TOPPAN Holdings: From Meiji-Era Printing House to Global Technology Conglomerate

I. Introduction & Episode Roadmap

Picture Tokyo in 1900. Gas lamps flicker on narrow streets in a country that, only a generation earlier, had ended centuries of isolation. Modernization is no longer a slogan; it’s infrastructure. Railroads cut across the landscape, telegraph lines carry urgent messages, and a young emperor presides over a nation determined to stand shoulder-to-shoulder with the West.

In a small printing shop in the Shitaya district, five technicians lean over copper plates, refining a demanding craft: relief printing, learned through the Ministry of Finance’s printing world and shaped by the teachings of an Italian advisor. They aren’t trying to build an empire. They’re trying to make printing more precise, more secure, more reliable. But in doing that, they’re lighting the fuse on one of the most surprising corporate evolutions in modern Japanese industry.

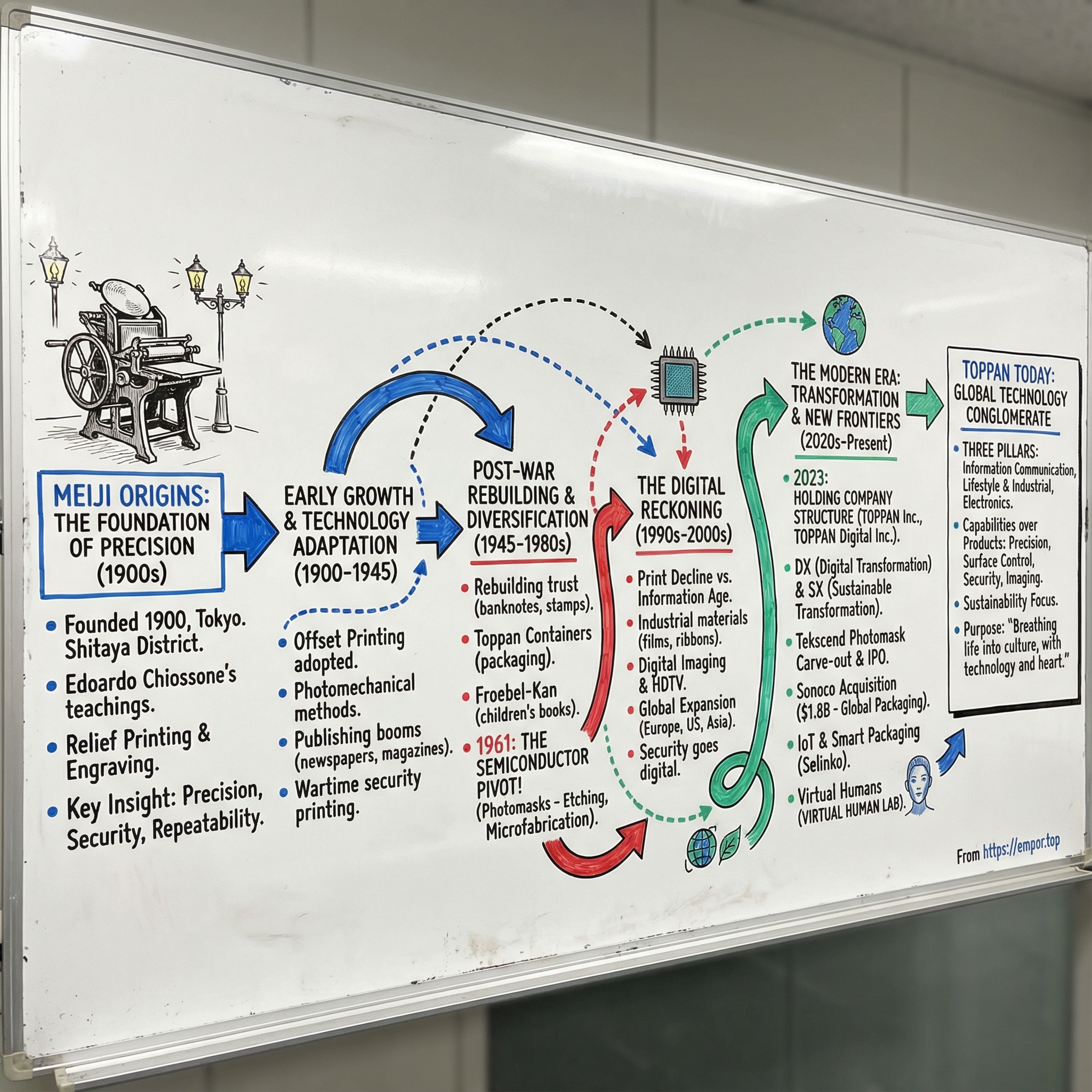

Founded in Tokyo in 1900, the TOPPAN Group began as a printing company. Today, it’s a diversified global provider of integrated solutions across printing, communications, security, packaging, décor materials, electronics, and digital transformation—with sustainability increasingly at the center of the portfolio.

That brings us to the question that powers this whole story: how does a 125-year-old printer become a world leader in semiconductor photomasks, smart packaging, and even virtual human technology?

