Daiwa Securities Group: Japan's Eternal Challenger in the Shadow of Nomura

I. Introduction: The Strategic Question of Being Second

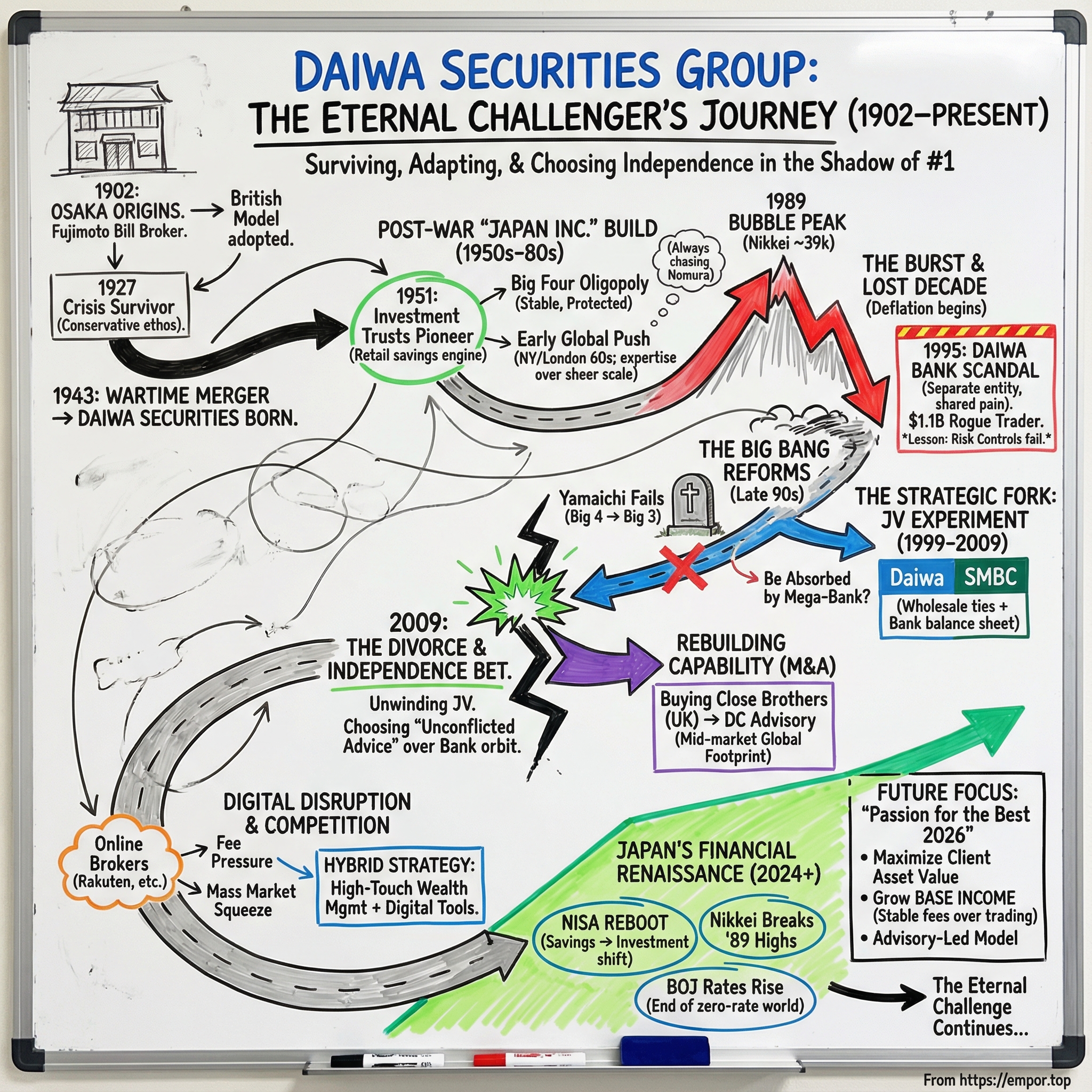

In early February 2024, Japan’s Nikkei 225 finally did the thing it hadn’t done since the peak of the bubble: it broke above its 1989 all-time high. On the Tokyo Stock Exchange, the index pushed past the old record and into new territory—less as a victory lap for the market, and more as a signal flare. After decades defined by stagnation and deflation, Japan was starting to look like a country returning to normal capitalist physics: inflation that wasn’t always zero, interest rates that actually existed, and households and companies reconsidering what to do with all that idle cash.

For Daiwa Securities Group—Japan’s eternal second-largest securities house—that moment sharpened a question the firm has been living with for more than a century:

Can you build a durable, valuable franchise while permanently living in the shadow of a larger rival?

Daiwa is, and has long been, number two behind Nomura. That rank isn’t just trivia. It’s shaped Daiwa’s strategy, its culture, and its options in every era—especially when the rules of Japanese finance have changed. And yet Daiwa hasn’t followed the familiar script for second-place companies. It didn’t disappear. It didn’t get absorbed. Instead, it built a distinct identity—rooted in independence, a relatively international posture for a Japanese broker, and a particular way of managing client relationships.

Today, Daiwa is a full-service securities group spanning Wealth Management, Asset Management, and Global Markets & Investment Banking. It serves clients through a large domestic footprint—182 branches and sales offices across Japan—while also operating internationally through hubs like New York, London, and Hong Kong.

What makes Daiwa’s story compelling isn’t that it finally toppled the leader. It’s that, at each major inflection point, it kept making deliberate choices about what kind of firm it wanted to be. When Japan’s financial system deregulated in the late 1990s, Daiwa didn’t merge into a bank. It formed a joint venture with Sumitomo Bank to compete in wholesale markets. When that partnership unraveled in 2009, Daiwa didn’t retreat into the arms of a mega-bank either—it chose to stand on its own. And when online brokers started squeezing traditional retail brokerage economics, Daiwa didn’t try to win a race to the bottom on fees. It leaned harder into advice-led, high-touch wealth management.

