Don Quijote / PPIH: The Chaos Merchant Who Built Japan's Most Unconventional Retail Empire

I. Introduction & Episode Roadmap

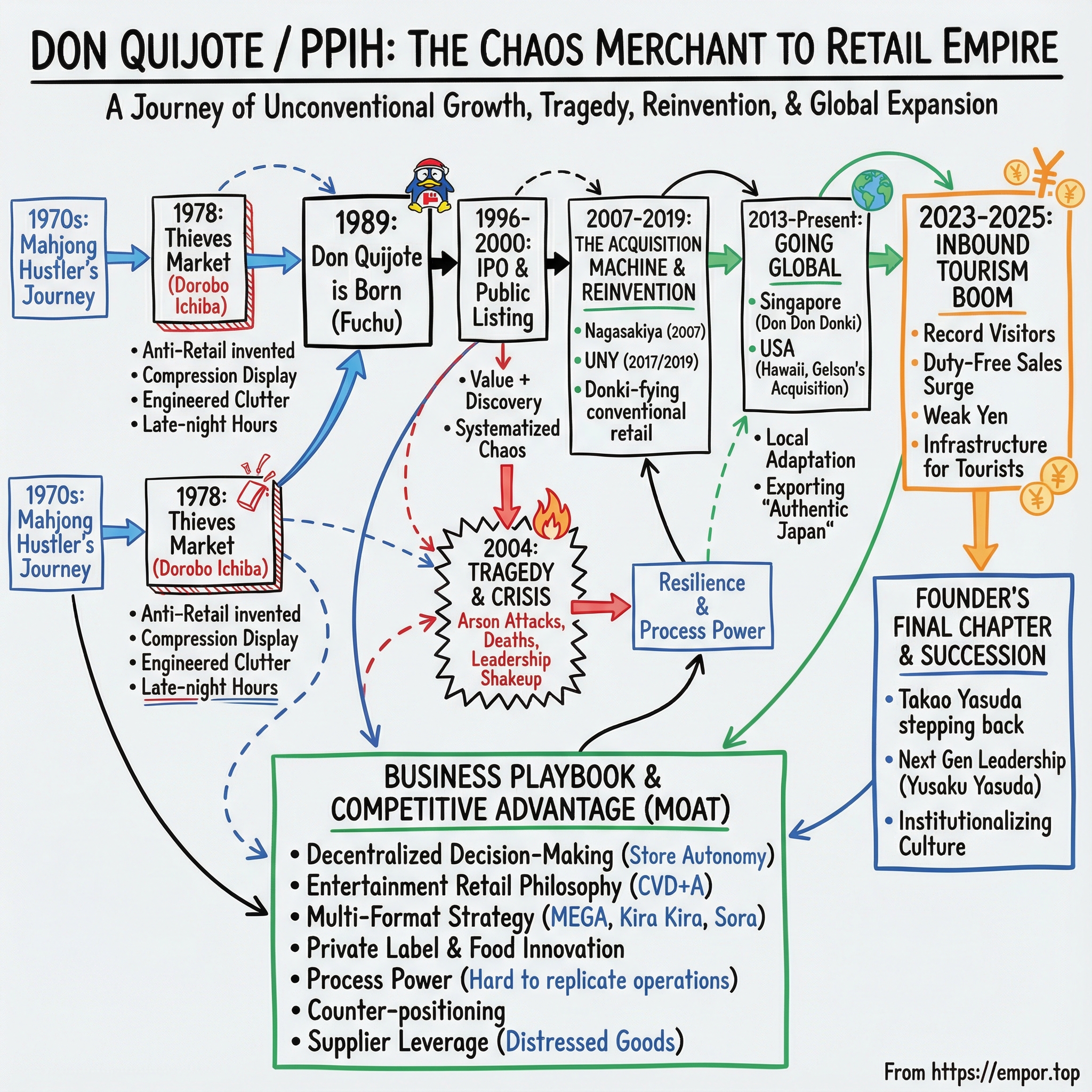

Picture the labyrinthine aisles of a Don Quijote at 2 a.m. in Tokyo’s Shibuya district. Tourists from Ohio squeeze past salary workers fresh off a late shift, all threading through narrow passages carved between towers of merchandise stacked from floor to ceiling. The theme song—“Don Don Don, Donkiiii”—thumps on an endless loop. Somewhere between the novelty gadgets and the premium cosmetics, between the gourmet snacks and the cordoned-off adult section, shoppers hit the same feeling: this is chaos… and it’s fun.

By 2024, there are more than 600 Don Quijote stores across Japan, and they’re built to feel less like errands and more like a treasure hunt. But step back for a second and the bigger question snaps into focus: how did a business this strange—now valued at more than $21 billion—get built by a founder who, by his own telling, spent much of his early adulthood playing mahjong for cash?

The numbers are almost hard to believe: since the first Don Quijote store opened, PPIH has delivered 35 consecutive years of higher sales and profits. While Japan slogged through its “Lost Decades,” while legacy retailers withered and department stores went dark, Don Quijote kept doing the one thing retailers are not supposed to do consistently in a mature market—grow, every single year.

Today, Don Quijote sits among the giants as Japan’s fourth-largest retailer, behind 7-Eleven, Aeon, and Uniqlo. The parent company, Pan Pacific International Holdings—PPIH—runs a sprawling portfolio: 501 stores in Japan, including 24 new openings in the last financial year, plus 110 more overseas across the U.S. and Asia, from Taiwan to Thailand.

