Mitsubishi HC Capital: The Silent Giant of Global Asset Finance

I. Introduction: A Giant Hiding in Plain Sight

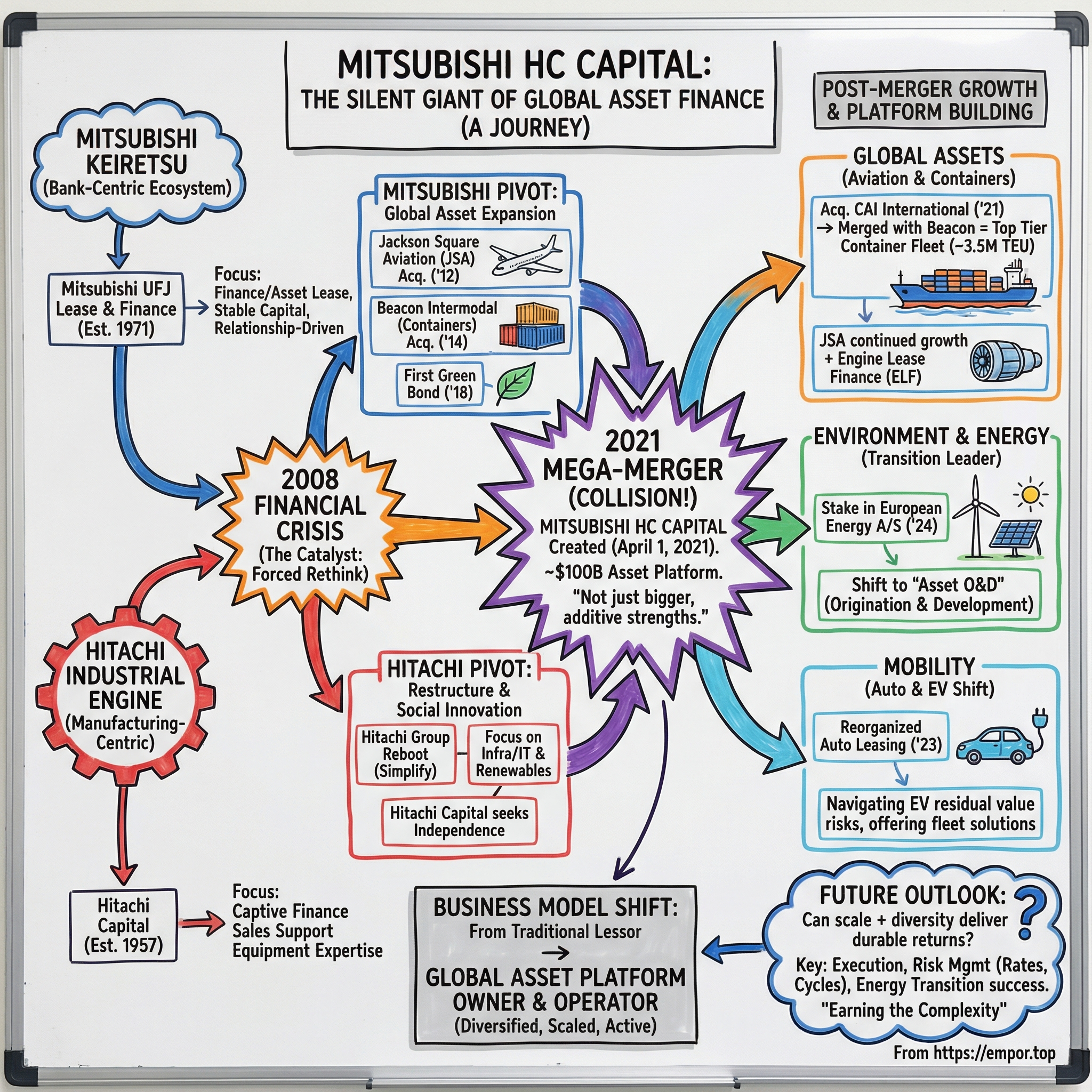

What if the world’s fourth-largest non-bank financial company was born just four years ago—created through a merger so sweeping it stitched together a roughly $100 billion asset platform almost overnight?

That’s Mitsubishi HC Capital: a company many investors outside Japan barely register, even though its assets show up in ordinary life more often than you’d expect. There’s a decent chance you’ve used something it financed without ever knowing it. Jackson Square Aviation, one of its subsidiaries, has steadily built a modern Airbus-and-Boeing portfolio; today its owned, committed, and managed fleet totals 334 aircraft serving 63 airlines across 32 countries. The container that carried your latest online order might have been part of CAI International’s global fleet—about 1.9 million container equivalent units. And the solar panels feeding clean power into grids across Europe? Those can trace back to financing and investment activity inside Mitsubishi HC Capital’s Environment & Energy business.

The business has momentum, too. For the fiscal year ended March 2025, Mitsubishi HC Capital posted net income of 135.1 billion yen—hitting the target it set at the start of the term and delivering record-high profits for the third straight year. It raised its annual dividend to 40 yen per share, extending what management describes as a 27-year streak of dividend growth. And it wasn’t done: for the fiscal year ending March 2026, the company planned net income of 160.0 billion yen and expected to lift the annual dividend by another 5 yen, to 45 yen.

But the numbers are just the scoreboard. The real story is how this company came to exist in the first place—and why its origin matters to what it can become next.

