Bandai Namco Holdings: The Empire Built on Dreams, Dots, and Domo Arigato Mr. Roboto

I. Introduction & Episode Roadmap

Picture yourself in Shibuya, Tokyo, in late May 1980. You’re standing in an arcade where the fluorescent lights buzz, cigarette smoke hangs in the air, and every few seconds another machine chirps, blasts, or beeps to life. Space shooters are the main attraction—loud, flashy, aggressive.

But over in the corner, a small crowd has formed around something different.

It’s a simple maze. A bright yellow character. Dots to eat. Four ghosts to avoid. The cabinet’s name reads Puck Man, and what’s striking isn’t just the game—it’s the people playing it. Couples. Women. Curious passersby. Not the usual arcade regulars. They drop in a coin, grab the joystick, and within seconds they get it. Then they try again. Then someone else steps up.

Nobody in that room could have known they were watching the start of a global chain reaction.

That one cabinet—soon renamed Pac-Man—would spread everywhere. Hundreds of thousands of machines. Billions in revenue. A character so ubiquitous that decades later, Guinness World Records would list Pac-Man as the most recognizable video game character in the United States, recognized by 94% of the population.

And the company behind that little yellow circle? That’s where this story really begins.

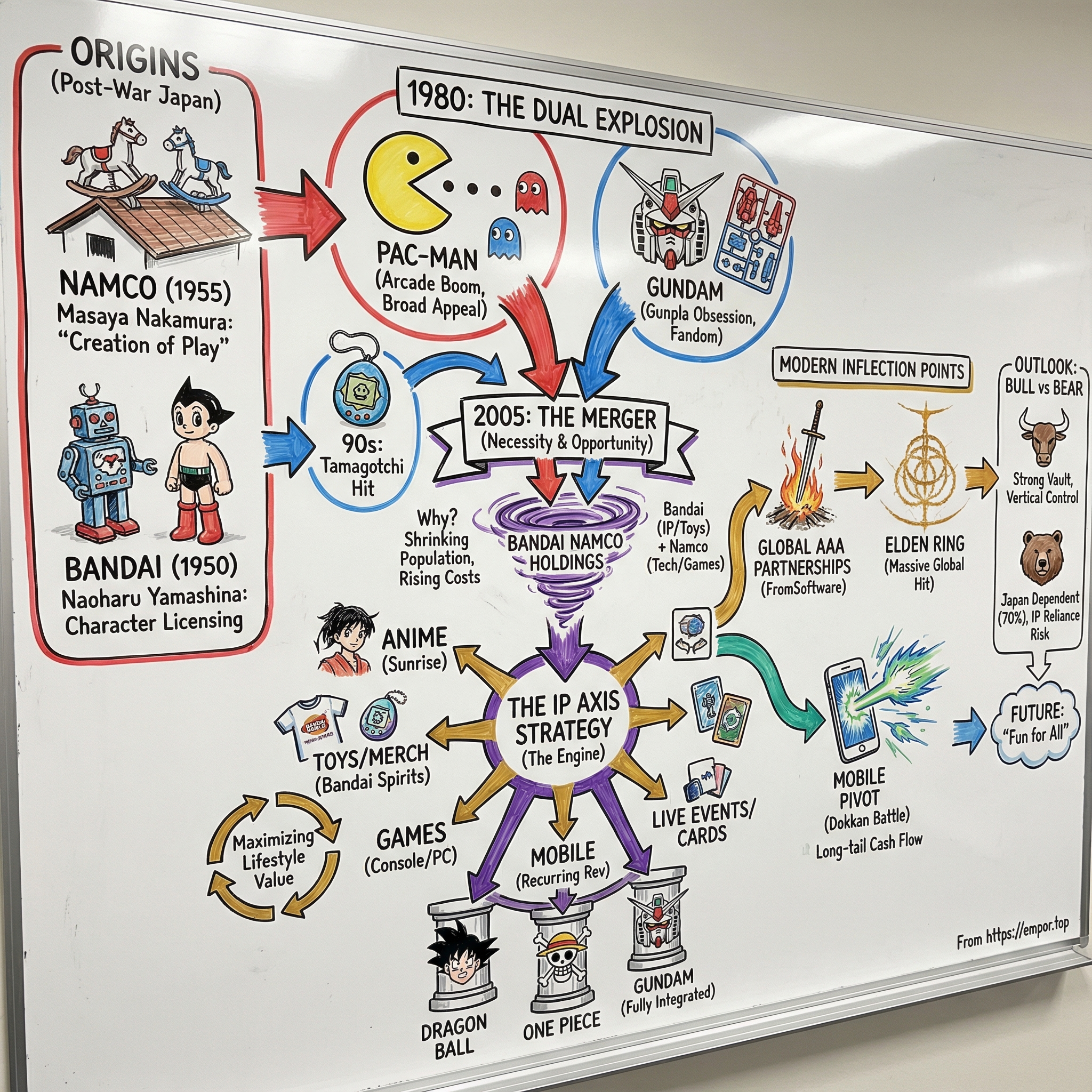

Bandai Namco Holdings Inc. is a Japanese entertainment conglomerate created in 2005, when two very different companies—Namco and Bandai—merged into one. On paper, it’s toys and games, arcades and anime, amusement parks and merchandise. In reality, it’s an intellectual property engine: a business designed to turn characters, worlds, and stories into everything fans can buy, play, watch, collect, or visit.

Which raises the central question of our episode: how did a company that started with two mechanical horses on a department store rooftop become a global entertainment powerhouse? How does one group end up with Pac-Man and Gundam under the same roof—publishing Elden Ring, selling Dragon Ball games, and turning childhood obsessions into recurring revenue?

By the late 2010s, Bandai Namco had become the world’s largest toy company by revenue. By the fiscal year ending March 31, 2025, Bandai Namco Holdings was reporting about 1.24 trillion yen in annual revenue, up strongly year over year. And its crown jewels—Gundam, Dragon Ball, and One Piece—were each generating close to a billion dollars a year in sales. Layer on top of that one of the most important partnerships in modern gaming, with FromSoftware, and you start to see the shape of the empire.

But you can’t understand Bandai Namco by starting at the merger. You have to start with the two origin stories.

