Sony Financial Group: The Unlikely Insurance Empire

I. Introduction & Episode Roadmap

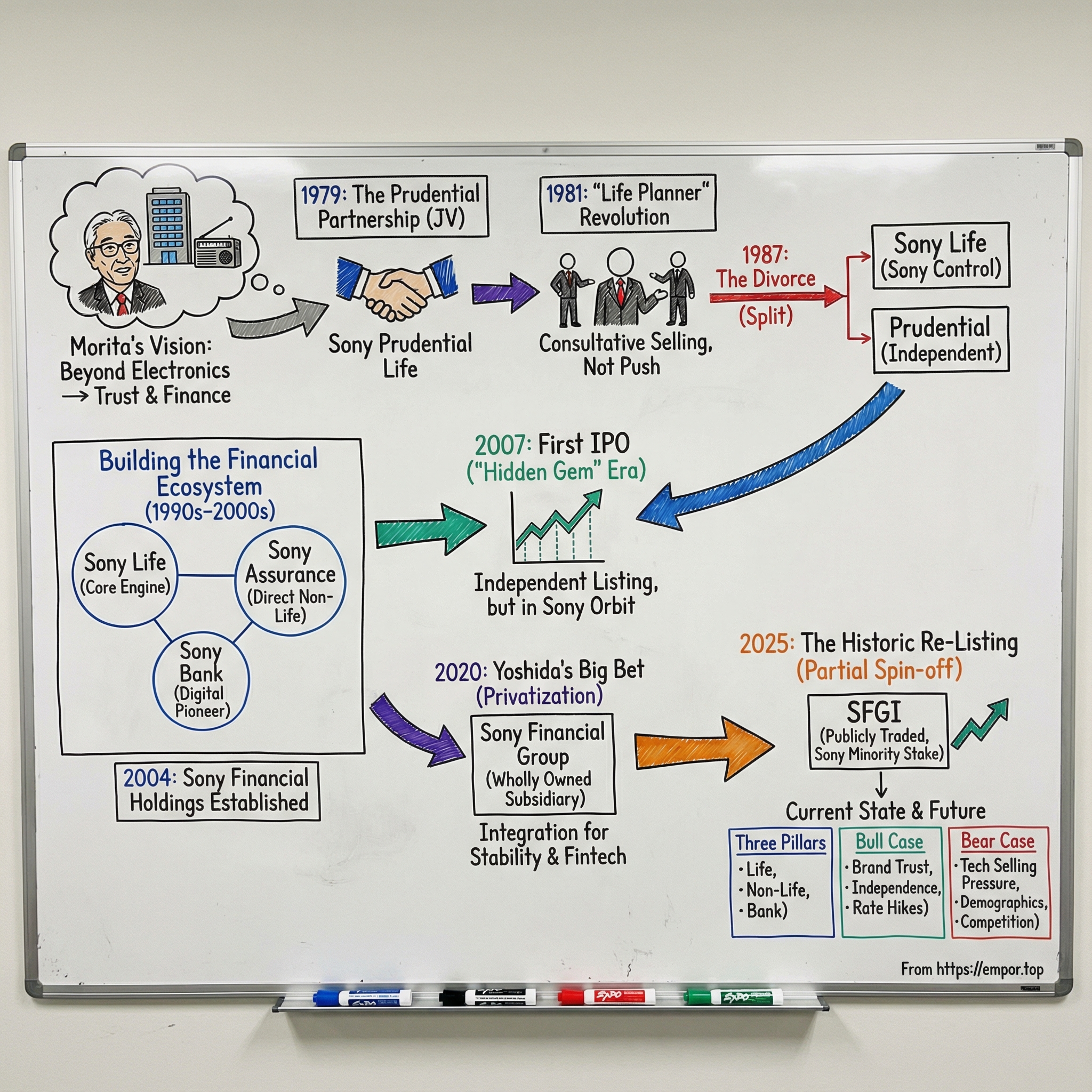

Picture this: September 29, 2025. The Tokyo Stock Exchange is humming, but not for the usual reasons. A major financial services company is about to “go public”… without an IPO. No roadshow. No bookbuilding. No underwriters setting a price the night before.

Instead, shareholders of Sony Group simply wake up and see something new in their brokerage accounts: shares of Sony Financial Group, allocated to them automatically—one share for every Sony share they already owned.

And the market had opinions. Sony Financial Group surged in its Tokyo debut, a rare test of whether Japanese companies can lift valuations by spinning out businesses. Shares opened at ¥205, traded as high as ¥210, and finished the day at ¥173.8—putting the newly listed company’s value at about ¥1.2 trillion (roughly $8.1 billion).

But the real intrigue isn’t the first-day pop. It’s the identity of the company itself.

How did the brand that gave the world the Walkman and PlayStation end up building one of Japan’s most respected life insurers?

The answer is a classic Sony mix of ambition and improvisation: a visionary co-founder who believed the Sony name could travel far beyond electronics, a chance meeting that cracked open a closed industry, a sales model that rewired how insurance was sold in Japan, and then—once the business was undeniably real—decades of corporate structure gymnastics: listing, delisting, and, ultimately, a return to the public markets in an entirely new way.

Sony Financial Group is one of the most improbable diversification stories in modern business. Under the Sony umbrella, it grew into a full financial-services platform: life insurance, non-life insurance, online banking, credit cards, and even nursing care facilities. Its economics are anchored by life insurance, which generates the vast majority of income, with smaller contributions from non-life insurance and banking.

This story matters well beyond Sony. It’s about how brand trust—earned in one category—can be redeployed in another. It’s about selling with advice and planning, not pressure. And it’s about a question that eventually corners every conglomerate: do you keep businesses together for “synergy,” or do you split them apart so the market can finally see what they’re worth?

Sony’s path—from IPO to privatization to a direct listing via spinoff—gives us a rare, real-world case study of both sides.

II. The Sony Context: Why Insurance?

To understand why an electronics company would ever wander into life insurance, you have to start with Akio Morita—the sake brewer’s heir who became one of the most influential business leaders of the twentieth century.

