Japan Exchange Group: Remaking Japan's Capital Markets

I. Introduction: The Empire That Fell and Rose Again

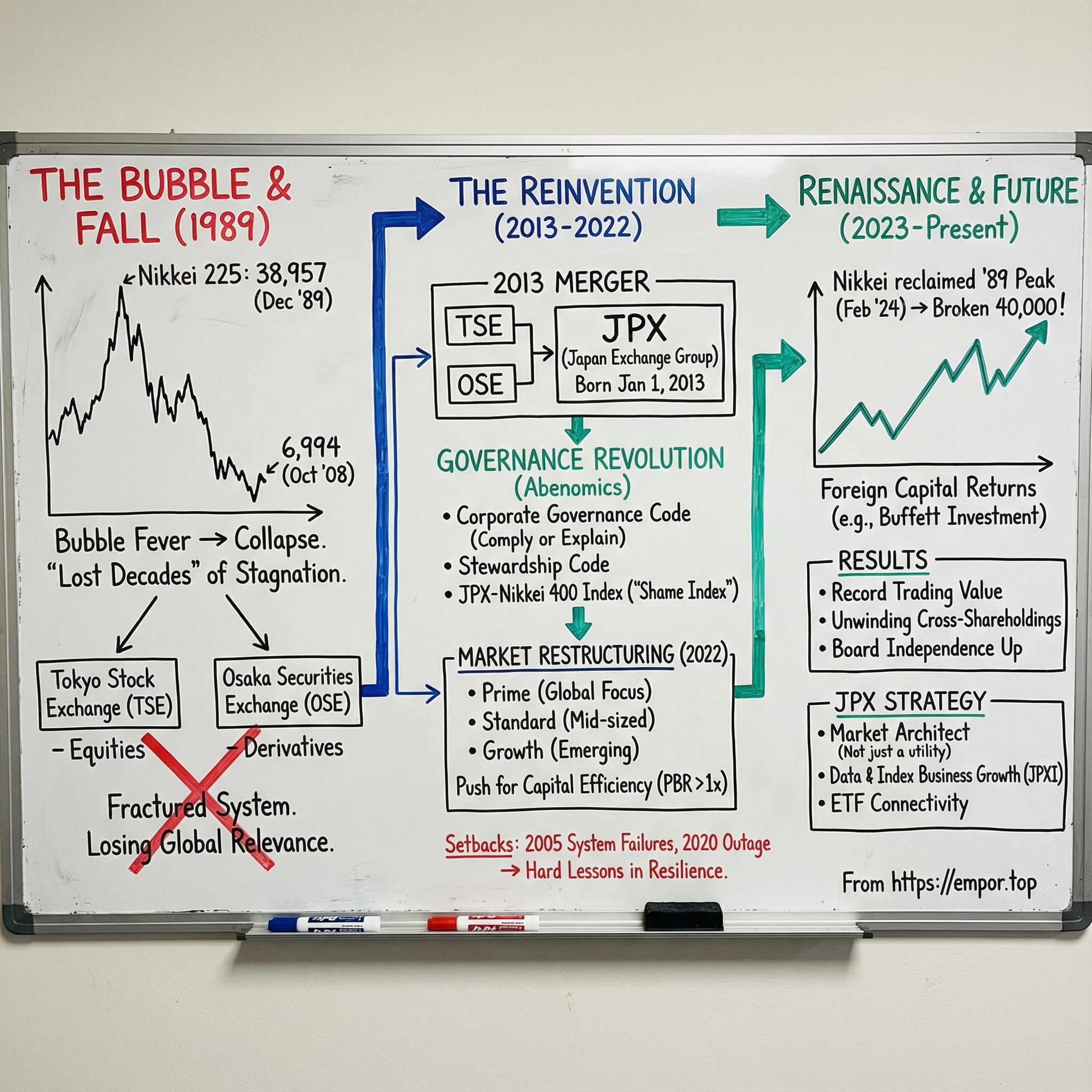

Picture this: December 29, 1989, the last trading day of the decade. On the Tokyo Stock Exchange, traders watch the Nikkei 225 close at 38,957.44. Japan is in full bubble fever. So much wealth is being “created” on paper that one of the era’s most famous claims takes hold: the land under the Imperial Palace in central Tokyo is said to be worth more than all the real estate in California combined. Japan’s stock market accounts for more than 60% of global equity market capitalization. Tokyo isn’t just a financial center. It’s the financial center.

And then the spell breaks.

The Nikkei had risen roughly sixfold over the 1980s. What followed became one of modern finance’s defining cautionary tales: the index gave back nearly all of those gains, eventually falling to an intraday low of 6,994.90 on October 28, 2008—down 82% from the peak, nearly 19 years earlier.

Now jump ahead to the present, and Japan’s exchange landscape looks radically different. As of July 2024, Japan Exchange Group is the world’s fifth-largest stock exchange operator—behind NYSE, NASDAQ, the Shanghai Stock Exchange, and Euronext—with market capitalization exceeding $5.8 trillion. That ranking alone misses the point, though. This isn’t just a story about Japan slipping and then stabilizing. It’s a story about reinvention.

JPX was created through the 2013 merger of Tokyo Stock Exchange Group, Inc. and Osaka Securities Exchange Co., Ltd., officially launched on January 1, 2013. The result was a cleaner, more deliberate division of labor: the Tokyo Stock Exchange became JPX’s core securities exchange, while the Osaka Exchange became its largest derivatives exchange.

What we’re really exploring is what happens when an institution that once symbolized global financial dominance is forced to earn relevance all over again. How does a 140-year-old exchange compete in a world of electronic markets, high-frequency trading, and global capital that can shift across borders in seconds—while facing off against rising Asian rivals like Shanghai, Hong Kong, and Singapore?

