Sumitomo Mitsui Trust Group: Japan's Last Independent Trust Banking Giant

I. Introduction & Episode Roadmap

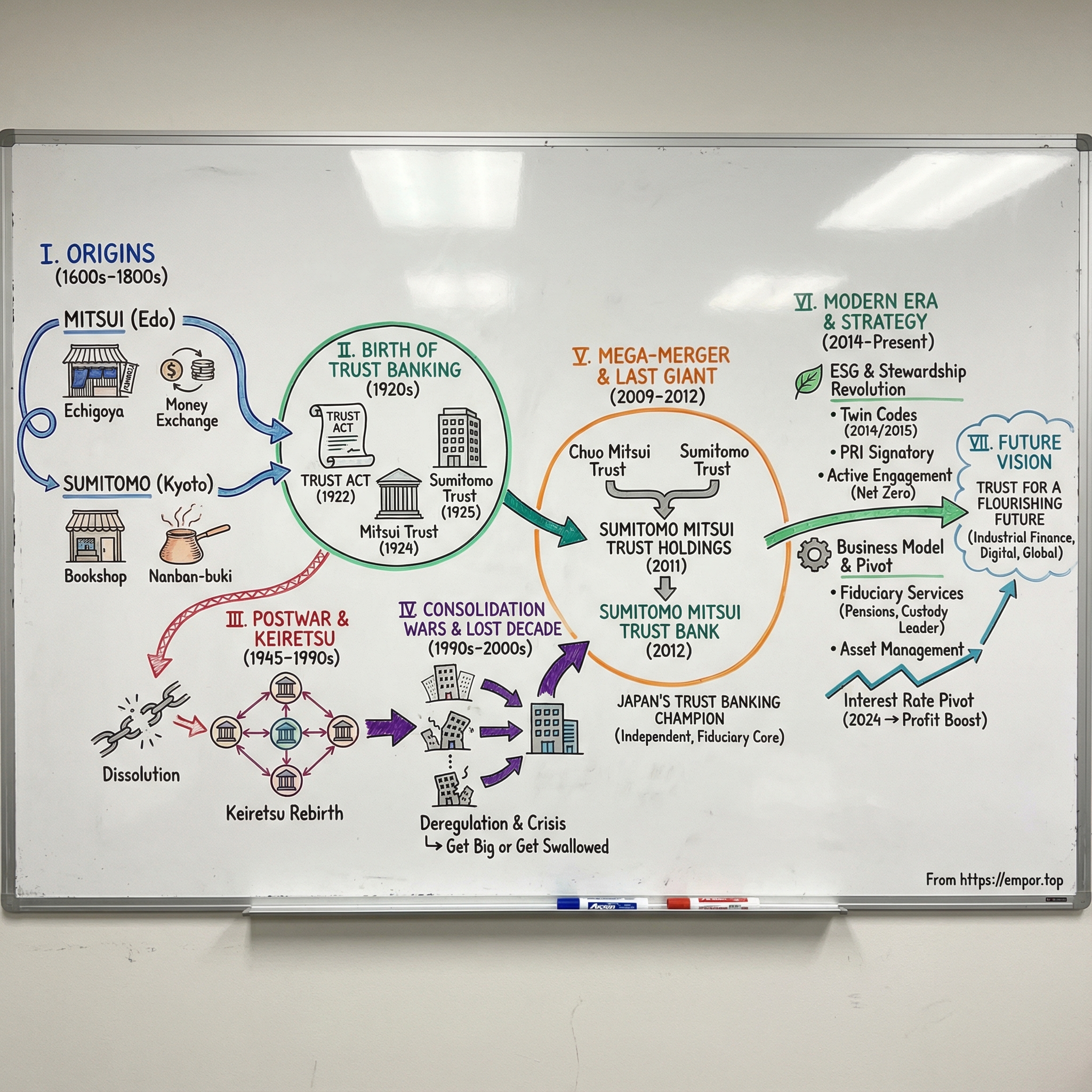

Picture yourself walking through Tokyo’s financial district on a crisp spring morning in 2024. You pass the gleaming towers of Japan’s megabanks—Mitsubishi UFJ, Mizuho, SMBC—and then you notice a different kind of name on the door: Sumitomo Mitsui Trust Bank. It’s a curious survivor. After three decades of brutal consolidation, it’s the last independent trust bank left standing. While its peers were folded into giant financial conglomerates, this one didn’t end up as a tucked-away division. It became the flagship of an entire category.

But what is a trust bank, exactly? Even seasoned investors outside Japan can get turned around here. At its core, a trust is simple in concept and demanding in practice: someone transfers property—cash, securities, real estate—to a trustee, who then manages or disposes of it according to the settlor’s instructions, for the benefit of someone else. The trustee’s job isn’t just to grow assets. It’s to do so under a fiduciary duty—an obligation to put the beneficiary first. Japan’s trust banks take that fiduciary engine and combine it with traditional banking. Think of them as hybrids: part commercial bank, part asset manager, part administrator of other people’s most sensitive financial arrangements.

For most of the postwar era, Japan’s banking system was deliberately segmented: commercial banks over here, long-term credit banks over there, trust banks in their own lane, plus mutual loan and savings banks and other specialized institutions. Those boundaries created protected territories, and trust banks could thrive without direct head-to-head competition from the biggest commercial players.

Then came deregulation in the late 1990s, and the walls came down. Commercial banks could offer trust functions, megabanks could crowd into trust products, and the standalone trust-bank model started to look like an endangered species. Most of the old trust-bank names didn’t vanish so much as they dissolved into larger organisms—becoming units inside Mitsubishi UFJ FG and Mizuho. Sumitomo Mitsui Trust Group is the lone exception: the only remaining stand-alone trust bank after that deregulation blurred the legal line between “banking” and “trust.”

