Shimano Inc.: The Quiet Giant That Gears the World

I. Introduction: The Invisible Empire Behind Every Ride

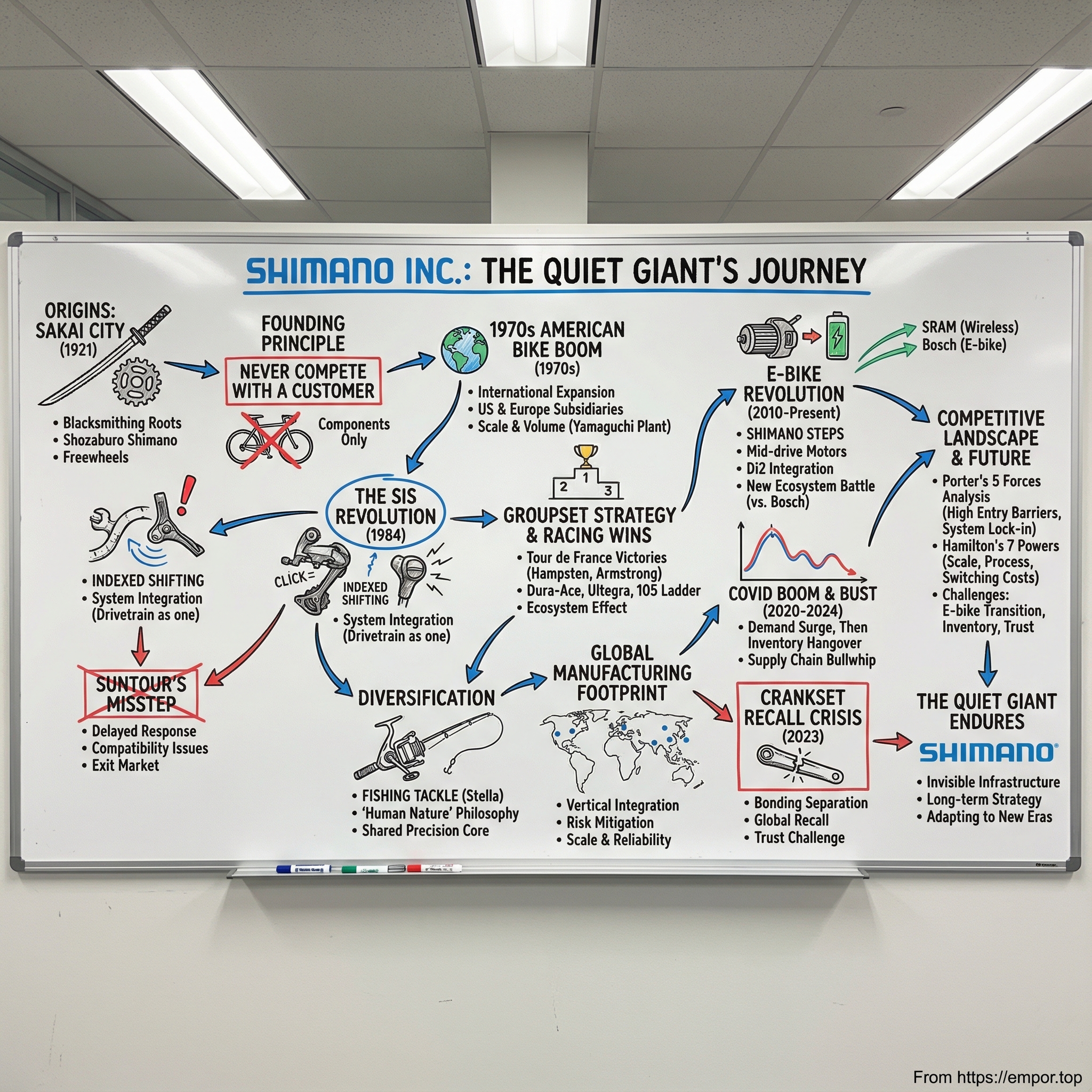

Picture yourself on a street corner in almost any big city—Tokyo, Amsterdam, Copenhagen, New York, São Paulo—and just watch the bikes roll by. Count a hundred of them. Odds are that somewhere between seventy and eighty-five are running on the same set of parts: the gears that snap cleanly into place, the brakes that bite when they’re supposed to, the drivetrain that turns leg power into motion with almost no drama.

That company is Shimano Inc.—a Japanese multinational based in Sakai, in Osaka Prefecture. Sakai isn’t just another industrial city. It’s a place with deep blacksmithing roots, known for centuries for forging swords and gun barrels. Shimano was born out of that culture of precision manufacturing, and it still carries it today. The company is headquartered there, operates through 32 consolidated and 11 unconsolidated subsidiaries, and builds much of its product through major manufacturing hubs in places like Kunshan in China, plus Malaysia and Singapore.

And yet, most people barely notice Shimano.

Buy a Trek, Specialized, Giant, or Cannondale and the name on the frame is what you talk about. But if you look closer—on the crankset, the derailleur, the brake lever—you’ll see the little Shimano mark stamped into the metal. Not the hero of the story, not the brand you brag about, but the underlying machinery that makes the whole ride work.

In the mid-to-high end of bike components, Shimano is often reported to hold around 70% share. In electronic shifting, Shimano and SRAM are the giants, with Italy’s Campagnolo a distant third. And when you zoom out to the full bicycle component universe, some estimates put Shimano’s share as high as 85% by value—dominance on a scale that’s almost hard to reconcile with how quiet the brand feels.

So how did a small ironworks in Japan’s sword-making capital end up influencing what “good shifting” even means for most of the world?

That’s the story here: strategic patience, relentless engineering, and a competitor’s misstep so consequential it effectively handed Shimano the keys to the market. It’s also a story that doesn’t stop at triumph. In the last few years, Shimano has faced a pandemic-driven boom followed by a painful hangover, and a major recall that forced the company to confront the unglamorous reality of scale: when you make parts for the world, problems scale too. And now the e-bike era is reshaping the industry’s center of gravity—raising the question of whether Shimano’s century-old playbook still works when the drivetrain includes a motor.

As we go, a few themes keep surfacing: vertical integration as a kind of operating system; the guiding rule to never compete with your customer; a systems-level approach to products long before anyone used that language; and the rare ability to control an ecosystem without ever owning the end product.

II. Origins: Sakai City and the Blacksmithing Heritage (1921–1945)

In 1921, a 27-year-old machinist named Shozaburo Shimano made a choice that looked small on paper and weirdly specific in practice. While plenty of Japanese industry was chasing bigger, louder opportunities—textiles, steel, shipbuilding—Shimano decided to build one of the fussiest, most failure-intolerant parts on a bicycle: the freewheel. That’s the ratcheting mechanism that lets the rear wheel keep turning even when you stop pedaling.

