SBI Holdings: Japan's Fintech Empire Builder

I. Introduction & Episode Roadmap

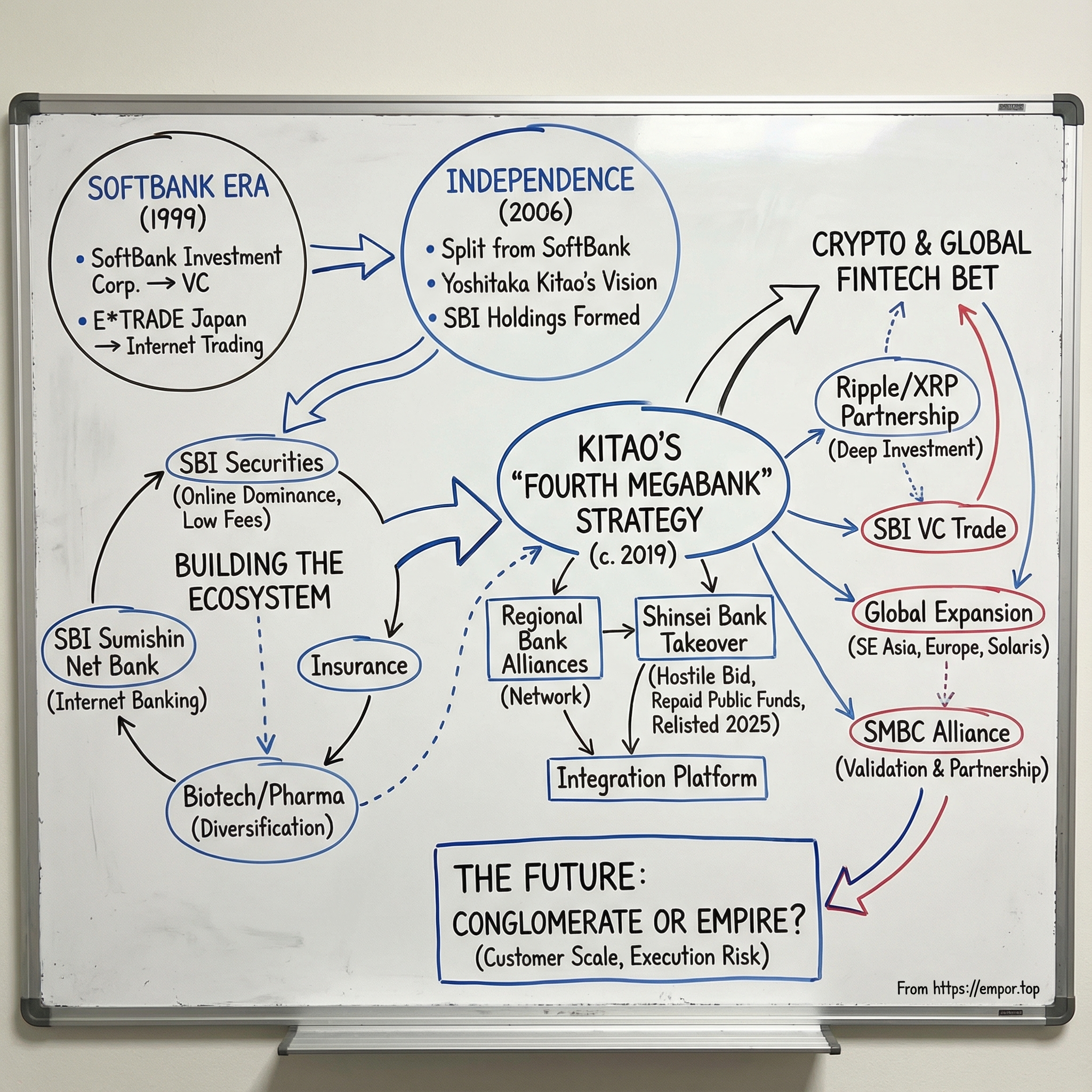

Picture this: a seventy-something CEO who turns to Confucius for strategy, picks fights with entrenched banking institutions, and places a massive, very public bet on a cryptocurrency that spent years under siege in U.S. courts. This isn’t a financial thriller. It’s Yoshitaka Kitao—and the company he built, SBI Holdings.

SBI Holdings, Inc. was founded on July 8, 1999 and is headquartered in Tokyo’s Minato-ku district. Today it’s a multinational financial services conglomerate: a holding company with more than 400 group entities across 14 countries, built around the idea that financial services should be technology-native, interconnected, and relentlessly expanded.

The scope is impressive. The way it was assembled is the real story.

SBI began life as part of Masayoshi Son’s SoftBank orbit. When SoftBank pivoted hard into telecommunications, SBI slipped away—quietly at first—then spent the next two decades turning itself into Japan’s dominant internet-first financial ecosystem. By March 2025, SBI Securities had grown to more than 14 million accounts. In retail reach, it had eclipsed the old guard—Nomura, Daiwa, the institutions that once defined investing in Japan.

Then Kitao went from disruptor to would-be consolidator. In 2019, he announced a plan that made Japan’s financial establishment sit up straight: build a “fourth megabank” by consolidating up to 10 regional banks into the SBI group and plugging them into SBI’s technology. Japan already had three megabanks—Mitsubishi UFJ, Sumitomo Mitsui, and Mizuho—towering institutions with enormous balance sheets and deep history. Kitao’s pitch was that scale could be assembled a different way: not through legacy, but through a network.

To get there, SBI took a path that didn’t look very “Japanese finance” at all. It ran straight through the country’s first hostile takeover battle in banking. It ran through crypto, too—through a relationship with Ripple that’s unusually deep for a traditional financial institution. SBI didn’t just use the technology; it became a major equity investor in Ripple Labs and held XRP as well, giving it exposure on both sides of the bet.

And the “fourth megabank” idea stopped being a slogan and started becoming structure. In December 2025, the Tokyo Stock Exchange approved SBI Shinsei Bank’s listing on its top-tier Prime section, scheduled for Dec. 17. The initial public offering price was expected to be 1,440 yen per share.

So that’s the arc we’re going to trace: how a SoftBank side project became a full-spectrum financial empire spanning securities, banking, insurance, asset management, biotech, and crypto—and how Kitao is now trying to turn that empire into something Japan hasn’t seen before.

The question isn’t whether SBI is big. It’s whether this is the future of Japanese finance—or a sprawling conglomerate held together by the force of one man’s conviction.

To answer that, we have to go back to the beginning: the moment the internet boom collided with Japan’s post-bubble banking reality, and a former Nomura securities man named Yoshitaka Kitao saw an opening that would define his life.

