ASICS Corporation: The Shoemaker Who Accidentally Created Nike and Then Staged the Greatest Comeback in Sportswear History

I. Introduction & Episode Roadmap

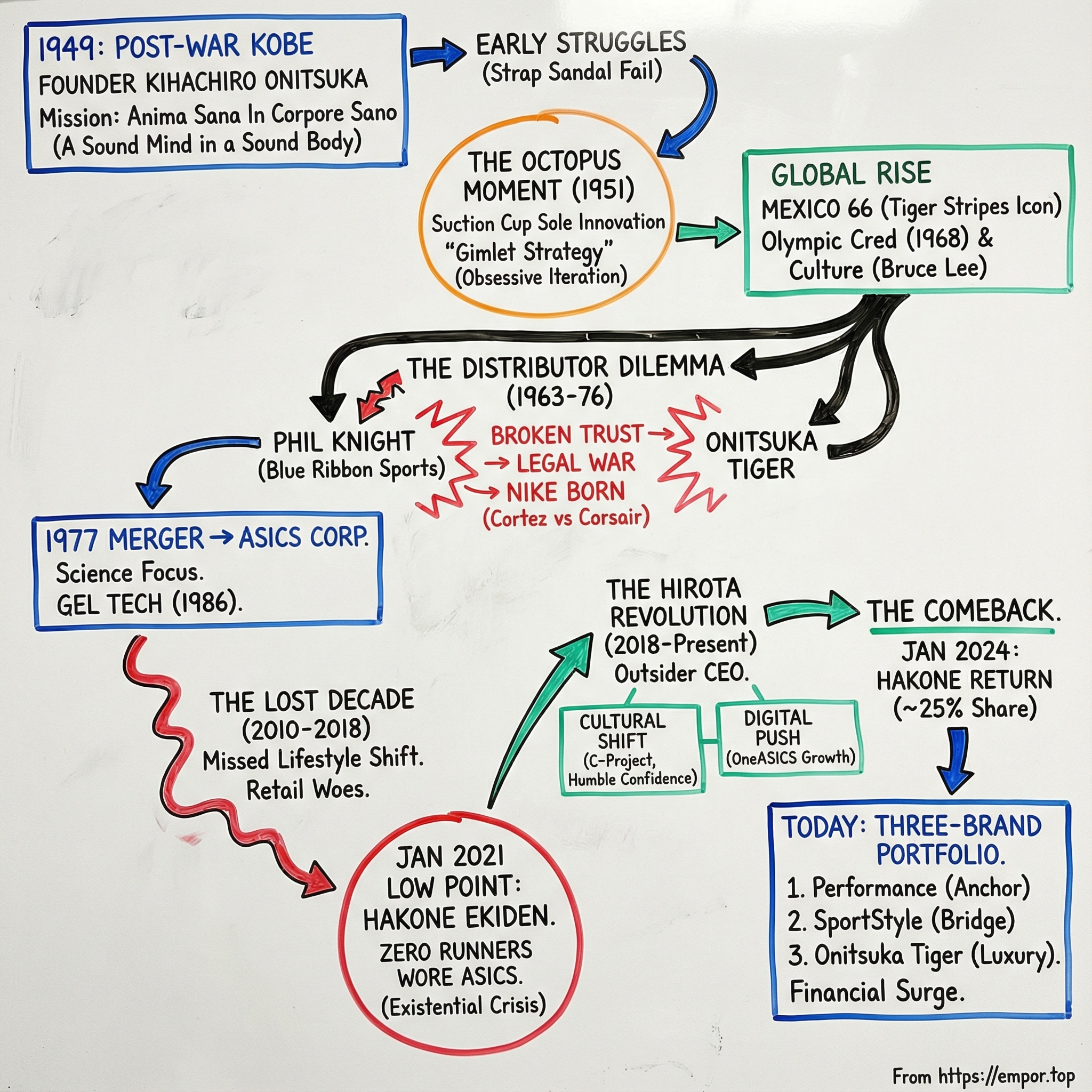

Picture this: it’s January 2021, and Japan’s most beloved collegiate race is on. The Hakone Ekiden, a two-day relay marathon from Tokyo out to the hot springs of Hakone, pulls in millions of viewers. For more than a century, it’s been a national ritual: 217 kilometers of grit, strategy, and suffering, broadcast like a holiday.

And for ASICS Corporation, that broadcast delivered a gut punch.

ASICS was born in Japan. It was built on running. Its headquarters sit a few hundred kilometers away in Kobe. And yet, across the entire field, not a single runner wore ASICS shoes.

For a company that helped define modern performance running footwear—one that has “a sound mind in a sound body” baked into its very name—that wasn’t just embarrassing. It was existential.

A few months later, at an Investment Day presentation in June 2021, CEO Yasuhito Hirota told the story plainly to investors. That kind of candor is rare in Japanese corporate life. But what made it more remarkable is what happened next: three years later, in January 2024, nearly a quarter of runners in that same race wore ASICS.

