Chiba Bank: The Regional Banking Champion of Greater Tokyo

I. Introduction & Episode Roadmap

On a quiet day in March 2025, two regional banks headquartered in the same Japanese prefecture revealed a plan that could redraw the map of regional banking in Japan. Chiba Bank and Chiba Kogyo Bank announced a business integration agreement targeted as early as April 2027. In a country where regional banks have been merging for years, the headline itself wasn’t shocking.

What made it worth stopping for was the identity of the buyer—and the playbook it had spent the last decade preaching.

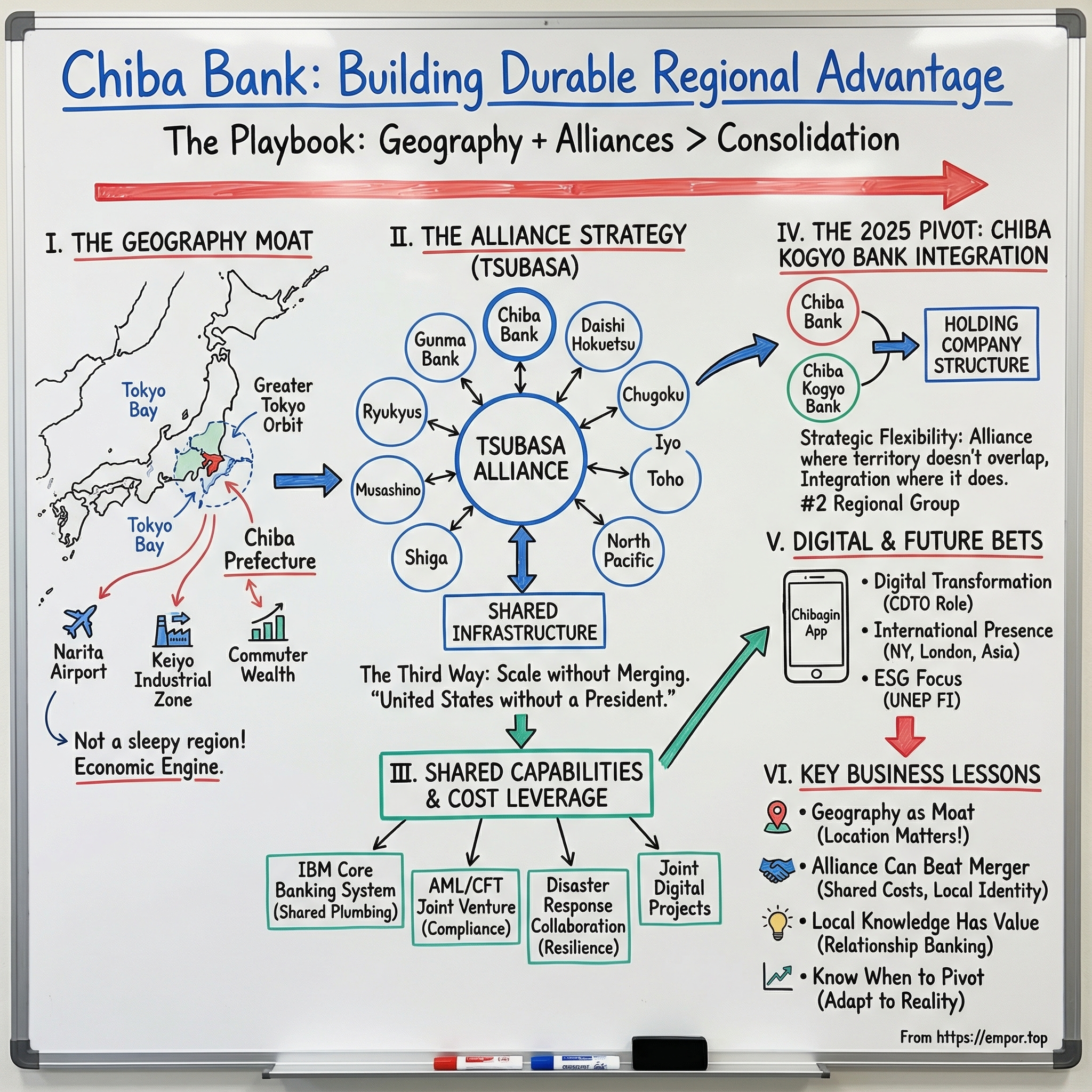

Chiba Bank is the third-largest of Japan’s 64 regional banking groups by total assets, with a market cap of about $6.9 billion. It is, by any standard, one of the heavyweight “locals.” But it’s also a bank that built its modern reputation by arguing against the default solution of the era: full-on consolidation. Instead, Chiba positioned itself as the architect and spiritual center of the TSUBASA Alliance, Japan’s largest partnership of regional banks—an attempt to get the benefits of scale without sacrificing independence.

That sets up the central question for our story: how did a regional bank founded in wartime Japan become the leader of the country’s biggest regional banking alliance—and why might that alliance-first strategy be more powerful than outright mergers?

To answer it, we have to start with geography. Chiba Bank is headquartered in Chiba Prefecture, just east of Tokyo on Tokyo Bay. This is not some sleepy, shrinking corner of the country. Chiba is part of the Greater Tokyo orbit—home to Tokyo Disneyland, Narita International Airport, and a major industrial belt anchored by petrochemicals and heavy manufacturing. In a Japan defined by demographic decline and sluggish rural economies, Chiba sits next to one of the biggest economic engines on the planet.

And that’s the through-line of this story: strategy, not just size. Choosing alliance over absorption. Treating location as a moat. Building shared infrastructure that lowers costs and raises capabilities—without erasing the local identity that makes regional banks work in the first place.

“Our alliance is like the United States without a president. Each of the nine banks revitalizes the local economy. That is our mission.” Former president Hidetoshi Sakuma’s line captures the philosophy in one breath: cooperate deeply, but don’t centralize.

In an era when Japan’s megabanks loom, internet-based competitors keep getting better, and regional lenders are pushed toward survival mergers, Chiba Bank has tried to chart a third way. The big question is whether that approach creates durable advantage—or simply delays the endgame.