FY2024 captured the stakes of those choices. The year was defined by geopolitical uncertainty and political change, but also by a turning point at home: Japan breaking from its long deflationary spell and moving toward what policymakers were calling “a world with interest rates.” A revamped NISA program helped accelerate the national push from savings to investing, while corporate Japan faced growing pressure to improve capital efficiency. Even with market volatility through the year, the Nikkei hit a record high in July. And the Bank of Japan lifted policy rates to their highest level in 17 years—another sign that the ground under Japan’s financial system was shifting.

So this is the story we’re going to tell: how a bill broker founded in Osaka in 1902 navigated war, deregulation, bubbles, scandals, and systemic crises—and still emerged as Japan’s second-largest securities firm. More importantly, it’s what Daiwa’s defining decisions reveal about building something enduring in a mature industry where being number one was never the most realistic outcome.

II. The Origins: Fujimoto Bill Broker and Japan's Early Financial Markets (1902-1943)

Picture Osaka in 1902—Japan’s commercial engine room. This was a city that had traded rice futures long before the word “derivative” became global finance vocabulary, and where the habits of merchants mattered as much as government policy. It’s here that Seibei Fujimoto entered the bill-brokering business, at a time when Japan’s securities markets were still finding their shape.

Fujimoto’s idea was simple, but ambitious: build a modern intermediary that could move money efficiently between financial institutions and the growing universe of Japanese businesses. Daiwa’s lineage traces back to this moment—the founding of Fujimoto Bill Broker in Osaka—structured as a comprehensive, British-style bill brokerage.

The British influence wasn’t a flourish. It was the point. Japan was modernizing fast, and London was the model of what a sophisticated financial center looked like. Fujimoto wasn’t just trying to be a local middleman. He was trying to import a system: an institution that could procure funds in the call market, trade bills on its own account, and steadily become part of the country’s financial plumbing.

The business expanded quickly. In 1907, Fujimoto pushed into banking and renamed the company Fujimoto Bill Broker and Bank. At the time, that wasn’t a wild pivot—it was a logical extension. The lines between banking and securities were still blurry, and offering both lending and market services strengthened client relationships and widened the firm’s role in the economy.

Then World War I hit, and Japan’s economy surged. Exports boomed, corporate financing needs grew, and stock trading accelerated alongside new corporate and government bond issuance. The Fujimoto organization grew with it.

Through the 1920s, it kept operating on both sides of the house—banking and securities brokering—as Japan’s capital markets deepened and activity climbed. But the same decade delivered a harsh reminder that fast growth and fragile finance often travel together. In 1927, a run on the banks rippled through the system. Dozens of banks and securities dealers failed. Fujimoto didn’t—thanks to prudent management.

That survival mattered. It set a pattern that would echo through Daiwa’s later history: in periods when competitors overreached, the franchise endured by staying conservative enough to live through the panic.

The next shock came from abroad. After the 1929 New York stock market collapse, Japan tightened rules around financial institutions. Fujimoto was compelled to exit banking, and in 1933 the firm reorganized as Fujimoto Bill Broker & Securities Company to comply with the new regulatory regime.

It was, in effect, a forced separation of banking and securities—an early version of a debate every financial system eventually has to confront. For Fujimoto, it wasn’t a strategic choice yet. But it pushed the organization toward an identity as a securities-focused firm, an identity Daiwa would later defend by choice rather than necessity.

By 1941, Japan was at war. The wartime economy initially provided support, but by 1943, as Japan’s military fortunes began to turn, markets responded brutally—stock prices fell sharply. In that environment, Fujimoto Bill Broker & Securities Company made a survival move: combine with another institution.

On December 27, 1943, it merged with Nippon Trust Bank to form Daiwa Securities Company.

It was a pragmatic wartime consolidation. But it also created the corporate nucleus that would persist for decades. Daiwa Securities was born.

III. The Post-War Rebuild and Rise of Japan Inc. (1945-1980s)

Japan’s surrender didn’t just end a war. It turned the lights off on the securities business overnight. The occupation authorities suspended exchange trading, and Daiwa was left staring at an uncomfortable question: what is a brokerage when there’s nothing to broker?

Daiwa’s answer was to keep moving anyway. With the exchanges closed, it traded securities tied to non-defense industries over the counter from its own offices. It was a workaround, not a growth strategy—but it kept the client relationship alive until 1949, when exchange trading finally reopened.

That instinct—to find a way to operate inside the constraints of the moment—became one of Daiwa’s defining traits.

The formal rebuild started fast. In 1948, Daiwa registered as a securities firm under the newly enacted Securities and Exchange Law, the postwar framework that rebuilt Japan’s capital markets and laid out who could do what. A year later, Daiwa regained its seat at the table, joining the Tokyo, Osaka, and Nagoya Stock Exchanges.

Then Japan’s economy took off—and Daiwa went with it.

This was the era that later got branded “Japan Inc.” Export-led growth demanded capital, and capital demanded intermediaries. Securities firms became central infrastructure: raising money, distributing bonds and equities, and channeling savings into the industrial machine.

In 1951, Daiwa made a move that would matter for decades: it entered the investment trust business. It secured an investment trust management license, offered unit trusts, and by 1952 rolled out Japan’s first open-ended investment trusts.

That wasn’t just product innovation. It was a bet on behavior. Japan didn’t have a comprehensive social safety net, so households saved heavily and employers ran conservative pension and insurance programs. Investment trusts gave those mountains of savings a route into markets—and gave Daiwa a growth engine beyond pure brokerage.

By December 1959, Daiwa formalized that direction, spinning off its asset management arm and founding Daiwa Asset Management Co., Ltd. under Japan’s Investment Trust Law.

