Ryohin Keikaku (MUJI): The "No-Brand" Brand That Changed Retail

I. Introduction & Episode Roadmap

Picture yourself walking into a store where everything feels like it forgot to put on its name tag. Notebooks with plain covers. Furniture that’s all clean lines and calm materials. Clothes in quiet, earthy colors. No loud logos, no screaming patterns, no “look at me” branding—just objects that seem confident enough to stand on their own.

That’s MUJI. And it immediately sets up the delicious paradox at the heart of this story: how does a “no-brand” become one of the most recognizable lifestyle brands in the world?

On paper, Ryohin Keikaku Co., Ltd. is a retailer of household goods and food, in Japan and abroad. In reality, MUJI is a whole ecosystem. There’s MUJI to GO for travel essentials. ReMUJI for reuse and recycling. MUJI STAY accommodations under the MUJI HOTEL name. MUJI 500 shops built around everyday low-priced items. Café&Meal for food and drink. IDÉE for furniture and accessories. Even MUJI HOUSE for residential solutions. It’s not just selling things; it’s selling a very specific idea of how life could look, feel, and function.

The name itself is the mission statement. Mujirushi Ryōhin translates to “no-brand quality goods.” And that wasn’t a cute marketing twist—it was a real provocation in 1980, right as Japan’s bubble-era appetite for status, luxury, and conspicuous consumption was taking off. MUJI’s founders essentially asked: what if quality didn’t need a label?

From there, the “no-brand” brand traveled. MUJI opened its first overseas store in London in 1991, and over the decades it grew into a global chain with 1,364 outlets across 29 countries and regions. For the fiscal year ending August 2024, Ryohin Keikaku reported record consolidated sales of ¥661.6 billion (about $4.4 billion).

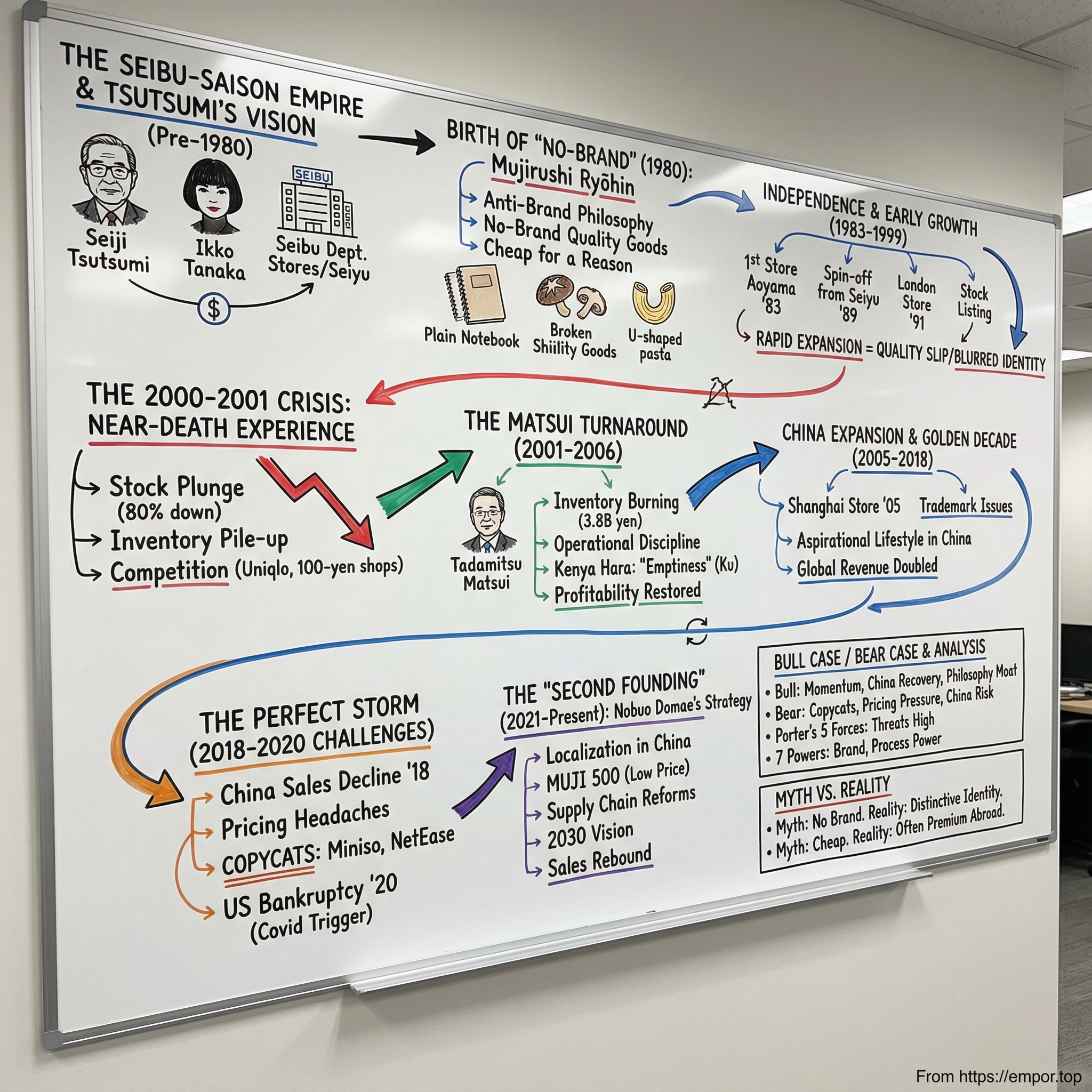

This episode is the full arc: creative genius meeting commercial pragmatism; near-death mistakes that almost killed the company; and reinventions that brought it roaring back. We’ll go from Seiji Tsutsumi’s cultural empire to MUJI’s operational revolution, from China’s golden decade to the copycat wars and pricing headaches that followed—and finally to the “Second Founding” that’s meant to shape MUJI’s next era.