JPX’s answer wasn’t just better technology or a sharper brand. It was something more ambitious: repositioning the exchange as a kind of market architect—an enforcement mechanism for a sweeping corporate governance transformation across Japan’s economy.

For long-term investors, this story matters for three reasons. First, it shows how market structure and regulatory architecture shape outcomes—and returns. Second, it’s a case study in how “soft power,” peer pressure, and “comply or explain” can drive change where blunt regulation often fails. And third, it gets to the heart of a question that’s hovered over Japan for decades: is this a durable renaissance, or another false dawn?

II. Origins: The Birth of Japanese Capital Markets (1878–1949)

To understand what JPX is trying to do today, you have to go back to the Meiji era—when Japan made a deliberate decision to build Western-style capital markets almost from scratch.

The Tokyo Stock Exchange was established on May 15, 1878, as the Tokyo Kabushiki Torihikijo, under the direction of Finance Minister Ōkuma Shigenobu and the famed capitalist advocate Shibusawa Eiichi.

Shibusawa is the key character in this opening act. Often called the “father of Japanese capitalism,” he was a former samurai who traveled to Europe, saw firsthand what joint-stock companies could do, and came home convinced Japan needed the same machinery: corporations, investors, and a place where capital could move. In the beginning, the exchange wasn’t really about equities at all. It functioned largely as a marketplace where ex-samurai could trade government bonds. Over time, as Japan’s corporate sector took shape, the center of gravity shifted. Stock trading grew, and by the 1920s, it became the exchange’s dominant activity.

The government wasn’t just encouraging markets from the sidelines—it was actively engineering them. After the Meiji Restoration, Japan introduced a system to establish stock companies to accelerate industrial growth. At the same time, it issued a range of government bonds, including former public bonds and salary bonds, as part of unwinding the feudal economic order. As trading in these bonds became more active, the demand for formal trading institutions rose with it. On May 4, 1878, the government enacted a Stock Exchange Ordinance—essentially laying down the rules for this new financial infrastructure.

This wasn’t merely institution-building. It was nation-building through finance. Japan’s leaders understood that industrialization required capital, and capital required trust. The exchange became both a practical tool and a symbol: proof that Japan could modernize, organize, and play by the rules of global commerce.

Meanwhile, Osaka developed a parallel—almost complementary—identity. The Osaka Securities Exchange leaned heavily into derivatives trading. That wasn’t an accident. Osaka had deep roots in futures markets going back centuries, including the famed rice futures market at Dojima, often credited as the world’s first organized futures exchange. Over time, Tokyo and Osaka developed different market personalities: Tokyo as the home of equities, Osaka as the home of derivatives. That split would persist for more than a century, right up until the 2013 merger brought the two back under one roof.

Then the war years compressed everything. In 1943, the exchange was combined with eleven other stock exchanges in major Japanese cities into a single Japanese Stock Exchange. It was shut down on August 1, just days before the bombing of Hiroshima. When Japan rebuilt, the market had to be rebuilt too. The Tokyo Stock Exchange reopened under its current Japanese name on May 16, 1949, pursuant to the new Securities Exchange Act.

The American occupation reshaped the entire system. Occupation authorities dismantled the zaibatsu—the family-controlled conglomerates that dominated pre-war Japan—and imposed American-style securities regulation aimed at investor protection and broader stock ownership. A wave of shares that had been frozen during the zaibatsu breakup were discharged back into the market. Securities “democratization” efforts spread nationwide, meant to diffuse knowledge about investing and securities. In April 1948, a new Securities Exchange Law, grounded in investor protection, was enacted. On April 1, 1949, the Tokyo Stock Exchange was created as a membership organization, and operations resumed the following month, on May 16.

The investor takeaway is that Japan’s market DNA has always been a hybrid: Meiji-era ambition and institution-building layered with postwar, American-influenced regulation. That blend created real strengths—but also structural quirks and constraints that JPX would eventually have to confront head-on.

III. The Bubble Era and Collapse: From Global Dominance to Lost Decades (1983–2000s)

The bubble years were the high-water mark of Japanese financial power—and the moment the structural flaws in the system got locked in. To understand why JPX later tried to reinvent itself as an enforcer of better corporate behavior, you have to understand how Japan’s market got so rich, so fast… and then stayed stuck for so long.

In the mid-1980s, Japanese stocks didn’t really trade on “earnings” in the way global investors might expect. They traded on assets—especially land. In 1984, the Nikkei 225 churned inside a fairly tight band. Then, as Tokyo real estate began to levitate in 1985, equities followed. By the end of that year the Nikkei had pushed above 13,000, and in 1986 it surged again, rising by roughly 45% in a single year.

By 1988 and 1989, the move turned into a frenzy. The Nikkei ultimately hit its iconic peak of 38,957.44 on December 29, 1989. From the start of 1985, it was up well over 200%. Tokyo looked unstoppable.

What powered that rise was a combustible mix: easier money after the Plaza Accord, rampant speculation in real estate, and a very Japanese feature of corporate capitalism—cross-shareholding.

Banks didn’t just lend to companies; they owned them. Companies didn’t just do business with suppliers and customers; they owned pieces of them too. Over time, these “strategic” stakes spread across the keiretsu groups that dominated Japan’s industrial rise. The result was a dense web of mutual ownership that made management teams unusually hard to dislodge. Shareholders existed, but shareholder pressure often didn’t.

And the market priced that insulation in. At the peak, the Nikkei traded at around 60 times trailing earnings, while global equities were closer to the mid-teens. Japan wasn’t just expensive. It was in a different universe.

Then the oxygen got cut off.

In 1989, monetary policy tightened. Borrowing costs rose, land prices slowed, and the logic of ever-rising asset values started to crack. In early 1990, stocks fell hard. By the end of that year, the Nikkei had lost more than 40% from its level at the start of the year. The bubble hadn’t “deflated.” It had burst.