Mitsubishi HC Capital is the product of two very different strands of Japanese corporate history. One strand runs through the Mitsubishi keiretsu: the relationship-driven, institutionally powerful ecosystem that helped build modern Japanese capitalism. The other comes out of Hitachi’s industrial engine: a manufacturing giant whose finance arm was designed to move equipment out the door and money back in. Over decades, both finance businesses evolved beyond their “captive” roots—until the moment arrived to fuse them into something bigger, broader, and far more global than either could have been alone.

That’s the arc we’re going to follow: the rise of Mitsubishi UFJ Lease & Finance and Hitachi Capital; the way the 2008 financial crisis forced Japanese conglomerates to rethink what they owned and why; and the 2021 merger that, almost quietly, created a global asset-finance heavyweight. Along the way, we’ll look at the deals that scaled its container platform, the aviation leasing engine built to compete in the top tier, and the renewable energy investments that tie this once-traditional leasing company to the energy transition.

For long-term investors, the core question isn’t whether Mitsubishi HC Capital is big. It’s whether a “silent giant” like this can consistently convert scale and diversification into durable returns—and whether the uniquely Japanese structure that helped create it remains a competitive edge, or turns into friction as global competition intensifies.

II. The Mitsubishi Keiretsu & Birth of Japanese Leasing (1971–1990s)

To understand Mitsubishi HC Capital, you first have to understand the keiretsu—the distinctly Japanese operating system that shaped the company’s DNA.

A keiretsu is a business group: companies linked by long-standing commercial relationships and cross-shareholdings, usually organized around a core bank. It emerged after World War II, as Japan unwound the old zaibatsu conglomerates under the occupation. The basic idea was stability. If your biggest partners also owned small stakes in you—and you owned small stakes in them—you weren’t forced to run the company quarter-to-quarter. You could plan, invest, and ride out market swings with less fear of hostile takeovers or sudden shareholder revolts.

For decades, Japan had six major keiretsu—Mitsui, Mitsubishi, Sumitomo, Fuyo, Sanwa, and Dai-Ichi Kangyō Bank Group—often referred to as the “Big Six.” Three traced their roots back to the old zaibatsu families; the other three formed around powerful postwar banks in the 1950s and 1960s.

Mitsubishi is a classic example of what’s called a horizontal keiretsu: a broad constellation of companies spanning industries, tied together by relationships, capital, and coordination. These groups typically included a central bank, a general trading company, major insurers, and heavyweight industrial companies. In Mitsubishi’s case, the center of gravity ran through the group’s bank (today part of MUFG), Mitsubishi Corporation, and a long list of manufacturing, insurance, and service businesses that shared the three-diamond crest—and, just as importantly, shared customers and capital.

That’s the environment Mitsubishi UFJ Lease & Finance was born into. It was incorporated in April 1971, right as Japan’s postwar economic miracle was hitting full stride. Its job was straightforward: help the Mitsubishi ecosystem—and its partners—buy the equipment Japan’s growth machine demanded.

The timing mattered. Japanese industry was expanding fast, and expansion meant capex: machinery, vehicles, office equipment, industrial systems. Traditional bank lending was essential, but it wasn’t always flexible enough for what companies wanted. Leasing offered a different answer. Instead of paying upfront, customers could spread costs over time and keep cash available for operations, inventory, and growth.

Over time, that leasing platform would evolve into what later became Mitsubishi HC Capital. But the original structure already contained the blueprint. The business split into two core lanes. One was straightforward customer financing: finance leases and installment sales for machinery, equipment, and fixtures—helping companies get what they needed now and pay over time. The other was asset finance: operating leases on machinery and transportation equipment, plus investment and lending tied to real estate, securities management, and specialized finance related to assets like aircraft and ships, including office building leasing.

And being “Mitsubishi” wasn’t just branding—it was an advantage. The company benefited from steady deal flow inside the group, relationships built by the bank and trading company across Japanese industry, and the credibility that came from being attached to an institutional pillar of the economy. It also meant constraints. In a keiretsu, independence is rarely the point; priorities are shaped by the group, and entrepreneurial freedom tends to come second to alignment and stability.

By the late 1980s, the model reached its high-water mark. Cross-shareholdings had become so widespread that, at one point, more than half the value of Japan’s stock market was tied up in them. That would begin to unwind in the decades that followed, as banks reduced stakes and Japan’s corporate system slowly loosened.

But in the 1970s and 1980s, the keiretsu structure gave Mitsubishi UFJ Lease & Finance exactly what a young leasing business needed: a protected runway, access to customers, and a stable cost of capital.

For investors, that origin still matters. The Mitsubishi connection remains central to the company’s identity and competitive position—especially in funding and relationships. The twist is that today, it’s less a heritage to simply inherit and more a legacy the company has to actively manage as it competes on a far more global playing field.

III. The Hitachi Capital Story: From Electronics to Finance (1957–2000s)

The other half of Mitsubishi HC Capital’s DNA comes from a very different place. Not from a bank-centered business group, but from the workshops and engineering culture of one of Japan’s defining industrial companies: Hitachi.

Hitachi began in 1910 in Ibaraki Prefecture, founded by electrical engineer Namihei Odaira. Its first product was a 4-kilowatt induction motor built for copper mining—practical, industrial, and aimed squarely at the real economy. What started as an in-house project inside Fusanosuke Kuhara’s mining company soon stood on its own: Hitachi became independent in 1911, and by 1918 it had moved its headquarters to Tokyo. Even the name carried ambition. “Hitachi” combines the kanji for “sun” and “rise,” a word Odaira coined to capture the idea of something new powering Japan forward.

That industrial momentum created a very specific problem: big machines are hard to sell if customers can’t pay for them. So in 1957—an eye-catching year that also saw Hitachi build its first computer—Hitachi launched Hitachi Capital. The purpose was simple and strategic: make it easier for customers to buy Hitachi products by making the money side of the transaction just as engineered as the hardware.