Because Namco and Bandai weren’t just different businesses—they were different philosophies of entertainment. Namco was the arcade pioneer, built around a simple idea: “Creation of Play.” Bandai was the licensing and manufacturing machine that learned, earlier than almost anyone, that characters are the product—and the product can be infinite.

Their merger wasn’t just a corporate transaction. It was the combination of two complementary superpowers: one could build the experiences people fell in love with, and the other could scale that love into a universe of products.

Along the way, we’ll hit the big themes that make this story so relevant today: why owning IP matters more than ever, what happens when you try to fuse two distinct corporate cultures, and how entertainment companies survive technological shifts without losing what made them special in the first place.

So let’s begin the way this all began—before Pac-Man, before Gundam, before the merger—on a department store rooftop in post-war Japan.

II. Two Origin Stories: Namco & Bandai

Part A: Masaya Nakamura and the Birth of Namco

Masaya Nakamura was born on December 24, 1925, in Yokohama. In 1948, he graduated from the Yokohama Institute of Technology with a degree in shipbuilding—an eminently practical choice in an island nation. But in the aftermath of World War II, practicality didn’t guarantee a job. Japan’s economy was reshaped overnight, and Nakamura couldn’t find work in his field.

So he looked closer to home. His father ran a shotgun repair business inside a Tokyo department store. When that business found a surprising hit making pop cork guns, Nakamura took the hint: people didn’t just need necessities. They needed small moments of fun.

He scraped together ¥300,000 (about US$12,000 at the time) and made a bet that sounds almost comically simple: two hand-cranked rocking horses. He placed them on the roof garden of a Matsuya department store in Yokohama, the kind of rooftop playground that post-war department stores used to draw families in and keep them there.

It worked.

Those rooftops weren’t just spare real estate. They were one of the few places where leisure could exist in a recovering country. Nakamura understood that if you could create a reason for people to smile—and then scale it—you had a business.

On June 1, 1955, he founded Nakamura Seisakusho Co., Ltd. in Ikegami, Tokyo. Over time, the company name would shorten to Namco—originally an acronym for “Nakamura Amusement Machine Manufacturing Company.” The mission wasn’t high-minded corporate strategy. It was simply making play into a product.

Over the next two decades, Namco expanded from rooftop rides into coin-operated amusement machines, and then into something bigger: video games. The inflection point came in 1974, when Namco acquired Atari’s struggling Japanese division for $300,000—beating out Sega in the process. The purchase gave Namco the rights to distribute Atari’s games in Japan, including Pong and Breakout.

And the Atari relationship quickly became a story all its own. Nakamura later said he’d been approached by someone promising to “suppress” competitors and make him Japan’s largest game developer—an offer he refused, believing it would damage both his company and the industry. Instead, he pushed for more Breakout units. To do it, he flew to London to meet Atari co-founder Nolan Bushnell at the Music Operators Association trade show.

According to Nakamura, Bushnell was too drunk to properly hear him out. Nakamura went home and had his company produce Breakout units without Atari’s permission. Risky? Absolutely. But Breakout became a huge success for Namco, helping it emerge as one of Asia’s key video game manufacturers alongside Sega and Taito.

Now Nakamura wanted more than distribution. He wanted Namco to create. He bought a surplus of NEC PDA-80 microcomputers and ordered his employees to study the hardware—because if you could understand the machine, you could build the game.

Namco’s first in-house title was Gee Bee in 1978, designed by a young employee named Toru Iwatani. A year later came Galaxian, a breakthrough arcade hit and one of the first video games to use RGB color.

But Namco was still only warming up.

Because the next game wouldn’t just be successful. It would change what video games were—and who they were for.

Part B: Naoharu Yamashina and the Birth of Bandai

While Nakamura was turning rooftops into arcades, Naoharu Yamashina was taking a very different route into entertainment: toys.

Bandai was founded on July 5, 1950, by World War II veteran Naoharu Yamashina as Bandai-Ya, spun off from a textile wholesaler. At first, it wasn’t glamorous—Bandai distributed metal toys and rubber swimming rings, then moved into things like metal cars and aircraft models.

Yamashina’s path to that moment was as post-war as it gets. He’d lost an eye in combat. The son of a rice retailer, he’d studied business in high school, and after the war he went to work for a textile wholesaler in Kanazawa run by his wife’s brother. When business lagged, a neighbor mentioned the opportunity in toys. Yamashina persuaded his employer to let him head to Tokyo and try his luck.

Even the name was a mission statement. “Bandai” came from a Japanese reading of the Chinese phrase “bandai fueki” (万代不易), meaning “eternally unchanging” or “things that are eternal.” It was an ambitious idea for a company selling toys—but it hinted at what Yamashina really wanted: not products that sold once, but things that lasted in people’s lives.

In September 1950, Bandai introduced the Rhythm Ball, a beach ball with a bell inside. It had quality problems and didn’t land the way Yamashina hoped. But the important part wasn’t the defect—it was the direction. Bandai wasn’t going to be merely a distributor. It wanted to make, to learn, and to build.

By the 1960s, Bandai was expanding overseas, including opening an office in New York City. The pivotal move came in 1963 with action figures based on the anime Astro Boy. They sold—and in that success was Bandai’s future.

Because Astro Boy wasn’t just a toy line. It was proof that characters were the lever. If you could connect to what people loved on screen, you could extend that love into the real world—into bedrooms, shelves, playgrounds, and eventually entire collections.

This became Bandai’s playbook for decades: find the characters people already cared about—especially in anime and tokusatsu (special effects) TV—secure the rights, and manufacture the physical objects that let fans bring those worlds home.

In May 1980, Yamashina’s son, Makoto Yamashina, became president, while Naoharu became chairman. Makoto moved quickly: he refreshed Bandai’s aging staff with younger employees, revisited the company’s strategy, and shifted Bandai’s commercial approach by selling directly to retailers instead of relying on intermediaries.

Then, in July 1980, Bandai launched something that would define the company for generations: the Gundam Plastic Model, based on the animated series Mobile Suit Gundam. It didn’t just create a product line. It gave birth to Gunpla—an entire category of fandom you could build with your hands.

Gundam would become Bandai’s crown jewel, eventually generating well over a billion dollars annually. But it’s worth holding onto the timing: Bandai’s Gunpla launch happened in July 1980—just weeks after that other cabinet showed up in a Tokyo arcade.