What followed wasn’t just a market downturn. It was an unraveling of the ownership system that had helped inflate the bubble in the first place. As share prices sank, financial institutions in particular were forced to confront massive losses embedded in their equity holdings. The interlocking alliances that once looked stabilizing now looked fragile. By the mid-1990s, the unwind began: banks and corporates started selling down strategic stakes, slowly and painfully.

Here’s the psychological scar that shaped the next generation of Japanese capital markets: that 1989 high stood for 34 years. It wasn’t surpassed until 2024. In other words, if you bought the Nikkei at the peak, you waited until February 2024 just to get back to even on price. Dividends helped over time, but the message to investors—domestic and foreign—was unmistakable: Japan could take your capital and trap it.

During these same years, the Tokyo Stock Exchange modernized its machinery—but mostly in response to necessity, not as part of a bold reinvention. The iconic trading floor closed on April 30, 1999, as the exchange moved to fully electronic trading. In 2010, the TSE launched its Arrowhead trading facility, a major step forward in speed and capacity.

But faster pipes didn’t solve the deeper problem. Japan could upgrade the exchange’s technology and still leave investors facing the same underlying reality: a corporate system designed to protect insiders, preserve relationships, and treat shareholder returns as optional.

The investor takeaway is simple: the Lost Decades weren’t only about collapsing asset prices. They were about incentives. Any true recovery would require changing how corporate Japan was governed—not just waiting for the Nikkei to climb back.

IV. System Failures and Wake-Up Calls (2005–2006)

Every institutional transformation needs a catalyst: a moment when the cost of complacency becomes undeniable. For the Tokyo Stock Exchange, that moment didn’t arrive as a slow realization. It arrived as a public faceplant—followed by another.

On November 1, 2005, the exchange managed to trade for only 90 minutes before a newly installed transaction system—built by Fujitsu and meant to handle rising volumes—started throwing bugs. Trading was suspended for roughly four and a half hours. At the time, it was the worst disruption in the exchange’s history, and it rattled confidence in the basic plumbing of Japan’s market.

Then came the incident that turned a system problem into a national scandal.

On December 8, 2005, during the IPO of a recruiting company called J-Com, a trader at Mizuho Securities made a now-famous “fat finger” mistake. The order was supposed to be simple: sell one share at ¥610,000. Instead, it was entered as selling 610,000 shares at ¥1 each. The order size was wildly out of proportion—dozens of times larger than J-Com’s shares outstanding—and yet it still went through.

Mizuho said it tried multiple times to cancel the order, but the Tokyo Stock Exchange wouldn’t unwind executions, even when they were clearly erroneous. By the end of the day, Mizuho—part of Mizuho Financial Group—had suffered a staggering loss, reported at the time as at least ¥27 billion (about $225 million).

The damage wasn’t confined to one brokerage. The episode shook the broader market. Coming just weeks after the system glitch, it fueled a new kind of fear: not “are Japanese stocks attractive,” but “is the exchange itself reliable?” Japan’s government publicly rebuked both the exchange and the brokerage firm. The reputational hit landed right where it hurt most—credibility.

The consequences inside the TSE were immediate. On December 21, 2005, chief executive Takuo Tsurushima and two other senior executives resigned over the Mizuho affair.

What made these back-to-back failures so consequential wasn’t only the money. It was what they revealed. Here was a modern, all-important financial institution that couldn’t stay open through normal volume—and couldn’t stop a plainly impossible trade from cascading through the market. The organization looked trapped in procedure, unable to respond to obvious reality in real time.

The legal fallout dragged on, too. After Mizuho filed suit seeking ¥41.5 billion, the Tokyo District Court ordered payment. Mizuho’s position was straightforward: it realized the mistake immediately and submitted cancellation requests, but the exchange failed to process them because of a defect in its electronic trading system. Mizuho then had to buy back shares from market investors at a massive loss.

For long-term investors, the takeaway was sharper than any headline: the Tokyo Stock Exchange wasn’t just behind on technology. It was behind on institutional reflexes. And that raised the question Japan couldn’t avoid much longer—was the TSE actually fit for purpose in a global financial system?

V. Inflection Point #1: The TSE-OSE Merger (2011–2013)

The merger that created Japan Exchange Group wasn’t born of a grand vision. It was born of a hard reality: by the early 2010s, Japan’s markets were no longer the default destination in Asia, and the Tokyo and Osaka exchanges were struggling to grow in a world where liquidity and attention were increasingly global.

On November 22, 2011, the Tokyo Stock Exchange and Osaka Securities Exchange agreed to merge. The pitch was straightforward. Tokyo dominated cash equities. Osaka was the country’s center of gravity for derivatives. Put them together and you don’t just get a bigger exchange—you get something closer to a complete marketplace, a single front door for investors who want Japan exposure across products.

And there was urgency behind the deal. Japan’s stock market had fallen from world-beating status to fighting for mindshare against fast-rising regional competitors. Without a move like this, the fear wasn’t abstract. It was that Tokyo’s relevance would keep shrinking, one incremental reroute of global order flow at a time.

Regulators signed off in the summer of 2012, when the Japan Fair Trade Commission approved the merger. Japan Exchange Group officially launched on January 1, 2013.

Then came the first real market verdict. JPX listed on January 4, 2013, and shares fell 9.4% on day one. Investors weren’t celebrating “synergies.” They were asking a blunt question: does combining two slow-growing institutions produce a champion—or just one larger version of the same problem?

Internally, the hardest part wasn’t the press release. It was the integration. Tokyo and Osaka weren’t just different offices. They had different histories, different cultures, and different systems. And for all the talk of efficiency, this merger didn’t magically resolve the deeper challenge Japan faced: modernize the market structure, raise standards, and make the country investable again for a new generation of global capital.