If there’s a thesis to keep in your head as we go, it’s this: MUJI proves that rejecting branding can be the most powerful brand strategy of all—if you have the philosophy, and the execution, to make it real.

II. The Seibu-Saison Empire: Seiji Tsutsumi's Vision

To understand MUJI, you first have to understand the world that made MUJI possible—and the unusual man who built that world.

Seiji Tsutsumi (1927–2013) ran what became the Seibu–Saison Group, a retail and distribution empire that didn’t just sell products, but shaped taste. Under its umbrella sat businesses and institutions that, taken together, felt less like a company and more like a self-contained universe: Seibu department stores, Parco shopping malls, Seiyu supermarkets, and cultural outposts like the Seibu Museum of Art and Seibu Theater. The wider orbit included brands and retailers that would become household names in Japan—FamilyMart, Loft, and Libro among them. MUJI would emerge from this ecosystem, not as an accident, but as a logical next move.

Calling Tsutsumi “a businessman,” though, misses what made him so consequential. As a student at the University of Tokyo in the late 1940s, he was drawn into left-wing politics in the chaotic years after the war. He joined the Japan Communist Party in 1949, only to be pushed out a year later amid internal factional conflict. After a bout of tuberculosis, he recovered, became his father’s private political secretary, and then—at his father’s direction—entered the family’s retail business in 1954.

That path matters because it shaped the way Tsutsumi approached commerce. When he accepted the appointment, he did so with two conditions: that the company establish a labor union, and that it begin recruiting university graduates—both uncommon in retail at the time. It’s a striking image: a former communist activist stepping into the heart of consumer capitalism, carrying with him a serious critique of what consumption could do to people and society. Decades later, MUJI would feel like that critique, translated into products.

Operationally, Tsutsumi was a builder. He joined Seibu Department Stores in 1954, became president of Seiyu—the supermarket chain he founded—in 1963, and then president of Seibu Department Stores in 1966. But what he constructed wasn’t just scale. In the 1970s and 1980s, he turned the group into something closer to a cultural movement. He believed retail could deliver more than material goods—that it could offer a sense of modern Japanese style, and make everyday life feel charged with meaning.

So he surrounded himself with creators: copywriters, graphic designers, spatial designers—the people who didn’t just advertise culture, but produced it. Seibu’s ambitions were visible right on the sales floor. From early on, Tsutsumi pushed the business to be explicitly culture-oriented: inviting French designers like Louis Féraud, Ted Lapidus, and Yves Saint-Laurent, and staging major fine-art exhibitions—from Paul Klee to Salvador Dalí to German Expressionism. Those efforts culminated in 1975 with the opening of the Seibu Museum of Art inside the department store itself.

Then came the decisive pairing. In the 1970s, as design leadership in Japan shifted from the state to corporations, Ikko Tanaka was appointed creative director of the Seibu Group. Together, Tanaka and Tsutsumi helped define what people later called Seibu–Saison culture—the look, language, and sensibility that set the tone for Japanese urban life in that era. And on the eve of the bubble economy, Tsutsumi would use that same machinery—retail plus design plus philosophy—to plan something deliberately countercultural: MUJI, positioned as an alternative to consumer society.

The result was a group that felt almost impossible by today’s standards. Its campaigns could read like literature. Its stores doubled as galleries. Its leadership spoke in the vocabulary of aesthetics and ideas. And at the center stood Tsutsumi: poet and intellectual, but also a hard-edged operator, convinced that commerce and culture weren’t opposites—they were two ways of organizing human desire.

For anyone trying to understand MUJI’s durability, this origin story is the key. MUJI wasn’t born as “cheap minimalism.” It was born as a philosophical stance—about consumption, waste, taste, and what a “good life” ought to look like. And that, more than any specific product, is what has always been hardest for competitors to copy.

III. Birth of the Anti-Brand: MUJI's Founding Philosophy (1980)

In 1979, with Japan speeding toward bubble-era excess, Seiji Tsutsumi convened a small group inside the Seibu orbit to talk about a strange idea for that moment in history: what if the next big thing wasn’t a louder brand, but a quieter one? What if the product didn’t need a story pasted onto it—because the story was the restraint?

The result was Mujirushi Ryōhin, literally “no-brand quality goods.” It began in 1980 as a private-label concept for Seiyu, the Seibu Group’s supermarket chain. (The name “MUJI” came later, as the shorthand the world adopted.) Tsutsumi’s direction was crisp: the concept needed an anti-establishment spirit, and it needed a consistent image—minimal, simple, but still unmistakably designed.

To make that real, Tsutsumi leaned on the same creative machinery that powered Seibu–Saison culture. Graphic designer Ikko Tanaka worked alongside marketing consultant Kazuko Koike and interior designer Takashi Sugimoto to build Mujirushi Ryōhin’s identity. Tanaka pushed for recycled paper packaging and a restrained mark: the four kanji characters printed in maroon, with nothing else begging for attention. As a member of the advisory board, he also influenced the products themselves—arguing for natural textures and honest materials, and resisting the glossy, pigment-heavy plastic look that defined so much “modern” consumer goods at the time.