That swing—from the January 2021 low point to a return to cultural relevance—maps to one of the sharpest comebacks in modern sportswear. In fiscal 2024, ASICS grew net sales 18.9% to ¥678.5 billion. Operating profit jumped 84.7% to ¥100.1 billion, the first time the company ever crossed the ¥100 billion mark. Operating margin hit 14.8%, among the best in the industry, and ASICS said it showed the brand had reached “a completely different stage.”

But the real question—the one that makes this story worth telling—goes deeper than a great year.

How did a company that essentially gave birth to Nike, then wound up in a bitter legal war with that very distributor, and then spent much of the 2010s drifting toward irrelevance… manage to reinvent itself and roar back?

This is a story about Japanese craftsmanship colliding with global competition. It’s about octopus tentacles sparking product breakthroughs. It’s about a founder who’d rather be cheated than cheat someone else. And it’s about whether a 75-year-old brand can win in an era dominated by marketing machines—without betraying the simple Latin phrase at its core: Anima Sana In Corpore Sano. A sound mind in a sound body.

We’ll trace it from post-war Japan’s reconstruction, through the counterfactual that haunts the Nike-ASICS relationship, into the lost decade, and finally to a turnaround led by an outsider CEO who framed the challenge in an unusually humble way: compete in the world, not against it.

II. Post-War Japan & The Founding Spirit (1945-1949)

To understand ASICS, you have to start in Kobe in 1945: a port city flattened by American firebombing, its economy shattered, its streets filled with people trying to stitch daily life back together. This was Japan’s zero hour. And out of that wreckage came one of the most unlikely origin stories in global sportswear.

A 30-year-old war veteran named Kihachiro Sakaguchi returned to a country that didn’t just need jobs—it needed hope. During the war, his best friend had been sent to Burma. Sakaguchi, held back by compromised lungs, stayed in Tokyo as a supply officer. Before his friend left, Sakaguchi made a promise: if he didn’t come back, Sakaguchi would look after an aging, childless couple in Kobe whom his friend had grown close to.

His friend never returned.

Sakaguchi kept his word. He moved to Kobe, took the couple’s family name—Onitsuka—and began a new life shaped by loyalty and loss. That decision, made for deeply personal reasons, would ripple outward in ways he couldn’t have imagined.

After the war he tried the normal path, working as a salaryman. It didn’t last. His boss, he felt, cared only about his own interests. So Onitsuka walked away. And as a survivor looking at a generation of young people growing up amid scarcity and dislocation, he settled on a mission: help the youth of Japan become strong, healthy members of society.

The idea that unlocked everything was simple. Onitsuka heard a saying to the effect of: if you pray, pray for a sound mind in a sound body. To him, sport wasn’t entertainment. It was education—intellectual, moral, and physical. And he decided that the most direct way he could contribute was to make the thing that enabled sport: shoes.

A wartime friend, Kohei Hori—then Director of Health and Physical Education at the Hyogo Prefecture Board of Education—put a formal shape around that belief, introducing Onitsuka to the Latin phrase Anima Sana In Corpore Sano. The words hit him so hard they became a lifelong north star. Years later, they’d become the company’s very name: ASICS.

On September 1, 1949, Onitsuka formally founded Onitsuka Co., Ltd. The first product wasn’t a fashionable sneaker or a casual trainer. It was a basketball shoe, designed with a very specific purpose: rehabilitating post-war youth through sport.

The “company,” at first, was barely a company at all—Onitsuka, two employees, a desk, and a telephone. It was capitalized at 300,000 yen, a modest sum even then. But the ambition was enormous.

He also chose, deliberately, to start with what everyone told him was the hardest problem. Onitsuka believed basketball was about to take off in Japan, and he wanted to build the best basketball shoe in the country. His first attempts failed. That didn’t change the plan. He liked to say that if you begin with something difficult, everything after becomes possible.

That mindset became his signature. When Onitsuka committed to something, he threw himself into it completely. And he carried a moral code that people around him found almost extreme: he’d rather be cheated than cheat someone else. Colleagues began to describe him as honest to a fault.

The most remarkable thing about ASICS’ founding isn’t just the scrappy scale or the timing. It’s that purpose came first. Onitsuka didn’t discover a mission after finding success—he built the business to serve the mission. A war survivor trying to rebuild a nation through sport, one pair of shoes at a time.

That ethos—deeply Japanese, deeply idealistic—would become a powerful advantage. And, in later decades, a complicated constraint.

III. The Octopus Moment: Innovation Through Obsession (1949-1960s)

In the early days, Onitsuka didn’t look like the founder of a future global brand. He looked like a man stuck on a hard problem.

His first attempt at athletic footwear wasn’t a sleek basketball shoe at all. It was a strap sandal, closer to a traditional straw sandal than anything you’d see on a court. It flopped. So he went back to basics and fixated on the thing basketball demanded most: sudden starts, hard stops, sharp cuts.