II. The Founding: SoftBank's Financial Bet

The Context: Japan's Financial Big Bang

To understand what SBI became, you have to start with the Japan it was born into. By the late 1990s, the country’s financial system was still living in the wreckage of the 1980s asset bubble. Banks carried bad loans they didn’t want to admit were bad. Entire institutions became “zombies”—kept breathing through government forbearance, but unable to do the job a bank is supposed to do: fund growth.

The broader economy wasn’t offering much relief. Across the decades that followed, Japan was hit by wave after wave of shocks—from the global financial crisis, to the 2011 Tōhoku earthquake and tsunami and the Fukushima nuclear disaster, to the COVID-19 recession. Over the long stretch from the mid-1990s to the mid-2020s, the country’s nominal GDP shrank, real wages fell, and prices stayed stubbornly flat. The result was a national mood of stagnation—and an urgent need for a new playbook.

That’s where the government’s “Financial Big Bang” reforms came in. Between 1996 and 2001, Japan pushed through a sweeping deregulation agenda meant to modernize financial markets: more competition, fewer walls between banking, securities, and insurance, and a clearer path for foreign participation. Whether policymakers intended it or not, these reforms created something Japan hadn’t had in a long time: open space.

And the timing was uncanny. In the U.S., the internet was already ripping through finance. Online brokerages like E*TRADE and Charles Schwab were training customers to expect lower fees, faster execution, and self-service. Technology wasn’t just changing distribution; it was changing the economics of brokerage itself.

Japan was behind the U.S. in internet adoption, but that lag wasn’t a disadvantage if you knew what to do with it. For the right kind of operator, it was a preview of what was coming—and a chance to get there first.

Yoshitaka Kitao: The Architect

That operator was Yoshitaka Kitao.

Kitao had the pedigree of Japan’s financial establishment: Keio University, then Cambridge. He joined Nomura Securities in 1974 and climbed. By the late 1980s he was in London as a Managing Director at Wasserstein Perella, and he later held senior roles bridging Nomura and the Nomura–Wasserstein Perella joint venture. In 1995, he made the move that would define everything that followed: he joined Masayoshi Son’s SoftBank as Executive Vice President and CFO.

The résumé matters because it explains what Kitao was—and wasn’t. He wasn’t a wide-eyed technologist stumbling into finance. He was a career dealmaker and institutional insider who could speak the language of bankers, regulators, and capital markets. That would prove crucial when he started building something that looked, at first, like an internet upstart—and later, like a financial empire.

Kitao also had a personal edge that made him unusual in buttoned-up Japanese finance. He told a story from his Nomura days: he’d worked through the night, came in without shaving properly, and got scolded for it. When he pushed back—saying he’d been up all night working—senior executives heard about it, and instead of punishing him, they defended him. The takeaway wasn’t about stubble. It was about temperament. Kitao didn’t fit the mold, and he didn’t particularly try to. He survived because the people at the top decided he was worth it.

He also framed his career in almost narrative terms—family history as a kind of destiny. His ancestors ran a paper wholesale business, a publisher, and a bookstore in Osaka; his father imported and sold Western books. Information distribution, in other words, ran in the family. When Son invited him to join SoftBank—digital information distribution—Kitao felt, as he put it, like it was fate.

That blend of tradition and aggression would become a signature. Kitao is famously steeped in Chinese classics, especially Confucius’ Analects, and he has written more than 40 books. It’s not the typical profile for a fintech empire builder. But in SBI’s case, it would become part of the brand: ancient philosophy in the front, modern financial machinery underneath.

The Early Moves

SBI’s first steps were decisive and fast. In July 1999, SOFTBANK INVESTMENT CORPORATION was established to start a venture capital business. Then, in October, E*TRADE SECURITIES Co., Ltd.—today’s SBI Securities—launched internet trading services.

Choosing E*TRADE wasn’t incidental. Rather than invent an online brokerage model from scratch, SBI brought in an American template that had already proven it could scale. That gave it credibility, technology, and a clear value proposition in a market dominated by traditional brokerages that still charged eye-watering commissions. In that context, “trade online for less” wasn’t just a feature. It was a threat.

Then came the moment that locked in momentum. In December 2000, SOFTBANK INVESTMENT CORPORATION listed on NASDAQ Japan (later renamed JASDAQ). The IPO arrived near the peak of the dot-com era—an intoxicating time to raise capital, and a dangerous time to confuse hype with a business.

Plenty of internet companies wouldn’t survive what came next. SBI did. Part of that was SoftBank’s orbit—access to capital and attention. But a bigger part was that Kitao was building something with actual customers and repeatable economics. The early SBI wasn’t just “internet.” It was finance, rebuilt around distribution and scale.

And even in these opening moves, you can see the pattern that would define the next two decades: import what works globally, adapt it to Japan, acquire customers relentlessly, and use the capital markets to keep widening the flywheel.

That flywheel was still inside SoftBank—for now. But the tension was already there. SoftBank could be a rocket booster, but it could also be a cage. In 2006, that relationship would finally break—and SBI’s real story would begin.

III. Independence Day: Breaking from SoftBank

The Spin-Off

By the mid-2000s, SoftBank and SBI were pulling toward different futures. Masayoshi Son was fixated on telecommunications. In 2006, he bought Vodafone Japan for $15 billion and made it clear where the center of gravity would be: mobile, distribution, infrastructure. Financial services could make money, but it wasn’t the story Son wanted to tell.

For SBI, that divergence became liberation.

In July 2005, the company changed its name to SBI Holdings, Inc. and shifted to a holding company structure. The name—Strategic Business Innovator—was a mission statement. Kitao wasn’t managing a line item inside SoftBank anymore. He was assembling an empire.

The separation happened in stages. In January 2005, SBI Holdings was removed from the list of SoftBank subsidiaries whose results were consolidated into SoftBank’s financials. And then, in August 2006, the break became official: SoftBank sold its entire stake, ending the capital relationship and making SBI fully independent.

SoftBank Corp. sold its remaining 19.2 percent stake in SBI Holdings to Goldman Sachs Japan. It came right after SoftBank sold 1.11 million SBI shares for 50 billion yen, reducing its stake from 26.7 percent to 19.2 percent—shares that SBI Holdings, parent of SBI E*TRADE Securities, largely bought back. SoftBank’s message was simple: the proceeds would go where Son was going—into improving the mobile business it had acquired from Vodafone K.K., as it raced rivals like NTT DoCoMo.

The split was clean, but it wasn’t a scorched-earth divorce. SBI said it would continue certain tie-ups with the SoftBank group, including providing securities-related information to a Yahoo Japan financial services site. But strategically, SBI was now on its own—free to define itself, fund itself, and expand without asking permission.

