Unicharm Corporation: The Story of Japan's Quiet Hygiene Empire

I. Introduction & Episode Roadmap

Picture a factory floor in a small city on Shikoku—Japan’s smallest main island—in the early 1960s. The air is gritty with cement dust. Workers are turning out wood wool cement board, the kind of unglamorous construction material a country needs when it’s rebuilding fast after World War II.

Running the operation is Keiichiro Takahara. He’s just walked away from his father’s paper manufacturing business to start his own company. Japan is in a building boom, Takahara understands materials, and the plan is straightforward: make a living supplying the nation’s growth.

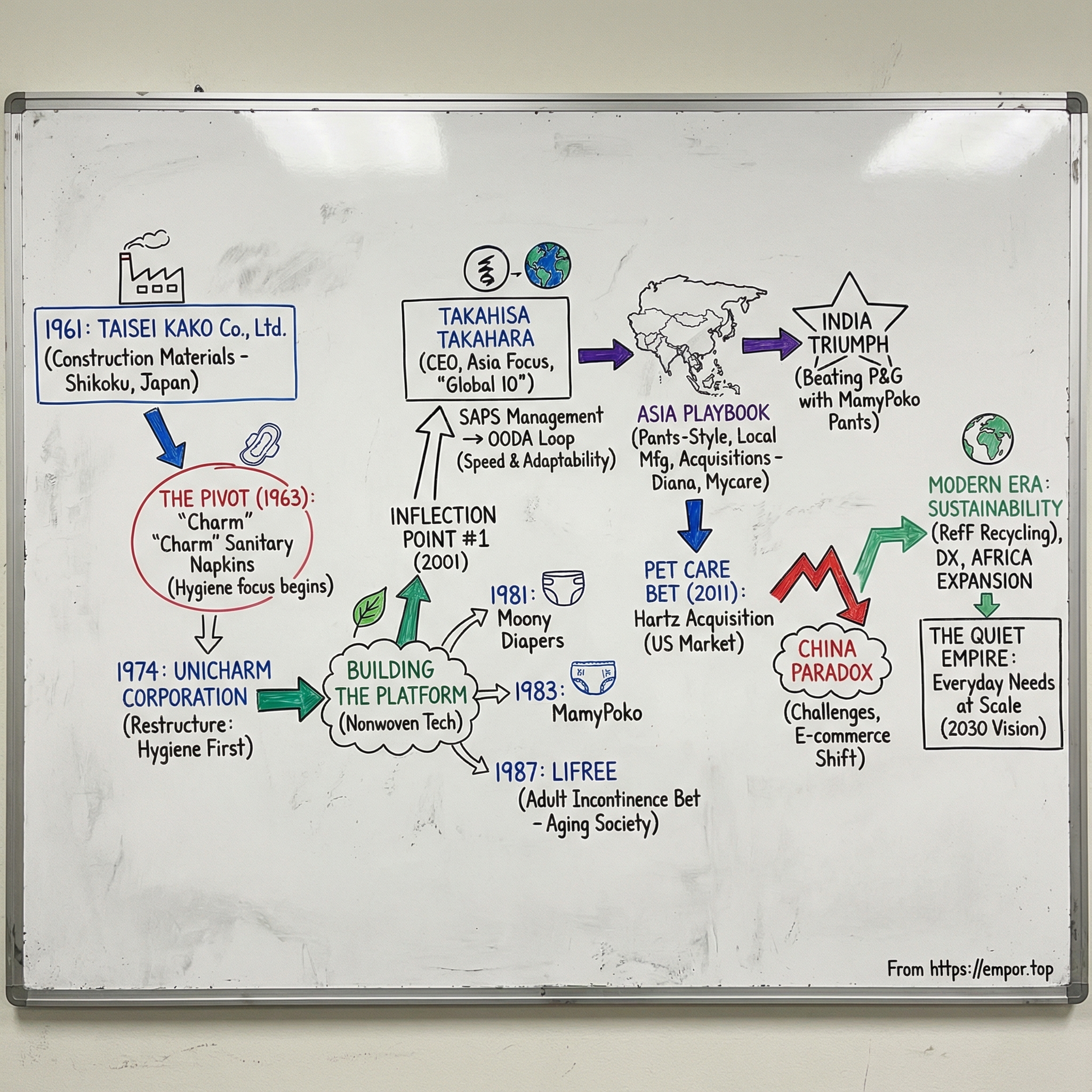

What he can’t see yet is that a pivot most people would dismiss as mundane—away from cement boards and into sanitary napkins—will become the defining move. Taisei Kako Co., Ltd., founded on February 10, 1961, starts in building materials. Then, in 1963, it moves into feminine hygiene products. That decision doesn’t just add a new product line. It quietly locks the company onto a path that, over decades, will turn it into a hygiene giant.

Today, Unicharm is one of the more surprising success stories in global consumer products: a company that went from obscure regional supplier to multinational force, competing head-to-head with—and in many Asian markets beating—household names like Procter & Gamble and Kimberly-Clark. Unicharm makes disposable hygiene products across life stages: baby diapers, adult incontinence products, feminine care, household items, and pet care. It operates in around 80 countries and leads Asia in baby and feminine care. In diapers, it holds the top share in major markets including China, India, Indonesia, Vietnam, and Thailand.

The scale is bigger than most people realize. As of 2024, personal care accounts for about 80% of sales, with most of the rest coming from pet care. Roughly two-thirds of revenue comes from outside Japan, and the majority of that overseas business is in Asia—especially markets like China, Indonesia, and Thailand. Across its footprint, Unicharm employs about 16,500 people.

That brings us to the question at the heart of this story: how did a construction materials company from rural Japan become the hygiene king of Asia—and dethrone giants like P&G in multiple markets?

The answer isn’t a single breakthrough. It’s a playbook: an ability to read demographic change early, a culture of product innovation in absorbent materials, disciplined market-by-market expansion, and—crucially—a family leadership transition that turned a strong Japanese company into an international one.