So here’s the deceptively simple question that drives this whole story: how did an anti-establishment outsider create a retail format that thrives precisely because it breaks the rules every other retailer treats as sacred?

The answer winds through tragedy and reinvention, through counter-cyclical bets and a surprisingly sophisticated system of decentralized decision-making. It starts in mahjong parlors in 1970s Tokyo and stretches all the way to the waterfront enclaves of Singapore. Along the way, we’ll meet a concept called “compression display”—basically, engineered clutter—and see how what looks like madness on the sales floor became one of the most defensible moats in Asian retail.

II. The Unlikely Origins: A Mahjong Hustler's Journey

Takao Yasuda was born in 1949 in Gifu Prefecture. In 1973, he graduated from Keio University’s Faculty of Law—exactly the kind of credential that, in Japan, was supposed to put your life on rails. Keio was an elite pipeline into government ministries, banks, and blue-chip companies. A law degree from there usually meant a steady climb through respectable corporate corridors.

Yasuda, though, never really fit the “respectable” part.

After graduation, he joined a real estate firm. It collapsed in just ten months. And instead of scrambling for the next suit-and-tie job, Yasuda drifted into something that sounded like failure… but turned into training: for the next six years, he survived by playing mahjong for cash.

While his classmates were collecting business cards and learning how to nod in meetings, Yasuda spent his twenties in Tokyo’s smoke-filled mahjong parlors. It was a world of constant calculation—reading people, managing risk, staying calm when the odds flipped on you. And, most importantly, making money in messy, fast-moving environments where the “rules” were never as fixed as they looked.

Japan in the mid-1970s wasn’t an especially forgiving place to be untethered. The oil crisis had shaken confidence in the postwar boom, and the safe path still ran through big institutions. But Yasuda’s time at the tables taught him something those institutions didn’t: how to spot opportunity inside disorder, and how to bet when other people froze.

In 1978, at 29, he cashed in—using 8 million yen in winnings to open a tiny discount shop in Tokyo’s Suginami Ward. He called it Dorobo Ichiba: “Thieves Market.” It was a wink and a provocation, implying the prices were so low the merchandise must’ve been stolen.

The store was only 60 square meters, but it worked. Yasuda ran it successfully for five years. Then he sold it and shifted into a cash-and-carry wholesale business—still chasing volume, still chasing value, still moving fast.

The deeper point is that Yasuda entered retail with none of the things that normally shape a retailer: no formal training, no established network, no reverence for how a store “should” look. He would later describe himself as someone who refused to imitate major retailers, insisting that the customer had to matter most.

That little shop in Suginami became his lab. Because he didn’t know the “correct” way to do merchandising, he made choices that were, by traditional standards, wrong—messy, cramped, unpredictable. And customers didn’t just tolerate it. They enjoyed it. Shopping started to feel like discovery.

That was Yasuda’s unfair advantage: the outsider who wasn’t breaking rules to be edgy—he was breaking them because he never learned to fear them. And in retail, that kind of ignorance can be explosive.

III. The Thieves' Market: Inventing Anti-Retail

In department stores, everything was designed to be easy: easy to see, easy to find, easy to pick up, easy to buy. That was the theory.

But Yasuda looked at that theory and did the opposite.

“At that time, our Thieves’ Market did opposite of all that,” he would later say. “Our products were difficult to see, difficult to buy, and difficult to pick up… Every time the customer visited, there was a discovery.”

It’s a line that sounds like a confession. In reality, it was the founding insight of Donki: what traditional retail calls friction, customers can experience as fun. Not always. Not for everyone. But for the people Yasuda was targeting, the hunt was the point.

That’s where “compression display” came from. Don Quijote jammed shelves and hooks with merchandise, stacked high, often right up to the ceiling. Fast-moving items—drinks, snacks—might stay in their shipping cartons and get piled directly onto the floor. It did something very practical: it squeezed more assortment into limited space, kept inventory out front instead of in back rooms, and lowered operating costs. But it also did something psychological. The store didn’t feel curated. It felt endless.

And that engineered clutter worked. A large survey by the Japan Institute of Retail Economics in 2013 found shoppers routinely wandered before buying, and often left with items they never intended to purchase. Don Quijote leaned into that reality instead of fighting it. You didn’t enter with a list and glide through a tidy planogram. You entered, you explored, and you got tempted.

Here’s the part that’s easy to miss if you’ve only ever experienced Donki as sensory overload: the mess is staged. In Japan, most mature retail formats tend toward order as they scale. Don Quijote stayed “disorderly” on purpose, but it still respected path planning and conversion fundamentals. The aisles are designed to pull you deeper. The layout keeps giving you reasons to turn one more corner. It’s chaos with a steering wheel.

Then there was sourcing—another place where Yasuda refused to play by the usual rules. Donki became a home for the retail world’s castoffs: discontinued products, seasonal overruns, experimental items that didn’t work somewhere else. Japan loves limited-time releases and novelty goods, which meant there was always a fresh stream of inventory conventional retailers wanted to clear. Yasuda built a machine that could absorb it. That gave Donki variety no “normal” store could match, and prices that let it undercut almost everyone.

By the time Yasuda opened the first Don Quijote store in Fuchu, Tokyo, in 1989, he wasn’t just running a discount shop. He was refining an entirely different kind of retail experience.

Even the 24-hour schedule—one of Donki’s defining traits—was an accident that turned into doctrine. Yasuda would stay late restocking, and passers-by assumed the store was still open. They’d try the door. They’d want to shop. So he stopped turning them away and started leaving the lights on. Another “mistake” became an advantage competitors couldn’t easily copy.