Tanaka wasn’t some minimalist hobbyist. He was one of Japan’s most celebrated graphic designers, known for major identity work across industries, and for an ability to fuse modern typography with a deep sensitivity to traditional Japanese aesthetics. MUJI gave him a new canvas: not to decorate products, but to subtract until what remained felt inevitable.

The founding product strategy matched that philosophy. MUJI didn’t launch by claiming it was better. It launched by explaining why it could be cheaper. The slogan Tanaka designed—written by Koike—said it plainly: "わけあって、やすい" (“Cheap for a reason”).

And the reason was radical transparency about what customers were usually paying for: cosmetic perfection, packaging, and brand markup. Two early products made the point instantly. One was broken pieces of shiitake mushroom. Another was U-shaped spaghetti—the curved ends that would normally be cut off so the remaining pasta could look perfectly straight on the shelf. In Japan’s market at the time, “perfect-looking” often mattered as much as “perfectly usable.” MUJI flipped that logic. The mushrooms still tasted the same. The pasta still cooked the same. So why throw it out—or charge more for the illusion?

Visually, MUJI made the argument with restraint: kraft paper, earthy tones, simple typography. The packaging didn’t try to seduce you. It tried to reassure you. It said: this is enough.

MUJI’s advertising carried the same sensibility. One line captured the mood: “Love doesn’t need embellishment.” The message wasn’t that decoration was bad—it was that care shows up in materials, not ornament. If something touches your skin, what it’s made of matters more than what it shouts.

Put it all together and the positioning snapped into focus. MUJI wasn’t trying to be “cheap.” It was trying to be honest. Not anti-quality—anti-waste. Strip out unnecessary packaging, pointless decoration, and empty brand premiums. Spend where it counts. Pass the rest back to the customer.

It was a philosophy you could hold in your hands. But it also set up the question that would follow MUJI for decades: is philosophy enough? Or does a “no-brand” brand eventually live or die on whether the operations are as disciplined as the ideals?

IV. Independence & Early Growth: Spinning Off from Seiyu (1983-1999)

Turning MUJI from a clever private label inside a supermarket chain into a stand-alone company was the moment the philosophy had to prove it could scale.

MUJI began in 1980 as Seiyu’s in-house brand, famously with just 40 products. But the idea kept pulling it toward something bigger: a place where the goods weren’t scattered on someone else’s shelves, but presented as a coherent way of living.

That first leap happened in 1983, when MUJI opened its first directly operated store in Aoyama, Tokyo. Aoyama wasn’t chosen by accident. It’s stylish, design-conscious, and expensive—the kind of neighborhood where you don’t open a store unless you’re making a statement. Takashi Sugimoto designed the space, and he didn’t reach for “new” materials to make it feel premium. The exterior used bricks that had been used in blast furnaces in Kyushu coalmines. Weathered, industrial remnants—repurposed into retail.

In other words, MUJI didn’t just sell the anti-waste philosophy. It built it.

The corporate structure caught up a few years later. In June 1989, Ryohin Keikaku Co., Ltd. was officially established. Then, in March 1990, it acquired the MUJI business from Seiyu. This was the formal break: MUJI wasn’t a side project anymore. Ryohin Keikaku would take responsibility for everything—planning and development, production, distribution, and retail. That end-to-end control would become one of MUJI’s most important weapons: it made consistency possible, even as the company grew.

And grow it did—quickly, and internationally. In 1991, Mujirushi Ryōhin opened its first overseas store in London, using the shortened “MUJI” name for international markets. Hong Kong followed that same year, the beginning of an expansion across Asia that would eventually define the company’s trajectory.

The 1990s, for MUJI, were a rocket ride. From 1990 to 1999, total sales rose from 24.5 billion yen to 106.6 billion yen. Ordinary income climbed even faster, from 25 million yen to 13.3 billion yen. By the end of the decade, the “no-brand” brand had become one of Japan’s defining retail success stories. In 1998, Ryohin Keikaku listed on the second section of the Tokyo Stock Exchange—on its way to the first section in 2001.

But the same forces that powered the ascent also started planting problems inside the machine.

To keep growth humming, MUJI opened large stores that demanded big investment. And big stores need product—lots of it. So MUJI expanded its assortment at speed, doubling the number of items in just four and a half years. With that pace came the predictable tradeoff: quality slipped, and the lineup got crowded. Instead of a tight set of “only what’s needed,” there were more and more products, and fewer obvious heroes that could anchor the brand.

Worse, success bred a kind of autopilot. Leadership began to act as if opening stores was the strategy—as long as there was a new location, sales would follow. Meanwhile competitors were doing what competitors do best: watching carefully, copying quickly, and undercutting on price. Some launched MUJI-like products at prices about 30% lower. MUJI’s uniqueness—its most precious asset—started to blur.

The 1990s ended with MUJI looking unstoppable. The 2000s would start with it discovering just how fragile unstoppable can be.

V. The 2000-2001 Crisis: Near-Death Experience

The new millennium brought MUJI its first real brush with disaster. And it exposed an uncomfortable truth: a philosophy can inspire customers, but it can’t move inventory. Not by itself.

In fiscal 2001, MUJI’s performance suddenly cracked. Ordinary income fell to 5.6 billion yen, and the market’s confidence went with it. The share price slid from around 17,000 yen to roughly 2,800 yen—an 80%+ wipeout. The “unstoppable” story of the 1990s was gone almost overnight.