Along the way, a few themes keep showing up: family dynasty and generational handoff; category creation versus category domination; the craft of building excellence in “unsexy” businesses; and the discipline to ride demographic tailwinds while surviving demographic headwinds. This is the story of an empire built on everyday needs—diapers, sanitary products, incontinence care—and the quiet power of getting the fundamentals right.

II. Origins: From Paper Mills to Pivot (1961–1974)

Keiichiro Takahara was born in 1931 in Kawanoe City, Ehime Prefecture—today part of Shikokuchuo City—and he grew up in a place where paper wasn’t just a product. It was an identity. Shikoku had long been one of Japan’s paper manufacturing centers, and Takahara’s family ran a paper business there. That matters, because Unicharm’s story isn’t really a story about diapers or sanitary napkins at first. It’s a story about materials—fibers, absorbency, and manufacturing know-how—waiting for the right market to meet it.

In 1961, Takahara made the first big move of his career: he resigned from his father’s company and founded his own, Taisei Kako Co., Ltd. On paper, it looked like a straightforward entrepreneurial spin-out in a country booming with post-war reconstruction. Japan was industrializing at a blistering pace, and a young founder with materials experience could do very well simply by feeding the building frenzy.

So that’s what Taisei Kako did. Takahara turned the company toward the manufacture and sale of wood wool cement board—construction panels used for insulation and building. For a couple of years, the business was exactly what it appeared to be: an industrial materials company serving a rebuilding nation.

Then came the pivot that would define everything.

Takahara had something most construction-material founders didn’t: a paper manufacturing background that made him fluent in fibers and absorbent materials. And once you see hygiene products through that lens, they stop looking like “consumer goods” and start looking like a materials problem you can solve better than anyone else.

In 1963, Taisei Kako entered feminine hygiene by launching its first sanitary napkins under the “Charm” brand. It was a decisive shift—one that leveraged emerging nonwoven fabric technologies and met a need that was growing rapidly as Japan’s living standards rose. Convenience, reliability, and dignity weren’t “nice-to-haves” anymore. They were becoming expectations.

The company didn’t dabble. It built. In 1965, it established a sales subsidiary, Charm Corporation. In 1968, it expanded the brand with the launch of the panty liner Charm Nap Sawayaka. Step by step, Takahara was turning a materials shop into a consumer products machine—one focused on repeat purchases, distribution, and trust.

By the early 1970s, the contrast was hard to ignore. Construction materials were becoming a commodity business. Feminine care, on the other hand, had room to grow—and the right kind of growth: brand-driven, technology-enabled, and sticky.

In 1974, Takahara made the choice official. He restructured the company so the construction materials operation became a subsidiary of the sanitary care business, and the core company took a new name: Unicharm Corporation. The renaming wasn’t just cosmetic. “Uni” signaled a universal reach, and “Charm” tied back to the company’s first major hygiene brand—and to an ambition centered on women’s confidence and everyday wellbeing.

That restructuring was the point of no return. Unicharm would be a hygiene company first, with its original construction roots pushed to the side. The full transformation would take years to play out, but the direction was locked in. And the pattern that would define Unicharm for decades was already visible: when Takahara saw a better opportunity, he was willing to walk away from the business he started—and bet the company on the unglamorous category that was quietly becoming essential.

III. Building the Platform: The Technology Foundation (1976–1987)

After the 1974 restructure, Unicharm did what great consumer companies do in their “awkward teenage years”: it built the platform. Not with flashy acquisitions or marketing stunts, but by turning a single strong product category into a repeatable system—new brands, new use cases, same underlying materials advantage.

In 1976, that system got fuel. After launching a new-generation panty liner, Charm Nap Mini, Unicharm listed on the Tokyo Stock Exchange’s secondary market. Going public wasn’t just a milestone. It was a funding mechanism for what came next: widening the product portfolio without losing the thread of what the company was actually good at.

That thread was simple and powerful: nonwoven fabrics and absorbent materials. If you can design, process, and manufacture absorbency better than anyone else, you don’t just make better sanitary napkins. You can move that capability sideways into any “clean, dry, comfortable” problem people will pay to solve.

Unicharm’s first big sideways move was into baby care. In 1981, it launched disposable diapers under the Moony Man label. The following year, it strengthened its home base by introducing Sofy, a new line of sanitary napkins. Then in 1983, it added another diaper brand: Mamy Poko, positioned as a premium-quality disposable diaper.

What emerged was a portfolio that could cover the market, not just a product that could win it. With Moony at the higher end and MamyPoko reaching a broader set of households, Unicharm could grow with consumers as their needs and budgets changed—and defend itself from competitors trying to undercut it from below or outspend it from above.

But the company’s reputation wasn’t built on segmentation alone. It was built on invention.

In 1992, Unicharm introduced the world’s first pants-style disposable diaper, MOONYMAN. It sounds like a small design tweak until you remember what diaper changing looked like with tape-style products: lay the baby down, line everything up, stick the tabs, hope they don’t tear loose. That’s manageable with a newborn. It gets a lot harder once the baby becomes a wriggling, crawling, standing, sprinting little human.

Pants-style diapers flipped the experience. You could pull them on like underwear. Convenience went up, frustration went down, and suddenly Unicharm wasn’t just competing in the diaper category—it was reshaping it.

The company didn’t stop at one hit. It followed with new sub-categories: Oyasumiman sleeping underwear, Trepanman toilet training pants, and Moonyman Mizu-Asobi Pants for water play and swimming. These weren’t incremental variations. They were Unicharm’s pattern in action: find an unmet need, use absorbency and nonwoven know-how to solve it, and in the process expand the market rather than simply fight for share inside it.

Underneath all of this was a clear thesis that would become the company’s identity: the nonwoven fabric and absorbent material processing and molding technologies cultivated in feminine care could be leveraged outward—into baby care, then health care, then household needs—so Unicharm could support daily life across child-rearing, nursing care, and housework.