The timing helped. Don Quijote didn’t throw itself into head-to-head battle with department stores or pristine supermarkets. It carved out its own territory in the nighttime economy, where sales after 8 p.m. often made up a meaningful share of the day. The late-night crowd was a mix: young singles, couples roaming the city, office workers getting off shift, service workers finishing theirs. As Yasuda put it, people get tired of karaoke, and eventually they don’t want to keep sitting in an izakaya. At Don Quijote, they can spend the same time and money, feel like they’re on a treasure hunt, and leave with something cheap and useful.

This is how Donki’s flywheel started turning. Friction created engagement. Engagement created impulse buys. Impulse buys created profit. Profit funded more assortment, more density, longer hours—and even more reasons to come back. What looked like madness on the floor was actually a new philosophy: retail as entertainment, built by an outsider who didn’t just ignore the playbook.

He inverted it.

IV. Don Quijote is Born: From First Store to IPO (1989–2000)

By the late 1980s, Yasuda’s wholesale operation was throwing off real profits. But the pull of the sales floor was stronger. In 1989, he jumped back into retail and opened the first Don Quijote in Fuchu, on the western edge of Tokyo.

On paper, it was terrible timing. Japan’s asset bubble was at full boil; the Nikkei would peak that December and then begin a long, bruising slide. Real estate prices were about to roll over. The era of effortless growth was ending.

In March 1989, the company opened its first store under the Don Quijote name in Fuchu. That wasn’t just branding—it marked a shift back from wholesale to retail. A few years later, in 1995, the corporate name changed too, from Just Co. to Don Quijote Co., Ltd.

Even the name carried a point of view. Don Quijote, the delusional knight charging at windmills, was an unmistakable signal: Yasuda wasn’t trying to fit neatly into Japanese retail. He was picking a fight with it. From the outside, the stores looked like disorder and bad taste. From the inside, there was a logic—keep it surprising, keep it dense, keep it cheap, and keep it open when other stores go dark.

And then the bubble burst, and what looked like reckless timing turned into perfect positioning.

Post-bubble Japan became a country of cautious households and price-sensitive shoppers. That should have been brutal for many retailers—and it was. But Don Quijote was built for exactly that environment. When people felt flush, they came for the weird finds, the novelty, the late-night energy. When people tightened their belts, they came because Donki could reliably be cheaper than the tidy, traditional alternatives. Different motivations, same outcome: traffic kept showing up.

Yasuda did try, briefly, to scale the “Donki experience” the easy way. He experimented with franchising and opened roughly a dozen stores that way. It didn’t work. Franchisees could copy the signs and the shelves, but they couldn’t copy the mindset—the constant improvisation, the localized merchandising, the willingness to embrace controlled chaos. Yasuda pulled back and shifted to direct operation.

That lesson mattered. Don Quijote wasn’t a format you could standardize into a binder. It was a culture you had to live inside the company. That realization would become one of PPIH’s defining management choices in the decades ahead.

The market rewarded it. In 1996, Don Quijote registered its stock for over-the-counter trading. By 2000, it made it to the First Section of the Tokyo Stock Exchange—an arrival that looked almost absurd against the backdrop of Japan’s “lost decade,” when deflation and weak consumption were grinding down retail across the country. But discount retail thrives when wallets are anxious, and Donki’s version of discount retail was also entertainment. It wasn’t just a place to save money; it was a place to feel something.

Going public brought its own pressure to “clean up.” When the company listed on the Tokyo Stock Exchange in 1999, some urged Yasuda to drop the racier merchandise. He wouldn’t entertain it. “No — businesses that ignore the nether regions are wrong,” he said. In other words: Don Quijote was not going to become respectable for investors. The customers, not the market, would decide what belonged on the shelves.

By the turn of the millennium, Don Quijote had proved a strange, durable truth: you could systematize chaos. You could grow through booms and busts by giving shoppers both value and discovery. And you could build a serious public company while refusing to act like one.

The foundation was set for the next phase. But the story wouldn’t stay fun and weird forever. A few years later, tragedy would strike—and it would test whether Don Quijote’s culture was resilient, or just loud.

V. The 2004 Tragedy: Arson, Deaths, and Leadership Crisis

In December 2004, Don Quijote’s story took a turn nobody could have imagined. Over the course of the month, four stores in the Kantō region were damaged or destroyed by arson attacks. In the first incident, three employees—Morio Oshima, 39, Mai Koishi, 20, and Maiko Sekiguchi, 19—lost their lives.

The attacks came without warning. On December 13, a fire broke out at the Urawakagetsu outlet in Saitama Prefecture. It started around 8:20 p.m. and tore through the building, gutting the store. In the aftermath, one of Donki’s core advantages suddenly looked like a vulnerability: the same densely packed merchandise that made the stores feel abundant and exciting also gave the flames more to consume.

Yasuda did what Japanese corporate leaders are expected to do in moments like this: he took responsibility. Don Quijote Co. President Takao Yasuda told reporters he intended to step down in response to the deaths. At the press conference that followed, he broke down in tears. This wasn’t a supply-chain mishap or a bad expansion bet. Three young people had died while working for his company.

And the fear didn’t lift right away. A second arson attack hit another Don Quijote store in Saitama just days later. At the Omiyaowada store, employees and security guards reportedly chased a suspect who fled the scene by car. Additional fires followed in the weeks after, extending the sense of terror through the organization—even though there were no more fatalities.