The answer isn’t one big pivot. It’s a repeatable habit: extracting new value from old capabilities.

The metalworking and etching techniques that once helped protect securities from counterfeiting become the foundation for microfabrication. The color and image-control know-how that made ink on paper look “right” becomes the kind of color management you need for modern displays. The company’s long-running security mindset—how to authenticate, how to prevent fraud, how to manage trust—moves from certificates and documents into digital identity and information protection.

And the portfolio tells the story in plain terms. Today, less than 30% of TOPPAN’s business is printing on paper.

What replaced it is a three-part operating engine. The Information Communication Business spans everything from securities and cards to printed materials and business process outsourcing. The Lifestyle and Industrial Business covers packaging and construction-related materials, from cartons and flexible packaging to decorative and functional films and sheets. And behind both sits the same underlying pattern: high-precision manufacturing married to information, design, and security.

So this isn’t just a story about printing. It’s a story about longevity through reinvention—about what happens when a company treats “what we’re good at” as portable, and “what we sell” as negotiable. Strategic patience. Technology transfer. And the willingness to outgrow your own name, without losing the skills that made you matter in the first place.

II. The Meiji Origins: Printing as Nation-Building

The story really starts a couple decades earlier, inside a government workshop.

In the 1880s, Japan’s Ministry of Finance Printing Bureau brought in an Italian engraver named Edoardo Chiossone. His job wasn’t “design.” It was nation-building through trust: train Japanese technicians to produce banknotes and securities that were consistent, hard to copy, and credible at a time when the country was racing to modernize.

Chiossone taught a demanding relief-printing approach known as the Erhöht letterpress method. It relied on fine engraving and obsessive process control—exactly the kind of craft that makes counterfeiting difficult. Two young engineers in the Bureau, Enkichi Kimura and Ginjiro Furuya, became students of that craft, absorbing not just the technique, but the mindset behind it: precision, repeatability, and security.

By the late 1890s, they could see what the government couldn’t easily pursue on its own. Japan’s industrialization was exploding the need for securities, business forms, and sophisticated packaging—work where Erhöht’s precision and anti-forgery strengths weren’t a nice-to-have, but the product. In 1899, Kimura drew up a charter for a new venture: a copper letterpress and lithographic printing house.

A year later, in Tokyo’s Shitaya Ward at 1 Nicho-machi, Kimura and Furuya joined with three investors—Kishi Ito, Tatsutaro Kawai (who would become the first president), and Shinjiro Miwa—to establish Toppan Printing Limited Partnership.

The timing was both perfect and punishing. The Sino-Japanese War of 1894 had already driven a surge in demand for printed materials as newspaper readership grew and documentation needs multiplied. But right after Toppan opened its doors, the business climate turned: in 1901, a slump hit printing and papermaking as the wartime boom cooled off.

What saved them wasn’t scale. It was focus. The founders bet on high-security, high-precision work instead of commodity volume printing—jobs where quality, consistency, and trust commanded a premium. And then history, again, rewrote the demand curve. In 1904, the Russo-Japanese War triggered another sharp rise in newspapers and magazines. Japan’s victories, paired with the modern currency system established in the 1880s, helped push the country into a new phase of military and economic expansion—and with it, a new phase of printing demand.

And this is the important part: the company’s early “printing” advantage was never just ink on paper. It was the ability to manipulate surfaces with microscopic precision, to run controlled processes that produced the same result every time, and to build products where authenticity mattered. That DNA—precision manufacturing plus security thinking—would get copied and pasted into everything TOPPAN became next.

III. Early Growth & Technology Leadership (1900-1945)

In 1908, Toppan made its first big structural step up. It doubled its capitalization to 400,000 yen, reorganized as Toppan Printing Co., Ltd., and expanded beyond pure printing into binding and the manufacture and sale of movable type casts. In other words: don’t just run the presses—own more of the process around them. Prepress, print, finishing. Control the workflow, control the quality, control the economics. It’s a playbook TOPPAN would keep refining for the next century.

Then came a preview of how the company handled technological disruption—messy, human, but ultimately pragmatic.

A Toppan employee named Gennojo Inoue saw something in offset printing that others didn’t: better color, better images, a fundamentally different way to put ink on a page. He pushed the company to adopt it. The answer was no.

So Inoue did the most “startups inside incumbents” thing imaginable—except this was 1913. He left, gathered colleagues, and founded the Offset Printing Company, importing color offset technology from the United States and Europe. The new firm worked. It won business. It took share.

Four years later, Toppan bought the company back and brought Inoue in as an executive. The message was clear: Toppan might resist at first, but it would not ignore proven advantage for long. If the new technology was real, it would get pulled into the core.

In 1920, again under Inoue’s drive, photomechanical printing was introduced to Japan. Through the 1930s, Toppan kept growing, becoming one of the country’s largest printing concerns—built on a willingness to absorb whatever technique produced better fidelity, higher throughput, or tighter control.