By the time Tadamitsu Matsui became president and representative director in 2001, the situation was already ugly. The company had posted a 3.8 billion yen deficit the previous year, and it was closing stores around the world. MUJI was no longer a design-led phenomenon. It was a retailer in retreat.

What happened wasn’t one thing—it was a pile-up.

On the outside, the world changed. Japan was still stuck in the long, gray aftermath of the bubble. And new competitors attacked MUJI from both sides: 100-yen shops trained customers to expect shockingly low prices, while Uniqlo offered affordable basics at huge scale. They didn’t just compete with MUJI; in many ways, they used MUJI’s own logic against it.

But the harder truth was internal: MUJI had started to drift. The original concept centered on natural colors, honest materials, and a kind of calm restraint. Then product developers began hearing the same critique: the colors were “too dull.” So they added brighter, more colorful items to chase broader demand. For a moment, it worked—sales bumped up, and employees, hungry for a win, pushed the new merchandise hard.

Then the bump faded. Because MUJI’s customers weren’t coming for “more choices” or “more color.” They were coming for the one thing other stores weren’t offering: a consistent, disciplined simplicity. Once MUJI blurred that, it stopped being a destination. It became just another place that sold stuff.

Matsui later described how competition, especially from other low-cost retailers like Uniqlo, pulled MUJI into undisciplined expansion. New products wandered off concept and didn’t stand out. Store openings and expansions multiplied, but the retail experience—once so coherent—became uneven. The company, in effect, started looking inward: focused on its own routines instead of what the market was doing and why customers chose MUJI in the first place.

Even inside the organization, the cracks showed. Merchandisers and managers leaned on implicit knowledge—things they “just knew”—and didn’t pass it down. Subordinates were left guessing, stores got mixed signals, and inventory piled up unsold. Executives responded with strategies that didn’t translate cleanly to the floor, and the floor paid the price in confusion.

To make matters worse, MUJI tried to fight the new rivals on their terms, mimicking their pricing tactics rather than leaning into what made MUJI worth paying attention to. Matsui found a company that had lost touch with its core customers—followed by the inevitable retail hangover: customer dissatisfaction, excess inventory, and mounting losses.

The lesson landed hard: in retail, a beautiful idea is only as strong as the system that delivers it. Without operational discipline and consistent execution, “no brand” doesn’t read as confidence. It reads as emptiness.

Now the only question was whether MUJI could be saved—and whether Matsui could rebuild it before the market finished the job.

VI. The Matsui Turnaround: Reinventing MUJI (2001-2006)

Tadamitsu Matsui wasn’t an outsider brought in to “fix” MUJI. He was a company man who understood its roots. He started his career at Seiyu in 1973 after graduating from the Department of Physical Education at Tokyo University of Education. He joined Ryohin Keikaku in 1992, and by the late 1990s he was already in the top ranks, holding senior roles including Senior Managing Director and Representative Director.

So when Matsui took the helm in 2001, he didn’t treat MUJI’s crisis as a one-off bad year. He saw a system that had stopped behaving like MUJI. Saving it would take symbolic shock, yes—but more importantly, a rebuild of the operating engine.

His answer was the Management Reform Project 2001: a blunt, company-wide reset. And he opened with a move that was impossible to ignore. Matsui ordered the disposal of 3.8 billion yen worth of unsold clothing inventory.

It was corporate theater, and it was meant to be. The number wasn’t abstract—it was basically the prior year’s loss, made physical. Every employee got the message at the same time: the old way of operating was over. Not “we should consider improving,” but “we are burning the bridge behind us.”

From there, Matsui went after what he believed was MUJI’s real advantage—and its real failure. MUJI didn’t win just because its products looked simple. It won when the whole organization was ruthless about eliminating waste: in procurement, in production, in logistics, in store operations, and especially in inventory. The problem was that MUJI had been running too much on instinct, dependent on the judgment of individual merchandisers and managers. As the company scaled, that “craft” approach turned into inconsistency.

Matsui’s fix was to make repeatability a principle. Cost management and consistency weren’t going to be vibes; they were going to be built into the process. He introduced standardization: a supply-chain management system that could actually surface inefficiencies, store-layout plans that could be replicated, and operational templates that applied MUJI’s minimalist ethic not just to product design, but to how the business ran day to day.

He also tried to drag the organization back toward the customer. Weekly executive meetings stopped being abstract strategy sessions and became places where customer comments and complaints were aired—and resolved. Matsui pushed his leadership team to role-model what they wanted the company to become, even in small rituals. Executives, including the CEO, were required to stand at the headquarters entrance each morning to greet employees—a daily reminder that respect and attentiveness weren’t marketing language; they were supposed to be muscle memory.

The turnaround came faster than most retailers ever get. Matsui’s operational reset—paired with a creative reset—stabilized the brand, cleared the noise, and brought MUJI back to profitability within two years. By 2005, MUJI was posting record results: 140.1 billion yen in sales and 15.6 billion yen in profit.

A major part of that creative reset arrived in 2002, when Kenya Hara took over as MUJI’s art director. The handoff was personal. Ikko Tanaka—the founding creative force behind MUJI’s original concept—called Hara because he wanted to pass him the baton. Hara respected what MUJI had become in Japan; by then it had hundreds of stores and near-universal brand recognition at home. But Hara’s question was different: what would it take for MUJI to make sense globally, as more than a Japanese aesthetic exported overseas?

