Olympus Corporation: From Microscopes to Medical Dominance—A Century of Reinvention

I. Introduction: The Mountain of the Gods

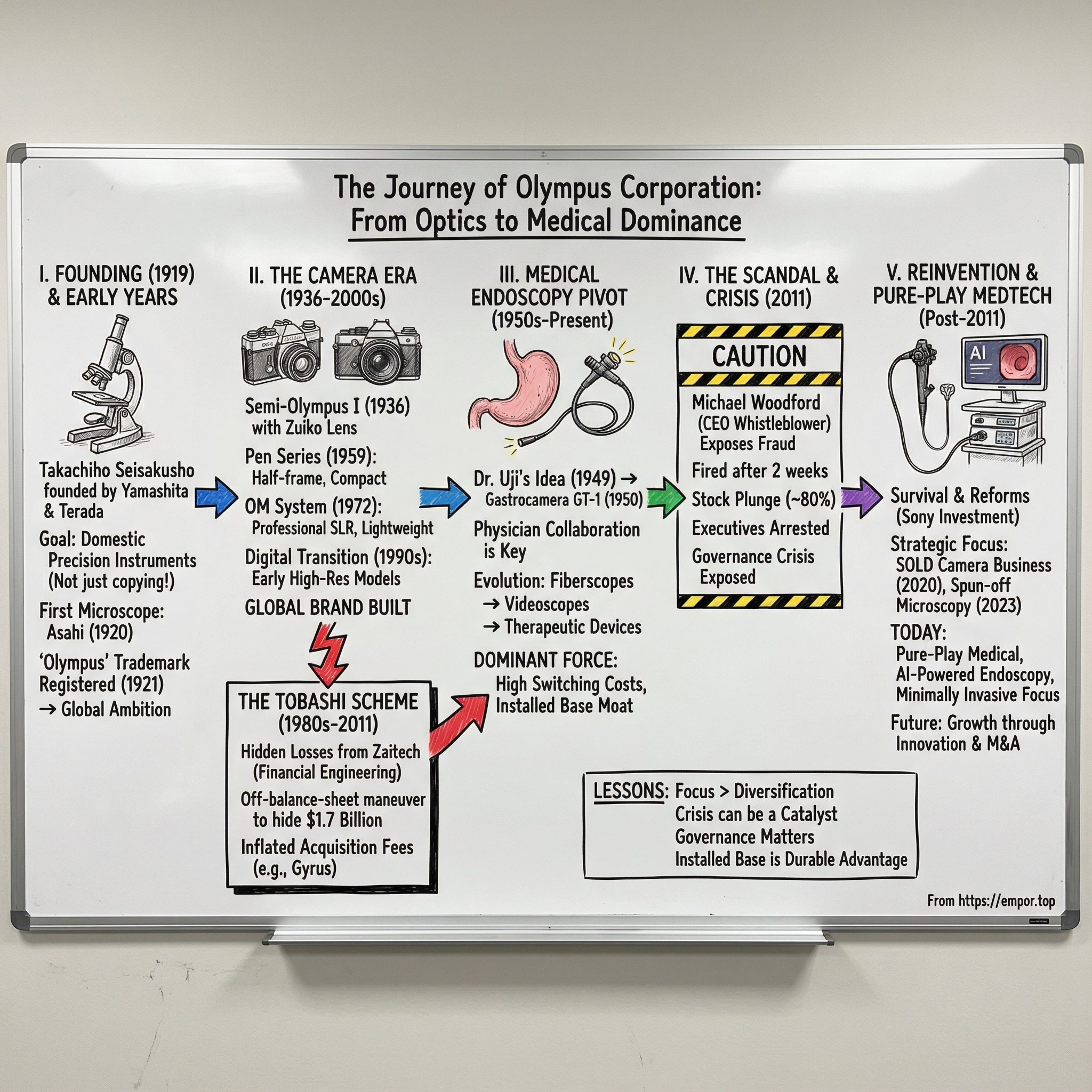

In ancient Greek mythology, Mount Olympus was the seat of the gods: remote, powerful, untouchable. When a Japanese optics company registered “Olympus” as a trademark in 1921, it wasn’t being subtle about its aspirations. The name was meant to signal a single idea: build instruments so good they could stand with the world’s best.

A century later, Olympus does sit on a kind of mountaintop—just not the one most people think of. In endoscopy, it’s one of the dominant forces in a global industry where a small handful of companies—Olympus, Karl Storz, Boston Scientific, FUJIFILM, and Stryker—collectively account for roughly half the market. And that market is expected to keep expanding dramatically over the coming decade.

Getting there, though, wasn’t a smooth climb. How does a company that started in a Tokyo workshop making microscopes and thermometers become the defining name in gastrointestinal endoscopy? And how does it survive one of the largest accounting scandals in Japanese corporate history—one that erased roughly 80% of its share price, sent executives to court, and forced the rest of the world to stare hard at Japanese corporate governance?

This is the story of Olympus: a century-long compounding of optical expertise, a series of reinventions, one near-death crisis, and then a decisive bet on medical technology—so decisive it eventually meant walking away from the very camera business that made Olympus famous. We’ll trace the arc from the 1919 founding, through the 2011 scandal that nearly destroyed the company, to the end of an 84-year camera era, and into today’s pure-play medical Olympus—including a more recent CEO crisis that reopened uncomfortable questions about foreign leadership at the top of a traditional Japanese corporation.

Running through it all are a few big themes: Japanese corporate culture versus Western governance expectations; the strategic logic of focus over diversification; the way crises can become catalysts; and the deeper question underneath every great business story—what actually creates durable advantage when the product is complex, regulated, and literally used inside the human body.