There was also an irony that only became obvious years later. Both Son and Kitao would become believers in crypto and blockchain—but they’d place very different bets. Son’s most famous gamble of the next era would be the Vision Fund, with headline-grabbing losses from investments like WeWork. Kitao’s would be quieter at first, then louder than anyone expected: an unusually deep commitment to Ripple and XRP that would eventually shape SBI’s entire crypto playbook.

Building the Financial Ecosystem

Independence created both opportunity and urgency. SBI’s online brokerage engine was working—but Kitao knew brokerage alone was a brutal business to win long-term. Fees compress. Competitors copy. If SBI wanted durability, it needed a system, not a product.

So SBI started building the rest of the stack around the customer.

In September 2007, SBI Sumishin Net Bank, Ltd. commenced operations. The joint venture with Sumitomo Trust (now part of Sumitomo Mitsui Trust) became a defining move: partner with incumbents when it accelerated scale, but keep the experience internet-first and the customer relationship tightly integrated into SBI’s ecosystem. Over time, it would become Japan’s largest internet bank by deposits.

From there, SBI broadened into what it had always been hinting at: a full internet-based financial conglomerate spanning securities, asset management, banking, and insurance. And then it went even wider. The group built a biotechnology-related business line that developed cosmetics, health foods, and drug discovery. It also launched SBI Graduate School, its own business school.

To outsiders, the biotech expansion looked strange—like a financial group wandering off-script. To Kitao, it fit. Japan was aging fast. Health and longevity would increasingly intersect with wealth management, consumer finance, and long-term investment themes. And if SBI was going to be a true conglomerate, it would need internal talent shaped by its own worldview—which is exactly what the graduate school was built to produce.

The "Customer-Centric" Model

SBI framed its growth around what it called a “customer-centric principle,” anchored in innovative technology and a business ecosystem designed to generate synergy across the group.

In practice, it meant something sharper: win the customer by being cheaper, faster, and easier than the legacy firms—and then keep the customer by giving them more places to stay inside the SBI universe.

SBI Securities pushed an aggressive pricing strategy that the old-line brokers struggled to answer. Nomura and Daiwa were built around expensive branch networks and high-touch sales forces. Their economics depended on commission income and relationship management. Cutting fees wasn’t just painful—it threatened the structure of the entire machine.

SBI didn’t have that baggage. Operating primarily through the internet meant a radically lower cost base. It could drop commissions and still make the model work, because the brokerage account wasn’t the end product. It was the entry point.

Every low-cost customer acquired through securities could be monetized elsewhere: banking, insurance, investment trusts, and other higher-margin services. The more products SBI added, the more valuable each customer became—and the more defensible the whole system was against competitors trying to win on price alone.

By the end of this independence chapter, SBI’s strategy was set. Build a technology-enabled ecosystem. Acquire customers through aggressive economics and convenience. Then compound the relationship across the rest of the platform.

The flywheel was spinning—and now, SBI owned it.

IV. Becoming Japan's Online Securities King

The Dominance Story

If you want proof that SBI’s flywheel was real, look at what happened in brokerage.

By March 2025, SBI Securities had grown to over 14 million accounts—more than rivals like Daiwa and even Nomura. And that comparison matters, because Nomura isn’t just another competitor. It’s the institution. Founded in 1925. Built on decades of relationships, armies of salespeople, and the prestige of being Japan’s best-known name in securities.

SBI didn’t exist before 1999. Yet it surpassed the old guard on the metric that defines retail finance: how many customers you actually have. The internet didn’t gradually modernize Japanese brokerage. It reordered it.

A huge part of that shift came from pricing. SBI Securities steadily reduced fees and ultimately eliminated commissions on online trading of domestic stocks. In September 2023, it formalized that push with what it called the “ZERO Revolution,” positioning it as a step toward making investing mainstream.

It wasn’t just a headline-grabbing discount. It was the culmination of a long campaign: force the industry into a world where trading is a low- or no-fee commodity, and then win by being the platform customers live on. Competitors could match commissions, but matching the rest of SBI’s ecosystem was harder.

And the second-order effects were bigger than market share. Japan has long had lower household equity ownership than the U.S., with families holding cash and low-yield deposits instead of stocks. By making access cheaper and easier, SBI helped pull more individuals into investing. That expanded the investor base itself, not just SBI’s slice of it.

The Ecosystem Strategy: "Open Alliances"

Dominance in online securities gave SBI scale. The question was what to do with it.

In its 2020 annual report, SBI laid out the answer: the Open Alliance initiative. The idea was straightforward—pursue growth by forming partnerships with companies that had cutting-edge capabilities in areas like fintech, AI, blockchain, and even quantum computing, plus alliances with firms outside traditional finance.

This was SBI’s model maturing in real time. Early SBI was about building. Open Alliance was about connecting. Instead of trying to invent everything internally, SBI would act as a hub—pulling in specialized partners, integrating what worked, and moving faster than incumbents trapped in slower procurement and legacy IT cycles.

That same mindset showed up in SBI’s investing arm. Originally a vehicle for backing internet entrepreneurs, SBI’s venture activity widened over two decades into a broader technology mandate—most recently with a stronger focus on blockchain developers and crypto-related businesses. Its main corporate venturing vehicle, SBI Investment, managed funds on behalf of 14 corporations and targeted themes like fintech, AI, blockchain, 5G, agtech, IoT, big data, robotics, healthcare, and more.

That venturing machine wasn’t just about financial returns. It gave SBI early visibility into new technologies, created a pipeline for partnerships and acquisitions, and helped ensure SBI stayed close to the next wave before it arrived.

The result is a group that doesn’t look like a single financial company so much as a financial ecosystem. Its Financial Services Business spans securities brokerage, banking, and insurance. Asset management includes traditional products alongside venture investing. The crypto-asset business—exchanges, custody, and blockchain ventures—has become a major strategic pillar. And then there’s the category that always makes people do a double-take: biotech.

The Diversification Bet: Biotech and Beyond

SBI’s biotech push is, in some ways, the purest expression of Yoshitaka Kitao.

He’s not interested in building a tidy, easily categorized company. He’s interested in building an empire that compounds. And he ties that worldview to a personal philosophy shaped by Chinese classics and his own writing—he’s authored more than 40 books—where health, longevity, and long-term success are linked.

SBI’s diversification made that philosophy tangible. Through subsidiaries like SBI ALApromo, it developed pharmaceuticals based on 5-aminolevulinic acid (5-ALA), a compound used in photodynamic therapy and associated with broader health applications. The group also expanded into health foods and cosmetics—businesses aimed squarely at Japan’s rapidly aging population.