Two products. Two different kinds of obsession. Both destined to shape Japanese entertainment for the next half-century.

And for a long time, these two empires grew in parallel—until the day they finally collided.

III. The Arcade Golden Age: Pac-Man Changes Everything

In the late 1970s, arcades ran on a single emotional note: aggression. Space Invaders. Asteroids. Lasers, explosions, and endless waves of enemies. The spaces themselves reflected it—dark, smoky rooms that felt like a clubhouse for teenage boys.

Inside Namco, a young employee named Toru Iwatani looked at that scene and saw a ceiling.

Iwatani had joined Namco in 1977 after spotting a recruiting ad with a simple promise: “Creation of Play.” He was the kind of hire that made sense for a company like Namco—curious, visual, and self-directed. Born in Tokyo’s Meguro ward on January 25, 1955, he’d spent part of his childhood in Japan’s Tōhoku region after his father took an engineering job with Japan Broadcasting Corporation, then returned to Tokyo for junior high. He never had formal training in programming or graphic design, but he taught himself computers anyway, and he doodled manga in the margins of his textbooks—an influence that would later show up plainly in the characters he designed.

His first expectation at Namco was almost quaint: he thought he’d be building pinball machines. Namco didn’t actually make them, in part because of patent complications. So Iwatani started where many young employees start—repair work, and translating the English instructions that came with imported Atari machines.

Then he got his shot. After working on Gee Bee and its sequels, Iwatani started thinking about what was missing from the arcade floor. Not another shooter, but an entirely different kind of game—something non-violent, something welcoming, something that could pull in women and couples, not just the existing hardcore crowd.

His colleague Shigeichi Ishimura later remembered a moment that captured the motivation: “I think we were on our way home from having a few drinks out in Yokohama, right? Mr. Iwatani saw some girls really enjoying themselves at an arcade and I remember him saying ‘I want to make a game that does that for people.’”

So Iwatani designed with intent. He chose a cute, approachable character. He built the gameplay around food. And he centered the whole thing on eating, because, as he saw it, eating was universal—something anyone could instantly understand without being “a gamer.”

The origin story for the design became legend, and Iwatani backed it up himself: “Oh, it’s the truth all right! I was eating a whole pizza while I was thinking about making a game themed after ‘eating.’ It was then that I came up with Pac-Man’s game design after looking at the pie with a slice taken from it.”

Namco began location testing the game—then called Puck Man—on May 22, 1980, in Shibuya, Tokyo. The results were telling: non-gamers liked it immediately because it was easy to learn, while arcade regulars weren’t particularly impressed. In other words, it was doing exactly what Iwatani wanted—expanding the audience.

Then came one of the most famous naming decisions in video game history. Puck Man became Pac-Man for the U.S. release, largely out of a practical fear: vandals could turn the “P” into an “F.”

When Namco launched Puck Man in Japan, it wasn’t an instant takeover. But once Midway began distributing Pac-Man in North America on October 10, the reaction snowballed into something the industry hadn’t seen before. Over its first year, the game grossed more than $1 billion in quarters. Pac-Man went from “a different kind of arcade game” to the arcade game.

Iwatani built it with a small team—nine people—and the result rewrote the economics of coin-op entertainment. Pac-Man sold in massive numbers, and its footprint kept growing. Guinness World Records later recognized it as the world’s most successful coin-operated game, noting that it had installed 293,822 units within seven years. By the 1980s, it had sold hundreds of thousands of cabinets, overtaking the giants of the era like Space Invaders and Asteroids.

And unlike most hits, Pac-Man didn’t stay inside the arcade. It escaped into culture. Strategy guides hit U.S. bestseller lists. Songs followed. A cartoon television series. Merchandise everywhere. Magazine covers. Pac-Man wasn’t just a game people played—it was something people recognized, talked about, and carried with them.

For Namco, the impact was even bigger than the yellow circle. Pac-Man proved that video games could be designed for a much wider audience—and that if you did, the market itself would expand. Under Masaya Nakamura, Namco rode that wave into a run of defining arcade releases: Galaxian in 1979, Galaga in 1981, and then hit after hit through the decade, including Pac-Man and Dig Dug. By the end of the 1980s, Namco wasn’t just participating in the arcade boom—it was shaping it.

Inside the company, Iwatani’s career rose with the success. But the rewards didn’t, at least not directly: despite creating one of the most valuable games of all time, he didn’t receive a bonus or a salary increase.

Nakamura’s recognition came more formally, later. In 2007, the Japanese government awarded him the Order of the Rising Sun, Gold Rays with Rosette for his contributions to video games. In 2010, he was inducted into the International Video Game Hall of Fame. Over time, his role in building the company that made Pac-Man would earn him a lasting reputation as one of the industry’s foundational figures.

Pac-Man crowned Namco as an arcade powerhouse. But the arcade golden age wouldn’t last forever. The next challenge—for Namco, and for the industry—was what happened when play moved out of the arcade and into the home, and then into the 3D future.

IV. Parallel Paths: Bandai's Character Empire & Namco's Gaming Dynasty (1980s-2000s)

Bandai's Strategic Moves

While Namco was conquering arcades, Bandai was building something even more durable: a character-driven merchandise machine.

Gundam didn’t stay a single TV show for long. Its popularity exploded into a full-blown multimedia franchise—dozens of TV series, films, and OVAs, plus manga, novels, and video games. But Bandai’s real masterstroke was making Gundam something you could own in a uniquely tactile way: plastic model kits. Gunpla became an industry of its own, eventually accounting for about 90 percent of Japan’s character plastic model market.

Bandai kept pressing that advantage. It sponsored and supported television animation, including Pretty Soldier Sailor Moon, and leaned hard into a repeatable formula: generate or license characters, watch what catches fire, then scale manufacturing and marketing fast. The pace was relentless—roughly 60 new characters a year, and a product catalog so aggressive that thousands of items might be introduced and just as quickly pulled, with most of them never leaving Japan.

In the 1990s, that engine started hitting globally. Sailor Moon and Power Rangers broke through in the West and proved Bandai could export fandom, not just toys.

Then came the tiny egg-shaped device that nearly rewrote Bandai’s corporate future.

By the time Tamagotchi mania hit full stride, Bandai already had spinoff items like clothes and video games in motion, and a follow-up concept waiting in the wings: DigiMon, which could connect to another toy for battles. By the end of 1997, about 40 million Tamagotchis had been sold worldwide.