Let’s dive in.

II. The Geography Advantage: Why Chiba Matters

Before we can understand Chiba Bank, we need to understand Chiba Prefecture. In regional banking, geography isn’t background context. It’s the business model. And Chiba Bank is playing with arguably the best hand of any “regional” lender in Japan.

Chiba Prefecture sits immediately east of Tokyo on Japan’s Pacific coast, forming a huge part of the Greater Tokyo Area. Much of the prefecture is the Bōsō Peninsula, which wraps around the eastern side of Tokyo Bay. And inside that one piece of geography are three assets that instantly change the economic profile of the region: Narita International Airport, Tokyo Disney Resort, and the Keiyō Industrial Zone.

If you picture Tokyo Bay like a bowl, Tokyo is on the west rim. Kanagawa, with Yokohama, is down to the south. Chiba curves around the eastern and southeastern rim—positioned as both Tokyo’s neighbor and its connective tissue. Narita serves as a primary international gateway for passengers and freight. The Port of Chiba moves an enormous volume of cargo. And the transportation network—trunk highways and projects like the Tokyo Bay Aqua-Line—ties the entire area into the national economy and global trade routes.

Then there’s the industrial engine. Along the Tokyo Bay side of Chiba runs the Keiyō Coastline Industrial Belt: about 40 kilometers of tightly packed heavy industry, with hundreds of steel plants, oil refineries, chemical facilities, and power generation sites. This isn’t a former manufacturing hub hanging on out of nostalgia. It’s core infrastructure for Greater Tokyo—an industrial base that produces energy, raw materials, and key inputs for the broader economy.

By output, Chiba ranks sixth in Japan industrially, with much of that strength concentrated in petroleum, chemicals, steel, and machinery. Those sectors alone account for nearly half of the prefecture’s exports. For a bank, that means something very specific: large, stable commercial customers; complex financing needs; and an ecosystem of suppliers and SMEs orbiting the giants.

But the story doesn’t end with smokestacks and shipping containers. Northwestern Chiba—cities like Ichikawa, Funabashi, Matsudo, and Kashiwa—functions as a classic “bedroom community” zone for Tokyo. Every day, huge numbers of commuters ride dense rail networks into the capital and come back at night. This is the most urbanized, best-connected, and most expensive part of the prefecture, and it creates a very different kind of regional-bank customer: salaried professionals with mortgages, savings, investments, and rising demand for higher-margin financial services.

Chiba Bank has leaned into that reality in a way that sounds obvious, but is surprisingly strategic: it has expanded its branch network into adjacent prefectures along Tokyo-bound commuter rail lines. In other words, it followed the train tracks—placing itself where Tokyo’s workers live, not just where Chiba’s borders happen to be drawn.

At the same time, the bank has also emphasized the development of southern Chiba as a tourist and resort region, particularly around Kamogawa. The southern peninsula—with beaches, hot springs, and leisure travel—offers a different kind of banking opportunity: tourism businesses, second homes, and vacation property financing.

Put all that together and you get something rare in regional banking: real dominance in a truly valuable market. Chiba Bank held a 36.6% share of lending and a 23.0% share of deposits in the prefecture. And inside its customer base were more than 30,000 high net worth individuals with financial assets of ¥100 million or more—essentially a private-banking franchise hiding in plain sight within a “regional” footprint.

This is what a geographic moat looks like. A bank anchored next to one of the world’s largest metropolitan economies, backed by heavy industry, commuter wealth, tourism potential, and critical infrastructure like an airport and seaport. You can build an app. You can open a branch. But you can’t replicate a location like this.

III. Founding & Early History: Born in Wartime

Chiba Bank was established in March 1943, and the timing wasn’t a coincidence. Japan was deep into total war, and the government was aggressively consolidating financial institutions so capital could be steered where the state needed it most.

Those wartime origins mattered. Many Japanese regional banks didn’t emerge the way American regionals did—through open competition and expansion—but through government-directed consolidation. The result was a different kind of institution: tightly interwoven with local governments and local industry, and expected to play a quasi-public role in keeping the regional economy functioning, especially in the years that followed.

After Japan surrendered in August 1945, the Occupation era began. In Chiba Prefecture, American forces operated out of the second floor of the prefectural capitol building in Chiba City, and other cities—including Chōshi in the north and Tateyama in the south—were used as bases as well. Occupation presence plus reconstruction spending created a surge of activity, and for a regional lender positioned in the orbit of Tokyo, that meant opportunity.

The real tailwind, though, arrived with Japan’s economic miracle. In 1950, Chiba was chosen as the site for a major Kawasaki Steel factory. Around the same time, the prefectural government began a large-scale land reclamation program, dredging and creating wide stretches of new waterfront property. Factories, warehouses, and docks followed. This is how the Tokyo Bay shoreline in Chiba became what we now know as the Keiyō Industrial Zone.

Chiba Bank rode that industrial buildout. It financed the big plants—steel, petrochemicals, heavy industry—and just as importantly, the dense web of smaller suppliers that grew up around them. And because relationship banking runs deep in Japan, a company that started with Chiba Bank often stayed with Chiba Bank. Not for a product cycle, or a CEO’s tenure—for generations.

By the 1990s, that long accumulation of relationships had turned into physical presence. Chiba Bank built a broad branch network: 173 branches total, with 154 inside Chiba Prefecture. That density wasn’t just about customer convenience. It was about being everywhere the local economy lived—so embedded that leaving the bank would feel like leaving the region.

Then came the 1990s banking crisis. Japan’s bubble had burst, bad loans piled up, and the system entered the era of zombie companies and financial institution failures. Chiba Bank didn’t get a free pass. In June 1998, Standard & Poor’s downgraded its credit rating from A-minus to BBB-plus, citing negative long-term ratings.

But the bank made it through—and crucially, it did so without losing its independence. That survival said as much about Chiba Prefecture’s underlying economic strength as it did about the bank’s management. In weaker, shrinking regions, many local banks would eventually be absorbed, or survive as diminished institutions. Chiba Bank came out of the crisis bruised, but still very much itself.

