Sanrio: The $10 Billion Kawaii Empire

I. Introduction & Episode Roadmap

The silence speaks volumes. Or rather: the absence of a mouth does.

In a universe of character IP where everyone is performing—Mickey wisecracks, Pikachu announces itself, Elsa belts stadium-ready anthems—Hello Kitty has stayed conspicuously mute for half a century. No grin. No frown. No punchlines. Just a simple face and a bow.

That spareness isn’t an accident. It’s the whole trick.

Because Hello Kitty doesn’t tell you what she’s feeling, she lets you decide. Her vague backstory and minimal expression make her portable across cultures and eras—less a “character” than a mirror. As University of Hawaii anthropologist Christine Yano puts it: “She is so unspecific that, that kind of what might be called a blankness can respond to whatever is needed at the moment—the flexibility to kind of be everywhere, be anyone, be anything.”

And that one creative constraint—no mouth—may be among the most lucrative design choices in consumer history. By 2021, Statista ranked Hello Kitty as the world’s second-highest-grossing media franchise, behind Pokémon and ahead of giants like Mickey Mouse and Star Wars. A 2022 Forbes report estimated she had generated $84.5 billion worldwide.

But here’s the twist: the company behind this cultural juggernaut nearly fell apart.

By the late 2010s, Sanrio was running out of momentum. Operating income slid from its 2014 high of 21 billion yen to 2.1 billion yen by 2020, and the company posted its first loss in two decades in 2021. Sales declined year after year. Stores closed. The licensing machine that once couldn’t keep up with demand had slowed to a crawl. The founder—now in his nineties—was still at the center of the company. And the succession plan had already been shaken by sudden tragedy.