Morita was born in Nagoya into a family business that had made sake, miso, and soy sauce since 1665. He was the eldest of four, and his father, Kyuzaemon, trained him early to take over—so early that Akio was attending board meetings from around age six.

But even then, his attention kept drifting. In the family parlor sat an American phonograph, and Morita found it far more compelling than the centuries-old routines of fermentation and distribution that had built the family fortune. The future he wanted wasn’t in preserving tradition. It was in understanding technology.

He leaned into math and physics, graduating from Osaka Imperial University with a degree in physics in 1944. Then came the war. Morita was commissioned as a sub-lieutenant in the Imperial Japanese Navy, and during his service he met an engineer named Masaru Ibuka. They connected through a study group working on infrared-guided bomb development under the Navy’s wartime research efforts—a grim setting, but a formative one. It introduced Morita to his future partner.

That partnership became one of the great pairings in business: Ibuka as the engineer’s engineer, obsessed with solving technical problems; Morita as the builder, fluent in markets, messaging, and what consumers would actually trust. In 1946, they founded Tokyo Tsushin Kogyo—Sony’s predecessor—in the bombed-out shell of a department store, with about $500 in capital from Morita’s father. It was a tiny, precarious start that would eventually become a global brand.

And crucially, Morita never saw Sony as “just electronics.”

There’s a story from the 1950s, during one of Morita’s trips to the United States to promote Sony’s transistor radio. Looking up at the Chicago skyline, he fixated on one building in particular: the Prudential Building. His reaction wasn’t architectural admiration. It was strategic curiosity. Why would a life insurance company need something so huge? Morita reportedly said, almost to himself, that one day Sony would establish its own bank or financial institution and build something like that.

It sounds like a daydream—until you look at what Sony did next.

By the second half of the 1970s, Sony was already pushing hard to diversify through joint ventures in fields that, on paper, had nothing to do with televisions or tape decks. Japan’s economy was growing steadily. Consumers had more money, more choices, and more appetite for brands that felt modern and global. Sony—already a symbol of quality and innovation—was in a position to stretch.

In 1979, that diversification push hit full stride. In August, Sony announced that an affiliate company would begin producing and marketing cosmetics. That same month, it set up a joint venture with a U.S. life insurance giant: The Prudential Insurance Co. The following month, Sony started importing and selling Wilson sports goods in Japan.

Cosmetics. Insurance. Tennis rackets. From the outside, it looked chaotic—like a company drunk on its own success.

But Morita was working from a different premise: that Sony’s most valuable asset wasn’t any single device. It was trust. For decades, Sony had trained consumers to associate its name with reliability, modern design, and strong service. Morita believed that kind of trust could travel—that the Sony brand could credibly stand behind something as intimate and consequential as a family’s financial future, not just a radio on a kitchen counter.

And if you were going to test that belief anywhere, Japan’s life insurance market in the 1970s was the place.

It was dominated by legacy mutual companies with rigid distribution and products that were hard to distinguish from one another. Sales tended to be standardized and transactional. The industry wasn’t built around advice; it was built around moving policies. For a founder who’d spent his career raising consumer expectations—making products that felt not only better, but smarter—the gap was obvious.

If Sony could change how Japan bought electronics, Morita believed it could change how Japan bought insurance too.

III. The Prudential Partnership: A Chance Meeting

Sony’s entry into life insurance didn’t begin with a grand strategic plan or a multi-year M&A hunt. It began, essentially, as a conversation that was over almost as soon as it started.

Don McNaughton—then Prudential’s chairman and CEO—and Akio Morita both served on IBM’s board. At one board meeting, the two men talked for about eleven minutes. By the end of it, they’d landed on a provocative idea: bring Prudential’s life insurance business to Japan, and do it as a joint venture with Sony.

An idea is cheap, though. Turning it into a regulated financial institution in Japan was anything but.

By the spring of 1975, Morita was still asking the same question he’d been carrying for years: was there any U.S. life insurer that actually wanted to do business in Japan? Then the opportunity materialized in the most human way possible. McNaughton stopped by Sony’s offices while traveling in Japan. The two were already close—on a first-name basis—and Prudential was also one of Sony’s largest foreign shareholders through its American Depositary Receipt holdings.

In the course of their chat, Morita made what sounded like an offhand offer. If Prudential ever wanted to start operations in Japan, Sony would gladly help—especially with local market knowledge. The meeting ended without fanfare. But as McNaughton walked out, he turned to one of the Sony staff escorting him and asked, point blank: was Morita serious?

He was.

Morita moved immediately, quietly assembling a feasibility effort at the highest level. Tamotsu Iba from International Project Planning and Kunitake Ando from corporate planning at Sony’s U.S. subsidiary were asked to study Japan’s life insurance market and what it would take for a new entrant to survive. Soon, Tetsuro Yotsumoto—previously head of Sony’s International Division—was tapped to lead the team. More members joined, and what began as a back-of-the-envelope idea started hardening into an actual company.

The team had two jobs, and both were hard. First: get approval from Japan’s Ministry of Finance to establish a new life insurance company. Second: build a management plan that could work inside Japan’s highly particular insurance market.

The regulatory problem was the big one. Japan’s insurance industry had long been a closed neighborhood—great for incumbents, not especially great for customers, and not designed to welcome newcomers. The way through was positioning. Sony wasn’t trying to waltz in as an electronics company playing banker. The proposal was framed as something the government could support: a joint venture that would bring foreign expertise into Japan.

That framing mattered. The Ministry of Finance granted permission precisely because Sony would enter through a partnership with a foreign insurer—Prudential. It wasn’t just a formality. It was an endorsement of the premise that Prudential’s approach to building an agency force could be imported, translated, and used to modernize how life insurance was sold in Japan.