In hindsight, that’s what the merger really accomplished. It created an organization with the scale—and the mandate—to do more than run markets. JPX could now start redesigning them.

VI. Inflection Point #2: Abenomics and the Corporate Governance Revolution (2012–2015)

Shinzo Abe’s return to power in December 2012 changed the trajectory of Japan’s markets. He didn’t just promise a recovery. He showed up with a framework—Abenomics—and its famous “three arrows”: monetary easing, fiscal stimulus, and structural reform.

That third arrow was the one that mattered most for JPX. Because structural reform meant taking on a problem Japan had lived with for decades: companies that were safe, stable, and sometimes spectacularly inefficient with capital. Abe’s team made corporate governance reform a centerpiece. The Liberal Democratic Party set up its Japan Economic Revival Headquarters, published a revitalization strategy in 2013, listed governance reform as one of its key areas, and pushed for changes to the Companies Act. In 2014, it followed with a more detailed vision, and the revised strategy confirmed a corporate governance code was coming.

Then the machinery clicked into place.

Japan rolled out what became a paired set of “soft law” reforms: the Stewardship Code in 2014 and the Corporate Governance Code in 2015. The idea was explicit: two wheels of a cart. One aimed at investors—encouraging institutional shareholders to behave like stewards, not passive bystanders. The other aimed at companies—laying out the principles of what “good governance” should look like in modern Japan.

The key design choice was the mechanism. These weren’t hard mandates. They were built around “comply or explain.” Companies could follow the principles, or they could explain—publicly—why they didn’t. The Corporate Governance Code was deliberately principles-based and non-prescriptive, written in broad terms to leave flexibility. But that flexibility came with a trade: you now had to tell the market what you were doing, and why.

And that’s where JPX stepped into a new role. Not just as an operator of trading systems, but as an enforcer of the new social contract between Japanese companies and global capital.

In November 2013, just months after the merger, JPX and Nikkei launched the JPX-Nikkei Index 400. It was designed to spotlight companies with stronger profitability and capital efficiency—traits that, in practice, were tightly linked to better governance and investor-oriented management. The index was jointly developed by Nikkei, Japan Exchange Group, and the Tokyo Stock Exchange, and it quickly became known as “the shiniest toy in the Abenomics box.”

This was governance by leaderboard.

In Japan, membership mattered. The JPX 400 wasn’t just another benchmark. It became a public signal of being “well-run,” boosted by formal endorsement from the Government Pension Investment Fund and intense media attention around the annual reshuffle. Its reputation was so potent that it picked up a nickname: “the shame index,” for the sting executives felt when their companies were left out.

This was governance through reputation—peer pressure with a ticker symbol. And it worked better than many expected. Since 2016, companies in the TOPIX Index increased average board independence by nine percentage points to 34.0%, while average female board representation rose four points to 7.6%. Those figures still trailed comparable indices in the U.S. and Europe, but the direction was unmistakable.

You could see the change in more basic terms too. In 2014, before the Corporate Governance Code was adopted, there were dozens of MSCI Japan constituents assessed as having zero independent directors. Today, every constituent has at least one director assessed as fully independent of management.

The investor takeaway is that JPX didn’t just benefit from Abenomics. It became one of the tools that made Abenomics real—turning governance reform from a policy slogan into a set of market incentives that executives couldn’t ignore.

VII. Expanding the Platform: TOCOM Acquisition and ETF Connectivity (2018–2021)

Once the governance flywheel was spinning, JPX went looking for the next lever: breadth. If Tokyo was going to matter again in a world of global, cross-asset capital, it couldn’t just be an equities venue. It needed to feel like a platform.

The clearest move came on October 1, 2019, when JPX acquired Tokyo Commodity Exchange, Inc. (TOCOM). TOCOM became a wholly owned subsidiary, and JPX officially stepped into commodity derivatives.

This wasn’t a vanity acquisition. It added a new set of futures markets—precious metals, rubber, and energy products—that rounded out the group’s derivatives franchise. For investors, the appeal was simple: one exchange group where Japan exposure could span equities, equity derivatives, and commodities.

JPX also pushed outward, not just sideways. In June 2019, it partnered with the Shanghai Stock Exchange to launch Japan-China ETF Connectivity, a program that enabled the joint listing of exchange-traded funds. It was another attempt to position Tokyo as a practical gateway for international money looking for Asia exposure—especially in products built for global portfolios.

Then, in November 2021, JPX launched a new subsidiary: JPX Market Innovation & Research, Inc. (JPXI). Its job was to provide financial market data, price index services, and system-related services to financial data vendors.

This, too, was a tell. JPX was acknowledging what every major exchange operator has learned over the past decade: trading fees are only one part of the business. Data and indices are where the compounding happens. As passive investing reshaped how capital moves, the firms that create benchmarks and control market data gained outsized influence. By housing those capabilities inside JPXI, JPX was building the infrastructure to compete for that influence—and the revenue that comes with it.

VIII. Crisis Management: The 2020 System Outage

Just as JPX was building momentum on governance reform, the technology story came roaring back. On October 1, 2020, the Tokyo Stock Exchange suffered its worst outage since it became fully electronic in 1999: it couldn’t open at all. Buying and selling froze across thousands of listed companies for the entire day.

JPX’s initial explanation was blunt. A hardware failure hit a data storage component, and what should have been a routine recovery turned into a breakdown of the breakdown plan. The exchange said the problem wasn’t just the fault itself, but the failed switchover to the backup system that was supposed to keep markets running.