He worked through trial after trial, and eventually brought a pair to a high school coach—hoping for validation, or at least a foothold.

Instead, the coach dismissed them. These could hardly be called basketball shoes, he was told. If Onitsuka wanted to make shoes for basketball players, he first had to understand basketball.

And then came the moment that turned into company lore.

One summer evening in 1951, Onitsuka sat down for dinner at home in Kobe. His mother served vinegared cucumber with octopus. As he stared at the dish, his attention snapped to the octopus tentacles—those neat rows of suction cups clinging effortlessly to the plate. The idea landed instantly: what if the sole of a basketball shoe could grip the floor the same way?

He tried it. The first prototype grabbed too well. Players stuck, tripped, and tumbled. So he adjusted—making the suction cups shallower, keeping the concept but tuning it for real movement: quick push-offs, controlled stops, fast changes of direction.

That iteration produced the Onitsuka Tiger basketball shoe that finally worked. And when a high school team wore them and won a championship, it wasn’t just a sales win. It was proof of a system: observe closely, build obsessively, test in the real world, and keep refining until the athlete says it’s right.

The octopus story matters not because it’s quirky, but because it captures how Onitsuka’s mind worked. He didn’t treat design as an art project. He treated it like problem-solving—pulling ideas from anywhere, then grinding them through feedback and experimentation.

But even a great shoe doesn’t matter if no one can buy it.

Onitsuka’s confidence rose as his products improved, yet brand awareness was basically nonexistent and distribution channels didn’t exist. So he became his own sales force. He traveled from region to region pitching shoes shop by shop, and to save money he often skipped inns and slept on benches in train stations.

It was punishing. He even began suffering from tuberculosis, and a doctor told him to be hospitalized immediately. He avoided the worst only because a new medicine had just become available.

Still, the work continued. Throughout the 1950s, the product line expanded step by step: the “suction cup” basketball shoes in 1951, the Marup marathon shoes in 1953, Nylon shoes in 1954, and the Magic Runner marathon shoes in 1960.

That shift into running wasn’t accidental. In 1953, Onitsuka partnered with marathon runner Toru Terasawa to build a shoe that would help long-distance runners avoid blisters—another example of his instinct to go straight to the athlete, understand the pain, then engineer the fix.

And sometimes his flashes of inspiration misfired. One day, riding through town in a taxi, he was thinking about how to keep marathon shoes from overheating. The cab overheated too, jerking to a stop with steam pouring out from under the hood. Water—cooling! It felt like another octopus moment. He tried the idea in footwear form. Unlike the suction-cup basketball sole, a hydraulically cooled running shoe turned into a heavy, soaked disaster.

But that was the point. Not every idea worked. What mattered was the habit: relentless experimentation, fast learning, and constant athlete input.

Onitsuka even had a phrase for it. He called it the “gimlet strategy”—drill deep in a narrow focus, master one field, and expand from there. The factory began producing many types of sports shoes, but it became obvious which products were breaking through. The Marup running shoes stood out, and by the late 1950s, the Tiger mark was on the rise. New categories followed: climbing boots, golf shoes, ski shoes, training shoes.

By 1955, the company was selling through around 500 sports shops across Japan. The distribution network that Onitsuka had built with sheer persistence was starting to scale beyond him.

And then, in 1964, came the moment that put a stamp on the first era of the company: Onitsuka listed the business on the Kobe Stock Exchange, and later on the exchanges of Osaka and Tokyo. In about fifteen years, the operation that began with a handful of people and a mission had become a public company.

More importantly, Onitsuka had built something bigger than a catalog of shoes. He had built a way of working—the Institute of Sport Science mindset years before there was an actual Institute of Sport Science. Prototype, test, listen, repeat. Win on performance, not hype.

That reputation for technical excellence would soon travel far beyond Japan. And it would catch the attention of a young American who believed Japanese shoes could take on the Germans—and who was about to change the sportswear world.

IV. The Mexico 66 & Cultural Iconography (1960s-1970s)

By the mid-1960s, Onitsuka Tiger had graduated from a scrappy domestic upstart into something much more dangerous: a technically credible brand that elite athletes around the world were starting to trust. But to take on Adidas and Puma on their home turf, performance wasn’t enough. Onitsuka Tiger needed a signature—something you could recognize from across a track, or across the street.

That’s where the Mexico 66 came in.

In 1966, the company set out to solve a branding problem with the same mindset it used to solve an outsole problem: iterate until it’s right. After studying roughly 200 variations, Onitsuka Tiger landed on a curving, intersecting stripe design that did double duty—reinforcing the upper while making the shoe unmistakable. Those lines became the Tiger Stripes: two vertical lines crossed by a pair that sweep forward from the heel. It was identity, built into the product.