II. Founding & Early Years: Optics for a Modernizing Japan (1919–1950s)

The story begins in October 1919, in a Japan racing to modernize after World War I. On October 12, Takeshi Yamashita founded a small company in Tokyo called Takachiho Seisakusho. The mission was straightforward and ambitious: stop relying on imported scientific instruments—especially microscopes—and build them domestically.

Yamashita was an unusual person to lead that charge. He wasn’t an engineer. He was an attorney, freshly graduated from Tokyo Imperial University’s law school in 1915. After a year of military service, he joined a trading company, Tokiwa Shokai, and proved himself in a completely different arena: sugar trading. He made Tokiwa Shokai a lot of money—and in a move that sounds almost unbelievable today, the firm rewarded him by helping finance his own venture.

He didn’t do it alone. Yamashita partnered with Shintaro Terada, a friend from his law-school days who brought the critical ingredient: technical credibility. Terada had already done something rare in Japan at the time—built microscopes using industrial techniques in the 1910s. One of his microscopes was exhibited at the Taisho Expo in 1914 and won a bronze prize. Terada could build the instruments; Yamashita could build the company.

The timing mattered. In early twentieth-century Japan, microscopes and other precision scientific instruments were still largely imported from Europe, especially Germany. And the Japanese government wanted that to change. Domestic production of precision instruments wasn’t just good business—it was national industrial policy. Yamashita saw both the patriotic angle and the market opportunity.

But he also set a standard that would echo through Olympus’s later decades. He pushed his engineers with a simple idea: copying imported products wouldn’t be enough. If the company was going to matter, it needed to create something original.

They moved fast. In June 1920—barely six months after the company was founded—Takachiho introduced the Asahi, its first domestically manufactured microscope. Even the name “Takachiho” carried mythic ambition: in Japanese mythology, it’s associated with Takamagahara, the realm where eight million gods and goddesses reside, high on the peak of Mt. Takachiho.

Then came a brand decision that would outgrow the company itself. In February 1921, “Olympus” was registered as a trademark. The logic was elegant: Mt. Olympus, like Mt. Takachiho, was considered a home of gods and goddesses. But Olympus also had something Takachiho didn’t—instant recognition outside Japan. If this company ever wanted to sell to the world, it needed a name the world could say.

The early years were a grind. Yamashita later documented the struggle in a booklet titled “Kusetsu 13-nen” (Thirteen Years of Unswerving Efforts). Takachiho relentlessly built up its technical capability and its sales channels, trying to make microscopes that could genuinely compete with the European imports.

Eventually, it did. With the development of the Showa GK microscope, the company broke into the high-magnification oil-immersion segment—an area that had been dominated by foreign products. It was a breakthrough not just in engineering, but in legitimacy. Takachiho could now play in the highest tier, and government policies favoring Japanese-made products helped accelerate its growth.

As the business evolved, so did its identity. In 1942, Takachiho Seisakusho became Takachiho Optical Co., Ltd., reflecting how central optical products had become. In 1949, the company changed its name again—to Olympus Optical Co., Ltd.—a deliberate move to elevate the corporate image around the stronger, more globally resonant brand. (Much later, in 2003, it would become Olympus Corporation, unifying the corporate name with the brand.)

The 1942 shift also reflected the world Olympus was operating in. Wartime demand made optical instruments strategically important, and the company’s lenses and microscopes translated into military applications like targeting and observation equipment. When the war ended, Olympus had to rebuild itself for civilian life.

And that reset set the stage for what came next: a fateful meeting in 1949 that would quietly steer Olympus toward the business that would one day define it—medicine.

III. The Camera Era: Building a Global Brand (1936–2000s)

Before we follow Olympus into the hospital, we have to follow it into people’s hands. The parallel story—the one that made Olympus a global consumer brand—was cameras.

In 1936, Olympus released its first camera, the Semi-Olympus I. It came fitted with the company’s first Zuiko-branded lens. Zuiko—often translated as “Divine Light”—would go on to become a revered name among photographers. And it wasn’t a marketing invention. Olympus’s decades of microscope work had trained the company to obsess over glass, coatings, tolerances, and image clarity. A camera lens was just a different canvas for the same craft.

After World War II, Japan’s consumer electronics industry exploded, and cameras became one of the country’s defining exports. Olympus rose alongside the era’s other optical giants—Canon and Nikon in particular—as a serious contender with a distinctive point of view: make high-performance gear that didn’t feel like a brick.

That philosophy crystallized in 1959 with the launch of the Pen series. The Pen used a half-frame format—72 photos on a standard 35mm roll—which let Olympus build a camera that was genuinely small and easy to carry at a time when most serious photography meant serious bulk. The Pen team was led by Yoshihisa Maitani, who would become a legend inside the industry: equal parts engineer and designer, with an instinct for what users actually wanted.

Maitani and his team didn’t stop at half-frame. They later created the OM system: a full-frame professional 35mm SLR platform meant to compete head-to-head with Nikon’s and Canon’s bestsellers. The OM line pushed a new trend toward compact professional bodies and lenses, without compromising capability. It also introduced features that felt ahead of their time, like off-the-film (OTF) metering and OTF flash automation.

The OM-1, introduced in 1972, became the statement piece. It was nearly 40 percent lighter than competing professional SLRs, while matching—or in some cases exceeding—them in performance. This wasn’t Olympus shaving weight for bragging rights. It was Olympus redefining what “professional” could look like.

By the 1960s, Olympus was turning from a Japanese champion into a global one. It established Olympus Europe in 1964, and Olympus Corporation of America in 1968. For millions of consumers, cameras were Olympus. They were the public face of the company.

Then came digital. The transition created a new battlefield—one that rewarded speed, conviction, and capital. One of the executives pushing Olympus into that future was Tsuyoshi Kikukawa, who later became president. Kikukawa is credited with championing the company’s strategy in digital photography and fighting internally for a serious commitment to high-resolution products. In 1996, Olympus released an 810,000-pixel mass-market digital camera at a time when many rivals were still selling devices with less than half that resolution. The following year, Olympus shipped a 1.41 million pixel model.