After more than a decade of relentless growth, including becoming a publicly listed company, Don Quijote was suddenly forced into a different kind of test. Yasuda stepped down as CEO and chairman. The man who had invented the entire Donki operating philosophy—its tolerance for clutter, its appetite for oddball inventory, its instinct for turning retail into entertainment—was no longer at the controls.

In 2007, Noriko Watanabe, 49, was found guilty of setting the fires and sentenced to life imprisonment. Investigators described her as a serial offender with a history of setting fires and shoplifting. Her motives remained unclear, and she said she had not intended to kill anyone. But by then, intent didn’t change the outcome.

For the board, the question wasn’t just about recovery. It was existential: could Don Quijote endure without its founder? The company had processes and stores and purchasing relationships—but Yasuda wasn’t just the CEO. He was the source code.

The answer arrived slowly, and it wasn’t linear. Eight years later, in 2013, Yasuda’s successor, CEO Junji Narusawa, stepped down due to health issues. Yasuda returned to the CEO role, but only temporarily. In 2014, Kouji Ōhara was selected to succeed him, and by July 2015 Yasuda had handed over to his second successor and remained as an advisor to Don Quijote Holdings.

That sequence revealed something crucial about what Donki had become. It wasn’t simply a cult of personality—if it were, the business would have collapsed the moment Yasuda left. But it also wasn’t fully detached from him. When the company needed him, he came back. When the next generation of leadership proved it could carry the culture forward, he stepped away again.

The 2004 arson attacks closed the first era of Don Quijote. The scrappy chaos merchant had built a phenomenon—and then tragedy forced the company to mature. What emerged on the other side was more institutional, more resilient, and still unmistakably Donki. The fires tested whether the madness was just one man’s improvisation or a repeatable system. It turned out to be both.

VI. The Acquisition Machine: Nagasakiya, UNY, and Reinvention (2007–2019)

After the fires, Don Quijote didn’t just return to business as usual. It widened the aperture. If the first era was about proving the Donki format could scale store by store, the next era was about something more aggressive: taking over other retailers—and rewriting their DNA.

In October 2007, Don Quijote bought the ailing Nagasakiya chain for 140 billion yen. It was a clear signal that this company no longer saw growth as just opening new boxes on new corners. It was becoming an acquisition machine: find a struggling retail business, buy it, and then “Donki-fy” it.

The logic was simple, and repeatable. Japan’s deflationary environment was unforgiving; plenty of retailers had decent locations but stale operations. Don Quijote could step in, strip away the conventional assumptions, and replace them with its own playbook: compression display, a huge and surprising assortment, late-night hours, and a management culture that pushed decisions down to the floor instead of up to headquarters. Stores that had been limping along as “normal” retail could be turned into loud, messy, high-velocity Donki outposts.

But Nagasakiya was just the warm-up.

The truly transformative deal centered on Uny, the operator of large general merchandise stores, including the Apita and Piago chains. In August 2017, Don Quijote took a 40% stake in Uny through a capital and business tie-up with parent FamilyMart Uny Holdings. The plan was always pointing one direction: Don Quijote would eventually take the rest.

That’s what happened. Don Quijote agreed to buy the remaining 60% stake for 28.2 billion yen, making Uny a wholly owned subsidiary—and, in the process, turning Don Quijote into Japan’s fourth-largest retailer by sales. In parallel, FamilyMart Uny pivoted its focus back to convenience stores.

Strategically, this was a very Donki move: instead of painstakingly assembling hundreds of new sites, it acquired an entire footprint—stores, leases, people, and infrastructure—then bet that its chaotic operating system could outperform the tidy, traditional one it was replacing. The integration plan was explicit: beginning in 2019, Donki aimed to convert around 20 Uny stores a year into Don Quijote or MEGA Don Quijote formats over the next five years. Management said it would keep the rest of the 90-plus Uny stores, though some would likely close once leases expired.

Analysts saw the opportunity—and the risk. Converting layouts is the easy part. The real work was cultural: bringing Uny’s senior leaders and store teams into Donki’s decentralized way of running retail, where local employees are empowered to adjust pricing and merchandising rather than waiting for instructions from above. In the short term, that “indoctrination” was widely viewed as the biggest challenge.

And then it started working.

UNY’s Apita and Piago locations were converted into Don Quijote UNY and MEGA Don Quijote UNY formats, and the pattern was consistent: conversions brought meaningful sales improvements at the store level. It was proof that Don Quijote hadn’t just invented a weird store experience. It had built a repeatable turnaround engine.

In 2019, the company changed its name to Pan Pacific International Holdings. It was more than a cosmetic rebrand timed to the 30th anniversary of the first Don Quijote store. It was a statement: this was no longer just a single-format discount chain. It was a broader retail group, spanning formats, and increasingly spanning geographies.

Zoom out, and the moat becomes clearer. Each acquisition didn’t just add doors. It added real estate, distribution muscle, customer relationships, and experienced operators—then plugged all of it into the Donki system. Growing by buying weakened competitors also meant Don Quijote could expand faster and cheaper while taking pressure out of the market.

By the end of this phase, investors had a new way to understand the company. Don Quijote wasn’t only great at operating Don Quijote. It was great at transformation—taking conventional retail assets and making them better. The treasure-hunt store was the brand. The real advantage was the management machine behind it.

VII. Going Global: From Singapore to California (2013–Present)

By the mid-2010s, the Don Quijote machine was no longer just a Japan story. It was an Asia story—and, soon, an American one too.