The decades ahead would bring a new set of pressures: deflation, negative interest rates, and demographic decline. Yet they also created an opening for an institution willing to rethink what “scale” could mean. In the early 2000s, Chiba Bank’s leadership began exploring a contrarian idea for regional banking survival: collaborate deeply, share capabilities, but don’t give up the local identity. The early seeds of what would eventually become the TSUBASA Alliance were already being planted.

IV. The Japanese Regional Banking Crisis: Context & Challenges

To understand Chiba Bank’s strategic choices, you first have to understand the slow-motion crisis Japan’s regional banks have been living through. This isn’t pundit exaggeration. For years, the Bank of Japan, the Financial Services Agency, and private analysts have all warned that the sector’s economics were getting dangerously thin.

The pressure comes from three directions at once: demographics, interest rates, and competition. And for most regional banks, it’s not a headwind. It’s a vice.

The Demographic Catastrophe

Japan became a super-aged society in 2007, and its population started shrinking in 2011. “Super-aged” isn’t a metaphor; it’s a definition—more than 21% of the population over 65. Japan hit that mark first among major economies, and it hasn’t slowed down since.

For regional banks, demographics are destiny. In an aging, shrinking country, loans per person tend to fall faster than deposits per person. That sounds technical, but the implication is brutal: the typical regional bank ends up with more money sitting around and fewer good places to lend it. Balance sheets stop growing. Loan-to-deposit ratios fall. And the core engine of the business—the spread you earn on lending—starts to sputter.

In rural prefectures, the pattern is painfully consistent. Younger people move to Tokyo, Osaka, and other big cities. The customers who remain withdraw savings in retirement rather than building new ones. Local businesses see their customer base shrink, so they borrow less, invest less, and hire less. The bank’s loan book contracts, fee opportunities dry up, and relationships that used to last decades begin to disappear.

The SME succession crisis makes all of this worse. Across rural Japan, small and medium-sized enterprises—often family-run—shut down because there’s no successor. When the third-generation owner retires and the doors close, the bank doesn’t just lose a single loan. It loses a whole relationship: operating accounts, deposits, payments, advisory work, and the network effects that come from financing an anchor business in a small community.

The Interest Rate Trap

Then there was the other, uniquely Japanese problem: for nearly a decade, the Bank of Japan kept interest rates below zero to fight deflation and stimulate lending. For the broader economy, you can debate whether it helped. For regional banks, it was punishing.

Banking runs on a simple idea: pay one rate on deposits, charge a higher rate on loans, and keep the difference. When rates sink to the floor, that difference compresses toward nothing. And when it compresses far enough, the business stops feeling like banking and starts feeling like cost management with a balance sheet attached.

Yes—more recently, rising interest rates have begun to make it easier for banks to earn money from core lending again. But for years leading up to that shift, regional banks were trapped between razor-thin loan margins and the heavy, fixed expense of maintaining branches and staff. Many responded by cutting branches and headcount, which often created a vicious circle: fewer branches meant weaker local presence, which meant more customers leaving, which meant even less revenue to defend the remaining footprint.

The Competitive Squeeze

As if demographics and rates weren’t enough, competition intensified from both ends.

From above, Japan’s three megabanks—Mitsubishi UFJ, Mizuho, and Sumitomo Mitsui—pushed further into regional markets with national brands, big budgets, and increasingly capable digital offerings. The deposit numbers tell the story plainly: as of March 2025, deposits at 61 regional banks grew just 0.9% year over year, while the megabanks’ deposits rose 2.7%.

From below, internet-based banks started pulling customers with better apps and, especially as rates rose, more attractive deposit offers. Players like Rakuten Bank and SBI Sumishin Net Bank gave younger customers a simple question: why keep an account at the bank your parents used if you can get a smoother experience—and often a better rate—on your phone?

It’s in that context that an SBI Securities analyst put words to what everyone in the industry was already thinking: “I don’t think there’s a single regional bank president who isn’t thinking about consolidation.”

And they were right. Mergers became the default survival plan. But mergers also carry their own landmines—fights over leadership, battles over where the headquarters goes, branch closures, and community backlash when a “local” institution suddenly feels less local.

Chiba Bank looked at the same landscape and decided the industry was asking the wrong question. The choice didn’t have to be “stay small and struggle” or “merge and disappear.” There was a third option: build scale without surrendering identity.

V. The Alliance Strategy: A Third Way

By 2015, the pressure on Japan’s regional banks had become unmistakable. The industry’s default answer was consolidation: merge, cut, centralize, survive.

Chiba Bank decided to try something else.

In October 2015, it helped launch what would become the most ambitious experiment in regional banking in Japan: the TSUBASA Alliance. Tsubasa means “wings” in Japanese—a fitting name for a group built on the idea that regional banks could lift themselves up together, instead of disappearing into one another.

The alliance brought together a wide-area network of 10 regional banks: The Chiba Bank, Ltd., The Daishi Hokuetsu Bank, Ltd., The Chugoku Bank, Ltd., The Iyo Bank, Ltd., THE TOHO BANK, LTD., North Pacific Bank, Ltd., The Musashino Bank, Ltd., THE SHIGA BANK, LTD., Bank of The Ryukyus, Limited, and The Gunma Bank, Ltd.

The philosophy behind TSUBASA was deliberately contrarian. While others formed holding companies and welded balance sheets together, Chiba and its partners chose a looser structure. The banks would collaborate where scale mattered—shared systems, joint products, compliance work, even disaster response—without integrating management or governance.

Then-president Hidetoshi Sakuma put the argument plainly: “When management is integrated, there is a fight for leadership, and it takes a lot of time to decide where to go to the head office. To make the economy of each region revitalize, the shape of the current regional bank should remain.” In other words: mergers don’t just create efficiencies. They also create friction. And in a relationship business, friction is value destruction.

The alliance’s structure reflected that belief. “Our alliance is like the United States without a president. Each of the nine banks revitalizes the local economy. That is our mission.” Each member stayed independent, with its own board, CEO, and local strategy. Participation in any initiative was voluntary; no bank was forced into a project that didn’t fit its needs.