It’s an important detail for what comes later. Kikukawa wasn’t a one-note villain in the Olympus story. He also helped drive real innovation and sharp strategic bets. Olympus’s history—like most real corporate histories—doesn’t divide cleanly into heroes and failures.

And while Olympus was winning mindshare with photographers and building a global brand around compact excellence, another business was quietly compounding in the background—one that would eventually matter far more than cameras ever could: medical endoscopy.

IV. The Rise of Medical Endoscopy: Olympus's Real Moat

The origin story of Olympus’s medical business has the kind of hinge-point drama you usually only get in myth: one visit, one problem, and a company’s trajectory bends for the next seventy years.

In 1949, a young doctor—29-year-old Dr. Tatsuro Uji of Tokyo University Hospital in Koishikawa—came to Olympus with a radical idea. The concept of looking inside the human body with instruments wasn’t new. But in Japan at the time, the need was urgent. Stomach cancer was the country’s leading cause of death, and diagnosing it often meant invasive surgery just to see the stomach lining.

Uji’s proposal was deceptively simple: build a miniature camera that could go down a patient’s throat and take photographs of the stomach from the inside. If doctors could see earlier, they could diagnose earlier. The problem was that the device he wanted didn’t exist.

For Olympus, it was a brutal engineering challenge wrapped in a medical one. A camera small enough to pass through the esophagus. Tough enough to survive the stomach. Able to produce usable images in near-total darkness. The team had no playbook. They had to invent their own path, grinding through trial after trial—many of them failures—until, in 1950, they finally produced a working prototype.

Even then, the first clinical use wasn’t a triumphant “of course it worked” moment. It was terrifying. Dr. Uji later described what it felt like standing in front of the first patient: “My hands trembled in front of Patient 1 and it was hard to convey the necessary level of self-confidence. Subconsciously, I prayed for our success.”

In 1950, Olympus’s first gastrocamera—the GT-1—was ready, and it made its debut publicly at a meeting of the Japan Surgical Association on November 3. Newspapers picked up the story. A Japanese optics company had built something that could see inside the stomach without cutting the patient open.

But invention is one thing. Making it work in the real world is another. The early gastrocameras were fragile, and in clinical practice they proved prone to faults and malfunctions. Doctors couldn’t reliably get diagnostic-quality photographs. Olympus was soon swamped with returns and repair requests. Without believers on the clinical side—doctors willing to keep pushing through the rough early versions—the product might have disappeared almost as soon as it arrived.

Instead, those believers organized. A group of physicians formed the Gastrocamera Research Group Meeting, a predecessor to today’s Japan Gastroenterological Endoscopy Society. Olympus, in turn, received a steady stream of feedback from the people actually using the device, and the product improved iteration by iteration.

That loop—engineers building, physicians testing, both sides feeding the next version—became Olympus’s enduring operating system in medical. The company wasn’t just shipping hardware. It was embedding itself into a clinical community.

Commercial distribution began in 1952 under the name “Gastrocamera.” And then the pace of progress accelerated. In the 1960s came fiberscopes, which allowed doctors to view in real time instead of relying on photographs developed later. In the 1980s came video endoscopes, turning endoscopy into something a whole medical team could see together on a monitor, not just the physician peering through an eyepiece.

Olympus was among the pioneers of videoscopes in the late 1980s. By putting a video camera inside the scope and converting images into electronic signals displayed on a TV monitor, procedures became more collaborative—and more humane for the operator. Better light sources and video imaging improved the field of view, reduced the physical strain of bending over an eyepiece, and improved diagnostic accuracy. It was a leap not just in image quality, but in workflow.

And then endoscopy crossed the line from seeing to doing.

Alongside the scopes themselves, Olympus developed therapeutic devices that expanded what endoscopes could accomplish. Early systems were primarily diagnostic: physicians could look, but treatment still meant surgery. Modern endoscopy became a platform. Through the scope, physicians could remove polyps, cauterize bleeding vessels, deploy stents, and take biopsies. Advanced systems enabled earlier detection and earlier treatment, changing outcomes for cancers and other diseases.

Over time, Olympus kept pushing the technology forward—integrating CCDs into videoscopes and advancing capabilities like Narrow Band Imaging (NBI)—each step making endoscopy more powerful and more central to modern care.

By the early 2000s, Olympus’s lead had hardened into something more than a product advantage. The switching costs were immense. Hospitals had invested heavily in systems and accessories. Physicians had trained for years on Olympus equipment and built their procedural instincts around it. Major procurement cycles stretched out for years. This wasn’t gear you swapped out on a whim; it was installed infrastructure that shaped clinical workflows.

Olympus had found its real moat.

And, as it would soon learn, that success would also become tangled up with the company’s greatest crisis.

V. The Tobashi Scheme: Seeds of a Scandal (1980s–2011)

To understand the Olympus scandal, you have to go back to Japan’s late-1980s bubble—and what happened when it popped.

In those years, asset prices in Japan didn’t just rise; they detached from reality. Real estate and equities became collateral for ever more borrowing, and corporate treasuries began behaving like hedge funds. Across Corporate Japan, companies leaned on investment gains to paper over pressure in their underlying businesses, especially as a strong yen squeezed exporters.

Olympus was no exception. Toshiro Shimoyama, who served as president from 1984 to 1993, said it plainly in 1986, speaking to Nikkei: “When the main business is struggling, we need to earn through zaitech.” Zaitech—financial engineering—meant using things like derivatives and other financial instruments to generate profits that the core business wasn’t producing.