The specific culprit was a data storage component called the Number 1 Shared Disk device, which detected a memory error. In theory, the database software would automatically fail over to the secondary setup, using the Number 2 Shared Disk device. That automatic failover didn’t happen. TSE staff forced a manual changeover—but that created a new problem: to restart trading, the system would require a full reboot, with existing orders left in limbo. That was an unacceptable state for a national market utility. So the exchange made the only defensible call left: stay closed until it could recover properly.

In the press conference that followed, TSE executives didn’t try to push the blame onto Fujitsu, the vendor behind the system. Tokyo Stock Exchange CEO Koichiro Miyahara put it plainly: “All the responsibility lies with us as the market operator.” Fujitsu, he emphasized, was “merely a vendor that supplies the equipment.”

The timing couldn’t have been worse. Prime Minister Yoshihide Suga had made digitalization a priority, and Tokyo was still trying to strengthen its case as a credible global financial center. Instead, the exchange had just demonstrated that its most basic promise—markets open, prices discover, trades settle—could fail in full public view.

The accountability was swift. Miyahara decided to resign over the outage. Standing in front of reporters, he apologized for the full-day shutdown and stressed that the exchange was supposed to be “a crucial piece of infrastructure for the financial markets.” Observers immediately drew comparisons to 2005, when TSE leadership was forced out after disruptions that, while serious, were nowhere near as severe as a full-day halt.

The crisis also accelerated a leadership transition that would shape JPX’s next phase. On April 1, 2021, Hiromi Yamaji took over as head of the Tokyo Stock Exchange, succeeding Miyahara after the October 2020 outage. Yamaji brought a different profile to the job—more markets, more global, more derivatives. He had joined JPX in June 2013 as CEO of Osaka Exchange and helped build out JPX’s derivatives operations, later becoming CEO of the Tokyo Stock Exchange in April 2021. Before JPX, he’d worked in Europe and the U.S., serving as president and CEO of Nomura Europe Holdings in London and chairman of Nomura Holding America in New York. He graduated from Kyoto University’s law faculty and earned an MBA from Wharton.

That international perspective—and the urgency created by an outage that Japan couldn’t afford to repeat—would matter for what came next.

IX. Inflection Point #3: The 2022 Market Restructuring—Prime, Standard, Growth

By 2022, JPX had already modernized trading, merged Tokyo and Osaka, and helped turn “governance reform” into something companies actually felt. But there was still a stubborn problem hiding in plain sight: even the Tokyo Stock Exchange’s own map of the market had become confusing and ineffective.

On April 4, 2022, JPX pushed through its most sweeping redesign yet: a full restructuring of the TSE’s market segments.

For years, the TSE had operated with a patchwork of divisions—1st Section, 2nd Section, Mothers, and JASDAQ. When Tokyo and Osaka integrated their cash equity markets in 2013, the TSE largely kept these legacy segments intact to avoid disrupting listed companies and investors. Over time, though, that decision started to look like technical debt. The boundaries between segments were blurry, which made the market harder for investors to navigate. And just as importantly, the segments didn’t create strong enough incentives for companies to sustainably increase corporate value.

So the TSE went back to the drawing board. After researching how to restructure the market in a way that would be clearer to investors and more demanding for issuers, it launched three new segments on April 4, 2022: Prime, Standard, and Growth.

The idea was simple and strategic. Prime would be the global showcase. Standard would serve established mid-sized companies. Growth would be the home for emerging companies. The reorganization was designed to make Tokyo more legible as a marketplace—and to push companies toward better mid- to long-term value creation.

Prime, in particular, was positioned as the crown jewel: a market centered on constructive dialogue with global investors. That positioning mattered because it tied directly to governance. The TSE, as the implementer of Japan’s Corporate Governance Code, revised the Code to further encourage companies to strengthen governance for sustainable growth. And for Prime-listed companies, the bar was raised: higher standards applied.

The eligibility requirements reflected that intent. Prime required a larger base of tradable shares and a higher tradable-share ratio than the other segments. Standard lowered the threshold, while Growth was designed for smaller, earlier-stage companies, still with meaningful requirements around free float.

But the restructuring was only the stage-setting. The more important realization came after: even with clearer segments and higher standards, Japan’s capital efficiency and market valuation still lagged developed-market peers. Measures like ROE and price-to-book ratio remained stubbornly weak. As of July 2022, roughly 40% of companies in the TOPIX 500 had ROE below 8%. And a large share of Japanese companies still traded below a PBR of one—a signal, at least in the market’s eyes, that capital wasn’t being used effectively.

So the TSE escalated.

In March 2023, it issued what would become one of its most consequential requests yet: all companies listed on the Prime and Standard Markets were asked to take action to implement management that is conscious of cost of capital and stock price.

This was “comply or explain” turned up a notch—especially for companies trading below a PBR of one. And it landed in a political moment that amplified the pressure. Prime Minister Fumio Kishida had pledged to make Japan Inc. a more attractive investment proposition for both foreign investors and Japanese households. The exchange wasn’t just offering a better venue for trading anymore. It was leaning into its role as the mechanism that would force the conversation—company by company—about why shareholder value in Japan had lagged for so long.

X. The Governance Revolution Bears Fruit (2023–Present)

By 2023, the Tokyo Stock Exchange had stopped hinting and started doing something far more uncomfortable in Japan: making corporate inaction visible.

It began with the March 31, 2023 request to every company on the Prime and Standard Markets: take action to implement management that is conscious of cost of capital and stock price. The request itself wasn’t a law. It didn’t come with fines. The leverage was social and market-based—disclosure, comparison, and reputational pressure.

And in January 2024, the TSE tightened the screws. It began publishing a list of companies that had disclosed information in line with the request. Officially, the list was framed as a tool for investors—so the market could see who was taking the issue seriously. Unofficially, it functioned as something else, too: a scoreboard.