For investors, it naturally raises a question: is this smart diversification, or an expensive distraction? Biotech is unforgiving, and success is hard even for organizations built around science. SBI’s strengths are closer to distribution, capital allocation, and marketing than laboratory R&D.

But zoom out, and you can see why SBI kept doing it. Because no matter how far the group diversified, everything still anchored back to the same foundation: distribution.

Those 14 million brokerage accounts weren’t just a milestone. They were infrastructure—a captive audience SBI could serve with whatever products it chose to build, buy, or partner for next. In financial services, customer acquisition is the hardest part. Once you own the customer relationship, adding the next product gets dramatically easier.

That’s the SBI playbook in one line: win the customer once, then compound the relationship forever.

V. The Fourth Megabank Vision: Kitao's Audacious Regional Bank Play

The Strategic Thesis

In 2019, Yoshitaka Kitao put a stake in the ground that made Japan’s usually reserved financial establishment look up. SBI Holdings said it wanted to build a fourth Japanese “megabank”—not by becoming the next MUFG or SMBC, but by consolidating a network of regional banks, potentially up to ten, and plugging them into SBI’s technology and product engine.

The audacity only makes sense once you understand the shape of Japan’s banking system. At the top sit three giants—Mitsubishi UFJ Financial Group, Sumitomo Mitsui Financial Group, and Mizuho—institutions with enormous balance sheets and national reach. Beneath them is a long tail of regional banks: lenders anchored to specific prefectures and local communities, built to take deposits and make loans in places that often aren’t growing anymore.

And Japan, as a macro story, has been leaning against them for years. A declining, aging population drags on growth, keeps rates low, and squeezes profitability across the entire financial sector. Those pressures show up most brutally at the regional level, where banks are tied to the economic vitality of their local area—and many local areas are shrinking.

The demographic math is especially unforgiving in rural prefectures. Young people leave for Tokyo, Osaka, and the big cities. What’s left is an older population with fewer borrowing needs, and small businesses that close when owners retire without successors. For banks whose business is fundamentally “take local deposits, make local loans,” that’s an existential problem. If there aren’t enough borrowers, balance sheets shrink, loan-to-deposit ratios fall, and already-thin profitability gets thinner.

That’s the crisis Kitao saw. But he also saw what was still there: distribution. Regional banks may have been short on growth and modern tech, but they still had deep customer relationships and large pools of deposits. In other words, they still had the one asset that’s hardest to buy from scratch: trust, embedded in local communities.

The Playbook

Kitao’s move was to treat that crisis less like a bailout opportunity and more like an empire-building opening.

At a high level, he framed the plan as building Japan’s fourth mega banking group alongside Mizuho, MUFG, and SMBC—through co-creation with regional banks. But the tactics were practical and phased.

First, SBI showed up as a partner, not a predator. It sold products and services into regional banks and positioned itself as the tech and distribution layer they couldn’t build on their own. As a securities intermediary, SBI signed up 35 regional banks. It built a corporate finance department serving 308 clients. And it created SBI Money Plaza, a “shop within a shop” concept from SBI Securities—piloted with Shimizu Bank and Chikuho Bank, then expanded to seven regional banking outlets.

In parallel, SBI used its investment platform to pull regional banks closer. Twenty-eight regional banks invested in SBI’s FinTech Fund, and 56 invested in the AI & Blockchain Fund. That structure mattered: it made regional banks stakeholders in the technology wave SBI was underwriting, aligned incentives, and created a pipeline of relationships that could later turn into deeper strategic tie-ups.

Then came phase two: equity. SBI’s “fourth megabank” initiative wasn’t just about partnerships—it was about ownership stakes, with Tokyo-based subsidiary SBI Shinsei Bank positioned at the center of the emerging network. SBI’s first investment in a regional bank was in Shimane Bank in 2019.

By 2025, SBI’s acquisition of a 3% stake in Tohoku Bank, a regional institution operating in Iwate Prefecture, marked its 10th such investment since 2022.

The Political Tailwinds

This wasn’t happening in isolation from Japanese politics. Prime Minister Yoshihide Suga, in office from 2020 to 2021, made regional revitalization a national priority. Regional banks were treated as critical infrastructure for local economies—yet the consensus was shifting toward the idea that they also needed to consolidate and modernize to survive.

The regulatory mood moved with it. Japan’s Financial Services Agency began encouraging consolidation among regional banks, and antitrust exemptions were granted for mergers that previously might have been blocked. In effect, the government signaled that rationalizing regional banking wasn’t just acceptable—it was desirable. That made SBI’s pitch feel less like a rogue campaign and more like a plan that fit the country’s policy direction.

From SBI’s perspective, the regional bank push was framed as transformation, not rescue: turning locally rooted lenders into more technologically capable, customer-centric institutions by connecting them to SBI’s platform and tools.

For regional banks, the value proposition was simple. On their own, they didn’t have the scale or expertise to build modern digital infrastructure. Connected to SBI, they could offer more sophisticated services while keeping the local relationships that still mattered. The alternative—slow erosion of relevance—was worse.

For SBI, though, the bet cut both ways. If you can truly knit together a web of regional banks into something coherent, you get scale, deposits, and nationwide reach—built from the ground up through partnerships. But banking integration is famously hard. Cultures clash. Systems don’t talk to each other. Execution risk is the whole story.

The fact that Kitao hit his goal of ten investments in roughly six years suggests he could make deals and build momentum. Whether that momentum could turn into a unified banking force—that was the next test.

VI. The Shinsei Bank Takeover: Japan's First Hostile Banking Bid

The Drama Unfolds

If the regional bank strategy was patient chess, the Shinsei bid was full-contact combat.

In September 2021, SBI launched a rare unsolicited tender offer for Shinsei Bank—an offer worth more than $1 billion—and Shinsei formally rejected it. That set up something Japan’s banking industry essentially didn’t do: a hostile takeover fight.

SBI’s goal was straightforward and surgical. It wanted to raise its stake from about 20% to as much as 48%—enough to gain effective control, without tripping additional regulatory hurdles that a full acquisition would invite.

But Shinsei wasn’t just another regional lender. Its story was tied to one of the most painful chapters in Japan’s modern financial history. Shinsei’s predecessor, the Long-Term Credit Bank of Japan, collapsed in 1998 and was propped up with public funds. After the bank was nationalized, it was sold to a consortium of American investors including Ripplewood Holdings and JC Flowers, rebranded as Shinsei, and returned to public markets in 2004.

In Kitao’s telling, the problem wasn’t just that Shinsei had underperformed. It was that, decades after the bailout, it still hadn’t repaid the public money. To him, that failure wasn’t merely a balance sheet issue—it was a moral one. And it made Shinsei the perfect symbol for what he wanted to change in Japanese banking.