While the bubble inflated, this could look like clever management. When it burst around 1990, it became an existential problem. Losses that had been sitting quietly in portfolios suddenly became impossible to ignore. For many companies, admitting them would have meant a public confession of failure, a collapsing stock price, and potentially a funding crisis.

That’s the environment in which Olympus turned to tobashi.

At a high level, tobashi is a loss-hiding scheme: investments that have gone bad are shifted out of sight so the company’s financial statements can pretend the losses don’t exist. The word tobashi translates roughly to “flying away,” which is exactly the point—the losses “fly away” from the balance sheet through a web of transactions, often involving other parties and, at times, entities that exist mostly on paper.

For years, schemes like this lived in a gray zone. They weren’t fully outlawed in Japan until 2001, in the post-Enron era and after the collapse of Yamaichi Securities. Before that, tobashi had been a known, if deeply questionable, tool used by firms trying to survive the wreckage of the 1990s.

Olympus’s version relied on offshore structures, including companies in the Cayman Islands, and it used acquisitions as a mechanism to make the losses disappear “properly.” The company paid exorbitant management and acquisition fees to buy entities that could absorb or repackage those bad investments.

The machinery was complex, but the motive was simple: Olympus had piled up major losses from failed financial bets. Disclosing them would have been devastating. So executives built a labyrinth designed to move those losses away from Olympus’s reported results.

This maneuver, coordinated by finance director Hisashi Mori and internal auditor Hideo Yamada, allowed Olympus to treat the problem as an off-balance-sheet commitment rather than a hit to earnings. The plan, as laid out, effectively turned unrealized investment losses into intangible assets—goodwill—that could then be written down gradually over time instead of being recognized all at once.

But tobashi schemes don’t run forever without an endgame. Eventually, the hidden losses have to be converted into something that can sit in plain sight on the balance sheet without raising alarms. At Olympus, that “something” was M&A.

In 2008, Olympus made what amounted to a capstone transaction: the acquisition of Gyrus, a British medical equipment manufacturer. Olympus paid $1.9 billion for Gyrus—and, remarkably, nearly $700 million more in consultancy fees tied to the deal. Those fees were rolled into goodwill.

That number alone should have stopped the room. Normal M&A advisory fees tend to be in the low single digits. Here, the fees were more than a third of the purchase price. The natural question was unavoidable: who was getting paid, and why?

When auditors began digging, the story started to wobble. KPMG determined that goodwill recorded between 2008 and 2009 was overvalued, and Olympus’s net income fell sharply as the issue came to light. As KPMG’s scrutiny intensified, Olympus switched auditors to Ernst & Young in 2009.

By this point, the board—led by Tsuyoshi Kikukawa—was near the end of an operation that had spanned nearly two decades. Olympus had been hiding up to $2 billion in losses dating back to the early-1990s market crash.

It had survived across presidencies, across business cycles, across auditors. And as The Wall Street Journal later put it, it became one of the biggest and longest-running loss-hiding arrangements in Japanese corporate history.

Then, in 2011, someone reached the top who didn’t instinctively accept “this is how things are done”—and he started asking the wrong questions in the right places.

VI. Michael Woodford: The Whistleblower CEO

Michael Woodford’s rise inside Olympus was, by Japanese corporate standards, almost unheard of. He joined the company in 1981 and spent the next three decades grinding his way up through the European organization. He started at the UK subsidiary, Olympus KeyMed, as a surgical salesman, then moved through sales leadership roles before becoming managing director in 1990—at just 29.

From there, his reputation only grew. In 2004, Woodford joined the main board of Olympus Medical Systems Corporation and was appointed executive managing director of Olympus Medical Systems Europe. He pushed through a sweeping change program that, over the next three years, doubled operating profit. He wasn’t an outsider brought in to “shake things up.” He was homegrown Olympus—just not Japanese.

So when he was promoted to president and chief operating officer in April 2011, and then elevated again to CEO in October 2011 as the company’s first non-Japanese chief executive, it looked like a genuine meritocratic moment. Still, the appointment raised eyebrows. A gaijin at the top of a Japanese corporate giant, and one who didn’t speak Japanese fluently? Could he really run the place?

Then, almost immediately, Woodford ran into something he couldn’t unsee.

As president, he began noticing a pattern of large, quietly executed transactions—especially payments routed through the Cayman Islands, including a transfer to an “adviser” for around $700 million. Around the same time, an obscure Japanese financial magazine, FACTA, published allegations about undisclosed payments tied to Olympus acquisitions. The pieces started snapping together, and Woodford’s suspicion hardened into a conviction: something was deeply wrong.

Woodford did what many CEOs say they’d do, but very few actually do. He pressed. He demanded answers from the board. And because he believed an internal review would never uncover the truth, he brought in PricewaterhouseCoopers to independently assess what he was seeing. He also copied his final two letters to senior Ernst & Young figures in Japan, Europe, and the United States, as well as the firm’s global chairman and CEO—making it much harder for the issue to be quietly buried.

PwC’s report was damning. It highlighted that in the 2008 acquisition of Gyrus, Olympus had paid a “success fee”—an intermediary’s fee for closing the deal—of $687 million to two small entities: Axes America LLC in the United States and Axam Investments Ltd in the Cayman Islands.

Woodford confronted Chairman Tsuyoshi Kikukawa directly. But instead of coming clean, the board brushed him off. The more Woodford pushed, the more isolated he became. And then the hammer dropped.

On October 14, 2011—just two weeks after becoming CEO—Woodford was fired unanimously by the board.

Kikukawa called an emergency board meeting, arrived late, threw out the circulated agenda, and asked directors to consider removing Woodford. Woodford wasn’t allowed to speak or vote. The motion passed unanimously. He kept a seat on the board, but the message was unmistakable. That same day, Kikukawa emailed staff saying the split was due to differences in management style.