Tamagotchi wasn’t just a hit product. It was Bandai demonstrating that it could create new categories, not merely license existing ones—and it did it by tapping into something primal: the urge to care for, check on, and bond with a “living” thing.

It also detonated a deal that, for a moment, seemed inevitable.

Both Bandai and Namco had, at various points, considered merging with Sega. In 1997, Bandai and Sega even announced plans to combine into a single company: Sega Bandai. But inside Bandai, resistance built quickly. Many employees and midlevel executives felt Bandai’s family-friendly ethic didn’t fit Sega’s top-down corporate culture.

Then Tamagotchi took off worldwide. With Bandai suddenly surging—and internal opposition intensifying—the merger talks collapsed. President Makoto Yamashina took responsibility, publicly apologized, and resigned.

In hindsight, the failure was a gift. Bandai stayed independent, with its IP machine intact, ready for the partnership that would eventually transform it for real.

On a sad note, in October 1997, Bandai founder Naoharu Yamashina passed away at age 79.

Namco's Evolution into 3D

While Bandai was turning characters into an empire, Namco was pushing the technology of play forward—straight into the third dimension.

In 1993, Namco released Ridge Racer in arcades. Built for the Namco System 22 board, it became a milestone: 3D texture-mapped graphics, plus effects like Gouraud shading, that made arcade racers look and feel like the future. The drifting, the speed, the sensation of depth—Ridge Racer wasn’t just a hit. It was a statement that Namco could lead the industry’s next technical leap.

That leadership carried over into the living room at exactly the right time. When Sony launched the PlayStation in Japan on December 3, 1994, Ridge Racer was there at the start. Sony sold 100,000 units on day one, and early coverage credited Ridge Racer as a major reason the new console immediately felt essential—helping PlayStation gain an edge over the Sega Saturn.

Then Namco did it again, this time with fists instead of tires.

Tekken began as an internal test—Namco experimenting with how to animate 3D character models. It evolved into a fighting game, incorporating texture mapping techniques that had helped power Ridge Racer. Along the way, Namco strengthened its bench: in 1994 it acquired developers from longtime rival Sega, which had recently set the pace with Virtua Fighter. Namco’s research managing director had even met with PlayStation architect Ken Kutaragi in 1993 to discuss preliminary PlayStation specs—another sign of how tightly Namco’s arcade ambitions were aligning with the home console future.

Released in 1994 and designed by Seiichi Ishii, a co-creator of Virtua Fighter, Tekken had a deep roster and a consistently smooth framerate—advantages that helped it outrun Sega’s 3D fighting momentum and launch a franchise that would sell millions.

A key reason it translated so well to home was the hardware strategy. Tekken ran on Namco’s System 11 arcade board, which was built on raw PlayStation hardware. That meant the console version could be a near-perfect replica of the arcade experience. Tekken became the first PlayStation game to sell one million copies, and it played a real role in pushing the system into the mainstream.

Through the 1990s, Namco kept shipping hits—Ridge Racer, Tekken, Taiko no Tatsujin—but the broader environment was getting tougher. Japan’s economy struggled, and arcades, once Namco’s natural habitat, began to lose oxygen.

By 2003, Namco was looking for a strategic way through consolidation and proposed a merger with Sega. Instead, those overtures helped set off the chain of negotiations that ended with Sega merging with Sammy.

And that left a new reality: Sega had found its partner, the industry was consolidating, and both Bandai and Namco were staring at the same problem from opposite sides of entertainment.

So they looked around.

And then they looked at each other.

V. The Merger: Creating an Entertainment Juggernaut (2005-2006)

By the mid-2000s, Bandai and Namco were staring at the same set of forces—and none of them were friendly. Entertainment was consolidating fast. Game development was getting more expensive and more complex. And Japan’s consumer market, pressured by declining birth rates, wasn’t getting bigger.

So in 2005, the toy giant and the game publisher decided to do something that would have seemed unthinkable a decade earlier: join forces. In their joint statement, they pointed to Japan’s shrinking population and rapid technological change, and framed the merger as a way to stay competitive—and stay relevant to a new generation.

Structurally, the logic was straightforward: bring Bandai’s characters and merchandising muscle together with Namco’s game development and arcade expertise. Under one roof would sit home console game content, arcade games, and mobile content—one combined entertainment stack instead of two separate companies trying to keep up on their own.

The deal mechanics reflected Bandai as the larger partner. Bandai purchased Namco for about US$1.7 billion. Ownership of the new group split 57% to Bandai and 43% to Namco. The merger was carried out via a share exchange: Bandai shares converted at a 1-to-1.5 ratio into the new company, while Namco shares converted one-for-one.

The alliance became official on September 29, 2005, with the creation of a holding company: Namco Bandai Holdings Inc.

Outside observers saw it less as a bailout and more as a pairing of complementary strengths. Takeshi Tajima, a consultant at BNP Paribas, summed it up: “Basically, this is a positive step for both firms. This isn't a merger where one is rescuing the other. Each will bring strengths to the table and together they can work to address any weak points.”

Those weak points were obvious in mirror image. Bandai had world-class character IP, but relatively limited technology. Namco had game technology and development capability, but far fewer character brands with the kind of merchandising gravity Bandai was built around. Together, they could do what neither could do alone: create the experience and own the characters—and then monetize both across products, platforms, and regions.

Leadership was set to balance the two sides. Kyushiro Takagi, Namco’s Representative Director, became Chairman and Director. Takeo Takasu, Bandai’s President and Director, became President and Representative Director.

And looming over it all was Masaya Nakamura, the founder who’d started Namco with two mechanical horses. He’d stepped down as Namco’s CEO in 2002 and moved into a ceremonial role, and after the merger he retained an honorary position in the video game division, Bandai Namco Entertainment—an elder statesman watching his company merge into something much bigger than the rooftop it began on.

Of course, the paperwork was the easy part. The real work was integration.

Namco’s culture was rooted in engineering excellence and arcade-born game design. Bandai’s was built around licensing, consumer products, and manufacturing at scale. Different rhythms, different incentives, different definitions of what “success” even looked like. Harmonizing management philosophies, creative priorities, and partner relationships would be its own long game.