The first model to carry the stripes was the Mexico 66, released two years ahead of the 1968 Olympic Games in Mexico City to build momentum. It worked. As athletes wore the shoe in competition, adoption spread—eventually reaching even the Japanese national team at the Games. Japan went on to win 11 gold medals in 1968, and Onitsuka Tiger had the kind of global-stage validation money can’t buy.

The momentum wasn’t just Olympic. It was consumer, too. In the first Runner’s World shoe guide in 1967, the Tiger Road Runner was named the top training shoe, and the Tiger Marathon was named the best racing shoe. By 1971, Runner’s World reader preferences showed more than 60 percent of surveyed runners were in Tiger shoes. The first global running boom was underway, and Onitsuka Tiger was right at the center of it—winning both among elites and among everyday runners.

Then came Montreal in 1976. Kihachiro Onitsuka was 58, and the company was operating at the peak of its early era. That year, Finnish legend Lasse Virén won both the 5,000 and 10,000 meters wearing Onitsuka Tigers—after having won those same events in Adidas in 1972. And when Virén took his victory lap barefoot, holding the shoes above his head, it was a moment that every brand dreams about: completely authentic, completely unforgettable.

But the Mexico 66’s most durable impact didn’t come from the track. It came from culture.

In the 1978 film Game of Death, Bruce Lee wore a yellow-and-black shoe that looked strikingly similar to the Mexico 66. There’s debate about the exact model—some say Mexico 66, others say it was the Tai Chi—but the outcome was the same: the silhouette became a pop-culture reference point, and Onitsuka Tiger suddenly had relevance beyond running.

Decades later, the loop closed again. In 2003, Uma Thurman wore gold-colored Onitsuka Taichi sneakers with black stripes in Kill Bill, paying homage to Lee’s iconic look. Once again, there were disputes over which exact shoe it was—but once again, it was the Mexico 66 that reaped the benefits.

From a business perspective, that’s the magic of the Mexico 66 story. This wasn’t a shoe launched as a fashion play. It was a serious athletic product that, almost by accident, earned cultural iconography. And that kind of organic placement—earned, not bought—creates brand equity that can last for generations.

By the mid-1970s, Onitsuka Tiger had built a rare trifecta: technical credibility, Olympic-stage legitimacy, and a toe-hold in global popular culture. It was a powerful position.

And it set the stage for the relationship that would reshape the entire industry—because the next chapter introduces a young American distributor who would turn into Onitsuka Tiger’s greatest competitor.

V. The Nike Story: When Your Distributor Becomes Your Greatest Competitor (1963-1976)

This is the counterfactual that haunts the entire ASICS narrative: the moment a Japanese shoemaker took a bet on a young American—and accidentally helped create the company that would go on to dominate the industry.

It starts with Phil Knight at Stanford Graduate School of Business. For a small business class, he wrote a paper with a title that reads like prophecy: “Can Japanese Sports Shoes Do to German Sports Shoes What Japanese Cameras Did to German Cameras?” The thesis was simple: Japan could make great products at lower cost, and the U.S. running market was ripe for disruption.

After earning his MBA in 1962, Knight took a trip around the world. In November, he stopped in Kobe, Japan—and found Onitsuka Tiger running shoes.

He managed to get a meeting with Onitsuka. Early in the conversation, the Onitsuka staff asked a basic question: what company are you with?

Knight didn’t have one. So he made one up on the spot. His childhood bedroom, he remembered, had been lined with blue ribbons from track meets. “Blue Ribbon Sports of Portland, Oregon,” he said. A company name invented in mid-sentence.

Then he did what good founders do: he sold the vision. Knight was a runner himself, with a personal best of 4:13 in the mile, and he believed performance footwear mattered. He walked them through his Stanford paper, laying out the market, the opportunity, and how a Japanese brand could undercut Adidas, which dominated at the time.

The Onitsuka executives were intrigued. They told him they’d been thinking about entering America for a long time. They showed him Tiger models they thought could work. And by the end of the meeting, Knight had what he came for: distribution rights for Onitsuka Tiger in the western United States.

Years later, Kihachiro Onitsuka explained why he said yes. Phil Knight’s ambition reminded him of his younger self. A founder who once slept on train station benches saw that same restless energy in this young American and decided to trust it.

The first Tiger samples took more than a year to reach Knight. While he waited, he worked as an accountant in Portland. When the shoes finally arrived, he immediately mailed two pairs to Bill Bowerman, Knight’s former track coach at the University of Oregon—hoping for a sale, and maybe an endorsement.

What he got was far bigger. Bowerman ordered the shoes, then offered to become Knight’s partner and contribute product design ideas. On January 25, 1964, the two sealed their partnership with a handshake. Blue Ribbon Sports was born—the company that would eventually become Nike. Knight sold his first pairs the scrappy way: out of the trunk of his green Plymouth Valiant at track meets across the Pacific Northwest.

For nearly a decade, Blue Ribbon Sports was Onitsuka Tiger’s engine in America. In fact, Knight was the first to import Japanese athletic shoes into the U.S. at scale, and within six years Tiger had captured the majority of the American market.