The 1920s helped. Japan’s publishing market surged; by 1927, there were almost 20,000 new book titles and 40 million magazines being published. More pages meant more opportunity for the companies that could produce them reliably at scale.

But the tailwinds didn’t last. In the 1930s, as Japan slid into military dictatorship, the culture that fed publishing began to constrict. Writers and publishers were suppressed, books were banned, and the whole ecosystem that had driven growth started to shrink. And as the country moved toward war, the problems became physical as well as political—paper shortages and a weakening economy hit the industry hard.

During World War II, Toppan’s most distinctive capability—security printing—made it useful to the state. The company produced currencies, bonds, government securities, and propaganda materials. It kept operating, but in a way that tied its fortunes tightly to the war effort, and to the destructive realities that came with it.

IV. Post-War Expansion & Diversification (1945-1980s)

Japan emerged from World War II battered, rebuilding not just cities and factories, but the basic machinery of trust: documents, stamps, certificates, the paper infrastructure of an economy trying to restart.

For Toppan, this was a moment when its origin story suddenly mattered again. The company had been founded by technicians trained in the Ministry of Finance’s printing world, and that security-document DNA became immediately useful. In air raids, the Ministry of Finance’s printing facilities and equipment for producing stamps had been destroyed. So work that would normally stay inside the government flowed outward to private printers—and Toppan was ready. It secured orders for stamps, and when regional lottery ticket issuance was permitted, it won contracts for the first formal regional lottery tickets for Fukui, Kanagawa, and Niigata. In the postwar era, government work wasn’t just revenue; it was a long-term anchor client that kept the presses running and reinforced Toppan’s reputation for reliability.

Then the broader economy took over. As Japan’s postwar growth accelerated, Toppan began to look less like a printing firm and more like an industrial platform built around precision manufacturing.

In 1952, it founded Toppan Containers to make specialty cardboard and packaging materials—an early sign that “printing” would increasingly mean functional materials as much as ink. And in 1959, as major publishing houses launched successful weekly magazines, the country’s reading boom helped drive demand for high-volume periodical production.

But if you want the year when the company’s future started to split into multiple lanes, it’s 1961.

That year Toppan acquired Froebel-Kan, a company specializing in children’s products, which grew into a major lineup of children’s books and teaching materials used across nurseries and kindergartens. Over time, those picture books traveled far beyond Japan, translated into 50 languages. In the same year, Toppan established Toppan Shoji, a general trading company created by taking over Tokai Paper Industries—soon handling trade across construction materials, electrical appliances, home furnishings, and office products. This was diversification with intent: broaden the company’s reach into adjacent ecosystems where its manufacturing knowledge and customer relationships could compound.

And then came the move that, in hindsight, looks almost absurdly ahead of its time: semiconductors.

In 1961, Toppan entered the photomask business. On paper, it wasn’t a leap. It was an extension of what the company already did to make plates—metal processing, etching, surface control—just applied to a new kind of “printing,” where the substrate wasn’t paper and the output wasn’t an image. It was the template for building chips.

At the time, it may have felt like one more adjacent bet. But it planted the seed for a business that would later put TOPPAN on the global semiconductor map.

Over the decades that followed, Toppan kept widening its portfolio—commercial printing and publications, packaging, interior décor and industrial materials, securities and business forms, and later precision electronic components and data processing. It grew into one of the world’s largest printing companies, but the more important shift was philosophical: the company was learning that “printing” was just the visible output. The durable advantage was the capability stack underneath it—precision process control, reproduction and color technology, expertise with substrates and coatings, and the operational discipline to produce high quality at high volume.

That realization—treat the skills as portable, not the product—became the template for everything that came next.

V. The Semiconductor Pivot: Printing Meets Silicon

At first glance, banknotes and microchips feel like they belong to different universes. One is paper you can fold in your pocket. The other is silicon sealed inside a black package.

But the deeper you go, the more the connection snaps into focus. Both are pattern-transfer problems. Both demand extreme cleanliness and process discipline. Both lean on photochemistry, coatings, and etching. And both punish defects with zero mercy—because a single flaw can mean a counterfeiting vulnerability in one world, or a ruined wafer lot in the other.

That’s why Toppan’s move into semiconductors in 1961 wasn’t as random as it sounds. The company often describes its advantage as a set of core technologies it built through printing: information processing, microfabrication, surface treatment, material forming, and marketing solutions. In the photomask business, the first four mattered immediately. Making plates for secure printing had already forced Toppan to master metal processing techniques like etching, plating, and precision coating. Photomasks simply demanded those same muscles at a much smaller scale.

And Toppan didn’t just participate. It achieved the first domestic production of masks for mesa transistor manufacturing—an early signal that this wasn’t a side project. The precision that helped make securities hard to forge translated into the precision required to define transistor geometries.

As the decades rolled on, the tailwinds only strengthened. With AI, automotive, power electronics, and 5G pushing demand, the global semiconductor market kept expanding—and Toppan’s photomask capabilities moved from “interesting adjacency” to “strategic pillar.”