And it’s not surviving as a boutique. It’s operating at national scale. As of March 2024, Sumitomo Mitsui Trust Holdings had total assets of around 75.9 trillion yen. The holding company sits atop Sumitomo Mitsui Trust Group, whose main operating engine is Sumitomo Mitsui Trust Bank, Ltd.—the largest trust company in Japan and the fifth-largest bank in the country by assets.

Now for the twist that confuses even experienced Japan watchers: despite the almost identical naming, this group has no direct capital relationship with Sumitomo Mitsui Financial Group. Sumitomo Mitsui Trust is not the trust arm of SMFG. They’re separate giants that sound like siblings because of shared ancestry—both trace back to the historical Sumitomo and Mitsui business houses that began building their power in Edo-era Japan centuries ago.

What does this trust-bank DNA buy them today? In fiduciary services, the group is Japan’s market leader in total assets under custody. It’s the largest manager of corporate pension funds in the country, and it trails only Nomura in investment trusts. In other words: if you want to understand where Japanese household wealth and institutional capital actually gets steered, you have to understand this company.

That’s the arc of this story: four centuries of Japanese business history compressed into a modern financial institution. We’ll start with two merchant dynasties that predate most modern corporations, follow the invention of trust banking in Japan, then move through postwar dissolution, keiretsu rebirth, the banking crises that forced consolidation, and the strategic decisions that let one trust bank outlast the rest. And along the way, we’ll see how an old-fashioned idea—fiduciary duty—became a launchpad for the modern stewardship and ESG era.

II. The Zaibatsu Origins: Two 400-Year-Old Business Houses

In 1622, in the small town of Matsusaka in Ise Province, a woman named Shuho gave birth to her fourth son. He was named Takatoshi. His father ran a modest shop—miso out front, pawnbroking on the side. The Mitsui family were comfortable provincial merchants, already a few generations removed from their samurai roots. Nothing about the setup screamed “future financial empire.”

But that fourth son would become Mitsui Takatoshi (1622–1694), the origin point for what would turn into one of the most influential business houses in Japanese history.

Takatoshi first went to Edo (modern Tokyo) at 14, learning the rhythms of the biggest market in the country. Later, his older brother joined him. Then, in a twist that could have ended the story early, Takatoshi was sent back to Matsusaka—effectively sidelined from the action. He stayed there for 24 years.

That long detour turned into his advantage.

While he waited, Takatoshi studied how people bought and sold, how prices moved, what customers actually wanted, and how merchants made money. So when his brother died and Takatoshi finally took over, he wasn’t just inheriting a shop. He was arriving with a playbook.

In 1673, Takatoshi returned to Edo and opened a textile store in what is now Chuo-ku called Echigoya (越後屋), the predecessor of today’s Mitsukoshi. A decade later he moved it to the site of the current Mitsukoshi main store and introduced a retail model that sounds boring now, but was radical then: cash sales at fixed prices, and goods sold by the piece.

In feudal Japan, that was a shock to the system. Traditional gofukuyas didn’t “sell inventory” the modern way. They made clothing to order. Salespeople brought cloth samples to the homes of wealthy customers, negotiated, took the order, and got paid on delivery. Takatoshi flipped that: ready-made goods, transparent pricing, cash up front, right in the store. Echigoya grew into the largest textile shop of the Edo period—and it began supplying dry goods to the Edo city government.

As the retail business scaled, Takatoshi pushed into something even more important: moving money.

He established the Mitsui Ryogaeten, a money exchange business. The timing was perfect. Regional feudal governments were increasingly paying taxes to the Edo government in cash, but physically transporting cash across Japan was dangerous. Bandits made sure of that. In 1683, the shogunate authorized money exchanges in Edo for tax payments, and Mitsui’s exchange shops became a crucial part of the system. They would accept goods and cash at regional locations and issue notes that could be redeemed for cash in Edo—reducing risk and increasing speed.

This is where the “merchant house” starts looking a lot like a bank.

Fast-forward two centuries, and that line becomes official. On July 1, 1876, Mitsui Bank—Japan’s first private bank—was founded, with Masuda Takashi (1848–1938) as president. Mitsui Bank later became part of Sakura Bank after a merger with Taiyō-Kobe Bank in the mid-1980s, and today its lineage lives on inside Sumitomo Mitsui Banking Corporation. By the early 20th century, Mitsui had become one of Japan’s dominant zaibatsu, spanning industries far beyond finance.

While Mitsui was mastering commerce and capital in Edo, a parallel dynasty was taking shape in Kyoto—built on an entirely different foundation: spirituality, philosophy, and metallurgy.

The Sumitomo Group traces its roots to around 1615, when Masatomo Sumitomo, a former Buddhist monk, opened a bookshop in Kyoto. He left behind a set of guiding principles—the “Founder’s Precepts”—written in the 17th century and still cited today as the base of Sumitomo’s business philosophy. The point wasn’t simply profit. The precepts emphasized character, gratitude, and trustworthiness.

But it wasn’t books that made Sumitomo famous. It was copper.

Masatomo’s brother-in-law, Riemon Soga (1572–1636), ran a copper refining and coppersmithing operation in Kyoto under the trade name Izumiya, meaning “spring shop.” Drawing on Western methods, he developed a refining technique known as Nanban-buki (“Western refining”), which made it possible to extract silver from crude copper—something Japanese technology hadn’t previously achieved.

The business then deepened through family ties. Tomomochi Soga (1607–1662), Riemon’s eldest son, married Masatomo’s daughter, joined the Sumitomo family, and helped expand the copper business to Osaka by the late 17th century. Sumitomo/Izumiya became so central to the craft that it was regarded as the “head family” of Nanban-buki, and Osaka rose to lead Japan’s copper refining industry.