In 2015, Takao Yasuda stepped down and did something that felt both like retirement and like a next move. At 68, he relocated to Singapore with his wife and bought a S$21.25 million home on Sentosa Cove. The founder of Japan’s loudest, messiest retailer had chosen one of Southeast Asia’s most polished waterfront addresses.

But Yasuda’s move wasn’t simply about slowing down. In Singapore, he saw a gap that looked familiar: Japanese goods were popular, but they were priced like luxuries. And, crucially, he couldn’t find a retailer doing what Donki did best—selling Japanese products, with fresh food at the center, at prices that felt genuinely accessible.

That observation became the seed of PPIH’s Southeast Asian expansion.

In December 2017, the company opened its first store in Singapore. It couldn’t use the Don Quijote name—rights were tied up with a local restaurant—so it went with Don Don Donki. It was a small but telling moment: expanding globally meant adapting, even for a company built on stubborn independence.

Yasuda pushed hard for the rollout. After moving, he’d been shocked by how expensive Japanese products were in Singapore. Don Don Donki aimed to reset expectations, with prices as much as 50% lower than rival shops selling Japanese goods.

The issue, as Yasuda saw it, was cultural and structural. Japanese food was already widely loved by locals, but it could sell for two to four times what it cost back home. The markup was so accepted it even had a nickname: the harmony price—an unspoken agreement that middlemen would take their cut, and customers would just live with it. Yasuda didn’t accept it. “How dare they neglect the customer this much?” he said.

Singapore was the proof point. And once it worked, it spread.

By June 2024, there were 45 DON DON DONKI stores across six countries and regions, with strong local followings. The Singapore operation kicked off a broader regional push—into Hong Kong, Thailand, Taiwan, Malaysia, and Macau—markets where “authentic Japan” was a powerful draw and where the Donki treasure-hunt experience translated surprisingly well.

The United States was a different problem entirely. Here, Donki wasn’t exporting a Japan experience into Japan-curious consumers. It was stepping into mature retail markets with entrenched habits, fierce competition, and very different economics.

One part of the U.S. strategy started in familiar territory: Hawaii. In June 2017, PAQ—operator of the Honolulu-based Times, Big Save, and Shima stores through its subsidiary QSI, Inc.—sold its 24 Hawaii stores to Honolulu-based Don Quijote (USA). The deal combined those stores with three Don Quijote stores and two Marukai stores on Oahu.

Hawaii made sense as a beachhead: a large Japanese-American community, deep cultural familiarity with Japanese brands, and a customer base already open to Japanese retail formats. But the bigger prize was always the mainland—especially California.

In 2021, PPIH made its most surprising U.S. move yet: acquiring Gelson’s, the upscale Southern California grocery chain with 27 stores. The seller was TPG Capital, and financial terms weren’t disclosed. Gelson’s had been gaining market share and held strong positions in fast-growing population centers.

On the surface, it looked like the opposite of Don Quijote’s DNA. Gelson’s served affluent shoppers who cared about premium products and personalized service—far from the chaotic, value-driven aisles that made Donki famous. Gelson’s generated $872 million in net sales in 2020, and PPIH clearly wasn’t buying it to turn it into a discount treasure hunt.

Instead, the purchase signaled something bigger: PPIH wanted overseas retail to become a third pillar of earnings, alongside its discount stores and general merchandise outlets. In Asia, the export was straightforward—Japanese products and the Donki experience to markets hungry for both. In the U.S., the approach leaned more like PPIH’s Japan playbook: acquire established local assets, keep what already works, and look for advantages in procurement and operations.

By now, the footprint is enormous: 501 stores in Japan, including 24 new openings in the past financial year, plus 110 stores overseas across the U.S. and Asia from Taiwan to Thailand.

The takeaway is that “going global” didn’t mean copy-pasting Don Quijote everywhere. It meant applying the same underlying instinct—find what customers are being overcharged for, find what traditional retailers won’t do, and build a model that feels a little unreasonable… until it works.

VIII. The Inbound Tourism Boom: Donki as Japan's Gateway (2023–2025)

In 2024, Japan welcomed a record 36.9 million international visitors, up 47.1% year on year. According to the Japan National Tourism Organization, that wasn’t just a rebound from COVID-era lows—it blew past the previous high-water mark of 31.9 million set in 2019.

That surge has quietly redefined what Don Quijote is. It’s still a domestic discount retailer. But it has also become something closer to infrastructure for inbound travel: a can’t-miss stop where visitors stock up on everything from cosmetics to snacks to souvenirs, all in one neon-lit maze. It’s common to hear tourists asking strangers on the street, “Where’s the nearest Donki?” And the money follows the foot traffic. In the first half of the fiscal year ending June 2025, duty-free sales at Pan Pacific International Holdings hit an all-time high of ¥79.8 billion, up ¥29.7 billion from the same period a year earlier.

A big driver has been the yen. The weaker it gets, the more Japan starts to feel like it’s on sale. In 2019 the exchange rate hovered around ¥110 to the U.S. dollar. By 2024 it had slid into a much weaker range—around ¥140 to ¥160—turning Japan’s food, service, and shopping into an easy “yes” for travelers.

And the wave didn’t stop. On December 17, 2025, Japan’s tourism boom hit another milestone: JNTO data showed estimated cumulative inbound visitors from January through November 2025 reaching 39,065,600—already topping 2024’s full-year record, with more than a month still to go.

For Don Quijote, what makes this moment so powerful is the two-sided demand it’s capturing at the same time. On one side: tourists, arriving with shopping lists and suitcases to fill, chasing the “only in Japan” retail experience. On the other: local shoppers, squeezed by rising prices and looking for relief.