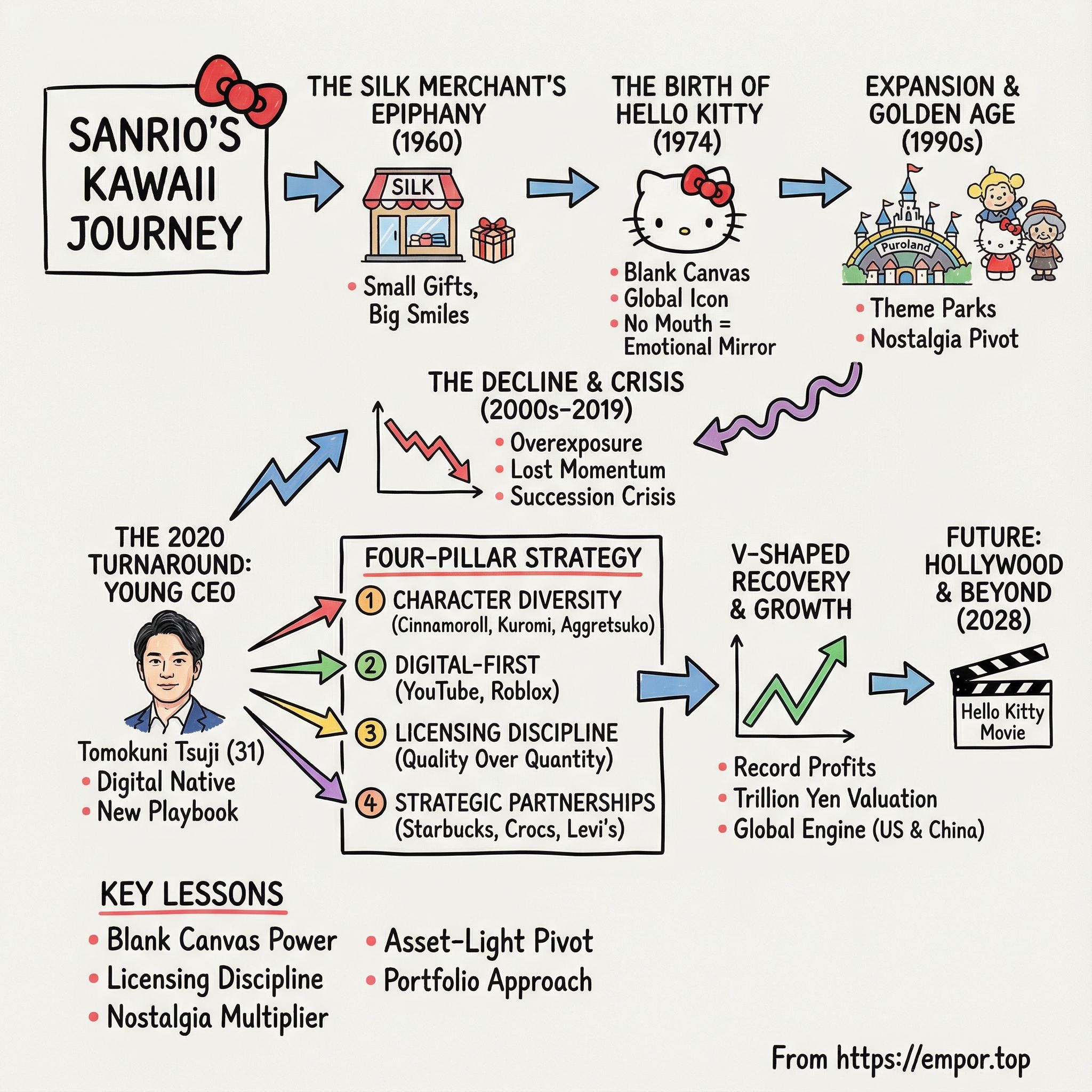

Then, in 2020, Sanrio did something it had essentially never done: it handed the keys to a new generation. Tomokuni Tsuji, the grandson of founder Shintaro Tsuji, became CEO at 31—Japan’s youngest chief executive of a publicly traded company.

What happened next was a modern turnaround in fast-forward. In the fiscal year ending March 2025, Sanrio posted record results: sales jumped 45% to 144.9 billion yen, and operating profit nearly doubled to 51.8 billion yen. Compared to fiscal 2021—when the company was still in the red—revenue was roughly three-and-a-half times larger. The market value swelled to about 1.6 trillion yen, roughly twelve times what it had been just four years earlier.

So how did a company that began life in 1960 as a Japanese silk business end up building one of the most valuable IP portfolios on Earth? How did a mouthless cat, created by a young designer in the 1970s, become a global symbol? And how did a 31-year-old CEO pull Sanrio back from the edge in a world that had moved from malls to phones?

To get there, we need to rewind—back before the bow, before the theme parks, before the collabs—and start with a simple idea: small gifts, big smiles.

II. Founding Story: The Silk Merchant's Epiphany (1960–1973)

The Orphan Who Understood Loneliness

Sanrio starts in an unexpected place: not with cuteness, but with loneliness.

Shintaro Tsuji was born in 1927 in Kofu, Yamanashi Prefecture. He grew up in a wealthy family connected to the Saegusa clan, but his early life wasn’t warm or carefree. His mother died of leukemia when he was young, and he was left in the care of an aunt who abused him. Money was there. Comfort wasn’t.

That combination—privilege on the outside, isolation on the inside—left a mark. Years later, Tsuji would describe Sanrio’s purpose in almost utopian terms: to build a “peaceful culture” and help people become friends. The company’s guiding idea, “みんなnakayoku” (“getting along together”), wasn’t marketing copy. It was the mission.

In the immediate postwar years, Tsuji studied chemical engineering at Kiryu Technical College from 1945 to 1947 and learned how to make things with his hands. He also learned how to hustle. Japan was short on everything, and he would later leverage that shortage environment by making goods for the black market—scrappy, morally gray, and very much the reality of survival in that era.

After a stretch working as a government bureaucrat, Tsuji noticed something that bothered him: most of his son’s kindergarten classmates weren’t receiving birthday gifts. To him, that wasn’t just about money. It was about connection—kids being seen, celebrated, included. He began to imagine a business built around gifting as a social glue for a country still crawling out of the devastation of war.

In August 1960, he made it real. He established Yamanashi Silk Center Co., Ltd., the predecessor to Sanrio.

The Strawberry Revelation

When Tsuji founded the company on August 10, 1960, it operated as the Yamanashi Silk Company, launched with ¥1 million in capital. It sold silk products—respectable, practical, and a million miles from what Sanrio would become.

Then, in 1962, he tried something small that turned out to be everything. He expanded beyond silk into rubber sandals and painted flowers on them. Nothing about the sandals improved. The quality didn’t change. The function didn’t change.

But they sold far better than the plain ones—by his observation, about seven times better.

That was the epiphany: people weren’t just buying objects. They were buying feeling. Utility was interchangeable. Emotion wasn’t.

Tsuji would later explain it with disarming simplicity: “There’s nothing very special about the products. It’s things that you might use in your daily lives, like a lunchbox or little pouches to store stuff. But it’s always surrounding you, close to you in your daily life. Therefore, they connect to your memories.”

This became the blueprint: take ordinary items and make them meaningful through design.

The Snoopy Lesson

In the 1960s, Sanrio leaned on a proven hit: Snoopy. Peanuts moved product. It worked.

But the economics didn’t. Royalty fees added up, and eventually the cost of borrowing someone else’s beloved character became too high. Tsuji’s takeaway was blunt and strategic: if Sanrio wanted durability, it needed to own the characters that powered the business.

So he hired designers and began building original IP in-house. The first Sanrio-created character, Coro Chan, debuted in 1973.

Coro Chan didn’t break out. The public didn’t latch on.

Still, it wasn’t wasted. The point wasn’t that Coro Chan would be the icon. The point was that Sanrio now had the capability: a pipeline for creating proprietary characters and turning them into products.