Under the new holding company, the sprawling universe of subsidiaries on both sides had to be reorganized and slotted into the right parts of the combined group. And the first major step came quickly: on March 31, 2006, Namco merged with Bandai’s video game operations to form Namco Bandai Games.

Immediately, the big questions were on the table. Could they truly fuse Bandai’s character machine with Namco’s gaming technology? Could they navigate entertainment’s shift from physical goods to digital delivery? And could a newly merged Japanese company compete as Western game publishers and studios grew more dominant globally?

The answers would come through a strategy Bandai Namco would eventually describe as its greatest strength.

VI. Post-Merger Consolidation & The IP Axis Strategy (2006-2015)

After the merger, Bandai Namco didn’t linger in the honeymoon phase. The mandate was clear: simplify the sprawl, add capabilities, and build the kind of global footprint that could actually carry its franchises—whether they were born in arcades, on TV, or on toy shelves.

That meant consolidation, and it meant acquisitions.

In September 2006, Namco Bandai Holdings acquired CCP Co., Ltd. from Casio and made it a wholly owned subsidiary. The buying didn’t stop there. Over the years that followed, the group fully acquired developers like Banpresto—folding its video game operations into Namco Bandai Games on April 1, 2008—as well as Namco Tales Studio.

In 2009, the company moved again, acquiring D3 Inc., the parent company of D3 Publisher, on March 18—after first taking a 95% stake.

But the most strategically important move wasn’t about game development. It was about distribution—getting Bandai Namco’s products into more hands, in more countries, with less friction.

In March 2009, Namco Bandai Games Europe announced it would purchase Atari’s stake in Distribution Partners for €37 million and merge it into its own operations, following Atari’s decision to exit the PAL distribution market. Atari Europe’s assets were folded into Namco Bandai, expanding the company’s reach to operations in over 50 countries, supported by 17 dedicated offices.

Internally, they were also reshaping how games got made. In 2012, development operations were spun off into a new company, Namco Bandai Studios—now Bandai Namco Studios—creating a clearer separation between building games and publishing them.

And then came the symbolic moment that made the integration feel final.

In 2015, the entire group began using the Bandai Namco name worldwide, officially retiring the “Namco Bandai” name for good.

It wasn’t just a branding cleanup. It was an admission of what the combined company had learned in practice: the engine was IP. Bandai’s character licensing and consumer products foundation generated steady cash flow, and that stability helped fund the riskier, hit-driven world of video game development. This wasn’t two companies sharing a logo anymore. It was one entertainment company, organized around franchises.

Masaya Nakamura died on January 22, 2017, at age 91. Bandai Namco announced it a week later, out of respect for his family’s privacy.

The founder who took a post-war gamble on two rocking horses didn’t live to see the full flowering of what Bandai Namco would become. But his legacy—this idea that play could be designed, manufactured, and shared at scale—was now fused with Bandai’s own superpower: turning characters into worlds, and worlds into lifelong obsessions.

VII. The IP Axis Strategy: Bandai Namco's Core Philosophy

If there’s one idea that explains how Bandai Namco works, it’s what the company calls its “IP axis strategy.”

The premise is simple: don’t treat a franchise as a single product. Treat it as a worldview—a set of characters, rules, aesthetics, and emotional hooks—and then build multiple businesses around that core. Bandai Namco describes it as maximizing IP value by leveraging those worldviews and delivering the right products and services, in the right regions, at the right times.

In other words: IP is the axis, and everything else spins around it.

Bandai Namco doesn’t just rely on what it already owns, either. It aims to create “unique, experience-based value” while fostering new IP through internal development and outside partnerships. The strategy is meant to scale both ways: deepen the franchises that already work, and keep feeding the machine with new ones.

What does that look like in practice? Take Gundam.

As of 2022, the Gundam franchise was fully owned by Bandai Namco Holdings through Bandai Namco Filmworks (via Sunrise) and its wholly owned subsidiary, Sotsu. And the revenue arc tells you why the company treats this like a flywheel, not a one-off hit: Gundam annual revenue reached ¥54.5 billion by 2006, ¥80.2 billion by 2014, and ¥145.7 billion by 2024.

In the fiscal year ending March 2022, Bandai Namco reported Mobile Suit Gundam earned 101.7 billion yen across the holding group’s subsidiaries—crossing the 100 billion yen mark in a single fiscal year for the first time.

More recently, in the first half of FY25, Mobile Suit Gundam was the group’s best-selling IP with ¥76.5 billion in revenue, up 5% year over year. Dragon Ball followed at ¥75.7 billion, and One Piece at ¥73.2 billion.

Those numbers aren’t just “good performance.” They’re proof the model works: keep the franchise alive with content, then let that content unlock product after product, across multiple categories, without starting from scratch each time.

That’s also why Bandai Namco holds such dominant positions in the markets that best monetize fandom. In fiscal year 2023, Bandai Namco Holdings captured 84% of Japan’s plastic character model market and held a 60% share of Japan’s digital card game market.

The synergy is the point. If Bandai Namco releases a new Gundam anime series, the toys and model kits can land alongside it. Video games extend the universe. Trading card games give fans another way to participate. Live events turn the audience into a community. Each touchpoint makes the others stronger, pulling fans deeper and keeping the IP economically “on-axis” for longer.

To keep that engine running, Bandai and Bandai Spirits handle roughly 530 IPs annually—spanning anime, manga, games, entertainment, and “fancy” IP—developing products and services around them.

And Gundam is only one pillar. Pac-Man, Tekken, Dragon Ball, and One Piece are all deeply embedded in popular culture, and that kind of recognition compounds over time. It drives repeat purchases, creates durable loyalty, and builds brand equity that’s hard for competitors to manufacture.

Bandai Namco has also pushed the IP axis strategy outward—toward global fan connection. In its mid-term plan, the company framed its priorities around connecting with fans through IP, enhancing IP value, and expanding projects worldwide to grow sales outside Japan. One initiative under that umbrella is an “IP Metaverse,” which the publisher said it would invest ¥15 billion (about $130 million) to implement.

For investors, this strategy is both Bandai Namco’s greatest strength and its core vulnerability. When your entire company is built around franchises, your fortunes depend on those franchises staying relevant. If a pillar like Gundam or Dragon Ball ever truly fell out of favor with younger audiences, it would hurt. But the counterweight is that these are multi-generational properties—and Bandai Namco’s whole playbook is designed to refresh them, repackage them, and reintroduce them, again and again, wherever fans are.