As the industry matured, it congealed into an oligopoly. Nomura, Daiwa, Nikko, and Yamaichi became the “Big Four,” dominating underwriting, bond business, secondary trading, and industry profits. It was a protected, relationship-driven ecosystem—stable and lucrative, with limited foreign competition and a regulatory environment that rewarded incumbency.

But even inside that comfortable structure, Daiwa kept reaching outward.

The 1960s were its first serious international push. With competition intensifying at home, Daiwa began underwriting Japanese companies listing overseas, opened a London office, and set up a New York subsidiary in 1964. By 1966, it had become the first Japanese securities firm with a presence in the United States.

A few tailwinds helped. Japanese capital market liberalization in 1967 made it easier to attract foreign investors. And in 1969, Daiwa launched a nationwide online operation system—an early signal that it was willing to modernize how it ran the machine.

The global build-out continued into the early 1970s. Daiwa established new entities in Hong Kong, Singapore, and Paris, along with Daiwa Europe N.V., steadily assembling the footprint of a firm that expected Japanese capital to circulate internationally.

It also started racking up firsts. In 1971, Daiwa led the world’s first Asian dollar bond. In 1977, it issued the first Euro/Yen bond. This wasn’t just about planting flags—it was about getting reps in cross-border markets, building institutional relationships, and developing fluency in the products and structures that would define global finance in the decades ahead.

That international orientation became one of Daiwa’s key differences inside the Big Four. Where Nomura often pushed globally through scale and force, Daiwa leaned into expertise—cross-border execution, institutional client ties, and a more outward-facing posture than many Japanese peers.

And then, in 1986, Daiwa did something that looks almost out of place for the era: it introduced Japan’s first personal computer-based home-trading services.

It wouldn’t be until much later that online trading became mainstream. But the point is that Daiwa was already experimenting with new distribution long before it was fashionable—another small example of the firm’s habit of adapting early, even from second place.

IV. The Bubble Years and Global Ambition (1980s-1990)

The 1980s were the high-water mark of Japanese financial power. The Nikkei 225 just kept climbing—until December 1989, when it peaked at 38,915.87, a level it wouldn’t beat for the next thirty-four years. In that atmosphere, Japan’s big securities houses felt unstoppable. They were flush with capital, backed by the momentum of “Japan Inc.,” and increasingly convinced they belonged in every major financial center on earth.

Daiwa rode that wave, but it didn’t ride it the same way as Nomura.

Nomura went at Wall Street with the subtlety of a military campaign: scale, presence, and a lot of force. Daiwa’s posture was different. It leaned into what it was already good at—serving institutions, building durable relationships, and developing deep competence in specific parts of the market rather than trying to be everything to everyone.

Those cultural differences mattered more than they might sound. In market after market, Daiwa built a reputation for being easier to work with—more willing to adapt to local norms, more collaborative, and more focused on execution and expertise than on domination by volume.

By 1990, that approach had translated into a real international footprint. Daiwa had a presence on seven European stock exchanges, and a network of offices stretching from Los Angeles to Singapore. This wasn’t just flag-planting. The goal was practical: help Japanese institutional investors deploy capital overseas, and help foreign institutions navigate Japan.

One milestone in that build-out came in 1986, when Daiwa was designated a primary dealer in U.S. government securities.

That status carried real weight. It meant Daiwa could trade directly with the Federal Reserve in the deepest bond market in the world—official recognition that it had become part of the American financial system’s institutional fabric.

But the bubble years had a way of turning growth into camouflage. The global offices, bigger trading desks, and increasingly complex operations made the machine harder to control—and risk management wasn’t keeping pace. In a market that only seemed to go up, those cracks were easy to ignore. Commissions swelled with rising volumes. Underwriting boomed as companies issued equity into euphoric valuations. Almost any strategy looked like genius.

And almost no one wanted to ask the obvious question: what happens when the music stops?

V. The 1995 Scandal: A Rogue Trader, $1.1 Billion, and Institutional Accountability

Before we go any further, one important clarification: the infamous 1995 scandal happened at Daiwa Bank Ltd., not Daiwa Securities Group. They shared a name, and the fallout splashed across Japanese finance, but they were separate entities. Still, the episode became a case study in how global expansion can outrun controls—and how institutional instincts can make a bad situation far worse.

In the summer of 1995, Daiwa Bank’s headquarters in Osaka received a long, handwritten confession. It came from Toshihide Isamu Iguchi (1951–2019), an executive vice president at the bank’s New York branch and a trader in U.S. government bonds. In that letter—sent on July 17—Iguchi admitted he had been hiding massive losses from unauthorized trading. The total: $1.1 billion, accumulated over twelve years, starting in 1983.

The origin story was painfully small. In 1983, Iguchi lost $70,000 trading Federal Reserve Notes. He covered it up to protect his reputation and his job, then kept trading to try to win it back. Instead, the losses snowballed.

At the same time, the New York branch was booming. Japanese money was pouring into U.S. securities, and Daiwa’s securities custody department grew into the branch’s biggest unit. Iguchi’s area was reportedly generating more than half of the branch’s profits. In other words: the business line at the center of the story looked like a star—exactly the kind of place where uncomfortable questions don’t get asked.

By July 1989, the bet sizes had become enormous. Iguchi and two junior traders made a $3 billion wager on U.S. Treasury bonds—and lost $350 million. A whistleblower tipped off regulators, and the New York Fed sent an examiner to inspect Daiwa’s bond trading operation. They found nothing.

That failure wasn’t because the losses weren’t there. It was because the concealment was. When examiners came again in 1992, Daiwa went further—hiding the trading operation in its downtown office by relocating the bond traders to the main midtown branch during the examination. In 1993, on advice of counsel, Daiwa voluntarily confessed that it had misled the Fed and insisted there was no deeper problem. The Fed investigated for two weeks, still found nothing abnormal, and—after months of deliberation in Washington—issued a formal reprimand for the deception.