And by the mid-1980s, Unicharm was already testing just how far that logic could stretch. In 1986, it established Unicharm Pet Care and launched the Fresky Aiken Genki dog food line. On the surface, pet care looked like a side quest. In reality, it was another proof point: if you understand hygiene, comfort, and routine replenishment, you can build businesses around more than just humans.

By the end of this era, Unicharm had something far more valuable than a handful of successful products. It had a compounding engine—materials expertise, manufacturing capability, and a habit of turning that advantage into new categories. And that engine was about to meet one of the most powerful forces in modern Japan: the rapid aging of its population.

IV. The Lifree Bet: Anticipating Japan's Aging (1987–1990s)

In 1987, while most competitors were fixated on the obvious prize—the booming baby diaper market—Unicharm took a quieter, stranger bet. It entered a category most companies didn’t want to touch, let alone advertise: adult incontinence. The brand name was Lifree, and the move would end up being one of the most important in Unicharm’s history.

The timing wasn’t accidental. Adult incontinence in Japan was becoming more common for multiple reasons. Women were increasingly giving birth at older ages, which could lead to incontinence complications. And, more broadly, Japan’s population was beginning a rapid shift toward old age as the proportion of senior citizens climbed toward the end of the century. Unicharm saw the demographic wave forming and chose to build for it early.

That early entry mattered. It gave Unicharm a head start in a market that barely existed in modern retail terms—and it let the company shape what the category would even mean. But the risk wasn’t just financial. Incontinence was deeply stigmatized. In socially conservative Japan, it was the kind of problem families dealt with quietly, if at all. Getting retailers to stock adult diapers and getting consumers to buy them required something Unicharm had rarely needed at this scale: sustained, patient education.

So Unicharm didn’t market Lifree as a symbol of decline. It marketed it as a tool for living. The message was about independence, dignity, and staying active—language that made the product easier to accept, and easier to talk about.

That philosophy showed up clearly in 1995 with the launch of Lifree Rehabilitation Pants. Alongside the product, Unicharm proposed the concept of “Aiming for zero bedridden,” framing adult incontinence care not as surrender, but as support—reducing the physical, economic, and emotional burdens on both care receivers and caregivers.

And then Unicharm did what it does best: it expanded the market by subdividing it. In light incontinence and urinary incontinence care, it helped grow Japan’s market with two complementary approaches—liner-type products in the Charm Nap range and napkin-type products under Lifree. As more seniors remained active and continued leisure activities, demand increased not just for heavy-duty solutions, but for discreet, everyday products that let people keep their routines without anxiety.

Over time, the company widened the addressable audience further. Light incontinence products had long been marketed mostly to women, but many men experienced the same issue—often with even more reluctance to acknowledge it. In 2014, Unicharm launched Lifree Comfortable Thin Pads for Men, designed to be discreet and prevent staining, aimed at men who avoided going out due to concerns about light incontinence.

By building products for both moderate and light needs—and by pushing acceptance through marketing that de-stigmatized the issue—Unicharm didn’t just participate in the category. It defined it. The result was a dominant position in Japan’s retail adult incontinence market, with a share of more than 50%.

This is what Lifree really represents in the Unicharm playbook: using core absorbent-material technology from one category to create another, then riding a demographic shift with a product portfolio and a narrative that makes the new category socially usable. It turned what could have been a looming headwind—fewer babies—into a durable tailwind: a growing population of seniors who needed exactly what Unicharm knew how to make.

V. INFLECTION POINT #1: The 2001 Leadership Transition & Asia Bet

By 2001, Unicharm had built something rare: a real innovation engine in absorbent materials, a portfolio that spanned life stages, and a dominant position in Japan’s most “everyday” categories. But it also faced a problem that no amount of product excellence could wish away.

Japan was shrinking.

That year marked the most consequential inflection point in Unicharm’s history, because it marked a handoff—and a change in ambition. Takahisa Takahara, born on July 12, 1961, became CEO. He was the founder’s son, which made this a family succession. But it wasn’t a ceremonial passing of the torch. It was the beginning of Unicharm’s transformation from a great Japanese hygiene company into an Asian, and then global, one.

The symbolism in the timing is hard to miss: Takahisa was born just months after his father founded Taisei Kako. In a very real sense, he grew up alongside the business. And unlike heirs who arrive at the top by shortcut, his resume inside Unicharm reads like deliberate apprenticeship. In the late 1990s he moved through procurement and international operations, then into leadership of the feminine hygiene business, and then into management strategy. By the time he took the top job, he knew how the company worked—how it sourced, how it sold, how it built products, and where the bottlenecks would be if Unicharm ever tried to scale beyond Japan.

He took over at 40, and the context made the mandate obvious. Lifree had positioned Unicharm brilliantly for an aging society, but the broader arithmetic was still brutal. Fewer babies meant fewer baby diapers. Fewer young women meant a smaller core market for feminine care. Even if Unicharm won every battle at home, the war was demographic.

Takahisa’s answer was to move the battlefield.

His strategy was to turn Unicharm from a Japan-first company with overseas outposts into a business built for the fastest-growing consumer markets in the world—especially Asia. The company had already begun laying the groundwork, but under Takahisa the pace and intent sharpened. In 2001, Unicharm established its first manufacturing subsidiary in mainland China. In 2002, it added a sales and marketing subsidiary for China and entered the Philippines with a dedicated subsidiary there as well. The message inside the company was clear: Japan would remain important, but the future would be made abroad.

To give that push a name and a target, Takahisa introduced what became known as “Global 10”: become Asia’s number one company in nonwoven fabric and absorbent materials, capture a 10% share of the global market, and earn a place among the industry’s top three players worldwide. It was an audacious statement for a company that, not long before, had been a regional manufacturer of construction panels. But it was also tightly aligned with Unicharm’s real advantage: it didn’t need to invent a new capability to go global. It needed to export the one it already had.

Of course, ambition is cheap. Execution is not. Scaling across languages, retail systems, and cultures requires a different operating rhythm than winning in one home market. So in 2003, Takahisa introduced a management model that would become central to how Unicharm ran: SAPS—Schedule, Action, Performance, Schedule.