That same year, the company made another identity-level shift. In 1973, it officially changed its name from Yamanashi Silk Center to Sanrio—combining “San” (three in Japanese) and “rio” (Spanish for river), a symbol of communication and connection flowing through gifts.

By the mid-1970s, the ingredients were finally assembled: a philosophy built on friendship, a business model built on emotional design, and an in-house team learning how to create characters Sanrio could actually own.

All that was missing was the one character who could carry it worldwide.

III. The Birth of Hello Kitty & The Kawaii Revolution (1974–1989)

A Designer, A Purse, And A Mouthless Cat

In 1974, Sanrio handed a simple assignment to a young in-house designer: make a new character.

Yuko Shimizu, then 22, sketched a white cat with a red bow, a few whiskers, and an almost unnerving restraint: no mouth. Early on, she was just “Unknown White Cat.” Soon, she’d become Hello Kitty—officially Kitty White.

From the beginning, Sanrio treated Kitty less like a Japanese cartoon and more like a tiny, export-ready citizen of the world. In her backstory, she isn’t Japanese at all. She’s British: a white, anthropomorphized cat-girl living in suburban London with her family, close to her twin sister Mimmy, who wears a yellow bow.

Even the name was engineered to fit the company’s mission. Shintaro Tsuji wanted a greeting baked right into it—“Hi Kitty” was floated before “Hello Kitty” won out—because Sanrio wasn’t just selling products. It was selling connection.

And Britain wasn’t an accident, either. In 1970s Japan, British culture was in vogue. Sanrio also already had characters set in the United States, so making Kitty British helped her stand out in a growing cast.

Hello Kitty’s first product arrived in 1975: a small vinyl coin purse. She was printed sitting between a bottle of milk and a goldfish bowl. The purse cost 240 yen—around a dollar at the time. Almost nothing about it screamed “future icon,” and yet it was the opening note of what would become one of the most valuable character franchises ever created.

The Blank Canvas Philosophy

Hello Kitty’s missing mouth wasn’t a mistake. It was the strategy.

With so little expression and so little story, Kitty could slip into almost any context without friction. Christine Yano, the anthropologist who has studied the phenomenon, captured it perfectly: “She is so unspecific that, that kind of what might be called a blankness can respond to whatever is needed at the moment—the flexibility to kind of be everywhere, be anyone, be anything.”

Most famous characters arrive pre-loaded with personality. Mickey is upbeat. Garfield is sarcastic. SpongeBob is relentlessly optimistic. Hello Kitty is… whatever you bring to her. She functions like an emotional blank canvas: if you’re happy, she’s happy with you; if you’re sad, she keeps you company without forcing a smile.

Shintaro Tsuji later explained the logic in human terms: Kitty wasn’t given a mouth because she “speaks from the heart” and isn’t tied to any one language. In other words, she could travel—across cultures, across ages, across moods—without ever needing translation.

Going Global

Sanrio didn’t keep her in Japan for long.

In 1976, the company opened a gift shop in the United States. Hello Kitty came with it, and the expansion was a jolt: her arrival helped increase Sanrio’s sales sevenfold. The playbook was taking shape early—use physical retail as a billboard, a showroom, and a community hub all at once. The store wasn’t just where you bought the merch. It was where you stepped into the world.

Hello Kitty’s profile rose beyond commerce, too. In 1983, she became the United States UNICEF Children’s Ambassador. In 1994, the Japan Committee for UNICEF appointed her a Children’s Goodwill Ambassador.

And then Sanrio made a move that, on paper, made no sense for a “character goods” company: it went into film. Who Are the DeBolts? And Where Did They Get Nineteen Kids?—a 1977 documentary about an American couple who adopted 14 children, including children with severe disabilities and war orphans—won the Academy Award for Best Documentary in 1978.

It’s hard to imagine a sharper contrast: a company famous for kawaii characters backing an Oscar-winning documentary about adoption and hardship. But it also revealed something consistent about Tsuji’s worldview. Sanrio, to him, was never supposed to be just trinkets. It was supposed to be a vehicle for empathy and connection.

Building the Character Roster

Even as Hello Kitty broke out, Sanrio kept building. Through the late 1970s and 1980s, the company expanded its roster with characters like Little Twin Stars and My Melody—different vibes, different audiences, the same underlying design philosophy.

Over time, that strategy compounded into a huge owned-IP portfolio: more than 400 kawaii characters, typically minimalistic, largely 2D, and deliberately adaptable. They could live on a pencil, a purse, a lunchbox, or eventually a screen—almost any product, any channel, any market.

That breadth mattered. One day, Sanrio would learn what happens when you lean too hard on a single icon. The characters waiting in the wings would become essential.

By the late 1980s, Sanrio had done something rare: it didn’t just ride a trend. It defined one. It owned the IP, it understood distribution, and it had learned how to manufacture emotional meaning at scale.