The Poison Pill Battle

Shinsei didn’t go quietly. To block the takeover, management proposed issuing share warrants—rights to receive shares—to existing shareholders, a move designed to dilute SBI’s position. In other words: a poison pill.

That tactic is familiar in U.S. boardrooms. In Japanese banking, it was almost unthinkable. Corporate Japan traditionally ran on consensus, not confrontation. Hostile takeovers were rare to begin with; hostile takeovers of banks were virtually unheard of.

And then the fight narrowed to one decisive player: the Deposit Insurance Corp. of Japan. The DICJ, a government-backed shareholder tied to the original rescue, owned nearly 22% of Shinsei. Both Shinsei and SBI responded to questions from the DICJ, because everyone understood what came next.

If the DICJ sided with Shinsei’s management, SBI’s bid could be blunted or blocked. If it tendered its shares, the takeover could go through. The stakes weren’t just about one bank. Letting a hostile banking takeover succeed would create a precedent in Japan. Stopping it would preserve a status quo that had left Shinsei stuck for years.

Victory and Vindication

Shinsei ultimately blinked.

The bank withdrew its poison pill and accepted SBI’s picks for new president and chairman. The tender offer succeeded, and Shinsei became a consolidated subsidiary of SBI Holdings. For Kitao, it wasn’t just a win—it was a validation of his broader “fourth megabank” vision: if you could take control of a bank like Shinsei, you could build the backbone of something much larger.

Kitao’s message after the victory was clear. He intended to overhaul Shinsei’s leadership and put the bank on a path toward repaying the debts it had carried since the public bailout.

That repayment became the defining mission. By July 31, 2025, SBI Shinsei Bank had completed repayment of 230 billion yen in public funds. Soon after, the bank returned to the market again—its third listing—no longer as a lingering relic of the banking crisis, but as a restructured institution inside SBI’s orbit.

On its first day back on the Tokyo Stock Exchange’s Prime section, the stock opened above its IPO price, traded up to 1,680 yen, and closed at 1,623 yen. Based on that closing price, the bank’s market capitalization stood at about 1.45 trillion yen—one of the largest listings in Japan that year.

In the relisting, the bank raised approximately US$ 2.4 billion and was valued around US$ 8.3 billion—an extraordinary turnaround for a name once synonymous with the excesses and fallout of Japan’s bubble era.

For investors, the Shinsei saga showed two things at once. First: Kitao was willing to fight, publicly, for control—something most of Japanese finance avoided. Second: once he won, he could execute a complex transformation with tangible outcomes. The open question was what that implied for the future. Not every target would capitulate. Not every integration would be clean. But SBI had now proven it could do the most aggressive kind of banking deal in Japan—and come out the other side stronger.

VII. The Crypto Bet: All-In on Ripple and XRP

The Strategic Partnership

Of all Kitao’s contrarian bets, none drew more attention—or more controversy—than his commitment to Ripple and XRP. SBI had been talking up blockchain and crypto since the mid-2010s, but in 2016 it made the relationship real: it invested in Ripple Labs, taking a 9% stake and becoming Ripple’s largest external shareholder. In the same year, the two companies formed SBI Ripple Asia, a joint venture designed to push blockchain-based payments across the region.

That closeness is what makes the SBI–Ripple relationship so unusual in traditional finance. SBI isn’t just a customer of Ripple’s technology. It’s both a major equity investor in Ripple Labs and a holder of XRP. That “double exposure”—owning the company and the token—puts SBI in a small club of institutions that aren’t merely experimenting with crypto, but have tied a meaningful part of their strategic narrative to it.

SBI’s commitment has been described as enormous. It reportedly holds roughly ¥1.6 trillion in Ripple and XRP-related assets—an amount said to exceed its own market capitalization, which has been cited at around ¥1.2 trillion. However you view those figures, the takeaway is the same: this isn’t a side project. For SBI, it’s a core bet.

Practical Application

What separates SBI from a lot of corporate crypto dabbling is that it’s tried to build real rails, not just hold an asset.

In the simplest version of the pitch, someone in Japan can send yen that gets converted into XRP, transmitted quickly, and converted into another currency—like Philippine pesos or Vietnamese dong—in seconds. SBI has positioned XRP as a bridge asset for cross-border remittances, aiming to reduce both friction and cost versus traditional correspondent banking.

The ecosystem around that idea has kept expanding. Doppler Finance, which describes itself as XRP-focused yield infrastructure, planned to work with SBI Ripple Asia to develop compliant, transparent products aimed at institutional clients. SBI Digital Markets—a unit regulated by Singapore’s Monetary Authority—has been appointed as the institutional custodian, offering segregated custody for client assets.

Stablecoins are also becoming part of the story. Ripple, in collaboration with SBI, is set to launch RLUSD, Ripple’s U.S. dollar-backed stablecoin, in Japan by the first quarter of 2026, pending regulatory approval. The logic is straightforward: if RLUSD is used on the XRP Ledger, it could increase activity where XRP is positioned as a bridge currency.

SBI has also signaled it intends to launch a regulated Japanese yen-denominated stablecoin, targeting the first half of the following year, with plans described as landing in the second quarter of fiscal year 2026. The project is set to be developed with Startale Group, a blockchain startup that has previously worked on Ethereum layer 2 efforts with companies including Sony. Separately, SBI and Ripple signed a memorandum of understanding for SBI to act as a key distribution partner for RLUSD in Japan. Using its Electronic Payment Instrument Services Provider License, SBI VC Trade aimed to make RLUSD available to the Japanese market within the fiscal year ending March 31, 2026.

The Crypto Infrastructure

This didn’t appear overnight. SBI had been inching toward fintech infrastructure for years, including a 2013 partnership with Barclays, and then a more direct push into crypto in 2018 with the launch of SBI VC Trade.

From there, it moved to consolidation. SBI acquired all shares of TaoTao Inc., the operator of the crypto asset exchange TAOTAO, making it a wholly owned subsidiary. Rolling exchanges and capabilities under one roof helped SBI build scale—and, just as importantly in Japan, regulatory credibility.

All of that brings us back to the core investor question. The XRP bet is simultaneously SBI’s most polarizing position and potentially its most consequential. If Ripple’s technology becomes mainstream plumbing for cross-border payments, SBI’s early, deep commitment could look prescient. If XRP remains largely speculative—or runs into new regulatory headwinds—SBI’s concentration cuts the other way. When your crypto exposure is large enough to be compared to your own market value, you don’t just participate in volatility. You amplify it.