Hitachi Capital operated as the Hitachi Group’s financial services arm, spanning receivables collection, credit guarantees, insurance, and trust services. Its revenue was spread across Financial Services, Commission Services, and a Global Business unit. And unlike a pure-play Japanese domestic lender, it built a broad toolkit—leasing, loans, and other finance products—usable across an unusually wide range of equipment: technology systems, industrial machinery, medical devices, commercial gear, and even the workhorses of logistics like forklifts and trucks.

This is the elegant logic of captive finance. When the manufacturer owns the financing arm, you can sell an integrated package: here’s the equipment, here’s how you pay for it, and here’s a structure that matches your cash flows. That matters most for expensive, mission-critical assets—the kind that can force a customer into a painful tradeoff between upgrading and preserving cash. Hitachi Capital existed to remove that friction, and in doing so it helped Hitachi’s operating businesses win deals they might otherwise have lost.

As Hitachi pushed outward, Hitachi Capital followed. It opened a branch office in Singapore in September 1982, early enough to signal real intent. And after building a local footprint with partners and customers, it incorporated in Singapore as an independent private limited company on January 18, 1994. The playbook was straightforward: wherever Hitachi sold and serviced equipment, Hitachi Capital could make the purchase easier—and make the customer relationship stickier.

North America followed the same pattern. Hitachi Capital America Corp. was formed in 1989 as a wholly owned subsidiary, and it built its early focus around transportation finance—financing trucks and trailers in a U.S. economy that runs on road freight.

For decades, this model worked. But the story doesn’t stay linear. The identity of a captive finance arm is stable—until the parent company hits a wall.

In the 2008 fiscal year, Hitachi reported a loss of US$7.8 billion, the largest corporate loss in Japanese history up to that point. The crisis didn’t create all of Hitachi’s problems, but it exposed them. After its peak in the 1980s and 1990s, inefficiencies had accumulated across departments, and the global financial shock turned those slow drifts into acute pain. Hitachi’s record loss—787.3 billion yen—forced a strategic overhaul.

The company regrouped around what it called the “Social Innovation Business,” leaning into strengths in infrastructure and IT and pushing through major structural changes. Unprofitable operations were consolidated, and the company moved into new fields such as digital systems and renewable energy to adapt to changing market dynamics. By March 2011, Hitachi had returned to profitability.

For Hitachi Capital, the parent company’s crisis created a question it couldn’t avoid. Was it simply support infrastructure for a manufacturing giant—or could it become an independent engine of value? That answer would only come into focus in the decade that followed.

IV. The Strategic Pivot: From Captive Finance to Global Asset Platform (2008–2020)

The 2008 financial crisis didn’t just rattle markets. In Japan, it forced conglomerates to ask an uncomfortable question: what businesses truly belonged together, and which ones were just legacy baggage? Both halves of what would become Mitsubishi HC Capital came out of that decade looking very different from the companies that went in.

Hitachi’s response was nothing short of a corporate reboot. From 2008 to 2018, it slashed the number of listed group companies in Japan from 22 to 4, and cut consolidated subsidiaries from around 400 to 202, through restructuring and sell-offs. The direction was clear: shed complexity, double down on a tighter identity, and move toward becoming a company centered on IT and infrastructure maintenance.

Inside Japan, the turnaround became a kind of management folklore—Hitachi, once synonymous with the biggest corporate loss in the country’s history, was suddenly held up as the model for how a mature giant could reinvent itself. But that reinvention created a strategic ripple effect for Hitachi Capital. If the parent company was narrowing its focus, where did a broad financial services arm fit?

The answer arrived in stages. Mitsubishi UFJ Lease had invested in Hitachi Capital in 2016, creating a bridge between two firms that, on paper, lived in the same industry but had grown up in very different corporate cultures. Four years later, that bridge became the path to a deal. In September 2020, Hitachi Capital agreed to be bought by Mitsubishi UFJ Lease—its second-largest shareholder, business partner, and, at times, former rival.

While Hitachi was simplifying, Mitsubishi UFJ Lease & Finance was doing almost the opposite—expanding its reach and ambition. Over the 2010s, it was steadily reshaping itself from a domestic, relationship-driven lessor into something closer to a global asset platform.

The boldest move was aviation. In October 2012, Mitsubishi UFJ Lease & Finance acquired Jackson Square Aviation from Oaktree Capital Management for $1.3 billion. Jackson Square was still young—it had been set up in 2010 with $500 million of seed capital—but it was already built around a valuable niche: owning modern, in-demand commercial aircraft and leasing them to airlines around the world. The deal, financed with cash and bank loans, closed by the end of 2012, bringing Mitsubishi UFJ Lease a credible foothold in top-tier aircraft leasing almost instantly.

The messaging at the time tells you what Mitsubishi UFJ Lease thought it was buying. Jackson Square’s leadership emphasized the ability to fund airlines’ next-generation deliveries at scale, while also pointing to Mitsubishi’s brand and reach in Asia—one of aviation’s fastest-growing markets.

Then came containers—another global, asset-heavy business with long lives, deep logistics ties, and real scale advantages. In 2014, Mitsubishi UFJ Lease & Finance entered marine container leasing through the acquisition of Beacon Intermodal Leasing, whose container fleet was about 1.5 million TEU.

And in 2018, the company planted a flag in sustainability finance. It became the first leasing company to issue a green bond by domestic public offering in Japan—raising funds specifically for environmentally beneficial projects like renewable energy. It wasn’t just a funding tool. It was a signal: this wasn’t going to be a leasing business content to sit on the sidelines of the energy transition.