And then the relationship that created all that momentum started to rot.

By the early 1970s, despite an exclusive three-year agreement, trust between the companies was breaking down. Blue Ribbon believed Onitsuka was looking for a new U.S. distributor behind its back—even after renewing the partnership. Onitsuka, meanwhile, was making life harder on the ground: late shipments, incorrect models, wrong sizes. The Cortez was flying off shelves, but instead of Cortezes, boxes would show up filled with Bostons, sometimes in sizes retailers couldn’t sell.

Knight came to believe it wasn’t incompetence. It was prioritization: satisfy Japan first with limited supply, and ship whatever was left to the U.S.

At the same time, Blue Ribbon began making its own move. At the end of 1971, it started producing and selling shoes under its own brand: Nike. That step—creating a competing line while still tied to Onitsuka—pushed a strained partnership toward open conflict.

Both sides told very different stories. Knight claimed Onitsuka wanted out of the exclusivity deal and was trying to squeeze Blue Ribbon until it broke. Onitsuka claimed it discovered Blue Ribbon selling its own version of the Tiger Cortez under the Nike name. The dispute landed in court, and a judge ultimately ruled that both companies could sell their own versions of the design. Nike kept the “Cortez” name; Onitsuka Tiger renamed its version the “Corsair.”

The legal fight ended with an out-of-court settlement. Onitsuka agreed to pay Blue Ribbon Sports, and the company incurred more than 100 million yen in legal fees and settlement costs before it was over.

The business lesson is as brutal as it is timeless. Onitsuka didn’t just grant a distributor access to a product line—it effectively opened a door to the entire running shoe playbook: manufacturing, athlete relationships, feedback loops, and product innovation. Once the relationship collapsed, that knowledge didn’t disappear. It reemerged as Nike.

And from that point on, Onitsuka Tiger wasn’t just competing with Adidas and Puma. It had helped create a new rival—one that would soon reshape the industry in its own image.

VI. The 1977 Merger & The ASICS Era (1977-2000s)

The late 1970s forced a hard reality on Onitsuka Tiger. Nike was no longer a quirky distributor-turned-upstart—it was becoming a serious threat in the U.S. Adidas and Puma still owned the global narrative. And Onitsuka understood what that meant: in sportswear, great product alone doesn’t protect you. You need scale.

So in 1977, he made the biggest structural move of his career. Onitsuka Co., Ltd. merged with fishing and sporting goods company GTO and athletic uniform maker Jelenk to form ASICS Corporation, with Onitsuka named president. Three companies—footwear, sporting goods, and uniforms—rolled into one, designed to compete in a world that was getting bigger and more brutal by the year.

The new name wasn’t a marketing brainstorm. It was the mission, formalized: ASICS, from the Latin phrase anima sana in corpore sano—“a sound mind in a sound body.” It was the same idea that had sparked the company in the first place, now stamped onto a global corporate identity.

The merger also unlocked a broader strategy. With more capability under one roof, ASICS could diversify its product lineup and push further overseas. The groundwork had already been laid: a U.S. subsidiary had been established in 1973, and in 1975 the company set up Onitsuka Tiger GmbH in Düsseldorf, Germany. Now the organization behind those efforts finally matched the ambition.

The 1980s became a decade of building—especially in the place ASICS always believed it could win: science. In 1985, the company launched the ASICS Institute of Sport Science, putting structure and budget behind the obsessive athlete-first experimentation that had defined Onitsuka from the beginning.

Then came the technology that would define the brand for a generation. In 1986, ASICS introduced GEL cushioning, using silicone-based inserts encased in resin to reduce impact forces during heel strike. Internally and externally, GEL became the shorthand for what ASICS stood for: comfort you could measure, not just claim. As AJ Andrassy, Global Director of Performance Running Footwear for ASICS, put it: “GEL™ is our most iconic and legendary technology.” And it stayed in the product line for decades because it worked.

In 1990, ASICS deepened that commitment with a dedicated research facility in Kobe City, Japan: the ASICS Research Institute of Sports Science, built to study natural human form and movement and translate that data into product development.

Throughout the 1990s, the company kept stacking credibility with serious runners. Portuguese marathon runner Rosa Mota, sponsored by ASICS, became a European champion in 1986, a Rome champion in 1987, and in 1988, the first female Portuguese gold medalist. Wins like those didn’t just sell shoes—they reinforced a reputation: ASICS was for people who took running seriously.

And then, in 2002, ASICS made a move that looked small at the time—but turned out to be a preview of the future. The company relaunched Onitsuka Tiger, leaning into the growing appetite for vintage sneakers. A year later, the cultural flywheel spun again when Uma Thurman wore gold-colored Onitsuka Taichi sneakers with black stripes in Kill Bill. The Onitsuka Tiger revival became ASICS’s first meaningful step into lifestyle—a category that would matter enormously later, even if the company didn’t fully realize it yet.