The list only included companies that had complied, which meant it didn’t explicitly call out those that hadn’t. But in a market full of analysts, brokers, and investors, that distinction didn’t last long. Firms and shareholders reportedly “reverse engineered” the non-responders by comparing the list to the full set of Prime and Standard listings. The result was exactly what the exchange was aiming for: peer pressure inside industries, and a steady improvement in corporate responses over time.

One of the clearest signs of momentum showed up in one of Japan Inc.’s most entrenched traditions: cross-shareholding. That decades-old web of interlocking ownership had long protected management from accountability and muted shareholder influence. As those crossholdings began to unwind, it didn’t just improve governance optics—it created real financial capacity. Proceeds could be recycled into dividends, share buybacks, and strategic moves like M&A, directly raising pressure on capital efficiency.

In the insurance sector, the shift was especially striking. Major casualty insurers, under regulatory pressure, committed to exiting all cross-shareholdings within six years. Because those holdings represented a large share of their capital, the implications were immediate: more flexibility in capital returns, the prospect of improved ROE versus global peers, and a sharp positive reaction in insurance share prices.

Then came the endorsement that made global investors pay attention in a different way: Warren Buffett.

Buffett said he was “confounded” by the opportunity he saw in Japan’s trading houses—companies that, in his telling, offered high earnings yields and growing dividends. Berkshire Hathaway revealed it had raised its stakes in each of five major Japanese trading firms to 7.4%, and Buffett added he may consider further investments. He first disclosed the positions in August 2020, saying he had built them through regular purchases on the Tokyo Stock Exchange and was drawn to the firms’ shareholder returns and capital allocation.

By the end of 2024, Berkshire’s Japanese holdings were valued at $23.5 billion versus an aggregate cost of $13.8 billion. Berkshire now owns about 8.5% on average across the five trading houses. The message landed: this wasn’t just a domestic reform story anymore. Global capital was watching—and buying.

The market itself punctuated the shift. In February 2024, the Nikkei finally cleared its 1989 peak. On February 22, it set an intraday high of 39,156.97 and closed at 39,098.68, surpassing the record that had haunted Japan for decades. Less than two weeks later, on March 4, the index broke 40,000 for the first time in history.

And the tape backed it up. In 2024, trading value in Prime Market domestic common stocks hit an all-time high of roughly JPY 1,254 trillion. Domestic ETF trading value also reached a record, at about JPY 77 trillion.

Derivatives activity surged too. Trading volume in JPX’s derivatives market climbed to a record 464,165,639 contracts in 2024, with trading value reaching 4,156 trillion yen—both all-time highs.

XI. Porter's Five Forces Analysis

Threat of New Entrants: LOW

Starting a new exchange in Japan isn’t like launching a fintech app. The regulatory moat is deep: financial instruments exchange licenses from the FSA are scarce and hard to secure. Then come the economics. You need massive upfront investment in technology and market infrastructure, and you still face the cold-start problem that kills most would-be challengers: liquidity. Traders go where the volume is, and volume goes where the traders are. Listed companies and investors don’t casually pick up and move.

JPX isn’t completely insulated, though. Alternative trading systems have been steadily chipping away at the edges. SBI Japannext and Chi-X Japan have taken share over time. Even so, the Tokyo Stock Exchange still accounts for about 80% of Japan’s equities trading, offering the core menu—major stocks, ETFs and ETNs, REITs—and anchoring the ecosystem around widely used benchmarks like the Nikkei 225 and TOPIX.

Bargaining Power of Suppliers: LOW-MODERATE

If you run a national market utility, your vendors matter. Technology partners like Fujitsu have leverage because trading systems are mission-critical—as JPX relearned the hard way in the 2020 outage. But that leverage has limits. Market data feeds are largely standardized, and key post-trade infrastructure is kept close to home: clearing is handled in-house through the Japan Securities Clearing Corporation (JSCC).

Bargaining Power of Buyers: MODERATE

On the trading side, the biggest customers—large institutional investors—have options. They can route orders to alternative venues, which gives them meaningful negotiating power.

On the listing side, the balance flips. For most Japanese companies looking to raise capital at home, there’s no true substitute for a primary listing on the TSE. That asymmetry matters: investors can shop around for execution, but issuers have far fewer doors to knock on. That dynamic gives JPX real leverage in its listing franchise.

Threat of Substitutes: MODERATE-HIGH

The substitutes aren’t just other exchanges. They’re other ways of funding a business. Private markets, direct listings, and foreign exchanges all offer alternate paths to capital.

Crypto and decentralized exchanges are the longer-horizon wildcard—interesting, potentially disruptive, but still far from being an institutional-grade replacement for mainstream equity markets. The more immediate risk is simpler: if Tokyo doesn’t stay competitive, Japanese companies may decide their future investors are in Hong Kong, Singapore, or New York.

Competitive Rivalry: MODERATE

Domestically, JPX is close to a monopoly. Globally, it’s in a fight. Hong Kong, Singapore, and Shanghai all compete for listings and for the attention of international capital.

So the real contest isn’t a street brawl for local market share. It’s a quieter, higher-stakes battle for relevance—making sure Tokyo remains a place global investors choose when they allocate to Asia, rather than a market they ignore by default.

XII. Hamilton's 7 Powers Analysis

1. Scale Economies: STRONG

Running an exchange is a fixed-cost business. Once you’ve built the pipes—Arrowhead, J-GATE, and the clearing stack—you want as many trades as possible flowing through them, because the marginal cost of each additional trade is tiny. JPX gets to spread those costs across enormous activity, helped by the Tokyo Stock Exchange’s roughly 80% share of Japan’s equities trading. The 2013 TSE-OSE merger was, at its core, a scale play: combine two national champions, take out duplication, and create a platform big enough to keep investing in world-class infrastructure. Later moves—like bringing TOCOM into the group and expanding data and index capabilities—extended the same logic into adjacent markets.