By 1990, Toppan was ready to take that pillar global. It formed Toppan Printronics U.S.A., a joint venture with Texas Instruments, with Toppan holding an 85% stake. The mission was clear: manufacture semiconductor photomasks for customers in the United States and Europe. This was one of Toppan’s first major semiconductor investments outside Japan—and a concrete step toward building a worldwide manufacturing footprint.

That global footprint would become a defining differentiator. In the 2020s, as governments pushed for more localized and resilient semiconductor supply chains, Toppan stood out as the only photomask manufacturer with production locations spanning the U.S., Europe, Japan, and Asia.

And to push that business even further, Toppan carved out its photomask operations into Toppan Photomask Co., Ltd., bringing in Japan-based private equity firm Integral Corporation as an investment partner. The idea was to strengthen competitiveness and accelerate growth as a more independent entity—while continuing to support the semiconductor industry as the leading player in the merchant photomask market.

In a world where chipmaking is becoming as geopolitical as it is technical, that combination—deep process expertise plus a truly global manufacturing network—turned out to be one of TOPPAN’s most durable advantages.

VI. The Digital Reckoning: 1990s-2000s Transformation

By the time the 1990s arrived, the threat to printing wasn’t a new competitor. It was a new behavior.

Personal computers spread. Email replaced envelopes. Marketing budgets started drifting toward screens. And for a company whose roots ran deep in publishing, the shift wasn’t cyclical—it was structural. Japan’s publishing industry, long a cornerstone of demand for high-volume print, began a secular decline that would stretch on for decades.

The groundwork had been laid earlier. In 1980, a Japanese-language word processor finally came into practical use—late compared to the West, in large part because digitizing a language with so many characters is a fundamentally harder engineering problem. But once that wall cracked, the pace quickened. Through the 1980s, computers and word-processing software proliferated. By the end of the decade, even small businesses could justify a laser printer. The act of “publishing” was being pulled closer and closer to the desk.

For Toppan—and competitors like Dai Nippon—moving into information processing wasn’t a bold new strategy so much as an obvious survival move. The industry itself could see it coming. In 1988, the Paper and Printing Committee published a report that predicted dwindling need for conventional printing and urged printers to change direction. The recommendation was telling: don’t fight the information age. Use your expertise in handling text and images to help build it.

Toppan’s answer wasn’t to retreat and protect the legacy business. It was to expand the definition of what the company could be.

In 1989, it established an industrial materials division designed to turn printing’s “hidden” competencies—coating, vapor deposition, laminating, shaping, and precision processing—into products that didn’t depend on paper demand at all. Out came thermal transfer ribbons, high-performance films, adhesive paper, and hot stamping foil. These weren’t magazines or catalogs. But they were absolutely Toppan: substrate science, surface control, and manufacturing discipline, repackaged for a world that was digitizing.

At the same time, the company pushed outward geographically. As Europe moved toward European Community unification in 1992, Toppan accelerated its presence there. Partnerships in Spain produced decorative furniture boards, while offices in Düsseldorf and London became a platform for serving the continent. In the U.S., it created Toppan Interamerica to establish a clearer North American foothold.

And then there was Toppan Forest.

Opened in 1990, it was a high-tech showroom for interior décor materials, built around a computer system that could store up to 40,000 color images and display them in three-dimensional space. In the moment, it was a sales tool. In hindsight, it reads like an early prototype of something bigger: the idea that Toppan’s future could include digital interfaces, simulated environments, and experiences that live on screens as much as on physical surfaces. Around the same period, the company developed high-definition television printing technology, anticipating that the shift toward HDTV would reshape content creation and the expectations of image quality.

Meanwhile, one of Toppan’s oldest strengths—security—kept finding new international outlets. In 2006, Toppan established Toppan Printing Greece S.A. and secured a contract for Greece’s secure document system. In 2008, it acquired SNP Corporation in Singapore, strengthening its presence in Southeast Asia.

The pattern was becoming unmistakable: as paper demand softened, Toppan didn’t try to freeze time. It kept pulling its core capabilities—materials, precision, imaging, security—into the next medium, the next market, the next substrate.

VII. The 2020s Transformation: Holding Company & Digital Reinvention

By the early 2020s, the forces pressing on TOPPAN weren’t subtle anymore: demand for paper media kept falling as information moved to digital channels, while raw materials got tighter and more expensive. At the same time, new demand was clearly forming—digital solutions shaped by changing lifestyles, and sustainable solutions driven by rising environmental urgency. TOPPAN’s response wasn’t a product launch. It was a structural reset.

In 2023, the company announced what amounted to the biggest corporate reorganization in its history. On October 1, 2023, it shifted to a holding company structure, transferring certain rights and obligations into two new operating companies—TOPPAN Inc. and TOPPAN Digital Inc.—and renaming the parent company TOPPAN Holdings Inc. The logic was straightforward: strengthen Group governance, allocate resources more optimally across businesses, capture synergies that were harder to unlock in the old setup, and make decisions faster.