By the end of the 2010s, the pattern was clear. A decade earlier, these companies were largely defined by their parents—Mitsubishi’s financial ecosystem on one side, Hitachi’s equipment sales machine on the other. Now both were being pulled toward a new identity: global, multi-asset, and much more strategic about where growth would come from.

The platform was taking shape. The next step was making the whole thing bigger than the sum of its parts.

V. The Mega-Merger: Creating a Global Champion (2020–2021)

On September 24, 2020, Mitsubishi UFJ Lease & Finance and Hitachi Capital put out a joint statement: they intended to integrate through an absorption-type merger, effective April 1, 2021. It was the public marker on something that had been building for years—and it would become Japan’s largest consolidation in non-bank financial services.

On April 1, 2021, the deal closed, and Mitsubishi HC Capital was born. Overnight, it became a financial heavyweight: total assets of about 9.7 trillion yen (roughly $89 billion), positioning it as the second-largest leasing company in Japan, with a broader and more complementary portfolio than either predecessor had alone. Its funding credibility came with it, too, supported by credit ratings of A3 from Moody’s and A- from S&P.

The merger math was straightforward, but the logic was more interesting. Mitsubishi UFJ Lease & Finance came in as an approximately $65 billion global commercial finance business. Hitachi Capital added roughly another $35 billion. Together, they created one of the world’s largest commercial finance companies—and, importantly, the fit wasn’t just “bigger.” It was additive. They weren’t stacking the same business twice; they were stitching together different strengths into one platform.

Mitsubishi UFJ Lease brought global asset capabilities—aviation, containers, and real estate—built during its 2010s expansion. Hitachi Capital brought deep manufacturing-linked relationships, strong sales finance capabilities, and a long-running footprint in Asian markets. One side carried a bank-and-trading-company heritage; the other came with manufacturing and technology DNA. Put together, it looked less like consolidation for consolidation’s sake and more like a deliberate attempt to build a globally relevant asset-finance company from two Japanese incumbents.

Management also framed the new company around five focus fields: “Social Infrastructure & Life”, “Environment & Energy”, “Mobility”, “Sales Finance”, and “Global Assets”. That was the strategic map for what Mitsubishi HC Capital wanted to be—less a traditional lessor, more a diversified owner-and-financier of real-economy assets.

Leadership choices reinforced the “integration, not takeover” message. Takahiro Yanai—previously President & Representative Director at Hitachi Capital—became President & Representative Director of Mitsubishi HC Capital. He served as CEO until April 1, 2023, when he moved to Director, Chairman. Taiju Hisai, who had been Director, Deputy President, became Representative Director, President & CEO and Executive Officer effective the same day.

Then came the unglamorous part that determines whether mergers work: plumbing, naming, and reorganization across geographies. In North America, the combined group went to market as Mitsubishi HC Capital America in the U.S. and Mitsubishi HC Capital Canada north of the border. Mitsubishi HC Capital America and Mitsubishi HC Capital Canada, together with Mitsubishi HC Capital (U.S.A.) and ENGS Commercial Finance, were merged to create what the company described as the largest non-bank, non-captive finance provider across North America, with more than $7.5 billion in owned and managed assets.

That “non-bank, non-captive” label wasn’t just positioning—it explained why this combination mattered. Unlike captive finance units that exist to push one manufacturer’s products, Mitsubishi HC Capital could finance across industries. And unlike banks, it could operate with more flexibility around asset ownership and long-duration positions, without being boxed in by the same regulatory balance-sheet constraints. The pitch was simple: a platform that can go where others can’t, and serve customers who don’t want a financing partner tied to a single ecosystem.

For investors, this kind of merger always comes with a trade-off. The upside is scale, diversification, and global reach—advantages that tend to compound in asset-heavy finance. The downside is integration risk: blending systems, aligning incentives, and getting two corporate cultures to run as one. In the years after the merger, Mitsubishi HC Capital’s record profits and continued dividend growth suggested that, at least operationally, the integration was landing.

VI. The Acquisition Spree: Building Global Asset Platforms (2021–Present)

Once the merger was done, Mitsubishi HC Capital didn’t spend much time admiring the new nameplate. It moved quickly to turn “one combined company” into something that actually mattered in the market: bigger platforms, denser networks, and real operating scale in a few asset categories where scale is the whole game.

The clearest example was containers.

In 2021, CAI International—one of the world’s leading transportation finance companies—agreed to be acquired by Mitsubishi HC Capital. At the time, CAI managed a global container fleet of roughly 1.8 million container equivalent units, run through 13 offices across 12 countries, including the U.S. In other words: not a niche player, but a real network with global reach.

Mitsubishi HC Capital agreed to buy CAI for $56 per share in cash, a hefty premium to where the stock had been trading. Preferred shareholders were also cashed out at $25 per share, plus accrued and unpaid dividends. CAI’s board approved the deal unanimously, and on November 22, 2021 (U.S. local time), the acquisition closed. CAI became a wholly owned subsidiary.

But the real strategy wasn’t just “buy CAI.” It was “combine CAI with what we already own and build a scaled platform.”

Remember: Mitsubishi had entered container leasing years earlier by acquiring Beacon Intermodal Leasing. After the CAI deal, management didn’t leave those businesses running in parallel. Mitsubishi HC Capital’s Executive Committee approved merging CAI International and Beacon Intermodal Leasing, and that merger became effective January 1, 2023. The combined company kept the CAI name and set its headquarters in San Francisco.