The idea was simple, and intentionally repetitive. Make the plan. Execute it. Measure what happened and what needs fixing. Then roll that learning directly into the next plan. Done weekly. Over and over. In practice, SAPS embedded a PDCA-style cycle into the organization’s muscle memory, creating a cadence of accountability and continuous improvement that mattered enormously once Unicharm was managing multiple countries at once.

This is the leadership transition’s real legacy: under Takahisa, Unicharm became an overseas-driven company. More than half of its revenue would eventually come from outside Japan, largely from other Asian markets—a reversal that would have been almost unthinkable when the business was still called Taisei Kako. Takahisa himself would later appear on the 2022 Forbes Billionaires List, with an estimated wealth of $6.4 billion, ranked 398th.

And as Unicharm expanded, it kept refining a framework for where to play and when. The company observed a tight link between a country’s per capita GDP and how quickly consumers adopt products like feminine care items and disposable baby diapers. Their research suggested adoption accelerates once per capita GDP crosses about $3,000. Later, as income rises further, those categories mature—and growth shifts toward products like adult incontinence care and pet care.

That insight became a playbook: treat each country as being in a particular stage—early, growth, uptake, or mature—and match products, pricing, and distribution to that stage. The goal wasn’t just to enter markets. It was to expand usage, build habit, and time category creation so Unicharm could grow with the country as it developed.

This is what made 2001 different from every prior chapter in the company’s story. Keiichiro Takahara built the materials and product foundation. Takahisa took that foundation and aimed it outward—pairing long-term demographic thinking with a machine for repeatable execution. The quiet hygiene empire was about to leave Japan, and it had a system for doing it.

VI. INFLECTION POINT #2: The Southeast Asia Playbook (2005–2015)

From 2005 to 2015, Unicharm stopped looking like a Japanese company that happened to sell abroad and started operating like something else entirely: Asia’s hygiene specialist, built for the region’s growth and tuned to its realities. In the process, it refined a playbook that would later travel—almost intact—to India and beyond.

The core insight was deceptively simple. Unicharm didn’t just ask, “Is this market big?” It asked, “Is this market about to change?” As incomes rose, there was a predictable moment when disposable hygiene products stopped being a luxury and started becoming a habit. Unicharm tried to enter right before that moment—then ride the steepest part of the adoption curve.

And it did something that surprised a lot of Western competitors: it led with pants-style diapers.

In many mature markets, pants were treated as a premium add-on to tape-style diapers. Unicharm flipped the framing in Southeast Asia. It brought pants diapers into less developed markets and made an affordable version available, positioning pants not as a niche upgrade, but as the default. The result wasn’t just share gains—it was a shift in what consumers expected a diaper to be.

Indonesia became the clearest example of how well this approach could work. Unicharm built local scale and then kept pushing its reach outward, even adding a third plant—this one in Surabaya, East Java—to better serve the country’s outlying eastern islands. The first two sites had been in Jakarta; Surabaya was about coverage and logistics, not prestige.

By then, Uni-Charm Indonesia was the top player across its core categories. MamyPoko led baby diapers, Charm led feminine care, and Lifree built a meaningful position in adult care. Reported market shares were striking: 65.6% in baby diapers, 40.1% in sanitary napkins, and 33% in adult diapers. Indonesian sales totaled Rp 6.5 trillion (US$543.02 million) last year, and by March they accounted for 10% of Unicharm’s global sales—its largest share in Southeast Asia. Japan and China remained major revenue drivers, contributing 43% and 15% respectively.

That kind of dominance doesn’t happen by accident. Unicharm paired products that fit local needs with relentless distribution execution—and then reinforced both with local manufacturing, so it could price competitively and stay close to the market.

Unicharm also used acquisitions as accelerants, especially when they could buy local leadership rather than build it from scratch. In August 2013, it acquired Myanmar Care Products (Mycare), gaining a foothold in Myanmar’s fast-growing market. Mycare, founded in 1995, made Eva—number one in the country’s feminine hygiene napkin market—and MyBaby diapers, the second-largest diaper brand after Unicharm’s MamyPoko. Unicharm described the logic plainly: new markets were being created, and it wanted to secure overwhelming share faster by expanding product availability and sharing manufacturing technology and marketing know-how.

In Vietnam, the pattern repeated with the acquisition of Diana. Unicharm combined Diana’s local market understanding and operating experience with Unicharm’s product development capabilities. The theme across these deals stayed consistent: find local winners, take control, plug in Unicharm’s technology and operating cadence, and keep the local knowledge that actually made the business work.

Even as it expanded across emerging Asia, Unicharm didn’t neglect its home base. In July 2006, it bought Shiseido’s sanitary goods operations. The deal boosted Unicharm’s domestic share by 5%, a reminder that the company wasn’t choosing between Japan and overseas—it was trying to maximize both.

And it didn’t limit its ambitions to Asia. In 2005, Unicharm acquired 51% of Gulf Hygienic Industries, giving it a meaningful position in the Middle East—another region that would become a contributor to growth over time.

By 2014, Asian sales hit a record high, representing about 42.8% of Unicharm’s total sales. Within that mix, Indonesian sales comprised 10%, Thailand 5%, Vietnam 3% and Taiwan 3%, while China represented 15%.

By the mid-2010s, Asia wasn’t a growth option on the side—it was the center of gravity. And Unicharm had proven a repeatable formula: enter as the income curve bends upward, lead with pants-style innovation at accessible prices, build manufacturing capacity close to demand, use acquisitions to buy local advantage, and run the whole machine with discipline. The next test would be the biggest one yet: India.

VII. INFLECTION POINT #3: The Hartz Acquisition & Pet Care Bet (2011)

By the time Unicharm had proven its Southeast Asia playbook, it was also nurturing a second growth engine—one that, at first glance, looked like a detour from diapers and feminine care: pet care.