That flexibility was the point. A bank in Okinawa, like Bank of the Ryukyus, lives in a different economic universe than a bank in Hokkaido, like North Pacific Bank. Forcing them into one operating model could flatten what makes each of them useful to their communities. But sharing the cost of IT development, pooling resources for compliance, or coordinating support when disaster strikes—those are scale benefits you can capture without standardizing everything else.

The Chiba-Musashino Alliance and Chiba-Yokohama Partnership

TSUBASA was the big tent, but Chiba Bank also built tighter, more local partnerships on the side.

In March 2016, it launched the Chiba-Musashino Alliance with Musashino Bank, based in neighboring Saitama Prefecture. Since fiscal 2016, that partnership generated cumulative synergies worth nearly 10 billion yen—proof that the alliance idea wasn’t just theory, but something that could show up in real operating improvements.

Then, in July 2019, Chiba Bank signed an agreement with Bank of Yokohama to establish the Chiba-Yokohama Partnership. Strategically, this was about completing the map: Chiba, Saitama, and Kanagawa are the three major commuter suburbs feeding Tokyo. With coordination mechanisms across all three, Chiba Bank positioned itself at the center of the broader Greater Tokyo orbit—not by buying neighbors, but by linking arms with them.

The Sony Bank Collaboration

Chiba also recognized that the new competitive threat wouldn’t look like another regional bank at all. It would look like software.

So in 2022, the bank began a business collaboration with Sony Bank Inc., Sony Group’s digital banking subsidiary. The message was implicit but clear: regional banks can’t outspend digital-native players on technology. But they can partner, borrow capabilities, and avoid fighting an unwinnable arms race alone.

Why It Works (For Chiba)

This approach worked especially well for Chiba Bank because it was playing from a position of strength. As the largest member of TSUBASA, it could help set the agenda without formally “owning” anyone. And because it sat inside the Greater Tokyo economy, it didn’t need a merger to manufacture growth the way many rural banks did.

Operationally, Chiba Bank also had room to lead. Its overhead ratio was around 53%, versus an average of 73% for regional banks. That gap mattered. It meant Chiba could bring competence, processes, and know-how into partnerships—rather than joining alliances as a last-ditch cost-cutting move.

And underneath all of it was the same strategic conviction: local knowledge is the product. “Each region has its own history and unique industrial structure, which lenders based there know most about.” In Chiba’s case, that meant deep familiarity with local SMEs, real estate dynamics along commuter rail lines, and high-net-worth families who were “regional” on paper but lived in one of the wealthiest metropolitan areas on Earth.

For investors, TSUBASA became a rare example of coopetition done with intent: competitors collaborating to gain scale in the unglamorous but essential parts of banking—technology, operations, administration—while keeping the face-to-face relationships that make regional banks sticky in the first place.

VI. The Shared Infrastructure Play

The most tangible payoff from TSUBASA wasn’t a press release or a conference quote. It was shared plumbing—technology and compliance. The stuff customers never see. The stuff that quietly eats budgets. And in a low-margin world, that’s exactly where the alliance could create real leverage.

The IBM Core Banking System

One of the biggest commitments was to share a core banking system—built and supported with IBM Japan. Toho Bank joined Chiba, Daishi Hokuetsu, Chugoku, and North Pacific on the TSUBASA shared core system.

If you want to understand why alliances matter, understand core banking. This is the system that processes deposits, loans, and day-to-day transactions. Replacing it is one of the most expensive, high-risk projects a bank can take on. For a mid-sized regional bank, an upgrade can cost tens of billions of yen and take the better part of a decade. And that’s before you factor in the internal strain: years of IT staff time, vendor management, testing, and the existential fear of a botched migration.

TSUBASA’s answer was simple: don’t do it alone.

The shared system covers the unglamorous but essential guts of banking—business processing for deposits, foreign currency, and loans; channels like ATMs and internet banking; and the data connections that tie the core to all the other sub-systems banks rely on.

The payoff isn’t just lower costs. It’s capacity. By sharing development and support, the member banks can free up money and people to spend on other priorities—especially digital transformation efforts that would be hard to justify when the core system is consuming the whole IT budget.

And it hasn’t stayed static. The collaboration broadened as Gunma Bank moved to work with the TSUBASA Alliance, and IBM Japan and Kyndryl Japan also joined the effort alongside the banks already cooperating on core systems.

The AML/CFT Joint Venture

Then there’s compliance—specifically anti-money laundering and counter-terrorism financing, or AML/CFT. Around the world, this has become one of the fastest-growing cost centers in banking. The rules are detailed. The tooling is complex. Regulators expect rigor. And the downside risk of getting it wrong is enormous.

In response, Nomura Research Institute partnered with three regional banks—Chiba Bank, Daishi Hokuetsu Bank, and Chugoku Bank—to launch TSUBASA - AML Center, LTD., a joint venture focused on combating financial crimes.

The company planned to adopt GPLEX, NRI’s AML/CFT SaaS, as the platform for centralized operations: transaction monitoring, suspicious transaction reporting, name screening, and customer risk assessment.

The design is intentional. Instead of each bank building a duplicative compliance operation—each with its own systems, processes, and staffing challenges—they pool the work in one dedicated entity. Other TSUBASA members are invited to join, with an eye toward expanding the service to more regional banks over time.

It’s also a talent play. A joint venture can create a larger, more specialized team and justify better tooling than any single regional bank might be willing to fund on its own.

Disaster Response Collaboration

And then there’s a reminder that “infrastructure” isn’t only software.

When Chiba Bank’s branch in Chonan-cho, Chiba Prefecture, was damaged by Typhoon No.15, Toho Bank in Fukushima sent a mobile store vehicle with four staff members to keep services running until the branch was restored. The alliance banks jointly developed these mobile stores, each owns one, and they can be deployed when disaster strikes.

That might sound like a small anecdote, but it captures TSUBASA’s philosophy in the real world: keep your identity and your local presence—but don’t face predictable, costly shocks alone.

