Shimadzu Corporation: 150 Years of Science in Service of Humanity

I. Introduction: The Hidden Champion of Science

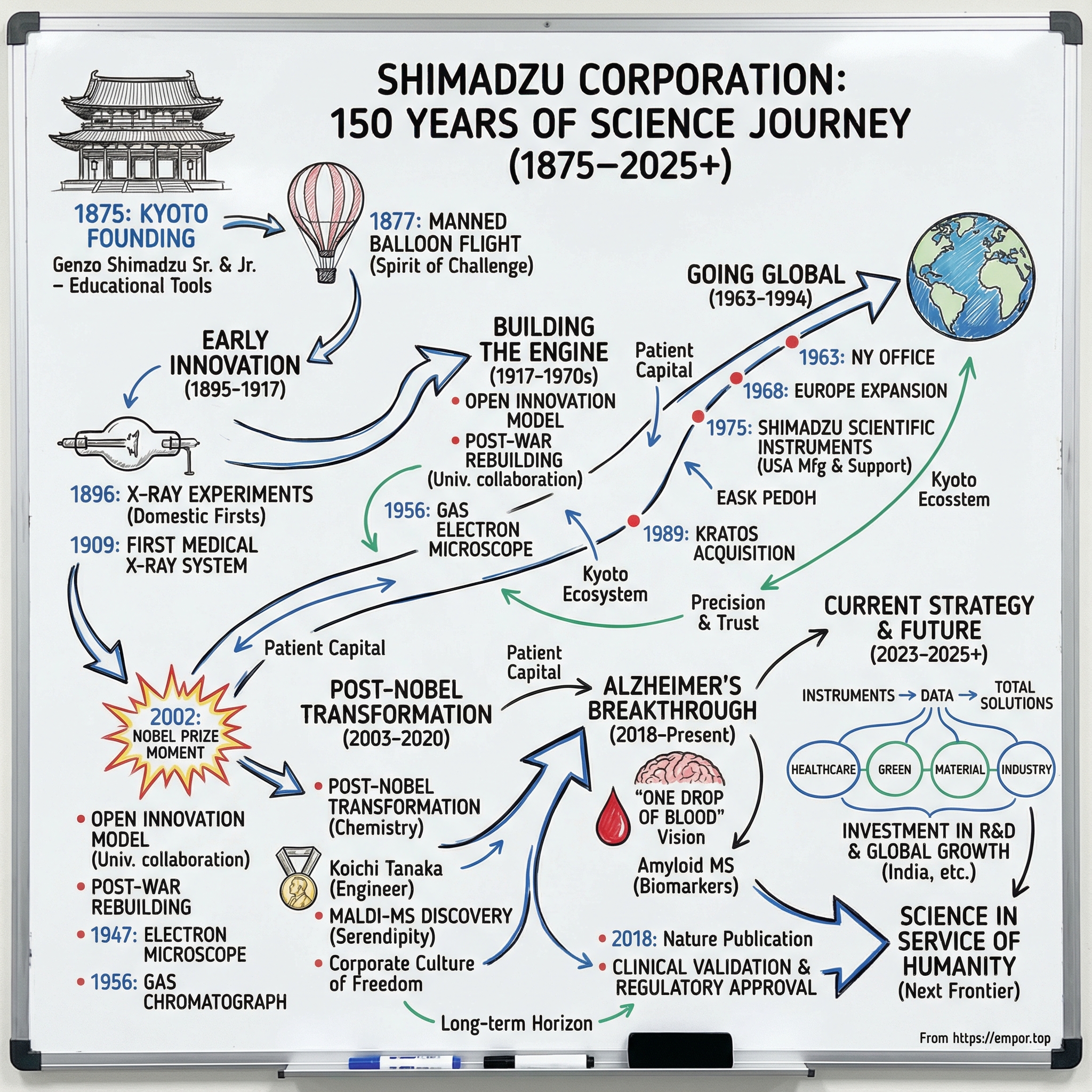

Picture this: a 43-year-old engineer in Kyoto, largely unknown outside his niche, gets a phone call that doesn’t just change his career. It changes his company’s story. It’s October 9, 2002, and Koichi Tanaka has just been told he’s won the Nobel Prize in Chemistry. He became Japan’s second-youngest Nobel laureate at the time—and uniquely, a chemistry winner with only a bachelor’s degree. Inside Shimadzu, he wasn’t an executive or a celebrity scientist. He was, as one account put it, still near the bottom of the promotion ladder.

That single moment captures what’s so distinctive about Shimadzu. This is a company that quietly nurtured Nobel-caliber work inside a corporate lab, led by someone who never went to grad school. Which immediately raises the more interesting question: how does a business that began in 1875 making physics teaching tools for Japanese classrooms end up producing a Nobel laureate—and building technology that could help detect Alzheimer’s disease from a single drop of blood?

Shimadzu was founded in Kyoto in 1875, and it marked its 150th anniversary on March 31, 2025. The longevity is impressive, but what matters more is what it implies: a corporate culture willing to invest in scientific progress on timelines that don’t fit neat quarterly cycles—and to treat long research arcs as core to the business, not side projects.

Today, Shimadzu is a Japanese public company headquartered in Kyoto, manufacturing precision instruments, measuring instruments, and medical equipment. It operates across four business segments: Analytical & Measuring Instruments (its crown jewel), Medical Systems, Industrial Machinery, and Aircraft Equipment. In fiscal year 2023, Analytical & Measuring Instruments led the portfolio, reaching record sales of JPY338.3 billion, up 7% year over year.

But the real reason Shimadzu belongs in a business-history canon is that it’s something the West doesn’t produce as often anymore: a “hidden champion” in B2B scientific instruments. In global life science instrumentation, a small group of firms—Thermo Fisher, Agilent, Danaher, Waters, and Shimadzu—collectively account for roughly 30–35% of the market.