The setting wasn’t a coincidence. Shimano opened up in Sakai City, just south of Osaka, and he named the shop Shimano Iron Works (島野鐵工所). Sakai had been Japan’s metalworking capital for centuries. This was a place that had produced katana for feudal lords and gun barrels for the armies that unified the country. As Japan modernized, that same craft flowed into kitchen knives, industrial components—and, increasingly, bicycle parts.

And freewheels were the deep end of the pool. In the 1920s, if you wanted to prove you could machine with real precision, you didn’t start with the easy stuff. A freewheel isn’t just a gear. It’s a compact, high-tolerance assembly of pawls, springs, and ratchets that has to engage cleanly, release instantly, and do it over and over again without slipping. Starting there broadcast Shozaburo’s intent: Shimano wasn’t going to win by being the cheapest. It was going to win by being the most exact.

The early years were, by necessity, modest. Japan’s bicycle market was still small compared to Europe’s, and global trade had been shaken up in the wake of World War I. But Shozaburo was betting on the long arc: bicycles weren’t a fad. They were infrastructure. If anything, the world was only beginning to need them.

By 1931, Shimano began moving beyond freewheels into a broader lineup of bicycle components. Each step built on the same core competency—precision machining—and the company’s direction started to become visible even then: don’t just make parts, make the pieces that need to work together, and make them so consistently that “compatibility” becomes something customers assume.

In 1940, the business was formally incorporated as Shimano Iron Works, Ltd., with Shozaburo as its first president. By then it had grown to roughly 300 employees—real scale for a component maker. And then the Pacific War arrived, and normal industrial life in Japan effectively stopped.

Shimano’s wartime period is thinly described in its official history. Like many manufacturers, it likely shifted into work tied to the war effort. What matters for this story is the outcome: when peace returned in 1945, Shimano was still standing. The tooling, the know-how, and the culture of precision had survived.

Shozaburo would lead the company until his death in 1958, and in that time he set the foundation for what Shimano would become. One principle, in particular, was less a slogan than a line you didn’t cross: Shimano would make components, not complete bicycles. That single constraint sounds limiting—until you realize it positioned Shimano to become indispensable to everyone else.

III. The Founding Principle: "Never Compete With a Customer"

If you’re looking for the single decision that explains why Shimano could become enormous without ever becoming famous, it’s this one. Sometime in the company’s early decades, Shimano faced the obvious question: why not build complete bicycles?

On paper, it made all the sense in the world. Shimano already had precision manufacturing, assembly know-how, and growing credibility. Complete bikes offered higher margins than selling parts one at a time. And plenty of big names in the cycling world had gone the other direction—owning more of the stack, pushing all the way to the final product.

Shozaburo Shimano’s answer was blunt: “Never ever compete with a customer.”

That line is doing a lot of work.

Because once you’re selling finished bicycles, every bike brand stops being a customer and starts being an enemy. The moment Shimano put its name on the downtube, it would have forced every manufacturer—Trek, Giant, Specialized, Cannondale, plus hundreds of smaller brands—into an uncomfortable choice: buy critical components from a direct competitor, or go elsewhere. Most would go elsewhere, even if “elsewhere” meant worse parts.

And Shozaburo also seemed to understand something structural about bikes: the market would never converge into one “best” bicycle. It would splinter by geography, use case, and budget. Racing bikes, city commuters, kids’ bikes, touring rigs—these aren’t variations on the same thing. They’re different products with different buyers and different economics.

But components travel. A derailleur that’s dependable on a Japanese commuter is still dependable on a European road bike. If Shimano stayed upstream—making the things every bike needs, regardless of what kind of bike it is—then Shimano could sell to everyone, without picking winners.

This is where Shimano and its main Japanese rival, SunTour, started to separate. SunTour, like Shimano, didn’t sell complete bicycles. But it also didn’t fully control a complete component system. To offer a full “SunTour-branded” setup, it teamed up with other makers—Sugino for cranksets, Dia-Compe for brakes. The problem with that kind of production agreement is simple: you don’t own the roadmap. If a partner doesn’t upgrade or redesign its part, you can’t force the system forward—and you can’t ensure everything evolves together.

Shimano’s commitment to components-only became even more durable as the company transitioned from founder-led to family-led. Shozaburo eventually handed management to his three sons—Shozo, Yoshizo, and Keizo—who kept the same boundary in place: we will power the bike industry, not compete with it. The company remained heavily influenced by the Shimano family, with substantial ownership and board representation.

In practical terms, this principle shaped how Shimano worked with the world. When a company like Trek or Specialized designed a new frame, Shimano didn’t show up as a rival brand trying to steal the customer. Shimano showed up as a collaborator—an engineering partner making sure the drivetrain, brakes, and controls fit, functioned, and shipped at scale.

And that’s the moat. It’s hard enough for a new component entrant to convince manufacturers to switch suppliers. It’s even harder when manufacturers have to worry that today’s supplier becomes tomorrow’s competitor. Shimano’s long, consistent refusal to cross that line bought it something rare in industrial markets: trust that compounds over decades.

IV. The 1970s American Bike Boom and International Expansion

The 1970s were the decade Shimano stopped being “a great Japanese component maker” and started becoming something much bigger: a global supplier that could show up anywhere demand spiked and reliably fill it.

The trigger wasn’t a cycling trend. It was macroeconomics. The oil crisis hit in 1973, gasoline got expensive, and suddenly the bicycle looked less like a toy and more like a practical alternative. At the same time, the environmental movement was finding its voice, and the idea of riding a bike felt newly aligned with where the culture was going. Americans who hadn’t pedaled since childhood flooded back into bike shops—for commuting, for recreation, for fitness. The U.S. market, quiet for decades, woke up fast.

And the industry wasn’t ready.

The established European component makers—brands like Campagnolo, Simplex, and Huret—made beautiful gear, but they were built for a world where growth came in increments. When orders started doubling and tripling, they couldn’t scale production quickly enough. Their manufacturing was craft-oriented and capacity-constrained, and the American boom exposed that bottleneck in real time.

Shimano and SunTour stepped right into the gap.

Postwar Japanese manufacturing was optimized for consistency and volume. Shimano could produce at factory scale, and it could do it at price points European suppliers struggled to match. The moment the market demanded “a lot more, right now,” Shimano’s operating model became a competitive weapon.

What’s easy to miss is that Shimano had started laying the groundwork before the boom arrived. In January 1965, the company established Shimano American Corporation in New York—its early beachhead into the U.S. That same year it also pushed into Europe. So when demand surged, Shimano wasn’t scrambling to figure out how to export. The channels were already forming.