In the Edo period, Japan was one of the world’s leading copper producers. From copper, Izumiya expanded into trading thread, textiles, sugar, and medicine—prospering so dramatically that people said, “No one in Osaka can compete.”

So by the time Japan hit the upheaval of the Meiji Restoration, Mitsui and Sumitomo weren’t just wealthy. They were institutional. They adapted from feudal-era business houses into modern industrial and financial conglomerates, and by the early 20th century they stood among the “Big Four” zaibatsu that powered Japanese capitalism until their forced dissolution after World War II.

For investors today, these four-hundred-year origins aren’t trivia. They explain something central about Sumitomo Mitsui Trust: this isn’t merely a bank that happens to offer trust services. It’s a modern financial institution built on two legacies—Mitsui’s obsession with how customers transact, and Sumitomo’s insistence that commerce only works when people believe the character of the counterparty. When your product is literally “trust,” that kind of heritage isn’t marketing. It’s strategy.

III. Birth of Trust Banking in Japan: A New Financial Invention

In 1922, Japan quietly set the stage for a brand-new kind of finance. The country was about to import a legal idea with deep British roots—the “trust”—and remake it for Japan’s own economy. The urgency would become painfully obvious a year later, when the Great Kanto Earthquake devastated Tokyo and Yokohama. But the blueprint was already being drawn.

The backstory is simple: early trust companies existed, but many were undercapitalized and unreliable. That created real damage—exactly the kind of thing that destroys public confidence in a financial system. So the government stepped in. The Trust Act and the Trust Business Act were enacted in 1922 and came into force in 1923, defining what a trust was and setting rules for how trust businesses could operate.

What’s striking is how international this “Japanese” framework actually was. The Trust Act of 1922 didn’t come out of thin air; it was drafted with reference to the Indian Trust Act and the California Civil Code, along with English case law. In other words, Japan took a mechanism born in common law—where trust concepts had evolved through courts over centuries—and engineered it into a civil-law system that didn’t have an equivalent tradition.

The Trust Business Act arrived alongside it. And for decades, the core architecture barely moved. There were effectively no major amendments to the Trust Act for more than 80 years. The original design was cautious, built with strong controls to prevent a repeat of the “minor trust company” problems that had come before. On paper, it leaned toward civil trusts. In practice—especially after World War II—the system would increasingly become a commercial engine run through trust banks.

Once the legal rails were down, the big houses moved fast.

Mitsui Trust Company Ltd. was established in March 1924 with capital of 30 million yen. It became the first trust company in Japan, commencing operations on April 15, 1924. Sumitomo Trust Co., Ltd. followed in July 1925 with capital of 20 million yen, headquartered in Awajicho, Osaka.

And then reality delivered its case study. In September 1923, the Great Kanto Earthquake killed more than 100,000 people and destroyed hundreds of thousands of buildings. Beyond the human tragedy, it exposed a fragile problem: assets can vanish overnight, records can burn, heirs can be displaced, and commercial relationships can snap. Japan needed institutions that could preserve continuity—manage property, administer estates, and keep financial life functioning through chaos. Trust banks, built around fiduciary duty, were designed for exactly that kind of long-horizon stewardship.

The founding philosophy of the early trust banks made that explicit. One historical statement put it this way: "A trust company should not be established or managed merely for the purpose of profit, and since it is based on absolute confidence and the utmost integrity, the foundation of a trust must be as strong and robust as possible... Therefore, there are no plans for our trust company to distribute dividends to shareholders for the first year or two."

That is not how speculative finance talks. It’s how institution-builders talk.

This was the pivot away from the get-rich-quick trust companies that had helped provoke regulation in the first place. The zaibatsu-backed trust banks weren’t trying to squeeze out early returns; they were trying to become the kind of counterparties you could hand your family assets to and not worry about for decades. “Absolute confidence” wasn’t a slogan. It was the product.

Structurally, trust banks were also different from ordinary banks because they had a unique dual license. In Japan, trust banks combined traditional banking with investment and fiduciary services for both corporate and individual clients. They could design and manage pension plans, broker and manage real estate transactions, act as custodians for securities, and handle the less glamorous but essential administrative work that comes with long-term asset ownership.

That hybrid model—part commercial bank, part fiduciary, part asset manager—created powerful synergies. Trust banks could participate in both indirect financing, like loans and deposits, and the growing world of direct financing through investment and asset management. For corporations and wealthy families navigating a rapidly modernizing economy, that breadth made trust banks unusually sticky partners.

And it’s why the founding era still matters when you look at Sumitomo Mitsui Trust today. When customers are trusting you with retirement funds, corporate pensions, estates, and multi-generational wealth, the thing you’re really selling isn’t a rate sheet. It’s institutional character. And in this industry, that’s an advantage that’s painfully hard for competitors to manufacture.

IV. War, Dissolution, and the Keiretsu Rebirth

In 1945, the B-29s didn’t just burn Japan’s cities. They helped bring down the economic operating system that had powered Japanese capitalism for decades. And for the great zaibatsu—Mitsui and Sumitomo included—the American occupation proved nearly as disruptive as the war itself.

During the United States occupation of Japan following World War II, the Mitsui zaibatsu was dissolved. After the war, the Japanese zaibatsu conglomerates, including Sumitomo, were dissolved by the GHQ and the Japanese government. The intervention was designed to be comprehensive: multiple zaibatsu were targeted for complete dissolution, others for reorganization. The controlling families’ assets were seized, holding companies were eliminated, and interlocking directorships—one of the quiet mechanisms that made the old system work—were outlawed.