These aren’t consumer brands. They don’t win mindshare with billboards or Super Bowl ads. And yet they’re foundational. When a pharma team is characterizing a new molecule, when a city is checking drinking water for contaminants, when a lab is validating a diagnostic—there’s a good chance the work is being done on equipment from one of these companies.

That’s the terrain we’re going to explore: how the Meiji-era industrial awakening created the conditions for Japanese scientific entrepreneurship; how Shimadzu practiced “open innovation” long before it had a name; and what it really takes to commercialize basic research when the payoff horizon is measured in decades, not quarters.

So let’s start where all great origin stories start—with a blacksmith, a balloon, and a stubborn conviction that Japan could become a world leader in science.

II. Founding Story: The Meiji Restoration and Japan's Scientific Awakening (1875–1917)

On December 6, 1877, Kyoto turned out in force. Nearly 50,000 people packed into the imperial park—curious, skeptical, and thrilled—to watch something no one in Japan had ever seen: a manned balloon flight.

The man behind it was Genzo Shimadzu. He was 38, a craftsman with an engineer’s itch, and he’d built the balloon himself. When it rose roughly 36 meters off the ground with its crew, it didn’t just lift into the winter air. It lifted Genzo into national fame.

And for Shimadzu Corporation, the balloon isn’t a quirky footnote. It’s the origin story in miniature: take on a technical challenge you’ve never seen before, work from imperfect information, and build anyway.

The Founder's Vision

Shimadzu’s story began two years earlier, in March 1875, in Kyoto’s Kiyamachi-Nijo district. Genzo Shimadzu Sr., born in 1839 as the second son of a Buddhist altar craftsman, stepped away from the family trade and started making physics and chemistry instruments for education. He wasn’t chasing a niche. He was chasing a national mission: raise the profile of science in Japan, and build what had previously been imported.

The timing was perfect—and tense. Japan had just been reshaped by the Meiji Restoration, the upheaval that ended the Tokugawa era and opened the country to Western technology and competition. The capital moved from Kyoto to Tokyo. Aristocrats and officials followed. Kyoto, which had been the center of the nation for a thousand years, suddenly felt hollowed out. At one point, its population reportedly fell by as much as 100,000.

So Kyoto had to reinvent itself. Industry and science became the path forward. That’s why the Kyoto Prefectural Government commissioned Genzo to build the balloon in the first place: it wanted to spark public interest in the natural sciences, and to signal that Kyoto could still be a place where the future was made.

The German Connection

Genzo’s leap from traditional craft to scientific manufacturing didn’t happen in a vacuum. It was accelerated by a very specific transfer of knowledge from Europe.

After a foreign instructor named Geerts left Kyoto, the Physics and Chemistry Research Institute brought in a German engineer, Dr. Gottfried Wagener—an unusually broad scientific mind, fluent in everything from mathematics and physics to geology, crystallography, and mechanics. Wagener taught not only science, but also the practical techniques of manufacturing industrial chemicals.

And he noticed Genzo’s workshop nearby. Wagener began asking Genzo to assemble and repair instruments and machines used in classes. The work turned into friendship, and friendship turned into apprenticeship. Wagener taught Genzo how physics and chemistry instruments were made and operated, and how to use a pedal-powered wooden lathe he’d brought from Europe.

Wagener stayed about three years. When he left Kyoto, he gave Genzo the lathe.

Today it sits at the Shimadzu Foundation Memorial Hall. It’s more than a relic. It’s a physical reminder of what Shimadzu would become: Japanese manufacturing built on precision, technique, and a willingness to learn from the best—then make it their own.

The Balloon and the Spirit of Challenge

The balloon mattered because Genzo wasn’t a balloonist. He had no experience. He hadn’t even seen one in real life. He accepted the job with almost nothing to go on—just an illustration supplied by someone named Harada.

So he improvised. To generate the hydrogen gas to fill the balloon, he bought eleven massive vats from a Fushimi sake brewery. He used them to pour dilute sulfuric acid over scrap iron.

That’s the pattern: face an unknown, build a working system anyway, and do it in public where failure is visible. Shimadzu still tells the balloon story because it captures the company’s enduring self-image—an organization that treats hard technical problems as invitations, not warnings.

Succession and Early Growth

Through the 1890s and 1900s, the company grew alongside Japan’s expanding higher-education system. Shimadzu’s first product catalog, published in 1882, listed around 110 types of instruments. These weren’t lab toys. They were the hardware of modern science classrooms, shipped to elementary schools and universities across the country.

Then, in 1894, the founder died suddenly of a brain hemorrhage. The business passed to his 25-year-old son, born in Kyoto in 1869. His childhood name was Umejiro, but when he became head of the family, he took his father’s name: Genzo Shimadzu Jr.

If Genzo Sr. provided the spark, Genzo Jr. turned it into an engine. Over his lifetime he was credited with 178 inventions and was later chosen as one of Japan’s ten greatest inventors. His education was unconventional and, in a way, perfectly Shimadzu. He studied French physics texts borrowed from his father—even though he couldn’t read French. He worked from the diagrams alone, recreating machines with screws, pulleys, shafts, and handles exactly as shown. It impressed his father and stunned everyone else.

By 1917, Shimadzu became a corporation. And by then, it was no longer just an educational-instruments shop. The company had expanded into medical equipment, storage batteries, and testing machines—early proof of a strategy it would repeat for the next century and a half: build deep technical capability, then apply it wherever measurement, reliability, and precision mattered most.

III. Building the Innovation Engine: X-rays, Chromatography, and First-Mover Advantage (1895–1970s)

The X-Ray Breakthrough

By the time Shimadzu incorporated in 1917, the company already had a pattern: spot a scientific breakthrough, learn it fast, and turn it into something useful.