Then, in 1970, Shimano went even harder on capacity. It built what was then the largest bicycle plant in the world, in Yamaguchi Prefecture, Japan. It was a statement of intent: Shimano wasn’t planning to simply serve Japan, or even to merely participate globally. It was planning to manufacture for a world-scale bicycle market.

Later in the decade, Shimano began hiring engineers with a specific mission: make the components feel like they belonged together. Not just technically compatible, but visually unified and performance-aligned—early moves toward what would become Shimano’s defining product concept: integrated component systems.

In 1972, Shimano opened Shimano (Europa) GmbH in Düsseldorf—with just two employees. Two. That tiny start tells you a lot about how Shimano expanded: methodically, locally, and with a long view. It wasn’t chasing quick wins. It was building presence that would last.

That same year, Shimano’s shares began trading on the Osaka Securities Exchange, and in 1973 it was listed on the Tokyo Stock Exchange. Access to public markets gave Shimano more fuel for expansion—more plants, more R&D, more inventory, more reach.

By the end of the 1970s, the industry’s balance had shifted. Below the premium tier, Shimano and SunTour were becoming default choices—first because they could deliver at scale, then increasingly because they could deliver at scale without sacrificing quality.

And in the process, Shimano was also revealing something deeper: a very particular philosophy about innovation and market entry—one that ran against conventional wisdom, and that would soon turn a strong rival into a casualty.

V. The SIS Revolution: Destroying SunTour (1984–1990s)

Every industry has a moment when “before” and “after” become obvious. In bicycle components, that moment was 1984—and the four letters Shimano put on the box: SIS, the Shimano Index System.

To understand why it mattered, you have to remember what shifting used to feel like. Derailleur bikes worked, but they were fiddly. You didn’t so much shift into a gear as hunt for it. Riders learned to listen for chain rub, nudge the lever a little, then nudge it back, trying to land on the narrow sweet spot where everything lined up. Smooth shifting was a skill, and it demanded attention.

Shimano’s engineers took that entire experience and asked: what if shifting wasn’t a feel thing at all? What if it was precise—mechanically predetermined—so that each gear had a fixed derailleur position, triggered by a lever that rotated a specific amount and clicked into place?

That was indexed shifting. And it changed what cyclists expected a drivetrain to do.

But SIS wasn’t just a clever shifter. It was a system. For SIS to work reliably, the derailleur, the shifter, the cable, the freehub, and the cassette spacing all had to match. The magic wasn’t the click; it was the integration behind the click. Pick SIS, and you weren’t just buying a part—you were buying into Shimano’s ecosystem, because mixing and matching became much harder without sacrificing the very reliability SIS promised.

And that’s where the competitive earthquake hit.

SunTour was Shimano’s great Japanese rival—innovative, respected, and, for a time, the name you saw everywhere. But SIS forced a fork in the road: either redesign around indexing, or stick with what you’re already great at.

SunTour chose wrong.

In 1985, Shimano pushed indexed shifting into the market hard. SunTour underestimated how fast indexing would become table stakes and delayed its own response until 1986—only a year, but a disastrous one. In consumer products, a year is enough time for manufacturers to standardize, for mechanics to learn new setups, and for buyers to form a new definition of “good.”

Worse, SunTour tried to graft indexing onto its existing world—unevenly spaced freewheels and legacy designs—while Shimano approached SIS as a clean-sheet system. Shimano designed the lever, derailleur, chain, and sprockets to work together from the start. SunTour was trying to make the future compatible with the past. Shimano was building the future.

This is the innovator’s dilemma, cycling edition. SunTour’s friction-shifting derailleurs were excellent. But to win in indexing, they couldn’t just tweak. They had to restart, wiping out years of accumulated advantage. Shimano didn’t have to protect an incumbent design the same way. It could commit fully.

Then Shimano turned commitment into capability. It expanded its research and development staff to around 200 employees and used that muscle to end its reliance on component marketing agreements—bringing more of the parts lineup in-house: hubs, pedals, brakes, the full range. SunTour, by comparison, continued with an R&D team of roughly 20. By the time this battle was playing out, Shimano had scaled to around 2,000 employees, while SunTour was closer to 350.

The resource gap didn’t just predict the outcome. It ensured it.

SunTour also boxed itself in with pricing. Instead of charging what the market would bear, it priced products as “cost plus a little.” The result was brutal: a SunTour derailleur at around $10 sitting next to a comparable Shimano product at about $20 and Campagnolo at roughly $40. Low prices helped sales in the moment, but they starved the company of the very thing it needed most: budget to fund the next platform shift. They also cemented a perception that SunTour was the value brand. Later, when SunTour tried to move upmarket with premium products like Superbe Pro, customers struggled to believe it.

And then the final door closed. When SunTour’s key derailleur patents expired in the 1980s—including its famous slant-parallelogram design—Shimano and others could copy the idea freely. Shimano adopted the design and improved it, now backed by a system-level approach and stronger execution. By the early 1990s, SunTour had largely disappeared from showroom bikes.

SunTour had been the most important Japanese component maker up through the late 1980s. In 1988, it was bought by SR (Sakae Ringyo, itself later bought by Mori Industries). After that, whatever remained of SunTour’s dominance slipped away.

What SIS did, ultimately, was redefine the category. It turned shifting from a rider skill into a product guarantee—and it made “the drivetrain” feel like one integrated machine. By the end of the 1980s, SunTour had lost the technological and commercial battle, and Shimano had become the largest manufacturer of bicycle components in the world.

VI. The Groupset Strategy and Racing Victories

With SunTour fading from the picture, Shimano’s next mountain to climb wasn’t another Japanese upstart. It was Campagnolo—the storied Italian house that had become synonymous with pro racing prestige, and had equipped most Tour de France winners going back to the 1960s.

Shimano understood something simple and brutally effective about the bike industry: pro racing is the loudest marketing channel it has. Recreational riders may not know who machined their derailleur cage, but they absolutely know what the winners rode. If Shimano could win on the biggest stages, it could rewrite what “serious” equipment meant.

The first real crack in the old order came in 1988 at the Giro d’Italia. Andrew Hampsten, an American climber, rode Shimano to its first Grand Tour victory—through the now-legendary blizzard over the Gavia Pass. Hampsten became the first (and still only) American to win the Giro, and he did it on Shimano.

By then, Shimano had already been building something more ambitious than a great derailleur. The Dura-Ace groupset Hampsten rode helped define what top-end performance could feel like: crisp shifting, unified ergonomics, and parts designed to work as one machine. And once Shimano had a foothold in elite racing, the wins started to compound.