The rationale was surprisingly similar to the one that powered Lifree. Japan was aging and urbanizing, and household structures were changing. As birthrates fell and more people chose pets instead of children, spending on pet products rose. For Unicharm, that wasn’t a trend to observe from afar; it was another “daily life” category where comfort, cleanliness, and habit mattered—and where its absorbent-material expertise could travel well.

In fact, Unicharm wasn’t new to this. It entered pet care back in 1986 and grew into the number-one manufacturer in Japan’s pet-care market through differentiated products and strong marketing. Its biggest advantage showed up in a very Unicharm way: pet toilet products like toilet sheets, where nonwoven fabric and absorbency technology made the difference. It became an overwhelming leader in that niche, turning a materials edge into a category stronghold.

The next step was obvious: take the domestic win overseas. And in 2011, Unicharm made its biggest acquisition ever—a majority stake in The Hartz Mountain Corporation.

On December 30, 2011, Sumitomo Corporation, Sumitomo Corporation of America, and Unicharm closed a joint venture deal that gave Unicharm a significant stake in Hartz, a wholly owned subsidiary of Sumitomo Corporation. Announcing the deal, Mr. Koichi Isohata of Sumitomo framed the logic clearly: “This new strategic partnership brings together the brand power, deep category expertise and existing market share of Hartz with Unicharm's proprietary technology and high-performing innovation. The alliance is intended to grow the Hartz business, maximizing the potential of the U.S. Pet Care market and ideally build the business globally.”

The U.S. was the prize. It is the largest pet care market in the world, representing roughly $30 billion of worldwide sales. And Hartz gave Unicharm something it couldn’t realistically build from scratch: instant access.

Hartz’s own story is classic American immigrant entrepreneurship. It began in 1926, when a 26-year-old Max Stern left Germany for New York, arriving with almost no money and not a word of English. He started by selling singing canaries—one early customer was the John Wanamaker Department Store at Astor Place in Manhattan—then opened his business nearby at 36 Cooper Square. Over time, that scrappy beginning became a major pet-supplies platform.

By the time Unicharm arrived, Hartz owned leading brands across major categories—flea and tick products, treats, training pads, and dog toys—and, crucially, it had distribution reach into about 110,000 U.S. stores.

This is why the deal mattered. Unicharm brought world-class absorbent technology and leadership in pet toiletry products. Hartz brought a household-name brand in the U.S., relationships with major retailers, and a deep read on American pet owner behavior. Together, Unicharm and Sumitomo aimed to grow pet care in the U.S. by pairing Hartz’s brand power with pet toiletry products built on Unicharm’s absorbent-material technology—technology that already had a strong reputation with Japanese consumers.

The macro tailwind here was what the industry calls “pet humanization”: owners increasingly treating pets like family members and paying more for food, health, and hygiene. That aligned neatly with Unicharm’s preferred way to compete—on product performance and quality, not on being the cheapest option.

The results reinforced the bet. In FY2022, pet care sales were 125.3 billion yen (119.9% compared to FY2021), and core operating profit was 18.4 billion yen (125.5%). Unicharm also pointed to another tailwind: pet ownership rose as COVID-19 increased the time people spent at home, in Japan and abroad.

And Unicharm hasn’t treated pet care as “just the U.S.” In China, the number of dogs and cats is about seven times Japan’s, and the pet care market, including pet food, is the second largest in the world after North America. In 2022, through a capital and business alliance with JIA PETS, Unicharm set out to expand its involvement in China by combining its product development and production capabilities with local momentum.

Over time, pet care has become more than a side business—it’s a meaningful diversification lever. Unicharm reported that pet care grew, with North American pet care posting strong results (sales +14.6%, income +25.3%), driven by value shifting and successful new product launches, while absorbing inventory build-up related to tariff preparations.

Zooming out, the Hartz acquisition shows three things about how Unicharm thinks. First, a core technology advantage—absorbency and nonwoven materials—can be redeployed in adjacent markets that don’t look obvious at first. Second, the right acquisition can buy geography and channels that would otherwise take decades to earn. And third, category choice matters: pet care, with premiumization and “pet as family” tailwinds, fits Unicharm’s strengths—and gives the company another durable engine alongside human hygiene.

VIII. INFLECTION POINT #4: The India Triumph Over P&G (2008–2023)

If Southeast Asia proved Unicharm’s playbook could travel, India was the hardest possible exam. Unicharm entered the country in 2008. By 2022, it had taken the number-one spot in baby diapers, overtaking Procter & Gamble’s Pampers. The engine of that upset was classic Unicharm: lead with pants-style diapers, keep them premium in performance, and then do the hard work of convincing first-time users that disposables weren’t just convenient—they were better for everyday health and comfort.

The prize was enormous. India’s population is around 1.2 billion, and Unicharm noted that the number of infants is roughly 23 times Japan’s level. “In the future, we think India has the potential to become an even larger market than China,” the company wrote.

But in 2008, “potential” didn’t look like a business yet. Disposable diaper penetration was below 2%. Most babies wore cloth. Pampers dominated the small modern trade footprint, Huggies was present, and Unicharm was the late entrant—going up against global incumbents with deep pockets and well-trained playbooks of their own.

So Unicharm changed the rules of the game.

Instead of fighting head-to-head in tape-style diapers through organized retail, it pushed the product format it already believed in: pants. In many markets, pants were treated as a premium option. Unicharm brought pants to a less developed market and made an affordable version available—an approach that surprised Western competitors, especially once it started working.

The inflection came in 2010, when MamyPoko launched disposable pants in India in a big way. The first offerings were priced relatively lower than tape-style diapers. That was disruptive, because pants were generally positioned as the upgrade. Unicharm flipped that expectation and made pants the on-ramp.

It wasn’t just pricing for the sake of pricing. It was a reading of behavior. For parents trying disposable diapers for the first time, ease of use mattered intensely. Pants were simpler than tapes—fewer steps, fewer chances to get it wrong, and far easier with a squirming baby. By making the easier product accessible, Unicharm captured the segment that was growing fastest while competitors stayed anchored to their tape-first portfolios.