2. Network Economies: VERY STRONG

This is the flywheel. Liquidity attracts liquidity: listed companies want the deepest pool of buyers; investors want the most tradable market; market makers want the tightest spreads; and each new participant makes the whole venue more valuable. JPX sits at the center of that loop. It is the fourth-largest stock exchange in the world, with around 3,960 listed companies and market capitalization of $6.4 trillion as of January 31, 2025. For anyone seeking broad exposure to Japanese equities, the Tokyo Stock Exchange is the default destination precisely because everyone else is already there.

3. Counter-Positioning: MODERATE

JPX has taken a stance that’s hard for rivals to mirror without paying a price: it has leaned into governance activism—publishing compliance progress, applying pressure around PBR, and generally pushing listed companies toward more investor-friendly behavior. A competitor could try to copy that, but an exchange that publicly pressures its own issuers risks scaring off listings. JPX is effectively betting that better governance raises the overall attractiveness of the market enough to outweigh the friction it creates with some companies. So far, that bet appears to be working—but it naturally creates tension that JPX has to manage.

4. Switching Costs: VERY STRONG

For issuers, leaving isn’t a simple “take your business elsewhere” decision. Delisting and relisting comes with heavy costs: disrupting a domestic shareholder base, navigating regulatory and disclosure requirements, and risking exclusion from key indices. For investors, the ecosystem is sticky too—accounts, custody, and settlement workflows are built around JPX’s infrastructure. Once companies and capital are embedded in that system, the default behavior is to stay.

5. Branding: STRONG

The “Prime Market” label has become a shorthand for quality—Tokyo’s signal to the world about which companies are meant to meet a higher bar. That’s reinforced by the way governance is embedded into the exchange’s rules: Tokyo Stock Exchange, Inc. incorporates the principles of Japan’s Corporate Governance Code into its listing framework, and Prime or Standard companies are required to explain any non-compliance with the Code’s principles. More broadly, the TSE brand is still synonymous with Japan’s capital markets. For better or worse, investing in Japan usually means interacting with JPX.

6. Cornered Resource: MODERATE

JPX sits on assets that are hard to replicate. TOPIX and the Nikkei are essential benchmarks, even though the Nikkei is licensed from Nihon Keizai Shimbun rather than owned outright. And the biggest “resource” is regulatory: being designated a financial instruments exchange is a scarce privilege. There simply aren’t many alternative paths to operating a full-service exchange in Japan.

7. Process Power: EMERGING

JPX is trying to turn repeated execution into durable advantage: better surveillance, sharper market structure, stronger governance enforcement, and the operational muscle to keep markets reliable while attracting global capital. As one leader put it, JPX faces tasks tied to supporting a changing business environment and bringing in global money: “We have to keep on brushing up on these three points to always remain competitive against stock exchanges around the world.” The question is whether those improvements compound into true process power—an institutional capability that’s difficult for competitors to copy—or whether they remain simply the cost of staying in the game.

XIII. Business Model & Playbook Lessons

The Exchange as Market Architect

JPX’s story flips the usual script. We tend to think of exchanges as neutral utilities: they match buyers and sellers, keep the lights on, and stay out of the way. JPX has done almost the opposite. It has tried to shape the behavior of the companies that depend on it.

The playbook is visible in the levers JPX has pulled: tightening listing standards, using public disclosure to create a de facto scoreboard, and launching governance-focused indices that turn “better management” into something measurable. The bigger lesson is that an exchange can be a policy instrument, not just a trading venue. In Japan’s case, the exchange became one of the primary mechanisms for translating national economic goals into corporate incentives.

Regulatory Symbiosis

JPX’s advantage isn’t only scale or technology. It’s its relationship with the rulemakers. The exchange, the Financial Services Agency, and the government have moved in the same direction for much of the past decade, especially on governance reform.

What’s distinctive here is that the reforms weren’t simply imposed on the exchange. They were executed through the exchange. That alignment matters because it gives JPX political backing for initiatives that inevitably create friction with some listed companies. In a market where change is often slow, the ability to make reform “the rules of the venue” is a powerful edge.

The "Comply or Explain" Innovation

Japan’s governance shift was built less on hard mandates and more on social pressure, and “comply or explain” is the mechanism that makes that work. Instead of dictating exact behavior, the codes set expectations and force companies to either meet them or explain, in public, why they won’t.

That approach fits Japan’s consensus-driven corporate culture unusually well. As Nomura’s chief equity strategist told CNBC: “Delisting or any punishment or any enforcement is quite unlikely, but the good news in Japan is there is the peer pressure factor. If rival companies are doing great improvements in corporate governance, others will tend to follow that move.”

JPX’s lesson here is simple: transparency can be enforcement, if the culture and incentives are set up to make comparison sting.

Consolidation Strategy

JPX also shows the strategic upside of consolidation when an industry is defined by fixed costs and network effects. Tokyo and Osaka had overlapping missions but different strengths. Bringing them together didn’t just create efficiency—it created room to invest.

The merger enabled upgrades in technology and governance infrastructure that would have been harder for either exchange to fund alone. And once JPX had proven it could integrate big pieces of market plumbing, extending that logic to commodities through the TOCOM acquisition became a natural next step.

The Data and Index Business

Like every modern exchange operator, JPX has been steadily building a business beyond transaction fees. Data and indices are the compounding engine: higher-margin, stickier, and more recurring than pure trading revenue.

That’s why JPX housed these capabilities in JPX Market Innovation and Research, Inc. (JPXI). By 2024, the data service segment accounted for 20% of JPX’s total revenue, up from less than 18% in 2019. Listing services also contribute meaningfully. The directional takeaway is what matters: JPX is diversifying away from the volatility of trading activity and toward businesses that turn market participation into durable, repeatable revenue.