VIII. Inflection Point #1: The FromSoftware Partnership & The Souls Revolution

If there’s one relationship that shows how Bandai Namco can spot elite creative talent and scale it globally, it’s the long-running partnership with FromSoftware.

Bandai Namco has occasionally spoken about this relationship, and when it does, it’s a rare window into how a publisher with global reach pairs with a studio that has a very particular, very uncompromising creative voice.

It started small. Back in 2009, Bandai Namco secured the rights to publish Demon’s Souls in Europe—at a time when FromSoftware’s punishing action RPGs were still very much niche. But that early bet turned into something far bigger: a pipeline of games that didn’t just succeed, but helped define modern action RPGs.

The clearest proof is Dark Souls. Over time, the trilogy grew into such a commercial force that it ultimately generated more money than long-running powerhouse IP like Dragon Ball and Naruto—making it Bandai Namco’s most successful game ever.

And then came Elden Ring.

Elden Ring combined FromSoftware’s signature worldbuilding—directed by Hidetaka Miyazaki, the creator behind Dark Souls—with the fantasy storytelling pedigree of George R. R. Martin, author of A Song of Ice and Fire. It wasn’t just another “Souls game.” It was a mainstream cultural event, supercharged by Bandai Namco’s overseas marketing and distribution muscle.

Since launching on February 25, 2022, Elden Ring has shipped over 30 million units. It’s also become one of the most decorated games in recent memory, with more than 300 “Game of the Year” nominations and wins, including at The Game Awards, DICE, and GJA.

And the franchise didn’t stop at the base game. Shadow of the Erdtree, the major DLC expansion released in June 2024, surpassed 10 million units worldwide. Then Nightreign, the standalone co-op survival game set in the Elden Ring universe, crossed 5 million units globally after releasing this May.

For Bandai Namco, this era reset the ceiling on what a single title could do. The company has pointed to mega-hits like Elden Ring and Dragon Ball: Sparking! Zero—together generating more than $3 billion in sales—as direct evidence of its mission: to entertain and connect people through standout content.

But the FromSoftware story also highlights a more complicated truth: even when Bandai Namco helps make a global phenomenon, it doesn’t always keep the keys forever.

Sometime around March 2023, ownership of the Elden Ring trademark transferred to FromSoftware, based on a U.S. Patent and Trademark Office assignment document. The transfer appears to cover the game’s name only. Attorney Richard Hoeg told VGC this wouldn’t necessarily mean a transfer of what most people think of as “the game itself,” though that could have happened separately.

Either way, it raises the strategic question hanging over Bandai Namco’s games business: how durable is its advantage if the very best content depends on partners?

FromSoftware—now majority-owned by Sony and Tencent—has shown it can create games that break out of the traditional hardcore audience and become global entertainment. Whether Bandai Namco can keep that relationship strong, and replicate it with other top-tier developers, may shape its long-term position in AAA gaming.

Because the FromSoftware partnership captures both sides of Bandai Namco’s opportunity and risk: it can amplify great creators with world-class distribution and marketing—but it doesn’t always end up owning the world it helped bring to life.

IX. Inflection Point #2: The Mobile Gaming Pivot & Dragon Ball Z Dokkan Battle

While console gaming grabbed headlines with Elden Ring, a second transformation was happening in parallel—and it was even more reliable: mobile.

Bandai Namco didn’t need a once-every-few-years blockbuster to win on phones. It needed beloved IP, a game built to live for years, and a reason for fans to come back day after day. Dragon Ball Z: Dokkan Battle became the proof case.

After launching in Japan in January 2015, Dokkan Battle rolled out worldwide on iOS and Android on July 16, 2015. It went on to pass 350 million downloads, and over time it crossed the $3 billion mark in worldwide revenue—putting it in the rare air of the highest-grossing mobile games ever.

The spend curve tells you what kind of product this is. After hitting $2 billion in 2019, it added another $1 billion over the next 20 months. And it kept going: in 2024, Dokkan Battle was Bandai’s highest-grossing mobile game, bringing in $271 million in worldwide revenue.

What made it work wasn’t just Dragon Ball’s popularity. It was the combination of a franchise people already loved with free-to-play mechanics designed for longevity: constant updates, collectible incentives, and a calendar of events that trained the audience to show up for the big moments.

Japan has been the center of gravity. It’s the game’s top revenue market by far, generating $1.8 billion to date—about 60% of total player spending.

And like the best live-service games, Dokkan Battle has its own heartbeat. Revenue tends to spike in February and July, tied to anniversary celebrations and special in-game events. July 2021 was one of the strongest months in the game’s history, pulling in $80.5 million in player spending.

This mobile pivot wasn’t limited to Dragon Ball. Bandai Namco began deploying multiple IP across mobile platforms, building a recurring revenue engine that complemented the hit-driven, cyclical console business.

You can see that balance in how the company itself has talked about results. Bandai Namco cited Elden Ring, its Shadow of the Erdtree DLC—with “favorable results” and 5 million units in three days—and Gundam Breaker 4, which it said had a “good start,” as major drivers of video game revenue growth. It also pointed to Dragon Ball: Sparking! ZERO, which launched after the end of Q2 and sold over 3 million units in its first 24 hours—performance the publisher called “outstanding sales.”

For investors, that mix is the whole point. Console games can be huge, but they demand massive upfront investment and live or die on reception. Mobile, when it works, becomes a compounding annuity: predictable revenue powered by live operations, seasonality, and fandom. Put the two together—blockbuster console launches and steady mobile income—and Bandai Namco ends up with something entertainment companies fight for: a business model that can absorb risk without losing momentum.

X. Inflection Point #3: The Gundam Consolidation & Sotsu Acquisition

In 2019, Bandai Namco made one of its most strategically important moves of the entire decade: it went to lock down full control of Gundam.

The company announced it would begin a tender offer to acquire all common stock of Sotsu Co., Ltd.—the longtime Gundam sponsor and rights-holder partner—with the goal of making Sotsu a wholly owned subsidiary. The intent was straightforward: consolidate the Gundam licenses inside the group, so the franchise’s future didn’t depend on an outside intermediary.