His answer wasn’t “more minimalism.” It was a deeper idea: emptiness—ku.

“Emptiness is a creative receptacle,” Hara argued. Not emptiness as poverty, or absence, or sterile reduction. Ku is closer to a stance than a style: a readiness to receive, to let the customer complete the meaning. “To offer an empty vessel is to pose a single question and to be wholly ready to accept the huge variety of answers,” Hara said.

That framework helped clarify what MUJI had always been trying to do, even when it drifted. MUJI wasn’t meant to be a bundle of products. It was meant to be a way of thinking: to be confident in a simplicity that doesn’t feel inferior to splendor; to believe that stripping away frills can surpass decoration.

And crucially, Hara believed MUJI shouldn’t overexplain itself. The point wasn’t to write long manifestos on every wall. The point was to communicate through the encounter—so that when people touched the materials, used the objects, and lived with them, they naturally understood what MUJI stood for.

Under Matsui, MUJI recommitted to its core philosophy, but with a sharper edge. Early MUJI had been “cheap for a reason,” proving value by reducing packaging and simplifying production. Now the idea matured: keep stripping away what’s unnecessary, but elevate the quality of what remains. The shift was subtle, but it changed everything. MUJI stopped feeling like a cheap-and-simple brand and started feeling like a brand that chose simplicity because it was the best answer.

The Matsui era leaves a set of lessons that are easy to miss if you only look at the numbers. Philosophy without operational discipline collapses under its own weight. Philosophy with operational discipline scales. And the best turnarounds often don’t come from reinventing a company into something new—they come from forcing it to become what it claimed it was all along.

VII. China Expansion & The Golden Decade (2005-2018)

MUJI’s China story started with a very un-MUJI problem: it didn’t control its own name.

In 1999, when the company tried to enter Mainland China, it ran into a trademark roadblock. A Hong Kong-based company held the rights to “MUJI,” kicking off a long legal fight that dragged on for years. The irony is that MUJI still began building demand in the market anyway. In July 2005, it opened its first official store in Shanghai, even as the trademark dispute was still unresolved. The legal clean entry would come later, in 2007—but by then, the brand had already planted a flag.

The timing couldn’t have been better. China’s emerging middle class was growing fast, and it wanted a particular kind of modernity: refined, international, and credible. Local brands weren’t yet seen as aspirational. Foreign brands were. MUJI’s Japanese minimalism—clean, quiet, and “designed” without being showy—hit like a blueprint for the life people wanted to build.

Years later, Nobuo Domae, president and representative director of Muji, put it plainly to China Daily: "China, now the biggest overseas market for Muji in terms of both sales revenue and profit, is an important market for Muji's global business."

Once MUJI found product-market fit, the expansion became a chain reaction. Store counts went from a handful, to dozens, to hundreds. MUJI showed up in the most prestigious shopping centers in Shanghai and Beijing, then kept going. In the eyes of many Chinese consumers, it wasn’t just a place to buy socks or storage bins. It was access to Japanese quality and taste—attainable, but still a step above everyday retail. And yes, prices were within reach, but they were also noticeably higher than back in Japan.

From roughly 2005 to 2018, this became MUJI’s golden decade. Global revenue more than doubled. Investors bought the story too: between 2013 and 2018, the company’s stock roughly tripled in value, riding the belief that China would keep compounding.

But baked into that success was a contradiction MUJI couldn’t outrun. MUJI was born as an anti-status brand—“cheap for a reason,” anti-waste, anti-luxury. In China, it was increasingly functioning like a premium lifestyle label. The same everyday goods sold at home were positioned as affordable luxury abroad, often at multiples of their Japanese price.

For a while, that tension didn’t matter. Chinese consumers admired foreign brands, and serious local challengers hadn’t yet closed the gap in design and merchandising. But it was always a temporary advantage—one that would eventually expire.

VIII. The Perfect Storm: 2018-2020 Challenges

The reckoning arrived fast. After more than a decade of momentum, MUJI’s China business hit an inflection point: in 2018, sales in China declined for the first time.

One reason was hiding in plain sight—on the price tags. The everyday-Japan promise that made MUJI feel so approachable started to break when translated into China pricing. Items that were meant to be ordinary suddenly looked like luxuries: mugs priced at 80 RMB, stools priced as high as 1,000 RMB. MUJI’s approach of taking the Japanese yen price and dividing by 10 created a jarring outcome in practice—many products ended up costing roughly double what they did back home. For a brand built on “no excess,” that gap wasn’t just a financial problem. It was an identity problem.

And then the copycats arrived—at scale.

The most formidable was Miniso. Founded in China in 2013 by entrepreneur Ye Guofu together with Japanese designer Miyake Junya, Miniso opened its first store and quickly positioned itself as design-forward and aggressively affordable: a physical retail chain where you could grab everything from makeup to keyboards at prices that felt closer to a dollar store than a lifestyle boutique. The company has presented itself as “Japan-based,” even claiming it was founded in Tokyo. But most of its products—roughly 80% to 85%, according to reporting—are manufactured in China, and the company operates out of Guangzhou.

Miniso didn’t just borrow MUJI’s look. It used MUJI’s simplicity against it. By 2018, Miniso had grown to about 3,400 stores worldwide. By the time it went public on the New York Stock Exchange in October 2020, it had expanded further—more than 4,200 outlets across over 80 countries and territories—and framed the listing as fuel for even more growth. Critics called it a copycat of Japanese retailers like Uniqlo and MUJI. Consumers, meanwhile, kept walking in.