The end result was the point: a fleet of roughly 3.5 million TEUs under one roof, making the combined CAI one of the world’s largest container lessors—often described as the third-largest. It also placed Mitsubishi HC Capital squarely in the top tier of a market dominated by a relatively small set of global players, where size and cost of capital tend to decide who wins.

North America was the other major integration push. Mitsubishi HC Capital America and Mitsubishi HC Capital Canada combined with Mitsubishi HC Capital (U.S.A.) and ENGS Commercial Finance. The goal was straightforward: create what the company called the largest non-bank, non-captive finance provider across North America, with more than $7.5 billion in owned and managed assets. Craig Weinewuth, formerly President and CEO of ENGS Commercial Finance, became President and CEO of the combined business, pointing to broader product scope and higher service levels as the drivers.

While containers and North American commercial finance were being consolidated, aviation kept expanding as a second pillar of the global platform.

Jackson Square Aviation—acquired back in 2012—continued to build a portfolio of modern Airbus and Boeing aircraft leased to airlines around the world. Since JSA’s founding in 2010, its fleet had steadily grown, and it remained a core part of Mitsubishi HC Capital’s global assets strategy.

And then there’s the even more specialized part of the aviation stack: engines.

Engine Lease Finance, based in Shannon, Ireland, added exposure through aircraft engine leasing. With offices in Boston, London, and Singapore, ELF positions itself as a leading engine financing and leasing company, backed by Mitsubishi HC Capital’s scale and funding. After more than 35 successive years of profits and portfolio growth, it owned roughly 400 aircraft engines valued at over $4 billion. In August 2025, Engine Lease Finance Corporation signed a purchase agreement with CFM International for 50 new-generation LEAP-1A and LEAP-1B engines—high-demand, narrow-body workhorses. ELF had also broadened its business into aircraft parts through its acquisition of INAV LLC in 2017.

Step back, and you can see the playbook: aggregate assets where operating scale matters, then use funding strength and portfolio breadth to keep compounding.

That strategy has real economic advantages—larger fleets can mean better pricing from manufacturers, lower per-unit management costs, and more efficient funding. But it comes with a trade-off, too. Building big platforms in containers and aviation concentrates exposure to global trade, airline cycles, and transportation markets. The upside is structural. The risk is real. The only way it works is disciplined portfolio management—especially when the world gets choppy.

VII. The Renewable Energy & ESG Transformation

“Environment & Energy” is one of Mitsubishi HC Capital’s five strategic pillars—and it’s where the company has been working to move from a traditional lessor into something closer to an asset owner and builder inside the energy transition.

The clearest signal came in Europe. Mitsubishi HC Capital agreed to buy a 20% stake in European Energy A/S, received regulatory approvals, and completed the transaction in April 2024. As part of strengthening the partnership, Keiro Tamate, Deputy Managing Director at Mitsubishi HC Capital, was elected to European Energy’s Board of Directors. European Energy’s Chair, Jens Due Olsen, framed the deal as transformative for their balance sheet and pace of growth: “The strategic partnership with Mitsubishi HC Capital will triple European Energy’s equity, enabling European Energy to further enhance its role in the green energy transition,” he said, adding that Mitsubishi HC Capital’s international presence and strategic mindset would be “invaluable” on the journey ahead.

Structurally, the investment came through the issuance of new shares. European Energy received gross proceeds of about EUR 700 million, and Mitsubishi HC Capital became the company’s second-largest shareholder, holding 20% of the share capital and voting rights.

European Energy itself is a meaningful platform to plug into. Founded in Denmark in 2004, it develops renewable energy across the value chain and operates in 28 countries, with a development pipeline exceeding 60 GW. It’s also positioned as a pioneer in Power-to-X (PTX), and it is constructing what it describes as the world’s largest e-methanol facility alongside a broader PTX project pipeline.

For Mitsubishi HC Capital, this wasn’t just about putting money to work. It was a way to expand its Environment & Energy business into a region where decarbonisation efforts are advanced and demand for green power is expected to grow significantly—by partnering with a developer already operating at European scale.

This push didn’t come out of nowhere. The company’s sustainable finance track record goes back to 2018, when it issued its first green bond in Japan. The proceeds from that bond, issued April 17, 2018, were fully allocated to eligible green projects: five solar power generation projects in Japan. Those projects were expected to reduce carbon dioxide emissions by around 12,000 tons per year and generate roughly 24,000,000 kWh annually.

The UK business also leaned in with explicit targets and financing. In March 2021, the UK group issued a $40 million green bond under its Green Financing Framework, aimed at clean transportation and renewable energy. The eligible project pool included electric vehicles, hybrid vehicles, and green and renewable energy initiatives.

Underneath all of this is a strategic shift in how Mitsubishi HC Capital wants to participate in the sector. Management has described an evolution from simply financing assets to owning, operating, and developing them—an “Asset O&D” model, short for Origination and Development. In practice, that’s a fundamental change: not just providing capital to renewables developers, but taking an active role in building and operating the asset base.

In Environment & Energy, the group positioned itself as one of the leading renewable energy players in Japan, and it has invested in renewables in Europe and North America since 2017. Going forward, it planned to strengthen the renewable energy business and turn it into a growth driver by expanding more aggressively overseas.

For investors, the attraction is obvious: renewable energy sits at the center of one of the defining investment themes of the coming decades. The harder questions are about execution. Can a company built on leasing and finance operate energy generation assets effectively? Does it have, or can it assemble, the technical expertise that renewables ownership demands? And can it earn returns that hold up against specialists who have done nothing else for years?