For Mitsui Trust and Sumitomo Trust, the consequences were immediate and concrete. First came the forced name changes, meant to cut the visible ties to the zaibatsu past. In March 1948, Mitsui Trust became Tokyo Trust & Banking Co., Ltd. In 1952, it reclaimed the Mitsui name again as Mitsui Trust and Banking Company, Ltd. Sumitomo Trust followed the same arc: it became Fuji Trust & Banking Co., Ltd. in 1948, and then returned in 1952 as Sumitomo Trust and Banking Co., Ltd.

That whiplash—erase the names, then restore them—tells you two things at once: how severe the initial crackdown was, and how incomplete it ultimately became.

Because full dissolution didn’t stick. The U.S. government eventually rescinded the most aggressive orders as priorities changed. With communist China consolidating power in 1949 and the Korean War breaking out in 1950, the mission pivoted from restructuring Japan’s economy to rebuilding it—fast—as a capitalist bulwark in Asia. The Cold War, in effect, spared the zaibatsu from total extinction.

What emerged in place of the old model was the keiretsu: a looser federation of companies linked by long-term relationships and cross-shareholdings, often organized around a core bank. Keiretsu dominated much of Japan’s postwar economy. Their influence waned from the late 20th century onward, but they remained meaningful forces into the 21st.

The distinction matters. Zaibatsu were hierarchical: a controlling family sat at the top, using a holding company to coordinate a portfolio of businesses. Keiretsu were more horizontal: member companies owned small stakes in each other, with the main bank acting less like a command center and more like an organizer and stabilizer. That structure helped insulate companies from stock-market turbulence and hostile takeovers, and it favored long-term planning over short-term pressure.

In the 1950s, Mitsui reorganized as a loose conglomerate, sharing financial, logistical, and technical infrastructure. Sumitomo’s orbit re-formed as a keiretsu as well—independent companies organized around The Sumitomo Bank (now part of Sumitomo Mitsui Banking Corporation) and bound together by cross-shareholding.

For the trust banks, this shift wasn’t just survival. It was opportunity. With the old family holding companies gone, Japan needed new ways to create stability and manage long-term capital. Trust banks—with fiduciary expertise, administrative muscle, and deep experience in managing assets—fit naturally into the new system. They could manage pension funds, hold shares in custody, and provide the institutional plumbing that helped power Japan’s postwar economic expansion.

From the early 1950s through the 1990s, the keiretsu era was a favorable climate for trust banks. Licensing regimes protected their lane, business-group relationships fed them steady institutional work, and a richer Japan created more pensions and more assets to manage. Mitsui Trust and Sumitomo Trust thrived.

But the same features that made this era stable—cross-shareholdings, main-bank relationships, and a system built for continuity—also made it brittle. As finance globalized and deregulation accelerated from the 1980s into the 1990s, the keiretsu model started to look less like a fortress and more like friction. And that’s where the next chapter begins.

V. The Lost Decade and Consolidation Wars

The collapse began, as so many financial collapses do, with real estate and hubris. By the early 1990s, Japan’s asset bubble had reached surreal levels—the Imperial Palace grounds in Tokyo were famously said to be worth more than all the real estate in California. Then the bubble broke. And it didn’t gently deflate; it imploded.

What followed was not a single bad year, but a grinding, system-wide crisis. From the early 1990s through 2003, Japan’s banking sector cycled through waves of failure: first, small and mid-sized institutions started to topple; then major names began to go under in 1997; and the turmoil continued into the early 2000s with more large failures. As weak institutions became unsustainable, the industry’s endgame was inevitable: consolidation, until Japan was left with four national banks. Meanwhile, across the real economy, companies were loaded with debt and credit became harder to access at the exact moment it was most needed.

Even for the banks that survived, the environment was punishing. For almost two decades, Japanese banks operated in an ultralow interest rate world. The Bank of Japan’s Zero Interest Rate Policy was meant to fight deflation, but it also squeezed the basic economics of banking. Margins thinned, profitability became a constant struggle, and institutions were pushed to cut costs and hunt for growth elsewhere, including overseas.

The recession also tore at the keiretsu system. The old boundaries between business groups blurred as bad loan portfolios forced combinations that would have sounded impossible a few years earlier. The symbolic example is the 2001 merger that created Sumitomo Mitsui Banking Corporation—bringing together the commercial banking lineages of Sumitomo Bank and Mitsui Bank. In calmer times, that kind of marriage between historic rivals would have been unthinkable. In crisis, it became rational.

For trust banks, this era was both danger and opening. The danger was straightforward: collapsing real estate values, non-performing loans, and institutional clients fighting for their own survival. The opening came from an unexpected place—deregulation.

For decades, Japan’s financial system had been deliberately segmented. Commercial banking, trust banking, long-term credit banking, securities, and insurance were meant to be operated separately, under separate licenses. That segmentation had protected standalone trust banks. But when the walls started coming down in the late 1990s, the protection turned into a problem. Megabanks could now offer trust services too, and the trust banks’ once-exclusive lane filled up with much larger competitors almost overnight.

So standalone trust banks faced a stark choice: get bigger through consolidation, or get swallowed.

Chuo Trust and Mitsui Trust chose to bulk up. They signed a merger agreement in May 1999, completed the merger in April 2000, and became Chuo Mitsui Trust and Banking Co., Ltd. Then came the holding company step: in 2001, Chuo Mitsui announced plans for a new bank holding company, Mitsui Trust Holdings, Inc., which was formed in February 2002. This wasn’t about empire-building. It was survival architecture for a deregulated world.

They were active on the deal front too. In 1998, Chuo Mitsui acquired the Honshu operations of Hokkaido Takushoku Bank. Hokkaido Takushoku had been a major regional player before its collapse in November 1997—one of the era’s defining failures. For Chuo Mitsui, the acquisition brought branch networks and customer relationships carved out of a wreck.