The name change did the cultural work the org chart couldn’t. Dropping “printing” from the corporate identity wasn’t a marketing tweak—it was a statement. After more than a century, management was signaling that the Group’s trajectory would no longer be defined by the boundaries of traditional printing. The mission was broader: create social value by reinventing the portfolio through digital transformation and sustainable transformation.

That framing shows up in how TOPPAN talks about itself now. Under the concept of “Digital & Sustainable Transformation,” the Group has been pushing DX—using digital technology to transform society, customers, and its own business—and SX, applying business to address social issues and run the company with sustainability as a core operating principle.

The person steering that shift, CEO Hideharu Maro, fit the moment. He joined the company in April 1979 and built a career that blended manufacturing and sales leadership, largely in packaging—one of TOPPAN’s most important growth engines. He became a director in 2009, served as Senior Managing Director and Chief Director of Business Planning from September 2016, and was appointed CEO in June 2019. That mix of technical grounding and commercial responsibility positioned him to push change across the factory floor and the customer relationship at the same time.

And TOPPAN didn’t leave the culture to “catch up later.” In May 2023, it established a new Groupwide philosophy: the Purpose, “Breathing life into culture, with technology and heart,” and four values—Integrity, Passion, Proactivity, and Creativity. It reads like a compass for a company that had spent 120-plus years mastering how to reproduce the world accurately, and was now retooling itself to shape what the world becomes next.

VIII. Key Strategic Moves: Semiconductors, Packaging & Digital

The Photomask Carve-Out and Tekscend IPO

In April 2022, TOPPAN made one of its clearest “modern TOPPAN” moves yet: it took a business born from printing know-how—semiconductor photomasks—and set it up to run faster than the rest of the Group could.

It entered into a share transfer agreement to carve out the photomask business and establish a new company, Toppan Photomask Co., Ltd., bringing in Japan-based private equity firm Integral Corporation as an investment partner. The reason wasn’t that TOPPAN had lost faith in photomasks. It was the opposite. The semiconductor market was expanding quickly, and photomasks were hitting an investment inflection point. To keep up, manufacturers needed to make big bets on R&D and equipment—faster, more flexibly, and with sharper reactions to customer and technology shifts than a traditional conglomerate structure is built for.

Integral acquired a 49.9% stake in Toppan Photomask from Toppan Inc. on April 1, 2022. TOPPAN kept majority control, but gained a partner known for helping businesses professionalize for growth and, importantly, for IPO execution.

Then the business started signaling exactly what the carve-out was designed to enable.

In February 2024, Toppan Photomask announced a joint R&D agreement with IBM focused on EUV photomasks for the 2 nanometer logic node, including High-NA EUV photomask development for next-generation semiconductors. Under the agreement, over a five-year period starting in 1Q 2024, the teams planned to develop capabilities at IBM’s Albany NanoTech Complex in New York and at Toppan Photomask’s Asaka Plant in Niiza, Japan. This is the deep end of chipmaking—work measured in nanometers, where process control is everything.

On November 1, 2024, the company took on a new identity: Tekscend Photomask, a name built from “technology” and “ascend.” The message was straightforward: this wasn’t a legacy carve-out. It was a standalone growth engine meant to keep climbing the technology curve.

And the market treated it that way. Tekscend—carved out of TOPPAN in 2022, with Integral holding 49.9%—completed a $1 billion initial public offering, and its shares rose 19% on their Tokyo Stock Exchange debut.

The $1.8 Billion Sonoco Acquisition

If Tekscend showed TOPPAN getting more focused, the Sonoco deal showed TOPPAN getting bigger—on purpose.

TOPPAN Holdings entered into an agreement with Sonoco Products Company to acquire Sonoco’s Thermoformed & Flexible Packaging (TFP) business for approximately $1.8 billion on a cash-free and debt-free basis, subject to customary adjustments. The strategic logic was clean: Sonoco’s TFP brought a strong sales network, customer base, and solution development capabilities across North and South America, while TOPPAN brought deep technical expertise and global manufacturing capabilities in packaging.

TFP, on a pro forma standalone basis, generated about $1.3 billion in revenue in 2023. The business included roughly 4,500 employees across 22 manufacturing plants, more than 700 patents, and design capability spanning 10 countries.

TOPPAN later closed the acquisition. With it, the Group strengthened its position as one of the world’s largest packaging converters, operating more than 60 manufacturing sites in 12 countries. More importantly, it changed the shape of the packaging business: from something that had historically been anchored in Japan into a truly global platform—especially in North and South America, where TOPPAN had been comparatively underweight.

IoT and Smart Packaging

Then came the next evolution of packaging: make it connected.

In October 2024, TOPPAN Holdings acquired 100% of Selinko SA, a Europe-focused developer of ID authentication platforms, and completed the procedures to make Selinko a wholly owned subsidiary. The stated goal was to strengthen TOPPAN’s services in European IoT and smart packaging and accelerate expansion in the luxury industry—where demand for authentication and traceability is rising fast.

Selinko had been building toward this moment for years. Since launching in 2012, it pioneered IoT solutions using NFC tags, offering platforms that support authenticity verification, gray market detection, ownership management, and consumer engagement. Its solutions have been adopted by more than 30 luxury brands.