As inflation pushed households to cut back, Don Quijote increasingly became the practical choice, too. Core inflation accelerated to 3.2% in March, and consumers felt it in everyday pain points—electricity bills, plus staples like cabbage and rice. Household consumption fell 1.1% in 2024, and some shoppers responded the old-fashioned way: they traded down, and they made the trip to Donki.

So the same stores that can look chaotic, even a little disreputable, to some Japanese shoppers read completely differently to visitors. To tourists, the clutter is magic. To locals, it’s value. Either way, the registers ring.

PPIH is leaning into that momentum. The company plans to open 250 new stores by 2035, explicitly betting that inbound tourism remains strong. Tourist sales, in particular, have become a priority: it plans to open two new Japan stores targeted at visitors in 2026, centered on duty-free products. The network is increasingly segmented—some locations tuned for the suitcase-and-souvenir mission, others optimized for local, daily needs.

And Donki isn’t treating this as a passive tailwind. It has openly declared an ambition to become the number one must-visit spot in Japan, with a simple three-step approach: get travelers thinking about Donki before they even depart, delight them while they’re in-store, and then nudge them to broadcast the experience to friends and followers afterward.

In 2024, Donki pushed that playbook into overdrive with a promotional video collaboration featuring global music icon Bruno Mars. The campaign generated major buzz in Japan and overseas, and Mars’s involvement was reportedly driven by something unusually authentic for a brand partnership: he genuinely liked shopping at Donki.

Zoom out and you can see how neatly the world has bent toward this model. Tourism delivers high-margin duty-free sales. Inflation pushes domestic shoppers toward discounts. A weak yen makes Japanese goods feel like a bargain. And the sensory overload of Don Quijote—its chaos, its surprises, its sheer “what am I looking at?” energy—produces the kind of organic social media that no marketing budget can reliably manufacture.

Sometimes the best strategy really is being built for the moment when the tide turns.

IX. The Founder's Final Chapter: Succession and Legacy

Founder Takao Yasuda, battling terminal lung cancer, has been preparing to hand over a fortune of nearly $6 billion to his 24-year-old son, Yusaku Yasuda. And hanging over that personal story is a corporate one: Pan Pacific International Holdings, the parent of Don Quijote, valued at more than $21 billion—a retail empire built on chaos, now facing the most orderly question of all: what happens when the founder is gone?

What’s unfolding at PPIH is less a soap opera than a case study. Yasuda has spent years trying to make sure the company—and the family—can survive him.

A decade ago, he handed day-to-day operations to professional, non-family executives. That separation of ownership and management wasn’t just good governance on paper; it created the conditions for PPIH to keep expanding across Asia without every major decision needing the founder’s fingerprints.

Just as importantly, Yasuda has been careful about how the next generation shows up. Yusaku, 24, sits on PPIH’s board, but only as a director with no executive authority. Yasuda’s reasoning is blunt, shaped by what he’s watched happen elsewhere: when founding families and professional management collide, the fallout can become a full-blown governance crisis—and the business pays the price.

The planning extends beyond org charts. Yasuda’s controlling stake sits in a Dutch holding vehicle worth about $4.7 billion, while his residency in Singapore helps shield the family from Japan’s inheritance tax, which can claim as much as 55% of an estate. Analysts have noted that structuring can reduce the risk of forced share sales—exactly the kind of scramble that can dilute control and destabilize a company at the worst possible time.

So what, exactly, is Yusaku inheriting in practice? Not the CEO seat. His role is narrower: engage younger employees, show up to board meetings, and represent continuity—while the business itself is expected to remain in the hands of an experienced management team. That expectation showed up in the market, too: when news of Yasuda’s illness became public in July, PPIH’s shares barely moved.

That calm reaction says something important. This is not a company priced like it will lose its mind without its founder.

Yasuda himself has explained the logic in almost moral terms:

At 65 years old, I thought it was time because of our management principles which I put together. It had one article: a leader must remove his or her authority and give it to the successor. So, unless I myself do it as an example, there really was no meaning in coming up with the management philosophy. So, even if I did not want to retire, I had to put myself in a corner and do it.

It’s the opposite of the classic founder story—where the visionary clings to power until the very end, and everyone pretends not to notice the succession problem until it becomes an emergency. Yasuda stepped back once in 2005 after the arson tragedy, then made the more permanent handoff in 2015. By removing himself, he forced the organization to prove it could run on something other than charisma.

And the company is behaving like it believes that, too. PPIH has said it operates 655 stores in Japan and still sees meaningful room to grow. It plans to open 250 additional stores by fiscal year ending June 2035. The 2035 growth plan—“Double Impact 2035”—aims to nearly double operating income while materially expanding the store network. Whatever happens next in Yasuda’s personal chapter, the business is not planning to coast.

That may be his most unusual legacy. Not just building a successful company—but building a system designed to keep succeeding without him.

X. Business Playbook: What Makes Donki Work

Takao Yasuda, the founder of the PPIH Group, built Don Quijote around a simple, stubborn premise: don’t imitate the major retailers. Stand apart. Put the customer first, every time.

That philosophy sounds like a slogan until you see how it shows up in the operating system. Don Quijote’s success isn’t one clever trick. It’s a set of interlocking choices—each weird on its own, but together forming a competitive position that’s incredibly hard to copy.

Decentralized Decision-Making: Donki breaks the classic chain-store model of uniform store design and centralized control. Instead of headquarters dictating assortment, purchasing, and pricing, authority is pushed down to the stores. Frontline staff can actively shape what gets stocked and how it gets sold—often down to the level of an individual sales floor.