Strategic Implications

This is where the alliance starts to look less like “friendly cooperation” and more like strategy.

Shared infrastructure can create a cost and capability advantage over non-member regional banks—especially in areas like core systems and compliance where scale matters most. Over time, that could pull the industry’s center of gravity toward TSUBASA, even without formal mergers.

But it also introduces a new kind of dependency. The tighter the shared systems get, the more member banks rely on one another—and on key partners like IBM—to keep the machine running.

For investors, it tees up the real question: do these savings and shared capabilities create durable advantage, or do they simply make eventual consolidation easier? The optimistic read is that TSUBASA lets regional banks preserve what makes them valuable—local relationships—while staying cost-competitive with larger players. The skeptical read is that shared systems standardize operations and flatten differences, turning “alliance today” into “merger tomorrow.”

VII. The 2024 Inflection Point: End of Negative Rates

In March 2024, the Bank of Japan finally flipped the switch. After eight years, it ended yield curve control and scrapped its negative interest rate policy, returning to a more “normal” framework anchored on a short-term policy rate.

This wasn’t a routine adjustment. Japan raised interest rates for the first time since 2007, closing the book on the world’s only negative-rate regime—an era of unconventional policy that had stretched across decades of fighting deflation. The move took the policy rate up from minus 0.1%, and analysts widely framed it as one of the most consequential monetary shifts in modern Japanese history.

For regional banks, the emotional reaction was close to relief. After years in which the basic math of banking barely worked, higher rates offered something the sector had been starved of: the chance to earn real money on plain-vanilla lending again. As rates rose, core lending started to feel like a business, not a public service.

But normalization doesn’t hand out free lunches. It changes who has leverage.

In December 2024, the Bank of Japan made the message even clearer, raising its key short-term rate by another 25 basis points to 0.75%, the highest level since September 1995. It was the second hike of the year, following a similar increase in January—more proof that Japan was steadily backing away from ultra-loose policy.

The impact on regional banks was immediate: better potential margins on loans, yes—but also a new fight over funding.

The Double-Edged Sword

When rates rise, deposits stop being “free.” They become a product customers shop for.

That’s where the pain starts. Regional banks rely on deposits as their cheapest, most stable funding source, but they now have to defend those deposits against megabanks with massive brands and digital banks built for rate-driven customer acquisition. And as the competition heats up, investors have increasingly bet that more consolidation is coming—helped along by a wave of recent mergers and the relatively cheap valuations across Japan’s listed smaller banks.

There’s also a quiet constraint unique to the regional model: many regional banks have been slower to pass rate hikes through to borrowers. Part of that is strategy, part of it is mission—supporting local businesses and households instead of squeezing them the moment the rate environment shifts. But it means the benefit of rising rates can show up more slowly on the asset side of the balance sheet, while deposit competition can reprice quickly.

The deposit growth figures underline the squeeze. As of March 2025, combined deposits at 61 regional banks rose only 0.9% year over year, to ¥333.890 trillion—down from a 2.2% pace the prior fiscal year. Over the same period, deposits at Japan’s three megabanks grew 2.7%. And structurally, the share of total deposits held by regional and shinkin banks has continued to drift downward.

For Chiba Bank, this new world cut both ways.

On the plus side, it entered normalization with advantages most regional lenders don’t have: a dominant position in a wealthy, Tokyo-adjacent prefecture and a deep base of high-net-worth customers who may be less likely to chase incremental rate differences. On the risk side, it can’t opt out of the broader trend. If deposits begin to migrate toward megabanks and internet-based alternatives, even a bank with Chiba’s geographic moat has to compete harder—and spend more—to keep its funding stable.

In other words: the end of negative rates made banking easier. It did not make banking calm.

VIII. The 2025 Mega-Move: Chiba Kogyo Bank Integration

After spending a decade making the case for alliances over mergers, Chiba Bank did something in March 2025 that made the market sit up straight: it bought a major stake in a rival in its own backyard.

Chiba Bank acquired about 19.9% of Chiba Kogyo Bank for roughly 23.7 billion yen, purchasing the shares from Ariake Capital, a Tokyo-based investment fund that had first invested in Chiba Kogyo Bank in 2022. In other words, this wasn’t a slow, friendly courtship. It was a clean opening created by an investor looking for the exit—and Chiba Bank stepping in at exactly the right moment.

The timing mattered. The Bank of Japan had ended negative rates the year before, and competition across the sector was heating up. Deposits were becoming more contested, digital rivals were growing, and regional banks were under renewed pressure to prove they had a plan for a higher-rate, higher-competition world. With that backdrop, the stake read as the first domino in something bigger.

And it was. By September 2025, the relationship had moved from “strategic investment” to “this is happening.” Chiba Bank and Chiba Kogyo Bank announced a basic agreement to pursue a business integration as early as April 2027, under a holding company structure with both banks coming under the same umbrella.

Crucially, it wasn’t positioned as a simple absorption. Rather than merging into a single bank, the plan was for both institutions to continue operating separately, preserving existing brands and customer convenience.

Chiba Kogyo Bank, for context, is the prefecture’s third-largest regional bank, with an operating base centered in Chiba and funds of approximately JPY3tn. This wasn’t Chiba Bank picking up a tiny neighbor. It was choosing to consolidate real weight inside one of Japan’s richest regional markets.

Why This Deal Matters

Combined total assets as of the business year ended March 2025 would be nearly 25 trillion yen—enough to make the group Japan’s second-largest regional banking group, behind only Fukuoka Financial Group.

That’s a meaningful change in posture. Chiba Bank had been a heavyweight already, but this integration would move it up the leaderboard and deepen its dominance at home—right next door to Tokyo, in a prefecture that is large, industrial, and wealthy by regional-bank standards.

The market liked what it saw. Chiba Kogyo Bank’s shares jumped as much as 25%, its biggest intraday gain since September 2020. Chiba Bank’s stock rose too, up as much as 3.6%.

The Holding Company Model

The structure is the tell. A holding company allows Chiba Bank to capture group-level advantages—coordination, shared investment, joint planning—without immediately dismantling what makes regional banks work: local trust and continuity.