In a way, this is TOPPAN’s original business—trust—showing up in a new form factor. A century ago, the company used anti-counterfeiting techniques to protect banknotes and securities. Now, those same instincts and capabilities are being used to help luxury brands fight forgery and create direct, authenticated digital relationships with consumers.

IX. Frontier Technologies: Virtual Humans & Digital Innovation

If photomasks were the “printing meets silicon” plot twist, virtual humans might be the “wait, what company is this again?” moment.

Since 2020, TOPPAN Holdings has been producing high-quality virtual humans built from biometric data captured on its Light Stage. These aren’t just digital characters for show; TOPPAN positions them as user interfaces—human-like front doors to services that can greet, guide, explain, and support.

To push that work forward, the company opened the VIRTUAL HUMAN LAB™ in December 2020. It’s a dedicated research facility for developing applications that use face scanning and other human biometric data. On the surface, that can feel worlds away from ink, paper, and presses. But the throughline is classic TOPPAN: image processing, color management, and high-fidelity reproduction—the same skill set that once made printed images look “true,” and later helped the company deliver precision in display-related manufacturing.

And the timing isn’t random. Labor constraints have become a real macro problem. McKinsey Global Institute has noted that labor markets in advanced economies are among the tightest in two decades. Virtual humans—unrestricted by time zone, location, or scheduling—are pitched as one way to expand service capacity without expanding headcount, with potential use cases across entertainment, hospitality, retail, education, and healthcare.

In March 2025, TOPPAN announced a strategic partnership with Digital Domain, the Hollywood visual effects studio known for its work in major films and virtual production. The two companies had signed a Memorandum of Understanding to collaborate on virtual humans using high-resolution biometric scanning of real individuals. The plan is to take the high-precision data captured on the Light Stage at TOPPAN Holdings’ VIRTUAL HUMAN LAB™ and integrate virtual humans developed from it into Digital Domain’s Momentum Cloud™.

TOPPAN is explicit about the “why” here: helping alleviate labor shortages driven by aging workforces—especially acute in Japan, where the birth rate is low and the population is aging rapidly. By advancing pilot testing and business development that combine each company’s strengths, Digital Domain and TOPPAN said they aim to build a virtual human solution business by the end of fiscal 2025.

X. The Business Today: Three Pillars

If you zoom out far enough, TOPPAN’s business today is the cleanest proof of the pattern we’ve been following all along: the company kept the capability stack, and it kept changing the surfaces those capabilities get applied to.

As of November 14, 2025, TOPPAN Holdings’ stock traded at $27.44, giving it a market capitalization of $7.78 billion. Over the trailing twelve months, the company generated $11.7 billion in revenue.

The biggest segment is still the one that most resembles TOPPAN’s roots. The Information Communication Business accounts for about 53% of revenue. This is where the company’s security-document heritage lives: securities and secure documents, passbooks, cards, and business forms. But it also includes advertising materials, magazine and book printing, and business process outsourcing—work that increasingly blends physical production with information handling.

Next is the Lifestyle and Industrial Business at roughly 32% of revenue. This is packaging and construction materials: decorative sheets, wallpaper, and, now, a dramatically expanded packaging footprint thanks to the Sonoco Thermoformed & Flexible Packaging acquisition. The strategic emphasis here is clear—sustainable packaging solutions that help brand owners meet rising environmental expectations.

Then there’s the Electronics Business, around 15% of revenue, where TOPPAN’s “printing becomes microfabrication” story shows up most directly. This segment includes LCD color filters, TFT LCD components, anti-reflection films, photomasks, and semiconductor packaging products like FC-BGA substrates. It’s the smallest of the three by revenue, but it represents TOPPAN at the frontier of semiconductor manufacturing and is typically the highest-margin part of the portfolio.

Across the Group, TOPPAN employs 57,705 people. And while the company still competes with large global printers and communications firms—Dai Nippon Printing among them—its portfolio has moved well beyond the boundaries of traditional print competition.

Geographically, TOPPAN is still Japan-centric, but the center of gravity is shifting. About 65% of sales come from Japan, with Asia at 17% and other regions—including Europe and the Americas—at 18%. That mix is poised to change as the Sonoco business is fully integrated, materially increasing exposure to North and South America.

Financially, the company’s recent performance shows the same resilience that’s defined its reinventions. In 2024, TOPPAN reported revenue of 1.72 trillion, up from 1.68 trillion the year before, while earnings rose to 89.35 billion—an increase of 20.10%.

XI. Competitive Landscape: The Duopoly and Beyond

For more than a century, Japan’s printing industry has been defined by a familiar pairing: Toppan and Dai Nippon Printing.

Dai Nippon Printing (大日本印刷, Dai Nippon Insatsu), founded in 1876, grew into a peer giant by following a playbook that now feels almost inevitable in hindsight: start with printing, then expand outward into information communications, lifestyle and industrial supplies, and electronics.