The clearest early example was X-rays. In November 1895, German physicist Wilhelm Röntgen discovered a new kind of radiation that could pass through objects and reveal what was inside. He called it X-radiation—the “X” for unknown. When he announced it that December, the news raced around the world.

And Shimadzu didn’t just read about it. It tried to reproduce it.

Eleven months after Röntgen’s discovery, Genzo Shimadzu Jr. and his younger brother Genkichi, working with Professor Han’ichi Muraoka of the Third Higher School (today’s Kyoto University), succeeded in taking X-ray photographs in Shimadzu’s lab. In other words: within a year—long before modern communications, long before rapid international collaboration—Shimadzu was already doing hands-on replication of frontier physics.

That experiment didn’t stay in the lab for long. In 1909, Shimadzu completed the first medical X-ray system made in Japan. Two years later, it built large X-ray systems that used an AC power supply and delivered them to the Japanese Red Cross Otsu Hospital—helping establish Shimadzu as an early leader in Japan’s medical imaging era.

The Pattern of Domestic Firsts

Over and over, Shimadzu became the first Japanese company to turn emerging measurement science into commercial instruments. X-ray devices, the spectrum camera, the electron microscope, the gas chromatograph—again and again, the company developed and commercialized new categories ahead of domestic peers.

After World War II, that same reflex became part of Japan’s scientific rebuilding. In 1947, Shimadzu launched Japan’s first commercial electron microscope, giving researchers a new way to see the microscopic world in biology and materials science. In 1956, it introduced Japan’s first gas chromatograph—an instrument that changed analytical chemistry by making it possible to separate and analyze volatile compounds with precision.

Zoom out, and the strategy becomes visible: win at home by being first, build trust by being reliable, then use that base to expand outward as Japan’s economy accelerated in the postwar decades.

The Open Innovation Model

One reason Shimadzu could move that quickly is that it rarely worked alone. Long before anyone called it “open innovation,” Shimadzu treated universities and research institutes as extensions of its own R&D.

The origin story of its X-ray work makes the model concrete. Professor Muraoka didn’t do his experiments in a purely academic lab; he worked with the Shimadzu brothers, with Shimadzu providing the space, the equipment, and hands-on engineering support. The company even supplied the power source—a Wimshurst induction electrostatic generator—and helped run the experiments.

That loop—academics pushing the frontier, Shimadzu engineers building the hardware, each side learning from the other—became a durable advantage. It’s the same muscle the company would rely on a century later, when mass spectrometry moved from being a tool for chemists to a platform for diagnostics.

IV. Going Global: The First Wave of Internationalization (1963–1994)

Building the Global Footprint

For nearly a century, Shimadzu’s center of gravity was Japan. It built for Japanese schools, Japanese hospitals, Japanese factories, and Japanese labs. But as Japan’s economy surged in the postwar era, the company faced a new reality: if your instruments are good enough to measure the world, you eventually have to go meet the world.

So in 1963, Shimadzu opened an office in New York—its first representative office outside Japan after the war. Five years later, it moved into Europe by setting up a sales subsidiary in Germany (then West Germany). From there, the map kept filling in: offices in the Middle East, China, Latin America, and Southeast Asia. Step by step, Shimadzu built the foundation for the global footprint it operates today.

The timing wasn’t accidental. The 1960s were when Japanese companies in cars, electronics, and heavy industry started graduating from “made for Japan” to “sold everywhere.” Shimadzu was riding that same wave—just in a far more specialized business, where trust is earned one instrument, one lab, one application at a time.

The American Expansion

The U.S. was the prize market, and Shimadzu made its intentions clear in 1975 with the founding of Shimadzu Scientific Instruments, or SSI.

They headquartered SSI in Columbia, Maryland, close to Washington, D.C.—a practical choice, given the density of government agencies and research institutions nearby, and the logistics advantages of the region. But the bigger point was what SSI became. It didn’t stay a sales outpost. Its role expanded to include manufacturing and customer support. By 1983, SSI was manufacturing analytical and measuring instruments in a new building. In 1994, it opened a customer training center to deepen support for users in the field.

In a category like scientific instruments, that move matters. You don’t just ship a box and call it a day. You install, train, calibrate, troubleshoot, and keep relationships alive for years. Shimadzu was building the on-the-ground capability to do that in the world’s most demanding market.

Strategic Acquisitions

Shimadzu also used acquisitions and new plants to accelerate what organic expansion would take decades to accomplish.

In 1989, it acquired Kratos, an analytical instrument manufacturer in the U.K., expanding its position in surface analysis and the MALDI-TOF segment. That deal produced a concrete technical payoff: in 1992, Kratos developed a laser ionization time-of-flight mass spectrometer (TOF-MS).

Then in 1994, Shimadzu established a manufacturing company in Australia, part of a deliberate push to build production capabilities across four regions: Japan, Europe, the United States, and Asia/Oceania.

By the early 1990s, Shimadzu had changed shape. It was no longer just a domestic champion exporting products. It was becoming a truly global instrument company, with manufacturing and support spread across continents.

And with that platform in place, the next era of the story wouldn’t come from a flashy new market entry or a big acquisition. It would come from inside the lab—from a researcher working on a problem that, at first, looked like it might go nowhere at all.

V. The Nobel Prize Moment: Koichi Tanaka and the Power of Serendipity (2002)

The Unlikely Laureate

On paper, Koichi Tanaka didn’t look like the kind of person who wins a Nobel Prize in Chemistry. Born August 3, 1959, he was an electrical engineer at Shimadzu—one who, in 2002, shared the Nobel Prize in Chemistry with John Bennett Fenn and Kurt Wüthrich for a breakthrough method that made mass spectrometry work for biological macromolecules.