VIII. The Mobility & Auto Leasing Play

Mobility is Mitsubishi HC Capital’s most direct link to everyday consumers—and its cleanest angle on the auto industry’s electric shift.

That became much more explicit in April 2023, when the group reorganized its auto leasing footprint. Mitsubishi Corporation, Mitsubishi HC Capital, Mitsubishi Auto Leasing Corporation, and Mitsubishi HC Capital Auto Lease Corporation merged Mitsubishi Auto Leasing and Mitsubishi HC Capital Auto Lease, effective April 1, 2023. The merger had been agreed to by the two parent companies and contractually confirmed by the operating subsidiaries. The combined business kept the Mitsubishi Auto Leasing name, with Mitsubishi Corporation and Mitsubishi HC Capital holding equal shareholder voting rights.

The strategic logic was simple: both legacy companies brought large customer bases and hard-earned operating know-how. Put them together, and management expected two things. First, near-term synergies—growing existing operations and strengthening services aimed at safer driving. Second, a longer-term evolution into a leading player in eco-friendly vehicle adoption, positioned to help societies decarbonize, support circular-economy models, and tackle other structural challenges tied to transportation.

All of this is playing out inside what the industry likes to call the “CASE” revolution: Connected, Autonomous, Shared, and Electric. Mitsubishi Corporation underscored that direction in its management plan, “Midterm Corporate Strategy 2024 – Creating MC Shared Value,” which emphasized jointly promoting businesses that advance both digital transformation (DX) and energy transformation (EX), while also contributing to the revitalization of Japan’s regional communities.

You can see the financial reality of the EV transition most clearly in the UK operations. Mitsubishi HC Capital has continued to push climate-action initiatives in transport, helping fleet managers chart a course toward “net zero.” But it’s not a frictionless transition. Falling electric vehicle resale values created losses—partly offset by stronger income from other transportation assets. The company’s response was to keep customers moving through the uncertainty with affordable fixed-rate finance paired with asset management services, while continuing to invest for growth.

That residual-value problem isn’t a UK-specific footnote. It’s one of the central risks in EV leasing, everywhere. Internal combustion cars come with decades of resale data and well-understood depreciation patterns. EVs don’t. Battery degradation, fast-moving technology, and shifting buyer preferences make it harder to predict what a vehicle will be worth at the end of a lease. And in leasing, that forecast isn’t a detail—it’s the margin. Get residual values wrong in either direction, and returns evaporate.

IX. Business Model Deep-Dive: How Asset Finance Actually Works

At its core, Mitsubishi HC Capital runs on a simple idea: most customers don’t actually want to own expensive equipment—they want the use of it, on predictable terms, with the option to upgrade, return it, or replace it when their needs change. That’s the promise. The reason the company is so interesting is the scope of where it applies that promise: aircraft and engines, shipping containers, railcars, renewable energy assets, vehicles, logistics facilities, and more. Same basic concept—very different risk profiles.

In practice, Mitsubishi HC Capital and its subsidiaries provide leasing, installment sales, and other financing across Japan, North America, Europe, the Middle and Near East, and Asia/Oceania. The company organizes itself across a wide set of segments—including Customer Business, Account Solution, Vendor Solution, LIFE, Real Estate, Environment & Renewable Energy, Aviation, Logistics, Mobility, and Others—because the needs of a government agency, a corporate fleet manager, a solar developer, and an airline are not remotely the same. Across those groups, it provides financing solutions to corporations, government agencies, and vendors; supports sales finance in partnership with vendors; develops, operates, and leases logistics and commercial facilities; and also participates in areas like community development, food and agriculture, living-essentials industries, and non-life insurance.

Most of what Mitsubishi HC Capital does can be understood through two basic lease types.

Finance leases are economically close to a secured loan: the customer commits to payments that cover the asset’s full cost plus interest, and ownership often transfers at the end. Operating leases are closer to a true rental: Mitsubishi HC Capital keeps ownership, and the customer pays for access for a defined period.

That distinction sounds technical, but it’s where the business gets its bite—and where the risk lives. Operating leases can be very attractive because the lessor can profit not just from the lease payments, but from what the asset is worth later. If residual values hold up better than expected, disposition gains flow to the lessor. If residual values fall, the lessor eats the loss. That dynamic becomes especially sharp in assets that can become obsolete quickly, and in industries where demand swings can whipsaw market prices.

One structural reason Mitsubishi HC Capital can play in these markets at scale is that it isn’t a bank. Banks operate under capital rules that make long-duration, illiquid assets expensive to keep on balance sheet under Basel III and related frameworks. A non-bank finance company has more room to hold and manage these assets directly, which can translate into a real competitive edge—especially in categories like aviation, containers, and other long-lived equipment where ownership and lifecycle management matter.

You can see that positioning clearly in North America. Mitsubishi HC Capital America, together with Mitsubishi HC Capital Canada, operates as a specialty finance platform serving organizations across the region, combining consultative underwriting with a broad digital platform. The company describes itself as the largest non-captive, non-bank commercial finance provider in North America, with $7.5 billion in assets and more than 800 employees.

Underneath the products is a funding business. Mitsubishi HC Capital’s model depends on reliable access to capital at attractive rates, supported by strong credit ratings and global market reach. The company aims to balance continuity of funding, flexibility, and cost by borrowing across a range of maturities and raising multi-currency fixed and floating rate debt in major markets. Its funding sources include European medium term notes, a securitisation programme, two commercial paper programmes, uncommitted bank facilities, and some borrowing from Mitsubishi Group companies. The European medium term note programme and both commercial paper programmes are supported by a guarantee from Mitsubishi HC Capital Inc., and as a result are rated A-/A2 by Standard & Poor’s.