In 1999, Lance Armstrong won the Tour de France on a Trek equipped with Shimano Dura-Ace—the first time Shimano components had been used to win the Maillot Jaune. Then in 2002, Shimano hit a milestone that would’ve sounded impossible a decade earlier: Dura-Ace-equipped bikes won the Tour de France, the Giro d’Italia, and the Vuelta a España in the same year—the first time Shimano had swept all three Grand Tours.

Underneath those results was Shimano’s real commercial weapon: the groupset.

Instead of selling “a derailleur” or “a brake,” Shimano sold a complete, matched system—shifters, derailleurs, brakes, chain, cassette, crankset—engineered as a unit and marketed as a unit. Over time, the names of those systems became a kind of universal language for bike quality. Dura-Ace at the top, then Ultegra, 105, Tiagra, Sora, Claris, and Tourney.

That ladder did a few things at once. It let Shimano participate in every price tier of cycling. It created a clean upgrade path, where the tech and design cues from the top filtered down and made the next rung feel like progress. And it strengthened the ecosystem effect SIS had introduced: once a bike was spec’d around a Shimano groupset, mixing and matching with other brands could quickly become a frustrating compatibility puzzle.

By the 2017 Tour de France, Shimano’s presence had become overwhelming: teams using Shimano Dura-Ace won every stage and every jersey, and most of the peloton was on Shimano.

And the company kept stacking proof points. In 2022, riders using Shimano’s 12-speed wireless DURA-ACE won all three Grand Tours—Jonas Vingegaard at the Tour de France, Jai Hindley at the Giro d’Italia, and Remco Evenepoel at the Vuelta a España—plus a world championship.

At that point, the flywheel was obvious. Racing credibility fed consumer demand. Consumer demand fed OEM spec decisions. OEM spec decisions reinforced Shimano as the default. When riders saw Shimano on the biggest podiums, the buying decision started to feel less like a choice and more like a conclusion.

VII. Diversification: Fishing Tackle and the "Human Nature" Philosophy

By the 1990s, Shimano’s dominance in bicycle components was no longer a thesis. It was reality. And that raised the next, very practical question for management: what do you do with a business that’s throwing off cash and already winning its core market?

Shimano’s answer didn’t come from another type of bike. It came from the water.

The company had started manufacturing fishing tackle back in 1970—quietly applying the same obsession with tight tolerances that made its freewheels and drivetrains so dependable. On the surface, bicycles and fishing look like different worlds. Mechanically, they rhyme. A fishing reel is a compact system of precision gears designed to spin smoothly under load, resist wear, and keep working in unforgiving conditions. In other words, it’s exactly the kind of problem Shimano was built to solve.

Over time, that second act became real scale. In 2017, bicycle components made up about 80% of Shimano’s sales, fishing tackle about 19%, with other products barely registering. In more recent years, the fishing division has contributed roughly one-fifth of the company’s overall profits—big enough to matter, but still cleanly adjacent to Shimano’s core.

At the top of Shimano’s fishing lineup sits the Stella spinning reel family—its Dura-Ace equivalent. The Stella SW line comes in sizes like 8000, 10000, and 14000, built around a rigid metal Hagane body to reduce flex and improve impact resistance, and Hagane gears that are cold-forged for durability. These are premium products, with top models priced roughly from $950 to $1,350—positioned not as “good enough,” but as the thing you buy when you don’t want the reel to be the weak link.

Shimano didn’t frame this as a random portfolio grab. Over time, it articulated a broader philosophy that could cover both businesses: building products that help people interact with nature through the outdoor activities they love. Cycling and fishing aren’t the same pastime, but they share the same emotional payload—exercise, escape, exploration, time outside. Shimano started to talk about that as “human nature”: the idea that in a rapidly urbanizing world, these activities keep people connected to the natural environment.

There was also a business logic underneath the poetry. Fishing demand often moves differently than bike demand, giving Shimano a stabilizer when one side of the house cools off.

Not every experiment worked, though. Shimano sold golf equipment until 2005 and snowboarding gear until 2008, then exited both after they failed to deliver. The takeaway was simple and very Shimano: diversification works when the core competency transfers. Precision mechanisms are one thing. Entirely different product economics are another.

VIII. The Global Manufacturing Footprint

If Shimano has a superpower, it isn’t just engineering. It’s manufacturing—specifically, the ability to make an enormous range of precision parts, in huge volumes, reliably, year after year. That’s where a lot of the company’s real advantage lives: in the unglamorous, hard-to-replicate machinery of production.

Shimano’s global production network spans roughly fifteen countries, anchored by major manufacturing hubs in Kunshan in China, plus Malaysia and Singapore. It opened its plant in Malaysia in 1990, then pushed further in the early 1990s with expansion into places like Italy, Belgium, and Indonesia—patient, deliberate steps that added up to a truly global footprint.

This geographic spread isn’t just about chasing low costs. It’s a risk strategy. When you aren’t dependent on one country, problems that would cripple a single-location manufacturer—currency swings, regional disruptions, localized shutdowns—become more manageable. Shimano can shift production emphasis, keep supplying customers, and avoid turning a hiccup into a full-blown industry shortage. And because it has presence near major markets, it can also cut down on shipping time, complexity, and expense.

Today, Shimano maintains fabrication facilities across Australia, China, Germany, India, Indonesia, Japan, Malaysia, Mexico, the Philippines, Singapore, Taiwan, Thailand, the United Kingdom, the United States, and Vietnam. It didn’t build that map all at once. It accumulated it over decades, one facility and one capability at a time.

Just as important as where Shimano makes things is how it makes them. The company is deeply vertically integrated. It produces nearly every key element of its component systems internally—chains, cassettes, derailleurs, shifters, brakes, and, increasingly, electronic modules. That integration turns manufacturing into an extension of R&D. When Shimano engineers refine a design, they can work directly with production teams inside the same organization, rather than negotiating timelines and compromises with outside suppliers.

For the bike brands that actually have to ship finished bicycles, this is the deal. Choosing Shimano isn’t only choosing performance. It’s choosing the confidence that next year’s parts will show up on time, at scale, whether your assembly line is in Asia or Europe. Plenty of smaller rivals can offer clever ideas. Far fewer can offer that kind of industrial certainty.

IX. The E-Bike Revolution: SHIMANO STEPS (2010–Present)

Electric bicycles have been the biggest product shift in cycling since indexed shifting. What started as a niche, slightly awkward category turned into a mainstream way people commute, exercise, and replace car trips—and it scaled fast enough to reshape what “a bicycle company” even means.

For Shimano, e-bikes were both an opportunity and a threat. If the heart of the bike becomes a motor system, the company that owns that system can start to own the ecosystem around it. Shimano couldn’t sit this one out.

It also wasn’t starting from zero. In 2001, Shimano debuted Di2 on NEXAVE C910, a comfort-focused component system that used electronic assistance to make riding easier with automatic shifting. Shimano had explored electronic help well before it became fashionable.