Then came the compounding: years of steady execution. Nearly a decade ago, Unicharm’s diaper business in India was roughly half the size of P&G’s, but it has since grown over 35% annually.

By FY23, that momentum showed up clearly in the numbers. Unicharm became India’s biggest diaper company by sales after revenues expanded 28% during FY23. Revenues of Unicharm’s Indian unit rose to Rs 3,612 crore in FY23, with diapers accounting for 84%, or Rs 3,022 crore. P&G’s diaper business reported Rs 2,422 crore.

In FY23, MamyPoko overtook Pampers as India’s top-selling diaper brand—powered by distribution expansion, consumer trust, and the strategy that made pants-style diapers the default choice for a growing set of households.

Distribution was the force multiplier. According to a company spokesman, Unicharm expanded its reach to about two million outlets. That kind of coverage doesn’t happen through branding alone; it takes years of building sales execution, logistics, and retailer relationships—and it’s especially decisive when growth moves beyond big cities into smaller towns and rural markets.

Unicharm credited its results to a mix of design innovation and reach. It was the first to launch underwear-shaped diapers in the country, and it continued pushing new product features—such as sheets enriched with coconut extracts designed to be more skin-friendly. “MamyPoko pants' effort to meet consumer needs in terms of absorption and skin friendly products, along with increased distribution penetration each year at urban, metro towns and rural, has helped the company to grow in the last few years,” said Vijay Chaudhary, managing director of Unicharm India.

And Unicharm kept investing to stay ahead. It rebuilt and expanded local manufacturing capacity, including completing its Ahmedabad Plant in Gujarat after a 2020 fire. The plant was set to be operational from February 2025, becoming the third production site in India—intended to stabilize supply and support products tailored to local needs.

However you slice it, India was one of Unicharm’s most meaningful competitive wins. Beating P&G—an incumbent with bigger global resources and decades of emerging-market experience—took a differentiated strategy, disciplined execution, and patience measured in years, not quarters. And the payoff is bigger than a trophy. It validated Unicharm’s emerging-market formula in one of the toughest arenas on earth, and positioned the company to keep growing as incomes rise and disposable diaper adoption continues to spread.

IX. The China Paradox: Lessons in Humility (2012–2020)

For all the momentum Unicharm built in Southeast Asia and India, China delivered something every great operator eventually runs into: a market that refuses to follow the script. It was the world’s biggest diaper opportunity, and for a while it looked like Unicharm would win there too. Instead, China became the company’s most important lesson in humility.

In 2012, Unicharm held an 11% share of China’s diaper market. By 2019, that had fallen to 7%. Early on, Japan-produced diapers were in high demand, prized for quality and comfort. But Chinese manufacturers didn’t stay behind for long. They improved rapidly—raising absorbency and overall performance—until the gap that had made Japanese imports special started to close.

The strategic pain showed up in the financials. In 2019, Unicharm booked an asset impairment loss of 11.9 billion yen on its factory in China, after weak sales of its midpriced MamyPoko diapers left it unable to recover its investments. When a market turns against you, it’s one thing to lose share. It’s another thing to realize you built capacity for demand that never arrives.

So what went wrong?

First, the competition curve in China was simply steeper. In other emerging markets, Unicharm could often count on a longer window where local players lagged on technology and manufacturing. In China, that window closed quickly as domestic brands invested heavily and caught up.

Second, China’s channel dynamics were fundamentally different. In diapers, 60% to 70% of sales were happening online. That’s not a small shift—it changes the whole game. E-commerce rewards different skills than traditional retail: digital discovery, platform promotion, rapid iteration, and a different kind of brand trust. Japanese diaper makers, Unicharm included, lagged in adapting to that reality.

Third, the company’s positioning didn’t land cleanly in the middle. Premium quality appealed to some consumers, but the mass market was brutally price-competitive. And Unicharm’s midpriced offerings struggled to find their footing between those poles.

Over time, the conclusion became unavoidable: China wasn’t going to be the same kind of compounding growth engine that Indonesia or India had become. Unicharm began shifting its emerging-market strategy by moving production capacity away from China and toward India and Africa, where it expected steadier growth in domestic consumption. “We want to capture [at least] one-third of market share in emerging countries as soon as possible,” CEO Takahisa Takahara said at a press conference, as he laid out plans to promote diapers across Africa, India, and South America. Nikkei Asia reported that Unicharm planned to deploy much of a 50 billion yen investment budget to ramp up baby diaper production capacity in India and Africa.

That pivot was an admission of something many companies resist saying out loud: not every market is worth fighting for at any cost, especially when the conditions that made you successful elsewhere don’t hold.

And China kept throwing punches. More recently, Unicharm cited significant challenges across Asia, with sharp declines in sales and profitability, driven primarily by operations in China, Indonesia, and Thailand—pressured by intense local competition and reputational damage. In China, rumors about feminine care products, amplified through national media, hit sales and margins hard.

Still, this is where Unicharm’s adaptability shows up again. In China and Southeast Asia, it leaned into rollouts of products tailored to local needs and strengthened promotions in fast-growing e-commerce channels—moves that helped drive a steadier improvement in performance.

China, then, is the counterweight to the Unicharm legend. It’s the reminder that winning in one set of emerging markets doesn’t automatically translate to the biggest one. Competitors get better. Channels change. Consumers behave differently. And sometimes the most strategic move isn’t doubling down—it’s redeploying resources to the next wave of opportunity.

X. Modern Era: Sustainability, DX, and Africa (2015–Present)

In the last decade, Unicharm’s story has shifted from pure geographic expansion to something more complicated—and, in many ways, more consequential. The company has had to confront the environmental reality of disposable products, modernize how it runs in a fast-changing world, and look for the next wave of growth in places where the category is still being created. That means sustainability, digital transformation, and a new frontier: Africa.