With the green light secured, Sony Prudential Life Insurance Co., Ltd. was established in August 1979 as a joint venture between Sony and Prudential Financial. The venture launched with 3 billion yen of capital, four branch offices in the Tokyo area, and a staff of fifty-one. Morita became chairman. Tatsuaki Hirai, a former Ministry of Finance bureau chief, took the role of president.

And at the center of the partnership was the real asset: a sales philosophy.

Prudential had built its business around a highly trained, educated sales force selling needs-based protection—less “here’s a policy,” more “here’s what your family actually needs.” That distribution model, refined over decades in the United States, would prove to be the transferable technology in this joint venture. Sony brought the brand trust and local credibility. Prudential brought the operating system.

On paper, it was a perfect match: Sony’s name, Prudential’s playbook, and a market ready for something different.

But corporate marriages rarely stay perfect. Even as the joint venture began to find its footing, the pressures that would eventually pull the partners apart were already starting to build.

IV. The Life Planner Revolution: Disrupting Japanese Insurance

“From today, insurance will change. Life Planners will change it!” That was the line Sony Prudential Life Insurance used to announce its operational launch in April 1981. It was audacious. And it was also a statement of intent: this wasn’t going to be another life insurer trying to out-muscle incumbents with slightly different policies. Sony was trying to change how insurance got bought in the first place.

The centerpiece was a new kind of salesperson, operating under a mission that was equally direct: “Providing sensible insurance protecting customers’ economic stability by high-level consulting.” In practice, that meant moving away from the prevailing style of Japanese life insurance sales—standardized products sold through personal networks with limited focus on what a household actually needed—and toward something closer to financial planning.

Sony’s bet was simple but radical for the market: train full-time professionals who could diagnose a customer’s situation, then design coverage that fit. Not a single “one-size-fits-all” policy, but a set of choices tailored to the person sitting across the table. Sony framed it as meeting the changing needs of Japan’s aging society, but the disruption was broader than demographics. It was a shift from pushing a product to earning the right to give advice.

Even the name carried the strategy. Sony didn’t call them “agents” or “salespeople.” It called them “Life Planners”—a title meant to signal expertise, analysis, and a longer-term relationship. The terminology wasn’t marketing fluff; it was a deliberate attempt to reset expectations for what an insurance conversation was supposed to feel like.

To make that model work, Sony concluded it couldn’t run this force like a conventional corporate sales team. Life Planners were given substantial autonomy. They weren’t hemmed in by rigid rules about how to build a book of business or where to base themselves. Compensation was performance-linked, designed to reward the people who could actually deliver consultative selling at a high level. Sony wanted an entrepreneurial culture, because it believed the best planners would behave less like employees and more like owners.

The structure pushed that idea to an extreme. Life Planners were expected to run their work as if they were presidents of their own small companies—hiring and paying for secretaries and office staff out of their own earnings. The goal wasn’t just productivity. It was to create independent-minded professionals who would build durable customer relationships and take pride in the craft.

At launch, the channel was tiny: 27 Life Planners. But Sony treated those first hires like the foundation of the entire business. The criteria were strict—proven competence, willingness to work on a full commission basis, and recruitment from outside Sony. They came from different industries, but they shared two things: strong sales track records and a willingness to bet on building a new kind of life insurance system.

And they didn’t get to start right away. The regulatory journey was still dragging. In February 1981, the Ministry of Finance finally approved Sony Prudential Life Insurance’s business license. Morita was ecstatic and celebrated with the project team that had been living through the process for five years. He’d launched plenty of products and ventures in his career, but he later reflected that he’d never been through something so difficult and time-consuming just to get a small company off the ground.

When the doors finally opened, Sony made sure the market heard about it. On day one, the company ran a newspaper advertisement featuring that slogan—insurance will change; Life Planners will change it. The operating footprint was still modest: 3 billion yen of capital, four branch offices in the Tokyo area, and fifty-one employees. Morita was chairman. Tatsuaki Hirai, the former Ministry of Finance bureau chief, was president. Kiyofumi Sakaguchi served as vice president, and Kunitake Ando was a director.

What followed validated the whole thesis. The company’s early growth was driven by the Life Planners, and Sony believed their productivity far exceeded that of traditional insurance salespeople—enough that the economics of the company could scale around this one distribution system. The best performers were paid accordingly, reinforcing the idea that this was a profession with upside, not a side hustle.

The model would later become famous far beyond Sony. Prudential’s Japan operation went on to achieve world-class productivity, averaging 7.5 new accounts per agent per month versus a global norm of 2.5. The “transferable technology” of the joint venture—the agency system—had proven itself in Japan.

And Sony’s version grew into a franchise. Today there are more than 4,000 Life Planners serving Sony Life customers under the company slogan: “Walk along with our customers and contribute to the realization of their dreams throughout their lives.” From 27 pioneers to a nationwide professional force, Sony had built one of the most successful distribution expansions in Japanese financial services.

But the real reason it stuck wasn’t just the compensation plan or the autonomy. It fit the Sony promise. In electronics, the Sony name had come to mean quality and modernity. In insurance, the Life Planner made that same trust tangible—through professionalism, consultation, and a feeling that the company was trying to get it right, not just close a sale.

V. The 1987 Divorce: Sony Goes Solo

Success has a way of turning a partnership into a tug-of-war. By the mid-1980s, Sony Prudential Life wasn’t just “doing okay.” The model was working, the Life Planner engine was real, and the joint venture was suddenly worth fighting over.

In July 1987, Sony and Prudential agreed to end the joint venture.

It was a turning point, and it started with a blunt proposal from Prudential: it wanted to buy all of the shares of Sony-Pruco Life Insurance and operate in Japan as a wholly owned subsidiary. In other words, thank you for the launchpad—now we’ll take it from here.

What followed were intense negotiations between Akio Morita and Prudential. Prudential’s logic was straightforward. The agency model had proven it could win in Japan, and full ownership meant full upside. Sony, in that framing, had been the local partner that helped crack the door open.