That delegation isn’t just ideological; it’s reinforced with incentives. Store employees’ pay is linked to performance metrics like sales, gross profit, and inventory turnover. The point is to make the people closest to the customers feel like operators, not clerks—to turn local knowledge into faster decisions and better merchandising.

This is why no two Don Quijote stores feel the same. Each location reflects its neighborhood, its competition, and the instincts of the team running it. The result doesn’t feel corporate-engineered. It feels alive.

Entertainment Retail Philosophy: Traditional Japanese management culture loves tidiness and order—often expressed through 5S: sort, set in order, shine, standardize, and sustain. Don Quijote famously swerves the other way. It built its own logic around convenience, discounts, and, crucially, amusement.

Inside PPIH, that idea is sometimes framed as CVD+A: Convenience, Discount, plus Amusement. The “A” isn’t decoration. It’s the product. The stores are designed to reward exploration, surprise you with variety, and make the act of shopping feel like a game—especially for customers who don’t want retail to feel like a chore.

Multi-Format Strategy: Donki is not just one kind of store anymore. Alongside the classic Don Quijote locations, PPIH has developed a growing set of formats aimed at different missions and different customers. There’s MEGA Don Quijote, built around a wider assortment and “surprisingly low prices.” There’s Kira Kira Donki, designed with SNS-worthy products for Gen Z shoppers. And there’s Sora Donki, which curates items that resonate with tourists.

Different formats, same underlying playbook: curiosity, value, and a reason to stay longer than you planned.

Private Label Innovation: PPIH has invested heavily in private brands including JONETZ, Style One, Prime One, and eco!on. The mix matters here. A large share of what Donki sells is standard, everyday merchandise you could buy elsewhere. But the rest—unique items, unusual finds, and heavily discounted product sourced by expert buyers—is what creates the “treasure hunt” feeling and gives customers a reason to choose Donki over a more orderly alternative.

Food Retail Innovation: The company has also been creative in how it sells “Japan” overseas—especially through food. Tomita Seimai, which opened in Singapore in November 2021, and Yasuda Seimai, which opened in Hong Kong in June 2022, became popular shops centered on a simple insight: most non-Japanese customers can’t judge the quality of Japanese rice by looking at it. So the rice-milling shops started selling onigiri rice balls, letting customers taste the difference immediately.

Put it all together and you get the Donki paradox: the stores look easy to imitate—stack goods high, narrow the aisles, crank the energy—but the advantage isn’t the clutter. It’s the system behind it. Competitors can mimic the compression display. What’s far harder to replicate is the decentralized culture, the incentives that make staff act like owners, the sourcing relationships, and the accumulated know-how of what actually makes treasure-hunt retail work.

XI. Strategic Analysis: Porter's 5 Forces & Competitive Position

Threat of New Entrants: LOW-MEDIUM

From across the street, the Don Quijote “format” can look like a gimmick: stack products to the ceiling, cut prices, keep the lights on late. But the moment you try to copy it at scale, you run into the real barriers—ones that aren’t visible in the aisles.

“I haven't seen anything else quite like Don Quijote,” says Michael Causton, a retail analyst in Tokyo for Japan Consuming. “It's chaotic, messy stores, which belie what's behind it—a highly disciplined, extremely rigorous management philosophy.” Investors seem to agree.

To replicate Donki in a meaningful way, you don’t just need clutter. You need supply relationships strong enough to support constant assortment change, the real estate chops to take over and rework imperfect properties, and a culture that’s comfortable with local autonomy instead of top-down control. Then you need time—years of operating muscle memory—to make all of that feel effortless to the customer.

Brand helps too. The Donpen penguin, the yellow-and-black signage, and that jingle that drills into your brain create recognition and affection that newcomers can’t manufacture overnight. And as PPIH gets bigger, procurement and distribution advantages keep compounding.

Bargaining Power of Suppliers: LOW

PPIH was built on an unusually supplier-unfriendly insight: trouble is inventory.

From the earliest days, the company actively sought out distressed goods—bankruptcies, overruns, discontinued items—and turned other companies’ problems into Donki’s assortment advantage. That history matters because it shaped how PPIH buys: opportunistically, at scale, and with a willingness to take product that doesn’t fit “normal” retailers.

Today, that scale gives PPIH leverage. And private label expansion further shifts power away from any single supplier, because PPIH can fill shelf space with its own brands when it wants to.

Bargaining Power of Buyers: MEDIUM

Customers can always go somewhere else. Switching costs for everyday purchases are basically zero.

But Don Quijote blunts that reality with something most retailers can’t create on command: habit. People don’t only go to Donki to buy a specific item; they go to see what they might find. The “treasure hunt” experience turns shopping into repeat entertainment, which raises loyalty even when prices aren’t the only thing that matters.

Threat of Substitutes: MEDIUM

The cleanest substitute is e-commerce. In theory, online shopping should be a direct threat to any big-box-style retailer.

In practice, Don Quijote has held up unusually well because the core product isn’t just the merchandise—it’s the experience. Donki shopping is sensory, impulsive, and social. Algorithms can recommend products, and delivery can be fast, but neither can recreate the feeling of turning a corner and finding something you didn’t know you wanted.

Competitive Rivalry: MEDIUM-HIGH

Japan’s retail market is relentless: discount stores, convenience store giants, supermarkets, and even surviving department stores all compete for the same consumer yen.

