything. Taiyo Life’s senior-oriented household focus lines up with demand that is growing: medical insurance, nursing care coverage, and dementia-related products. Daido Life’s SME niche also ages well—succession planning, key-person insurance, and business continuity needs get more urgent as Japan’s owner-operator base gets older.

International Expansion Creating Value: Fortitude Re and Viridium give T&D exposure to a particular kind of global insurance opportunity: closed-book, long-duration life portfolio management. It’s not flashy, but it can be attractive for well-capitalized operators with strong actuarial and risk-management discipline. T&D United Capital’s planned 29.9% stake in Viridium is especially meaningful—large enough to matter, and positioned to compound if the platform continues to consolidate.

Shareholder-Friendly Capital Allocation: The share repurchase plan of up to ¥100.0 billion announced in May 2024 is a clear signal that T&D is thinking about capital efficiency and shareholder returns, not just stability for stability’s sake. In a sector—and a market—where that hasn’t always been the default, it’s a notable stance.

Defensive Characteristics: Life insurance tends to be a resilient business because much of the revenue base is recurring and the liabilities are long-duration. In downturns, many policyholders stick with existing policies because surrendering can be costly, which can help stabilize cash flows even when markets are shaky.

Bear Case:

Structural Decline in Addressable Market: The demographic math in Japan is unavoidable. Fewer young families means less demand for traditional death protection over time. Medical and nursing-care products can grow, but they may not fully replace the volume and economics of the legacy growth engine. And while premium income has been supported since 2021 by sales of single-premium savings-type products, the underlying trend—weakening demand for traditional life insurance—hasn’t disappeared.

Interest Rate Risks Cut Both Ways: Higher rates can improve reinvestment yields, but they can also produce short-term pain. Rapid rate moves can create mark-to-market losses on bond portfolios. Rising rates can also change customer behavior: newer policies may look more attractive, which can pressure persistency in older business that was priced in a different environment.

International Expansion Execution Risk: Fortitude Re and Viridium are large moves, and they’re far from home. Closed-book management rewards operational excellence, but cross-border investing adds layers of complexity: different regulatory regimes, different market practices, currency exposure, and the simple reality that you’re not the home-field player. Even with strong partners, execution risk is real.

Competitive Intensity: T&D isn’t the only Japanese insurer going overseas. Competitors are actively pursuing acquisitions abroad, which can push prices up and compress returns for everyone. When multiple well-capitalized buyers chase the same limited pool of quality assets, discipline gets tested.

Distribution Model Evolution: Taiyo Life’s relationship-driven, in-person sales model has been a historic strength—but consumer preferences evolve. Younger customers may prefer digital-first experiences, and recruiting and retaining high-quality sales representatives becomes harder as Japan’s working-age population shrinks. If the channel mix shifts faster than Taiyo adapts, growth could slow.

Regulatory and Accounting Considerations:

Japan’s Financial Services Agency (FSA) has been aligning domestic standards more closely with global frameworks such as Solvency II and the IAIS/ICS direction of travel. The intent is to move toward more risk-sensitive requirements that better reflect insurers’ real exposures rather than relying primarily on static capital buffers.

For investors, the practical implication is complexity—and potentially more volatility in reported results during transition periods. When accounting and solvency rules change, trend lines can look noisy, and comparisons across periods can become less clean.

Separately, the FSA has reportedly been surveying life insurers about potential risks tied to the growing use of reinsurance arrangements involving reinsurers backed by global investment firms, including questions about transaction scale, contract types, and exposure to Bermuda-based reinsurers.

That scrutiny matters. Even if T&D’s reinsurance approach is consistent with industry practice, increased regulatory attention can become an overhang. If rules tighten, the flexibility and economics of certain structures could change.

Myth vs. Reality:

Myth: Japanese life insurers are in terminal decline due to demographics.

Reality: Traditional death-protection demand is under pressure, but the mix is shifting toward medical, nursing care, and annuity products—real categories with real demand. And international expansion offers exposure to markets and opportunities that Japan’s demographics can’t provide.

Myth: The Lost Decades destroyed the Japanese life insurance industry.

Reality: The industry took real damage, but it also adapted. Profits more than doubled in the 2010s versus the prior two decades, even edging above the 1980s. The survivors came out more disciplined and more structurally resilient.

Myth: T&D Holdings is just a domestic Japanese insurer.

Reality: With a 26.4% stake in Fortitude Re and a 29.9% stake in Viridium, T&D now has meaningful international exposure—specifically in the global closed-book management ecosystem.

Key Monitoring Points:

Investors should watch for:

- Execution at Viridium, including how the business evolves under new ownership and whether additional closed-book acquisitions follow

- Trends in new business margins and policy persistency

- Capital allocation across domestic growth, shareholder returns, and international investments

- Bank of Japan interest-rate policy and the second-order effects on portfolio returns and policy behavior

- Competitive shifts in Japanese life insurance distribution, especially the balance between captive sales forces and independent channels

T&D’s story, at its core, is patient value creation: specialization, consolidation without destroying operating strengths, and disciplined capital allocation. Whether that becomes an attractive equity story from here depends on how well T&D executes overseas, how fast it adapts distribution to a changing customer base, and what Japan’s rate environment looks like in the years ahead. The company has proven it can endure. The open question is whether it can turn that endurance into sustained shareholder returns in its next chapter.

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music