Morita didn’t see it that way. To him, this business was no longer an experiment in diversification. It was the proof that the Sony name could stand for something as consequential as protecting a family’s future. The Life Planner network represented years of recruiting, training, and relationship-building. Walking away would mean giving up what he had once described as his “30-year dream”: a Sony financial institution that could one day stand alongside Sony’s iconic product lines.

In the end, the Ministry of Finance decided in Sony’s favor. Sony and the bank that had supported Sony Prudential since its founding took over 70% of the stock. Prudential kept 30%, but agreed not to interfere in operations. And in practical terms, control had shifted decisively to Sony.

The rebrand followed quickly. In September 1987, Sony Prudential Life became Sony Pruco Life Insurance Co., Ltd. The name was a bridge between eras—still nodding to Prudential, but reflecting the reality that Sony now held the steering wheel.

Prudential later sold its remaining shares to Sony and established its own wholly owned subsidiary in Japan, Prudential Life Insurance Company Ltd., offering a full range of individual life policies. The breakup didn’t end the idea either company had brought to Japan. It duplicated it. Both went on to build substantial insurance businesses—evidence of just how large the opportunity had been all along.

By April 1991, Sony completed the transition by renaming the company Sony Life Insurance Co., Ltd., removing the last traces of the partnership from the brand.

The strategic implication was enormous. Sony now owned the whole machine: a proven business model, a trained and expanding Life Planner force, and a decade of brand equity in a category where trust is everything. Sony had entered insurance with Prudential’s playbook, learned the craft, and when the corporate marriage ended, kept the Japanese franchise.

Morita’s dream survived the divorce intact—and from here on out, Sony would build its financial future on its own terms.

VI. Building the Financial Ecosystem: Sony Bank & Sony Insurance

With Sony Life now firmly in Sony’s hands, the next question was obvious: was this going to be a single great insurance company inside a tech conglomerate—or the foundation of something bigger?

Sony chose bigger. Over the next two decades, it methodically assembled a full financial-services stack: life insurance at the core, plus non-life insurance and a bank. Not as a random side quest, but as a deliberate ecosystem that could stand on its own.

The milestones came fast. Sony Life became a Sony subsidiary in 1996. Sony entered non-life insurance in 1998. And in 2001, it launched a bank.

That non-life push became Sony Assurance Inc., originally founded in 1998 as Sony Insurance Planning Co., Ltd., then renamed in September 1999. Its angle was straightforward and, for Japan at the time, quietly disruptive: focus heavily on automobile insurance, and sell it directly to consumers rather than through the traditional agent-heavy model. The pitch leaned on what Sony already had in abundance—brand recognition and consumer trust—and over time Sony Assurance built a leading position in direct non-life insurance, especially in auto.

Then came the boldest stretch of the Sony brand yet: Sony Bank.

Sony announced the new banking unit in March 2000. It began operations on June 11, 2001, with ¥37.5 billion in capital and roughly 80 employees. And it launched with a statement of intent: Sony Bank would be a “direct bank,” built around the internet, with no physical branches and no proprietary ATM network. In a country where banking had long meant marble lobbies, paper forms, and dense branch footprints, Sony was effectively saying: we’re going to do this like a modern consumer product.

Customers responded immediately. The bank opened 340 online accounts in its first hour—early proof that Japanese consumers were ready for digital banking if the brand felt trustworthy.

At launch, Sony Bank offered yen deposit accounts, investment trusts, card loans, and bank payments, with plans to add foreign currency deposits, credit cards, and housing loans by 2002. That expansion came quickly, and Sony Bank carved out a durable niche in two areas that suited a digitally native model: mortgages and foreign currency deposits.

But a branchless bank still has a very physical problem: cash. Sony solved it with partnership rather than infrastructure. At founding, Sony owned 80% of the bank. Sumitomo Mitsui Financial Group took a 16% stake and, crucially, allowed Sony Bank customers to use its network of about 7,600 ATMs. That single arrangement gave Sony Bank nationwide reach without the cost and complexity of building it.

Sony Bank kept pushing into new frontiers as the years went on. In 2019, it launched an English-language online banking service to serve Japan’s growing foreign resident population. In 2023, it began selling digital securities—something it had been preparing for since 2022. And in October 2025, Sony Bank applied for a U.S. banking license, with the aim of issuing dollar-pegged stablecoins.

By the early 2000s, Sony had built the pieces. The next step was to make them legible—to regulators, to employees, and eventually to investors.

That’s what the 2004 reorganization did. In March 2004, Sony received approval from Japan’s Financial Services Agency to establish the required holding company structures under both the Insurance Business Act and the Banking Act. The following month, Sony created Sony Financial Holdings through a corporate split, placing Sony Life, Sony’s non-life insurance business, and Sony Bank under one umbrella.

Part of the rationale was regulatory necessity—Japan’s rules demanded clear separation and the right holding-company framework. But the strategic logic mattered more. The holding company gave Sony’s financial businesses a shared identity and management structure, helped attract specialized financial-services talent, and set the group up for the next phase of the story: stepping out from under Sony’s shadow and into the public markets on its own terms.

VII. First IPO & The "Hidden Gem" Years (2007-2019)

When Sony Financial Holdings listed on the Tokyo Stock Exchange in 2007, it felt like a graduation ceremony.

It had taken almost thirty years to get there: Morita’s early instinct that finance could be a Sony business, the Prudential partnership that opened the regulatory door, the 1987 split that left Sony in control, and then the patient build-out into non-life insurance and banking. By 2007, this wasn’t a quirky diversification experiment anymore. It was a real institution—big enough, stable enough, and distinct enough to stand in front of public-market investors and say: judge us on our own merits.

Sony didn’t do it for the headlines. The listing was practical.

First, capital. As a listed subsidiary, Sony Financial could fund growth directly from the market instead of competing internally with everything else Sony wanted to invest in.

Second, governance. Financial services is its own universe—tight regulation, long-duration liabilities, risk management as a core competency. A more independent structure let the people running the business optimize for that reality, rather than for whatever the electronics and entertainment cycles demanded that year.