Don Quijote’s advantage is that it doesn’t always fight on the same battlefield. Its 24-hour orientation and strength in the nighttime economy shift demand into hours when many competitors are weaker. And the format is distinct enough that, even when the product overlaps, the shopping mission often doesn’t.

Hamilton's 7 Powers Analysis:

Counter-positioning: Don Quijote is a standing rebuke to traditional retail norms. Incumbents can’t simply flip to compression display, 24-hour operations, and decentralized merchandising without breaking what their current customers and operating models expect.

Scale Economies: With hundreds of stores in Japan and a growing overseas base, PPIH benefits from purchasing scale and distribution efficiency that smaller chains can’t match.

Network Effects: There aren’t strong classic network effects, but Donki does get a kind of indirect boost: loyal fans, tourist “must-visit” lists, and social sharing that amplifies awareness.

Switching Costs: Low per transaction, but behavioral switching costs are real. Once customers get used to the Donki hunt—“I’ll just pop in and see”—it’s hard to replace with a purely utilitarian store.

Brand: Donpen, the theme song, and the unmistakable storefront have become cultural signals, built over decades and hard to replicate quickly.

Cornered Resource: PPIH’s buyer network, vendor relationships, and know-how in converting and operating unconventional retail spaces are not assets competitors can buy off the shelf.

Process Power: The real moat is operational. Compression display, store-level autonomy, and the accumulated routines of running “controlled chaos” add up to process knowledge that rivals can admire… and still struggle to reproduce.

XII. Key Performance Indicators and Investment Thesis

If you’re looking at PPIH through an investor lens, a handful of metrics tell you whether the Donki machine is still compounding—or whether the flywheel is starting to wobble.

1. Same-Store Sales Growth (SSG)

This is the cleanest read on organic momentum. Same-store sales strip out the sugar high of new store openings and tell you whether existing locations are getting stronger—earning more trips, bigger baskets, or both. Historically, PPIH has managed to keep SSG positive even in weak consumer environments, which is exactly what you’d expect from a discount format that also functions as entertainment.

2. Tax-Free Sales to Inbound Tourists

This is the clearest gauge of the tourism tailwind. In the first half of fiscal year 2025, duty-free sales hit an all-time high of ¥79.8 billion, up ¥29.7 billion year over year. It’s a direct measure of how successfully Donki has positioned itself as a “must-visit” stop for travelers. It’s also a reminder of what to watch: sensitivity to currency moves and any policy shifts that affect inbound travel.

3. Store Conversion Margin Improvement

PPIH doesn’t just grow by opening new stores—it grows by taking tired retail boxes and rewiring them. When it buys chains like UNY or Nagasakiya, one of the most revealing indicators is the margin gap between the business before conversion and after it gets “Donki-fied.” A meaningful improvement suggests the playbook is still potent—and that there may be more value to extract from future acquisitions.

The Bull Case:

- Japan’s inbound tourism keeps setting records, and government targets of 60 million visitors by 2030 would provide a long runway

- Inflation pushes more domestic shoppers toward discount retail

- The plan to open 250 new stores by FY6/35 signals management sees real growth opportunities ahead

- The decentralized operating model and culture are durable advantages that are difficult for competitors to copy

- A proven ability to integrate acquisitions creates ongoing M&A upside

- Succession planning reduces key-man risk despite the founder’s illness

The Bear Case:

- Tourism-linked earnings make PPIH vulnerable to pandemic-style shocks, geopolitical disruptions, or a stronger yen that makes Japan less compelling for travelers

- Overseas expansion—especially Gelson’s in California—pushes into categories and markets where PPIH’s traditional advantages may translate less cleanly

- The founder’s passing could still affect culture and strategic direction, even with succession planning in place

- Rising private equity interest in Japanese retail could intensify competition for acquisition targets

- E-commerce could eventually erode some of the categories where Don Quijote thrives

- Urban real estate costs could compress margins if rent rises faster than the company can offset through pricing, mix, or efficiency

Regulatory and Accounting Considerations:

The founder’s shares being held through a Dutch holding vehicle is presented as legitimate tax planning, but it can attract scrutiny—both from Japanese tax authorities and from ESG-focused investors. Separately, the late-night operating model periodically draws regulatory and community pressure tied to noise and public-order concerns, especially in residential areas.

Valuation Context:

For the fiscal year ended June 30, 2024, PPIH recorded net sales of 2,095.1 billion yen. The company trades on the Tokyo Stock Exchange Prime Market under ticker 7532. As with any retailer, valuation ultimately comes back to the basics: same-store sales momentum, margin direction, and how much of the earnings mix is coming from relatively volatile tourist demand versus steadier domestic traffic.

The Don Quijote story refuses to sit neatly in a category. It’s outsider innovation paired with insider discipline. It’s controlled chaos executed with systems. It’s deeply Japanese—and increasingly global.

And for investors, the core insight may be the simplest one: Don Quijote didn’t win despite breaking the rules. It won because breaking the rules created a kind of barrier that rule-followers can’t easily cross. The chaos was intentional. The mess was the point.

With the management succession largely set, and after publicly disclosing his battle with terminal lung cancer, Yasuda closed his latest book with a stark sign-off: “Good luck, and good bye!” He added a final message that sounds like both a personal philosophy and a blueprint for the company he built: “At work and in life, create for yourself an environment where you can always seek the most fun and fulfillment, in pursuit of ultimate freedom.”

In the end, that might be the truest description of what Don Quijote sells. Not just discounts, but discovery. Not just products, but adventure. Not just shopping, but a treasure hunt that never quite ends.

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music