The founder didn’t live to see the full arc. On September 29, 2007, Onitsuka died, ending the era he’d personally shaped from the very first prototypes. Until the end, he stayed involved—serving as chairman, still thinking in sketches and experiments.

By that point, Onitsuka Tiger had opened 23 standalone stores. In 2008, it pushed further upmarket with Nippon Made, a premium series handcrafted in Tokyo using high-end materials—heritage, turned into product.

By the late 2000s, ASICS had locked in a powerful position: scientific research, real technology, and credibility with elite athletes and serious runners. The problem was that it had also locked itself into a narrow identity. As the sportswear world shifted toward lifestyle, fashion, and athleisure, being “the serious running brand” would start to look less like a moat—and more like a constraint.

VII. The Lost Decade: When Running Wasn't Enough (2010-2018)

The years from 2010 to 2018 were ASICS’s corporate wilderness—when the thing it did best gradually stopped being enough.

For decades, ASICS had been the brand for serious runners. That identity was earned the hard way: labs, testing, athlete feedback, and products that delivered. But while ASICS was doubling down on performance, Nike and Adidas were expanding the definition of “sportswear” itself. They were becoming lifestyle brands that happened to make athletic gear. And the center of gravity in the market moved with them.

ASICS did have momentum early in the decade. Revenue cleared ¥200 billion in 2011. Then the growth sputtered. Targets got missed. The company found itself running harder just to stay in place.

The problem wasn’t that running disappeared. It was that the consumer did. The shift began in the U.S., where demand moved away from the pure running enthusiast—ASICS’s sweet spot—and toward lifestyle and athleisure. At the same time, the way products were sold was changing fast. Channels were tilting toward direct-to-consumer and digital. ASICS wasn’t set up to win that transition.

You can see the internal strain in the company’s own planning. In 2015, ASICS announced an ambitious medium-term plan: ¥750 billion in sales and an operating margin of 10% or more by 2020. By February 2018, progress was slow enough that the company had to reset expectations—cutting the target to ¥500 billion in sales and a 7% margin.

By then, the pattern was clear. Net sales in the three years leading up to 2018 were stuck around the ¥400 billion level. At the same time, selling, general, and administrative costs kept rising—because even when revenue stalls, a global organization still carries global overhead. Profitability slid. In 2018, ASICS posted a loss of 20 billion yen, about $175 million, according to its annual report.

The pain was especially visible in North America, the most important and most competitive sportswear market on earth. ASICS struggled there for years, even before COVID. Sales fell again during the pandemic in 2020, but they’d already been declining for four straight years. Around 2010, Brooks passed ASICS in market share in the run specialty channel. Later, Hoka and On intensified competition in the same places ASICS had historically been strongest.

Then came a gutting operational blow. In January 2016, Windsor Financial Group LLC—the operator of ASICS stores in the U.S.—filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy protection amid a dispute with ASICS. The breakup led to the closure of 13 full-price stores in late 2015 and escalated into a lawsuit. At the exact moment competitors were investing heavily in direct-to-consumer, ASICS’s U.S. retail footprint weakened.

Underneath the channel problems was a deeper one: perception. ASICS was widely recognized in running, but its appeal in adjacent categories—lifestyle, fashion, general fitness—was limited. To many consumers, ASICS didn’t feel like a brand you wore all day. It felt like a brand you trained in. Meanwhile, Nike and Adidas were selling a broader identity: performance plus style, sport plus culture.

ASICS also had work to do in digital. In a world where the biggest brands were building sophisticated online ecosystems, ASICS was seen as behind—needing to upgrade its e-commerce experience and catch up to the expectations consumers were learning from the category leaders.

And although it sits outside this 2010–2018 window, the most vivid symbol of where all this led arrived soon after: in January 2021, not a single runner wore ASICS at the Hakone Ekiden. A Japanese running company, absent from Japan’s most important running event. It was a public, unmistakable sign that the brand had drifted from the center of the sport it helped define.

ASICS hadn’t forgotten how to make great product. But product alone wasn’t winning anymore. The company that pioneered performance running was being outmaneuvered—by faster competitors, changing tastes, and a retail world that no longer rewarded the old playbook.

Something fundamental had to change.

VIII. The Hirota Revolution: Outsider CEO, Radical Transformation (2018-Present)

The turnaround starts with an unlikely protagonist: a career executive with no footwear background who later admitted he took the job with “a somewhat casual attitude.”

Yasuhito Hirota joined ASICS in January 2018, right as the company was running out of excuses and running out of time. At the time, he was serving as General Manager of the Kansai Branch at Mitsubishi Corporation when former ASICS President Motoi Oyama approached him. Would he consider taking over? Hirota thought it sounded interesting—and said yes, almost nonchalantly.

That outsider perspective turned out to be the point.

Hirota had just come from Mitsubishi Corp., where he served as a Representative Director from 2017 to 2018. He was brought in by Oyama—who wasn’t just a former CEO, but also the son-in-law of ASICS founder Kihachiro Onitsuka. In other words: the founder’s family was recruiting an external operator to reset the company.