What made the news land so hard in Japan wasn’t just the prize. It was who, exactly, had won it. Tanaka was the first Nobel laureate to win without a master’s or doctorate. He hadn’t taken the traditional academic route. He’d joined a company, kept his head down, and worked in an area most people outside a lab would struggle to explain.

In other words, he didn’t look like a celebrity scientist. He looked like a working engineer who happened to be standing in the right place, with the right tools, and the right instincts, when a discovery showed up.

Tanaka graduated from Tohoku University with a bachelor’s degree in electrical engineering in 1983. He joined Shimadzu and began developing mass spectrometers. Not chemistry, not biology—instrumentation. The kind of work where progress is measured in signal-to-noise, sensitivity, and whether the machine can do what the science needs next.

Joining Shimadzu

Tanaka’s own telling of how he ended up at Shimadzu is all about contingency—how much of a career hinges on one decision, one introduction, one assignment you didn’t ask for:

"At that point, I decided that there was no need to focus solely on electrical engineering, especially because I had only two years of electrical-related knowledge. I turned to my mentor, Professor Adachi, and he was kind enough to introduce me to Shimadzu Corporation. I learned from Shimadzu's employment literature that the company was manufacturing X-ray devices and other types of medical equipment. This struck a chord with me, rekindling the possibility that I might yet satisfy my desire to help suffering people, albeit indirectly. I decided to take the employment examination, and that time, I passed without problem. However, instead of being assigned to the area of medical equipment, I learned I was to be involved in research and development of analytical instrumentation. Fortunately, that field also held interest for me, and it became the central area of my work."

He wanted to work on medical equipment. He got placed in analytical instruments instead. It felt like a detour. It turned out to be the road.

The Discovery

In February 1985, Tanaka made the key observation: by using a mixture of ultrafine metal powder in glycerol as a matrix, an analyte could be ionized without losing its structure. A patent application followed in 1985. After the application was made public, the method was reported at the Annual Conference of the Mass Spectrometry Society of Japan in Kyoto in May 1987, and it became known as soft laser desorption (SLD).

The broader impact is why the Nobel Committee cared. Matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization mass spectrometry—MALDI-MS—made it possible to ionize and analyze big, delicate molecules like proteins without destroying them. Before that, much of biology was effectively too fragile for the tool.

And the most human part of the story is Tanaka’s explanation of where it came from. Not a clean “eureka,” but what he himself called a "monumental blunder" while searching for a matrix that would enable non-destructive ionization. The mistake produced a strange, promising result—and he had the presence of mind to chase it.

He later reflected on the role of luck and not overvaluing conventional wisdom:

"But so many mistakes I made because I had no common sense but even so, just by chance or 1 out of 1,000, I can make some kind of big discovery I can make, so that was the invention which was to a Nobel Prize... do not try to rely on too much on the common knowledge, common sense."

Serendipity didn’t do the work for him. It just opened a door. Tanaka walked through it.

The Corporate Culture That Enabled It

Here’s where Tanaka’s Nobel stops being a personal story and becomes a Shimadzu story—because he was blunt about the fact that the discovery wasn’t just his.

"To say that I discovered the method of ionization does not take into account the complete story. It is necessary to point out that because the signal was so minute, the discovery could not have been made if it were not for the sensitivity and high performance of the instrument. Technologies for the mass separation mechanism, the detector and the signal processor were developed by Dr. Tamio Yoshida, Mr. Yoshikazu Yoshida, Mr. Yutaka Ido and Mr. Satoshi Akita of the research team. Many advancements that exceeded the technological levels at that time were incorporated into these components. Rather than to mention only my excellence, I believe it is more appropriate to say that the overall support of the research team was excellent. We were also probably influenced by the climate within Shimadzu Corporation, which provided a large degree of freedom for this type of research to a team composed of such young members."

That’s a very specific recipe: instruments good enough to detect a tiny signal, a team capable of pushing the core components beyond what was normal at the time, and a management environment that gave young researchers real freedom to explore.

The Nobel Prize didn’t appear out of thin air. It emerged from an organization that was willing to fund the infrastructure and tolerate the uncertainty long enough for a “blunder” to turn into a method.

The Kyoto Effect

Tanaka also pointed to something harder to quantify: place.

"Kyoto city is home to Shimadzu's main factories and research divisions, and has fostered six out of Japan's nine Nobel Prize laureates in scientific fields, including Prof. Hideki Yukawa (selected in 1949), Professor Shin-ichiro Tomonaga (1965), Prof. Ken-ichi Fukui (1981), Prof. Susumu Tonegawa (1987), Prof. Ryoji Noyori (2001), and myself. Probably no one can explain exactly why so many laureates hail from Kyoto, but the knowledge of this fact did have somewhat of an effect on me. I might even have mused that I could reach to such a level if I were to put my heart and soul into the effort."

Maybe it’s the density of universities and institutes. Maybe it’s the cultural prestige of scholarship. Maybe it’s the quiet, stubborn craftsmanship ethos Kyoto is famous for. Whatever the cause, Shimadzu sat inside an ecosystem that took science seriously—and had been doing so for generations.

The Nobel announcement, of course, changed Tanaka’s life overnight. One account described Shimadzu as promoting him to “fellow” and naming a laboratory after him. Organizations that had never heard of him suddenly wanted him on their rolls, and Kyoto University asked him to lecture.

But the most important outcome wasn’t ceremonial. It was strategic: Shimadzu now had a once-in-a-century spotlight on a core technology it owned—and a reason to invest in turning that discovery into something far bigger than a tool for researchers.

And that’s what happened next.

VI. Post-Nobel Transformation: From Instruments to Solutions (2003–2020)

Building on the Nobel Legacy

"In 2002, he received the Nobel Prize in Chemistry 'for their development of soft desorption ionisation methods for mass spectrometric analyses of biological macromolecules'. In 2003, he became the head of Koichi Tanaka Mass Spectrometry Research Laboratory."