Then came the 1995 confession letter, and with it, a second scandal layered on top of the first: what leadership did next.

Daiwa officials in Japan acknowledged receiving Iguchi’s letter. Two days later, the bank proceeded with a previously planned $500 million preferred stock issuance. And the day after that issuance, senior management told Iguchi to keep hiding the losses until November. On July 31, the New York branch submitted financial statements to the Federal Reserve that did not disclose the losses. Daiwa also failed to notify U.S. federal or New York state banking authorities that a possible crime had occurred—something both federal and state law required. It wasn’t until August 8 that Daiwa informed Japan’s Ministry of Finance.

This all unfolded against an ugly backdrop: Japan was already deep in a post-bubble banking crisis—the worst since the Great Depression. But Daiwa’s U.S. lawyers pressed hard for disclosure. On September 18, without Iguchi’s knowledge, Daiwa finally reported the loss to U.S. regulators and submitted a criminal referral on him, attaching his confession letter. Iguchi—kept in the dark—was still working around the clock trying to verify the damage when he was arrested at his home in New Jersey.

The consequences were brutal. In September 1995, Iguchi was arrested. Daiwa was fined $340 million by U.S. regulators and forced to shut down its New York operations. In 1996, Iguchi was sentenced to four years in prison and ordered to pay $2.6 million in fines and restitution. Between 1983 and 1995, he had hidden $1.1 billion in losses.

The scandal landed the same year Nick Leeson’s rogue trading brought down Barings Bank. Iguchi never became as famous, but in the history of financial blowups, he sits in the same grim category: a “pioneer” case that revealed how catastrophic things get when one person can both take risk and control the paperwork that proves whether the risk exists.

And for Japanese finance, the real lesson wasn’t just one trader. It was the system around him: a culture that leaned toward face-saving, internal controls that allowed a single individual to blur trading and settlement responsibilities, and fragmented oversight between Japan and the U.S.

After Daiwa and Barings, the industry’s takeaway hardened into doctrine. You separate front office from back office. You enforce independent checks. You assume that even trusted employees, inside respected institutions, can cause ruin if basic controls are missing.

VI. Japan's Lost Decade and the Big Bang Reforms (1990s)

When Japan’s asset bubble burst, it didn’t just trigger a normal recession. It set off what became one of the longest and most grinding financial crises any developed economy had faced since the Great Depression. Stock prices collapsed. Real estate values cratered. Banks—stuffed with loans backed by property that was suddenly worth a fraction of what it had been—started to wobble, and then to fail.

For the securities industry, this wasn’t a down cycle. It was an extinction event. The old system—a cozy, protected oligopoly that had showered profits on the Big Four for decades—was about to be pried open, and not gently.

In November 1996, Prime Minister Ryutaro Hashimoto reached for a deliberately provocative comparison. Borrowing the language of London’s 1980s deregulation, he called for a Japanese “Big Bang”: a sweeping overhaul of the country’s financial markets, to be completed by 2001. Japan had announced reforms before, with uneven results. But the ambition this time was unmistakable.

The “Japanese Big Bang” kicked off under three principles—“free, fair and global”—with the explicit goal of rebuilding Japan into an international financial market on par with New York and London.

At the center of the plan was a structural shift: legalizing financial holding companies that could own banks, insurers, and securities firms, subject to certain restrictions. The postwar walls between different types of finance—barriers originally imposed under U.S.-influenced reforms after World War II—would start coming down. In theory, consumers would get something closer to the European “universal bank” model: one-stop financial shopping, with integrated services under one roof.

In practice, the timing was brutal. Japan was trying to modernize its financial system at the exact moment that system was seizing up.

Then came the shock that made the crisis impossible to ignore. In November 1997, the Big Four became the Big Three. On November 24, Yamaichi Securities announced it would cease operations. It was later declared bankrupt by the Tokyo District Court on June 2, 1999.

Yamaichi wasn’t some flimsy upstart. Founded in 1897, it had been one of Japan’s four major brokerages, with a client list that included major Japanese corporations. Its collapse—driven by financial strain, scandal, and a slumping Tokyo market—became the largest corporate failure in Japan since the end of World War II.

Investigators later found that Yamaichi had concealed enormous losses—more than 260 billion yen, roughly $2.1 billion at the time. The firm was projected to leave behind roughly 3 trillion yen in unresolved debts, and reports put group-wide liabilities even higher.

And Yamaichi didn’t fall in isolation. That same month, a series of failures ripped through Japanese finance—Sanyō Securities, Hokkaidō Takushoku Bank, and then Yamaichi—followed almost immediately by runs on banks. The crisis stopped being theoretical. It was now happening in public, at scale.

For Daiwa, Yamaichi’s demise landed as both warning and opportunity. The warning was obvious: even century-old franchises with deep institutional relationships could disappear. The opportunity was just as clear: when a firm like Yamaichi vanishes, its clients don’t vanish with it. They need a new home, and quickly.

Daiwa’s response was to reorganize itself for a world where the old rules no longer applied. As Japan’s financial sector restructured and deregulated through the 1990s, Daiwa moved toward a holding company model—creating a structure that could compete in a more open market, partner where it needed to, and separate businesses that now faced very different economics.

The pivotal step came in April 1999. Daiwa formed Daiwa Securities Group Inc., becoming the first listed Japanese holding company in the securities industry. Under the new setup, retail and wholesale operations were split—different strategies for different clients—while still benefiting from the same underlying brand and infrastructure.

In the middle of Japan’s financial storm, Daiwa was doing what it had done before: adapting early, not because it wanted to, but because the environment demanded it.

VII. The Strategic Fork: The SMBC Joint Venture Experiment (1999-2009)

The Big Bang reforms forced every Japanese securities firm to answer a question it could no longer dodge: do you tie yourself to a bank—or try to compete on your own?