Over the next few years, Hirota would move through the top roles: Chief Operating Officer from 2018 to 2023, Chief Executive Officer starting in March 2022, and Chairman beginning in January 2024.

But titles weren’t the strategy. The strategy was how he approached change.

Hirota described transformation as having two phases. The first is structural: change how the company is organized and how decisions get made. The second is cultural: change how people communicate and what they believe is possible.

He started with communication in a way that would’ve felt almost alien in traditional Japanese corporate life. “Since my appointment as president,” Hirota said, “I have been posting an internal blog every two weeks without fail.” Early posts were personal—stories about running marathons. Over time, the blog shifted into a running narrative of the turnaround itself: what he was trying to do, why, and what he needed from the organization. Employees could reply anonymously, and they did. The feedback was blunt. And Hirota welcomed it.

It sent a signal: this wasn’t going to be a turnaround built purely on spreadsheets. It would require rewiring how the company talked to itself.

Then came structure.

About 18 months earlier, Hirota—then COO—had pushed the organization to form a special unit called the C Project. It was deliberately cross-functional, pulling in younger talent from the Institute of Sport Science, Marketing, Product Development, Manufacturing, and Legal & IP. And it reported directly to him, stripping out layers so information could move faster and decisions could happen without getting stuck in the corporate machinery.

That team delivered quickly. Using data and athlete insight, they developed two new performance running models—METASPEED™ Edge and METASPEED™ Sky—built on a simple but powerful premise: different runners need different solutions. Those shoes became central to ASICS’s recovery in performance running, because they weren’t just “new.” They were credible.

Hirota anchored the whole effort in a philosophy that fit ASICS’s DNA. To compete with giants, he argued, ASICS couldn’t out-shout them. It had to out-build them. “Through our technological capabilities and craftsmanship,” he said, “we will develop record-making products that are safe, secure, and comfortable.” And internally, he reframed the company’s global ambition with unusual humility: it wasn’t about competing “against” the world, but competing “in” the world.

The other pillar was digital.

As ASICS pushed to modernize, Mitsuyuki Tominaga played a key role “particularly in promoting the digitalization of ASICS” from 2018 onward. And the company began building what it had lacked for years: a direct relationship with consumers at scale. In 2018, the first year the loyalty program launched, it gained 700,000 members. Five years later, in 2023, it had grown more than tenfold to over 8.3 million members globally. Under the ASICS 2023 plan, OneASICS membership expanded to 9 million—well above the company’s own targets.

The turnaround showed up in the numbers, too. From 2015 to 2020, ASICS revenue shrank from $3.7 billion to $3.1 billion. Starting in 2021, the trend reversed. By 2023, revenue reached $4.01 billion—up more than 29% in just a few years, and the highest in the company’s history.

And then there was the ultimate proof point, back where we began.

In January 2021, ASICS had been invisible at the Hakone Ekiden—zero runners. Three years later, in January 2024, 24.8% of runners wore ASICS. From none to nearly a quarter of the field.

For a brand built on performance, it wasn’t just a nice comeback story. It was validation that the product engine was running again—and that the cultural reset behind it was real.

IX. The Lifestyle Explosion: SportStyle & Onitsuka Tiger's Renaissance (2020-Present)

The Hakone Ekiden comeback proved the performance engine was alive again. But the real plot twist in the turnaround came from somewhere ASICS had long struggled to matter: lifestyle.

What started as a quiet heritage thread—old silhouettes, old logos, a little nostalgia—turned into a second pillar of the company. And not just a “nice to have” pillar. A high-growth, high-profit one.

ASICS itself described the setup plainly: even as it remained a leader in performance running, the outsized growth was now coming from sports lifestyle and street lifestyle. SportStyle and Onitsuka Tiger were each growing more than 50% year over year and pushing toward roughly ¥100 billion in sales apiece.

ASICS said that, by category, SportStyle and Onitsuka Tiger had become the second pillar after Performance Running. Both delivered around ¥100 billion in net sales, with SportStyle up 66.1% from the prior year and a profit margin of 27.3%.

SportStyle is the bridge between old and new ASICS: retro aesthetics, modern comfort, and the credibility of a brand that still knows how to build a real performance shoe. By early 2025, the momentum was still accelerating. In the first quarter of fiscal 2025, SportStyle sales rose 49.6% year over year to ¥35.1 billion, with North America and Europe leading the charge. And within the line, two models did the heavy lifting: the GEL-1130 and the GT-2160—shoes that landed squarely with Gen Z and millennials and helped drive the quarter’s triple-digit growth in key markets.

Onitsuka Tiger is a different animal. It’s ASICS’s luxury lifestyle subsidiary—less “running store” and more “global fashion map.” Net sales in the category grew 57.2% year over year, and profit grew 51.4% to ¥39,363 million. The category ran at a 34.0% profit margin, up 850 basis points from the prior year and the highest profitability of any ASICS category.