The process didn’t go perfectly smoothly. The following month, Chicago-based investment firm RMB Capital pushed back and forced Bandai Namco to raise its tender offer price in a follow-on offer aimed at Sotsu’s general shareholders. But the direction didn’t change. On March 1, 2020, Sotsu became a fully owned Bandai Namco subsidiary.

This wasn’t a random bolt-on acquisition. Sotsu had been intertwined with Gundam from the beginning. It’s a Japanese advertising agency that, starting in 1972, became involved in producing and licensing television programs. Its first produced anime series was Sunrise’s Invincible Super Man Zambot 3, and in 1979 it produced Mobile Suit Gundam. Post-acquisition, that history became internal: Sotsu and Bandai Namco Filmworks—already closely linked—were now corporate siblings under the same roof.

In IP terms, the deal was vertical integration in its purest form. By acquiring the company that helped produce and license Gundam from inception, Bandai Namco reduced licensing friction and gained far more direct creative and commercial control over its most valuable franchise.

The financial impact kept underlining why this mattered. In the first quarter of fiscal year 2026 (April–June 2025), the Gundam franchise generated about ¥65.4 billion (roughly US$443 million) in IP-related revenue—Bandai Namco’s top-earning IP for the quarter—driven by momentum across streaming, model kits, theatrical releases, and experiential tourism initiatives.

And Bandai Namco kept tightening the screws. On October 7, it announced preparations for an organizational restructuring of its anime-related businesses—specifically Bandai Namco Filmworks and Sotsu—to streamline overlapping operations around Gundam and other businesses. The restructure is planned to take effect on April 1, 2026, with the stated goal of accelerating global expansion of the Gundam series.

Zoom out, and the pattern is clear: this is the IP axis strategy expressed as corporate org chart. Remove middlemen. Collapse duplicated teams. Keep the creative and commercial decisions close to the franchise. For Bandai Namco, Gundam isn’t just a hit property—it’s a pillar. And the company is building the cleanest possible machine around it.

XI. Financial Performance & Current Position

By the mid-2020s, Bandai Namco’s numbers were starting to tell the same story its strategy promised: when the IP flywheel is spinning, it’s hard to stop.

In its most recent results, revenue climbed to ¥955.6 billion, up 23.8% year over year, while operating profit jumped 129.0% to ¥179.2 billion. Growth showed up across every segment, but the digital business—games—did the most to pull the totals upward.

The underlying drivers were exactly what you’d expect from an IP-first machine. Gundam plastic models kept selling. Trading card games tied to ONE PIECE and DRAGON BALL stayed hot, not just in Japan but overseas too. On the content side, the IP production business had wins as well: Mobile Suit Gundam SEED FREEDOM became the highest-grossing Gundam film in history, and the new Blue Lock anime series saw strong reception.

With that momentum, Bandai Namco raised its full-year outlook. It revised its forecast to revenue of ¥1.23 trillion, operating profit of ¥180 billion, and net profit of ¥128 billion.

The company’s own first-half presentation put more detail behind that picture. H1 net revenue reached ¥611.3 billion, up 21.8% versus the prior year’s period, and operating profit rose 73.6% to ¥113.6 billion. But the regional split was the more revealing datapoint: Japan accounted for 69.5% of revenue, with the Americas at 10.5%, Europe at 10.4%, and Asia at 9.6%.

In market terms, Bandai Namco is substantial but not gigantic for the scale of its cultural footprint. As of July 24, 2025, Bandai Namco Holdings had a market capitalization of around $21.4 billion. For the twelve months ending March 31, 2025, it reported $8.14 billion in revenue.

That concentration at home—nearly 70% of revenue coming from Japan—cuts both ways. It’s proof of an exceptionally strong domestic base and deep, multi-generational franchises. But it’s also the company’s biggest strategic pressure point. If Bandai Namco wants truly sustainable long-term growth, international markets need to become a larger share of the pie, not just a nice-to-have.

Bandai Namco already operates across Japan, North America, Europe, and Asia, and it’s been clear about where it wants to go next. Japan still dominates in the first half of FY2025, but overseas growth—especially in North America and Europe—has become increasingly important, with international markets accounting for 40% of total sales in 2024.

XII. Bull Case & Bear Case

The Bull Case

IP Portfolio Dominance: Bandai Namco sits on a vault of franchises most entertainment companies would kill for. Gundam, Dragon Ball, One Piece, and Pac-Man aren’t just popular—they’ve proven they can survive format changes, platform shifts, and generational handoffs. And the company’s “IP axis strategy” turns that advantage into an operating system: treat each IP as a world, then expand it across games, toys, anime, cards, events, and merchandise—tailored by region and timing. When it works, every new release becomes marketing for everything else.

Vertical Integration: With Sotsu brought in-house and Sunrise now operating as Bandai Namco Filmworks, the company has tightened its grip on the critical layers of the stack: production, licensing, and distribution. That cuts out intermediaries, reduces friction, and lets Bandai Namco capture more of the economics around its biggest franchises.

Gaming Success: The FromSoftware relationship has been a modern jackpot, and internal pillars like Tekken continue to endure. Dragon Ball games reliably show up on bestseller charts, and mobile titles add a steadier, recurring layer of revenue than the traditional console hit cycle.

Market Position: Bandai Namco’s dominance in “hobby fandom” categories gives it a kind of quiet strength. It holds an 84% share of Japan’s plastic character model market and a 60% share of Japan’s digital card game market. Those aren’t flashy markets, but they tend to be sticky—built on collecting behavior, high engagement, and repeat purchasing.

Diversification: Bandai Namco isn’t a pure-play game publisher that lives and dies by the next release. The toy and hobby businesses can smooth out the bumps when game revenue is lumpy, and the games can reignite demand for physical products when a franchise catches fire. The mix makes the overall machine more resilient.

The Bear Case

Geographic Concentration: The home market is also the risk. With close to 70% of revenue coming from Japan, Bandai Namco is heavily exposed to a country facing long-term demographic decline. International growth can’t just be incremental—it has to become structural.

IP Dependence: The portfolio is broad, but the profit center is concentrated. If a pillar like Gundam or Dragon Ball meaningfully loses relevance with younger audiences, the fallout wouldn’t be contained—it would hit across categories at once.

Gaming Competition: Global AAA gaming is brutal. Western companies with massive budgets and studio scale can dominate mindshare, and development costs keep rising. Even for Bandai Namco, big console bets require heavy investment with no guarantee of a hit.