Today, Dai Nippon Printing generates about $9.6 billion in trailing twelve-month revenue. It competes with a wide set of companies depending on the product line—names like Toppan Holdings, Transcontinental, Ricoh, and Nissha Printing Company show up in the mix.

But the most important rivalry is still the oldest one. Toppan is the larger of the two, with revenues roughly $2 billion higher. And what’s striking is not just the size—it’s how closely their transformations rhyme. Both companies moved beyond paper into packaging, electronics, and digital services. Both built global operations across Asia, Europe, and the Americas. And both ended up competing in the same “printing, but not really printing anymore” categories: photomasks, display materials, and advanced industrial components.

Nowhere is that overlap clearer than in photomasks, where the competitive set is small and the stakes are enormous. Toppan (through Tekscend), Dai Nippon Printing, and Photronics sit in the top tier. This is a world defined by huge capital requirements, relentless process control, and equipment and know-how that only a handful of companies can sustain—especially as EUV lithography pushes mask making into ever tighter tolerances.

Together, Toppan and DNP account for close to 30% of the global photomask market, supported by vertically integrated operations and deep relationships with major foundries. The market itself was valued at about $6.3 billion in 2024 and is projected to grow to roughly $8.6 billion by 2031. Even at that scale, it remains concentrated: the top three players—Photronics, Toppan, and DNP—hold more than a quarter of global share.

The takeaway is simple: photomasks are not a “winner takes all” market, but they are a “few can even play” market. High capital intensity and steep technical barriers already kept the field tight. EUV adoption at leading-edge nodes has tightened it further, raising the price of admission in tools, materials, and hard-won process expertise.

XII. Bull Case: The Multi-Vector Growth Platform

The bull case for TOPPAN is that it isn’t leaning on a single reinvention. It has multiple, independent growth vectors—each riding a structural trend that’s bigger than any one product cycle.

Semiconductor expansion. The semiconductor market keeps broadening as AI workloads explode, networks get faster, cars turn into rolling computers, and “connected” becomes the default for everything. That pulls demand not just for chips, but for the enabling infrastructure around chips—photomasks and advanced packaging included. Tekscend’s worldwide production footprint matters here, because resilience and proximity are becoming part of the product. And the IBM joint R&D work on EUV photomasks for the 2-nanometer node puts Tekscend in the conversation at the leading edge, where only a handful of suppliers can credibly play.

Sustainable packaging tailwinds. Packaging is being remade by regulation and consumer pressure, and the direction of travel is clear: less waste, more recyclability, better material efficiency. TOPPAN has been investing in formats that fit that future—barrier films, mono-material structures, and recyclable designs—and the Sonoco Thermoformed & Flexible Packaging acquisition gives it scale and reach in the Americas to actually capture that demand, not just talk about it.

Security and authentication demand. Counterfeiting isn’t just a luxury problem anymore. It shows up in pharmaceuticals, electronics components, and anywhere supply chains are global and opaque. This is where TOPPAN’s oldest muscle—security—keeps proving surprisingly modern. A century of secure printing credibility, combined with digital authentication platforms like Selinko’s NFC-based solutions, creates a defensible, end-to-end offering: not just a label or a mark, but a system for proving identity and tracing provenance.

Japanese corporate governance reform. A quieter tailwind is happening at home. Japan’s push for better capital efficiency and stronger shareholder returns has changed the default expectations for large incumbents. TOPPAN’s actions reflect that pressure: for the fiscal year ended March 31, 2024, it paid total annual cash dividends of ¥48 per share, up ¥2.00 year over year, with a total payout ratio of 70.9% when factoring in treasury share purchases. And on May 13, 2024, it announced a plan to buy back up to ¥100.0 billion of treasury shares during the one-year period through May 2025.

Digital transformation enabler. The most important psychological shift is that TOPPAN is no longer positioned as a company threatened by digitization. In many areas, it sells digitization. As enterprises push DX, TOPPAN’s mix of business process outsourcing, data management, and digital content creation lets it be the platform that helps customers modernize—often by combining physical execution with information handling in ways that are hard to replicate.

Zooming out, the competitive structure supports the story. In many of TOPPAN’s businesses, the bar to entry is simply too high—capital requirements, process expertise, certifications, and trust-based customer relationships take years to build. That keeps the field rational in places like photomasks and security, and it rewards scale in packaging and industrial materials.

In the language of durable advantage, TOPPAN’s strengths show up in familiar forms: process power built through decades of manufacturing discipline; scale economies in segments where fixed costs dominate; cornered resources in patents and technical know-how; and a kind of counter-positioning that comes from integrated solutions—because a pure-play photomask firm can’t easily offer packaging authentication, and a packaging pure-play can’t easily bring semiconductor-grade process control to advanced materials.

XIII. Bear Case: Legacy Burdens and Execution Risks

Structural Print Decline. The long arc is still bending away from paper. TOPPAN has diversified aggressively, but its Information Communication segment remains more than half of revenue, and meaningful pieces of that business are still tied to paper-based products. The challenge isn’t whether demand keeps shifting to digital—it’s whether TOPPAN can manage the decline gracefully while continuing to fund the next set of growth engines.