The case for banking muscle was obvious. In Europe, universal banks had become the dominant model, combining lending, underwriting, and trading under one roof. Japan’s deregulation now made similar structures possible. Banks brought large balance sheets, deep corporate relationships, and a kind of stability that pure brokers, battered by the 1990s, increasingly lacked.

Daiwa didn’t choose absorption. It chose partnership.

In April 1999, Daiwa created a wholesale joint venture with Sumitomo Bank: Daiwa Securities SB Capital Markets. The mandate was clear—go after Japan’s wholesale securities markets, and do it with a banking partner’s distribution and lending relationships close at hand. Later that year, as Daiwa reorganized into a holding company structure, most of its overseas subsidiaries were transferred into the joint venture, with the U.S. subsidiary as the lone exception.

Then the banking side changed shape. In April 2001, Sumitomo Bank merged with Sakura Bank to form Sumitomo Mitsui Banking Corporation. Along with that merger came assets and capabilities that strengthened the joint venture: Daiwa Securities SB Capital Markets took on Sakura Securities’ assets and absorbed parts of Sakura Bank’s investment banking business, including M&A. It was then renamed Daiwa Securities SMBC.

The pitch to clients was simple and powerful. A company could get underwriting through the Daiwa platform and lending through SMBC—without having to coordinate between two separate institutions. One relationship, two balance sheets, and a cleaner path from financing to capital markets execution.

Ownership reflected the compromise. Daiwa Securities SMBC was 60% owned by Daiwa Securities Group, with SMBC as the partner, and it operated across Japan and overseas as Daiwa’s wholesale engine. It built strength in institutional equity and bond trading, bond underwriting, and IPOs. It led IPO listings in three emerging equity markets, became a market leader in structured finance and derivatives, expanded into principal finance and M&A, and established itself as a first-tier player in equity underwriting.

For much of the 2000s, it looked like Daiwa had threaded the needle. The joint venture let it compete in wholesale markets with a bank at its side—without surrendering the independence that defined Daiwa’s identity.

But joint ventures come with their own price. Strategy has to be negotiated. Governance requires constant alignment. Capital decisions get messy when two parents want different things from the same business. And when the world shifts—as it inevitably does in finance—the logic that made the partnership feel elegant in year one can start to feel restrictive by year ten.

VIII. The 2009 Divorce: Choosing Independence

The 2008 global financial crisis forced a reckoning across the industry. For the Daiwa–SMBC joint venture, it also forced a decision. The partnership had always required constant alignment between two parents with different instincts—and after Lehman, those differences stopped being manageable.

In September 2009, Sumitomo Mitsui Financial Group and Daiwa Securities Group announced they would dissolve the joint venture as of December 31, 2009—an outcome, they said, of failed efforts to reconcile “differences in basic concepts concerning the management policies of the venture.”

That’s the kind of phrase that reads like it came from a committee because it did. But the underlying reality was straightforward: SMFG, a mega-bank trying to secure its footing in a post-crisis world, wanted tighter control over its securities capabilities. Daiwa wanted to protect its independence and run its wholesale business without a bank partner second-guessing priorities.

The structure unwound accordingly. SMFG agreed to sell its entire interest in Daiwa Securities SMBC to Daiwa Securities Group on December 31, 2009. With that stock transfer, the joint venture would cease to exist.

Operationally, the divorce played out over the following months. The dissolution was announced in 2009 and took effect in 2010, allowing Daiwa to regain full ownership and reorient the wholesale platform back under Daiwa’s control. Daiwa re-acquired 100% of the shares, renamed the entity Daiwa Securities Capital Markets Co. Ltd., and then—about two years later—absorbed it in a merger, leaving Daiwa Securities Co. Ltd. as the sole surviving entity.

To see what Daiwa was refusing, look at what happened next door.

In October 2009, Nikko Cordial Securities became a wholly owned subsidiary of SMBC. In April 2011, it was renamed SMBC Nikko Securities Inc. The reasoning was explicit: keep the “Nikko” name because it still carried the weight of a former Big Four brand, use that brand to motivate employees from the legacy organization, and signal—domestically and internationally—that the securities arm was now fully integrated into the SMBC Group’s universal banking model.

SMFG wanted securities capabilities, and it got them through Nikko. The fact that it chose that route rather than rework the Daiwa relationship said a lot: whatever the joint venture had been in 1999, by 2009 the strategic tensions were no longer fixable.

For Daiwa, this was the defining bet. In an era when mega-banks were pulling brokers into their orbit, Daiwa chose to stand alone. Its independence thesis was that a pure-play securities firm could outperform a bank-owned broker by staying focused, moving faster without cross-parent coordination, and maintaining client trust by avoiding the conflicts that can come with being tied to a lender.

It was a bold call—especially for Japan’s eternal number two. But it was also consistent with Daiwa’s long-running pattern: when the industry’s default answer was consolidation, Daiwa tried to make “independence” a strategy, not a slogan.

IX. Building the Modern Platform: M&A, Close Brothers, and Global Reach (2009-2015)

Independence solved one problem for Daiwa—control. But it created another: capability. If the firm wasn’t going to lean on a mega-bank’s balance sheet and investment banking machine, it needed to build pieces of that machine itself. And in the years around the joint venture’s unwind, Daiwa started doing exactly that—selectively, through acquisition, with a clear emphasis on where a Japanese firm could win globally.

The most consequential move was in Europe.

In 2009, Daiwa Securities SMBC acquired Close Brothers Corporate Finance, the corporate finance division of Britain’s Close Brothers Group, for £75 million. The logic was simple: buy an already-working M&A advisory franchise, with local relationships and credibility, and plug it into Daiwa’s platform. The deal brought in a team of more than 100 mid-market professionals and gave Daiwa an immediate foothold in cross-border advisory work where execution and trust mattered at least as much as brand.