And the brand has leaned into that positioning. In 2024, Onitsuka Tiger marked its 75th anniversary and used the moment to go bigger globally: opening Hotel Onitsuka Tiger on the Champs-Élysées in Paris, showing up at Milan Fashion Week, and collaborating with other brands. ASICS also pointed to efforts to elevate Onitsuka Tiger’s value worldwide, including opening a flagship store in Barcelona.

This surge didn’t happen in a vacuum. It rode a broader wave—rising global interest in Japanese fashion, nostalgia-driven sneaker demand, and a consumer move toward “elevated casual” footwear. ASICS was unusually well positioned for that moment, especially with heritage silhouettes like the GEL-1130 and the GEL-NYC.

The most important part, though, wasn’t just that lifestyle was growing. It was that lifestyle was throwing off cash.

ASICS disclosed that category profit for both SportStyle and Onitsuka Tiger exceeded ¥30.0 billion. Profit margins climbed to 30.6% for SportStyle and 39.4% for Onitsuka Tiger—well above what performance running typically generates. Lifestyle wasn’t merely helping ASICS grow. It was changing the economics of the whole company.

Japan’s tourism boom added fuel. ASICS said inbound tourist sales “increased significantly,” reportedly up around 150% year over year, benefiting both Onitsuka Tiger and ASICS more broadly. But the company also framed the opportunity carefully: capturing tourist demand is great, but building durable demand in local markets is what makes a trend into a business.

X. The Three-Brand Strategy: Portfolio Architecture

ASICS’s comeback makes a lot more sense once you see how the company is organized today: not as one brand trying to be everything to everyone, but as a portfolio with clear lanes.

In ASICS’s three-brand strategy, ASICS is the performance engine—built for sport, anchored in running, and protected by the company’s credibility in technical product. ASICS Tiger, now expressed through SportStyle, is the bridge: retro silhouettes and everyday wear, backed by comfort and materials that still feel like they came from a serious footwear company. And Onitsuka Tiger sits at the top: premium positioning, fashion credibility, and designer collaborations.

Crucially, SportStyle and Onitsuka Tiger aren’t side projects anymore. ASICS described them as the “second pillar” alongside Performance Running, with each reaching about ¥100 billion in net sales.

That portfolio shape shows up in the mix. In fiscal 2023, about half of the company’s income came from performance running shoes. Roughly a third came from other footwear, with apparel and equipment making up a small slice, and Onitsuka Tiger contributing a meaningful share on its own. Geographically, sales were spread across Japan, North America, Europe, China, and other regions—no single market carrying the whole story.

Performance Running as the Anchor: Even with lifestyle surging, ASICS’s core performance running remains the foundation and the strategic centerpiece. Performance Running net sales increased 10.1 percent, and the category profit margin improved by 1.7 percentage points to 25.5 percent. The company’s objective is direct: become the dominant No. 1 performance running footwear brand.

That matters because performance running does three jobs at once. It preserves ASICS’s identity as a serious athletic brand. It provides steadier demand, driven by training cycles rather than trend cycles. And it lends authenticity to everything else—because if the running product isn’t real, the heritage and retro stories don’t land the same way.

The Risk of Lifestyle Dependence: The flip side is that lifestyle, especially Onitsuka Tiger, lives closer to discretionary spending and trend momentum. Keeping that business strong will take more than hype. It will take sustained brand-building that can outlast a hot moment—or a tourism spike.

Tourism has clearly helped. ASICS noted that Japan’s inbound recovery boosted Onitsuka Tiger, including growth of 112.8% in H1 2024. But that also introduces risk: if travel patterns cool, you don’t want the economics of your most profitable brand cooling with them. The company’s advantage is that it isn’t only a Japan story—it has a global footprint and has been working to build real local demand.

The Portfolio Balance Challenge: A three-brand architecture creates leverage, but it also creates tension. Performance ASICS competes internally for attention and resources with SportStyle. SportStyle overlaps at the edges with Onitsuka Tiger. Growing all three without blurring the lines—or cannibalizing one brand to feed another—requires constant choreography.

When it works, though, it gives ASICS something surprisingly hard to build in sportswear: performance credibility and lifestyle pull, under one corporate roof. And that balance—technical innovation on one side, fashion and culture on the other—is exactly where even giants like Nike and Adidas can struggle to stay perfectly in tune.

XI. Porter's Five Forces & Hamilton's 7 Powers Analysis

Now that we’ve got the narrative arc—the near miss with Nike, the lost decade, and the Hirota-led comeback—the next question is the one investors and competitors always end up asking:

How defensible is this?

To answer that, we’ll look at ASICS through two lenses. First, Porter’s Five Forces: the classic map of industry pressure. Then Hamilton Helmer’s 7 Powers: the question of whether ASICS has built any advantages that can actually compound over time.

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music