Third, talent. A public stock gave Sony Financial a clear, focused incentive currency: compensation tied to insurance and banking performance, not to the volatility of game consoles, TVs, or movie slates.

And the business kept compounding. By Sony Life’s 30th anniversary in 2011, total assets had exceeded ¥5 trillion—an unmistakable signal of scale, and of how many households were willing to trust the Sony name not just with devices, but with their long-term financial protection.

What’s striking is that even as it grew up, Sony Financial kept acting like a challenger. It kept refining the Life Planner experience, especially after the sale. In 2009, Sony Life launched the Co-Creation project, bringing Life Planners and customers together to improve post-contract service and make high-level support easier to deliver at scale.

Then came the next wave: digitizing the work itself. In October 2012, Sony Life rolled out the second phase of its digital transformation, upgrading its sales support system with 5,000 new electronic devices. The impact was simple and very Sony: less paper, less friction. Applications, bank transfer registrations, and health check-up reports moved to paperless workflows, with onscreen declarations and real-time processing that reduced administrative burden for both customers and Life Planners—and streamlined operations at headquarters.

But for all that progress, one issue never really went away. Sony Financial had become a kind of “hidden gem”: clearly valuable, consistently performing, and yet hard for the market to price cleanly.

Even with its own listing, it still lived in Sony’s orbit. And that raised an uncomfortable question—was Sony Financial being valued like a true, pure-play insurer and bank, or like a subsidiary whose fate would always be intertwined with a conglomerate?

That tension would set up the defining corporate moves of the 2020s. But before Sony would ultimately separate the businesses again, leadership first decided to do the opposite—pull Sony Financial back in.

VIII. The 2020 Privatization: Yoshida's Big Bet

The COVID-19 pandemic hit in early 2020, freezing markets and forcing boardrooms everywhere into triage mode. At Sony, CEO Kenichiro Yoshida looked at the chaos and saw something else too: a narrow window to make a move that would be much harder in calmer times.

Yoshida wasn’t a flashy outsider brought in to “shake things up.” He was Sony through and through—a finance-minded operator who had built his credibility by making tough calls when the company needed them most. Born in Kumamoto on October 20, 1959, he joined Sony after earning a B.A. in economics from the University of Tokyo in 1983. Over the years he rotated through roles in Japan and the U.S., and in 2000 he moved to Sony’s internet subsidiary So-net, which he later took public in 2005.

He returned to Sony’s core leadership team in 2013 as deputy CFO, became CFO the following year, and gained a reputation for imposing financial discipline after years in which consumer electronics losses had piled up. When Kazuo Hirai—who had led Sony’s broader recovery—stepped up to chairman, Yoshida became CEO in April 2018.

By then, his style was clear. He was willing to cut, sell, and restructure in order to get Sony back to a healthier foundation: shedding the Vaio PC business, spinning out the TV unit, and pulling Sony back from destructive market-share battles in smartphones. That history mattered in 2020, because what he proposed next was another big structural swing.

In May 2020, Sony announced it would take its publicly listed financial arm, Sony Financial Holdings, fully private through a tender offer worth about 400 billion yen (around $3.7 billion). Sony already owned about 65% of the company, and it offered to buy the rest—along with stock acquisition rights it didn’t already control—at ¥2,600 per share, roughly a 26% premium to the prior close.

The pitch was strategic, not sentimental. Under Hirai and then Yoshida, Sony had been repositioning away from low-margin consumer electronics and toward businesses with stronger moats and recurring economics—PlayStation, image sensors, and entertainment franchises. But those businesses also came with more volatility. Sony Financial, by contrast, was built to be steady. Bringing it back under full ownership would give Sony a stabilizing profit engine and more control over capital allocation inside the group.

There was also a forward-looking angle: fintech. Sony argued that full ownership would make it easier to combine Sony’s technology capabilities—like artificial intelligence—with Sony Financial’s customer relationships. Yoshida framed it as a governance and agility play too. “We will be able to carry out more flexible management,” he said in a livestreamed news conference.

The timing wasn’t subtle. Sony had warned that operating profit could fall by 30% or more that fiscal year due to the pandemic’s shock to production and consumption. Even Sony Financial was feeling it: its sales force couldn’t meet customers normally, and sales activity deteriorated as in-person pitching became difficult. Still, the logic held. If anything, the disruption underscored why Sony wanted the stability of financial services inside the group when everything else was uncertain.

Not everyone agreed with the direction. Activist investor Dan Loeb had previously pushed Sony to sell the finance operation outright. Yoshida took the opposite stance: the division, he said, was integral to enhancing Sony’s overall value.

By the end of 2020, Sony had completed the tender offer, delisted Sony Financial Holdings from the First Section of the Tokyo Stock Exchange, and turned it into a wholly owned subsidiary. In October 2021, the company was renamed Sony Financial Group Inc.—a small change in words that marked a big change in posture. The “hidden gem” was no longer a semi-independent public company. It was back inside Sony, and Yoshida was betting that integration—paired with Sony’s technology—would create more value than separation ever had.

IX. The 2025 Re-Listing: Japan's First Partial Spin-off

Five years after Sony took Sony Financial private, the corporate pendulum swung back.

By 2025, Sony’s entertainment engines—PlayStation, music, and movies—had grown to more than 60% of total sales. The center of gravity of the whole company had shifted. And with that came a management reality: if Sony wanted to run harder at games and content, it needed to stop trying to steer a regulated financial institution with a completely different rhythm, risk profile, and capital logic.

So Sony did something Japan’s market almost never sees.

On September 3, 2025, Sony’s board approved a partial spin-off, effective October 1. Sony Financial Group Inc. would return to the public markets, but not through an IPO. Instead, Sony would distribute the vast majority of SFGI shares to Sony Group shareholders and keep a minority stake—slightly under 20%. In accounting terms, SFGI would move from being a consolidated subsidiary to an equity-method affiliate.

The result was historic: Japan’s first direct listing in more than two decades, and the country’s first partial spinoff of this kind—an unusually clean test of whether carving out a business can lift valuation and sharpen focus.