Woodford didn’t treat it like an ordinary corporate dismissal. He left Japan immediately and flew back to England, fearing for his safety. Japanese newspaper Sankei reported that as much as US$1.5 billion in acquisition-related advisory payments could be linked to the yakuza. Whether or not those fears were fully substantiated, Woodford believed the risk was real—and acted accordingly.

And then he did the most extraordinary thing of all: he went public.

Woodford became perhaps the first CEO of a global multinational to blow the whistle on his own company. He had been president for six months. He had been chief executive for two weeks. And by taking the story to the press, he forced Olympus’s decades-long loss-hiding scheme into the open—what The Wall Street Journal later described as “one of the biggest and longest-running loss-hiding arrangements in Japanese corporate history.”

By 2012, the Olympus scandal had become a defining corporate crisis in Japan. Woodford received multiple major awards, including the Financial Times “Boldness in Business” Award. In the legal aftermath, six Olympus executives were sentenced to prison.

Woodford later published a book, Exposure: Inside the Olympus Scandal, detailing what happened from his vantage point inside the executive suite. After settling with Olympus for defamation and wrongful dismissal, he turned himself into a global advocate on corporate governance, whistleblower protections, and related public-interest issues, alongside philanthropic work.

But for Olympus, the story was only beginning. Because once the secret was out, the company faced a brutal question: could it survive the truth?

VII. The Aftermath: Scandal, Recovery, and Restructuring (2011–2019)

The market’s verdict was immediate and brutal. Within five months of the scandal breaking, Olympus’s stock was down to roughly 16% of its prior peak. The story was now bigger than one company: arrests at the top, a share price collapse of around 80%, the threat of getting kicked off the Tokyo Stock Exchange, and a global spotlight on how Japanese corporate governance could allow something like this to run for decades.

As investigators pulled on the thread, the allegations ballooned into a sweeping corruption scandal—centered on the concealment of more than 117.7 billion yen (about $1.5 billion) in investment losses, plus a trail of questionable fees and payments reaching back to the late 1980s. There were also suspicions that some payments had flowed to criminal organizations, adding another layer of gravity to what had already become a corporate nightmare.

Then came the existential moment: the Tokyo Stock Exchange put Olympus on watch for potential delisting. For any public company, that’s close to a death sentence—liquidity evaporates, counterparties panic, and the business starts to seize up. Olympus managed to survive it. The TSE ultimately removed the company from the watch list for automatic ejection from the exchange.

The formal penalty, though, was strikingly small. Olympus was not delisted and paid a fine of about US$130,000—an outcome that drew sharp criticism and reinforced the perception that regulators were too lenient on corporate wrongdoing.

Olympus also needed something more basic than reputational repair: it needed stability. One of the most important lifelines came from Sony. In 2012–13, Sony bought an 11.5% stake in Olympus for 50 billion yen, providing capital at a moment when confidence was collapsing and signaling that a major Japanese corporation still believed Olympus’s core business—medical—was real and valuable.

That investment wasn’t just passive. It helped underpin a joint medical venture announced in 2013, aimed at developing high-definition surgical endoscopes and microscopes—squarely in the center of Olympus’s most strategic franchise.

Years later, Sony exited. Reuters reported that Sony sold its stake—valued around $760 million—ending the capital alliance that began during the crisis.

Inside Olympus, the post-scandal cleanup wasn’t optional; it was survival. Governance reforms followed, with particular attention on the Audit Committee. Olympus restructured it to include four members, three of whom Comgest considered independent, including the chair—an important step, even if diversity remained limited, as all members were Japanese.

And the consequences didn’t neatly end with the headlines. Executives faced criminal prosecutions and prison sentences. Civil cases pursued directors for damages. Olympus’s scandal became a long-running legal and governance reckoning—one that permanently changed the company’s oversight structures and turned Olympus into an international case study in what happens when the incentives to hide the truth outweigh the mechanisms designed to surface it.

VIII. The Strategic Pivot: Selling the Camera Business (2020)

In June 2020, Olympus made an announcement that landed like a thunderclap in the photography world: after 84 years, it was getting out of cameras.

The backdrop wasn’t mysterious. Smartphones had eaten the point-and-shoot category, and the remaining dedicated-camera market had gotten smaller and more punishing every year. Olympus had tried to adapt—restructuring manufacturing, tightening its cost base, and leaning into higher-value interchangeable-lens products. But it still couldn’t turn the Imaging division into a consistently profitable business. Up through the fiscal year ending in March 2020, the unit posted operating losses for three consecutive years.

So Olympus decided to do what many iconic Japanese electronics companies had eventually been forced to do: carve the business out, sell it, and move on. The buyer was Japan Industrial Partners (JIP), a Japanese private equity firm, with the deal expected to be finalized by September 30, 2020.

JIP had a playbook for this kind of transition. It was the same firm that took the VAIO computer brand off Sony’s hands in 2014—another famous name, squeezed by a shrinking market, handed to a buyer that could restructure away from the glare of public markets.

The structure was precise. Olympus signed a definitive agreement under which it would first transfer its Imaging business into a newly established, wholly owned subsidiary—what it called the “New Imaging Company”—via an absorption-type split. Then, on January 1, 2021, Olympus would transfer 95% of the shares of that New Imaging Company to OJ Holdings, a special purpose company established by JIP.

The business would operate as OM Digital Solutions, preserving the iconic OM name while cleanly separating it from Olympus. The transfer included all R&D and manufacturing facilities dedicated to the Imaging business. The heads of sales and marketing, R&D, and design would move to OM Digital Solutions’ new headquarters in Hachioji, Tokyo. Production of new products would continue in Dong Nai province, Vietnam.