But its first dedicated e-bike drive system, SHIMANO STEPS—short for Shimano Total electric Power Systems—arrived in 2010. The early version used a front-mounted motor, and it didn’t land the way Shimano needed it to. Range was limited, the weight distribution felt off, and adoption stayed modest. So Shimano did what it tends to do when a product doesn’t meet the bar: it rebuilt it.

In spring 2014, the revised STEPS launched with a mid-mounted motor and a much better range. That change mattered. Mid-drive motors don’t just feel more natural; they also integrate better with the way bikes are designed and ridden, especially as e-bikes moved from commuter machines into performance categories.

By 2016, Shimano went directly at one of the fastest-growing segments: electric mountain bikes. It introduced the E8000 series, designed for the reality of e-MTB riding—harsh vibration, mud, impacts, and the expectation that the motor won’t compromise the geometry and handling that make a mountain bike feel right in the first place.

Then came Shimano’s big push: EP8 in 2020. EP8 was positioned as a serious step forward from E8000, with Shimano citing reduced pedaling resistance through gearbox updates and new seals aimed at cutting friction. It also brought the kind of headline spec the market had started to demand: 85 Nm of torque, putting it squarely in the fight with the category leader, Bosch, and with premium, brand-specific systems like Specialized’s.

Shimano didn’t stop there. A second-generation motor followed in the form of EP801, with updates—particularly in software—intended to refine how the whole system feels on the trail and on the street.

But the bigger story isn’t the torque number. It’s the strategic bet underneath: can Shimano’s classic playbook translate to a world where the drivetrain is part mechanical, part electrical, part software?

In traditional bikes, Shimano’s advantages compound: integrated groupsets, massive manufacturing scale, a global service network, and generations of mechanics trained on Shimano systems. E-bikes add a new axis of competition. Bosch built early dominance in European e-bikes and keeps investing. Specialized built proprietary motors tightly tied to its own product line. And manufacturers in China keep pushing capable systems at lower price points.

Shimano’s answer has been to do what it does best: make the motor one more piece of a larger, integrated system. With STEPS, Shimano can tie together the drive unit, batteries, Di2 electronic shifting, and the broader groupset ecosystem through its E-TUBE software platform. For bike manufacturers, that’s the pitch: don’t just buy a motor—buy a coordinated platform where shifting, braking, and power delivery are designed to work together.

The question is whether that integration advantage becomes the new SIS in an electrified era, or whether motors turn into a separate battlefield where Shimano’s dominance isn’t guaranteed.

X. The COVID Boom and Subsequent Crash (2020–2024)

Few industries got whipped around by the pandemic quite like bicycles. What started as a crisis turned into a bonanza—and then collapsed into a long, messy hangover.

In 2020, lockdowns shut gyms, public transit suddenly felt risky, and millions of people rediscovered the simplest form of personal mobility: a bike. Shops sold through inventory faster than they could restock. Bike brands begged for delivery slots. And component suppliers like Shimano watched orders pile up so far into the future that “lead time” started to sound like a different kind of calendar.

For a while, it looked like the world had permanently shifted. Shimano’s revenue surged and then peaked in 2022, when it reached $4.843 billion. The industry narrative hardened quickly: cycling had found a new baseline.

It hadn’t. Demand normalized faster than production could unwind, and the entire supply chain lurched in the opposite direction. Shimano’s annual revenue dropped to $3.368 billion in 2023, then fell again to $2.977 billion in 2024—an 11.62% decline year over year. Even so, that 2024 level was still about 24% above 2019, the last full year before COVID.

The mechanism behind the bust was classic bullwhip effect. Retailers—traumatized by empty shelves—over-ordered to protect themselves. Distributors doubled down. Manufacturers ramped output. Then, as consumer buying cooled in late 2022 and into 2023, everyone looked up and realized the same thing at once: warehouses were full, and nobody needed more product.

Shimano said the underlying interest in bicycles remained solid, but the near-term reality was inventory. In Europe, retail sales softened, helped along by unfavorable early spring weather, while inventories stayed high. North America showed similar symptoms: continued interest, but weak sell-through and too much stock sitting in the channel.

That inventory overhang showed up clearly in Shimano’s results. In 2024, total sales were about 451 billion yen (roughly $2.94 billion), down 4.9% from the year before. In the bicycle division, net sales fell 5.2% to 345 billion yen, and operating income declined 17%. Across the company, operating income dropped 22.2% to 65,085 million yen.

And yet, net income moved the other way—up 24.8% to 76,329 million yen, even as revenue fell. The simplest explanation is that Shimano was working through the aftermath of the boom: managing inventories, selling through existing stock, and not needing to run production at the same intensity.

Financially, Shimano still looked like Shimano. Total assets rose to 958,953 million yen, and the shareholder equity ratio stood at 92.0%—a reminder that this company has built its empire with an unusually strong balance sheet.

Looking ahead, Shimano forecast a return to modest growth in fiscal 2025: net sales expected to rise 4.2% to 470,000 million yen, with operating income up 7.6%. Management’s view was that the inventory correction was nearing completion, especially across Asian, Oceanian, and Latin American markets.

There were also signs the recovery wouldn’t happen everywhere at once. North America was a relative bright spot: Shimano’s net sales there rose in 2024, from 44.6 billion yen in 2023 to 46.9 billion yen in 2024—suggesting that different regions were clearing the backlog on different timelines.

XI. The 2023 Crankset Recall Crisis

Just as Shimano was grinding through the post-pandemic downturn, it got hit with a very different kind of problem—one that went straight at the company’s core promise: precision you can trust.

The issue centered on Shimano’s 11-speed bonded Hollowtech road cranksets manufactured prior to July 2019, including models like Ultegra FC-6800, Dura-Ace FC-9000, Ultegra FC-R8000, Dura-Ace FC-R9100, and FC-R9100P.

Shimano issued a global recall and inspection program for these cranks. The scale was enormous: more than 760,000 units affected in North America and about 2.8 million globally. In the U.S., the Consumer Product Safety Commission said the recall covered cranks sold over an 11-year span, from January 2012 through August 2023.

The numbers behind the decision were hard to ignore. Shimano reported 4,519 incidents of cranksets separating, along with six injuries, including fractures, joint displacement, and lacerations. These cranksets were widely distributed through bike shops nationwide, sold from January 2012 through August 2023, and priced from about $270 up to $1,500 depending on model and spec.

The root problem was bonding separation. These crankarms used a laminated, bonded construction, and in some cases the layers could delaminate—weakening the arm and potentially leading to sudden failure while riding. On a fast descent or in a sprint, that isn’t a minor defect. It’s a crash.