In the banks’ framing, this wasn’t just about size. They emphasized the growing complexity of regional needs: customer preferences shifting, behavior moving digital, labor shortages worsening, and sustainability rising on the agenda. Chiba Prefecture is a rich market with a top-tier economic scale, but that doesn’t make it simple—and it doesn’t make competition any easier.

The announcement also stressed “synergies” over slash-and-burn cost cutting. The integration would be executed through a joint share transfer, with the newly created holding company leading collaboration across both groups to maximize the benefits.

How This Fits the Alliance Strategy

At first glance, this looks like a reversal. Chiba Bank had spent years arguing that mergers create distraction—leadership fights, headquarters politics, identity loss—and that alliances were the smarter path.

But there’s a way to read this as consistent, not contradictory.

TSUBASA is built across non-overlapping territories. Most member banks don’t compete head-to-head day to day, which makes it easier to share systems, compliance, and capabilities without turning cooperation into a zero-sum game.

Chiba Kogyo is different. It operates in the same prefecture, often in the same neighborhoods, serving many of the same customers. In that context, the value isn’t just shared infrastructure. It’s what you can only get with integration: coordinated coverage, a stronger combined financial base, and the ability to remove redundancies that a loose alliance can’t touch.

“We’ll work to further revitalize this region,” Chiba Bank President Tsutomu Yonemoto said when the deal was announced.

For investors, the takeaway is that Chiba Bank wasn’t abandoning its alliance philosophy—it was refining it. Alliance where geographies don’t overlap. Integration where they do. Same goal either way: build scale and capability without giving up the local edge that regional banking is built on.

IX. Digital Transformation & Future Bets

If the TSUBASA Alliance is Chiba Bank’s answer to scale, digital is its answer to relevance.

Across Japan, regional banks have been pushed into a race they didn’t ask for: customers expect great mobile experiences, regulators expect better monitoring and reporting, and competitors—especially digital-native banks—keep raising the bar. At the same time, cost pressure hasn’t gone away. So for Chiba Bank, digitization isn’t a shiny add-on. It’s a way to defend deposits, serve customers faster, and run the bank with fewer friction points.

That shows up clearly in how the bank talks about itself. Chiba Bank’s market strategy puts digital transformation and diversification front and center, anchored by efforts like the ‘Chibagin App’. The message is simple: if the customer relationship is moving to the phone, the regional bank has to move with it.

Chiba backed that up structurally by creating a Group Chief Digital Transformation Officer (CDTO) role and establishing a Digital Innovation Division. That kind of org chart change is a tell. It says digital isn’t just an IT department priority; it’s become a management priority.

And, true to form, Chiba didn’t try to build the future entirely alone. Within the TSUBASA Alliance, member banks have promoted joint digital projects designed to spread capabilities across the group: building a common IT platform for new fintech services, working on cashless payment initiatives, and studying how to apply AI to banking services. The logic mirrors the alliance’s shared-infrastructure play—share the fixed costs, move faster together, and make sure smaller banks aren’t left behind by the tech curve.

International Presence

Chiba Bank also stands out in another way that doesn’t fit the usual “regional bank” profile: it has a real international footprint.

As of March 31, 2022, it operated 182 offices and three money exchange counters in Japan, plus three overseas branches in New York, Hong Kong, and London, and three representative offices in Singapore, Shanghai, and Bangkok.

For a regional bank, that reach is unusual. It positions Chiba Bank to support Japanese companies expanding abroad and foreign companies entering Japan—services that many regional peers simply can’t provide.

Chiba signaled that outward-facing ambition even earlier. In October 2014, it became the first Japanese regional bank to sell dollar bonds, issuing $300 million of notes in U.S. dollars that month. The funding mattered, but the signal mattered more: Chiba Bank could access international capital markets with a level of credibility and sophistication that most regional banks never develop.

ESG and Sustainability

Chiba Bank also began building an ESG profile earlier than you might expect. In July 2010, it joined the United Nations Environment Programme Finance Initiative (UNEP FI). It also engages in renewable energy generation and has positioned sustainability as a strategic priority.

That focus is especially meaningful in Chiba, where heavy industry—petrochemicals, steel, and manufacturing—has long been a core part of the local economy and the bank’s customer base. The energy transition creates real risk for carbon-intensive borrowers, but also a massive financing opportunity. Helping industrial clients adapt and invest requires more than commodity lending; it demands sector knowledge and long-term partnership. If Japan’s push toward net-zero accelerates, Chiba Bank’s early positioning could become a real edge.

X. Playbook: Business & Strategic Lessons

The Chiba Bank story isn’t just a Japan story, or even a banking story. It’s a set of moves that translate to any regional player staring down the same trend line: margins compress, customers go digital, and everyone tells you the only way out is to merge.

Here’s what the Chiba playbook suggests.

Lesson 1: Geography as Moat

Chiba Bank’s core advantage isn’t a product feature. It’s a pin on the map. It operates in one of Japan’s wealthiest, most economically active prefectures, sitting right next to the Greater Tokyo engine. That advantage can’t be copied with better tech, a bigger marketing budget, or a slightly higher deposit rate.

For investors, the takeaway is simple: “regional” doesn’t mean “equal.” A bank anchored in a shrinking rural area is fighting different physics than one serving Tokyo’s commuter suburbs. In Chiba’s case, the customer base and the local economy give the bank a margin for error—and a runway for growth—that many peers never get.

Lesson 2: Alliance Can Beat Merger

“There could be more harm than good in consolidating,” because when two banks merge, the integration doesn’t just happen on paper. It shows up as power struggles, slow decisions, and morale damage that can linger for years.

TSUBASA is the counterpoint. It’s proof that you can get meaningful economies of scale without welding institutions together. Shared IT. Shared compliance. Shared disaster-response capabilities. The kinds of savings and capabilities that matter—without erasing what makes a regional bank feel local.