VIII. The SMBC Alliance: From Disruptor to Partner

The Strategic Shift

For years, SBI made its name as the outsider—an internet-first challenger taking aim at Japan’s financial establishment. Then, in 2022, the establishment didn’t just notice. It partnered.

That year, SBI entered into a comprehensive capital and business alliance with Sumitomo Mitsui Financial Group (SMFG), the megabank group better known as SMBC. SMFG invested in SBI, buying a 9.91% stake for roughly half a billion dollars, and the two sides framed the deal around a simple target: win younger customers through smartphone-native banking and investing.

On paper, the logic was almost embarrassingly clean.

SMFG had the branches, the balance sheet, and the institutional trust—but a customer base that skewed older, and the inertia that comes with legacy systems. SBI had what the megabanks had spent decades trying to build: digital distribution, an online brokerage at massive scale, and a product mindset designed around convenience and low friction. Put them together, and you get a combined offer neither could deliver alone.

Under the 2022 Basic Agreement, the two groups said they would explore a deeper retail-focused digital alliance—designed to deliver comprehensive financial services that cut across “barriers” between the two organizations, reaching not just young customers but also the active mass and mass affluent segments.

For SBI, it was a notable pivot. The company that built its brand by undercutting incumbents was now being invited into the inner circle.

The New Model: Disruption Through Alliance

The tie-up didn’t stop at a cross-shareholding. It grew into an operating plan.

SMFG and SBI later announced a business alliance to establish a wealth management joint venture aimed at strengthening SMFG’s Olive platform—its digital service that bundles banking, payments, and investing into one integrated experience. A preparatory company was expected to be set up by July 2025, subject to regulatory approval, with operations beginning in spring 2026. Ownership was structured across both groups: SMBC Nikko Securities (30%), SBI Securities (30%), Sumitomo Mitsui Banking Corporation (20%), SMFG (10%), and SBI Holdings (10%).

Olive itself is positioned as a unified financial dashboard—accounts, card payments, finance, online trading, and insurance, stitched together. The joint initiative aimed to add a premium tier called “Olive Infinite,” offering upgraded payment and asset management features. It’s also notable for being the first service in Japan to adopt Visa’s top tier, Visa Infinite, as part of the pitch for a higher-end cashless experience.

Crypto and stablecoins showed up here too. SBI VC Trade entered into a basic agreement with Sumitomo Mitsui Banking Corporation (SMBC) to jointly explore the “sound distribution and utilization” of a yen-backed stablecoin issued by SMBC.

All of this raises the most interesting strategic question around SBI’s long-stated dream of building a “fourth megabank.” If you’re already deeply intertwined with Japan’s second-largest megabank group, what exactly is the endgame? Does SBI still need to build a fourth—or is this an admission that some outcomes are faster to reach through partnership than conquest?

For investors, the alliance cuts both ways. It validates SBI’s strategic value—SMFG doesn’t buy nearly 10% of a company lightly. But it also adds gravity. A megabank with that kind of stake will have opinions that are hard to ignore. The bet, for SBI, is that SMFG’s scale, credibility, and resources speed up SBI’s next phase more than they constrain it.

IX. Global Expansion and Recent Moves

Southeast Asia Push

Japan’s shrinking population puts a hard ceiling on how much any financial company can grow at home. SBI’s response has been to look outward—especially to Southeast Asia, where the demographic winds blow the other way and large parts of the financial system are still being built.

One early move came in April 2020, when SBI acquired a Cambodian microfinance institution—SBI LY HOUR BANK PLC. (formerly Ly Hour Microfinance Institution PLC.)—and obtained a banking license. It’s the kind of step that looks modest from Tokyo, but it matters: a licensed foothold in a faster-growing region, with the ability to scale digital financial services over time.

Back in Japan, SBI kept tightening the web it was building around its “fourth megabank” idea. Its partnership with Tohoku Bank fit the same pattern: connect regional balance sheets and local customer relationships to SBI’s product and technology engine, with SBI Shinsei Bank positioned as the center of gravity. And that effort wasn’t happening alone. SBI’s collaboration with NTT—Japan’s telecom giant, and an 8.91% shareholder in SBI—added distribution muscle and national reach to the vision.

Vietnam, though, stood out as the most strategically important market in the region. SBI held a controlling stake in TPBank, a Vietnamese lender, giving it direct exposure to one of Southeast Asia’s most dynamic banking environments. TPBank had weighed on results in prior periods, but as Vietnam’s banking sector stabilized, the outlook improved—and SBI’s positioning began to look more like patience than pain.

European Fintech Acquisition

Then came a move that surprised almost everyone: Europe.

SBI became set to acquire a majority stake of more than 70% in Solaris, a Berlin-based embedded finance platform, as part of the German firm’s fundraising round. Solaris secured about €100 million from SBI for that stake, and planned to raise additional capital from partners including Börse Stuttgart and existing investors, bringing total fundraising to about €150 million.

Solaris said SBI passed the required regulatory ownership control process—an important detail, because in financial services, the paperwork is often the real gatekeeper.

The strategic logic is clear. Solaris provides banking-as-a-service infrastructure, letting non-financial companies offer banking products through APIs. For SBI, that’s not just an “investment in Europe.” It’s a technology and licensing platform that could travel—something that can be plugged into SBI’s broader ecosystem, and potentially reused across markets.

And SBI wasn’t new to the relationship. It had been investing in Solaris since 2017 through managed funds and a subsidiary. Solaris, a CRR credit institution based in Berlin, had built a leading position in embedded finance, with partners including ADAC and the Börse Stuttgart Group. SBI’s step from investor to controlling owner was escalation, not experimentation.

Record Performance

The numbers, at least for now, suggested SBI could afford this kind of ambition.

In Q2 2025, revenue hit a record ¥459.37 billion, driven by broad-based strength across business segments. Pretax income surged, and net profit attributable to owners jumped to ¥69.3 billion.

For FY 2024 consolidated results, SBI reported revenue of ¥1,443,733 million, up 19.3% year-on-year. Pretax income nearly doubled to ¥282,290 million, net income rose to ¥189,158 million, and profit attributable to owners grew to ¥162,138 million. ROE came in at 12.8%, exceeding the company’s 10% target.

Under the hood, the mix told the story of what SBI had become. Investment Business revenue spiked sharply, Crypto-asset Business revenue grew meaningfully, and the core Financial Services Business continued to grind forward.

For investors, the takeaway wasn’t just that SBI had a strong year. It was that the company’s complicated, sprawling strategy—regional bank consolidation at home, crypto infrastructure, Southeast Asia expansion, and now European embedded finance—was showing up in real financial results. The next question was the hard one: whether SBI could sustain that performance while absorbing major acquisitions, managing a broad alliance network, and operating in a macro environment that rarely stays friendly for long.