Naming a lab after Tanaka wasn’t just a victory lap. It was Shimadzu making a clear, strategic bet: take a Nobel-winning method that changed basic research, and push it all the way into applications that could change lives.

The early reality check came quickly.

"The research originated from work awarded the Nobel Prize in 2002, though the initial methods lacked sufficient sensitivity for medical applications." MALDI was revolutionary at ionizing large biomolecules without destroying them. But the moment you try to turn that into diagnostics, you collide with a brutal constraint: the signal you care about in blood can be so faint that the original approach just can’t see it.

The FIRST Program and Sensitivity Breakthrough

The inflection point was the FIRST Program—Japan's Funding Program for World-Leading Innovative R&D on Science and Technology.

"At our research laboratory, we have worked on a study to search for blood biomarkers to predict amyloid-beta deposition in the brain, which is considered an indicator of Alzheimer's disease. One reason we followed this line of research was its selection by Japan's Funding Program for World-Leading Innovative R&D on Science and Technology (FIRST, March 2010 to March 2014)."

This wasn’t a modest grant. The program provided about 4 billion yen over five years, and the Tanaka lab assembled a team of around 60 researchers. Within a year, they reported a breakthrough: up to a 10,000-fold increase in sensitivity.

That jump is the whole ballgame. The Nobel-era technology proved you could analyze big, fragile molecules. The sensitivity breakthrough made it plausible to hunt for specific proteins and peptides in blood—exactly the kind of capability you need if you ever want to diagnose disease early, reliably, and at scale.

Global Innovation Centers

At the same time, Shimadzu was widening the aperture beyond one lab in Kyoto. Starting in 2011, it accelerated joint research and joint development—explicitly aiming to become "a number-one partner selected by customers globally."

The practical expression of that was a network of innovation centers, designed to put Shimadzu engineers closer to customers and regional research institutions, instead of keeping product development concentrated in Japan.

"Shimadzu's medium-term management plan specifies expanding businesses outside Japan and investing efforts to contribute to the 'Well-being of the Earth' in the green domain. The newly opened Environmental Health Innovation Center is expected to generate new development projects and help continue to offer solutions for the environmental measurement field."

In other words: the company was evolving from a manufacturer of best-in-class instruments into something broader—an R&D collaborator that could translate measurement technology into domain-specific solutions, whether the problem lived in healthcare or environmental monitoring.

Continued Acquisitions

Shimadzu complemented that organic build with targeted acquisitions—less about “getting big,” more about tightening the system around the core.

"In 2024, Shimadzu's scientific Instruments 'SSI' acquired ZefSci (Zef Scientific, Inc.) to strengthen their core position in the Multi Vendor Space."

The pattern here is consistent: add service capabilities, fill in technology or support gaps, and strengthen how customers actually experience the brand in the field. Shimadzu wasn’t trying to buy its way into a new identity. It was methodically extending the one it already had—precision measurement, made useful, in more places around the world.

VII. The Alzheimer's Breakthrough: From Lab to Life (2018–Present)

The Dream: One Drop of Blood

If the Nobel Prize was the spotlight, this is the moment the technology steps out of the lab and into real life.

Tanaka’s vision never really changed after 2002: use advanced mass spectrometry to detect disease from the smallest possible blood sample. That ambition became concrete in “Amyloid MS,” a blood analysis method developed by Shimadzu and Japan’s National Center for Geriatrics and Gerontology (NCGG) to screen for Alzheimer’s disease. The goal was simple to say and hard to do: predict early-stage Alzheimer’s from just a few drops of blood, around 0.5 mL.

Alzheimer’s is the perfect “measurement problem.” One of its key biological signals is amyloid beta, a peptide fragment that can begin accumulating in the brain decades before symptoms appear—roughly 20 to 30 years ahead of memory loss or cognitive decline. For a long time, the only way to confirm that buildup was after death, through pathological autopsy. Later came amyloid PET scans, which can detect abnormal amyloid accumulation in living patients.

But PET scans come with their own barriers. They’re expensive, time-consuming, and expose patients to radiation. In Japan, they’re also not covered by National Health Insurance. A blood test, by contrast, doesn’t require specialized imaging facilities—just a blood draw. If it works, it doesn’t just improve convenience. It changes access.

The Clinical Validation Journey

In 2018, Shimadzu and NCGG published joint research in Nature showing that blood-based biomarkers could predict amyloid accumulation with about 90% concordance versus PET scan results. The response was immediate and global—major newspapers around the world covered it. Inside Shimadzu’s own telling, it “triggered a big bang,” helping kick off a worldwide surge in blood-based biomarker research using many different approaches.

But one paper isn’t a clinical product. What followed was the slower, harder work: validating the method across real populations and real healthcare settings.

That’s where the next milestone comes in. Shimadzu, Eisai, Oita University, and the Usuki City Medical Association ran a cohort study in Usuki City, Oita beginning in November 2022. On October 10, 2024, they published the results in Alzheimer’s & Dementia: Translational Research & Clinical Interventions.

They evaluated how well Shimadzu’s blood biomarkers predicted amyloid PET results using AUC, and reported an AUC of 0.94—identifying PET-positive patients in the regional cohort with high accuracy. The joint research also suggested something even more consequential: baseline blood biomarker results may help predict clinical progression, including progression from mild cognitive impairment due to Alzheimer’s disease to Alzheimer’s dementia, based on participant data tracked over a seven-year observation period.

All of this points to the same practical implication: blood testing could reduce the need for amyloid PET and cerebrospinal fluid testing, lowering patient burden and potentially enabling earlier, broader screening.

Regulatory Milestone

Proof in journals is one thing. Regulatory approval is the line where science becomes medicine.

In June 2021, Shimadzu’s Amyloid MS CL became the first product in Japan to measure amyloid peptides with a mass spectrometric technique and be approved for use as a medical device. It’s a controlled medical device (Class II) available in Japan, with manufacturing and sales approval granted by Japan’s Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare in December 2020.