But the nuance matters: alliances don’t work by accident. TSUBASA works because the rules reduce friction. Participation is voluntary. Geographic overlap is limited. And governance isn’t set up as one bank “running” everyone else. That design avoids the politics that often kill partnerships before the benefits show up.

Lesson 3: Local Knowledge Has Value

“All that remains is a face-to-face salesperson. Even if AI evolves, we cannot diagnose the business of SMEs.”

That line gets to the heart of relationship banking. A branch manager who’s been in the same community for twenty years doesn’t just know a customer’s balance sheet—they know the story behind it. Who pays on time when business is tight. Which manufacturer is quietly outgrowing its facility. Which family is about to hit a succession wall that could force a sale.

That knowledge is hard to digitize, and it creates real switching costs. A customer might move cash to a digital bank for a better rate. But when they need advice, restructuring help, or an introduction to a buyer, they want the institution that actually understands them.

Lesson 4: Know When to Pivot

For all its alliance-first philosophy, Chiba Bank also showed it isn’t doctrinaire. The Chiba Kogyo stake and the planned holding-company integration were a recognition that there are cases where collaboration can’t capture the full value—especially when two banks overlap in the same prefecture, serving the same customers, with duplicative footprints.

The broader lesson is flexibility. A strategy is only an advantage as long as it matches reality. When conditions change, the winners aren’t the ones with the prettiest philosophy. They’re the ones willing to adapt without losing the core of what made them strong in the first place.

XI. Porter's Five Forces & Hamilton's 7 Powers Analysis

If you zoom out, Chiba Bank’s world looks like every other bank’s world: technology is lowering barriers, customers have more choices, and the old playbook of “take deposits, make loans” keeps getting squeezed. But when you zoom back in, Chiba’s mix of geography, alliances, and relationship banking changes how those forces actually hit.

Porter's Five Forces

Threat of New Entrants: Medium-High

Starting a bank is still hard in Japan. Regulation, trust, and compliance keep the gates high. But “banking” as a customer experience has gotten easier to enter. Internet-based banks have grown by offering better apps and, especially as rates rose, more attractive deposit propositions. Players like Rakuten Bank and SBI Sumishin Net Bank have shown that if you can win on usability and pricing, you can pull deposits without needing a single branch.

Bargaining Power of Suppliers: Low

Funding sources are plentiful—capital markets and interbank lending exist if you need them. And on the vendor side, Chiba’s alliance strategy matters: TSUBASA reduces dependence on any single provider by sharing systems and, just as importantly, bargaining as a group rather than as a lone regional bank.

Bargaining Power of Buyers: Medium-Rising

Higher interest rates have started to restore the basic economics of lending. But they’ve also made customers more demanding—especially depositors. As deposits become something people shop for, competition intensifies. High-net-worth customers and SME owners have more alternatives than they used to, even if relationship banking still creates meaningful friction and loyalty.

Threat of Substitutes: High

Substitutes aren’t just other banks. They’re new ways to move money, borrow money, and manage finances: digital payments, fintech lenders, and megabank apps that keep improving. For younger customers in particular, the idea of a “main bank” is less natural, and maintaining a traditional regional bank account can feel optional.

Competitive Rivalry: Intense

The fight isn’t subtle. Megabanks have been growing deposits faster than regional banks, and digital banks keep expanding as well. Chiba’s edge is that it’s not competing from the same position as most regionals: its 36.6% lending share inside Chiba Prefecture gives it a home-market defensibility many peers simply don’t have. But it still operates in a market where the strongest players keep getting stronger.

Hamilton's 7 Powers

Scale Economies: Moderate

TSUBASA is scale without a merger: shared infrastructure, shared development, shared resources. The shared core banking system has helped member banks improve efficiency by working together rather than duplicating investments. And the planned Chiba Kogyo integration adds a more traditional layer of scale—more leverage in procurement, technology spend, and overhead—without immediately collapsing the two banks into one.

Network Economies: Moderate-Strong

With 10 banks, TSUBASA can act like a network: shared capabilities, support during disasters, and cooperation across regions. For business customers operating across multiple prefectures, there’s real value in being able to rely on relationship managers within the alliance footprint rather than starting from scratch in each place.

Counter-Positioning: Strong

Chiba’s core bet is that alliances can beat consolidation—capturing cost and capability benefits while preserving local autonomy. That model is difficult for megabanks to replicate because their advantage is centralized scale, not local intimacy. As Chiba Bank itself has emphasized, “Each region has its own history and unique industrial structure, which lenders based there know most about.” That kind of embedded local knowledge isn’t something a national bank can copy quickly.

Switching Costs: Moderate-High

For SMEs, switching banks isn’t like switching phone carriers. Credit histories are built over years. Personal relationships matter. And advisory support is often as important as the loan itself. As the bank’s view puts it: “All that remains is a face-to-face salesperson. Even if AI evolves, we cannot diagnose the business of SMEs.” That relationship-based stickiness keeps customers from moving purely for marginally better pricing.

Branding: Regional Power

In Chiba Prefecture, the name matters. More than 80 years of presence has built a level of trust and familiarity that outsiders can spend on marketing but still struggle to earn. It’s not “national brand” power—it’s something different: local credibility.

Cornered Resource: Geographic

Chiba Bank’s location is a strategic asset. Chiba Prefecture sits beside Tokyo on Tokyo Bay, anchored by major industry and connective infrastructure. Competitors can improve products and open branches, but they can’t recreate the bank’s geographic positioning in one of Japan’s most economically valuable regions.

Process Power: Emerging

Shared infrastructure is turning into operating advantage. Digital transformation initiatives, plus alliance-built compliance capabilities like the TSUBASA-AML Center, are institutional process improvements—ways to lower costs, standardize quality, and keep up with regulatory expectations without each bank reinventing the wheel.

Summary Assessment

Chiba Bank’s most durable advantages come from Counter-Positioning (alliance-first strategy), Cornered Resource (its Tokyo-adjacent geography), and Switching Costs (relationship banking). The planned Chiba Kogyo integration adds more classic Scale Economies while still protecting local presence through the holding-company approach. It’s a strong foundation—but the pressure from megabanks and digital disruptors doesn’t go away. It just raises the bar for how fast Chiba needs to keep evolving.