X. Porter's Five Forces Analysis

Threat of New Entrants: MODERATE-LOW

Japanese financial services are not an easy market to crash. To compete with SBI in any meaningful way, a newcomer needs licenses across securities, banking, and insurance—each with heavy capital requirements and long approval timelines. And even if you clear the regulatory hurdle, you still have to clear distribution. SBI’s scale, anchored by its massive online brokerage customer base and the country’s largest internet bank by deposits, makes it hard to lure customers away in bulk.

But “hard” doesn’t mean “impossible.” The more credible long-term threat comes from global platforms. Apple Pay, Google Pay, and other tech ecosystems can chip away at payments and consumer financial touchpoints—areas where the winner often becomes the default. Smaller fintechs and neobanks can also win on experience and simplicity, even if they start without SBI’s product breadth.

SBI’s defense has been to treat innovation as something you partner with, not something you block. Instead of relying only on moats, it invests in fintech ventures and builds alliances—trying to make sure it’s the platform that benefits when the next wave arrives.

Bargaining Power of Suppliers: LOW

On the supplier side, SBI is in a relatively strong position. Much of the underlying technology stack has become more standardized, and cloud infrastructure can be sourced from multiple providers. More importantly, SBI has spent years building internal technology capabilities, which reduces the risk of being held hostage by any single vendor.

The real constraint isn’t hardware or cloud contracts. It’s people. Japan’s labor market is tight, and competition for engineers and finance talent is intense. SBI’s answer has been to grow its own pipeline—most notably through SBI Graduate School—and to compete head-to-head with traditional institutions on compensation and career paths.

And then there’s another “supplier-like” advantage that’s easy to miss: regulatory credibility. SBI has repeatedly navigated complex approvals—acquisitions, banking integration, crypto licensing—and that track record becomes an asset. New entrants can’t buy that reputation overnight.

Bargaining Power of Buyers: MODERATE-HIGH

Customers have leverage, especially in online brokerage. SBI helped create the expectation that trading should be cheap, and once price becomes the headline feature, investors get ruthless about switching. Opening an account elsewhere is fast, and competitors are always one promotion away.

SBI’s counter is to make the relationship bigger than the brokerage. The more a customer also uses SBI Sumishin Net Bank, SBI Insurance, and the rest of the ecosystem, the less likely they are to leave. Integration does the work here: funds moving smoothly across accounts, consolidated views, easier administration. Each individual product can be copied; the stitched-together experience is harder to unwind.

Threat of Substitutes: MODERATE-HIGH

Substitutes aren’t theoretical for SBI—they’re part of the strategy. Crypto platforms can pull activity away from traditional financial rails, and a world where decentralized finance disintermediates banks and brokers would challenge the foundations of the group’s model.

Global direct-to-consumer investing apps like Robinhood and eToro haven’t yet become dominant forces in Japan, but they’re the kind of entrants that can expand quickly once the timing is right. Even “benign” substitutes matter too: passive investing and index funds can reduce fee pools in asset management, even when they’re distributed through SBI’s own platform.

SBI’s posture is consistent with the rest of its history: don’t deny the substitute—own it early. The Ripple/XRP build-out and its crypto exchange operations are the clearest examples. SBI isn’t hoping this wave fades. It’s positioning to profit if it becomes the new baseline.

Competitive Rivalry: HIGH

Rivalry in Japanese online finance is relentless. Rakuten Securities competes with the advantage of being tied into a major consumer internet ecosystem. Monex and Matsui remain aggressive in targeted niches. And the megabanks—MUFG, SMBC, Mizuho—are no longer dismissing digital as a side channel. They’re investing heavily, fully aware that branch networks are no longer the protective wall they once were.

SBI’s edge comes down to three things: scale, breadth, and time. It built online finance while many incumbents were still debating whether the internet would matter. That early lead compounded into customer relationships, product density, and a platform that can cross-sell in ways single-product competitors struggle to match.

XI. Hamilton's Seven Powers Analysis

Scale Economies: STRONG

By March 2025, SBI Securities had over 14 million accounts—and at that scale, the unit economics start to bend in your favor. The same core technology platform can serve one customer or a million, and the marginal cost of adding the next account keeps falling. Big fixed costs like development, compliance, and infrastructure don’t disappear, but they get diluted across a larger and larger base.

The regional bank strategy reinforces that advantage. Partnerships expand SBI’s distribution without requiring SBI to build branches or hire armies of local staff. Each additional bank adds reach and deposits, while the cost of local presence stays largely with the partner.

Network Effects: MODERATE

SBI’s network effects show up less like a social network and more like an ecosystem flywheel. More customers create more usage data, which improves targeting and product design. A wider product set makes SBI more useful as a one-stop shop, which attracts more customers, which justifies building even more products.

There’s also a lighter version of liquidity effects in brokerage: more activity can support better execution and tighter spreads. But these dynamics are still limited compared to true marketplace network effects. Most customers can use SBI Securities perfectly well without caring who else is on the platform. The “network” is functional, not social.

Counter-Positioning: STRONG

SBI’s move to zero-commission trading is classic counter-positioning. It wasn’t just cheaper pricing—it was a business model that legacy brokers struggled to match without blowing up their own economics. Firms like Nomura and Daiwa were built around branch networks and salesforces funded by commissions. If they matched SBI’s pricing, they risked gutting the revenue that paid for the entire machine. If they didn’t, they risked slowly losing the next generation of customers.

The same dynamic echoes in SBI’s regional bank play. SBI can offer technology and platform partnerships that many regional banks can’t realistically build themselves. Meanwhile, megabanks have little incentive to provide that kind of enablement to potential competitors. SBI’s position benefits from structural asymmetry on both sides.

Switching Costs: MODERATE

Switching costs in finance are weird: on paper, they look low, but in practice, they accumulate. Transferring assets from one brokerage to another is usually manageable. But once customers are running their financial lives through a platform—bank transfers, securities accounts, insurance policies, recurring investments—leaving becomes a hassle.

There’s also real-world inertia: tax considerations can discourage selling and moving positions, familiarity with the interface matters, and automatic transfers and linked accounts add friction. SBI’s ecosystem strategy is designed to make those links deeper, because a customer using three SBI products is far less likely to leave than a customer using only one.

Cornered Resource: MODERATE

SBI’s most defensible resources are the ones you can’t easily recreate: regulatory licenses, long-built customer relationships, and strategic positions accumulated early.