Shimano’s response was a global “free inspection program” for the 2.8 million 11-speed Hollowtech II road cranks sold between 2012 and 2019, citing “potential fall and injury hazards to consumers.”

Then the financial costs started to crystallize. Shimano initially disclosed extraordinary losses of 2,762 million yen (about $18.5 million) related to the recall. But that figure wasn’t the full bill. In its 2024 full-year financial highlights report, Shimano said it had set aside 17.6 billion yen (about $123 million at current exchange rates) to cover costs incurred and expected under the global inspection program. Reporting elsewhere framed the total global spending across 2023 and 2024 as over £160 million, broken out as roughly £93 million and £70 million.

The process itself became part of the controversy. Some mechanics criticized Shimano’s reliance on visual inspection, arguing it couldn’t reliably detect delamination forming inside the bonded layers. One mechanic, Russell, said the visual checks Shimano instructed shops to perform were inadequate for identifying bonding separation that could lead to failure. He described inspecting around a dozen recalled cranks and failing all of them—not because each one showed obvious damage, but because he didn’t have the tools to confidently declare any of them safe. “I will not send cyclists back out onto the road with a crankset that may spontaneously fail in the future,” he said.

Shimano and retailers moved to add tools and training for shops handling the recall. Under a proposed settlement between plaintiffs and Shimano North America, consumers would also receive an additional two years of warranty coverage—pending approval by a judge.

For Shimano, this wasn’t just a hit to earnings. It was a hit to the thing that makes the whole Shimano machine work: the quiet, global assumption—held by mechanics, bike brands, and riders—that Shimano parts are the safe choice. And once that assumption cracks, the next generation of groupsets, whether 12-speed mechanical or electronic, carries an extra burden: not just to perform, but to rebuild trust.

XII. The Competitive Landscape

Shimano’s dominance is real, but it isn’t uncontested. Pressure comes from two places: SRAM in traditional components, and a crowded, Europe-led fight for e-bike motors.

Shimano’s main rival in bike components is SRAM, the American company founded in 1987. SRAM has built a credible alternative lineup across road and mountain, and it has kept expanding the ecosystem around the drivetrain. In 2021, for example, SRAM acquired Hammerhead, a maker of cycle computers—an incremental move toward owning more of the rider’s “cockpit,” not just what happens at the wheels.

The modern rivalry is easiest to see in electronic shifting. Shimano’s Dura-Ace Di2 arrived in 2009 and helped kick off the era where high-end drivetrains started looking more like electronics products than mechanical ones. SRAM answered with Red eTap—announced in 2015, released in spring 2016—and made a clean, differentiated bet: go fully wireless.

That decision mattered. Shimano’s Di2 approach stayed semi-wired, with wireless shifters communicating to wired derailleurs. SRAM’s eTap, by contrast, removed wires from the setup entirely. For riders and mechanics, that translated into simpler installation, cleaner aesthetics, and fewer routing headaches inside modern frames.

SRAM has continued to iterate hard at the top end. In May 2024, it introduced a new Red AXS groupset and said it had refined every component with a heavy focus on weight reduction. SRAM claims the lightest version comes in at 2,649 grams and positions it as the lightest electronic groupset available—exactly the kind of headline that grabs attention in a segment where marginal gains sell bikes.

Then there’s Campagnolo: the Italian heritage brand that still carries enormous emotional gravity in road cycling. It remains a distant third in scale—loved by traditionalists and present at the high end, but not operating with anything close to Shimano’s or SRAM’s volume. If Shimano and SRAM are fighting for the center of the market, Campagnolo is defending a premium niche.

E-bikes are a different battlefield altogether. Shimano’s competitors aren’t just component brands; they’re motor-system platforms. Bosch established early dominance in European e-bikes and continues to invest aggressively, especially across trekking and city bikes in places like Germany and the Netherlands. Specialized built proprietary motors for its own e-bike lines, tightening integration by keeping the drive system inside the brand. And newer players like Fazua have targeted the “light e-bike” category with compact, lower-power systems designed to feel closer to analog bikes.

The takeaway is subtle but important: Shimano’s moat is still deep in traditional components, where its manufacturing scale, groupset integration, and decades of mechanic familiarity compound. In e-bike motors, the playing field is less settled—and Shimano is competing on rivals’ home turf, in a market where software, service networks, and platform adoption can matter as much as the hardware itself.

XIII. Porter's Five Forces Analysis

To see why Shimano’s lead has lasted so long—and where it can still get surprised—it helps to step back from individual products and look at the structure of the industry. Porter’s Five Forces is a clean way to do that.

Threat of New Entrants: LOW

It’s hard to overstate how difficult it is to “just start a Shimano competitor.”

First, there’s the time factor. Shimano’s current lineup is the output of decades of accumulated engineering, manufacturing knowledge, and iteration. Precision bicycle components look simple until you try to mass-produce them with tight tolerances, high durability, and consistent feel across millions of units.

Then there’s the industrial footprint. Shimano’s supply chain and manufacturing base spans about fifteen countries, built up over generations. A new entrant doesn’t just need a great derailleur design; it needs factories, tooling, quality systems, logistics, and the ability to deliver on schedule to bike makers around the world.

The biggest barrier, though, may be the least visible: OEM relationships. Trek, Giant, Specialized, and hundreds of other brands have designed bikes around Shimano standards for years. Switching isn’t just swapping parts. It means retraining teams, changing specs, revising frame and cable routing decisions, rebuilding service and warranty processes, and taking a risk on real-world reliability.

Patents help too—SIS, Di2, and STEPS are all examples—but the deeper protection is Shimano’s system approach. Even when patents expire, competitors still have to replicate not a part, but a whole ecosystem that works together.

Bargaining Power of Suppliers: LOW to MODERATE

Shimano is big enough to have leverage. When you buy enormous volumes of raw materials—aluminum, steel, carbon fiber, and increasingly electronic components—you get negotiating power.

Vertical integration strengthens that position. Shimano makes much of what it sells internally, so it isn’t at the mercy of a single outside supplier for every critical part. And its geographically diversified operations—across China, Malaysia, Singapore, and other locations—give it options. If costs or constraints tighten in one place, Shimano has the ability to rebalance sourcing and production elsewhere.

That said, electronics and certain specialized inputs can still create pockets of supplier power, especially when the broader market is tight.

Bargaining Power of Buyers: MODERATE

Shimano’s customers are bike manufacturers, and they’re in a complicated position.

On one hand, Shimano’s breadth, reliability, and integration mean that for most segments there aren’t many true substitutes that match the full package: performance, availability, and compatibility at scale. That limits how much leverage an average bike brand has in negotiations.