That approval marked a strategic transition for Shimadzu: not just building instruments for researchers, but shipping regulated diagnostics into the healthcare system.

The Broader Diagnostic Landscape

Shimadzu is not alone in chasing blood-based Alzheimer’s diagnostics—and the competition has only intensified.

Biogen has highlighted support for tau biomarker diagnostics, while its partner Eisai has invested up to $15 million in C2N, maker of the PrecivityAD test, and has collaborations with medical device companies including Sysmex, Cogstate, and Shimadzu. The market is moving because the opportunity is enormous: if a blood test can reliably replace or reduce the need for PET scans, it can reshape how Alzheimer’s is diagnosed.

That race is playing out in real time. On May 16, 2025, the U.S. FDA cleared the first blood test to aid in diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease—Fujirebio’s Lumipulse test, not Shimadzu’s. It’s a reminder that even with breakthrough science and early regulatory wins at home, leadership in global diagnostics is never guaranteed.

And the stakes are rising. As one observer put it, “I think there’s a very good expectation that the blood test could replace the PET scan.” Investors have noticed too. A market research report published in March projected that the Alzheimer’s disease diagnostic industry would nearly double between 2023 and 2032, from $4.5 billion to $8.8 billion.

Why This Matters

Stepping back, the Alzheimer’s work is the clearest through-line from Tanaka’s Nobel-era discovery to Shimadzu’s modern identity.

As described in one account, the Tanaka team developed diagnostic technology aimed at early disease detection from small amounts of blood. By modifying antibodies with polyethylene glycol at their base, the antibody arms could move like springs, enabling simultaneous binding to antigens. In experiments involving Alzheimer’s-related protein fragments, the modified antibodies captured antigens more than 100 times more strongly than conventional antibodies. Later improvements enabled glycan analysis from trace mixed samples without peptide selection, contributing to detection of Alzheimer’s-related proteins from 1 mL of blood and identification of eight previously unknown related substances. The same technology has been positioned as relevant not only for Alzheimer’s, but also for early detection of other diseases, including prostate cancer.

And that’s the full-circle moment.

Shimadzu started in 1875 making physics teaching instruments for classrooms. A century and a half later, it’s helping push diagnostics toward a future where a few drops of blood can reveal what’s happening inside the brain—years before symptoms begin. That’s not just a product story. It’s the arc of a company built around one idea: if you can measure something accurately, you can change what humanity can do about it.

VIII. The Current Strategy: Total Solutions and Future Positioning (2023–2025)

The Strategic Pivot

After 150 years of making the instruments that power science, Shimadzu is now trying to move up the stack—away from being “the box in the lab” and toward being the partner that delivers the outcome.

That ambition sits at the center of its current medium-term management plan: a deliberate shift from a product company to a solutions company. As Shimadzu puts it: "We aim to increase our corporate value by transforming ourselves into a company that provides Total Solutions across Divisions. Expand business and transform into a company that provides Total Solutions across Divisions."

What “solutions” means here isn’t a vague slogan. Shimadzu is being specific about where it believes the value is going. Instruments generate data, but customers increasingly need everything around that data: sample preparation, consumables (like columns), and software that can turn raw signals into answers.

"We have developed products using new technologies and delivered them to our customers as value. However, in order to share value with our customers, we must transform ourselves into a company that can provide the 'DATA' generated by products they need not only with products but also with Total Solutions, including pre-processing, consumables such as columns, and data analysis software. We have positioned this New Medium-Term Management Plan as a preparation period."

In other words: in analytical instruments, the differentiator is shifting from measurement to interpretation—and Shimadzu wants to own more of the workflow.

Financial Targets and Performance

Shimadzu’s plan comes with clear scorekeeping. "Our targets in FY2025, the final year of the Medium-Term Management Plan, are to achieve sales of 550 billion yen, operating income of 80 billion yen, operating margin of 14.5%, ROIC of 11.0% or above, and ROE of 12.5% or above."

On the topline, momentum has been solid. "Shimadzu had revenue of 539,047 million yen for fiscal year ending March 31, 2025, compared to 511,895 million yen the prior year." Record sales, again.

But the story underneath is the tradeoff the company is choosing to make. "For the nine months ended December 31, 2024, Shimadzu posted 384,296 million yen in sales (a year-on-year increase of 5.1%). Meanwhile, operating profit was 47,045 million yen (a year-on-year decrease of 7.3%), due to advancing growth investments including R&D and human resources for the future."

That pattern—revenue up, profit down—fits the Shimadzu we’ve been tracing all episode. They’re explicitly prioritizing long-term capability building over short-term margin preservation, even when it shows up as near-term pressure.

Geographic Shifts

Another key change is geographic. Shimadzu is navigating softness in China by leaning harder into other regions.

As the company describes it: "Sales: Increased in major regions excl. China. Japan, the Americas, and Other Asian Countries (incl. India) led growth. China's exposure down by 2.6 pts."

And India is moving from “promising market” to real footprint. "A manufacturing company will be established in March 2025, with operations scheduled to begin in spring 2027. Initially, we will focus on manufacturing AMI, but in the future, we plan to include MED and IM (TMP)."

It’s the same playbook Shimadzu used in the U.S. decades ago: don’t just sell into a region—build the ability to support, manufacture, and scale there.

Four Domains of Social Value Creation

Shimadzu is also telling its strategy through a “social value” lens—an attempt to give coherence to a portfolio that spans everything from mass specs to industrial machinery.

"We aim to enhance our corporate value by expanding our business in 3 directions ('Contributing to Human Life & Well-Being,' 'Contributing to Well-Being of the Earth' and 'Contributing to Industrial Development and a Safe & Secure Society') and 4 domains of social value creation: Healthcare, Green, Material, and Industry."