Sumitomo Trust, meanwhile, took a different path. It moved through the 1990s more conservatively than some peers and kept its independence intact—quietly accumulating the stability and options that would matter later. The bank that would eventually become Sumitomo Mitsui Trust Bank was being shaped here, not by one dramatic move, but by the strategic decisions made under stress.

And zooming out, the pattern across the industry was clear. One major trust bank after another ended up inside a megabank group. Mitsubishi Trust Banking Corporation became a subsidiary of Mitsubishi UFJ Financial Group. Mizuho’s trust bank became part of Mizuho Financial Group’s structure. The standalone trust banks didn’t disappear because trust stopped mattering; they disappeared because scale and distribution started to matter more.

Only one would ultimately remain independent—not by avoiding consolidation, but by choosing the right kind of consolidation: mergers of equals, on terms that preserved trust banking as the core business rather than a side division inside a megabank.

VI. The Mega-Merger: Creating Japan's Trust Banking Champion

In November 2009, with the global financial system still shaking from the Lehman Brothers collapse, two of Japan’s old-line trust banking franchises made a move that would reshape the category. Chuo Mitsui Trust Holdings and The Sumitomo Trust and Banking Co., Ltd. agreed to merge—explicitly to create a national champion in trust banking at a moment when scale, stability, and credibility mattered more than ever.

The structure came next. In April 2011, the two sides formed Sumitomo Mitsui Trust Holdings, Inc. through a share exchange between Chuo Mitsui and Sumitomo Trust. In plain terms: they didn’t just bolt two banks together. They built a new parent company designed to give the combined group a stronger management foundation and a single strategic direction.

And the strategic logic was the point. Japan already had its megabanks—Mitsubishi UFJ, Mizuho, and SMFG—created by crisis-era combinations that prioritized breadth and balance-sheet mass. This deal was different. It was consolidation with a thesis: keep trust banking as the core identity, not an appendage. In a deregulated world where megabanks could offer trust services, the only way for an independent trust bank to stay independent was to become big enough to matter.

The operational unification arrived a year later. On April 1, 2012, Sumitomo Mitsui Trust Bank, Limited (SuMi TRUST) was established through the merger of The Sumitomo Trust and Banking Co., Ltd. with Chuo Mitsui Trust and Banking, Ltd. and Chuo Mitsui Asset Trust and Banking Company, Ltd. The result was a single institution—Sumitomo Mitsui Trust Bank, Ltd.—that became the largest trust bank in Japan and the fifth-largest bank in the country by assets.

It’s hard to overstate the symbolism here. These were descendant institutions of the Mitsui and Sumitomo business houses—names that had competed, evolved, and endured through the same four centuries of Japanese commercial history, often on opposite sides of the table. Now they were on the same letterhead. “Sumitomo Mitsui Trust” wasn’t just a merger name; it was a claim to lineage, to institutional memory, and to the one thing a trust bank ultimately sells: confidence.

The early years, though, reminded everyone that size doesn’t automatically equal steadiness. In 2012, SMTB was fined for insider trading after a Chuo Mitsui fund manager was found to have traded on information leaked from Nomura Securities regarding a 2010 share issuance by Mizuho Financial Group. It was an embarrassing episode, and a sharp illustration of how hard integration is—especially in a business where fiduciary standards are the brand.

Still, the underlying bet held. By building a standalone trust-banking champion rather than disappearing into a megabank group, Sumitomo Mitsui Trust kept control of its destiny. When corporations need a pension manager, when institutions need a custodian, when families need long-horizon asset administration, they’re not shopping for a side desk inside a sprawling universal bank. They want a counterparty whose entire operating system is designed around fiduciary work.

This is the inflection point that explains the modern company. Sumitomo Mitsui Trust isn’t simply another Japanese bank that survived consolidation. It’s the consolidator that emerged with trust banking intact as the core business—and with a scale that’s painfully difficult for any new entrant to replicate.

VII. The ESG & Stewardship Revolution

The second transformation that reshaped Sumitomo Mitsui Trust’s trajectory didn’t start with a splashy acquisition or a balance-sheet rescue. It started with a document that, at first glance, looked like committee-grade policy: Japan’s Stewardship Code.

Introduced in 2014 and updated in 2020, the Stewardship Code encouraged institutional investors to stop acting like silent owners and start behaving like stewards—engaging more actively with companies on governance and long-term value. Then came the companion reform on the corporate side. The Corporate Governance Code, established in 2015 and revised in 2021, pushed companies listed on the Tokyo Stock Exchange to improve disclosure around issues like climate-related risks and diversity.

Together, these “twin codes” created pressure from both directions at once. On the demand side, investors were expected to ask harder questions and vote with intention. On the supply side, companies were expected to open up, explain themselves, and modernize.

The Stewardship Code itself was established by a council of experts, with the Financial Services Agency serving as the secretariat. The Corporate Governance Code was established by the Tokyo Stock Exchange, also based on expert council discussions. That institutional setup mattered: this wasn’t a niche campaign by activists. It was the system telling Japan’s capital markets to evolve.

For Sumitomo Mitsui Trust—deep in the plumbing of Japan’s pensions, custody, and asset management—this was less a trend than a rerouting of the whole playing field. If you manage large pools of retirement money, you can’t just buy shares and forget them. The new expectation was that you would help shape the companies you own. Stewardship wasn’t optional; it was becoming part of the job description.

SuMi TRUST was unusually well-positioned for that shift, because it had been moving in this direction long before Japan’s codes made it mainstream. The group launched its first SRI (Socially Responsible Investment) fund in 2003 and became one of the founding signatories of the UN Principles for Responsible Investment (PRI) in 2006. That’s years before ESG became a global default setting for institutional investors.