And Miniso wasn’t alone. As MUJI started losing ground, a wave of “Chinese apprentices” surged into the same lane: NetEase launched its strict selection offering in April 2016 with the promise that “a good life is not so expensive.” Other players—Taobao Xin Xuan, Xiaomi Youpin, NOME, OCE, and more—pushed the same message into more cities, more malls, more neighborhoods. MUJI’s minimalist aesthetic had created a category. China’s retail machine was now scaling it.

Ye Guofu, asked directly about MUJI, twisted the knife with a simple claim: MINISO and MUJI used the same suppliers. The difference, he argued, was price. If slippers from the same supplier sold for 20 yuan at MINISO, they might cost 100 yuan at MUJI. His punchline: “MINISO is MUJI at a fairer price.”

That line landed because it exposed MUJI’s core vulnerability. MUJI’s products were intentionally simple, which made them easy to replicate. Its visual language was restrained, which made it easier for knockoffs to achieve “close enough” parity. And its pricing in China left a wide, tempting gap for competitors to exploit.

Then Covid hit—and the stress test went global.

On July 10, 2020, MUJI’s U.S. arm filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy protection. Court filings described more than 200 creditors and over $50 million in liabilities, and the company listed total debt of $64 million at the time of the filing. The operator pointed to the pandemic shutdowns as the immediate trigger, but the fault lines were already there: high rents, high operating costs, and a business that had been running at a loss for the past three fiscal years. Ryohin Keikaku said MUJI U.S.A. had been working to improve sales and renegotiate rent before the pandemic, but lockdowns erased the runway.

The U.S. bankruptcy was a visible embarrassment. But strategically, the China challenges mattered more. China wasn’t just another overseas market—it was the growth engine. And by 2018, MUJI had entered a new era where it had to rethink its international positioning and pricing, or watch the category it created get captured by faster, cheaper imitators.

IX. The "Second Founding": New Strategy Under Nobuo Domae (2021-Present)

MUJI’s next reinvention needed a different kind of leader—someone who could keep the philosophy intact, but rebuild the machine for a harsher, faster global retail world. The person chosen brought a résumé that reads less like “design retail” and more like “systems.”

Nobuo Domae came to Ryohin Keikaku after a career that mixed strategy and execution. He’d worked as a consultant at McKinsey & Company, then spent more than a decade at Fast Retailing, Uniqlo’s parent, rising to Executive Vice-President. At Uniqlo, he helped push the well-known “ABC plan,” a supply-chain initiative credited with improving how the company produced and moved product. He also brought a technical background—both a bachelor’s and a master’s degree in electrical and electronic engineering from the University of Tokyo.

In September 2021, after Domae was appointed president, he declared what the company called a “second founding.” This wasn’t framed as a tweak or a turnaround. It was a new phase, with a long horizon: a 2030 vision of a “community-based business model centering on independent management of stores,” and a redefined purpose—“to contribute to the creation of ‘truthful and sustainable life for all.’” Over the three years after he became president, sales rose 46%.

The strategy shift was not one-dimensional. It was a set of bets designed to make MUJI feel local again—without losing what made it MUJI.

First came aggressive localization in China, the market that had gone from golden goose to pressure cooker. Domae was blunt about how the old model worked: MUJI used to develop and design in Japan, then sell the same assortment globally. But China, he argued, could no longer be treated as just another overseas destination for Japan-made goods. “Now, we are making more and more products that are produced, manufactured and designed here in China,” he said, emphasizing that China is MUJI’s only overseas market with a closed-loop industrial chain.

That shift wasn’t cosmetic. The company said that roughly 70% of its daily-use products in China were being developed and designed for the Chinese market—up from around 60% the prior year—and that more than 5,000 items had been designed there so far. Internally, MUJI also pushed supply-chain changes to support pricing: increasing order volumes with Chinese factories, reducing the number of suppliers to strengthen bargaining power, and tightening the loop from design to sales. The goal was simple: cut tariffs and logistics costs, and get the shelf price back to something that felt like MUJI—not a luxury import.

You can see it in one of the most MUJI products imaginable: slippers. Their price in China fell from 99 RMB in 2015 to about 30 to 50 RMB in 2024—more than a 50% reduction.

Second came a new store format aimed at restoring MUJI’s everyday accessibility: MUJI 500. At the beginning of 2025, the company officially announced this low-price concept. The “500” signaled a 500-yen anchor—roughly 23 to 25 RMB—and the idea that a large share of items would cluster around that everyday price point. It was MUJI stepping directly into the arena it had helped create: Japanese-style miscellaneous goods, but now competing head-on with value-focused players by making affordability part of the format, not just a promise.

The bet behind both moves was the same: local products that solve local needs. The company said that more than 70% of MUJI’s lifestyle and food products in China were now developed specifically for the market. “Locally developed, locally sourced, and locally marketed” didn’t just improve relevance; it also reduced exposure to geopolitics by making MUJI feel less like a foreign import and more like a participant in the domestic ecosystem.

The early results were encouraging. MUJI China posted revenue growth in fiscal years 2022 through 2024 of 9.6%, 22.4%, and 11.5%. From September through December 2024, same-store sales were up year-on-year for four straight months. Over the 12 months from September 2023 to August 2024, MUJI China revenue reached RMB 5.5 billion (about $760 million), nearly 20% of global revenue.