For long-time Olympus camera users, it felt like the end of something personal. But viewed through the lens of strategy, it was hard to argue with. Cameras had become a capital-hungry, low-margin fight. Medical, by contrast, was where Olympus had its deepest moat, its strongest economics, and the franchise that already generated the bulk of operating profit. If Olympus was going to rebuild post-scandal and compound for the next decade, it needed focus—and focus meant stopping the internal subsidy of a legacy business.

And the camera sale wasn’t a one-off. The divestiture of the camera business in 2020, followed by the spin-off of the microscopy division in 2023, marked a clear direction: Olympus was concentrating its future on medical and life science.

A company that spent a century as a broad optics empire was choosing, deliberately, to become something narrower—and stronger: a medical technology pure-play built around endoscopy.

IX. The Pure-Play Medical Company (2020–Present)

Today’s Olympus looks nothing like the company of even a decade ago. The cameras are gone. The scientific microscopy division has been spun off as Evident Corporation. What remains is a company that has made a clean, deliberate choice: concentrate on medical technology.

That focus shows up most clearly in the product that Olympus now positions as its flagship. Olympus announced the market launch of its next-generation EVIS X1 endoscopy system in the United States, where it was displayed and demonstrated at the American College of Gastroenterology annual meeting. “Olympus is thrilled to bring our most advanced endoscopy system to GI practitioners in the U.S.,” said Richard Reynolds, president of the Medical Systems Group for Olympus America, Inc.

EVIS X1 is Olympus’s most advanced endoscopy system. It was first released in Europe and certain regions in Asia in April 2020, followed by Japan in July 2020 and the U.S. in October 2023, and it later received clearance in China.

The point isn’t just that the screens got sharper. Olympus has also been engineering the experience for the people who have to use these systems all day, procedure after procedure. The ErgoGrip control section is 10% lighter than Olympus’s previous generation, designed to improve comfort and handling. EVIS X1 also includes a suite of image-enhancement tools: Texture and Color Enhancement Imaging technology to increase the visibility of lesions and polyps; Red Dichromatic Imaging technology to enhance the visibility of deep blood vessels and bleeding points; and Brightness Adjustment Imaging with Maintenance of Contrast technology designed to correct brightness levels in darker areas of the image. Narrow Band Imaging technology continues to be featured in the EVIS X1 endoscopy system.

Alongside new systems, Olympus has kept widening the moat with approvals and portfolio expansion. The company received FDA 510(k) clearance for its EZ1500 series endoscopes, which feature Extended Depth of Field technology aimed at enhancing visualization and diagnostic precision. And in January 2024, Olympus acquired Taewoong Medical Co., Ltd. in Korea, expanding its GI Endo Therapy portfolio. It’s a familiar pattern for Olympus: lead with the core platform, then keep filling in the surrounding ecosystem.

The next frontier is software. In September 2024, Olympus received U.S. FDA 510(k) approval for CADDIE, its cloud-based computer-aided detection device designed to help gastroenterologists detect colorectal polyps during colonoscopy procedures.

But becoming a pure-play doesn’t mean the ride gets smooth. Olympus also signaled that the new era would require a leaner machine. In late 2025, the company announced a major restructuring as part of a broader strategy that includes a global organizational transformation to align structure and resources with strategic priorities. Olympus said it expected a net reduction of roughly 2,000 positions across its global workforce—about 7% of its 29,297 headcount—and projected approximately 24 billion yen in run-rate savings. The goal, according to the company, was to simplify organizational layers and expand managerial spans of control.

Financially, Olympus set ambitious targets: 5% year-over-year revenue growth by fiscal year 2029 and more than 10% earnings per share compound annual growth. The company also said it expected continued improvement in free cash flow and planned to deploy capital dynamically across innovation, dividends, share buybacks, and strategic M&A.

X. Another CEO Crisis: The Kaufmann Resignation (2024)

Just when it seemed Olympus had finally turned the page on its governance era, the company found itself in another CEO crisis—this time centered on the foreign executive it had only recently elevated to the top job.

In October 2024, Olympus said its chief executive, Stefan Kaufmann, had resigned at the request of the board following an internal investigation into allegations that he had brought illegal drugs into Japan.

Kaufmann—a German national who was 56 at the time—wasn’t a parachuted-in outsider. He had been with Olympus for two decades. He joined Olympus Europa, the company’s regional headquarters for Europe and the Middle East, in 2003. In 2019, he moved to Tokyo as chief administrative officer. In April 2023, he became CEO. And then, about a year and a half later, he was out.

Olympus didn’t mince words in its statement: “Based on the results of the investigation, the Board of Directors unanimously determined that Mr. Stefan Kaufmann likely engaged in behaviors that were inconsistent with our global code of conduct, our core values, and our corporate culture.” Kaufmann complied with the board’s request to resign.

Kyodo News later reported that Kaufmann pleaded guilty at a December court hearing in Tokyo to buying illegal drugs.

Inevitably, the episode landed with extra weight because it rhymed with Olympus’s most infamous leadership rupture. This was the second time the company had removed a foreign-born CEO. In 2011, it fired Michael Woodford just weeks after making the British executive chief executive—triggering the public unraveling of the accounting scandal.

Two non-Japanese CEOs. Two high-profile exits under a cloud. Coincidence—or a reminder of how hard it can be to graft global leadership norms onto a deeply traditional Japanese corporate structure?

The resignation also created immediate practical questions about succession. Olympus said Yasuo Takeuchi—representative executive officer, executive chair, and ESG officer—planned to step down at the end of March 2026, concluding more than four decades at the company. Takeuchi had served as president and CEO from 2019 and led Olympus’s transformation into a pure-play medtech company. He stepped aside as CEO in 2023 as part of a transition plan, but returned to the corner office in an interim capacity in October 2024 after Kaufmann’s resignation.