The commitments kept stacking. SuMi Trust endorses Japan’s Stewardship Code and is a PRI signatory. In July 2021, it became a signatory to the Net Zero Asset Managers Initiative (NZAMI), committing to work toward net zero by 2050. In May 2022, in line with that NZAMI commitment, it announced 2030 interim targets for greenhouse gas emissions of assets under management—targets that only become real if you build the internal machinery to measure, engage, and, when needed, push portfolio companies to change.

And stewardship wasn’t left as an abstract principle. Following the revised Stewardship Code published in March 2020, Sumitomo Mitsui Trust Bank revised its “Guidelines on Stewardship Responsibilities,” laying out how it would fulfill those responsibilities through active engagement with investee companies.

This is where the ESG story becomes more than branding. For Sumitomo Mitsui Trust, stewardship is a competitive strategy that fits the core trust-bank identity: fiduciary duty, long-term relationships, and credibility with institutions. As Japanese companies face rising governance and sustainability pressure—and as global capital increasingly expects ESG integration—the managers with the deepest engagement capabilities gain an edge, especially in corporate pensions where fiduciary expectations have broadened and scrutiny is relentless.

In other words, ESG wasn’t a bolt-on. It was the trust business, modernized.

VIII. The Modern Business Model: What Does a Trust Bank Actually Do?

Walk into Sumitomo Mitsui Trust Bank’s headquarters in Chiyoda, Tokyo, and you’re looking at an institution that refuses to fit neatly into a Western checkbox. It’s not a plain-vanilla bank built around deposits and loans. It’s not a pure-play asset manager like BlackRock or Fidelity. And it’s not a custody bank in the narrow sense many U.S. investors would recognize. It’s something distinctly Japanese: a trust bank. And if you want to understand why this company survived consolidation—and why it still matters—you have to understand what that hybrid model really does.

At a high level, the group serves both retail and wholesale clients, with a mix that leans heavily toward asset management, financial brokerage, and real estate. That sounds broad because it is. Trust banking is less a single product than a bundle of mandates that sit at the intersection of money management, administration, and long-term fiduciary responsibility.

The heart of the machine is fiduciary services. Sumitomo Mitsui Trust Group is Japan’s market leader in total assets under custody. It’s the largest manager of corporate pension funds, and it trails only Nomura in investment trusts. That positioning is not a side business—it’s the core franchise. When major Japanese companies need a partner to manage retirement assets, administer plans, and do the unglamorous but mission-critical work that keeps pensions running, this is one of the first doors they knock on.

Then there’s the investment management arm. Sumitomo Mitsui Trust Asset Management provides services to domestic and overseas long-term investors, including pension funds, public funds, and defined contribution pensions, with total assets under management of about 85 trillion yen. That’s a massive fee-generating base—and, crucially, it’s income that doesn’t depend on whether the Bank of Japan is holding rates at zero or finally letting them rise.

On the balance-sheet side, the group is still a giant bank. As of March 2024, Sumitomo Mitsui Trust Bank was the largest trust bank in Japan by total assets, at more than 73.3 trillion yen. Sumitomo Mitsui Trust Group as a whole was the fifth-largest Japanese bank by assets and revenue, with about a 3.1% share of domestic loans.

Put those pieces together and you get the real advantage of the model: built-in diversification. For most of the last three decades, Japan’s ultralow-rate environment squeezed lending margins across the industry. In that world, fee-based businesses—asset management, custody, pensions, and real estate—helped stabilize earnings. When rates rise, traditional banking can finally breathe again. The trust bank structure is, in effect, designed to hold up across very different interest-rate climates.

One important point still trips up international investors, and it’s worth stating plainly: despite the similar name and the shared historical roots, the group has no capital ties with Sumitomo Mitsui Financial Group. This is not a subsidiary and not an integrated “trust division” of SMFG. Sumitomo Mitsui Trust Group and Sumitomo Mitsui Financial Group are separate entities that sound related because both descend—culturally and historically—from the Sumitomo and Mitsui business houses.

You can see the lingering legacy in the wider business ecosystem. Companies associated with the Mitsui keiretsu include Mitsui & Co., Sumitomo Mitsui Trust Holdings, Sumitomo Mitsui Banking Corporation, and many others. That can create relationships and referrals, but it does not mean control, and it does not mean operational integration. The trust bank is independent.

In recent moves, management has signaled that it wants to pair that domestic franchise with global capabilities. Sumitomo Mitsui Trust Holdings collaborated with Apollo to launch an alternative asset fund. The group was also involved in integrating Credit Suisse Securities’ Wealth Management Business in Japan through UBS SuMi TRUST—an arrangement that points to a recurring play: combine global investment product and expertise with local distribution and client trust.

And in October 2024, the parent company changed its name from Sumitomo Mitsui Trust Holdings, Inc. to Sumitomo Mitsui Trust Group, Inc. It’s a small wording shift, but a meaningful one: less emphasis on a corporate shell, more emphasis on a unified financial services franchise.

IX. Recent Strategic Moves & the Interest Rate Pivot

For Japanese banks, March 2024 marked the end of an era. That month, the Bank of Japan delivered its first policy rate hike in 17 years, pushing rates back into positive territory for the first time since 2016. After decades of zero and negative rates meant to fight deflation, Japan began the slow work of monetary “normalization.”

For banks, that’s a genuine regime change. Higher rates can finally widen net interest margins and lift interest income. But the tradeoffs arrive immediately: valuation losses on bond portfolios, more sensitivity to market moves, and the risk that higher borrowing costs start to stress weaker borrowers. In other words, the tide comes back in—but the rocks it reveals are real.

For Sumitomo Mitsui Trust, the early read has been encouraging. Results have been strong, surpassing the full-year forecast announced in January 2025 and reaching record-high profits. The group has benefited from a combination that suits its hybrid model perfectly: improving rate conditions on the banking side, alongside continued growth in fee-based businesses.