Then, in November 2024, leadership passed to Satoshi Shimizu. In the company’s integrated report released afterward, Shimizu—newly in office—outlined concrete measures to pursue global growth, building on what MUJI had put in motion during the “Second Founding.”

Alongside that handoff, Ryohin Keikaku also laid out a new medium-term plan. The headline target: ¥880 billion in revenue by 2027. Overseas markets were positioned as the main growth engine, with continued store expansion in China and Southeast Asia. The plan called for overseas revenue to grow to ¥380 billion, and for the company to add stores at a net pace of about 60 per year, including 30 new stores annually in mainland China.

The ambition wasn’t just more stores—it was sustained momentum. The company projected average annual growth of more than 10% in both revenue and operating profit through August 2027. And it was coming off a strong base: for the fiscal year ending August 2024, MUJI’s consolidated net profit reached a record 41.5 billion yen.

X. Bull Case, Bear Case & Competitive Analysis

The Bull Case

If you want to be optimistic about MUJI from here, the starting point is simple: the business has momentum again.

In 2024, Ryohin Keikaku reported revenue of ¥661.68 billion, up from ¥581.41 billion the year before. Earnings came in at ¥41.57 billion, a sharp jump year-on-year. Operating profit also rose strongly compared to the prior year. The market noticed: the stock closed at ¥2,903.5, up meaningfully year-to-date, and it was up even more over the past 12 months—clear evidence that investors believed the “second founding” was more than a slogan.

China, in particular, looks like it’s stabilizing and re-accelerating. The turnaround appears real: MUJI’s sales and profits reached an all-time high, and growth in China outpaced other overseas markets, making it one of the company’s biggest contributors globally.

And then there’s the thing that’s always been MUJI’s quiet superpower: philosophy as moat. Kenya Hara’s idea of “emptiness” is hard to counterfeit in a way that feels authentic. Competitors can copy the surface—neutral colors, clean typography, plain packaging—but MUJI’s best work doesn’t feel like “minimalism as an aesthetic.” It feels like a point of view about how to live. That depth is why the brand can remain desirable even when the product categories are, in theory, commoditized.

The Bear Case

The most obvious risk is also the most persistent one: imitation isn’t a side issue, it’s the category. The copycat problem hasn’t gone away. It’s intensified.

Miniso is the best example. It now operates at massive scale globally, with thousands of stores across dozens of countries and billions in annual revenue. MUJI, by comparison, is smaller in store count and competes in many of the same “everyday goods” lanes where customers can make decisions in seconds: Do I like it? Do I need it? Is it cheap enough?

That leads to MUJI’s structural vulnerability: the “no-brand” identity creates permanent pricing pressure. If you’re telling customers there’s no brand premium, it becomes harder to justify a higher price—especially in markets where the same silhouette can be found down the hall for less. MUJI has responded with price cuts, but price cuts squeeze margins. And even after cutting, the pricing paradox doesn’t magically disappear.

There’s also geographic concentration risk. China is now close to one-fifth of global revenue and an even bigger share of overseas profit. That’s great when China is working. It’s dangerous if consumer sentiment shifts, competitive pressure intensifies further, or geopolitical tensions complicate the operating environment. When your biggest growth engine is also your biggest risk factor, you don’t get to relax.

Porter's Five Forces Analysis

Threat of New Entrants: HIGH. Lifestyle retail has low barriers to entry, and MUJI’s restrained aesthetic is easy to imitate.

Bargaining Power of Suppliers: LOW. MUJI’s scale helps. The high localization rate in China shows it can source efficiently and structure its supply base to support cost control.

Bargaining Power of Buyers: MODERATE TO HIGH. Customers have endless alternatives and can switch quickly—often without feeling like they’re giving up much.

Threat of Substitutes: HIGH. E-commerce, discount chains, and specialist brands all compete for the same spend.

Competitive Rivalry: HIGH. MUJI is fighting on multiple fronts: Miniso in miscellany, Uniqlo in basics, IKEA in home, plus strong local players in every market.

Hamilton Helmer's 7 Powers Analysis

Scale Economies: Moderate. MUJI benefits from purchasing and production scale, but it doesn’t have the overwhelming advantage of a Walmart or Amazon.

Network Effects: Minimal. This is retail, not a platform.

Counter-Positioning: Strong in theory. MUJI’s “no-brand” philosophy and vertically integrated approach are hard for traditional, logo-driven incumbents to mimic without undermining themselves. The catch: newer players like Miniso were born into this playbook and don’t have legacy brand structures to protect.

Switching Costs: Low. There’s no lock-in.

Branding: Paradoxically strong. MUJI’s “no-brand” stance has become a brand in itself, with real equity and emotional pull.

Cornered Resource: Real but fragile. Kenya Hara’s leadership and the institutional knowledge of “what feels like MUJI” matter. But these are cultural advantages, not patents.

Process Power: Improving. Matsui’s reforms built operational discipline; Domae’s supply-chain focus pushed it further. The question is whether MUJI can keep translating that into consistent execution across markets.

Key Metrics to Track

For anyone watching MUJI’s next chapter, two signals matter more than almost anything else:

-

Same-Store Sales Growth (Comparable Store Sales): This is the clearest indicator of brand health and pricing power. Recent momentum is promising—same-store sales rose year-on-year for four straight months from September through December 2024—but it has to keep going. If comp-store sales turn negative, store openings can mask the problem for a while, but they can’t fix it.