By July 2010, the business was rebranded as DC Advisory Partners—Daiwa’s dedicated M&A advisory arm, focused on Europe and North America.

Close Brothers Corporate Finance wasn’t a greenfield operation. Before Daiwa bought it in July 2009, it had already been building scale and reach: strengthening its UK business by acquiring corporate finance teams from Hill Samuel and Rea Brothers, and expanding across continental Europe through acquisitions in France, Germany, and Spain. Daiwa wasn’t just buying headcount. It was buying a network.

That choice reflected a very specific bet about where Daiwa could compete. Large-cap, marquee investment banking was a knife fight against the biggest Wall Street and European firms. Mid-market advisory was different. Relationships were stickier, industry specialization mattered more, and a focused team could win without having the largest balance sheet in the room.

Over time, DC Advisory grew into a sizable global platform. As of April 2023, it had more than 700 employees and 22 offices across Europe, the United States, and Asia. It remained owned by Daiwa Securities Group Inc.—a parent whose roots, as we’ve seen, go back to 1902.

And Daiwa kept adding to it.

DC Advisory expanded its mainland Europe footprint with the acquisition of an independent Spanish investment bank, Montalbán. In the U.S., Daiwa acquired boutique investment banks Sagent Advisors and Signal Hill, then merged them to deepen its American presence.

The combined U.S. business was positioned to operate as a single firm—DCS—focused on M&A advice and private capital raising for growth-economy companies, with operations across eight U.S. offices including Baltimore, Boston, Chicago, Nashville, New York, Northern Virginia, and San Francisco. Daiwa’s president and CEO, Seiji Nakata, framed the intent clearly: expanding the group’s M&A advisory business was a core strategic priority.

Taken together, these moves weren’t about trying to out-bully the bulge bracket. They were about building a different kind of global investment banking capability—mid-market, locally rooted, and sector-driven—designed to travel well even for a firm that chose to remain Japan’s independent challenger.

X. Japan's Financial Renaissance: NISA, Abenomics, and the End of Deflation (2012-Present)

After three decades defined by deflation and low growth, Japan entered 2024 at something close to a structural turning point. You could see it in the places that matter for a securities firm: how households saved, how markets valued risk, how companies were pressured to use capital more efficiently, and—most importantly—how monetary policy began to normalize after years of emergency-mode settings.

The catalyst for ordinary households was a very specific piece of plumbing: NISA, Japan’s tax-advantaged investment account, modeled on Britain’s ISA system. And in January 2024, Japan rebooted it.

The new NISA made the program more compelling in the ways that actually change behavior. It was made permanent. The tax-free holding period became indefinite. And the annual investment limits were increased—turning NISA from a “nice to have” perk into a mainstream channel for long-term investing.

Prime Minister Fumio Kishida’s “new form of capitalism” put NISA at the center of a national effort to move Japan from savings to investment. As of September 2023, Japanese households held roughly 2,100 trillion yen in assets, with about half sitting in cash. The government’s ambition was correspondingly large: grow NISA participation and meaningfully increase the amount invested through the program over a five-year period.

Mechanically, the 2024 reforms raised how much individuals could invest each year across the two main NISA categories, removed the old time limits on tax exemption, and allowed individuals to build up a large lifetime balance under the program while keeping gains permanently tax-free.

The market response was fast. In 2024, mutual fund assets in Japan surged year-on-year as retail investors shifted money out of low-yield bank deposits and into NISA-backed products, including broad index funds. A rising market helped too: the Nikkei’s rally pulled more households off the sidelines, and net inflows into mutual funds jumped sharply compared with 2023.

For Daiwa, this was both tailwind and threat. The tailwind was obvious: if Japan was finally going to put household money to work, that meant more assets to manage, more wealth management revenue, and more investing activity across the board. The threat was just as clear: the biggest wave of new NISA accounts was being captured by online brokers, not the traditional full-service branch networks.

Daiwa still had to play the hand it was dealt. It invested in system development to keep pace with Japan’s market structure reforms and to support the operational demands created by the new NISA launch in January 2024.

Meanwhile, the stock market made the shift feel real—not just theoretical. On February 22, 2024, the Nikkei hit an intraday high above 39,000 and closed above its previous record, finally clearing the 1989 peak. Days later, on March 4, it broke through 40,000 for the first time. And by July, the index pushed into the 42,000s, setting fresh records again.

Then monetary policy added the final piece of the “new Japan” narrative. In 2024, the Bank of Japan raised rates for the first time in 17 years, ending its negative interest rate policy after inflation held above roughly 2%. The BOJ moved its benchmark into a range of 0 to 0.1% from minus 0.1%, and Governor Kazuo Ueda said the ultra-loose measures had “fulfilled their roles.”

For Japanese finance, this was more than a quarter-point headline. It was a regime change. And for firms like Daiwa, it meant the next era wouldn’t be about surviving stagnation—it would be about competing for a newly mobilized household balance sheet in a country that, at long last, had rediscovered what it looks like when money has a price.

XI. Digital Transformation and Competitive Pressures

The shift to digital trading didn’t just add a new channel. It rewired the economics of brokerage. For traditional firms like Daiwa, the pressure shows up in the simplest, most uncomfortable question: what do you charge for, when an app can do the basic transaction for close to nothing?

No company embodies that change more clearly than Rakuten Securities. It launched in 1999 as Japan’s first dedicated online brokerage, and it has spent the last two decades turning brokerage into a consumer product—built for self-directed investors, priced aggressively, and tightly integrated into the broader Rakuten ecosystem. By April 2024, Rakuten said its general securities accounts had surpassed 11 million, after adding roughly 1 million accounts in about four months. By November 2025, the company announced it had surpassed 13 million.