Those domains map cleanly onto what the company actually builds and sells: - Healthcare: Medical systems, clinical diagnostics, and the Alzheimer’s work - Green: Environmental monitoring, GHG analysis, PFAS detection - Material: Testing equipment for battery development and advanced materials research - Industry: Semiconductor manufacturing support and quality control systems

Shimadzu’s own plan gets concrete about where it expects growth: "◼Growing Markets: Expand GC for GHG analysis and LCMS for PFAS analysis for the Green market; expand Testing Machines for the Materials market. ◼Key Regions: Grow North America, Europe, Asia (incl. India), and China, where demand is increasing due to government support. ◼Sales Expansion by New Products: Launch multiple new products, such as LC, LCMS, GC, and Testing Machines."

Read that as: keep pushing the core instrument franchises, but point them at the problems the world is spending money to solve—healthcare capacity, environmental measurement, next-gen materials, and resilient manufacturing.

Shareholder Returns

Finally, Shimadzu is pairing long-term investment with more direct shareholder returns.

"◼Dividend: FY23 dividend increased by 4 yen vs. the initial forecast (Interim +1 yen, Year-end +3 yen), +6 yen YoY and 10th consecutive dividend increases. FY24: 62 yen per share for 11th consecutive years."

It also moved into buybacks in a bigger way. "◼Repurchase of Own Shares: Not exceeding 25 billion yen of own shares will be repurchased in order to enhance shareholder returns and improve capital efficiency. ◼Total return ratio: FY2024 total return ratio of dividends and share repurchase will be 74.6%."

The signal is straightforward: management is telling the market it can fund growth, build new capabilities around data and solutions, and still return capital with more urgency than it historically has.

IX. Competitive Landscape and Strategic Position

The Oligopoly of Precision

In most industries, “competition” means dozens of brands fighting over shelf space. In analytical instruments, it looks more like an arms race among a handful of companies that can actually build the machines.

High-performance liquid chromatography, or HPLC, is a great example. In recent years, four manufacturers—Waters, Agilent, Thermo Fisher Scientific, and Shimadzu—have consistently accounted for more than 80% of the global market. That’s not an accident. It’s what happens when the product has to be insanely reliable, globally supported, and trusted enough that researchers will bet years of work on the data it produces.

Zoom out across Shimadzu’s broader competitive set and you see the same shape. Its top competitors include Thermo Fisher Scientific, Agilent, Danaher, Bruker, Waters, and Bio-Rad. They operate at a different scale too: Thermo Fisher generates more than twelve times Shimadzu’s revenue. Thermo became that large through aggressive consolidation over the 2000s and 2010s—buying its way into categories, workflow software, consumables, and distribution, then stitching them together into a life-sciences superplatform.

Shimadzu has never played that game at Thermo scale. And that’s exactly why the next question matters: in an industry dominated by giants, how does a 150-year-old Kyoto company keep winning?

Shimadzu's Competitive Moats

One useful lens is Hamilton Helmer’s 7 Powers—ways companies sustain advantage even when smart competitors are trying to catch up. For Shimadzu, a few stand out.

Counter-Positioning: Shimadzu’s differentiation isn’t just product specs. It’s how the company behaves. The Kyoto roots, the craft culture, the patience for long arcs of research—these create a posture that’s hard for financially driven organizations to mimic. The company’s path from a Nobel Prize in 2002 to regulated Alzheimer’s-related diagnostics years later is the kind of payoff timeline that many competitors, optimized for faster cycles, struggle to sustain.

Process Power: Shimadzu’s edge is also embedded in how it builds. The company positions itself around precision technologies, user-friendly systems, and high accuracy—supported by service capabilities that keep instruments running in real labs, not just in demos. That kind of manufacturing and field-support know-how is cumulative. You don’t buy it off the shelf; you earn it over decades of shipping, maintaining, and improving complex machines.

Cornered Resource: The Koichi Tanaka Mass Spectrometry Research Laboratory—and the intellectual property and specialized expertise tied to blood-based biomarker detection—gives Shimadzu capabilities that are genuinely distinctive. More broadly, Shimadzu is widely recognized for strength in chromatography and mass spectrometry, backed by serious R&D and competitive pricing—enough to be cited as a meaningful challenge to peers like Waters.

Porter's Five Forces Analysis

Threat of New Entrants (Low): Breaking into analytical instruments is brutal. You need deep technical expertise, regulatory competence, credibility with scientists, and a global service footprint that can respond when an instrument goes down. Those are decade-scale capabilities.

Supplier Power (Low-Medium): Many components are specialized, but there are multiple suppliers for most inputs. Shimadzu also reduces dependency by developing key components internally, which limits supplier leverage.

Buyer Power (Medium): Customers—pharma companies, universities, government labs—are sophisticated. They evaluate technical performance closely, and they demand support. But in practice they don’t buy on price alone, because switching costs are real: training, method validation, and the need for continuity in long-running datasets.

Threat of Substitutes (Low): For many use cases, there is no substitute for chromatography and mass spectrometry-level measurement. Other techniques can compete at the margins, but these tools remain foundational.

Competitive Rivalry (Medium-High): Rivalry is intense, but it’s not a pure price fight. The market is growing, and the leaders tend to compete through new product development, workflow improvements, and service—exactly where Shimadzu is now trying to expand from “instrument” to “total solution.”

X. Investment Considerations: Bulls vs. Bears

The Bull Case

-

150 years of demonstrated durability: Very few companies stay relevant for a century and a half without losing the plot. Shimadzu’s cultural DNA—patient R&D, deep academic partnerships, and a willingness to invest on long timelines—has proven unusually resilient.