The next step was obvious.

If you can make “cute” this powerful on a coin purse, what happens when you build a whole world people can walk into?

IV. Theme Parks & The First Golden Age (1990–1999)

Building A Kawaii Disneyland

If Sanrio could turn a coin purse into a phenomenon, the next question was inevitable: could it build a place you’d travel to just to be inside the characters’ world?

On December 7, 1990—Shintaro Tsuji’s birthday—Sanrio opened Sanrio Puroland in Tama New Town, Tokyo. It was essentially “Hello Kitty Land”: an indoor theme park built around Sanrio characters, with rides and attractions, live shows, shops, and restaurants—very much in the mold of a Disney park, just filtered through kawaii.

It was also an outright dare. Puroland was widely seen as a bold attempt to go up against the Walt Disney Company and its theme parks.

Sanrio didn’t dabble, either. The investment was enormous: a total budget of about $680 million, which would be well over a billion dollars in today’s terms. For a company best known for character goods, it was a huge bet that cute could become destination entertainment.

Making the park indoor was a strategic choice. Tokyo’s weather and real estate constraints made an enclosed footprint practical, and it allowed Sanrio to control every detail of the experience—the lighting, the colors, the atmosphere. Puroland also arrived with a fun piece of trivia: it was the second indoor theme park in the world, after Lotte World in Seoul.

Construction took roughly two years and about 2,500 workers. And then, almost immediately, Puroland ran headfirst into macroeconomics. It operated at a loss in its early years, hit by the aftereffects of Japan’s asset price bubble and the collapse that followed. The timing was brutal: the bubble burst essentially right as Puroland opened, ushering in what became known as the Lost Decade. Discretionary spending tightened, and Tokyo Disneyland—already a juggernaut—didn’t exactly get less competitive.

Sanrio doubled down anyway. In 1991, it opened Harmonyland, an outdoor theme park in Oita Prefecture—another major fixed-cost commitment during a recessionary stretch.

Still, Puroland eventually found its audience. Today it draws more than 1.5 million visitors a year and ranks among Japan’s major theme parks, alongside both Tokyo Disney Resort parks and Fuji-Q Highland.

The Nostalgia Pivot

At the same time Sanrio was building physical worlds, it made an even more important move in the emotional world of its customers.

Hello Kitty had started as a character for pre-teen girls. But in the 1990s, Sanrio began pushing her toward teenagers and adult women, reframing Kitty as something retro—something you could “come back to.”

The insight was simple and sharp: don’t abandon your original fans as they grow up. Grow with them.

The girls who once carried Hello Kitty pencil cases could now carry Hello Kitty handbags. The brand became a bridge between childhood and adulthood—nostalgic, a little ironic, and suddenly fashionable.

By the late 1990s, that repositioning went global. In the United States, Hello Kitty products landed in a wide range of department stores, and celebrities began adopting her as a statement. Mariah Carey was one of the most visible. When she was photographed wearing Hello Kitty merchandise, Kitty’s image took on a new kind of cultural credibility: no longer just cute, but cool—an accessory you could wear knowingly.

By Hello Kitty’s 25th anniversary in 1999, Sanrio hit peak turnover of ¥150 billion. The formula seemed unbeatable: minimalist characters that traveled anywhere, nostalgia that kept older fans buying, celebrities that turned “kids’ merch” into fashion, and a licensing engine that could scale worldwide.

It was a brilliant model.

And it was about to start breaking.

V. The Long Decline: 2000–2019

The First Cracks

At the turn of the century, the warning signs weren’t dramatic. They were… rankings.

In market surveys, Hello Kitty had slipped to third in popularity—a position she’d been stuck in since 2002—behind Anpanman and Pokémon. Even more unsettling, the same research suggested Sanrio was at risk of being overtaken by smaller rivals, like San-x. Their relaxed bear character Rilakkuma was climbing fast, sitting in fifth.

Hello Kitty had once been Japan’s top-grossing character. But by 2002, she’d fallen off the peak—and she never climbed back.

One major culprit was the thing that had made Sanrio so much money in the first place: overexposure. Analysts began describing a Sanrio “crisis,” arguing that Hello Kitty had become too omnipresent. Naohiro Shichijo, a professor at Waseda University, put it in almost rule-of-thumb terms: Sanrio had once been careful not to let the Hello Kitty phenomenon “get out of hand,” because if you want longevity, you can’t let a character become too popular.

This is the dark side of licensing: success creates ubiquity, and ubiquity creates fatigue. When Hello Kitty showed up on everything—across every category, in every context—her meaning thinned out. The icon started to feel less like a special signal and more like background noise.

Even inside Sanrio, the concern was becoming explicit. Yuko Yamaguchi, Hello Kitty’s longtime designer, said it plainly: “We badly need something new. The characters take a long time for development and introduction in different markets, but Kitty was so popular that it has obscured all our other efforts.”