The basic economic engine is the spread: borrow at one rate, lease or finance at a higher rate, and manage risk tightly enough that the difference drops through as profit. When it works, it can produce attractive returns on equity. But it also makes the risk map clear: shifts in interest rates, changes in credit spreads, and disruptions in capital market access can all hit the model quickly—and they matter just as much as whatever is happening out on the tarmac, the highway, or the shipping lanes.

X. Competitive Landscape & Investment Considerations

To understand Mitsubishi HC Capital’s edge, you have to remember what it actually competes in. Not one market, but several—each with its own incumbents, economics, and ways to lose money. The company’s diversification is a strength, but it also means its “competitive position” is really a portfolio of competitive positions.

Aviation leasing is the cleanest example.

Aviation Leasing: A Crowded Sky

Aircraft leasing is dominated by a handful of global giants. In 2024, AerCap, SMBC Aviation Capital, and Avolon together controlled roughly 30% of the global fleet—an industry with real concentration at the top, and fierce competition everywhere else.

AerCap is the benchmark. It calls itself the global leader in aircraft leasing, and it has the scale to make the claim credible—especially after its acquisition of GE’s aircraft leasing unit, GECAS, which closed on November 1, 2021. With that combination, AerCap positioned itself as a leader not just in aircraft, but also engines and helicopters. Headquartered in Dublin with offices globally, AerCap reported total assets of $74 billion as of September 30, 2024. Its portfolio included about 1,700 aircraft, more than 1,000 engines, and more than 300 helicopters, serving around 300 customers worldwide.

That context matters for Jackson Square Aviation. JSA’s 334-aircraft fleet places it among the top ten global lessors—but it’s still operating in the shadow of AerCap-scale competitors. The market itself is growing: the commercial aircraft leasing market was projected to reach $181.75 billion in 2025 and grow to $263.67 billion by 2030. But growth doesn’t automatically mean easy returns. In leasing, the fight is over funding costs, aircraft availability, customer relationships, and—when cycles turn—residual values.

Container Leasing: Scale Matters

Containers look simpler than aircraft, but the competitive logic is similar: scale is leverage.

In the United States, Triton International is the largest player in intermodal container leasing, and the industry is consistently competitive. Triton points to the advantage that comes from being huge: a global network, a deep inventory pool, and “creative” lease structures backed by what it describes as the world’s largest fleet—over 7 million TEU.

That’s the bar Mitsubishi HC Capital is measured against. The combined CAI–Beacon platform, at roughly 3.5 million TEUs, is big enough to matter globally, even if it isn’t the market leader. In container leasing, being “significant” is valuable—because it can improve purchasing terms, expand depot and customer coverage, and reduce per-unit operating costs—but it also puts you in a market where pricing pressure never really goes away.

Strategic Analysis: Porter's Five Forces

Threat of New Entrants: LOW-MEDIUM

The biggest barrier is capital—followed closely by time. Aircraft leasing requires enormous balance sheets and long relationships with airlines and manufacturers. Container leasing requires global operations, depot networks, and shipping line relationships. New money can enter—private equity and sovereign wealth funds have increasingly done so—but operational complexity limits how many entrants can compete at scale for long.

Bargaining Power of Suppliers: MEDIUM

In aviation, Boeing and Airbus have meaningful leverage: supply is concentrated, delivery slots can be scarce, and lessors compete for access. Containers are different—manufacturing is more competitive, with Chinese manufacturers providing ample supply. Mitsubishi’s keiretsu-linked funding advantages help, but they don’t remove supplier power in tight aircraft markets.

Bargaining Power of Buyers: MEDIUM-HIGH

Airlines can negotiate aggressively and run competitive processes across lessors. Large shipping companies can do the same. The mitigating factor is stickiness: long-duration contracts and specialized assets—especially engines—can create switching costs. But in more commoditized financing, buyers have plenty of alternatives.

Threat of Substitutes: LOW-MEDIUM

Bank lending can substitute for leasing, but banks have often been less willing to hold these long-duration, asset-heavy exposures in the post-Basel III world. Outright purchase is another substitute, but it ties up capital that airlines and shipping companies often prefer to keep liquid. Operating leases remain attractive because they offer flexibility—particularly in volatile industries where asset ownership can become a trap.

Competitive Rivalry: HIGH

This is where the pressure shows up. In aviation, AerCap, SMBC Aviation Capital, Avolon, and other global players compete hard for placements. In containers, Triton, Textainer, and others fight for shipping line business. When products look similar, competition tends to compress margins—pushing lessors to differentiate through service, financing structures, asset selection, and access to low-cost funding.

Hamilton's 7 Powers Analysis

Scale Economies: STRONG

Scale is real power in this business. Mitsubishi HC Capital’s nearly 10 trillion yen asset base can translate into better pricing from OEMs, lower per-unit costs to manage fleets, and more advantageous funding terms—advantages that compound over time.

Network Effects: MODERATE

These aren’t consumer-style network effects, but relationship density matters. Mitsubishi ecosystem ties can generate referrals and repeat business, and global presence can enable cross-selling across regions and asset types.

Counter-Positioning: PRESENT

Banks have constraints around holding illiquid assets and long-duration exposures under post-crisis regulatory frameworks. Mitsubishi HC Capital can hold and manage assets in ways banks often cannot, which can be a structural advantage in categories like aircraft, engines, and containers.