The split itself was decisive. Sony distributed about 83.6% of SFGI shares to Sony Group shareholders and retained roughly 16.4%. Sony Financial Group listed on the Tokyo Stock Exchange Prime Market under code 8729.

The market had already seen the basic math. The exchange set a reference price of ¥150 per share, implying a market capitalization around ¥1 trillion (about $6.7 billion). Then trading started. Shares opened at ¥205 and climbed as high as ¥210 on the first day—an immediate signal that investors were eager to value the financial business on its own terms.

Sony also tried to manage the most obvious risk of a large, sudden distribution: too many shares hitting the market at once. To help stabilize supply and demand after the listing, SFGI put in place a share repurchase program with a total acquisition amount of 100 billion yen, running from September 29, 2025 to August 8, 2026.

The messaging from Sony was simple: separation, not abandonment. “We aim to produce win-win results for both companies,” Sony Group President Hiroki Totoki said. Sony would concentrate its leadership attention and investment firepower on entertainment and technology, while Sony Financial would gain the independence to set its own priorities.

Some investors saw a broader signal in the move. One market observer said, “I would love it if this spinoff was just the first step for Sony to transition from a conglomerate to many pure play publicly listed companies.” In that framing, Sony wasn’t just reorganizing itself—it was piloting a model other Japanese conglomerates might copy to unlock value.

Strategically, the benefits were clean on both sides. For Sony, it meant more resources for its growth pillars: entertainment (PlayStation, music, film), imaging and sensing, and creative technology. It also made Sony easier to understand: less sprawling conglomerate, more content-and-tech company.

For Sony Financial Group, independence came with both freedom and scrutiny. As a newly re-listed company, SFGI said it planned a more proactive shareholder return policy, targeting dividends of roughly 40–50% of adjusted net income, with the goal of steadily increasing dividends per share.

X. Business Model Deep Dive: Three Pillars

Now that Sony Financial is back out in the open, the obvious question is: what exactly did shareholders just receive? Strip away the corporate-structure drama and you’re left with a clean, three-part machine—life insurance, non-life insurance, and a bank—that Sony built to reinforce the same promise in three different ways: trust, simplicity, and a consumer-first experience.

Sony Life: The Core Engine

Sony Life is the center of gravity. It has delivered stable adjusted net income of around 90 billion yen, with adjusted ROE exceeding 8% under IFRS 17. New business value and annualized premiums have continued to rise, and the new business margin has reached almost 10%—a signal not just of growth, but of growth that’s actually worth having.

And the real asset isn’t a product. It’s the distribution system.

The Life Planner model remains Sony Life’s signature advantage: a large, professional sales force built around consultation rather than pressure. With more than 4,000 Life Planners working with customers, Sony Life sells the way it always said it would—through needs-based planning and long-term relationships. That approach supports stronger retention and policy persistency, which in turn feeds profitability in a business where staying power matters as much as new sales.

Over time, Sony Life has steadily expanded its presence by leaning into what it does best: a dedicated Life Planner network focused on family-oriented protection solutions.

Sony Assurance: Direct Non-Life Leadership

If Sony Life is the relationship business, Sony Assurance is the efficiency business.

Sony Assurance has consistently grown direct premiums written, powered by its strength in direct auto insurance. The economics work because the operating model is built for profitability: lower combined ratios than many competitors, helped by brand recognition and strong customer satisfaction.

That’s especially notable in Japan’s property and casualty market, which is heavily concentrated. Three firms—Tokio Marine, MS&AD, and Sompo—hold about 88% share, and only a handful of others, including Sony Assurance, have even reached 1%. Sony’s path into relevance has been focus: it didn’t try to out-branch the incumbents. It leaned into direct distribution and used the Sony name to earn consumer trust at scale.

Sony Bank: Digital Banking Pioneer

Sony Bank is the third leg, and it looks the most “Sony” in the modern sense: a digital-first bank that wins on convenience and customer experience.

It has produced consistent profit growth and high customer satisfaction, particularly in its core businesses of mortgage loans and foreign currency deposits. A robust customer base, low default rates, and disciplined asset management have been key to that performance.

On customer satisfaction, Sony Bank has also scored well in Japan’s online investment and banking rankings. In the 2025 Oricon customer satisfaction surveys, it ranked #1 in net banking for two consecutive years and #1 in home loans for three years.

Investment Strategy and Risk Management

Underneath all three pillars is the part most customers never see, but investors obsess over: how the balance sheet is managed.

SFG has maintained a conservative investment portfolio, centered on yen-denominated interest-bearing assets that match the nature of its liabilities. The company has emphasized asset-liability management, which had nearly eliminated the duration gap. More recent interest rate increases, though, have caused that gap to re-emerge—pushing SFG to refine its ALM approach further to reduce sensitivity to interest-rate volatility.

That risk is most acute at the life insurance unit, which holds significant positions in super-long Japanese government bonds. As rates rise, those holdings can pressure valuation—and because markets price what they fear, that dynamic can ripple into the stock price too.

XI. The Japanese Insurance Landscape & Competition

To understand where Sony Financial Group really sits, you have to zoom out to the arena it’s fighting in: Japan’s insurance market, the third largest in the world by premium volume.

This is not a “growth market” in the Silicon Valley sense. It’s a mature, highly penetrated market where nearly everyone already has something in place. Around 90% of Japanese households carry life insurance—far higher than the United States or the United Kingdom. And it’s crowded. Japan has 42 registered life insurance companies: 25 domestic players, 13 foreign insurers, and four subsidiaries of non-life companies.

The prize is still enormous. In 2024, Japan’s life insurance market generated about ¥40 trillion in gross written premiums, and forecasts call for growth of more than 4% annually through 2029. Not explosive, but meaningful—especially in an industry where scale and persistence matter more than hype.