In other words: the flagship had become the fog.

The 2014 Strategic Misfire

By 2014, Sanrio was staring at a hard tradeoff.

Licensing had made the company huge, but it also meant giving up control—over quality, over distribution, and over how the brand showed up in the world. Management decided the answer was to pivot away from licensing and toward selling more of its own merchandise directly.

Investors hated it.

The shift triggered Sanrio’s biggest stock drop in 19 years and erased nearly $450 million in market value. The market reaction wasn’t subtle, because the logic wasn’t complicated: licensing is asset-light and high-margin. Building a direct merchandise machine means inventory risk, retail operations, and working capital. Sanrio wasn’t just changing strategy—it was choosing a tougher business.

The Succession Crisis

Then the company suffered a blow it couldn’t spreadsheet its way around.

In November 2013, Kunihiko Tsuji—the founder’s son and the heir apparent—died suddenly of acute cardiac failure while on a business trip to Los Angeles. He was 61, and he’d worked alongside his father, Shintaro, for more than 35 years.

Kunihiko wasn’t just next in line. He was central to how Sanrio operated, especially overseas. He had shaped the company’s licensing policies and helped drive international expansion, including bringing in Rehito Hatoyama to push the business outward. After Kunihiko’s death, that center of gravity disappeared. Unlike Disney—built to keep expanding regardless of any one executive—Sanrio’s momentum depended heavily on the people at the top.

The loss created a vacuum: personal, strategic, and structural.

For the next seven years, Shintaro Tsuji—now deep into his nineties—kept running the company. In Japan, that kind of extended founder rule isn’t unheard of. But while leadership stayed the same, the world didn’t. And the problems kept stacking.

Finally, on July 1, 2020, Sanrio made its first leadership change in its 60-year history. Shintaro handed the reins to his grandson, Tomokuni Tsuji, who became president and CEO at 31.

The Downward Spiral

Tomokuni didn’t inherit a gentle handoff. He inherited a slide.

Even before the coronavirus pandemic pummeled retail, Sanrio had already posted consecutive years of slumping revenue. Between 2016 and 2020, overall revenue fell by nearly 16%. Sales dropped again between fiscal years 2018 and 2019, with declines across regions.

The deeper issue wasn’t a single bad year—it was the structure of the business. Overseas, Sanrio leaned heavily on Hello Kitty. In Japan, it leaned heavily on merchandise. Meanwhile, entertainment was going digital: characters were being discovered through games, streaming, apps, and social platforms, not just store shelves. Sanrio hadn’t adapted fast enough. It hadn’t developed enough new breakout characters, and its brand had been diluted by years of too-broad licensing.

By this point, the market valued Sanrio at about $1.4 billion—a reflection of a company still acting like it was the 1990s, in an era that had already rewritten the rules for media and IP.

Sanrio, the pioneer of character licensing, was now watching competitors—Pokémon, Disney, and even smaller players like San-x—pull ahead. The digital revolution had arrived, and Sanrio was still built around physical goods sold through physical stores.

By 2020, the company reported its first loss in two decades.

Something had to change.

And it would—through a 31-year-old grandson, stepping into the role at the exact moment the old playbook finally stopped working.

VI. The 2020 Turnaround: Japan's Youngest CEO

The Digital Native Takes Charge

When Tomokuni Tsuji became president and CEO of Sanrio in 2020, he instantly made headlines: at 31, he was Japan’s youngest chief executive of a publicly listed company. He was also the founder’s grandson—walking into a business that had been family-run, founder-led, and increasingly stuck.

The timing was brutal. COVID-19 slammed the exact parts of Sanrio that still mattered most: physical retail and theme parks. Sanrio Puroland shut down after closing in February, and merchandise sales dropped. For the year ended March, net profit collapsed to 191 million yen, down 95% from the year before. Sales fell 6.5%. The old Sanrio machine—stores, goods, foot traffic—had seized up.

But that same crisis created a rare opening. When the world has changed overnight, “we’ve always done it this way” stops being an argument. In that kind of moment, you can redraw the map.

Tomokuni put his new direction plainly: “Rather than focus on character goods, I want to grow the company into one that takes a broad view of global entertainment and provides value to all people.”

That was the line in the sand. Sanrio would stop acting like a merchandise company that happened to own characters, and start acting like an entertainment company that monetized those characters everywhere.

Fighting The Old Guard

Changing a 60-year-old company is rarely about strategy decks. It’s about people, habit, and internal gravity. Tsuji ran into resistance, especially from inside the organization. What made the difference was that his grandfather ultimately backed him to lead in his own way—giving the new CEO room to make moves that would normally be politically impossible.

“It’d be a lie if I said there was no pushback. But to reform a 60-year-old company, we couldn’t change based on what we already knew,” he said. “So I brought in external people with new and different knowledge and expertise, and explained to existing staff why they were needed to carry out our reforms—and they started to understand.”