Switching Costs: MODERATE-STRONG

Aircraft and engine leases are long contracts, often spanning five to twelve years, and the operational relationship around fleet management creates additional friction. That stickiness is weaker in commodity financing, where terms are easier to replicate and customers can switch more readily.

Key Performance Indicators for Investors

This is a complicated, multi-asset finance business. Two metrics help cut through the noise:

-

Net income growth and ROE trajectory: The company delivered record profits for three consecutive years and guided for continued growth. The key question is whether that growth translates into returns on equity that stay above the cost of capital as the portfolio scales and the cycle inevitably shifts.

-

Asset utilization rates: Across aviation, containers, and mobility, utilization is the real-time signal of demand and asset quality. Falling utilization can be an early warning—oversupply, weakening customers, or a market turning faster than lease books can adjust.

Track those consistently, and you get a clear view of what matters most here: whether Mitsubishi HC Capital can keep compounding earnings without losing discipline on capital efficiency. That—more than any single deal—determines long-term shareholder returns.

XI. The Investment Thesis: Bull Case, Bear Case, and Key Risks

The Bull Case

Mitsubishi HC Capital sits where several long-running trends overlap: air travel continuing to expand, the energy transition pulling capital into new infrastructure, and more companies choosing to lease critical assets rather than tie up balance sheets owning them. That’s exactly the kind of environment a scaled, diversified asset finance platform is built for. Aviation, containers, renewables, real estate, mobility—each business line can grow on its own, and together they can smooth out the bumps when any one market turns down.

Then there’s the advantage you can’t easily replicate: heritage. The Mitsubishi keiretsu connection brings funding strength, relationships across Japanese industry, and an institutional stability that helps win long-term customers. In a business where cost of capital and trust matter as much as salesmanship, those are real structural tailwinds.

The post-merger scoreboard has also been strong. Mitsubishi HC Capital reported net income of 135.1 billion yen for the fiscal year ended March 2025—record-high profit for the third straight year—and it planned 160.0 billion yen for the fiscal year ending March 2026. If it delivers, it’s more than growth; it’s evidence that the integration created an operating machine that’s still gaining momentum.

The company’s energy push adds another layer. The stake in European Energy gives Mitsubishi HC Capital exposure to a developer operating at scale in Europe, including power-to-X ambitions, while its Japanese solar investments help build experience on the ownership and operations side. If management can execute the shift from “financing” to “owning and developing,” that’s a path to becoming more than a traditional lessor.

The Bear Case

The same diversification that makes Mitsubishi HC Capital resilient also makes it complicated. Running aircraft and engine leasing, container fleets, renewable power assets, real estate, and vehicle leasing isn’t one business—it’s several. Each has different cycles, different operational demands, and different ways to get risk wrong. Pure-play competitors can focus talent, systems, and capital on a single domain. Mitsubishi HC Capital has to be good at many.

Cyclicality is the other structural issue. Aviation leasing is exposed to airline distress in downturns, and the COVID era was a reminder of how quickly a healthy lease book can come under pressure. Container leasing is tied to global trade volumes, which now face uncertainties from tariffs, supply chain reconfiguration, and shifting geopolitics. The company has acknowledged the possibility of an economic slowdown in the U.S. and Canada due to U.S. tariff measures, but it did not incorporate that into its forecast for FYE3/2026 because the specific negative impact is difficult to quantify today.

Even the keiretsu advantage has a flip side. Preferential relationships and stability can raise governance questions for public shareholders: when trade-offs appear, whose priorities win? Japan’s corporate governance code, effective from June 2015, pushed listed companies to explain the rationale for cross-shareholdings, and major Japanese megabanks have signaled intentions to further reduce them. That long-term unwind can change the shape of group dynamics over time—sometimes in ways outside investors don’t see until after the fact.

Key Risks to Monitor

Interest Rate Exposure: The business runs on funding. Higher rates raise costs, and sustained increases can compress margins, even with hedging and diversified funding.

Residual Value Risk: Operating leases only look safe until the exit price changes. Technology shifts—like fast-moving EV adoption patterns or aircraft efficiency improvements—can reduce asset values faster than expected.

Concentration Risk: For all the diversification, aviation and containers still tie results to global travel and trade. Prolonged weakness in either can hit utilization and returns.

Currency Exposure: With major overseas operations in dollars, euros, and other currencies, exchange-rate moves can swing reported results.

Regulatory and Geopolitical Risk: Aviation lessors face ongoing uncertainty tied to Russia-related claims following the 2022 seizure of aircraft. Container leasing can be affected quickly by shifting trade policy.

Conclusion: A Silent Giant Worth Watching

Mitsubishi HC Capital is a case study in modern Japanese corporate evolution: two captive finance businesses, originally built to serve their parent ecosystems, turning into a global asset platform with real scale. The 2021 merger didn’t just make the company bigger—it gave it breadth, funding strength, and a strategic map that spans global assets, mobility, and the energy transition.

The investor question now is less “what is this company?” and more “can it keep earning its complexity?” The early evidence—record profits, continued dividend growth, and what appears to be disciplined execution—leans encouraging. But the risks are real: multiple cycles to manage at once, operational demands across very different asset classes, and an energy transition that rewards expertise, not intent.

Mitsubishi HC Capital can still feel misclassified by the market—part financial company, part infrastructure investor, part asset operator. For investors willing to do the work to understand that hybrid, the gap between what it is and how it’s valued may be the opportunity.

What started inside the Mitsubishi orbit as a quiet enabler of other businesses has become something far more ambitious: a global owner-and-financier of real-economy assets. The silent giant is no longer invisible. The next chapter is whether it can turn that position into durable shareholder value.

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music