The bigger story, though, is demographics. Japan is one of the fastest-aging societies in the world, pushed there by low fertility rates and some of the longest life expectancies on earth. By 2020, more than 28% of the population was already 65 or older, and projections suggest that rises to 34% by 2030. Put differently: the country is aging into the exact set of needs insurers are built to monetize—health, longevity, retirement, and long-term care.

That age shift also reshapes where money sits in the economy. A large share of household assets is concentrated among people 65 and older, which means insurers aren’t just selling protection; they’re competing to become the long-term financial partner for an older, wealthier customer base.

The competitive set reflects that scale. The life market includes giants like Nippon Life, MetLife, Japan Post, Aflac Life, and Sony Life—among others. In that world, distribution becomes destiny. The agency channel still dominates, accounting for more than half of sales, even as insurance shops steadily take share.

This is the landscape that makes Sony Life’s model so interesting. It’s still an agency-driven market, but Sony’s Life Planner system isn’t built around volume selling. It’s built around consultation. That doesn’t eliminate competition—but it does give Sony a clear point of differentiation in a market where many products look similar and the real battle is fought in how you sell, who you trust, and who stays in a customer’s life the longest.

And the industry has a balancing act it can’t avoid: serving a growing population of older policyholders who need retirement and care solutions, while also finding a message that resonates with younger generations who have very different financial pressures—and, often, less appetite for traditional insurance.

XII. Porter's Five Forces & Hamilton's 7 Powers Analysis

Porter's Five Forces Analysis

Threat of New Entrants: LOW-MEDIUM

Insurance is one of those businesses where you can’t just show up with a clever app and start taking share. In Japan, regulatory barriers are real: licensing, capital requirements, and heavy compliance expectations from the Financial Services Agency. And then there’s the harder barrier—trust. Sony itself needed decades to stretch its brand from electronics into something people would rely on for their family’s financial security.

Still, the threat isn’t zero. Insurtech and digital-first players can pick off simpler products—especially in categories like auto insurance—where distribution and price comparison matter more than deep advisory relationships.

Supplier Power: LOW

For a well-capitalized insurer, money is rarely the bottleneck. Capital markets offer many funding options, and reinsurance can be sourced globally from multiple providers. Technology vendors are also generally in competitive markets, which keeps pricing power in check.

The one “input” that actually matters here is people—specifically, the Life Planners. That’s where Sony’s years of building an employer brand and a professional career path start to look like a real advantage.

Buyer Power: MEDIUM

In life insurance, customers don’t usually negotiate like they’re buying a commodity. Products are complex, and switching can be painful—surrender charges, paperwork, and in many cases the risk of health re-underwriting. That dampens buyer power.

But in more standardized categories—especially auto—buyer power rises fast. Digital channels make pricing easy to compare, and that transparency can force insurers into tighter pricing and faster service expectations.

Threat of Substitutes: MEDIUM-HIGH

Japan’s government social insurance system provides a baseline layer of protection, which can reduce the urgency to buy certain private policies. And for savings-oriented insurance, substitutes are everywhere: investment products, bank deposits, and other vehicles that compete for the same household money.

Policy and tax changes can also flip the economics of certain use cases overnight. The 2019 “Valentine’s shock” tax changes were a reminder that corporate-owned life insurance, in particular, can lose demand quickly when tax advantages disappear.

Competitive Rivalry: HIGH

Competition is intense, especially in auto insurance, where many insurers fight for share and pricing pressure is constant. That dynamic encourages aggressive discounting and can squeeze margins.

Life insurance is less fragmented, but the rivalry is still fierce. Giants like Nippon Life, Dai-ichi Life, and Meiji Yasuda have enormous scale, deep distribution, and the resources to keep pushing new products and service upgrades.

Hamilton's 7 Powers Assessment

Scale Economies: MODERATE

Scale helps in insurance—investment management, admin processing, compliance, and marketing all get more efficient as you grow. Sony Financial benefits from being a significant player, though it isn’t so large that scale alone becomes an unassailable moat.

Network Effects: LIMITED

This isn’t a platform business. One more policyholder doesn’t make the product better for existing policyholders. Network effects are minimal.

Counter-Positioning: STRONG

The Life Planner model is classic counter-positioning. Traditional Japanese insurers built around very different distribution—large, often part-time sales forces moving standardized products. Copying Sony’s consultative model would mean disrupting entrenched channels, retraining workforces, and potentially cannibalizing existing economics. That kind of self-disruption is exactly what incumbents tend to avoid.

Switching Costs: MODERATE

Life insurance creates real friction: surrender charges, underwriting, and—crucially—the human relationships Life Planners build over years. That improves retention, even if it doesn’t stop competitors from winning new customers at the point of sale.

Branding: STRONG

Sony’s name is a rare asset in insurance: a consumer brand associated with trust, quality, and innovation. Those attributes translate unusually well into financial services, where confidence is part of the product. Replicating that level of brand equity would take enormous time and spend.

Cornered Resource: LIMITED

Sony Financial doesn’t have a single irreplaceable resource that nobody else can ever build. Even the Life Planner approach, while hard to replicate culturally at scale, is not impossible to copy in principle—Prudential’s post-1987 growth is proof of that.

Process Power: MODERATE

Sony Life’s digital tools and paperless workflows are real advantages in speed, cost, and customer experience. But it’s a moving target: competitors are investing heavily in similar modernization, which keeps this power meaningful but not permanent.

Key KPIs for Investors to Monitor

For long-term investors, three metrics matter more than almost anything else:

-

New Business Margin: A read on whether newly written policies are actually attractive economics, not just growth for growth’s sake. Sony Life’s nearly 10% margin suggests strong discipline.

-

Life Planner Productivity: Policies written per Life Planner per month is a direct indicator of whether the model is still resonating. If productivity slips, it can signal rising competition, weaker demand, or saturation.

-

Persistency Ratios: How many policies stay in force year over year. Persistency is where consultative selling is supposed to pay off—high retention means customers feel the fit is right, and the relationship is working.

XIII. Bull and Bear Cases

The Bull Case

Sony Financial Group came out of the spin-off with some unusually durable advantages for a Japanese insurer.