A digital native, Tsuji accelerated Sanrio’s online shift: pushing e-commerce through major portals and putting the characters where younger fans actually spend time—on social platforms. He also streamlined Sanrio’s sprawling product approach, tightened focus on the asset-light franchise and royalty model, and improved efficiency. The result was a healthier business shape: less clutter, better margins, and earnings power that started to look nothing like the late 2010s.

The Four-Pillar Transformation

Tomokuni’s turnaround centered on four big moves.

1. Character Portfolio Diversification

Sanrio’s biggest strength had become its biggest vulnerability: Hello Kitty was so dominant that the rest of the roster couldn’t breathe. Tsuji pushed other characters forward—Cinnamoroll, Kuromi, and Aggretsuko in particular. Aggretsuko resonated with younger audiences globally, helped by its reach on Netflix. The point wasn’t to replace Kitty. It was to stop asking one character to carry an entire corporation.

And the shift showed up in the mix. In the fiscal year ended March, Hello Kitty represented around 30% of Sanrio’s gross profit from product sales and licensing—down from 76% a decade earlier. The business moved from over-concentrated to diversified.

2. Digital-First Strategy

There’s a structural difference between Sanrio and most Western character giants: Sanrio’s characters typically don’t originate from blockbuster movies or long-running TV series. That gives enormous flexibility—characters can be placed anywhere—but it also creates a problem in markets like the U.S., where story often drives fandom.

So Sanrio went grassroots. Instead of waiting for a Hollywood-sized narrative vehicle, it built character familiarity through short, story-driven digital content—especially on YouTube and social media—fast, cheap, and repeatable.

It scaled. Sanrio’s “Hello Kitty and Friends” YouTube channel has grown to more than 3 million subscribers. The company also expanded into Roblox, strengthening recognition with young audiences in the U.S. and Europe by letting fans interact with the characters, not just buy them.

3. Licensing Discipline

One of the reasons Hello Kitty had dulled in the 2000s was simple: she was everywhere. Sanrio had to relearn an old truth of character IP—scarcity and quality matter.

So instead of signing every deal that came in, the company got far more selective. The top 20% of partners became “key licensees,” with deeper collaboration on product quality, launches, and marketing. The goal wasn’t fewer products for the sake of it. It was protecting the meaning of the brand.

4. Strategic Brand Partnerships

At the same time, Sanrio leaned into partnerships that created cultural moments, not just more SKUs. Collaborations with major brands like Starbucks, Crocs, and Levi’s kept Hello Kitty visible year-round while maintaining a sense of novelty through limited-edition releases.

The V-Shaped Recovery

The turnaround wasn’t subtle. Operating profit rebounded to 2.5 billion yen in 2022, rose to 13.2 billion in 2023, and reached 27 billion in 2024, with expectations of further growth.

Analyst Yasuki Yoshioka called it a “beautiful V-shaped recovery,” and the market agreed: Sanrio’s stock value climbed beyond one trillion yen. In market-cap terms, the company went from roughly $1.4 billion in 2020 to more than $10 billion by late 2024.

Sanrio didn’t just get healthier. It became a different kind of company than the one Tsuji inherited—less dependent on malls, less dependent on a single character, and far more built for a world where fandom is created on screens and monetized everywhere.

VII. The North American Resurrection

From Basket Case to Growth Engine

The turnaround in North America might be the most dramatic chapter in Sanrio’s comeback.

For years, the U.S. business was a weight around the company’s neck—losing money for six straight years through 2022. Then it flipped, becoming a true second pillar alongside Japan.

But it didn’t happen through a clever marketing campaign. It happened through uncomfortable decisions.

Sanrio restructured hard: three rounds of layoffs, the closure of its San Francisco headquarters, and a full exit from running its own direct-to-consumer retail stores in the United States. Headcount at the local subsidiary fell from about 120 people to roughly a third of that.

That pain bought Sanrio something it desperately needed: a simpler, more scalable model. Instead of tying up cash and attention in stores—inventory, leases, staffing—Sanrio America went all-in on licensing.

And it worked. With a renewed focus on placing characters like Hello Kitty with mass retailers and fashion brands, the U.S. business delivered 27.6 billion yen in sales (about $177 million), up 120%, and a record 8.9 billion yen in operating profit (about $57 million), up 213%.

What’s striking is how clearly this “new” approach was shaped by the old mistake.

In the early 2010s, Hello Kitty hit a global peak, boosted by celebrity fandom—Lady Gaga most famously—and licensing demand went into overdrive. “At the peak, the phones wouldn’t stop ringing. We couldn’t keep up with checking all the products,” recalled Keisuke Miyajima, Sanrio America’s CFO.

That kind of frenzy is seductive. It’s also how brands get diluted.