Partnership Risk: Some of the most important successes come from partnerships rather than wholly owned studios. FromSoftware is the obvious example. The Elden Ring trademark transfer is a reminder that the incentives and ownership structures in these relationships can shift over time.

Anime Production Challenges: The animation side has its own constraints: rising costs and animator shortages put pressure on schedules and margins. Strengthening production capability and capacity isn’t optional if Bandai Namco wants to keep feeding the IP flywheel with new content.

Strategic Analysis Through Porter's Five Forces

Threat of New Entrants: LOW. You can’t speedrun a multi-generational entertainment franchise. The barrier isn’t just capital—it’s cultural time, creative iteration, and decades of audience trust.

Bargaining Power of Suppliers: MODERATE. Elite developers and animators are scarce, and scarcity creates leverage. Bandai Namco’s scale and IP make it a desirable partner, but it still competes for the best talent.

Bargaining Power of Buyers: LOW TO MODERATE. If you’re a committed Gundam builder or a Dragon Ball diehard, there’s no substitute for the real thing. But entertainment as a category competes for discretionary spending, and attention is always up for grabs.

Threat of Substitutes: MODERATE. Fans have endless options—new games, streaming, social platforms, other franchises. The defense is emotional attachment: the deeper the connection to the characters and worlds, the harder it is to replace.

Competitive Rivalry: HIGH in gaming, MODERATE in toys and character merchandise. Games are a knife fight for mindshare. Character merchandise is still competitive, but Bandai Namco’s scale and category leadership soften the pressure.

Hamilton Helmer's 7 Powers Analysis

Scale Economies: MODERATE. There are benefits to scale in development and production, but creative work doesn’t compound like a factory. After a point, bigger can just mean more complicated.

Network Effects: LIMITED. These aren’t platforms in the classic sense; the product doesn’t automatically become more valuable because more people use it—though fandom and community can create softer, indirect effects.

Counter-Positioning: LOW. The “IP axis” model is easy to describe and hard to execute, but it isn’t a secret. Competitors can attempt similar playbooks if they have the franchises and operational discipline.

Switching Costs: MODERATE TO HIGH. Collectors and long-term players build real sunk cost—money, time, progress, and identity. Leaving a Gunpla collection or a years-old mobile account isn’t like switching toothpaste.

Branding: VERY HIGH. Pac-Man, Gundam, Dragon Ball—these are globally legible icons. Bandai Namco’s brand equity is one of its strongest moats.

Cornered Resource: HIGH. Exclusive control of IP like Gundam is a resource competitors can’t realistically replicate, and in many cases can’t buy.

Process Power: MODERATE. Bandai Namco has deep expertise in licensing, merchandising, and franchise management. It’s a real capability—but not one that’s truly unique in entertainment, just unusually well-practiced at scale.

XIII. Key Performance Indicators to Watch

If you want to keep score on whether Bandai Namco’s strategy is working in real time, three metrics tell you more than any press release:

1. IP Revenue Concentration: Watch how much of total revenue comes from the pillars—Gundam, Dragon Ball, and One Piece. When those franchises are humming, they make the whole machine look inevitable. But the higher that share climbs, the more exposed the company becomes if one pillar cools off. The other side of this metric is just as important: whether newer IP starts to show up as meaningful contributors, proving the flywheel can be fed with something other than the legacy giants.

2. International Revenue Percentage: Bandai Namco still makes the bulk of its money in Japan. So the international revenue ratio is the clearest signal of whether it’s actually becoming a global-first company, not just a Japanese champion with overseas hits. Progress toward its stated goal of getting more than a third of revenue from outside Japan would be a strong indicator that the IP axis strategy is translating across cultures and markets, not just at home.

3. Digital Business Operating Margin: Games are the growth engine—and also the volatile part of the portfolio. Digital operating margin is the truth serum here. It shows whether Elden Ring-scale wins are flowing through to durable profitability, or whether the gains are being eaten up by the escalating cost of making and marketing big games in a world where expectations rise every year.

XIV. The Road Ahead

Masaya Nakamura died on January 22, 2017, at age 91. The man who started with two rocking horses and helped build an entertainment empire didn’t live to see Elden Ring sweep the biggest awards in gaming, or Gundam model kits and figures sell out around the world. But his fingerprints are still on the company’s operating system: play as a craft, and joy as a business.

When Pac-Man creator Toru Iwatani is asked why the character has lasted, he doesn’t reach for technology or marketing. He points, instead, to something older: a 17th-century haiku, and the idea that audiences need to recognize themselves in a fictional character.

That’s an unusually poetic explanation for one of the most commercially successful games ever made. But it captures a truth Bandai Namco has been monetizing for decades: the strongest entertainment isn’t built on complexity. It’s built on universality. Eating. Competing. Collecting. Caring. Belonging. Whether it’s a yellow circle chasing dots or a teenager building a giant robot at a desk, the hook is the same. The story feels personal.

Today, Bandai Namco sits at a real inflection point. The company has shown that the IP axis strategy can throw off extraordinary returns when it’s firing on all cylinders. Elden Ring proved what happens when Bandai Namco pairs global distribution and marketing muscle with an elite, uncompromising creative partner. Gundam continues to grow as a multi-decade franchise. Mobile has added a steady, recurring layer of revenue that smooths out the hit-driven console cycle.

But the pressures don’t go away. Japan remains the center of the business, which means demographic headwinds matter more here than they would for a truly global peer. AAA games keep getting more expensive, and the risk curve keeps rising with them. The most important partnerships can shift, or end. And the hardest question in entertainment never fully resolves: can yesterday’s beloved worlds stay essential to tomorrow’s audience?

Bandai Namco’s stated purpose is “Fun for All into the Future.” It’s a modern echo of Nakamura’s original “Creation of Play,” and it fits the company it has become: less a toy maker or a game publisher than a franchise engine designed to keep fans connected across decades, platforms, and formats.

The company that began on a department store rooftop now holds one of the most valuable entertainment portfolios on Earth. From Pac-Man to Elden Ring. From Tamagotchi to Gundam. From arcades to smartphones to streaming.

The next chapter isn’t written yet. But if the last seventy years are any indication, Bandai Namco will keep finding new ways to turn imagination into something you can play, watch, collect—and carry with you.

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music