First, Unicharm simplified what it was. From the 2000s onward, it restructured its portfolio and sold off multiple businesses, including the founding building materials segment. The company that began in construction materials deliberately narrowed its focus to what had become its real strength: hygiene and pet care, built on absorbent-material technology.

That focus set the stage for one of Unicharm’s most ambitious modern initiatives: recycling.

In 2015, Unicharm launched a cross-divisional project called Recycle for the Future—RefF for short (pronounced “riifu,” and symbolized by a leaf). The goal was not incremental waste reduction. It was to commercialize horizontal recycling: turning used disposable diapers back into raw materials that could be used to make new ones. Unicharm set up a test facility at the nearby Soo Recycle Center to work on real-world implementation. In 2018, the town of Osaki in Kagoshima also began participating. And in 2022, Unicharm successfully commercialized disposable adult diapers made with recycled pulp, supplying them to hospitals and nursing care facilities in Kyushu.

The RefF Project became the world’s first horizontal recycling initiative for used disposable diapers into new ones. And the process is as industrial as it sounds: used diapers are finely ground, washed, and then separated into their component materials—pulp and superabsorbent polymers. Because those materials are still unpleasant and contaminated at that stage, Unicharm treats the pulp with ozone to sterilize it, while the superabsorbent polymer receives an acid treatment that restores its absorbing capability. After that, both inputs are clean and safe enough to reuse in new products.

For a company built on disposables, this is a direct answer to the most fundamental critique of the business model. Unicharm has said it plans to establish recycling plants in 10 municipalities by 2030—and, eventually, to expand the model globally.

At the same time, the company has been modernizing how it operates. The SAPS model—Schedule, Action, Performance, Schedule—helped power Unicharm’s rapid expansion in the 1990s and 2000s, particularly across emerging Asian markets. But it also had a weakness: it was too anchored to the original plan. When conditions changed, sticking to the schedule could get in the way of getting the outcome right.

So in 2019, Unicharm shifted from SAPS to the OODA Loop methodology: Observe, Orient, Decide, Act. The intent was speed and adaptability—seeing what’s happening in the market, interpreting it correctly, making the call, and moving. In a more volatile environment, this kind of responsiveness becomes more valuable than rigid planning cycles.

In 2020, Unicharm added a broader framing for where it wanted to go: Kyo-sei Life Vision 2030. It’s a comprehensive ESG vision intended to integrate environmental and social priorities into the business. Among its targets is a goal of using 100% renewable electricity by 2030.

And then there’s the next growth map.

Looking ahead, Unicharm has been treating Africa as the next major frontier—much like Southeast Asia was in the 2000s. In Kenya, Unicharm announced it would begin production and sales of sanitary napkins from January 2025 through a partnership with Toyota Tsusho and its group company CFAO Kenya Limited. The stated aim is twofold: contribute to women’s social advancement and address social issues by expanding access to sanitary products in markets where usage is not yet widespread. The partnership combines Unicharm’s nonwoven and absorbent processing technologies with Toyota Tsusho’s local network and operating experience. The backdrop is a market still early in the adoption curve—Unicharm noted that the penetration rate of sanitary napkins in Kenya is around 30%.

If that goes well, Unicharm has said it will consider expanding into Nigeria and South Africa. Today, it already manufactures these products in Africa at a site in Egypt, and plans to supply new markets from there.

The Africa strategy is familiar: enter early, build local production, work with strong local partners, and tailor products to local needs and price points. Low penetration isn’t a drawback in this framework—it’s the point. It’s where category creation is still possible.

Meanwhile, Unicharm has continued to localize elsewhere too. In the Middle East, products containing olive oil designed to reflect local lifestyles kept gaining popularity. Profitability improved steadily in North America and Brazil. And looking into fiscal 2025 and beyond, Unicharm has positioned Africa and countries including India and its neighbors as key regions for personal care, where it expects market expansion driven by population growth and economic development.

Recent results showed the company translating this strategy into performance. Unicharm reported net sales of ¥988,981 million, up 5% year-on-year, and core operating income of ¥138,463 million, up 8.2%. It also described the period as an all-time record high for sales and core operating income, with Japan, India, the Middle East, and North America driving performance.

XI. The Investment Case: Bull and Bear Perspectives

If you step back from the history and look at Unicharm the way an investor does, you see a company with real, structural advantages—and a few very real ways the story can break. This is what the “great business” versus “great stock” debate looks like in hygiene.

Porter's Five Forces Analysis

Supplier Power (Low to Moderate): Unicharm buys largely commodity inputs—pulp, superabsorbent polymers, and nonwoven fabrics—from multiple sources. Costs can swing with commodity markets, but no single supplier appears to have the kind of chokehold that can dictate terms.

Buyer Power (Low to Moderate): Individual consumers don’t have leverage, but retailers do. Big chains can be tough negotiators. Unicharm’s protection here is the same thing that built the company in the first place: strong brands and leading market positions that retailers can’t easily replace without losing traffic.

Threat of Substitutes (Low): In baby diapers, cloth is the obvious alternative, but the long-term trend in most markets has been a steady shift toward disposables as incomes rise. In adult incontinence, substitutes are limited for many users; for a meaningful portion of the market, these products aren’t optional.

Threat of New Entrants (Moderate): Manufacturing scale, distribution, and brand trust create barriers. But the incumbents are formidable. When players like P&G or Kimberly-Clark decide a market matters, they have the capital and the playbooks to show up hard.

Competitive Rivalry (High): This is a brutal category. The fight is constant—innovation cycles, promotion pressure, and the ever-present threat of price wars. If you want calm, stable competition, personal hygiene is not the place to look.

Hamilton Helmer's 7 Powers Analysis

Scale Economies: Unicharm’s scale, particularly across Asia, is a real advantage. In several markets, its volumes are large enough to drive manufacturing and logistics efficiency that smaller rivals struggle to match.

Network Effects: There aren’t true network effects here in the classic sense. But there is social reinforcement: parents recommend what worked, and hygiene products are habit-driven. That creates a softer, word-of-mouth dynamic that can compound brand leadership.