This time, Sanrio treated North America like a premium IP market: fewer partners, higher standards, and tighter control over how the characters showed up in public.

The China Opportunity

The same playbook—global ambition, local execution—showed up even more clearly in China.

In July 2022, Sanrio signed a licensing deal with Alifish, an Alibaba unit, a move that sent Sanrio’s shares surging in Tokyo. The agreement granted Alifish exclusive rights to manufacture and sell merchandise featuring 26 Sanrio characters in China under a five-year term, running from January 1, 2023 through December 31, 2027.

China was the perfect mix of massive upside and serious risk. Young consumers—especially young women—had already embraced kawaii culture. But counterfeits were rampant, and the market demanded local know-how.

Even with COVID-era disruption, momentum was clear: Sanrio’s sales in China rose 39% to 4.7 billion yen (about $34.4 million) in the fiscal year ending March 2023.

“The platform plans to develop and sell products based on all these characters while leveraging its own resources to provide consumers with high-quality IP goods,” said Wu Qian, Vice President of Alibaba Digital Media and Entertainment Group and President of Alifish.

For Tomokuni, this was the pattern: pick a world-class partner that already understands the terrain, give them enough exclusivity to commit, and keep Sanrio focused on what it does best—protecting the characters, and growing their cultural value.

VIII. The Modern Era & Future Bets (2024–Present)

Hello Kitty at 50

By 2024, Tomokuni Tsuji wasn’t just stabilizing Sanrio. He was pushing it into a new phase.

Hello Kitty turned 50, and Sanrio used the anniversary the way the best IP companies do: not as a nostalgic lap, but as a coordinated, year-long marketing engine. Collaborations, events, and limited products rolled out in waves—built to keep Kitty everywhere that mattered without sliding back into the old problem of “everywhere on everything.”

The results were hard to miss. Sanrio became a trillion-yen enterprise in 2024 and posted its strongest-ever first-half net profit, even as it continued trying to make earnings less dependent on Hello Kitty alone. Revenue climbed 43% to ¥62.8 billion, powered by licensing strength—especially in North America and China—proof that the turnaround wasn’t just domestic momentum. Sanrio was once again exporting its characters at scale.

The Film Ambition

For all of Hello Kitty’s dominance in merchandise, there’s still one glaring gap: the big screen.

Unlike Mickey Mouse, Pokémon, or Illumination’s characters, Hello Kitty has never anchored a major theatrical feature. That’s the kind of “tentpole” that doesn’t just earn at the box office—it rewires the cultural status of an IP and supercharges everything downstream, from licensing to retail to long-term relevance.

Sanrio is now taking its shot. After years of development, Warner Bros. Pictures Animation and New Line Cinema set a Hello Kitty feature film for July 21, 2028.

Leo Matsuda is directing, with Dana Fox (“Wicked”) credited with the most recent draft of the script. Beau Flynn of FlynnPictureCo. is producing, after spending nearly a decade courting Sanrio founder Shintaro Tsuji to secure the rights—reportedly the first time Sanrio granted Hello Kitty’s film rights.

The upside is obvious. Barbie didn’t just sell movie tickets; it revived an aging brand and reignited consumer demand globally. A successful Hello Kitty film could do something similar for Sanrio—turning a character long associated with products into a character that also lives in story, and opening the door to a much bigger entertainment future.

Tomokuni Tsuji, President and CEO of Sanrio Co., Ltd., put it this way: “We are extremely delighted that Hello Kitty, our global messenger of friendship, along with many other Sanrio characters, will be brought to the big screen through our creative partnership with Warner Bros. Pictures and their talented teams. This marks an exciting new chapter for Sanrio as we step into the world of Hollywood and explore new frontiers in entertainment.”

Aggretsuko: Proof of Concept

Sanrio didn’t wait for Hello Kitty to prove it could win in long-form storytelling. It already had a breakout—just with a very different character.

Aggretsuko became a Netflix original after an announcement in December 2017. The series debuted worldwide on April 20, 2018, then returned for a second season in June 2019, a third in August 2020, a fourth in December 2021, and a fifth and final season on February 16, 2023.

Critics loved it. The first season holds a 100% score on Rotten Tomatoes based on 25 reviews, and the series overall has been widely praised for pairing Sanrio’s cute exterior with a sharp, adult-targeted story.

That matters because it answers a strategic question Sanrio has grappled with for decades: can these characters be more than designs? Aggretsuko proved they can carry narrative, build fandom, and reach adults—exactly the kind of validation you want before placing a much bigger bet on Hollywood.

The Ambition Continues

Sanrio’s comeback has already blown past targets that were originally framed as a ten-year horizon—like reaching 50 billion yen in operating profit and a 1 trillion yen market capitalization. And still, at the May earnings briefing, Tsuji struck a note that’s become a theme of this era: “We are still far from where we ultimately want to be.”