XII. Bull vs. Bear Case

Bull Case

The bull case for Chiba Bank is straightforward: a tough industry backdrop is finally turning, and Chiba is one of the few regionals positioned to convert that change into real advantage.

First, the end of negative rates improves the basic math of banking. After years of margin compression, rising rates have started to make it easier for banks to earn money from core lending again. Chiba doesn’t need a radical reinvention for this to matter—just a return to a world where the spread between what you pay and what you earn isn’t pinned to zero.

Second, the planned Chiba Kogyo integration would create a much larger platform. With combined assets approaching 25 trillion yen, the group would become Japan’s second-largest regional banking group. In banking, scale isn’t about bragging rights; it’s what funds technology investment, supports modernization, and spreads fixed costs over a bigger base.

Third, Chiba’s geography is a legitimate moat. Unlike regionals based in shrinking, aging prefectures, Chiba Bank operates next to Tokyo, in one of Japan’s most economically active regions—industrial, globally connected, and home to a meaningful base of affluent households and high-quality business borrowers.

Fourth, TSUBASA strengthens that advantage. The alliance is effectively a scale engine without a merger: shared systems, shared compliance capabilities, and even shared disaster-response infrastructure. Those aren’t headline-grabbing features, but they’re exactly the kinds of costs and capabilities that separate banks that can keep investing from banks that slowly fall behind.

Fifth, Chiba Bank enters this new environment from a position of relative financial strength. Its non-performing loan ratio was 0.92% as of December 2024, below the 1.6% average for large regional banks—an important cushion if competition heats up or the economy softens.

Bear Case

The bear case isn’t that Chiba lacks strengths. It’s that the forces reshaping Japanese banking are bigger than any one bank’s strategy—and even a leader can get pulled into the current.

First, demographics and competition still matter, even in Greater Tokyo’s orbit. Regional-bank deposit growth slowed to 0.9% in 2025, versus 2.7% at the megabanks. If deposits keep drifting toward megabanks and digital-native players, Chiba may feel it later than others, but it won’t be immune.

Second, digital disruption keeps accelerating. Younger customers are increasingly mobile-first, and their expectations are set by the best apps they use—often not bank apps. A dense branch network has historically been Chiba’s strength, but over time it can turn into a cost structure that’s hard to defend if customers stop showing up in person.

Third, the alliance model has natural limits. TSUBASA captures meaningful economies of scale, but it can’t capture everything a full integration can. The more pressure the sector faces, the more likely it is that some members—or competitors outside the alliance—will pursue deeper consolidation, potentially shifting the competitive baseline upward.

Fourth, rising rates cut both ways. Higher rates can lift lending margins, but they also intensify competition for deposits and can put strain on borrowers who built their finances around ultra-low rates. If faster normalization leads to credit stress, a regional bank with concentrated exposure could take outsized damage.

Fifth, there’s execution risk on the Chiba Kogyo integration. Even when the structure is a holding company and the strategic logic is clear, integration is hard: coordinating cultures, aligning systems, and retaining customers all take time—and mistakes are expensive.

Key Performance Indicators to Monitor

For investors tracking whether Chiba Bank is winning this next phase, three KPIs matter most:

-

Net Interest Margin (NIM): The spread between what Chiba earns on loans and pays on deposits. In a normalizing rate environment, NIM should have room to expand. If it doesn’t, it’s a sign either competition is biting harder than expected or Chiba is choosing not to reprice aggressively.

-

Deposit Growth Rate vs. Industry: Deposits are the franchise. Tracking whether Chiba can retain and grow deposits relative to megabanks and digital competitors is the clearest read on whether its geographic and relationship advantages are holding.

-

Cost-to-Income Ratio: Chiba’s efficiency has been a differentiator, at roughly 53% versus a 73% industry average. The key question is whether the Chiba Kogyo integration and continued digital investment improve that advantage—or dilute it.

XIII. Conclusion: The Regional Banking Survival Playbook

Regional banks and regional revitalization are joined at the hip. If the local economy weakens, the bank’s loan demand and customer base shrink with it. If the bank weakens, the region loses one of its most important engines of credit, advice, and long-term partnership. That’s why the path forward in Japan isn’t just a bank strategy question—it’s an economic strategy question.

Chiba Bank’s story offers a clear answer to a hard problem: how do you stay local in a world that rewards scale? Its bet has been that you don’t have to choose between independence and competitiveness. You can share the expensive, invisible parts of banking—systems, compliance, operations—while protecting the parts that actually create loyalty and insight: local relationships and local decision-making. That’s the core insight behind TSUBASA, and it’s why the alliance model has resonated far beyond Chiba Prefecture.

But the story also shows the limits of ideology. Alliance can be an alternative to merger, but it can’t solve everything. The planned integration with Chiba Kogyo Bank is the proof point: when two banks overlap in the same market, redundancies and competitive friction don’t disappear just because both sides agree to collaborate. Sometimes the pragmatic move is consolidation—especially if you can do it in a way that preserves customer continuity through a holding-company structure rather than a full absorption.

So the modern regional banking playbook that emerges here is blended: ally broadly where you don’t compete head-to-head, and integrate where you do.

And then there’s the factor no strategy can replace: geography. No amount of digital investment or operational excellence can fully offset the gravity of a declining market. Chiba Bank’s Tokyo-adjacent footprint—industrial, globally connected, and wealthy by regional standards—gives it a foundation many peers simply don’t have.

For long-term investors, that’s the lens. The regional banking sector can look like “deep value” when banks trade below book value. It can also be a graveyard of value traps when demographics and competition overwhelm the franchise. The difference is usually some combination of where the bank sits, how well it runs, and whether management has a credible plan for a world that keeps changing.

Chiba Bank has made a compelling case that it does. But the final verdict is still ahead. The next chapter—rising rates, intensifying deposit competition, alliance scaling, and the execution of the Chiba Kogyo integration—will determine whether this is a model other regional banks can follow, or a clever strategy that only works in one very special place on the map.

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music