To find the next CEO, Olympus said the board’s nominating committee would run the process and had formed an advisory search committee to identify and recommend candidates. The committee includes management and independent board members with experience spanning medtech, executive hiring, and corporate governance. Olympus also said it hired an executive recruitment firm to evaluate both internal and external candidates.

XI. Playbook: Business & Strategic Lessons

The Olympus story isn’t just a saga of invention, scandal, and reinvention. It’s also a surprisingly clean strategic case study—one that keeps pointing back to a handful of fundamentals that matter in almost every industry.

The Power of Focus: Olympus’s biggest burst of value creation didn’t come from building an empire. It came from narrowing it. The camera business was iconic—84 years of heritage, a globally recognized brand, and real engineering excellence. But it had become value-destructive. Selling it was painful, especially for customers and employees who loved it. Strategically, though, it freed Olympus to put its capital, talent, and attention into the one place it had a durable edge.

Installed Base Economics: Olympus’s endoscopy dominance isn’t just about having the best scope. It’s about what happens after the scope arrives. Hospitals that standardize on a platform build their workflows, purchasing patterns, and training around it. Doctors develop muscle memory on specific controls, specific imaging, specific accessories. Switching isn’t only expensive; it’s disruptive. That installed base—relationships, training, and institutional habit—acts like a moat that competitors can’t simply out-innovate in a single product cycle.

Governance Matters, Eventually: Olympus ran a tobashi scheme for roughly two decades while looking, from the outside, like a normal public company: auditors, board meetings, all the right boxes checked. And yet the fraud kept going. The lesson is uncomfortable: governance structures without true independence and accountability can turn into theater. When the scandal finally broke, reforms weren’t optional. More independent oversight, reworked audit functions, and greater transparency became prerequisites for survival.

Cultural Complexity: The Woodford episode made the cultural tension impossible to ignore. Woodford pushed in a way many Western CEOs are taught to push—demand answers, escalate when stonewalled, bring in outside investigators. That collided with Japanese norms that prize consensus, hierarchy, and saving face. His firing was indefensible in light of what he’d uncovered, but it was also culturally predictable inside that system. Then, years later, the Kaufmann resignation—completely different facts, same headline dynamic—reopened the question of whether foreign CEOs can truly thrive at the top of traditional Japanese corporations.

Crisis as Catalyst: The 2011 scandal nearly killed Olympus. But it also forced the company to do what successful incumbents often avoid until it’s too late: change. Without the shock of near-death, would Olympus really have embraced painful governance reform? Would it have let go of cameras? The crisis didn’t just expose weakness—it created the permission structure for reinvention.

The Long Game: Olympus’s “overnight success” in medical took a century. The capabilities that started with microscopes in the 1920s, expanded through cameras in the 1930s, and hardened through gastrocameras in the 1950s compounded into something incredibly hard to replicate: deep, practical mastery of precision optics and miniaturization. That accumulated know-how—more than any single patent—became the foundation of medical dominance.

XII. Framework Analysis: Competitive Position and Strategic Powers

Porter's Five Forces Analysis

Threat of New Entrants: LOW

If you’re a would-be challenger looking at Olympus, the first problem is simply building the thing. Endoscopy systems sit at the intersection of precision optics, miniaturized electronics, biocompatible materials, and extremely demanding manufacturing. Then comes everything around the device: servicing it, maintaining it, and training clinicians to use it safely and effectively.

On top of that, regulation is a moat of its own. Getting FDA clearance means rigorous quality systems and extensive testing. And even if a newcomer clears those hurdles, there’s the human reality: physicians trained for years on Olympus equipment don’t casually switch. Hospitals, meanwhile, tend to standardize on what’s already integrated into their infrastructure. The installed base reinforces itself.

Supplier Power: LOW-MODERATE

Olympus has an advantage many companies would love to have: it can make a lot of its most critical optical components itself. A century in optics shows up here as vertical integration—designing and manufacturing key lenses and optical systems in-house.

That said, Olympus still depends on specialty materials and global electronics supply chains. Some suppliers have leverage, but generally there are alternatives, and many electronic components come from competitive markets.

Buyer Power: MODERATE

Hospitals and group purchasing organizations have real negotiating power, especially when they’re buying big-ticket capital equipment. But in endoscopy, purchasing decisions aren’t purely financial. Physician preference matters—a lot. Doctors tend to have strong opinions about what they trust, what they’re efficient on, and what they believe delivers the best outcomes. Procurement teams can’t ignore that without paying for it in adoption, workflow friction, and clinical dissatisfaction.

Threat of Substitutes: LOW-MODERATE

There are substitutes, but they’re uneven. Capsule endoscopy is the headline-grabber: a swallowable camera enabled by compact imaging, wireless transmission, and sensor systems for control. It can be a real alternative in some diagnostic use cases.

But once endoscopy shifts from looking to doing, the substitutes thin out. Therapeutic procedures—removing polyps, cauterizing bleeding, deploying stents—still require traditional flexible scopes. And while CT and MRI can sometimes replace diagnostic endoscopy, they can’t intervene.

Competitive Rivalry: MODERATE

Olympus, Karl Storz, Boston Scientific, FUJIFILM, and Stryker make up the top tier, together representing nearly half of the global market. That kind of structure usually produces disciplined competition rather than a race to the bottom. The companies overlap, but they don’t all attack the market the same way; each has distinct strengths and focus areas.

Hamilton's 7 Powers Analysis

Scale Economies: STRONG

Endoscopy is a scale game. R&D for next-generation systems is expensive, and Olympus can amortize that cost across global volume. Scale also improves manufacturing efficiency and makes a worldwide service network more economical as density increases.

Network Effects: MODERATE

This isn’t a social network, but the flywheel is real. As more physicians train on Olympus systems, teaching hospitals lean toward Olympus for training. That produces more Olympus-trained physicians, which reinforces hospital preference and standardization. The effect is indirect, but it compounds.