The implication is clear. The turnaround was step one. Now Sanrio wants the thing that separates a great licensing company from a true modern IP powerhouse: entertainment that creates demand, not just products that capture it.

IX. Playbook: Business & Investing Lessons

The Sanrio Playbook

1. The "Blank Canvas" Character Strategy

Hello Kitty’s near-total lack of expression lets her work as an emotional blank canvas—one people can project themselves onto. That makes her unusually portable across cultures, age groups, and moods. The counterintuitive lesson for IP creators: the more you specify a character, the more you limit them. Sometimes, less story creates more commercial surface area.

2. The Licensing Discipline Paradox

Sanrio’s crisis didn’t come from a shortage of demand. It came from too much demand, handled poorly. When licensing requests flooded in, saying yes too often turned the brand from special to ubiquitous—and ubiquity is how icons become wallpaper. The turnaround required the opposite reflex: say no to most deals, and go deeper with the best partners. Volume licensing can drain brand equity; disciplined licensing can rebuild it.

3. The Nostalgia Multiplier

In the 1990s, Sanrio discovered a compounding trick: don’t “age out” your customers—let the character age with them. The kid who bought a Hello Kitty pencil case can grow up to buy a Hello Kitty handbag, then later buy Hello Kitty gifts for the next generation. When you get it right, character IP doesn’t just produce repeat purchases. It produces lifetime, even multi-generational, demand.

4. The Asset-Light Pivot

A big part of Sanrio’s recovery came from doing something painful but clarifying: shrinking direct retail and leaning into licensing. Licensing means royalty revenue with limited capital requirements—no inventory risk, fewer fixed costs, and less operational complexity. The shift helped reframe Sanrio from a merchandise-heavy operator into something closer to an IP holding company: smaller footprint, higher margins, more scalability.

5. The Multi-Character Portfolio

For years, Hello Kitty wasn’t just the flagship—she was the whole fleet. When one character represented the overwhelming majority of profits, Sanrio carried massive concentration risk. Diversifying into a broader portfolio—elevating characters like Cinnamoroll and Kuromi—created both growth options and downside protection. The lesson is to think like a portfolio manager: build multiple winners so one franchise cycle can’t sink the company.

Bull Case

Sanrio has several credible growth paths at once: continued expansion in North America and China, more digital content to build fandom, and the long-term evergreen appeal of kawaii aesthetics. The upcoming Hello Kitty theatrical film is the big swing—potentially a Barbie-like catalyst if it lands and successfully upgrades Kitty from “merch icon” to “story-driven entertainment franchise.”

The moat is the kind that’s hard to manufacture on a timeline: brand power built through decades of emotional connection. In Hamilton Helmer terms, it looks like Brand Power, reinforced by the way the business is structured around owning and licensing a deep character roster—a model that’s difficult to copy without decades of accumulated IP.

Bear Case

Character IP is cyclical by nature, and Hello Kitty has already had multiple peaks and valleys. The current valuation assumes continued momentum; if growth slows, the multiple compresses. A theatrical film that disappoints, fading traction in China, or another round of overexposure could weaken the brand.

Even structurally, the forces are real: substitutes are everywhere (other kawaii IP, games, streaming, short-form video), large retailers and major partners have negotiating leverage, and new character companies can break out quickly online. Sanrio’s moat is meaningful, but it isn’t unbreakable.

There’s also governance risk. Sanrio remains family-controlled, with the Tsuji family retaining significant influence. Tomokuni has delivered, but succession and decision-making in family-led public companies always come with edge-case risks the market can’t fully price.

Key KPIs to Monitor

-

Licensing Revenue as Percentage of Total Revenue: This captures the shift from capital-intensive merchandise to asset-light IP monetization. Higher generally means better scalability and margin structure.

-

Character Concentration (Hello Kitty % of Profits): Watch whether diversification continues—or whether the business drifts back toward over-dependence on Kitty.

-

North America and China Revenue Growth: These are the biggest international engines. Sustained strong growth suggests the new playbook is working; deceleration can signal saturation, execution issues, or rising competition.

Final Thoughts

Shintaro Tsuji understood something profound when he left Hello Kitty without a mouth: the strongest emotional connections aren’t created by telling people what to feel. They’re created by giving people room to feel.

A mouthless cat—born inside a company founded by a man shaped by isolation and loss—went on to generate more revenue than Harry Potter, more than Star Wars, more than any franchise except Pokémon. She’s shown up everywhere from UNICEF campaigns to high-fashion collaborations, speaking every language by speaking none.

Now, half a century after her creation, Hello Kitty is heading for her biggest test yet: Hollywood. If the 2028 film works, it won’t just be a new revenue line. It will be a proof point that Sanrio can build modern, story-driven fandom at global scale.

And if that happens, the comeback we’ve been watching may turn out to have been only the opening act.

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music