On the other hand, the biggest manufacturers matter. Companies like Giant and Trek buy enough volume to be taken seriously, and they can credibly shift some models to SRAM if Shimano pushes too hard on pricing or terms. Even when they don’t switch, they can influence Shimano’s roadmap—features, timing, and specs—because Shimano needs their bikes to be successful, too.

End consumers have relatively little direct bargaining power here. Most people buy a bike, not a groupset, and accept whatever spec the brand chose—especially outside the enthusiast tier.

Threat of Substitutes: LOW to MODERATE

For the traditional derailleur drivetrain, substitutes exist, but they’re still limited.

Belt drives can be clean and low-maintenance, but they typically require special frames and come with tradeoffs in flexibility and performance. Internal gear hubs work well for certain city and utility bikes, but they don’t deliver the same efficiency and feel that performance riders expect from derailleurs.

The more meaningful substitute pressure comes from e-bikes. As motors and integrated drive systems take center stage, the “heart” of the bike shifts. If buyers start choosing primarily based on motor performance and software experience, the relative importance of a rear derailleur—and the advantages Shimano historically compounded there—can shrink.

Over the very long term, there’s also the possibility of broader substitutes for cycling itself: scooters, better public transit, or other mobility shifts. Those are real but speculative.

Industry Rivalry: MODERATE

Shimano’s scale—often cited around 70% in mid-to-high-end gearsets—normally dampens rivalry. When one player is that large, competitors often can’t afford to fight everywhere at once.

But Shimano doesn’t get to relax. SRAM is a serious rival, especially at the high end where brand perception and margins are strongest. It moved early with fully wireless shifting, and it’s built a broader ecosystem through acquisitions like RockShox, Zipp, and Quarq. That’s a deliberate attempt to match Shimano’s “system” advantage with a system of its own.

So even in a market with a clear leader, the fight stays intense where it matters most: premium products, new technology transitions, and the platforms—like e-bikes—where the rules are still being written.

XIV. Hamilton's 7 Powers Analysis

Porter helps explain why the game is hard to enter. Hamilton Helmer’s 7 Powers helps explain why Shimano has kept winning it for so long—why its advantages don’t just appear, but stick.

Scale Economies: STRONG ✓

Shimano’s scale shows up most clearly in manufacturing. Operating across roughly fifteen countries lets it spread fixed costs—factories, tooling, quality systems, and especially R&D—across a sales base that few rivals can touch.

Build something expensive and complex like Di2 electronic shifting, and Shimano can amortize that development across an enormous number of groupsets. SRAM and Campagnolo face the same physics of engineering cost, but with a much smaller volume to spread it over.

Network Effects: MODERATE

Shimano doesn’t have “classic” network effects like a social network. But it does have an ecosystem flywheel that behaves similarly.

Mechanics train on Shimano. Bike shops stock Shimano. When a chain snaps or a cable frays, the part that’s on the wall—and the one the mechanic can install fastest—is often Shimano. Availability reinforces familiarity, and familiarity reinforces availability.

Compatibility deepens the effect. Shimano’s Di2 systems are designed to integrate smoothly with other Shimano components. For bike manufacturers, once you commit to Shimano derailleurs, the easiest path to predictable performance is usually Shimano shifters, chains, and cassettes too.

Counter-Positioning: HISTORICALLY STRONG

Shimano’s rise also featured a move that looks obvious in hindsight and was deeply non-obvious at the time: it often introduced new technology at the low end first, using cheaper, heavier materials, and only moved it upmarket once it proved itself.

That flipped the usual script. European brands built innovation at the top and let it trickle down slowly, protecting premium positioning and margins. Shimano’s approach was classic counter-positioning: by making “new” accessible early, it forced incumbents into an uncomfortable choice. Respond quickly and risk diluting the high-end aura. Respond slowly and let the market reset its expectations without you.

This specific advantage has faded over time. Shimano now often debuts its newest tech at the top—Dura-Ace—and then rolls it down the product ladder. But the scale and manufacturing advantages built during that earlier era still compound today.

Switching Costs: STRONG ✓

Shimano’s product strategy turns the drivetrain into a system, and systems create switching costs.

For manufacturers, a bike designed around Shimano components—geometry choices, cable routing, derailleur interfaces—doesn’t always swap cleanly to a competitor without rework. Switching means engineering time, new supplier coordination, assembly-line retraining, and the risk of warranty problems if the integration isn’t perfect.

For consumers, switching brands usually isn’t “change a part.” It’s replace the groupset. That’s expensive enough that most riders don’t do it. They just buy their next bike with whatever it comes with—often Shimano again.

Cornered Resource: MODERATE

Shimano’s “cornered” resources aren’t a single patent or exclusive contract. They’re the accumulated assets that take a long time to build: deep engineering know-how, long-standing OEM relationships, and trust among mechanics and bike brands.

None of these are purely proprietary. Competitors can hire talent, build relationships, and earn credibility. But Shimano’s advantage is that it has been doing all three for decades, continuously, at global scale.

Process Power: STRONG ✓

If there’s a power that feels most “Shimano,” it’s process.

A century of precision manufacturing—going back to freewheels—shows up in the company’s ability to machine, assemble, and quality-control complex parts consistently in massive volumes. That’s not just equipment. It’s embedded organizational knowledge: how to run production, prevent defects, manage suppliers, and keep tolerances tight across factories and geographies.

Those processes are hard to copy because they aren’t written down in a single manual. They live in systems, people, culture, and accumulated iteration.

Branding: MODERATE

Among enthusiasts, Shimano stands for reliability, quality, and credibility earned in professional racing. That brand matters, especially at the high end.

But branding is not Shimano’s primary weapon in the way it is for many consumer product companies. Most bike buyers don’t pick components à la carte; they accept the spec that comes on the bike. So Shimano’s brand helps close the sale and reinforces trust—but the heavier lifting comes from integration, availability, and manufacturing strength.

XV. Investment Considerations: What Matters Going Forward

Shimano’s last hundred years explain how it got here. But for investors, the only thing that matters is whether the next decade looks like the last one. A few forces will largely decide whether Shimano’s historically strong performance can continue.

The E-Bike Transition

For most of Shimano’s history, the center of gravity in cycling was the drivetrain. If you owned shifting and braking, you owned the ride experience. E-bikes change that. As electric-assist takes a larger share of bicycle sales, the motor system becomes the “must-win” component—the part that defines how the bike feels, what it costs, and which ecosystem it belongs to.

Shimano’s STEPS platform is a real contender, but it’s not an uncontested field. Bosch has built deep, early dominance in Europe, and a wave of Chinese manufacturers keeps pressure on pricing.

So the strategic question is simple: can Shimano recreate the groupset playbook in e-bikes?