The Ripple partnership and SBI’s XRP exposure sit in this category too. SBI has unusually deep access to Ripple-linked infrastructure and has been involved for years in ways competitors can’t simply copy overnight. Still, whether that ultimately proves to be a true cornered resource depends on how valuable that infrastructure becomes over time—and, critically, on XRP’s long-run role in global payments.

Process Power: MODERATE

SBI has built repeatable processes for acquiring customers at scale, deploying digital financial products, and forming partnerships that pull new capabilities into the group. The regional bank push—reaching ten investments in roughly six years—shows operational competence in relationship-building, deal execution, and integration planning.

But process power only becomes a durable moat when it’s hard to replicate. Many of SBI’s playbooks are visible and, given enough time and commitment, could be matched by well-funded competitors.

Branding: MODERATE

In Japanese online finance, SBI’s brand stands for modern, low-friction, and low-cost. Especially among younger investors, it reads as the practical alternative to the traditional, branch-first incumbents.

But it’s not a premium brand in the sense of pricing power—if anything, SBI has trained customers to associate it with saving money. The brand’s value is in trust and momentum: it pulls in customers who might otherwise choose purely on fees, and it reinforces SBI’s identity as the platform built for how finance works now, not how it used to.

XII. The Investment Case

Bull Case

The bull case for SBI Holdings is that a lot of its biggest bets reinforce each other.

First, the “fourth megabank” idea is no longer just an ambition. SBI Shinsei Bank is expected to play a leading role in the group’s initiative to deepen cooperation with regional banks across Japan. The promise is that this network can become a distribution engine for everything SBI does—banking, brokerage, wealth management—while “speeding up investments in growth areas by leveraging high-quality capital.”

Second, the crypto thesis could be vindicated. Japan is one of the world’s most developed regulatory environments for digital assets, and SBI isn’t dabbling—it’s built real infrastructure and committed early. If XRP becomes widely used for cross-border payments, SBI’s positioning could prove to be one of the more asymmetric bets in global finance: early exposure, deep integration, and the credibility to operate at scale.

Third, Southeast Asia offers growth that Japan simply can’t. Vietnam, Cambodia, and other markets in the region are still building their modern financial systems. If SBI can carry its playbook—digital distribution, partnerships, and platform thinking—into those economies, the compounding could run for decades.

Fourth, the SMFG alliance is both a stamp of approval and a force multiplier. When Japan’s second-largest megabank becomes a capital partner, it signals that SBI isn’t just a scrappy disruptor anymore. It’s an asset the incumbents want on their side—bringing balance sheet resources, distribution, and credibility that can accelerate SBI’s next phase.

Bear Case

The bear case is that SBI has piled on complexity and concentrated risk in places where failure would be loud.

The biggest lightning rod is XRP. SBI’s position has been described as so large that it has been compared to the company’s own market capitalization. If regulatory shifts, technological limitations, or competitive payment rails reduce XRP’s relevance, SBI wouldn’t just lose upside—it could take a direct hit that changes the whole risk profile of the group.

The fourth megabank strategy is also hard in the way banking is always hard. Partnering is one thing. Integrating regional banks with different cultures, legacy systems, and local realities is another. The history of finance is full of mergers and tie-ups that looked elegant on paper and turned into years of friction in practice.

There’s also succession. Kitao has run SBI for more than two decades, and his worldview is woven into the company’s identity. At 75, the question isn’t whether he’s still influential—it’s whether SBI can retain strategic coherence when the organization eventually has to operate without him at the center.

And finally, there’s Japan itself. A shrinking, aging population is a structural headwind that no amount of product innovation can fully erase. Even if SBI executes well, the domestic ceiling is real. The win condition becomes “grow faster than peers,” not “escape the macro.”

Key Performance Indicators

For investors trying to separate narrative from execution, three indicators matter most:

1. Customer Base Growth Rate: Customer scale is SBI’s foundation. Track whether account growth across securities, banking, and insurance continues to compound, because the entire ecosystem strategy depends on it. SBI’s stated goal of reaching 100 million customers by March 2029 is the clearest scoreboard.

2. Regional Bank Partnership Integration Metrics: Don’t just count partnerships—watch outcomes. Are partner banks actually improving profitability and product mix? Are SBI’s technology deployments sticking? The performance of early relationships like Shimane Bank offers the best clues about whether later additions will work.

3. Crypto-Asset Business Contribution: The crypto segment has to become more than a thesis. Investors should watch whether it contributes durable profit through exchange activity, custody assets, and new product launches—and whether that contribution is stable enough to justify the volatility that inevitably comes with the territory.

XIII. Conclusion

SBI Holdings is one of the boldest experiments in modern financial services—anywhere. It started as a venture capital arm inside SoftBank. It spun out and became its own holding-company machine. It used an online brokerage to win distribution, then stacked banking, insurance, asset management, and even biotech on top. And just when it could’ve settled into being Japan’s dominant internet finance platform, it escalated again: a plan to assemble a fourth megabank out of regional lenders, and a crypto strategy built around Ripple and XRP that most traditional institutions wouldn’t touch.

Through all of those pivots, the throughline has been Yoshitaka Kitao. Now 75, he’s proven that Japanese finance can produce empire builders every bit as aggressive and creative as Silicon Valley founders or Wall Street dealmakers. His mix of old-school philosophy and modern platform thinking produced something Japan didn’t really have before: neither a traditional megabank nor a pure fintech, but a hybrid that uses technology, alliances, and capital markets to keep widening its reach.

The next chapter comes with explicit scoreboards. SBI has said it aims to grow to 100 million customers and lift the overseas contribution to 30% of consolidated pretax profit. Those aren’t abstract aspirations—they’re concrete ways to tell whether SBI’s ambition is compounding or stalling.

For investors, that makes SBI unusually “all in one”: a bet on Japan’s financial modernization, on faster-growing markets abroad, and on crypto adoption and infrastructure, all inside a single publicly traded company. The tradeoff is obvious, too. The risk is concentrated—especially around XRP—and the company’s identity is still closely tied to one leader, which makes succession a real variable, not a footnote.

And that’s why the December 2025 relisting of SBI Shinsei Bank doesn’t feel like a finish line. It feels like a marker on the road: proof that SBI can take a scarred banking asset, restructure it, repay public funds, and bring it back to the market as a cornerstone of something bigger. The “fourth megabank” is no longer just rhetoric. It’s beginning to look like an actual structure.

Whether that structure matures into a permanent fourth pillar alongside Mitsubishi UFJ, Sumitomo Mitsui, and Mizuho—or becomes an overreach that stretches SBI too far—will be the defining question of the next decade.

But the earlier verdict is already in. A quarter century after a small venture capital unit began offering internet trading, SBI has permanently changed what Japanese finance can look like. Whatever happens next, the disruption has already taken root.

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music