That momentum shows up in execution against the plan. Sumitomo Mitsui Trust has hit its KPIs for net income, ROE, and the reduction of strategic shareholdings a full year ahead of schedule—an outcome that reflects both management follow-through and a more favorable market backdrop than Japan’s banks have been able to count on for a long time.

The capital position has remained solid, too. Company presentations show a CET1 capital ratio, on a finalized Basel III fully phased basis, of 10.6% as of March 2025, rising to 10.9% as of the end of September 2025. Against that foundation, the group announced a share repurchase of up to ¥30.0 billion—less about financial engineering than a signal that management believes the balance sheet has room to return capital while staying comfortably above requirements.

Profitability is moving in the same direction. The company reached the current Medium-Term Management Plan ROE target of 8% or more in FY2024 ahead of schedule, and the revised ROE forecast for FY2025 is in the lower 9% range. The stock has been trading around 1x PBR—an important psychological level in Japan, where banks have long been priced at persistent discounts to book.

Looking forward, for the fiscal year ending March 31, 2026, the group’s consolidated forecast calls for net business profit before credit costs of ¥370.0 billion and net income attributable to owners of the parent of ¥280.0 billion. Management also expects an annual dividend of ¥160 per common share, with a stated commitment to a dividend payout ratio of 40% or above.

All of this lands with extra symbolism because the group hit a major milestone at the same time: 100 years since the founding of Mitsui Trust in March 1924 and Sumitomo Trust in July 1925. The group’s stated “Purpose” is “Trust for a flourishing future,” and it frames its ambition as accelerating the virtuous circulation of funds, assets, and capital through what it calls “Industrial Finance in the Reiwa era”—connecting individual investors and the industrial sector to support a greener, more prosperous economy.

And the strategy is broader than traditional banking. The group has positioned itself as a modern trust franchise built on legacy strengths, pairing trust-related services with digital solutions and continued innovation in digital assets. It has announced business alliances with Daiwa Securities Group in asset management and asset administration, partnerships with global alternative asset managers like GCM Grosvenor, and initiatives in impact finance for nature.

X. Playbook: Business & Strategy Lessons

The Sumitomo Mitsui Trust story leaves behind a handful of lessons that matter well beyond Japan. These aren’t motivational slogans. They’re patterns you can see playing out across a century of regulation, crisis, consolidation, and reinvention.

The Consolidation Imperative: Being the last standalone player can be a moat, not a weakness—if you get there the right way. When deregulation tears down protected lanes, the winners are often the ones that consolidate from a position of strength, not the ones forced into a rescue merger at the worst possible moment. Sumitomo Mitsui Trust’s 2012 integration was a merger of equals that created a trust-banking champion without turning trust into a side business. That’s why it kept both autonomy and identity when others became subdivisions.

Trust as Differentiation: When your product is literally “trust,” history isn’t window dressing. The Mitsui name has stood for commercial reliability since the 1600s. Sumitomo’s legacy is built on a reputation for integrity that dates back just as far. In a fiduciary business—pensions, custody, estates, long-horizon wealth—clients aren’t only buying performance. They’re buying confidence that you’ll still be competent, solvent, and careful years from now. That kind of credibility compounds over generations, and competitors can’t manufacture it on demand.

The Keiretsu Advantage: Sumitomo Mitsui Trust sits in a rare sweet spot: connected, but not controlled. It can maintain relationships across both the Sumitomo and Mitsui corporate ecosystems—exactly the kind of network that feeds pension mandates, custody relationships, and wealth management clients—without being a subsidiary executing a parent group’s priorities. That independence is strategic flexibility disguised as corporate genealogy.

Regulatory Arbitrage: The late-1990s deregulation that wiped out many independent trust banks also created the opening for a new leader. When barriers fall, scale and speed suddenly matter. The institutions that are ready to consolidate can turn disruption into permanent market position. Sumitomo Mitsui Trust’s leadership in custody and pension management didn’t happen in spite of deregulation; it happened because the new rules let the strongest consolidator gather the category’s best assets while others fell behind.

ESG as Strategy: First-mover advantage in responsible investing isn’t about headlines—it’s about capability-building. By launching an SRI fund early and becoming a PRI signatory in 2006, the group built the teams, processes, and institutional muscle memory long before ESG became table stakes. So when large asset owners like GPIF and other pension pools began pushing ESG integration, SuMi TRUST wasn’t scrambling to comply. It was already operating that way.

The Digital Challenge: The transformation still isn’t finished. Even with partnerships—like working with SBI Sumishin Net Bank—and continued investment in fintech, the risk from digital disruption remains real. Trust banking looks like a relationship business, and it is. But platforms can unbundle distribution, compress fees, and change what clients expect from reporting, onboarding, and product access. Even a century-old franchise has to keep earning the right to be the trusted intermediary.

XI. Porter's 5 Forces & Hamilton's 7 Powers Analysis

To see why Sumitomo Mitsui Trust has been able to hold its ground—while so many former peers got absorbed—it helps to step back and run the business through two frameworks: Porter's view of industry structure, and Hamilton Helmer’s view of what creates durability.

Porter's 5 Forces Analysis:

Threat of New Entrants: LOW

Japan’s financial system was built on segmentation: commercial banking here, trust banking there, each with its own licensing regime. Even after deregulation blurred those lines, trust banking still isn’t something you can “just start.” Regulators need to approve you, you need serious capital, and you need capabilities that take years to build: custody plumbing, fiduciary controls, investment operations, and a compliance culture that can withstand scrutiny. Most of all, you need institutional relationships—pension sponsors and corporations don’t hand over retirement assets to newcomers. The late-1990s deregulation didn’t invite a wave of fresh trust-bank competitors. It mostly cleared the board and pushed the survivors into consolidation.