That growth wasn’t just marketing muscle. It was plumbing. Rakuten leaned into the “already a customer” advantage: connections between Rakuten Bank and Rakuten Securities, the ability to invest in mutual funds using a credit card, and the use of Rakuten points not just for shopping, but for investing in stocks and mutual funds. When NISA expanded the addressable audience for investing, Rakuten was positioned to catch that demand at the moment it arrived—with an interface and a bundle that felt familiar to millions of consumers.

Zoom out, and the pattern is even clearer. Online brokers like Rakuten Securities and SBI Securities have been growing at a pace traditional firms struggle to match. They win on cost, convenience, and scale—and they bring ecosystem advantages that a standalone securities house simply can’t copy overnight.

Daiwa’s answer has been to go hybrid: keep the branch network for relationships that actually benefit from humans, and invest in digital capabilities so the firm isn’t fighting the last war. It’s a delicate balancing act. Daiwa still operates 182 branches and sales offices across Japan, and it has 3,209 thousand customer accounts with balance—evidence that the legacy model still has real reach, even as the market shifts under it.

Digitally, Daiwa has elevated innovation into a core pillar of its “Passion for the Best” 2026 Medium-Term Management Plan. The stated intent is to use technology to strengthen existing businesses and push forward digital strategies, including the use of AI, Web 3.0, and other leading-edge tools.

The logic is sound: online brokers can win the commodity trade—simple, low-cost transactions. But high-net-worth households and corporate clients still need advice, structuring, and judgment, especially as Japan moves deeper into a world where rates exist again and portfolio choices actually matter. The open question is the one that defines Daiwa’s next chapter: is that high-touch segment large enough, and valuable enough, to support a major franchise while the mass market migrates to apps?

XII. The 2024-2026 Strategy: Passion for the Best

That’s the backdrop Daiwa walked into as it kicked off its next act: the “Passion for the Best” 2026 Medium-term Management Plan—built around a simple organizing idea: “maximizing the value of customer assets.”

Daiwa Securities Group Inc. released “Passion for the Best” 2026 as a three-year plan covering FY2024 through FY2026. The plan is framed as a backcasting exercise from the Group’s FY2030 vision: build a solid earnings foundation that can hold up even when markets and the outside environment turn hostile.

The core promise is advisory-led. “Maximizing the value of customer assets” isn’t positioned as a slogan; it’s the basic management policy. The plan says the Group’s activities should compound client asset value over the medium to long term through high-quality consulting and solutions—grounded in accurate analysis of market conditions and a deep understanding of what clients actually need.

Early returns gave Daiwa something it hadn’t had in a while: momentum. In FY2024, consolidated ordinary income surpassed ¥200 billion for the first time in 19 years, reaching ¥224.7 billion. ROE came in at 9.8%, which the company highlighted as exceeding the cost of capital the market was assuming—estimated around 8–9%.

In the same year, Daiwa posted ¥645.9 billion in net operating revenues and ¥154.3 billion in profit attributable to owners of the parent.

But the ambition here isn’t one good year. The longer arc is FY2030: Daiwa is targeting ordinary income of more than ¥350 billion, with an earnings structure designed to be resilient to external swings. The way it plans to get there is diversification by design—no single division carrying the whole franchise. Each segment is expected to grow its own profits, while the Group also pursues inorganic growth to help sustain higher ROE.

Within the FY2026 plan itself, Daiwa set targets of consolidated ordinary income of at least ¥240 billion and ROE of around 10%. A key concept is “base income,” meant to provide stability through cycles, with a target of at least ¥150 billion.

By Daiwa’s telling, FY2024 showed the shape of what it wants more of. Base income rose more than 20% year-on-year to ¥137.5 billion. The Wealth Management Division saw ordinary income increase 21.8%, and net asset inflows hit a record ¥1.57 trillion—up 89.3% year-on-year.

Just as importantly, Daiwa pointed to platform-building moves alongside the financial results. Base income grew faster than expected, and the firm advanced what it calls a “discontinuous growth” strategy through capital and business alliances with external partners, including Aozora Bank, Ltd. and The Japan Post Insurance Company, Ltd.—steps it described as meaningful progress toward expanding the Group’s business platform.

XIII. Bull Case, Bear Case, and Competitive Analysis

The Bull Case

Japan’s move from decades of deflation toward a more “normal” world of inflation and interest rates creates a rare opening for securities firms. The national push from savings to investment isn’t just a slogan—it’s being reinforced by policy and regulation, and it arrives at a moment when a younger cohort of investors, with less lived memory of the bubble’s psychological scars, is more willing to own equities.

In that context, Daiwa’s defining choice—staying independent—can start to look like a feature, not a handicap. Bank-affiliated brokers always carry an extra layer of complexity: advisory recommendations can be viewed through the lens of lending relationships and group priorities. Daiwa can credibly position itself as the unconflicted advisor. As corporate governance scrutiny rises and boards face more pressure to justify capital allocation, “clean” advice has real value.

There’s also evidence that Daiwa’s wealth management pivot is taking hold. As more of the business shifts toward asset-based revenue, the firm becomes less reliant on the mood swings of trading volume and commission cycles. And by leaning into higher-net-worth clients—where planning, structure, and trust matter as much as execution—Daiwa is competing in a segment that online brokers can’t easily commoditize.

Finally, the global build-out through DC Advisory gives Daiwa a second growth engine. A stronger M&A advisory platform diversifies the revenue mix and positions the group to benefit if Japanese companies continue to push outward through cross-border deals as part of broader consolidation and globalization strategies.

The Bear Case

The uncomfortable truth is that online brokers are steadily consuming the mass retail business. Rakuten’s scale is the headline: about 13 million accounts versus Daiwa’s roughly 3.2 million customer accounts with balance. In the self-directed world, price competition has pushed basic brokerage toward zero, and that dynamic doesn’t reverse. Meanwhile, Daiwa’s high-touch model carries real fixed costs—branches, staffing, and legacy infrastructure—that get harder to justify if more clients decide they’re fine with an app.