Start with the simplest one: the name on the door. In a market where many competitors blend together as interchangeable financial institutions, “Sony” still signals reliability. That brand trust lowers the friction of getting a first meeting—and in insurance, getting the first meeting is half the battle.

Then there’s the operating system. The Life Planner model remains Sony Life’s defining edge: consultative, needs-based selling that tends to produce stronger productivity and better economics than traditional distribution. Pair that with Japan’s aging demographics—more retirees, longer lifespans, more demand for protection and annuities—and the demand backdrop stays supportive even in a mature market.

Management has also made it clear what “success” looks like now that the business is back in public view. For FY26, the group set targets of adjusted net income of 120 billion yen and adjusted ROE above 10%. Those are not “steady insurance company” goals. They’re a statement that SFG intends to clear its cost of capital and be valued like a focused financial services compounder, not a forgotten subsidiary.

The macro tailwind is shifting too. After years of negative rates, the Bank of Japan adjusted its monetary policy framework and raised the policy interest rate in July, pushing the uncollateralized overnight call rate higher. For life insurers, moving from negative to positive rates matters. Better reinvestment yields can lift investment returns and make annuity products easier to price attractively.

Independence is another bull argument, even if it sounds counterintuitive after a decade of conglomerate logic. As a standalone company, management can allocate capital around insurance and banking priorities without having to compete internally against PlayStation, movies, or semiconductors. The 100 billion yen share repurchase program reinforces that shareholder returns are now part of the core playbook, not an afterthought. And the shift to IFRS accounting improves comparability with international peers, which can help investors benchmark the business more cleanly.

Finally, the bank gives SFG a second growth engine that looks increasingly modern. Sony Bank’s customer satisfaction in mortgages and foreign currency deposits suggests real staying power, and its Web3 initiatives—along with its stablecoin ambitions—create optionality if those markets develop in a meaningful way.

The Bear Case

The biggest risk near term isn’t the business. It’s the stock.

A spin-off can create technical selling pressure as passive funds and index-linked strategies rebalance. In this case, passive funds may need to sell up to 125 million shares as SFG adjusts to index methodology changes. That kind of forced selling can overwhelm fundamentals for a while, even if nothing is “wrong” operationally.

Then there’s interest-rate risk—ironically, the same factor that can be a tailwind. Recent rate increases have already contributed to the duration gap re-emerging, and the group’s risk profile indicates that rising rates have increased the proportion of market risk. Translation: if rates move sharply, reported value and earnings can swing, and investors may punish the stock for volatility.

Demographics also cut both ways. Yes, Japan is aging, which supports retirement and protection demand. But Japan is also shrinking, meaning fewer new households entering prime insurance-buying years. And among younger households, participation is a concern. Non-participation rates have been rising for people in their 20s and 30s, alongside a widening knowledge gap around life insurance. If Sony can’t make insurance feel relevant, understandable, and worth paying for to younger customers, growth gets harder over time.

Competition is evolving too. Insurtech and digital-first entrants can commoditize simpler products, and that’s where younger customers may start. The Life Planner model shines when needs are complex and advice-driven. But if the next generation prefers app-based, low-touch solutions for straightforward coverage, Sony’s signature advantage may not translate as cleanly as it did in the 1980s and 1990s.

And finally, being “independent” means what it says. Without Sony Group’s balance sheet behind it, SFG has to fund growth on its own. That can tighten capital flexibility and limit how aggressively the company can pursue acquisitions or expansion opportunities, especially if markets turn hostile.

XIV. What Matters for Investors

Sony Financial Group is a rare thing: a consumer-branded financial services company in one of the world’s most mature insurance markets. And its four-decade arc—from Morita’s spark of inspiration staring up at the Prudential Building, to the Prudential joint venture and the 1987 split, to the holding-company era, the 2007 listing, the 2020 take-private, and the 2025 return to public markets—proves two things at once. The underlying business is durable. And the “right” corporate structure for it has never been obvious, even to Sony.

If you’re trying to understand what actually drives this company, start with the distribution engine. The Life Planner model is still the core advantage: trained professionals doing needs-based consulting in a category where confusion is common and mistakes are expensive. When it works, it earns trust, supports premium pricing, and creates retention that shows up in long-term economics. The open question is generational. Can a model built on face-to-face planning stay compelling for customers who expect to manage money the way they manage everything else—on a phone, on demand, with minimal friction?

Then there’s the name. In insurance, brand isn’t marketing. It’s a shortcut to credibility. Sony has spent decades proving to Japanese consumers that “Sony” can mean safety and reliability, not just innovation. That kind of trust takes a long time to earn and is painfully slow to replace if you lose it. For newer entrants—especially digital-first challengers—the hurdle isn’t just building a better interface. It’s persuading customers to hand over their family’s future to a name they don’t yet know.

The market backdrop helps too, in a very unsexy way. Japan is highly penetrated—most households already have life insurance—which limits runaway growth but supports stability. At the same time, the country’s aging population continues to pull demand toward protection, medical, retirement, and long-term care solutions. And after years of ultra-low rates, the shift toward positive interest rates can improve reinvestment yields and make certain products easier to price attractively.

For investors, though, the deciding variable is valuation—what the market is willing to pay for “steady, regulated, long-duration” cash flows after the spin-off. The first-day jump signaled that investors liked the separation and the cleaner story. Whether the stock ultimately compounds from here depends on the same fundamentals that have always mattered in insurance: sustainable new business growth, interest-rate sensitivity and balance-sheet management, and whether management can execute with the discipline of a standalone company.

And then there’s the human question hovering over the whole saga: what would Akio Morita think? The man who looked at a Chicago skyscraper and imagined Sony in finance would probably recognize this as the most Sony outcome possible—ambitious, unconventional, occasionally messy, but persistent. The Sony Financial Group story, at its core, is a case study in brand extension done patiently, in compounding built over decades, and in how far you can go when you treat “customer needs first” as an operating principle instead of a slogan.

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music