Integration Execution Risk. The Sonoco TFP acquisition is a scale move, but scale cuts both ways. TOPPAN has flagged that the first year was expected to be a drag on profit—around negative JPY3 billion—after integration costs and amortization. That’s not catastrophic; it’s the price of admission. The real risk is execution: aligning organizational cultures, standardizing operating systems, and actually capturing synergies across North and South America and the existing global footprint, without letting the core business lose momentum.

Yen Volatility. As overseas exposure rises—already about 35% of revenue, and likely higher post-Sonoco—currency becomes a bigger swing factor. A stronger yen can compress reported overseas earnings and make Japan-based exports less competitive, adding volatility even if the underlying businesses are performing.

Semiconductor Cyclicality. Photomasks sit inside one of the most structurally attractive industries on earth—and one of the most cyclical. Even if the long-term trajectory is up, there are periods when fabs slow, orders pause, and pricing tightens. Advanced-node masks can carry premium economics, but the business is still vulnerable to sharp volume shifts when the semiconductor cycle turns.

Technology Transition Risk. Staying at the leading edge in photomasks isn’t just about being good—it’s about constantly re-buying your seat at the table. EUV already forced massive investment in equipment, materials, and process control. The next transitions, including High-NA EUV, will demand more. If a player underinvests or slips on capability development, leadership can change hands quickly to competitors willing to spend and iterate faster.

Labor Constraints in Japan. Japan’s demographic reality is a constraint that doesn’t show up neatly on a quarterly chart: an aging workforce and one of the world’s lowest birth rates. TOPPAN can push automation and experiment with tools like virtual humans, but in the near term, labor shortages can still limit flexibility and raise operating friction—especially in businesses that require skilled, high-discipline manufacturing and service execution.

XIV. Key Performance Indicators for Investors

Segment Revenue Mix Evolution. The simplest way to track whether TOPPAN’s reinvention is working is to watch what the company is increasingly paid to do. As electronics, sustainable packaging, and digital solutions grow relative to traditional printing, the strategy is showing up in the numbers. The best place to see this shift is in the company’s quarterly segment disclosures.

Overseas Revenue Percentage. The second tell is geography. For most of its history, TOPPAN was Japan-first by default. As the Group globalizes—especially through packaging—international revenue should become a larger share of the whole. The Sonoco deal is a key catalyst here, and TOPPAN has indicated it should materially lift overseas exposure, including a projected rise to 56% of packaging segment revenues.

Electronics Segment Operating Margin. Finally, watch the profitability of the electronics segment. This is where TOPPAN’s highest-precision manufacturing and semiconductor exposure show up most directly—particularly in photomasks and FC-BGA substrates. Margin trends here are a quick read on two things investors care about most: whether TOPPAN is holding technological advantage, and how the semiconductor cycle is flowing through pricing and demand.

XV. Conclusion: The Art of Corporate Metamorphosis

TOPPAN Holdings’ 125-year arc—from a Meiji-era security printer to a global technology group—isn’t a story of one lucky pivot. It’s a story of a company that learned how to move its advantages from one medium to the next.

It survived two world wars, rode Japan’s postwar rebuilding, and then stared down the slow-motion disruption of its own core market as media shifted from paper to pixels. What kept it relevant wasn’t nostalgia, and it wasn’t denial. It was a repeatable habit: take the hard-earned capability, detach it from the old product, and redeploy it somewhere new.

You can see that pattern in almost every chapter. Security printing’s obsession with precision and trust becomes microfabrication and photomasks. The craft of making images look right in magazines becomes color and image-control expertise that matters in display-related technologies. Packaging shifts from a “nice adjacency” to a global platform—and then evolves again into sustainable materials and connected, authenticated smart packaging. The output changes. The underlying strengths—process control, surface treatment, imaging, materials, and security—keep showing up.

None of that means the road ahead is easy. Print will continue its structural decline. Large acquisitions demand careful integration. Semiconductor transitions like EUV and High-NA EUV require sustained investment and flawless execution. And as the business globalizes, currency volatility becomes a more meaningful swing factor.

But if TOPPAN has earned any benefit of the doubt, it’s that the company knows how to navigate exactly this kind of change. Spinning out Tekscend to let photomasks run faster, buying Sonoco’s packaging business to scale globally, acquiring Selinko to push authentication into IoT, and investing in frontier bets like virtual humans—those are all different moves, but they rhyme with the same instinct: stay flexible, keep redeploying the core, and don’t let the legacy business define the ceiling.

So the real question isn’t whether TOPPAN will ever “stop being a printing company.” It already has, in the ways that matter. The question is whether it can keep converting its accumulated capabilities into new advantages—especially in digital and sustainable domains—faster than its older revenue streams fade.

Its purpose, “Breathing life into culture, with technology and heart,” is the ambition. Whether the next 125 years are as surprising as the first will depend on how well TOPPAN continues to practice the thing it has quietly become world-class at: corporate metamorphosis.

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music