Counter-Positioning: India is the cleanest example. By pushing pants-style diapers early and making them accessible, Unicharm forced incumbents into an awkward choice: respond quickly and cannibalize their tape franchises, or hesitate and give up the fastest-growing segment.

Switching Costs: Switching is easy on any single purchase. The “cost” is accumulated preference—once someone trusts a brand in a sensitive category, they tend to stick with it.

Branding: This is one of Unicharm’s strongest moats. Brands like MamyPoko, Moony, Sofy, and Lifree carry meaningful equity in their markets and can support pricing power when execution is strong.

Cornered Resource: Unicharm doesn’t have a single irreplaceable asset that no one else can access. What it does have is the next best thing: decades of accumulated know-how in absorbent materials and nonwoven processing that shows up in product performance.

Process Power: The company’s market-entry playbook and its management approach—today framed around faster decision cycles like the OODA Loop—function like a proprietary operating system. Competitors can copy pieces of it, but replicating the full machine is harder than it looks.

The Bull Case

The optimistic view starts with the obvious: Unicharm holds leading positions in many of the most attractive hygiene markets in Asia. It also benefits from two demographic forces that can run for years—aging populations that grow demand for adult incontinence products, and rising incomes in emerging markets that increase adoption of disposable baby and feminine care.

India is the headline opportunity. The India diapers market was valued at about USD 1,731.04 million in 2024, and is projected to grow at a CAGR of 15.3% from 2025 to 2034 to reach about USD 6,233.99 million by 2034. That’s a large expansion of the category in a country where Unicharm already holds the lead.

Layer on top of that the optionality: Southeast Asia still has room to grow, Africa is earlier in the adoption curve, and pet care adds a second engine with its own secular tailwinds from premiumization and “pet humanization.” Meanwhile, sustainability initiatives like diaper recycling can help Unicharm stay ahead of tightening expectations around waste and ESG.

The Bear Case

The pessimistic view begins with the reminder that Unicharm isn’t invincible—and China already proved it. Local competitors can close quality gaps quickly, and channel shifts like e-commerce can change the rules faster than established players adapt.

There’s also the unavoidable structural issue: Japan’s population is shrinking. Adult incontinence growth helps offset declines in baby care, but over time the domestic market is still a headwind.

Then there’s the constant margin risk. Emerging markets are often sold as “growth,” but growth can be expensive—especially when local players compete aggressively with promotions and low-priced products. That pressure can force painful tradeoffs between share and profitability.

Finally, Unicharm carries currency exposure. With such a large overseas business, the yen’s movement can create significant translation-driven volatility in reported results.

Key Performance Indicators for Monitoring

If you want two numbers that act like early-warning signals, they’re these:

-

Market Share in Key Growth Markets (India, Indonesia, Vietnam): Unicharm’s model depends on gaining share through product innovation and distribution reach. If share starts slipping in these markets, it’s often the first sign that execution or competitive dynamics have shifted.

-

Asia Segment Operating Margin: Asia is where most of the growth is, and it represents roughly two-thirds of revenue. Margin trends here tell you whether Unicharm’s expansion is compounding value—or buying growth at the expense of profitability.

XII. Conclusion: The Quiet Empire

Unicharm’s rise doesn’t fit the usual script for Asian corporate success. It wasn’t built on protected markets or a race to the bottom on cost. It was built the hard way: by competing on product performance, by manufacturing well, and by executing better than companies that were supposed to be unbeatable.

Look at the throughline. Keiichiro Takahara starts in construction materials, then makes the 1963 pivot into sanitary napkins that changes the company’s destiny. In 1987, Unicharm makes an uncomfortable bet on adult incontinence—years before Japan’s aging wave becomes impossible to ignore—and turns stigma into a market by framing the category around dignity and independence. Then, in 2001, Takahisa Takahara takes over and pushes Unicharm beyond a shrinking home market, applying a disciplined, repeatable playbook across Asia.

The pants-style diaper is the perfect distillation of how Unicharm wins. Spot a real consumer pain point. Build a technically superior solution. Then make it accessible enough that adoption can move from niche to default. It’s a simple formula, but Unicharm repeated it across categories and countries—and that repetition is what created the empire.

Keiichiro Takahara lived to see that transformation. At the time of his death in 2018, Forbes estimated his net worth at $5.2 billion. The company he founded as a construction materials business had become a global consumer products powerhouse. After his passing, Takahisa Takahara continued to lead Unicharm, keeping the same core emphasis on innovation and quality while pushing into the next chapters of growth.

Those next chapters won’t be easy. China was a reminder that competitors improve fast and channels can flip a market overnight. Japan’s demographic decline is a structural headwind, no matter how strong Unicharm’s domestic brands remain. And across Asia, price competition can squeeze margins even for the category leader.

Still, Unicharm is not short on ambition. It has set a goal of becoming the world’s leading company in terms of both relative and absolute value by 2030. Relative value, in the company’s framing, includes targets such as net sales of ¥1,500 billion, a core operating income ratio of 17%, ROE of 17%, and a leading global market share in nonwoven fabric and absorbent materials.

Put plainly, that’s a demand for the hardest kind of growth: getting bigger while also getting better. Pulling it off will require continued excellence in India and Southeast Asia, a smarter response to China’s realities, and good capital allocation in frontier markets like Africa, where category creation is still ahead.

For students of strategy, Unicharm’s lessons are unusually practical. Unglamorous businesses can produce extraordinary outcomes when they’re treated as technology and execution problems, not commodities. Demographics can be a competitive advantage if you act early enough. Emerging-market leadership is often earned over decades, not quarters. And family-controlled companies can do more than preserve—they can reinvent, if the transition is real.

In an era when tech dominates the conversation, Unicharm is a reminder that enormous value can be created by serving the most basic needs—babies, women, the elderly, and even pets—at massive scale. The quiet empire that began on Shikoku keeps expanding, one everyday product at a time.

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music