Counter-Positioning: STRONG

Olympus’s divestitures—walking away from cameras and later spinning off microscopy—weren’t just portfolio cleanup. They were positioning. As a pure-play medtech company focused on endoscopy and related therapeutic tools, Olympus signals commitment in a way diversified competitors can’t easily match. When Olympus says it’s all-in on endoscopy innovation, there are no side quests to undermine the message.

Switching Costs: VERY STRONG

Once a hospital commits to an endoscopy platform, it’s not just buying hardware—it’s buying a way of working. Capital cycles are long. Retraining physicians is costly and disruptive. Procedure rooms, workflows, and accessories are built around specific systems, and consumables can be proprietary. In medical devices, switching costs can be strong; in endoscopy, they’re among the strongest.

Branding: STRONG

Olympus’s brand isn’t built on a logo; it’s built on trust. The company’s reputation has been reinforced by continued advances in imaging and endoscopy technologies, including tools like Narrow Band Imaging that clinicians associate with better visibility and better decision-making. With a comprehensive range of endoscopic tools and a long track record of innovation, Olympus has become the default choice in much of gastroenterology.

Key Performance Indicators

For investors tracking Olympus’s ongoing performance, three metrics deserve special attention:

-

Endoscopy System Installed Base Growth: The more hospitals that standardize on Olympus platforms, the more durable the future stream of revenue from accessories, consumables, and service. Installed base is compounding.

-

Adjusted Operating Margin in Medical Segments: A pure-play medical Olympus should expand margins over time. The company has set growth targets through fiscal year 2029 and has also guided to more than 10% compound annual growth in earnings per share. The key signal is whether margins improve as focus increases.

-

Geographic Mix—Particularly China Performance: Olympus has faced headwinds including supply chain disruptions, a difficult business environment in China, and regional budget cuts. China has been both a growth driver and a volatility source, and results there can swing overall performance meaningfully.

XIII. Conclusion: The Mountain Endures

From a Tokyo workshop making microscopes in 1919 to global dominance in gastrointestinal endoscopy a century later, Olympus has shown a rare talent: the ability to reinvent without losing its core. The path was anything but smooth. It ran through world wars, Japan’s boom-and-bust decades, a corporate scandal that nearly ended the company, and then a decision that felt unthinkable to many customers—walking away from the camera business that made Olympus a household name.

What exists today is almost unrecognizable from the original Takachiho Seisakusho, yet it’s still the same organism underneath. The standard Takeshi Yamashita set—build “something truly original,” not mere imitation—didn’t disappear. It simply kept migrating to the next frontier. Microscopes became cameras. Cameras became gastrocameras. Gastrocameras became video endoscopy systems, now edging into AI-assisted detection during procedures.

And Olympus is betting that the next leap looks like a connected, minimally invasive platform: endoscopy enhanced by AI, robotics, and digital systems that link devices, data, and workflows. The company has said it has the world’s largest installed base of endoscopy systems and intends to redefine what “standard of care” means in endoscopy-based treatment.

If there’s one thing the Olympus story makes impossible to ignore, it’s governance. Olympus proved that even a sophisticated public company—with auditors, committees, and the outward rituals of oversight—can hide massive fraud for decades. The cultural dynamics that helped it happen—consensus over confrontation, face-saving over transparency, loyalty over accountability—aren’t uniquely Japanese. They’re human, and they show up anywhere incentives reward keeping problems quiet.

The Woodford affair captured that reality in the starkest possible way. Woodford “won” in the narrow sense: the scheme was exposed and perpetrators were punished. But the cost was personal and extreme. He was pushed out of the company he’d served for thirty years, fled Japan fearing for his safety, and later described months of pressure that at times threatened his health and his family life.

Then, years later, Olympus removed another foreign-born CEO. Stefan Kaufmann’s resignation involved entirely different circumstances, but it echoed uncomfortably: two non-Japanese CEOs, two dramatic exits. Whether that points to deeper dysfunction or is simply coincidence is still debated. Either way, it’s a reminder that leadership transitions—especially in global companies balancing local culture with international expectations—rarely go according to plan.

Strategically, Olympus has made its wager plain. It has exited the side quests—cameras, scientific instruments, dictaphones—and committed to one proposition: that its dominance in endoscopy-enabled care is both durable and expandable. If it’s right, the company’s best era may still be ahead. If rivals find a way through the moat—through new technology, superior training ecosystems, or aggressive pricing—there’s no diversified backstop anymore. Pure-play focus cuts both ways.

That’s why the next chapter is so important. Olympus unveiled the OLYSENSE Platform with the CADDIE AI-driven polyp detection module at Digestive Disease Week. The cloud-enabled system flags suspected lesions in real time, with the promise of making detection more consistent across different operators and settings. AI in endoscopy is the next frontier—and also the next competitive battleground. Olympus’s installed base and physician relationships should help. But technology curves can move fast, and leadership can change hands quickly in moments of disruption.

The name “Olympus” evokes the mountain where Greek gods dwelled: eternal, unassailable, above the mess of ordinary life. The real Olympus has been more mortal—capable of spectacular innovation and equally spectacular failure. Yet the throughline is endurance. Through war and scandal, through shifts in technology and painful corporate shedding, Olympus has made it past a hundred years.

Whether it stays on that mountain for the next hundred will be decided in places that don’t look like mythology at all: in R&D labs designing next-generation scopes, in boardrooms setting the rules leaders must live by, in hospital purchasing committees choosing platforms, and in procedure rooms where clinicians rely on these instruments to find disease earlier and treat it with less trauma. The story isn’t finished. But the chapters so far offer a clear set of lessons about corporate longevity, strategic focus, and the constant tension between innovation and governance.

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music