-

China Revenue Growth and Localization Rate: With China near 20% of global revenue and positioned as the primary overseas growth engine, localization isn’t optional—it’s the strategy. A roughly 70% localization rate for daily products is meaningful progress. The real test is whether MUJI can sustain competitive shelf prices through local design and sourcing without giving back profitability.

XI. The "No-Brand" Brand: Myth vs. Reality

Myth: MUJI doesn't have a brand.

Reality: MUJI has one of the most distinctive brands in retail. “No-brand” was never an absence of identity—it was the identity. The earthy palette, the kraft-paper packaging, the matter-of-fact typography, the calm grid of the store layouts: these aren’t accidents. They’re recognizable signatures. MUJI’s real trick was turning anti-branding into a brand system so consistent you can spot it from across a mall.

Myth: MUJI products are cheap.

Reality: Outside Japan, MUJI often isn’t cheap at all. In many markets, items carry clear premiums versus local alternatives—and sometimes even versus MUJI’s own domestic prices in Japan. The brand leans on perceived Japanese quality, the appeal of minimalist design, and lifestyle aspiration. That original “cheap for a reason” logic still lives in the origin story, but it hasn’t consistently translated to international pricing.

Myth: MUJI's simplicity is easy to copy.

Reality: The surface is easy to copy—Miniso and a long list of competitors have demonstrated that. What’s harder to replicate is the underlying philosophy: Kenya Hara’s idea of “emptiness,” the accumulated know-how of what “feels like MUJI,” and the sustainability-minded approach that’s been embedded since the beginning. The open question is whether that depth becomes a durable advantage, or whether it’s too intangible to protect margins in a world of cheaper lookalikes.

Myth: MUJI's crisis was caused by the pandemic.

Reality: The pandemic was the match, not the gasoline. MUJI’s U.S. bankruptcy was triggered by Covid-era shutdowns, but the business had reportedly been losing money for three straight fiscal years before COVID hit. And in China, the same-store sales slowdown began around 2018, before pandemic disruptions. The crisis was about fundamentals—pricing, positioning, and competition—with Covid accelerating the consequences.

Myth: MUJI is purely a retail company.

Reality: MUJI has been stretching into something closer to a lifestyle infrastructure. In Kamogawa, Chiba Prefecture, it turned a 100-year-old house into MUJI BASE, a medium-term stay where guests can experience local farming and community life. In Kani, Gifu Prefecture, a MUJI store doubles as a public library. The company also operates hotels, restaurants, housing services, and campsite facilities. It’s diversification, yes—but it’s also brand reinforcement: MUJI isn’t just selling objects. It’s trying to make its idea of everyday life feel inhabitable.

XII. Conclusion: Lessons from the Anti-Brand

MUJI’s 44-year journey leaves a handful of lessons that feel surprisingly durable—whether you’re an investor, an operator, or just someone who’s watched a lot of retail stories end badly.

First: philosophy can be strategy, but only if the operating system can carry it. MUJI began as a real critique of consumer capitalism, turned into products: fewer frills, less waste, “cheap for a reason.” But the 2001 crisis showed the hard limit of ideals. Without disciplined inventory, consistent merchandising, and repeatable processes, philosophy becomes a slogan. Matsui’s turnaround worked because it didn’t just restore the “MUJI feeling.” It rebuilt MUJI as a machine that could deliver that feeling at scale, reliably, store after store.

Second: global expansion isn’t translation—it’s adaptation. MUJI’s struggles in China and the U.S. weren’t just bad luck or bad timing. They revealed what happens when you assume what works in Japan will work everywhere, with only minor tweaks. The newer approach—developing and designing a majority of everyday products locally in China, rolling out lower-priced store formats like MUJI 500, building categories around local needs—signals something deeper: MUJI is finally trying to earn relevance market by market, instead of exporting a finished worldview and hoping customers will adopt it.

Third: the most defensible moat in a copycat category might be depth. Competitors can borrow the surface: neutral colors, plain packaging, simple forms. What’s harder to reproduce is what sits underneath—decades of design thinking, institutional memory of what “feels like MUJI,” and the sustainability and waste-reduction ethos that’s been there since the beginning. Kenya Hara’s idea of “emptiness” matters here. It’s not an aesthetic trick; it’s a stance. And stances are harder to counterfeit than silhouettes.

Fourth: brand equity can survive repositioning—if you pivot without breaking the core. MUJI has reinvented itself more than once: from Seiyu private label to standalone retailer, from domestic phenomenon to global chain, from premium foreign brand in China to trying to be value-competitive again. Each shift could have shattered trust. But when MUJI gets it right, the brand doesn’t feel inconsistent—it feels resilient, like the same idea expressed under new constraints.

Ryohin Keikaku’s consolidated sales hit a record ¥661.6 billion (about $4.4 billion) for the fiscal year ending August 2024, and the stock has reflected the regained momentum. But the big questions still hang in the air. Can MUJI keep prices compelling without collapsing margins in a world full of “good enough” substitutes? Can China stay a growth engine rather than a recurring stress test? And can “emptiness” function as a true competitive advantage in global retail—one of the most unforgiving arenas there is?

MUJI began as a businessman-poet’s rebellion against bubble-era consumerism. Somehow, it became a global lifestyle brand. The “no-brand” turned into one of the most recognizable brands in retail. The anti-consumption concept grew into a worldwide store network selling everyday goods at enormous scale. There’s poetry in that paradox. And maybe that paradox—the ability to sell less, louder—is exactly what makes MUJI worth studying.

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music