If STEPS integrates cleanly with Di2 shifting, Shimano batteries, and the broader component ecosystem—one coherent platform that’s easy for bike makers to spec and easy for shops to support—then Shimano has a path to making the motor just another Shimano-controlled anchor point. But if the e-bike world stays more modular, where manufacturers mix motors, batteries, drivetrains, and software as interchangeable parts, Shimano’s traditional integration advantage gets weaker.

The Inventory Cycle

Shimano is still living with the aftereffects of the pandemic boom—and the painful correction that followed it. Inventory has been the story: too much product stuck in the channel, slowing new orders even when consumer interest hasn’t disappeared.

There were signs of improvement in 2024 across Asian, Oceanian, and Central and South American markets, where inventory levels began to look healthier. If the correction finishes working through the system, revenue should have room to recover on underlying demand. If it drags on, it keeps acting like a brake on results—regardless of how good Shimano’s products are.

Key Performance Indicators

If you want a simple dashboard to track whether the story is getting better or worse, three signals matter most:

-

Bicycle component revenue versus the 2022 peak: Shimano’s 2022 high-water mark remains the easiest benchmark for what “normalized” demand looked like at the top of the cycle. Moving back toward that level would suggest the industry is healing. Staying far below it for years could imply something structural has changed.

-

E-bike motor traction: As e-bikes become a bigger portion of total bike sales, STEPS adoption becomes a proxy for whether Shimano is winning the next platform shift. Public market share data is messy, but a practical signal is how often STEPS shows up on new e-bike models from major brands.

-

Gross margin stability: Shimano’s margins have historically reflected a rare mix of pricing power and manufacturing efficiency. If margins start compressing meaningfully, it’s usually the market telling you something: competition is intensifying, pricing is getting pressured, or motors are becoming more commodity-like than Shimano would want.

XVI. Bull Case and Bear Case

Bull Case

Shimano’s century-long run isn’t a fluke of timing. It’s the result of structural advantages that don’t disappear just because inventories are high for a few quarters. This is a company that has already lived through multiple technology shifts—friction shifting to indexed shifting, then into electronic—and each time it responded the same way: invest in R&D, invest in manufacturing, and turn a “part” into a system.

It also behaves like a business that believes that playbook still works. Shimano has continued to return capital through dividends and share buybacks, a signal of confidence that the long-term engine is intact even when the cycle turns ugly.

From that perspective, e-bikes are less an existential threat and more the next platform to win. Shimano STEPS doesn’t have to stand alone; it can slot into the broader Shimano ecosystem—drivetrain, shifting, software—so that bike makers and riders get one integrated experience rather than a patchwork of vendors. If e-bikes keep moving from niche to mainstream, the argument goes, the market will start rewarding the same things that made Shimano the default in analog bikes: reliability, serviceability, and tight integration.

In that world, the post-COVID inventory mess is painful but temporary. The demand drivers that pulled cycling forward before the pandemic—urbanization, health and fitness, and environmental awareness—are still there. And if the industry consolidates, Shimano’s scale and global manufacturing footprint can become even more valuable, because being the supplier that can deliver consistently at volume matters more when weaker players are retrenching.

Even the crankset recall can be framed as a long-term positive. It was expensive, and it was embarrassing—but it also showed Shimano choosing consumer safety and a global response over denial or delay. If Shimano handles quality issues transparently and aggressively, the trust it rebuilds can end up reinforcing the brand rather than permanently damaging it.

Bear Case

The bear case starts with a simple point: e-bike motors aren’t derailleurs.

Bosch built a powerful position in Europe—still the world’s largest e-bike market—before Shimano’s STEPS offering really matured. And once a motor platform becomes the standard for bike brands, dealers, and service networks, displacing it isn’t just a matter of being “better.” It’s a matter of breaking inertia across the entire ecosystem. That’s a much tougher job than winning a spec battle on traditional components.

Then there’s pressure from below. Chinese manufacturers continue to improve quality while keeping aggressive pricing, and they don’t need to beat Shimano everywhere—just enough to compress the price umbrella Shimano has historically enjoyed. If that dynamic accelerates, it could hit both ends of the business: traditional components and e-bike drive systems.

The recall also raises a darker possibility: that it wasn’t just a one-off defect, but a sign that quality control can slip at Shimano’s scale. If mechanics and serious riders start questioning Shimano’s engineering reliability, the company’s premium positioning—and the margins that come with it—can erode faster than most investors expect.

Finally, the demand backdrop might not bounce the way the industry hopes. The post-pandemic normalization could be more severe and longer-lasting, especially if a large portion of the bikes bought during lockdowns simply sit in garages. If upgrades don’t materialize and replacement cycles stretch, Shimano could be staring at years of muted demand rather than a quick snap-back.

XVII. Conclusion: The Quiet Giant Endures

A century after Shozaburo Shimano opened a small ironworks in Japan’s sword-making capital, the company he started still sits underneath the simple magic of a bike that just works. Shimano isn’t the name on the frame. It’s the invisible infrastructure—inside the crank, the derailleur, the shifter—that powers everyday commuting and weekend rides, across the world, year after year.

The arc from freewheels to indexed shifting to electronic drivetrains to e-bike motors spans multiple technological eras, but the strategy has stayed surprisingly consistent.

It starts with a constraint that turned into a superpower: never compete with your customer. By refusing to build complete bicycles, Shimano made itself safe to partner with—useful to every brand, threatening to none. From there, SIS did more than improve shifting. It redefined shifting, then used integration to turn a collection of parts into an ecosystem. SunTour didn’t just lose a feature race; it lost the platform shift.

Then Shimano did the unsexy thing better than almost anyone: it manufactured. Decades of accumulated scale, process discipline, and vertical integration created a cost and quality position that’s brutally hard to replicate. Clever competitors can build a great component. Shimano can build the whole system, in volume, reliably, and support it everywhere.

That’s why the current chapter matters. Inventory corrections after the pandemic boom, the reputational and financial weight of the crankset recall, and intensifying competition in e-bike motors all test the same question: does Shimano’s historical playbook still compound in a world where software and electric drive systems are as important as machined metal?

The case for durability is still there. Shimano’s core capabilities transfer—precision engineering, system integration, and manufacturing depth. Switching costs remain real for both bike makers and riders. And a global footprint offers resilience when the supply chain gets ugly.

For long-term investors, Shimano is a rare combination: a century of operating history, family-influenced governance that favors the long view, dominant market position with clear moats, and exposure to the long-run growth of cycling as transportation, recreation, and fitness—now increasingly electrified.

Shimano endures precisely because it stays quiet. Every crisp gear change, every dependable brake pull, every rider who never thinks about what’s happening beneath their feet—that’s Shimano’s product. And it all traces back to Sakai, and to a machinist who understood that if you control the components, you shape the ride.

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music