Supplier Power: LOW to MEDIUM

For a trust bank, the key inputs are people and technology. Talent is the bigger pressure point: Japan’s labor market is tight, and SuMi TRUST competes with megabanks and global asset managers for investment professionals, relationship managers, and compliance specialists. Still, the trust-bank franchise offers something many competitors can’t: stability and prestige in a fiduciary business, which attracts professionals who want a long-term institutional platform. On technology, vendors have some leverage, but not dominance—most systems have multiple viable suppliers.

Buyer Power: MEDIUM

The largest buyers—corporate pensions and other institutional clients—have real negotiating leverage, and fee pressure has been persistent across the industry. They can rebid mandates, compare managers, and push pricing down. But in the trust world, switching is never as simple as “sell and buy someone else.” Custody and pension administration come with operational complexity, transition risk, and internal governance requirements. That creates meaningful friction. For individuals, bargaining power is generally lower, especially in services like estate planning and settlement, where trust and continuity matter and switching can be disruptive.

Threat of Substitutes: MEDIUM and RISING

Substitution pressure has been climbing. Passive products can replace active investment trusts. Digital wealth tools can replace some forms of branch-based financial planning. But many of the services that define trust banking are stubbornly difficult to digitize away—pension administration, custody, estate settlement, and parts of real estate and securitization work are operationally complex and compliance-heavy. Tech can nibble at the edges; it’s harder to replace the core.

Competitive Rivalry: MODERATE

Standalone trust-bank rivalry has largely been settled by consolidation—SuMi TRUST is the only independent player left. The real competition comes from trust subsidiaries inside the megabanks (Mitsubishi UFJ Trust, Mizuho Trust) and from securities firms in specific arenas (Nomura in investment trusts). Competition is sharp in fee businesses, but the overall structure is oligopolistic rather than cutthroat, which tends to keep rivalry from becoming value-destructive.

Hamilton Helmer's 7 Powers Analysis:

Scale Economies: PRESENT — Custody and administration have large fixed costs in technology, security, and compliance. Scale lets those costs be spread over a bigger asset base, lowering unit economics. Asset management benefits similarly through research and platform costs.

Network Effects: LIMITED — This isn’t a social network or payments loop. Still, there’s a softer form here: custody and institutional servicing create operational integration, and that integration increases inertia.

Counter-Positioning: PRESENT — SuMi TRUST’s trust-first identity is the point. Megabanks offer trust services, but their trust units live inside organizations optimized for commercial banking priorities. Re-orienting the whole institution around trust would be disruptive and would collide with how megabanks allocate resources and measure success.

Switching Costs: HIGH — Pensions, custody, and estate relationships don’t move casually. Transferring a pension mandate can require approvals, planning, reporting changes, and notifications. The operational risk alone deters frequent switching.

Branding: STRONG — In a fiduciary business, brand is not aesthetics; it’s risk management. The Sumitomo and Mitsui names carry centuries of association with commercial reliability and integrity, and that matters when clients are handing over sensitive assets and long-term responsibilities.

Cornered Resource: LIMITED — There isn’t a single legally exclusive asset that competitors can’t touch. But the combination of leadership in custody and pensions, deep institutional relationships, and a century of trust-banking history creates a position that is hard to reproduce from scratch.

Process Power: PRESENT — The unglamorous operational routines—how you administer pensions, run custody safely, manage conflicts, and execute fiduciary duties at scale—are learned over decades. Those processes are difficult to observe from the outside and even harder to replicate.

Competitive Comparison:

Relative to megabank trust subsidiaries, SuMi TRUST gets a major advantage from organizational focus: trust banking isn’t competing internally with giant commercial banking divisions for attention and investment. Relative to Nomura and other securities firms, SuMi TRUST has the embedded institutional relationships, custody capabilities, and banking functions that pure-play securities houses don’t.

Key KPIs for Investors:

To track whether the trust franchise is strengthening or slowly leaking share, three metrics do most of the work:

-

Assets Under Fiduciary / Assets Under Custody Growth: This is the heartbeat of the trust model—more assets generally mean more fee opportunity and deeper client entrenchment.

-

Fee Income as a Percentage of Total Revenue: The higher this is, the less the business lives and dies by interest rates, and the more resilient the earnings profile tends to be.

-

ROE Progression: Management targeted 8%+ and reached it ahead of schedule. The key is whether it can sustain improvement without taking on hidden risk.

Material Risks and Regulatory Considerations:

One recurring overhang is Japan’s continued push on corporate governance and cross-shareholdings. Listed companies are expected to explain and justify strategic shareholdings, and SuMi TRUST has committed to reducing them. Unwinding those positions can create volatility in reported results as gains and losses are realized.

Interest rate risk is also a double-edged sword. Higher rates can lift banking margins, but they can also pressure the value of bond holdings. As Japan normalizes monetary policy, the bank’s securities portfolio positioning and hedging approach matter more.

And then there’s the category-defining risk for a trust bank: compliance. The 2012 insider trading incident remains a reminder that operational failures can do more than trigger fines—they can damage the credibility that the entire franchise depends on.

Put it together and you get a clean framing.

The bull case is a powerful combination: interest rate normalization improving banking profitability, plus demographic tailwinds supporting pensions and wealth management, plus ESG capability that can attract mandates from institutions that increasingly demand it.

The bear case is the slow squeeze: fee compression in asset management, gradual client migration to lower-cost or digital alternatives, and the possibility that Japan’s move away from ultra-low rates stalls or reverses—taking away the tailwind that has helped results.

For long-term investors, what makes Sumitomo Mitsui Trust unusual is that it’s a category leader in a business where trust is both the product and the moat. The consolidation era removed much of the old fragmentation. The remaining question is execution: whether management can keep modernizing—especially digitally—without diluting the fiduciary discipline and fee-based strengths that made this franchise worth owning in the first place.

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music