-

Built-in tailwinds from structural growth markets: The company’s four priority domains—Healthcare, Green, Material, and Industry—line up with trends that aren’t going away: aging populations pushing diagnostics and screening, tightening environmental regulation driving monitoring, and advanced materials and manufacturing demanding more testing and measurement.

-

Alzheimer’s diagnostics as real upside: Shimadzu collaborated with the National Center for Geriatrics and Gerontology (NCGG) to identify biomarkers that can predict amyloid beta plaque burden from just a few drops of blood. If blood-based Alzheimer’s testing becomes routine care, Shimadzu’s early lead—and its mass spectrometry credibility—could translate into meaningful strategic and financial optionality.

-

Diversification away from China: Management has been actively lowering China concentration while building out manufacturing capability in India. If executed well, that reduces geopolitical and demand-concentration risk over time.

-

The shift from instruments to total solutions: Moving beyond the box—into workflows, consumables, and data analysis—should, in theory, increase recurring revenue and make customers stickier. If Shimadzu can pull this off, it’s a higher-quality business model than one built purely on capital equipment cycles.

The Bear Case

-

Scale disadvantage is real: Thermo Fisher is roughly twelve times larger. In a world where R&D budgets, global service coverage, and bundling complete workflows can decide deals, Shimadzu risks getting outmuscled—especially in the most competitive segments.

-

China is still a meaningful swing factor: Even with diversification, China remains important. Geopolitical friction and policies that favor domestic suppliers can hit demand and pricing, and those forces are largely outside Shimadzu’s control.

-

Margin pressure from heavy investment: Shimadzu itself points to operating profit declining as it stepped up spending—particularly in R&D and human resources—bringing operating margin down year over year. That’s consistent with a “build for the future” posture, but it still raises the question investors always ask: when does operating leverage show up?

-

Alzheimer’s is getting crowded fast: Shimadzu helped pioneer the blood-biomarker approach, but competitors have moved quickly—most notably Fujirebio, which reached FDA clearance first. This may not be winner-take-all, but it does mean Shimadzu’s eventual advantage could be smaller, and harder fought, than early narratives suggest.

-

Currency sensitivity: With the majority of sales overseas but reporting in yen, swings in the currency can materially affect reported results—adding noise and risk that has nothing to do with instrument performance or market share.

XI. Key Metrics to Watch

If you’re trying to follow Shimadzu like an owner, you don’t need a spreadsheet with 200 lines. You need a few indicators that tell you whether the strategy we’ve been describing—invest now, move up the stack, expand globally—actually shows up in results.

Here are three that matter most:

1. Analytical & Measuring Instruments (AMI) segment operating margin

AMI is Shimadzu’s crown jewel, accounting for roughly 65% of sales. In the latest figures disclosed, AMI delivered sales of ¥347.9B (up 3% year over year) but operating profit fell to ¥52.1B (down 9%), taking operating margin to 15.0% (down 2.0 points).

This is the clearest “are the investments working?” metric. If margins stabilize and then expand as R&D and capability-building pay off, you’ll know this phase is value-creating rather than just expensive.

2. Healthcare and clinical revenue momentum

If you believe the most exciting upside is healthcare—Alzheimer’s biomarkers, regulated medical devices, and broader clinical applications—then you want evidence that Shimadzu can turn world-class measurement into repeatable clinical business.

The challenge: clinical revenue isn’t broken out cleanly as its own line item. So you watch the proxies—new product launches, regulatory approvals, and partnership activity in healthcare. Those signals tell you whether the Tanaka-lab lineage is turning into sustained commercialization, not just impressive science.

3. Overseas sales ratio excluding China

Shimadzu is actively reducing concentration risk while still trying to grow internationally. The company reported an overseas sales ratio of 56.5%, down 1.4 points from the previous year.

The key isn’t just “overseas” in aggregate—it’s whether growth holds up outside China. If non-China international sales keep compounding, it’s a sign Shimadzu can diversify geographically without losing competitiveness in its core instrument franchises.

XII. Conclusion: Science in Service of Humanity

On December 6, 1877, a crowd of 50,000 watched Genzo Shimadzu’s balloon rise above Kyoto. Nearly 150 years later, in labs and hospitals around the world, Shimadzu instruments help researchers see what’s invisible, separate what’s complex, and measure what used to be unmeasurable.

The line connecting those scenes is unusually straight: a belief that advancing science serves humanity; a willingness to take on hard problems without obvious near-term payoff; and a culture that prizes technical excellence over title or hierarchy.

"It is true that technology advances in an attempt to deliver things beneficial to the real world, so it is easy to see how it is useful. However, I see science as having a deeper, more profound purpose. Progress in science is guided by a sense of curiosity, or the desire to discover what is currently unknown. On the other hand, progress in technology is guided by a sense of public duty, or the desire to be useful to people."

That reflection from Koichi Tanaka captures what’s most distinctive about Shimadzu. This company has endured not in spite of its long-term orientation, but because of it. In a business world that often optimizes for the next quarter, Shimadzu has repeatedly optimized for the next frontier—then built the instruments that made that frontier real.

Whether the next 150 years resemble the last will depend on execution: can Shimadzu truly move up the stack into “total solutions,” turn its healthcare momentum into durable clinical businesses, and keep the experimental, engineer-led culture intact as it expands globally? None of that is guaranteed. The competitors are giants, the markets are shifting, and the bar keeps rising.

But the story so far suggests one thing: it’s risky to underestimate a company that has made a habit of compounding patient innovation. Genzo Sr. built a balloon from a single illustration. Tanaka turned a “monumental blunder” into a Nobel Prize. And Shimadzu turned that prize into regulated diagnostics and new possibilities for early detection.

In science, progress starts as curiosity. In business, it often starts as conviction. Shimadzu has had both for 150 years.

Note: This analysis is for informational purposes only and does not constitute investment advice. Investors should conduct their own due diligence and consult with financial advisors before making investment decisions.

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music