Japan’s demographics add another ceiling. A shrinking, aging population means fewer new savers over time and slower organic growth in the domestic market. NISA can accelerate the redeployment of existing cash into markets, but it can’t rewrite the underlying demographic math.

And independence cuts both ways. Avoiding absorption by a mega-bank preserved Daiwa’s autonomy, but it also means Daiwa doesn’t have the same balance-sheet backing or lending-led corporate access that integrated rivals can bring to bear. In capital-intensive businesses—trading, financing, principal risk—scale and balance sheet can matter, especially when markets seize up.

Porter’s Five Forces Analysis

Threat of New Entrants: Moderate to high. Technology has proven it can unbundle distribution and capture share. Licensing and compliance still create friction, but online-first players have shown the barriers aren’t prohibitive.

Supplier Power: Low. Talent is the key input, and top performers do command premium pay, but the market for finance professionals is broad enough that no single supplier group has outsized leverage.

Buyer Power: High and rising. Retail clients can switch in minutes. Institutions can play providers against each other and negotiate hard, especially when many offerings look similar.

Threat of Substitutes: High. Index funds reduce the need for active management. Robo-advice reduces the need for human-led basic portfolio construction. And with roughly half of household assets still sitting in cash and deposits, the default “substitute” for investing remains doing nothing.

Competitive Rivalry: Intense. Nomura is the heavyweight. Bank-owned securities firms can subsidize and bundle. Online brokers compete aggressively on price. Foreign firms selectively attack premium segments where margins still exist.

Hamilton Helmer’s 7 Powers Analysis

Scale Economies: Limited. There are efficiencies in technology and market infrastructure, but high variable costs and the expense of a physical footprint cap the advantage.

Network Effects: Minimal. Brokerage doesn’t naturally get more valuable to each customer as more customers join, at least not in the way true platforms do.

Counter-Positioning: Potentially Daiwa’s strongest lever. Independence creates a genuine trade-off: bank-affiliated competitors can’t fully lean into “unconflicted advice” without raising questions about their integrated model.

Switching Costs: Low for simple trading, higher for complex wealth relationships where trust, history, and embedded planning create real friction.

Branding: Moderate. Daiwa’s brand carries weight with institutions and wealthy households, but matters less in the price-sensitive, self-directed retail market.

Cornered Resource: Limited. Talent is portable, and the firm doesn’t appear to have a single, exclusive asset that locks competitors out.

Process Power: Emerging. If Daiwa can consistently systematize consulting-led wealth management—making it a repeatable organizational capability rather than a handful of star advisors—that can become durable differentiation that’s harder to copy than a product or a price point.

XIV. What to Watch: Key Performance Indicators

If you’re trying to understand whether Daiwa’s strategy is actually working—not just whether it had a good quarter—there are two numbers that tell the story better than headline earnings.

1. Base Income (Asset-Based Revenue + Stable Fees)

Base income is Daiwa’s shorthand for the recurring, steadier part of the business: revenue tied to wealth management, securities asset management, and real estate asset management. In other words, it’s a proxy for how far Daiwa has moved away from being hostage to market mood swings.

In FY2024, base income came in at ¥137.5 billion, putting Daiwa within reach of its ¥150 billion target. The thing to watch isn’t whether it ticks up in a bull market—it’s whether it keeps climbing even when markets don’t cooperate.

2. Wealth Management Net Asset Inflows

This is the most direct scoreboard for Daiwa’s wealth-management pivot: is new money choosing Daiwa, especially in a world where online brokers make it effortless to open an account anywhere?

In FY2024, Daiwa reported ¥1.57 trillion in net inflows into wealth management—up 89.3% year-on-year. If that stays healthy, it’s evidence the advice-led model is winning the clients Daiwa actually wants.

Together, base income and wealth management inflows tell you whether Daiwa is building a more durable franchise—or just benefiting from a favorable market tape.

XV. Conclusion: The Value of Eternal Challenge

Daiwa Securities Group’s 123-year story is, at its core, a story about staying alive—and staying itself. It began as a bill broker in Osaka in 1902, then survived the forced contortions of wartime consolidation, rebuilt in the rubble of post-war Japan, expanded aggressively in the bubble years, and endured the industry’s broader crisis of confidence as scandals and the Lost Decade exposed how fragile “blue chip” finance could be.

Again and again, Daiwa faced moments when the obvious move was to disappear into something bigger. And again and again, it found a way to adapt without surrendering its identity.

That’s why the choice of independence—walking away from the SMBC joint venture rather than becoming the bank’s captive securities arm—stands out as the defining decision of the modern era. Daiwa was betting that focus, speed, and credibility as an unconflicted advisor would matter more than balance sheet size and the apparent synergies of universal banking. Fifteen years later, the result is complicated but undeniable: Daiwa is still standing as an independent franchise, even as pressure comes from both sides—bank-affiliated rivals with integrated distribution on one side, and fee-crushing digital brokers on the other.

Now, for the first time in a long time, the environment is helping rather than hurting. Japan’s break from deflation, the NISA-fueled push from savings to investment, a market making new highs, and the Bank of Japan’s move back toward “normal” interest rates have created the most constructive backdrop for the securities business in decades.

Whether Daiwa can turn that backdrop into durable share gains—especially in a market where the next generation of investors may never set foot in a branch—will decide if the eternal challenger becomes something more, or stays permanently in second place.

One thing is clear either way: the story isn’t over. In an industry where firms as storied as Yamaichi—and institutions as venerable as Barings—could vanish fast, mere survival is a kind of victory. Daiwa has survived. The next decade will tell us if it can do more than that.

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music