XIV. Key KPIs for Investors

If you’re tracking JPX as a business, or Japan as an investable market, there are three numbers that tell you whether the story is getting stronger—or stalling out.

1. Prime Market Trading Value (Daily Average)

The simplest signal is whether investors are actually showing up. In FY2024, the Prime Market’s domestic common stocks averaged about JPY 5.06 trillion in trading value per day.

That’s not just a “liquidity” stat. It’s a real-time vote of confidence. If trading activity keeps climbing, it suggests global and domestic investors are leaning into Tokyo’s direction of travel: higher standards, better governance, and more shareholder-minded management. If it starts fading, that’s a sign either the cycle has turned, or the reform narrative is losing its pull.

2. Governance Disclosure Compliance Rate

JPX’s governance push only works if companies respond—and the cleanest way to measure that is disclosure.

This is the exchange’s core “output metric”: the share of Prime and Standard companies that have put out plans to improve cost of capital and stock price. As of May, JPX reported that 92% of Prime Market stocks and 51% of Standard Market stocks had disclosed those plans.

The key is not just whether this number rises. It’s whether disclosure turns into action—better capital allocation, fewer balance sheets stuffed with idle cash and cross-holdings, and more visible returns to shareholders.

3. Foreign Investor Net Flows

Finally, watch the marginal buyer. In Japan, foreign investors are especially important—they account for a large share of trading volume, and they’re the least sentimental capital in the system.

Sustained net inflows are the market validating JPX’s governance thesis in the most direct way possible: with money. Persistent outflows, on the other hand, are the warning light that the reform story isn’t translating into enough shareholder value to keep global capital engaged.

XV. Risks and Regulatory Considerations

Technology Risk

JPX has learned the hard way that, for an exchange, trust is uptime. The breakdowns in 2005 and the all-day halt in 2020 proved that even world-class market infrastructure can fail—and when it does, the damage isn’t just operational. It’s reputational. JPX has invested to harden systems and improve recovery procedures since each incident, but modern markets run on complex, tightly coupled technology. That means the risk never goes to zero. Another major outage would land at the worst possible time: just as Japan is trying to convince global investors that its markets are more modern, reliable, and globally competitive.

Governance Reform Durability

A big part of the governance revolution has been momentum: political backing, supportive markets, and high-profile validation like Warren Buffett’s. But momentum can fade. A prolonged bear market, a shift in political priorities, or simple reform fatigue could all weaken the pressure on management teams to change. The “comply or explain” model only works when “explain” carries a real cost—scrutiny from investors, attention from regulators, and the uncomfortable comparison with peers. If that attention drifts, the mechanism loses teeth.

Currency Exposure

For foreign investors, Japan’s equity story has always come with a second bet attached: the yen. Even when local stock returns are strong, a weakening currency can erase the gains in dollar terms. The sustained depreciation of the yen against the dollar has been a persistent headwind, and it shapes sentiment toward Japan as an allocation. JPX’s performance is ultimately tied to confidence in Japan’s broader economic trajectory—and that includes the perception of currency stability.

Competition from Regional Markets

Tokyo isn’t rebuilding its status in a vacuum. Shanghai, Hong Kong, and Singapore keep courting listings and capital, and they’re doing it with their own combinations of liquidity, access, and incentives. JPX’s edge is that it’s trying to differentiate on quality—higher governance expectations, clearer market segmentation, and a more investor-facing posture. But differentiation is only valuable if it shows up in outcomes. The real test is whether Tokyo’s reforms translate into sustained market performance that convinces issuers to stay, and convinces global capital to keep showing up.

XVI. Conclusion: The Unfinished Revolution

Japan Exchange Group is back at the center of a story many investors had written off. After more than three decades of waiting, the Nikkei climbed back past its bubble-era peak. Trading and derivatives activity reached record levels. Foreign investors returned. Warren Buffett didn’t just visit—he doubled down.

But the real question isn’t whether Japan had a great year. It’s whether Japan is finally changing in a way that lasts.

The governance push JPX helped turn into lived reality is a structural shift, not a cyclical one. Cross-shareholdings—the old web that insulated management and dulled shareholder pressure—have been unwinding. Boards have become more independent. Companies are, at least increasingly, being forced to talk about capital efficiency in public, and to justify why their stock should be worth more than the assets on their balance sheet.

As Hiromi Yamaji, CEO of Japan Exchange Group, put it: “The Japanese market is finally facing the time for changing.” He pointed to an economy slowly emerging from a two-decade deflation trap and to companies expecting record profits for the business year through March, helped in part by a weaker yen. His larger point was about attention: more domestic and overseas investors were once again looking at Japan as a place where growth might actually happen.

Still, this is an unfinished revolution. Japan’s demographic headwinds remain daunting. Corporate culture doesn’t rewrite itself on a timetable. And in many companies, reform has improved the form of governance faster than the substance—boards may look more independent on paper without a corresponding leap in strategic urgency or capital allocation discipline.

For long-term investors, JPX offers something rare: exposure to the transformation itself. The exchange is, in a sense, a wager on a feedback loop—better governance attracts capital, capital raises expectations, expectations force performance, and performance supports higher valuations. That’s the bull case.

The bear case is that Japan has teased investors before. Optimism surges, narratives catch fire, and then inertia returns. Governance reform may not be enough to overpower the country’s structural constraints. And JPX, as a business, still operates in an industry facing its own pressures, from alternative trading venues to the slow reshaping of markets by passive investing.

What JPX’s story ultimately proves is that exchanges aren’t just pipes. They’re rule-setters, referees, and—when they choose to be—architects of corporate behavior. The only remaining question is whether JPX has built a new foundation for Japan’s capital markets, or whether it simply benefited from a favorable wind. The next decade will be the verdict.

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music